User login

Cracking the clinician educator code in gastroenterology

For gastroenterologists who enter academic medicine, the most common career track is that of clinician educator (CE). Although most academic gastroenterologists are CEs, their career paths vary substantially, and expectations for promotion can be much less explicit compared with those of physician scientists. This delineation of different pathways in academic gastroenterology starts as early as the fellowship application process, before the implications are understood. Furthermore, many community gastroenterologists have appointments within academic medical centers, which typically fall into the realm of CEs.

A review of all gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program websites listed on the American Gastroenterological Association website showed that 33 of 175 (18.8%) programs endorse distinctly different tracks, usually distinguishing traditional research (i.e., basic science, epidemiology, or outcomes) from clinical care of patients (i.e., clinician educator or clinical scholar). One of the most common words appearing in descriptions of both tracks was “clinical,” highlighting that a good clinician educator or researcher is, first and foremost, a good clinician.

With clinical duties requiring the majority of a CE’s time and efforts, a reasonable assumption is that CEs are clinicians who teach trainees via lectures, clinic, endoscopy, and/or inpatient rounds. Although such educational endeavors form the backbone of a CE’s scholarly activities, what constitutes scholarship for CEs is much more diverse than many people realize. The variability in what a career as a CE may look like can be both an obstacle and an opportunity. Included in the category of CE are community clinicians who have a stake in the education of residents and fellows and play an important role in trainee learning. Sherbino et al1 defined a CE as “a clinician active in health professional practice who applies theory to education practice, engages in education scholarship, and serves as a consultant to other health professionals on education issues.”

Because we recognize that many community and academic gastroenterologists spend the majority of their education efforts teaching trainees, we have made every effort to ensure that the five recommendations listed later are equally pertinent to all gastroenterologists who devote any portion of their careers to educating trainees, colleagues, allied health professionals, as well as patients. For example, a CE who primarily teaches trainees still can benefit from learning how to better document their efforts, receive mentorship as an educator, take everyday activities and convert them into scholarship, share teaching materials with broader audiences, and learn new teaching techniques without ever opening a book on education theory. For community-based physicians, this can assist in obtaining recognition from the academic centers for their teaching efforts. We hope that the five recommendations that follow will serve to guide those just setting out on the CE path, as well as for those who have trodden it for some time.

Number 1: Maintain a current curriculum vitae and teaching portfolio

All CEs must have two critical instruments to document their accomplishments to their institutions and to the field: a curriculum vitae (CV) and a teaching portfolio. These items also are very important when the time comes for promotion because they validate one’s accomplishments, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Knowing the criteria for promotion as a CE is critical for shaping one’s career, and we recommend checking with an individual’s institution for its specific requirements regarding formats for both the CV and the teaching portfolio, which typically are available from the academic promotion committee. Because most fellows and faculty are familiar with the format of a CV, we will focus on the teaching portfolio.

For most fellows and many faculty, the teaching portfolio is a new and/or less well understood entity. Unlike a CV, the teaching portfolio presents teaching activities not only as a collection or list, but also provides evidence of the influence the work has had on others, in a much more personal way. A few tips are listed on putting together a teaching portfolio. However, the most important advice we can offer is this: one should save all evidence of teaching including unsolicited letters and e-mails from learners and colleagues.

If your institution does not have a teaching portfolio template, we recommend using a pre-existing format. Several examples from academic medicine can be found on the Internet or on MedEdPORTAL, an open-access repository of educational content provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges. One such tool is the Educator Portfolio Template of the Academic Pediatric Association’s Educational Scholars Program (available: https://www.academicpeds.org/education/educator_portfolio_template.cfm). The Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Education Affairs held a consensus conference in 2006, from which five educational categories were defined: teaching, learner assessment, curriculum development, mentoring and advising, and educational leadership and administration.2 These categories can serve as an arrangement for a teaching portfolio. We also recommend that you include both educational research/scholarship and web-based educational materials such as online learning modules, YouTube videos, blogs, and wikis as a part of a teaching portfolio. For each project highlighted in the teaching portfolio, we recommend reflecting on and writing down how the project shows the quantity and quality of the work.

Quantity of work in the teaching portfolio refers to more than a mere cataloging of published peer-reviewed articles and book chapters, courses taught, presentations given, and so forth (which should be included in the CV). Instead, it documents time spent in teaching activities, how often teaching occurs, the number and types of learners involved, and how the activity fits into a training program.

Quality of work can include how innovative methods were crafted and implemented to customize teaching in creative ways to accomplish specific learning objectives. This description renders the contents of the teaching portfolio more than merely a sketch of work activities documented by numbers, and tells a story about what occurred. When documenting evidence of quality, provide comparative measures whenever possible. Quality of teaching also can be illustrated by evaluations, pretests and posttests, and as complimentary e-mails and letters from learners and other faculty members. The description of teaching activities also shows one’s flexibility as an educator, and the greater the breadth of experiences, the better. A CE also must document within the portfolio how the teaching activity drew from existing literature and best practices and/or contributed to the medical education field and its body of knowledge. Above all else, we recommend collecting evidence on teaching to both provide evidence of one’s teaching skills and to gather data on which to improve.

The teaching portfolio templates begin with a personal statement outlining why one teaches (i.e., teaching philosophy). In a teaching portfolio, it is important to include details of how impact was defined or determined with regard to teaching endeavors, how the feedback from formal evaluative processes was used to mold one’s future activities as an educator, and what strategies will be implemented to improve teaching to meet the needs of diverse and changing groups of learners.

Both the CV and teaching portfolio should be updated continually – we recommend at least quarterly (or as articles are published, courses are taught, abstracts are presented, and so forth) – to ensure that nothing is overlooked or forgotten.

Number 2: Mentors and mentees

Every CE needs to have a primary mentor, typically a more senior faculty member with an interest in and experience with mentoring, as well as a commitment to fostering the mentee’s professional growth. It may be difficult to find a mentor when starting out as a junior faculty member or when changing academic institutions. Once you have a mentor, take ownership for the success of the relationship by managing-up, by organizing all the meetings, exceeding (not just meeting) deadlines, and by communicating needs and information in a way the mentor prefers. Rustgi and Hecht3 wrap up their article on mentorship with a pathway that highlights the following components for a successful mentoring relationship: regular meetings, specific goals and measurable outcomes, manuscript and grant writing, presentation skills and efficiency, and navigating the complexities of regulatory affairs such as institutional review boards. Although many of these tenets hold true for both clinician researchers and clinician educators, Farrell et al4 offer four steps to finding a mentor for clinician educators, as follows. Step 1: self-reflection and assessment: critically assessing one’s competence as a teacher, educational administrator, or researcher; determining what prior education projects have been successful and why; and defining career goals and the current relationship to them. Step 2: identification of areas needing development: examples may include teaching skills, curriculum innovation, evaluation/assessment, educational research, time management, negotiation skills, grantsmanship, scholarly writing, and presentation skills; identify specific questions regarding the type of help needed. Step 3: matchmaking: determine qualities (personal and professional) desired in a mentor, and search for candidates with the help of colleagues. Step 4: engagement with a mentor: explain why you desire mentorship, career goals, current academic role(s), your perceived needs, and recognize and acknowledge appreciation for your mentor’s time and energy.

One caution is to avoid having too many primary mentors. A mentee may assume the perspective that it takes a village when it comes to seeking and providing mentoring. Although having clinical, research, and/or personal mentors can be helpful, having too many mentors can make it difficult to meet regularly enough to allow for the mentee–mentor relationship to grow. Instead of a network of mentors, build a web of minimentors, or coaches, to serve as consultants, coaches, and accountability partners, and tap into this network as needed. Mentors are involved longitudinally with mentees and tend to provide general career and project-specific guidance, whereas coaches tend to be involved in specific projects or areas of focus of a mentee.

In addition to having their own mentors, CEs quickly will find opportunities themselves to serve as mentors to more junior faculty, fellows, residents, and students. Indeed, one measure of a successful mentor–mentee relationship is the development of the mentee into a new mentor for future generations.

Number 3: Think broadly about scholarship

Traditionally, the definition of scholarship has been very narrow and usually is related to the number of publications and grants one receives. Beginning with Boyer’s work in 1990, the definition of scholarship has expanded at academic institutions beyond the concept of traditional research.5 Medical education scholarship most often is guided and judged by six core qualitative standards of excellence, known as “Glassick’s criteria”6: clear goals, adequate preparation, appropriate methods, significant results, effective presentation, and reflective critique. The key to scholarship is that it builds on or adds to the field, is made public, and thus available for peer-review.

CE projects can be categorized in many ways, but we recommend broadening the classic notions of research with which we have been indoctrinated. Golub’s7 2016 editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “Looking Inward and Reflecting Back: Medical Education and Journal of the American Medical Association,” highlights the range of research questions and methodologies, which include ethics, behavioral psychology, diversity of patient care and the workforce, medical education research, quality and value of care, well-being of trainees and faculty, and health informatics. If one breaks down daily tasks, countless opportunities for scholarly projects will emerge. One need look no further for opportunities than the countless opportunities for quality improvement research that avail themselves daily, with examples ranging from reducing variation in cirrhosis care to improving adenoma detection rates. Quality improvement is an important method of scholarship for both academic and community-based physicians, which also can contribute toward Part IV of Maintenance of Certification requirements. CEs also can engage in educational scholarship other than research by using these same principles. To transform your teaching into scholarship you should examine the activities you perform or a problem that needs to be solved, apply information or a solution based on best practices or what is known from the literature, and then share the results/products with others (peer-review). Crites et al8 provide practical guidelines for developing education research questions, designing and implementing scholarly activities, and interpreting the scope and impact of education scholarship.

In addition, reaching beyond one’s department to other departments, as well as participating in educational scholarly activities on regional and national levels, is important as one’s career progresses. Well-connected and diverse networks are information highways by which one’s work can be amplified to achieve a greater impact, and from which many opportunities will be shared.

Number 4: Share broadly

Scholarship activities of both academic and community-based CEs can target many audiences, including medical students, residents, and fellows; faculty; other health professions; or even patients and the community. Knowing who will be the recipients or end-users can help to identify which types of projects may be most rewarding and make the greatest impact. Consider sharing curricula, evaluation tools, and other educational products with colleagues at other institutions who ask for them. Request acknowledgment for the development of the materials and ask for written feedback on how these products are being used and what impact they have had on learners.

One education model used to assess the impact and target of education interventions is known as Kirkpatrick’s9 hierarchy, which traditionally included the following four levels: reaction (level 1), learning (level 2), behavior (level 3), and results (level 4). The model has been adapted by the British Medical Journal’s Best Evidence in Medical Education collaboration to medical education with the following modifications in levels as follows.9,10 Level 1: participation: focused on learners’ views of the learning experience including content, presentation, and teaching methods. Level 2a: modification of attitudes/perceptions: focused on changes in attitudes or perceptions between participant groups toward the intervention. Level 2b: modification of knowledge/skills: for knowledge, focused on the acquisition of concepts, procedures, and principles; for skills, focused on the acquisition of problem solving, psychomotor, and social skills. Level 3: behavioral change: focused on the transfer of learning to the workplace or willingness of learners to apply new knowledge and skills. Level 4a: change in organizational practice: focused on wider changes in the organization or delivery of care attributable to an educational program. Level 4b: focused on improvements in the health and well-being of patients as a direct result of an education initiative.

Similar to more traditional clinical research, education research needs to be performed in a scholarly fashion and shared with a wider audience. In addition to submitting research to gastroenterology journals (e.g., Gastroenterology’s Mentoring, Education, and Training Corner), education research can be submitted to education journals such as the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Academic Medicine, the Association for the Study of Medical Education’s Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Journal of Graduate Medical Education, or the European Association for Medical Education in Europe’s Medical Teacher; online education warehouses such as MedEdPORTAL (www.mededportal.org) or MERLOT (www.merlot.org); and national conferences as workshops. Also, one should keep in mind that opportunities arise on a regular basis to share educational videos or images in forums such as the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy’s video journal VideoGIE, The American Journal of Gastroenterology’s video of the month, and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology’s Images of the Month.

Number 5: Ongoing professional development

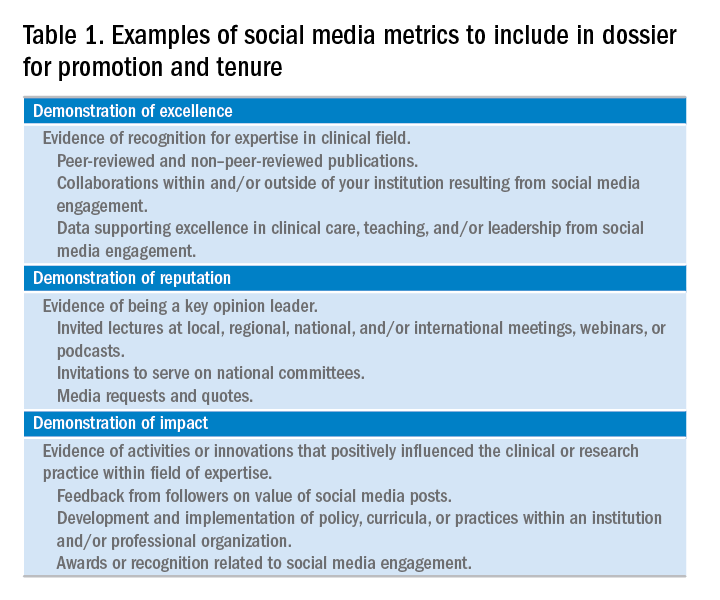

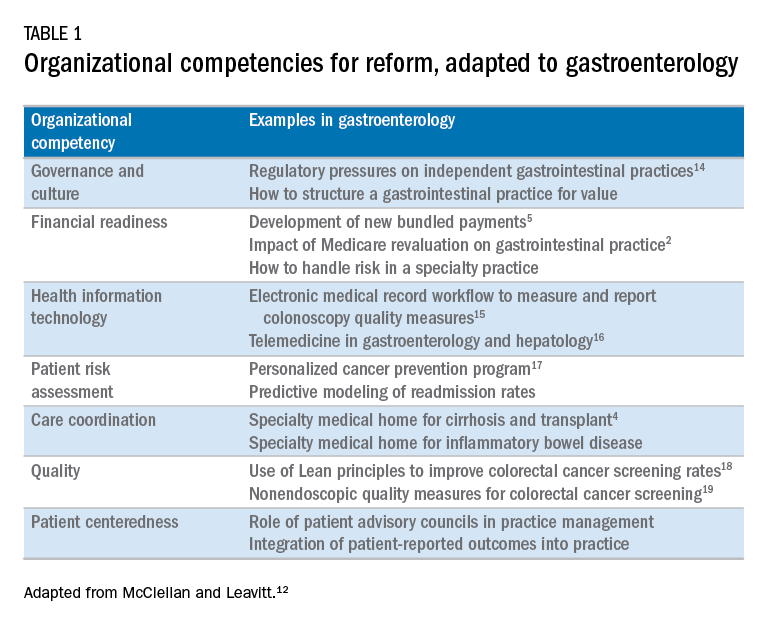

Continuing Medical Education is a standard requirement to maintain an active medical license because it shows ongoing efforts to remain up-to-date with changes in medicine. Similar opportunities exist with respect to further development as an educator. Given the multitude of manners in which these opportunities can be divided, we have compiled recommendations for resources on educational scholarship based on level of experience and desired level of engagement (Table 1).

Summary

The framework provided should help guide the gastroenterologist on the path of becoming an effective clinician educator in gastroenterology. The diversity of what a career as a clinician educator can entail is unlimited. The success of the future of medical education and our careers requires not only that every clinician educator be productive, but also that each one brings a unique passion to work each day to share. The authors would like to thank all those clinician educators who contributed to our education, and look forward to learning from you in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Lee Ligon, Center for Research, Innovation, and Scholarship, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, for providing editorial assistance.

References

1. Sherbino, J., Frank, J.R., Snell, L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician-educator of the 21st century: a national mixed-methods study. Acad Med. 2014;89:783-9.

2. Simpson, D., Fincher, R.M., Hafler, J.P., et al. Advancing educators and education by defining the components and evidence associated with educational scholarship. Med Educ. 2007;41:1002-9.

3. Rustgi, A.K. Hecht, G.A. Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:789-92.

4. Farrell, S.E., Digioia, N.M., Broderick, K.B., et al. Mentoring for clinician-educators. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1346-50.

5. Boyer, E.L. Scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professoriate. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Princeton, NJ; 1990.

6. Glassick, C.E., Taylor-Huber, M., Maeroff, G.I., et al. Scholarship assessed: evaluation of the professoriate. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco; 1997.

7. Golub, R.M. Looking inward and reflecting back medical education and JAMA. JAMA. 2016;316:2200-3.

8. Crites, G.E., Gaines, J.K., Cottrell, S., et al. Medical education scholarship: an introductory guide: AMEE guide no. 89. Med Teach. 2014;36:657-74.

9. Kirkpatrick, D.L. Evaluation of training. In: R. Craig, L. Bittel (Eds.) Training and development handbook. McGraw-Hill, New York; 1967: 87-112.

10. Littlewood, S., Ypinazar, V., Margolis, S.A., et al. Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;331:387-91.

Dr. Shapiro is a gastroenterology fellow in the department of medicine, section of gastroenterology; Dr. Gould Suarez is an associate professor in the department of medicine, section of gastroenterology and associate program director of the gastroenterology fellowship; and Dr. Turner is an associate professor of pediatrics, vice chair of education, associate program director for house staff education, section of academic general pediatrics, and director for research, innovation, and scholarship, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. The authors disclose no conflicts.

For gastroenterologists who enter academic medicine, the most common career track is that of clinician educator (CE). Although most academic gastroenterologists are CEs, their career paths vary substantially, and expectations for promotion can be much less explicit compared with those of physician scientists. This delineation of different pathways in academic gastroenterology starts as early as the fellowship application process, before the implications are understood. Furthermore, many community gastroenterologists have appointments within academic medical centers, which typically fall into the realm of CEs.

A review of all gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program websites listed on the American Gastroenterological Association website showed that 33 of 175 (18.8%) programs endorse distinctly different tracks, usually distinguishing traditional research (i.e., basic science, epidemiology, or outcomes) from clinical care of patients (i.e., clinician educator or clinical scholar). One of the most common words appearing in descriptions of both tracks was “clinical,” highlighting that a good clinician educator or researcher is, first and foremost, a good clinician.

With clinical duties requiring the majority of a CE’s time and efforts, a reasonable assumption is that CEs are clinicians who teach trainees via lectures, clinic, endoscopy, and/or inpatient rounds. Although such educational endeavors form the backbone of a CE’s scholarly activities, what constitutes scholarship for CEs is much more diverse than many people realize. The variability in what a career as a CE may look like can be both an obstacle and an opportunity. Included in the category of CE are community clinicians who have a stake in the education of residents and fellows and play an important role in trainee learning. Sherbino et al1 defined a CE as “a clinician active in health professional practice who applies theory to education practice, engages in education scholarship, and serves as a consultant to other health professionals on education issues.”

Because we recognize that many community and academic gastroenterologists spend the majority of their education efforts teaching trainees, we have made every effort to ensure that the five recommendations listed later are equally pertinent to all gastroenterologists who devote any portion of their careers to educating trainees, colleagues, allied health professionals, as well as patients. For example, a CE who primarily teaches trainees still can benefit from learning how to better document their efforts, receive mentorship as an educator, take everyday activities and convert them into scholarship, share teaching materials with broader audiences, and learn new teaching techniques without ever opening a book on education theory. For community-based physicians, this can assist in obtaining recognition from the academic centers for their teaching efforts. We hope that the five recommendations that follow will serve to guide those just setting out on the CE path, as well as for those who have trodden it for some time.

Number 1: Maintain a current curriculum vitae and teaching portfolio

All CEs must have two critical instruments to document their accomplishments to their institutions and to the field: a curriculum vitae (CV) and a teaching portfolio. These items also are very important when the time comes for promotion because they validate one’s accomplishments, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Knowing the criteria for promotion as a CE is critical for shaping one’s career, and we recommend checking with an individual’s institution for its specific requirements regarding formats for both the CV and the teaching portfolio, which typically are available from the academic promotion committee. Because most fellows and faculty are familiar with the format of a CV, we will focus on the teaching portfolio.

For most fellows and many faculty, the teaching portfolio is a new and/or less well understood entity. Unlike a CV, the teaching portfolio presents teaching activities not only as a collection or list, but also provides evidence of the influence the work has had on others, in a much more personal way. A few tips are listed on putting together a teaching portfolio. However, the most important advice we can offer is this: one should save all evidence of teaching including unsolicited letters and e-mails from learners and colleagues.

If your institution does not have a teaching portfolio template, we recommend using a pre-existing format. Several examples from academic medicine can be found on the Internet or on MedEdPORTAL, an open-access repository of educational content provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges. One such tool is the Educator Portfolio Template of the Academic Pediatric Association’s Educational Scholars Program (available: https://www.academicpeds.org/education/educator_portfolio_template.cfm). The Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Education Affairs held a consensus conference in 2006, from which five educational categories were defined: teaching, learner assessment, curriculum development, mentoring and advising, and educational leadership and administration.2 These categories can serve as an arrangement for a teaching portfolio. We also recommend that you include both educational research/scholarship and web-based educational materials such as online learning modules, YouTube videos, blogs, and wikis as a part of a teaching portfolio. For each project highlighted in the teaching portfolio, we recommend reflecting on and writing down how the project shows the quantity and quality of the work.

Quantity of work in the teaching portfolio refers to more than a mere cataloging of published peer-reviewed articles and book chapters, courses taught, presentations given, and so forth (which should be included in the CV). Instead, it documents time spent in teaching activities, how often teaching occurs, the number and types of learners involved, and how the activity fits into a training program.

Quality of work can include how innovative methods were crafted and implemented to customize teaching in creative ways to accomplish specific learning objectives. This description renders the contents of the teaching portfolio more than merely a sketch of work activities documented by numbers, and tells a story about what occurred. When documenting evidence of quality, provide comparative measures whenever possible. Quality of teaching also can be illustrated by evaluations, pretests and posttests, and as complimentary e-mails and letters from learners and other faculty members. The description of teaching activities also shows one’s flexibility as an educator, and the greater the breadth of experiences, the better. A CE also must document within the portfolio how the teaching activity drew from existing literature and best practices and/or contributed to the medical education field and its body of knowledge. Above all else, we recommend collecting evidence on teaching to both provide evidence of one’s teaching skills and to gather data on which to improve.

The teaching portfolio templates begin with a personal statement outlining why one teaches (i.e., teaching philosophy). In a teaching portfolio, it is important to include details of how impact was defined or determined with regard to teaching endeavors, how the feedback from formal evaluative processes was used to mold one’s future activities as an educator, and what strategies will be implemented to improve teaching to meet the needs of diverse and changing groups of learners.

Both the CV and teaching portfolio should be updated continually – we recommend at least quarterly (or as articles are published, courses are taught, abstracts are presented, and so forth) – to ensure that nothing is overlooked or forgotten.

Number 2: Mentors and mentees

Every CE needs to have a primary mentor, typically a more senior faculty member with an interest in and experience with mentoring, as well as a commitment to fostering the mentee’s professional growth. It may be difficult to find a mentor when starting out as a junior faculty member or when changing academic institutions. Once you have a mentor, take ownership for the success of the relationship by managing-up, by organizing all the meetings, exceeding (not just meeting) deadlines, and by communicating needs and information in a way the mentor prefers. Rustgi and Hecht3 wrap up their article on mentorship with a pathway that highlights the following components for a successful mentoring relationship: regular meetings, specific goals and measurable outcomes, manuscript and grant writing, presentation skills and efficiency, and navigating the complexities of regulatory affairs such as institutional review boards. Although many of these tenets hold true for both clinician researchers and clinician educators, Farrell et al4 offer four steps to finding a mentor for clinician educators, as follows. Step 1: self-reflection and assessment: critically assessing one’s competence as a teacher, educational administrator, or researcher; determining what prior education projects have been successful and why; and defining career goals and the current relationship to them. Step 2: identification of areas needing development: examples may include teaching skills, curriculum innovation, evaluation/assessment, educational research, time management, negotiation skills, grantsmanship, scholarly writing, and presentation skills; identify specific questions regarding the type of help needed. Step 3: matchmaking: determine qualities (personal and professional) desired in a mentor, and search for candidates with the help of colleagues. Step 4: engagement with a mentor: explain why you desire mentorship, career goals, current academic role(s), your perceived needs, and recognize and acknowledge appreciation for your mentor’s time and energy.

One caution is to avoid having too many primary mentors. A mentee may assume the perspective that it takes a village when it comes to seeking and providing mentoring. Although having clinical, research, and/or personal mentors can be helpful, having too many mentors can make it difficult to meet regularly enough to allow for the mentee–mentor relationship to grow. Instead of a network of mentors, build a web of minimentors, or coaches, to serve as consultants, coaches, and accountability partners, and tap into this network as needed. Mentors are involved longitudinally with mentees and tend to provide general career and project-specific guidance, whereas coaches tend to be involved in specific projects or areas of focus of a mentee.

In addition to having their own mentors, CEs quickly will find opportunities themselves to serve as mentors to more junior faculty, fellows, residents, and students. Indeed, one measure of a successful mentor–mentee relationship is the development of the mentee into a new mentor for future generations.

Number 3: Think broadly about scholarship

Traditionally, the definition of scholarship has been very narrow and usually is related to the number of publications and grants one receives. Beginning with Boyer’s work in 1990, the definition of scholarship has expanded at academic institutions beyond the concept of traditional research.5 Medical education scholarship most often is guided and judged by six core qualitative standards of excellence, known as “Glassick’s criteria”6: clear goals, adequate preparation, appropriate methods, significant results, effective presentation, and reflective critique. The key to scholarship is that it builds on or adds to the field, is made public, and thus available for peer-review.

CE projects can be categorized in many ways, but we recommend broadening the classic notions of research with which we have been indoctrinated. Golub’s7 2016 editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “Looking Inward and Reflecting Back: Medical Education and Journal of the American Medical Association,” highlights the range of research questions and methodologies, which include ethics, behavioral psychology, diversity of patient care and the workforce, medical education research, quality and value of care, well-being of trainees and faculty, and health informatics. If one breaks down daily tasks, countless opportunities for scholarly projects will emerge. One need look no further for opportunities than the countless opportunities for quality improvement research that avail themselves daily, with examples ranging from reducing variation in cirrhosis care to improving adenoma detection rates. Quality improvement is an important method of scholarship for both academic and community-based physicians, which also can contribute toward Part IV of Maintenance of Certification requirements. CEs also can engage in educational scholarship other than research by using these same principles. To transform your teaching into scholarship you should examine the activities you perform or a problem that needs to be solved, apply information or a solution based on best practices or what is known from the literature, and then share the results/products with others (peer-review). Crites et al8 provide practical guidelines for developing education research questions, designing and implementing scholarly activities, and interpreting the scope and impact of education scholarship.

In addition, reaching beyond one’s department to other departments, as well as participating in educational scholarly activities on regional and national levels, is important as one’s career progresses. Well-connected and diverse networks are information highways by which one’s work can be amplified to achieve a greater impact, and from which many opportunities will be shared.

Number 4: Share broadly

Scholarship activities of both academic and community-based CEs can target many audiences, including medical students, residents, and fellows; faculty; other health professions; or even patients and the community. Knowing who will be the recipients or end-users can help to identify which types of projects may be most rewarding and make the greatest impact. Consider sharing curricula, evaluation tools, and other educational products with colleagues at other institutions who ask for them. Request acknowledgment for the development of the materials and ask for written feedback on how these products are being used and what impact they have had on learners.

One education model used to assess the impact and target of education interventions is known as Kirkpatrick’s9 hierarchy, which traditionally included the following four levels: reaction (level 1), learning (level 2), behavior (level 3), and results (level 4). The model has been adapted by the British Medical Journal’s Best Evidence in Medical Education collaboration to medical education with the following modifications in levels as follows.9,10 Level 1: participation: focused on learners’ views of the learning experience including content, presentation, and teaching methods. Level 2a: modification of attitudes/perceptions: focused on changes in attitudes or perceptions between participant groups toward the intervention. Level 2b: modification of knowledge/skills: for knowledge, focused on the acquisition of concepts, procedures, and principles; for skills, focused on the acquisition of problem solving, psychomotor, and social skills. Level 3: behavioral change: focused on the transfer of learning to the workplace or willingness of learners to apply new knowledge and skills. Level 4a: change in organizational practice: focused on wider changes in the organization or delivery of care attributable to an educational program. Level 4b: focused on improvements in the health and well-being of patients as a direct result of an education initiative.

Similar to more traditional clinical research, education research needs to be performed in a scholarly fashion and shared with a wider audience. In addition to submitting research to gastroenterology journals (e.g., Gastroenterology’s Mentoring, Education, and Training Corner), education research can be submitted to education journals such as the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Academic Medicine, the Association for the Study of Medical Education’s Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Journal of Graduate Medical Education, or the European Association for Medical Education in Europe’s Medical Teacher; online education warehouses such as MedEdPORTAL (www.mededportal.org) or MERLOT (www.merlot.org); and national conferences as workshops. Also, one should keep in mind that opportunities arise on a regular basis to share educational videos or images in forums such as the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy’s video journal VideoGIE, The American Journal of Gastroenterology’s video of the month, and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology’s Images of the Month.

Number 5: Ongoing professional development

Continuing Medical Education is a standard requirement to maintain an active medical license because it shows ongoing efforts to remain up-to-date with changes in medicine. Similar opportunities exist with respect to further development as an educator. Given the multitude of manners in which these opportunities can be divided, we have compiled recommendations for resources on educational scholarship based on level of experience and desired level of engagement (Table 1).

Summary

The framework provided should help guide the gastroenterologist on the path of becoming an effective clinician educator in gastroenterology. The diversity of what a career as a clinician educator can entail is unlimited. The success of the future of medical education and our careers requires not only that every clinician educator be productive, but also that each one brings a unique passion to work each day to share. The authors would like to thank all those clinician educators who contributed to our education, and look forward to learning from you in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Lee Ligon, Center for Research, Innovation, and Scholarship, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, for providing editorial assistance.

References

1. Sherbino, J., Frank, J.R., Snell, L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician-educator of the 21st century: a national mixed-methods study. Acad Med. 2014;89:783-9.

2. Simpson, D., Fincher, R.M., Hafler, J.P., et al. Advancing educators and education by defining the components and evidence associated with educational scholarship. Med Educ. 2007;41:1002-9.

3. Rustgi, A.K. Hecht, G.A. Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:789-92.

4. Farrell, S.E., Digioia, N.M., Broderick, K.B., et al. Mentoring for clinician-educators. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1346-50.

5. Boyer, E.L. Scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professoriate. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Princeton, NJ; 1990.

6. Glassick, C.E., Taylor-Huber, M., Maeroff, G.I., et al. Scholarship assessed: evaluation of the professoriate. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco; 1997.

7. Golub, R.M. Looking inward and reflecting back medical education and JAMA. JAMA. 2016;316:2200-3.

8. Crites, G.E., Gaines, J.K., Cottrell, S., et al. Medical education scholarship: an introductory guide: AMEE guide no. 89. Med Teach. 2014;36:657-74.

9. Kirkpatrick, D.L. Evaluation of training. In: R. Craig, L. Bittel (Eds.) Training and development handbook. McGraw-Hill, New York; 1967: 87-112.

10. Littlewood, S., Ypinazar, V., Margolis, S.A., et al. Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;331:387-91.

Dr. Shapiro is a gastroenterology fellow in the department of medicine, section of gastroenterology; Dr. Gould Suarez is an associate professor in the department of medicine, section of gastroenterology and associate program director of the gastroenterology fellowship; and Dr. Turner is an associate professor of pediatrics, vice chair of education, associate program director for house staff education, section of academic general pediatrics, and director for research, innovation, and scholarship, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. The authors disclose no conflicts.

For gastroenterologists who enter academic medicine, the most common career track is that of clinician educator (CE). Although most academic gastroenterologists are CEs, their career paths vary substantially, and expectations for promotion can be much less explicit compared with those of physician scientists. This delineation of different pathways in academic gastroenterology starts as early as the fellowship application process, before the implications are understood. Furthermore, many community gastroenterologists have appointments within academic medical centers, which typically fall into the realm of CEs.

A review of all gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program websites listed on the American Gastroenterological Association website showed that 33 of 175 (18.8%) programs endorse distinctly different tracks, usually distinguishing traditional research (i.e., basic science, epidemiology, or outcomes) from clinical care of patients (i.e., clinician educator or clinical scholar). One of the most common words appearing in descriptions of both tracks was “clinical,” highlighting that a good clinician educator or researcher is, first and foremost, a good clinician.

With clinical duties requiring the majority of a CE’s time and efforts, a reasonable assumption is that CEs are clinicians who teach trainees via lectures, clinic, endoscopy, and/or inpatient rounds. Although such educational endeavors form the backbone of a CE’s scholarly activities, what constitutes scholarship for CEs is much more diverse than many people realize. The variability in what a career as a CE may look like can be both an obstacle and an opportunity. Included in the category of CE are community clinicians who have a stake in the education of residents and fellows and play an important role in trainee learning. Sherbino et al1 defined a CE as “a clinician active in health professional practice who applies theory to education practice, engages in education scholarship, and serves as a consultant to other health professionals on education issues.”

Because we recognize that many community and academic gastroenterologists spend the majority of their education efforts teaching trainees, we have made every effort to ensure that the five recommendations listed later are equally pertinent to all gastroenterologists who devote any portion of their careers to educating trainees, colleagues, allied health professionals, as well as patients. For example, a CE who primarily teaches trainees still can benefit from learning how to better document their efforts, receive mentorship as an educator, take everyday activities and convert them into scholarship, share teaching materials with broader audiences, and learn new teaching techniques without ever opening a book on education theory. For community-based physicians, this can assist in obtaining recognition from the academic centers for their teaching efforts. We hope that the five recommendations that follow will serve to guide those just setting out on the CE path, as well as for those who have trodden it for some time.

Number 1: Maintain a current curriculum vitae and teaching portfolio

All CEs must have two critical instruments to document their accomplishments to their institutions and to the field: a curriculum vitae (CV) and a teaching portfolio. These items also are very important when the time comes for promotion because they validate one’s accomplishments, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Knowing the criteria for promotion as a CE is critical for shaping one’s career, and we recommend checking with an individual’s institution for its specific requirements regarding formats for both the CV and the teaching portfolio, which typically are available from the academic promotion committee. Because most fellows and faculty are familiar with the format of a CV, we will focus on the teaching portfolio.

For most fellows and many faculty, the teaching portfolio is a new and/or less well understood entity. Unlike a CV, the teaching portfolio presents teaching activities not only as a collection or list, but also provides evidence of the influence the work has had on others, in a much more personal way. A few tips are listed on putting together a teaching portfolio. However, the most important advice we can offer is this: one should save all evidence of teaching including unsolicited letters and e-mails from learners and colleagues.

If your institution does not have a teaching portfolio template, we recommend using a pre-existing format. Several examples from academic medicine can be found on the Internet or on MedEdPORTAL, an open-access repository of educational content provided by the Association of American Medical Colleges. One such tool is the Educator Portfolio Template of the Academic Pediatric Association’s Educational Scholars Program (available: https://www.academicpeds.org/education/educator_portfolio_template.cfm). The Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Education Affairs held a consensus conference in 2006, from which five educational categories were defined: teaching, learner assessment, curriculum development, mentoring and advising, and educational leadership and administration.2 These categories can serve as an arrangement for a teaching portfolio. We also recommend that you include both educational research/scholarship and web-based educational materials such as online learning modules, YouTube videos, blogs, and wikis as a part of a teaching portfolio. For each project highlighted in the teaching portfolio, we recommend reflecting on and writing down how the project shows the quantity and quality of the work.

Quantity of work in the teaching portfolio refers to more than a mere cataloging of published peer-reviewed articles and book chapters, courses taught, presentations given, and so forth (which should be included in the CV). Instead, it documents time spent in teaching activities, how often teaching occurs, the number and types of learners involved, and how the activity fits into a training program.

Quality of work can include how innovative methods were crafted and implemented to customize teaching in creative ways to accomplish specific learning objectives. This description renders the contents of the teaching portfolio more than merely a sketch of work activities documented by numbers, and tells a story about what occurred. When documenting evidence of quality, provide comparative measures whenever possible. Quality of teaching also can be illustrated by evaluations, pretests and posttests, and as complimentary e-mails and letters from learners and other faculty members. The description of teaching activities also shows one’s flexibility as an educator, and the greater the breadth of experiences, the better. A CE also must document within the portfolio how the teaching activity drew from existing literature and best practices and/or contributed to the medical education field and its body of knowledge. Above all else, we recommend collecting evidence on teaching to both provide evidence of one’s teaching skills and to gather data on which to improve.

The teaching portfolio templates begin with a personal statement outlining why one teaches (i.e., teaching philosophy). In a teaching portfolio, it is important to include details of how impact was defined or determined with regard to teaching endeavors, how the feedback from formal evaluative processes was used to mold one’s future activities as an educator, and what strategies will be implemented to improve teaching to meet the needs of diverse and changing groups of learners.

Both the CV and teaching portfolio should be updated continually – we recommend at least quarterly (or as articles are published, courses are taught, abstracts are presented, and so forth) – to ensure that nothing is overlooked or forgotten.

Number 2: Mentors and mentees

Every CE needs to have a primary mentor, typically a more senior faculty member with an interest in and experience with mentoring, as well as a commitment to fostering the mentee’s professional growth. It may be difficult to find a mentor when starting out as a junior faculty member or when changing academic institutions. Once you have a mentor, take ownership for the success of the relationship by managing-up, by organizing all the meetings, exceeding (not just meeting) deadlines, and by communicating needs and information in a way the mentor prefers. Rustgi and Hecht3 wrap up their article on mentorship with a pathway that highlights the following components for a successful mentoring relationship: regular meetings, specific goals and measurable outcomes, manuscript and grant writing, presentation skills and efficiency, and navigating the complexities of regulatory affairs such as institutional review boards. Although many of these tenets hold true for both clinician researchers and clinician educators, Farrell et al4 offer four steps to finding a mentor for clinician educators, as follows. Step 1: self-reflection and assessment: critically assessing one’s competence as a teacher, educational administrator, or researcher; determining what prior education projects have been successful and why; and defining career goals and the current relationship to them. Step 2: identification of areas needing development: examples may include teaching skills, curriculum innovation, evaluation/assessment, educational research, time management, negotiation skills, grantsmanship, scholarly writing, and presentation skills; identify specific questions regarding the type of help needed. Step 3: matchmaking: determine qualities (personal and professional) desired in a mentor, and search for candidates with the help of colleagues. Step 4: engagement with a mentor: explain why you desire mentorship, career goals, current academic role(s), your perceived needs, and recognize and acknowledge appreciation for your mentor’s time and energy.

One caution is to avoid having too many primary mentors. A mentee may assume the perspective that it takes a village when it comes to seeking and providing mentoring. Although having clinical, research, and/or personal mentors can be helpful, having too many mentors can make it difficult to meet regularly enough to allow for the mentee–mentor relationship to grow. Instead of a network of mentors, build a web of minimentors, or coaches, to serve as consultants, coaches, and accountability partners, and tap into this network as needed. Mentors are involved longitudinally with mentees and tend to provide general career and project-specific guidance, whereas coaches tend to be involved in specific projects or areas of focus of a mentee.

In addition to having their own mentors, CEs quickly will find opportunities themselves to serve as mentors to more junior faculty, fellows, residents, and students. Indeed, one measure of a successful mentor–mentee relationship is the development of the mentee into a new mentor for future generations.

Number 3: Think broadly about scholarship

Traditionally, the definition of scholarship has been very narrow and usually is related to the number of publications and grants one receives. Beginning with Boyer’s work in 1990, the definition of scholarship has expanded at academic institutions beyond the concept of traditional research.5 Medical education scholarship most often is guided and judged by six core qualitative standards of excellence, known as “Glassick’s criteria”6: clear goals, adequate preparation, appropriate methods, significant results, effective presentation, and reflective critique. The key to scholarship is that it builds on or adds to the field, is made public, and thus available for peer-review.

CE projects can be categorized in many ways, but we recommend broadening the classic notions of research with which we have been indoctrinated. Golub’s7 2016 editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, “Looking Inward and Reflecting Back: Medical Education and Journal of the American Medical Association,” highlights the range of research questions and methodologies, which include ethics, behavioral psychology, diversity of patient care and the workforce, medical education research, quality and value of care, well-being of trainees and faculty, and health informatics. If one breaks down daily tasks, countless opportunities for scholarly projects will emerge. One need look no further for opportunities than the countless opportunities for quality improvement research that avail themselves daily, with examples ranging from reducing variation in cirrhosis care to improving adenoma detection rates. Quality improvement is an important method of scholarship for both academic and community-based physicians, which also can contribute toward Part IV of Maintenance of Certification requirements. CEs also can engage in educational scholarship other than research by using these same principles. To transform your teaching into scholarship you should examine the activities you perform or a problem that needs to be solved, apply information or a solution based on best practices or what is known from the literature, and then share the results/products with others (peer-review). Crites et al8 provide practical guidelines for developing education research questions, designing and implementing scholarly activities, and interpreting the scope and impact of education scholarship.

In addition, reaching beyond one’s department to other departments, as well as participating in educational scholarly activities on regional and national levels, is important as one’s career progresses. Well-connected and diverse networks are information highways by which one’s work can be amplified to achieve a greater impact, and from which many opportunities will be shared.

Number 4: Share broadly

Scholarship activities of both academic and community-based CEs can target many audiences, including medical students, residents, and fellows; faculty; other health professions; or even patients and the community. Knowing who will be the recipients or end-users can help to identify which types of projects may be most rewarding and make the greatest impact. Consider sharing curricula, evaluation tools, and other educational products with colleagues at other institutions who ask for them. Request acknowledgment for the development of the materials and ask for written feedback on how these products are being used and what impact they have had on learners.

One education model used to assess the impact and target of education interventions is known as Kirkpatrick’s9 hierarchy, which traditionally included the following four levels: reaction (level 1), learning (level 2), behavior (level 3), and results (level 4). The model has been adapted by the British Medical Journal’s Best Evidence in Medical Education collaboration to medical education with the following modifications in levels as follows.9,10 Level 1: participation: focused on learners’ views of the learning experience including content, presentation, and teaching methods. Level 2a: modification of attitudes/perceptions: focused on changes in attitudes or perceptions between participant groups toward the intervention. Level 2b: modification of knowledge/skills: for knowledge, focused on the acquisition of concepts, procedures, and principles; for skills, focused on the acquisition of problem solving, psychomotor, and social skills. Level 3: behavioral change: focused on the transfer of learning to the workplace or willingness of learners to apply new knowledge and skills. Level 4a: change in organizational practice: focused on wider changes in the organization or delivery of care attributable to an educational program. Level 4b: focused on improvements in the health and well-being of patients as a direct result of an education initiative.

Similar to more traditional clinical research, education research needs to be performed in a scholarly fashion and shared with a wider audience. In addition to submitting research to gastroenterology journals (e.g., Gastroenterology’s Mentoring, Education, and Training Corner), education research can be submitted to education journals such as the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Academic Medicine, the Association for the Study of Medical Education’s Medical Education, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Journal of Graduate Medical Education, or the European Association for Medical Education in Europe’s Medical Teacher; online education warehouses such as MedEdPORTAL (www.mededportal.org) or MERLOT (www.merlot.org); and national conferences as workshops. Also, one should keep in mind that opportunities arise on a regular basis to share educational videos or images in forums such as the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy’s video journal VideoGIE, The American Journal of Gastroenterology’s video of the month, and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology’s Images of the Month.

Number 5: Ongoing professional development

Continuing Medical Education is a standard requirement to maintain an active medical license because it shows ongoing efforts to remain up-to-date with changes in medicine. Similar opportunities exist with respect to further development as an educator. Given the multitude of manners in which these opportunities can be divided, we have compiled recommendations for resources on educational scholarship based on level of experience and desired level of engagement (Table 1).

Summary

The framework provided should help guide the gastroenterologist on the path of becoming an effective clinician educator in gastroenterology. The diversity of what a career as a clinician educator can entail is unlimited. The success of the future of medical education and our careers requires not only that every clinician educator be productive, but also that each one brings a unique passion to work each day to share. The authors would like to thank all those clinician educators who contributed to our education, and look forward to learning from you in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Lee Ligon, Center for Research, Innovation, and Scholarship, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine, for providing editorial assistance.

References

1. Sherbino, J., Frank, J.R., Snell, L. Defining the key roles and competencies of the clinician-educator of the 21st century: a national mixed-methods study. Acad Med. 2014;89:783-9.

2. Simpson, D., Fincher, R.M., Hafler, J.P., et al. Advancing educators and education by defining the components and evidence associated with educational scholarship. Med Educ. 2007;41:1002-9.

3. Rustgi, A.K. Hecht, G.A. Mentorship in academic medicine. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:789-92.

4. Farrell, S.E., Digioia, N.M., Broderick, K.B., et al. Mentoring for clinician-educators. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1346-50.

5. Boyer, E.L. Scholarship reconsidered: priorities of the professoriate. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Princeton, NJ; 1990.

6. Glassick, C.E., Taylor-Huber, M., Maeroff, G.I., et al. Scholarship assessed: evaluation of the professoriate. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco; 1997.

7. Golub, R.M. Looking inward and reflecting back medical education and JAMA. JAMA. 2016;316:2200-3.

8. Crites, G.E., Gaines, J.K., Cottrell, S., et al. Medical education scholarship: an introductory guide: AMEE guide no. 89. Med Teach. 2014;36:657-74.

9. Kirkpatrick, D.L. Evaluation of training. In: R. Craig, L. Bittel (Eds.) Training and development handbook. McGraw-Hill, New York; 1967: 87-112.

10. Littlewood, S., Ypinazar, V., Margolis, S.A., et al. Early practical experience and the social responsiveness of clinical education: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;331:387-91.

Dr. Shapiro is a gastroenterology fellow in the department of medicine, section of gastroenterology; Dr. Gould Suarez is an associate professor in the department of medicine, section of gastroenterology and associate program director of the gastroenterology fellowship; and Dr. Turner is an associate professor of pediatrics, vice chair of education, associate program director for house staff education, section of academic general pediatrics, and director for research, innovation, and scholarship, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. The authors disclose no conflicts.

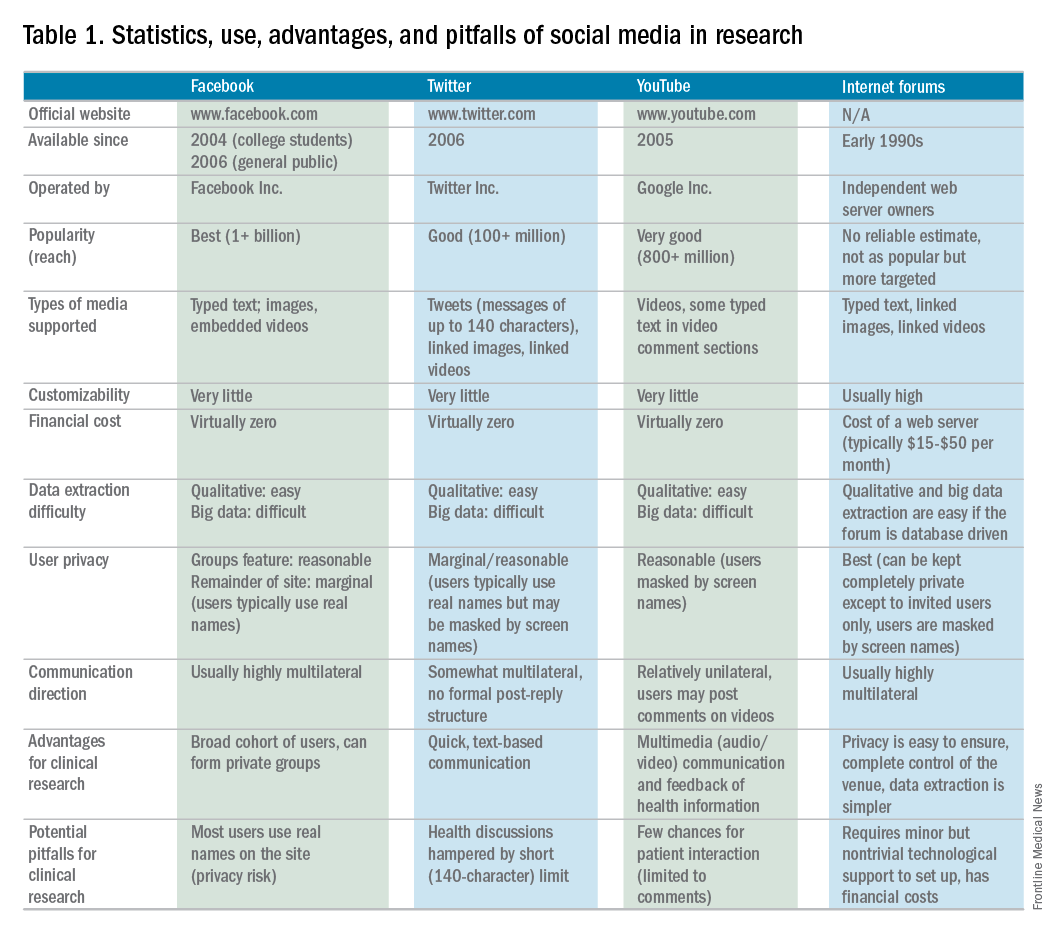

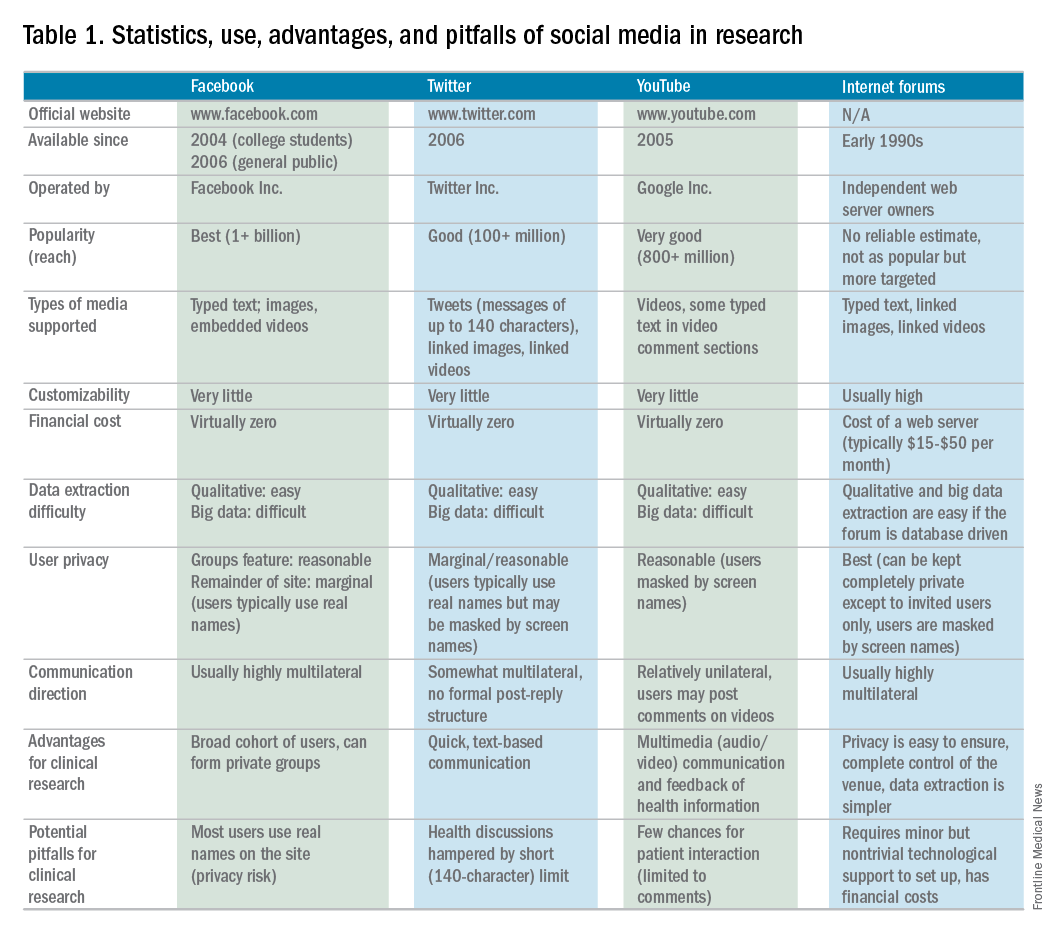

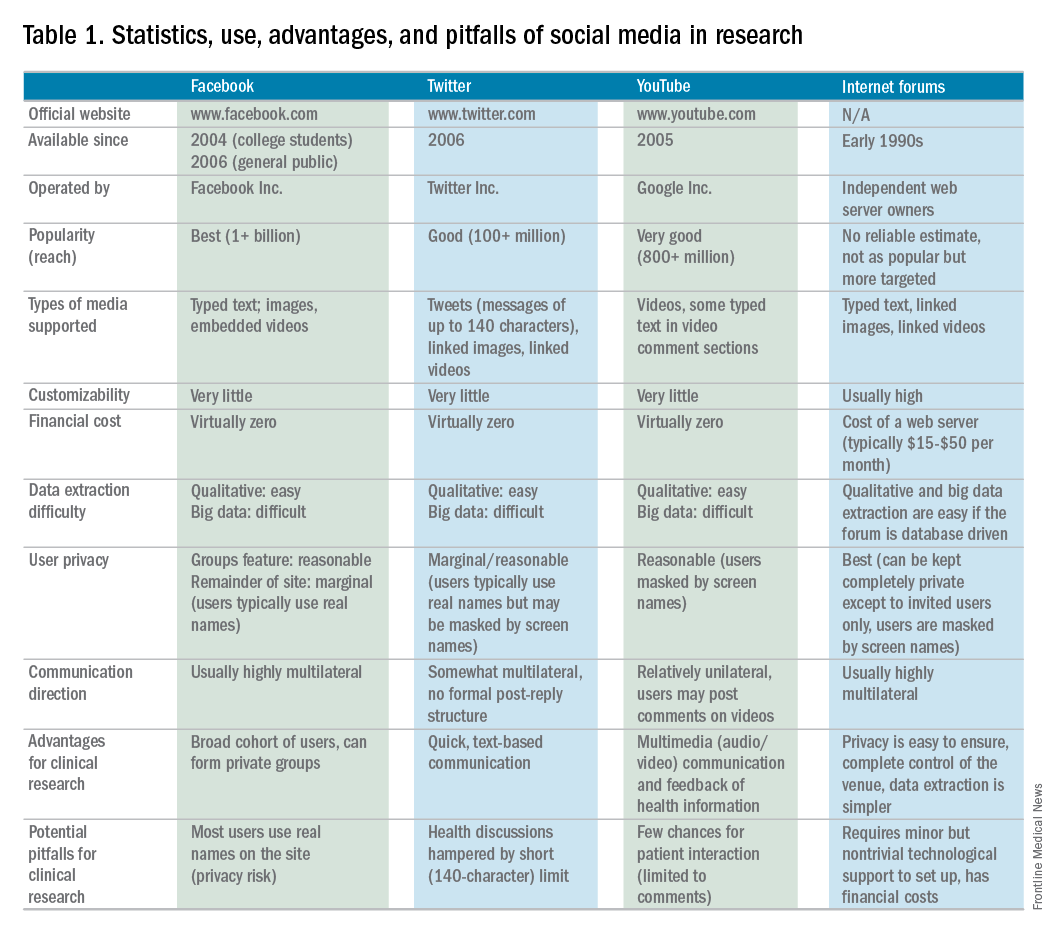

Making social media work for your practice

Social media use is ubiquitous and, in the digital age, it is the ascendant form of communication. Individuals and organizations, digital immigrants (those born before the widespread adoption of digital technology), and digital natives alike are leveraging social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn, to curate, consume, and share information across the spectrum of demographics and target audiences. In the United States, 7 in 10 Americans are using social media and, although young adults were early adopters, use among older adults is increasing rapidly.1

Furthermore, social media has cultivated remarkable opportunities in the dissemination of health information and disrupted traditional methods of patient–provider communication. The days when medically trained health professionals were the gatekeepers of health information are long gone. Approximately 50% of Americans seek health information online before seeing a physician.2 Patients and other consumers regularly access social media to search for information about diseases and treatments, engage with other patients, identify providers, and to express or rate their satisfaction with providers, clinics, and health systems.3-5 In addition, they trust online health information from doctors more than that from hospitals, health insurers, and drug companies.6 Not surprisingly, this has led to tremendous growth in use of social media by health care providers, hospitals, and health centers. More than 90% of US hospitals have a Facebook page and 50% have a Twitter account.7

There is ample opportunity to close the gap between patient and health care provider engagement in Social media, equip providers with the tools they need to be competent consumers and sharers of information in this digital exchange, and increase the pool of evidence-based information on GI and liver diseases on social media.12 However, there is limited published literature tailored to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. The goal of this article, therefore, is to provide a broad overview of best practices in the professional use of social media and highlight examples of novel applications in clinical practice.

Best practices: Getting started and maintaining a presence on social media

Social media can magnify your professional image, amplify your voice, and extend your reach and influence much faster than other methods. It also can be damaging if not used responsibly. Thus, we recommend the following approaches to responsible use of social media and cultivating your social media presence based on current evidence, professional organizations’ policy statements, and our combined experience. We initially presented these strategies during a Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Disease Week® in Chicago (http://www.ddw.org/education/session-recordings).

Second, as with other aspects of medical training and practice, find a mentor to provide hands-on advice. This is particularly true if your general familiarity with the social media platforms is limited. If this is not available through your network of colleagues or workplace, we recommend exploring opportunities offered through your professional organization(s) such as the aforementioned Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Diseases Week.

Third, know the privacy setting options on your social media platform(s) of choice and use them to your advantage. For example, on Facebook and Twitter, you can select an option that requests your permission before a friend or follower is added to your network. You also can tailor who (such as friends or followers only) can access your posted content directly. However, know that your content still may be made public if it is shared by one of your friends or followers.

Fourth, nurture your social media presence by sharing credible content deliberately, regularly, and, when appropriate, with attribution.

Fifth, diversify your content within the realm of your predefined objectives and/or goals and avoid a singular focus of self-promotion or the appearance of self-promotion. Top social media users suggest, and the authors agree, that your content should be only 25%-33% of your posts.

Sixth, thoroughly vet all content that you share. Avoid automatically sharing articles or posts because of a catchy headline. Read them before you post them. There may be details buried in them that are not credible or with which you do not agree.

Seventh, build community by connecting and engaging with other users on your social media platform(s) of choice.

Eighth, integrate multiple media (i.e., photos, videos, infographics) and/or social media platforms (i.e., embed link to YouTube or a website) to increase engagement.

Ninth, adhere to the code of ethics, governance, and privacy of the profession and of your employer.

Best practices: Privacy and governance in patient-oriented communication on social media

Two factors that have been of pivotal concern with the adoption of social media in the health care arena and led to many health care professionals being laggards as opposed to early adopters are privacy and governance. Will it violate the patient–provider relationship? What about the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act? How do I maintain boundaries between myself and the public at large? These are just a few of the questions that commonly are asked by those who are unfamiliar with social media etiquette for health care professionals. We highly recommend reviewing the position paper regarding online medical professionalism issued by the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards as a starting point.13 We believe the following to be contemporary guiding principles for GI health providers for maintaining a digital footprint on social media that reflects the ethical and professional standards of the field.

First, avoid sharing information that could be construed as a patient identifier without documented consent. This includes, but is not limited to, an identifiable specimen or photograph, and stories of care, rare conditions, and complications. Note that dates and location of care can lead to identification of a patient or care episode.

Second, recognize that personal and professional online profiles/pages are discoverable. Many advocate for separating the two as a means of shielding the public from elements of a private persona (i.e., family pictures and controversial opinions). However, the capacity to share and find comments and images on social media is much more powerful than the privacy settings on the various social media platforms. If you establish distinct personal and professional profiles, exercise caution before accepting friend or follow requests from patients on your personal profile. In addition, be cautious with your posts on private social media accounts because they rarely truly are private.

Third, avoid providing specific medical recommendations to individuals. This creates a patient–provider relationship and legal duty. Instead, recommend consultation with a health care provider and consider providing a link to general information on the topic (e.g., AGA information for patients at www.gastro.org/patientinfo).

Fourth, declare conflicts of interest, if applicable, when sharing information involving your clinical, research, and/or business practice.

Fifth, routinely monitor your online presence for accuracy and appropriateness of content posted by you and by others in reference to you. Know that our profession’s ethical standards for behavior extend to social media and we can be held accountable to colleagues and our employer if we violate them.

Many employers have become savvy to issues of governance in use of social media and institute policy recommendations to which employees are expected to adhere. If you are an employee, we recommend checking with your marketing and/or human resources department(s) in regards to this. If you are an employer and do not have such a policy on online professionalism, it is our hope that this article serves as a launching pad.

Novel applications for social media in clinical practice

Social media has been shown to be an effective medium for medical education through virtual journal clubs, moderated discussions or chats, and video sharing for teaching procedures, to name a few applications. Social media is used to collect data via polls or surveys, and to disseminate and track the views and downloads of published works. It is also a source for unsolicited, real-time feedback on patient experience and engagement through data-mining techniques, such as natural language processing and, more simply, for solicited feedback for patient satisfaction ratings. However, its role in academic promotion is less clear and is an area for which we see a great opportunity for growth.

Summary

We have outlined a high-level overview for why you should consider establishing and maintaining a professional presence on social media and how to accomplish this. These reasons include sharing information with colleagues, patients, and the public; amplifying the voice of physicians, a view that has diminished in the often-volatile health care environment; and promotion of the value of your work, be it patient care, advocacy, research, or education. You will have a smoother experience if you learn your local rules and policies and abide by our suggestions to avoid adverse outcomes. You will be most effective if you establish goals for your social media participation and revisit these goals over time for continued relevance and success and if you have consistent and valuable output that will support attainment of these goals. Welcome to the GI social media community! Be sure to follow Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology and the American Gastroenterological Association on Facebook (facebook.com/cghjournal and facebook.com/amergastroassn) and Twitter (@AGA_CGH and @AmerGastroAssn), and the coauthors (@DMGrayMD and @DrDeborahFisher) on Twitter.

References

1. Social Media Fact Sheet. Pew Research Center [updated January 12, 2017]. Available from http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheet/social-media/. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

2. Hesse B.W., Nelson D.E., Kreps G.L., et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2618-24.

3. Moorhead S.A., Hazlett D.E., Harrison L., et al. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e85.

4. Chou W.Y., Hunt Y.M., Beckjord E.B. et al. Social media use in the United States: implications for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2009;11:e48.

5. Chretien K.C., Kind T. Social media and clinical care: ethical, professional, and social implications. Circulation. 2013;27:1413-21.

6. Social Media ‘likes’ Healthcare. PwC Health Research Institute; 2012. Available from https://www.pwc.com/us/en/health-industries/health-research-institute/publications/pdf/health-care-social-media-report.pdf. Accessed: June 20, 2017.

7. Griffis H.M., Kilaru A.S., Werner R.M., et al. Use of social media across US hospitals: descriptive analysis of adoption and utilization. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e264.

8. Davis E.D., Tang S.J., Glover P.H., et al. Impact of social media on gastroenterologists in the United States. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:258-9.

9. Chiang A.L., Vartabedian B., Spiegel B. Harnessing the hashtag: a standard approach to GI dialogue on social media. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1082-4.

10. Reich J., Guo L., Hall J., et al. A survey of social media use and preferences in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2678-87.

11. Timms C., Forton D.M., Poullis A. Social media use in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and chronic viral hepatitis. Clin Med. 2014;14:215.

12. Prasad B. Social media, health care, and social networking. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:492-5.

13. Farnan J.M., Snyder Sulmasy L., Worster B.K., et al. Online medical professionalism: patient and public relationships: policy statement from the American College of Physicians and the Federation of State Medical Boards. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:620-7.

14. Cabrera D., Vartabedian B.S., Spinner R.J., et al. More than likes and tweets: creating social media portfolios for academic promotion and tenure. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:421-5.

15. Cabrera D. Mayo Clinic includes social media scholarship activities in academic advancement. Available from https://socialmedia.mayoclinic.org/2016/05/25/mayo-clinic-includes-social-media-scholarship-activities-in-academic-advancement/

Date: May 26, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

16. Freitag C.E., Arnold M.A., Gardner J.M., et al. If you are not on social media, here’s what you’re missing! #DoTheThing. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2017; (Epub ahead of print).

17. Stukus D.R. How I used twitter to get promoted in academic medicine. Available from http://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2016/10/used-twitter-get-promoted-academic-medicine.html. Date: October 9, 2016. (Accessed: July 1, 2017).

Dr. Gray is in the division of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of medicine, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus; Dr. Fisher is in the division of gastroenterology, department of medicine, Duke University, Durham, N.C. The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Social media use is ubiquitous and, in the digital age, it is the ascendant form of communication. Individuals and organizations, digital immigrants (those born before the widespread adoption of digital technology), and digital natives alike are leveraging social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and LinkedIn, to curate, consume, and share information across the spectrum of demographics and target audiences. In the United States, 7 in 10 Americans are using social media and, although young adults were early adopters, use among older adults is increasing rapidly.1

Furthermore, social media has cultivated remarkable opportunities in the dissemination of health information and disrupted traditional methods of patient–provider communication. The days when medically trained health professionals were the gatekeepers of health information are long gone. Approximately 50% of Americans seek health information online before seeing a physician.2 Patients and other consumers regularly access social media to search for information about diseases and treatments, engage with other patients, identify providers, and to express or rate their satisfaction with providers, clinics, and health systems.3-5 In addition, they trust online health information from doctors more than that from hospitals, health insurers, and drug companies.6 Not surprisingly, this has led to tremendous growth in use of social media by health care providers, hospitals, and health centers. More than 90% of US hospitals have a Facebook page and 50% have a Twitter account.7

There is ample opportunity to close the gap between patient and health care provider engagement in Social media, equip providers with the tools they need to be competent consumers and sharers of information in this digital exchange, and increase the pool of evidence-based information on GI and liver diseases on social media.12 However, there is limited published literature tailored to gastroenterologists and hepatologists. The goal of this article, therefore, is to provide a broad overview of best practices in the professional use of social media and highlight examples of novel applications in clinical practice.

Best practices: Getting started and maintaining a presence on social media

Social media can magnify your professional image, amplify your voice, and extend your reach and influence much faster than other methods. It also can be damaging if not used responsibly. Thus, we recommend the following approaches to responsible use of social media and cultivating your social media presence based on current evidence, professional organizations’ policy statements, and our combined experience. We initially presented these strategies during a Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Disease Week® in Chicago (http://www.ddw.org/education/session-recordings).

Second, as with other aspects of medical training and practice, find a mentor to provide hands-on advice. This is particularly true if your general familiarity with the social media platforms is limited. If this is not available through your network of colleagues or workplace, we recommend exploring opportunities offered through your professional organization(s) such as the aforementioned Meet-the-Professor Luncheon at Digestive Diseases Week.

Third, know the privacy setting options on your social media platform(s) of choice and use them to your advantage. For example, on Facebook and Twitter, you can select an option that requests your permission before a friend or follower is added to your network. You also can tailor who (such as friends or followers only) can access your posted content directly. However, know that your content still may be made public if it is shared by one of your friends or followers.

Fourth, nurture your social media presence by sharing credible content deliberately, regularly, and, when appropriate, with attribution.

Fifth, diversify your content within the realm of your predefined objectives and/or goals and avoid a singular focus of self-promotion or the appearance of self-promotion. Top social media users suggest, and the authors agree, that your content should be only 25%-33% of your posts.