User login

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

The Medicare Access and Chips Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is now law; it passed with bipartisan, virtually unanimous support in both chambers of Congress. MACRA replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate formula for physician reimbursement and replaced it with a pathway to value-based payment. This law will alter our practices more than the Affordable Care Act and to an extent not seen since the passage of the original Medicare Act. Practices that continue to hang on to our traditional colonoscopy-based fee-for-service reimbursement model will increasingly be marginalized (or discounted) by Medicare, commercial payers, and regional health systems. To thrive in the coming decade, innovative practices will move toward alternative payment models. Many practices have risk-linked bundled payments for colonoscopy, but this step is only for the interim. Long-term success will come to practices that understand the implications of episode payments, specialty medical homes, and total cost of care. Do not wait for the finances to magically appear – start now to build infrastructure. In this month’s article, Dr. Mehta provides a detailed description of how a practice might construct a bundled payment for a common inpatient disorder. No one is paying for this yet, but it will come. Now is not the time to be a “WIMP” (Gastroenterology. 2016;150:295-9).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. This payment model aims to improve the value of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries for hip and knee replacement surgery during the inpatient stay and 90-day period after discharge by holding hospitals accountable for cost and quality.1 It includes hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the United States and marks the first time that a postacute bundled payment model is mandatory for traditional Medicare patients. Although this may not seem to be relevant for gastroenterology, it marks an important signal by CMS that there will likely be more episode-payment models in the future.

Gastroenterologists have not been primary drivers or participants in these models, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage is included as 1 of the 48 clinical conditions for the postacute bundled payment program. In addition, CMS recently announced that clinical episode-based payment for GI hemorrhage will be included in hospital inpatient quality reporting (IQR) for fiscal year 2019.4 This is an opportunity for the field of gastroenterology to take a leadership role in an alternate payment model as it has for colonoscopy bundled payment,5 but it requires an understanding of the history of postacute bundled payments and the opportunities for and challenges to applying this model to GI hemorrhage. In this article, I will describe insights from our health system’s experience in evaluating different postacute bundled payment programs and participating in a GI bundled payment program.

Inpatient and postacute bundled payments

A bundled payment refers to a situation in which hospitals and physicians are incentivized to coordinate care for an episode of care across the continuum and eliminate unnecessary spending. In 1983, Medicare initiated a type of bundled payment for Part A spending on inpatient hospital care by creating prospective payment that is based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). This was a response to the rising cost of inpatient care resulting from retrospective payment that is based on hospital charges. Because hospitals would get paid the same amount for similar conditions, it resulted in shortened length of stay and reduction in the rise of inpatient costs, along with no measurable impact on quality of care.6 This was followed by prospective payment for outpatient hospital fees and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Medicare built on this by bundling physician and hospital fees through demonstration projects in coronary artery bypass graft surgery from 1991 to 1996 and orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery from 2009 to 2012, both resulting in reduced costs and no measurable impact on quality.

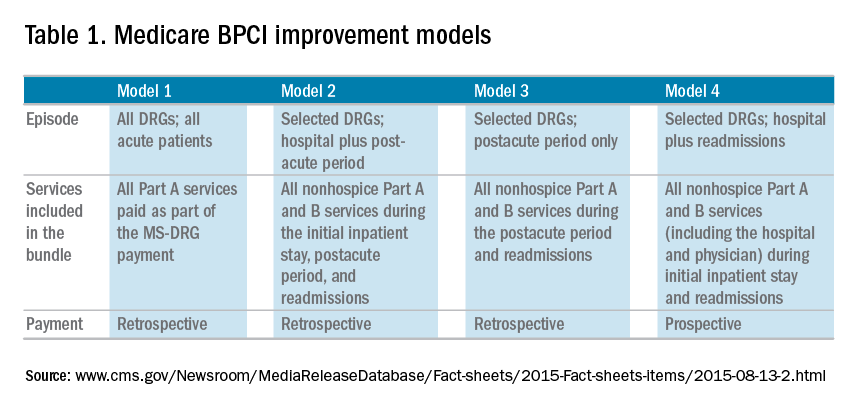

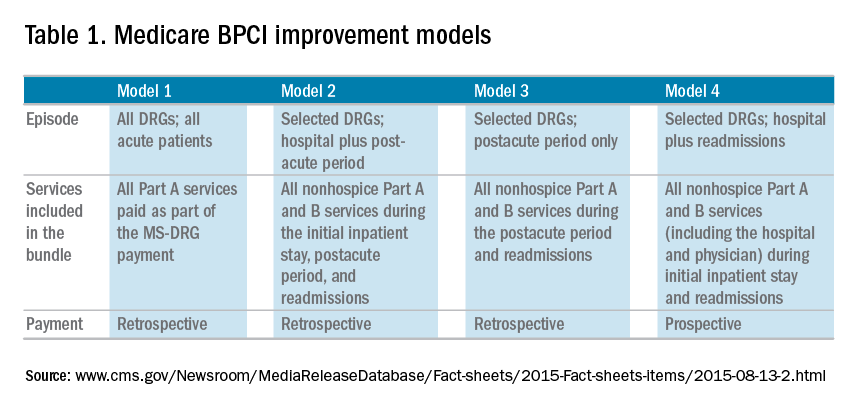

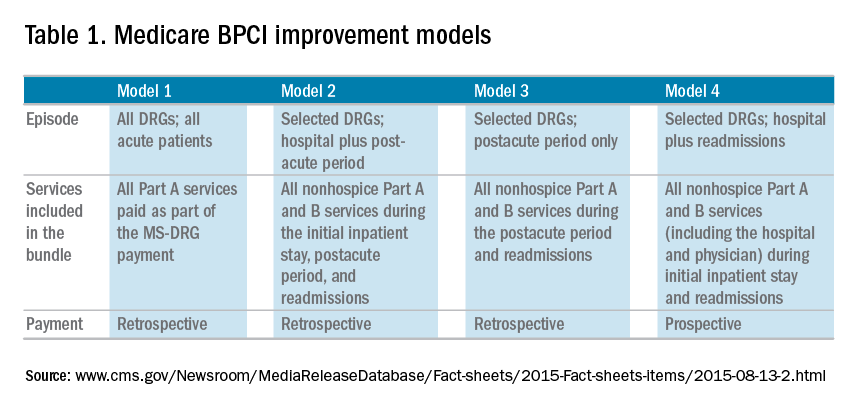

The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program built on these results in 2013 by expanding to include Part A and B services rendered up to 90 days after discharge, and as of January 2016, it includes 1,574 participants across the country. On a voluntary basis, hospitals, physician groups, and postacute providers and conveners were able to participate in 1 of 4 bundled payment models that were anchored on an inpatient for any of 48 clinical conditions that were based on MS-DRG (Table 1).

• Model 1 defined the episode as the inpatient hospital stay and bundled the facility and physician fees, similar to prior demonstration projects.

• Model 2 is a retrospective bundled payment for Part A and B services in the inpatient hospital stay and up to 90 days after discharge.

• Model 3 is a retrospective model that starts after hospital discharge and includes up to 90 days. (Models 1-3 maintain the current payment structure and retrospectively compare the actual reimbursement with target values that are based on historical data for that hospital with a 2%-3% payment reduction.)

• Model 4 makes a single, prospectively determined global payment to a hospital that encompasses all services during the hospital stay.

Opportunities in inpatient and postacute bundled payments

Participation in bundled payments requires a new set of analytic and organizational capabilities.

• The first step is to identify the patient population on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and to measure the current cost of care through external claims data and internal hospital data. This includes payments for hospital inpatient services, physician fees, postacute care, readmissions, other Part B services, and home health services. The biggest opportunity for postacute bundles is shifting site of service from postacute care to lower-cost settings and reducing readmission rates.

• Subsequently, they need to identify areas of opportunity to reduce expenditure, while also demonstrating consistent or improved quality and outcomes.

• On the basis of this, the team can identify variation in care within the cohort and in comparison with benchmarks across the country.

• After identifying areas of opportunity, the team needs to develop strategies to improve value such as care pathways, information technology tools, care coordination, and remote services.

Of the 48 clinical conditions in BPCI, 4 could be described as related to GI: esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders (Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Group [MS-DRG] 391, 392); gastrointestinal hemorrhage (MS-DRG 377, 378, 379); gastrointestinal obstruction (MS-DRG 388, 389, 390); and major bowel procedure (MS-DRG 329, 330, 331). After evaluating the GI bundles, it was apparent that these were created for billing purposes and were not clinically intuitive, which is why our institution immediately excluded the broad category of esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders. GI obstruction and major bowel surgery relate to the care of gastroenterologists, but surgeons are typically primary drivers of care for these patients. Thus, we believed that GI hemorrhage was most appropriate because gastroenterologists drive care for this condition, and there is substantial evidence about established guidelines and pathways during this episode.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

We built a multidisciplinary team of physicians, data analysts, clinical documentation specialists, and care managers to start developing a plan for improving the value of care in this population. This included data about readmissions and site of postacute care for this population, which were supplemented by chart review of financial outliers and readmissions. We quickly learned about some of the challenges to medical bundles and the GI hemorrhage bundle in particular. It is difficult to identify these patients early in the hospital stay because inclusion is based on a billing code. Many of these patients also have cardiovascular disease, cancer, or cirrhosis, which makes it hard to identify which patients will end up with primary GI hemorrhage coding until after the patient is discharged. They are also on many different inpatient services; in our hospital, there were at least 12 different admitting services. In addition, almost one-third of the patients actually had an admission before this hospitalization, often for different clinical conditions.

Most importantly, it was very challenging to develop protocols to improve the value of care in this population. Most of the patients had many comorbid conditions, so a GI hemorrhage pathway alone would not be sufficient to alter care. The two main areas of opportunity for cost savings in postacute bundled payments are postacute site of service and readmissions, both of which are hard to change for medical GI patients. For medical patients, they have many comorbidities before admission, so postacute site of service is typically driven by which site they were admitted from. This is different from surgical patients who are in SNF or rehabilitation facilities for limited time frames, and there may be more discretion to shift to lower cost settings. In addition, readmissions have not been studied much in GI hemorrhage, so it is not clear how to improve them. On the basis of these factors and the limited sample size for this condition, our health system opted to stop taking financial risk for this population.

Future opportunities for gastroenterology

However, the latest CMS Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule describes the implementation of a new quality metric for hospital IQR called the Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-Based Payment. This would hold hospitals accountable for the cost of care for GI hemorrhage admissions plus the 90 days after discharge, similar to model 2 of BPCI. This announcement, as well as the launch of mandatory orthopedic bundles, demonstrates that hospital reimbursement is shifting toward an expansion of bundled payments to include the postacute time frame. This is manifested in postacute bundles, episode-based payment, and readmission penalties. This reignited our GI hemorrhage episode team’s efforts, but with a broader purpose.

Gastroenterologists can take a leadership role in responding to episode-based payments as a way for us to demonstrate value in our collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and payers. The focus on cardiovascular disease as part of readmission penalties and core measures has allowed our cardiology colleagues to partner closely with service lines, learn about episode-based care, and garner resources to build and lead disease and episode teams. Because patients do not fit into the different clinical areas in mutually exclusive categories, we will need to collaborate with other specialties to care for the overlap with other conditions. Many heart failure and myocardial infarction patients will get readmitted for GI hemorrhage, and many GI hemorrhage patients will have concomitant cardiovascular disease or cancer. This suggests that future strategies need to integrate efforts of service lines and that there is greater opportunity for gastroenterologists than just the GI bundles.

Gastroenterologists should also participate in a proactive way. Any new payment mechanism will have some flaws in implementation, so it is more important to do what is right from a clinical standpoint rather than focusing too much on the specific billing code or payment model. These models are evolving, and we have an opportunity to have impact on future implementation. This starts with identifying and including patients from a clinical perspective rather than focusing on specific insurance types that participate in bundled payments. Some examples to improve the value of care in GI hemorrhage include creating evidence-based care pathways that span the episode of care, structured documentation after endoscopy for risk stratification, integrating pathways into the workflow of providers through the electronic health record, and increased coordination between specialties across the continuum of care. Other diagnoses that might be included in future bundles include cirrhosis, bowel obstruction, and inflammatory bowel disease. We can also learn from successful efforts in other clinical specialties that have identified variations in care and implemented a multi-modal strategy to improving care and measuring impact.

References

1. Mechanic, R.E. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment: Is it ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373[14]:1291-3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. January 26, 2015. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

3. Patel, K., Presser, E., George, M., et al. Shifting away from fee-for-service: Alternative approaches to payment in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14[4]:497-506.

4. Medicare FY 2016 IPPS final rule. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2016-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

5. Ketover, S.R. Bundled payment for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11[5]:454-7.

6. Coulam, R.F., Gaumer, G.L. Medicare’s prospective payment system: a critical appraisal. Health Care Financ Rev Annu Suppl. 1991:45-77.

Dr. Mehta is in the division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The author discloses no conflicts of interest.

The Medicare Access and Chips Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is now law; it passed with bipartisan, virtually unanimous support in both chambers of Congress. MACRA replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate formula for physician reimbursement and replaced it with a pathway to value-based payment. This law will alter our practices more than the Affordable Care Act and to an extent not seen since the passage of the original Medicare Act. Practices that continue to hang on to our traditional colonoscopy-based fee-for-service reimbursement model will increasingly be marginalized (or discounted) by Medicare, commercial payers, and regional health systems. To thrive in the coming decade, innovative practices will move toward alternative payment models. Many practices have risk-linked bundled payments for colonoscopy, but this step is only for the interim. Long-term success will come to practices that understand the implications of episode payments, specialty medical homes, and total cost of care. Do not wait for the finances to magically appear – start now to build infrastructure. In this month’s article, Dr. Mehta provides a detailed description of how a practice might construct a bundled payment for a common inpatient disorder. No one is paying for this yet, but it will come. Now is not the time to be a “WIMP” (Gastroenterology. 2016;150:295-9).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. This payment model aims to improve the value of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries for hip and knee replacement surgery during the inpatient stay and 90-day period after discharge by holding hospitals accountable for cost and quality.1 It includes hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the United States and marks the first time that a postacute bundled payment model is mandatory for traditional Medicare patients. Although this may not seem to be relevant for gastroenterology, it marks an important signal by CMS that there will likely be more episode-payment models in the future.

Gastroenterologists have not been primary drivers or participants in these models, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage is included as 1 of the 48 clinical conditions for the postacute bundled payment program. In addition, CMS recently announced that clinical episode-based payment for GI hemorrhage will be included in hospital inpatient quality reporting (IQR) for fiscal year 2019.4 This is an opportunity for the field of gastroenterology to take a leadership role in an alternate payment model as it has for colonoscopy bundled payment,5 but it requires an understanding of the history of postacute bundled payments and the opportunities for and challenges to applying this model to GI hemorrhage. In this article, I will describe insights from our health system’s experience in evaluating different postacute bundled payment programs and participating in a GI bundled payment program.

Inpatient and postacute bundled payments

A bundled payment refers to a situation in which hospitals and physicians are incentivized to coordinate care for an episode of care across the continuum and eliminate unnecessary spending. In 1983, Medicare initiated a type of bundled payment for Part A spending on inpatient hospital care by creating prospective payment that is based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). This was a response to the rising cost of inpatient care resulting from retrospective payment that is based on hospital charges. Because hospitals would get paid the same amount for similar conditions, it resulted in shortened length of stay and reduction in the rise of inpatient costs, along with no measurable impact on quality of care.6 This was followed by prospective payment for outpatient hospital fees and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Medicare built on this by bundling physician and hospital fees through demonstration projects in coronary artery bypass graft surgery from 1991 to 1996 and orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery from 2009 to 2012, both resulting in reduced costs and no measurable impact on quality.

The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program built on these results in 2013 by expanding to include Part A and B services rendered up to 90 days after discharge, and as of January 2016, it includes 1,574 participants across the country. On a voluntary basis, hospitals, physician groups, and postacute providers and conveners were able to participate in 1 of 4 bundled payment models that were anchored on an inpatient for any of 48 clinical conditions that were based on MS-DRG (Table 1).

• Model 1 defined the episode as the inpatient hospital stay and bundled the facility and physician fees, similar to prior demonstration projects.

• Model 2 is a retrospective bundled payment for Part A and B services in the inpatient hospital stay and up to 90 days after discharge.

• Model 3 is a retrospective model that starts after hospital discharge and includes up to 90 days. (Models 1-3 maintain the current payment structure and retrospectively compare the actual reimbursement with target values that are based on historical data for that hospital with a 2%-3% payment reduction.)

• Model 4 makes a single, prospectively determined global payment to a hospital that encompasses all services during the hospital stay.

Opportunities in inpatient and postacute bundled payments

Participation in bundled payments requires a new set of analytic and organizational capabilities.

• The first step is to identify the patient population on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and to measure the current cost of care through external claims data and internal hospital data. This includes payments for hospital inpatient services, physician fees, postacute care, readmissions, other Part B services, and home health services. The biggest opportunity for postacute bundles is shifting site of service from postacute care to lower-cost settings and reducing readmission rates.

• Subsequently, they need to identify areas of opportunity to reduce expenditure, while also demonstrating consistent or improved quality and outcomes.

• On the basis of this, the team can identify variation in care within the cohort and in comparison with benchmarks across the country.

• After identifying areas of opportunity, the team needs to develop strategies to improve value such as care pathways, information technology tools, care coordination, and remote services.

Of the 48 clinical conditions in BPCI, 4 could be described as related to GI: esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders (Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Group [MS-DRG] 391, 392); gastrointestinal hemorrhage (MS-DRG 377, 378, 379); gastrointestinal obstruction (MS-DRG 388, 389, 390); and major bowel procedure (MS-DRG 329, 330, 331). After evaluating the GI bundles, it was apparent that these were created for billing purposes and were not clinically intuitive, which is why our institution immediately excluded the broad category of esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders. GI obstruction and major bowel surgery relate to the care of gastroenterologists, but surgeons are typically primary drivers of care for these patients. Thus, we believed that GI hemorrhage was most appropriate because gastroenterologists drive care for this condition, and there is substantial evidence about established guidelines and pathways during this episode.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

We built a multidisciplinary team of physicians, data analysts, clinical documentation specialists, and care managers to start developing a plan for improving the value of care in this population. This included data about readmissions and site of postacute care for this population, which were supplemented by chart review of financial outliers and readmissions. We quickly learned about some of the challenges to medical bundles and the GI hemorrhage bundle in particular. It is difficult to identify these patients early in the hospital stay because inclusion is based on a billing code. Many of these patients also have cardiovascular disease, cancer, or cirrhosis, which makes it hard to identify which patients will end up with primary GI hemorrhage coding until after the patient is discharged. They are also on many different inpatient services; in our hospital, there were at least 12 different admitting services. In addition, almost one-third of the patients actually had an admission before this hospitalization, often for different clinical conditions.

Most importantly, it was very challenging to develop protocols to improve the value of care in this population. Most of the patients had many comorbid conditions, so a GI hemorrhage pathway alone would not be sufficient to alter care. The two main areas of opportunity for cost savings in postacute bundled payments are postacute site of service and readmissions, both of which are hard to change for medical GI patients. For medical patients, they have many comorbidities before admission, so postacute site of service is typically driven by which site they were admitted from. This is different from surgical patients who are in SNF or rehabilitation facilities for limited time frames, and there may be more discretion to shift to lower cost settings. In addition, readmissions have not been studied much in GI hemorrhage, so it is not clear how to improve them. On the basis of these factors and the limited sample size for this condition, our health system opted to stop taking financial risk for this population.

Future opportunities for gastroenterology

However, the latest CMS Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule describes the implementation of a new quality metric for hospital IQR called the Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-Based Payment. This would hold hospitals accountable for the cost of care for GI hemorrhage admissions plus the 90 days after discharge, similar to model 2 of BPCI. This announcement, as well as the launch of mandatory orthopedic bundles, demonstrates that hospital reimbursement is shifting toward an expansion of bundled payments to include the postacute time frame. This is manifested in postacute bundles, episode-based payment, and readmission penalties. This reignited our GI hemorrhage episode team’s efforts, but with a broader purpose.

Gastroenterologists can take a leadership role in responding to episode-based payments as a way for us to demonstrate value in our collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and payers. The focus on cardiovascular disease as part of readmission penalties and core measures has allowed our cardiology colleagues to partner closely with service lines, learn about episode-based care, and garner resources to build and lead disease and episode teams. Because patients do not fit into the different clinical areas in mutually exclusive categories, we will need to collaborate with other specialties to care for the overlap with other conditions. Many heart failure and myocardial infarction patients will get readmitted for GI hemorrhage, and many GI hemorrhage patients will have concomitant cardiovascular disease or cancer. This suggests that future strategies need to integrate efforts of service lines and that there is greater opportunity for gastroenterologists than just the GI bundles.

Gastroenterologists should also participate in a proactive way. Any new payment mechanism will have some flaws in implementation, so it is more important to do what is right from a clinical standpoint rather than focusing too much on the specific billing code or payment model. These models are evolving, and we have an opportunity to have impact on future implementation. This starts with identifying and including patients from a clinical perspective rather than focusing on specific insurance types that participate in bundled payments. Some examples to improve the value of care in GI hemorrhage include creating evidence-based care pathways that span the episode of care, structured documentation after endoscopy for risk stratification, integrating pathways into the workflow of providers through the electronic health record, and increased coordination between specialties across the continuum of care. Other diagnoses that might be included in future bundles include cirrhosis, bowel obstruction, and inflammatory bowel disease. We can also learn from successful efforts in other clinical specialties that have identified variations in care and implemented a multi-modal strategy to improving care and measuring impact.

References

1. Mechanic, R.E. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment: Is it ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373[14]:1291-3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. January 26, 2015. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

3. Patel, K., Presser, E., George, M., et al. Shifting away from fee-for-service: Alternative approaches to payment in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14[4]:497-506.

4. Medicare FY 2016 IPPS final rule. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2016-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

5. Ketover, S.R. Bundled payment for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11[5]:454-7.

6. Coulam, R.F., Gaumer, G.L. Medicare’s prospective payment system: a critical appraisal. Health Care Financ Rev Annu Suppl. 1991:45-77.

Dr. Mehta is in the division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The author discloses no conflicts of interest.

The Medicare Access and Chips Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is now law; it passed with bipartisan, virtually unanimous support in both chambers of Congress. MACRA replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate formula for physician reimbursement and replaced it with a pathway to value-based payment. This law will alter our practices more than the Affordable Care Act and to an extent not seen since the passage of the original Medicare Act. Practices that continue to hang on to our traditional colonoscopy-based fee-for-service reimbursement model will increasingly be marginalized (or discounted) by Medicare, commercial payers, and regional health systems. To thrive in the coming decade, innovative practices will move toward alternative payment models. Many practices have risk-linked bundled payments for colonoscopy, but this step is only for the interim. Long-term success will come to practices that understand the implications of episode payments, specialty medical homes, and total cost of care. Do not wait for the finances to magically appear – start now to build infrastructure. In this month’s article, Dr. Mehta provides a detailed description of how a practice might construct a bundled payment for a common inpatient disorder. No one is paying for this yet, but it will come. Now is not the time to be a “WIMP” (Gastroenterology. 2016;150:295-9).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. This payment model aims to improve the value of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries for hip and knee replacement surgery during the inpatient stay and 90-day period after discharge by holding hospitals accountable for cost and quality.1 It includes hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the United States and marks the first time that a postacute bundled payment model is mandatory for traditional Medicare patients. Although this may not seem to be relevant for gastroenterology, it marks an important signal by CMS that there will likely be more episode-payment models in the future.

Gastroenterologists have not been primary drivers or participants in these models, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage is included as 1 of the 48 clinical conditions for the postacute bundled payment program. In addition, CMS recently announced that clinical episode-based payment for GI hemorrhage will be included in hospital inpatient quality reporting (IQR) for fiscal year 2019.4 This is an opportunity for the field of gastroenterology to take a leadership role in an alternate payment model as it has for colonoscopy bundled payment,5 but it requires an understanding of the history of postacute bundled payments and the opportunities for and challenges to applying this model to GI hemorrhage. In this article, I will describe insights from our health system’s experience in evaluating different postacute bundled payment programs and participating in a GI bundled payment program.

Inpatient and postacute bundled payments

A bundled payment refers to a situation in which hospitals and physicians are incentivized to coordinate care for an episode of care across the continuum and eliminate unnecessary spending. In 1983, Medicare initiated a type of bundled payment for Part A spending on inpatient hospital care by creating prospective payment that is based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). This was a response to the rising cost of inpatient care resulting from retrospective payment that is based on hospital charges. Because hospitals would get paid the same amount for similar conditions, it resulted in shortened length of stay and reduction in the rise of inpatient costs, along with no measurable impact on quality of care.6 This was followed by prospective payment for outpatient hospital fees and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Medicare built on this by bundling physician and hospital fees through demonstration projects in coronary artery bypass graft surgery from 1991 to 1996 and orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery from 2009 to 2012, both resulting in reduced costs and no measurable impact on quality.

The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program built on these results in 2013 by expanding to include Part A and B services rendered up to 90 days after discharge, and as of January 2016, it includes 1,574 participants across the country. On a voluntary basis, hospitals, physician groups, and postacute providers and conveners were able to participate in 1 of 4 bundled payment models that were anchored on an inpatient for any of 48 clinical conditions that were based on MS-DRG (Table 1).

• Model 1 defined the episode as the inpatient hospital stay and bundled the facility and physician fees, similar to prior demonstration projects.

• Model 2 is a retrospective bundled payment for Part A and B services in the inpatient hospital stay and up to 90 days after discharge.

• Model 3 is a retrospective model that starts after hospital discharge and includes up to 90 days. (Models 1-3 maintain the current payment structure and retrospectively compare the actual reimbursement with target values that are based on historical data for that hospital with a 2%-3% payment reduction.)

• Model 4 makes a single, prospectively determined global payment to a hospital that encompasses all services during the hospital stay.

Opportunities in inpatient and postacute bundled payments

Participation in bundled payments requires a new set of analytic and organizational capabilities.

• The first step is to identify the patient population on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and to measure the current cost of care through external claims data and internal hospital data. This includes payments for hospital inpatient services, physician fees, postacute care, readmissions, other Part B services, and home health services. The biggest opportunity for postacute bundles is shifting site of service from postacute care to lower-cost settings and reducing readmission rates.

• Subsequently, they need to identify areas of opportunity to reduce expenditure, while also demonstrating consistent or improved quality and outcomes.

• On the basis of this, the team can identify variation in care within the cohort and in comparison with benchmarks across the country.

• After identifying areas of opportunity, the team needs to develop strategies to improve value such as care pathways, information technology tools, care coordination, and remote services.

Of the 48 clinical conditions in BPCI, 4 could be described as related to GI: esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders (Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Group [MS-DRG] 391, 392); gastrointestinal hemorrhage (MS-DRG 377, 378, 379); gastrointestinal obstruction (MS-DRG 388, 389, 390); and major bowel procedure (MS-DRG 329, 330, 331). After evaluating the GI bundles, it was apparent that these were created for billing purposes and were not clinically intuitive, which is why our institution immediately excluded the broad category of esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders. GI obstruction and major bowel surgery relate to the care of gastroenterologists, but surgeons are typically primary drivers of care for these patients. Thus, we believed that GI hemorrhage was most appropriate because gastroenterologists drive care for this condition, and there is substantial evidence about established guidelines and pathways during this episode.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

We built a multidisciplinary team of physicians, data analysts, clinical documentation specialists, and care managers to start developing a plan for improving the value of care in this population. This included data about readmissions and site of postacute care for this population, which were supplemented by chart review of financial outliers and readmissions. We quickly learned about some of the challenges to medical bundles and the GI hemorrhage bundle in particular. It is difficult to identify these patients early in the hospital stay because inclusion is based on a billing code. Many of these patients also have cardiovascular disease, cancer, or cirrhosis, which makes it hard to identify which patients will end up with primary GI hemorrhage coding until after the patient is discharged. They are also on many different inpatient services; in our hospital, there were at least 12 different admitting services. In addition, almost one-third of the patients actually had an admission before this hospitalization, often for different clinical conditions.

Most importantly, it was very challenging to develop protocols to improve the value of care in this population. Most of the patients had many comorbid conditions, so a GI hemorrhage pathway alone would not be sufficient to alter care. The two main areas of opportunity for cost savings in postacute bundled payments are postacute site of service and readmissions, both of which are hard to change for medical GI patients. For medical patients, they have many comorbidities before admission, so postacute site of service is typically driven by which site they were admitted from. This is different from surgical patients who are in SNF or rehabilitation facilities for limited time frames, and there may be more discretion to shift to lower cost settings. In addition, readmissions have not been studied much in GI hemorrhage, so it is not clear how to improve them. On the basis of these factors and the limited sample size for this condition, our health system opted to stop taking financial risk for this population.

Future opportunities for gastroenterology

However, the latest CMS Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule describes the implementation of a new quality metric for hospital IQR called the Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-Based Payment. This would hold hospitals accountable for the cost of care for GI hemorrhage admissions plus the 90 days after discharge, similar to model 2 of BPCI. This announcement, as well as the launch of mandatory orthopedic bundles, demonstrates that hospital reimbursement is shifting toward an expansion of bundled payments to include the postacute time frame. This is manifested in postacute bundles, episode-based payment, and readmission penalties. This reignited our GI hemorrhage episode team’s efforts, but with a broader purpose.

Gastroenterologists can take a leadership role in responding to episode-based payments as a way for us to demonstrate value in our collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and payers. The focus on cardiovascular disease as part of readmission penalties and core measures has allowed our cardiology colleagues to partner closely with service lines, learn about episode-based care, and garner resources to build and lead disease and episode teams. Because patients do not fit into the different clinical areas in mutually exclusive categories, we will need to collaborate with other specialties to care for the overlap with other conditions. Many heart failure and myocardial infarction patients will get readmitted for GI hemorrhage, and many GI hemorrhage patients will have concomitant cardiovascular disease or cancer. This suggests that future strategies need to integrate efforts of service lines and that there is greater opportunity for gastroenterologists than just the GI bundles.

Gastroenterologists should also participate in a proactive way. Any new payment mechanism will have some flaws in implementation, so it is more important to do what is right from a clinical standpoint rather than focusing too much on the specific billing code or payment model. These models are evolving, and we have an opportunity to have impact on future implementation. This starts with identifying and including patients from a clinical perspective rather than focusing on specific insurance types that participate in bundled payments. Some examples to improve the value of care in GI hemorrhage include creating evidence-based care pathways that span the episode of care, structured documentation after endoscopy for risk stratification, integrating pathways into the workflow of providers through the electronic health record, and increased coordination between specialties across the continuum of care. Other diagnoses that might be included in future bundles include cirrhosis, bowel obstruction, and inflammatory bowel disease. We can also learn from successful efforts in other clinical specialties that have identified variations in care and implemented a multi-modal strategy to improving care and measuring impact.

References

1. Mechanic, R.E. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment: Is it ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373[14]:1291-3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. January 26, 2015. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

3. Patel, K., Presser, E., George, M., et al. Shifting away from fee-for-service: Alternative approaches to payment in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14[4]:497-506.

4. Medicare FY 2016 IPPS final rule. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2016-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

5. Ketover, S.R. Bundled payment for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11[5]:454-7.

6. Coulam, R.F., Gaumer, G.L. Medicare’s prospective payment system: a critical appraisal. Health Care Financ Rev Annu Suppl. 1991:45-77.

Dr. Mehta is in the division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The author discloses no conflicts of interest.

Building a cancer genetics and prevention program

Gastroenterologists offer more than just high-quality colonoscopy for colon cancer prevention. We often are the specialists who first recognize a genetic cancer syndrome during our endoscopy or clinic sessions. The patient who piqued my interest in colon cancer genetics was a 24-year-old woman who was referred for postoperative nausea after a hysterectomy for early stage uterine cancer (that alone should have raised alarm bells). Endoscopy revealed (by happenstance) a stomach coated with polyps. This led to a colonoscopy and diagnosis of familial adenomatous polyposis (uterine cancer within FAP is unusual but reported, for those of you studying for boards). In 1991, no coordinated genetics program existed within my practice so I arranged referrals to genetic counselors, surgeons, and pathologists. This led to the discovery of FAP and early stage (and curable) cancers in her two brothers and her father, in addition to extended pedigree analysis that established multi-organ cancer risks in other relatives. Years later, she brought her two adopted children to meet me and told me of lighting candles in my honor during an American Cancer Society walk. This is why we become doctors.

In this column, Dr. Xavier Llor describes the cancer genetics program he and others have built at Yale. It provides practical steps that can be taken by health system or community-based gastroenterologists to recognize and manage these complex syndromes. We are the specialists on the front lines and Dr. Llor helps us provide the coordinated care our patients expect from us.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Among all common cancers, breast and colon have the highest percentage of cases that are due to hereditary syndromes. Many of the responsible genes have been identified, and the last few years have seen an increase in uptake of genetic testing supported by the refinement of the clinical criteria suggestive of these syndromes as well as the clear improvement in outcomes as a result of the adoption of cancer preventive measures in mutation carriers.1 In spite of this, genetic testing for colorectal cancer (CRC) syndromes is not ordered as often as it should be according to the prevalence of these syndromes.2 In contrast, testing for hereditary breast cancer has become more generalized, and the threshold for ordering genetic testing in the latter is often lower than for CRC. The are several reasons for this: 1) much greater awareness, by both providers and the general public, of hereditary breast cancer conditions; 2) fewer providers with expertise in CRC genetics; 3) lack of a systematic approach to identify patients with potential CRC syndromes; and 4) absence of a clear premorbid phenotype for the most common of all CRC syndromes, Lynch syndrome.3

The recent recommendation in practice guidelines to screen all CRC tumors for Lynch syndrome either with immunohistochemistry to evaluate mismatch repair (MMR) protein expression or through tandem repeat analysis to test for microsatellite instability4 has highlighted that about 10% of all CRCs (a percentage consistently seen in different ethnic groups5) need further cancer genetic evaluation, and many will require sequencing of germline DNA. Although data on cost-effectiveness of this approach are somewhat conflicting,6,7 it is sensible because it is systematic, and studies have shown an increase in diagnostic yield through universal tumor screening.8 Unfortunately, in practice, often suspicious tumor testing results are not followed up by cancer genetics referrals, and many patients with CRC syndrome remain undiagnosed.

Patients with oligopolyposis (fewer than 100 polyps over time) also present diagnostic challenges. Some have attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis because of an APC mutation or MUTYH-associated polyposis. Recent findings have revealed other less commonly mutated genes that also result in oligopolyposis and a significant CRC risk: polymerases POLE and POLD1, GREM1, MCM9, or NTHL1. Because of the relatively low number of polyps in many of these syndromes and the lack of a systematic strategy to add up all polyps diagnosed over time, we not uncommonly fail to suspect some polyposis syndromes. Furthermore, the mixed pattern of polyps that is often associated with some of the mentioned mutated genes adds an extra challenge to diagnosing these cases.

Once individuals with CRC syndromes are identified, the challenge is to provide them with the care that they need, because many gastroenterologists, oncologists, and other health care providers are not extremely familiar with the current options for these patients.

In summary, there is a need to find systematic ways to triage and appropriately refer patients with a potential CRC syndrome to cancer genetics specialists so patients and their families can benefit from proper diagnosis and cancer preventive measures.

Building a comprehensive cancer genetics program

Although implementing systematic approaches is key to selecting individuals at risk, the complexity of caring for these patients demands a service that can stand up to the multiple challenges. For instance, most CRC syndromes are in fact multi-cancer syndromes with an increased risk of cancer and other pathologies in different organs beside the colon. Furthermore, the psychological implications of having a heritable cancer condition often take an important toll on affected families, with common feelings of guilt for having passed the mutated genes to the offspring.

Thus, to provide the best care to affected families, there is a tremendous need for well-organized and comprehensive cancer genetics services that are capable of responding to the multiple needs of these families so state-of-the-art cancer preventive measures can be carried out and multilevel support can be provided. The mentioned considerations were the guiding force in the creation of the Smilow Cancer Genetics and Prevention Program (SCGPP) at Yale. Thus, we established a comprehensive program that brings together health professionals specializing in different aspects of these patients’ care that ensures their proper attention in a longitudinal fashion, making the program their home for health care. We integrated in the program, among others, physician leaders in gastrointestinal (GI), breast, gynecological, endocrine, and genitourinary high-risk malignancies; genetic counselors; an advanced practice registered nurse specializing in cancer prevention and risk reduction; and a scientific director who leads the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory at Yale that offers in-house genetic testing, including full exome sequencing. The SCGPP was started in July 2015, and it currently provides more than 250 new consultations per month.

The following are several key elements that I consider important for a cancer genetics program and how they have been addressed at the SCGPP.

Identification through risk stratification

Because the identification of all individuals who can benefit from cancer genetics consultation is complex yet essential, a comprehensive approach with different strategies is often necessary.9 Universal tumor testing is an effective tool, but other complementary approaches such as the use of questionnaires can also contribute to identifying patients in need for cancer genetics assessment. In our program, the pathology department tests for MMR protein expression in all bowel and endometrial tumors. The ones that have loss of expression of an MMR protein are reported to the SCGPP, which contacts the patient’s providers to request a referral. In a relatively short implementation time, this has already resulted in a significant increase in the number of patients referred for cancer genetics consultation and new Lynch syndrome diagnosis. On the other hand, two brief and simplified questionnaires have been developed and distributed in clinics, one for health providers and one administered directly to patients. The questionnaires contain questions related to the patient’s own cancer history, polyp history, cancer screening tests, and family history. The first one assists health care providers in identifying individuals. The second one is completed by patients, collected, and reviewed by a genetic counselor. Suitable patients are invited to a cancer genetics consultation through their primary health care providers. A third questionnaire directed to endoscopy services will be rolled out soon. This collects information on completed endoscopy procedures, polyps and cancers found, and family history.

The program is currently working with information technology to develop a system to pull from the electronic medical record (EMR) relevant information on the patient’s own medical history, family history, and endoscopy findings. A set of criteria has been established so relevant information will generate an alert for prompt referral for the SCGPP.

Because education of health care providers about these conditions is essential to foster collaboration and to help them better understand about cancer risk assessment, genetics, and what the SCGPP can offer to some of their patients, sessions are routinely held with some of them to discuss different aspects on cancer genetics.

In summary, a comprehensive and coordinated approach is key to substantially expand the number of individuals identified and referred for cancer genetics assessment.

Genetic testing

During the last few years we have witnessed changes at different levels around genetic testing that are having a tremendous impact. Some of these changes pose significant new challenges that require rapid adaptation on the providers’ side. Thus, we are quickly moving from single gene testing to panels of genes tested at once. This has resulted in unexpected findings such as mutated genes not initially suspected or variants of unknown significance that often should be interpreted in the context of the personal and family history of cancer because of the lack of definite information on their potential pathogenicity.10 Adding to that, genome-scale tumor sequencing is becoming more common as it increasingly informs on the types of anti-tumor therapies to be selected for a specific patient (precision medicine). This approach is revealing some unexpected information because in some cases it has helped identify significant mutations in the germline.11

Finally, the increasing number of commercial laboratories offering genetic testing has resulted in more competition and lower prices, in some cases to a point that direct-to-consumer charges may be even lower than insurance copayments. This is contributing to a rapid increase in individuals being tested including patients who otherwise would unlikely have been tested in the past because of lack of fulfillment of insurance criteria. The challenge for us is to be ready to help navigate the increasing amount of information obtained as a result of all these changes.

Integration of electronic platforms

In an era of full implementation of EMRs, a cancer genetics program should not simply adapt to the new environment but fully embrace it and explore the possibilities that come with it. Thus, from its inception, the SCGPP has been embracing the electronic platforms to the maximum extent so the clinical operation is streamlined and documentation is well-displayed and accessible in the EMR. The Yale health care system uses EPIC (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as its EMR, and the SCGPP uses Progeny (Progeny Genetics LLC, Delray Beach, FL) to collect data, construct family pedigrees, and build the research registry of the Program. A joint effort by the developers of both systems has resulted in integration at different levels. Thus, after a referral is received, patients are called, registered, and asked several questions including their own cancer and polyp history as well as their family history of cancer. This assists in triaging patients to the most appropriate SCGPP provider: a genetic counselor, a disease physician leader, or a combined visit according to the established internal protocol. In all cases, for new patients with GI cancer syndromes, a combined appointment of a genetic counselor and the GI physician leader is scheduled. At the same time, patients are sent an email with a link to the Progeny online questionnaire that includes personal and family history of cancer as well as extensive clinical information. Once the questionnaire is completed, the program generates a preliminary pedigree that patients can print, and the SCGPP gets a message communicating that the patient has completed this questionnaire. Therefore, when patients are seen on consultation, providers already have the provisional data and pedigree. During the visit, information is verified and edited as needed, and the finalized pedigree goes live through a hyperlink in the EMR. Every revision results in an updated pedigree visible through the mentioned hyperlink. This process saves a considerable amount of time to the providers and increases clinic efficiency.

Informed consent for the research registry is also fully electronic, with signatures recorded in tablets that transmit the signed document to a secure server.

The necessary team approach

Another essential component of a cancer genetics program like this is the integrated and comprehensive approach to patients. Thus, in our Program, the combined appointments for GI patients with the genetic counselor and the physician leader cover all different aspects of care, and a complete plan is suggested and discussed. Once the initial assessment is finalized and genetic testing results (if ordered) are completed, patients are followed prospectively to ensure that prophylactic and cancer prevention measures are undertaken according to the updated standards of care. Complex cases are discussed with the entire team in the weekly case conference that is always followed by a scientific conference with alternating topics such as journal club, practice improvement, ongoing research projects, and extensive case reviews.

Network integration

Although the needs for cancer genetics can be found in any corner of the map, it is not realistic to believe that services like this can be provided in a consistent fashion without being part of a bigger program umbrella. In our case, Yale’s Smilow Cancer Center charged the SCGPP with the duty to provide high quality and consistent cancer genetics services to the entire network that currently includes a total of 5 affiliated hospitals and 10 care centers. To do so, all cases seen outside the main campus are brought up for discussion in the weekly case conference. Furthermore, counselors distributed throughout the network routinely also see patients in the main office, and when away, they participate in case conference and scientific conference via teleconference or videoconference. All this is considered critical to facilitate a cohesive and state-of-the-art program that extends beyond the main campus. Recently, telemedicine is used to provide consultations directly to patients so the program’s services are brought to the most remote locations. A senior genetic counselor is in charge of the network operations to facilitate all these services and help engage providers in the corresponding facilities. She regularly attends tumor board meetings in the local hospitals to help disseminate knowledge in cancer genetics as well as to assist in the identification of patients who can benefit from referral to the SCGPP.

Surveillance and recall program

Key to the success of a cancer genetics program is successfully coordinating care so preventive tests and measures are performed to decrease cancer risk. The SCGPP aims to be the home for familial and hereditary cancer patients. For these patients, this implies a strong commitment to their needs, with a special emphasis on the appropriate prophylactic and cancer surveillance measures. The registry database provides an extremely useful tool to track scheduled tests and procedures and to generate reminders. The advanced practice registered nurse meticulously follows them and ensures proper completion and review. She follows up on the scheduling of the specific tests, reviews results once these tests are completed, and brings them back to discussion with the physician leader. She also follows up on incomplete tests and helps to bring down potential barriers in the performance of these tests. Another key aspect of her job consists of facilitating the assistance of psychological support or risk reduction through lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation or weight reduction, to patients in need of such services.

Cancer genetics research

Key to an academic program in cancer genetics like this one is to facilitate the study of familial and syndromic cancers, including aspects such as phenotype characterization or the efficacy of chemopreventive approaches. To accomplish this, a patient registry is essential. Registries are extremely useful tools that facilitate data accrual and analysis. The SCGPP registry is based on the Progeny suite that incorporates not only clinical and pedigree building components but also the genotype and sample management systems (LAB and LIMS). Thus, a fully searchable and robust database and biological sample repository have been created, and all patients are approached about participating in this institutional review board–approved registry.

Cancer prevention in nonfamilial, nonsyndromic cases

Some nongenetic factors such as diet, physical activity, or toxic exposure seem to underlie the important differences seen in CRC incidence around the world.12 Thus, interventions at this level can potentially have a very high impact for cancer prevention in all individuals. In fact, even individuals with genetic mutations that carry a high risk for developing malignancies can see their risk modified by addressing lifestyle/environmental factors.13 Thus, the SCGPP has created tools for assessment and risk stratification that take the mentioned factors into account and create a roadmap for primary prevention. The tools include questionnaires on all environmental exposures, lifestyle factors, and medications the patient is exposed to and that can influence cancer risk. The information is reviewed in a special clinic session, and all services to help modify risk factors are offered to the patient.

Conclusions

There is a clear need for GI cancer genetics services to reach all patients who can benefit from them, and at the same time the field is rapidly growing in complexity. More than ever, these services demand a multidisciplinary approach, with experts leading the care of these patients in a coordinated fashion with the rest of the health care community. However, payers have not fully recognized these complexities, and some critical aspects such as genetic counseling services are not always properly reimbursed. As we shape up the present and future of health care that should be fully personalized and patient-centered, embracing new ways of delivering it, we need to engage all the players and help them understand what this takes and the rewards in the form of better outcomes that will come with it.

References

1. Kastrinos F., Stoffel E.M. History, genetics, and strategies for cancer prevention in Lynch syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:715-27 (quiz e41-e43).

2. Karlitz J.J., Hsieh M.C., Liu Y., et al. Population-based Lynch syndrome screening by microsatellite instability in patients </=50: prevalence, testing determinants, and result availability prior to colon surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:948-55.

3. Llor X. When should we suspect hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:363-7.

4. Giardiello F.M., Allen J.I., Axilbund J.E., et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-society Task Force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1159-79.

5. Berera S., Koru-Sengul T., Miao F., et al. Colorectal tumors from different racial and ethnic minorities have similar rates of mismatch repair deficiency. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1163-71.

6. Mvundura M., Grosse S.D., Hampel H., et al. The cost-effectiveness of genetic testing strategies for Lynch syndrome among newly diagnosed patients with colorectal cancer. Genet Med. 2010;12:93-104.

7. Barzi A., Sadeghi S., Kattan M.W., et al. Comparative effectiveness of screening strategies for Lynch syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:1-9.

8. Moreira L., Balaguer F., Lindor N., et al. Identification of Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2012;308:1555-65.

9. Stoffel E.M., Kastrinos F. Familial colorectal cancer, beyond Lynch syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1059-68.

10. Desmond A., Kurian A.W., Gabree M., et al. Clinical actionability of multigene panel testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk assessment. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:943-51.

11. Parsons D.W., Roy A., Yang Y., et al. Diagnostic yield of clinical tumor and germline whole-exome sequencing for children with solid tumors. JAMA Oncol. 2016;([Epub ahead of print])

12. Aleksandrova K., Pischon T., Jenab M., et al. Combined impact of healthy lifestyle factors on colorectal cancer: a large European cohort study. BMC Med. 2014;12:168.

13. Movahedi M., Bishop D.T., Macrae F., et al. Obesity, aspirin, and risk of colorectal cancer in carriers of hereditary colorectal cancer: a prospective investigation in the CAPP2 study. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3591-7.

Dr. Llor is in the department of medicine and cancer center, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He discloses no conflicts of interest.

Gastroenterologists offer more than just high-quality colonoscopy for colon cancer prevention. We often are the specialists who first recognize a genetic cancer syndrome during our endoscopy or clinic sessions. The patient who piqued my interest in colon cancer genetics was a 24-year-old woman who was referred for postoperative nausea after a hysterectomy for early stage uterine cancer (that alone should have raised alarm bells). Endoscopy revealed (by happenstance) a stomach coated with polyps. This led to a colonoscopy and diagnosis of familial adenomatous polyposis (uterine cancer within FAP is unusual but reported, for those of you studying for boards). In 1991, no coordinated genetics program existed within my practice so I arranged referrals to genetic counselors, surgeons, and pathologists. This led to the discovery of FAP and early stage (and curable) cancers in her two brothers and her father, in addition to extended pedigree analysis that established multi-organ cancer risks in other relatives. Years later, she brought her two adopted children to meet me and told me of lighting candles in my honor during an American Cancer Society walk. This is why we become doctors.

In this column, Dr. Xavier Llor describes the cancer genetics program he and others have built at Yale. It provides practical steps that can be taken by health system or community-based gastroenterologists to recognize and manage these complex syndromes. We are the specialists on the front lines and Dr. Llor helps us provide the coordinated care our patients expect from us.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

Among all common cancers, breast and colon have the highest percentage of cases that are due to hereditary syndromes. Many of the responsible genes have been identified, and the last few years have seen an increase in uptake of genetic testing supported by the refinement of the clinical criteria suggestive of these syndromes as well as the clear improvement in outcomes as a result of the adoption of cancer preventive measures in mutation carriers.1 In spite of this, genetic testing for colorectal cancer (CRC) syndromes is not ordered as often as it should be according to the prevalence of these syndromes.2 In contrast, testing for hereditary breast cancer has become more generalized, and the threshold for ordering genetic testing in the latter is often lower than for CRC. The are several reasons for this: 1) much greater awareness, by both providers and the general public, of hereditary breast cancer conditions; 2) fewer providers with expertise in CRC genetics; 3) lack of a systematic approach to identify patients with potential CRC syndromes; and 4) absence of a clear premorbid phenotype for the most common of all CRC syndromes, Lynch syndrome.3

The recent recommendation in practice guidelines to screen all CRC tumors for Lynch syndrome either with immunohistochemistry to evaluate mismatch repair (MMR) protein expression or through tandem repeat analysis to test for microsatellite instability4 has highlighted that about 10% of all CRCs (a percentage consistently seen in different ethnic groups5) need further cancer genetic evaluation, and many will require sequencing of germline DNA. Although data on cost-effectiveness of this approach are somewhat conflicting,6,7 it is sensible because it is systematic, and studies have shown an increase in diagnostic yield through universal tumor screening.8 Unfortunately, in practice, often suspicious tumor testing results are not followed up by cancer genetics referrals, and many patients with CRC syndrome remain undiagnosed.

Patients with oligopolyposis (fewer than 100 polyps over time) also present diagnostic challenges. Some have attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis because of an APC mutation or MUTYH-associated polyposis. Recent findings have revealed other less commonly mutated genes that also result in oligopolyposis and a significant CRC risk: polymerases POLE and POLD1, GREM1, MCM9, or NTHL1. Because of the relatively low number of polyps in many of these syndromes and the lack of a systematic strategy to add up all polyps diagnosed over time, we not uncommonly fail to suspect some polyposis syndromes. Furthermore, the mixed pattern of polyps that is often associated with some of the mentioned mutated genes adds an extra challenge to diagnosing these cases.

Once individuals with CRC syndromes are identified, the challenge is to provide them with the care that they need, because many gastroenterologists, oncologists, and other health care providers are not extremely familiar with the current options for these patients.

In summary, there is a need to find systematic ways to triage and appropriately refer patients with a potential CRC syndrome to cancer genetics specialists so patients and their families can benefit from proper diagnosis and cancer preventive measures.

Building a comprehensive cancer genetics program

Although implementing systematic approaches is key to selecting individuals at risk, the complexity of caring for these patients demands a service that can stand up to the multiple challenges. For instance, most CRC syndromes are in fact multi-cancer syndromes with an increased risk of cancer and other pathologies in different organs beside the colon. Furthermore, the psychological implications of having a heritable cancer condition often take an important toll on affected families, with common feelings of guilt for having passed the mutated genes to the offspring.

Thus, to provide the best care to affected families, there is a tremendous need for well-organized and comprehensive cancer genetics services that are capable of responding to the multiple needs of these families so state-of-the-art cancer preventive measures can be carried out and multilevel support can be provided. The mentioned considerations were the guiding force in the creation of the Smilow Cancer Genetics and Prevention Program (SCGPP) at Yale. Thus, we established a comprehensive program that brings together health professionals specializing in different aspects of these patients’ care that ensures their proper attention in a longitudinal fashion, making the program their home for health care. We integrated in the program, among others, physician leaders in gastrointestinal (GI), breast, gynecological, endocrine, and genitourinary high-risk malignancies; genetic counselors; an advanced practice registered nurse specializing in cancer prevention and risk reduction; and a scientific director who leads the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratory at Yale that offers in-house genetic testing, including full exome sequencing. The SCGPP was started in July 2015, and it currently provides more than 250 new consultations per month.

The following are several key elements that I consider important for a cancer genetics program and how they have been addressed at the SCGPP.

Identification through risk stratification

Because the identification of all individuals who can benefit from cancer genetics consultation is complex yet essential, a comprehensive approach with different strategies is often necessary.9 Universal tumor testing is an effective tool, but other complementary approaches such as the use of questionnaires can also contribute to identifying patients in need for cancer genetics assessment. In our program, the pathology department tests for MMR protein expression in all bowel and endometrial tumors. The ones that have loss of expression of an MMR protein are reported to the SCGPP, which contacts the patient’s providers to request a referral. In a relatively short implementation time, this has already resulted in a significant increase in the number of patients referred for cancer genetics consultation and new Lynch syndrome diagnosis. On the other hand, two brief and simplified questionnaires have been developed and distributed in clinics, one for health providers and one administered directly to patients. The questionnaires contain questions related to the patient’s own cancer history, polyp history, cancer screening tests, and family history. The first one assists health care providers in identifying individuals. The second one is completed by patients, collected, and reviewed by a genetic counselor. Suitable patients are invited to a cancer genetics consultation through their primary health care providers. A third questionnaire directed to endoscopy services will be rolled out soon. This collects information on completed endoscopy procedures, polyps and cancers found, and family history.

The program is currently working with information technology to develop a system to pull from the electronic medical record (EMR) relevant information on the patient’s own medical history, family history, and endoscopy findings. A set of criteria has been established so relevant information will generate an alert for prompt referral for the SCGPP.

Because education of health care providers about these conditions is essential to foster collaboration and to help them better understand about cancer risk assessment, genetics, and what the SCGPP can offer to some of their patients, sessions are routinely held with some of them to discuss different aspects on cancer genetics.

In summary, a comprehensive and coordinated approach is key to substantially expand the number of individuals identified and referred for cancer genetics assessment.

Genetic testing

During the last few years we have witnessed changes at different levels around genetic testing that are having a tremendous impact. Some of these changes pose significant new challenges that require rapid adaptation on the providers’ side. Thus, we are quickly moving from single gene testing to panels of genes tested at once. This has resulted in unexpected findings such as mutated genes not initially suspected or variants of unknown significance that often should be interpreted in the context of the personal and family history of cancer because of the lack of definite information on their potential pathogenicity.10 Adding to that, genome-scale tumor sequencing is becoming more common as it increasingly informs on the types of anti-tumor therapies to be selected for a specific patient (precision medicine). This approach is revealing some unexpected information because in some cases it has helped identify significant mutations in the germline.11

Finally, the increasing number of commercial laboratories offering genetic testing has resulted in more competition and lower prices, in some cases to a point that direct-to-consumer charges may be even lower than insurance copayments. This is contributing to a rapid increase in individuals being tested including patients who otherwise would unlikely have been tested in the past because of lack of fulfillment of insurance criteria. The challenge for us is to be ready to help navigate the increasing amount of information obtained as a result of all these changes.

Integration of electronic platforms

In an era of full implementation of EMRs, a cancer genetics program should not simply adapt to the new environment but fully embrace it and explore the possibilities that come with it. Thus, from its inception, the SCGPP has been embracing the electronic platforms to the maximum extent so the clinical operation is streamlined and documentation is well-displayed and accessible in the EMR. The Yale health care system uses EPIC (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as its EMR, and the SCGPP uses Progeny (Progeny Genetics LLC, Delray Beach, FL) to collect data, construct family pedigrees, and build the research registry of the Program. A joint effort by the developers of both systems has resulted in integration at different levels. Thus, after a referral is received, patients are called, registered, and asked several questions including their own cancer and polyp history as well as their family history of cancer. This assists in triaging patients to the most appropriate SCGPP provider: a genetic counselor, a disease physician leader, or a combined visit according to the established internal protocol. In all cases, for new patients with GI cancer syndromes, a combined appointment of a genetic counselor and the GI physician leader is scheduled. At the same time, patients are sent an email with a link to the Progeny online questionnaire that includes personal and family history of cancer as well as extensive clinical information. Once the questionnaire is completed, the program generates a preliminary pedigree that patients can print, and the SCGPP gets a message communicating that the patient has completed this questionnaire. Therefore, when patients are seen on consultation, providers already have the provisional data and pedigree. During the visit, information is verified and edited as needed, and the finalized pedigree goes live through a hyperlink in the EMR. Every revision results in an updated pedigree visible through the mentioned hyperlink. This process saves a considerable amount of time to the providers and increases clinic efficiency.

Informed consent for the research registry is also fully electronic, with signatures recorded in tablets that transmit the signed document to a secure server.

The necessary team approach

Another essential component of a cancer genetics program like this is the integrated and comprehensive approach to patients. Thus, in our Program, the combined appointments for GI patients with the genetic counselor and the physician leader cover all different aspects of care, and a complete plan is suggested and discussed. Once the initial assessment is finalized and genetic testing results (if ordered) are completed, patients are followed prospectively to ensure that prophylactic and cancer prevention measures are undertaken according to the updated standards of care. Complex cases are discussed with the entire team in the weekly case conference that is always followed by a scientific conference with alternating topics such as journal club, practice improvement, ongoing research projects, and extensive case reviews.

Network integration