User login

Transition Readiness Assessment for Sickle Cell Patients: A Quality Improvement Project

From the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

This article is the fourth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to implement an assessment tool to evaluate transition readiness in youth with sickle cell disease (SCD).

- Methods: Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were run to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a provider-based transition readiness assessment.

- Results: Seventy-two adolescents aged 17 years (53% male) were assessed for transition readiness from August 2011 to June 2013. Results indicated that it is feasible for a provider transition readiness assessment (PTRA) tool to be integrated into a transition program. The newly created PTRA tool can inform the level of preparedness of adolescents with SCD during planning for adult transition.

- Conclusion: The PTRA tool may be helpful for planning and preparation of youth with SCD to successfully transition to adult care.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic disorders in the world and is caused by a mutation producing the abnormal sickle hemoglobin. Patients with SCD are living longer and transitioning from pediatric to adult providers. However, the transition years are associated with high mortality [1–4], risk for increased utilization of emergency care, and underutilization of care maintenance visits [5,6]. Successful transition from pediatric care to adult care is critical in ensuring care continuity and optimal health [7]. Barriers to successful transition include lack of preparation for transition [8,9]. To address this limitation, transition programs have been created to help foster transition preparation and readiness.

Often, chronological age determines when SCD programs transfer patients to adult care; however, age is an inadequate measure of readiness. To determine the appropriate time for transition and to individualize the subsequent preparation and planning prior to transfer, an assessment of transition readiness is needed. A number of checklists exist in the unpublished literature (eg, on institution and program websites), and a few empirically tested transition readiness measures have been developed through literature review, semi-structured interviews, and pilot testing in patient samples [10–13]. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) and TRxANSITION scale are non-disease-specific measures that assess self-management and advocacy skills of youth with special health care needs; the TRAQ is self-report whereas the TRxANSITION scale is provider-administered [10,11]. Disease-specific measures have been developed for pediatric kidney transplant recipients [12] and adolescents with cystic fibrosis [13]. Studies using these measures suggest that transition readiness is associated with age, gender, disease type, increased adolescent responsibility/decreased parental involvement, and adherence [10–12].

For patients with SCD, there is no well-validated measure available to assess transition readiness [14]. Telfair and colleagues developed a sickle cell transfer questionnaire that focused on transition concerns and feelings and suggestions for transition intervention programming from the perspective of adolescents, their primary caregivers, and adults with SCD [15]. In addition, McPherson and colleagues examined SCD transition readiness in 4 areas: prior thought about transition, knowledge about steps to transition, interest in learning more about the transition process, and perceived importance of continuing care with a hematologist as an adult provider [8]. They found that adolescents in general were not prepared for transition but that readiness improved with age [8]. Overall, most readiness measures have involved patient self-report or parent proxy report. No current readiness assessment scales incorporate the provider’s assessment, which could help better define the most appropriate next steps in education and preparation for the upcoming transfer to adult care.

The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital SCD Transition to Adult Care program was started in 2007 and is a companion program to the SCD teen clinic, serving 250 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. The transition program curriculum addresses all aspects of the transition process. Based on the curriculum components, St. Jude developed and implemented a transition readiness assessment tool to be completed by providers in the SCD transition program. In this article, we describe our use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to evaluate the utility and impact of the newly created SCD transition readiness assessment tool.

Methods

Transition Program

The transition program is directed by a multidisciplinary team; disciplines represented on the team are medical (hematologist, genetic educator, physician assistant, and nurse coordinators), psychosocial (social workers), emotional/cognitive (psychologists), and academic (academic coordinator). In the program, adolescents with SCD and their families are introduced to the concept of transition to adult care at the age of 12. Every 6 months from 12 to 18 years of age, members of the team address relevant topics with patients to increase patients’ disease knowledge and improve their disease self-management skills. Some of the program components include training in completing a personal health record (PHR), genetic education, academic planning, and independent living skills.

Needs Assessment

Prior to initiation of the project, members of the transition program met monthly to informally discuss the progress of patients who were approaching the age of transition to adult care. We found that adolescents did not appear to be ready or well prepared for transition, including not being aware of the various familial and psychosocial issues that needed to be addressed prior to the transfer to adult care. We realized that these discussions needed to occur earlier to allow more time for preparation and transition planning of the patient, family, and medical team. In addition, members of the team each has differing perspectives and did not have the same information with regard to existing familial and psychosocial issues. The discussions were necessary to ensure all team members had pertinent information to make informed decisions about the patient’s level of transition readiness. Finally, our criteria for readiness were not standardized or quantifiable. As a result, each patient discussion was lengthy, not structured, and not very informative. In 2011, a core group from the transition team attended a Health Resources Services Administration–sponsored Hemoglobinopathies Quality Improvement Workshop to receive training in QI processes. We decided to create a formal, quantitative, individualized assessment of patients’ progress toward transition at age 17.

Readiness Assessment Tool

The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was developed by the pediatric psychologist and pediatric neuropsychologist. Because the psychology service is set up to see patients referred by the medical team and is unable to see all patients coming to hematology clinic, the emotional/cognitive checklist is based on identifying previous utilization of psychological services including psychotherapy and cognitive testing and determining whether initiation of services is warranted. The academic domain checklist was developed by the academic coordinator who serves as a liaison between the medical team and the school system. This checklist assesses whether the adolescent is meeting high school graduation requirements, able to verbalize an educational/job training plan, on track with future planning (eg, completed required testing), knowledgeable about community educational services, and able to self-advocate (eg, apply for SSI benefits).

Items within each domain have equal value (ie, each question on the checklist is worth 1 point) and the sum of points yields the quantifiable assessment of how well patients are performing in each area of their health. Assessment meetings occur monthly when eligible patients are discussed. Domains are evaluated by the health care provider responsible for his/her own domain (eg, social worker completes the psychosocial domain, the academic coordinator completes the academic domain, etc.).

PDSA Methodology

Cycle 1

The objective of the first cycle was to assess feasibility and acceptability of the assessment tool. Patients were assessed during the month of their 17th birthday. Fourteen out of 16 eligible patients (87.5%) were assessed: 1 patient was lost to follow-up, and 1 patient inadvertently was not included in the assessment due to an administrative error. Feedback from the first cycle revealed that some items on the emotional/cognitive domain checklist were not clearly defined, and there was some overlap with the psychosocial domain checklist. Additionally, some items were not readily assessed by psychology based on the structure of psychology services at the institution. Not all patients are seen by psychology; patients are referred to psychology by the team and appointments occur in the psychology clinic and were not well-integrated within the hematology clinic visit.

Cycle 2

The second cycle addressed some of the problems identified during Cycle 1. The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was revised to reflect psychology clinic utilization (psychotherapy and testing) and a section was added where team members could indicate individualized action plans. Seventeen patients out of 18 eligible patients were assessed (94.4%): 1 patient was lost to follow-up. At the conclusion of this cycle, we found that several patients had not completed certain transition program components, such as genetic education or their PHR. Therefore, we decided that we needed to indicate this and create a Plan of Action (POA) to ensure completion of program components. The POA indicated which components were outstanding, when these components would be completed, and when the team would discuss the patient again to track their progress with program components (eg, 6 months later).

Cycle 3

Following a few months using the assessment process, each member of the team provided feedback about their observations from the second cycle. The third cycle of the PDSA addressed some of the barriers identified in Cycle 2 by adding the POA and timeline for reassessment. With this information, the nurse case manager was able to identify and contact families who had significant gaps in the learning curriculum. Additionally, services such as psychological testing were scheduled in a timely manner to address academic problems and to provide rationale for accommodations and academic/vocational services before patients transferred care to the adult provider. With the number of assessed patients increasing, it was determined that a reliable tracking system to monitor progress was essential. Thus, a transition database was created to document the domain scores, individualized plan of action, and other components of the transition program, such as medical literacy quiz scores, completion of pre-transfer visits to adult providers, and completion of the PHR. During this cycle, 20 patients were assessed out of a total of 22 eligible patients (90.9%); 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

Cycle 4

This cycle is currently underway and comprises monthly assessments of eligible 17-year-old patients with SCD. From January 2013 to May 2013 we have assessed 100% of the eligible patients (21/21). All information obtained through the assessment tool is added to the transition database. Future adjustments and modifications are planned for this tool as we continue to evaluate its impact and value.

Discussion

The transition readiness assessment tool was developed to evaluate adolescent patients with SCD aged 17 years regarding their progress in the transition program and level of transition readiness. Most transition readiness measures available in the literature consider the patient and parent perspective but do not include the health care provider perspective or determine if the patient received the information necessary for successful transition. Our readiness assessment tool has been helpful in providing a structured and quantifiable means to identify at-risk patients and families prior to the transfer of care and revealing important gaps in transition planning. It also provides information in a timely manner about points of intervention to ensure patients receive adequate preparation and services (eg, psychological/neuropsychological testing). Additionally, monthly meetings are held during which the tool is scored and discussed, providing an opportunity for members of the transition team to examine patients’ progress toward transition readiness. Finally, completing an individualized tool in a multidisciplinary setting has the added benefit of encouraging increased staff collaboration and creating a venue for ongoing re-evaluation of the QI process.

We achieved our objective of completing the assessment tool for 80% of eligible patients throughout the cycles. The majority of our nonassessed patients was lost to follow-up and had not had a clinic visit in 2 to 3 years. Implementing the tool has provided us with an additional mechanism to verify transition eligibility and has afforded the transition program a systematic way to screen and track patients who are approaching the age of transition and who may have not been seen for an extended period of time. As with any large program following children with special health care and complex needs, the large volume of patients and their complexity may pose a challenge to the program, therefore having an additional tracking system in place may help mitigate possible losses to follow-up. In fact, since the implementation of tool, our team has been able to contact families and in some cases have reinstated services. As a by-product of tool implementation, we have implemented new policies to prevent extended losses to follow-up and patient attrition.

Limitations

A limitation of the assessment tool is that it does not incorporate the perspectives of the other stakeholders (adolescents, parents, adult providers). Further, some of the items in our tool are measuring utilization of services and not specifically transition readiness. As with most transition readiness measures, our provider tool does not have established reliability and validity [14]. We plan to test for reliability and validity once enough data and patient outcomes have been collected. Additionally, because of the small number of patients who have transferred to adult care since implementation of the tool, we did not examine the association between readiness scores and clinical outcomes, such as fulfillment of first adult provider visit and hospital utilization following transition to adult care. As we continue to assess adolescent patients and track their progress following transition, we will be able to examine these associations with a larger group.

Future Plans

Since the implementation of the tool in our program, we have realized that we may need to start assessing patients at an earlier age and perhaps multiple times throughout adolescence. Some of our patients have guardianship and conservatorship issues and require more time to discuss options with the family and put in place the appropriate support and assistance prior to the transfer of care. Further, patients that have low compliance to clinic appointments are not receiving all elements of the transition program curriculum and in turn have fewer opportunities to prepare for transition. To address some of our current limitations, we plan to incorporate a patient and parent readiness assessment and examine the associations between the provider assessment and patient information such as medical literacy quizzes, clinic compliance, and fulfillment of the first adult provider visit. Assessment from all 3 perspectives (patient, parent, and provider) will offer a 360-degree view of transition readiness perception which should improve our ability to identify at-risk families and tailor transition planning to address barriers to care. In addition, our future plans include development of a mechanism to inform patients and families about the domain scores and action plans following the transition readiness meetings and include scores into the electronic medical records. Finally, the readiness assessment tool has revealed some gaps in our transition educational curriculum. Most of our transition learning involves providing and evaluating information provided, but we are not systematically assessing actual acquired transition skills. We are in the process of developing and implementing skill-based learning for activities such as calling to make or reschedule an appointment with an adult provider, arranging transportation, etc.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the provider transition readiness assessment has been a helpful tool to monitor progress of adolescents with SCD towards readiness for transition. The QI methodology and PDSA cycle approach has not only allowed for testing, development, and implementation of the tool, but is also allowing ongoing systematic refinement of our instrument. This approach highlighted the psychosocial challenges of our families as they move toward the transfer of care, in addition to the need for more individualized planning. The next important step is to evaluate the validity and reliability of the measure so we can better evaluate the impact of transition programming on the transfer from pediatric to adult care. We found the PDSA cycle approach to be a framework that can efficiently and systematically improve the quality of care of transitioning patients with SCD and their families.

Corresponding author: Jerlym Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hosp., 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–S521.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood C, Jr. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

5. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

6. Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol 2011;86:863–5.

7. Jordan L, Swerdlow P, Coates TD. Systematic review of transition from adolescent to adult care in patients with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:165–9.

8. McPherson M, Thaniel L, Minniti CP. Transition of patients with sickle cell disease from pediatric to adult care: assessing patient readiness. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;52:838–41.

9. Lebensburger JD, Bemrich-Stolz CJ, Howard TH. Barriers in transition from pediatrics to adult medicine in sickle cell anemia. J Blood Med 2012;3:105–12.

10. Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ--Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:160–71.

11. Ferris ME, Harward DH, Bickford K, et al. A clinical tool to measure the components of health-care transition from pediatric care to adult care: the UNC TR(x)ANSITION scale. Ren Fail 2012;34:744–53.

12. Gilleland J, Amaral S, Mee L, Blount R. Getting ready to leave: transition readiness in adolescent kidney transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:85–96.

13. Cappelli M, MacDonald NE, McGrath PJ. Assessment of readiness to transfer to adult care for adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Child Health Care 1989;18:218–24.

14. Stinson J, Kohut SA, Spiegel L, et al. A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2013:1–16.

15. Telfair J, Myers J, Drezner S. Transfer as a component of the transition of adolescents with sickle cell disease to adult care: adolescent, adult, and parent perspectives. J Adolesc Health 1994;15:558–65.

16. Walley P, Gowland B. Completing the circle: from PD to PDSA. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2004;17:349–58.

From the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

This article is the fourth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to implement an assessment tool to evaluate transition readiness in youth with sickle cell disease (SCD).

- Methods: Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were run to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a provider-based transition readiness assessment.

- Results: Seventy-two adolescents aged 17 years (53% male) were assessed for transition readiness from August 2011 to June 2013. Results indicated that it is feasible for a provider transition readiness assessment (PTRA) tool to be integrated into a transition program. The newly created PTRA tool can inform the level of preparedness of adolescents with SCD during planning for adult transition.

- Conclusion: The PTRA tool may be helpful for planning and preparation of youth with SCD to successfully transition to adult care.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic disorders in the world and is caused by a mutation producing the abnormal sickle hemoglobin. Patients with SCD are living longer and transitioning from pediatric to adult providers. However, the transition years are associated with high mortality [1–4], risk for increased utilization of emergency care, and underutilization of care maintenance visits [5,6]. Successful transition from pediatric care to adult care is critical in ensuring care continuity and optimal health [7]. Barriers to successful transition include lack of preparation for transition [8,9]. To address this limitation, transition programs have been created to help foster transition preparation and readiness.

Often, chronological age determines when SCD programs transfer patients to adult care; however, age is an inadequate measure of readiness. To determine the appropriate time for transition and to individualize the subsequent preparation and planning prior to transfer, an assessment of transition readiness is needed. A number of checklists exist in the unpublished literature (eg, on institution and program websites), and a few empirically tested transition readiness measures have been developed through literature review, semi-structured interviews, and pilot testing in patient samples [10–13]. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) and TRxANSITION scale are non-disease-specific measures that assess self-management and advocacy skills of youth with special health care needs; the TRAQ is self-report whereas the TRxANSITION scale is provider-administered [10,11]. Disease-specific measures have been developed for pediatric kidney transplant recipients [12] and adolescents with cystic fibrosis [13]. Studies using these measures suggest that transition readiness is associated with age, gender, disease type, increased adolescent responsibility/decreased parental involvement, and adherence [10–12].

For patients with SCD, there is no well-validated measure available to assess transition readiness [14]. Telfair and colleagues developed a sickle cell transfer questionnaire that focused on transition concerns and feelings and suggestions for transition intervention programming from the perspective of adolescents, their primary caregivers, and adults with SCD [15]. In addition, McPherson and colleagues examined SCD transition readiness in 4 areas: prior thought about transition, knowledge about steps to transition, interest in learning more about the transition process, and perceived importance of continuing care with a hematologist as an adult provider [8]. They found that adolescents in general were not prepared for transition but that readiness improved with age [8]. Overall, most readiness measures have involved patient self-report or parent proxy report. No current readiness assessment scales incorporate the provider’s assessment, which could help better define the most appropriate next steps in education and preparation for the upcoming transfer to adult care.

The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital SCD Transition to Adult Care program was started in 2007 and is a companion program to the SCD teen clinic, serving 250 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. The transition program curriculum addresses all aspects of the transition process. Based on the curriculum components, St. Jude developed and implemented a transition readiness assessment tool to be completed by providers in the SCD transition program. In this article, we describe our use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to evaluate the utility and impact of the newly created SCD transition readiness assessment tool.

Methods

Transition Program

The transition program is directed by a multidisciplinary team; disciplines represented on the team are medical (hematologist, genetic educator, physician assistant, and nurse coordinators), psychosocial (social workers), emotional/cognitive (psychologists), and academic (academic coordinator). In the program, adolescents with SCD and their families are introduced to the concept of transition to adult care at the age of 12. Every 6 months from 12 to 18 years of age, members of the team address relevant topics with patients to increase patients’ disease knowledge and improve their disease self-management skills. Some of the program components include training in completing a personal health record (PHR), genetic education, academic planning, and independent living skills.

Needs Assessment

Prior to initiation of the project, members of the transition program met monthly to informally discuss the progress of patients who were approaching the age of transition to adult care. We found that adolescents did not appear to be ready or well prepared for transition, including not being aware of the various familial and psychosocial issues that needed to be addressed prior to the transfer to adult care. We realized that these discussions needed to occur earlier to allow more time for preparation and transition planning of the patient, family, and medical team. In addition, members of the team each has differing perspectives and did not have the same information with regard to existing familial and psychosocial issues. The discussions were necessary to ensure all team members had pertinent information to make informed decisions about the patient’s level of transition readiness. Finally, our criteria for readiness were not standardized or quantifiable. As a result, each patient discussion was lengthy, not structured, and not very informative. In 2011, a core group from the transition team attended a Health Resources Services Administration–sponsored Hemoglobinopathies Quality Improvement Workshop to receive training in QI processes. We decided to create a formal, quantitative, individualized assessment of patients’ progress toward transition at age 17.

Readiness Assessment Tool

The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was developed by the pediatric psychologist and pediatric neuropsychologist. Because the psychology service is set up to see patients referred by the medical team and is unable to see all patients coming to hematology clinic, the emotional/cognitive checklist is based on identifying previous utilization of psychological services including psychotherapy and cognitive testing and determining whether initiation of services is warranted. The academic domain checklist was developed by the academic coordinator who serves as a liaison between the medical team and the school system. This checklist assesses whether the adolescent is meeting high school graduation requirements, able to verbalize an educational/job training plan, on track with future planning (eg, completed required testing), knowledgeable about community educational services, and able to self-advocate (eg, apply for SSI benefits).

Items within each domain have equal value (ie, each question on the checklist is worth 1 point) and the sum of points yields the quantifiable assessment of how well patients are performing in each area of their health. Assessment meetings occur monthly when eligible patients are discussed. Domains are evaluated by the health care provider responsible for his/her own domain (eg, social worker completes the psychosocial domain, the academic coordinator completes the academic domain, etc.).

PDSA Methodology

Cycle 1

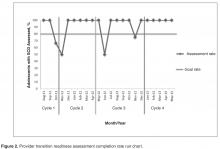

The objective of the first cycle was to assess feasibility and acceptability of the assessment tool. Patients were assessed during the month of their 17th birthday. Fourteen out of 16 eligible patients (87.5%) were assessed: 1 patient was lost to follow-up, and 1 patient inadvertently was not included in the assessment due to an administrative error. Feedback from the first cycle revealed that some items on the emotional/cognitive domain checklist were not clearly defined, and there was some overlap with the psychosocial domain checklist. Additionally, some items were not readily assessed by psychology based on the structure of psychology services at the institution. Not all patients are seen by psychology; patients are referred to psychology by the team and appointments occur in the psychology clinic and were not well-integrated within the hematology clinic visit.

Cycle 2

The second cycle addressed some of the problems identified during Cycle 1. The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was revised to reflect psychology clinic utilization (psychotherapy and testing) and a section was added where team members could indicate individualized action plans. Seventeen patients out of 18 eligible patients were assessed (94.4%): 1 patient was lost to follow-up. At the conclusion of this cycle, we found that several patients had not completed certain transition program components, such as genetic education or their PHR. Therefore, we decided that we needed to indicate this and create a Plan of Action (POA) to ensure completion of program components. The POA indicated which components were outstanding, when these components would be completed, and when the team would discuss the patient again to track their progress with program components (eg, 6 months later).

Cycle 3

Following a few months using the assessment process, each member of the team provided feedback about their observations from the second cycle. The third cycle of the PDSA addressed some of the barriers identified in Cycle 2 by adding the POA and timeline for reassessment. With this information, the nurse case manager was able to identify and contact families who had significant gaps in the learning curriculum. Additionally, services such as psychological testing were scheduled in a timely manner to address academic problems and to provide rationale for accommodations and academic/vocational services before patients transferred care to the adult provider. With the number of assessed patients increasing, it was determined that a reliable tracking system to monitor progress was essential. Thus, a transition database was created to document the domain scores, individualized plan of action, and other components of the transition program, such as medical literacy quiz scores, completion of pre-transfer visits to adult providers, and completion of the PHR. During this cycle, 20 patients were assessed out of a total of 22 eligible patients (90.9%); 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

Cycle 4

This cycle is currently underway and comprises monthly assessments of eligible 17-year-old patients with SCD. From January 2013 to May 2013 we have assessed 100% of the eligible patients (21/21). All information obtained through the assessment tool is added to the transition database. Future adjustments and modifications are planned for this tool as we continue to evaluate its impact and value.

Discussion

The transition readiness assessment tool was developed to evaluate adolescent patients with SCD aged 17 years regarding their progress in the transition program and level of transition readiness. Most transition readiness measures available in the literature consider the patient and parent perspective but do not include the health care provider perspective or determine if the patient received the information necessary for successful transition. Our readiness assessment tool has been helpful in providing a structured and quantifiable means to identify at-risk patients and families prior to the transfer of care and revealing important gaps in transition planning. It also provides information in a timely manner about points of intervention to ensure patients receive adequate preparation and services (eg, psychological/neuropsychological testing). Additionally, monthly meetings are held during which the tool is scored and discussed, providing an opportunity for members of the transition team to examine patients’ progress toward transition readiness. Finally, completing an individualized tool in a multidisciplinary setting has the added benefit of encouraging increased staff collaboration and creating a venue for ongoing re-evaluation of the QI process.

We achieved our objective of completing the assessment tool for 80% of eligible patients throughout the cycles. The majority of our nonassessed patients was lost to follow-up and had not had a clinic visit in 2 to 3 years. Implementing the tool has provided us with an additional mechanism to verify transition eligibility and has afforded the transition program a systematic way to screen and track patients who are approaching the age of transition and who may have not been seen for an extended period of time. As with any large program following children with special health care and complex needs, the large volume of patients and their complexity may pose a challenge to the program, therefore having an additional tracking system in place may help mitigate possible losses to follow-up. In fact, since the implementation of tool, our team has been able to contact families and in some cases have reinstated services. As a by-product of tool implementation, we have implemented new policies to prevent extended losses to follow-up and patient attrition.

Limitations

A limitation of the assessment tool is that it does not incorporate the perspectives of the other stakeholders (adolescents, parents, adult providers). Further, some of the items in our tool are measuring utilization of services and not specifically transition readiness. As with most transition readiness measures, our provider tool does not have established reliability and validity [14]. We plan to test for reliability and validity once enough data and patient outcomes have been collected. Additionally, because of the small number of patients who have transferred to adult care since implementation of the tool, we did not examine the association between readiness scores and clinical outcomes, such as fulfillment of first adult provider visit and hospital utilization following transition to adult care. As we continue to assess adolescent patients and track their progress following transition, we will be able to examine these associations with a larger group.

Future Plans

Since the implementation of the tool in our program, we have realized that we may need to start assessing patients at an earlier age and perhaps multiple times throughout adolescence. Some of our patients have guardianship and conservatorship issues and require more time to discuss options with the family and put in place the appropriate support and assistance prior to the transfer of care. Further, patients that have low compliance to clinic appointments are not receiving all elements of the transition program curriculum and in turn have fewer opportunities to prepare for transition. To address some of our current limitations, we plan to incorporate a patient and parent readiness assessment and examine the associations between the provider assessment and patient information such as medical literacy quizzes, clinic compliance, and fulfillment of the first adult provider visit. Assessment from all 3 perspectives (patient, parent, and provider) will offer a 360-degree view of transition readiness perception which should improve our ability to identify at-risk families and tailor transition planning to address barriers to care. In addition, our future plans include development of a mechanism to inform patients and families about the domain scores and action plans following the transition readiness meetings and include scores into the electronic medical records. Finally, the readiness assessment tool has revealed some gaps in our transition educational curriculum. Most of our transition learning involves providing and evaluating information provided, but we are not systematically assessing actual acquired transition skills. We are in the process of developing and implementing skill-based learning for activities such as calling to make or reschedule an appointment with an adult provider, arranging transportation, etc.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the provider transition readiness assessment has been a helpful tool to monitor progress of adolescents with SCD towards readiness for transition. The QI methodology and PDSA cycle approach has not only allowed for testing, development, and implementation of the tool, but is also allowing ongoing systematic refinement of our instrument. This approach highlighted the psychosocial challenges of our families as they move toward the transfer of care, in addition to the need for more individualized planning. The next important step is to evaluate the validity and reliability of the measure so we can better evaluate the impact of transition programming on the transfer from pediatric to adult care. We found the PDSA cycle approach to be a framework that can efficiently and systematically improve the quality of care of transitioning patients with SCD and their families.

Corresponding author: Jerlym Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hosp., 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

This article is the fourth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to implement an assessment tool to evaluate transition readiness in youth with sickle cell disease (SCD).

- Methods: Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were run to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a provider-based transition readiness assessment.

- Results: Seventy-two adolescents aged 17 years (53% male) were assessed for transition readiness from August 2011 to June 2013. Results indicated that it is feasible for a provider transition readiness assessment (PTRA) tool to be integrated into a transition program. The newly created PTRA tool can inform the level of preparedness of adolescents with SCD during planning for adult transition.

- Conclusion: The PTRA tool may be helpful for planning and preparation of youth with SCD to successfully transition to adult care.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic disorders in the world and is caused by a mutation producing the abnormal sickle hemoglobin. Patients with SCD are living longer and transitioning from pediatric to adult providers. However, the transition years are associated with high mortality [1–4], risk for increased utilization of emergency care, and underutilization of care maintenance visits [5,6]. Successful transition from pediatric care to adult care is critical in ensuring care continuity and optimal health [7]. Barriers to successful transition include lack of preparation for transition [8,9]. To address this limitation, transition programs have been created to help foster transition preparation and readiness.

Often, chronological age determines when SCD programs transfer patients to adult care; however, age is an inadequate measure of readiness. To determine the appropriate time for transition and to individualize the subsequent preparation and planning prior to transfer, an assessment of transition readiness is needed. A number of checklists exist in the unpublished literature (eg, on institution and program websites), and a few empirically tested transition readiness measures have been developed through literature review, semi-structured interviews, and pilot testing in patient samples [10–13]. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) and TRxANSITION scale are non-disease-specific measures that assess self-management and advocacy skills of youth with special health care needs; the TRAQ is self-report whereas the TRxANSITION scale is provider-administered [10,11]. Disease-specific measures have been developed for pediatric kidney transplant recipients [12] and adolescents with cystic fibrosis [13]. Studies using these measures suggest that transition readiness is associated with age, gender, disease type, increased adolescent responsibility/decreased parental involvement, and adherence [10–12].

For patients with SCD, there is no well-validated measure available to assess transition readiness [14]. Telfair and colleagues developed a sickle cell transfer questionnaire that focused on transition concerns and feelings and suggestions for transition intervention programming from the perspective of adolescents, their primary caregivers, and adults with SCD [15]. In addition, McPherson and colleagues examined SCD transition readiness in 4 areas: prior thought about transition, knowledge about steps to transition, interest in learning more about the transition process, and perceived importance of continuing care with a hematologist as an adult provider [8]. They found that adolescents in general were not prepared for transition but that readiness improved with age [8]. Overall, most readiness measures have involved patient self-report or parent proxy report. No current readiness assessment scales incorporate the provider’s assessment, which could help better define the most appropriate next steps in education and preparation for the upcoming transfer to adult care.

The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital SCD Transition to Adult Care program was started in 2007 and is a companion program to the SCD teen clinic, serving 250 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. The transition program curriculum addresses all aspects of the transition process. Based on the curriculum components, St. Jude developed and implemented a transition readiness assessment tool to be completed by providers in the SCD transition program. In this article, we describe our use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to evaluate the utility and impact of the newly created SCD transition readiness assessment tool.

Methods

Transition Program

The transition program is directed by a multidisciplinary team; disciplines represented on the team are medical (hematologist, genetic educator, physician assistant, and nurse coordinators), psychosocial (social workers), emotional/cognitive (psychologists), and academic (academic coordinator). In the program, adolescents with SCD and their families are introduced to the concept of transition to adult care at the age of 12. Every 6 months from 12 to 18 years of age, members of the team address relevant topics with patients to increase patients’ disease knowledge and improve their disease self-management skills. Some of the program components include training in completing a personal health record (PHR), genetic education, academic planning, and independent living skills.

Needs Assessment

Prior to initiation of the project, members of the transition program met monthly to informally discuss the progress of patients who were approaching the age of transition to adult care. We found that adolescents did not appear to be ready or well prepared for transition, including not being aware of the various familial and psychosocial issues that needed to be addressed prior to the transfer to adult care. We realized that these discussions needed to occur earlier to allow more time for preparation and transition planning of the patient, family, and medical team. In addition, members of the team each has differing perspectives and did not have the same information with regard to existing familial and psychosocial issues. The discussions were necessary to ensure all team members had pertinent information to make informed decisions about the patient’s level of transition readiness. Finally, our criteria for readiness were not standardized or quantifiable. As a result, each patient discussion was lengthy, not structured, and not very informative. In 2011, a core group from the transition team attended a Health Resources Services Administration–sponsored Hemoglobinopathies Quality Improvement Workshop to receive training in QI processes. We decided to create a formal, quantitative, individualized assessment of patients’ progress toward transition at age 17.

Readiness Assessment Tool

The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was developed by the pediatric psychologist and pediatric neuropsychologist. Because the psychology service is set up to see patients referred by the medical team and is unable to see all patients coming to hematology clinic, the emotional/cognitive checklist is based on identifying previous utilization of psychological services including psychotherapy and cognitive testing and determining whether initiation of services is warranted. The academic domain checklist was developed by the academic coordinator who serves as a liaison between the medical team and the school system. This checklist assesses whether the adolescent is meeting high school graduation requirements, able to verbalize an educational/job training plan, on track with future planning (eg, completed required testing), knowledgeable about community educational services, and able to self-advocate (eg, apply for SSI benefits).

Items within each domain have equal value (ie, each question on the checklist is worth 1 point) and the sum of points yields the quantifiable assessment of how well patients are performing in each area of their health. Assessment meetings occur monthly when eligible patients are discussed. Domains are evaluated by the health care provider responsible for his/her own domain (eg, social worker completes the psychosocial domain, the academic coordinator completes the academic domain, etc.).

PDSA Methodology

Cycle 1

The objective of the first cycle was to assess feasibility and acceptability of the assessment tool. Patients were assessed during the month of their 17th birthday. Fourteen out of 16 eligible patients (87.5%) were assessed: 1 patient was lost to follow-up, and 1 patient inadvertently was not included in the assessment due to an administrative error. Feedback from the first cycle revealed that some items on the emotional/cognitive domain checklist were not clearly defined, and there was some overlap with the psychosocial domain checklist. Additionally, some items were not readily assessed by psychology based on the structure of psychology services at the institution. Not all patients are seen by psychology; patients are referred to psychology by the team and appointments occur in the psychology clinic and were not well-integrated within the hematology clinic visit.

Cycle 2

The second cycle addressed some of the problems identified during Cycle 1. The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was revised to reflect psychology clinic utilization (psychotherapy and testing) and a section was added where team members could indicate individualized action plans. Seventeen patients out of 18 eligible patients were assessed (94.4%): 1 patient was lost to follow-up. At the conclusion of this cycle, we found that several patients had not completed certain transition program components, such as genetic education or their PHR. Therefore, we decided that we needed to indicate this and create a Plan of Action (POA) to ensure completion of program components. The POA indicated which components were outstanding, when these components would be completed, and when the team would discuss the patient again to track their progress with program components (eg, 6 months later).

Cycle 3

Following a few months using the assessment process, each member of the team provided feedback about their observations from the second cycle. The third cycle of the PDSA addressed some of the barriers identified in Cycle 2 by adding the POA and timeline for reassessment. With this information, the nurse case manager was able to identify and contact families who had significant gaps in the learning curriculum. Additionally, services such as psychological testing were scheduled in a timely manner to address academic problems and to provide rationale for accommodations and academic/vocational services before patients transferred care to the adult provider. With the number of assessed patients increasing, it was determined that a reliable tracking system to monitor progress was essential. Thus, a transition database was created to document the domain scores, individualized plan of action, and other components of the transition program, such as medical literacy quiz scores, completion of pre-transfer visits to adult providers, and completion of the PHR. During this cycle, 20 patients were assessed out of a total of 22 eligible patients (90.9%); 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

Cycle 4

This cycle is currently underway and comprises monthly assessments of eligible 17-year-old patients with SCD. From January 2013 to May 2013 we have assessed 100% of the eligible patients (21/21). All information obtained through the assessment tool is added to the transition database. Future adjustments and modifications are planned for this tool as we continue to evaluate its impact and value.

Discussion

The transition readiness assessment tool was developed to evaluate adolescent patients with SCD aged 17 years regarding their progress in the transition program and level of transition readiness. Most transition readiness measures available in the literature consider the patient and parent perspective but do not include the health care provider perspective or determine if the patient received the information necessary for successful transition. Our readiness assessment tool has been helpful in providing a structured and quantifiable means to identify at-risk patients and families prior to the transfer of care and revealing important gaps in transition planning. It also provides information in a timely manner about points of intervention to ensure patients receive adequate preparation and services (eg, psychological/neuropsychological testing). Additionally, monthly meetings are held during which the tool is scored and discussed, providing an opportunity for members of the transition team to examine patients’ progress toward transition readiness. Finally, completing an individualized tool in a multidisciplinary setting has the added benefit of encouraging increased staff collaboration and creating a venue for ongoing re-evaluation of the QI process.

We achieved our objective of completing the assessment tool for 80% of eligible patients throughout the cycles. The majority of our nonassessed patients was lost to follow-up and had not had a clinic visit in 2 to 3 years. Implementing the tool has provided us with an additional mechanism to verify transition eligibility and has afforded the transition program a systematic way to screen and track patients who are approaching the age of transition and who may have not been seen for an extended period of time. As with any large program following children with special health care and complex needs, the large volume of patients and their complexity may pose a challenge to the program, therefore having an additional tracking system in place may help mitigate possible losses to follow-up. In fact, since the implementation of tool, our team has been able to contact families and in some cases have reinstated services. As a by-product of tool implementation, we have implemented new policies to prevent extended losses to follow-up and patient attrition.

Limitations

A limitation of the assessment tool is that it does not incorporate the perspectives of the other stakeholders (adolescents, parents, adult providers). Further, some of the items in our tool are measuring utilization of services and not specifically transition readiness. As with most transition readiness measures, our provider tool does not have established reliability and validity [14]. We plan to test for reliability and validity once enough data and patient outcomes have been collected. Additionally, because of the small number of patients who have transferred to adult care since implementation of the tool, we did not examine the association between readiness scores and clinical outcomes, such as fulfillment of first adult provider visit and hospital utilization following transition to adult care. As we continue to assess adolescent patients and track their progress following transition, we will be able to examine these associations with a larger group.

Future Plans

Since the implementation of the tool in our program, we have realized that we may need to start assessing patients at an earlier age and perhaps multiple times throughout adolescence. Some of our patients have guardianship and conservatorship issues and require more time to discuss options with the family and put in place the appropriate support and assistance prior to the transfer of care. Further, patients that have low compliance to clinic appointments are not receiving all elements of the transition program curriculum and in turn have fewer opportunities to prepare for transition. To address some of our current limitations, we plan to incorporate a patient and parent readiness assessment and examine the associations between the provider assessment and patient information such as medical literacy quizzes, clinic compliance, and fulfillment of the first adult provider visit. Assessment from all 3 perspectives (patient, parent, and provider) will offer a 360-degree view of transition readiness perception which should improve our ability to identify at-risk families and tailor transition planning to address barriers to care. In addition, our future plans include development of a mechanism to inform patients and families about the domain scores and action plans following the transition readiness meetings and include scores into the electronic medical records. Finally, the readiness assessment tool has revealed some gaps in our transition educational curriculum. Most of our transition learning involves providing and evaluating information provided, but we are not systematically assessing actual acquired transition skills. We are in the process of developing and implementing skill-based learning for activities such as calling to make or reschedule an appointment with an adult provider, arranging transportation, etc.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the provider transition readiness assessment has been a helpful tool to monitor progress of adolescents with SCD towards readiness for transition. The QI methodology and PDSA cycle approach has not only allowed for testing, development, and implementation of the tool, but is also allowing ongoing systematic refinement of our instrument. This approach highlighted the psychosocial challenges of our families as they move toward the transfer of care, in addition to the need for more individualized planning. The next important step is to evaluate the validity and reliability of the measure so we can better evaluate the impact of transition programming on the transfer from pediatric to adult care. We found the PDSA cycle approach to be a framework that can efficiently and systematically improve the quality of care of transitioning patients with SCD and their families.

Corresponding author: Jerlym Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hosp., 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–S521.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood C, Jr. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

5. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

6. Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol 2011;86:863–5.

7. Jordan L, Swerdlow P, Coates TD. Systematic review of transition from adolescent to adult care in patients with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:165–9.

8. McPherson M, Thaniel L, Minniti CP. Transition of patients with sickle cell disease from pediatric to adult care: assessing patient readiness. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;52:838–41.

9. Lebensburger JD, Bemrich-Stolz CJ, Howard TH. Barriers in transition from pediatrics to adult medicine in sickle cell anemia. J Blood Med 2012;3:105–12.

10. Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ--Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:160–71.

11. Ferris ME, Harward DH, Bickford K, et al. A clinical tool to measure the components of health-care transition from pediatric care to adult care: the UNC TR(x)ANSITION scale. Ren Fail 2012;34:744–53.

12. Gilleland J, Amaral S, Mee L, Blount R. Getting ready to leave: transition readiness in adolescent kidney transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:85–96.

13. Cappelli M, MacDonald NE, McGrath PJ. Assessment of readiness to transfer to adult care for adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Child Health Care 1989;18:218–24.

14. Stinson J, Kohut SA, Spiegel L, et al. A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2013:1–16.

15. Telfair J, Myers J, Drezner S. Transfer as a component of the transition of adolescents with sickle cell disease to adult care: adolescent, adult, and parent perspectives. J Adolesc Health 1994;15:558–65.

16. Walley P, Gowland B. Completing the circle: from PD to PDSA. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2004;17:349–58.

1. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–S521.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood C, Jr. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

5. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

6. Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol 2011;86:863–5.

7. Jordan L, Swerdlow P, Coates TD. Systematic review of transition from adolescent to adult care in patients with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:165–9.

8. McPherson M, Thaniel L, Minniti CP. Transition of patients with sickle cell disease from pediatric to adult care: assessing patient readiness. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;52:838–41.

9. Lebensburger JD, Bemrich-Stolz CJ, Howard TH. Barriers in transition from pediatrics to adult medicine in sickle cell anemia. J Blood Med 2012;3:105–12.

10. Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ--Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:160–71.

11. Ferris ME, Harward DH, Bickford K, et al. A clinical tool to measure the components of health-care transition from pediatric care to adult care: the UNC TR(x)ANSITION scale. Ren Fail 2012;34:744–53.

12. Gilleland J, Amaral S, Mee L, Blount R. Getting ready to leave: transition readiness in adolescent kidney transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:85–96.

13. Cappelli M, MacDonald NE, McGrath PJ. Assessment of readiness to transfer to adult care for adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Child Health Care 1989;18:218–24.

14. Stinson J, Kohut SA, Spiegel L, et al. A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2013:1–16.

15. Telfair J, Myers J, Drezner S. Transfer as a component of the transition of adolescents with sickle cell disease to adult care: adolescent, adult, and parent perspectives. J Adolesc Health 1994;15:558–65.

16. Walley P, Gowland B. Completing the circle: from PD to PDSA. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2004;17:349–58.

Using Quality Improvement Methods to Implement an Individualized Home Pain Management Plan for Children with Sickle Cell Disease

From the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH.

This article is the third in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

ABSTRACT

• Objective: To develop and implement individualized home pain management plans that included pharmacologic as well as nonpharmacologic strategies for children with sickle cell disease (SCD).

• Methods: A multidisciplinary quality improvement team developed a questionnaire to assess the frequency, location, and severity of a patient’s pain during a routine comprehensive visit in order to help the patient and family develop an effective home pain management plan. Using plan-do-study-act cycles, the team was able to build this process into the daily workflow for all SCD patients age 5 years to 21 years of age. Patients with comprehensive visits scheduled from January 2012 to May 2013 were included (n = 188) in the intervention.

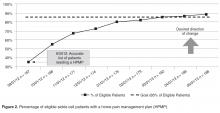

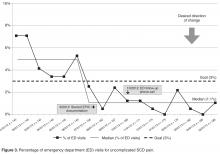

• Results: By May of 2013, 88% of eligible patients had an individualized home plan in place. There was a concomitant reduction in the percentage of SCD patients seen in the ED for uncomplicated SCD pain (6.9% vs. 1.1%).

• Conclusions: Using quality improvement methods, an individualized home pain management intervention was incorporated successfully into the daily workflow of a busy outpatient SCD clinic. This intervention has the potential to improve patient outcomes by decreasing avoidable ED visits as well as reducing overall health care costs.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic disorders in the United States, affecting approximately 1 in 500 African-American infants each year [1]. The genetic mutation that causes SCD results in the production of an abnormal hemoglobin molecule (HbS) in the red blood cells (RBC). Under low oxygen conditions, the HbS polymerizes and causes the RBCs to elongate into a sickle form (crescent shape) and decreases the life span of the RBC. Additionally, RBCs with HbS are more “sticky,” adhering to vessel walls and limiting blood flow and oxygen delivery to many tissues and organs in the body. The resultant tissue ischemia causes progressive organ injury as well as episodes of pain (vaso-occlusive crisis).

Recurrent pain episodes are the hallmark of this disease, accounting for the majority of emergency department (ED) visits as well as hospitalizations. High-quality outpatient care can reduce acute care and ED visits as well as hospitalization rates in patients with SCD [2]. Additionally, ensuring that patients have a home pain management plan and understand how to assess and reassess their pain may improve outcomes [3]. Data from our population of children with SCD indicate that 40% to 50% of ED visits in 2011 were for uncomplicated pain episodes (no concomitant medical issues such as fever, increased respiratory rate, wheezing, worsening pallor). If these pain episodes had been effectively managed at home, the ED visits might have been avoided.

In an effort to reduce these potentially preventable ED visits and subsequent hospitalizations, the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center assembled a quality improvement (QI) team to partner with patients and their families to develop individualized home pain management plans (HPMP) that incorporated both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic pain management strategies. We also sought to identify and remove barriers to the successful use of a home pain management plan, such as not having enough analgesics at home or not allowing enough time for analgesics to work before presenting to the ED. We documented the plan in a standard location and format in the electronic medical record (EMR), making it available to all medical center providers. This paper describes the development, refinement, and testing of an individualized HPMP intervention and related outcomes.

METHODS

Setting

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center is a nonprofit pediatric medical center with 587 inpatient beds in Ohio providing acute and chronic care for children in Southern Ohio, Northern Kentucky, and Southeastern Indiana. The center’s Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center provides comprehensive care to approximately 280 children with SCD in the region from birth to 21 years of age. The medical center is the only major pediatric inpatient facility in the tri-state area. Greater than 75% of the SCD patients at our center live within a 15-mile radius, therefore, essentially all ED visits and hospitalizations for our patients occur at our center.

Participants

Improvement Team

The core QI team consisted of multidisciplinary health care providers with experience caring for patients with SCD, including 3 SCD nurse care managers, 2 physicians, 2 PhD psychologists, 4 nurse practitioners, a QI consultant, and a data analyst. Additional support and suggestions were received from other SCD team members (eg, social workers, school interventionists). The core QI multidisciplinary team met weekly to design and test the intervention and implementation process.

Intervention

The intervention consisted of the following elements: (1) pre-visit review to identify eligible patients needing a new or updated home pain management plan; (2) family completion of a pain assessment tool; (3) review of pain assessment tool by SCD team; (4) development of collaborative home plan with family and the medical team; (4) integration of nonpharmacological strategies into the home plan (developed with the psychologist); (5) printed copy of the plan for family to take home; (6) documentation of HPMP in the EMR (Table 2); and, (7) a follow-up phone call for eligible patients with ED or urgent care visits for uncomplicated SCD pain by the nurse care manager.

Implementation

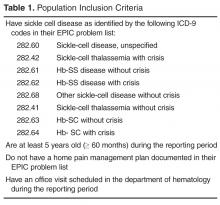

Each week the data analyst generated a list of eligible patients with ICD-9 diagnostic codes for SCD using SQL (structured query language) to extract the data from the EMR (Table 1). The SCD nurse care managers reviewed the list and notified the team of those patients needing a pain assessment and updated HPMP during the daily pre-clinic patient review rounds each morning.

The provider seeing the patient that day facilitated the patient and family’s completion of the pain assessment tool. The pain assessment tool consisted of 13 items and measured recent illnesses or transfusions, patient’s pain location, intensity, associated symptoms, potential triggers, and the impact of the pain on quality of life (missed days of school/work). In addition, the patient’s current pain management strategies, perceived effectiveness of those strategies, and analgesics available at home was recorded.

After discussing the results with the team, a medical provider reviewed the findings with the patient and family and developed a plan for pharmacologic pain management at home utilizing a stepwise approach based on the World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder for selecting pain-relief drugs [4,5] and the American Pain Society guidelines for management of acute and chronic sickle cell pain [6]. The medication’s method of action, side effects, risks, and benefits were reviewed and prescriptions were provided as needed.

During the same visit, patients who reported acute or chronic pain within the last month met with the team psychology provider. The psychology provider educated the patient and family about pain, the mind-body connection, and nonpharmacologic approaches to pain management that could be incorporated in the home plan. Following the education, the psychology provider taught the patient at least one relaxation strategy (eg, diaphragmatic breathing, guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation) and provided written materials to take home to encourage practice. At the time of discharge from the clinic, patients and families received a copy of the comprehensive home pain plan and any needed prescriptions for analgesics. Families were encouraged to access a copy of their plan at home by logging on to MyChart (Epic Systems), a limited version of the child’s EMR designed for patients and families.

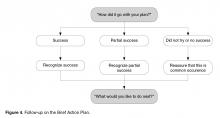

After each ED or urgent care visit for uncomplicated SCD pain, the nurse care manager attempted to call the family within 3 business days to ask whether the home pain management plan had been used and determine if it needed to be revised. Medication refills were confirmed via phone follow-up by the nurse care manager at this time. Laminated pocket guides for the care managers facilitated and standardized the follow-up questions. A maximum of 3 attempts were made to contact the family. Information from the telephone encounter was documented in the patient’s EMR in a standard format and location. This information was then communicated to the SCD provider (nurse practitioner or physician) who modified the plan as needed. If the patient did not have any ED or acute care outpatient visits, the HPMP was reviewed every 6 months at a routinely scheduled comprehensive visit.

The team used multiple plan-do-study-act cycles (PDSAs) to refine the intervention and implementation process. One PDSA involved a focus group consisting of 3 young adult patients and 1 parent. Participants were asked if they knew what we were referring to when we used the term “home pain management plan,” what they remembered about their plan, and if they thought we should keep or change the name. All 4 participants reported that they were familiar with the term and were able to describe aspects of their or their child’s home pain management plan. Although 1 participant suggested shortening the name, the SCD team had worked to develop a high level of familiarity with the name, so it was retained. Another PDSA was conducted to assess whether the pediatric hematology fellows (post-graduate trainees) were aware of the HPMP and how to access it in the EMR. Eight of the 10 fellows responded, and the majority indicated that they were aware of the HPMP; however, only 1 fellow knew where to locate it in the EMR. This resulted in PDSAs to increase fellows’ awareness and use of the HPMP.

The QI team also completed a failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) to identify potential failures in the clinic flow process. The FMEA helped to identify low-hanging fruit “quick fixes,” PDSAs, and develop process maps. Weekly data guided our PDSAs and allowed us to continuously improve our processes, and team members were accountable for specific weekly action items.

Measurement/Analysis

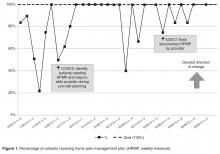

The home pain management implementation process was monitored and tracked using 2 weekly run charts: one that displayed the percentage of eligible SCD patients who needed a HPMP each week that actually received one and one that showed the overall number of eligible SCD patients with a HPMP (population metric). Run charts provide a graphic display of process performance over time and allowed the team to track and monitor process outcomes. The goal was that at least 85% of eligible patients would receive the HPMP intervention by November 2012.

Outcomes were evaluated using a monthly p-chart showing the percentage of SCD patients seen in the ED for uncomplicated SCD pain. For the current project, a p-chart was used because ED visits were categorized (see below) and the sample size varied by month. We conducted a retrospective chart review of each ED visit to extract the initial complaint and the final assessment from the ED providers’ notes. ED visits were categorized as follows: (1) fever (with or without other symptoms such as pain), (2) uncomplicated SCD pain only, and (3) other (eg, trauma, asthma). The goal was to monitor ED visits for uncomplicated SCD pain only to determine if the rate of this type of ED visit decreased after the implementation of the HPMP. Based on the chart review of the 12 months prior to the implementation of the HPMP, the majority of SCD patients seen in the ED had 0–3 ED visits for uncomplicated SCD pain. Only 7 patients had more than 3 ED visits: two had 4 ED visits, two had 5 ED visits, one had 6 visits, one had 7 visits, and one had 13 visits to the ED. Because the patient with 13 visits has complex psychosocial issues that greatly impact the use of the ED and inpatient medical services, this data was excluded from our analyses.

The Children’s Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board exempted this study from review because it was deemed to be a QI project with the intent to improve care locally and not to develop generalizable

knowledge.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Using quality improvement methods, an individualized home pain management intervention was incorporated successfully into the daily workflow of a busy outpatient SCD clinic. The QI team provided critical guidance, organization, and resources for refining the HPMP intervention and implementing it into a very busy outpatient clinical setting. QI methods such as the PDSAs, FMEA, and process maps allowed us to continuously improve the intervention and develop an effective implementation process. As a result, we were able to reach our goal of ensuring that 100% of eligible patients received a HPMP during their clinic visit.

Several studies have shown cognitive-behavioral therapies, such as relaxation, imagery, and self-hypnosis, to improve outcomes in children and adults with SCD [7–10]. We believe that having psychology providers on our team who could train families in nonpharmacological strategies was critical to the project’s success. Most SCD patients are taught to increase fluid intake and use warm compresses, but few are trained in adjunctive nonpharmacologic strategies while awaiting the effects of oral analgesics. Thus, our multidisciplinary protocol is innovative; future studies may show it to to be more effective than interventions using pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic strategies alone.

Implementing a comprehensive home pain management intervention in a very busy clinical setting was challenging; it required a substantial coordination and communication among the clinical team. Although each member of the team had a well-defined role, we found that our nurse care managers were the drivers of the process during the clinic visit. They ensured the documentation of the HPMP and reconciliation of medications were completed in the EMR, that prescriptions for analgesics were written and educated families to execute the HPMP.

We were able to exceed our goal of ensuring that at least 85% of eligible patients in our population had a home plan in place. This is clinically significant as most SCD pain episodes occur at home [11]. Typically, the pain management strategies used by patients and families at home are inconsistent, and several studies indicate that parents may be reluctant to use analgesics for their children, use a dose that is too small, or do not give the medicine often enough [12–14]. Developing an home pain plan with a patient and family allowed for education about distinguishing different types of pain and the appropriate use of medications for specific types of pain.

Challenges to implementation of the home plan protocol included limited time during clinics visit to integrate the plan given competing clinical issues. Some families felt the visit lasted too long and were eager to leave the clinic without further delays. Additionally, the fixed design of the EMR posed some limitations related to documentation, medication reconciliation, and updating of the home plan because different team members could not simultaneously access some parts of the EMR. We also initially overlooked the need to educate other providers in our division about the home plan, such as fellows who take calls about patients after hours. This has subsequently been addressed via ongoing PDSAs to test processes for making fellows aware of the home pain plan and to ensure they use it consistently to coordinate care.