User login

Improved Safety Event Reporting in Outpatient, Nonacademic Practices with an Anonymous, Nonpunitive Approach

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of an educational intervention with regular audit and feedback on reporting of patient safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting with an established reporting system.

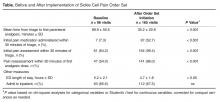

- Methods: A quasi-experimental with comparator design was used to compare a 6-practice collaborative group with a 27-practice comparator group with regard to safety event reporting rates. Baseline data were collected for a 12-month period followed by recruitment of 6 practices (3 family medicine, 2 pediatric, and 1 general surgery). An educational intervention was carried out with each, and this was followed by monthly audit and regular written and in-person feedback. Practice-level comparisons were made with specialty- and size-matched practices for the 6 practices in the collaborative group.

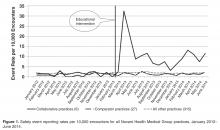

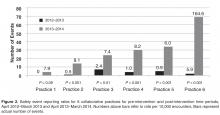

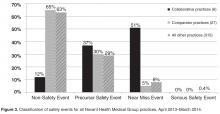

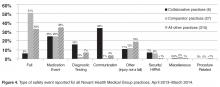

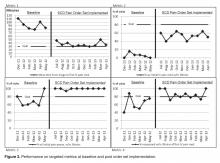

- Results: In the 12-month period following the intervention in March 2013, the 6 practices reported 175 patient safety events compared with only 19 events in the previous 12-month period. Each practice at least doubled reporting rates, and 5 of the 6 significantly increased rates. In contrast, rates for comparator practices were unchanged, with 84 events reported for the pre-intervention period and 81 for the post-intervention period. Event classification and types of events reported were different in the collaborative practices compared with the comparators for the post-intervention period. For the collaborative group, near miss events predominated as did diagnostic testing and communication event types.

- Conclusion: An initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback and a focus on developing a nonpunitive environment can significantly enhance reporting of safety events.

Multiple challenges in the outpatient setting make establishing a culture of safety and improving care delivery more difficult than for inpatient settings. In the outpatient setting, care is often inaccessible, not well coordinated between providers and between facilities and providers, and delivered in many locations. It may also involve multiple sites and providers for a single patient, may require multiple visits in a single location, and can be provided by phone, email, mail, video, or in person [1]. Errors and adverse events may take long periods of time to become apparent and are more often errors of omission compared with those in the inpatient setting [2].

Incident reporting systems are considered important in improving patient safety [3], and their limitations and value have recently been reviewed [4]. However, limited research has been conducted on medical errors in ambulatory care, and even less is available on optimal monitoring and reporting strategies [5–12].Reporting in our system is time-consuming (about 15 minutes for entry of a single report), is not tailored for outpatient practices, may be considered potentially punitive (staff may believe that reporting may place themselves at risk for performance downgrade or other actions), and marked under-reporting of safety events was suspected. Most but not all of the suggested characteristics considered important for hospital-based reporting systems are fulfilled in our ambulatory reporting system [13].

Several academic groups have reported much improved reporting and a much better understanding of the types of errors occurring in their respective outpatient settings [14–16]. The most compelling model includes a voluntary, nonpunitive, anonymous reporting approach and a multidisciplinary practice-specific team to analyze reported errors and to enact change through a continuous quality improvement process [14,15].

We implemented a project to significantly improve reporting of safety events in an outpatient, nonacademic 6-practice collaborative by using education, monthly audit, and regular feedback.

Methods

Setting

Novant Health Medical Group is a consortium of over 380 clinic sites, nearly 1300 physicians, and over 500 advanced practice clinicians. Clinic locations are found in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Medical group members partner with physicians and staff in 15 hospitals in these geographic locations. Novant Health utilizes Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as an electronic health record. Safety event reporting is accomplished electronically in a single software program (VIncident, Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC), used for all patients in our integrated care system (inpatient and outpatient facilities).

Intervention

Two of the authors (HWC and TC) met in March 2013 with the lead physician, practice manager, and patient safety coach at each clinic for approximately 1 hour. We discussed current reporting practice, delivered education for the safety event compendium, and detailed an anonymous, voluntary, and nonpunitive approach (stressing the use of the term “safety event” and not “error”) to reporting using a single page, 8-question paper report about the event. The report was not to be signed by the person completing the event data with placement in a drop box for later collection and electronic reporting as per usual practice in the clinic. We agreed that clinic leaders would stress to staff and providers that the initiative was nonpunitive and anonymous and that the goal was to report all known safety events, as an improvement project.

Patient safety coaches were selected for each of the 6 practices by the manager. Patient safety coaches are volunteer clinical or nonclinical staff members whose role is to observe, model, and reinforce pre-established patient safety behaviors and use of error prevention tools among peers and providers. Training requirements include an initial 2-hour training session in which they learn fundamentals of patient safety science, high reliability principles, coaching techniques for team accountability, and concepts for continuous quality improvement. Additionally, they attend monthly meetings where patient safety concepts are discussed in greater detail and best practices are shared. Following this training, each clinic’s staff was educated on the project, a process improvement team (lead physician, manager, and patient safety coach) was constituted, and the project was begun in April 2013. In quarter 3 of 2013, each practice team selected a quality improvement project based upon reported safety events in their clinic. We asked our medical group risk managers to continue event discussion with practice managers as usual, as each event is discussed briefly after a report is made.

We audited reports monthly and provided feedback to the practice team with a written report at the end of each 3-month period starting in June 2013 and ending in June 2014 (5 reports). Individual on-site visits to meet and discuss progress were completed in September 2013 and March 2014, in addition to the initial visit in March 2013.

Evaluation

We compared reported monthly safety events for each of the 6 practices and for the 6-practice collaborative in the aggregate for the 12-month pre-intervention period (April 2012 through March 2013) and post-intervention period (April 2013 through March 2014). Each practice was compared with 3 specialty- and size (number of providers)-matched practices, none of whom received education or feedback on reporting or had patient safety coaches in the practice. In addition, for each of the 3 family medicine practices in the collaborative, we matched 1:3 other family medicine practices for specialty, size, and presence of a designated and trained patient safety coach. For the duration of the project, only 50 of 380 practices in the medical group had a trained patient safety coach.

The rate of safety events reported (ie, number of safety events reported/number of patient encounters) was compared for the 2 time periods using Poisson regression or zero-inflated Poisson regression. SASenterprise guide5.1 was used for all analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board of Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center and a waiver for informed written consent was granted.

Results

To control for the presence of patient safety coaches in practices, the 3 family medicine clinics (clinics 4 through 6, Figure 2) were each matched 1:3 for size (number of providers) and specialty (other family medicine clinics), also with a patient safety coach. While the rates were significantly increased for the 3 collaborative family medicine clinics (P < 0.001), only 1 of the comparators clinic’s rate changed significantly (0.2 or 1/44,580 to 1.3 or 6/45,157), and this change was marginally significant (P = 0.048). This practice was the only one of the 27 comparator clinics to demonstrate any increased rate.

Discussion

In our nonacademic community practices, patient safety reporting rates improved following an initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback. Our findings corroborate those of others in academic ambulatory settings, who found that an emphasis on patient safety reporting, particularly if an anonymous approach is taken in a nonpunitive atmosphere, can significantly increase the reporting of patient safety events [14–16]. We demonstrated marked under-reporting and stability of patient safety event reporting throughout our ambulatory practice group and a 10-fold increase in reporting among the 6-practice collaborative.

An unexpected finding was that with the exception of 1 practice, we found no increased reporting in comparator practices that had a patient safety coach. Additionally, we noted that general surgery practices report (or experience) very few ambulatory safety events, as a total of 4 events were reported for all 4 general surgery practices in 18 months.

We chose a quasi-experimental with a comparison group and pre-test/post-test design since randomization of practices was not feasible [17]. We used a 2-year period to control for any seasonal trends and to allow time after the intervention to see if meaningful improvement in reporting over time would continue. We attempted to address the potential for nonequivalence in the comparison group by matching for specialty and size of practice.

There are several limitations to this study. Bias in the selection of collaborative practices may have occurred since each had a proven leader, and this may have led to more rapid adoption and utilization of this reporting approach. Also, our findings may not be generalizable to other integrated health systems given the unique approaches to patient safety culture development and the disparate nature of reporting systems. In addition, with our study design we could not be certain that anonymous reporting was a key factor in the increase in reporting rates, but de-briefing interviews indicated that both anonymous reporting and declaring a nonpunitive, supportive approach in each practice was important to enhanced reporting.

We expect increased reporting to decline over time without consistent feedback, as has been demonstrated in other studies [18], and we will continue to monitor rates over time.

As our current reporting system requires considerable reporter time for data input and discussion with risk managers, is not specifically configured for ambulatory reporting, is considered by staff and providers potentially punitive, and marked under-reporting is clear, we have proposed moving to a new system that is more user-friendly, ambulatory-focused, and has a provision for anonymous reporting.

Presented in part at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement 15th Annual International Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community, Washington DC, March 2014.

Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the work of collaborative practice team members, including Christopher Isenhour MD, Janet White, Shelby Carlyle, Mark Tillotson MD, Maria Migliaccio, Melanie Trapp, Jennifer Ochs, Gary DeRosa MD, Margarete Hinkle, Scott Wagner, Kelly Schetselaar, Timothy Eichenbrenner MD, Sandy Hite, Jamie Shelton, Raymond Swetenburg MD, James Lye MD, Kelly Morrison, Jan Rapisardo, Jane Moss, Rhett Brown MD, Dorothy Hedrick, Camille Farmer, and William Anderson, MS, for assistance with analysis.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Tang N, Meyer GS. Ambulatory patient safety: The time is now. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1487–9.

2. Ghandi TK, Lee TH. Patient safety beyond the hospital. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1001–3.

3. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

4. Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public Health Res 2013;2:e27.

5. Elder NC, Dovey SM. Classification of medical errors and preventable adverse events in primary care: A synthesis of the literature. J Fam Pract 2002;51:927–32.

6. Mohr JJ, Lannon CM, Thoma KA, et al. Learning from errors in ambulatory pediatrics. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005: 355–68. Available at www.ahrq.gov//downloads/pub/advances/vol1/Mohr.pdf.

7. Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Graham D, et al. Learning from different lenses: reports of medical errors in primary care by clinicians, staff, and patients. J Patient Saf 2006;2:140–6.

8. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Khan MM, Peterson LA. Identifying diagnostic errors in primary care using an electronic screening algorithm. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:302–8.

9. Rappaport DI, Collins B, Koster A, et al. Implementing medication reconciliation in outpatient pediatrics. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1600-e1607.

10. Bishop TF, Ryan AK, Casalino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA 2011;305:2427–31.

11. Wynia MK, Classen DC. Improving ambulatory patient safety. Learning from the last decade, moving ahead in the next. JAMA 2011;306:2504–5.

12. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

13. Leape LL. Patient safety. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1633–8.

14. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH, Liggin L. Improving reporting of outpatient medical errors. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1608–e1613.

15. Neuspiel DR, Gizman M, Harewood C. Improving error reporting in ambulatory pediatrics with team approach. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches. Vol 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43643/.

16. Plews-Ogan ML, Nadkarni MM, Forren S, et al. Patient safety in the ambulatory setting: a clinician-based approach. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:719–25.

17. Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:16–23.

18. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of an educational intervention with regular audit and feedback on reporting of patient safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting with an established reporting system.

- Methods: A quasi-experimental with comparator design was used to compare a 6-practice collaborative group with a 27-practice comparator group with regard to safety event reporting rates. Baseline data were collected for a 12-month period followed by recruitment of 6 practices (3 family medicine, 2 pediatric, and 1 general surgery). An educational intervention was carried out with each, and this was followed by monthly audit and regular written and in-person feedback. Practice-level comparisons were made with specialty- and size-matched practices for the 6 practices in the collaborative group.

- Results: In the 12-month period following the intervention in March 2013, the 6 practices reported 175 patient safety events compared with only 19 events in the previous 12-month period. Each practice at least doubled reporting rates, and 5 of the 6 significantly increased rates. In contrast, rates for comparator practices were unchanged, with 84 events reported for the pre-intervention period and 81 for the post-intervention period. Event classification and types of events reported were different in the collaborative practices compared with the comparators for the post-intervention period. For the collaborative group, near miss events predominated as did diagnostic testing and communication event types.

- Conclusion: An initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback and a focus on developing a nonpunitive environment can significantly enhance reporting of safety events.

Multiple challenges in the outpatient setting make establishing a culture of safety and improving care delivery more difficult than for inpatient settings. In the outpatient setting, care is often inaccessible, not well coordinated between providers and between facilities and providers, and delivered in many locations. It may also involve multiple sites and providers for a single patient, may require multiple visits in a single location, and can be provided by phone, email, mail, video, or in person [1]. Errors and adverse events may take long periods of time to become apparent and are more often errors of omission compared with those in the inpatient setting [2].

Incident reporting systems are considered important in improving patient safety [3], and their limitations and value have recently been reviewed [4]. However, limited research has been conducted on medical errors in ambulatory care, and even less is available on optimal monitoring and reporting strategies [5–12].Reporting in our system is time-consuming (about 15 minutes for entry of a single report), is not tailored for outpatient practices, may be considered potentially punitive (staff may believe that reporting may place themselves at risk for performance downgrade or other actions), and marked under-reporting of safety events was suspected. Most but not all of the suggested characteristics considered important for hospital-based reporting systems are fulfilled in our ambulatory reporting system [13].

Several academic groups have reported much improved reporting and a much better understanding of the types of errors occurring in their respective outpatient settings [14–16]. The most compelling model includes a voluntary, nonpunitive, anonymous reporting approach and a multidisciplinary practice-specific team to analyze reported errors and to enact change through a continuous quality improvement process [14,15].

We implemented a project to significantly improve reporting of safety events in an outpatient, nonacademic 6-practice collaborative by using education, monthly audit, and regular feedback.

Methods

Setting

Novant Health Medical Group is a consortium of over 380 clinic sites, nearly 1300 physicians, and over 500 advanced practice clinicians. Clinic locations are found in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Medical group members partner with physicians and staff in 15 hospitals in these geographic locations. Novant Health utilizes Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as an electronic health record. Safety event reporting is accomplished electronically in a single software program (VIncident, Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC), used for all patients in our integrated care system (inpatient and outpatient facilities).

Intervention

Two of the authors (HWC and TC) met in March 2013 with the lead physician, practice manager, and patient safety coach at each clinic for approximately 1 hour. We discussed current reporting practice, delivered education for the safety event compendium, and detailed an anonymous, voluntary, and nonpunitive approach (stressing the use of the term “safety event” and not “error”) to reporting using a single page, 8-question paper report about the event. The report was not to be signed by the person completing the event data with placement in a drop box for later collection and electronic reporting as per usual practice in the clinic. We agreed that clinic leaders would stress to staff and providers that the initiative was nonpunitive and anonymous and that the goal was to report all known safety events, as an improvement project.

Patient safety coaches were selected for each of the 6 practices by the manager. Patient safety coaches are volunteer clinical or nonclinical staff members whose role is to observe, model, and reinforce pre-established patient safety behaviors and use of error prevention tools among peers and providers. Training requirements include an initial 2-hour training session in which they learn fundamentals of patient safety science, high reliability principles, coaching techniques for team accountability, and concepts for continuous quality improvement. Additionally, they attend monthly meetings where patient safety concepts are discussed in greater detail and best practices are shared. Following this training, each clinic’s staff was educated on the project, a process improvement team (lead physician, manager, and patient safety coach) was constituted, and the project was begun in April 2013. In quarter 3 of 2013, each practice team selected a quality improvement project based upon reported safety events in their clinic. We asked our medical group risk managers to continue event discussion with practice managers as usual, as each event is discussed briefly after a report is made.

We audited reports monthly and provided feedback to the practice team with a written report at the end of each 3-month period starting in June 2013 and ending in June 2014 (5 reports). Individual on-site visits to meet and discuss progress were completed in September 2013 and March 2014, in addition to the initial visit in March 2013.

Evaluation

We compared reported monthly safety events for each of the 6 practices and for the 6-practice collaborative in the aggregate for the 12-month pre-intervention period (April 2012 through March 2013) and post-intervention period (April 2013 through March 2014). Each practice was compared with 3 specialty- and size (number of providers)-matched practices, none of whom received education or feedback on reporting or had patient safety coaches in the practice. In addition, for each of the 3 family medicine practices in the collaborative, we matched 1:3 other family medicine practices for specialty, size, and presence of a designated and trained patient safety coach. For the duration of the project, only 50 of 380 practices in the medical group had a trained patient safety coach.

The rate of safety events reported (ie, number of safety events reported/number of patient encounters) was compared for the 2 time periods using Poisson regression or zero-inflated Poisson regression. SASenterprise guide5.1 was used for all analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board of Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center and a waiver for informed written consent was granted.

Results

To control for the presence of patient safety coaches in practices, the 3 family medicine clinics (clinics 4 through 6, Figure 2) were each matched 1:3 for size (number of providers) and specialty (other family medicine clinics), also with a patient safety coach. While the rates were significantly increased for the 3 collaborative family medicine clinics (P < 0.001), only 1 of the comparators clinic’s rate changed significantly (0.2 or 1/44,580 to 1.3 or 6/45,157), and this change was marginally significant (P = 0.048). This practice was the only one of the 27 comparator clinics to demonstrate any increased rate.

Discussion

In our nonacademic community practices, patient safety reporting rates improved following an initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback. Our findings corroborate those of others in academic ambulatory settings, who found that an emphasis on patient safety reporting, particularly if an anonymous approach is taken in a nonpunitive atmosphere, can significantly increase the reporting of patient safety events [14–16]. We demonstrated marked under-reporting and stability of patient safety event reporting throughout our ambulatory practice group and a 10-fold increase in reporting among the 6-practice collaborative.

An unexpected finding was that with the exception of 1 practice, we found no increased reporting in comparator practices that had a patient safety coach. Additionally, we noted that general surgery practices report (or experience) very few ambulatory safety events, as a total of 4 events were reported for all 4 general surgery practices in 18 months.

We chose a quasi-experimental with a comparison group and pre-test/post-test design since randomization of practices was not feasible [17]. We used a 2-year period to control for any seasonal trends and to allow time after the intervention to see if meaningful improvement in reporting over time would continue. We attempted to address the potential for nonequivalence in the comparison group by matching for specialty and size of practice.

There are several limitations to this study. Bias in the selection of collaborative practices may have occurred since each had a proven leader, and this may have led to more rapid adoption and utilization of this reporting approach. Also, our findings may not be generalizable to other integrated health systems given the unique approaches to patient safety culture development and the disparate nature of reporting systems. In addition, with our study design we could not be certain that anonymous reporting was a key factor in the increase in reporting rates, but de-briefing interviews indicated that both anonymous reporting and declaring a nonpunitive, supportive approach in each practice was important to enhanced reporting.

We expect increased reporting to decline over time without consistent feedback, as has been demonstrated in other studies [18], and we will continue to monitor rates over time.

As our current reporting system requires considerable reporter time for data input and discussion with risk managers, is not specifically configured for ambulatory reporting, is considered by staff and providers potentially punitive, and marked under-reporting is clear, we have proposed moving to a new system that is more user-friendly, ambulatory-focused, and has a provision for anonymous reporting.

Presented in part at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement 15th Annual International Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community, Washington DC, March 2014.

Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the work of collaborative practice team members, including Christopher Isenhour MD, Janet White, Shelby Carlyle, Mark Tillotson MD, Maria Migliaccio, Melanie Trapp, Jennifer Ochs, Gary DeRosa MD, Margarete Hinkle, Scott Wagner, Kelly Schetselaar, Timothy Eichenbrenner MD, Sandy Hite, Jamie Shelton, Raymond Swetenburg MD, James Lye MD, Kelly Morrison, Jan Rapisardo, Jane Moss, Rhett Brown MD, Dorothy Hedrick, Camille Farmer, and William Anderson, MS, for assistance with analysis.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Novant Health and Novant Health Medical Group, Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Objective: To evaluate the effect of an educational intervention with regular audit and feedback on reporting of patient safety events in a nonacademic, community practice setting with an established reporting system.

- Methods: A quasi-experimental with comparator design was used to compare a 6-practice collaborative group with a 27-practice comparator group with regard to safety event reporting rates. Baseline data were collected for a 12-month period followed by recruitment of 6 practices (3 family medicine, 2 pediatric, and 1 general surgery). An educational intervention was carried out with each, and this was followed by monthly audit and regular written and in-person feedback. Practice-level comparisons were made with specialty- and size-matched practices for the 6 practices in the collaborative group.

- Results: In the 12-month period following the intervention in March 2013, the 6 practices reported 175 patient safety events compared with only 19 events in the previous 12-month period. Each practice at least doubled reporting rates, and 5 of the 6 significantly increased rates. In contrast, rates for comparator practices were unchanged, with 84 events reported for the pre-intervention period and 81 for the post-intervention period. Event classification and types of events reported were different in the collaborative practices compared with the comparators for the post-intervention period. For the collaborative group, near miss events predominated as did diagnostic testing and communication event types.

- Conclusion: An initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback and a focus on developing a nonpunitive environment can significantly enhance reporting of safety events.

Multiple challenges in the outpatient setting make establishing a culture of safety and improving care delivery more difficult than for inpatient settings. In the outpatient setting, care is often inaccessible, not well coordinated between providers and between facilities and providers, and delivered in many locations. It may also involve multiple sites and providers for a single patient, may require multiple visits in a single location, and can be provided by phone, email, mail, video, or in person [1]. Errors and adverse events may take long periods of time to become apparent and are more often errors of omission compared with those in the inpatient setting [2].

Incident reporting systems are considered important in improving patient safety [3], and their limitations and value have recently been reviewed [4]. However, limited research has been conducted on medical errors in ambulatory care, and even less is available on optimal monitoring and reporting strategies [5–12].Reporting in our system is time-consuming (about 15 minutes for entry of a single report), is not tailored for outpatient practices, may be considered potentially punitive (staff may believe that reporting may place themselves at risk for performance downgrade or other actions), and marked under-reporting of safety events was suspected. Most but not all of the suggested characteristics considered important for hospital-based reporting systems are fulfilled in our ambulatory reporting system [13].

Several academic groups have reported much improved reporting and a much better understanding of the types of errors occurring in their respective outpatient settings [14–16]. The most compelling model includes a voluntary, nonpunitive, anonymous reporting approach and a multidisciplinary practice-specific team to analyze reported errors and to enact change through a continuous quality improvement process [14,15].

We implemented a project to significantly improve reporting of safety events in an outpatient, nonacademic 6-practice collaborative by using education, monthly audit, and regular feedback.

Methods

Setting

Novant Health Medical Group is a consortium of over 380 clinic sites, nearly 1300 physicians, and over 500 advanced practice clinicians. Clinic locations are found in Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Medical group members partner with physicians and staff in 15 hospitals in these geographic locations. Novant Health utilizes Epic (Epic Systems, Verona, WI) as an electronic health record. Safety event reporting is accomplished electronically in a single software program (VIncident, Verge Solutions, Mt. Pleasant, SC), used for all patients in our integrated care system (inpatient and outpatient facilities).

Intervention

Two of the authors (HWC and TC) met in March 2013 with the lead physician, practice manager, and patient safety coach at each clinic for approximately 1 hour. We discussed current reporting practice, delivered education for the safety event compendium, and detailed an anonymous, voluntary, and nonpunitive approach (stressing the use of the term “safety event” and not “error”) to reporting using a single page, 8-question paper report about the event. The report was not to be signed by the person completing the event data with placement in a drop box for later collection and electronic reporting as per usual practice in the clinic. We agreed that clinic leaders would stress to staff and providers that the initiative was nonpunitive and anonymous and that the goal was to report all known safety events, as an improvement project.

Patient safety coaches were selected for each of the 6 practices by the manager. Patient safety coaches are volunteer clinical or nonclinical staff members whose role is to observe, model, and reinforce pre-established patient safety behaviors and use of error prevention tools among peers and providers. Training requirements include an initial 2-hour training session in which they learn fundamentals of patient safety science, high reliability principles, coaching techniques for team accountability, and concepts for continuous quality improvement. Additionally, they attend monthly meetings where patient safety concepts are discussed in greater detail and best practices are shared. Following this training, each clinic’s staff was educated on the project, a process improvement team (lead physician, manager, and patient safety coach) was constituted, and the project was begun in April 2013. In quarter 3 of 2013, each practice team selected a quality improvement project based upon reported safety events in their clinic. We asked our medical group risk managers to continue event discussion with practice managers as usual, as each event is discussed briefly after a report is made.

We audited reports monthly and provided feedback to the practice team with a written report at the end of each 3-month period starting in June 2013 and ending in June 2014 (5 reports). Individual on-site visits to meet and discuss progress were completed in September 2013 and March 2014, in addition to the initial visit in March 2013.

Evaluation

We compared reported monthly safety events for each of the 6 practices and for the 6-practice collaborative in the aggregate for the 12-month pre-intervention period (April 2012 through March 2013) and post-intervention period (April 2013 through March 2014). Each practice was compared with 3 specialty- and size (number of providers)-matched practices, none of whom received education or feedback on reporting or had patient safety coaches in the practice. In addition, for each of the 3 family medicine practices in the collaborative, we matched 1:3 other family medicine practices for specialty, size, and presence of a designated and trained patient safety coach. For the duration of the project, only 50 of 380 practices in the medical group had a trained patient safety coach.

The rate of safety events reported (ie, number of safety events reported/number of patient encounters) was compared for the 2 time periods using Poisson regression or zero-inflated Poisson regression. SASenterprise guide5.1 was used for all analyses. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board of Novant Health Presbyterian Medical Center and a waiver for informed written consent was granted.

Results

To control for the presence of patient safety coaches in practices, the 3 family medicine clinics (clinics 4 through 6, Figure 2) were each matched 1:3 for size (number of providers) and specialty (other family medicine clinics), also with a patient safety coach. While the rates were significantly increased for the 3 collaborative family medicine clinics (P < 0.001), only 1 of the comparators clinic’s rate changed significantly (0.2 or 1/44,580 to 1.3 or 6/45,157), and this change was marginally significant (P = 0.048). This practice was the only one of the 27 comparator clinics to demonstrate any increased rate.

Discussion

In our nonacademic community practices, patient safety reporting rates improved following an initial educational session stressing anonymous, voluntary safety event reporting together with monthly audit and feedback. Our findings corroborate those of others in academic ambulatory settings, who found that an emphasis on patient safety reporting, particularly if an anonymous approach is taken in a nonpunitive atmosphere, can significantly increase the reporting of patient safety events [14–16]. We demonstrated marked under-reporting and stability of patient safety event reporting throughout our ambulatory practice group and a 10-fold increase in reporting among the 6-practice collaborative.

An unexpected finding was that with the exception of 1 practice, we found no increased reporting in comparator practices that had a patient safety coach. Additionally, we noted that general surgery practices report (or experience) very few ambulatory safety events, as a total of 4 events were reported for all 4 general surgery practices in 18 months.

We chose a quasi-experimental with a comparison group and pre-test/post-test design since randomization of practices was not feasible [17]. We used a 2-year period to control for any seasonal trends and to allow time after the intervention to see if meaningful improvement in reporting over time would continue. We attempted to address the potential for nonequivalence in the comparison group by matching for specialty and size of practice.

There are several limitations to this study. Bias in the selection of collaborative practices may have occurred since each had a proven leader, and this may have led to more rapid adoption and utilization of this reporting approach. Also, our findings may not be generalizable to other integrated health systems given the unique approaches to patient safety culture development and the disparate nature of reporting systems. In addition, with our study design we could not be certain that anonymous reporting was a key factor in the increase in reporting rates, but de-briefing interviews indicated that both anonymous reporting and declaring a nonpunitive, supportive approach in each practice was important to enhanced reporting.

We expect increased reporting to decline over time without consistent feedback, as has been demonstrated in other studies [18], and we will continue to monitor rates over time.

As our current reporting system requires considerable reporter time for data input and discussion with risk managers, is not specifically configured for ambulatory reporting, is considered by staff and providers potentially punitive, and marked under-reporting is clear, we have proposed moving to a new system that is more user-friendly, ambulatory-focused, and has a provision for anonymous reporting.

Presented in part at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement 15th Annual International Summit on Improving Patient Care in the Office Practice and the Community, Washington DC, March 2014.

Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge the work of collaborative practice team members, including Christopher Isenhour MD, Janet White, Shelby Carlyle, Mark Tillotson MD, Maria Migliaccio, Melanie Trapp, Jennifer Ochs, Gary DeRosa MD, Margarete Hinkle, Scott Wagner, Kelly Schetselaar, Timothy Eichenbrenner MD, Sandy Hite, Jamie Shelton, Raymond Swetenburg MD, James Lye MD, Kelly Morrison, Jan Rapisardo, Jane Moss, Rhett Brown MD, Dorothy Hedrick, Camille Farmer, and William Anderson, MS, for assistance with analysis.

Corresponding author: Herbert Clegg, MD, 108 Providence Road, Charlotte NC, 28207, hwclegg@novanthealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Tang N, Meyer GS. Ambulatory patient safety: The time is now. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1487–9.

2. Ghandi TK, Lee TH. Patient safety beyond the hospital. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1001–3.

3. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

4. Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public Health Res 2013;2:e27.

5. Elder NC, Dovey SM. Classification of medical errors and preventable adverse events in primary care: A synthesis of the literature. J Fam Pract 2002;51:927–32.

6. Mohr JJ, Lannon CM, Thoma KA, et al. Learning from errors in ambulatory pediatrics. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005: 355–68. Available at www.ahrq.gov//downloads/pub/advances/vol1/Mohr.pdf.

7. Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Graham D, et al. Learning from different lenses: reports of medical errors in primary care by clinicians, staff, and patients. J Patient Saf 2006;2:140–6.

8. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Khan MM, Peterson LA. Identifying diagnostic errors in primary care using an electronic screening algorithm. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:302–8.

9. Rappaport DI, Collins B, Koster A, et al. Implementing medication reconciliation in outpatient pediatrics. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1600-e1607.

10. Bishop TF, Ryan AK, Casalino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA 2011;305:2427–31.

11. Wynia MK, Classen DC. Improving ambulatory patient safety. Learning from the last decade, moving ahead in the next. JAMA 2011;306:2504–5.

12. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

13. Leape LL. Patient safety. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1633–8.

14. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH, Liggin L. Improving reporting of outpatient medical errors. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1608–e1613.

15. Neuspiel DR, Gizman M, Harewood C. Improving error reporting in ambulatory pediatrics with team approach. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches. Vol 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43643/.

16. Plews-Ogan ML, Nadkarni MM, Forren S, et al. Patient safety in the ambulatory setting: a clinician-based approach. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:719–25.

17. Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:16–23.

18. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

1. Tang N, Meyer GS. Ambulatory patient safety: The time is now. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1487–9.

2. Ghandi TK, Lee TH. Patient safety beyond the hospital. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1001–3.

3. Institute of Medicine. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 1999.

4. Pham JC, Girard T, Pronovost PJ. What to do with healthcare incident reporting systems. J Public Health Res 2013;2:e27.

5. Elder NC, Dovey SM. Classification of medical errors and preventable adverse events in primary care: A synthesis of the literature. J Fam Pract 2002;51:927–32.

6. Mohr JJ, Lannon CM, Thoma KA, et al. Learning from errors in ambulatory pediatrics. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: from research to implementation. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005: 355–68. Available at www.ahrq.gov//downloads/pub/advances/vol1/Mohr.pdf.

7. Phillips RL, Dovey SM, Graham D, et al. Learning from different lenses: reports of medical errors in primary care by clinicians, staff, and patients. J Patient Saf 2006;2:140–6.

8. Singh H, Thomas EJ, Khan MM, Peterson LA. Identifying diagnostic errors in primary care using an electronic screening algorithm. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:302–8.

9. Rappaport DI, Collins B, Koster A, et al. Implementing medication reconciliation in outpatient pediatrics. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1600-e1607.

10. Bishop TF, Ryan AK, Casalino LP. Paid malpractice claims for adverse events in inpatient and outpatient settings. JAMA 2011;305:2427–31.

11. Wynia MK, Classen DC. Improving ambulatory patient safety. Learning from the last decade, moving ahead in the next. JAMA 2011;306:2504–5.

12. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH. Patient safety in ambulatory care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2012;59:1341–54.

13. Leape LL. Patient safety. Reporting of adverse events. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1633–8.

14. Neuspiel DR, Stubbs EH, Liggin L. Improving reporting of outpatient medical errors. Pediatrics 2011;128:e1608–e1613.

15. Neuspiel DR, Gizman M, Harewood C. Improving error reporting in ambulatory pediatrics with team approach. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, et al, editors. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches. Vol 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43643/.

16. Plews-Ogan ML, Nadkarni MM, Forren S, et al. Patient safety in the ambulatory setting: a clinician-based approach. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:719–25.

17. Harris AD, McGregor JC, Perencevich EN, et al. The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:16–23.

18. Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA 2014;312:2569–70.

Changing Hospital Visiting Policies: From Families as “Visitors” to Families as Partners

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken, Ms. Kaufman, and Ms. Johnson), Anne Arundel Medical Center, Annapolis, MD (Dr. Perkins), Contra Costa Regional Medical Center & Health Centers, Martinez, CA (Ms. Benepal, Ms. Roth, and Vidant Health, Greenville, NC (Ms. Dutton and Ms. Jones).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a campaign to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care.

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: Many hospitals still have “visiting” hours that limit family presence, often counter to patient preferences. To change the concept of families as visitors and eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families, calling on all hospitals to welcome families 24 hours a day and transform their policies and approaches to care so that patients’ families and loved ones are included in care and decision making, according to patient preferences. As part of the campaign, IPFCC recognized 12 hospitals that exemplify success in eliminating restrictive visiting policies and have changed the concept of families from “visitors” to partners. Leaders at these hospitals attest to the benefits of the changes through improved experience of care and other outcomes. Three exemplar hospitals are highlighted in this article and share their processes of change as well as key learnings and outcomes.

- Conclusion: Hospital policies and practices that encourage and support families as partners in care are essential to patients’ health, well-being, and safety.

Many families are restricted from the bedsides of loved ones because of hospital visiting policies [1–3]. Restrictive policies are often based on long-held beliefs that the presence and participation of families interferes with care, exhausts patients, is a burden to families, spreads infection, or violates HIPAA. However, there is no evidence to support those beliefs. In fact, isolating patients at their most vulnerable time from the people who know them best places them at risk for medical error, emotional harm, inconsistencies in care, and lack of preparedness for transitions in care [4,5]. Jackie Gruzenski’s story “Behind a Locked Door” (printed below) affectingly describes the impact of restrictive policies on a couple's last days.

Fortunately, a growing number of hospitals are lifting these restrictions. But opening the door is not enough. Hospitals need to change the concept of families as “visitors” to families as partners in care. Changing policies is a foundational step in creating a patient- and family-centered culture where families are recognized as essential to patients’ health and well-being and where they are respected as allies for quality and safety.

In response to this critical need for change, in June 2014 the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families. IPFCC, founded in 1992, is a nonprofit organization that provides essential leadership to advance the understanding and practice of patient- and family-centered care [6]. Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive “visiting” policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference [7]. The goal of the campaign is to change visiting policies in 1000 hospitals by 2017. Partnering with IPFCC in this initiative are the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management, American Association of Critical Care Nurses, National Partnership for Women & Families, New Yorkers for Patient and Family Empowerment, Health In Aging Foundation, and the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement.

Anne Arundel Medical Center

A regional not-for-profit hospital founded in 1902, Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis, MD, provides acute inpatient and outpatient care to residents of 4 counties in Maryland. A 380-bed facility, Anne Arundel has a cancer institute, heart and vascular institute, joint center, spine center, and a women’s and children’s center. In April 2011, the hospital completed a $424 million expansion project, which included a pediatric emergency room, an expanded general emergency room, 50 new patient beds, and 8 new operating rooms.

In 2010, based on a desire to concretely implement the principles of patient- and family-centered care, leaders at Anne Arundel began working with patient and family advisors and initiated a process to change the hospital’s restrictive visiting policy. Now, there are no restrictions on family presence anywhere in the hospital, from ICUs to medical/surgical units to other clinical areas. Patients have the power to choose who they want to stay with them—24 hours a day, 7 days a week. According to Anne Arundel’s policy, each patient determines who is defined as “family.” A “Revisiting Visiting” task force, comprising support staff, providers, and patient and family advisors, worked for 9 months to develop the new family presence policy and support its implementation.

With Anne Arundel leadership encouragement and support, patient and family advisors participated in all phases of the development and implementation of the new family presence policy and in other ways to advance the practice of patient- and family-centered care. The advisors also participated in the process to change the way nurse change of shift report was conducted, and they made recommendations for changes in the directional signs throughout the hospital. New signs, featuring a pineapple (a symbol of hospitality) and the words “Welcome Families” replaced old ones displaying the former restrictive visiting policy.

Supporting patient and family involvement in transitions in care is an integral aspect of implementing family presence policies and practices. Through an “Always Events” grant from the Picker Institute (for information about the Always Events program, see www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/PatientFamilyCenteredCare/Pages/AlwaysEvents.aspx), patient and family advisors, staff, and providers at Anne Arundel developed the SMART discharge protocol, which includes a simple 5-item checklist that is reviewed and discussed with the patient and family prior to discharge. SMART is an acronym for Signs, Medications, Appointments, Results, and Talk. In its work, the SMART team built on current evidence, created urgency and expectation for use with patients, families, and caregivers, disseminated findings, and promoted the protocol as a national standard. The tool is available at www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/SMARTDischargeProtocol.aspx.

According to Anne Arundel’s COO and CNO, Sherry Perkins, a critical part of the change process was to first understand staff’s fears and then learn what the evidence says. For example, with regard to the impact of additional family presence on infection control, they learned that family presence did not pose additional infection control concerns.

In 2009, there were no patient and family advisors volunteering at Anne Arundel. In 2014, there are approximately 80 advisors. Since 2009, the overall HCAHPS rating of the hospital has gone from 75.4% to 82% (the national average is 70%). While patient satisfaction scores have previously been in the top deciles at Anne Arundel, they have consistently risen since expanding family presence and implementing additional patient- and family-centered strategies.

Contra Costa Regional Medical Center and Health Centers

Contra Costa Health Services in Martinez, CA, includes Contra Costa Regional Medical Center and 10 health centers as part of a comprehensive county health system. Its 164-bed public hospital is dedicated to offering services that are welcoming, accessible, safe and respectful for everyone.

Like many hospitals in the country, for years Contra Costa Regional Medical Center restricted the hours when family members and loved ones could visit patients. However, the hospital’s medical staff often felt uncomfortable that they had to usher family and care partners away from patients when visiting hours were over. Anna Roth, Contra Costa’s CEO, recalls an incident that caused great anguish and contributed to the hospital’s decision to eliminate its restrictive visiting policy. A young boy whose grandfather was in the ICU was denied visitation. The grandfather, who had raised him, passed away, with the two having had no chance to say goodbye. Roth said that the incident hit home for her and the entire staff, and they knew they could do better. “Our old policies treated family members like visitors, until we realized that we are the visitors in people’s lives, not the other way around,” she noted.

In 2012, the hospital established an interdisciplinary team to transform its existing visiting policy into a “welcoming policy.” The team comprised the director of inpatient nursing, the chief of nursing, the chief of security, a public health program specialist, the facilities manager, and a patient partner. The new policy would support family presence 24/7 as well as change the concept of families as “visitors.”

Over the course of a year, the team designed the framework for a 3-day pilot and developed a check-in process to help loved ones gain access to patients after regular hospital hours. Working closely with nursing leadership, front-line staff, patient partners, and security, the team made necessary adjustments to the policy throughout the pilot period. The pilot was well-received and the policy was implemented soon after.

In the policy’s first year, more than 7000 family members and care partners were able to be with their loved ones between 8 pm and 6 am, the time period formerly restricted. The feedback from staff, patients and loved ones has been overwhelmingly positive. Front-line nurses are currently strengthening their skills and confidence in conducting change of shift report at bedside with patients and families. Other “welcoming” measures have also been implemented, including making signage more user-friendly, providing comfortable chairs to sleep in, and installing new vending machines with healthy snacks and drinks.

Vidant Health

Vidant Health serves 1.4 million people in a 29-county region of eastern North Carolina and comprises over 70 primary and specialty physician office practices, a 900-bed academic medical center, 7 community hospitals, an ambulatory surgery center, and home health and hospice services. Vidant Health’s efforts to advance a culture of patient- and family-centered care began in the late 1990s in the James and Connie Maynard Children’s Hospital and the regional rehabilitation center, but this culture did not spread consistently throughout Vidant Health, leading to differing experiences of care for patients and families.

The Vidant Health executive team and senior leaders heard about these inconsistencies firsthand in the spring of 2007 when an employee shared her family’s experiences during her brother’s ICU stay. Christie Odom described how the visitation policy restricted her family’s access to her brother to 15-minute increments, 6 times a day, which led to heightened fear and anxiety for her brother, family, and friends and impeded patient and family engagement in care and decision-making. Odom’s brother died alone with no family by his side. A physical therapist, Odom observed that in the regional rehabilitation center, families were partners in care, yet in the adult ICU, they were visitors.

After hearing Christie’s story, the system’s executive team, board of directors, and physician leaders made a commitment to eliminate these restrictive visitation guidelines. Leaders understood that this would require the organization’s culture to change from viewing patients and families as passive recipients of care to recognizing them as partners. Subsequently, the commitment to patient-family partnerships was imbedded in key documents including the corporation’s strategic and 5-year quality plans. An Office of Patient-Family Experience was established at Vidant Medical Center in 2008 and, a year later, a corporate office was established to guide system transformation. Emphasis was placed on building a solid team of patient-family advisors and staff champions. An initial focus was to replace the restrictive visitation policy with family presence guidelines. A key tenet of these guidelines is that patients define who their family members are and how they should be included in care and decision-making.

This policy and practice change provided the impetus for ongoing evolution of patient-family partnerships. Patient-family advisors are now integrated across the health care system. They serve on performance improvement teams, make safety rounds, serve as faculty in education programs, interview applicants for key positions, and develop and edit patient education materials. The outcomes achieved by this system transformation are evidenced in exceptional HCAHPS performance, significant reductions in serious safety events and hospital acquired infections and national recognition for commitment to patient-family partnerships.

Conclusion

Changing the concept of families as visitors to families as partners in care, according to patient preference, is foundational to advancing the practice of patient- and family-centered care and to building a safe, high-quality, cost-effective system of care. In 2009, Lucian Leape and colleagues envisioned a transformed health care culture in which “the family is respected as part of the care team—never visitors—in every area of the hospital, including the emergency department and the intensive care unit” [8]. A 2014 report by the National Patient Safety Foundation’s Lucian Leape Institute affirmed, “patients and families can play a critical role in preventing medical errors and reducing harm” [9].

Many hospitals still do not encourage family presence and participation and do not embrace the concept of families as true partners in care. But as demonstrated by the actions of the exemplar hospitals described here, it is possible to make this critical culture shift. The exemplar hospitals understand the importance of partnering with patients’ families instead of treating them as outsiders who are interfering in their loved one’s care. These hospitals are proving that giving patients the access they want to their loved ones actually helps themget better.

Through its campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families, IPFCC challenges hospitals across the United States and Canada to pledge to join this important initiative. Now is the time for all hospitals to embrace family presence and participation and to welcome families and other care partners 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Hospitals are invited to join this initiative. Steps to begin the change process may be found at www.ipfcc.org/advance/topics/better-together-pledge.html. Also available at IPFCC website is the Better Together toolkit, other materials and information that support the initiative, and a complete list of the exemplar hospitals and their processes and policies. The toolkit includes an organizational self-assessment, sample processes and policies, videos, and guides for families and staff to use in developing partnership. It is available at no charge at www.ipfcc.org/bettertogether/.

Corresponding author: Beverley H. Johnson, 6917 Arlington Rd., Ste. 309, Bethesda, MD 20814, bjohson@ipfcc.org.

Behind a Locked Door

This is our story as I remember it.

One day I came home from work, and my husband was confused. In all the years we’d been married, I’d never known him to be confused. He was sitting in the family room, and he looked frightened.

I said, “Bill, what’s going on?” He said, “Well, I was just going to get up and go look outside for Joey.” I said, “Bill, Joey’s not here.” He insisted, “Oh yes, we just came back from vacation. Joey just went outside, and I was going to check on him.”

I was alarmed and said, “Bill, I think you’re a little confused. I’m concerned because this morning you told me you had a headache. Maybe we should go to the hospital.” He resisted, but I simply told him, “Bill, if something was to happen to you, I might be held responsible because I didn’t do what was in your best interest. We can come home if everything is okay.”

And so we went to the emergency room, where we learned that my husband had a small bleed in his brain. We were told that we needed to go to another hospital that had a neurosurgeon on staff. My husband was transported by ambulance to a hospital about a mile away, and I followed him there in our car.

I want to stop here and tell you a bit about my husband and about myself. My name is Jackie Gruzenski, and I am a nurse involved in the field of psychiatric nursing. My husband’s name was Dr. William Gruzenski. He was a psychiatrist for forty years, and he was a chief medical officer for the last twelve years of his career.

Bill was a very good doctor and a very good husband. And toward the end of his life, he realized that all of his degrees, along with money and material possessions, didn’t matter. They were nothing. He just wanted to have me with him. We loved each other very deeply, and we wanted to share our last days and moments together, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

When we got to the second hospital, my husband was in the emergency room from about 7:00 p.m. until about 6:00 a.m. the next morning. At some point, he started to develop a hypertensive crisis, and the staff could not bring his blood pressure down. They started an IV medication, which required that he be monitored closely in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Of course, I went with him as he was transferred from emergency to ICU. When we got to the ICU door, I was told, “Now, just go into the waiting room. We’re going to settle your husband, and then we’ll come and get you.”

I was a nervous wreck while I waited. I knew my husband had been pretty sick while in emergency. What if he got more confused? What if he lost even this current level of functioning and wouldn’t

remember me? The longer I waited, the more my anxiety grew.

The waiting room was a small area, with chairs around the perimeter, except by the locked door. After an hour with no news, I saw a phone on the wall and called. I said to the voice on the other end, “My name is Mrs. Gruzenski. I was informed that my husband was going to be settled and that someone would come and get me.”

The next thing I knew a young, perky nurse came out, greeted me, and then directed me totally away from my husband, away from the door to the ICU, to a little room. She proceeded to give me the strict policies and procedures for the ICU, including that visitation was allowed only four times a day for thirty minutes each time.

Not believing what I was hearing, I said, “But my husband is going to be worried that I am not with him. We are the center of each other’s lives—we are only apart when we are at work!” Her response was, “Well, you can’t be with him. Those are the rules.”

I lived ten miles away. What was I supposed to do between these widely spaced thirty-minute visits? I felt I had to play by the rules. I was afraid that if I questioned too much or was abrupt with someone, they would treat my husband meanly. And because he was behind a locked door, I would never know.

I didn’t know what else to do and so, shortly before 8:00 a.m., I went home to get some rest. Ironically, just after I got home and started to settle after our long night in the ER, I got a flurry of calls from different residents who wanted information about my husband. They never said, “Come over and visit. He’s missing you.” They called because they needed the information I could give them, but they kept me locked out.

When I was able to have my first visit the next day, my husband asked where I had been. I explained that there were very limited visiting hours. This prompted my husband to speak to his nurse and say, “You know, she’s not a visitor. She’s my wife!” But he was informed that didn’t matter, that there were rules, and that I was a visitor and had to be treated as a visitor.

The rule trumped both of us and what we wanted. The rule meant he had to suffer alone. This was an accredited hospital, but in my view it was archaic. Staff hid behind the rules rather than using their heads and their hearts.

Over the next few days, I saw that my not being there with my husband was leading to more and more distress for him. As he became more ill, he would not allow the nurses to wash him, and he would not eat their food. He was doing everything he could do to get the staff’s attention to revisit the visiting restrictions. If I’d been allowed to stay, I’m sure I could have helped with feeding, with bathing, and with toileting. I’m certain I could have calmed him and helped lower his blood pressure.

I was treated as though I was an enemy, but all I wanted was to be with him, to share the last days of his life. I had always been his anchor. I was the person who navigated the everyday waters of his life. The hospital’s rules meant that he was adrift, and I was lost.

During his hospitalization, he was not afforded the respect he had given to all his patients and the nurses and doctors he had worked with each day. For example, the ICU staff never asked him how he would like to be addressed. They called him “Bill” when he should have been addressed as “Doctor Gruzenski.” He wouldn’t have thought of calling a resident by his first name, and there were only a few people in his life, his inner circle of family and friends, who called him “Bill.”

One day, I actually witnessed one doctor refer to my husband not even as “Bill” but as “Billy.”

I followed this doctor out of the ICU and challenged him saying “Would you think you were valued as a medical professional, and that your life had meant something if, in forty years’ time, someone called you ‘Billy’? ‘Billy’ is what you call some young boy you like, not someone who is sixty-eight years old and is a dignified gentleman and physician.”

My husband earned the title of “Doctor.” He attended four years of medical school, one year of internship, four years as a resident psychiatrist, and he was board certified in psychiatry. He had earned respect by exceeding all the societal standards for being addressed as “Doctor.” These achievements should not be washed away once you are hospitalized. In fact, I believe my husband might have felt a little safer if he had been addressed as “Doctor.”

My husband was in the ICU for eight of the last sixteen days of his life, and there were lots of missed opportunities for us. He wanted me there more than I was allowed. We missed time together we could have had. I feel it was a very cruel thing that was done to us.

We both knew the gravity of his condition, and my husband wanted quality of life, not quantity. I was a large part of the quality he wanted, but I was locked out for the greater part of his last days.

After my husband died, I felt I had to do something so that what happened to us wouldn’t happen to anyone else. I wrote letters to the chief executive officer of the hospital. I wrote to the chief of the medical staff. I wrote to the chief of nursing. And I wrote to the chaplain. The only person I ever heard from was the chaplain. No one apologized or said they would change the rules.

I believe more harm comes when family are not actively involved, and research is proving my belief is sound. And so I will continue to tell my story. I hope that if I tell it enough times, maybe people who write the rules in hospitals will realize that loved ones are advocates, not visitors.

I will never stop advocating for the elimination of visiting hours.

Reprinted from Crocker L, Johnson B. Privileged presence. Personal stories of connections in health care. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Bull Publishing; 2014.

1. American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Practice alert: Family presence: Visitation in the adult ICU. Accessed at www.aacn.org/WD/practice/docs/practicealerts/family-visitation-adult-icu-practicealert.pdf.

2. New Yorkers for Patient & Family Empowerment and the New York Public Interest Research Group. Sick, scared and separated from loved ones: A report on NYS hospital visiting policies and how patient-centered approaches can promote wellness and safer healthcare. August 2012. Accessed at www.patientandfamily/default.html.

3. Liu V, Read JL, Scruth E, Cheng E. Visitation policies and practices in US ICUs. Crit Care 2013;17:R71.

4. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Facts and figures about family presence and participation. Accessed at www.ipfcc.org/advance/topics/Better-Together-Facts-and-Figures.pdf.

5. Better together: partnering with families. Changing the concept of families as visitors bibliography. Accessed at www.ipfcc.org/advance/topics/Changing-the-Concept-of-Families-as-Visitors-Bibliography.pdf.

6. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Accessed at www.ipfcc.org/about/index.html.

7. Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Better together: Partnering with families. Accessed at www.ipfcc.org/advance/topics/better-together.html.

8. Leape L, Berwick D, Clancy C, et al; Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation. Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:424–8.

9. The National Patient Safety Foundation’s Lucien Leape Institute. Safety is personal: Partnering with patients and families for the safest care. Report of the Roundtable on Consumer Engagement in Patient Safety. Boston: National Patient Safety Foundation; 2014.

From the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care, Bethesda, MD (Ms. Dokken, Ms. Kaufman, and Ms. Johnson), Anne Arundel Medical Center, Annapolis, MD (Dr. Perkins), Contra Costa Regional Medical Center & Health Centers, Martinez, CA (Ms. Benepal, Ms. Roth, and Vidant Health, Greenville, NC (Ms. Dutton and Ms. Jones).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a campaign to eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies and to put in place policies that recognize families as partners in care.

- Methods: Descriptive report.

- Results: Many hospitals still have “visiting” hours that limit family presence, often counter to patient preferences. To change the concept of families as visitors and eliminate restrictive hospital visiting policies, the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families, calling on all hospitals to welcome families 24 hours a day and transform their policies and approaches to care so that patients’ families and loved ones are included in care and decision making, according to patient preferences. As part of the campaign, IPFCC recognized 12 hospitals that exemplify success in eliminating restrictive visiting policies and have changed the concept of families from “visitors” to partners. Leaders at these hospitals attest to the benefits of the changes through improved experience of care and other outcomes. Three exemplar hospitals are highlighted in this article and share their processes of change as well as key learnings and outcomes.

- Conclusion: Hospital policies and practices that encourage and support families as partners in care are essential to patients’ health, well-being, and safety.

Many families are restricted from the bedsides of loved ones because of hospital visiting policies [1–3]. Restrictive policies are often based on long-held beliefs that the presence and participation of families interferes with care, exhausts patients, is a burden to families, spreads infection, or violates HIPAA. However, there is no evidence to support those beliefs. In fact, isolating patients at their most vulnerable time from the people who know them best places them at risk for medical error, emotional harm, inconsistencies in care, and lack of preparedness for transitions in care [4,5]. Jackie Gruzenski’s story “Behind a Locked Door” (printed below) affectingly describes the impact of restrictive policies on a couple's last days.

Fortunately, a growing number of hospitals are lifting these restrictions. But opening the door is not enough. Hospitals need to change the concept of families as “visitors” to families as partners in care. Changing policies is a foundational step in creating a patient- and family-centered culture where families are recognized as essential to patients’ health and well-being and where they are respected as allies for quality and safety.

In response to this critical need for change, in June 2014 the Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) launched the campaign Better Together: Partnering with Families. IPFCC, founded in 1992, is a nonprofit organization that provides essential leadership to advance the understanding and practice of patient- and family-centered care [6]. Emphasizing the importance of family presence and participation to quality and safety, the campaign seeks to eliminate restrictive “visiting” policies and calls upon hospitals to include families as members of the care team and to welcome them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, according to patient preference [7]. The goal of the campaign is to change visiting policies in 1000 hospitals by 2017. Partnering with IPFCC in this initiative are the American Society for Healthcare Risk Management, American Association of Critical Care Nurses, National Partnership for Women & Families, New Yorkers for Patient and Family Empowerment, Health In Aging Foundation, and the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement.

Anne Arundel Medical Center

A regional not-for-profit hospital founded in 1902, Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis, MD, provides acute inpatient and outpatient care to residents of 4 counties in Maryland. A 380-bed facility, Anne Arundel has a cancer institute, heart and vascular institute, joint center, spine center, and a women’s and children’s center. In April 2011, the hospital completed a $424 million expansion project, which included a pediatric emergency room, an expanded general emergency room, 50 new patient beds, and 8 new operating rooms.

In 2010, based on a desire to concretely implement the principles of patient- and family-centered care, leaders at Anne Arundel began working with patient and family advisors and initiated a process to change the hospital’s restrictive visiting policy. Now, there are no restrictions on family presence anywhere in the hospital, from ICUs to medical/surgical units to other clinical areas. Patients have the power to choose who they want to stay with them—24 hours a day, 7 days a week. According to Anne Arundel’s policy, each patient determines who is defined as “family.” A “Revisiting Visiting” task force, comprising support staff, providers, and patient and family advisors, worked for 9 months to develop the new family presence policy and support its implementation.

With Anne Arundel leadership encouragement and support, patient and family advisors participated in all phases of the development and implementation of the new family presence policy and in other ways to advance the practice of patient- and family-centered care. The advisors also participated in the process to change the way nurse change of shift report was conducted, and they made recommendations for changes in the directional signs throughout the hospital. New signs, featuring a pineapple (a symbol of hospitality) and the words “Welcome Families” replaced old ones displaying the former restrictive visiting policy.