User login

What Would I Tell My Intern-Year Self?

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

The training path to dermatology can seem interminable. From getting good grades in college to seeking out the “right” extracurricular activities and cramming for the MCAT, just getting into medical school was a huge challenge. In medical school, you may recognize the same chaos as you begin to prepare for US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1, try to volunteer, and publish original research. Dermatology is undeniably a competitive specialty. The 2018 data released by the National Resident Match Program (also called The Match) showed that only 83% of 412 US seniors who applied were matched to dermatology.1 The average Step 1 score for those who matched was 249 versus 241 for those who did not match. In addition, they had an average of 5.2 research experiences, 9.1 volunteer experiences, and 49.1 were members of Alpha Omega Alpha.1

After studying and working to meet these targets, it is not surprising that the transition to residency is a big change. As a dermatology preliminary intern, or“prelim,” our experience differs compared to other specialties, as other interns are jumping into their area of practice right away.

During my intern year, I had a tremendous amount of anxiety about 2 things: (1) being a subpar medical intern and (2) being unprepared for the beginning of my dermatology residency. This anxiety drove me to read a tremendous amount of medical and dermatological literature in an effort to do everything. Although hindsight is always 20/20, I will share some thoughts of my own as well as some from friends and colleagues.

First, enjoy intern year. I know that may sound ridiculous, but there were many aspects of intern year that I loved! When your pager beeps, it’s for YOU! You are no longer a subintern, running every decision past your intern or explaining your student status to the patients! Proudly introduce yourself as Dr. So-and-So. You earned it! I loved the camaraderie of working with my co-interns and senior residents. Going through the challenges of intern year together is a deep bonding experience, and I absolutely made lifelong friendships. It also does not hurt that I met my boyfriend (now husband), which has changed my life in a big way.

When it comes to learning internal medicine, pediatrics, or surgery (depending on your intern year), prepare for rounds, read about your patients, and pay attention in Grand Rounds. You can even consider taking the dermatologic cases that may be on your team, just for fun. I am always grateful for my internal medicine knowledge when managing complex medical dermatology patients and rounding on our consultation service on the wards. However, do not burden yourself with excessive studying. Enjoy your time off: spend it with family and friends or rediscover a hobby that has been neglected while you have been working toward your achievements.

When it comes to learning dermatology, do not rush it! You have 3 years and a ton of studying ahead of you! You will learn all of it. When July 1 of your first year of dermatology finally starts, immerse yourself in this new world:

- Attend conferences. Even if they are on topics you might not be interested in—from cosmetics to psoriasis—they provide a real-world perspective and often have great lecturers sharing their knowledge.

- Get involved. There are many dermatologic societies to take part in, and dues are waived or reduced when you sign up as a resident. Many of them provide great resources from study materials to journals, and they are always a great way to network when there are events.

- Volunteer. Many of the dermatologic societies sponsor volunteer events such as skin cancer screenings. It can be a fun way to network while also giving back to the community.

- Spend time figuring out what you really enjoy. This step may seem self-evident, but after many years of fulfilling the necessary criteria to get into medical school and residency, it can be habitual to start fulfilling the same criteria all over again. Explore all aspects of dermatology and see what truly interests you. Consider how you expect your life after residency to be and think what learning opportunities might be helpful down the road. Reach out to attendings you would like to work with, both in dermatology and in other specialties. I personally enjoyed working in wound and oncology clinics, learning how other specialties approach clinical dilemmas that we see in dermatology.

As I embark on my final year of dermatology residency, I am truly grateful for the wisdom that has been shared with me on this journey. Many people have provided key pieces of information that have helped shape my training and my plans for the future, and I hope that sharing it will help others!

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

- National Resident Matching Program, Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors, 2018. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf. Accessed September 20, 2018.

Bedside Microscopy for the Beginner

Dermatologists are uniquely equipped amongst clinicians to make bedside diagnoses because of the focus on histopathology and microscopy inherent in our training. This skill is highly valuable in both an inpatient and outpatient setting because it may lead to a rapid diagnosis or be a useful adjunct in the initial clinical decision-making process. Although expert microscopists may be able to garner relevant information from scraping almost any type of lesion, bedside microscopy primarily is used by dermatologists in the United States for consideration of infectious etiologies of a variety of cutaneous manifestations.1,2

Basic Principles

Lesions that should be considered for bedside microscopic analysis in outpatient settings are scaly lesions, vesiculobullous lesions, inflammatory papules, and pustules1; microscopic evaluation also can be useful for myriad trichoscopic considerations.3,4 In some instances, direct visualization of the pathogen is possible (eg, cutaneous fungal infections, demodicidosis, scabetic infections), and in other circumstances reactive changes of keratinocytes or the presence of specific cell types can aid in diagnosis (eg, ballooning degeneration and multinucleation of keratinocytes in herpetic lesions, an abundance of eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum). Different types of media are used to best prepare tissue based on the suspected etiology of the condition.

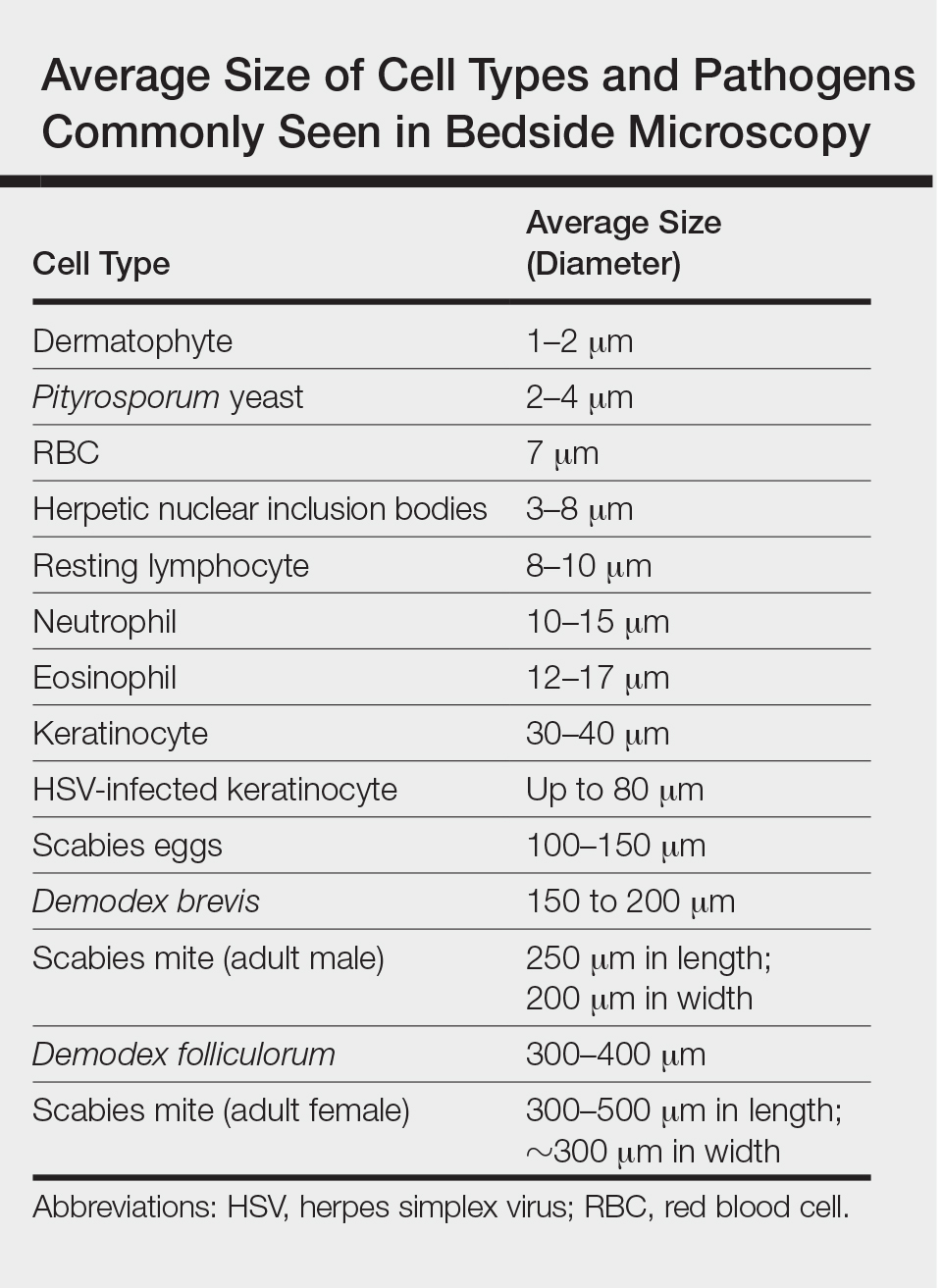

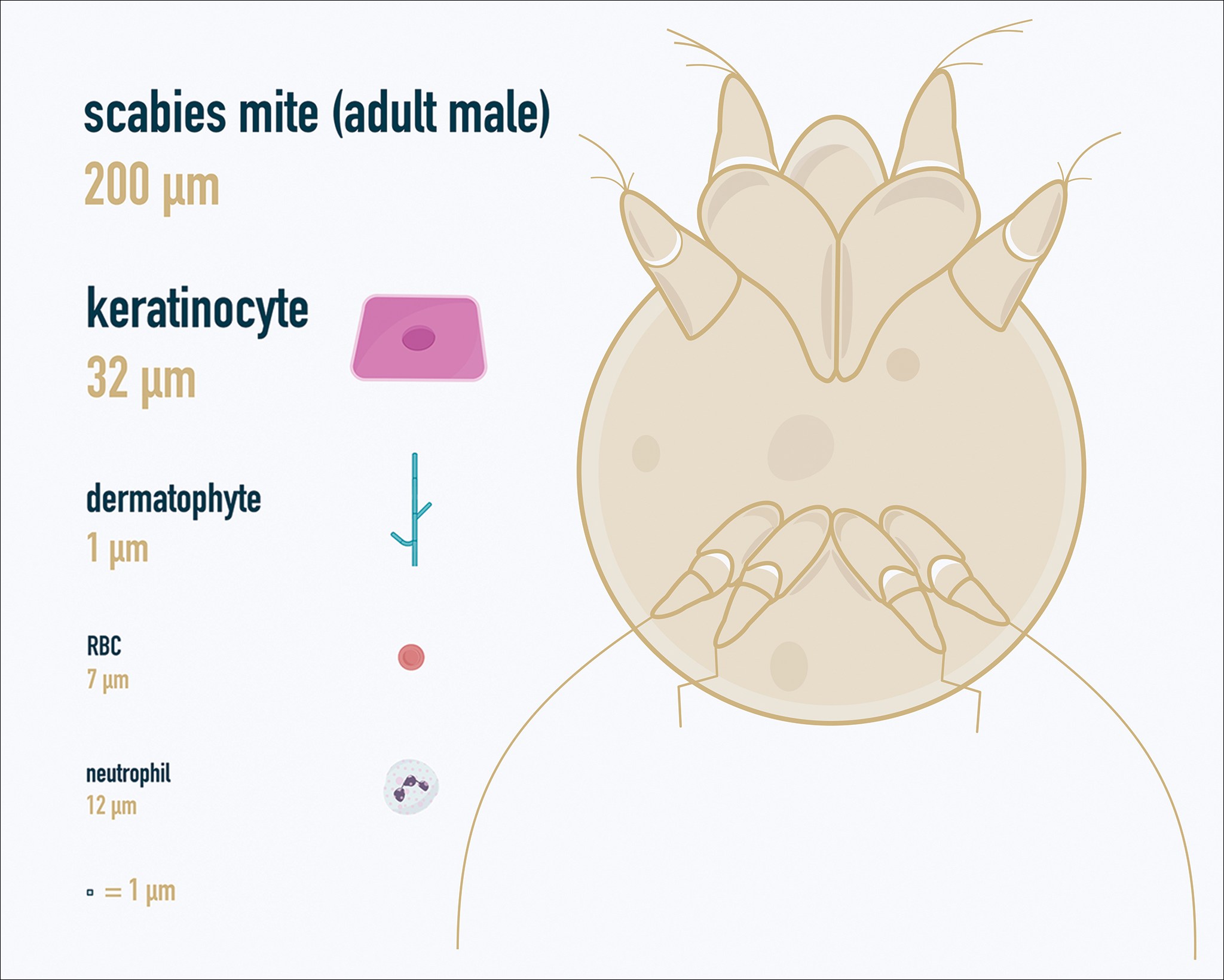

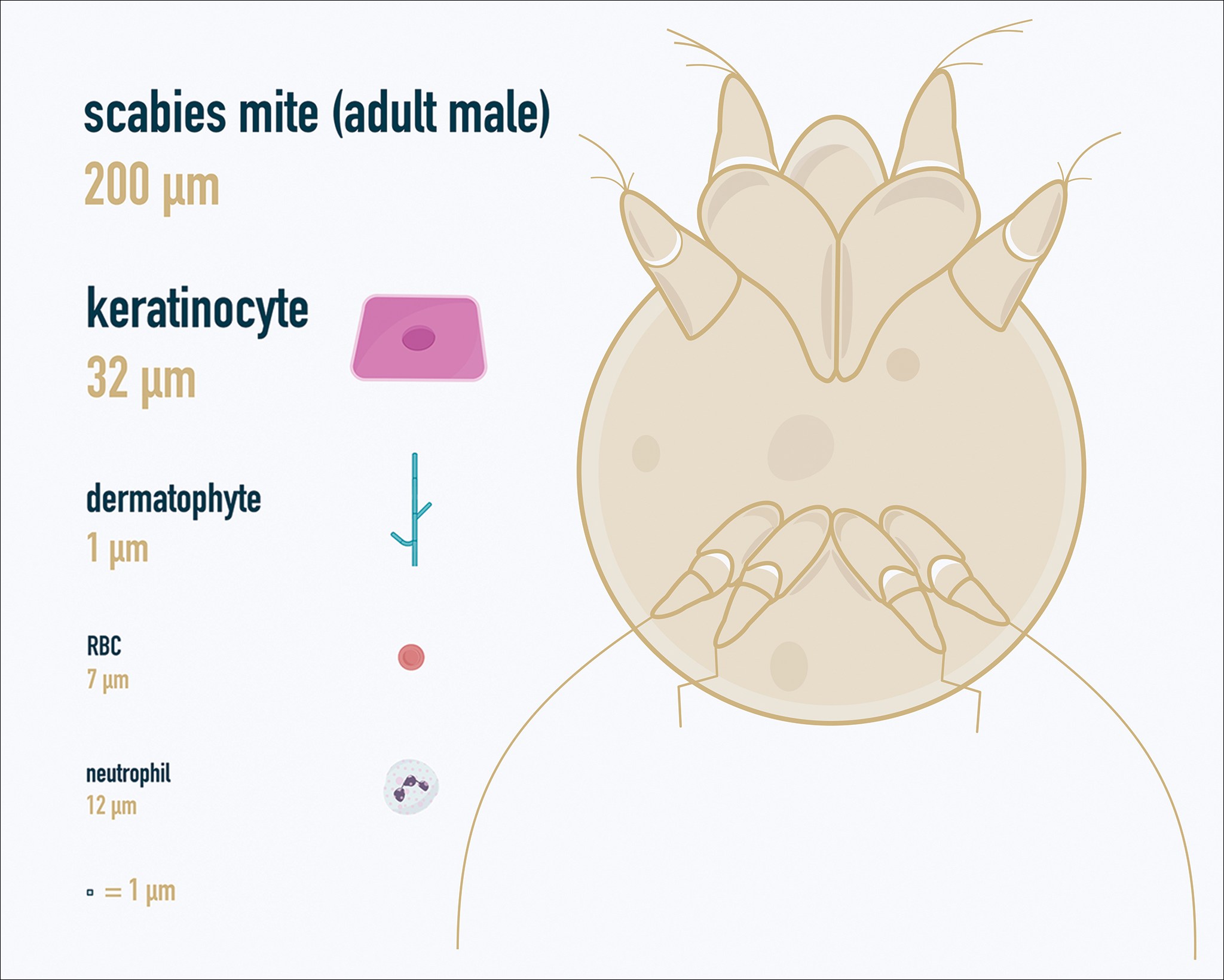

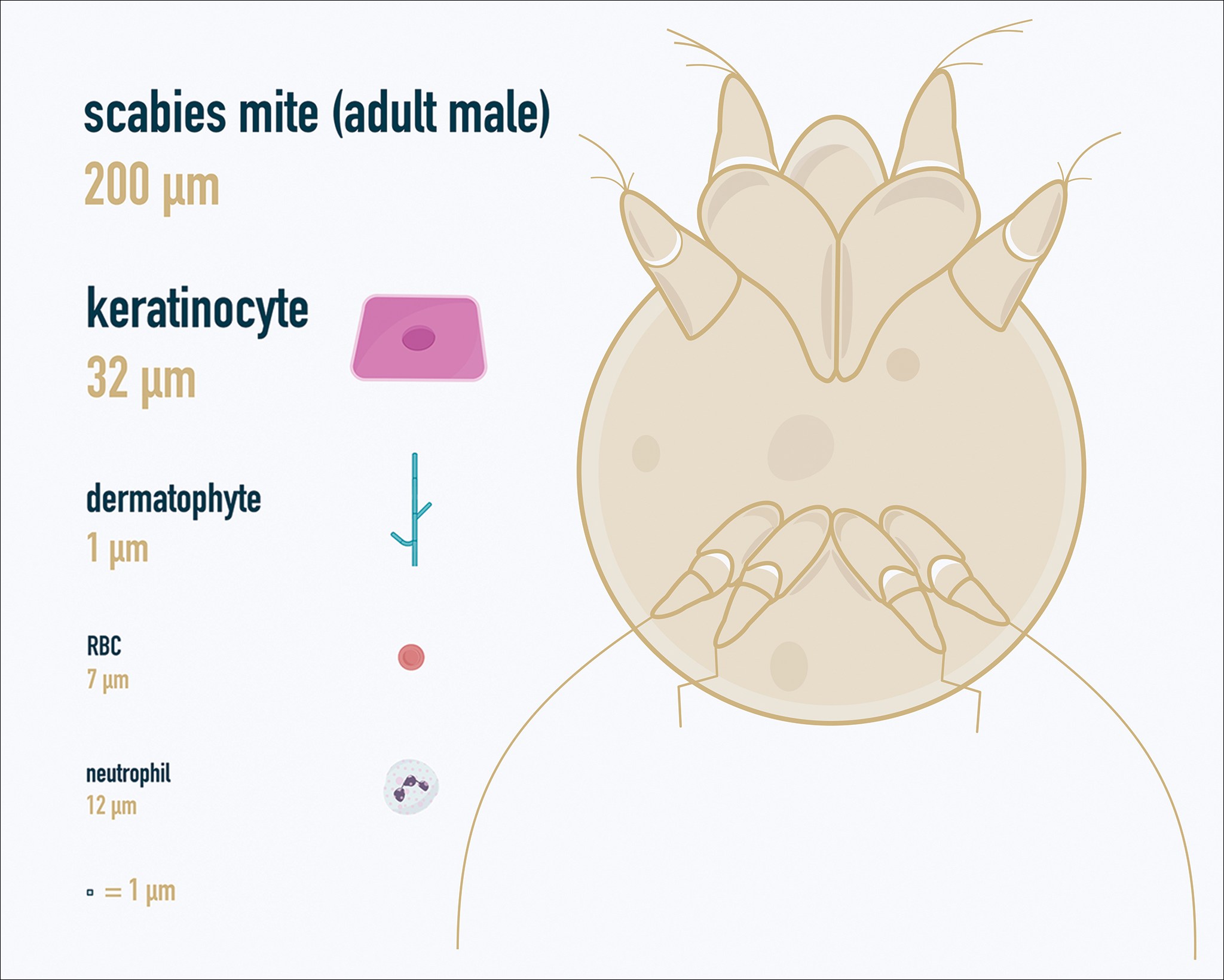

One major stumbling block for residents when beginning to perform bedside testing is the lack of dimensional understanding of the structures they are searching for; for example, medical students and residents often may mistake fibers for dermatophytes, which typically are much larger than fungal hyphae. Familiarizing oneself with the basic dimensions of different cell types or pathogens in relation to each other (Table) will help further refine the beginner’s ability to effectively search for and identify pathogenic features. This concept is further schematized in Figure 1 to help visualize scale differences.

Examination of the Specimen

Slide preparation depends on the primary lesion in consideration and will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections. Once the slide is prepared, place it on the microscope stage and adjust the condenser and light source for optimal visualization. Scan the specimen in a gridlike fashion on low power (usually ×10) and then inspect suspicious findings on higher power (×40 or higher).

Dermatomycoses

Fungal infections of the skin can present as annular papulosquamous lesions, follicular pustules or papules, bullous lesions, hypopigmented patches, and mucosal exudate or erosions, among other manifestations.5 Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is the classic medium used in preparation of lesions being assessed for evidence of fungus because it leads to lysis of keratinocytes for better visualization of fungal hyphae and spores. Other media that contain KOH and additional substrates such as dimethyl sulfoxide or chlorazol black E can be used to better highlight fungal elements.6

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytes lead to superficial infection of the epidermis and epidermal appendages and present in a variety of ways, including site-specific infections manifesting typically as erythematous, annular or arcuate scaling (eg, tinea faciei, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea manus, tinea pedis), alopecia with broken hair shafts, black dots, boggy nodules and/or scaling of the scalp (eg, tinea capitis, favus, kerion), and dystrophic nails (eg, onychomycosis).5,7 For examination of lesional skin scrapings, one can either use clear cellophane tape against the skin to remove scale, which is especially useful in the case of pediatric patients, and then press the tape against a slide prepared with several drops of a KOH-based medium to directly visualize without a coverslip, or scrape the lesion with a No. 15 blade and place the scales onto the glass slide, with further preparation as described below.8 For assessment of alopecia or dystrophic nails, scrape lesional skin with a No. 15 blade to obtain affected hair follicles and proximal subungual debris, respectively.6,9

Once the cellular debris has been obtained and placed on the slide, a coverslip can be overlaid and KOH applied laterally to be taken up across the slide by capillary action. Allow the slide to sit for at least 5 minutes before analyzing to better visualize fungal elements. Both tinea and onychomycosis will show branching septate hyphae extending across keratinocytes; a common false-positive is identifying overlapping keratinocyte edges, which are a similar size, but they can be distinguished from fungi because they do not cross multiple keratinocytes.1,8 Tinea capitis may demonstrate similar findings or may reveal hair shafts with spores contained within or surrounding it, corresponding to endothrix or ectothrix infection, respectively.5

Pityriasis Versicolor and Malassezia Folliculitis

Pityriasis versicolor presents with hypopigmented to pink, finely scaling ovoid papules, usually on the upper back, shoulders, and neck, and is caused by Malassezia furfur and other Malassezia species.5 Malassezia folliculitis also is caused by this fungus and presents with monomorphic follicular papules and pustules. Scrapings from the scaly papules will demonstrate keratinocytes with the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” fungal elements, whereas Malassezia folliculitis demonstrates only spores.5,7

Candidiasis

One possible outpatient presentation of candidiasis is oral thrush, which can exhibit white mucosal exudate or erythematous patches. A tongue blade can be used to scrape the tongue or cheek wall, with subsequent preparatory steps with application of KOH as described for dermatophytes. Cutaneous candidiasis most often develops in intertriginous regions and will exhibit erosive painful lesions with satellite pustules. In both cases, analysis of the specimen will show shorter fatter hyphal elements than seen in dermatophytosis, with pseudohyphae, blunted ends, and potentially yeast forms.5

Vesiculobullous Lesions

The Tzanck smear has been used since the 1940s to differentiate between etiologies of blistering disorders and is now most commonly used for the quick identification of herpetic lesions.1 The test is performed by scraping the base of a deroofed vesicle, pustule, or bulla, and smearing the cellular materials onto a glass slide. The most commonly utilized media for staining in the outpatient setting at my institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) is Giemsa, which is composed of azure II–eosin, glycerin, and methanol. It stains nuclei a reddish blue to pink and the cytoplasm blue.10 After being applied to the slide, the cells are allowed to air-dry for 5 to 10 minutes, and Giemsa stain is subsequently applied and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes, then rinsed carefully with water and directly examined.

Other stains that can be used to perform the Tzanck smear include commercial preparations that may be more accessible in the inpatient settings such as the Wright-Giemsa, Quik-Dip, and Diff-Quick.1,10

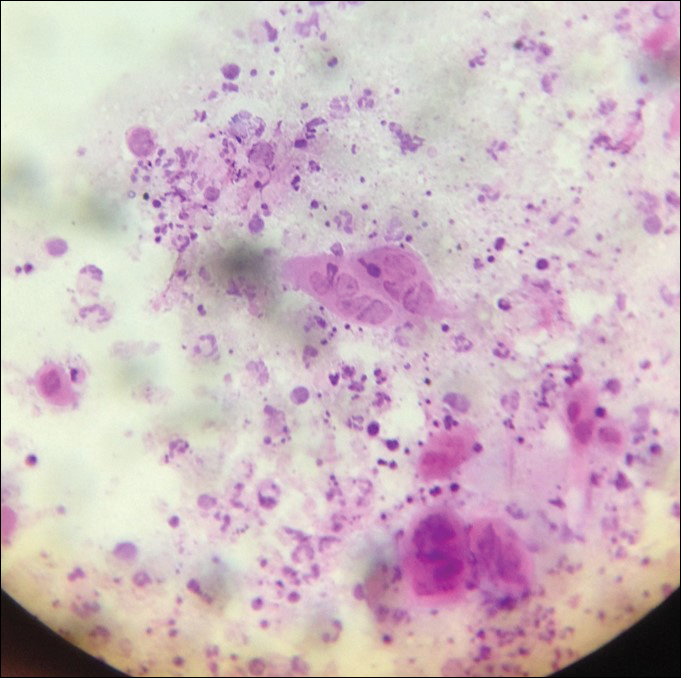

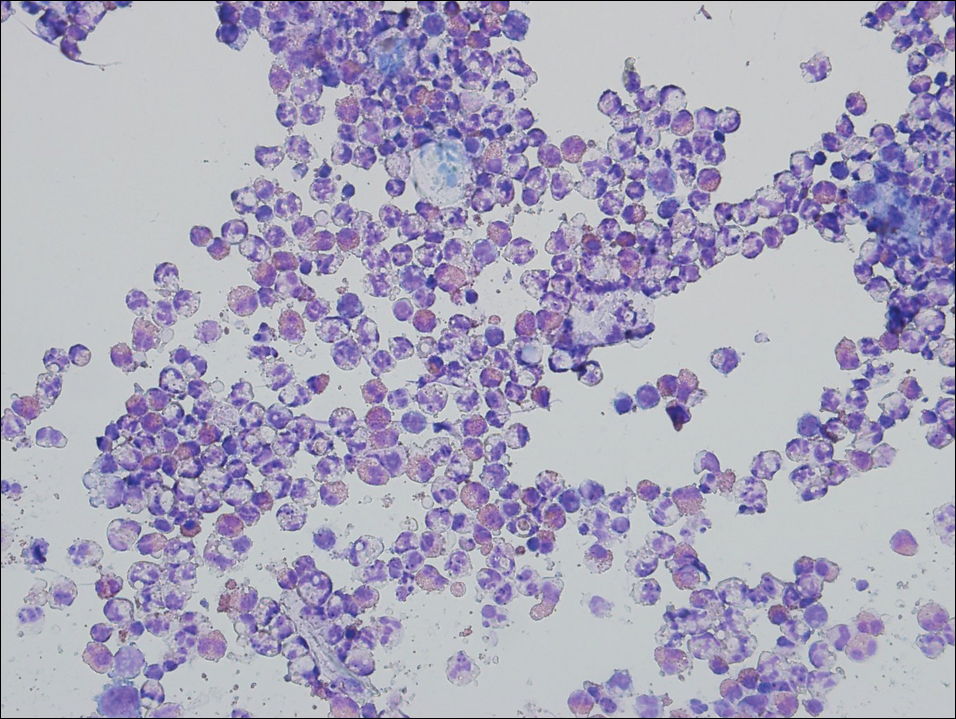

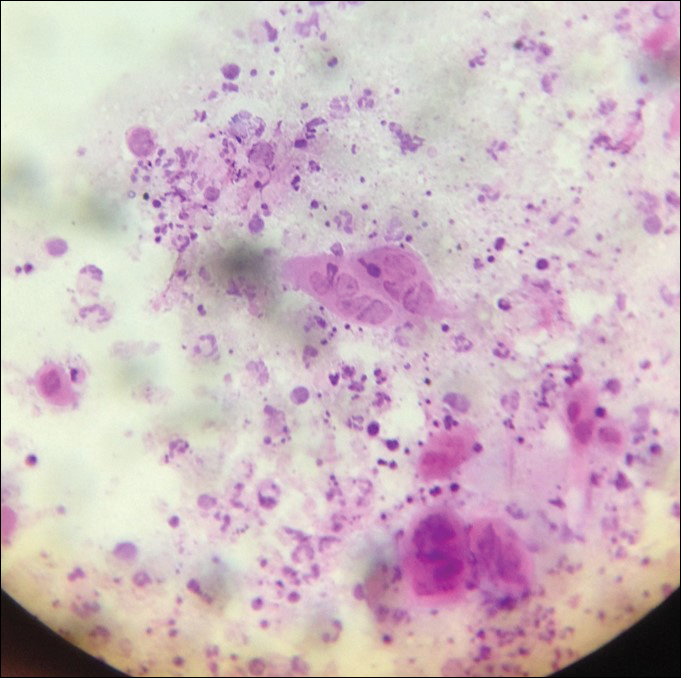

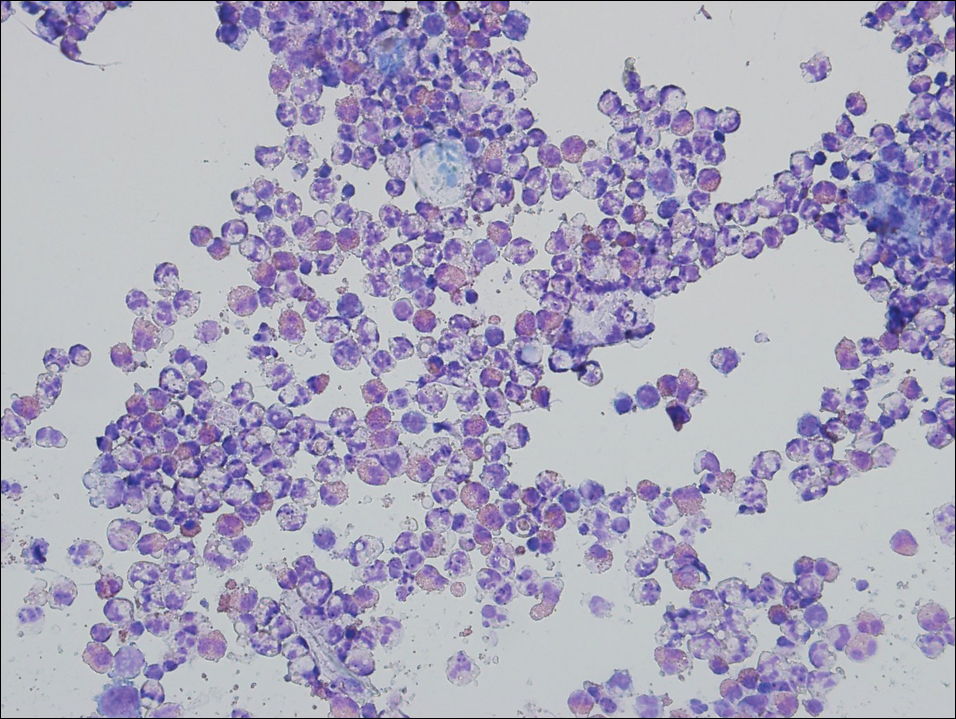

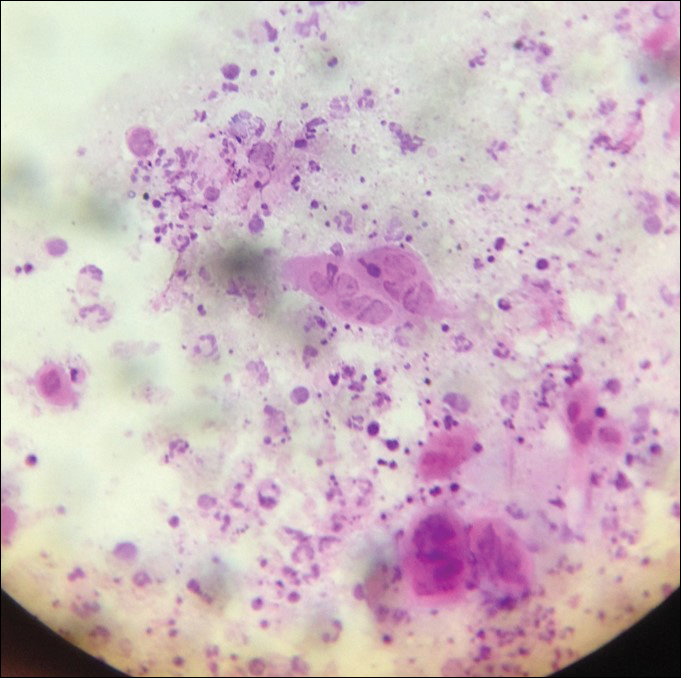

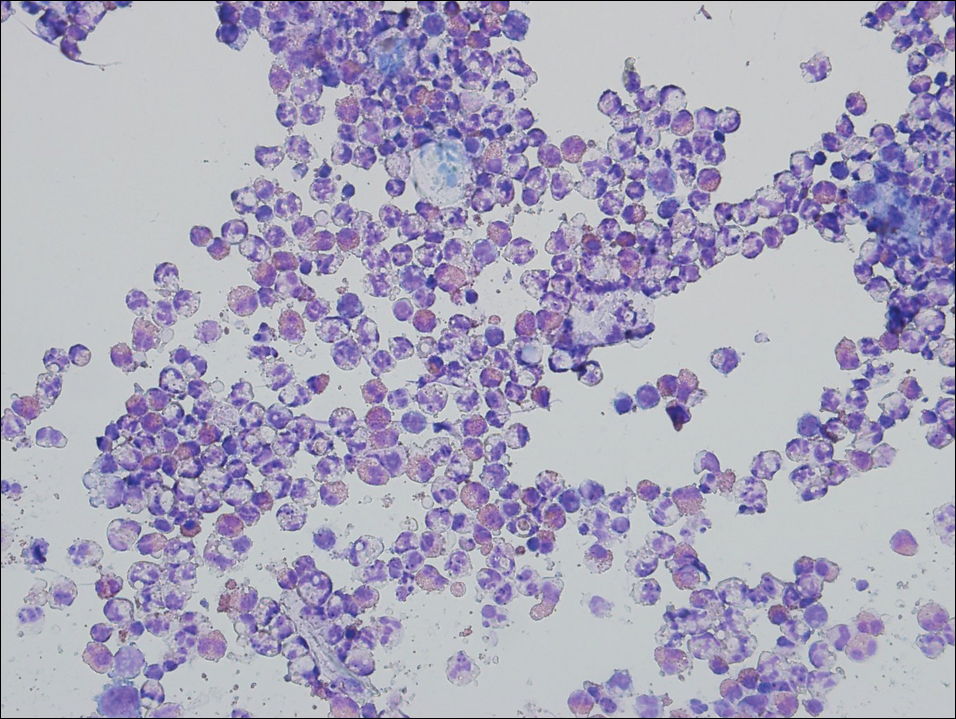

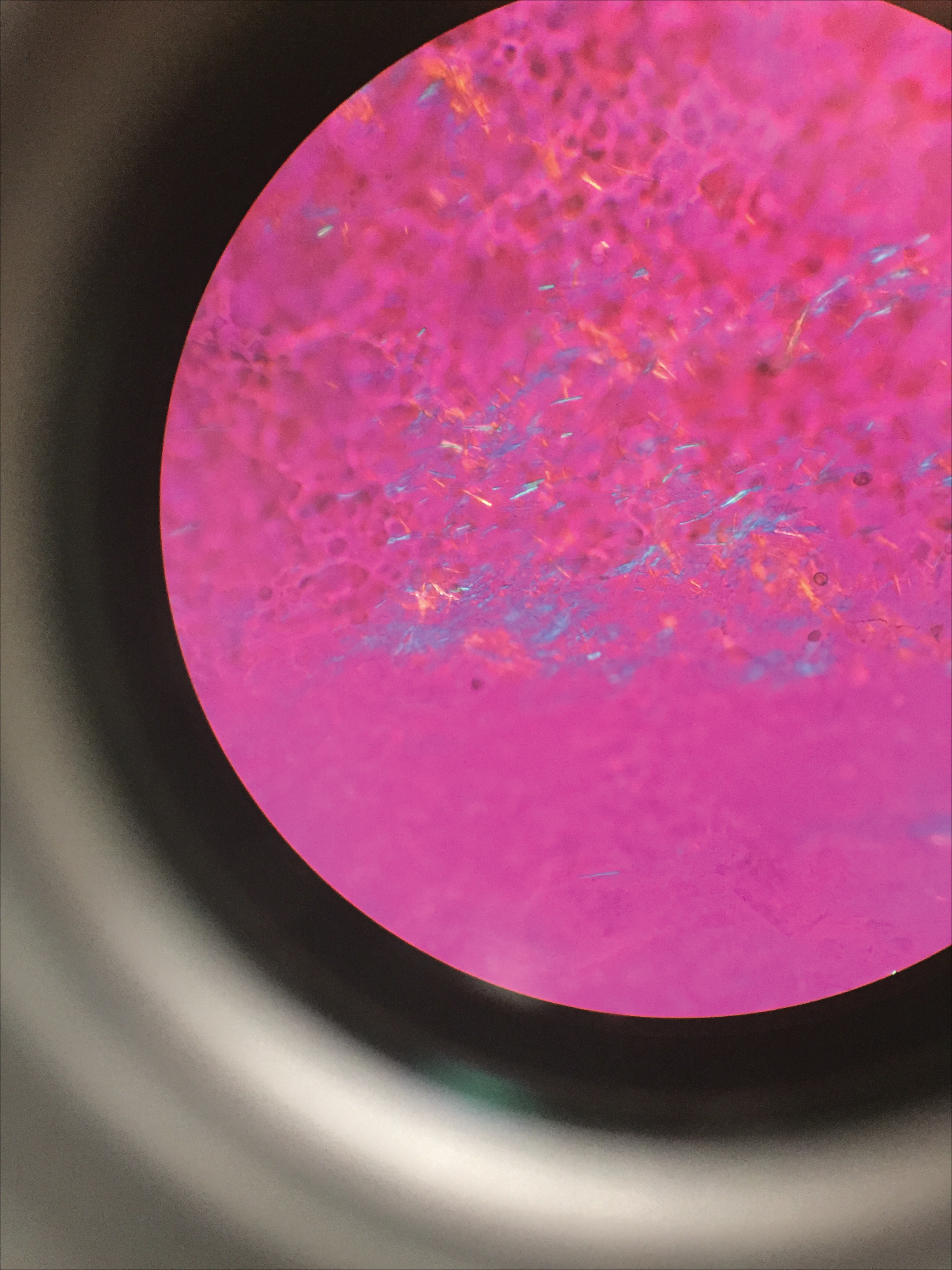

Examination of a Tzanck smear from a herpetic lesion will yield acantholytic, enlarged keratinocytes up to twice their usual size (referred to as ballooning degeneration), and multinucleation. In addition, molding of the nuclei to each other within the multinucleated cells and margination of the nuclear chromatin may be appreciated (Figure 2). Intranuclear inclusion bodies, also known as Cowdry type A bodies, can be seen that are nearly the size of red blood cells but are rare to find, with only 10% of specimens exhibiting this finding in a prospective review of 299 patients with herpetic vesiculobullous lesions.11 Evaluation of the contents of blisters caused by bullous pemphigoid and erythema toxicum neonatorum may yield high densities of eosinophils with normal keratinocyte morphology (Figure 3). Other blistering eruptions such as pemphigus vulgaris and bullous drug eruptions also have characteristic findings.1,2

Gout Preparation

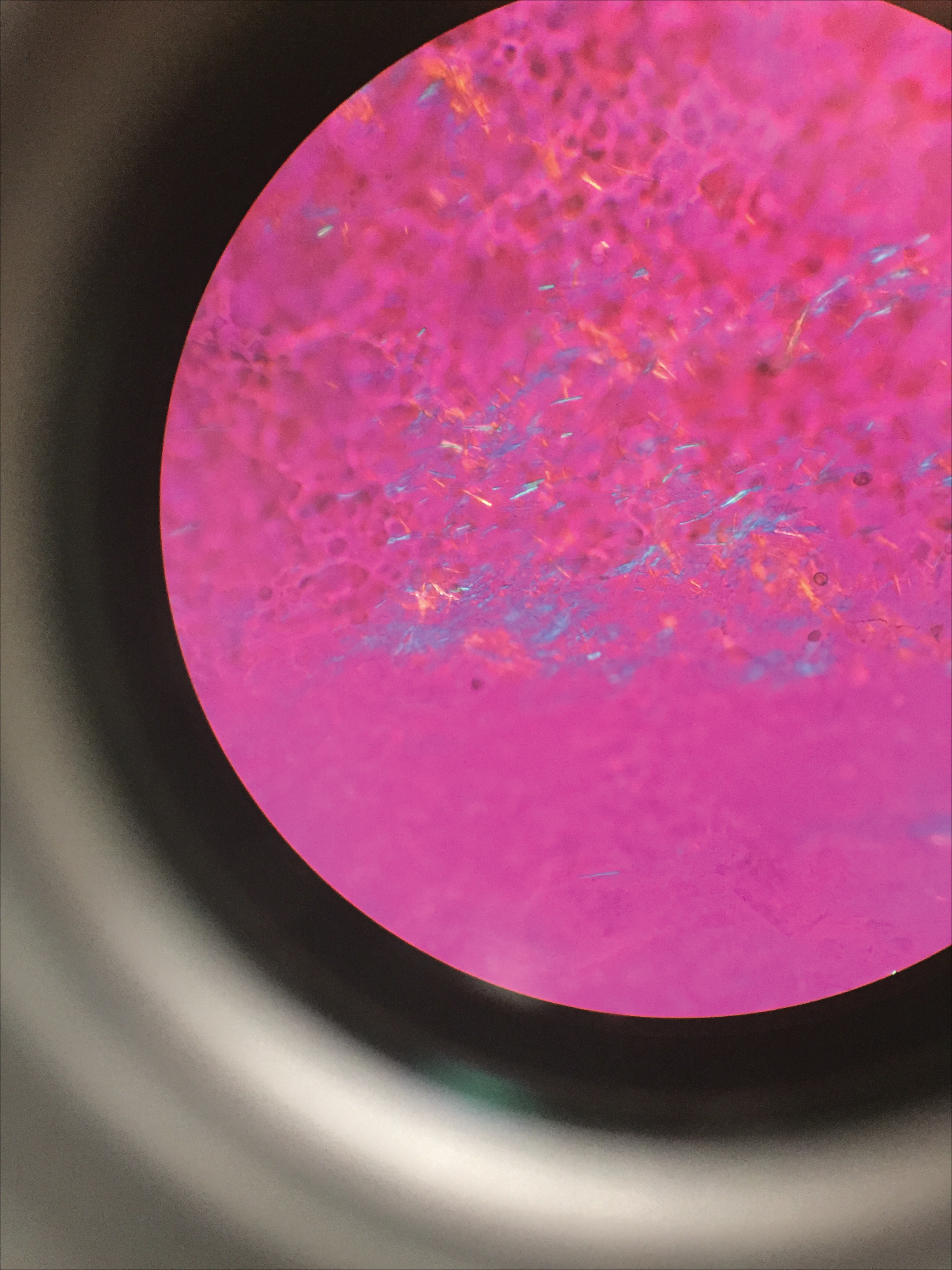

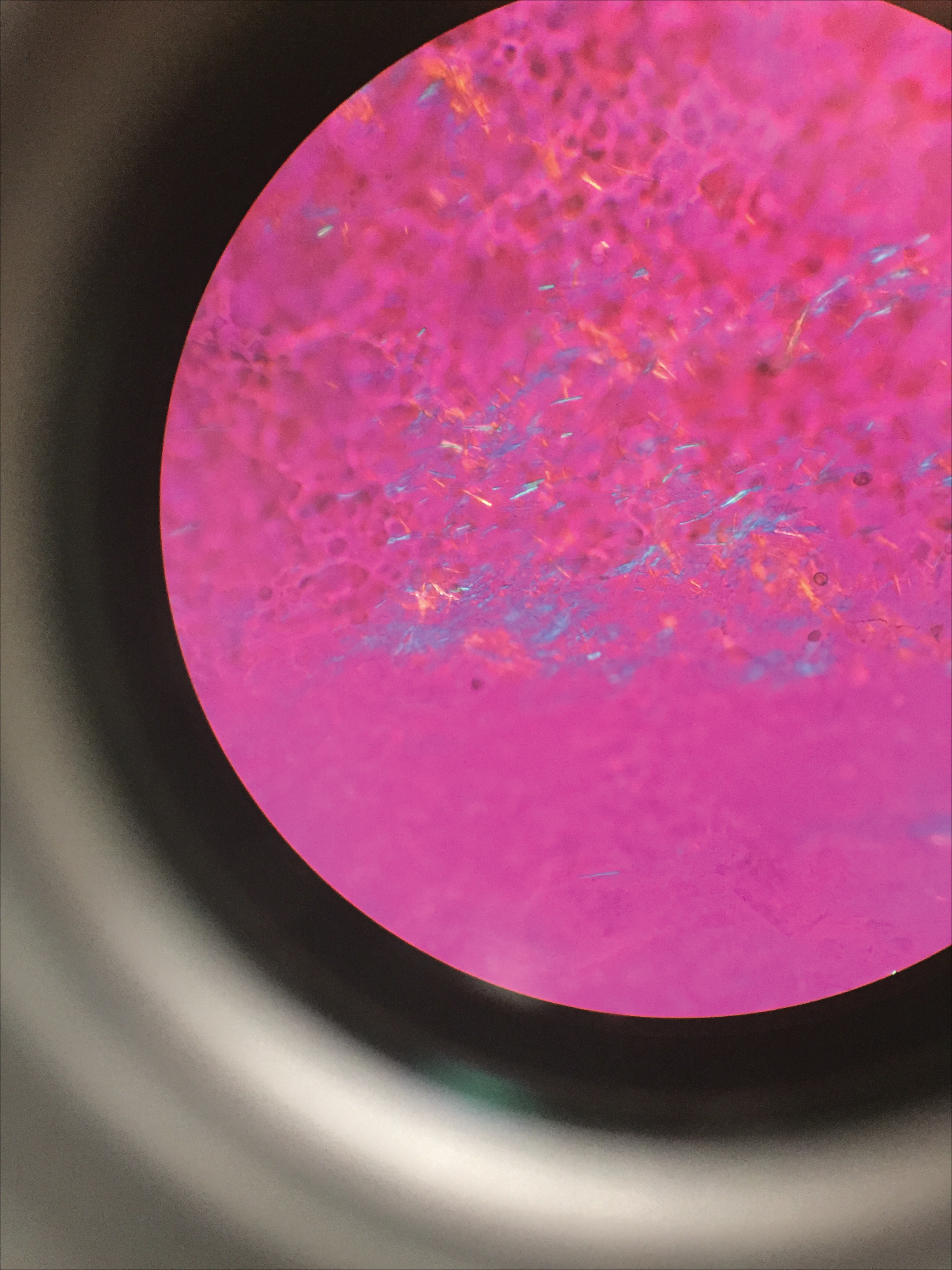

Gout is a systemic disease caused by uric acid accumulation that can present with joint pain and white to red nodules on digits, joints, and ears (known as tophi). Material may be expressed from tophi and examined immediately by polarized light microscopy to confirm the diagnosis.5 Specimens will demonstrate needle-shaped, negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals on polarized light microscopy (Figure 4). An ordinary light microscope can be converted for such use with the lenses of inexpensive polarized sunglasses, placing one lens between the light source and specimen and the other lens between the examiner’s eye and the specimen.12

Parasitic Infections

Two common parasitic infections identified in outpatient dermatology clinics are scabies mites and Demodex mites. Human scabies is extremely pruritic and caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis; the typical presentation in an adult is erythematous and crusted papules, linear burrows, and vesiculopustules, especially of the interdigital spaces, wrists, axillae, umbilicus, and genital region.1,13 Demodicidosis presents with papules and pustules on the face, usually in a patient with background rosacea and diffuse erythema.1,5,14

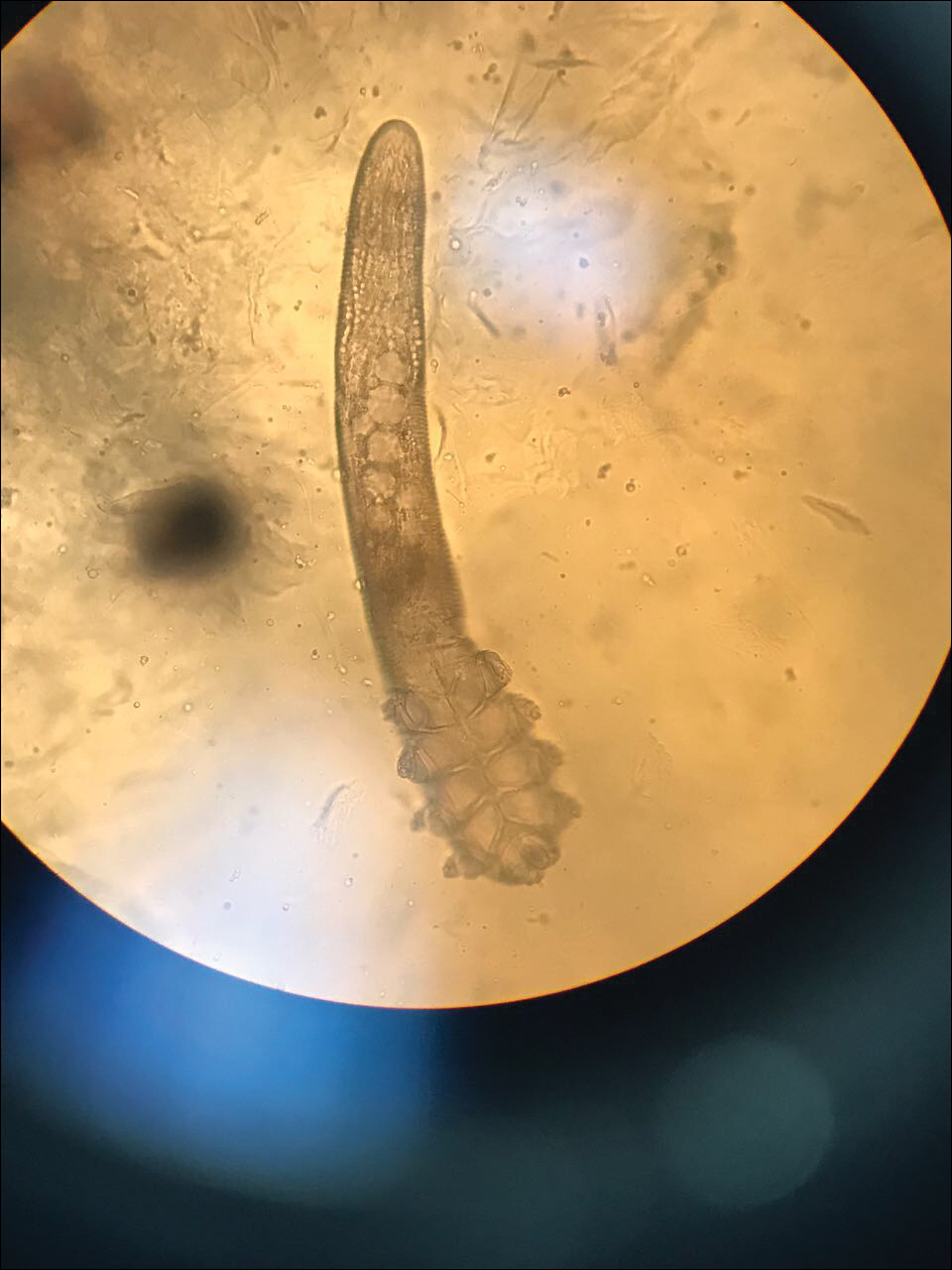

If either of these conditions are suspected, mineral oil should be used to prepare the slide because it will maintain viability of the organisms, which are visualized better in motion. Adult scabies mites are roughly 10 times larger than keratinocytes, measuring approximately 250 to 450 µm in length with 8 legs.13 Eggs also may be visualized within the cellular debris and typically are 100 to 150 µm in size and ovoid in shape. Of note, polariscopic examination may be a useful adjunct for evaluation of scabies because scabetic spines and scybala (or fecal material) are polarizable.15

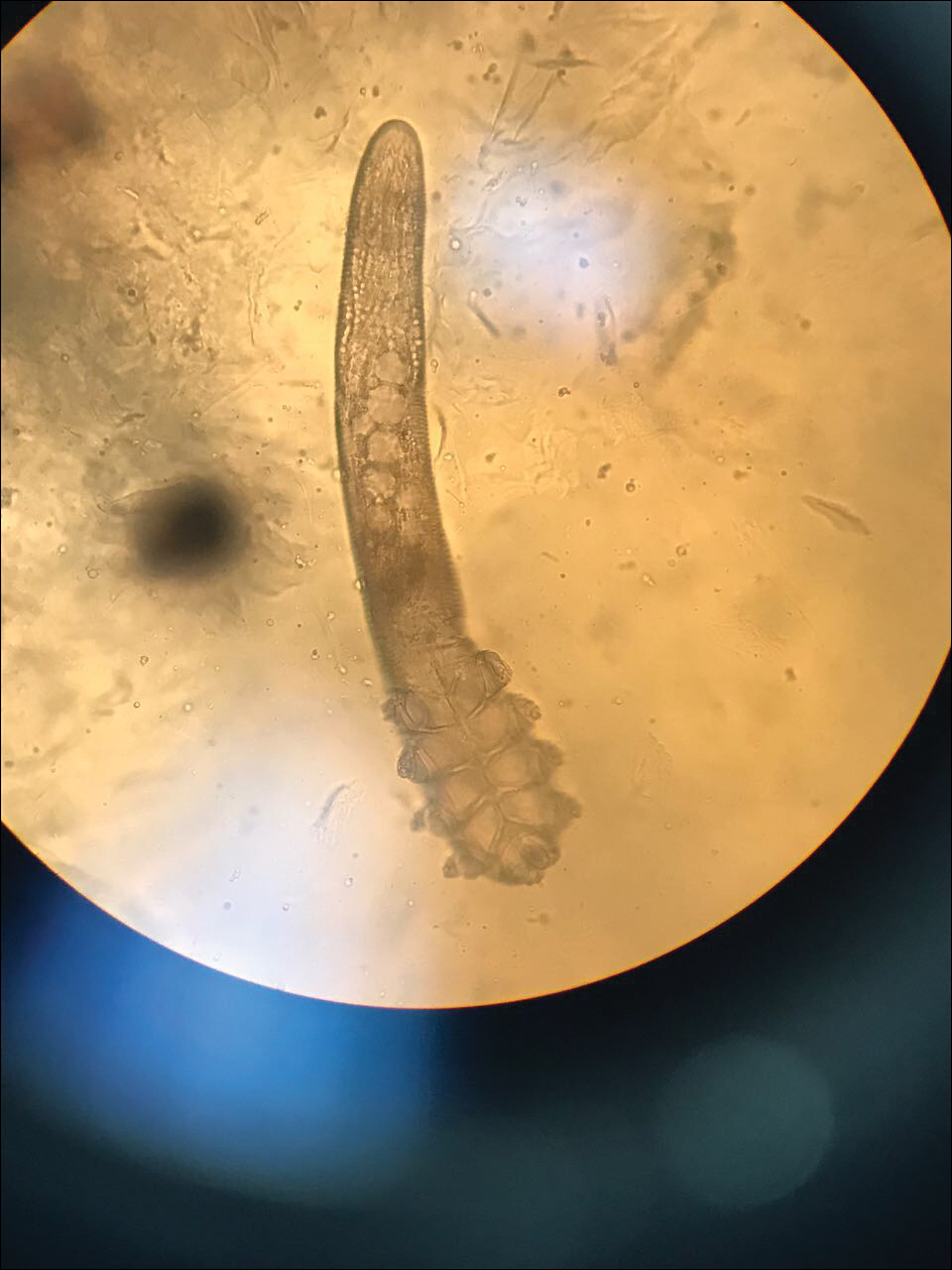

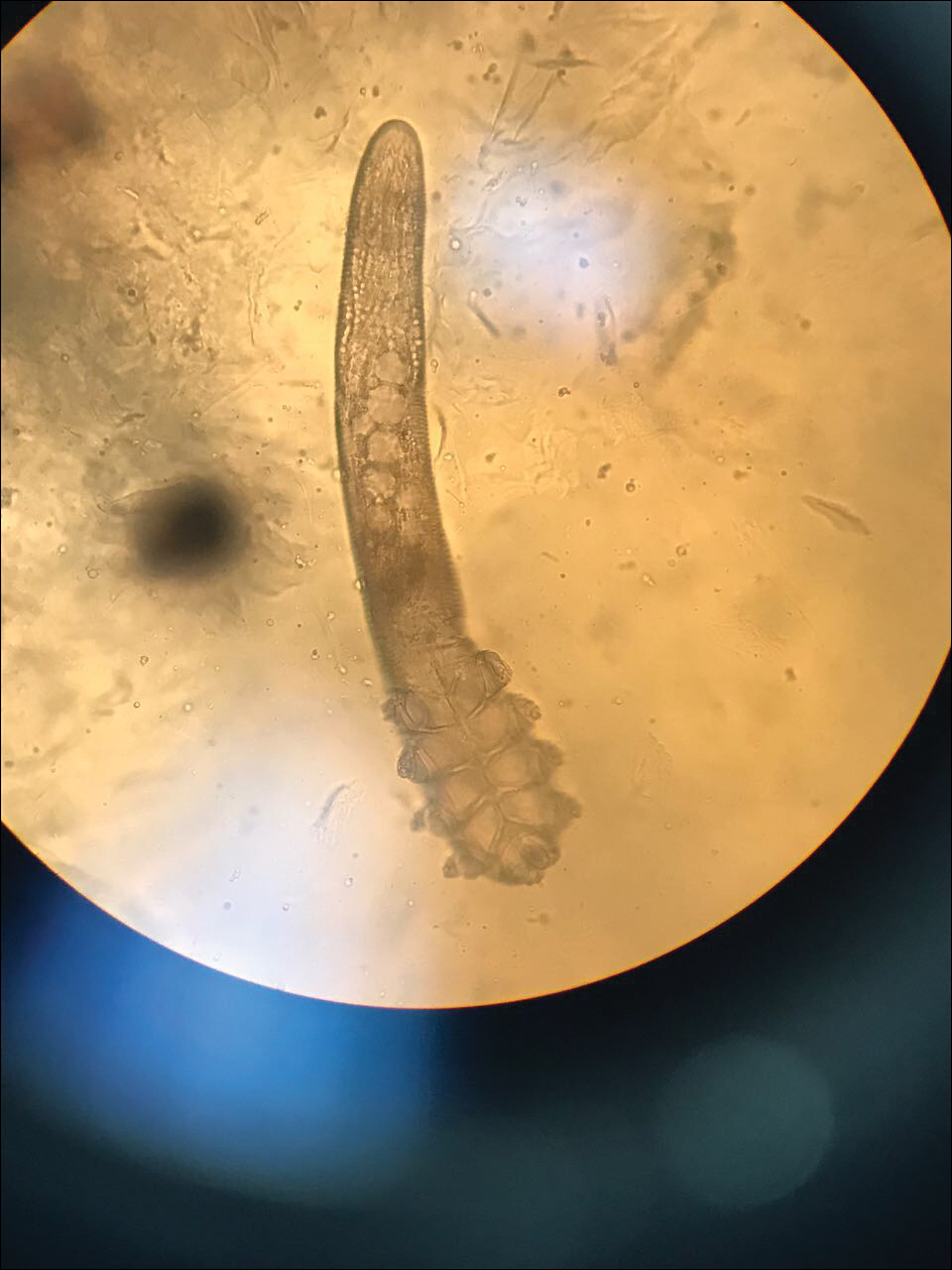

Two types of Demodex mites typically are found in the skin: Demodex folliculorum, which are similarly sized to scabies mites with a more oblong body and occur most commonly in mature hair follicles (eg, eyelashes), and Demodex brevis, which are about half the size (150–200 µm) and live in the sebaceous glands of vellus hairs (Figure 5).14 Both of these mites have 8 legs, similar to the scabies mite.

Hair Preparations

Hair preparations for bulbar examination (eg, trichogram) may prove useful in the evaluation of many types of alopecia, and elaboration on this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Microscopic evaluation of the hair shaft may be an underutilized technique in the outpatient setting and is capable of yielding a variety of diagnoses, including monilethrix, pili torti, and pili trianguli et canaliculi, among others.3 One particularly useful scenario for hair shaft examination (usually of the eyebrow) is in the setting of a patient with severe atopic dermatitis or a baby with ichthyosiform erythroderma, as discovery of trichorrhexis invaginata is pathognomonic for the diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.16 Lastly, evaluation of the hair shaft in patients with patchy and diffuse hair loss whose clinical impression is reminiscent of alopecia areata, or those with concerns of inability to grow hair beyond a short length, may lead to diagnosis of loose anagen syndrome, especially if more than 70% of hair fibers examined exhibit the classic findings of a ruffled proximal cuticle and lack of root sheath.4

Final Thoughts

Bedside microscopy is a rapid and cost-sensitive way to confirm diagnoses that are clinically suspected and remains a valuable tool to acquire during residency training.

- Wanat KA, Dominguez AR, Carter Z, et al. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:197-218.

- Micheletti RG, Dominguez AR, Wanat KA. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: parasitic and noninfectious diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:221-230.

- Whiting DA, Dy LC. Office diagnosis of hair shaft defects. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:24-34.

- Tosti A. Loose anagen hair syndrome and loose anagen hair. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:521-522.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:620-626.

- Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Raghukumar S, Ravikumar BC. Potassium hydroxide mount with cellophane adhesive: a method for direct diagnosis of dermatophyte skin infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.13573.

- Bhat YJ, Zeerak S, Kanth F, et al. Clinicoepidemiological and mycological study of tinea capitis in the pediatric population of Kashmir Valley: a study from a tertiary care centre. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:100-103.

- Gupta LK, Singhi MK. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295-299.

- Durdu M, Baba M, Seçkin D. The value of Tzanck smear test in diagnosis of erosive, vesicular, bullous, and pustular skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:958-964.

- Fagan TJ, Lidsky MD. Compensated polarized light microscopy using cellophane adhesive tape. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:256-262.

- Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:268-279.

- Desch C, Nutting WB. Demodex folliculorum (Simon) and D. brevis akbulatova of man: redescription and reevaluation. J Parasitol. 1972;58:169-177.

- Foo CW, Florell SR, Bowen AR. Polarizable elements in scabies infestation: a clue to diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:6-10.

- Akkurt ZM, Tuncel T, Ayhan E, et al. Rapid and easy diagnosis of Netherton syndrome with dermoscopy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:280-282.

Dermatologists are uniquely equipped amongst clinicians to make bedside diagnoses because of the focus on histopathology and microscopy inherent in our training. This skill is highly valuable in both an inpatient and outpatient setting because it may lead to a rapid diagnosis or be a useful adjunct in the initial clinical decision-making process. Although expert microscopists may be able to garner relevant information from scraping almost any type of lesion, bedside microscopy primarily is used by dermatologists in the United States for consideration of infectious etiologies of a variety of cutaneous manifestations.1,2

Basic Principles

Lesions that should be considered for bedside microscopic analysis in outpatient settings are scaly lesions, vesiculobullous lesions, inflammatory papules, and pustules1; microscopic evaluation also can be useful for myriad trichoscopic considerations.3,4 In some instances, direct visualization of the pathogen is possible (eg, cutaneous fungal infections, demodicidosis, scabetic infections), and in other circumstances reactive changes of keratinocytes or the presence of specific cell types can aid in diagnosis (eg, ballooning degeneration and multinucleation of keratinocytes in herpetic lesions, an abundance of eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum). Different types of media are used to best prepare tissue based on the suspected etiology of the condition.

One major stumbling block for residents when beginning to perform bedside testing is the lack of dimensional understanding of the structures they are searching for; for example, medical students and residents often may mistake fibers for dermatophytes, which typically are much larger than fungal hyphae. Familiarizing oneself with the basic dimensions of different cell types or pathogens in relation to each other (Table) will help further refine the beginner’s ability to effectively search for and identify pathogenic features. This concept is further schematized in Figure 1 to help visualize scale differences.

Examination of the Specimen

Slide preparation depends on the primary lesion in consideration and will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections. Once the slide is prepared, place it on the microscope stage and adjust the condenser and light source for optimal visualization. Scan the specimen in a gridlike fashion on low power (usually ×10) and then inspect suspicious findings on higher power (×40 or higher).

Dermatomycoses

Fungal infections of the skin can present as annular papulosquamous lesions, follicular pustules or papules, bullous lesions, hypopigmented patches, and mucosal exudate or erosions, among other manifestations.5 Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is the classic medium used in preparation of lesions being assessed for evidence of fungus because it leads to lysis of keratinocytes for better visualization of fungal hyphae and spores. Other media that contain KOH and additional substrates such as dimethyl sulfoxide or chlorazol black E can be used to better highlight fungal elements.6

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytes lead to superficial infection of the epidermis and epidermal appendages and present in a variety of ways, including site-specific infections manifesting typically as erythematous, annular or arcuate scaling (eg, tinea faciei, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea manus, tinea pedis), alopecia with broken hair shafts, black dots, boggy nodules and/or scaling of the scalp (eg, tinea capitis, favus, kerion), and dystrophic nails (eg, onychomycosis).5,7 For examination of lesional skin scrapings, one can either use clear cellophane tape against the skin to remove scale, which is especially useful in the case of pediatric patients, and then press the tape against a slide prepared with several drops of a KOH-based medium to directly visualize without a coverslip, or scrape the lesion with a No. 15 blade and place the scales onto the glass slide, with further preparation as described below.8 For assessment of alopecia or dystrophic nails, scrape lesional skin with a No. 15 blade to obtain affected hair follicles and proximal subungual debris, respectively.6,9

Once the cellular debris has been obtained and placed on the slide, a coverslip can be overlaid and KOH applied laterally to be taken up across the slide by capillary action. Allow the slide to sit for at least 5 minutes before analyzing to better visualize fungal elements. Both tinea and onychomycosis will show branching septate hyphae extending across keratinocytes; a common false-positive is identifying overlapping keratinocyte edges, which are a similar size, but they can be distinguished from fungi because they do not cross multiple keratinocytes.1,8 Tinea capitis may demonstrate similar findings or may reveal hair shafts with spores contained within or surrounding it, corresponding to endothrix or ectothrix infection, respectively.5

Pityriasis Versicolor and Malassezia Folliculitis

Pityriasis versicolor presents with hypopigmented to pink, finely scaling ovoid papules, usually on the upper back, shoulders, and neck, and is caused by Malassezia furfur and other Malassezia species.5 Malassezia folliculitis also is caused by this fungus and presents with monomorphic follicular papules and pustules. Scrapings from the scaly papules will demonstrate keratinocytes with the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” fungal elements, whereas Malassezia folliculitis demonstrates only spores.5,7

Candidiasis

One possible outpatient presentation of candidiasis is oral thrush, which can exhibit white mucosal exudate or erythematous patches. A tongue blade can be used to scrape the tongue or cheek wall, with subsequent preparatory steps with application of KOH as described for dermatophytes. Cutaneous candidiasis most often develops in intertriginous regions and will exhibit erosive painful lesions with satellite pustules. In both cases, analysis of the specimen will show shorter fatter hyphal elements than seen in dermatophytosis, with pseudohyphae, blunted ends, and potentially yeast forms.5

Vesiculobullous Lesions

The Tzanck smear has been used since the 1940s to differentiate between etiologies of blistering disorders and is now most commonly used for the quick identification of herpetic lesions.1 The test is performed by scraping the base of a deroofed vesicle, pustule, or bulla, and smearing the cellular materials onto a glass slide. The most commonly utilized media for staining in the outpatient setting at my institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) is Giemsa, which is composed of azure II–eosin, glycerin, and methanol. It stains nuclei a reddish blue to pink and the cytoplasm blue.10 After being applied to the slide, the cells are allowed to air-dry for 5 to 10 minutes, and Giemsa stain is subsequently applied and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes, then rinsed carefully with water and directly examined.

Other stains that can be used to perform the Tzanck smear include commercial preparations that may be more accessible in the inpatient settings such as the Wright-Giemsa, Quik-Dip, and Diff-Quick.1,10

Examination of a Tzanck smear from a herpetic lesion will yield acantholytic, enlarged keratinocytes up to twice their usual size (referred to as ballooning degeneration), and multinucleation. In addition, molding of the nuclei to each other within the multinucleated cells and margination of the nuclear chromatin may be appreciated (Figure 2). Intranuclear inclusion bodies, also known as Cowdry type A bodies, can be seen that are nearly the size of red blood cells but are rare to find, with only 10% of specimens exhibiting this finding in a prospective review of 299 patients with herpetic vesiculobullous lesions.11 Evaluation of the contents of blisters caused by bullous pemphigoid and erythema toxicum neonatorum may yield high densities of eosinophils with normal keratinocyte morphology (Figure 3). Other blistering eruptions such as pemphigus vulgaris and bullous drug eruptions also have characteristic findings.1,2

Gout Preparation

Gout is a systemic disease caused by uric acid accumulation that can present with joint pain and white to red nodules on digits, joints, and ears (known as tophi). Material may be expressed from tophi and examined immediately by polarized light microscopy to confirm the diagnosis.5 Specimens will demonstrate needle-shaped, negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals on polarized light microscopy (Figure 4). An ordinary light microscope can be converted for such use with the lenses of inexpensive polarized sunglasses, placing one lens between the light source and specimen and the other lens between the examiner’s eye and the specimen.12

Parasitic Infections

Two common parasitic infections identified in outpatient dermatology clinics are scabies mites and Demodex mites. Human scabies is extremely pruritic and caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis; the typical presentation in an adult is erythematous and crusted papules, linear burrows, and vesiculopustules, especially of the interdigital spaces, wrists, axillae, umbilicus, and genital region.1,13 Demodicidosis presents with papules and pustules on the face, usually in a patient with background rosacea and diffuse erythema.1,5,14

If either of these conditions are suspected, mineral oil should be used to prepare the slide because it will maintain viability of the organisms, which are visualized better in motion. Adult scabies mites are roughly 10 times larger than keratinocytes, measuring approximately 250 to 450 µm in length with 8 legs.13 Eggs also may be visualized within the cellular debris and typically are 100 to 150 µm in size and ovoid in shape. Of note, polariscopic examination may be a useful adjunct for evaluation of scabies because scabetic spines and scybala (or fecal material) are polarizable.15

Two types of Demodex mites typically are found in the skin: Demodex folliculorum, which are similarly sized to scabies mites with a more oblong body and occur most commonly in mature hair follicles (eg, eyelashes), and Demodex brevis, which are about half the size (150–200 µm) and live in the sebaceous glands of vellus hairs (Figure 5).14 Both of these mites have 8 legs, similar to the scabies mite.

Hair Preparations

Hair preparations for bulbar examination (eg, trichogram) may prove useful in the evaluation of many types of alopecia, and elaboration on this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Microscopic evaluation of the hair shaft may be an underutilized technique in the outpatient setting and is capable of yielding a variety of diagnoses, including monilethrix, pili torti, and pili trianguli et canaliculi, among others.3 One particularly useful scenario for hair shaft examination (usually of the eyebrow) is in the setting of a patient with severe atopic dermatitis or a baby with ichthyosiform erythroderma, as discovery of trichorrhexis invaginata is pathognomonic for the diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.16 Lastly, evaluation of the hair shaft in patients with patchy and diffuse hair loss whose clinical impression is reminiscent of alopecia areata, or those with concerns of inability to grow hair beyond a short length, may lead to diagnosis of loose anagen syndrome, especially if more than 70% of hair fibers examined exhibit the classic findings of a ruffled proximal cuticle and lack of root sheath.4

Final Thoughts

Bedside microscopy is a rapid and cost-sensitive way to confirm diagnoses that are clinically suspected and remains a valuable tool to acquire during residency training.

Dermatologists are uniquely equipped amongst clinicians to make bedside diagnoses because of the focus on histopathology and microscopy inherent in our training. This skill is highly valuable in both an inpatient and outpatient setting because it may lead to a rapid diagnosis or be a useful adjunct in the initial clinical decision-making process. Although expert microscopists may be able to garner relevant information from scraping almost any type of lesion, bedside microscopy primarily is used by dermatologists in the United States for consideration of infectious etiologies of a variety of cutaneous manifestations.1,2

Basic Principles

Lesions that should be considered for bedside microscopic analysis in outpatient settings are scaly lesions, vesiculobullous lesions, inflammatory papules, and pustules1; microscopic evaluation also can be useful for myriad trichoscopic considerations.3,4 In some instances, direct visualization of the pathogen is possible (eg, cutaneous fungal infections, demodicidosis, scabetic infections), and in other circumstances reactive changes of keratinocytes or the presence of specific cell types can aid in diagnosis (eg, ballooning degeneration and multinucleation of keratinocytes in herpetic lesions, an abundance of eosinophils in erythema toxicum neonatorum). Different types of media are used to best prepare tissue based on the suspected etiology of the condition.

One major stumbling block for residents when beginning to perform bedside testing is the lack of dimensional understanding of the structures they are searching for; for example, medical students and residents often may mistake fibers for dermatophytes, which typically are much larger than fungal hyphae. Familiarizing oneself with the basic dimensions of different cell types or pathogens in relation to each other (Table) will help further refine the beginner’s ability to effectively search for and identify pathogenic features. This concept is further schematized in Figure 1 to help visualize scale differences.

Examination of the Specimen

Slide preparation depends on the primary lesion in consideration and will be discussed in greater detail in the following sections. Once the slide is prepared, place it on the microscope stage and adjust the condenser and light source for optimal visualization. Scan the specimen in a gridlike fashion on low power (usually ×10) and then inspect suspicious findings on higher power (×40 or higher).

Dermatomycoses

Fungal infections of the skin can present as annular papulosquamous lesions, follicular pustules or papules, bullous lesions, hypopigmented patches, and mucosal exudate or erosions, among other manifestations.5 Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is the classic medium used in preparation of lesions being assessed for evidence of fungus because it leads to lysis of keratinocytes for better visualization of fungal hyphae and spores. Other media that contain KOH and additional substrates such as dimethyl sulfoxide or chlorazol black E can be used to better highlight fungal elements.6

Dermatophytosis

Dermatophytes lead to superficial infection of the epidermis and epidermal appendages and present in a variety of ways, including site-specific infections manifesting typically as erythematous, annular or arcuate scaling (eg, tinea faciei, tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea manus, tinea pedis), alopecia with broken hair shafts, black dots, boggy nodules and/or scaling of the scalp (eg, tinea capitis, favus, kerion), and dystrophic nails (eg, onychomycosis).5,7 For examination of lesional skin scrapings, one can either use clear cellophane tape against the skin to remove scale, which is especially useful in the case of pediatric patients, and then press the tape against a slide prepared with several drops of a KOH-based medium to directly visualize without a coverslip, or scrape the lesion with a No. 15 blade and place the scales onto the glass slide, with further preparation as described below.8 For assessment of alopecia or dystrophic nails, scrape lesional skin with a No. 15 blade to obtain affected hair follicles and proximal subungual debris, respectively.6,9

Once the cellular debris has been obtained and placed on the slide, a coverslip can be overlaid and KOH applied laterally to be taken up across the slide by capillary action. Allow the slide to sit for at least 5 minutes before analyzing to better visualize fungal elements. Both tinea and onychomycosis will show branching septate hyphae extending across keratinocytes; a common false-positive is identifying overlapping keratinocyte edges, which are a similar size, but they can be distinguished from fungi because they do not cross multiple keratinocytes.1,8 Tinea capitis may demonstrate similar findings or may reveal hair shafts with spores contained within or surrounding it, corresponding to endothrix or ectothrix infection, respectively.5

Pityriasis Versicolor and Malassezia Folliculitis

Pityriasis versicolor presents with hypopigmented to pink, finely scaling ovoid papules, usually on the upper back, shoulders, and neck, and is caused by Malassezia furfur and other Malassezia species.5 Malassezia folliculitis also is caused by this fungus and presents with monomorphic follicular papules and pustules. Scrapings from the scaly papules will demonstrate keratinocytes with the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” fungal elements, whereas Malassezia folliculitis demonstrates only spores.5,7

Candidiasis

One possible outpatient presentation of candidiasis is oral thrush, which can exhibit white mucosal exudate or erythematous patches. A tongue blade can be used to scrape the tongue or cheek wall, with subsequent preparatory steps with application of KOH as described for dermatophytes. Cutaneous candidiasis most often develops in intertriginous regions and will exhibit erosive painful lesions with satellite pustules. In both cases, analysis of the specimen will show shorter fatter hyphal elements than seen in dermatophytosis, with pseudohyphae, blunted ends, and potentially yeast forms.5

Vesiculobullous Lesions

The Tzanck smear has been used since the 1940s to differentiate between etiologies of blistering disorders and is now most commonly used for the quick identification of herpetic lesions.1 The test is performed by scraping the base of a deroofed vesicle, pustule, or bulla, and smearing the cellular materials onto a glass slide. The most commonly utilized media for staining in the outpatient setting at my institution (University of Texas Dell Medical School, Austin) is Giemsa, which is composed of azure II–eosin, glycerin, and methanol. It stains nuclei a reddish blue to pink and the cytoplasm blue.10 After being applied to the slide, the cells are allowed to air-dry for 5 to 10 minutes, and Giemsa stain is subsequently applied and allowed to incubate for 15 minutes, then rinsed carefully with water and directly examined.

Other stains that can be used to perform the Tzanck smear include commercial preparations that may be more accessible in the inpatient settings such as the Wright-Giemsa, Quik-Dip, and Diff-Quick.1,10

Examination of a Tzanck smear from a herpetic lesion will yield acantholytic, enlarged keratinocytes up to twice their usual size (referred to as ballooning degeneration), and multinucleation. In addition, molding of the nuclei to each other within the multinucleated cells and margination of the nuclear chromatin may be appreciated (Figure 2). Intranuclear inclusion bodies, also known as Cowdry type A bodies, can be seen that are nearly the size of red blood cells but are rare to find, with only 10% of specimens exhibiting this finding in a prospective review of 299 patients with herpetic vesiculobullous lesions.11 Evaluation of the contents of blisters caused by bullous pemphigoid and erythema toxicum neonatorum may yield high densities of eosinophils with normal keratinocyte morphology (Figure 3). Other blistering eruptions such as pemphigus vulgaris and bullous drug eruptions also have characteristic findings.1,2

Gout Preparation

Gout is a systemic disease caused by uric acid accumulation that can present with joint pain and white to red nodules on digits, joints, and ears (known as tophi). Material may be expressed from tophi and examined immediately by polarized light microscopy to confirm the diagnosis.5 Specimens will demonstrate needle-shaped, negatively birefringent monosodium urate crystals on polarized light microscopy (Figure 4). An ordinary light microscope can be converted for such use with the lenses of inexpensive polarized sunglasses, placing one lens between the light source and specimen and the other lens between the examiner’s eye and the specimen.12

Parasitic Infections

Two common parasitic infections identified in outpatient dermatology clinics are scabies mites and Demodex mites. Human scabies is extremely pruritic and caused by infestation with Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis; the typical presentation in an adult is erythematous and crusted papules, linear burrows, and vesiculopustules, especially of the interdigital spaces, wrists, axillae, umbilicus, and genital region.1,13 Demodicidosis presents with papules and pustules on the face, usually in a patient with background rosacea and diffuse erythema.1,5,14

If either of these conditions are suspected, mineral oil should be used to prepare the slide because it will maintain viability of the organisms, which are visualized better in motion. Adult scabies mites are roughly 10 times larger than keratinocytes, measuring approximately 250 to 450 µm in length with 8 legs.13 Eggs also may be visualized within the cellular debris and typically are 100 to 150 µm in size and ovoid in shape. Of note, polariscopic examination may be a useful adjunct for evaluation of scabies because scabetic spines and scybala (or fecal material) are polarizable.15

Two types of Demodex mites typically are found in the skin: Demodex folliculorum, which are similarly sized to scabies mites with a more oblong body and occur most commonly in mature hair follicles (eg, eyelashes), and Demodex brevis, which are about half the size (150–200 µm) and live in the sebaceous glands of vellus hairs (Figure 5).14 Both of these mites have 8 legs, similar to the scabies mite.

Hair Preparations

Hair preparations for bulbar examination (eg, trichogram) may prove useful in the evaluation of many types of alopecia, and elaboration on this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Microscopic evaluation of the hair shaft may be an underutilized technique in the outpatient setting and is capable of yielding a variety of diagnoses, including monilethrix, pili torti, and pili trianguli et canaliculi, among others.3 One particularly useful scenario for hair shaft examination (usually of the eyebrow) is in the setting of a patient with severe atopic dermatitis or a baby with ichthyosiform erythroderma, as discovery of trichorrhexis invaginata is pathognomonic for the diagnosis of Netherton syndrome.16 Lastly, evaluation of the hair shaft in patients with patchy and diffuse hair loss whose clinical impression is reminiscent of alopecia areata, or those with concerns of inability to grow hair beyond a short length, may lead to diagnosis of loose anagen syndrome, especially if more than 70% of hair fibers examined exhibit the classic findings of a ruffled proximal cuticle and lack of root sheath.4

Final Thoughts

Bedside microscopy is a rapid and cost-sensitive way to confirm diagnoses that are clinically suspected and remains a valuable tool to acquire during residency training.

- Wanat KA, Dominguez AR, Carter Z, et al. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:197-218.

- Micheletti RG, Dominguez AR, Wanat KA. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: parasitic and noninfectious diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:221-230.

- Whiting DA, Dy LC. Office diagnosis of hair shaft defects. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:24-34.

- Tosti A. Loose anagen hair syndrome and loose anagen hair. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:521-522.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:620-626.

- Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Raghukumar S, Ravikumar BC. Potassium hydroxide mount with cellophane adhesive: a method for direct diagnosis of dermatophyte skin infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.13573.

- Bhat YJ, Zeerak S, Kanth F, et al. Clinicoepidemiological and mycological study of tinea capitis in the pediatric population of Kashmir Valley: a study from a tertiary care centre. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:100-103.

- Gupta LK, Singhi MK. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295-299.

- Durdu M, Baba M, Seçkin D. The value of Tzanck smear test in diagnosis of erosive, vesicular, bullous, and pustular skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:958-964.

- Fagan TJ, Lidsky MD. Compensated polarized light microscopy using cellophane adhesive tape. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:256-262.

- Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:268-279.

- Desch C, Nutting WB. Demodex folliculorum (Simon) and D. brevis akbulatova of man: redescription and reevaluation. J Parasitol. 1972;58:169-177.

- Foo CW, Florell SR, Bowen AR. Polarizable elements in scabies infestation: a clue to diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:6-10.

- Akkurt ZM, Tuncel T, Ayhan E, et al. Rapid and easy diagnosis of Netherton syndrome with dermoscopy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:280-282.

- Wanat KA, Dominguez AR, Carter Z, et al. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: viral, bacterial, and fungal infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:197-218.

- Micheletti RG, Dominguez AR, Wanat KA. Bedside diagnostics in dermatology: parasitic and noninfectious diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:221-230.

- Whiting DA, Dy LC. Office diagnosis of hair shaft defects. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25:24-34.

- Tosti A. Loose anagen hair syndrome and loose anagen hair. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:521-522.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Lilly KK, Koshnick RL, Grill JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests for toenail onychomycosis: a repeated-measure, single-blinded, cross-sectional evaluation of 7 diagnostic tests. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:620-626.

- Elder DE, ed. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

- Raghukumar S, Ravikumar BC. Potassium hydroxide mount with cellophane adhesive: a method for direct diagnosis of dermatophyte skin infections [published online May 29, 2018]. Clin Exp Dermatol. doi:10.1111/ced.13573.

- Bhat YJ, Zeerak S, Kanth F, et al. Clinicoepidemiological and mycological study of tinea capitis in the pediatric population of Kashmir Valley: a study from a tertiary care centre. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:100-103.

- Gupta LK, Singhi MK. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295-299.

- Durdu M, Baba M, Seçkin D. The value of Tzanck smear test in diagnosis of erosive, vesicular, bullous, and pustular skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:958-964.

- Fagan TJ, Lidsky MD. Compensated polarized light microscopy using cellophane adhesive tape. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:256-262.

- Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:268-279.

- Desch C, Nutting WB. Demodex folliculorum (Simon) and D. brevis akbulatova of man: redescription and reevaluation. J Parasitol. 1972;58:169-177.

- Foo CW, Florell SR, Bowen AR. Polarizable elements in scabies infestation: a clue to diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:6-10.

- Akkurt ZM, Tuncel T, Ayhan E, et al. Rapid and easy diagnosis of Netherton syndrome with dermoscopy. J Cutan Med Surg. 2014;18:280-282.

Physician Burnout in Dermatology

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

- Peckham C. Medscape national physician burnout & depression report 2018. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6009235. Published January 17, 2018. Accessed June 21, 2018.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job

burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397-422. - Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed June 30, 2018.

- Verghese A. How tech can turn doctors into clerical workers. New York Times. May 16, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/05/16/magazine/health-issue-what-we-lose-with-data-driven-medicine.html. Accessed July 3, 2018.

- Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on physician well-being. JAMA. 2018;319:1541-1542.

- Osborne R, Parshuram CS. Delinking resident duty hours from patient safety [published online December 11, 2014]. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(suppl 1):S2.

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.

Many articles about physician burnout and more alarmingly depression and suicide include chilling statistics; however, the data are limited. The same study from Medscape about burnout broken down by medical specialty often is cited.1 Although dermatology fares better than many specialties in this research, the percentages are still abysmal.

I am writing as a physician, for physicians. I do not want to quote the data to you. If you are reading this article, you have probably felt some burnout, even transiently. Maybe you even feel it now, at this very moment. Physicians are competitive capable people. I do not want to present numbers and statistics that make you question the validity of your feelings, whether you fit with the average statistics, or make you try to calculate how many of your friends or colleagues match these statistics. The numbers are terrible, no matter how you look at them, and all trends show them worsening with time.

What is burnout?

To simply define burnout as fatigue or high workload would be to undervalue the term. Physicians are trained through college, medical school, and countless hours of residency to cope with both challenges. Maslach et al2 defined burnout as “a psychological syndrome in response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” leading to “overwhelming exhaustion, feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.”

Who does burnout affect?

Physician burnout affects both the patient and the physician. It has been demonstrated that physician burnout leads to lower patient satisfaction and care as well as higher risk for medical errors. There are the more obvious and direct effects on the physician, with affected physicians having much higher employment turnover and risk for addiction and suicide.3 One could argue that there are even more downstream effects of burnout, including physicians’ families who may be directly affected and even societal effects when fully trained physicians leave the clinical arena to pursue other careers.

How do you recognize when you are burnt out?

The first time I recognized that I was burnt out was in medical school. I understood my burnout through the lens of my undergraduate training in anthropology as compassion fatigue, a term that has been used to describe the lack of empathy that can develop when any individual is presented with an overwhelming tragedy or horror. When you are in survival mode—waking up just to survive the next day or clinic shift or call—you are surviving but hardly thriving as a physician.3 I believe that humans have a tremendous capacity for survival, but when we are in survival mode we have little energy leftover for the pleasures of life, from family to hobbies. I would similarly argue that in survival mode we have limited ability to appreciate the pain and suffering our patients are experiencing. Survival mode limits our ability as physicians to connect with our patients and to engage in the full spectrum of emotion in our time outside of our job.

What are the causes of burnout in dermatology?

As dermatologists, we often have milder on-call schedules and fewer critically ill patients than many of our medical colleagues. For this reason, we may be afraid to address the real role of physician burnout in our field. Fellow dermatologist Jeffrey Benabio, MD (San Diego, California), notes that the phrase dermatologist burnout may even seem oxymoronic, but we face many of the same daily frustrations with electronic medical records, increasing patient volume, and insurance struggles.4 The electronic medical record looms large in many physicians’ complaints these days. A recent article in the New York Times described the physician as “the highest-paid clerical worker in the hospital,”5 which is not wrong. For every hour of patient time, we have nearly double that spent on paperwork.5

Dike Drummond, MD, a family practice physician who focuses on physician burnout, notes that physicians are taught very early to put the patient first, but it is never discussed when or how to turn this switch off.3 However, there is little written about dermatology-specific burnout. A problem that is not studied or even considered will be harder to fix.

Why does it matter?

I believe that addressing physician burnout is critical for 2 reasons: (1) we can improve patient care by improving patient satisfaction and decreasing medical error, and (2) we can find greater satisfaction and professional fulfillment while caring for our patients. Ultimately, patient care and physician care are intimately linked; as stated by Thomas et al,6 “[p]hysicians who are well can best serve their patients.”

As a resident in 2018, I recognize that my coresidents and I are training as physicians in the time of “duty hours” and an ongoing discussion of burnout. However, I sense a burnout fatigue setting in among residents, many who do not want to discuss wellness anymore. The newer data suggest that work hour restrictions do not improve patient safety, negating one of the driving reasons for the change.7 At the same time, residency programs are initiating wellness programs in response to the growing literature on physician burnout. These wellness programs vary in the types of activities included, from individual coping techniques such as mindfulness training to social gatherings for the residents. In general, these wellness initiatives focus on burnout at the individual level, but they do not take into account systemic or structural challenges that might contribute to this worsening epidemic.

Final Thoughts

As a profession, I believe that physicians have internalized the concept of burnout to equate with a personal individual failing. At various times in my training, I have felt that if I could just practice mediation, study more, or shift my perspective, I personally could overcome burnout. I have intermittently felt my burnout as proof that I should never have become a physician. As a woman and the first physician in my family, fighting the sense of burnout so early in my career seemed demoralizing and nearly drove me to change my career path. It exacerbated my sense of imposter syndrome: that I never truly belonged in medicine at all. After much soul-searching, I have concluded that burnout is a concept propagated by administrators and businesspeople to stigmatize the reaction by many physicians to the growing trends in medicine and cast it as a personal failure rather than as the symptom of a broken medical system.

If we continue to identify burnout as an individual failing and treat it as such, I believe that we will fail to stem the growing trend within dermatology and within medicine more broadly. We need to consider the driving factors behind dermatology burnout so that we can begin to address them at a structural level.