User login

#Dermlife and the Burned-out Resident

Dermatologist Dr. Jeffrey Benabio quipped, “The phrase ‘dermatologist burnout’ may seem as oxymoronic as jumbo shrimp, yet both are real.”1 Indeed, dermatologists often self-report as among the happiest specialists both at work and home, according to the annual Medscape Physician Lifestyle and Happiness Report.2 Similarly, others in the medical field may perceive dermatologists as low-stress providers—well-groomed, well-rested rays of sunshine, getting out of work every day at 5:00

Burnout in Dermatology Residents

Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment that affects residents of all specialties3; however, there is a paucity of literature on burnout as it relates to dermatology. Although long work hours and schedule volatility have captured the focus of resident burnout conversations, a less discussed set of factors may contribute to dermatology resident burnout, such as increasing patient load, intensifying regulations, and an unrelenting pace of clinic. A recent survey study by Shoimer et al3 found that 61% of 116 participating Canadian dermatology residents cited examinations (including the board certifying examination) as their top stressor, followed by work (27%). Other stressors included family, relationships, finances, pressure from staff, research, and moving. More than 50% of dermatology residents surveyed experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while 40% demonstrated a low sense of personal accomplishment, all of which are determinants of the burnout syndrome.3

Comparison to Residents in Other Specialties

Although dermatology residents experience lower burnout rates than colleagues in other specialties, the absolute prevalence warrants attention. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association of 3588 second-year medical residents in the United States found that rates of burnout symptoms across clinical specialties ranged from 29.6% to 63.8%. The highest rates of burnout were found in urology (63.8%), neurology (61.6%), and ophthalmology (55.8%), but the lowest reported rate of burnout was demonstrated in dermatology (29.6%).4 Although dermatology ranked the lowest, that is still nearly a whopping 1 in 3 dermatology residents with burnout symptoms. The absolute prevalence should not be obscured by the ranking among other specialties.

Preventing Burnout

Several burnout prevention and coping strategies across specialties have been suggested.

Mindfulness and Self-awareness

A study by Chaukos et al5 found that mindfulness and self-awareness are resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Counseling is one strategy demonstrated to increase self-awareness. Mindfulness may be practiced through meditation or yoga. Regular meditation has been shown to improve mood and emotional stress.6 Similarly, yoga has been shown to yield physical, emotional, and psychological benefits to resdients.7

Work Factors

A supportive clinical faculty and receiving constructive monthly performance feedback have been negatively correlated with dermatology resident burnout.3 Other workplace interventions demonstrating utility in decreasing resident burnout include increasing staff awareness about burnout, increasing support for health professionals treating challenging populations, and ensuring a reasonable workload.6

Sleep

It has been demonstrated that sleeping less than 7 hours per night also is associated with resident burnout,7 yet it has been reported that 72% of dermatology residents fall into this category.3 Poor sleep quality has been shown to be a predictor of lower academic performance. It has been proposed that to minimize sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality, institutions should focus on programs that promote regular exercise, sleep hygiene, mindfulness, and time-out activities such as meditation.7

Social Support

Focusing on peers may foster the inner strength to endure suffering.1 Venting, laughing, and discussing care with colleagues has been demonstrated to decrease anxiety.6 Work-related social networks may be strengthened through attendance at conferences, lectures, and professional organizations.7 Additionally, social supports and spending quality time with family have been demonstrated as negative predictors of dermatology resident burnout.3

Physical Exercise

Exercise has been demonstrated to improve mood, anxiety, and depression, thereby decreasing resident burnout.6

Final Thoughts

Burnout among dermatology residents warrants awareness, as it does in other medical specialties. Awareness may facilitate identification and prevention, the latter of which is perhaps best summarized by the words of psychologist Dr. Christina Maslach: “If all of the knowledge and advice about how to beat burnout could be summed up in 1 word, that word would be balance—balance between giving and getting, balance between stress and calm, balance between work and home.”8

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Martin KL. Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-happiness-6011057. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Shoimer I, Patten S, Mydlarski P. Burnout in dermatology residents: a Canadian perspective. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:270-271.

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among us resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114-1130.

- Chaukos D, Chaed-Friedman E, Mehta D, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:189-194.

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;2:236-242.

- Tolentino J, Guo W, Ricca R, et al. What’s new in academic medicine: can we effectively address the burnout epidemic in healthcare? Int J Acad Med. 2017;3.

- Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis; 1993:19-32.

Dermatologist Dr. Jeffrey Benabio quipped, “The phrase ‘dermatologist burnout’ may seem as oxymoronic as jumbo shrimp, yet both are real.”1 Indeed, dermatologists often self-report as among the happiest specialists both at work and home, according to the annual Medscape Physician Lifestyle and Happiness Report.2 Similarly, others in the medical field may perceive dermatologists as low-stress providers—well-groomed, well-rested rays of sunshine, getting out of work every day at 5:00

Burnout in Dermatology Residents

Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment that affects residents of all specialties3; however, there is a paucity of literature on burnout as it relates to dermatology. Although long work hours and schedule volatility have captured the focus of resident burnout conversations, a less discussed set of factors may contribute to dermatology resident burnout, such as increasing patient load, intensifying regulations, and an unrelenting pace of clinic. A recent survey study by Shoimer et al3 found that 61% of 116 participating Canadian dermatology residents cited examinations (including the board certifying examination) as their top stressor, followed by work (27%). Other stressors included family, relationships, finances, pressure from staff, research, and moving. More than 50% of dermatology residents surveyed experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while 40% demonstrated a low sense of personal accomplishment, all of which are determinants of the burnout syndrome.3

Comparison to Residents in Other Specialties

Although dermatology residents experience lower burnout rates than colleagues in other specialties, the absolute prevalence warrants attention. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association of 3588 second-year medical residents in the United States found that rates of burnout symptoms across clinical specialties ranged from 29.6% to 63.8%. The highest rates of burnout were found in urology (63.8%), neurology (61.6%), and ophthalmology (55.8%), but the lowest reported rate of burnout was demonstrated in dermatology (29.6%).4 Although dermatology ranked the lowest, that is still nearly a whopping 1 in 3 dermatology residents with burnout symptoms. The absolute prevalence should not be obscured by the ranking among other specialties.

Preventing Burnout

Several burnout prevention and coping strategies across specialties have been suggested.

Mindfulness and Self-awareness

A study by Chaukos et al5 found that mindfulness and self-awareness are resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Counseling is one strategy demonstrated to increase self-awareness. Mindfulness may be practiced through meditation or yoga. Regular meditation has been shown to improve mood and emotional stress.6 Similarly, yoga has been shown to yield physical, emotional, and psychological benefits to resdients.7

Work Factors

A supportive clinical faculty and receiving constructive monthly performance feedback have been negatively correlated with dermatology resident burnout.3 Other workplace interventions demonstrating utility in decreasing resident burnout include increasing staff awareness about burnout, increasing support for health professionals treating challenging populations, and ensuring a reasonable workload.6

Sleep

It has been demonstrated that sleeping less than 7 hours per night also is associated with resident burnout,7 yet it has been reported that 72% of dermatology residents fall into this category.3 Poor sleep quality has been shown to be a predictor of lower academic performance. It has been proposed that to minimize sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality, institutions should focus on programs that promote regular exercise, sleep hygiene, mindfulness, and time-out activities such as meditation.7

Social Support

Focusing on peers may foster the inner strength to endure suffering.1 Venting, laughing, and discussing care with colleagues has been demonstrated to decrease anxiety.6 Work-related social networks may be strengthened through attendance at conferences, lectures, and professional organizations.7 Additionally, social supports and spending quality time with family have been demonstrated as negative predictors of dermatology resident burnout.3

Physical Exercise

Exercise has been demonstrated to improve mood, anxiety, and depression, thereby decreasing resident burnout.6

Final Thoughts

Burnout among dermatology residents warrants awareness, as it does in other medical specialties. Awareness may facilitate identification and prevention, the latter of which is perhaps best summarized by the words of psychologist Dr. Christina Maslach: “If all of the knowledge and advice about how to beat burnout could be summed up in 1 word, that word would be balance—balance between giving and getting, balance between stress and calm, balance between work and home.”8

Dermatologist Dr. Jeffrey Benabio quipped, “The phrase ‘dermatologist burnout’ may seem as oxymoronic as jumbo shrimp, yet both are real.”1 Indeed, dermatologists often self-report as among the happiest specialists both at work and home, according to the annual Medscape Physician Lifestyle and Happiness Report.2 Similarly, others in the medical field may perceive dermatologists as low-stress providers—well-groomed, well-rested rays of sunshine, getting out of work every day at 5:00

Burnout in Dermatology Residents

Burnout is a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment that affects residents of all specialties3; however, there is a paucity of literature on burnout as it relates to dermatology. Although long work hours and schedule volatility have captured the focus of resident burnout conversations, a less discussed set of factors may contribute to dermatology resident burnout, such as increasing patient load, intensifying regulations, and an unrelenting pace of clinic. A recent survey study by Shoimer et al3 found that 61% of 116 participating Canadian dermatology residents cited examinations (including the board certifying examination) as their top stressor, followed by work (27%). Other stressors included family, relationships, finances, pressure from staff, research, and moving. More than 50% of dermatology residents surveyed experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while 40% demonstrated a low sense of personal accomplishment, all of which are determinants of the burnout syndrome.3

Comparison to Residents in Other Specialties

Although dermatology residents experience lower burnout rates than colleagues in other specialties, the absolute prevalence warrants attention. A recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association of 3588 second-year medical residents in the United States found that rates of burnout symptoms across clinical specialties ranged from 29.6% to 63.8%. The highest rates of burnout were found in urology (63.8%), neurology (61.6%), and ophthalmology (55.8%), but the lowest reported rate of burnout was demonstrated in dermatology (29.6%).4 Although dermatology ranked the lowest, that is still nearly a whopping 1 in 3 dermatology residents with burnout symptoms. The absolute prevalence should not be obscured by the ranking among other specialties.

Preventing Burnout

Several burnout prevention and coping strategies across specialties have been suggested.

Mindfulness and Self-awareness

A study by Chaukos et al5 found that mindfulness and self-awareness are resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Counseling is one strategy demonstrated to increase self-awareness. Mindfulness may be practiced through meditation or yoga. Regular meditation has been shown to improve mood and emotional stress.6 Similarly, yoga has been shown to yield physical, emotional, and psychological benefits to resdients.7

Work Factors

A supportive clinical faculty and receiving constructive monthly performance feedback have been negatively correlated with dermatology resident burnout.3 Other workplace interventions demonstrating utility in decreasing resident burnout include increasing staff awareness about burnout, increasing support for health professionals treating challenging populations, and ensuring a reasonable workload.6

Sleep

It has been demonstrated that sleeping less than 7 hours per night also is associated with resident burnout,7 yet it has been reported that 72% of dermatology residents fall into this category.3 Poor sleep quality has been shown to be a predictor of lower academic performance. It has been proposed that to minimize sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality, institutions should focus on programs that promote regular exercise, sleep hygiene, mindfulness, and time-out activities such as meditation.7

Social Support

Focusing on peers may foster the inner strength to endure suffering.1 Venting, laughing, and discussing care with colleagues has been demonstrated to decrease anxiety.6 Work-related social networks may be strengthened through attendance at conferences, lectures, and professional organizations.7 Additionally, social supports and spending quality time with family have been demonstrated as negative predictors of dermatology resident burnout.3

Physical Exercise

Exercise has been demonstrated to improve mood, anxiety, and depression, thereby decreasing resident burnout.6

Final Thoughts

Burnout among dermatology residents warrants awareness, as it does in other medical specialties. Awareness may facilitate identification and prevention, the latter of which is perhaps best summarized by the words of psychologist Dr. Christina Maslach: “If all of the knowledge and advice about how to beat burnout could be summed up in 1 word, that word would be balance—balance between giving and getting, balance between stress and calm, balance between work and home.”8

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Martin KL. Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-happiness-6011057. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Shoimer I, Patten S, Mydlarski P. Burnout in dermatology residents: a Canadian perspective. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:270-271.

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among us resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114-1130.

- Chaukos D, Chaed-Friedman E, Mehta D, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:189-194.

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;2:236-242.

- Tolentino J, Guo W, Ricca R, et al. What’s new in academic medicine: can we effectively address the burnout epidemic in healthcare? Int J Acad Med. 2017;3.

- Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis; 1993:19-32.

- Benabio J. Burnout. Dermatology News. November 14, 2017. https://www.mdedge.com/edermatologynews/article/152098/business-medicine/burnout. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Martin KL. Medscape Physician Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019. Medscape website. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-happiness-6011057. Published January 9, 2019. Accessed August 14, 2019.

- Shoimer I, Patten S, Mydlarski P. Burnout in dermatology residents: a Canadian perspective. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:270-271.

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among us resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114-1130.

- Chaukos D, Chaed-Friedman E, Mehta D, et al. Risk and resilience factors associated with resident burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41:189-194.

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;2:236-242.

- Tolentino J, Guo W, Ricca R, et al. What’s new in academic medicine: can we effectively address the burnout epidemic in healthcare? Int J Acad Med. 2017;3.

- Maslach C. Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In: Schaufeli W, Maslach C, Marek T, eds. Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis; 1993:19-32.

Resident Pearl

- Reported techniques for preventing and coping with resident burnout include mindfulness and self-awareness, optimization of workplace factors, adequate sleep, social support, and physical exercise.

Challenges of Treating Primary Psychiatric Disease in Dermatology

Dermatology patients experience a high burden of mental health disturbance. Psychiatric disease is seen in an estimated 30% to 60% of our patients.1 It can be secondary to or comorbid with dermatologic disorders, or it can be the primary condition that is driving cutaneous disease. Patients with secondary or comorbid psychiatric disorders often are amenable to referral to a mental health provider or are already participating in some form of mental health treatment; however, patients with primary psychiatric disease who present to dermatology generally do not accept these referrals.2 Therefore, if these patients are to receive care anywhere in the health care system, it often must be in the department of dermatology.

What primary psychiatric conditions do we see in dermatology?

Common primary psychiatric conditions seen in dermatology include delusional infestation, obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders, and dermatitis artefacta.

Delusional Infestation

Also known as delusions of parasitosis or delusional parasitosis, delusional infestation presents as a fixed false belief that there is an organism or other foreign entity that is present in the skin and is the cause of cutaneous disruption. It often is an isolated delusion but can have a notable psychosocial impact. The term delusional infestation is sometimes preferred, as it is inclusive of delusions focused on any type of organism, not just parasites. It also encompasses delusions of infestation with nonliving matter such as fibers, also known as Morgellons disease.3

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders

This broad category includes several conditions encountered in dermatology. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), excoriation disorder, and trichotillomania are some of the most common variants. In patients with BDD, skin and hair are the 2 most common preoccupations. It has been estimated that 12% of dermatology patients experience BDD. Unsurprisingly, it is more common in patients presenting to cosmetic dermatology, but general dermatology patients also are affected at a rate of 7%.2 Patients with ORS falsely believe they have body odor and/or halitosis. Excoriation disorder manifests as repetitive skin picking, either of normal skin or of lesions such as pimples and scabs. Trichotillomania presents as repeated hair pulling, and trichophagia (eating the pulled hair) also may be present.

Dermatitis Artefacta

Almost 1 in 4 patients who seek dermatologic evaluation for primarily psychiatric disorders have dermatitis artefacta, the presence of deliberately self-inflicted skin lesions.2 Patients with dermatitis artefacta have unconscious motives for their behavior and should be distinguished from malingering patients who have a conscious goal of secondary gain.

What treatments are available?

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the first-line treatments for BDD and may be useful in ORS. In excoriation disorder and trichotillomania, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed pharmacotherapy, but they have limited efficacy.2

Antipsychotics

The recommended treatment of delusional infestation is antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Treatment with risperidone and olanzapine has been reported to achieve full or partial remission in more than two-thirds of cases.4 Aripiprazole, a newer antipsychotic, has fewer side effects and has been successful in several case reports.5-7

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Psychotherapy, most often in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy, has been reported as effective treatment of several psychocutaneous diseases. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered first-line treatment of body-focused repetitive behavior disorders such as excoriation disorder and trichotillomania.2 It addresses maladaptive thought patterns to modify behavior.

Who treats patients with neurodermatoses?

If a patient presents to dermatology with a rash found to be related to an underlying thyroid disorder, the treatment plan likely would include referral to an endocrinologist. Similarly, patients with primary psychiatric conditions presenting to dermatology should ideally be referred to psychiatrists or psychotherapists, the providers most thoroughly trained and best equipped to treat them. The challenge in psychodermatology is that patients often are resistant to the assessment that the primary pathology is psychiatric. Patients may deny that they are “crazy” and see numerous providers in search of a dermatologist who “believes” them.8

Referral to mental health professionals almost always is refused by patients with primarily psychiatric neurodermatoses, which presents dermatologists with a dilemma. As the authors of the “Psychotropic Agents” chapter of Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy put it: “A dermatologist has two choices. The first is to try to ‘look the other way’ and pacify the patient by providing relatively benign, but minimally effective treatments. The other option is to try to directly address the psychological/psychiatric problems.” The chapter then provides a thorough guide for the use of psychotropic medications in the dermatology population, advocating for option 2: treatment by dermatologists.9

Should a dermatologist prescribe psychotropic drugs?

In Dermatology, the principle reference textbook in many dermatology training programs, it is stated that “[a]lthough less comprehensive than treatment delivered in collaboration with a psychiatrist, in the authors’ opinion, management of these issues by a dermatologist is better than no treatment at all.”10 Recent reviews in the dermatologic literature of psychiatric diseases and drugs in dermatology agree that dermatologists should feel comfortable with prescribing pharmacologic treatment.2,8,11 Performance of psychotherapy by dermatologists, on the other hand, is not recommended based on time constraints and lack of training.

Despite the apparent agreement in the texts and literature that pharmacotherapy of psychiatric neurodermatoses is within our scope of practice in dermatology, most dermatologists do not prescribe psychotropic agents. Dermatology residencies generally do not provide thorough training in psychopharmacotherapy.9 Unsurprisingly, a survey of 40 dermatologists at one academic institution found that only 11% felt comfortable prescribing an antidepressant and a mere 3% were comfortable prescribing an antipsychotic.12

Final Thoughts

The challenges involved in managing patients with primary psychiatric disease in dermatology are great and many patients are undertreated despite the availability of effective, evidence-based treatment options. We need to continue to work toward providing better access to these treatments in a way that maximizes the chance that our patients will accept our care.

- Korabel H, Dudek D, Jaworek A, et al. Psychodermatology: psychological and psychiatrical aspects of dermatology [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:244-248.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG, Holland PJ. Review of epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of common primary psychiatric causes of cutaneous disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:418-427.

- Bewley AP, Lepping P, Freundenmann RW, et al. Delusional parasitosis: time to call it delusional infestation. Br J Dermatol. 2018;163:1-2.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:500-508.

- Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Ogino S, et al. Successful treatment of delusional disorder with low-dose aripiprazole. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:369.

- Ladizinski B, Busse KL, Bhutani T, et al. Aripiprazole as a viable alternative for treating delusions of parasitosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1531-1532.

- Huang WL, Chang LR. Aripiprazole in the treatment of delusional parasitosis with ocular and dermatologic presentations. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:272-273.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1428-1434.

- Bhutani T, Lee CS, Koo JYM. Psychotropic agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:375-388.

- Duncan KO, Koo JYM. Psychocutaneous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:128-137.

- Shah B, Levenson JL. Use of psychotropic drugs in the dermatology patient: when to start and stop? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:748-755.

- Gee SN, Zakhary L, Keuthen N, et al. A survey assessment of the recognition and treatment of psychocutaneous disorders in the outpatient dermatology setting: how prepared are we? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:47-52.

Dermatology patients experience a high burden of mental health disturbance. Psychiatric disease is seen in an estimated 30% to 60% of our patients.1 It can be secondary to or comorbid with dermatologic disorders, or it can be the primary condition that is driving cutaneous disease. Patients with secondary or comorbid psychiatric disorders often are amenable to referral to a mental health provider or are already participating in some form of mental health treatment; however, patients with primary psychiatric disease who present to dermatology generally do not accept these referrals.2 Therefore, if these patients are to receive care anywhere in the health care system, it often must be in the department of dermatology.

What primary psychiatric conditions do we see in dermatology?

Common primary psychiatric conditions seen in dermatology include delusional infestation, obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders, and dermatitis artefacta.

Delusional Infestation

Also known as delusions of parasitosis or delusional parasitosis, delusional infestation presents as a fixed false belief that there is an organism or other foreign entity that is present in the skin and is the cause of cutaneous disruption. It often is an isolated delusion but can have a notable psychosocial impact. The term delusional infestation is sometimes preferred, as it is inclusive of delusions focused on any type of organism, not just parasites. It also encompasses delusions of infestation with nonliving matter such as fibers, also known as Morgellons disease.3

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders

This broad category includes several conditions encountered in dermatology. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), excoriation disorder, and trichotillomania are some of the most common variants. In patients with BDD, skin and hair are the 2 most common preoccupations. It has been estimated that 12% of dermatology patients experience BDD. Unsurprisingly, it is more common in patients presenting to cosmetic dermatology, but general dermatology patients also are affected at a rate of 7%.2 Patients with ORS falsely believe they have body odor and/or halitosis. Excoriation disorder manifests as repetitive skin picking, either of normal skin or of lesions such as pimples and scabs. Trichotillomania presents as repeated hair pulling, and trichophagia (eating the pulled hair) also may be present.

Dermatitis Artefacta

Almost 1 in 4 patients who seek dermatologic evaluation for primarily psychiatric disorders have dermatitis artefacta, the presence of deliberately self-inflicted skin lesions.2 Patients with dermatitis artefacta have unconscious motives for their behavior and should be distinguished from malingering patients who have a conscious goal of secondary gain.

What treatments are available?

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the first-line treatments for BDD and may be useful in ORS. In excoriation disorder and trichotillomania, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed pharmacotherapy, but they have limited efficacy.2

Antipsychotics

The recommended treatment of delusional infestation is antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Treatment with risperidone and olanzapine has been reported to achieve full or partial remission in more than two-thirds of cases.4 Aripiprazole, a newer antipsychotic, has fewer side effects and has been successful in several case reports.5-7

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Psychotherapy, most often in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy, has been reported as effective treatment of several psychocutaneous diseases. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered first-line treatment of body-focused repetitive behavior disorders such as excoriation disorder and trichotillomania.2 It addresses maladaptive thought patterns to modify behavior.

Who treats patients with neurodermatoses?

If a patient presents to dermatology with a rash found to be related to an underlying thyroid disorder, the treatment plan likely would include referral to an endocrinologist. Similarly, patients with primary psychiatric conditions presenting to dermatology should ideally be referred to psychiatrists or psychotherapists, the providers most thoroughly trained and best equipped to treat them. The challenge in psychodermatology is that patients often are resistant to the assessment that the primary pathology is psychiatric. Patients may deny that they are “crazy” and see numerous providers in search of a dermatologist who “believes” them.8

Referral to mental health professionals almost always is refused by patients with primarily psychiatric neurodermatoses, which presents dermatologists with a dilemma. As the authors of the “Psychotropic Agents” chapter of Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy put it: “A dermatologist has two choices. The first is to try to ‘look the other way’ and pacify the patient by providing relatively benign, but minimally effective treatments. The other option is to try to directly address the psychological/psychiatric problems.” The chapter then provides a thorough guide for the use of psychotropic medications in the dermatology population, advocating for option 2: treatment by dermatologists.9

Should a dermatologist prescribe psychotropic drugs?

In Dermatology, the principle reference textbook in many dermatology training programs, it is stated that “[a]lthough less comprehensive than treatment delivered in collaboration with a psychiatrist, in the authors’ opinion, management of these issues by a dermatologist is better than no treatment at all.”10 Recent reviews in the dermatologic literature of psychiatric diseases and drugs in dermatology agree that dermatologists should feel comfortable with prescribing pharmacologic treatment.2,8,11 Performance of psychotherapy by dermatologists, on the other hand, is not recommended based on time constraints and lack of training.

Despite the apparent agreement in the texts and literature that pharmacotherapy of psychiatric neurodermatoses is within our scope of practice in dermatology, most dermatologists do not prescribe psychotropic agents. Dermatology residencies generally do not provide thorough training in psychopharmacotherapy.9 Unsurprisingly, a survey of 40 dermatologists at one academic institution found that only 11% felt comfortable prescribing an antidepressant and a mere 3% were comfortable prescribing an antipsychotic.12

Final Thoughts

The challenges involved in managing patients with primary psychiatric disease in dermatology are great and many patients are undertreated despite the availability of effective, evidence-based treatment options. We need to continue to work toward providing better access to these treatments in a way that maximizes the chance that our patients will accept our care.

Dermatology patients experience a high burden of mental health disturbance. Psychiatric disease is seen in an estimated 30% to 60% of our patients.1 It can be secondary to or comorbid with dermatologic disorders, or it can be the primary condition that is driving cutaneous disease. Patients with secondary or comorbid psychiatric disorders often are amenable to referral to a mental health provider or are already participating in some form of mental health treatment; however, patients with primary psychiatric disease who present to dermatology generally do not accept these referrals.2 Therefore, if these patients are to receive care anywhere in the health care system, it often must be in the department of dermatology.

What primary psychiatric conditions do we see in dermatology?

Common primary psychiatric conditions seen in dermatology include delusional infestation, obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders, and dermatitis artefacta.

Delusional Infestation

Also known as delusions of parasitosis or delusional parasitosis, delusional infestation presents as a fixed false belief that there is an organism or other foreign entity that is present in the skin and is the cause of cutaneous disruption. It often is an isolated delusion but can have a notable psychosocial impact. The term delusional infestation is sometimes preferred, as it is inclusive of delusions focused on any type of organism, not just parasites. It also encompasses delusions of infestation with nonliving matter such as fibers, also known as Morgellons disease.3

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders

This broad category includes several conditions encountered in dermatology. Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), olfactory reference syndrome (ORS), excoriation disorder, and trichotillomania are some of the most common variants. In patients with BDD, skin and hair are the 2 most common preoccupations. It has been estimated that 12% of dermatology patients experience BDD. Unsurprisingly, it is more common in patients presenting to cosmetic dermatology, but general dermatology patients also are affected at a rate of 7%.2 Patients with ORS falsely believe they have body odor and/or halitosis. Excoriation disorder manifests as repetitive skin picking, either of normal skin or of lesions such as pimples and scabs. Trichotillomania presents as repeated hair pulling, and trichophagia (eating the pulled hair) also may be present.

Dermatitis Artefacta

Almost 1 in 4 patients who seek dermatologic evaluation for primarily psychiatric disorders have dermatitis artefacta, the presence of deliberately self-inflicted skin lesions.2 Patients with dermatitis artefacta have unconscious motives for their behavior and should be distinguished from malingering patients who have a conscious goal of secondary gain.

What treatments are available?

Antidepressants

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one of the first-line treatments for BDD and may be useful in ORS. In excoriation disorder and trichotillomania, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the most commonly prescribed pharmacotherapy, but they have limited efficacy.2

Antipsychotics

The recommended treatment of delusional infestation is antipsychotic pharmacotherapy. Treatment with risperidone and olanzapine has been reported to achieve full or partial remission in more than two-thirds of cases.4 Aripiprazole, a newer antipsychotic, has fewer side effects and has been successful in several case reports.5-7

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Psychotherapy, most often in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy, has been reported as effective treatment of several psychocutaneous diseases. Cognitive behavioral therapy is considered first-line treatment of body-focused repetitive behavior disorders such as excoriation disorder and trichotillomania.2 It addresses maladaptive thought patterns to modify behavior.

Who treats patients with neurodermatoses?

If a patient presents to dermatology with a rash found to be related to an underlying thyroid disorder, the treatment plan likely would include referral to an endocrinologist. Similarly, patients with primary psychiatric conditions presenting to dermatology should ideally be referred to psychiatrists or psychotherapists, the providers most thoroughly trained and best equipped to treat them. The challenge in psychodermatology is that patients often are resistant to the assessment that the primary pathology is psychiatric. Patients may deny that they are “crazy” and see numerous providers in search of a dermatologist who “believes” them.8

Referral to mental health professionals almost always is refused by patients with primarily psychiatric neurodermatoses, which presents dermatologists with a dilemma. As the authors of the “Psychotropic Agents” chapter of Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy put it: “A dermatologist has two choices. The first is to try to ‘look the other way’ and pacify the patient by providing relatively benign, but minimally effective treatments. The other option is to try to directly address the psychological/psychiatric problems.” The chapter then provides a thorough guide for the use of psychotropic medications in the dermatology population, advocating for option 2: treatment by dermatologists.9

Should a dermatologist prescribe psychotropic drugs?

In Dermatology, the principle reference textbook in many dermatology training programs, it is stated that “[a]lthough less comprehensive than treatment delivered in collaboration with a psychiatrist, in the authors’ opinion, management of these issues by a dermatologist is better than no treatment at all.”10 Recent reviews in the dermatologic literature of psychiatric diseases and drugs in dermatology agree that dermatologists should feel comfortable with prescribing pharmacologic treatment.2,8,11 Performance of psychotherapy by dermatologists, on the other hand, is not recommended based on time constraints and lack of training.

Despite the apparent agreement in the texts and literature that pharmacotherapy of psychiatric neurodermatoses is within our scope of practice in dermatology, most dermatologists do not prescribe psychotropic agents. Dermatology residencies generally do not provide thorough training in psychopharmacotherapy.9 Unsurprisingly, a survey of 40 dermatologists at one academic institution found that only 11% felt comfortable prescribing an antidepressant and a mere 3% were comfortable prescribing an antipsychotic.12

Final Thoughts

The challenges involved in managing patients with primary psychiatric disease in dermatology are great and many patients are undertreated despite the availability of effective, evidence-based treatment options. We need to continue to work toward providing better access to these treatments in a way that maximizes the chance that our patients will accept our care.

- Korabel H, Dudek D, Jaworek A, et al. Psychodermatology: psychological and psychiatrical aspects of dermatology [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:244-248.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG, Holland PJ. Review of epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of common primary psychiatric causes of cutaneous disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:418-427.

- Bewley AP, Lepping P, Freundenmann RW, et al. Delusional parasitosis: time to call it delusional infestation. Br J Dermatol. 2018;163:1-2.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:500-508.

- Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Ogino S, et al. Successful treatment of delusional disorder with low-dose aripiprazole. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:369.

- Ladizinski B, Busse KL, Bhutani T, et al. Aripiprazole as a viable alternative for treating delusions of parasitosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1531-1532.

- Huang WL, Chang LR. Aripiprazole in the treatment of delusional parasitosis with ocular and dermatologic presentations. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:272-273.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1428-1434.

- Bhutani T, Lee CS, Koo JYM. Psychotropic agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:375-388.

- Duncan KO, Koo JYM. Psychocutaneous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:128-137.

- Shah B, Levenson JL. Use of psychotropic drugs in the dermatology patient: when to start and stop? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:748-755.

- Gee SN, Zakhary L, Keuthen N, et al. A survey assessment of the recognition and treatment of psychocutaneous disorders in the outpatient dermatology setting: how prepared are we? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:47-52.

- Korabel H, Dudek D, Jaworek A, et al. Psychodermatology: psychological and psychiatrical aspects of dermatology [in Polish]. Przegl Lek. 2008;65:244-248.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG, Holland PJ. Review of epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of common primary psychiatric causes of cutaneous disease. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:418-427.

- Bewley AP, Lepping P, Freundenmann RW, et al. Delusional parasitosis: time to call it delusional infestation. Br J Dermatol. 2018;163:1-2.

- Freudenmann RW, Lepping P. Second-generation antipsychotics in primary and secondary delusional parasitosis: outcome and efficacy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:500-508.

- Miyamoto S, Miyake N, Ogino S, et al. Successful treatment of delusional disorder with low-dose aripiprazole. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:369.

- Ladizinski B, Busse KL, Bhutani T, et al. Aripiprazole as a viable alternative for treating delusions of parasitosis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1531-1532.

- Huang WL, Chang LR. Aripiprazole in the treatment of delusional parasitosis with ocular and dermatologic presentations. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:272-273.

- Campbell EH, Elston DM, Hawthorne JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of delusional parasitosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1428-1434.

- Bhutani T, Lee CS, Koo JYM. Psychotropic agents. In: Wolverton SE, ed. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 3rd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2013:375-388.

- Duncan KO, Koo JYM. Psychocutaneous diseases. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018:128-137.

- Shah B, Levenson JL. Use of psychotropic drugs in the dermatology patient: when to start and stop? Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:748-755.

- Gee SN, Zakhary L, Keuthen N, et al. A survey assessment of the recognition and treatment of psychocutaneous disorders in the outpatient dermatology setting: how prepared are we? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:47-52.

Resident Pearl

- Patients often present to dermatology with primary psychologic disorders such as delusional infestation or trichotillomania. Treatment of such conditions with antidepressants and antipsychotics can be highly effective and is within our scope of practice. Increased emphasis on psychopharmacotherapy in dermatology training would increase access to appropriate care for this patient population.

The ABCs of COCs: A Guide for Dermatology Residents on Combined Oral Contraceptives

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

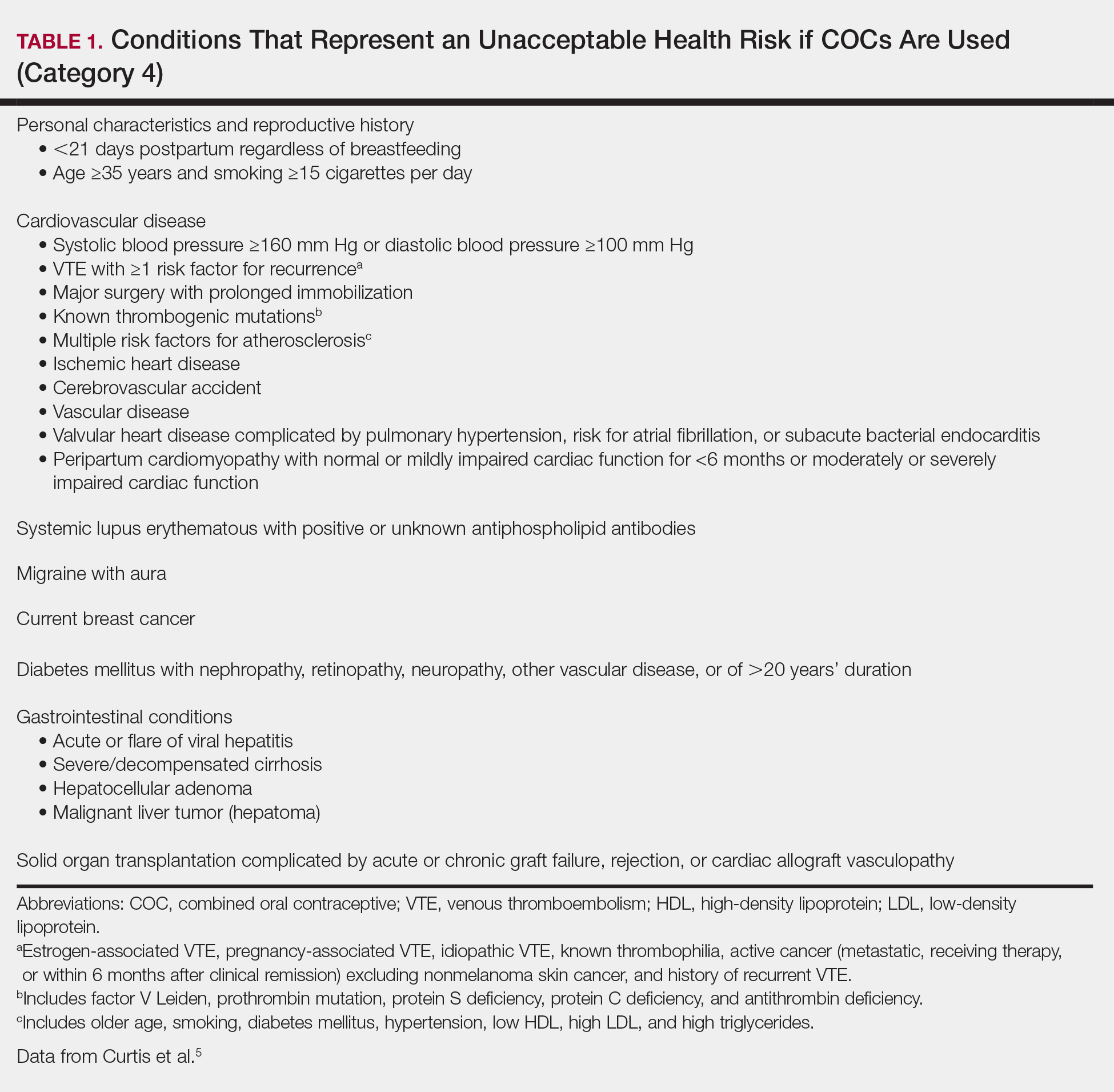

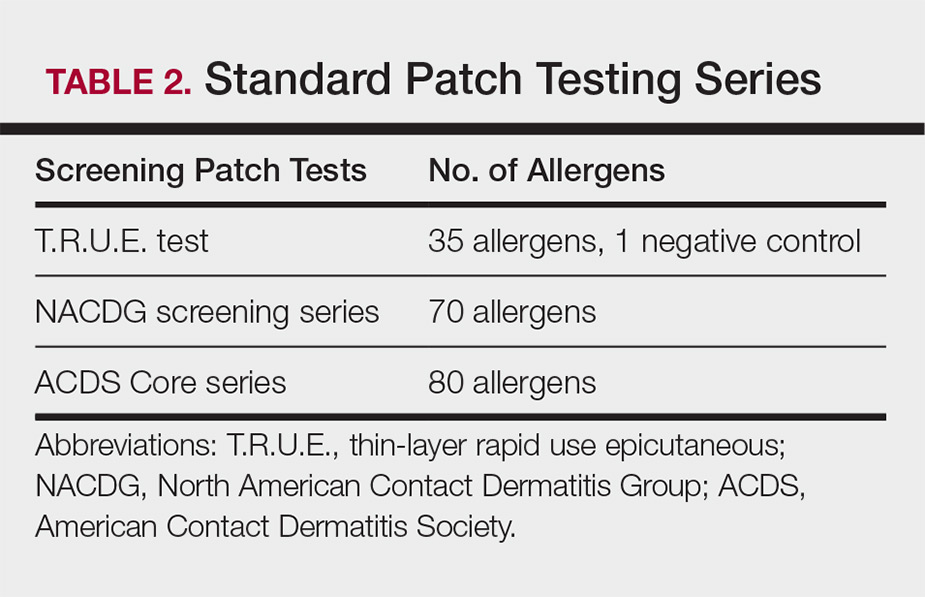

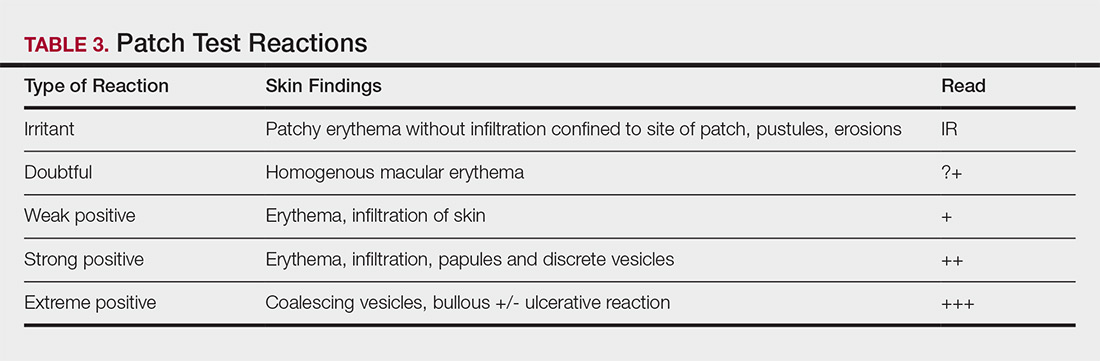

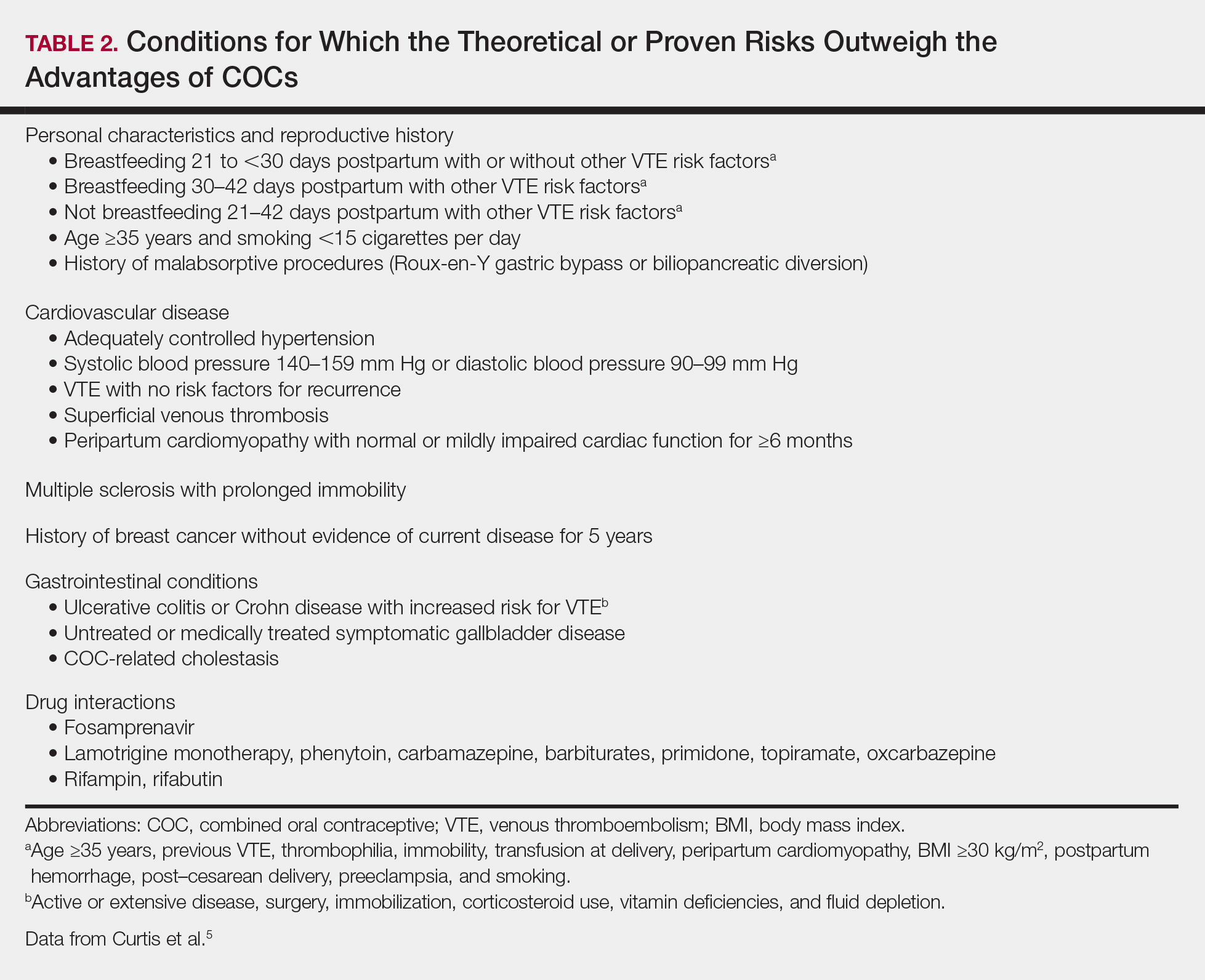

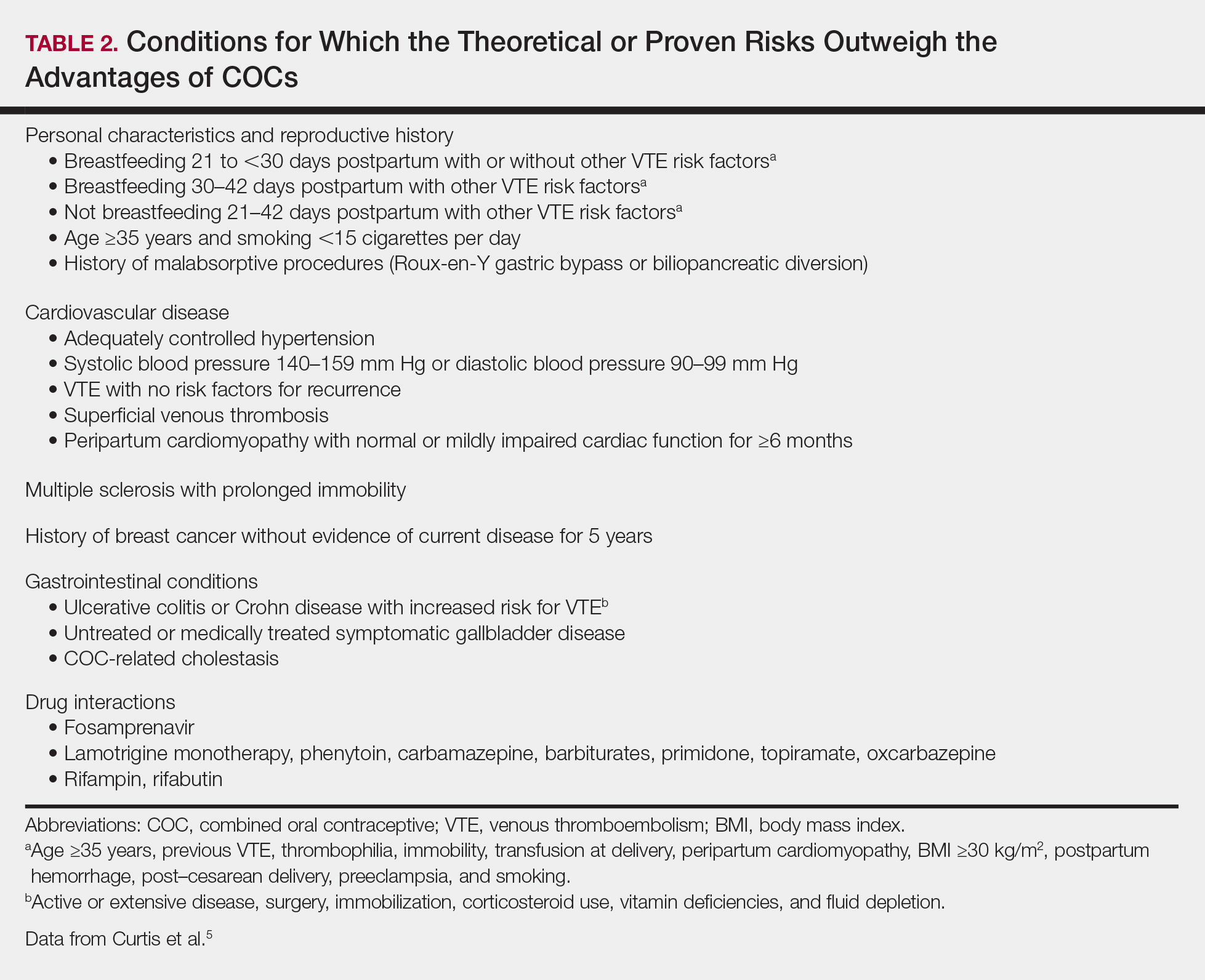

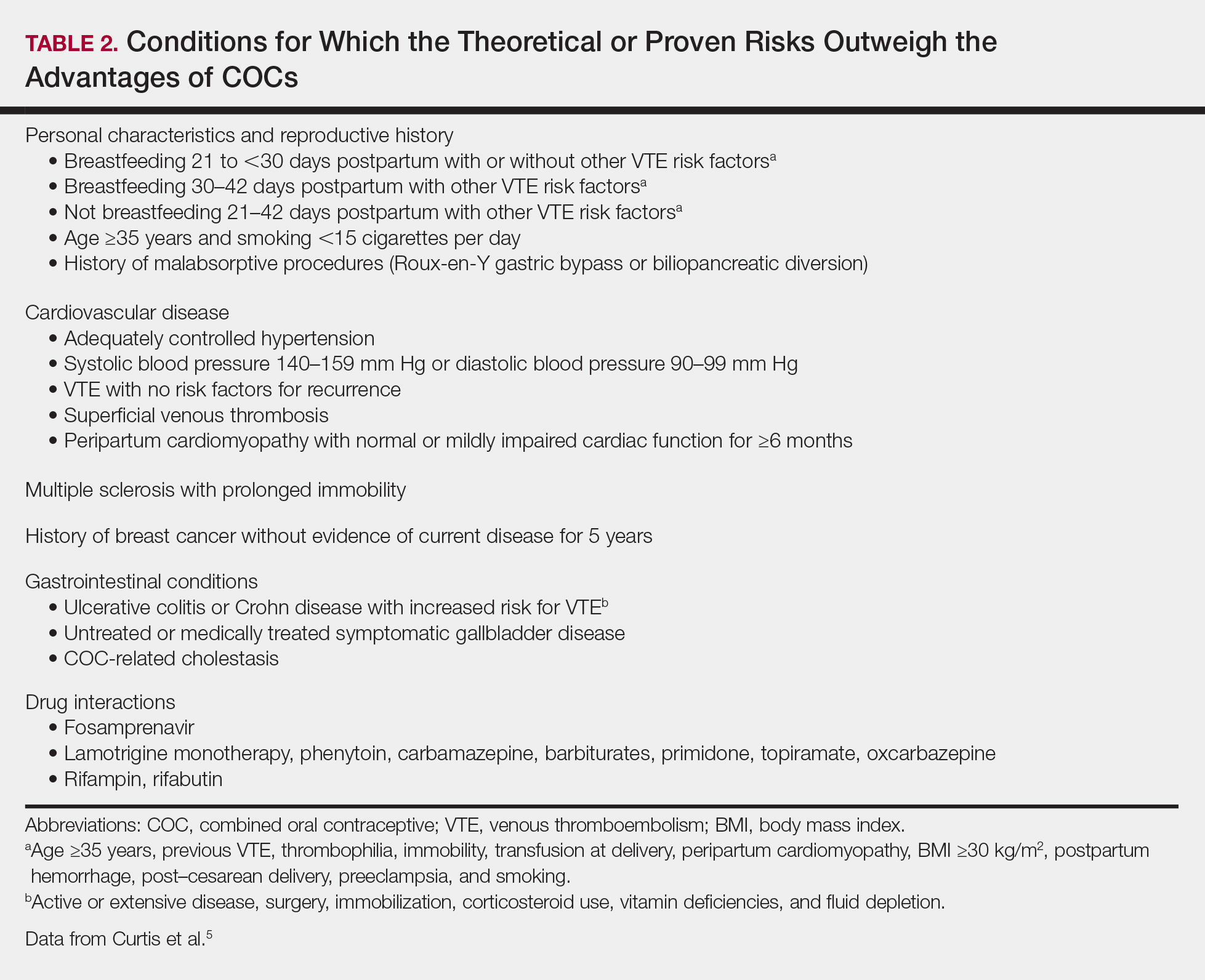

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease

A 2015 Cochrane review found that the risk for myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke is increased 1.6‐fold in COC users.16 Despite this increased relative risk, the increased absolute annual risk of myocardial infarction in nonsmoking women remains low: increased from 0.83 to 3.53 per 10,000,000 women younger than 35 years and from 9.45 to 40.4 per 10,000,000 women 35 years and older.17

Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

Data are mixed on the effect of COCs on the risk for breast cancer and cervical cancer.1 According to the CDC, COC use for 5 or more years might increase the risk of cervical carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in women with persistent human papillomavirus infection.5 Regardless of COC use, women should undergo age-appropriate screening for breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Melasma

Melasma is an estrogen-mediated side effect of COCs.8 A study from 1967 found that 29% of COC users (N=212) developed melasma; however, they were taking COCs with much higher ethinyl estradiol doses (50–100 μg) than typically used today.18 Nevertheless, as part of an overall skin care regimen, photoprotection should be encouraged with a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen that has a sun protection factor of at least 30. In addition, sunscreens with iron oxides have been shown to better prevent melasma relapse by protecting against the shorter wavelengths of visible light.19

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e933.

- Landis ET, Levender MM, Davis SA, et al. Isotretinoin and oral contraceptive use in female acne patients varies by physician specialty: analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:272-277.

- Fitzpatrick L, Mauer E, Chen CL. Oral contraceptives for acne treatment: US dermatologists’ knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices. Cutis. 2017;99:195-201.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003553.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Aust Prescr. 2015;38:6-11.

- McKinney K. Understanding the options: a guide to oral contraceptives. https://www.cecentral.com/assets/2097/022%20Oral%20Contraceptives%2010-26-09.pdf. Published November 5, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2019.

- Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, et al. 20 microg versus >20 microg estrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003989.

- Terki F, Malhotra U. Medical and Service Delivery Guidelines for Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. London, United Kingdom: International Planned Parenthood Federation; 2004.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425.

- Pastor Z, Holla K, Chmel R. The influence of combined oral contraceptives on female sexual desire: a systematic review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2013;18:27-43.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003987.

- Birth control pills for acne: tips from Julie Harper at the Summer AAD. Cutis. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/144550/acne/birth-control-pills-acne-tips-julie-harper-summer-aad. Published August 14, 2017. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- Watson HG, Baglin TP. Guidelines on travel-related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:31-34.

- Roach RE, Helmerhorst FM, Lijfering WM, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD011054.

- Acute myocardial infarction and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international multicentre case-control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1997;349:1202-1209.

- Resnik S. Melasma induced by oral contraceptive drugs. JAMA. 1967;199:601-605.

- Boukari F, Jourdan E, Fontas E, et al. Prevention of melasma relapses with sunscreen combining protection against UV and short wavelengths of visible light: a prospective randomized comparative trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:189-190.e181.

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease

A 2015 Cochrane review found that the risk for myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke is increased 1.6‐fold in COC users.16 Despite this increased relative risk, the increased absolute annual risk of myocardial infarction in nonsmoking women remains low: increased from 0.83 to 3.53 per 10,000,000 women younger than 35 years and from 9.45 to 40.4 per 10,000,000 women 35 years and older.17

Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

Data are mixed on the effect of COCs on the risk for breast cancer and cervical cancer.1 According to the CDC, COC use for 5 or more years might increase the risk of cervical carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in women with persistent human papillomavirus infection.5 Regardless of COC use, women should undergo age-appropriate screening for breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Melasma

Melasma is an estrogen-mediated side effect of COCs.8 A study from 1967 found that 29% of COC users (N=212) developed melasma; however, they were taking COCs with much higher ethinyl estradiol doses (50–100 μg) than typically used today.18 Nevertheless, as part of an overall skin care regimen, photoprotection should be encouraged with a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen that has a sun protection factor of at least 30. In addition, sunscreens with iron oxides have been shown to better prevent melasma relapse by protecting against the shorter wavelengths of visible light.19

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease