User login

Clinical Case-Viewing Sessions in Dermatology: The Patient Perspective

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

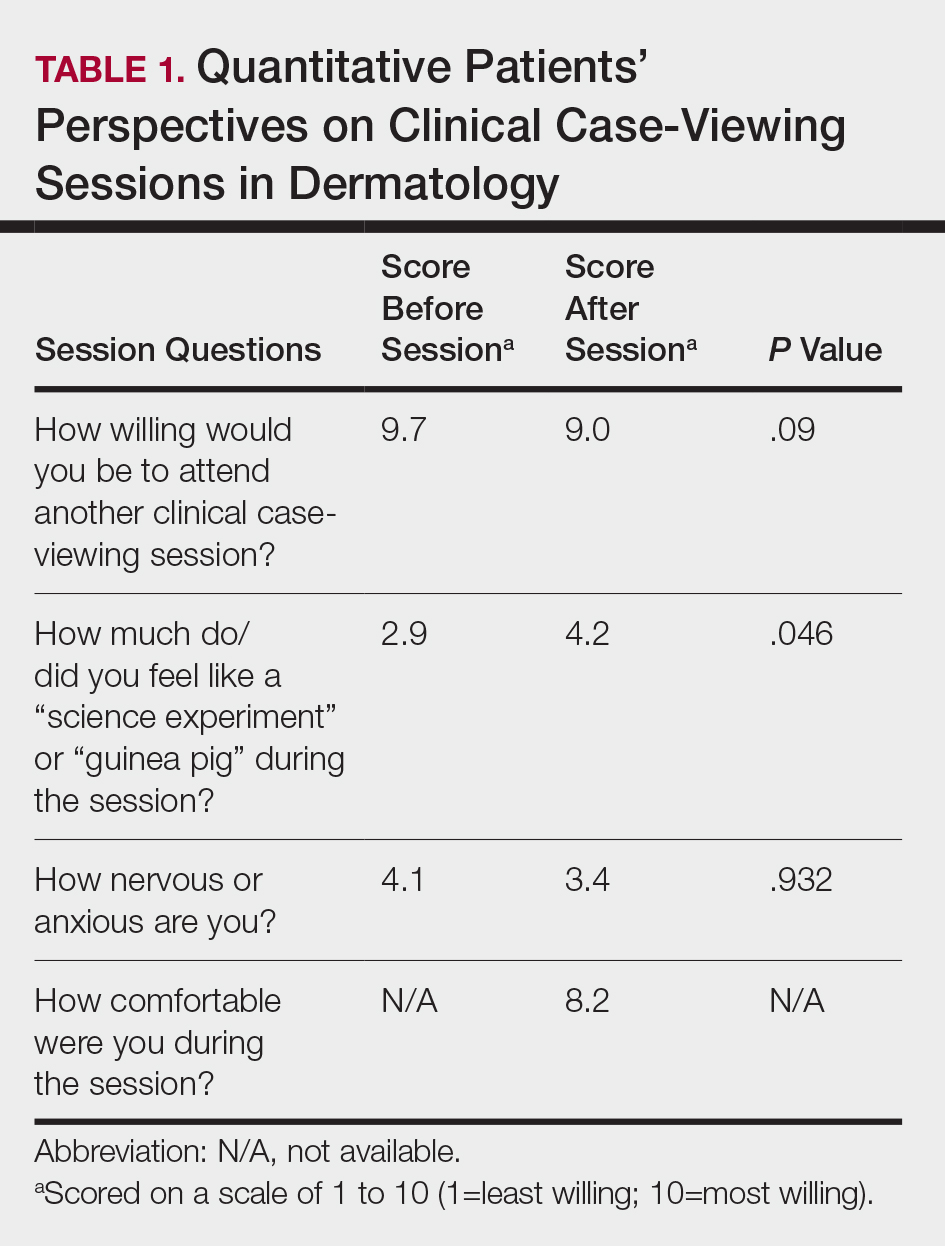

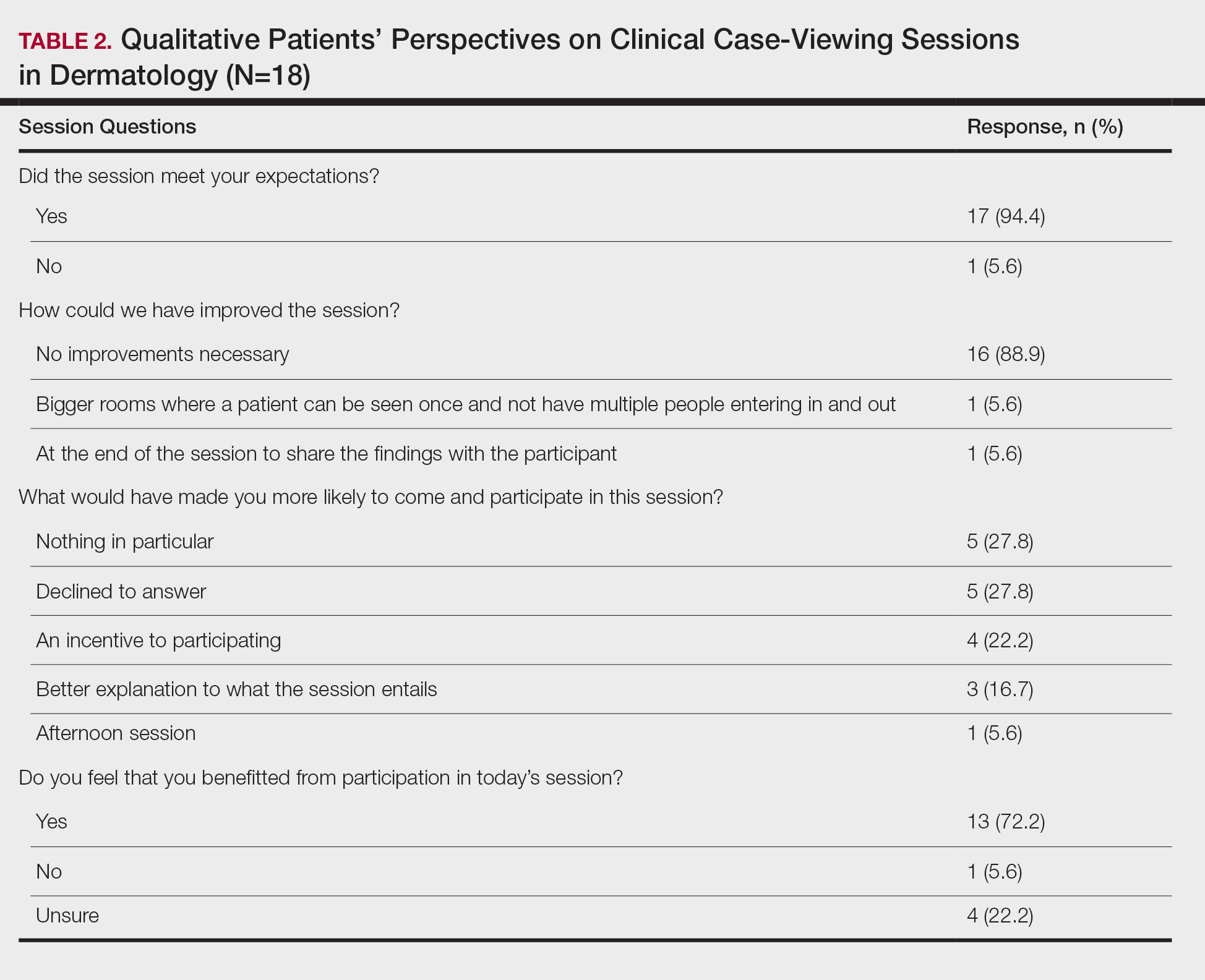

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

To the Editor:

Dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions, commonly referred to as Grand Rounds, are of core educational importance in teaching residents, fellows, and medical students. The traditional format includes the viewing of patient cases followed by resident- and faculty-led group discussions. Clinical case-viewing sessions often involve several health professionals simultaneously observing and interacting with a patient. Although these sessions are highly academically enriching, they may be ill-perceived by patients. The objective of this study was to evaluate patients’ perception of CCV sessions.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) institutional review board and was conducted from February 2017 to August 2017. Following informed consent, 18 patients older than 18 years who were present at the Wake Forest Department of Dermatology CCV sessions were recruited. Patients were each assigned to a private clinical examination room, and CCV attendees briefly visited each room to assess the pathologic findings of interest. Patients received written quantitative surveys before and after the CCV sessions assessing their perspectives on the session (Table 1). Quantitative surveys were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale (1=least willing; 10=most willing). Patients also received qualitative surveys following the session (Table 2). Scores on a 10-item Likert scale were evaluated using a 2-tailed t test.

The mean age of patients was 57.6 years, and women comprised 66.7% (12/18). Patient willingness to attend CCV sessions was relatively unchanged before and after the session, with a mean willingness of 9.7 before the session and 9.0 after the session (P=.09). There was a significant difference in the extent to which patients perceived themselves as experimental subjects prior to the session compared to after the session (2.9 vs 4.2)(P=.046). Following the session, 94.4% (17/18) of patients had the impression that the session met their expectations, and 72.2% (13/18) of patients felt they directly benefitted from the session.

Clinical case-viewing sessions are the foundation of any dermatology residency program1-3; however, characterizing the sessions’ psychosocial implications on patients is important too. Although some patients did feel part of a “science experiment,” this finding may be of less importance, as patients generally considered the sessions to be a positive experience and were willing to take part again.

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. All participants were patients at a single center, which may limit the generalization of the results, in addition to the small sample size. Clinical case-viewing sessions also are conducted slightly differently between dermatology programs, which may further limit the generalization of the results. Future studies may aim to assess varying CCV formats to optimize both medical education as well as patient satisfaction.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

- Mehrabi D, Cruz PD Jr. Educational conferences in dermatology residency programs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:523-524.

- Hull AL, Cullen RJ, Hekelman FP. A retrospective analysis of grand rounds in continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1989;9:257-266.

- Cruz PD Jr, Chaker MB. Teaching conferences in dermatology residency programs revisited. J Am Acad of Dermatol. 1995;32:675-677.

Practice Points

- Patient willingness to attend dermatology clinical case-viewing (CCV) sessions is relatively unchanged before and after the session.

- Participants generally consider CCV sessions to be a positive experience.

Handoffs in Dermatology Residency

As a dermatologist, there are innumerable items to track after each patient encounter, such as results from biopsies, laboratory tests, cultures, and imaging, as well as ensuring follow-up with providers in other specialties. In residency, there is the complicating factor of switching rotations and therefore transitioning care to different providers (Figure). Ensuring organized handoff practices is especially important in residency. In a study of malpractice claims involving residents, handoff problems were a notable contributing factor in 19% of malpractice cases involving residents vs 13% of cases involving attending physicians.1 There still is a high percentage of malpractice cases involving handoff problems among attending physicians, highlighting the fact that these issues persist beyond residency.

This article will review a variety of handoff and organizational practices that dermatology residents currently use, discuss the evidence behind best practices, and highlight additional considerations relevant when selecting organizational tools.

Varied Practices

Based on personal discussions with residents from 7 dermatology residency programs across the country, there is marked variability in both the frequency of handoffs and organizational methods utilized. Two major factors that dictate these practices are the structure of the residency program and electronic health record (EHR) capacities.

Program structure and allocation of resident responsibilities affect the frequency of handoffs in the outpatient dermatology residency setting. In some programs, residents are responsible for all pending studies for patients they have seen, even after switching clinical sites. In other programs, residents sign out patients, including pending test results, when transitioning from one clinical rotation to another. The frequency of these handoffs varies, ranging from every few weeks to every 4 months.

Many dermatology residents report utilizing features in the EHR to organize outstanding tasks and results, obviating the need for additional documentation. Some EHRs have the capacity to assign proxies, which allows for a seamless transition to another provider. When the EHR lacks these capabilities, organization of outstanding tasks relies more heavily on supplemental documentation. Residents noted using spreadsheets, typed documents, electronic applications designed to organize handoffs outside of the EHR, and handwritten notes.

There is room for formal education on the best handoff and organizational practices in dermatology residency. A study of anesthesiology residents at a major academic institution suggested that education regarding sign-out practices is most effective when it is multimodal, using both formal and informal methods.2 Based on my discussions with other dermatology residents, these practices generally are informally learned; often, dermatology residents did not realize that organization practices varied so widely at other institutions.

Evidence Behind Handoff Practices

There are data in the dermatology literature to support utilizing electronic means for handoff practices. At a tertiary dermatology department in Melbourne, Australia, providers created a novel electronic handover system using Microsoft programs to be used alongside the main hospital EHR to help practitioners keep track of outpatient studies.3 An audit of this system demonstrated that its use provided a reliable system for follow-up on all outpatient results, with benefits in clinical, organizational, and health research domains.4 The investigators noted that residents, registrars, nurses, and consultants utilized the electronic handover system, with residents completing 90% of all tasks.3 Similarly, several residents I spoke with personally cited using Listrunner (www.listrunnerapp.com), a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant electronic tool outside of the EHR designed for collaborative management of patient lists.

Outside of the dermatology literature, resident handoff in the outpatient setting mainly has been studied in the primary care year-end transition of care, with findings that are certainly relevant to dermatology residency. Pincavage et al5 performed a targeted literature search on year-end handoff practices, and Donnelly et al6 studied internal medicine residents in an outpatient ambulatory clinic; both supported implementing a standardized process for sign-out. Pincavage et al5 also recommended focusing on high-risk patients, educating residents on handoff practices, preparing patients for the transition, and performing safety audits. Donnelly et al6 found that providing time dedicated to patient handoff and clear expectations improved handoff practices.

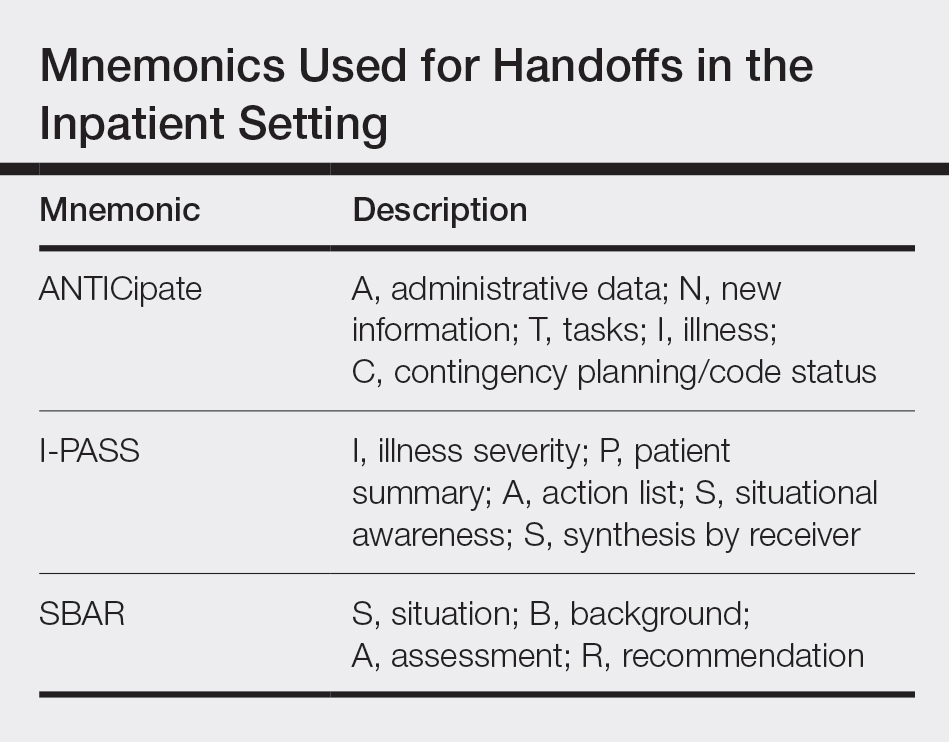

There is extensive literature on handoff practices in the inpatient setting sparked by an increasing number of handoffs after the implementation of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour restrictions in 1989. Some of the guiding principles may be applied to the outpatient dermatology setting. Many residents may be familiar with mnemonics that have been developed to organize content during sign-out, which have been s

Other Considerations

An important consideration during patient handoffs is security, especially when implementing documentation and tools outside of the EHR. It is important for providers to be compliant with institutional policies as well as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and ensure protection against cyberattacks, which have been on the rise; 83% of 1300 physicians surveyed have been the victim of a cyberattack.9 Providers also should be mindful of redundancies in organizational and handoff practices. Multiple methods for keeping track of information helps ensure that important results do not fall through the cracks. However, too many redundancies may be wasteful of a practice’s resources and providers’ time.

Final Thoughts

There are varied practices regarding organization of handoff and follow-up. Residency should serve as an opportunity for physicians to become familiar with different practices. Becoming familiar with the varied options may be helpful to take forward in one’s career, especially given that dermatologists may enter a work setting postresidency with practices that are different from where they trained. Additionally, given rapid shifts in technologies, providers must change how they stay organized. This evolving landscape provides an opportunity for the next generation of dermatologists to take leadership to shape the future of organizational practices.

- Singh H, Thomas EJ, Petersen LA, et al. Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2030-2036.

- Muralidharan M, Clapp JT, Pulos BP, et al. How does training in anesthesia residency shape residents’ approaches to patient care handoffs? a single-center qualitative interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:271.

- Poon F, Martyres R, Denahy A, et al. Improving patient safety: the impact of an outpatients’ electronic handover system in a tertiary dermatology department. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:E183-E188.

- Listrunner website. https://www.listrunnerapp.com. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Pincavage AT, Donnelly MJ, Young JQ, et al. Year-end resident clinic handoffs: narrative review and recommendations for improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:71-79.

- Donnelly MJ, Clauser JM, Weissman NJ. An intervention to improve ambulatory care handoffs at the end of residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:381-384.

- Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, et al. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign-out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:257-266.

- Breaux J, Mclendon R, Stedman RB, et al. Developing a standardized and sustainable resident sign-out process: an AIAMC National Initiative IV Project. Ochsner J. 2014;14:563-568.

- American Medical Association and Accenture. Taking the physician’s pulse: tackling cyber threats in healthcare. https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/accenture/conversion-assets/dotcom/documents/local/en/accenture-health-taking-the-physicians-pulse.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

As a dermatologist, there are innumerable items to track after each patient encounter, such as results from biopsies, laboratory tests, cultures, and imaging, as well as ensuring follow-up with providers in other specialties. In residency, there is the complicating factor of switching rotations and therefore transitioning care to different providers (Figure). Ensuring organized handoff practices is especially important in residency. In a study of malpractice claims involving residents, handoff problems were a notable contributing factor in 19% of malpractice cases involving residents vs 13% of cases involving attending physicians.1 There still is a high percentage of malpractice cases involving handoff problems among attending physicians, highlighting the fact that these issues persist beyond residency.

This article will review a variety of handoff and organizational practices that dermatology residents currently use, discuss the evidence behind best practices, and highlight additional considerations relevant when selecting organizational tools.

Varied Practices

Based on personal discussions with residents from 7 dermatology residency programs across the country, there is marked variability in both the frequency of handoffs and organizational methods utilized. Two major factors that dictate these practices are the structure of the residency program and electronic health record (EHR) capacities.

Program structure and allocation of resident responsibilities affect the frequency of handoffs in the outpatient dermatology residency setting. In some programs, residents are responsible for all pending studies for patients they have seen, even after switching clinical sites. In other programs, residents sign out patients, including pending test results, when transitioning from one clinical rotation to another. The frequency of these handoffs varies, ranging from every few weeks to every 4 months.

Many dermatology residents report utilizing features in the EHR to organize outstanding tasks and results, obviating the need for additional documentation. Some EHRs have the capacity to assign proxies, which allows for a seamless transition to another provider. When the EHR lacks these capabilities, organization of outstanding tasks relies more heavily on supplemental documentation. Residents noted using spreadsheets, typed documents, electronic applications designed to organize handoffs outside of the EHR, and handwritten notes.

There is room for formal education on the best handoff and organizational practices in dermatology residency. A study of anesthesiology residents at a major academic institution suggested that education regarding sign-out practices is most effective when it is multimodal, using both formal and informal methods.2 Based on my discussions with other dermatology residents, these practices generally are informally learned; often, dermatology residents did not realize that organization practices varied so widely at other institutions.

Evidence Behind Handoff Practices

There are data in the dermatology literature to support utilizing electronic means for handoff practices. At a tertiary dermatology department in Melbourne, Australia, providers created a novel electronic handover system using Microsoft programs to be used alongside the main hospital EHR to help practitioners keep track of outpatient studies.3 An audit of this system demonstrated that its use provided a reliable system for follow-up on all outpatient results, with benefits in clinical, organizational, and health research domains.4 The investigators noted that residents, registrars, nurses, and consultants utilized the electronic handover system, with residents completing 90% of all tasks.3 Similarly, several residents I spoke with personally cited using Listrunner (www.listrunnerapp.com), a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant electronic tool outside of the EHR designed for collaborative management of patient lists.

Outside of the dermatology literature, resident handoff in the outpatient setting mainly has been studied in the primary care year-end transition of care, with findings that are certainly relevant to dermatology residency. Pincavage et al5 performed a targeted literature search on year-end handoff practices, and Donnelly et al6 studied internal medicine residents in an outpatient ambulatory clinic; both supported implementing a standardized process for sign-out. Pincavage et al5 also recommended focusing on high-risk patients, educating residents on handoff practices, preparing patients for the transition, and performing safety audits. Donnelly et al6 found that providing time dedicated to patient handoff and clear expectations improved handoff practices.

There is extensive literature on handoff practices in the inpatient setting sparked by an increasing number of handoffs after the implementation of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour restrictions in 1989. Some of the guiding principles may be applied to the outpatient dermatology setting. Many residents may be familiar with mnemonics that have been developed to organize content during sign-out, which have been s

Other Considerations

An important consideration during patient handoffs is security, especially when implementing documentation and tools outside of the EHR. It is important for providers to be compliant with institutional policies as well as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and ensure protection against cyberattacks, which have been on the rise; 83% of 1300 physicians surveyed have been the victim of a cyberattack.9 Providers also should be mindful of redundancies in organizational and handoff practices. Multiple methods for keeping track of information helps ensure that important results do not fall through the cracks. However, too many redundancies may be wasteful of a practice’s resources and providers’ time.

Final Thoughts

There are varied practices regarding organization of handoff and follow-up. Residency should serve as an opportunity for physicians to become familiar with different practices. Becoming familiar with the varied options may be helpful to take forward in one’s career, especially given that dermatologists may enter a work setting postresidency with practices that are different from where they trained. Additionally, given rapid shifts in technologies, providers must change how they stay organized. This evolving landscape provides an opportunity for the next generation of dermatologists to take leadership to shape the future of organizational practices.

As a dermatologist, there are innumerable items to track after each patient encounter, such as results from biopsies, laboratory tests, cultures, and imaging, as well as ensuring follow-up with providers in other specialties. In residency, there is the complicating factor of switching rotations and therefore transitioning care to different providers (Figure). Ensuring organized handoff practices is especially important in residency. In a study of malpractice claims involving residents, handoff problems were a notable contributing factor in 19% of malpractice cases involving residents vs 13% of cases involving attending physicians.1 There still is a high percentage of malpractice cases involving handoff problems among attending physicians, highlighting the fact that these issues persist beyond residency.

This article will review a variety of handoff and organizational practices that dermatology residents currently use, discuss the evidence behind best practices, and highlight additional considerations relevant when selecting organizational tools.

Varied Practices

Based on personal discussions with residents from 7 dermatology residency programs across the country, there is marked variability in both the frequency of handoffs and organizational methods utilized. Two major factors that dictate these practices are the structure of the residency program and electronic health record (EHR) capacities.

Program structure and allocation of resident responsibilities affect the frequency of handoffs in the outpatient dermatology residency setting. In some programs, residents are responsible for all pending studies for patients they have seen, even after switching clinical sites. In other programs, residents sign out patients, including pending test results, when transitioning from one clinical rotation to another. The frequency of these handoffs varies, ranging from every few weeks to every 4 months.

Many dermatology residents report utilizing features in the EHR to organize outstanding tasks and results, obviating the need for additional documentation. Some EHRs have the capacity to assign proxies, which allows for a seamless transition to another provider. When the EHR lacks these capabilities, organization of outstanding tasks relies more heavily on supplemental documentation. Residents noted using spreadsheets, typed documents, electronic applications designed to organize handoffs outside of the EHR, and handwritten notes.

There is room for formal education on the best handoff and organizational practices in dermatology residency. A study of anesthesiology residents at a major academic institution suggested that education regarding sign-out practices is most effective when it is multimodal, using both formal and informal methods.2 Based on my discussions with other dermatology residents, these practices generally are informally learned; often, dermatology residents did not realize that organization practices varied so widely at other institutions.

Evidence Behind Handoff Practices

There are data in the dermatology literature to support utilizing electronic means for handoff practices. At a tertiary dermatology department in Melbourne, Australia, providers created a novel electronic handover system using Microsoft programs to be used alongside the main hospital EHR to help practitioners keep track of outpatient studies.3 An audit of this system demonstrated that its use provided a reliable system for follow-up on all outpatient results, with benefits in clinical, organizational, and health research domains.4 The investigators noted that residents, registrars, nurses, and consultants utilized the electronic handover system, with residents completing 90% of all tasks.3 Similarly, several residents I spoke with personally cited using Listrunner (www.listrunnerapp.com), a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant electronic tool outside of the EHR designed for collaborative management of patient lists.

Outside of the dermatology literature, resident handoff in the outpatient setting mainly has been studied in the primary care year-end transition of care, with findings that are certainly relevant to dermatology residency. Pincavage et al5 performed a targeted literature search on year-end handoff practices, and Donnelly et al6 studied internal medicine residents in an outpatient ambulatory clinic; both supported implementing a standardized process for sign-out. Pincavage et al5 also recommended focusing on high-risk patients, educating residents on handoff practices, preparing patients for the transition, and performing safety audits. Donnelly et al6 found that providing time dedicated to patient handoff and clear expectations improved handoff practices.

There is extensive literature on handoff practices in the inpatient setting sparked by an increasing number of handoffs after the implementation of Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education duty hour restrictions in 1989. Some of the guiding principles may be applied to the outpatient dermatology setting. Many residents may be familiar with mnemonics that have been developed to organize content during sign-out, which have been s

Other Considerations

An important consideration during patient handoffs is security, especially when implementing documentation and tools outside of the EHR. It is important for providers to be compliant with institutional policies as well as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and ensure protection against cyberattacks, which have been on the rise; 83% of 1300 physicians surveyed have been the victim of a cyberattack.9 Providers also should be mindful of redundancies in organizational and handoff practices. Multiple methods for keeping track of information helps ensure that important results do not fall through the cracks. However, too many redundancies may be wasteful of a practice’s resources and providers’ time.

Final Thoughts

There are varied practices regarding organization of handoff and follow-up. Residency should serve as an opportunity for physicians to become familiar with different practices. Becoming familiar with the varied options may be helpful to take forward in one’s career, especially given that dermatologists may enter a work setting postresidency with practices that are different from where they trained. Additionally, given rapid shifts in technologies, providers must change how they stay organized. This evolving landscape provides an opportunity for the next generation of dermatologists to take leadership to shape the future of organizational practices.

- Singh H, Thomas EJ, Petersen LA, et al. Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2030-2036.

- Muralidharan M, Clapp JT, Pulos BP, et al. How does training in anesthesia residency shape residents’ approaches to patient care handoffs? a single-center qualitative interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:271.

- Poon F, Martyres R, Denahy A, et al. Improving patient safety: the impact of an outpatients’ electronic handover system in a tertiary dermatology department. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:E183-E188.

- Listrunner website. https://www.listrunnerapp.com. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Pincavage AT, Donnelly MJ, Young JQ, et al. Year-end resident clinic handoffs: narrative review and recommendations for improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:71-79.

- Donnelly MJ, Clauser JM, Weissman NJ. An intervention to improve ambulatory care handoffs at the end of residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:381-384.

- Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, et al. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign-out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:257-266.

- Breaux J, Mclendon R, Stedman RB, et al. Developing a standardized and sustainable resident sign-out process: an AIAMC National Initiative IV Project. Ochsner J. 2014;14:563-568.

- American Medical Association and Accenture. Taking the physician’s pulse: tackling cyber threats in healthcare. https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/accenture/conversion-assets/dotcom/documents/local/en/accenture-health-taking-the-physicians-pulse.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Singh H, Thomas EJ, Petersen LA, et al. Medical errors involving trainees: a study of closed malpractice claims from 5 insurers. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2030-2036.

- Muralidharan M, Clapp JT, Pulos BP, et al. How does training in anesthesia residency shape residents’ approaches to patient care handoffs? a single-center qualitative interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:271.

- Poon F, Martyres R, Denahy A, et al. Improving patient safety: the impact of an outpatients’ electronic handover system in a tertiary dermatology department. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59:E183-E188.

- Listrunner website. https://www.listrunnerapp.com. Accessed January 30, 2020.

- Pincavage AT, Donnelly MJ, Young JQ, et al. Year-end resident clinic handoffs: narrative review and recommendations for improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43:71-79.

- Donnelly MJ, Clauser JM, Weissman NJ. An intervention to improve ambulatory care handoffs at the end of residency. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4:381-384.

- Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, et al. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign-out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:257-266.

- Breaux J, Mclendon R, Stedman RB, et al. Developing a standardized and sustainable resident sign-out process: an AIAMC National Initiative IV Project. Ochsner J. 2014;14:563-568.

- American Medical Association and Accenture. Taking the physician’s pulse: tackling cyber threats in healthcare. https://www.accenture.com/_acnmedia/accenture/conversion-assets/dotcom/documents/local/en/accenture-health-taking-the-physicians-pulse.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2020.

Resident Pearl

- For dermatology residents, ensuring organized handoff and follow-up practices is essential. Residency provides an opportunity to become familiar with different practices to take forward in one’s career.

Top Residents Selected for 2020 dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™

The dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ was presented to 5 dermatology residents at the 19th Annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, January 21–25, 2020, in Paradise Island, Bahamas. Recipients of the award include Rachel Giesey, DO, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio; Janice Tiao, MD, Boston University Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; Jordan V. Wang, MD, MBE, MBA, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Jacqueline D. Watchmaker, MD, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; and Jennifer E. Yeh, MD, PhD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. The residents presented their research during the general sessions on January 25, 2020.

The overall grand prize was awarded to Dr. Yeh for her research entitled, “Topical Imiquimod in Combination With Brachytherapy for Unresectable Cutaneous Melanoma Metastases.” Dr. Yeh presented the utility of combining topical imiquimod with brachytherapy for locoregional control of cutaneous metastases through the presentation of 3 patients with scalp melanoma initially treated with wide local excision who developed numerous cutaneous metastases. “While surgical excision is the first-line treatment of single, discrete cutaneous metastases, it may not be practical in patients with multiple foci of disease distributed over large areas, as seen in the 3 patients presented here who achieved complete resolution of their cutaneous metastatic burden with concurrent topical imiquimod and brachytherapy,” Dr. Yeh reported.

Presentations by the other residents included a study of the burden of common skin diseases in the Caribbean and the potential correlation with a country’s socioeconomic status (Dr. Giesey), a study of the use of doxycycline in patients with lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia (Dr. Tiao), a discussion of counterfeit medical devices and injectables as well as medical spas in dermatology (Dr. Wang), and a study of the most common reasons patients are dissatisfied with minimally and noninvasive cosmetic procedures (Dr. Watchmaker). Access all of the abstracts presented by the top residents here.

The dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ recognizes top residents in dermatology. DermMentors.org and the dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ are sponsored by Beiersdorf Inc and administered by DermEd, Inc. The 2020 dermMentors™ Residents of Distinction™ presented new scientific research during the general sessions of the 19th Annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium on January 25, 2020.

The dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ was presented to 5 dermatology residents at the 19th Annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, January 21–25, 2020, in Paradise Island, Bahamas. Recipients of the award include Rachel Giesey, DO, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio; Janice Tiao, MD, Boston University Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; Jordan V. Wang, MD, MBE, MBA, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Jacqueline D. Watchmaker, MD, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; and Jennifer E. Yeh, MD, PhD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. The residents presented their research during the general sessions on January 25, 2020.

The overall grand prize was awarded to Dr. Yeh for her research entitled, “Topical Imiquimod in Combination With Brachytherapy for Unresectable Cutaneous Melanoma Metastases.” Dr. Yeh presented the utility of combining topical imiquimod with brachytherapy for locoregional control of cutaneous metastases through the presentation of 3 patients with scalp melanoma initially treated with wide local excision who developed numerous cutaneous metastases. “While surgical excision is the first-line treatment of single, discrete cutaneous metastases, it may not be practical in patients with multiple foci of disease distributed over large areas, as seen in the 3 patients presented here who achieved complete resolution of their cutaneous metastatic burden with concurrent topical imiquimod and brachytherapy,” Dr. Yeh reported.

Presentations by the other residents included a study of the burden of common skin diseases in the Caribbean and the potential correlation with a country’s socioeconomic status (Dr. Giesey), a study of the use of doxycycline in patients with lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia (Dr. Tiao), a discussion of counterfeit medical devices and injectables as well as medical spas in dermatology (Dr. Wang), and a study of the most common reasons patients are dissatisfied with minimally and noninvasive cosmetic procedures (Dr. Watchmaker). Access all of the abstracts presented by the top residents here.

The dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ recognizes top residents in dermatology. DermMentors.org and the dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ are sponsored by Beiersdorf Inc and administered by DermEd, Inc. The 2020 dermMentors™ Residents of Distinction™ presented new scientific research during the general sessions of the 19th Annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium on January 25, 2020.

The dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ was presented to 5 dermatology residents at the 19th Annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium, January 21–25, 2020, in Paradise Island, Bahamas. Recipients of the award include Rachel Giesey, DO, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio, and University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center, Cleveland, Ohio; Janice Tiao, MD, Boston University Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; Jordan V. Wang, MD, MBE, MBA, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Jacqueline D. Watchmaker, MD, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; and Jennifer E. Yeh, MD, PhD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts. The residents presented their research during the general sessions on January 25, 2020.

The overall grand prize was awarded to Dr. Yeh for her research entitled, “Topical Imiquimod in Combination With Brachytherapy for Unresectable Cutaneous Melanoma Metastases.” Dr. Yeh presented the utility of combining topical imiquimod with brachytherapy for locoregional control of cutaneous metastases through the presentation of 3 patients with scalp melanoma initially treated with wide local excision who developed numerous cutaneous metastases. “While surgical excision is the first-line treatment of single, discrete cutaneous metastases, it may not be practical in patients with multiple foci of disease distributed over large areas, as seen in the 3 patients presented here who achieved complete resolution of their cutaneous metastatic burden with concurrent topical imiquimod and brachytherapy,” Dr. Yeh reported.

Presentations by the other residents included a study of the burden of common skin diseases in the Caribbean and the potential correlation with a country’s socioeconomic status (Dr. Giesey), a study of the use of doxycycline in patients with lichen planopilaris and frontal fibrosing alopecia (Dr. Tiao), a discussion of counterfeit medical devices and injectables as well as medical spas in dermatology (Dr. Wang), and a study of the most common reasons patients are dissatisfied with minimally and noninvasive cosmetic procedures (Dr. Watchmaker). Access all of the abstracts presented by the top residents here.

The dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ recognizes top residents in dermatology. DermMentors.org and the dermMentors™ Resident of Distinction Award™ are sponsored by Beiersdorf Inc and administered by DermEd, Inc. The 2020 dermMentors™ Residents of Distinction™ presented new scientific research during the general sessions of the 19th Annual Caribbean Dermatology Symposium on January 25, 2020.

The Lowdown on Low-Dose Naltrexone

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) has shown efficacy in off-label treatment of a variety of inflammatory diseases ranging from Crohn disease to multiple sclerosis.1 There are limited data about the use of LDN in dermatology, but reports regarding how it works as an anti-inflammatory agent have been published.1,2

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that originally was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat addiction to alcohol, opiates, and heroin.2 The dose of naltrexone to treat addiction ranges from 50 to 100 mg/d, and at these levels the effects of opioids are blocked for 24 hours; however, the dosing for LDN is much lower, ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 mg/d.3 At this low dose, naltrexone partially binds to various opioid receptors, leading to a temporary blockade.4 One of the downstream effects of this opioid receptor blockade is a paradoxical increase in endogenous endorphins.3

In addition to opioid blockage, lower doses of naltrexone have anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting nonopioid receptors. Naltrexone blocks toll-like receptor 4, which is found on keratinocytes and also on macrophages such as microglia.5 These macrophages also contain inflammatory compounds such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-6. Low-dose naltrexone can suppress levels of these inflammatory markers. It is important to note that these anti-inflammatory effects have not been observed at the standard higher doses of naltrexone.1

When to Use

Low-dose naltrexone is a treatment option for inflammatory dermatologic conditions. A recent review of the literature outlined the use of LDN in a variety of inflammatory skin conditions. Improvement was noted in patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, lichen planopilaris, and various types of pruritus (ie, aquagenic, cholestatic, uremic, atopic dermatitis related).3 A case report of LDN successfully treating a patient with psoriasis also has been published.6 We often use LDN at the University of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin) to treat patients with psoriasis. Ekelem et al3 also discussed patients with skin conditions that either had no response or worsened with naltrexone treatment, including various types of pruritus (ie, uremic, mycosis fungoides related, other causes of pruritus). Importantly, in the majority of cases without an improved response, the dose used was 50 mg/d.3 Higher doses of naltrexone are not known to have anti-inflammatory effects.

Low-dose naltrexone can be considered as a treatment option in patients with contraindications to other systemic anti-inflammatory treatments; for example, patients with a history of malignancy may prefer to avoid treatment with biologic agents. Low-dose naltrexone also can be considered as a treatment option in patients who are uncomfortable with the side-effect profiles of other systemic anti-inflammatory treatments, such as the risk for leukemias and lymphomas associated with biologic agents, the risk for liver toxicity with methotrexate, or the risk for hyperlipidemia with acitretin.

How to Monitor

The following monitoring information is adapted from the practice of Apple Bodemer, MD, a board-certified dermatologist at the University of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin) who also is fellowship trained in integrative medicine.

There is a paucity of published data about LDN dosing for inflammatory skin diseases. However, prescribers should be aware that LDN can alter thyroid hormone levels, especially in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. If a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level within reference range has not been noted in the last year, consider screening with a TSH test and also assessing for a personal or family history of thyroid disease. If the TSH level is within reference range, there generally is no need to monitor while treating with LDN. Consider checking TSH levels every 4 months in patients with thyroid disease while they are on LDN therapy and be sure to educate them about symptoms of hyperthyroidism.

Side Effects

Low-dose naltrexone has a minimal side-effect profile with self-limited side effects that often resolve within approximately 1 week. One of the most commonly reported side effects is sleep disturbance with vivid dreams, which has been reported in 37% of participants.1 If your patients experience this side effect, you can reassure them that it improves with time. You also can switch to morning dosing to try and alleviate sleep disturbances at night. Another possible side effect is gastrointestinal tract upset. Importantly, there is no known abuse potential for LDN.1 To stop LDN, patients should be stable for 6 to 12 months, and there is no need to wean them off it.

Cost and Availability

Because use of LDN in dermatology is considered off label and it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat any medical conditions, it must be prescribed through a compounding pharmacy, usually without insurance coverage. The monthly cost is approximately $30 depending on the pharmacy (unpublished data), which may be cost prohibitive for patients, so it is important to counsel them about price

Final Thoughts

Low-dose naltrexone is an alternative treatment option that can be considered in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. It has a favorable side-effect profile, especially compared to other systemic anti-inflammatory agents; however, additional studies are needed to learn more about its safety and efficacy. If patients ask you about LDN, the information provided here can guide you with how it works and how to prescribe it.

- Younger J, Parkitny L, McLain D. The use of low-dose naltrexone (LDN) as a novel anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:451-459.

- Brown N, Panksepp J. Low-dose naltrexone for disease prevention and quality of life. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:333-337.

- Ekelem C, Juhasz M, Khera P, et al. Utility of naltrexone treatment for chronic inflammatory dermatologic conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:229-236.

- Bihari B. Efficacy of low dose naltrexone as an immune stabilizing agent for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care. 1995;9:3.

- Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions [published online December 21, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1746-1752.

- Bridgman AC, Kirchhof MG. Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris using low-dose naltrexone. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:827-829.

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) has shown efficacy in off-label treatment of a variety of inflammatory diseases ranging from Crohn disease to multiple sclerosis.1 There are limited data about the use of LDN in dermatology, but reports regarding how it works as an anti-inflammatory agent have been published.1,2

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that originally was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat addiction to alcohol, opiates, and heroin.2 The dose of naltrexone to treat addiction ranges from 50 to 100 mg/d, and at these levels the effects of opioids are blocked for 24 hours; however, the dosing for LDN is much lower, ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 mg/d.3 At this low dose, naltrexone partially binds to various opioid receptors, leading to a temporary blockade.4 One of the downstream effects of this opioid receptor blockade is a paradoxical increase in endogenous endorphins.3

In addition to opioid blockage, lower doses of naltrexone have anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting nonopioid receptors. Naltrexone blocks toll-like receptor 4, which is found on keratinocytes and also on macrophages such as microglia.5 These macrophages also contain inflammatory compounds such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-6. Low-dose naltrexone can suppress levels of these inflammatory markers. It is important to note that these anti-inflammatory effects have not been observed at the standard higher doses of naltrexone.1

When to Use

Low-dose naltrexone is a treatment option for inflammatory dermatologic conditions. A recent review of the literature outlined the use of LDN in a variety of inflammatory skin conditions. Improvement was noted in patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, lichen planopilaris, and various types of pruritus (ie, aquagenic, cholestatic, uremic, atopic dermatitis related).3 A case report of LDN successfully treating a patient with psoriasis also has been published.6 We often use LDN at the University of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin) to treat patients with psoriasis. Ekelem et al3 also discussed patients with skin conditions that either had no response or worsened with naltrexone treatment, including various types of pruritus (ie, uremic, mycosis fungoides related, other causes of pruritus). Importantly, in the majority of cases without an improved response, the dose used was 50 mg/d.3 Higher doses of naltrexone are not known to have anti-inflammatory effects.

Low-dose naltrexone can be considered as a treatment option in patients with contraindications to other systemic anti-inflammatory treatments; for example, patients with a history of malignancy may prefer to avoid treatment with biologic agents. Low-dose naltrexone also can be considered as a treatment option in patients who are uncomfortable with the side-effect profiles of other systemic anti-inflammatory treatments, such as the risk for leukemias and lymphomas associated with biologic agents, the risk for liver toxicity with methotrexate, or the risk for hyperlipidemia with acitretin.

How to Monitor

The following monitoring information is adapted from the practice of Apple Bodemer, MD, a board-certified dermatologist at the University of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin) who also is fellowship trained in integrative medicine.

There is a paucity of published data about LDN dosing for inflammatory skin diseases. However, prescribers should be aware that LDN can alter thyroid hormone levels, especially in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. If a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level within reference range has not been noted in the last year, consider screening with a TSH test and also assessing for a personal or family history of thyroid disease. If the TSH level is within reference range, there generally is no need to monitor while treating with LDN. Consider checking TSH levels every 4 months in patients with thyroid disease while they are on LDN therapy and be sure to educate them about symptoms of hyperthyroidism.

Side Effects

Low-dose naltrexone has a minimal side-effect profile with self-limited side effects that often resolve within approximately 1 week. One of the most commonly reported side effects is sleep disturbance with vivid dreams, which has been reported in 37% of participants.1 If your patients experience this side effect, you can reassure them that it improves with time. You also can switch to morning dosing to try and alleviate sleep disturbances at night. Another possible side effect is gastrointestinal tract upset. Importantly, there is no known abuse potential for LDN.1 To stop LDN, patients should be stable for 6 to 12 months, and there is no need to wean them off it.

Cost and Availability

Because use of LDN in dermatology is considered off label and it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat any medical conditions, it must be prescribed through a compounding pharmacy, usually without insurance coverage. The monthly cost is approximately $30 depending on the pharmacy (unpublished data), which may be cost prohibitive for patients, so it is important to counsel them about price

Final Thoughts

Low-dose naltrexone is an alternative treatment option that can be considered in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. It has a favorable side-effect profile, especially compared to other systemic anti-inflammatory agents; however, additional studies are needed to learn more about its safety and efficacy. If patients ask you about LDN, the information provided here can guide you with how it works and how to prescribe it.

Low-dose naltrexone (LDN) has shown efficacy in off-label treatment of a variety of inflammatory diseases ranging from Crohn disease to multiple sclerosis.1 There are limited data about the use of LDN in dermatology, but reports regarding how it works as an anti-inflammatory agent have been published.1,2

Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist that originally was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat addiction to alcohol, opiates, and heroin.2 The dose of naltrexone to treat addiction ranges from 50 to 100 mg/d, and at these levels the effects of opioids are blocked for 24 hours; however, the dosing for LDN is much lower, ranging from 1.5 to 4.5 mg/d.3 At this low dose, naltrexone partially binds to various opioid receptors, leading to a temporary blockade.4 One of the downstream effects of this opioid receptor blockade is a paradoxical increase in endogenous endorphins.3

In addition to opioid blockage, lower doses of naltrexone have anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting nonopioid receptors. Naltrexone blocks toll-like receptor 4, which is found on keratinocytes and also on macrophages such as microglia.5 These macrophages also contain inflammatory compounds such as tumor necrosis factor α and IL-6. Low-dose naltrexone can suppress levels of these inflammatory markers. It is important to note that these anti-inflammatory effects have not been observed at the standard higher doses of naltrexone.1

When to Use

Low-dose naltrexone is a treatment option for inflammatory dermatologic conditions. A recent review of the literature outlined the use of LDN in a variety of inflammatory skin conditions. Improvement was noted in patients with Hailey-Hailey disease, lichen planopilaris, and various types of pruritus (ie, aquagenic, cholestatic, uremic, atopic dermatitis related).3 A case report of LDN successfully treating a patient with psoriasis also has been published.6 We often use LDN at the University of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin) to treat patients with psoriasis. Ekelem et al3 also discussed patients with skin conditions that either had no response or worsened with naltrexone treatment, including various types of pruritus (ie, uremic, mycosis fungoides related, other causes of pruritus). Importantly, in the majority of cases without an improved response, the dose used was 50 mg/d.3 Higher doses of naltrexone are not known to have anti-inflammatory effects.

Low-dose naltrexone can be considered as a treatment option in patients with contraindications to other systemic anti-inflammatory treatments; for example, patients with a history of malignancy may prefer to avoid treatment with biologic agents. Low-dose naltrexone also can be considered as a treatment option in patients who are uncomfortable with the side-effect profiles of other systemic anti-inflammatory treatments, such as the risk for leukemias and lymphomas associated with biologic agents, the risk for liver toxicity with methotrexate, or the risk for hyperlipidemia with acitretin.

How to Monitor

The following monitoring information is adapted from the practice of Apple Bodemer, MD, a board-certified dermatologist at the University of Wisconsin (Madison, Wisconsin) who also is fellowship trained in integrative medicine.

There is a paucity of published data about LDN dosing for inflammatory skin diseases. However, prescribers should be aware that LDN can alter thyroid hormone levels, especially in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. If a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level within reference range has not been noted in the last year, consider screening with a TSH test and also assessing for a personal or family history of thyroid disease. If the TSH level is within reference range, there generally is no need to monitor while treating with LDN. Consider checking TSH levels every 4 months in patients with thyroid disease while they are on LDN therapy and be sure to educate them about symptoms of hyperthyroidism.

Side Effects

Low-dose naltrexone has a minimal side-effect profile with self-limited side effects that often resolve within approximately 1 week. One of the most commonly reported side effects is sleep disturbance with vivid dreams, which has been reported in 37% of participants.1 If your patients experience this side effect, you can reassure them that it improves with time. You also can switch to morning dosing to try and alleviate sleep disturbances at night. Another possible side effect is gastrointestinal tract upset. Importantly, there is no known abuse potential for LDN.1 To stop LDN, patients should be stable for 6 to 12 months, and there is no need to wean them off it.

Cost and Availability

Because use of LDN in dermatology is considered off label and it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat any medical conditions, it must be prescribed through a compounding pharmacy, usually without insurance coverage. The monthly cost is approximately $30 depending on the pharmacy (unpublished data), which may be cost prohibitive for patients, so it is important to counsel them about price

Final Thoughts

Low-dose naltrexone is an alternative treatment option that can be considered in patients with inflammatory skin diseases. It has a favorable side-effect profile, especially compared to other systemic anti-inflammatory agents; however, additional studies are needed to learn more about its safety and efficacy. If patients ask you about LDN, the information provided here can guide you with how it works and how to prescribe it.

- Younger J, Parkitny L, McLain D. The use of low-dose naltrexone (LDN) as a novel anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:451-459.

- Brown N, Panksepp J. Low-dose naltrexone for disease prevention and quality of life. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:333-337.

- Ekelem C, Juhasz M, Khera P, et al. Utility of naltrexone treatment for chronic inflammatory dermatologic conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:229-236.

- Bihari B. Efficacy of low dose naltrexone as an immune stabilizing agent for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care. 1995;9:3.

- Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions [published online December 21, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1746-1752.

- Bridgman AC, Kirchhof MG. Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris using low-dose naltrexone. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:827-829.

- Younger J, Parkitny L, McLain D. The use of low-dose naltrexone (LDN) as a novel anti-inflammatory treatment for chronic pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;33:451-459.

- Brown N, Panksepp J. Low-dose naltrexone for disease prevention and quality of life. Med Hypotheses. 2009;72:333-337.

- Ekelem C, Juhasz M, Khera P, et al. Utility of naltrexone treatment for chronic inflammatory dermatologic conditions: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:229-236.

- Bihari B. Efficacy of low dose naltrexone as an immune stabilizing agent for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care. 1995;9:3.

- Lee B, Elston DM. The uses of naltrexone in dermatologic conditions [published online December 21, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1746-1752.

- Bridgman AC, Kirchhof MG. Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris using low-dose naltrexone. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:827-829.

Resident Pearl

- Low-dose naltrexone is an alternative antiinflammatory treatment to consider in patients with inflammatory skin diseases, with a minimal side-effect profile.

A Comparison of Knowledge Acquisition and Perceived Efficacy of a Traditional vs Flipped Classroom–Based Dermatology Residency Curriculum

The ideal method of resident education is a subject of great interest within the medical community, and many dermatology residency programs utilize a traditional classroom model for didactic training consisting of required textbook reading completed at home and classroom lectures that often include presentations featuring text, dermatology images, and questions throughout the lecture. A second teaching model is known as the flipped, or inverted, classroom. This model moves the didactic material that typically is covered in the classroom into the realm of home study or homework and focuses on application and clarification of the new material in the classroom. 1 There is an emphasis on completing and understanding course material prior to the classroom session. Students are expected to be prepared for the lesson, and the classroom session can include question review and deeper exploration of the topic with a focus on subject mastery. 2

In recent years, the flipped classroom model has been used in elementary education, due in part to the influence of teachers Bergmann and Sams,3 as described in their book Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. More recently, Prober and Khan4 argued for its use in medical education, and this model has been utilized in medical school curricula to teach specialty subjects, including medical dermatology.5

Given the increasing popularity and use of the flipped classroom, the primary objective of this study was to determine if a difference in knowledge acquisition and resident perception exists between the traditional and flipped classrooms. If differences do exist, the secondary aim was to quantify them. We hypothesized that the flipped classroom actively engages residents and would improve both knowledge acquisition and resident sentiment toward the residency program curriculum compared to the traditional model.

Methods

The Duke Health (Durham, North Carolina) institutional review board granted approval for this study. All of the dermatology residents from Duke University Medical Center for the 2014-2015 academic year participated in this study. Twelve individual lectures chosen by the dermatology residency program director were included: 6 traditional lectures and 6 flipped lectures. The lectures were paired for similar content.

Survey Administration

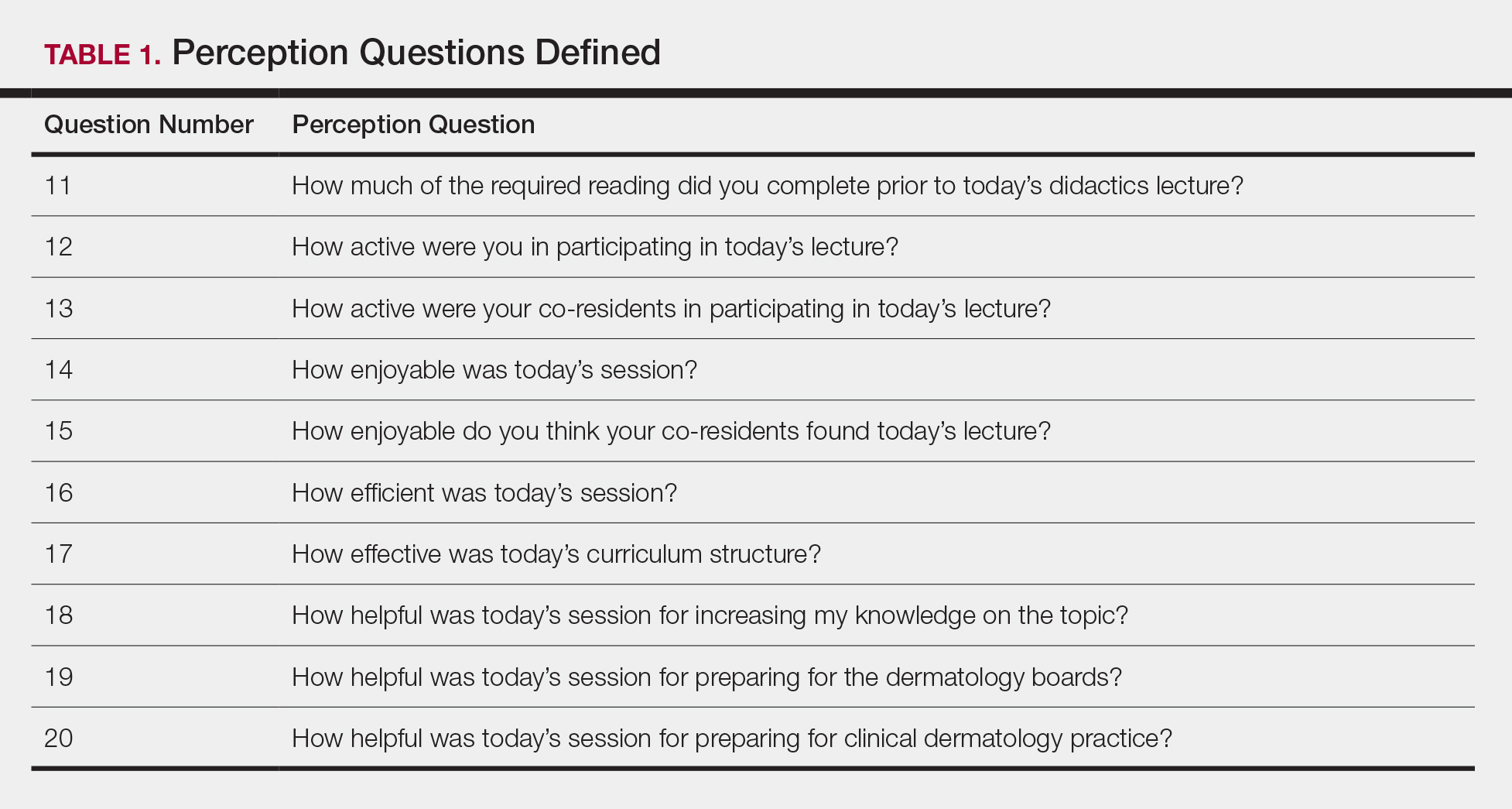

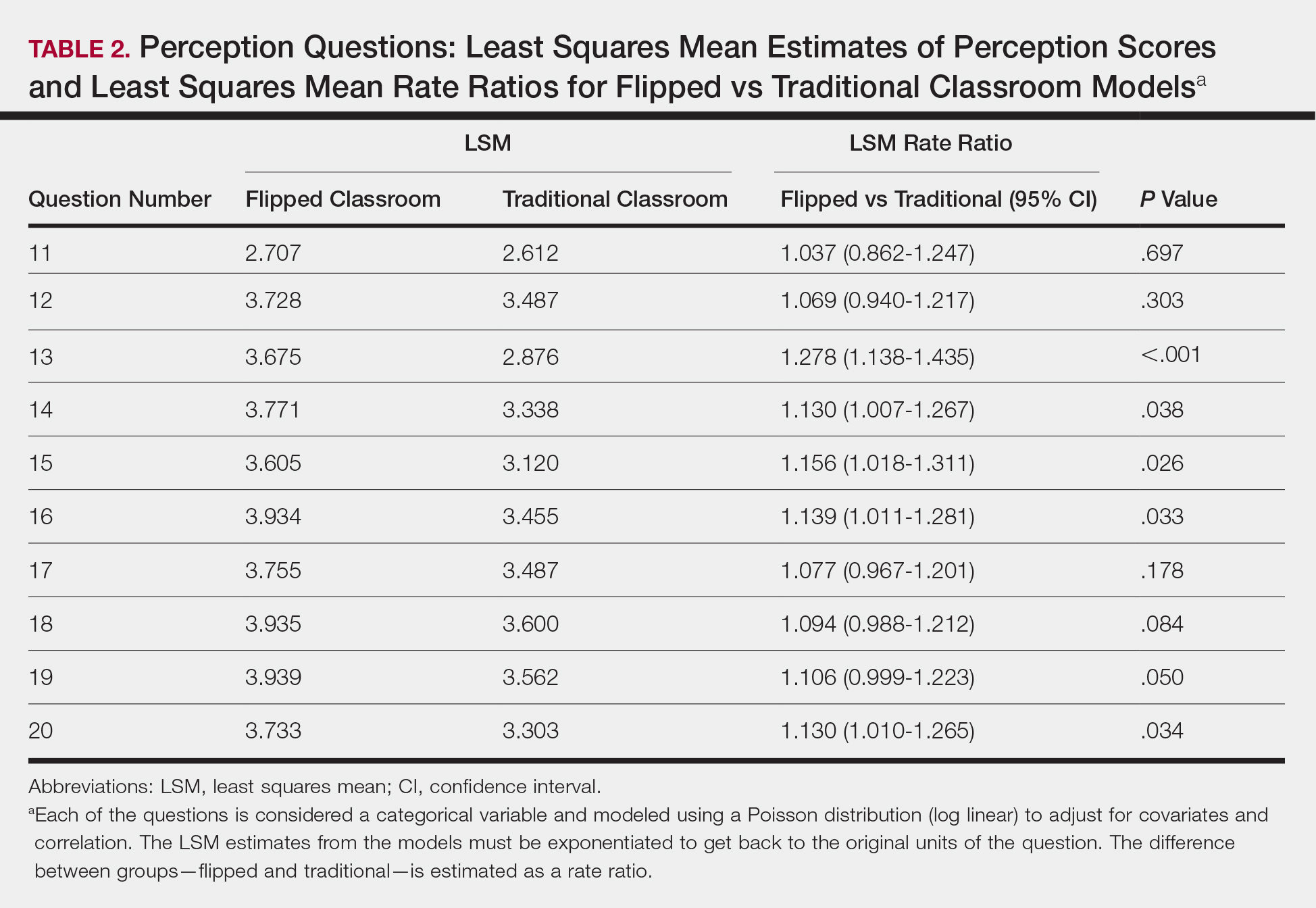

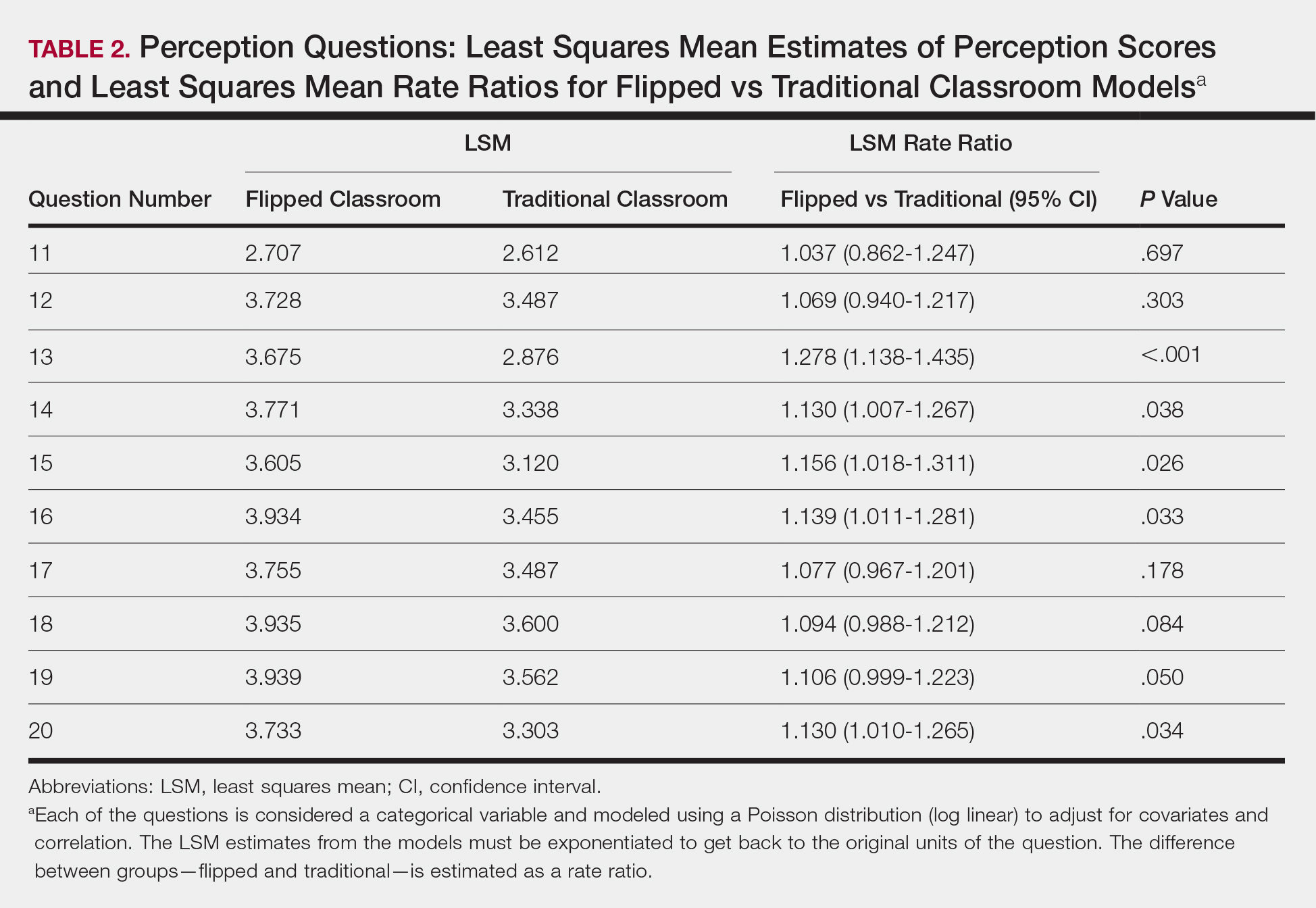

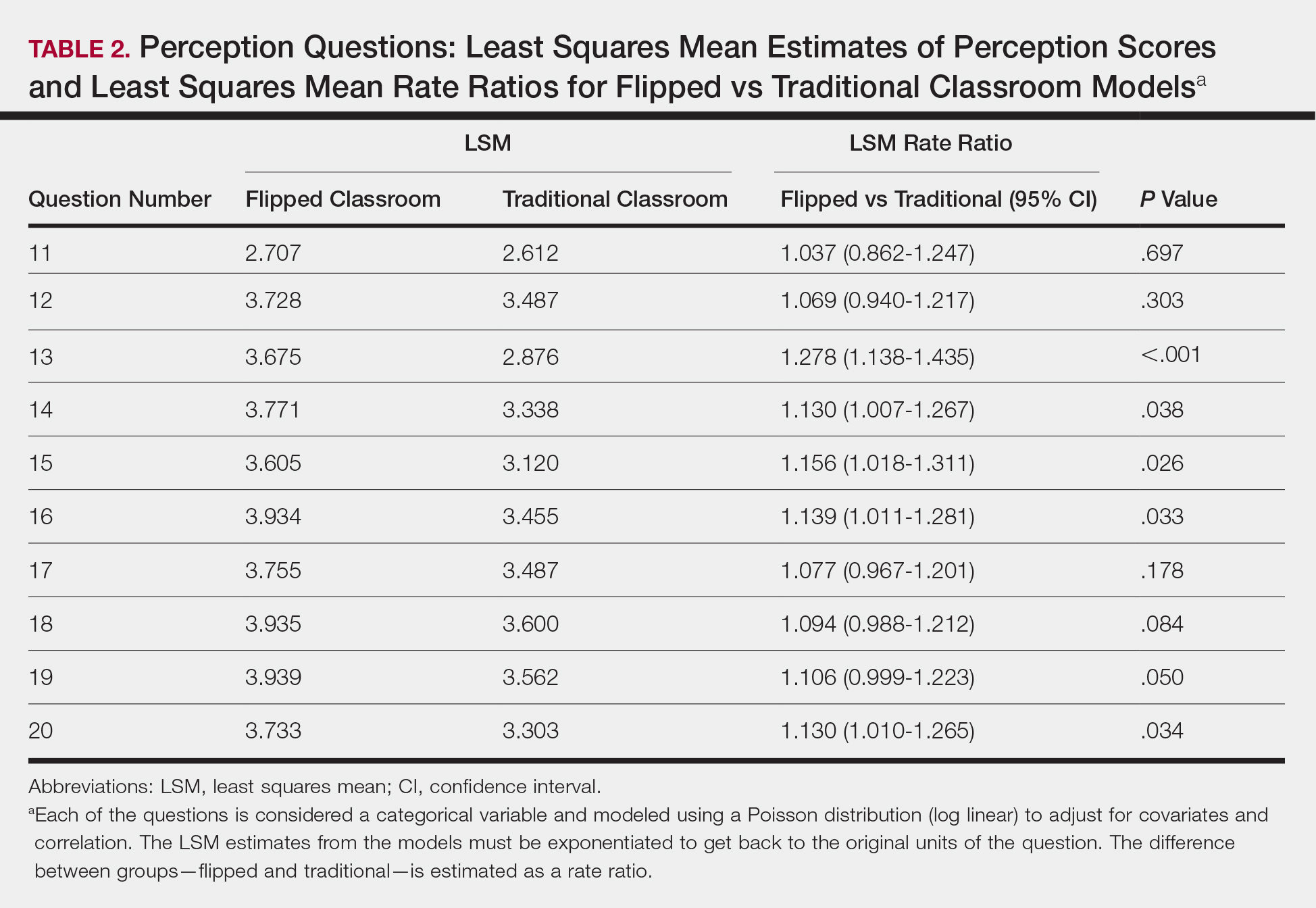

Each resident was assigned a unique 4-digit numeric code that was unknown to the investigators and recorded at the beginning of each survey. The residents expected flipped lectures for each session and were blinded as to when a traditional lecture and quiz would occur, with the exception of the resident providing the lecture. Classroom presentations were immediately followed by a voluntary survey administered through Qualtrics.6 Consent was given at the beginning of each survey, followed by 10 factual questions and 10 perception questions. The factual questions varied based on the lecture topic and were multiple-choice questions written by the program director, associate program director, and faculty. Each factual question was worth 10 points, and the scaled score for each quiz had a maximum value of 100. The perception questions were developed by the authors (J.H. and A.R.A.) in consultation with a survey methodology expert at the Duke Social Science Research Institute. These questions remained constant across each survey and were descriptive based on standard response scales. The data were extracted from Qualtrics for statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

The mean score with the standard deviation for each factual question quiz was calculated and plotted. A generalized linear mixed model was created to study the difference in quiz scores between the 2 classroom models after adjusting for other covariates, including resident, the interaction between resident and class type, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was specified as a random variable, and a variance components covariance structure was used. For the perception questions, the frequency and percentage of each answer for a question was counted. Generalized linear mixed models with a Poisson distribution were created to study the difference in answers for each survey question between the 2 curriculum types after adjusting for other covariates, including scores for factual questions, quiz time, and the interaction between class type and quiz time. The variable resident was again specified as a random variable, and a diagonal covariance structure was used. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software package version 9.4 (SAS Institute) by the Duke University Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All 9 of the department’s residents were included and participated in this study. Mean score with standard deviation for each factual quiz is plotted in the Figure. Across all residents, the mean factual quiz score was slightly higher but not statistically significant in the flipped vs traditional classrooms (67.5% vs 65.4%; P=.448)(data not shown). When comparing traditional and flipped factual quiz scores by individual resident, there was not a significant difference in quiz performance (P=.166)(data not shown). However, there was a significant difference in the factual quiz scores among residents for all quizzes (P=.005) as well as a significant difference in performance between each individual quiz over time (P<.001)(data not shown). In the traditional classroom, residents demonstrated a trend in variable performance with each factual quiz. In the flipped classroom, residents also had variable performance, with wide-ranging scores (P=.008)(data not shown).

Each resident also answered 10 perception questions (Table 1). When comparing the responses by quiz type (Table 2), there was a significant difference for several questions in favor of the flipped classroom: how actively residents thought their co-residents participated in the lecture (P<.001), how much each resident enjoyed the session (P=.038), and how much each resident believed their co-residents enjoyed the session (P=.026). Additionally, residents thought that the flipped classroom sessions were more efficient (P=.033), better prepared them for boards (P=.050), and better prepared them for clinical practice (P=.034). There was not a significant difference in the amount of reading and preparation residents did for class (P=.697), how actively the residents thought they participated in the lecture (P=.303), the effectiveness of the day’s curriculum structure (P=.178), or whether residents thought the lesson increased their knowledge on the topic (P=.084).

Comment

The traditional model in medical education has undergone changes in recent years, and researchers have been looking for new ways to convey more information in shorter periods of time, especially as the field of medicine continues to expand. Despite the growing popularity and adoption of the flipped classroom, studies in dermatology have been limited. In this study, we compared a traditional classroom model with the flipped model, assessing both knowledge acquisition and resident perception of the experience.

There was not a significant difference in mean objective quiz scores when comparing the 2 curricula. The flipped model was not better or worse than the traditional teaching model at relaying information and promoting learning. Rather, there was a significant difference in quiz scores based on the individual resident and on the individual quiz. Individual performance was not affected by the teaching model but rather by the individual resident and lecture topic.

These findings differ from a study of internal medicine residents, which revealed that trainees in a quality-improvement flipped classroom had greater increases in knowledge than a traditional cohort.7 It is difficult to make direct comparisons to this group, given the difference in specialty and subject content. In comparison, an emergency medicine program completed a cross-sectional cohort study of in-service examination scores in the setting of a traditional curriculum (2011-2012) vs a flipped curriculum (2015-2016) and found that there was no statistical difference in average in-service examination scores.8 The type of examination content in this study may be more similar to the quizzes that our residents experienced (ie, fact-based material based on traditional medical knowledge).

The dermatology residents favored the flipped curriculum for 6 of 10 perception questions, which included areas of co-resident participation, personal and co-resident enjoyment, efficiency, boards preparation, and preparation for clinical practice. They did not favor the flipped classroom for prelecture preparation, personal participation, lecture effectiveness, or knowledge acquisition. They perceived their peers as being more engaged and found the flipped classroom to be a more positive experience. The residents thought that the flipped lectures were more time efficient, which could have contributed to overall learner satisfaction. Additionally, they thought that the flipped model better prepared them for both the boards and clinical practice, which are markers of future performance.

These findings are consistent with other studies that revealed improved postcourse perception scores for a quality improvement emergency medicine–flipped classroom. Most of this group preferred the flipped classroom over the traditional after completion of the flipped curriculum.9 A neurosurgery residency program also reported increased resident engagement and resident preference for a newly designed flipped curriculum.10

Overall, our data indicate that there was no objective change in knowledge acquisition at the time of the quiz, but learner satisfaction was significantly greater in the flipped classroom model.

Limitations

This study was comprised of a small number of residents from a single institution and was based on a limited number of lectures given throughout the year. All lectures during the study year were flipped with the exception of the 6 traditional study lectures. Therefore, each resident who presented a traditional lecture was not blinded for her individual assigned lecture. In addition, because traditional lectures only occurred on study days, once the lectures started, all trainees could predict that a content quiz would occur at the end of the session, which could potentially introduce bias toward better quiz performance for the traditional lectures.

Conclusion

When comparing traditional and flipped classroom models, we found no difference in knowledge acquisition. Rather, the difference in quiz scores was among individual residents. There was a significant positive difference in how residents perceived these teaching models, including enjoyment and feeling prepared for the boards. The flipped classroom model provides another opportunity to better engage residents during teaching and should be considered as part of dermatology residency education.

Acknowledgments

Duke Social Sciences Institute postdoctoral fellow Scott Clifford, PhD, and Duke Dermatology residents Daniel Chang, MD; Sinae Kane, MD; Rebecca Bialas, MD; Jolene Jewell, MD; Elizabeth Ju, MD; Michael Raisch, MD; Reed Garza, MD; Joanna Hooten, MD; and E. Schell Bressler, MD (all Durham, North Carolina)

- Lage MJ, Platt GJ, Treglia M. Inverting the classroom: a gateway to creating an inclusive learning environment. J Economic Educ. 2000;31:30-43.

- Gillispie V. Using the flipped classroom to bridge the gap to generation Y. Ochsner J. 2016;16:32-36.

- Bergmann J, Sams A. Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. Alexandria, VA: International Society for Technology in Education; 2012.

- Prober CG, Khan S. Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013;88:1407-1410.

- Aughenbaugh WD. Dermatology flipped, blended and shaken: a comparison of the effect of an active learning modality on student learning, satisfaction, and teaching. Paper presented at: Dermatology Teachers Exchange Group 2013; September 27, 2013; Chicago, IL.

- Oppenheimer AJ, Pannucci CJ, Kasten SJ, et al. Survey says? A primer on web-based survey design and distribution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:299-304.

- Bonnes SL, Ratelle JT, Halvorsen AJ, et al. Flipping the quality improvement classroom in residency education. Acad Med. 2017;92:101-107.

- King AM, Mayer C, Barrie M, et al. Replacing lectures with small groups: the impact of flipping the residency conference day. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:11-17.

- Young TP, Bailey CJ, Guptill M, et al. The flipped classroom: a modality for mixed asynchronous and synchronous learning in a residency program. Western J Emerg Med. 2014;15:938-944.

- Girgis F, Miller JP. Implementation of a “flipped classroom” for neurosurgery resident education. Can J Neurol Sci. 2018;45:76-82.

The ideal method of resident education is a subject of great interest within the medical community, and many dermatology residency programs utilize a traditional classroom model for didactic training consisting of required textbook reading completed at home and classroom lectures that often include presentations featuring text, dermatology images, and questions throughout the lecture. A second teaching model is known as the flipped, or inverted, classroom. This model moves the didactic material that typically is covered in the classroom into the realm of home study or homework and focuses on application and clarification of the new material in the classroom. 1 There is an emphasis on completing and understanding course material prior to the classroom session. Students are expected to be prepared for the lesson, and the classroom session can include question review and deeper exploration of the topic with a focus on subject mastery. 2

In recent years, the flipped classroom model has been used in elementary education, due in part to the influence of teachers Bergmann and Sams,3 as described in their book Flip Your Classroom: Reach Every Student in Every Class Every Day. More recently, Prober and Khan4 argued for its use in medical education, and this model has been utilized in medical school curricula to teach specialty subjects, including medical dermatology.5

Given the increasing popularity and use of the flipped classroom, the primary objective of this study was to determine if a difference in knowledge acquisition and resident perception exists between the traditional and flipped classrooms. If differences do exist, the secondary aim was to quantify them. We hypothesized that the flipped classroom actively engages residents and would improve both knowledge acquisition and resident sentiment toward the residency program curriculum compared to the traditional model.

Methods

The Duke Health (Durham, North Carolina) institutional review board granted approval for this study. All of the dermatology residents from Duke University Medical Center for the 2014-2015 academic year participated in this study. Twelve individual lectures chosen by the dermatology residency program director were included: 6 traditional lectures and 6 flipped lectures. The lectures were paired for similar content.

Survey Administration