User login

Utilization, Cost, and Prescription Trends of Antipsychotics Prescribed by Dermatologists for Medicare Patients

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

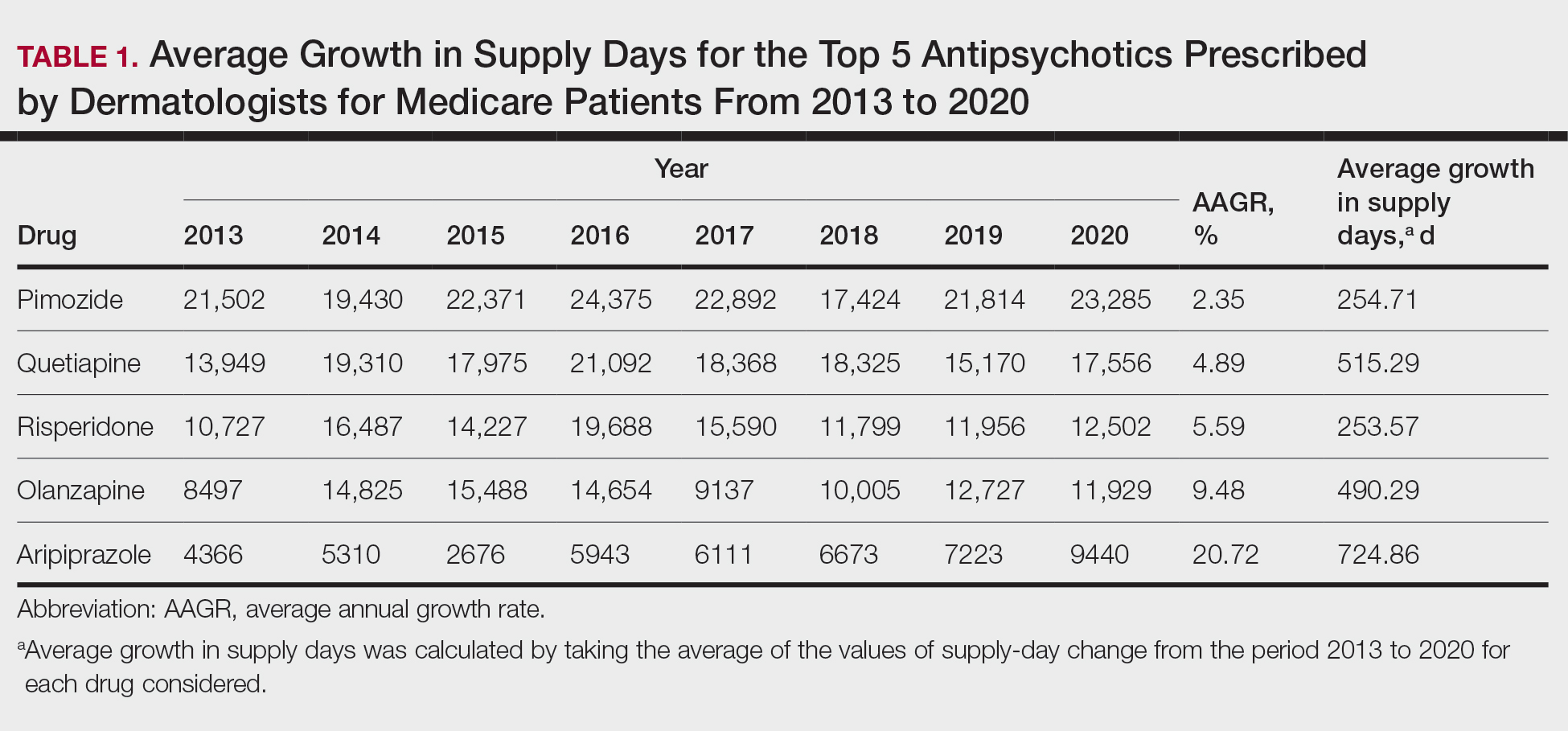

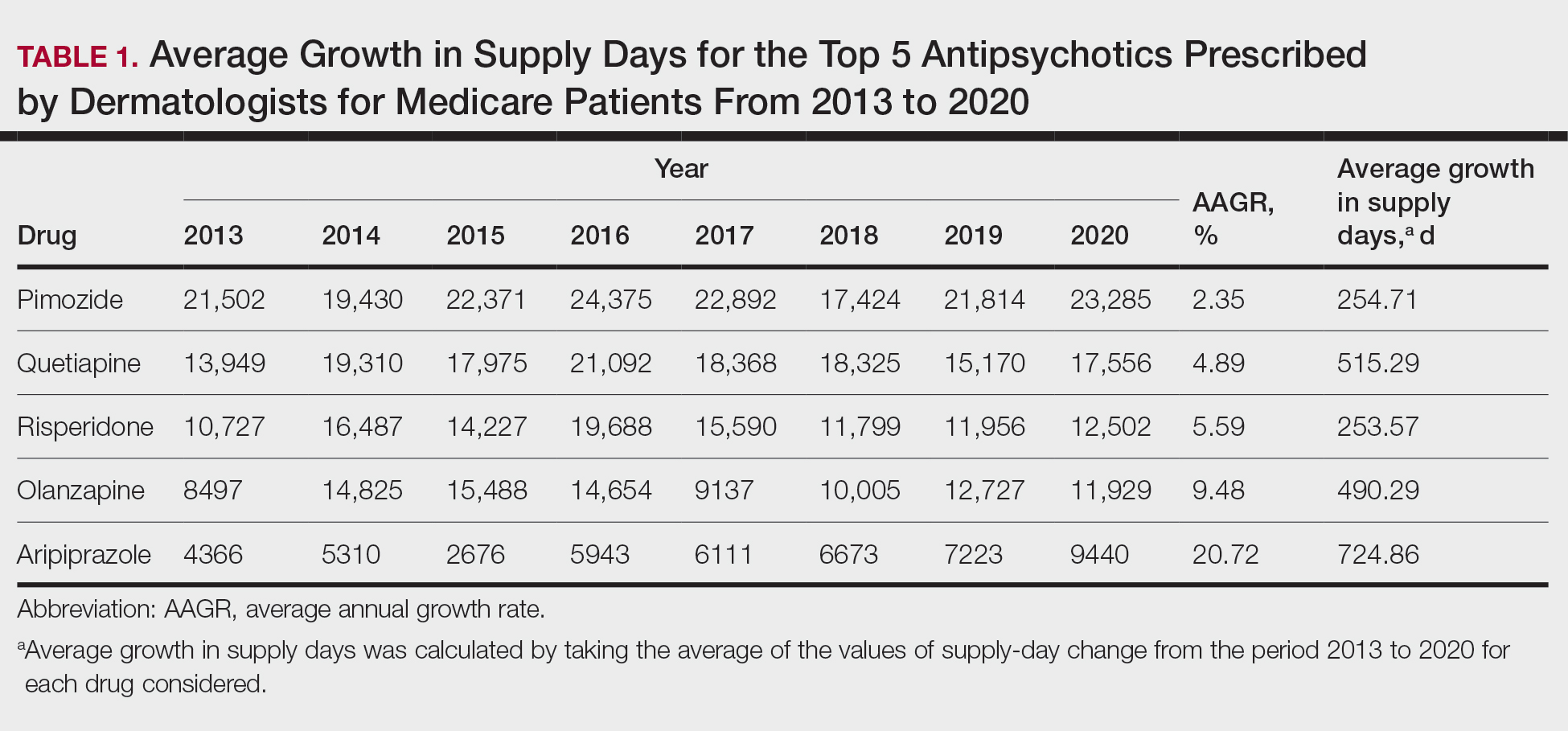

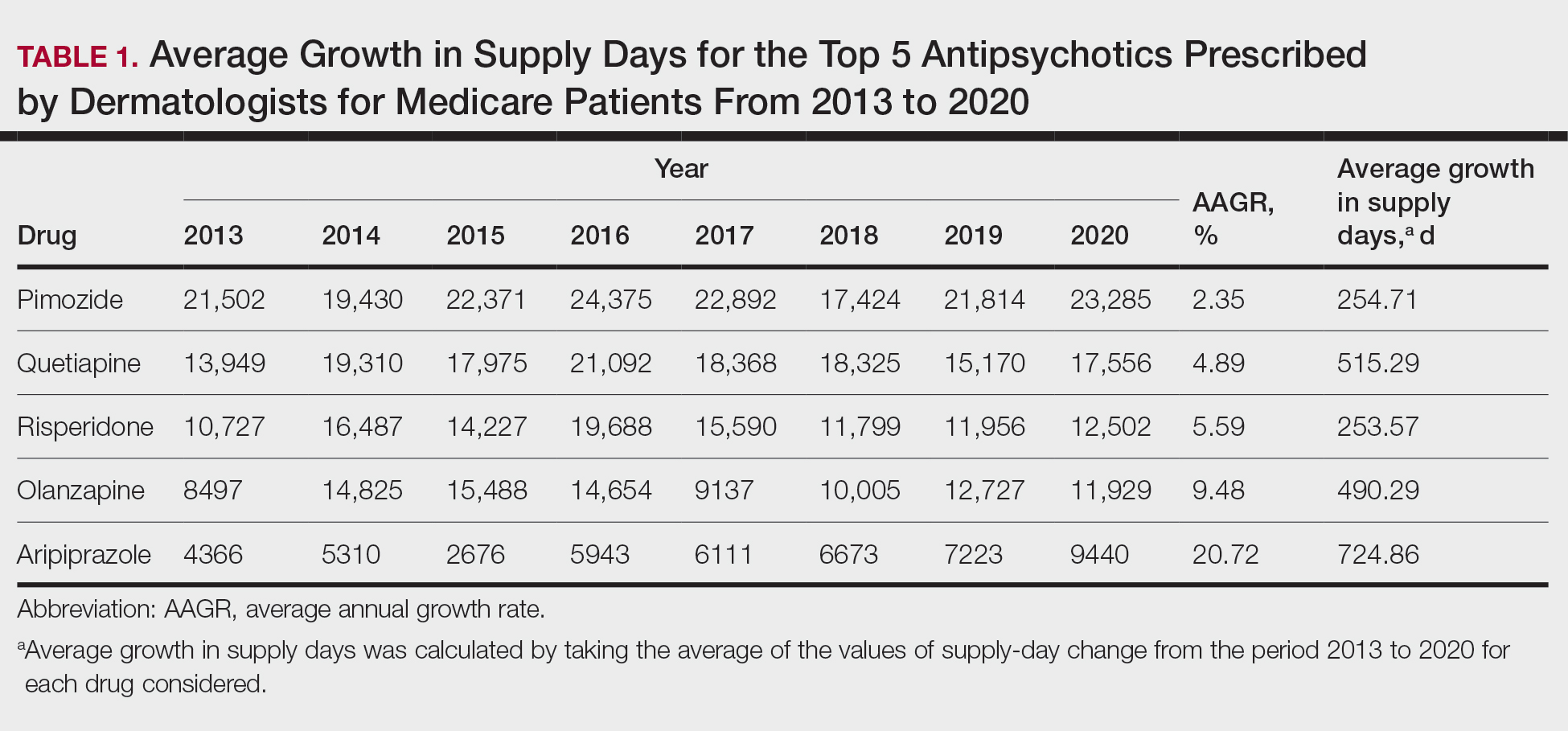

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

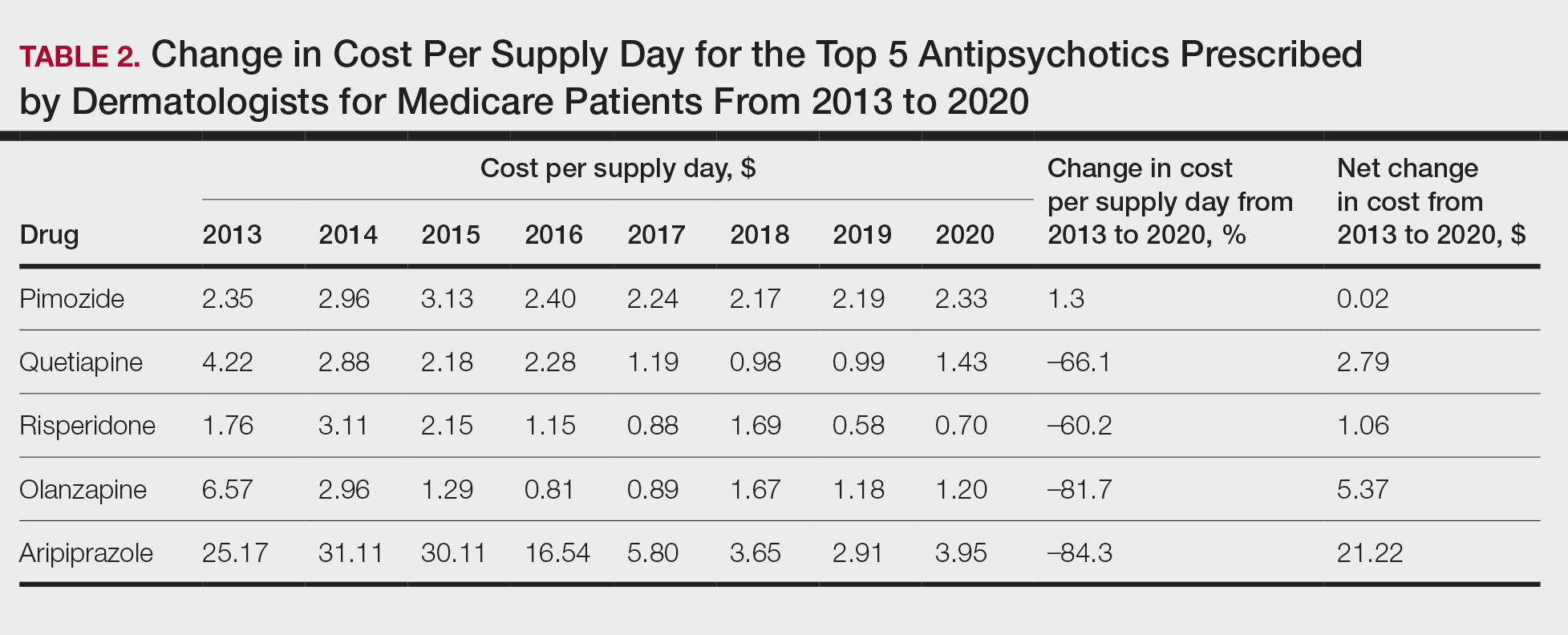

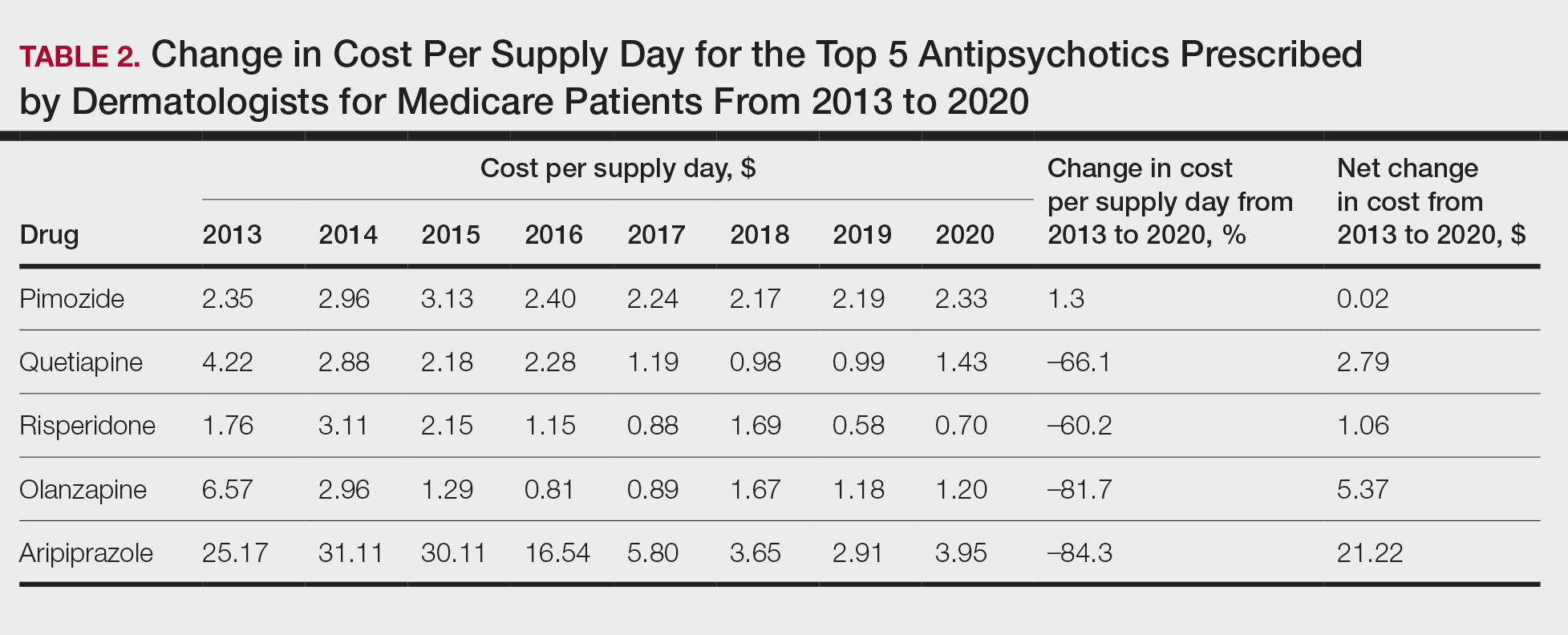

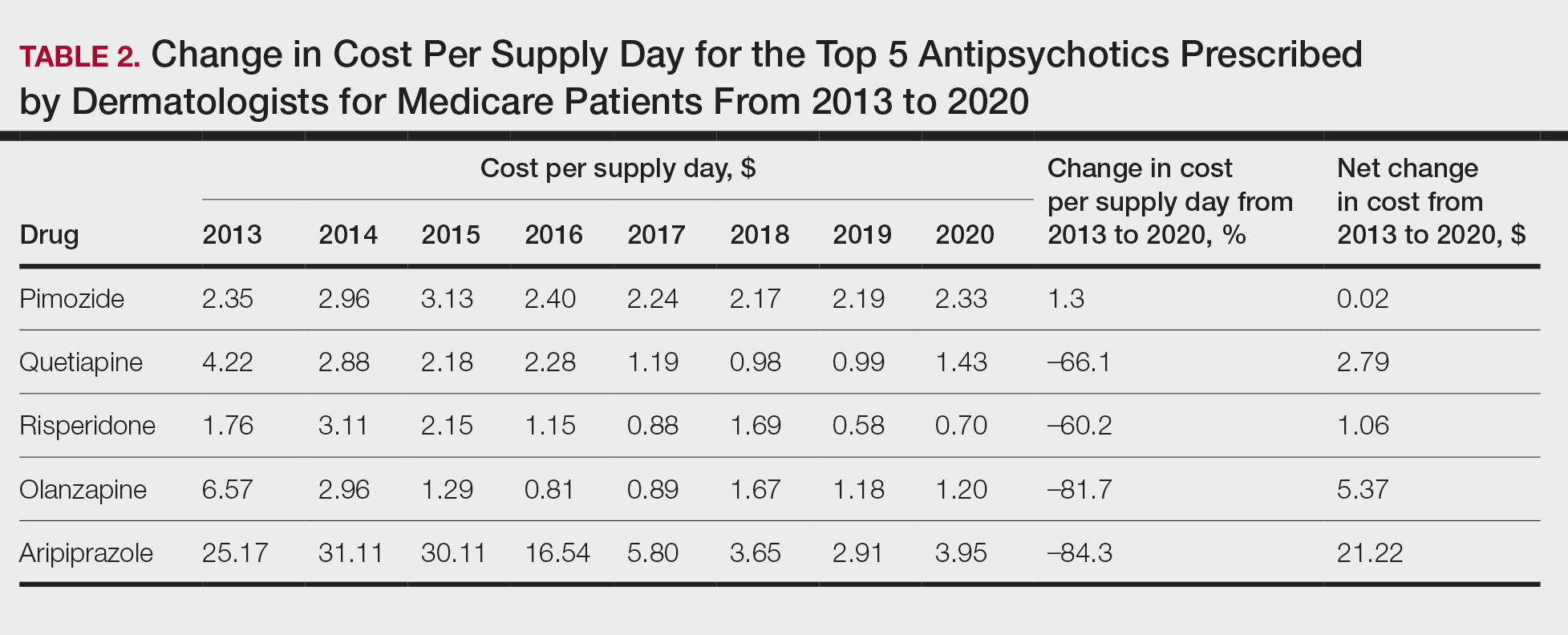

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

Practice Points

- Dermatologists are frontline medical providers who can be useful in screening for primary psychiatric disorders in patients with dermatologic manifestations.

- Second-generation antipsychotics are effective for treating many psychiatric disorders.

Commentary: Topical Treatments for AD and Possible Lifestyle Adjustments, July 2024

In this real-life study, Patruno and colleagues found that dupilumab worked well but more slowly in patients with a higher body mass index (BMI). On the basis of these findings, if patients are not in a hurry, the standard dose of dupilumab should eventually work, regardless of BMI. If patients are in a hurry to see improvement, perhaps dose escalation could be considered for patients with a high BMI, or perhaps topical triamcinolone could be used to speed time-to–initial resolution in the high-BMI population.

In the very well-done study by Silverberg and colleagues, tapinarof was effective, well tolerated, and generally safe for atopic dermatitis in adults and children. Great! Topical tapinarof should soon be another good option for our patients with atopic dermatitis. How valuable will it be? We already have topical corticosteroids that are very effective for atopic dermatitis, and we have multiple other nonsteroidal topical agents, including topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical ruxolitinib.

Perhaps the biggest limitation of all these treatments is poor adherence to topical treatment. I'm not sure how effective even highly effective nonsteroidal topicals will be for patients who did not respond to topical steroids when the primary reason for topical steroid failure is poor treatment adherence. I'd love to see the development of a once-a-week or once-a-month topical therapy that would address the poor-adherence hurdle.

Abrocitinib is an effective treatment for improving atopic dermatitis. Although atopic dermatitis is a chronic condition requiring long-term management, we'd like to minimize exposure to the drug to avoid side effects. Thyssen and colleagues described the effectiveness of two maintenance treatment regimens: continuing 200 mg/d or reducing the dose to 100 mg/d. Both regimens prevented flares more than did placebo. This study also provided information on safety of the maintenance regimens. Rates of herpetic infections were low across all the groups, but unlike the two treatment groups, there were no cases of herpes simplex infection in the patients in the placebo arm.

In this real-life study, Patruno and colleagues found that dupilumab worked well but more slowly in patients with a higher body mass index (BMI). On the basis of these findings, if patients are not in a hurry, the standard dose of dupilumab should eventually work, regardless of BMI. If patients are in a hurry to see improvement, perhaps dose escalation could be considered for patients with a high BMI, or perhaps topical triamcinolone could be used to speed time-to–initial resolution in the high-BMI population.

In the very well-done study by Silverberg and colleagues, tapinarof was effective, well tolerated, and generally safe for atopic dermatitis in adults and children. Great! Topical tapinarof should soon be another good option for our patients with atopic dermatitis. How valuable will it be? We already have topical corticosteroids that are very effective for atopic dermatitis, and we have multiple other nonsteroidal topical agents, including topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical ruxolitinib.

Perhaps the biggest limitation of all these treatments is poor adherence to topical treatment. I'm not sure how effective even highly effective nonsteroidal topicals will be for patients who did not respond to topical steroids when the primary reason for topical steroid failure is poor treatment adherence. I'd love to see the development of a once-a-week or once-a-month topical therapy that would address the poor-adherence hurdle.

Abrocitinib is an effective treatment for improving atopic dermatitis. Although atopic dermatitis is a chronic condition requiring long-term management, we'd like to minimize exposure to the drug to avoid side effects. Thyssen and colleagues described the effectiveness of two maintenance treatment regimens: continuing 200 mg/d or reducing the dose to 100 mg/d. Both regimens prevented flares more than did placebo. This study also provided information on safety of the maintenance regimens. Rates of herpetic infections were low across all the groups, but unlike the two treatment groups, there were no cases of herpes simplex infection in the patients in the placebo arm.

In this real-life study, Patruno and colleagues found that dupilumab worked well but more slowly in patients with a higher body mass index (BMI). On the basis of these findings, if patients are not in a hurry, the standard dose of dupilumab should eventually work, regardless of BMI. If patients are in a hurry to see improvement, perhaps dose escalation could be considered for patients with a high BMI, or perhaps topical triamcinolone could be used to speed time-to–initial resolution in the high-BMI population.

In the very well-done study by Silverberg and colleagues, tapinarof was effective, well tolerated, and generally safe for atopic dermatitis in adults and children. Great! Topical tapinarof should soon be another good option for our patients with atopic dermatitis. How valuable will it be? We already have topical corticosteroids that are very effective for atopic dermatitis, and we have multiple other nonsteroidal topical agents, including topical calcineurin inhibitors and topical ruxolitinib.

Perhaps the biggest limitation of all these treatments is poor adherence to topical treatment. I'm not sure how effective even highly effective nonsteroidal topicals will be for patients who did not respond to topical steroids when the primary reason for topical steroid failure is poor treatment adherence. I'd love to see the development of a once-a-week or once-a-month topical therapy that would address the poor-adherence hurdle.

Abrocitinib is an effective treatment for improving atopic dermatitis. Although atopic dermatitis is a chronic condition requiring long-term management, we'd like to minimize exposure to the drug to avoid side effects. Thyssen and colleagues described the effectiveness of two maintenance treatment regimens: continuing 200 mg/d or reducing the dose to 100 mg/d. Both regimens prevented flares more than did placebo. This study also provided information on safety of the maintenance regimens. Rates of herpetic infections were low across all the groups, but unlike the two treatment groups, there were no cases of herpes simplex infection in the patients in the placebo arm.

Commentary: Interrelationships Between AD and Other Conditions, June 2024

Traidl and colleagues report that obesity was linked to worse AD in German patients. The authors hit the nail on the head with their conclusions: "In this large and well-characterized AD patient cohort, obesity is significantly associated with physician- and patient-assessed measures of AD disease severity. However, the corresponding effect sizes were low and of questionable clinical relevance." What might account for the small difference in disease severity? Adherence to treatment is highly variable among patients with AD. A small tendency toward worse adherence in patients with obesity could easily explain the small differences seen in disease severity.

Eichenfeld and colleagues report that topical ruxolitinib maintained good efficacy over a year in open-label use. Topical ruxolitinib is a very effective treatment for AD. If real-life AD patients on topical ruxolitinib were to lose efficacy over time, I'd consider the possibility that they've developed mutant Janus kinase (JAK) enzymes that are no longer responsive to the drug. Just kidding. I doubt that such mutations ever occur. If topical ruxolitinib in AD patients were to lose efficacy over time, I'd strongly consider the possibility that patients' adherence to the treatment is no longer as good as it was before. Long-term adherence to topical treatment can be abysmal. Adherence in clinical trials is probably a lot better than in clinical practice. When we see topical treatments that are effective in clinical trials failing in real-life patients with AD, it may be prudent to address the possibility of poor adherence.

I'd love to see a head-to-head trial of tralokinumab vs dupilumab in the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Lacking that, Torres and colleagues report an indirect comparison of the two drugs in patients also treated with topical steroids. This study, funded by the manufacturer of tralokinumab, reported that the two drugs have similar efficacy. How much of the efficacy was due to the topical steroid use is not clear to me. I'd still love to see a head-to-head trial of tralokinumab vs dupilumab to have a better, more confident sense of their relative efficacy.

Is AD associated with brain cancer, as reported by Xin and colleagues? I'm not an expert in their methodology, but they did find a statistically significant increased risk, with an odds ratio of 1.0005. I understand the odds ratio for smoking and lung cancer to be about 80. Even if the increased odds of 1.005 — no, wait, that's 1.0005 — is truly due to AD, this tiny difference doesn't seem meaningful in any way.

Traidl and colleagues report that obesity was linked to worse AD in German patients. The authors hit the nail on the head with their conclusions: "In this large and well-characterized AD patient cohort, obesity is significantly associated with physician- and patient-assessed measures of AD disease severity. However, the corresponding effect sizes were low and of questionable clinical relevance." What might account for the small difference in disease severity? Adherence to treatment is highly variable among patients with AD. A small tendency toward worse adherence in patients with obesity could easily explain the small differences seen in disease severity.

Eichenfeld and colleagues report that topical ruxolitinib maintained good efficacy over a year in open-label use. Topical ruxolitinib is a very effective treatment for AD. If real-life AD patients on topical ruxolitinib were to lose efficacy over time, I'd consider the possibility that they've developed mutant Janus kinase (JAK) enzymes that are no longer responsive to the drug. Just kidding. I doubt that such mutations ever occur. If topical ruxolitinib in AD patients were to lose efficacy over time, I'd strongly consider the possibility that patients' adherence to the treatment is no longer as good as it was before. Long-term adherence to topical treatment can be abysmal. Adherence in clinical trials is probably a lot better than in clinical practice. When we see topical treatments that are effective in clinical trials failing in real-life patients with AD, it may be prudent to address the possibility of poor adherence.

I'd love to see a head-to-head trial of tralokinumab vs dupilumab in the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Lacking that, Torres and colleagues report an indirect comparison of the two drugs in patients also treated with topical steroids. This study, funded by the manufacturer of tralokinumab, reported that the two drugs have similar efficacy. How much of the efficacy was due to the topical steroid use is not clear to me. I'd still love to see a head-to-head trial of tralokinumab vs dupilumab to have a better, more confident sense of their relative efficacy.

Is AD associated with brain cancer, as reported by Xin and colleagues? I'm not an expert in their methodology, but they did find a statistically significant increased risk, with an odds ratio of 1.0005. I understand the odds ratio for smoking and lung cancer to be about 80. Even if the increased odds of 1.005 — no, wait, that's 1.0005 — is truly due to AD, this tiny difference doesn't seem meaningful in any way.

Traidl and colleagues report that obesity was linked to worse AD in German patients. The authors hit the nail on the head with their conclusions: "In this large and well-characterized AD patient cohort, obesity is significantly associated with physician- and patient-assessed measures of AD disease severity. However, the corresponding effect sizes were low and of questionable clinical relevance." What might account for the small difference in disease severity? Adherence to treatment is highly variable among patients with AD. A small tendency toward worse adherence in patients with obesity could easily explain the small differences seen in disease severity.

Eichenfeld and colleagues report that topical ruxolitinib maintained good efficacy over a year in open-label use. Topical ruxolitinib is a very effective treatment for AD. If real-life AD patients on topical ruxolitinib were to lose efficacy over time, I'd consider the possibility that they've developed mutant Janus kinase (JAK) enzymes that are no longer responsive to the drug. Just kidding. I doubt that such mutations ever occur. If topical ruxolitinib in AD patients were to lose efficacy over time, I'd strongly consider the possibility that patients' adherence to the treatment is no longer as good as it was before. Long-term adherence to topical treatment can be abysmal. Adherence in clinical trials is probably a lot better than in clinical practice. When we see topical treatments that are effective in clinical trials failing in real-life patients with AD, it may be prudent to address the possibility of poor adherence.

I'd love to see a head-to-head trial of tralokinumab vs dupilumab in the treatment of moderate to severe AD. Lacking that, Torres and colleagues report an indirect comparison of the two drugs in patients also treated with topical steroids. This study, funded by the manufacturer of tralokinumab, reported that the two drugs have similar efficacy. How much of the efficacy was due to the topical steroid use is not clear to me. I'd still love to see a head-to-head trial of tralokinumab vs dupilumab to have a better, more confident sense of their relative efficacy.

Is AD associated with brain cancer, as reported by Xin and colleagues? I'm not an expert in their methodology, but they did find a statistically significant increased risk, with an odds ratio of 1.0005. I understand the odds ratio for smoking and lung cancer to be about 80. Even if the increased odds of 1.005 — no, wait, that's 1.0005 — is truly due to AD, this tiny difference doesn't seem meaningful in any way.

Commentary: Studies Often Do Not Answer Clinical Questions in AD, May 2024

In "Atopic Dermatitis in Early Childhood and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Scandinavian Birth Cohort Study," Lerchova and colleagues found a statistically significant increased risk for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in children with atopic dermatitis. The study had a large patient population, giving it the power to identify very small differences. The researchers found increased risks for IBD, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis (UC) in children with atopic dermatitis; UC had the greatest relative risk. But I don't think this risk was clinically meaningful. About 2 in every 1000 children with atopic dermatitis had UC, whereas about 1 in every 1000 children without atopic dermatitis had UC. Even if the increased absolute risk of 1 in 1000 children was due to atopic dermatitis and not to other factors, I don't think it justifies the authors' conclusion that "these findings might be useful in identifying at-risk individuals for IBD."

Sometimes reviewing articles makes me feel like a crotchety old man. A study by Guttman-Yassky and colleagues, "Targeting IL-13 With Tralokinumab Normalizes Type 2 Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis Both Early and at 2 Years," didn't seem to test any specific hypothesis. The researchers just looked at a variety of inflammation markers in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with tralokinumab, an interleukin-13 (IL-13) antagonist. In these patients, as expected, the atopic dermatitis improved; so did the inflammatory markers. Did we learn anything clinically useful? I don't think so. We already know that IL-13 is important in atopic dermatitis because when we block IL-13, atopic dermatitis improves.

Vitamin D supplementation doesn't appear to improve atopic dermatitis, as reported by Borzutzky and colleagues in "Effect of Weekly Vitamin D Supplementation on the Severity of Atopic Dermatitis and Type 2 Immunity Biomarkers in Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial." A group of 101 children with atopic dermatitis were randomly assigned to receive oral vitamin D supplementation or placebo. The two groups improved to a similar extent. If you know me, you know I'm wondering whether they took the medication. It appears that they did, because at baseline most of the children were vitamin D deficient, and vitamin D levels improved greatly in the group treated with vitamin D but not in the placebo group.

Journals such as the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology should require articles to report absolute risk. In "Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Case-Control Study in the All of Us Database," Powers and colleagues tell us that atopic dermatitis is associated with a statistically significantly increased risk for lymphoma. This means that increased risk wasn't likely due to chance alone. The article says nothing, as far as I could tell, about how big the risk is. Does everyone get lymphoma? Or is it a one in a million risk? Without knowing the absolute risk, the relative risk doesn't tell us whether there is a clinically meaningful increased risk or not. I suspect the increased risk is small. If the incidence of lymphoma is about 2 in 10,000 and peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) account for 10% of those, even a fourfold increase in the risk for PTCL (the form of lymphoma with the highest relative risk) would not amount to much.

Traidl and colleagues report in "Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis With Baricitinib: Results From an Interim Analysis of the TREATgermany Registry" that the Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib makes atopic dermatitis better.

In "Dupilumab Therapy for Atopic Dermatitis Is Associated With Increased Risk of Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma," Hasan and colleagues report that "it requires 738 prescriptions of dupilumab to produce one case of CTCL [cutaneous T-cell lymphoma]." It seems that this finding could easily be due to 1 in 738 people with a rash thought to be severe atopic dermatitis needing dupilumab having CTCL, not atopic dermatitis, to begin with. If we were to wonder whether dupilumab causes CTCL, perhaps it would be better to study asthma patients treated with or without dupilumab.

In "Atopic Dermatitis in Early Childhood and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Scandinavian Birth Cohort Study," Lerchova and colleagues found a statistically significant increased risk for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in children with atopic dermatitis. The study had a large patient population, giving it the power to identify very small differences. The researchers found increased risks for IBD, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis (UC) in children with atopic dermatitis; UC had the greatest relative risk. But I don't think this risk was clinically meaningful. About 2 in every 1000 children with atopic dermatitis had UC, whereas about 1 in every 1000 children without atopic dermatitis had UC. Even if the increased absolute risk of 1 in 1000 children was due to atopic dermatitis and not to other factors, I don't think it justifies the authors' conclusion that "these findings might be useful in identifying at-risk individuals for IBD."

Sometimes reviewing articles makes me feel like a crotchety old man. A study by Guttman-Yassky and colleagues, "Targeting IL-13 With Tralokinumab Normalizes Type 2 Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis Both Early and at 2 Years," didn't seem to test any specific hypothesis. The researchers just looked at a variety of inflammation markers in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with tralokinumab, an interleukin-13 (IL-13) antagonist. In these patients, as expected, the atopic dermatitis improved; so did the inflammatory markers. Did we learn anything clinically useful? I don't think so. We already know that IL-13 is important in atopic dermatitis because when we block IL-13, atopic dermatitis improves.

Vitamin D supplementation doesn't appear to improve atopic dermatitis, as reported by Borzutzky and colleagues in "Effect of Weekly Vitamin D Supplementation on the Severity of Atopic Dermatitis and Type 2 Immunity Biomarkers in Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial." A group of 101 children with atopic dermatitis were randomly assigned to receive oral vitamin D supplementation or placebo. The two groups improved to a similar extent. If you know me, you know I'm wondering whether they took the medication. It appears that they did, because at baseline most of the children were vitamin D deficient, and vitamin D levels improved greatly in the group treated with vitamin D but not in the placebo group.

Journals such as the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology should require articles to report absolute risk. In "Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Case-Control Study in the All of Us Database," Powers and colleagues tell us that atopic dermatitis is associated with a statistically significantly increased risk for lymphoma. This means that increased risk wasn't likely due to chance alone. The article says nothing, as far as I could tell, about how big the risk is. Does everyone get lymphoma? Or is it a one in a million risk? Without knowing the absolute risk, the relative risk doesn't tell us whether there is a clinically meaningful increased risk or not. I suspect the increased risk is small. If the incidence of lymphoma is about 2 in 10,000 and peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) account for 10% of those, even a fourfold increase in the risk for PTCL (the form of lymphoma with the highest relative risk) would not amount to much.

Traidl and colleagues report in "Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis With Baricitinib: Results From an Interim Analysis of the TREATgermany Registry" that the Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib makes atopic dermatitis better.

In "Dupilumab Therapy for Atopic Dermatitis Is Associated With Increased Risk of Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma," Hasan and colleagues report that "it requires 738 prescriptions of dupilumab to produce one case of CTCL [cutaneous T-cell lymphoma]." It seems that this finding could easily be due to 1 in 738 people with a rash thought to be severe atopic dermatitis needing dupilumab having CTCL, not atopic dermatitis, to begin with. If we were to wonder whether dupilumab causes CTCL, perhaps it would be better to study asthma patients treated with or without dupilumab.

In "Atopic Dermatitis in Early Childhood and Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Scandinavian Birth Cohort Study," Lerchova and colleagues found a statistically significant increased risk for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in children with atopic dermatitis. The study had a large patient population, giving it the power to identify very small differences. The researchers found increased risks for IBD, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis (UC) in children with atopic dermatitis; UC had the greatest relative risk. But I don't think this risk was clinically meaningful. About 2 in every 1000 children with atopic dermatitis had UC, whereas about 1 in every 1000 children without atopic dermatitis had UC. Even if the increased absolute risk of 1 in 1000 children was due to atopic dermatitis and not to other factors, I don't think it justifies the authors' conclusion that "these findings might be useful in identifying at-risk individuals for IBD."

Sometimes reviewing articles makes me feel like a crotchety old man. A study by Guttman-Yassky and colleagues, "Targeting IL-13 With Tralokinumab Normalizes Type 2 Inflammation in Atopic Dermatitis Both Early and at 2 Years," didn't seem to test any specific hypothesis. The researchers just looked at a variety of inflammation markers in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with tralokinumab, an interleukin-13 (IL-13) antagonist. In these patients, as expected, the atopic dermatitis improved; so did the inflammatory markers. Did we learn anything clinically useful? I don't think so. We already know that IL-13 is important in atopic dermatitis because when we block IL-13, atopic dermatitis improves.

Vitamin D supplementation doesn't appear to improve atopic dermatitis, as reported by Borzutzky and colleagues in "Effect of Weekly Vitamin D Supplementation on the Severity of Atopic Dermatitis and Type 2 Immunity Biomarkers in Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial." A group of 101 children with atopic dermatitis were randomly assigned to receive oral vitamin D supplementation or placebo. The two groups improved to a similar extent. If you know me, you know I'm wondering whether they took the medication. It appears that they did, because at baseline most of the children were vitamin D deficient, and vitamin D levels improved greatly in the group treated with vitamin D but not in the placebo group.

Journals such as the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology should require articles to report absolute risk. In "Risk of Lymphoma in Patients With Atopic Dermatitis: A Case-Control Study in the All of Us Database," Powers and colleagues tell us that atopic dermatitis is associated with a statistically significantly increased risk for lymphoma. This means that increased risk wasn't likely due to chance alone. The article says nothing, as far as I could tell, about how big the risk is. Does everyone get lymphoma? Or is it a one in a million risk? Without knowing the absolute risk, the relative risk doesn't tell us whether there is a clinically meaningful increased risk or not. I suspect the increased risk is small. If the incidence of lymphoma is about 2 in 10,000 and peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCL) account for 10% of those, even a fourfold increase in the risk for PTCL (the form of lymphoma with the highest relative risk) would not amount to much.

Traidl and colleagues report in "Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis With Baricitinib: Results From an Interim Analysis of the TREATgermany Registry" that the Janus kinase inhibitor baricitinib makes atopic dermatitis better.

In "Dupilumab Therapy for Atopic Dermatitis Is Associated With Increased Risk of Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma," Hasan and colleagues report that "it requires 738 prescriptions of dupilumab to produce one case of CTCL [cutaneous T-cell lymphoma]." It seems that this finding could easily be due to 1 in 738 people with a rash thought to be severe atopic dermatitis needing dupilumab having CTCL, not atopic dermatitis, to begin with. If we were to wonder whether dupilumab causes CTCL, perhaps it would be better to study asthma patients treated with or without dupilumab.

Commentary: Choosing Treatments of AD, and Possible Connection to Learning Issues, April 2024

Not everyone with AD treated with dupilumab gets clear or almost clear in clinical trials. The study by Cork and colleagues looked to see whether those patients who did not get to clear or almost clear were still having clinically meaningful improvement. To test this, the investigators looked at patients who still had mild or worse disease and then at the proportion of those patients at week 16 who achieved a composite endpoint encompassing clinically meaningful changes in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life: ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index or ≥4-point reduction in worst scratch/itch numerical rating scale, or ≥6-point reduction in Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index/Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Significantly more patients, both clinically and statistically significantly more, receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved the composite endpoint (77.7% vs 24.6%; P < .0001).

The "success rate" reported in clinical trials underestimates how often patients can be successfully treated with dupilumab. I don't need a complicated composite outcome to know this. I just use the standardized 2-point Patient Global Assessment measure. I ask patients, "How are you doing?" If they say "Great," that's success. If they say, "Not so good," that's failure. I think about 80% of patients with AD treated with dupilumab have success based on this standard.

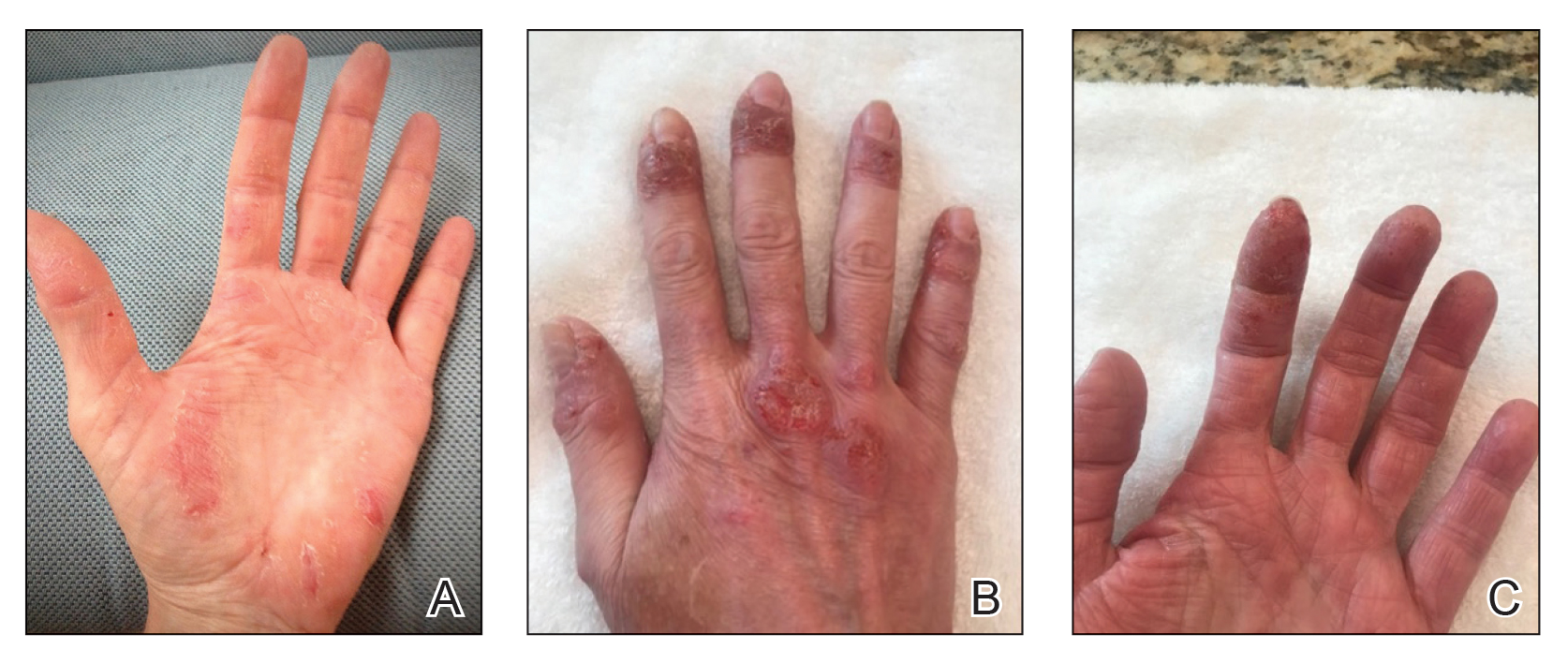

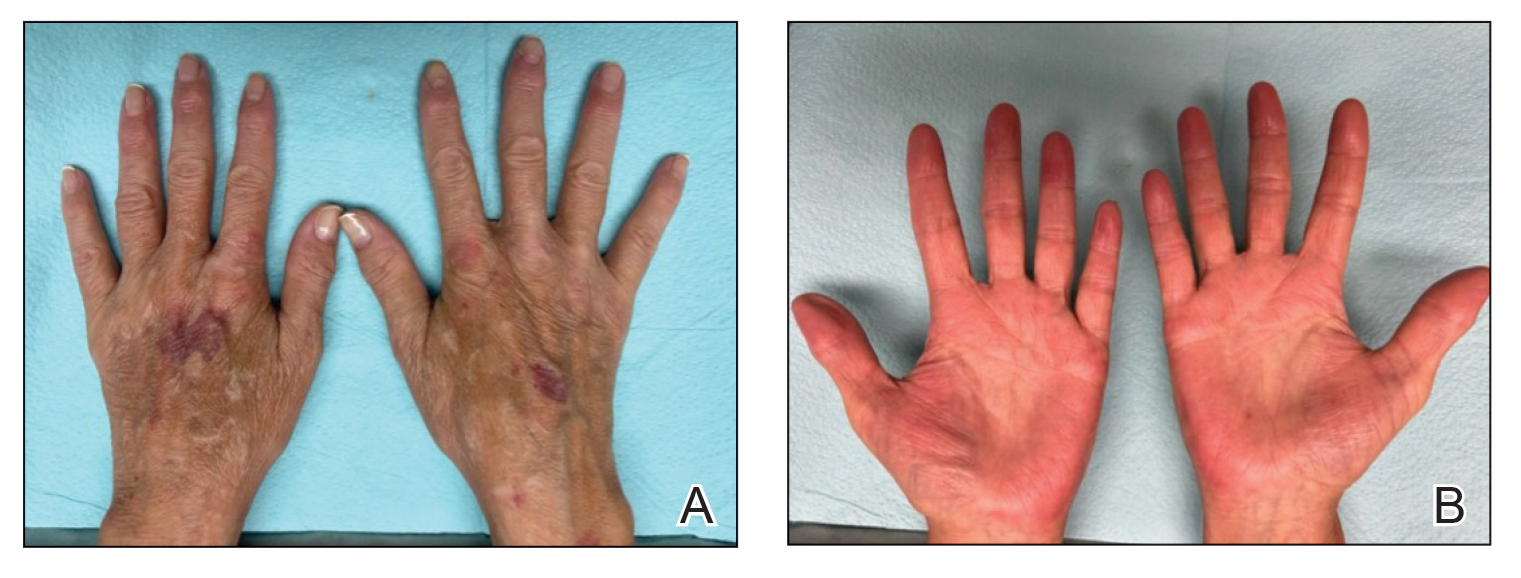

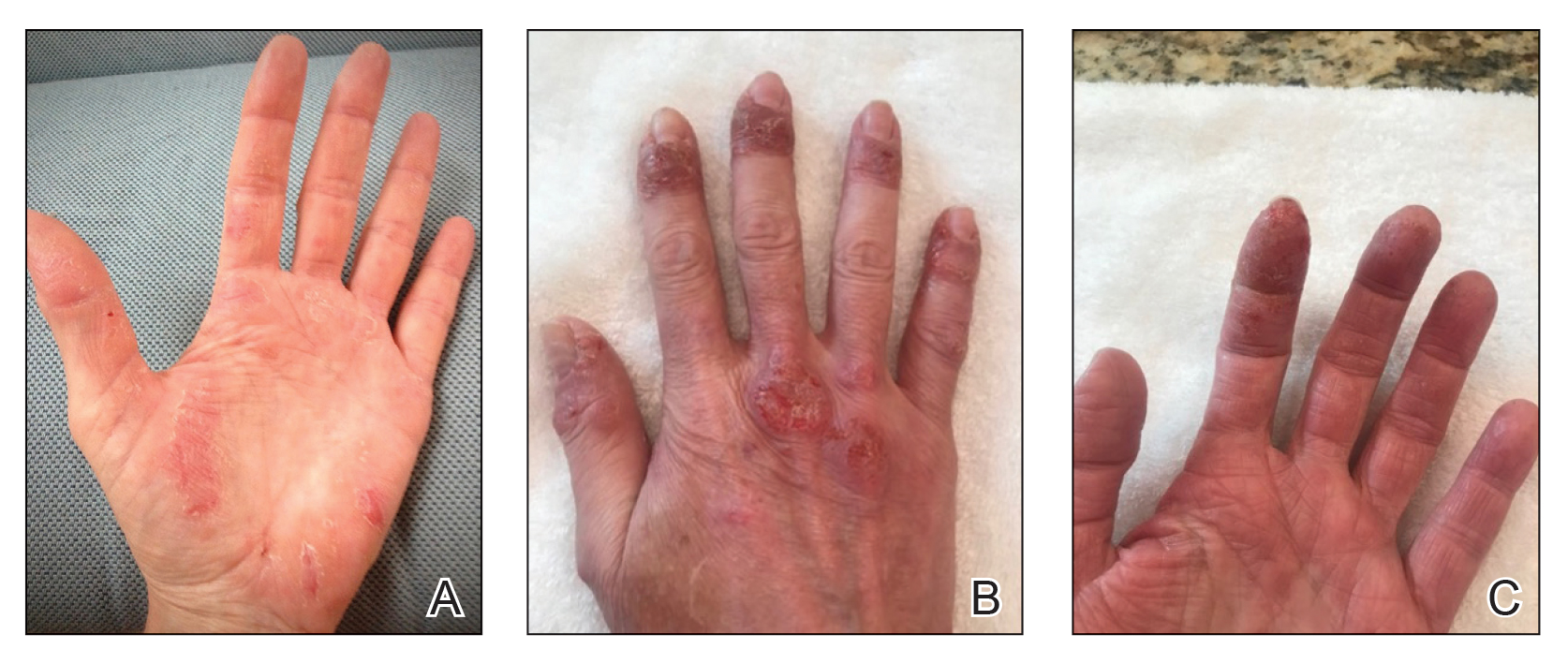

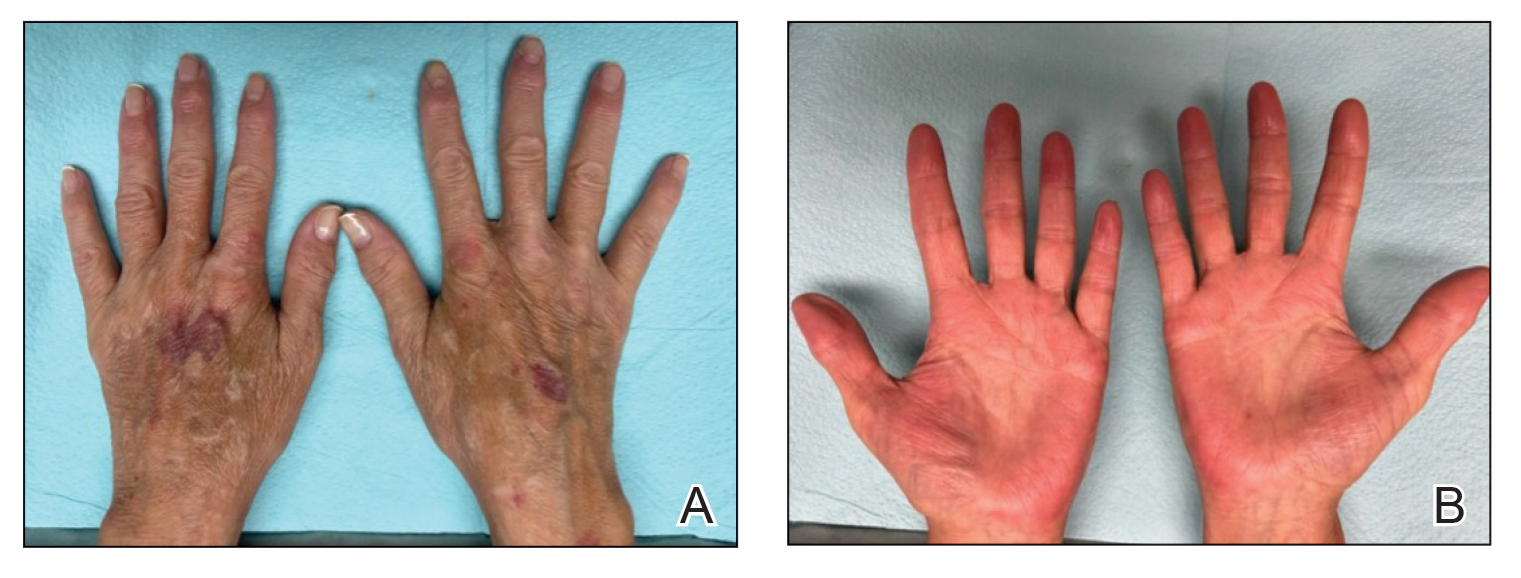

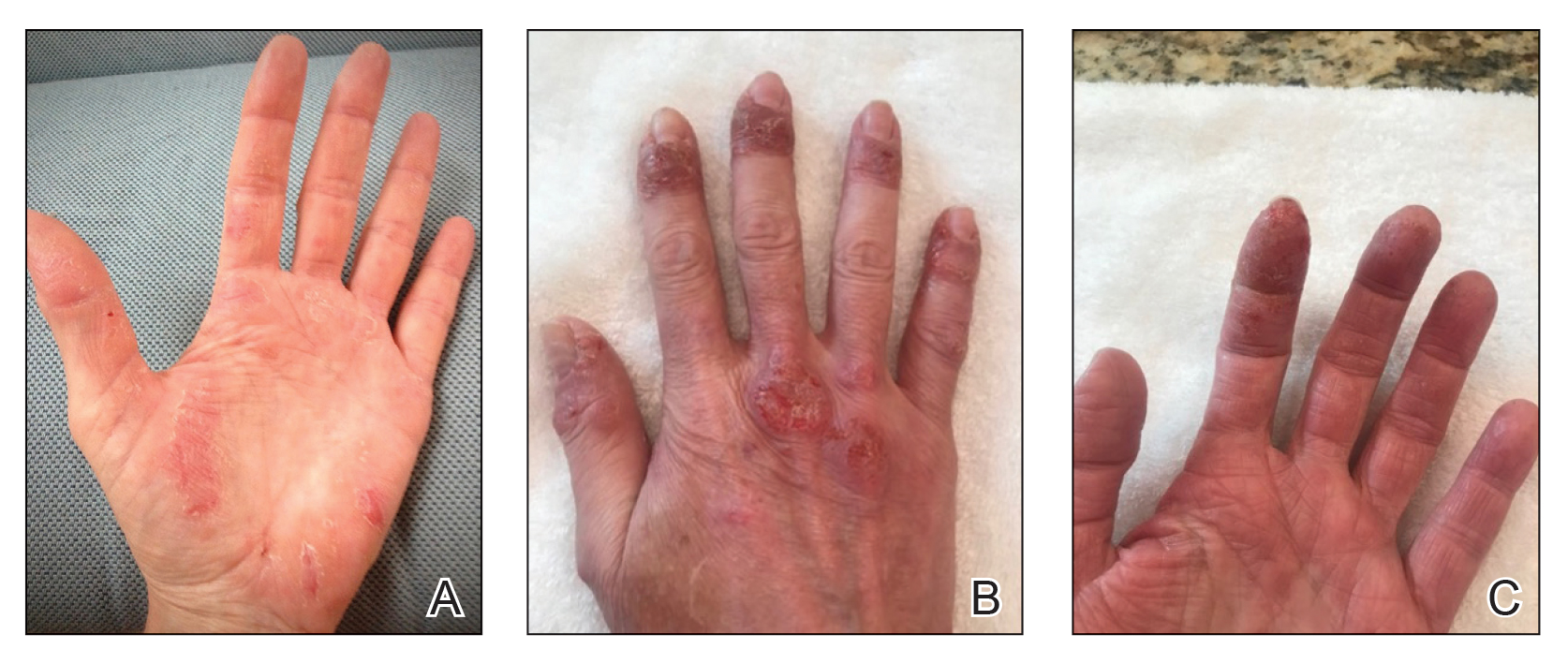

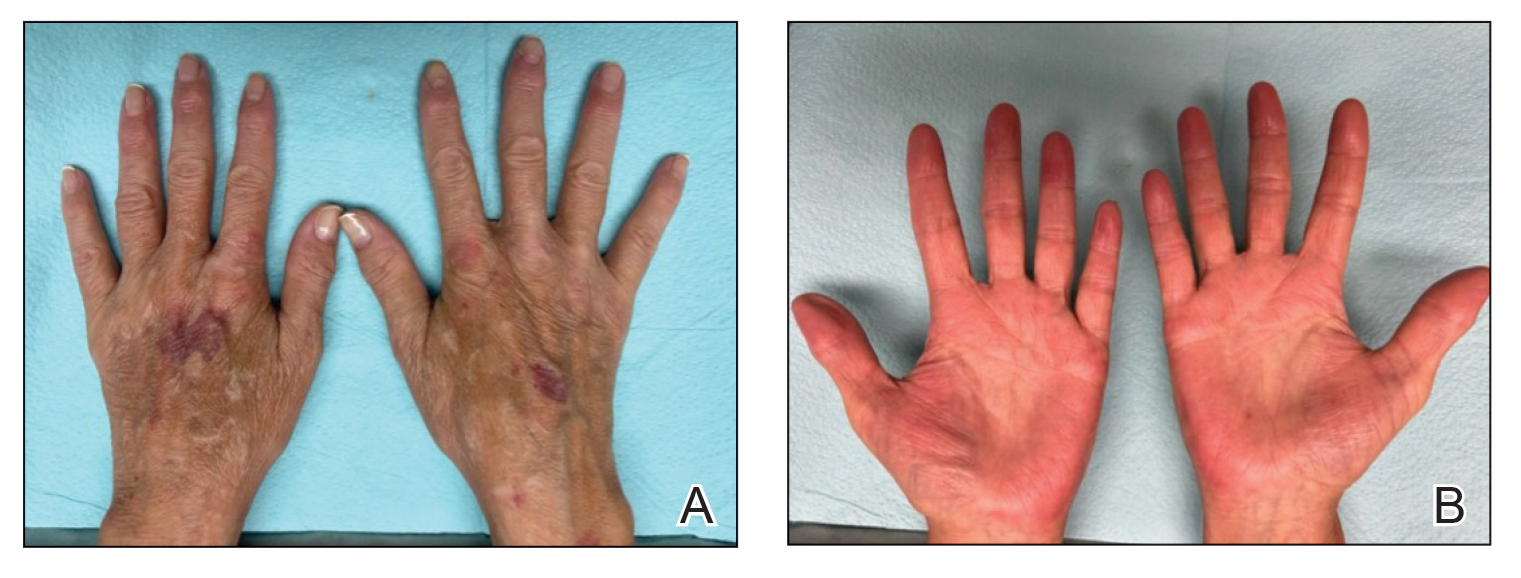

Hand dermatitis can be quite resistant to treatment. Even making a diagnosis can be challenging, as psoriasis and dermatitis of the hands looks so similar to me (and when I used to send biopsies and ask the pathologist whether it's dermatitis or psoriasis, invariably the dermatopathologist responded "yes"). The study by Kamphuis and colleagues examined the efficacy of abrocitinib in just over 100 patients with hand eczema who were enrolled in the BioDay registry. Such registries are very helpful for assessing real-world results. The drug seemed reasonably successful, with only about 30% discontinuing treatment. About two thirds of the discontinuations were due to inefficacy and about one third to an adverse event.

I think there's real value in prescribing the treatments patients want. Studies like the one by Ameen and colleagues, using a discrete-choice methodology, allows one to determine patients' average preferences. In this study, the discrete-choice approach found that patients prefer safety over other attributes. Some years ago, my colleagues and I queried patients to get a sense of their quantitative preferences for different treatments. Our study also found that patients preferred safety over other attributes. However, when we asked them to choose among different treatment options, they didn't choose the safest one. I think they believe that they prefer safety, but I'm not sure they really do. In any case, the average preference of the entire population of people with AD isn't really all that important when we've got just one patient sitting in front of us. It's that particular patient's preference that should drive the treatment plan.

Not everyone with AD treated with dupilumab gets clear or almost clear in clinical trials. The study by Cork and colleagues looked to see whether those patients who did not get to clear or almost clear were still having clinically meaningful improvement. To test this, the investigators looked at patients who still had mild or worse disease and then at the proportion of those patients at week 16 who achieved a composite endpoint encompassing clinically meaningful changes in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life: ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index or ≥4-point reduction in worst scratch/itch numerical rating scale, or ≥6-point reduction in Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index/Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Significantly more patients, both clinically and statistically significantly more, receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved the composite endpoint (77.7% vs 24.6%; P < .0001).

The "success rate" reported in clinical trials underestimates how often patients can be successfully treated with dupilumab. I don't need a complicated composite outcome to know this. I just use the standardized 2-point Patient Global Assessment measure. I ask patients, "How are you doing?" If they say "Great," that's success. If they say, "Not so good," that's failure. I think about 80% of patients with AD treated with dupilumab have success based on this standard.

Hand dermatitis can be quite resistant to treatment. Even making a diagnosis can be challenging, as psoriasis and dermatitis of the hands looks so similar to me (and when I used to send biopsies and ask the pathologist whether it's dermatitis or psoriasis, invariably the dermatopathologist responded "yes"). The study by Kamphuis and colleagues examined the efficacy of abrocitinib in just over 100 patients with hand eczema who were enrolled in the BioDay registry. Such registries are very helpful for assessing real-world results. The drug seemed reasonably successful, with only about 30% discontinuing treatment. About two thirds of the discontinuations were due to inefficacy and about one third to an adverse event.

I think there's real value in prescribing the treatments patients want. Studies like the one by Ameen and colleagues, using a discrete-choice methodology, allows one to determine patients' average preferences. In this study, the discrete-choice approach found that patients prefer safety over other attributes. Some years ago, my colleagues and I queried patients to get a sense of their quantitative preferences for different treatments. Our study also found that patients preferred safety over other attributes. However, when we asked them to choose among different treatment options, they didn't choose the safest one. I think they believe that they prefer safety, but I'm not sure they really do. In any case, the average preference of the entire population of people with AD isn't really all that important when we've got just one patient sitting in front of us. It's that particular patient's preference that should drive the treatment plan.

Not everyone with AD treated with dupilumab gets clear or almost clear in clinical trials. The study by Cork and colleagues looked to see whether those patients who did not get to clear or almost clear were still having clinically meaningful improvement. To test this, the investigators looked at patients who still had mild or worse disease and then at the proportion of those patients at week 16 who achieved a composite endpoint encompassing clinically meaningful changes in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life: ≥50% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index or ≥4-point reduction in worst scratch/itch numerical rating scale, or ≥6-point reduction in Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index/Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Significantly more patients, both clinically and statistically significantly more, receiving dupilumab vs placebo achieved the composite endpoint (77.7% vs 24.6%; P < .0001).

The "success rate" reported in clinical trials underestimates how often patients can be successfully treated with dupilumab. I don't need a complicated composite outcome to know this. I just use the standardized 2-point Patient Global Assessment measure. I ask patients, "How are you doing?" If they say "Great," that's success. If they say, "Not so good," that's failure. I think about 80% of patients with AD treated with dupilumab have success based on this standard.

Hand dermatitis can be quite resistant to treatment. Even making a diagnosis can be challenging, as psoriasis and dermatitis of the hands looks so similar to me (and when I used to send biopsies and ask the pathologist whether it's dermatitis or psoriasis, invariably the dermatopathologist responded "yes"). The study by Kamphuis and colleagues examined the efficacy of abrocitinib in just over 100 patients with hand eczema who were enrolled in the BioDay registry. Such registries are very helpful for assessing real-world results. The drug seemed reasonably successful, with only about 30% discontinuing treatment. About two thirds of the discontinuations were due to inefficacy and about one third to an adverse event.

I think there's real value in prescribing the treatments patients want. Studies like the one by Ameen and colleagues, using a discrete-choice methodology, allows one to determine patients' average preferences. In this study, the discrete-choice approach found that patients prefer safety over other attributes. Some years ago, my colleagues and I queried patients to get a sense of their quantitative preferences for different treatments. Our study also found that patients preferred safety over other attributes. However, when we asked them to choose among different treatment options, they didn't choose the safest one. I think they believe that they prefer safety, but I'm not sure they really do. In any case, the average preference of the entire population of people with AD isn't really all that important when we've got just one patient sitting in front of us. It's that particular patient's preference that should drive the treatment plan.

Commentary: Drug Comparisons and Contact Allergy in AD, February 2024

But here's the thing: We should not be making clinical judgments on the basis of differences in relative risk; clinical decisions should be based on absolute risks. Should we worry about VTE risk when treating patients with AD? This paper did not focus on absolute risk, but we can get an idea of the absolute risk by looking at the data presented in the figures in the paper. The risk for VTE in patients without AD was about 1 in 400, whereas with AD the risk was about 1 in 300, even before controlling for risk factors. This rate is sufficiently low for both groups that it doesn't seem like this risk would affect whether we would use a drug that might be associated with some minimal or theoretical increased risk for VTE.

The bottom line is that the findings of this study are reassuring, at least to me.

I'm already convinced that dupilumab is a very safe treatment for our patients with AD. The study by Simpson and colleagues looked at data from a registry of patients followed in real-life practice. The 2-year study showed no new concerns for dupilumab treatment of AD. The most common adverse event was conjunctivitis, and that was seen in only 2.4% of the patients. Perhaps the most interesting finding was that 83% of the patients who started in the study were still on dupilumab treatment at the end of 2 years. Dupilumab has a good level of efficacy and safety such that the great majority of patients who start on it seem to do well.

Dupilumab is a highly effective, very safe treatment for AD. Rademikibart Is another interleukin-4 receptor alpha-chain blocker. Not surprisingly, rademikibart also seems to be an effective, safe treatment for AD (Silverberg et al). Rademikibart may serve as another option for AD, and I imagine that it could be used if a patient on dupilumab were to develop an anti-drug antibody and lose effectiveness.

The very interesting analysis by Silverberg and colleagues looks at a new way to compare the effectiveness of different drugs for AD. They use this new approach to compare upadacitinib and dupilumab. What they found, not surprisingly, was that upadacitinib was generally more effective for AD than dupilumab. I used to think I would never see anything more effective for AD than dupilumab, but, clearly, based on head-to-head trials, upadacitinib is more effective for AD than is dupilumab. But does that greater efficacy mean that we should use upadacitinib first? We need to consider safety, too. Dupilumab works well enough for the great majority of patients and is extremely safe. I think upadacitinib is a great choice for patients who did not respond to dupilumab and could also be considered for those patients who want to take the most effective treatment option.

Trimeche and colleagues' study of contact allergens in patients with AD may change how I practice. In this study, 60% of the AD patients had positive patch test results of which 71% were considered relevant. The most frequent allergens included textile dye mix (25%), nickel (20%), cobalt (13%), isothiazolinone (9%), quanterium-15 (4%), and balsam of Peru (4%). Two patients were allergic to corticosteroids. Avoidance of relevant allergens resulted in improvement. I need to warn my AD patients to be on the lookout for contact allergens that may be causing or exacerbating their skin disease.

But here's the thing: We should not be making clinical judgments on the basis of differences in relative risk; clinical decisions should be based on absolute risks. Should we worry about VTE risk when treating patients with AD? This paper did not focus on absolute risk, but we can get an idea of the absolute risk by looking at the data presented in the figures in the paper. The risk for VTE in patients without AD was about 1 in 400, whereas with AD the risk was about 1 in 300, even before controlling for risk factors. This rate is sufficiently low for both groups that it doesn't seem like this risk would affect whether we would use a drug that might be associated with some minimal or theoretical increased risk for VTE.

The bottom line is that the findings of this study are reassuring, at least to me.

I'm already convinced that dupilumab is a very safe treatment for our patients with AD. The study by Simpson and colleagues looked at data from a registry of patients followed in real-life practice. The 2-year study showed no new concerns for dupilumab treatment of AD. The most common adverse event was conjunctivitis, and that was seen in only 2.4% of the patients. Perhaps the most interesting finding was that 83% of the patients who started in the study were still on dupilumab treatment at the end of 2 years. Dupilumab has a good level of efficacy and safety such that the great majority of patients who start on it seem to do well.

Dupilumab is a highly effective, very safe treatment for AD. Rademikibart Is another interleukin-4 receptor alpha-chain blocker. Not surprisingly, rademikibart also seems to be an effective, safe treatment for AD (Silverberg et al). Rademikibart may serve as another option for AD, and I imagine that it could be used if a patient on dupilumab were to develop an anti-drug antibody and lose effectiveness.

The very interesting analysis by Silverberg and colleagues looks at a new way to compare the effectiveness of different drugs for AD. They use this new approach to compare upadacitinib and dupilumab. What they found, not surprisingly, was that upadacitinib was generally more effective for AD than dupilumab. I used to think I would never see anything more effective for AD than dupilumab, but, clearly, based on head-to-head trials, upadacitinib is more effective for AD than is dupilumab. But does that greater efficacy mean that we should use upadacitinib first? We need to consider safety, too. Dupilumab works well enough for the great majority of patients and is extremely safe. I think upadacitinib is a great choice for patients who did not respond to dupilumab and could also be considered for those patients who want to take the most effective treatment option.

Trimeche and colleagues' study of contact allergens in patients with AD may change how I practice. In this study, 60% of the AD patients had positive patch test results of which 71% were considered relevant. The most frequent allergens included textile dye mix (25%), nickel (20%), cobalt (13%), isothiazolinone (9%), quanterium-15 (4%), and balsam of Peru (4%). Two patients were allergic to corticosteroids. Avoidance of relevant allergens resulted in improvement. I need to warn my AD patients to be on the lookout for contact allergens that may be causing or exacerbating their skin disease.

But here's the thing: We should not be making clinical judgments on the basis of differences in relative risk; clinical decisions should be based on absolute risks. Should we worry about VTE risk when treating patients with AD? This paper did not focus on absolute risk, but we can get an idea of the absolute risk by looking at the data presented in the figures in the paper. The risk for VTE in patients without AD was about 1 in 400, whereas with AD the risk was about 1 in 300, even before controlling for risk factors. This rate is sufficiently low for both groups that it doesn't seem like this risk would affect whether we would use a drug that might be associated with some minimal or theoretical increased risk for VTE.

The bottom line is that the findings of this study are reassuring, at least to me.

I'm already convinced that dupilumab is a very safe treatment for our patients with AD. The study by Simpson and colleagues looked at data from a registry of patients followed in real-life practice. The 2-year study showed no new concerns for dupilumab treatment of AD. The most common adverse event was conjunctivitis, and that was seen in only 2.4% of the patients. Perhaps the most interesting finding was that 83% of the patients who started in the study were still on dupilumab treatment at the end of 2 years. Dupilumab has a good level of efficacy and safety such that the great majority of patients who start on it seem to do well.

Dupilumab is a highly effective, very safe treatment for AD. Rademikibart Is another interleukin-4 receptor alpha-chain blocker. Not surprisingly, rademikibart also seems to be an effective, safe treatment for AD (Silverberg et al). Rademikibart may serve as another option for AD, and I imagine that it could be used if a patient on dupilumab were to develop an anti-drug antibody and lose effectiveness.

The very interesting analysis by Silverberg and colleagues looks at a new way to compare the effectiveness of different drugs for AD. They use this new approach to compare upadacitinib and dupilumab. What they found, not surprisingly, was that upadacitinib was generally more effective for AD than dupilumab. I used to think I would never see anything more effective for AD than dupilumab, but, clearly, based on head-to-head trials, upadacitinib is more effective for AD than is dupilumab. But does that greater efficacy mean that we should use upadacitinib first? We need to consider safety, too. Dupilumab works well enough for the great majority of patients and is extremely safe. I think upadacitinib is a great choice for patients who did not respond to dupilumab and could also be considered for those patients who want to take the most effective treatment option.

Trimeche and colleagues' study of contact allergens in patients with AD may change how I practice. In this study, 60% of the AD patients had positive patch test results of which 71% were considered relevant. The most frequent allergens included textile dye mix (25%), nickel (20%), cobalt (13%), isothiazolinone (9%), quanterium-15 (4%), and balsam of Peru (4%). Two patients were allergic to corticosteroids. Avoidance of relevant allergens resulted in improvement. I need to warn my AD patients to be on the lookout for contact allergens that may be causing or exacerbating their skin disease.

Commentary: JAK Inhibitors and Comorbidities in AD, December 2023

Schlösser and colleagues provide a real-world report of 48 patients treated with upadacitinib for atopic dermatitis, many of whom had previously been treated with cyclosporine and dupilumab. The upbeat authors concluded, "Overall, adverse events were mostly well tolerated." Being a cynical, glass-is-half-empty kind of person, I wondered what that meant. Most patients (56%) reported adverse events, the most common being acne (25% of patients treated), nausea (13%), respiratory tract infections (10%), and herpes virus (8%). The herpes virus signal is not just a bit of a concern for me, but it also makes it hard for me to convince patients to take a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, as when I even mention herpes, patients reply, often rather emphatically, "I don't want herpes!" I'll be encouraging patients to get vaccinated for shingles when starting them on JAK inhibitors.

Dupilumab seems to work great in real-life use. In Martinez-Cabriales and colleagues' study of 62 children age < 12 with atopic dermatitis, only four discontinued the treatment. One of these was a nonresponder who took only one injection and had flushing, and one of the other three discontinued because their skin had completely cleared.

When I saw the title of Rand and colleagues' article, "Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison of the Long-Term Efficacy Maintenance and Adverse Event Rates of Lebrikizumab Versus Dupilumab in Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis," I thought, Oh, this is great — a head-to-head, long-term trial comparing lebrikizumab and dupilumab. I was disappointed to find that this was simply a retrospective analysis of data reported from different studies. The study found little difference in efficacy or safety of the two drugs. Both seem to be excellent medications for atopic dermatitis.

Here's another study (Zhou et al) that reports possible increased risk for a comorbidity (cognitive dysfunction) associated with atopic dermatitis. This study reports that there is an elevated hazard ratio that is statistically significant; the article fails to report what the increased absolute risk is for cognitive dysfunction associated with atopic dermatitis. My guess is that it is small and probably clinically unimportant. The hazard ratio for developing dementia was 1.16. It's hard to know how that translates into absolute risk, but my brilliant friend and former partner, Dr Alan Fleischer, once told me that the odds ratio for smoking and lung cancer is something like 100; the hazard ratio is in the range of 20. On the basis of a hazard ratio of 1.16, I don't think patients with atopic dermatitis need to be any more worried about dementia than those without. (Though, to be honest, I think we can all be worried about developing dementia.)

In this tour de force analysis of 83 trials with over 20,000 participants, Drucker and colleagues determined that high doses of abrocitinib and upadacitinib are more effective than even dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. The standard doses of these JAK inhibitors were similar in efficacy to dupilumab. I think it's safe to say that JAK inhibitors are, at least at their high doses, more effective than dupilumab, but safety remains a critical factor in treatment decision-making. I think JAK inhibitors are a great option for patients who need the most effective treatment or who fail to respond to dupilumab.

The title of the article by Oh and colleagues, "Increased Risk of Renal Malignancy in Patients With Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis," seems like it could terrify patients. The study involved an analysis of an enormous number of people, including tens of thousands with atopic dermatitis and millions of controls. The investigators did find statistically significant differences in the rate of malignancy. The rate of renal cancer was about 1.6 per 10,000 person-years for people without atopic dermatitis or people with mild atopic dermatitis; the rate was about 2.5 per 10,000 people for patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. While the rate of renal cancer was statistically significantly higher in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (ie, the higher rate was unlikely to be occurring due to chance alone), these patients have very little risk for renal malignancy. The authors' conclusion that regular checkups for renal malignancy are recommended for patients with severe atopic dermatitis seems unnecessary to me.

Schlösser and colleagues provide a real-world report of 48 patients treated with upadacitinib for atopic dermatitis, many of whom had previously been treated with cyclosporine and dupilumab. The upbeat authors concluded, "Overall, adverse events were mostly well tolerated." Being a cynical, glass-is-half-empty kind of person, I wondered what that meant. Most patients (56%) reported adverse events, the most common being acne (25% of patients treated), nausea (13%), respiratory tract infections (10%), and herpes virus (8%). The herpes virus signal is not just a bit of a concern for me, but it also makes it hard for me to convince patients to take a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, as when I even mention herpes, patients reply, often rather emphatically, "I don't want herpes!" I'll be encouraging patients to get vaccinated for shingles when starting them on JAK inhibitors.

Dupilumab seems to work great in real-life use. In Martinez-Cabriales and colleagues' study of 62 children age < 12 with atopic dermatitis, only four discontinued the treatment. One of these was a nonresponder who took only one injection and had flushing, and one of the other three discontinued because their skin had completely cleared.

When I saw the title of Rand and colleagues' article, "Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison of the Long-Term Efficacy Maintenance and Adverse Event Rates of Lebrikizumab Versus Dupilumab in Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis," I thought, Oh, this is great — a head-to-head, long-term trial comparing lebrikizumab and dupilumab. I was disappointed to find that this was simply a retrospective analysis of data reported from different studies. The study found little difference in efficacy or safety of the two drugs. Both seem to be excellent medications for atopic dermatitis.

Here's another study (Zhou et al) that reports possible increased risk for a comorbidity (cognitive dysfunction) associated with atopic dermatitis. This study reports that there is an elevated hazard ratio that is statistically significant; the article fails to report what the increased absolute risk is for cognitive dysfunction associated with atopic dermatitis. My guess is that it is small and probably clinically unimportant. The hazard ratio for developing dementia was 1.16. It's hard to know how that translates into absolute risk, but my brilliant friend and former partner, Dr Alan Fleischer, once told me that the odds ratio for smoking and lung cancer is something like 100; the hazard ratio is in the range of 20. On the basis of a hazard ratio of 1.16, I don't think patients with atopic dermatitis need to be any more worried about dementia than those without. (Though, to be honest, I think we can all be worried about developing dementia.)

In this tour de force analysis of 83 trials with over 20,000 participants, Drucker and colleagues determined that high doses of abrocitinib and upadacitinib are more effective than even dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. The standard doses of these JAK inhibitors were similar in efficacy to dupilumab. I think it's safe to say that JAK inhibitors are, at least at their high doses, more effective than dupilumab, but safety remains a critical factor in treatment decision-making. I think JAK inhibitors are a great option for patients who need the most effective treatment or who fail to respond to dupilumab.

The title of the article by Oh and colleagues, "Increased Risk of Renal Malignancy in Patients With Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis," seems like it could terrify patients. The study involved an analysis of an enormous number of people, including tens of thousands with atopic dermatitis and millions of controls. The investigators did find statistically significant differences in the rate of malignancy. The rate of renal cancer was about 1.6 per 10,000 person-years for people without atopic dermatitis or people with mild atopic dermatitis; the rate was about 2.5 per 10,000 people for patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. While the rate of renal cancer was statistically significantly higher in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (ie, the higher rate was unlikely to be occurring due to chance alone), these patients have very little risk for renal malignancy. The authors' conclusion that regular checkups for renal malignancy are recommended for patients with severe atopic dermatitis seems unnecessary to me.

Schlösser and colleagues provide a real-world report of 48 patients treated with upadacitinib for atopic dermatitis, many of whom had previously been treated with cyclosporine and dupilumab. The upbeat authors concluded, "Overall, adverse events were mostly well tolerated." Being a cynical, glass-is-half-empty kind of person, I wondered what that meant. Most patients (56%) reported adverse events, the most common being acne (25% of patients treated), nausea (13%), respiratory tract infections (10%), and herpes virus (8%). The herpes virus signal is not just a bit of a concern for me, but it also makes it hard for me to convince patients to take a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, as when I even mention herpes, patients reply, often rather emphatically, "I don't want herpes!" I'll be encouraging patients to get vaccinated for shingles when starting them on JAK inhibitors.

Dupilumab seems to work great in real-life use. In Martinez-Cabriales and colleagues' study of 62 children age < 12 with atopic dermatitis, only four discontinued the treatment. One of these was a nonresponder who took only one injection and had flushing, and one of the other three discontinued because their skin had completely cleared.

When I saw the title of Rand and colleagues' article, "Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison of the Long-Term Efficacy Maintenance and Adverse Event Rates of Lebrikizumab Versus Dupilumab in Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis," I thought, Oh, this is great — a head-to-head, long-term trial comparing lebrikizumab and dupilumab. I was disappointed to find that this was simply a retrospective analysis of data reported from different studies. The study found little difference in efficacy or safety of the two drugs. Both seem to be excellent medications for atopic dermatitis.