User login

Utilization, Cost, and Prescription Trends of Antipsychotics Prescribed by Dermatologists for Medicare Patients

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

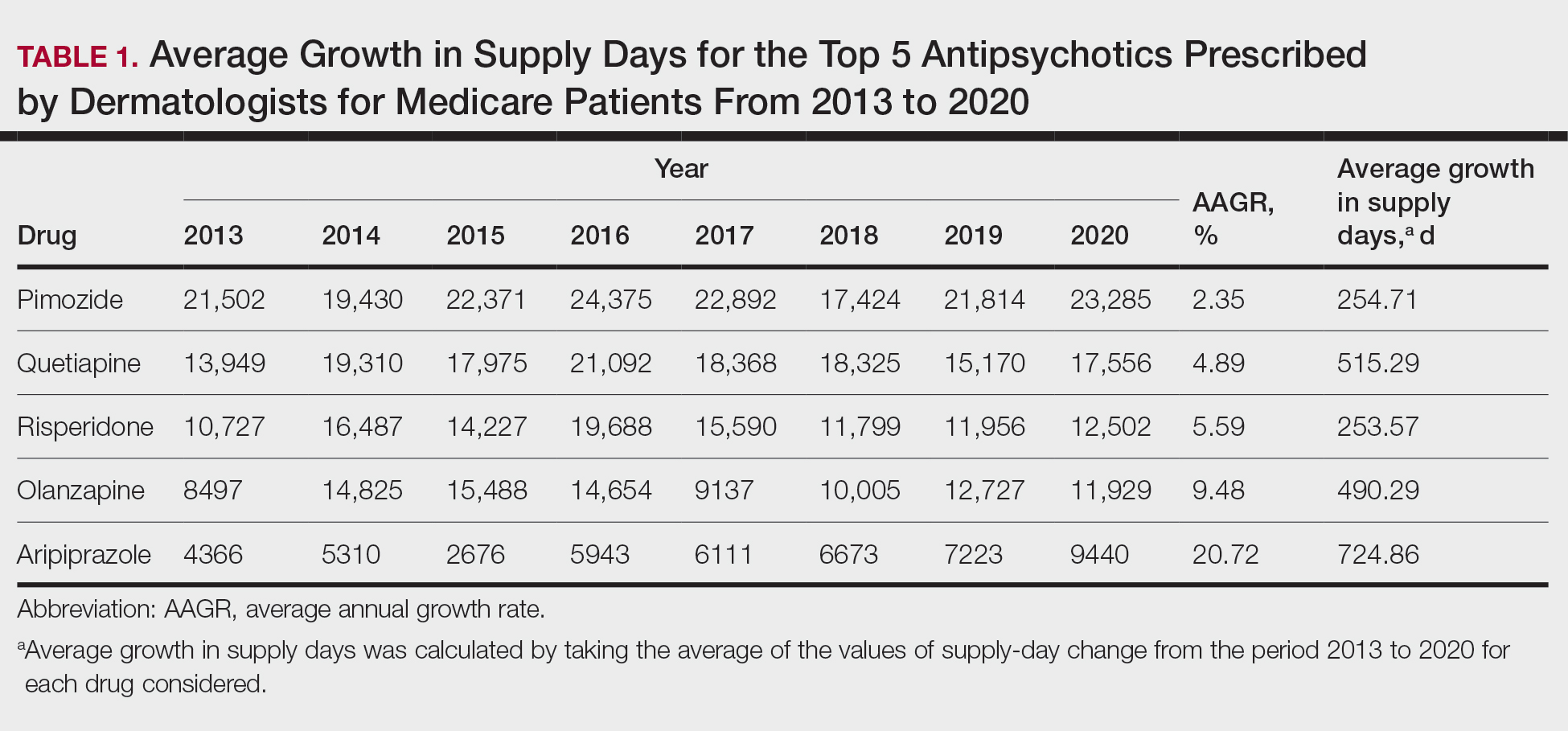

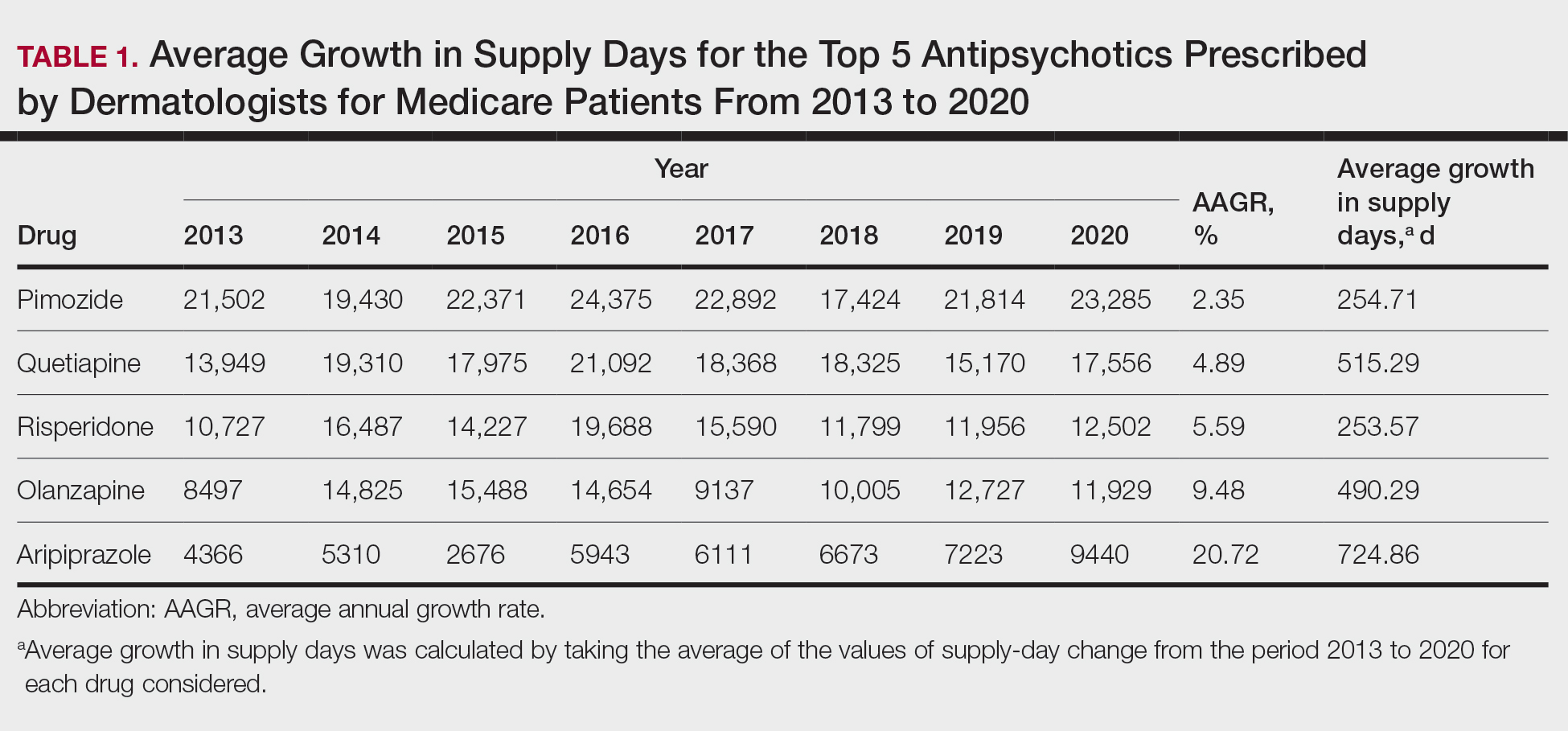

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

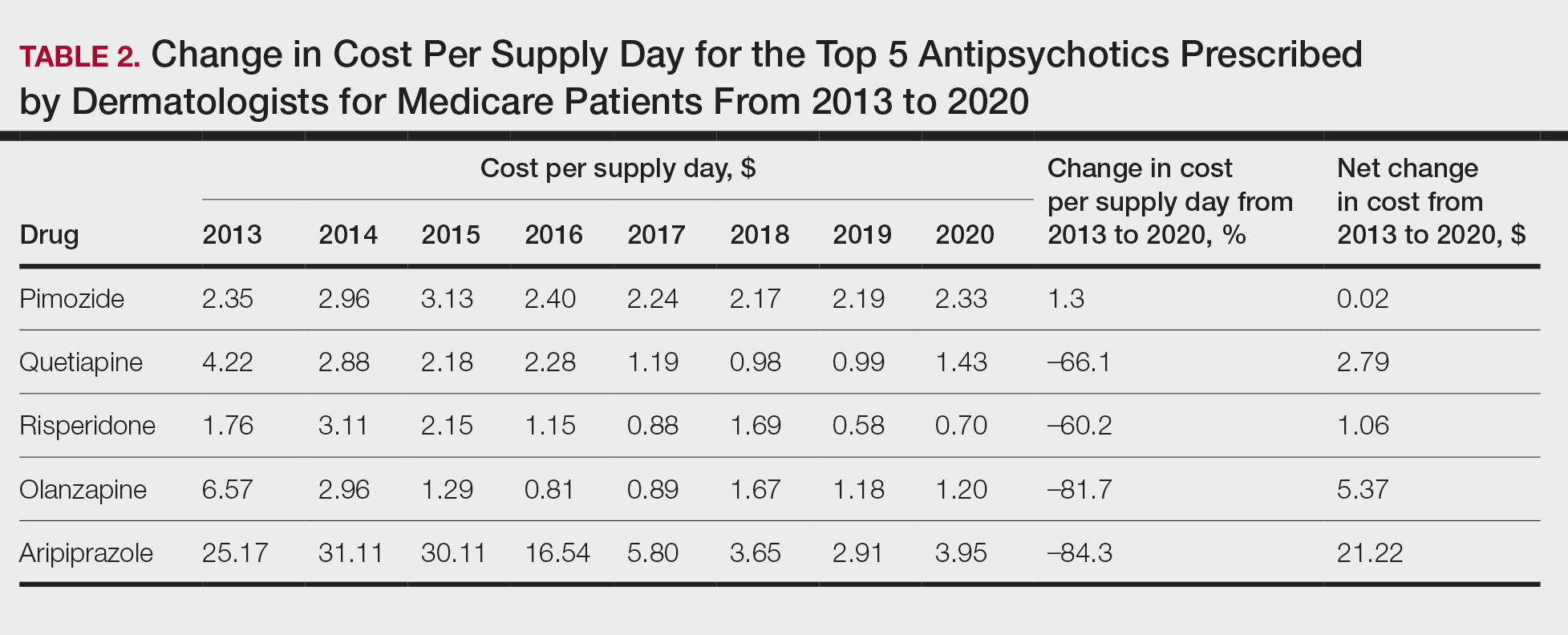

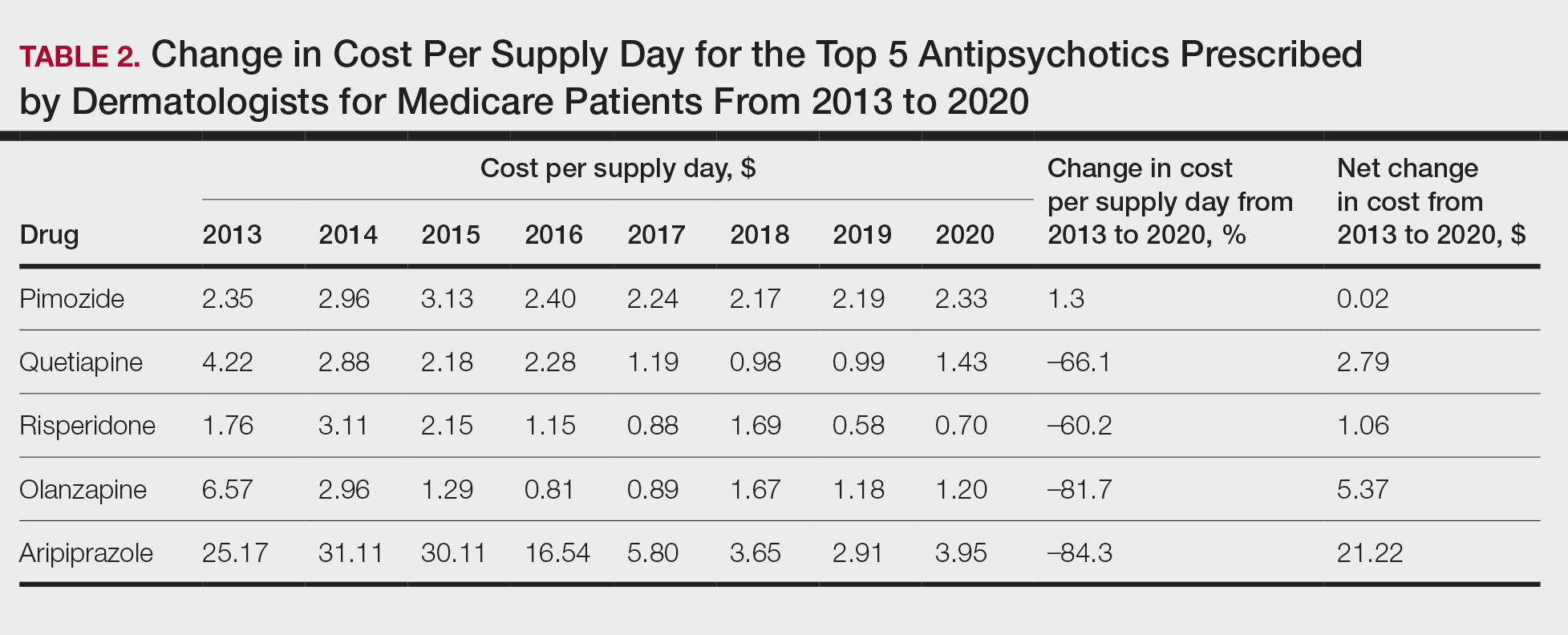

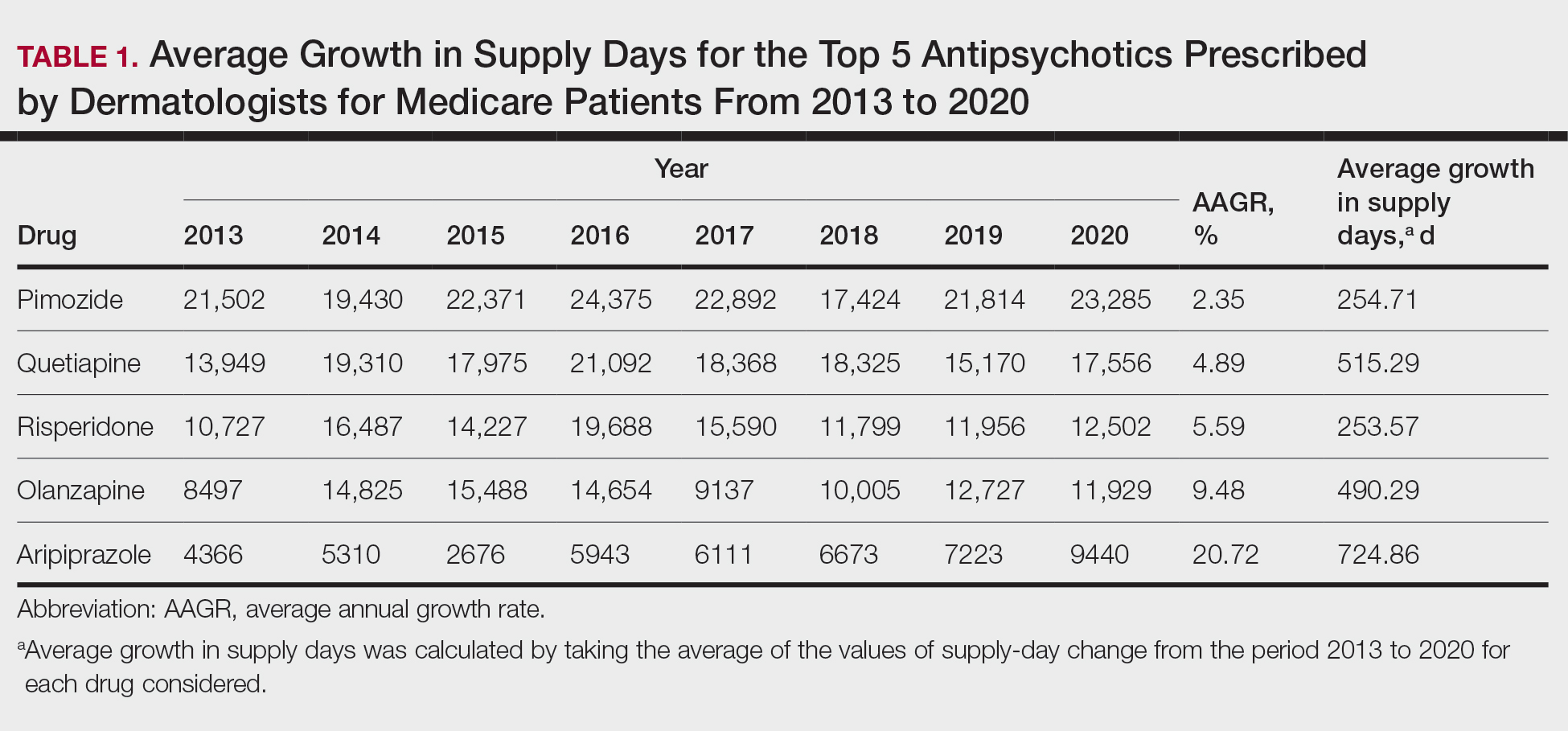

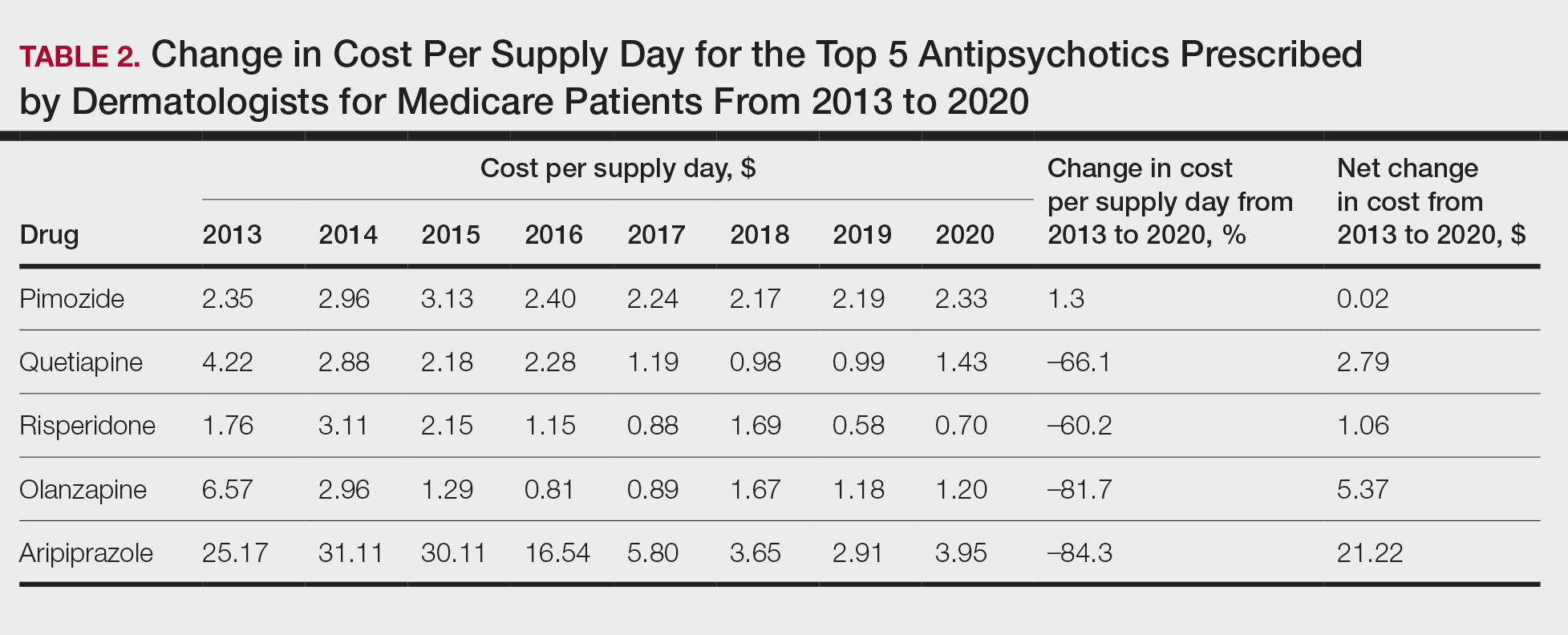

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

To the Editor:

Patients with primary psychiatric disorders with dermatologic manifestations often seek treatment from dermatologists instead of psychiatrists.1 For example, patients with delusions of parasitosis may lack insight into the underlying etiology of their disease and instead fixate on establishing an organic cause for their symptoms. As a result, it is an increasingly common practice for dermatologists to diagnose and treat psychiatric conditions.1 The goal of this study was to evaluate trends for the top 5 antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists in the Medicare Part D database.

In this retrospective analysis, we consulted the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data for January 2013 through December 2020, which is provided to the public by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.2 Only prescribing data from dermatologists were included in this study by using the built-in filter on the website to select “dermatology” as the prescriber type. All other provider types were excluded. We chose the top 5 most prescribed antipsychotics based on the number of supply days reported. Supply days—defined by Medicare as the number of days’ worth of medication that is prescribed—were used as a metric for utilization; therefore, each drug’s total supply days prescribed by dermatologists were calculated using this combined filter of drug name and total supply days using the database.

To analyze utilization over time, the annual average growth rate (AAGR) was calculated by determining the growth rate in total supply days annually from 2013 to 2020 and then averaging those rates to determine the overall AAGR. For greater clinical relevance, we calculated the average growth in supply days for the entire study period by determining the difference in the number of supply days for each year and then averaging these values. This was done to consider overall trends across dermatology rather than individual dermatologist prescribing patterns.

Based on our analysis, the antipsychotics most frequently prescribed by dermatologists for Medicare patients from January 2013 to December 2020 were pimozide, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole. The AAGR for each drug was 2.35%, 4.89%, 5.59%, 9.48%, and 20.72%, respectively, which is consistent with increased utilization over the study period for all 5 drugs (Table 1). The change in cost per supply day for the same period was 1.3%, –66.1%, –60.2%, –81.7%, and –84.3%, respectively. The net difference in cost per supply day over this entire period was $0.02, –$2.79, –$1.06, –$5.37, and –$21.22, respectively (Table 2).

There were several limitations to our study. Our analysis was limited to the Medicare population. Uninsured patients and those with Medicare Advantage or private health insurance plans were not included. In the Medicare database, only prescribers who prescribed a medication 10 times or more were recorded; therefore, some prescribers were not captured.

Although there was an increase in the dermatologic use of all 5 drugs in this study, perhaps the most marked growth was exhibited by aripiprazole, which had an AAGR of 20.72% (Table 1). Affordability may have been a factor, as the most marked reduction in price per supply day was noted for aripiprazole during the study period. Pimozide, which traditionally has been the first-line therapy for delusions of parasitosis, is the only first-generation antipsychotic drug among the 5 most frequently prescribed antipsychotics.3 Interestingly, pimozide had the lowest AAGR compared with the 4 second-generation antipsychotics. This finding also is corroborated by the average growth in supply days. While pimozide is a first-generation antipsychotic and had the lowest AAGR, pimozide still was the most prescribed antipsychotic in this study. Considering the average growth in Medicare beneficiaries during the study period was 2.70% per year,2 the AAGR of the 4 other drugs excluding pimozide shows that this growth was larger than what can be attributed to an increase in population size.

The most common conditions for which dermatologists prescribe antipsychotics are primary delusional infestation disorders as well as a range of self-inflicted dermatologic manifestations of dermatitis artefacta.4 Particularly, dermatologist-prescribed antipsychotics are first-line for these conditions in which perception of a persistent disease state is present.4 Importantly, dermatologists must differentiate between other dermatology-related psychiatric conditions such as trichotillomania and body dysmorphic disorder, which tend to respond better to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.4 Our data suggest that dermatologists are increasing their utilization of second-generation antipsychotics at a higher rate than first-generation antipsychotics, likely due to the lower risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. Patients are more willing to initiate a trial of psychiatric medication when it is prescribed by a dermatologist vs a psychiatrist due to lack of perceived stigma, which can lead to greater treatment compliance rates.5 As mentioned previously, as part of the differential, dermatologists also can effectively prescribe medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for symptoms including anxiety, trichotillomania, body dysmorphic disorder, or secondary psychiatric disorders as a result of the burden of skin disease.5

In many cases, a dermatologist may be the first and only specialist to evaluate patients with conditions that overlap within the jurisdiction of dermatology and psychiatry. It is imperative that dermatologists feel comfortable treating this vulnerable patient population. As demonstrated by Medicare prescription data, the increasing utilization of antipsychotics in our specialty demands that dermatologists possess an adequate working knowledge of psychopharmacology, which may be accomplished during residency training through several directives, including focused didactic sessions, elective rotations in psychiatry, increased exposure to psychocutaneous lectures at national conferences, and finally through the establishment of joint dermatology-psychiatry clinics with interdepartmental collaboration.

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

- Weber MB, Recuero JK, Almeida CS. Use of psychiatric drugs in dermatology. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:133-143. doi:10.1016/j.abd.2019.12.002

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: part D prescriber. Updated September 10, 2024. Accessed October 7, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/data -research/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-utilization-payment-data/part-d-prescriber

- Bolognia J, Schaffe JV, Lorenzo C. Dermatology. In: Duncan KO, Koo JYM, eds. Psychocutaneous Diseases. Elsevier; 2017:128-136.

- Gupta MA, Vujcic B, Pur DR, et al. Use of antipsychotic drugs in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36:765-773. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.08.006

- Jafferany M, Stamu-O’Brien C, Mkhoyan R, et al. Psychotropic drugs in dermatology: a dermatologist’s approach and choice of medications. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:E13385. doi:10.1111/dth.13385

Practice Points

- Dermatologists are frontline medical providers who can be useful in screening for primary psychiatric disorders in patients with dermatologic manifestations.

- Second-generation antipsychotics are effective for treating many psychiatric disorders.

Analysis of Nail Excision Practice Patterns in the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012-2017

To the Editor:

Partial or total nail plate excisions commonly are used for the treatment of onychocryptosis and nail spicules. Procedures involving the nail unit require advanced technical skills to achieve optimal functional and aesthetic outcomes, avoid complications, and minimize health care costs. Data on the frequency of nail plate excisions performed by dermatologists and their relative frequency compared to other medical providers are limited. The objective of our study was to analyze trends in nail excision practice patterns among medical providers in the United States.

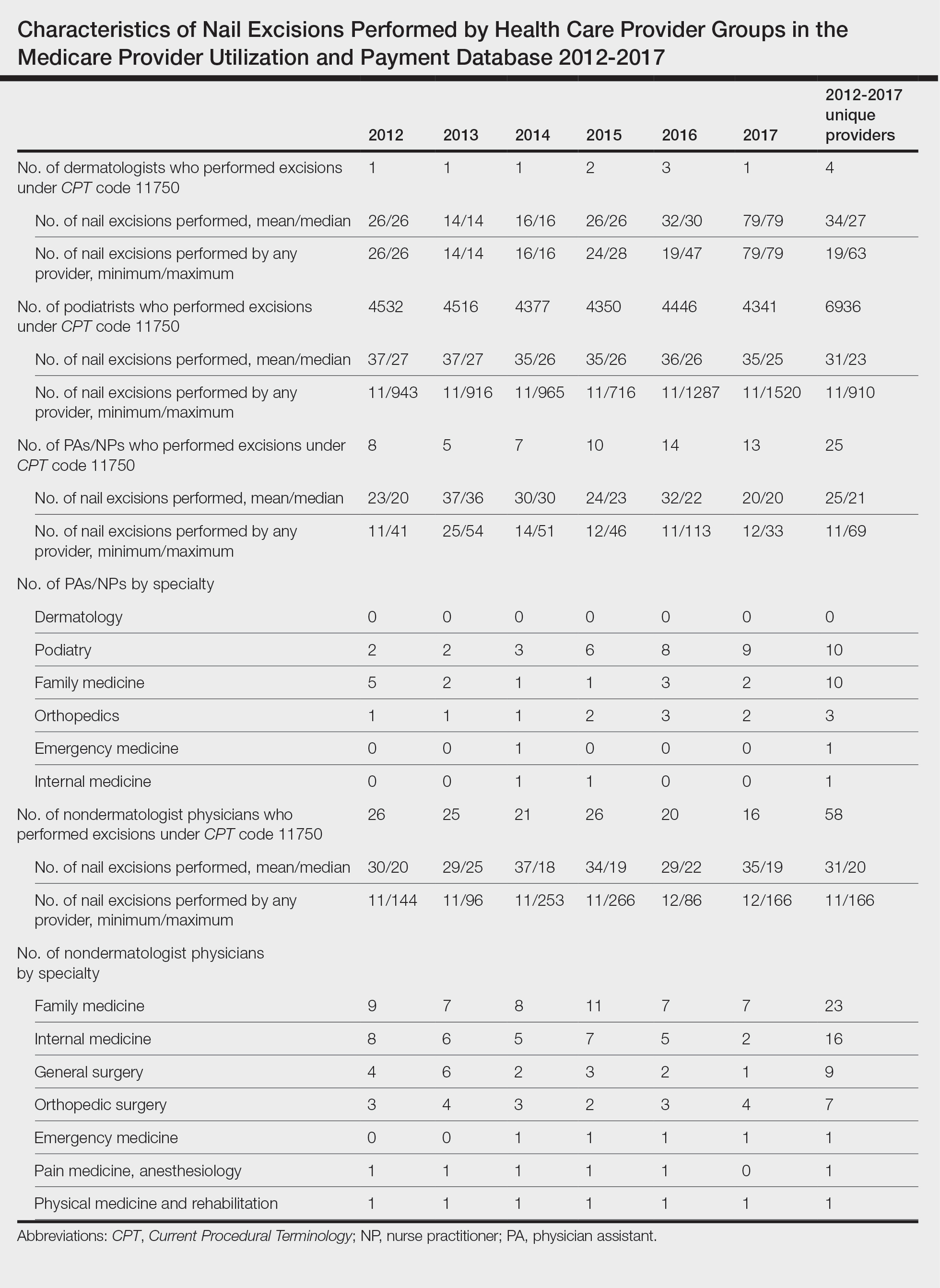

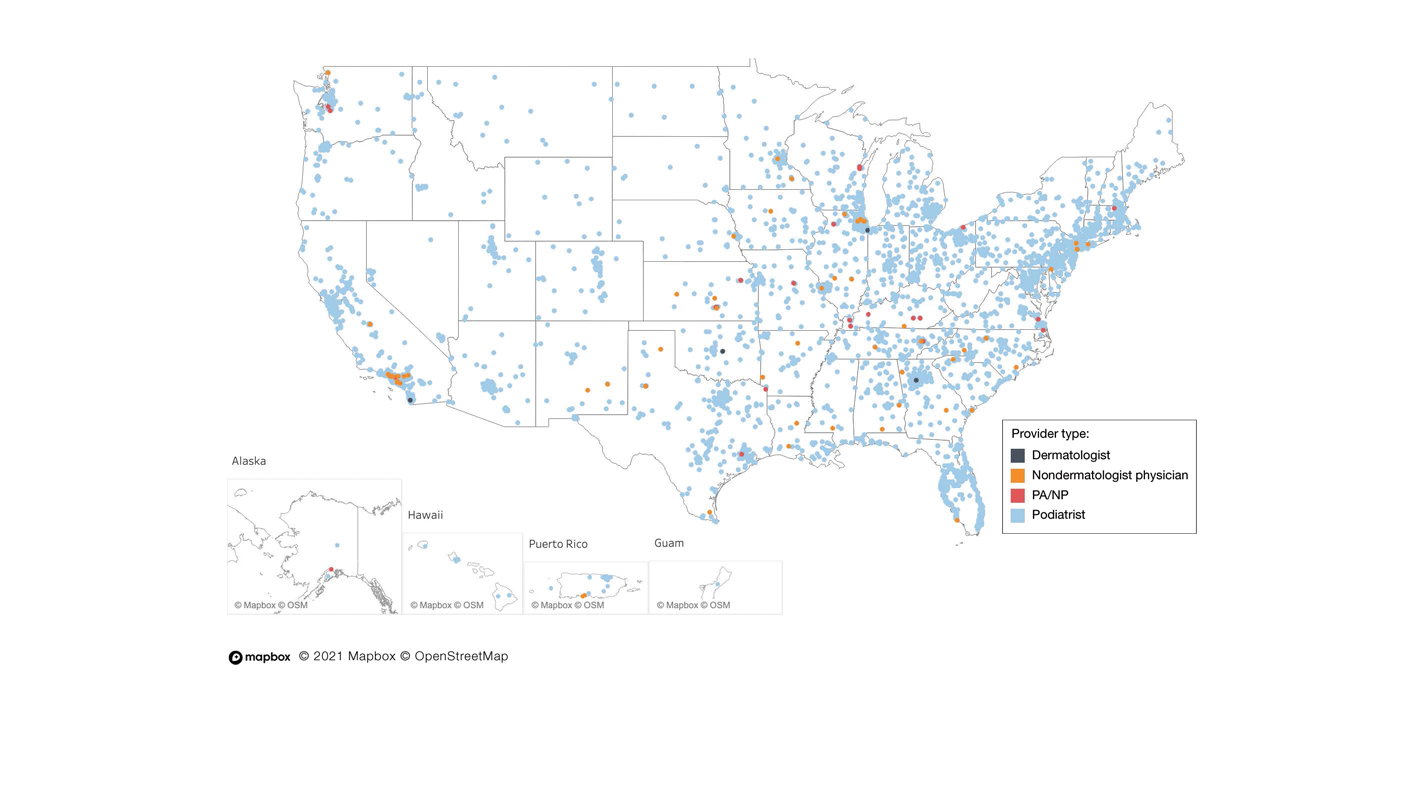

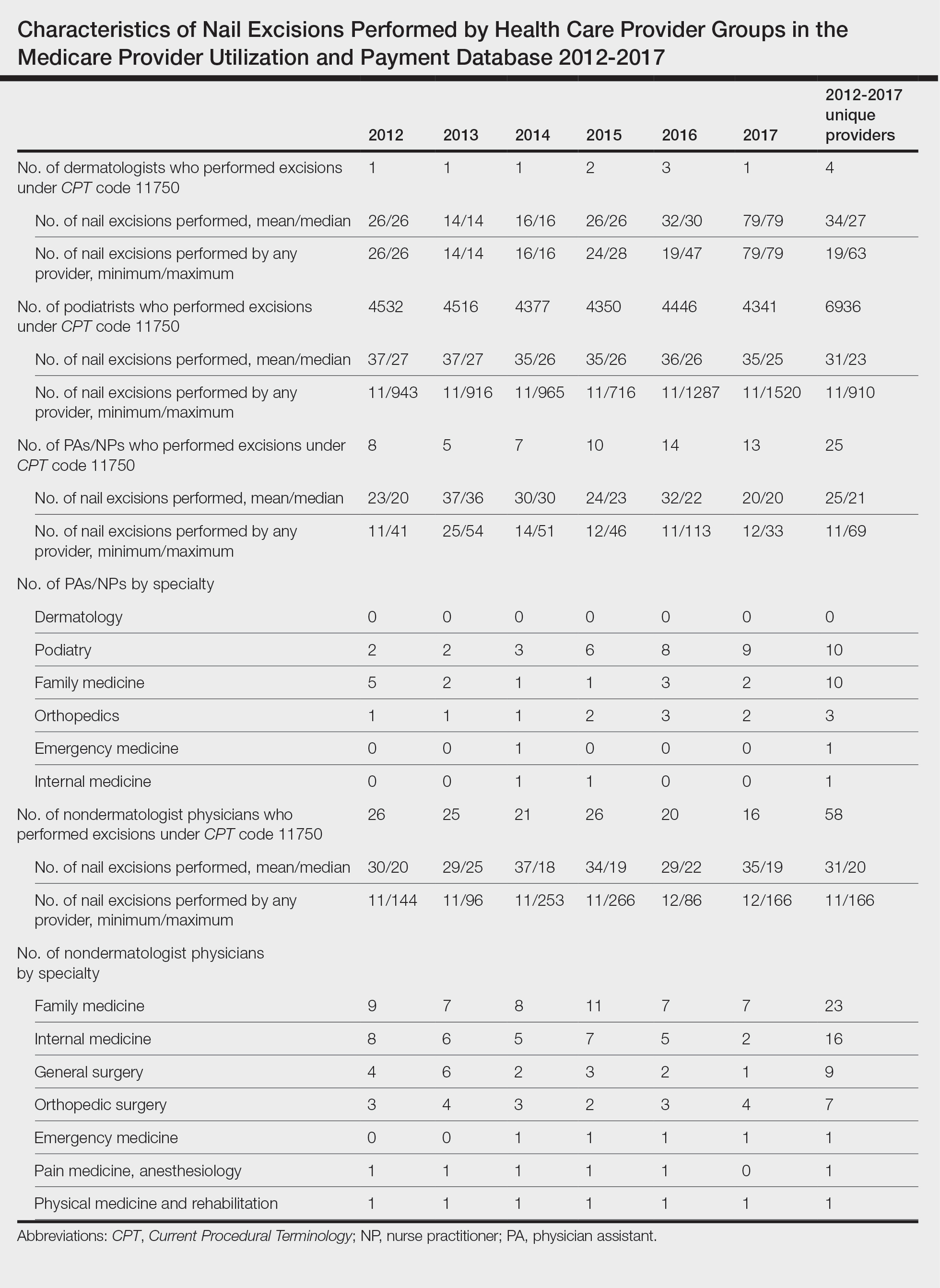

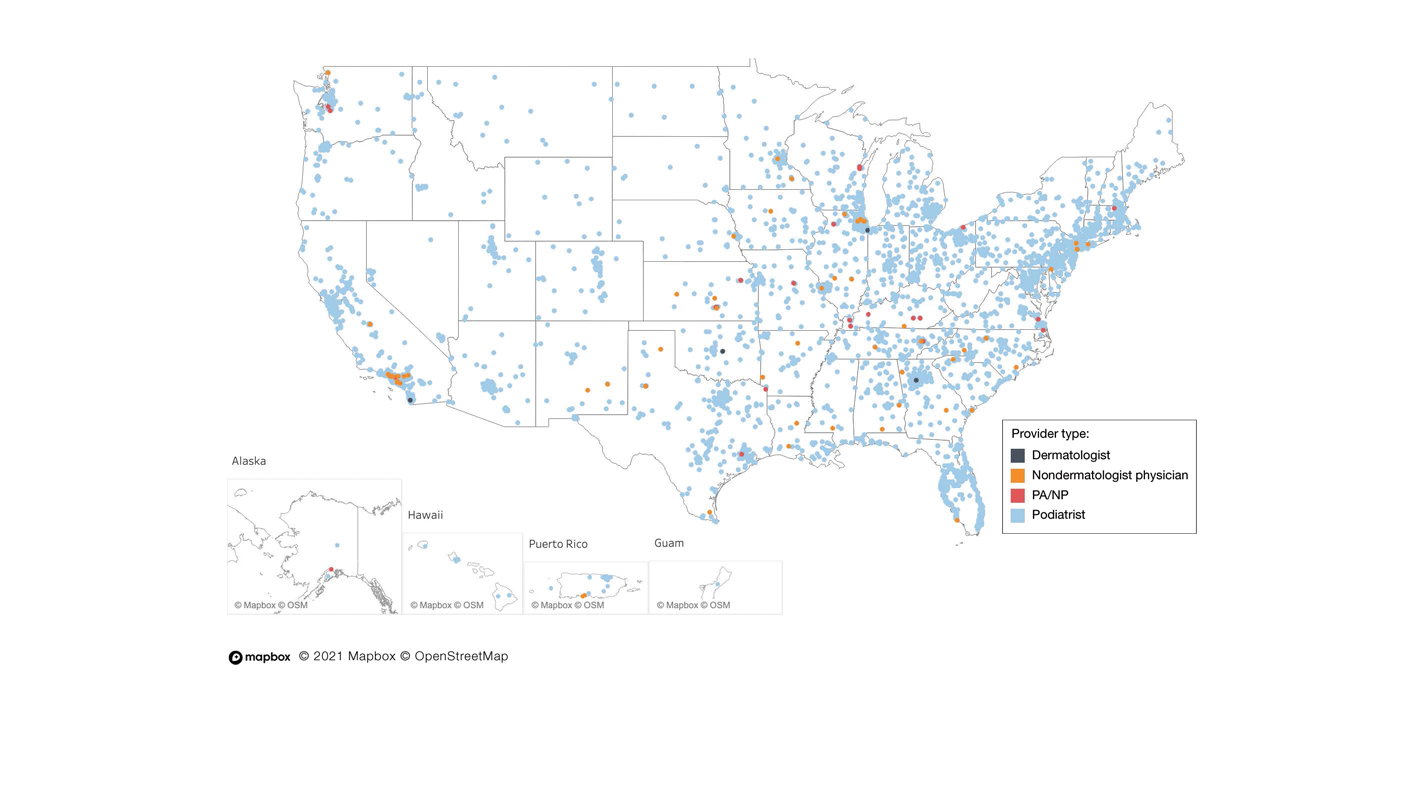

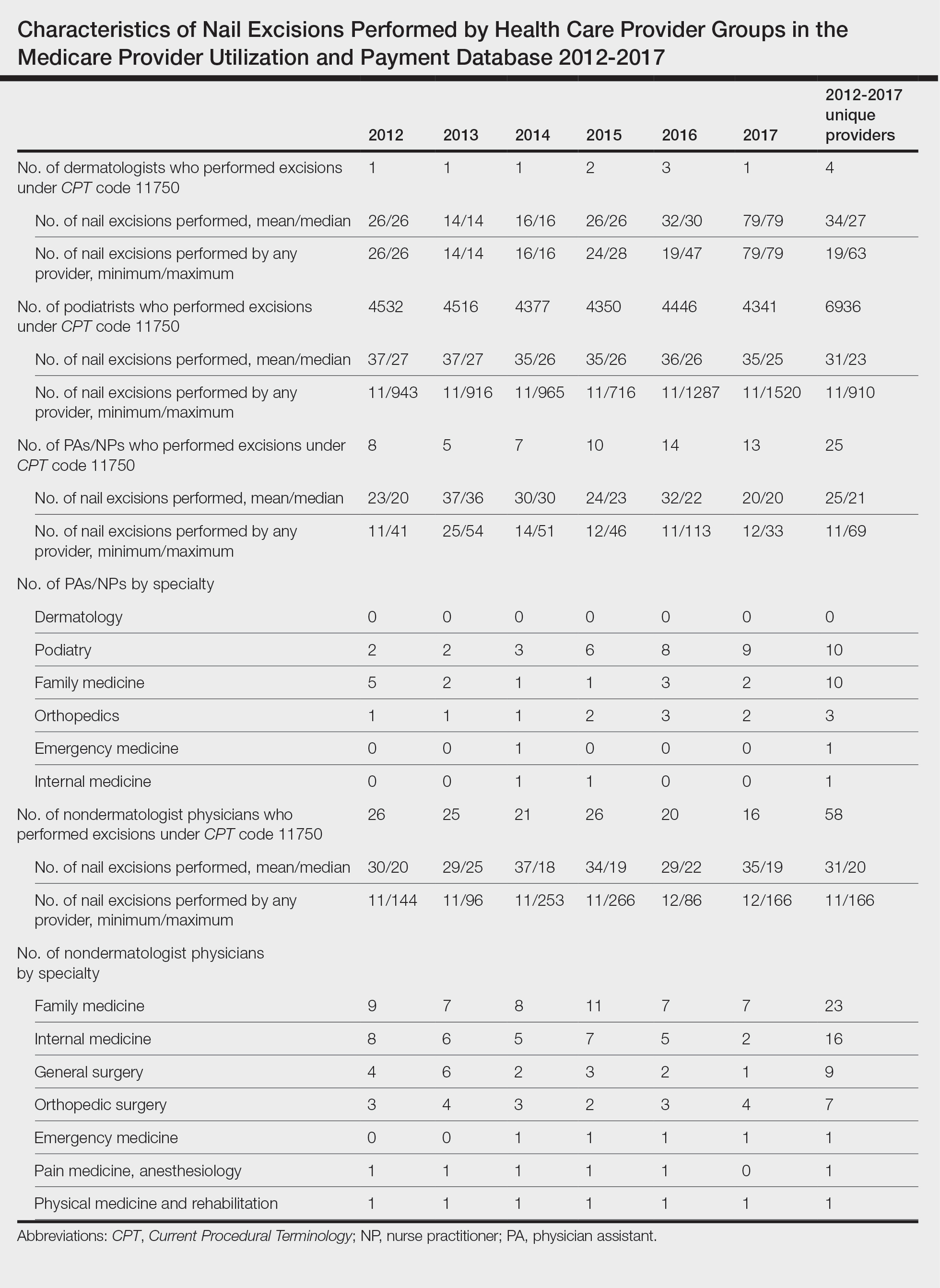

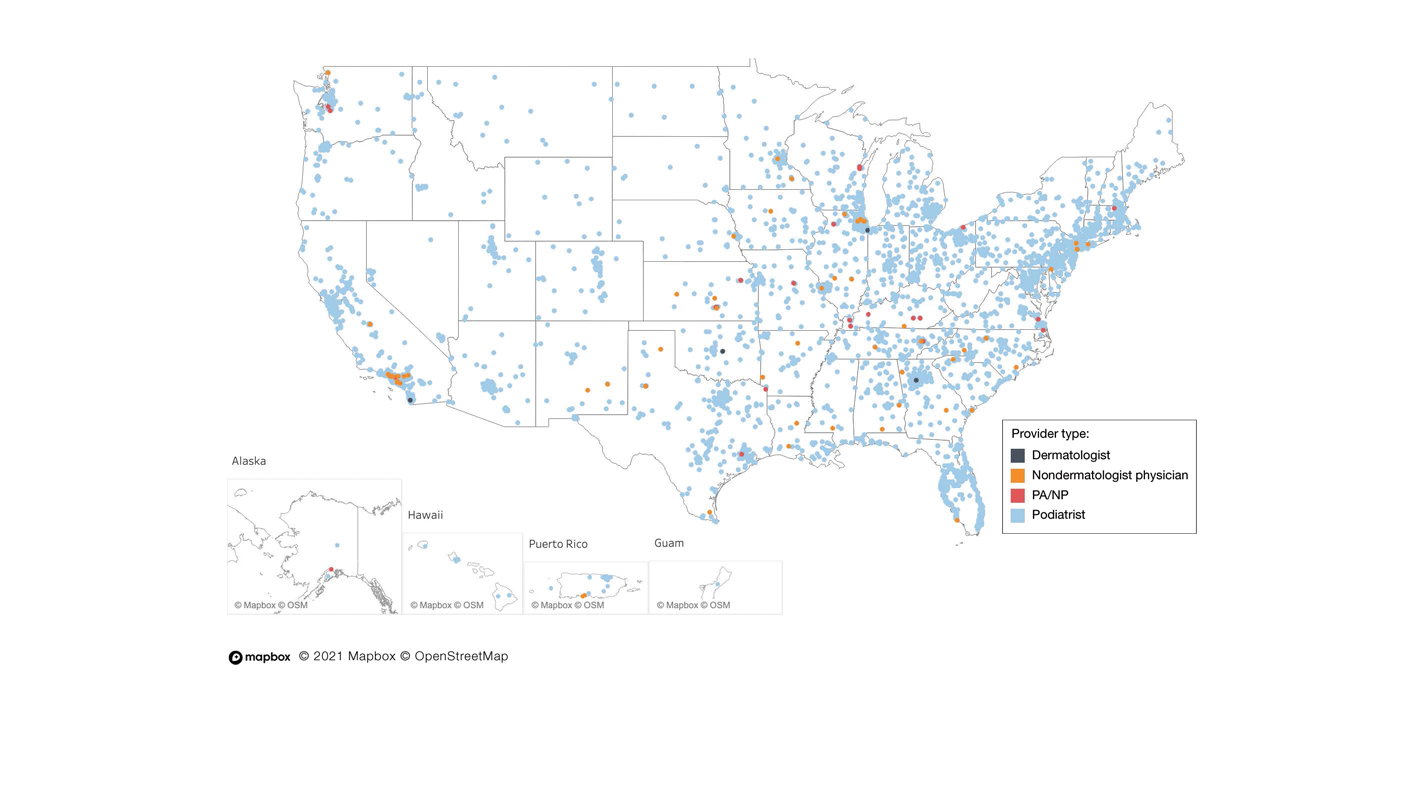

A retrospective analysis on nail excisions using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 11750 (excision of nail and nail matrix, partial or complete [eg, ingrown or deformed nail] for permanent removal), which is distinct from code 11755 (biopsy of nail unit [eg, plate, bed, matrix, hyponychium, proximal and lateral nail folds][separate procedure]), was performed using data from the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012-2017.1,2 This file also is used by Peck et al3 in an article submitted to the Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association and currently under consideration for publication. Procedures were recorded by year and provider type—dermatologist, podiatrist, physician assistant (PA)/nurse practitioner (NP), nondermatologist physician—and subcategorized by provider specialty (Table). Practice locations subcategorized by provider type were mapped using Tableau Software (Salesforce)(Figure). Descriptive statistics including number of providers, mean and median excisions per provider, and minimum/maximum nail excisions were calculated (Table). Practice types of PAs/NPs and specialization of nondermatologist physicians were determined using provider name, identification number, and practice address. This study did not require institutional review board review, as only publicly available data were utilized in our analysis.

A total of 6936 podiatrists, 58 nondermatologist physicians, 25 PAs/NPs, and 4 dermatologists performed 10 or more nail excisions annually under CPT code 11750 from January 2012 to December 2017 with annual means of 31, 31, 25, and 34, respectively (Table). No PAs/NPs included in the dataset worked in dermatology practices during the study period. Physician assistants and NPs most often practiced in podiatry and family medicine (FM) settings (both 40% [10/25]). Nondermatologist physicians most often specialized in FM (40% [23/58])(Table). The greatest number of providers practiced in 3 of the 4 most-populous states: California, Texas, and Florida; the fewest number practiced in 3 of the 10 least-populous states: Alaska, Hawaii, and Vermont. Vermont, Wyoming, and North Dakota—3 of the 5 least-populous states—had the fewest practitioners among the contiguous United States (Figure).

Our study showed that from January 2012 to December 2017, fewer dermatologists performed nail excisions than any other provider type (0.06%, 4 dermatologists of 7023 total providers), and dermatologists performed 1734-fold fewer nail excisions than podiatrists (99%, 6936 podiatrists of 7023 total providers). Only dermatologists practicing in California, Georgia, Indiana, and Oklahoma performed nail excisions. Conversely, podiatrists were more geographically distributed across the United States and other territories, with representation in all 50 states as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Reasons for these large discrepancies in practice between dermatologists and other providers likely are multifactorial, encompassing a lack of emphasis on nail procedures in dermatology training, patient perception of the scope of dermatologic practice, and nail excision reimbursement patterns. Most dermatologists likely lack experience in performing nail procedures. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements mandate that dermatology residents observe or perform 3 nail procedures over 3 years of residency, including 1 that may be performed on a human cadaver.4 In contrast, podiatry trainees must gain competency in toenail avulsion (both partial and complete), participate in anesthesia workshops, and become proficient in administering lower extremity blocks by the end of their training.5 Therefore, incorporating aspects of podiatric surgical training into dermatology residency requirements may increase the competency and comfort of dermatologists in performing nail excisions and practicing as nail experts as attending physicians.

It is likely that US patients do not perceive dermatologists as nail specialists and instead primarily consult podiatrists or FM and/or internal medicine physicians for treatment; for example, nail disease was one of the least common reasons for consulting a dermatologist (5%) in a German nationwide survey-based study (N=1015).6 Therefore, increased efforts are needed to educate the general public about the expertise of dermatologists in the diagnosis and management of nail conditions.

Reimbursement also may be a barrier to dermatologists performing nail procedures as part of their scope of practice; for example, in a retrospective study of nail biopsies using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database, there was no statistically significant difference in reimbursements for nail biopsies vs skin biopsies from 2012 to 2017 (P=0.69).7 Similar to nail biopsies, nail excisions typically are much more time consuming and technically demanding than skin biopsies, which may discourage dermatologists from routinely performing nail excision procedures.

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. The data reflected only US-based practice patterns and may not be applicable to nail procedures globally. There also is the potential for miscoding of procedures in the Medicare database. The data included only Part B Medicare fee-for-service and excludes non-Medicare insured, uninsured, and self-pay patients, as well as aggregated records from 10 or fewer Medicare beneficiaries.

Dermatologists rarely perform nail excisions and perform fewer nail excisions than any other provider type in the United States. There currently is an unmet need for comprehensive nail surgery education in US-based dermatology residency programs. We hope that our study fosters interdisciplinary collegiality and training between podiatrists and dermatologists and promotes expanded access to care across the United States to serve patients with nail disorders.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-For-Service Provider Utilization & Payment Data Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File: A Methodological Overview . Updated September 22, 2020. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-charge-data/downloads/medicare-physician-and-other-supplier-puf-methodology.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Billing and Coding: Surgical Treatment of Nails. Updated November 9, 2023. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/article.aspx?articleID=52998#:~:text=The%20description%20of%20CPT%20codes,date%20of%20service%20(DOS).

- Peck GM, Vlahovic TC, Hill R, et al. Senior podiatrists in solo practice are high performers of nail excisions. JAPMA. In press.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Case log minimums. review committee for dermatology. Published May 2019. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/CaseLogMinimums.pdf?ver=2018-04-03-102751-650

- Council on Podiatric Medical Education. Standards and Requirements for Approval of Podiatric Medicine and Surgery Residencies. Published July 2023. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://www.cpme.org/files/320%20Council%20Approved%20October%202022%20-%20April%202023%20edits.pdf

- Augustin M, Eissing L, Elsner P, et al. Perception and image of dermatology in the German general population 2002-2014. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:2124-2130.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare provider utilization and payment database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14928.

To the Editor:

Partial or total nail plate excisions commonly are used for the treatment of onychocryptosis and nail spicules. Procedures involving the nail unit require advanced technical skills to achieve optimal functional and aesthetic outcomes, avoid complications, and minimize health care costs. Data on the frequency of nail plate excisions performed by dermatologists and their relative frequency compared to other medical providers are limited. The objective of our study was to analyze trends in nail excision practice patterns among medical providers in the United States.

A retrospective analysis on nail excisions using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 11750 (excision of nail and nail matrix, partial or complete [eg, ingrown or deformed nail] for permanent removal), which is distinct from code 11755 (biopsy of nail unit [eg, plate, bed, matrix, hyponychium, proximal and lateral nail folds][separate procedure]), was performed using data from the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012-2017.1,2 This file also is used by Peck et al3 in an article submitted to the Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association and currently under consideration for publication. Procedures were recorded by year and provider type—dermatologist, podiatrist, physician assistant (PA)/nurse practitioner (NP), nondermatologist physician—and subcategorized by provider specialty (Table). Practice locations subcategorized by provider type were mapped using Tableau Software (Salesforce)(Figure). Descriptive statistics including number of providers, mean and median excisions per provider, and minimum/maximum nail excisions were calculated (Table). Practice types of PAs/NPs and specialization of nondermatologist physicians were determined using provider name, identification number, and practice address. This study did not require institutional review board review, as only publicly available data were utilized in our analysis.

A total of 6936 podiatrists, 58 nondermatologist physicians, 25 PAs/NPs, and 4 dermatologists performed 10 or more nail excisions annually under CPT code 11750 from January 2012 to December 2017 with annual means of 31, 31, 25, and 34, respectively (Table). No PAs/NPs included in the dataset worked in dermatology practices during the study period. Physician assistants and NPs most often practiced in podiatry and family medicine (FM) settings (both 40% [10/25]). Nondermatologist physicians most often specialized in FM (40% [23/58])(Table). The greatest number of providers practiced in 3 of the 4 most-populous states: California, Texas, and Florida; the fewest number practiced in 3 of the 10 least-populous states: Alaska, Hawaii, and Vermont. Vermont, Wyoming, and North Dakota—3 of the 5 least-populous states—had the fewest practitioners among the contiguous United States (Figure).

Our study showed that from January 2012 to December 2017, fewer dermatologists performed nail excisions than any other provider type (0.06%, 4 dermatologists of 7023 total providers), and dermatologists performed 1734-fold fewer nail excisions than podiatrists (99%, 6936 podiatrists of 7023 total providers). Only dermatologists practicing in California, Georgia, Indiana, and Oklahoma performed nail excisions. Conversely, podiatrists were more geographically distributed across the United States and other territories, with representation in all 50 states as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Reasons for these large discrepancies in practice between dermatologists and other providers likely are multifactorial, encompassing a lack of emphasis on nail procedures in dermatology training, patient perception of the scope of dermatologic practice, and nail excision reimbursement patterns. Most dermatologists likely lack experience in performing nail procedures. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements mandate that dermatology residents observe or perform 3 nail procedures over 3 years of residency, including 1 that may be performed on a human cadaver.4 In contrast, podiatry trainees must gain competency in toenail avulsion (both partial and complete), participate in anesthesia workshops, and become proficient in administering lower extremity blocks by the end of their training.5 Therefore, incorporating aspects of podiatric surgical training into dermatology residency requirements may increase the competency and comfort of dermatologists in performing nail excisions and practicing as nail experts as attending physicians.

It is likely that US patients do not perceive dermatologists as nail specialists and instead primarily consult podiatrists or FM and/or internal medicine physicians for treatment; for example, nail disease was one of the least common reasons for consulting a dermatologist (5%) in a German nationwide survey-based study (N=1015).6 Therefore, increased efforts are needed to educate the general public about the expertise of dermatologists in the diagnosis and management of nail conditions.

Reimbursement also may be a barrier to dermatologists performing nail procedures as part of their scope of practice; for example, in a retrospective study of nail biopsies using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database, there was no statistically significant difference in reimbursements for nail biopsies vs skin biopsies from 2012 to 2017 (P=0.69).7 Similar to nail biopsies, nail excisions typically are much more time consuming and technically demanding than skin biopsies, which may discourage dermatologists from routinely performing nail excision procedures.

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. The data reflected only US-based practice patterns and may not be applicable to nail procedures globally. There also is the potential for miscoding of procedures in the Medicare database. The data included only Part B Medicare fee-for-service and excludes non-Medicare insured, uninsured, and self-pay patients, as well as aggregated records from 10 or fewer Medicare beneficiaries.

Dermatologists rarely perform nail excisions and perform fewer nail excisions than any other provider type in the United States. There currently is an unmet need for comprehensive nail surgery education in US-based dermatology residency programs. We hope that our study fosters interdisciplinary collegiality and training between podiatrists and dermatologists and promotes expanded access to care across the United States to serve patients with nail disorders.

To the Editor:

Partial or total nail plate excisions commonly are used for the treatment of onychocryptosis and nail spicules. Procedures involving the nail unit require advanced technical skills to achieve optimal functional and aesthetic outcomes, avoid complications, and minimize health care costs. Data on the frequency of nail plate excisions performed by dermatologists and their relative frequency compared to other medical providers are limited. The objective of our study was to analyze trends in nail excision practice patterns among medical providers in the United States.

A retrospective analysis on nail excisions using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 11750 (excision of nail and nail matrix, partial or complete [eg, ingrown or deformed nail] for permanent removal), which is distinct from code 11755 (biopsy of nail unit [eg, plate, bed, matrix, hyponychium, proximal and lateral nail folds][separate procedure]), was performed using data from the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database 2012-2017.1,2 This file also is used by Peck et al3 in an article submitted to the Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association and currently under consideration for publication. Procedures were recorded by year and provider type—dermatologist, podiatrist, physician assistant (PA)/nurse practitioner (NP), nondermatologist physician—and subcategorized by provider specialty (Table). Practice locations subcategorized by provider type were mapped using Tableau Software (Salesforce)(Figure). Descriptive statistics including number of providers, mean and median excisions per provider, and minimum/maximum nail excisions were calculated (Table). Practice types of PAs/NPs and specialization of nondermatologist physicians were determined using provider name, identification number, and practice address. This study did not require institutional review board review, as only publicly available data were utilized in our analysis.

A total of 6936 podiatrists, 58 nondermatologist physicians, 25 PAs/NPs, and 4 dermatologists performed 10 or more nail excisions annually under CPT code 11750 from January 2012 to December 2017 with annual means of 31, 31, 25, and 34, respectively (Table). No PAs/NPs included in the dataset worked in dermatology practices during the study period. Physician assistants and NPs most often practiced in podiatry and family medicine (FM) settings (both 40% [10/25]). Nondermatologist physicians most often specialized in FM (40% [23/58])(Table). The greatest number of providers practiced in 3 of the 4 most-populous states: California, Texas, and Florida; the fewest number practiced in 3 of the 10 least-populous states: Alaska, Hawaii, and Vermont. Vermont, Wyoming, and North Dakota—3 of the 5 least-populous states—had the fewest practitioners among the contiguous United States (Figure).

Our study showed that from January 2012 to December 2017, fewer dermatologists performed nail excisions than any other provider type (0.06%, 4 dermatologists of 7023 total providers), and dermatologists performed 1734-fold fewer nail excisions than podiatrists (99%, 6936 podiatrists of 7023 total providers). Only dermatologists practicing in California, Georgia, Indiana, and Oklahoma performed nail excisions. Conversely, podiatrists were more geographically distributed across the United States and other territories, with representation in all 50 states as well as the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Reasons for these large discrepancies in practice between dermatologists and other providers likely are multifactorial, encompassing a lack of emphasis on nail procedures in dermatology training, patient perception of the scope of dermatologic practice, and nail excision reimbursement patterns. Most dermatologists likely lack experience in performing nail procedures. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirements mandate that dermatology residents observe or perform 3 nail procedures over 3 years of residency, including 1 that may be performed on a human cadaver.4 In contrast, podiatry trainees must gain competency in toenail avulsion (both partial and complete), participate in anesthesia workshops, and become proficient in administering lower extremity blocks by the end of their training.5 Therefore, incorporating aspects of podiatric surgical training into dermatology residency requirements may increase the competency and comfort of dermatologists in performing nail excisions and practicing as nail experts as attending physicians.

It is likely that US patients do not perceive dermatologists as nail specialists and instead primarily consult podiatrists or FM and/or internal medicine physicians for treatment; for example, nail disease was one of the least common reasons for consulting a dermatologist (5%) in a German nationwide survey-based study (N=1015).6 Therefore, increased efforts are needed to educate the general public about the expertise of dermatologists in the diagnosis and management of nail conditions.

Reimbursement also may be a barrier to dermatologists performing nail procedures as part of their scope of practice; for example, in a retrospective study of nail biopsies using the Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Database, there was no statistically significant difference in reimbursements for nail biopsies vs skin biopsies from 2012 to 2017 (P=0.69).7 Similar to nail biopsies, nail excisions typically are much more time consuming and technically demanding than skin biopsies, which may discourage dermatologists from routinely performing nail excision procedures.

Our study is subject to a number of limitations. The data reflected only US-based practice patterns and may not be applicable to nail procedures globally. There also is the potential for miscoding of procedures in the Medicare database. The data included only Part B Medicare fee-for-service and excludes non-Medicare insured, uninsured, and self-pay patients, as well as aggregated records from 10 or fewer Medicare beneficiaries.

Dermatologists rarely perform nail excisions and perform fewer nail excisions than any other provider type in the United States. There currently is an unmet need for comprehensive nail surgery education in US-based dermatology residency programs. We hope that our study fosters interdisciplinary collegiality and training between podiatrists and dermatologists and promotes expanded access to care across the United States to serve patients with nail disorders.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-For-Service Provider Utilization & Payment Data Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File: A Methodological Overview . Updated September 22, 2020. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-charge-data/downloads/medicare-physician-and-other-supplier-puf-methodology.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Billing and Coding: Surgical Treatment of Nails. Updated November 9, 2023. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/article.aspx?articleID=52998#:~:text=The%20description%20of%20CPT%20codes,date%20of%20service%20(DOS).

- Peck GM, Vlahovic TC, Hill R, et al. Senior podiatrists in solo practice are high performers of nail excisions. JAPMA. In press.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Case log minimums. review committee for dermatology. Published May 2019. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/CaseLogMinimums.pdf?ver=2018-04-03-102751-650

- Council on Podiatric Medical Education. Standards and Requirements for Approval of Podiatric Medicine and Surgery Residencies. Published July 2023. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://www.cpme.org/files/320%20Council%20Approved%20October%202022%20-%20April%202023%20edits.pdf

- Augustin M, Eissing L, Elsner P, et al. Perception and image of dermatology in the German general population 2002-2014. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:2124-2130.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare provider utilization and payment database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14928.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-For-Service Provider Utilization & Payment Data Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File: A Methodological Overview . Updated September 22, 2020. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/medicare-provider-charge-data/downloads/medicare-physician-and-other-supplier-puf-methodology.pdf

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Billing and Coding: Surgical Treatment of Nails. Updated November 9, 2023. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/article.aspx?articleID=52998#:~:text=The%20description%20of%20CPT%20codes,date%20of%20service%20(DOS).

- Peck GM, Vlahovic TC, Hill R, et al. Senior podiatrists in solo practice are high performers of nail excisions. JAPMA. In press.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Case log minimums. review committee for dermatology. Published May 2019. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/CaseLogMinimums.pdf?ver=2018-04-03-102751-650

- Council on Podiatric Medical Education. Standards and Requirements for Approval of Podiatric Medicine and Surgery Residencies. Published July 2023. Accessed January 17, 2024. https://www.cpme.org/files/320%20Council%20Approved%20October%202022%20-%20April%202023%20edits.pdf

- Augustin M, Eissing L, Elsner P, et al. Perception and image of dermatology in the German general population 2002-2014. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:2124-2130.

- Wang Y, Lipner SR. Retrospective analysis of nail biopsies performed using the Medicare provider utilization and payment database 2012 to 2017. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14928.

Practice Points

- Dermatologists are considered nail experts but perform nail excisions less frequently than their podiatric counterparts and physicians in other specialties.

- Aspects of podiatric surgical training should be incorporated into dermatology residency to increase competency and comfort of dermatologists in nail excision procedures.

- Dermatologists may not be perceived as nail experts by the public, indicating a need for increased community education on the role of dermatologists in treating nail disease.