User login

Studying in Dermatology Residency

Dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose, in which one is bombarded with so much information that it is impossible to retain any content. This article provides an overview of available resources and a guide on how to tailor studying throughout one’s training.

Prior to Residency

There are several resources that provide an introduction to dermatology and are appropriate for all medical students, regardless of intended specialty. The American Academy of Dermatology offers a free basic dermatology curriculum (https://www.aad.org/member/education/residents/bdc), with a choice of a 2- or 4-week course consisting of modules such as skin examination, basic science of the skin, dermatologic therapies, and specific dermatologic conditions. VisualDx offers LearnDerm (https://www.visualdx.com/learnderm/), which includes a 5-part tutorial and quiz focused on the skin examination, morphology, and lesion distribution. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology1 is a book at an appropriate level for a medical student to learn about the fundamentals of dermatology. These resources may be helpful for residents to review immediately before starting dermatology residency (toward the end of intern year for most).

First Year

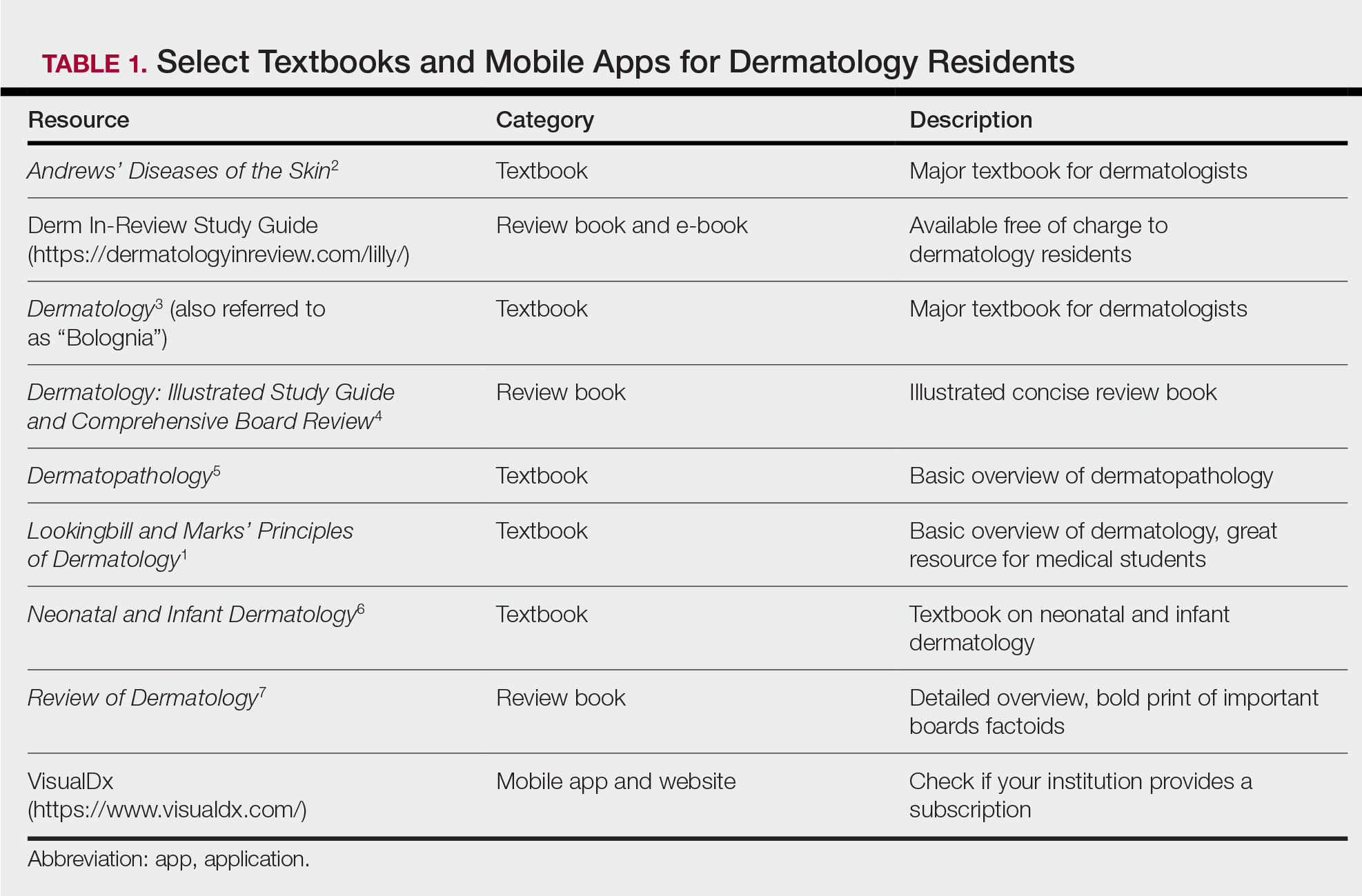

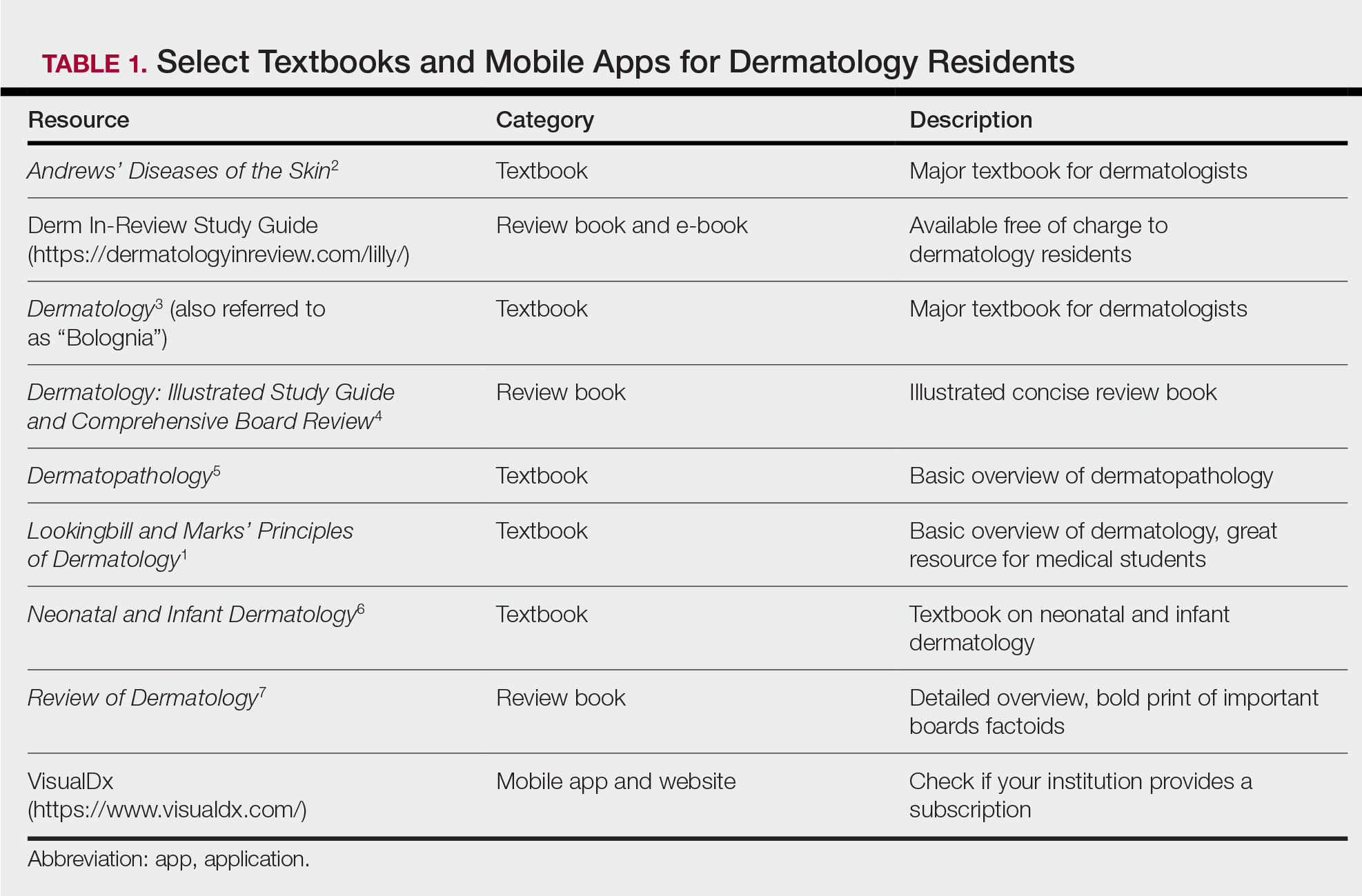

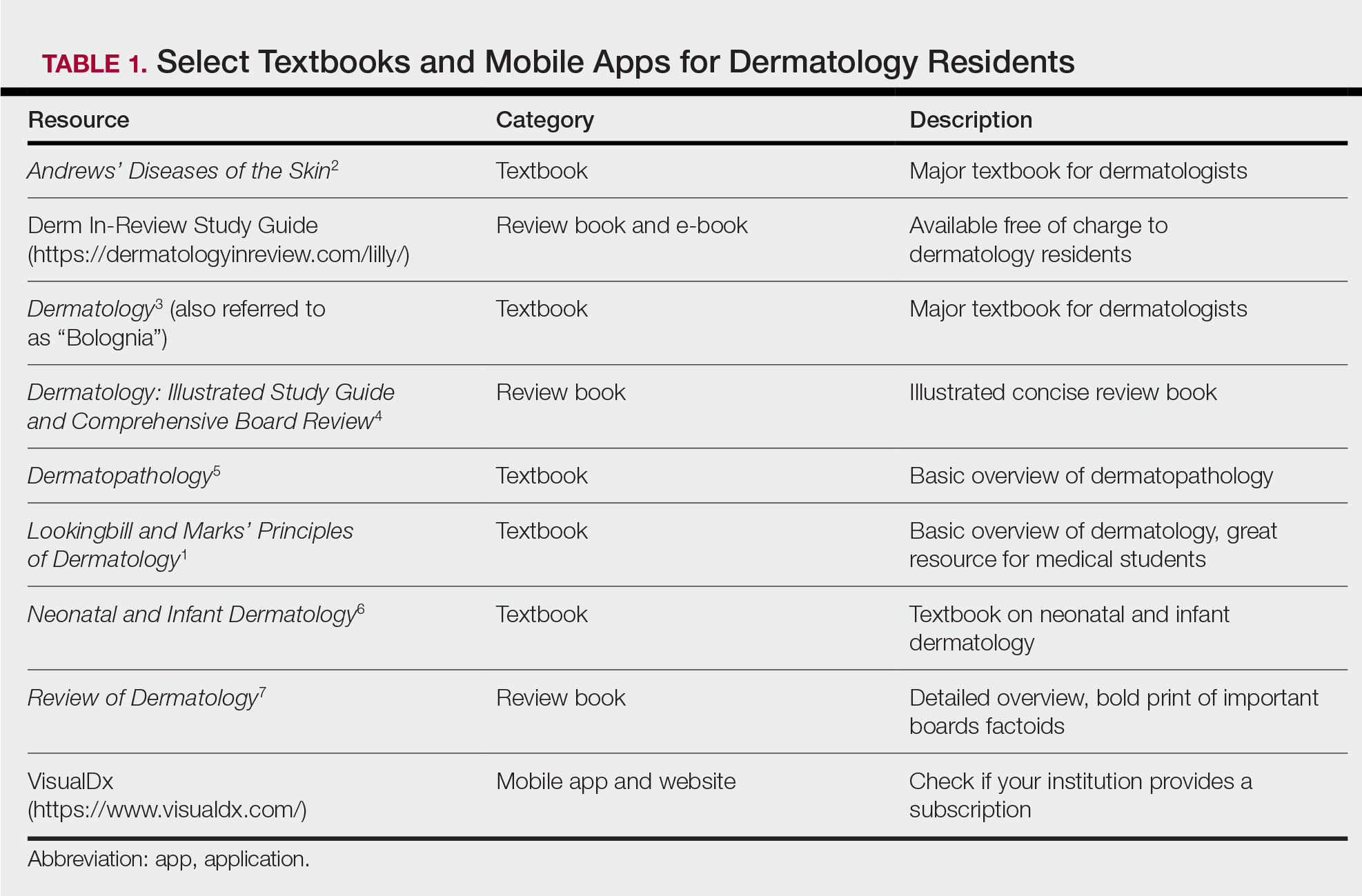

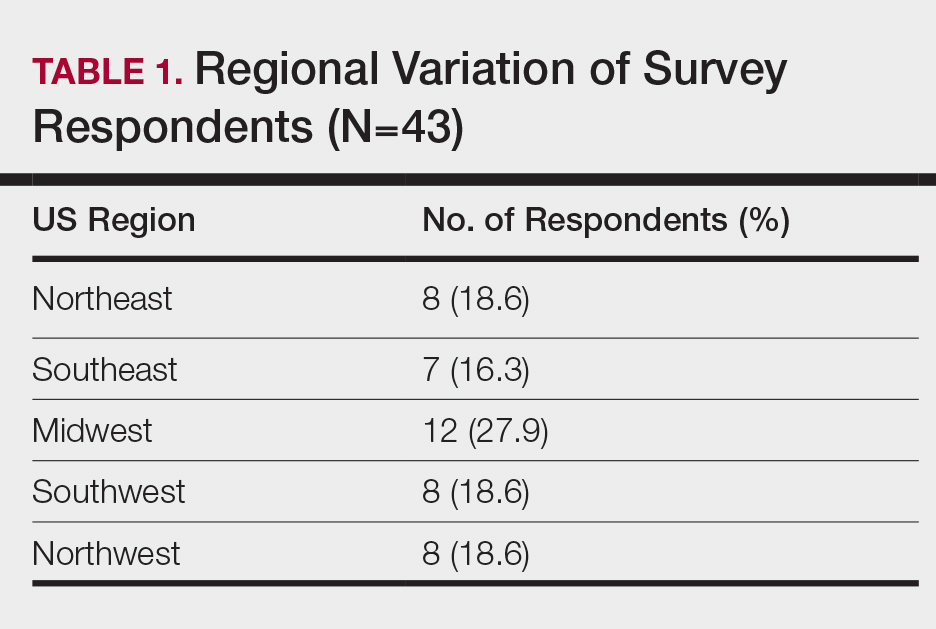

During the beginning of dermatology residency (postgraduate year [PGY] 2 for most), the fire hose of information feels most daunting. During this time, studying should focus on engendering a broad overview of dermatology. Most residencies maintain a textbook reading schedule, which provides a framework from which residents may structure their studying. Selection of a textbook tends to be program dependent. Even if the details of reading the textbook do not stick when reading it the first time, benefits include becoming familiar with what information one is expected to learn as a dermatologist and developing a strong foundation upon which one may continue to build. Based on my informal discussions with current residents, some reported that reading the textbook did not work well for them, citing too much minutiae in the textbooks and/or a preference for a more active learning approach. These residents instead focused on reading a review book for a broad overview, accompanied by a textbook or VisualDx when a more detailed reference is necessary. Table 1 provides a list of textbooks and mobile applications (apps) that residents may find helpful.

First-year residents may begin their efforts in synthesizing this new knowledge base toward the end of the year in preparation for the BASIC examination. The American Board of Dermatology provides a content outline as well as sample questions on their website (https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/exam-of-the-future-information-center.aspx#content), which may be used to guide more focused studying efforts during the weeks leading up to the examination.

Second Year

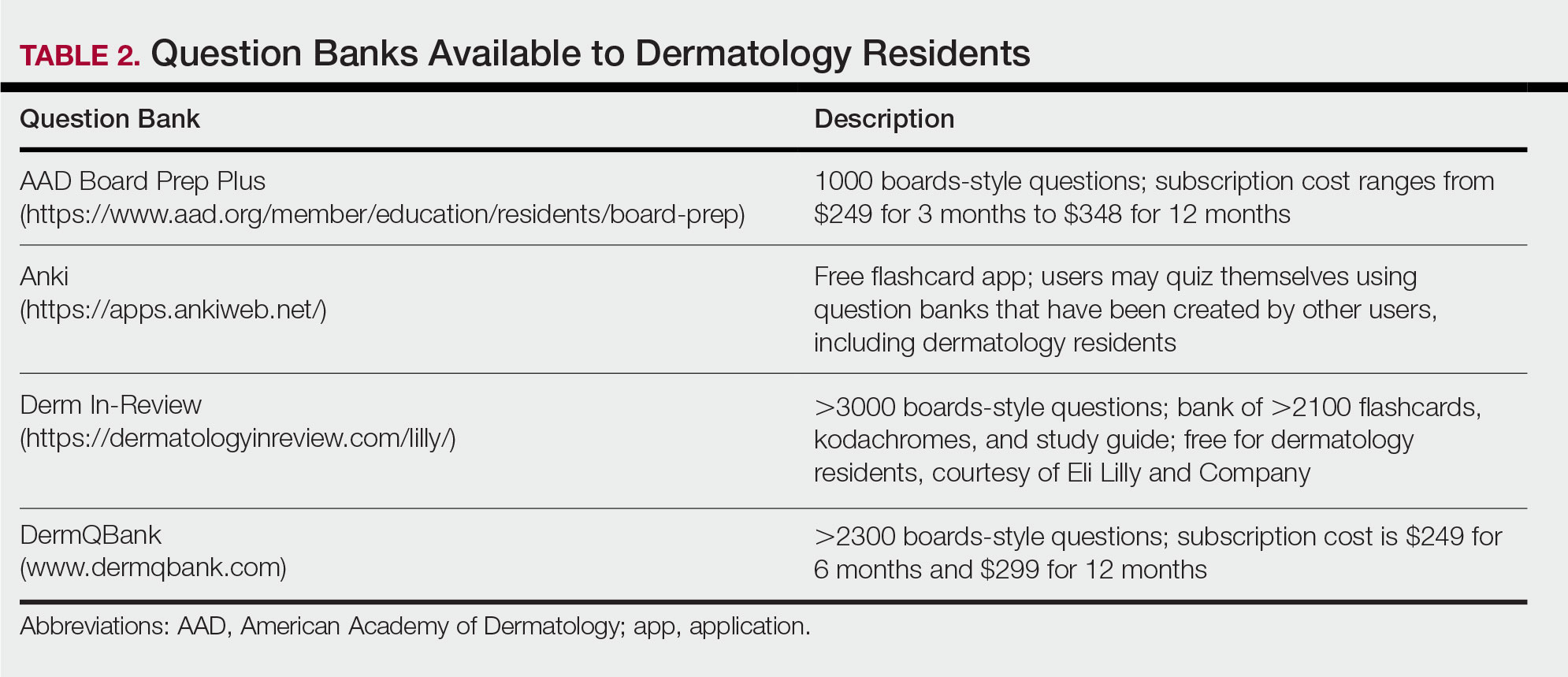

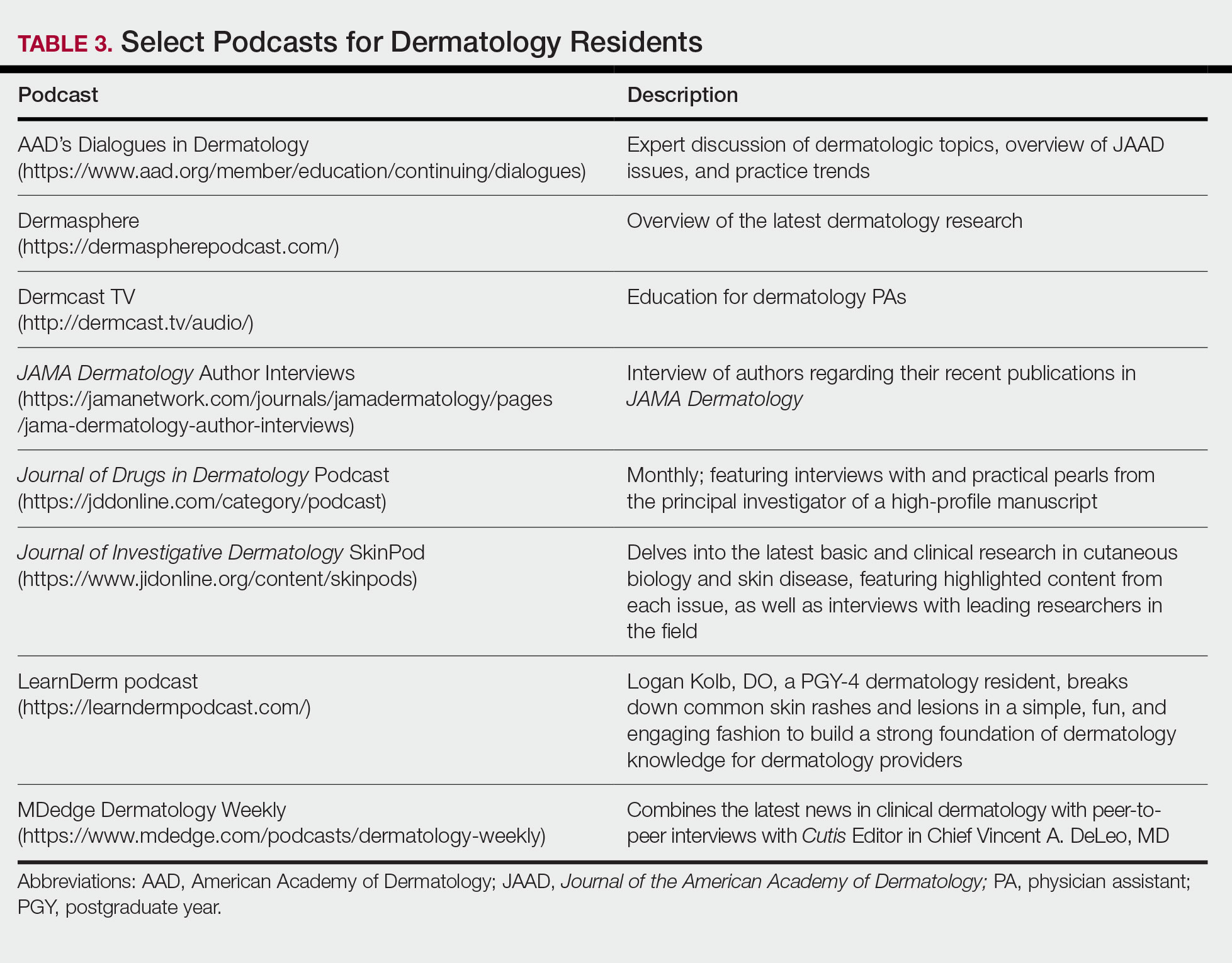

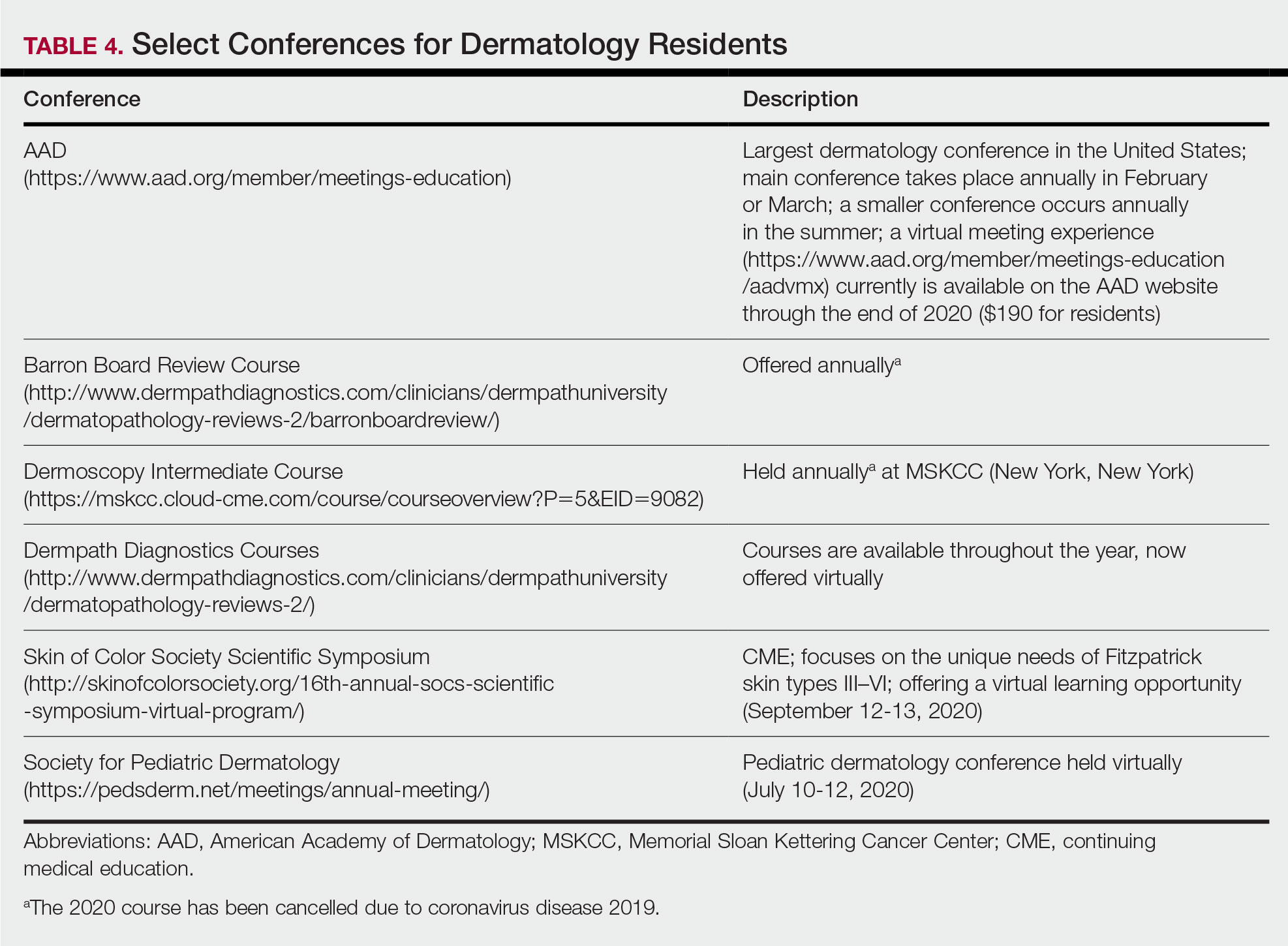

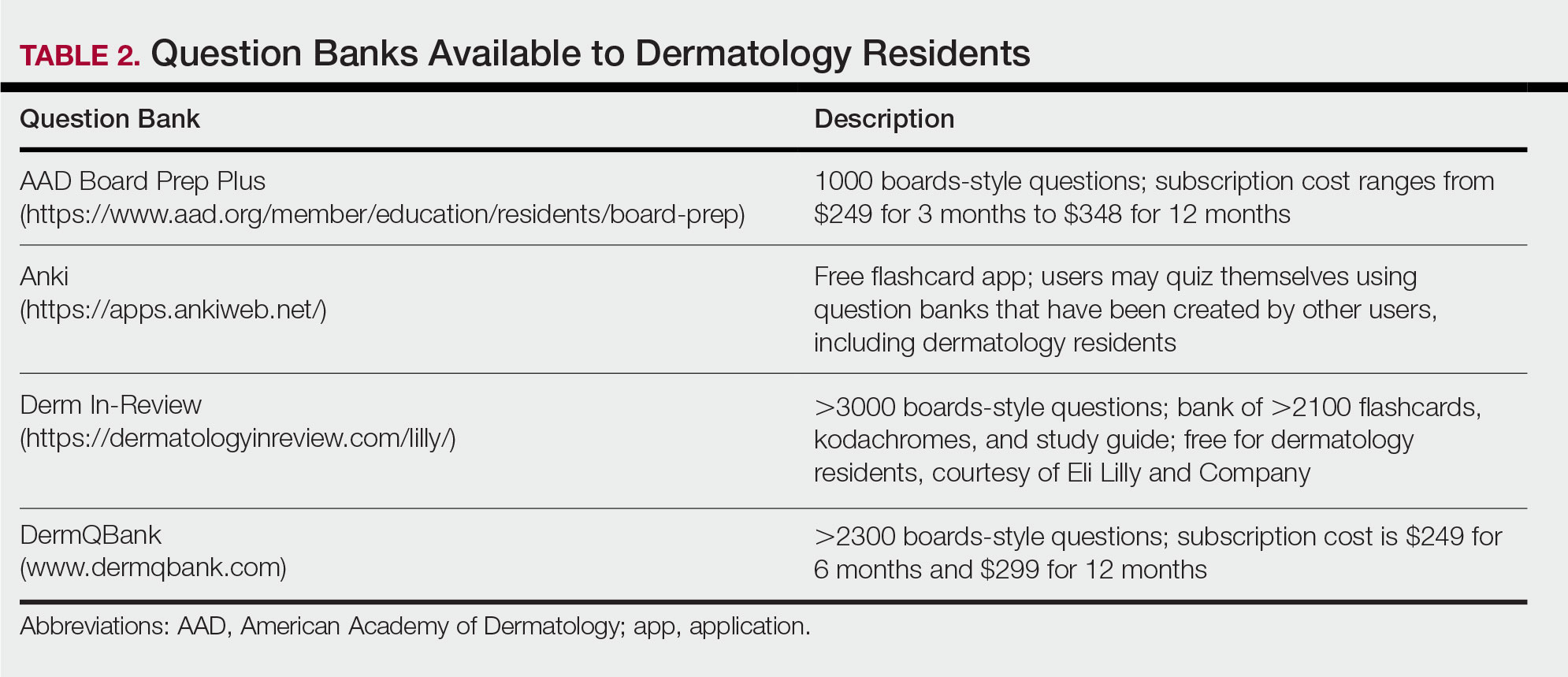

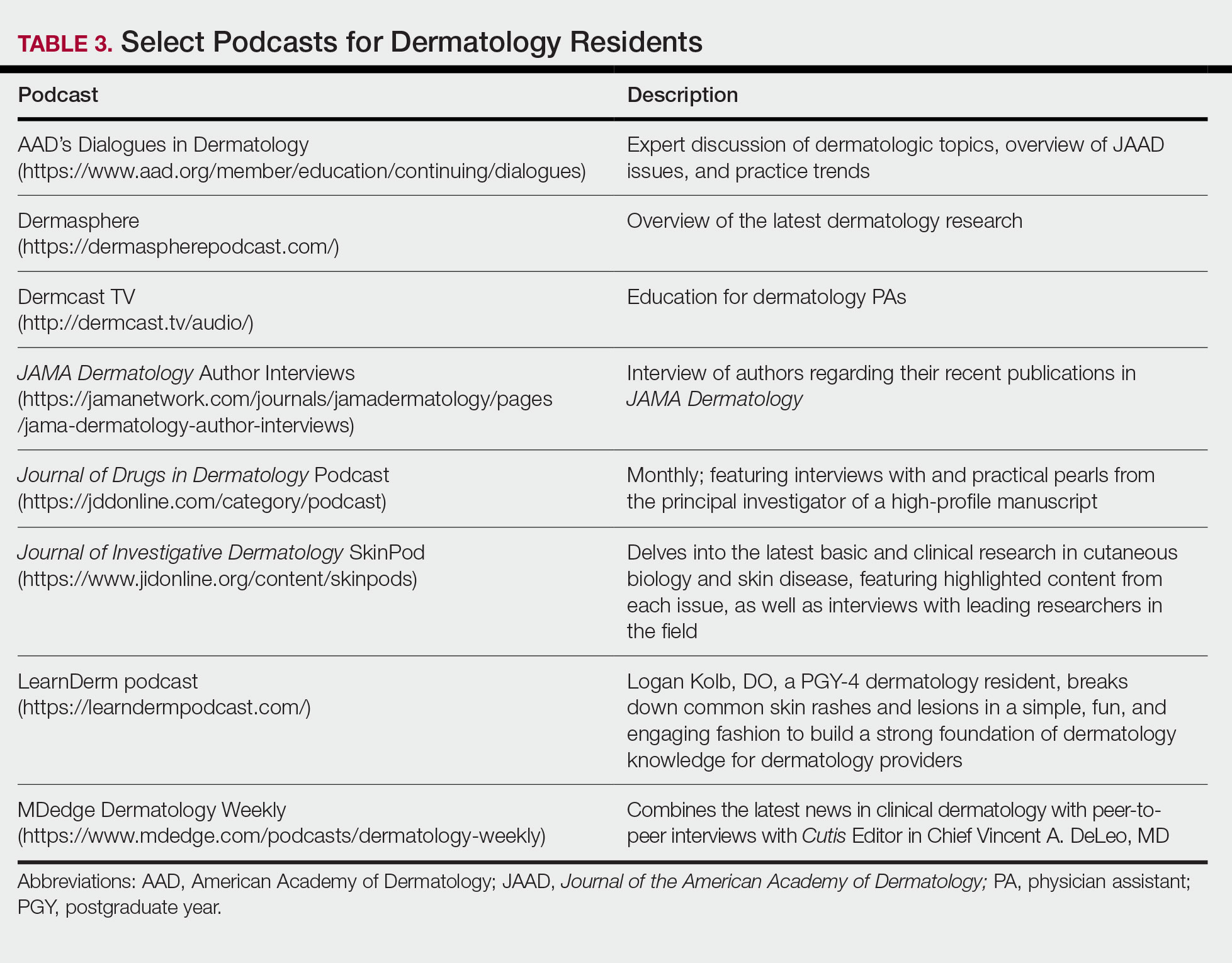

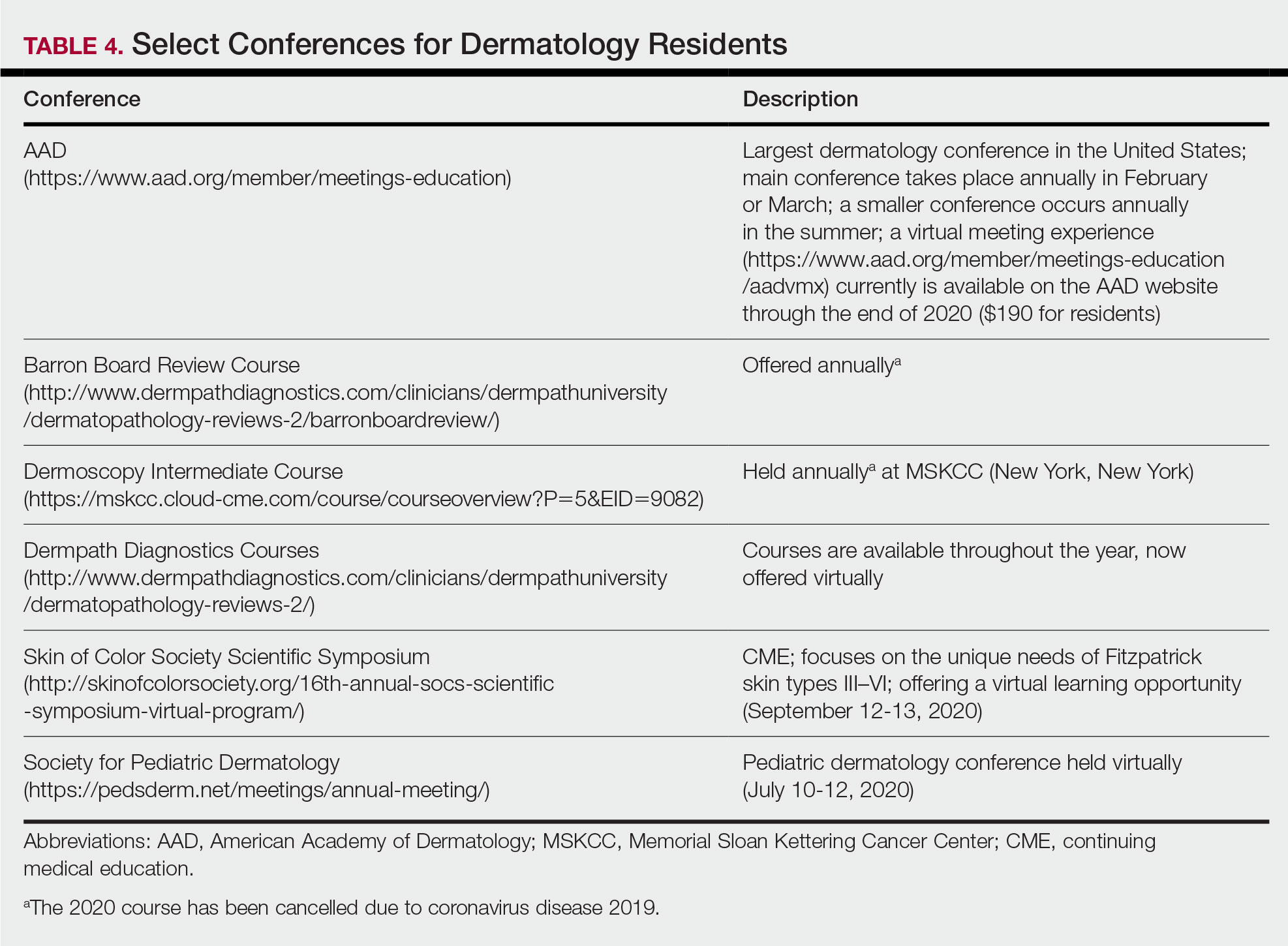

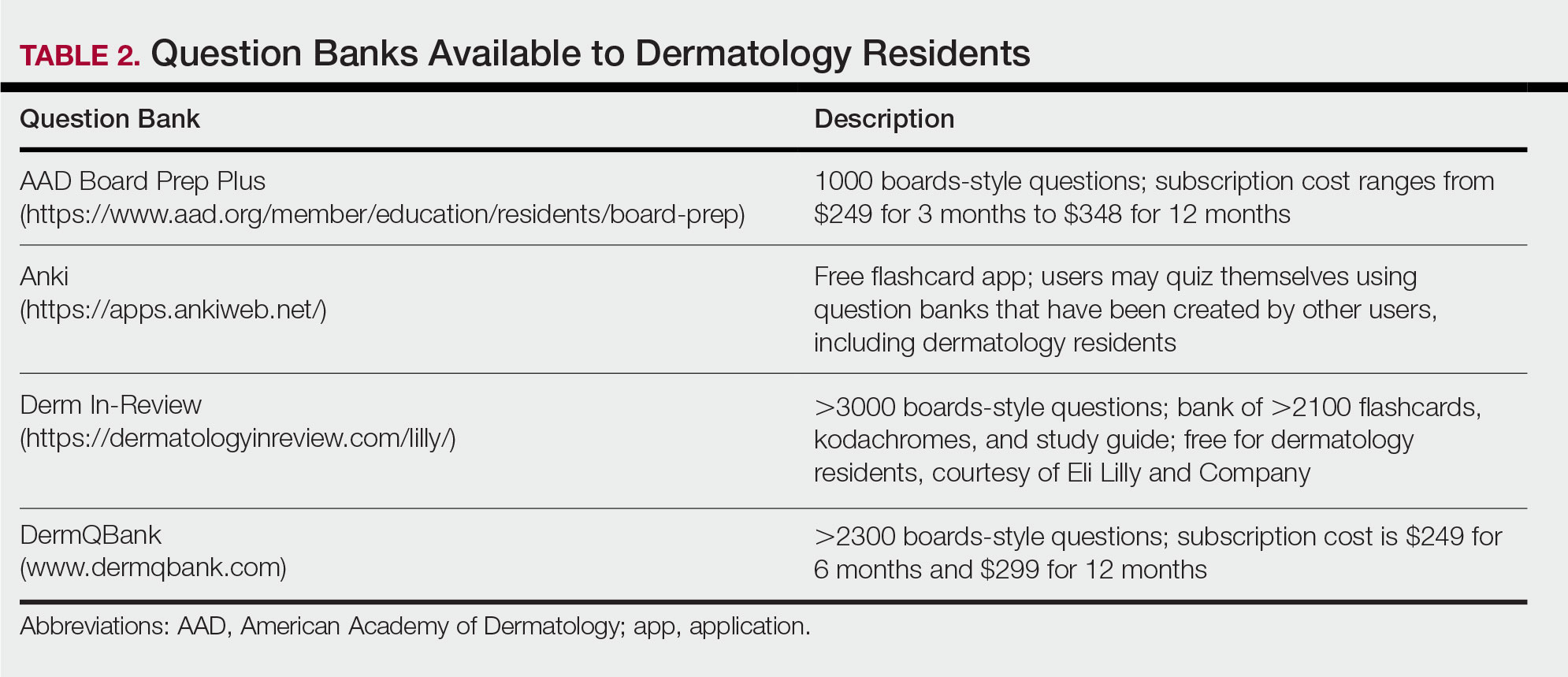

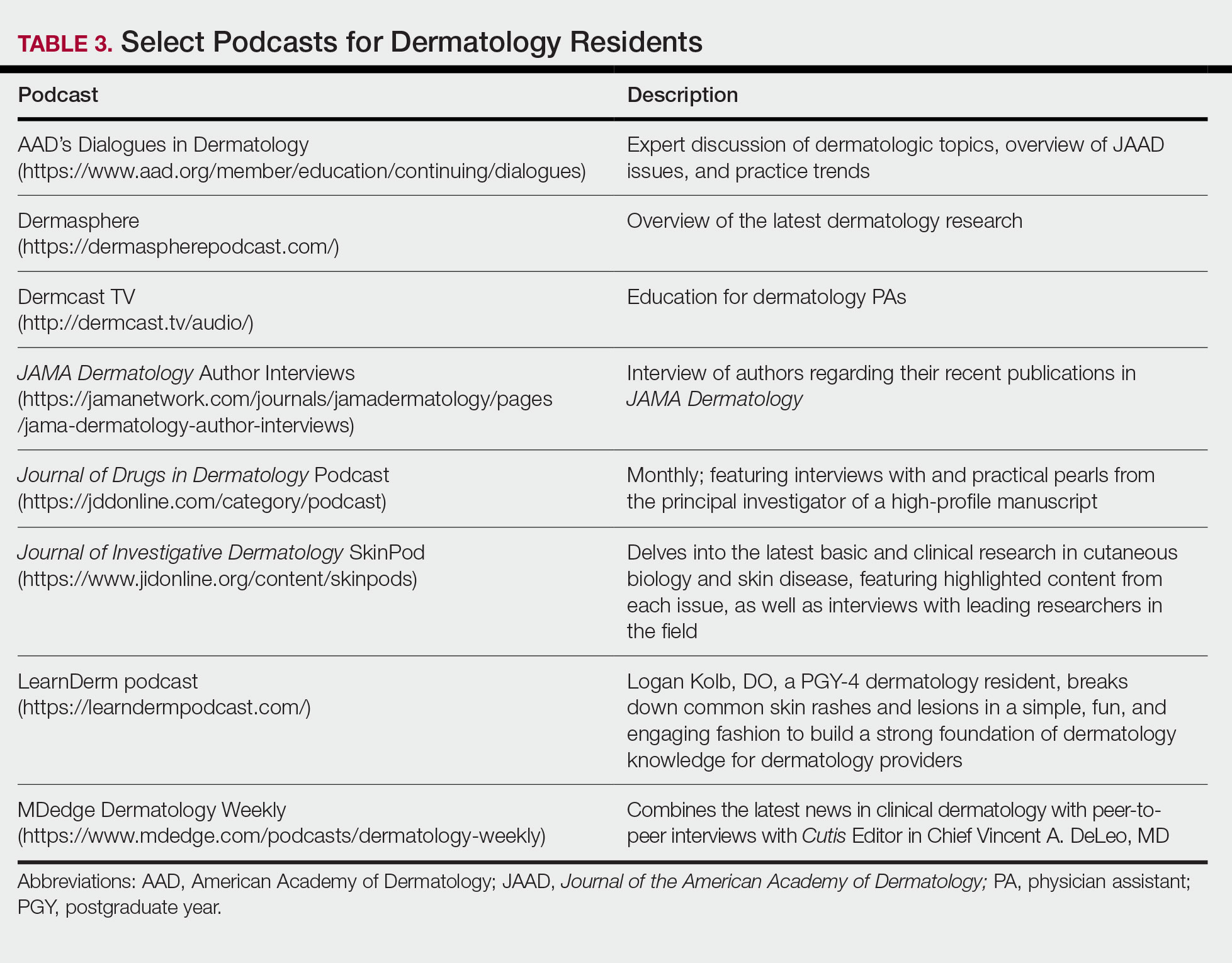

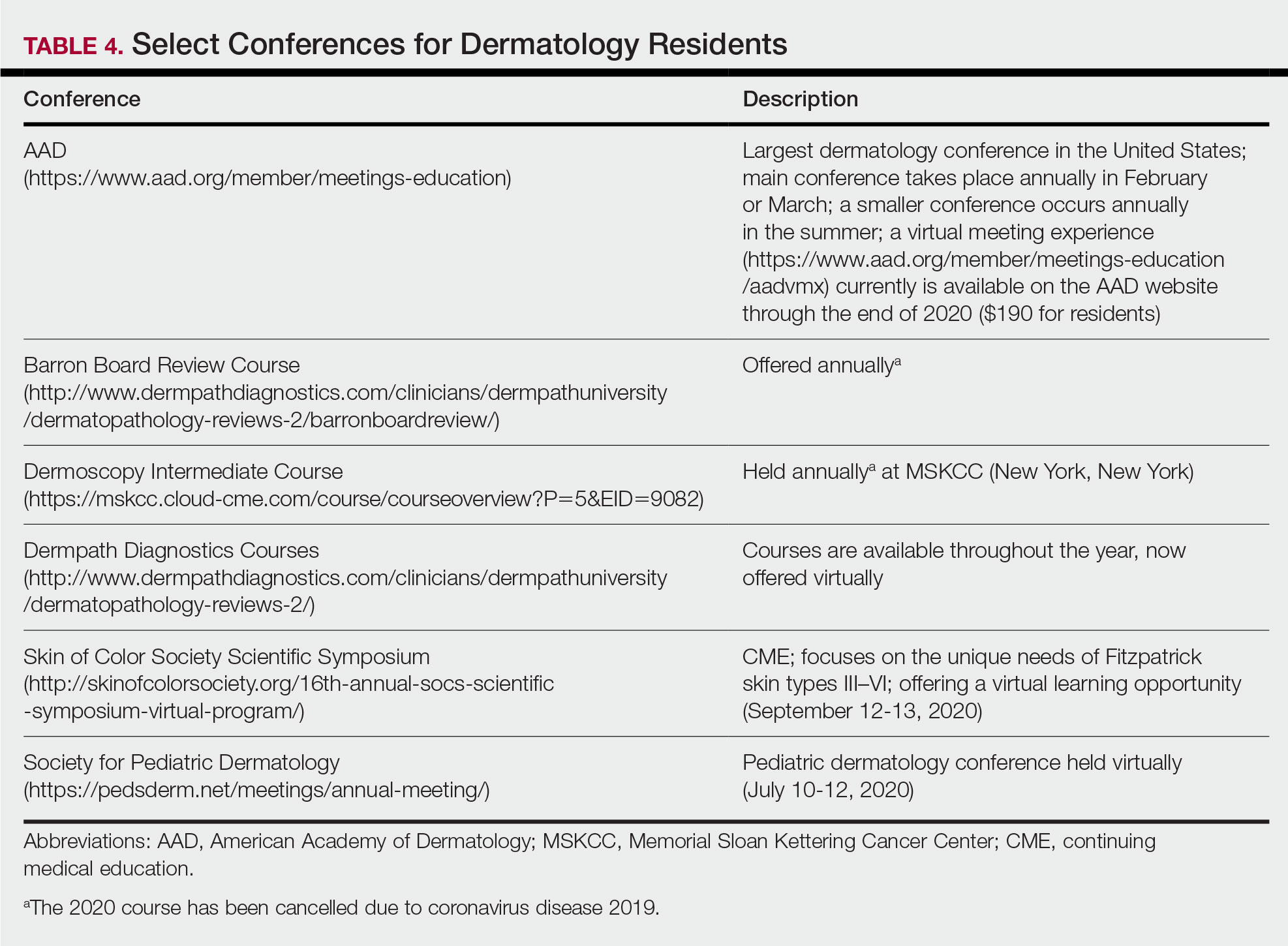

For second-year residents (PGY-3 for most) studying should focus on deepening and consolidating the broad foundation that was established during their first year. For many, this pursuit involves rereading the textbook chapters alongside more active learning measures, such as taking notes and quizzing oneself using flashcard apps and question banks (Table 2). Others may benefit from listening to podcasts (Table 3) or other sources utilizing audiovisual content, including attending conferences and other lectures virtually, which is becoming increasingly available in the setting of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (Table 4). Because there are so many resources available to support these efforts, residents should be encouraged to try out a variety to determine what works best.

Toward the end of second year, studying may be tailored to preparing for the CORE examinations using the resources of one’s choice. Based on my discussions with current residents, a combination of reading review books, reviewing one’s personal notes, and quizzing through question banks and/or flashcard apps could be used.

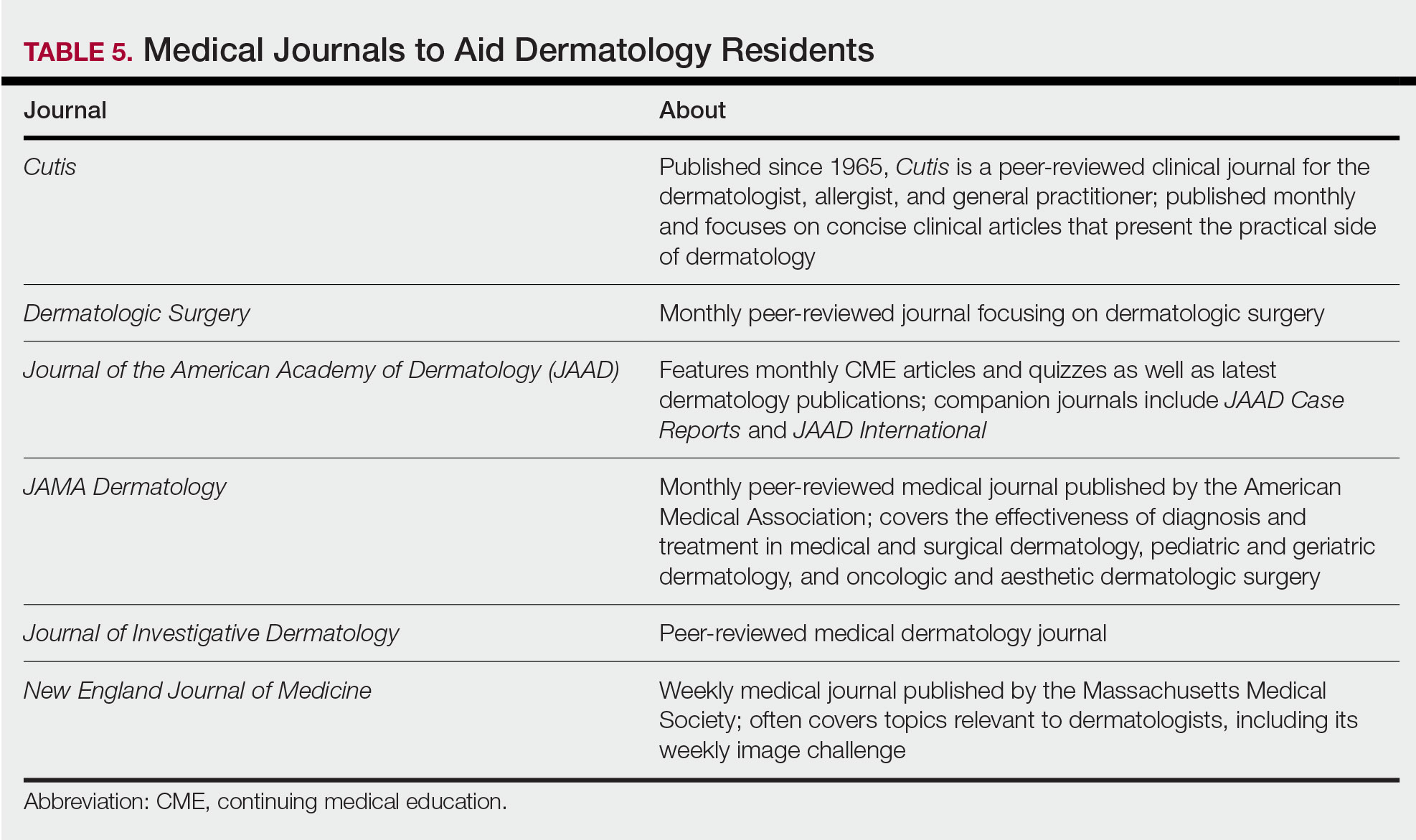

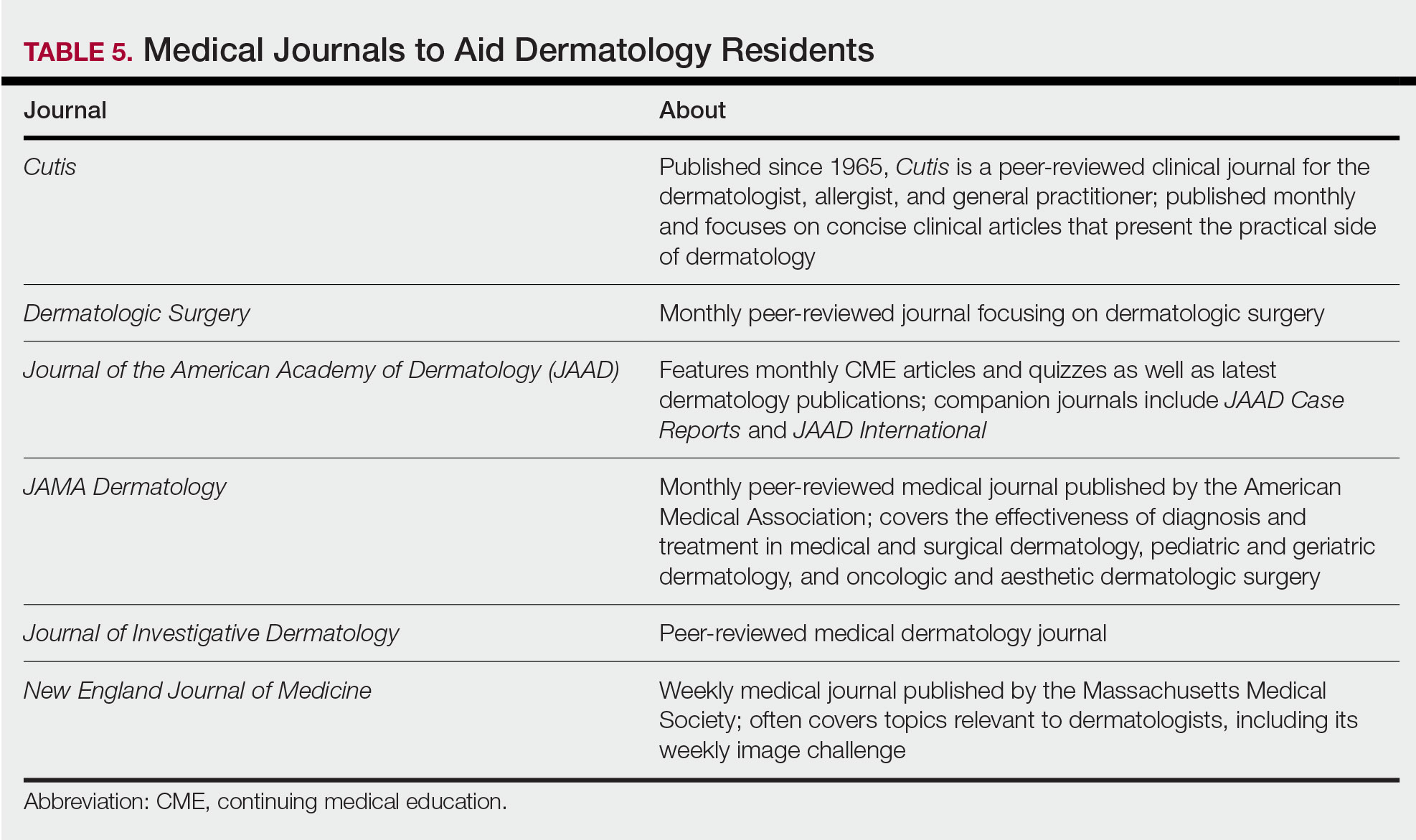

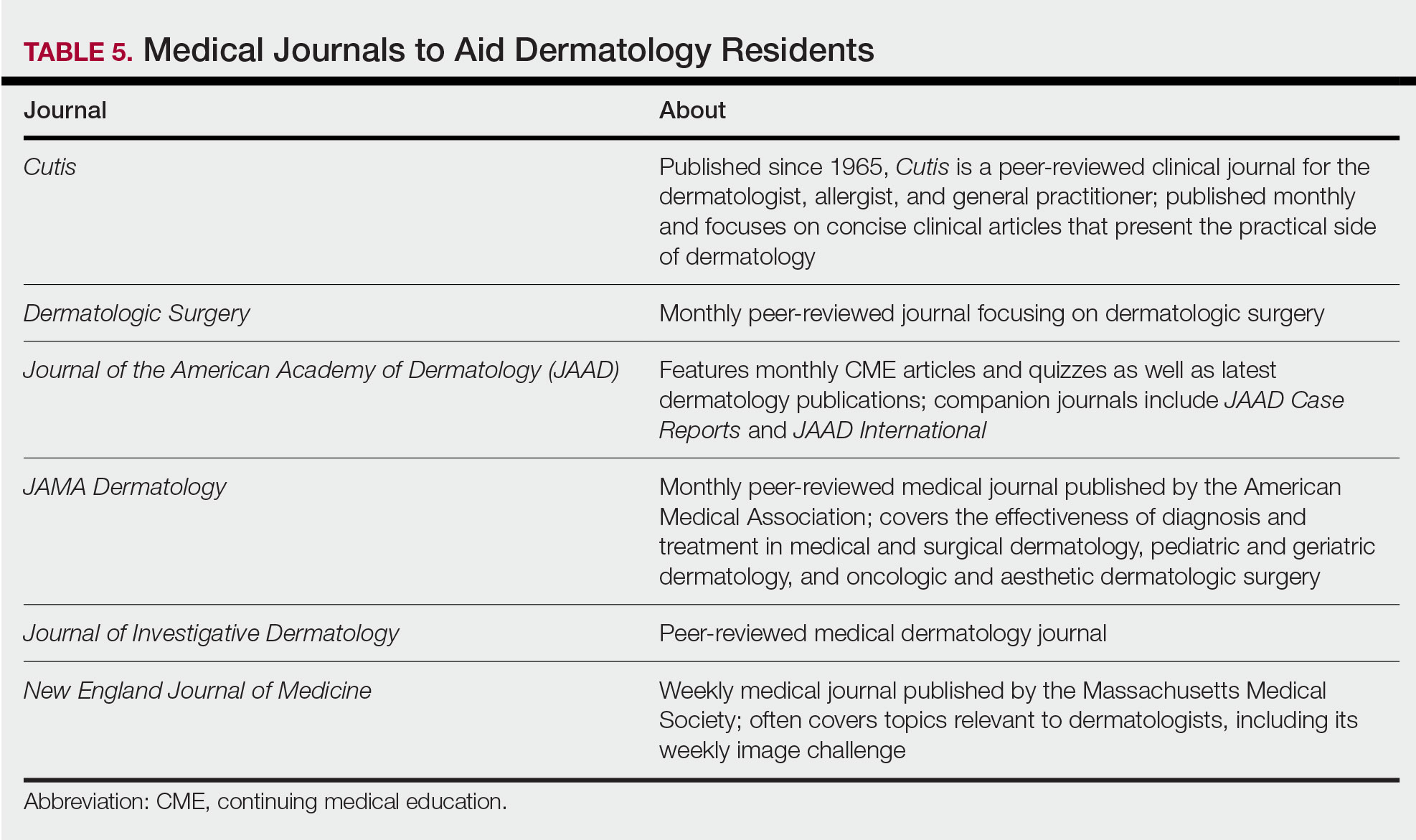

In addition to maintaining a consistent and organized study schedule, second-year residents should continue to read in depth on topics related to patients for whom they are caring and stay on top of the dermatology literature. Table 5 provides a list of medical journals that dermatology residents should aim to read. The Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology’s continuing medical education series (https://www.jaad.org/content/collection-cme) may be particularly helpful to residents. In this series, experts review a variety of dermatologic topics in depth paired with quiz questions.

Third Year

As a third-year resident (PGY-4 for most), studying should focus on deepening one’s knowledge base and beginning preparation for the boards examination. At this point, residents should stick to a limited selection of resources (ie, 1 textbook, 1 review book, 1 question bank) for in-depth study. More time should be spent on active learning, such as note-taking and question banks. Boards review courses historically have been available to dermatology residents, namely the Barron Board Review course and a plenary session at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Conference (Table 4).

Consistent Habits

Studying strategies can and should differ throughout dermatology residency, though consistency is necessary throughout. It is helpful to plan study schedules in advance—yearly, monthly, weekly—and aim to stick to them as much as possible. Finding what works for each individual may take trial and error. For some, it may mean waking up early to study before work, whereas others may do better in the evenings. It also is helpful to utilize a combination of longer blocks of studying (ie, weekend days), with consistent shorter blocks of time during the week. Many residents also learn to take advantage of time spent commuting by listening to podcasts in the car or reading while on public transportation.

Final Thoughts

There are many resources available to support residents in their learning such as textbooks, journals, podcasts, flashcards, question banks, and more. The path to mastery will be individualized for each resident, likely using a unique combination of resources. The beginning of residency is a good time to explore a variety of resources to see what works best, whereas at the end studying becomes more targeted.

- Marks Jr JG, Miller JJ. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology. 6th ed. China: Elsevier; 2019.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. China: Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018.

- Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York, NY: Springer; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. London, England: Saunders; 2015.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

Dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose, in which one is bombarded with so much information that it is impossible to retain any content. This article provides an overview of available resources and a guide on how to tailor studying throughout one’s training.

Prior to Residency

There are several resources that provide an introduction to dermatology and are appropriate for all medical students, regardless of intended specialty. The American Academy of Dermatology offers a free basic dermatology curriculum (https://www.aad.org/member/education/residents/bdc), with a choice of a 2- or 4-week course consisting of modules such as skin examination, basic science of the skin, dermatologic therapies, and specific dermatologic conditions. VisualDx offers LearnDerm (https://www.visualdx.com/learnderm/), which includes a 5-part tutorial and quiz focused on the skin examination, morphology, and lesion distribution. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology1 is a book at an appropriate level for a medical student to learn about the fundamentals of dermatology. These resources may be helpful for residents to review immediately before starting dermatology residency (toward the end of intern year for most).

First Year

During the beginning of dermatology residency (postgraduate year [PGY] 2 for most), the fire hose of information feels most daunting. During this time, studying should focus on engendering a broad overview of dermatology. Most residencies maintain a textbook reading schedule, which provides a framework from which residents may structure their studying. Selection of a textbook tends to be program dependent. Even if the details of reading the textbook do not stick when reading it the first time, benefits include becoming familiar with what information one is expected to learn as a dermatologist and developing a strong foundation upon which one may continue to build. Based on my informal discussions with current residents, some reported that reading the textbook did not work well for them, citing too much minutiae in the textbooks and/or a preference for a more active learning approach. These residents instead focused on reading a review book for a broad overview, accompanied by a textbook or VisualDx when a more detailed reference is necessary. Table 1 provides a list of textbooks and mobile applications (apps) that residents may find helpful.

First-year residents may begin their efforts in synthesizing this new knowledge base toward the end of the year in preparation for the BASIC examination. The American Board of Dermatology provides a content outline as well as sample questions on their website (https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/exam-of-the-future-information-center.aspx#content), which may be used to guide more focused studying efforts during the weeks leading up to the examination.

Second Year

For second-year residents (PGY-3 for most) studying should focus on deepening and consolidating the broad foundation that was established during their first year. For many, this pursuit involves rereading the textbook chapters alongside more active learning measures, such as taking notes and quizzing oneself using flashcard apps and question banks (Table 2). Others may benefit from listening to podcasts (Table 3) or other sources utilizing audiovisual content, including attending conferences and other lectures virtually, which is becoming increasingly available in the setting of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (Table 4). Because there are so many resources available to support these efforts, residents should be encouraged to try out a variety to determine what works best.

Toward the end of second year, studying may be tailored to preparing for the CORE examinations using the resources of one’s choice. Based on my discussions with current residents, a combination of reading review books, reviewing one’s personal notes, and quizzing through question banks and/or flashcard apps could be used.

In addition to maintaining a consistent and organized study schedule, second-year residents should continue to read in depth on topics related to patients for whom they are caring and stay on top of the dermatology literature. Table 5 provides a list of medical journals that dermatology residents should aim to read. The Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology’s continuing medical education series (https://www.jaad.org/content/collection-cme) may be particularly helpful to residents. In this series, experts review a variety of dermatologic topics in depth paired with quiz questions.

Third Year

As a third-year resident (PGY-4 for most), studying should focus on deepening one’s knowledge base and beginning preparation for the boards examination. At this point, residents should stick to a limited selection of resources (ie, 1 textbook, 1 review book, 1 question bank) for in-depth study. More time should be spent on active learning, such as note-taking and question banks. Boards review courses historically have been available to dermatology residents, namely the Barron Board Review course and a plenary session at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Conference (Table 4).

Consistent Habits

Studying strategies can and should differ throughout dermatology residency, though consistency is necessary throughout. It is helpful to plan study schedules in advance—yearly, monthly, weekly—and aim to stick to them as much as possible. Finding what works for each individual may take trial and error. For some, it may mean waking up early to study before work, whereas others may do better in the evenings. It also is helpful to utilize a combination of longer blocks of studying (ie, weekend days), with consistent shorter blocks of time during the week. Many residents also learn to take advantage of time spent commuting by listening to podcasts in the car or reading while on public transportation.

Final Thoughts

There are many resources available to support residents in their learning such as textbooks, journals, podcasts, flashcards, question banks, and more. The path to mastery will be individualized for each resident, likely using a unique combination of resources. The beginning of residency is a good time to explore a variety of resources to see what works best, whereas at the end studying becomes more targeted.

Dermatology residency can feel like drinking from a firehose, in which one is bombarded with so much information that it is impossible to retain any content. This article provides an overview of available resources and a guide on how to tailor studying throughout one’s training.

Prior to Residency

There are several resources that provide an introduction to dermatology and are appropriate for all medical students, regardless of intended specialty. The American Academy of Dermatology offers a free basic dermatology curriculum (https://www.aad.org/member/education/residents/bdc), with a choice of a 2- or 4-week course consisting of modules such as skin examination, basic science of the skin, dermatologic therapies, and specific dermatologic conditions. VisualDx offers LearnDerm (https://www.visualdx.com/learnderm/), which includes a 5-part tutorial and quiz focused on the skin examination, morphology, and lesion distribution. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology1 is a book at an appropriate level for a medical student to learn about the fundamentals of dermatology. These resources may be helpful for residents to review immediately before starting dermatology residency (toward the end of intern year for most).

First Year

During the beginning of dermatology residency (postgraduate year [PGY] 2 for most), the fire hose of information feels most daunting. During this time, studying should focus on engendering a broad overview of dermatology. Most residencies maintain a textbook reading schedule, which provides a framework from which residents may structure their studying. Selection of a textbook tends to be program dependent. Even if the details of reading the textbook do not stick when reading it the first time, benefits include becoming familiar with what information one is expected to learn as a dermatologist and developing a strong foundation upon which one may continue to build. Based on my informal discussions with current residents, some reported that reading the textbook did not work well for them, citing too much minutiae in the textbooks and/or a preference for a more active learning approach. These residents instead focused on reading a review book for a broad overview, accompanied by a textbook or VisualDx when a more detailed reference is necessary. Table 1 provides a list of textbooks and mobile applications (apps) that residents may find helpful.

First-year residents may begin their efforts in synthesizing this new knowledge base toward the end of the year in preparation for the BASIC examination. The American Board of Dermatology provides a content outline as well as sample questions on their website (https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/exam-of-the-future-information-center.aspx#content), which may be used to guide more focused studying efforts during the weeks leading up to the examination.

Second Year

For second-year residents (PGY-3 for most) studying should focus on deepening and consolidating the broad foundation that was established during their first year. For many, this pursuit involves rereading the textbook chapters alongside more active learning measures, such as taking notes and quizzing oneself using flashcard apps and question banks (Table 2). Others may benefit from listening to podcasts (Table 3) or other sources utilizing audiovisual content, including attending conferences and other lectures virtually, which is becoming increasingly available in the setting of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (Table 4). Because there are so many resources available to support these efforts, residents should be encouraged to try out a variety to determine what works best.

Toward the end of second year, studying may be tailored to preparing for the CORE examinations using the resources of one’s choice. Based on my discussions with current residents, a combination of reading review books, reviewing one’s personal notes, and quizzing through question banks and/or flashcard apps could be used.

In addition to maintaining a consistent and organized study schedule, second-year residents should continue to read in depth on topics related to patients for whom they are caring and stay on top of the dermatology literature. Table 5 provides a list of medical journals that dermatology residents should aim to read. The Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology’s continuing medical education series (https://www.jaad.org/content/collection-cme) may be particularly helpful to residents. In this series, experts review a variety of dermatologic topics in depth paired with quiz questions.

Third Year

As a third-year resident (PGY-4 for most), studying should focus on deepening one’s knowledge base and beginning preparation for the boards examination. At this point, residents should stick to a limited selection of resources (ie, 1 textbook, 1 review book, 1 question bank) for in-depth study. More time should be spent on active learning, such as note-taking and question banks. Boards review courses historically have been available to dermatology residents, namely the Barron Board Review course and a plenary session at the American Academy of Dermatology Annual Conference (Table 4).

Consistent Habits

Studying strategies can and should differ throughout dermatology residency, though consistency is necessary throughout. It is helpful to plan study schedules in advance—yearly, monthly, weekly—and aim to stick to them as much as possible. Finding what works for each individual may take trial and error. For some, it may mean waking up early to study before work, whereas others may do better in the evenings. It also is helpful to utilize a combination of longer blocks of studying (ie, weekend days), with consistent shorter blocks of time during the week. Many residents also learn to take advantage of time spent commuting by listening to podcasts in the car or reading while on public transportation.

Final Thoughts

There are many resources available to support residents in their learning such as textbooks, journals, podcasts, flashcards, question banks, and more. The path to mastery will be individualized for each resident, likely using a unique combination of resources. The beginning of residency is a good time to explore a variety of resources to see what works best, whereas at the end studying becomes more targeted.

- Marks Jr JG, Miller JJ. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology. 6th ed. China: Elsevier; 2019.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. China: Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018.

- Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York, NY: Springer; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. London, England: Saunders; 2015.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

- Marks Jr JG, Miller JJ. Lookingbill and Marks’ Principles of Dermatology. 6th ed. China: Elsevier; 2019.

- James WD, Elston DM, Treat JR. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 13th ed. China: Elsevier; 2019.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. China: Elsevier; 2018.

- Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York, NY: Springer; 2012.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 2nd ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

- Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, eds. Neonatal and Infant Dermatology. London, England: Saunders; 2015.

- Alikhan A, Hocker TLH, eds. Review of Dermatology. China: Elsevier; 2017.

Resident Pearls

- Independent study is a large component of dermatology residency.

- Consistent habits and a tailored approach will support optimal learning for each dermatology resident.

- The beginning of residency is a good time to explore a variety of resources to see what works best. Toward the end of residency, as studying becomes more targeted, residents may benefit from sticking to the resources with which they are most comfortable.

APPlying Knowledge: Evidence for and Regulation of Mobile Apps for Dermatologists

Since the first mobile application (app) was developed in the 1990s, apps have become increasingly integrated into medical practice and training. More than 5.5 million apps were downloadable in 2019,1 of which more than 300,000 were health related.2 In the United States, more than 80% of physicians reported using smartphones for professional purposes in 2016.3 As the complexity of apps and their purpose of use has evolved, regulatory bodies have not adapted adequately to monitor apps that have broad-reaching consequences in medicine.

We review the primary literature on PubMed behind health-related apps that impact dermatologists as well as the government regulation of these apps, with a focus on the 3 most prevalent dermatology-related apps used by dermatology residents in the United States: VisualDx, UpToDate, and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria. This prevalence is according to a survey emailed to all dermatology residents in the United States by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in 2019 (unpublished data).

VisualDx

VisualDx, which aims to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient safety, contains peer-reviewed data and more than 32,000 images of dermatologic conditions. The editorial board includes more than 50 physicians. It provides opportunities for continuing medical education credit, is used in more than 2300 medical settings, and costs $399.99 annually for a subscription with partial features. Prior to the launch of the app in 2010, some health science professionals noted that the website version lacked references to primary sources.4 The same issue carried over to the app, which has evolved to offer artificial intelligence (AI) analysis of photographed skin lesions. However, there are no peer-reviewed publications showing positive impact of the app on diagnostic skills among dermatology residents or on patient outcomes.

UpToDate

UpToDate is a web-based database created in the early 1990s. A corresponding app was created around 2010. Both internal and independent research has demonstrated improved outcomes, and the app is advertised as the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes, as shown in more than 80 publications.5 UpToDate covers more than 11,800 medical topics and contains more than 35,000 graphics. It cites primary sources and uses a published system for grading recommendation strength and evidence quality. The data are processed and produced by a team of more than 7100 physicians as authors, editors, and reviewers. The platform grants continuing medical education credit and is used by more than 1.9 million clinicians in more than 190 countries. A 1-year subscription for an individual US-based physician costs $559. An observational study assessed UpToDate articles for potential conflicts of interest between authors and their recommendations. Of the 6 articles that met inclusion criteria of discussing management of medical conditions that have controversial or mostly brand-name treatment options, all had conflicts of interest, such as naming drugs from companies with which the authors and/or editors had financial relationships.6

Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria

The Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria app is a free clinical decision-making tool based on a consensus statement published in 2012 by the AAD, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery.7 It helps guide management of more than 200 dermatologic scenarios. Critique has been made that the criteria are partly based on expert opinion and data largely from the United States and has not been revised to incorporate newer data.8 There are no publications regarding the app itself.

Regulation of Health-Related Apps

Health-related apps that are designed for utilization by health care providers can be a valuable tool. However, given their prevalence, cost, and potential impact on patient lives, these apps should be well regulated and researched. The general paucity of peer-reviewed literature demonstrating the utility, safety, quality, and accuracy of health-related apps commonly used by providers is a reflection of insufficient mobile health regulation in the United States.

There are 3 primary government agencies responsible for regulating mobile medical apps: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission, and Office for Civil Rights.9 The FDA does not regulate all medical devices. Apps intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition are considered to be medical devices.10 The FDA regulates those apps only if they are judged to pose more than minimal risk. Apps that are designed only to provide easy access to information related to health conditions or treatment are considered to be minimal risk but can develop into a different risk level such as by offering AI.11 Although the FDA does update its approach to medical devices, including apps and AI- and machine learning–based software, the rate and direction of update has not kept pace with the rapid evolution of apps.12 In 2019, the FDA began piloting a precertification program that grants long-term approval to organizations that develop apps instead of reviewing each app product individually.13 This decrease in premarket oversight is intended to expedite innovation with the hopeful upside of improving patient outcomes but is inconsistent, with the FDA still reviewing other types of medical devices individually.

For apps that are already in use, the Federal Trade Commission only gets involved in response to deceptive or unfair acts or practices relating to privacy, data security, and false or misleading claims about safety or performance. It may be more beneficial for consumers if those apps had a more stringent initial approval process. The Office for Civil Rights enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act when relevant to apps.

Nongovernment agencies also are involved in app regulation. The FDA believes sharing more regulatory responsibility with private industry would promote efficiency.14 Google does not allow apps that contain false or misleading health claims,15 and Apple may scrutinize medical apps that could provide inaccurate data or be used for diagnosing or treating patients.16 Xcertia, a nonprofit organization founded by the American Medical Association and others, develops standards for the security, privacy, content, and operability of health-related apps, but those standards have not been adopted by other parties. Ultimately, nongovernment agencies are not responsible for public health and do not boast the government’s ability to enforce rules or ensure public safety.

Final Thoughts

The AAD survey of US dermatology residents found that the top consideration when choosing apps was up-to-date and accurate information; however, the 3 most prevalent apps among those same respondents did not need government approval and are not required to contain up-to-date data or to improve clinical outcomes, similar to most other health-related apps. This discrepancy is concerning considering the increasing utilization of apps for physician education and health care delivery and the increasing complexity of those apps. In light of these results, the potential decrease in federal premarket regulation suggested by the FDA’s precertification program seems inappropriate. It is important for the government to take responsibility for regulating health-related apps and to find a balance between too much regulation delaying innovation and too little regulation hurting physician training and patient care. It also is important for providers to be aware of the evidence and oversight behind the technologies they use for professional purposes.

- Clement J. Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 1st quarter 2020. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/. Published May 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- mHealth App Economics 2017/2018. Current Status and Future Trends in Mobile Health. Berlin, Germany: Research 2 Guidance; 2018.

- Healthcare Client Services. Professional usage of smartphones by doctors. Kantar website. https://www.kantarmedia.com/us/thinking-and-resources/blog/professional-usage-of-smartphones-by-doctors-2016. Published November 16, 2016. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Skhal KJ, Koffel J. VisualDx. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95:470-471.

- UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Amber KT, Dhiman G, Goodman KW. Conflict of interest in online point-of-care clinical support websites. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:578-580.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate use criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E55.

- Mobile health apps interactive tool. Federal Trade Commission website. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/mobile-health-apps-interactive-tool. Published April 2016. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §321 (2018).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Examples of software functions for which the FDA will exercise enforcement discretion. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications/examples-software-functions-which-fda-will-exercise-enforcement-discretion. Updated September 26, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)‐based software as a medical device (SaMD). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/SoftwareasaMedicalDevice/UCM635052.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Digital health software precertification (pre-cert) program. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program. Updated July 18, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Gottlieb S. Fostering medical innovation: a plan for digital health devices. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/fostering-medical-innovation-plan-digital-health-devices. Published June 15, 2017. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Restricted content: unapproved substances. Google Play website. https://play.google.com/about/restricted-content/unapproved-substances. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- App store review guidelines. Apple Developer website. https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines. Updated March 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

Since the first mobile application (app) was developed in the 1990s, apps have become increasingly integrated into medical practice and training. More than 5.5 million apps were downloadable in 2019,1 of which more than 300,000 were health related.2 In the United States, more than 80% of physicians reported using smartphones for professional purposes in 2016.3 As the complexity of apps and their purpose of use has evolved, regulatory bodies have not adapted adequately to monitor apps that have broad-reaching consequences in medicine.

We review the primary literature on PubMed behind health-related apps that impact dermatologists as well as the government regulation of these apps, with a focus on the 3 most prevalent dermatology-related apps used by dermatology residents in the United States: VisualDx, UpToDate, and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria. This prevalence is according to a survey emailed to all dermatology residents in the United States by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in 2019 (unpublished data).

VisualDx

VisualDx, which aims to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient safety, contains peer-reviewed data and more than 32,000 images of dermatologic conditions. The editorial board includes more than 50 physicians. It provides opportunities for continuing medical education credit, is used in more than 2300 medical settings, and costs $399.99 annually for a subscription with partial features. Prior to the launch of the app in 2010, some health science professionals noted that the website version lacked references to primary sources.4 The same issue carried over to the app, which has evolved to offer artificial intelligence (AI) analysis of photographed skin lesions. However, there are no peer-reviewed publications showing positive impact of the app on diagnostic skills among dermatology residents or on patient outcomes.

UpToDate

UpToDate is a web-based database created in the early 1990s. A corresponding app was created around 2010. Both internal and independent research has demonstrated improved outcomes, and the app is advertised as the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes, as shown in more than 80 publications.5 UpToDate covers more than 11,800 medical topics and contains more than 35,000 graphics. It cites primary sources and uses a published system for grading recommendation strength and evidence quality. The data are processed and produced by a team of more than 7100 physicians as authors, editors, and reviewers. The platform grants continuing medical education credit and is used by more than 1.9 million clinicians in more than 190 countries. A 1-year subscription for an individual US-based physician costs $559. An observational study assessed UpToDate articles for potential conflicts of interest between authors and their recommendations. Of the 6 articles that met inclusion criteria of discussing management of medical conditions that have controversial or mostly brand-name treatment options, all had conflicts of interest, such as naming drugs from companies with which the authors and/or editors had financial relationships.6

Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria

The Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria app is a free clinical decision-making tool based on a consensus statement published in 2012 by the AAD, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery.7 It helps guide management of more than 200 dermatologic scenarios. Critique has been made that the criteria are partly based on expert opinion and data largely from the United States and has not been revised to incorporate newer data.8 There are no publications regarding the app itself.

Regulation of Health-Related Apps

Health-related apps that are designed for utilization by health care providers can be a valuable tool. However, given their prevalence, cost, and potential impact on patient lives, these apps should be well regulated and researched. The general paucity of peer-reviewed literature demonstrating the utility, safety, quality, and accuracy of health-related apps commonly used by providers is a reflection of insufficient mobile health regulation in the United States.

There are 3 primary government agencies responsible for regulating mobile medical apps: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission, and Office for Civil Rights.9 The FDA does not regulate all medical devices. Apps intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition are considered to be medical devices.10 The FDA regulates those apps only if they are judged to pose more than minimal risk. Apps that are designed only to provide easy access to information related to health conditions or treatment are considered to be minimal risk but can develop into a different risk level such as by offering AI.11 Although the FDA does update its approach to medical devices, including apps and AI- and machine learning–based software, the rate and direction of update has not kept pace with the rapid evolution of apps.12 In 2019, the FDA began piloting a precertification program that grants long-term approval to organizations that develop apps instead of reviewing each app product individually.13 This decrease in premarket oversight is intended to expedite innovation with the hopeful upside of improving patient outcomes but is inconsistent, with the FDA still reviewing other types of medical devices individually.

For apps that are already in use, the Federal Trade Commission only gets involved in response to deceptive or unfair acts or practices relating to privacy, data security, and false or misleading claims about safety or performance. It may be more beneficial for consumers if those apps had a more stringent initial approval process. The Office for Civil Rights enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act when relevant to apps.

Nongovernment agencies also are involved in app regulation. The FDA believes sharing more regulatory responsibility with private industry would promote efficiency.14 Google does not allow apps that contain false or misleading health claims,15 and Apple may scrutinize medical apps that could provide inaccurate data or be used for diagnosing or treating patients.16 Xcertia, a nonprofit organization founded by the American Medical Association and others, develops standards for the security, privacy, content, and operability of health-related apps, but those standards have not been adopted by other parties. Ultimately, nongovernment agencies are not responsible for public health and do not boast the government’s ability to enforce rules or ensure public safety.

Final Thoughts

The AAD survey of US dermatology residents found that the top consideration when choosing apps was up-to-date and accurate information; however, the 3 most prevalent apps among those same respondents did not need government approval and are not required to contain up-to-date data or to improve clinical outcomes, similar to most other health-related apps. This discrepancy is concerning considering the increasing utilization of apps for physician education and health care delivery and the increasing complexity of those apps. In light of these results, the potential decrease in federal premarket regulation suggested by the FDA’s precertification program seems inappropriate. It is important for the government to take responsibility for regulating health-related apps and to find a balance between too much regulation delaying innovation and too little regulation hurting physician training and patient care. It also is important for providers to be aware of the evidence and oversight behind the technologies they use for professional purposes.

Since the first mobile application (app) was developed in the 1990s, apps have become increasingly integrated into medical practice and training. More than 5.5 million apps were downloadable in 2019,1 of which more than 300,000 were health related.2 In the United States, more than 80% of physicians reported using smartphones for professional purposes in 2016.3 As the complexity of apps and their purpose of use has evolved, regulatory bodies have not adapted adequately to monitor apps that have broad-reaching consequences in medicine.

We review the primary literature on PubMed behind health-related apps that impact dermatologists as well as the government regulation of these apps, with a focus on the 3 most prevalent dermatology-related apps used by dermatology residents in the United States: VisualDx, UpToDate, and Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria. This prevalence is according to a survey emailed to all dermatology residents in the United States by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in 2019 (unpublished data).

VisualDx

VisualDx, which aims to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient safety, contains peer-reviewed data and more than 32,000 images of dermatologic conditions. The editorial board includes more than 50 physicians. It provides opportunities for continuing medical education credit, is used in more than 2300 medical settings, and costs $399.99 annually for a subscription with partial features. Prior to the launch of the app in 2010, some health science professionals noted that the website version lacked references to primary sources.4 The same issue carried over to the app, which has evolved to offer artificial intelligence (AI) analysis of photographed skin lesions. However, there are no peer-reviewed publications showing positive impact of the app on diagnostic skills among dermatology residents or on patient outcomes.

UpToDate

UpToDate is a web-based database created in the early 1990s. A corresponding app was created around 2010. Both internal and independent research has demonstrated improved outcomes, and the app is advertised as the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes, as shown in more than 80 publications.5 UpToDate covers more than 11,800 medical topics and contains more than 35,000 graphics. It cites primary sources and uses a published system for grading recommendation strength and evidence quality. The data are processed and produced by a team of more than 7100 physicians as authors, editors, and reviewers. The platform grants continuing medical education credit and is used by more than 1.9 million clinicians in more than 190 countries. A 1-year subscription for an individual US-based physician costs $559. An observational study assessed UpToDate articles for potential conflicts of interest between authors and their recommendations. Of the 6 articles that met inclusion criteria of discussing management of medical conditions that have controversial or mostly brand-name treatment options, all had conflicts of interest, such as naming drugs from companies with which the authors and/or editors had financial relationships.6

Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria

The Mohs Surgery Appropriate Use Criteria app is a free clinical decision-making tool based on a consensus statement published in 2012 by the AAD, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and American Society for Mohs Surgery.7 It helps guide management of more than 200 dermatologic scenarios. Critique has been made that the criteria are partly based on expert opinion and data largely from the United States and has not been revised to incorporate newer data.8 There are no publications regarding the app itself.

Regulation of Health-Related Apps

Health-related apps that are designed for utilization by health care providers can be a valuable tool. However, given their prevalence, cost, and potential impact on patient lives, these apps should be well regulated and researched. The general paucity of peer-reviewed literature demonstrating the utility, safety, quality, and accuracy of health-related apps commonly used by providers is a reflection of insufficient mobile health regulation in the United States.

There are 3 primary government agencies responsible for regulating mobile medical apps: the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Trade Commission, and Office for Civil Rights.9 The FDA does not regulate all medical devices. Apps intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition are considered to be medical devices.10 The FDA regulates those apps only if they are judged to pose more than minimal risk. Apps that are designed only to provide easy access to information related to health conditions or treatment are considered to be minimal risk but can develop into a different risk level such as by offering AI.11 Although the FDA does update its approach to medical devices, including apps and AI- and machine learning–based software, the rate and direction of update has not kept pace with the rapid evolution of apps.12 In 2019, the FDA began piloting a precertification program that grants long-term approval to organizations that develop apps instead of reviewing each app product individually.13 This decrease in premarket oversight is intended to expedite innovation with the hopeful upside of improving patient outcomes but is inconsistent, with the FDA still reviewing other types of medical devices individually.

For apps that are already in use, the Federal Trade Commission only gets involved in response to deceptive or unfair acts or practices relating to privacy, data security, and false or misleading claims about safety or performance. It may be more beneficial for consumers if those apps had a more stringent initial approval process. The Office for Civil Rights enforces the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act when relevant to apps.

Nongovernment agencies also are involved in app regulation. The FDA believes sharing more regulatory responsibility with private industry would promote efficiency.14 Google does not allow apps that contain false or misleading health claims,15 and Apple may scrutinize medical apps that could provide inaccurate data or be used for diagnosing or treating patients.16 Xcertia, a nonprofit organization founded by the American Medical Association and others, develops standards for the security, privacy, content, and operability of health-related apps, but those standards have not been adopted by other parties. Ultimately, nongovernment agencies are not responsible for public health and do not boast the government’s ability to enforce rules or ensure public safety.

Final Thoughts

The AAD survey of US dermatology residents found that the top consideration when choosing apps was up-to-date and accurate information; however, the 3 most prevalent apps among those same respondents did not need government approval and are not required to contain up-to-date data or to improve clinical outcomes, similar to most other health-related apps. This discrepancy is concerning considering the increasing utilization of apps for physician education and health care delivery and the increasing complexity of those apps. In light of these results, the potential decrease in federal premarket regulation suggested by the FDA’s precertification program seems inappropriate. It is important for the government to take responsibility for regulating health-related apps and to find a balance between too much regulation delaying innovation and too little regulation hurting physician training and patient care. It also is important for providers to be aware of the evidence and oversight behind the technologies they use for professional purposes.

- Clement J. Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 1st quarter 2020. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/. Published May 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- mHealth App Economics 2017/2018. Current Status and Future Trends in Mobile Health. Berlin, Germany: Research 2 Guidance; 2018.

- Healthcare Client Services. Professional usage of smartphones by doctors. Kantar website. https://www.kantarmedia.com/us/thinking-and-resources/blog/professional-usage-of-smartphones-by-doctors-2016. Published November 16, 2016. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Skhal KJ, Koffel J. VisualDx. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95:470-471.

- UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Amber KT, Dhiman G, Goodman KW. Conflict of interest in online point-of-care clinical support websites. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:578-580.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate use criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E55.

- Mobile health apps interactive tool. Federal Trade Commission website. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/mobile-health-apps-interactive-tool. Published April 2016. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §321 (2018).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Examples of software functions for which the FDA will exercise enforcement discretion. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications/examples-software-functions-which-fda-will-exercise-enforcement-discretion. Updated September 26, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)‐based software as a medical device (SaMD). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/SoftwareasaMedicalDevice/UCM635052.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Digital health software precertification (pre-cert) program. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program. Updated July 18, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Gottlieb S. Fostering medical innovation: a plan for digital health devices. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/fostering-medical-innovation-plan-digital-health-devices. Published June 15, 2017. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Restricted content: unapproved substances. Google Play website. https://play.google.com/about/restricted-content/unapproved-substances. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- App store review guidelines. Apple Developer website. https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines. Updated March 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Clement J. Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 1st quarter 2020. Statista website. https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/. Published May 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- mHealth App Economics 2017/2018. Current Status and Future Trends in Mobile Health. Berlin, Germany: Research 2 Guidance; 2018.

- Healthcare Client Services. Professional usage of smartphones by doctors. Kantar website. https://www.kantarmedia.com/us/thinking-and-resources/blog/professional-usage-of-smartphones-by-doctors-2016. Published November 16, 2016. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Skhal KJ, Koffel J. VisualDx. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95:470-471.

- UpToDate is the only clinical decision support resource associated with improved outcomes. UpToDate website. https://www.uptodate.com/home/research. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550.

- Amber KT, Dhiman G, Goodman KW. Conflict of interest in online point-of-care clinical support websites. J Med Ethics. 2014;40:578-580.

- Croley JA, Joseph AK, Wagner RF Jr. Discrepancies in the Mohs micrographic surgery appropriate use criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:E55.

- Mobile health apps interactive tool. Federal Trade Commission website. https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/business-center/guidance/mobile-health-apps-interactive-tool. Published April 2016. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC §321 (2018).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Examples of software functions for which the FDA will exercise enforcement discretion. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/device-software-functions-including-mobile-medical-applications/examples-software-functions-which-fda-will-exercise-enforcement-discretion. Updated September 26, 2019. Accessed July 29, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Proposed regulatory framework for modifications to artificial intelligence/machine learning (AI/ML)‐based software as a medical device (SaMD). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/SoftwareasaMedicalDevice/UCM635052.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Digital health software precertification (pre-cert) program. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health/digital-health-software-precertification-pre-cert-program. Updated July 18, 2019. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Gottlieb S. Fostering medical innovation: a plan for digital health devices. US Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/fda-voices/fostering-medical-innovation-plan-digital-health-devices. Published June 15, 2017. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- Restricted content: unapproved substances. Google Play website. https://play.google.com/about/restricted-content/unapproved-substances. Accessed July 23, 2020.

- App store review guidelines. Apple Developer website. https://developer.apple.com/app-store/review/guidelines. Updated March 4, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2020.

Practice Points

- Physicians who are selecting an app for self-education or patient care should take into consideration the strength of the evidence supporting the app as well as the rigor of any approval process the app had to undergo.

- Only a minority of health-related apps are regulated by the government. This regulation has not kept up with the evolution of app software and may become more indirect.

Wellness for the Dermatology Resident

Resident wellness is a topic that has become increasingly important in recent years due to physician burnout. A prior Cutis Resident Corner column discussed the prevalence of physician burnout and how it can affect dermatologists.1 When discussing resident burnout, dermatology may not be a specialty that immediately comes to mind, considering that dermatology is mostly outpatient based, with few emergencies and critically ill patients. In a JAMA study assessing levels of burnout by specialty, dermatology residents were the lowest at approximately 30%.2 However, this still means that 3 out of every 10 dermatology residents feel burnt out.

Burnout in Dermatology

In 2017, results from a survey of 112 dermatology residents in Canada about burnout was published in the British Journal of Dermatology.3 The numbers were staggering; the results showed that more than 50% of dermatology residents experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and 40% had low levels of personal accomplishment. Additionally, 52% experienced low or depressed mood, 20% reported feelings of hurting themselves within the last year, and more than 25% had high anxiety levels.3

Dermatology requires a high level of daily studying, which is a major source of stress for many dermatology residents. The survey of dermatology residents in Canada showed that the top stressor for 61% of survey respondents was studying, specifically for the board examination.3 Dermatology is an academically rigorous specialty. We are responsible for recognizing every disease process affecting the skin, including hundreds that are extremely uncommon. We must understand these disease processes at a molecular level from a basic science standpoint and at a microscopic level through our knowledge of dermatopathology. Much of what we see in clinic are bread-and-butter dermatologic conditions that do not necessarily correlate with the rare diseases that we study. This differs from other specialties in which residents learn much of their specialty knowledge through their clinical work.

Current Challenges

We are training in a uniquely challenging time, providing care for our patients amid the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Many of us are dealing with constant levels of stress and worry about the health and safety of ourselves, along with our friends, families, and patients. Some residents have been redeployed to work in unfamiliar roles in the emergency department or hospital wards, while others adjust to new roles in teledermatology. I also cannot talk about resident wellness without recognizing the challenges faced by physicians who are racial and religious minorities. This is especially true for black physicians, as they face unconscious biases and microaggressions daily derived from implicit racism; this leads to discrimination in every area of life and ultimately harms their emotional and psychological well-being.4 Additionally, black physicians are underrepresented in dermatology, making up only 4.3% of dermatology residents in the 2013-2014 academic year.5,6 Underrepresentation can serve as a major stressor for racial and religious minorities and should be considered when addressing resident wellness to ensure their voices are heard and validated.

Focusing on Wellness

What can we do to improve wellness? A viewpoint published in JAMA Surgery in 2015 by Salles et al7 from the Stanford University Department of Surgery (Stanford, California) discussed their Balance in Life (BIL) program, which was established after one of their residency graduates tragically died by suicide shortly after graduating from residency. The BIL program addresses 4 different facets of well-being—professional, physical, psychological, and social—and lists the specific actions taken to improve these areas of well-being.7

I completed my transitional year residency at St. Vincent Hospital (Indianapolis, Indiana). The program emphasizes the importance of resident wellness. They established a department-sponsored well-being program to improve resident wellness,8 with its objectives aligning with the 4 areas of well-being that were outlined in the Stanford viewpoint.7 A short Q&A with me was published in the supplemental material as a way of highlighting their residents.9 I will outline the 4 areas of well-being, with suggestions based on the Stanford BIL program, the well-being innovation program at St. Vincent, and initiatives at my current dermatology residency program at the University of Wisconsin (UW) in Madison.

The 4 Areas of Well-being

Stanford BIL Program

One of the changes implemented was starting a resident mentorship program. Each junior resident selects a senior resident as a mentor with department-sponsored quarterly lunch meetings.7 Another initiative is a leadership training program, which includes an outdoor rope course each year focusing on leadership and team building.7

UW Dermatology

Monthly meetings are held with our program director and coordinator so that we can address any concerns or issues as they arise and brainstorm solutions together. During the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, we had weekly resident town halls with department leadership with transparency about our institution’s current status.

Physical Well-being

Stanford BIL Program

One method of improving physical well-being included stocking healthy snacks for residents and providing incoming residents with a guide of physicians, dentists, and fitness venues to promote regular health care. We have adopted the same at UW with healthy snacks available in our resident workroom.

St. Vincent Internal Medicine Wellness

There are monthly fitness challenges for a variety of physical wellness activities such as sleep, mindfulness minutes, nutrition, and step challenges.8

UW Dermatology

In addition to healthy snacks in our workroom, we also have various discounted fitness classes available for employees, along with discounts on gym memberships, kayak rentals, and city bike-share programs.

Psychological Well-Being

Stanford BIL Program

They enlisted a clinical psychologist available for residents to talk to regularly about any issues they face and to help manage stress in their lives.7

St. Vincent Internal Medicine Wellness

Faculty and coordinators provide S.A.F.E.—secure, affirming, friendly, and empathetic—zones to provide confidential and judgment-free support for residents.8 They also host photography competitions; residents submit photographs of nature, and the winning photographs are printed and displayed throughout the work area.

UW Dermatology

We have made changes to beautify our resident workroom with photograph collages of residents and other assorted décor to make it a more work-friendly space.

Social Well-being

Common themes highlighted by all 3 programs include the importance of socializing outside of the workplace, team-building activities, and resident retreats. Social media accounts on Instagram at St. Vincent (@stvimresidency) and at UW (@uwderm) highlight resident accomplishments and promote interconnectedness when residents are not together in clinics or hospitals.

Final Thoughts

Resident wellness will continue to be an important topic for discussion in the future, especially given the uncertain times right now during our training. Focusing on the 4 areas of well-being can help to prevent burnout and improve resident wellness.

- Croley JAA. #Dermlife and the burned-out resident. Cutis. 2019;104:E32-E33.

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320:1114-1130.

- Shoimer I, Patten S, Mydlarski PR. Burnout in dermatology residents: a Canadian perspective [published online November 1, 2017]. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:270-271.

- Grills CN, Aird EG, Rowe D. Breathe, baby, breathe: clearing the way for the emotional emancipation of black people. Cultural Studies & Critical Methodologies. 2016;16:333-343.

- Imadojemu S, James WD. Increasing African American representation in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:15-16.

- Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate medical education, 2013-2014. JAMA. 2014;312:2427-2445.

- Salles A, Liebert CA, Greco RS. Promoting balance in the lives of resident physicians: a call to action. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:607-608.

- Fick L, Axon K, Potini Y, et al. Improving overall resident and faculty wellbeing through program-sponsored innovations. MedEdPublish. Published September 27, 2019. doi:10.15694/mep.2019.000184.1.

- St. Vincent Internal Medicine Residency Wellness Bulletin. https://www.mededpublish.org/manuscriptfiles/2586/Supplementary%20File%203_Wellness%20Bulletin.pdf. Published April 2018. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Resident wellness is a topic that has become increasingly important in recent years due to physician burnout. A prior Cutis Resident Corner column discussed the prevalence of physician burnout and how it can affect dermatologists.1 When discussing resident burnout, dermatology may not be a specialty that immediately comes to mind, considering that dermatology is mostly outpatient based, with few emergencies and critically ill patients. In a JAMA study assessing levels of burnout by specialty, dermatology residents were the lowest at approximately 30%.2 However, this still means that 3 out of every 10 dermatology residents feel burnt out.

Burnout in Dermatology

In 2017, results from a survey of 112 dermatology residents in Canada about burnout was published in the British Journal of Dermatology.3 The numbers were staggering; the results showed that more than 50% of dermatology residents experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and 40% had low levels of personal accomplishment. Additionally, 52% experienced low or depressed mood, 20% reported feelings of hurting themselves within the last year, and more than 25% had high anxiety levels.3

Dermatology requires a high level of daily studying, which is a major source of stress for many dermatology residents. The survey of dermatology residents in Canada showed that the top stressor for 61% of survey respondents was studying, specifically for the board examination.3 Dermatology is an academically rigorous specialty. We are responsible for recognizing every disease process affecting the skin, including hundreds that are extremely uncommon. We must understand these disease processes at a molecular level from a basic science standpoint and at a microscopic level through our knowledge of dermatopathology. Much of what we see in clinic are bread-and-butter dermatologic conditions that do not necessarily correlate with the rare diseases that we study. This differs from other specialties in which residents learn much of their specialty knowledge through their clinical work.

Current Challenges

We are training in a uniquely challenging time, providing care for our patients amid the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Many of us are dealing with constant levels of stress and worry about the health and safety of ourselves, along with our friends, families, and patients. Some residents have been redeployed to work in unfamiliar roles in the emergency department or hospital wards, while others adjust to new roles in teledermatology. I also cannot talk about resident wellness without recognizing the challenges faced by physicians who are racial and religious minorities. This is especially true for black physicians, as they face unconscious biases and microaggressions daily derived from implicit racism; this leads to discrimination in every area of life and ultimately harms their emotional and psychological well-being.4 Additionally, black physicians are underrepresented in dermatology, making up only 4.3% of dermatology residents in the 2013-2014 academic year.5,6 Underrepresentation can serve as a major stressor for racial and religious minorities and should be considered when addressing resident wellness to ensure their voices are heard and validated.

Focusing on Wellness

What can we do to improve wellness? A viewpoint published in JAMA Surgery in 2015 by Salles et al7 from the Stanford University Department of Surgery (Stanford, California) discussed their Balance in Life (BIL) program, which was established after one of their residency graduates tragically died by suicide shortly after graduating from residency. The BIL program addresses 4 different facets of well-being—professional, physical, psychological, and social—and lists the specific actions taken to improve these areas of well-being.7

I completed my transitional year residency at St. Vincent Hospital (Indianapolis, Indiana). The program emphasizes the importance of resident wellness. They established a department-sponsored well-being program to improve resident wellness,8 with its objectives aligning with the 4 areas of well-being that were outlined in the Stanford viewpoint.7 A short Q&A with me was published in the supplemental material as a way of highlighting their residents.9 I will outline the 4 areas of well-being, with suggestions based on the Stanford BIL program, the well-being innovation program at St. Vincent, and initiatives at my current dermatology residency program at the University of Wisconsin (UW) in Madison.

The 4 Areas of Well-being

Stanford BIL Program

One of the changes implemented was starting a resident mentorship program. Each junior resident selects a senior resident as a mentor with department-sponsored quarterly lunch meetings.7 Another initiative is a leadership training program, which includes an outdoor rope course each year focusing on leadership and team building.7

UW Dermatology

Monthly meetings are held with our program director and coordinator so that we can address any concerns or issues as they arise and brainstorm solutions together. During the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, we had weekly resident town halls with department leadership with transparency about our institution’s current status.

Physical Well-being

Stanford BIL Program

One method of improving physical well-being included stocking healthy snacks for residents and providing incoming residents with a guide of physicians, dentists, and fitness venues to promote regular health care. We have adopted the same at UW with healthy snacks available in our resident workroom.

St. Vincent Internal Medicine Wellness

There are monthly fitness challenges for a variety of physical wellness activities such as sleep, mindfulness minutes, nutrition, and step challenges.8

UW Dermatology

In addition to healthy snacks in our workroom, we also have various discounted fitness classes available for employees, along with discounts on gym memberships, kayak rentals, and city bike-share programs.

Psychological Well-Being

Stanford BIL Program

They enlisted a clinical psychologist available for residents to talk to regularly about any issues they face and to help manage stress in their lives.7

St. Vincent Internal Medicine Wellness

Faculty and coordinators provide S.A.F.E.—secure, affirming, friendly, and empathetic—zones to provide confidential and judgment-free support for residents.8 They also host photography competitions; residents submit photographs of nature, and the winning photographs are printed and displayed throughout the work area.

UW Dermatology

We have made changes to beautify our resident workroom with photograph collages of residents and other assorted décor to make it a more work-friendly space.

Social Well-being

Common themes highlighted by all 3 programs include the importance of socializing outside of the workplace, team-building activities, and resident retreats. Social media accounts on Instagram at St. Vincent (@stvimresidency) and at UW (@uwderm) highlight resident accomplishments and promote interconnectedness when residents are not together in clinics or hospitals.

Final Thoughts

Resident wellness will continue to be an important topic for discussion in the future, especially given the uncertain times right now during our training. Focusing on the 4 areas of well-being can help to prevent burnout and improve resident wellness.

Resident wellness is a topic that has become increasingly important in recent years due to physician burnout. A prior Cutis Resident Corner column discussed the prevalence of physician burnout and how it can affect dermatologists.1 When discussing resident burnout, dermatology may not be a specialty that immediately comes to mind, considering that dermatology is mostly outpatient based, with few emergencies and critically ill patients. In a JAMA study assessing levels of burnout by specialty, dermatology residents were the lowest at approximately 30%.2 However, this still means that 3 out of every 10 dermatology residents feel burnt out.

Burnout in Dermatology

In 2017, results from a survey of 112 dermatology residents in Canada about burnout was published in the British Journal of Dermatology.3 The numbers were staggering; the results showed that more than 50% of dermatology residents experienced high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and 40% had low levels of personal accomplishment. Additionally, 52% experienced low or depressed mood, 20% reported feelings of hurting themselves within the last year, and more than 25% had high anxiety levels.3

Dermatology requires a high level of daily studying, which is a major source of stress for many dermatology residents. The survey of dermatology residents in Canada showed that the top stressor for 61% of survey respondents was studying, specifically for the board examination.3 Dermatology is an academically rigorous specialty. We are responsible for recognizing every disease process affecting the skin, including hundreds that are extremely uncommon. We must understand these disease processes at a molecular level from a basic science standpoint and at a microscopic level through our knowledge of dermatopathology. Much of what we see in clinic are bread-and-butter dermatologic conditions that do not necessarily correlate with the rare diseases that we study. This differs from other specialties in which residents learn much of their specialty knowledge through their clinical work.

Current Challenges

We are training in a uniquely challenging time, providing care for our patients amid the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Many of us are dealing with constant levels of stress and worry about the health and safety of ourselves, along with our friends, families, and patients. Some residents have been redeployed to work in unfamiliar roles in the emergency department or hospital wards, while others adjust to new roles in teledermatology. I also cannot talk about resident wellness without recognizing the challenges faced by physicians who are racial and religious minorities. This is especially true for black physicians, as they face unconscious biases and microaggressions daily derived from implicit racism; this leads to discrimination in every area of life and ultimately harms their emotional and psychological well-being.4 Additionally, black physicians are underrepresented in dermatology, making up only 4.3% of dermatology residents in the 2013-2014 academic year.5,6 Underrepresentation can serve as a major stressor for racial and religious minorities and should be considered when addressing resident wellness to ensure their voices are heard and validated.

Focusing on Wellness

What can we do to improve wellness? A viewpoint published in JAMA Surgery in 2015 by Salles et al7 from the Stanford University Department of Surgery (Stanford, California) discussed their Balance in Life (BIL) program, which was established after one of their residency graduates tragically died by suicide shortly after graduating from residency. The BIL program addresses 4 different facets of well-being—professional, physical, psychological, and social—and lists the specific actions taken to improve these areas of well-being.7

I completed my transitional year residency at St. Vincent Hospital (Indianapolis, Indiana). The program emphasizes the importance of resident wellness. They established a department-sponsored well-being program to improve resident wellness,8 with its objectives aligning with the 4 areas of well-being that were outlined in the Stanford viewpoint.7 A short Q&A with me was published in the supplemental material as a way of highlighting their residents.9 I will outline the 4 areas of well-being, with suggestions based on the Stanford BIL program, the well-being innovation program at St. Vincent, and initiatives at my current dermatology residency program at the University of Wisconsin (UW) in Madison.

The 4 Areas of Well-being

Stanford BIL Program

One of the changes implemented was starting a resident mentorship program. Each junior resident selects a senior resident as a mentor with department-sponsored quarterly lunch meetings.7 Another initiative is a leadership training program, which includes an outdoor rope course each year focusing on leadership and team building.7

UW Dermatology

Monthly meetings are held with our program director and coordinator so that we can address any concerns or issues as they arise and brainstorm solutions together. During the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, we had weekly resident town halls with department leadership with transparency about our institution’s current status.

Physical Well-being

Stanford BIL Program

One method of improving physical well-being included stocking healthy snacks for residents and providing incoming residents with a guide of physicians, dentists, and fitness venues to promote regular health care. We have adopted the same at UW with healthy snacks available in our resident workroom.

St. Vincent Internal Medicine Wellness

There are monthly fitness challenges for a variety of physical wellness activities such as sleep, mindfulness minutes, nutrition, and step challenges.8

UW Dermatology

In addition to healthy snacks in our workroom, we also have various discounted fitness classes available for employees, along with discounts on gym memberships, kayak rentals, and city bike-share programs.

Psychological Well-Being

Stanford BIL Program

They enlisted a clinical psychologist available for residents to talk to regularly about any issues they face and to help manage stress in their lives.7

St. Vincent Internal Medicine Wellness

Faculty and coordinators provide S.A.F.E.—secure, affirming, friendly, and empathetic—zones to provide confidential and judgment-free support for residents.8 They also host photography competitions; residents submit photographs of nature, and the winning photographs are printed and displayed throughout the work area.

UW Dermatology

We have made changes to beautify our resident workroom with photograph collages of residents and other assorted décor to make it a more work-friendly space.

Social Well-being