User login

Review of Ethnoracial Representation in Clinical Trials (Phases 1 Through 4) of Atopic Dermatitis Therapies

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

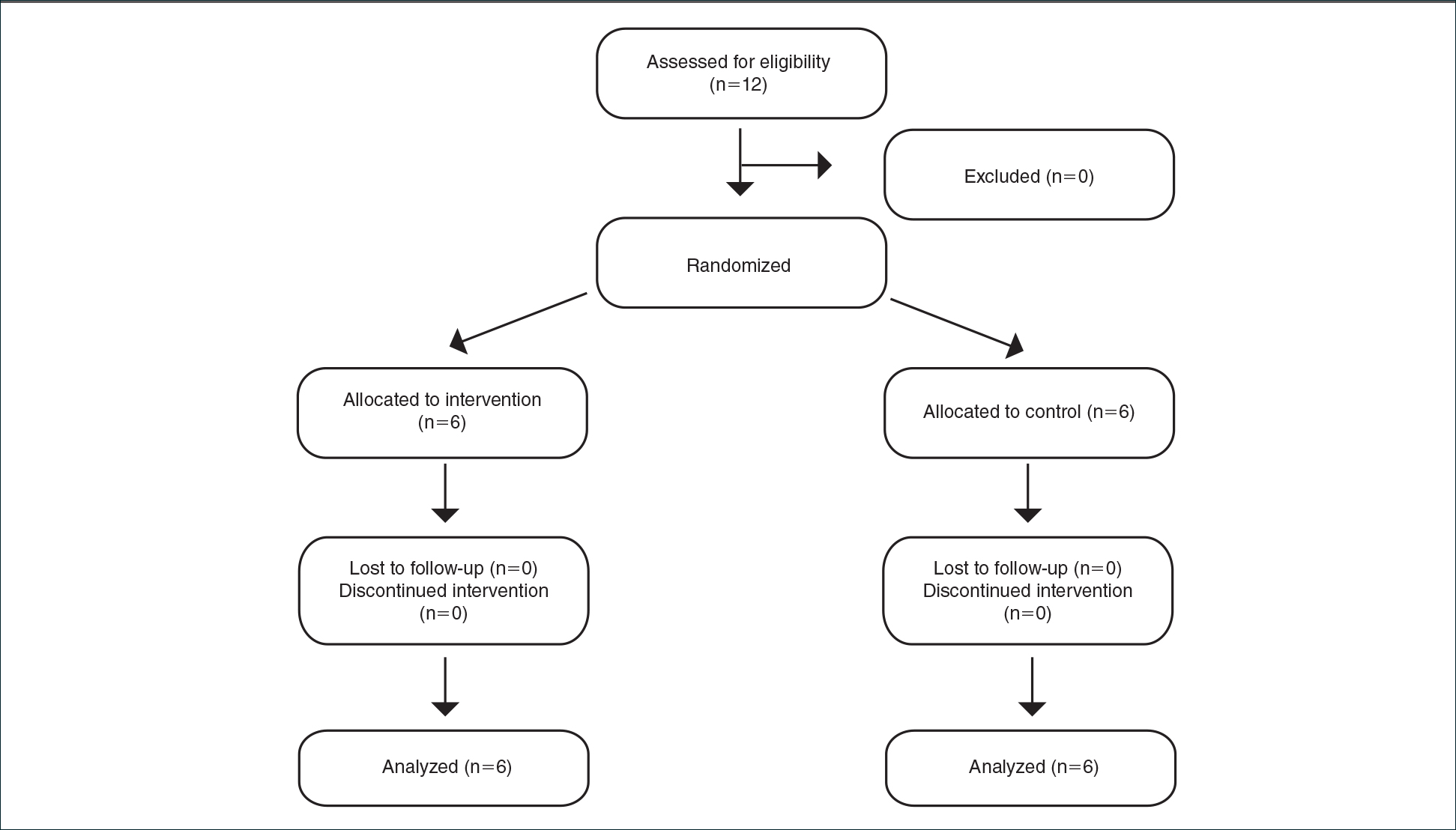

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

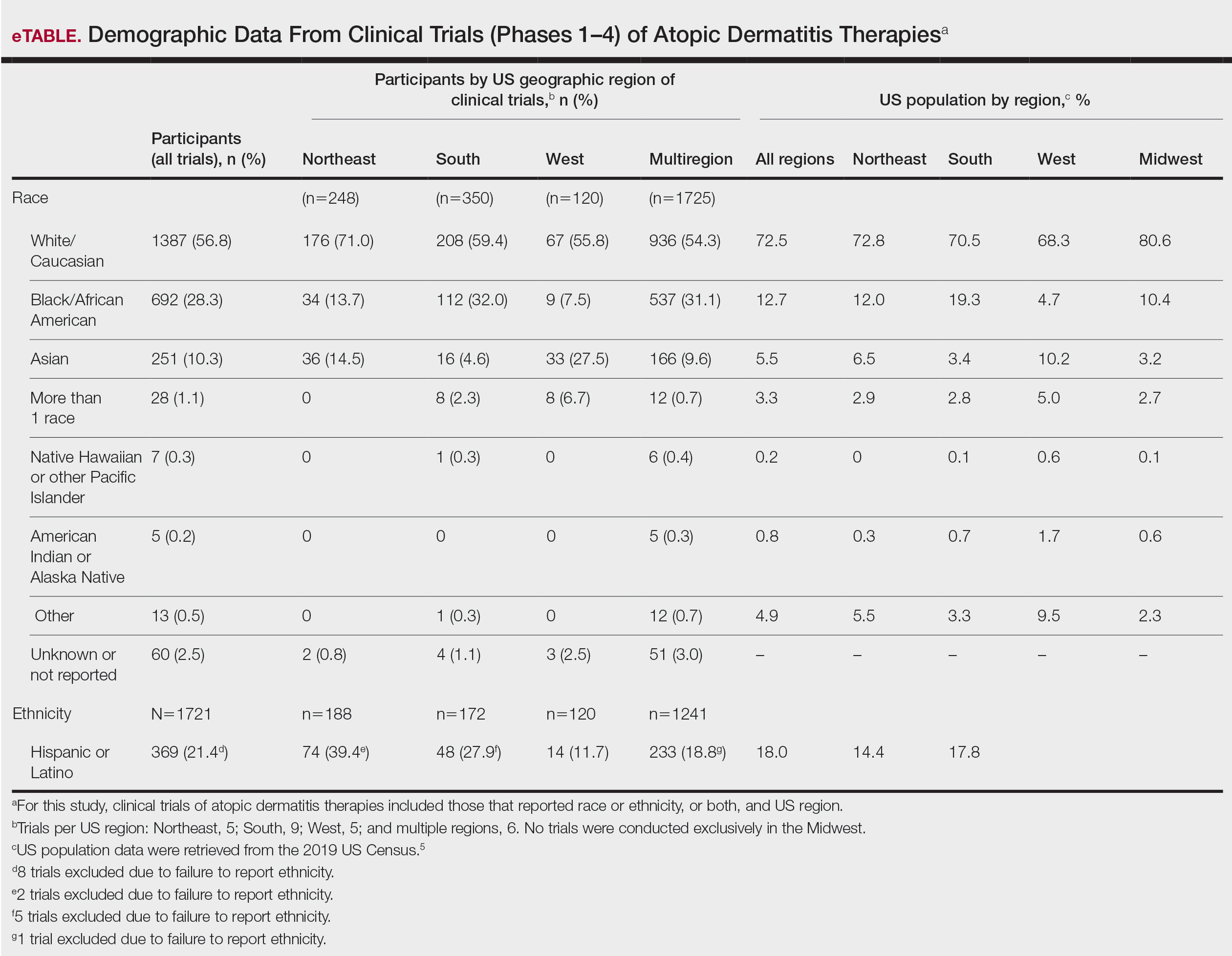

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

Practice Points

- Although minority groups are disproportionally affected by atopic dermatitis (AD), they may be underrepresented in clinical trials for AD in the United States.

- Equal representation among ethnoracial groups in clinical trials is important to allow for a more thorough investigation of the efficacy of treatments for AD.

Multiethnic Training in Residency: A Survey of Dermatology Residents

Dermatologic treatment of patients with skin of color offers specific challenges. Studies have reported structural, morphologic, and physiologic distinctions among different ethnic groups,1 which may account for distinct clinical presentations of skin disease seen in patients with skin of color. Patients with skin of color are at increased risk for specific dermatologic conditions, such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloid development, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.2,3 Furthermore, although skin cancer is less prevalent in patients with skin of color, it often presents at a more advanced stage and with a worse prognosis compared to white patients.4

Prior studies have demonstrated the need for increased exposure, education, and training in diseases pertaining to skin of color in US dermatology residency programs.6-8 The aim of this study was to assess if dermatologists in-training feel that their residency curriculum sufficiently educates them on the needs of patients with skin of color.

Methods

A 10-question anonymous survey was emailed to 109 dermatology residency programs to evaluate the attitudes of dermatology residents about their exposure to patients with skin of color and their skin-of-color curriculum. The study included individuals 18 years or older who were current residents in a dermatology program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Results

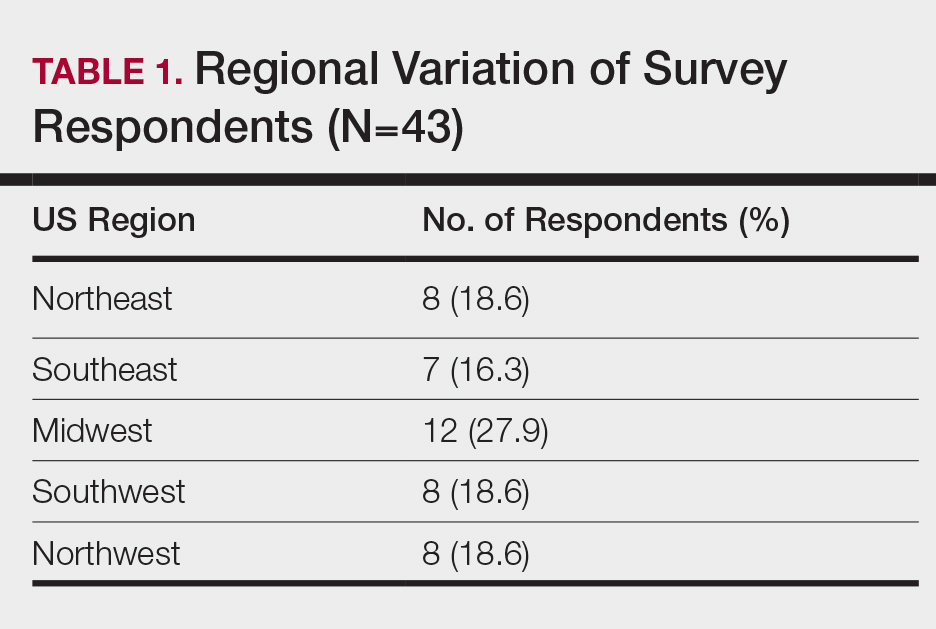

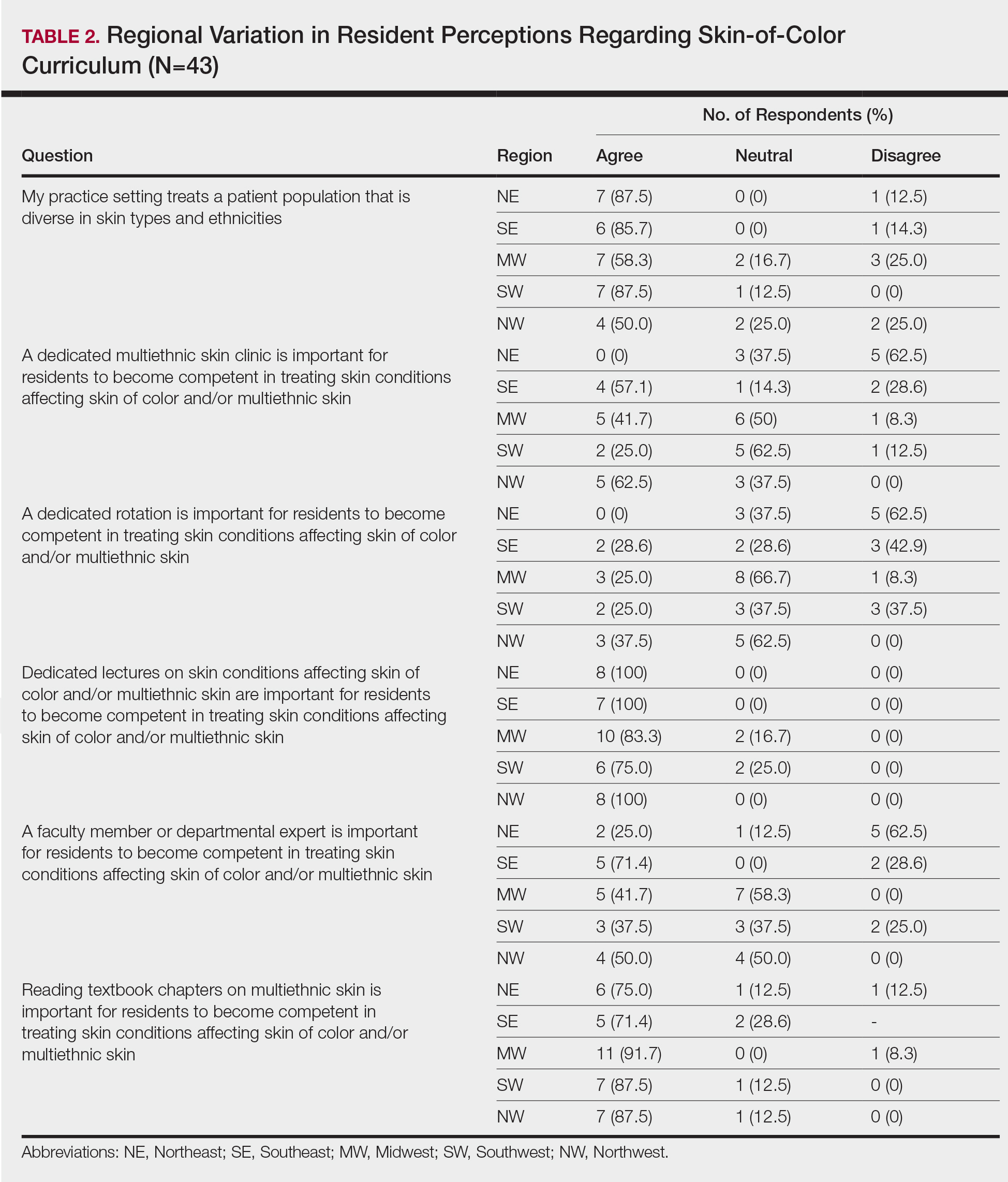

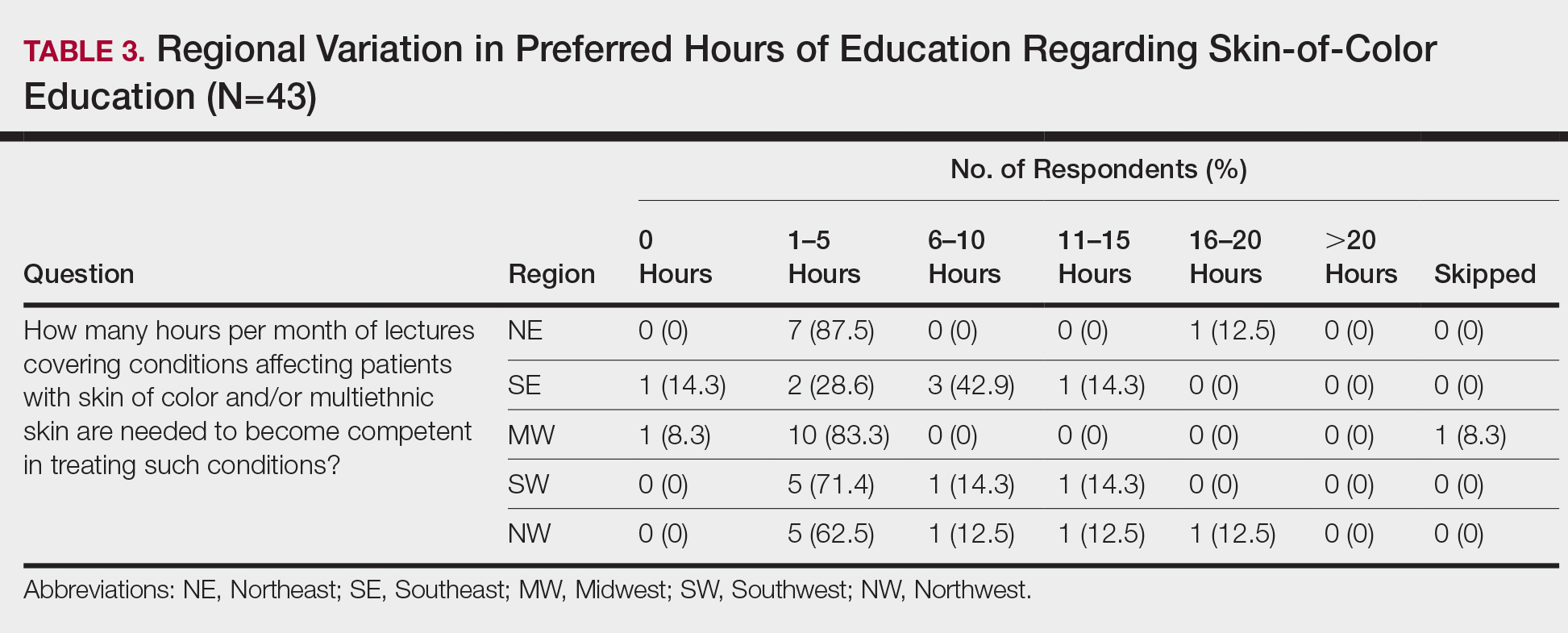

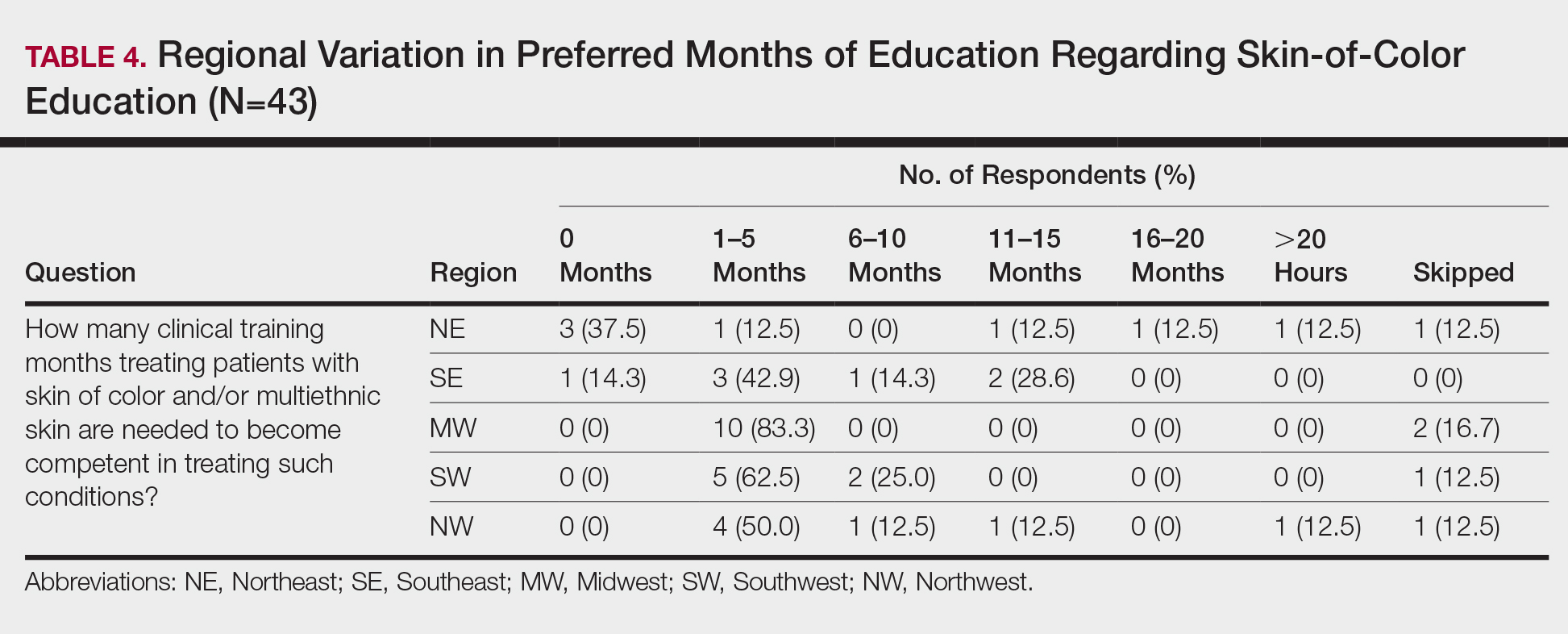

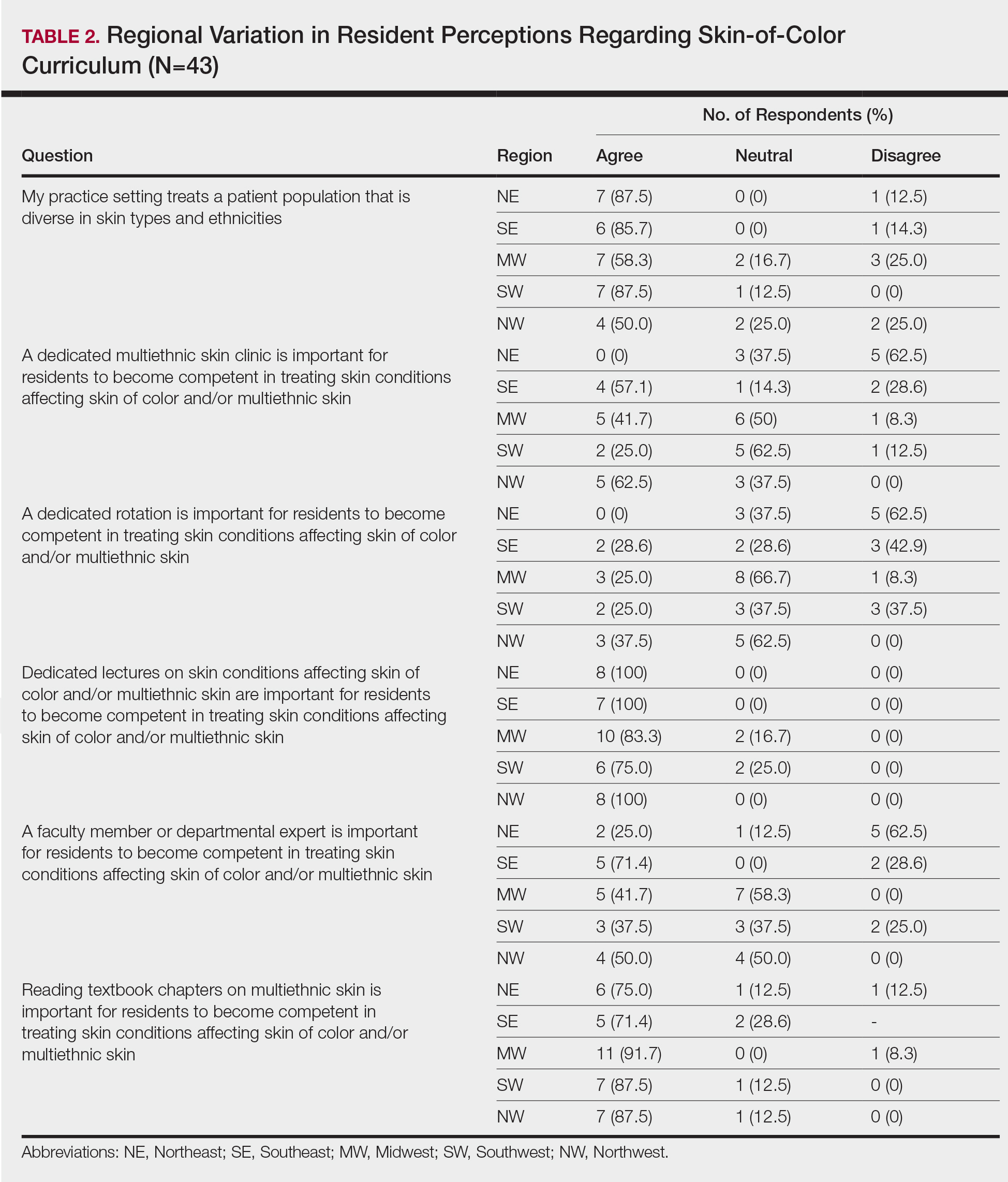

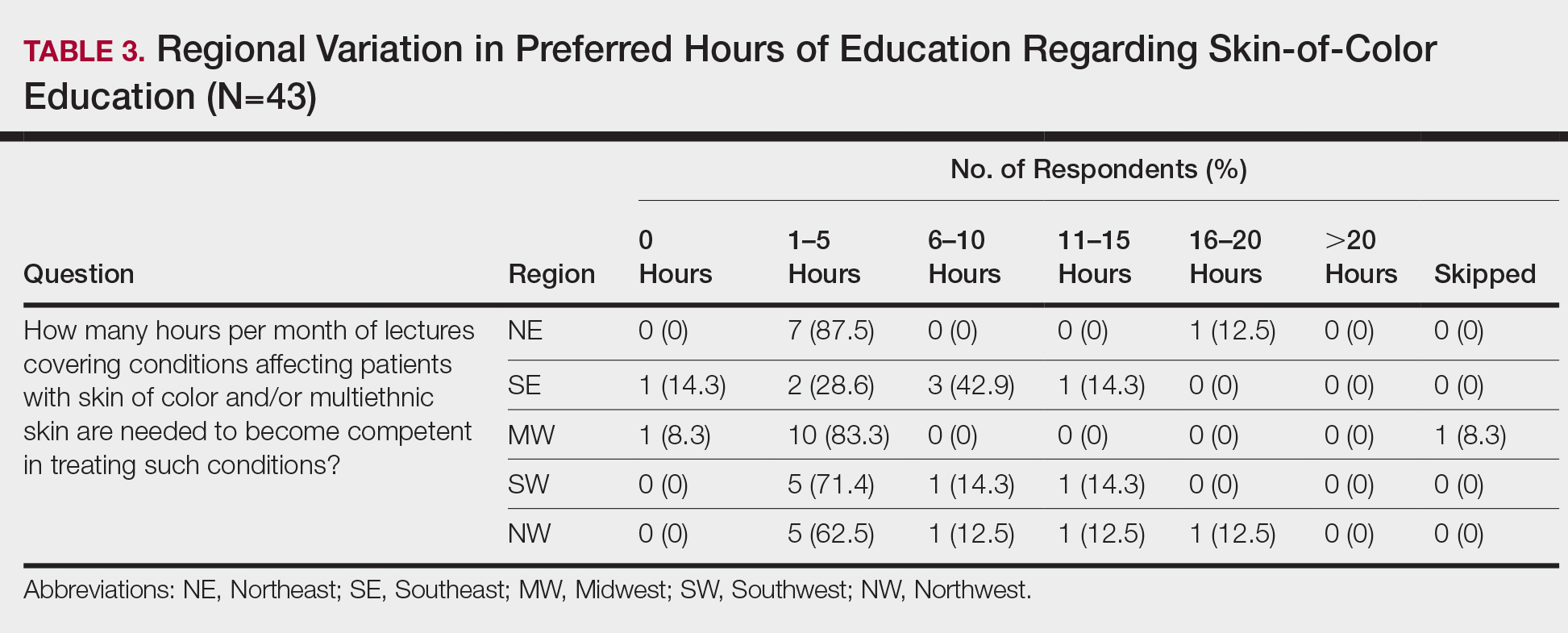

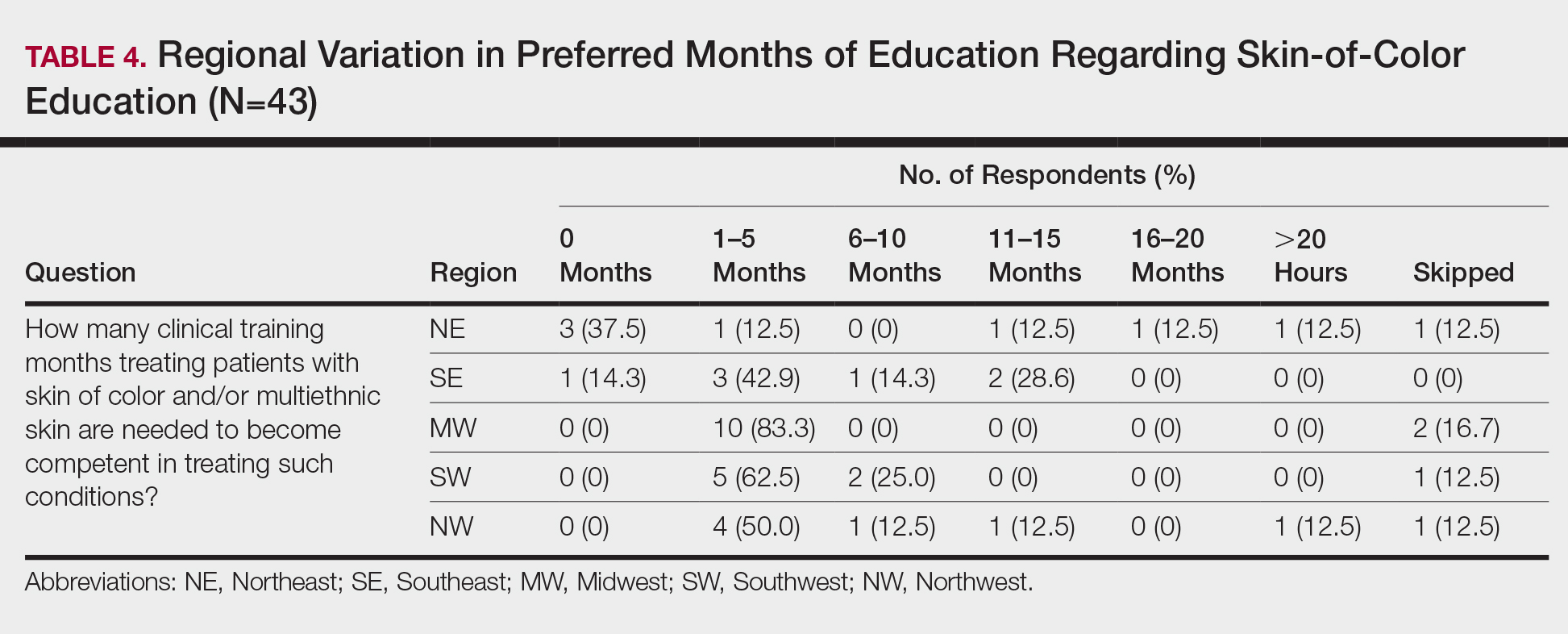

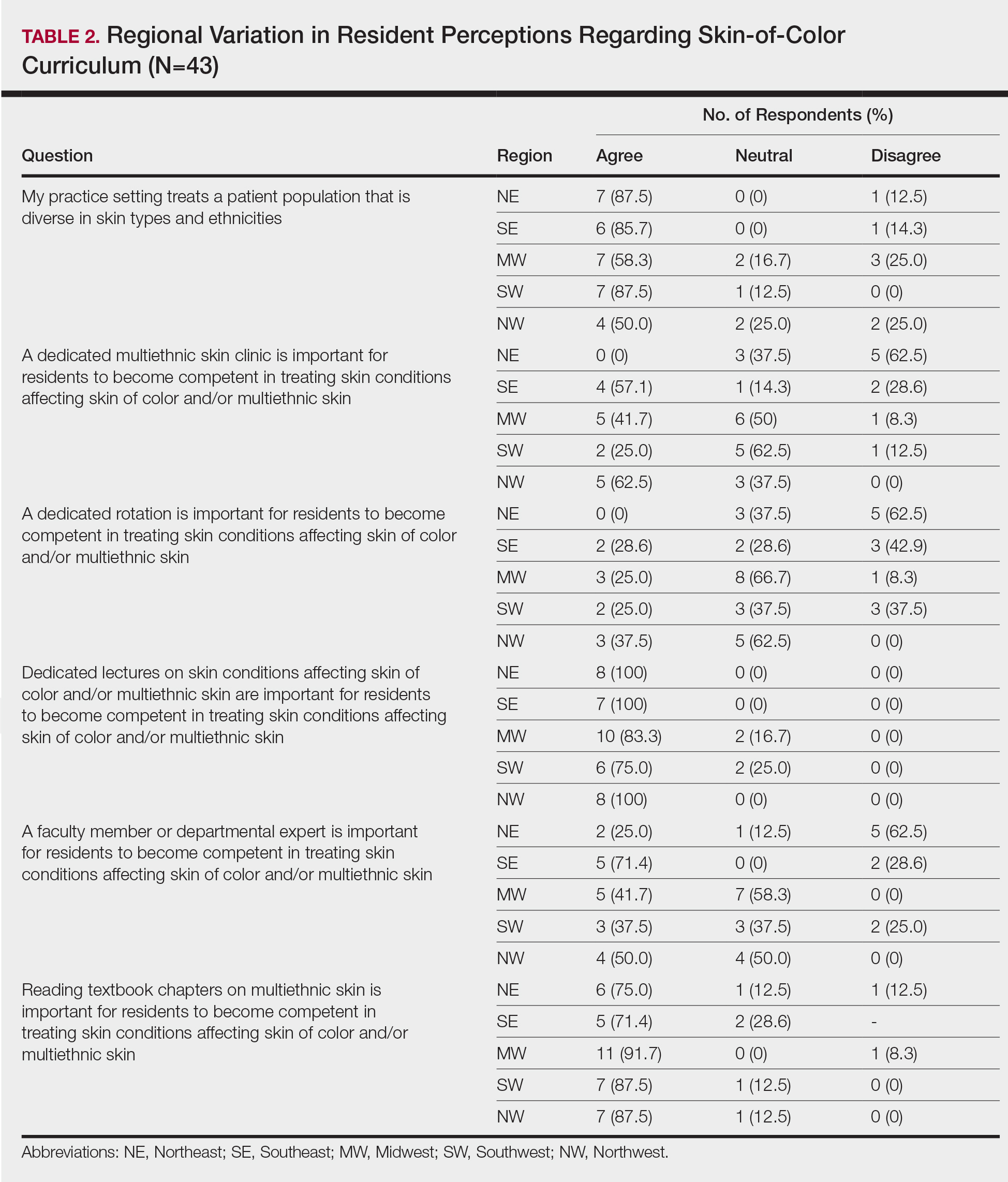

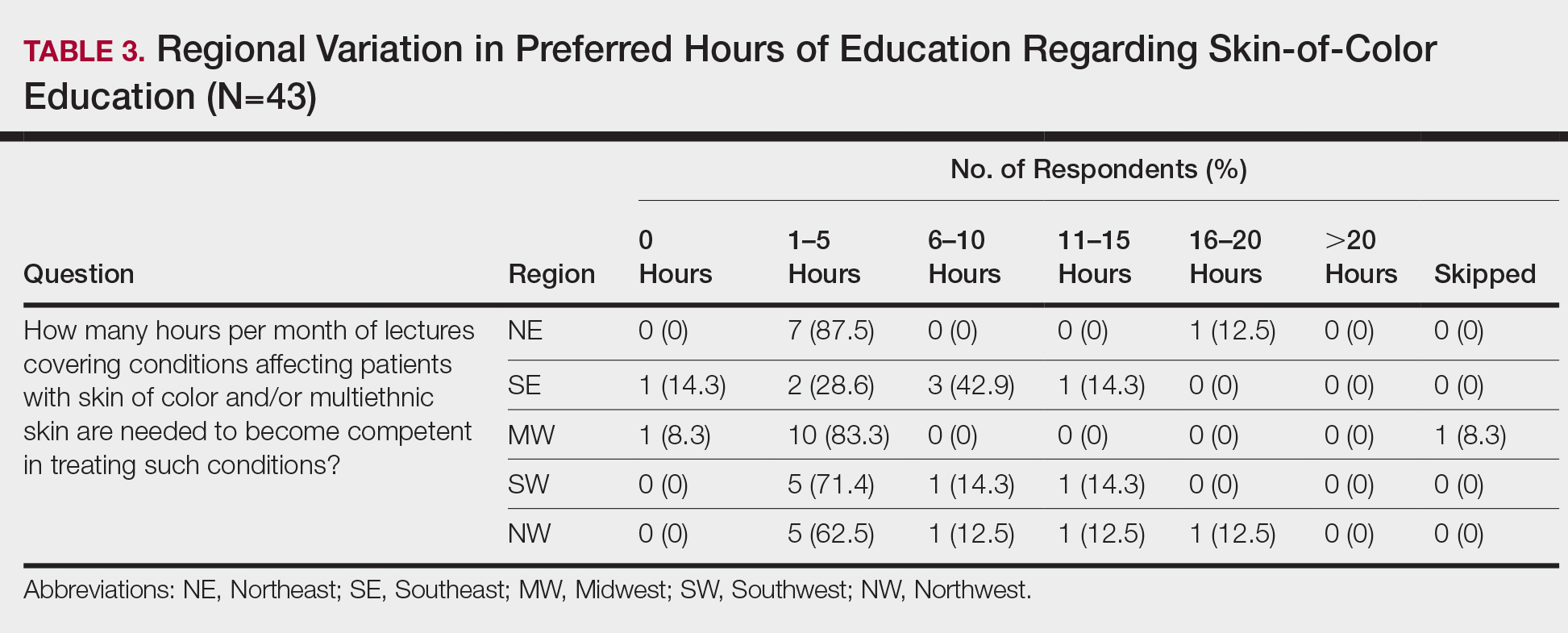

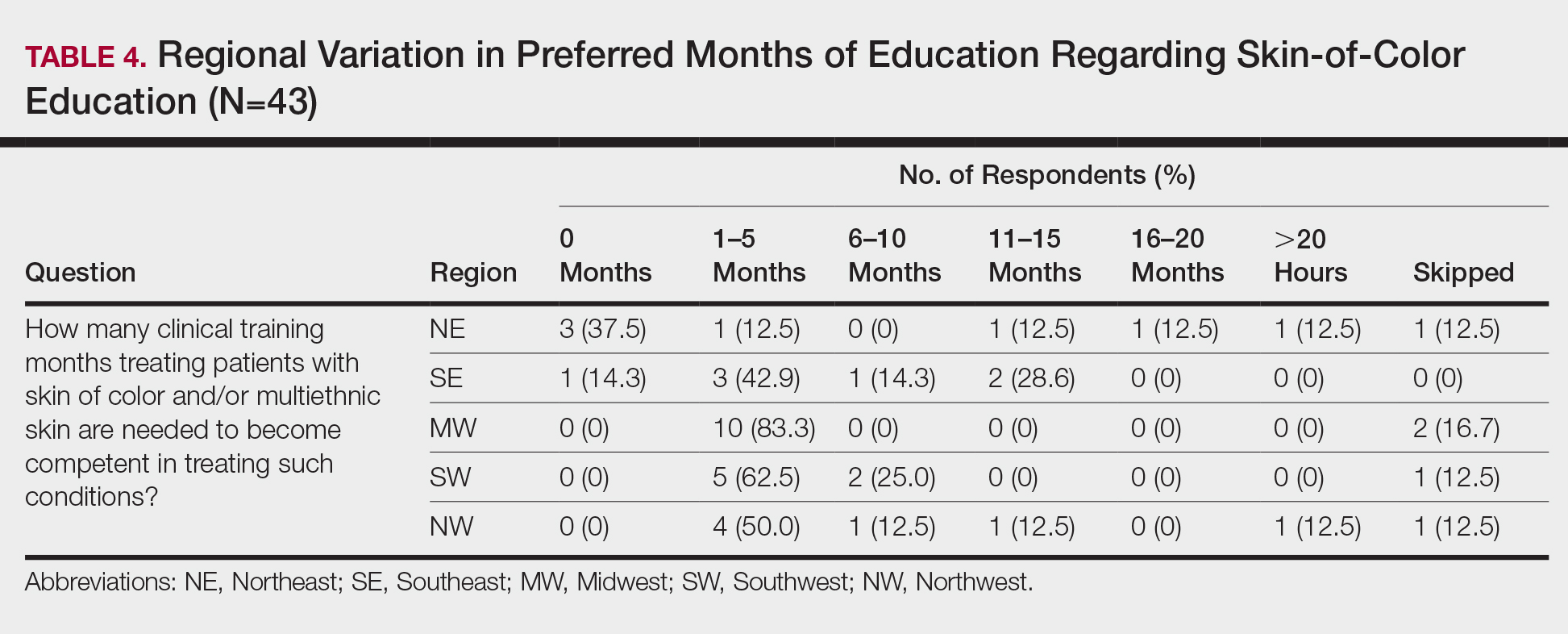

When asked the number of hours of lecture per month necessary to gain competence in conditions affecting patients with skin of color, 67% agreed that 1 to 5 hours was sufficient (Table 3). There were significant differences in the responses between the NE and SE (P=.024) and the SE and MW (P=.007). Of all respondents, 53% reported 1 to 5 months of clinical training are needed to gain competence in treating conditions affecting patients with skin of color, with significant differences in responses between the NE and MW (P<.001), the NE and SW (P=.019), and the SE and MW (P=.015)(Table 4).

Comment

Responses varied by practicing region

Although interactive lectures and textbook readings are important for obtaining a foundational understanding of dermatologic disease, they cannot substitute for clinical interactions and hands-on experience treating patients with skin of color.9 Not only do clinical interactions encourage independent reading and the study of encountered diagnoses, but intercommunication with patients may have a more profound and lasting impact on residents’ education.

Different regions of the United States have varying distributions of patients with skin of color, and dermatology residency program training reflects these disparities.6 In areas of less diversity, dermatology residents examine, diagnose, and treat substantially fewer patients with skin of color. The desire for more diverse training supports the prior findings of Nijhawan et al6 and is reflected in the responses we received in our study, whereby residents from the less ethnically diversified regions of the MW and NW were more likely to agree that clinics and rotations were necessary for training in preparation to sufficiently address the needs of patients with skin of color.

One way to compensate for the lack of ethnic diversity encountered in areas such as the MW and NW would be to develop educational programs featuring experts on skin of color.6 These specialists would not only train dermatology residents in areas of the country currently lacking ethnic diversity but also expand the expertise for treating patients with skin of color. Additionally, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and externships devoted solely to treating patients with skin of color could be encouraged for residency training.6 Finally, community outreach through volunteer clinics may provide residents exposure to patients with skin of color seeking dermatologic care.10

This study was limited by the small number of respondents, but we were able to extract important trends and data from the collected responses. It is possible that respondents felt strongly about topics involving patients with skin of color, and the results were skewed to reflect individual bias. Additional limitations included not asking respondents for program names and population density (eg, urban, suburban, rural). Future studies should be directed toward analyzing how the diversity of the local population influences training in patients with skin of color, comparing program directors’ perceptions with residents’ perceptions on training in skin of color, and assessing patient perception of residents’ training in skin of color.

Conclusion

In the last decade it has become increasingly apparent that the US population is diversifying and that patients with skin of color will comprise a substantial proportion of the future population,8,11 which emphasizes the need for dermatology residency programs to ensure that residents receive adequate training and exposure to patients with skin of color as well as the distinct skin diseases seen more commonly in these populations.12

- Luther N, Darvin ME, Sterry W, et al. Ethnic differences in skin physiology, hair follicle morphology and follicular penetration. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:182-191.

- Shokeen D. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2016;97:E9-E11.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2017;3:S21-S37.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM; US Census Bureau. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Ernst H, Colthorpe K. The efficacy of interactive lecturing for students with diverse science backgrounds. Adv Physiol Educ. 2007;31:41-44.

- Allday E. UCSF opens ‘skin of color’ dermatology clinic to address disparity in care. San Francisco Chronicle. March 20, 2019. https://www.sfchronicle.com/health/article/UCSF-opens-skin-of-color-dermatology-clinic-13704387.php. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Enos CW, Harvey VM. From bench to bedside: the Hampton University Skin of Color Research Institute 2015 Skin of Color Symposium. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S29-S30.

Dermatologic treatment of patients with skin of color offers specific challenges. Studies have reported structural, morphologic, and physiologic distinctions among different ethnic groups,1 which may account for distinct clinical presentations of skin disease seen in patients with skin of color. Patients with skin of color are at increased risk for specific dermatologic conditions, such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloid development, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.2,3 Furthermore, although skin cancer is less prevalent in patients with skin of color, it often presents at a more advanced stage and with a worse prognosis compared to white patients.4

Prior studies have demonstrated the need for increased exposure, education, and training in diseases pertaining to skin of color in US dermatology residency programs.6-8 The aim of this study was to assess if dermatologists in-training feel that their residency curriculum sufficiently educates them on the needs of patients with skin of color.

Methods

A 10-question anonymous survey was emailed to 109 dermatology residency programs to evaluate the attitudes of dermatology residents about their exposure to patients with skin of color and their skin-of-color curriculum. The study included individuals 18 years or older who were current residents in a dermatology program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Results

When asked the number of hours of lecture per month necessary to gain competence in conditions affecting patients with skin of color, 67% agreed that 1 to 5 hours was sufficient (Table 3). There were significant differences in the responses between the NE and SE (P=.024) and the SE and MW (P=.007). Of all respondents, 53% reported 1 to 5 months of clinical training are needed to gain competence in treating conditions affecting patients with skin of color, with significant differences in responses between the NE and MW (P<.001), the NE and SW (P=.019), and the SE and MW (P=.015)(Table 4).

Comment

Responses varied by practicing region

Although interactive lectures and textbook readings are important for obtaining a foundational understanding of dermatologic disease, they cannot substitute for clinical interactions and hands-on experience treating patients with skin of color.9 Not only do clinical interactions encourage independent reading and the study of encountered diagnoses, but intercommunication with patients may have a more profound and lasting impact on residents’ education.

Different regions of the United States have varying distributions of patients with skin of color, and dermatology residency program training reflects these disparities.6 In areas of less diversity, dermatology residents examine, diagnose, and treat substantially fewer patients with skin of color. The desire for more diverse training supports the prior findings of Nijhawan et al6 and is reflected in the responses we received in our study, whereby residents from the less ethnically diversified regions of the MW and NW were more likely to agree that clinics and rotations were necessary for training in preparation to sufficiently address the needs of patients with skin of color.

One way to compensate for the lack of ethnic diversity encountered in areas such as the MW and NW would be to develop educational programs featuring experts on skin of color.6 These specialists would not only train dermatology residents in areas of the country currently lacking ethnic diversity but also expand the expertise for treating patients with skin of color. Additionally, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and externships devoted solely to treating patients with skin of color could be encouraged for residency training.6 Finally, community outreach through volunteer clinics may provide residents exposure to patients with skin of color seeking dermatologic care.10

This study was limited by the small number of respondents, but we were able to extract important trends and data from the collected responses. It is possible that respondents felt strongly about topics involving patients with skin of color, and the results were skewed to reflect individual bias. Additional limitations included not asking respondents for program names and population density (eg, urban, suburban, rural). Future studies should be directed toward analyzing how the diversity of the local population influences training in patients with skin of color, comparing program directors’ perceptions with residents’ perceptions on training in skin of color, and assessing patient perception of residents’ training in skin of color.

Conclusion

In the last decade it has become increasingly apparent that the US population is diversifying and that patients with skin of color will comprise a substantial proportion of the future population,8,11 which emphasizes the need for dermatology residency programs to ensure that residents receive adequate training and exposure to patients with skin of color as well as the distinct skin diseases seen more commonly in these populations.12

Dermatologic treatment of patients with skin of color offers specific challenges. Studies have reported structural, morphologic, and physiologic distinctions among different ethnic groups,1 which may account for distinct clinical presentations of skin disease seen in patients with skin of color. Patients with skin of color are at increased risk for specific dermatologic conditions, such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloid development, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.2,3 Furthermore, although skin cancer is less prevalent in patients with skin of color, it often presents at a more advanced stage and with a worse prognosis compared to white patients.4

Prior studies have demonstrated the need for increased exposure, education, and training in diseases pertaining to skin of color in US dermatology residency programs.6-8 The aim of this study was to assess if dermatologists in-training feel that their residency curriculum sufficiently educates them on the needs of patients with skin of color.

Methods

A 10-question anonymous survey was emailed to 109 dermatology residency programs to evaluate the attitudes of dermatology residents about their exposure to patients with skin of color and their skin-of-color curriculum. The study included individuals 18 years or older who were current residents in a dermatology program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Results

When asked the number of hours of lecture per month necessary to gain competence in conditions affecting patients with skin of color, 67% agreed that 1 to 5 hours was sufficient (Table 3). There were significant differences in the responses between the NE and SE (P=.024) and the SE and MW (P=.007). Of all respondents, 53% reported 1 to 5 months of clinical training are needed to gain competence in treating conditions affecting patients with skin of color, with significant differences in responses between the NE and MW (P<.001), the NE and SW (P=.019), and the SE and MW (P=.015)(Table 4).

Comment

Responses varied by practicing region

Although interactive lectures and textbook readings are important for obtaining a foundational understanding of dermatologic disease, they cannot substitute for clinical interactions and hands-on experience treating patients with skin of color.9 Not only do clinical interactions encourage independent reading and the study of encountered diagnoses, but intercommunication with patients may have a more profound and lasting impact on residents’ education.

Different regions of the United States have varying distributions of patients with skin of color, and dermatology residency program training reflects these disparities.6 In areas of less diversity, dermatology residents examine, diagnose, and treat substantially fewer patients with skin of color. The desire for more diverse training supports the prior findings of Nijhawan et al6 and is reflected in the responses we received in our study, whereby residents from the less ethnically diversified regions of the MW and NW were more likely to agree that clinics and rotations were necessary for training in preparation to sufficiently address the needs of patients with skin of color.

One way to compensate for the lack of ethnic diversity encountered in areas such as the MW and NW would be to develop educational programs featuring experts on skin of color.6 These specialists would not only train dermatology residents in areas of the country currently lacking ethnic diversity but also expand the expertise for treating patients with skin of color. Additionally, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and externships devoted solely to treating patients with skin of color could be encouraged for residency training.6 Finally, community outreach through volunteer clinics may provide residents exposure to patients with skin of color seeking dermatologic care.10

This study was limited by the small number of respondents, but we were able to extract important trends and data from the collected responses. It is possible that respondents felt strongly about topics involving patients with skin of color, and the results were skewed to reflect individual bias. Additional limitations included not asking respondents for program names and population density (eg, urban, suburban, rural). Future studies should be directed toward analyzing how the diversity of the local population influences training in patients with skin of color, comparing program directors’ perceptions with residents’ perceptions on training in skin of color, and assessing patient perception of residents’ training in skin of color.

Conclusion

In the last decade it has become increasingly apparent that the US population is diversifying and that patients with skin of color will comprise a substantial proportion of the future population,8,11 which emphasizes the need for dermatology residency programs to ensure that residents receive adequate training and exposure to patients with skin of color as well as the distinct skin diseases seen more commonly in these populations.12

- Luther N, Darvin ME, Sterry W, et al. Ethnic differences in skin physiology, hair follicle morphology and follicular penetration. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:182-191.

- Shokeen D. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2016;97:E9-E11.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2017;3:S21-S37.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM; US Census Bureau. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Ernst H, Colthorpe K. The efficacy of interactive lecturing for students with diverse science backgrounds. Adv Physiol Educ. 2007;31:41-44.

- Allday E. UCSF opens ‘skin of color’ dermatology clinic to address disparity in care. San Francisco Chronicle. March 20, 2019. https://www.sfchronicle.com/health/article/UCSF-opens-skin-of-color-dermatology-clinic-13704387.php. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Enos CW, Harvey VM. From bench to bedside: the Hampton University Skin of Color Research Institute 2015 Skin of Color Symposium. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S29-S30.

- Luther N, Darvin ME, Sterry W, et al. Ethnic differences in skin physiology, hair follicle morphology and follicular penetration. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:182-191.

- Shokeen D. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2016;97:E9-E11.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2017;3:S21-S37.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM; US Census Bureau. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Ernst H, Colthorpe K. The efficacy of interactive lecturing for students with diverse science backgrounds. Adv Physiol Educ. 2007;31:41-44.

- Allday E. UCSF opens ‘skin of color’ dermatology clinic to address disparity in care. San Francisco Chronicle. March 20, 2019. https://www.sfchronicle.com/health/article/UCSF-opens-skin-of-color-dermatology-clinic-13704387.php. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Enos CW, Harvey VM. From bench to bedside: the Hampton University Skin of Color Research Institute 2015 Skin of Color Symposium. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S29-S30.

Practice Points

- To treat the ever-changing demographics of patients in the United States, dermatologists must receive adequate exposure and education regarding dermatologic conditions in patients from various ethnic backgrounds.

- Dermatology residents from less diverse regions are more likely to agree that dedicated clinics and rotations are important to gain competence compared to those from more diverse regions.

- In areas with less diversity, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and faculty may be more important for assuring an adequate residency experience.

Psychosocial Impact of Psoriasis: A Review for Dermatology Residents

The psychosocial impact of psoriasis is a critical component of disease burden. Psoriatic patients have high rates of depression and anxiety, problems at work, and difficulties with interpersonal relationships and intimacy.1 A National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) survey from 2003 to 2011 reported that psoriasis affects overall emotional well-being in 88% of patients and enjoyment of life in 82% of patients.2

The reasons for psychosocial burden stem from public misconceptions and disease stigma. A survey of 1005 individuals (age range, 16–64 years) about their perceptions of psoriasis revealed that 16.5% believed that psoriasis is contagious and 6.8% believed that psoriasis is related to personal hygiene.3 Fifty percent practiced discriminatory behavior toward psoriatic patients, including reluctance to shake hands (28.8%) and engage in sexual relations/intercourse (44.1%). Sixty-five percent of psoriatic patients felt their appearance is unsightly, and 73% felt self-conscious about having psoriasis.2

The psychosocial burden exists despite medical treatment of the disease. In a cross-sectional study of 1184 psoriatic patients, 70.2% had impaired quality of life (QOL) as measured by the dermatology life quality index (DLQI), even after receiving a 4-week treatment for psoriasis.4 Medical treatment of psoriasis is not enough; providers need to assess overall QOL and provide treatment and resources for these patients in addition to symptomatic management.

There have been many studies on the psychosocial burden of psoriasis, but few have focused on a dermatology resident’s role in addressing this issue. This article will review psychosocial domains—psychiatric comorbidities and social functioning including occupational functioning, interpersonal relationships, and sexual functioning— and discuss a dermatology resident’s role in assessing and addressing each of these areas.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the following terms: psoriasis, depression, anxiety, work productivity, sexual functioning, and interpersonal relationships. Selected articles covered prevalence, assessment, and management of each psychosocial domain.

Results

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Prevalence

A high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities exists in psoriatic patients. In a study of 469,097 patients with psoriasis, depression was the third most prevalent comorbidity (17.91%), following hyperlipidemia (45.64%) and hypertension (42.19%).5 In a 10-year longitudinal, population-based, prospective cohort study, antidepressant prescriptions were twice as frequent in psoriatic patients (17.8%) compared to control (7.9%)(P<.001).6 In a meta-analysis of 98 studies investigating psoriatic patients and psychiatric comorbidities, patients with psoriasis were 1.5 times more likely to experience depression (odds ratio [OR]: 1.57; 95% CI, 1.40-1.76) and use antidepressants (OR: 4.24; 95% CI, 1.53-11.76) compared to control.7 Patients with psoriasis were more likely to attempt suicide (OR: 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14-1.54) and complete suicide (OR: 1.20; 95% CI, 1.04-1.39) compared to people without psoriasis.8 A 1-year cross-sectional study of 90 psoriatic patients reported 78.7% were diagnosed with depression and 76.7% were diagnosed with anxiety. Seventy-two percent reported both anxiety and depression, correlating with worse QOL (χ2=26.7; P<.05).9

Assessment

Psychiatric comorbidities are assessed using clinical judgment and formal screening questionnaires in research studies. Signs of depression in patients with psoriasis can manifest as poor treatment adherence and recurrent flares of psoriasis.10,11 Psoriatic patients with psychiatric comorbidities were less likely to be adherent to treatment (risk ratio: 0.35; P<.003).10 The patient health questionnaire (PHQ) 9 and generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD) 7 are validated and reliable questionnaires. The first 2 questions in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 screen for depression and anxiety, respectively.12-14 These 2-question screens are practical in a fast-paced dermatology outpatient setting. Systematic questionnaires specifically targeting mood disorders may be more beneficial than the widely used DLQI, which may not adequately capture mood disorders. Over the course of 10 months, 607 patients with psoriasis were asked to fill out the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and DLQI. Thirty-eight percent of patients with major depressive disorder had a DLQI score lower than 10, while 46% of patients with generalized anxiety disorder had a DLQI score lower than 10.15 Other questionnaires, including the hospital anxiety and depression scale and Beck depression inventory, are valid instruments with high sensitivity but are commonly used for research purposes and may not be clinically feasible.16

Management

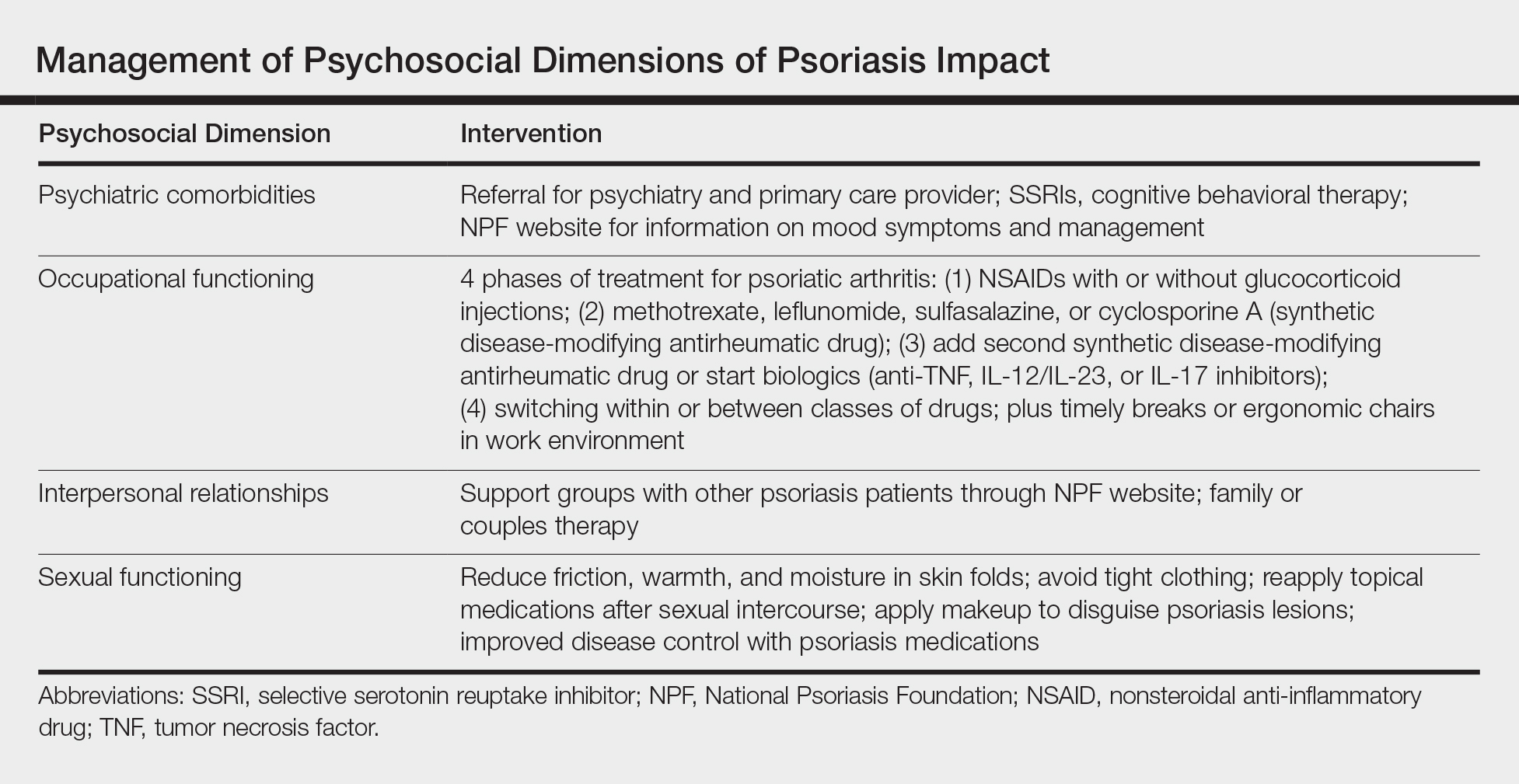

Dermatologists should refer patients with depression and/or anxiety to psychiatry. Interventions include pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management. First-line therapy for depression and anxiety is a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behavioral therapy.17 In addition, providers can direct patients to online resources such as the NPF website, where patients with psoriasis can access information about the signs and symptoms of mood disorders and contact the patient navigation center for further help.18

Social Functioning

Occupational Prevalence

The NPF found that 92% of patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (PsA) surveyed between 2003 and 2011 cited their psoriasis as reason for unemployment.2 In a survey of 43 patients asked about social and occupational functioning using the social and occupational assessment scale, 62.5% of psoriatic patients reported distress at work and 51.1% reported decreased efficiency at work.19 A national online survey that was conducted in France and issued to patients with and without psoriasis assessed overall QOL and work productivity using the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire for psoriasis (WPAI-PSO). Of 714 patients with psoriasis and PsA, the latter had a 57.6% decrease in work productivity over 7 days compared to 27.9% in controls (P<.05).20 Occupational impairment leads to lost wages and hinders advancement, further exacerbating the psychosocial burden of psoriasis.21

Occupational Assessment

Formal assessment of occupational function can be done with the WPAI-PSO, a 6-question valid instrument.22 Providers may look for risk factors associated with greater loss in work productivity to help identify and offer support for patients. Patients with increased severity of itching, pain, and scaling experienced a greater decrease in work productivity.21,23 Patients with PsA warrant early detection and treatment because they experience greater physical restraints that can interfere with work activities. Of the 459 psoriatic patients without a prior diagnosis of PsA who filled out the PsA screening and evaluation questionnaire, 144 (31.4%) received a score of 44 or higher and were referred to rheumatology for further evaluation with the classification criteria for PsA. Nine percent of patients failed to be screened and remained undiagnosed with PsA.24 In a study using the health assessment questionnaire to assess 400 patients with PsA, those with worse physical function due to joint pain and stiffness were less likely to remain employed (OR: 0.56; P=.02).25

Occupational Management

Identifying and coordinating symptoms of PsA between dermatology and rheumatology is beneficial for patients who experience debilitating symptoms. There are a variety of treatments available for PsA. According to the European League Against Rheumatism 2015 guidelines developed from expert opinion and systematic reviews for PsA management, there are 4 phases of treatment, with reassessment every 3 to 6 months for effectiveness of therapy.26,27 Phase I involves initiating nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with or without glucocorticoid injections. Phase II involves synthetic disease-modifying drugs, including methotrexate, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, or cyclosporine. Phase III involves adding a second synthetic disease-modifying drug or starting a biologic, such as an anti–tumor necrosis factor, IL-12/IL-23, or IL-17 inhibitor. Phase IV involves switching to a different drug in either aforementioned class.26,27 Treatment with biologics improves work productivity as assessed by WPAI-PSO for psoriasis and PsA.28-30 Encouraging patients to speak up in the workplace and request small accommodations such as timely breaks or ergonomic chairs can help patients feel more comfortable and supported in the work environment.18 Patients who felt supported at work were more likely to remain employed.25

Interpersonal Relationships Prevalence

Misinformation about psoriasis, fear of rejection, and feelings of isolation may contribute to interpersonal conflict. Patients have feelings of shame and self-consciousness that hinder them from engaging in social activities and seeking out relationships.31 Twenty-nine percent of patients feel that psoriasis has interfered with establishing relationships because of negative self-esteem associated with the disease,32 and 26.3% have experienced people avoiding physical contact.33 Family and spouses of patients with psoriasis may be secondarily affected due to economic and emotional distress. Ninety-eight percent of family members of psoriatic patients experienced emotional distress and 54% experienced the burden of care.34 In a survey of 63 relatives and partners of patients with psoriasis, 57% experienced psychological distress, including anxiety and worry over a psoriatic patient’s future.35

Interpersonal Relationships Assessment

Current available tools, including the DLQI and short form health survey, measure overall QOL, including social functioning, but may not be practical in a clinic setting. Although no quick-screening test to assess for this domain exists, providers are encouraged to ask patients about disease impact on interpersonal relationships. The family DLQI questionnaire, adapted from the DLQI, may help physicians and social workers evaluate the burden on a patient’s family members.34

Interpersonal Relationships Management

It may be difficult for providers to address problems with interpersonal relationships without accessible tools. Patients may not be accompanied by family or friends during appointments, and it is difficult to screen for these issues during visits. Providers may offer resources such as the NPF website, which provides information about support groups. It also provides tips on dating and connecting to others in the community who share similar experiences.18 Encouraging patients to seek family or couples therapy also may be beneficial. Increased social support can lead to better QOL and fewer depressive symptoms.36

Sexual Functioning Prevalence

Psoriasis affects both physical and psychological components of sexual function. Among 3485 patients with skin conditions who were surveyed about sexual function, 34% of psoriatic patients reported that psoriasis interfered with sexual functioning at least to a certain degree.37 Sexual impairment was strongly associated with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation; 24% of depressed patients and 20% of anxious patients experienced sexual problems a lot or very much, based on the DLQI.37 Depending on the questionnaire used, the prevalence of sexual dysfunction due to psoriasis ranged from 35.5% to 71.3%.38 In an observational cohort study of 158 participants (n=79 psoriasis patients and n=79 controls), 34.2% of patients with psoriasis experienced erectile dysfunction compared to 17.7% of controls.39 Forty-two percent of psoriatic patients with genital involvement reported dyspareunia, 32% reported worsening of genital psoriasis after intercourse, and 43% reported decreased frequency of intercourse.40

Sexual Functioning Assessment

The Skindex-29, DLQI, and psoriasis disability index are available QOL tools that include one question evaluating difficulties with sexual function. The

Sexual Functioning Management

Better disease control leads to improved sexual function, as patients experience fewer feelings of shame, anxiety, and depression, as well as improvement of physical symptoms that can interfere with sexual functioning.38,43,44 Reducing friction, warmth, and moisture, as well as avoiding tight clothing, can help those with genital psoriasis. Patients are advised to reapply topical medications after sexual intercourse. Patients also can apply makeup to disguise psoriasis and help reduce feelings of self-consciousness that can impede sexual intimacy.18

Comment

The psychosocial burden of psoriasis penetrates many facets of patient lives. Psoriasis can invoke feelings of shame and embarrassment that are worsened by the public’s misconceptions about psoriasis, resulting in serious mental health issues that can cause even greater disability. Depression and anxiety are prevalent in patients with psoriasis. The characteristic symptoms of pain and pruritus along with psychiatric comorbidities can have an underestimated impact on daily activities, including employment, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function. Such dysfunctions have serious implications toward wages, professional advancement, social support, and overall QOL.

Dermatology providers play an important role in screening for these problems through validated questionnaires and identifying risks. Simple screening questions such as the PHQ-9 can be beneficial and feasible during dermatology visits. Screening for PsA can help patients avoid problems at work. Sexual dysfunction is a sensitive topic; however, providers can use a 1-question screen from valid questionnaires and inquire about the location of lesions as opportunities to address this issue.

Interventions lead to better disease control, which concurrently improves overall QOL. These interventions depend on both patient adherence and a physician’s commitment to finding an optimal treatment regimen for each individual. Medical management; coordinating care; developing treatment plans with psychiatry, rheumatology, and primary care providers; and psychological counseling and services may be necessary and beneficial (Table). Offering accessible resources such as the NPF website helps patients access information outside the clinic when it is not feasible to address all these concerns in a single visit. Psoriasis requires more than just medical management; it requires dermatology providers to use a multidisciplinary approach to address the psychosocial aspects of the disease.

Conclusion

The psychosocial burden of psoriasis is immense. Stigma, public misconception, mental health concerns, and occupational and interpersonal difficulty are the basis of disease burden. Providers play a vital role in assessing the effect psoriasis has on different areas of patients’ lives and providing appropriate interventions and resources to reduce disease burden.

- Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, et al. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:383-392.

- Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Wu J, et al. Quality of life and work productivity impairment among psoriasis patients: findings from the National Psoriasis Foundation survey data 2003-2011. PloS One. 2012;7:e52935.

- Halioua B, Sid-Mohand D, Roussel ME, et al. Extent of misconceptions, negative prejudices and discriminatory behaviour to psoriasis patients in France. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:650-654.

- Wolf P, Weger W, Legat F, et al. Quality of life and treatment goals in psoriasis from the patient perspective: results of an Austrian cross-sectional survey. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:981-990.

- Shah K, Mellars L, Changolkar A, et al. Real-world burden of comorbidities in US patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:287-292.e4.

- Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Herings RM, et al. Increased antidepressant drug exposure in psoriasis patients: a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2013;93:544-550.

- Dowlatshahi EA, Wakkee M, Arends LR, et al. The prevalence and odds of depressive symptoms and clinical depression in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1542-1551.

- Singh S, Taylor C, Kornmehl H, et al. Psoriasis and suicidality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:425.e2-440.e2.

- Lakshmy S, Balasundaram S, Sarkar S, et al. A cross-sectional study of prevalence and implications of depression and anxiety in psoriasis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37:434-440.

- Renzi C, Picardi A, Abeni D, et al. Association of dissatisfaction with care and psychiatric morbidity with poor treatment compliance. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:337-342.

- Kulkarni AS, Balkrishnan R, Camacho FT, et al. Medication and health care service utilization related to depressive symptoms in older adults with psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:661-666.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284-1292.

- Lamb RC, Matcham F, Turner MA, et al. Screening for anxiety and depression in people with psoriasis: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary referral setting. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1028-1034.

- Law M, Naughton MT, Dhar A, et al. Validation of two depression screening instruments in a sleep disorders clinic. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:683-688.

- Cuijpers P, Dekker J, Hollon SD, et al. Adding psychotherapy to pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depressive disorders in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1219-1229.

- National Psoriasis Foundation. Living with psoriatic arthritis. https://www.psoriasis.org/life-with-psoriatic-arthritis. Accessed September 23, 2018.

- Gaikwad R, Deshpande S, Raje S, et al. Evaluation of functional impairment in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:37-40.

- Claudepierre P, Lahfa M, Levy P, et al. The impact of psoriasis on professional life: PsoPRO, a French national survey [published online April 6, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.14986.

- Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, et al. Relationship between psoriasis severity, clinical symptoms, quality of life and work productivity among patients in the USA. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:514-521.

- Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. PharmacoEconomics. 1993;4:353-365.

- Korman NJ, Zhao Y, Pike J, et al. Increased severity of itching, pain, and scaling in psoriasis patients is associated with increased disease severity, reduced quality of life, and reduced work productivity. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21.

- Spelman L, Su JC, Fernandez-Penas P, et al. Frequency of undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis among psoriasis patients in Australian dermatology practice. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2184-2191.

- Tillett W, Shaddick G, Askari A, et al. Factors influencing work disability in psoriatic arthritis: first results from a large UK multicentre study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:157-162.

- Raychaudhuri SP, Wilken R, Sukhov AC, et al. Management of psoriatic arthritis: early diagnosis, monitoring of disease severity and cutting edge therapies. J Autoimmun. 2017;76:21-37.

- Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the manegement of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:499-510.

- Beroukhim K, Danesh M, Nguyen C, et al. A prospective, interventional assessment of the impact of ustekinumab treatment on psoriasis-related work productivity and activity impairment. J Dermatol Treat. 2016;27:552-555.

- Armstrong AW, Lynde CW, McBride SR, et al. Effect of ixekizumab treatment on work productivity for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: analysis of results from 3 randomized phase 3 clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:661-669.

- Kimball AB, Yu AP, Signorovitch J, et al. The effects of adalimumab treatment and psoriasis severity on self-reported work productivity and activity impairment for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:e67-76.

- Feldman SR, Malakouti M, Koo JY. Social impact of the burden of psoriasis: effects on patients and practice. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20.

- Reich A, Welz-Kubiak K, Rams Ł. Apprehension of the disease by patients suffering from psoriasis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:289-293.

- Gupta MA, Gupta AK, Watteel GN. Perceived deprivation of social touch in psoriasis is associated with greater psychologic morbidity: an index of the stigma experience in dermatologic disorders. Cutis. 1998;61:339-342.

- Basra MK, Finlay AY. The family impact of skin diseases: the Greater Patient concept. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:929-937.

- Eghlileb AM, Davies EE, Finlay AY. Psoriasis has a major secondary impact on the lives of family members and partners. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1245-1250.

- Janowski K, Steuden S, Pietrzak A, et al. Social support and adaptation to the disease in men and women with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2012;304:421-432.

- Sampogna F, Abeni D, Gieler U, et al. Impairment of sexual life in 3,485 dermatological outpatients from a multicentre study in 13 European countries. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:478-482.

- Sampogna F, Gisondi P, Tabolli S, et al. Impairment of sexual life in patients with psoriasis. Dermatology. 2007;214:144-150.

- Molina-Leyva A, Molina-Leyva I, Almodovar-Real A, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of erectile dysfunction in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and healthy population: a comparative study considering physical and psychological factors. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45:2047-2055.

- Ryan C, Sadlier M, De Vol E, et al. Genital psoriasis is associated with significant impairment in quality of life and sexual functioning. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:978-983.

- Labbate LA, Lare SB. Sexual dysfunction in male psychiatric outpatients: validity of the Massachusetts General Hospital Sexual Functioning Questionnaire. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:221-225.

- Molina-Leyva A, Almodovar-Real A, Ruiz-Carrascosa JC, et al. Distribution pattern of psoriasis affects sexual function in moderate to severe psoriasis: a prospective case series study. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2882-2889.

- Guenther L, Han C, Szapary P, et al. Impact of ustekinumab on health-related quality of life and sexual difficulties associated with psoriasis: results from two phase III clinical trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:851-857.

- Guenther L, Warren RB, Cather JC, et al. Impact of ixekizumab treatment on skin-related personal relationship difficulties in moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients: 12-week results from two Phase 3 trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1867-1875.

The psychosocial impact of psoriasis is a critical component of disease burden. Psoriatic patients have high rates of depression and anxiety, problems at work, and difficulties with interpersonal relationships and intimacy.1 A National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) survey from 2003 to 2011 reported that psoriasis affects overall emotional well-being in 88% of patients and enjoyment of life in 82% of patients.2

The reasons for psychosocial burden stem from public misconceptions and disease stigma. A survey of 1005 individuals (age range, 16–64 years) about their perceptions of psoriasis revealed that 16.5% believed that psoriasis is contagious and 6.8% believed that psoriasis is related to personal hygiene.3 Fifty percent practiced discriminatory behavior toward psoriatic patients, including reluctance to shake hands (28.8%) and engage in sexual relations/intercourse (44.1%). Sixty-five percent of psoriatic patients felt their appearance is unsightly, and 73% felt self-conscious about having psoriasis.2

The psychosocial burden exists despite medical treatment of the disease. In a cross-sectional study of 1184 psoriatic patients, 70.2% had impaired quality of life (QOL) as measured by the dermatology life quality index (DLQI), even after receiving a 4-week treatment for psoriasis.4 Medical treatment of psoriasis is not enough; providers need to assess overall QOL and provide treatment and resources for these patients in addition to symptomatic management.

There have been many studies on the psychosocial burden of psoriasis, but few have focused on a dermatology resident’s role in addressing this issue. This article will review psychosocial domains—psychiatric comorbidities and social functioning including occupational functioning, interpersonal relationships, and sexual functioning— and discuss a dermatology resident’s role in assessing and addressing each of these areas.

Methods

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE was conducted using the following terms: psoriasis, depression, anxiety, work productivity, sexual functioning, and interpersonal relationships. Selected articles covered prevalence, assessment, and management of each psychosocial domain.

Results

Psychiatric Comorbidities

Prevalence

A high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities exists in psoriatic patients. In a study of 469,097 patients with psoriasis, depression was the third most prevalent comorbidity (17.91%), following hyperlipidemia (45.64%) and hypertension (42.19%).5 In a 10-year longitudinal, population-based, prospective cohort study, antidepressant prescriptions were twice as frequent in psoriatic patients (17.8%) compared to control (7.9%)(P<.001).6 In a meta-analysis of 98 studies investigating psoriatic patients and psychiatric comorbidities, patients with psoriasis were 1.5 times more likely to experience depression (odds ratio [OR]: 1.57; 95% CI, 1.40-1.76) and use antidepressants (OR: 4.24; 95% CI, 1.53-11.76) compared to control.7 Patients with psoriasis were more likely to attempt suicide (OR: 1.32; 95% CI, 1.14-1.54) and complete suicide (OR: 1.20; 95% CI, 1.04-1.39) compared to people without psoriasis.8 A 1-year cross-sectional study of 90 psoriatic patients reported 78.7% were diagnosed with depression and 76.7% were diagnosed with anxiety. Seventy-two percent reported both anxiety and depression, correlating with worse QOL (χ2=26.7; P<.05).9

Assessment

Psychiatric comorbidities are assessed using clinical judgment and formal screening questionnaires in research studies. Signs of depression in patients with psoriasis can manifest as poor treatment adherence and recurrent flares of psoriasis.10,11 Psoriatic patients with psychiatric comorbidities were less likely to be adherent to treatment (risk ratio: 0.35; P<.003).10 The patient health questionnaire (PHQ) 9 and generalized anxiety disorder scale (GAD) 7 are validated and reliable questionnaires. The first 2 questions in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 screen for depression and anxiety, respectively.12-14 These 2-question screens are practical in a fast-paced dermatology outpatient setting. Systematic questionnaires specifically targeting mood disorders may be more beneficial than the widely used DLQI, which may not adequately capture mood disorders. Over the course of 10 months, 607 patients with psoriasis were asked to fill out the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and DLQI. Thirty-eight percent of patients with major depressive disorder had a DLQI score lower than 10, while 46% of patients with generalized anxiety disorder had a DLQI score lower than 10.15 Other questionnaires, including the hospital anxiety and depression scale and Beck depression inventory, are valid instruments with high sensitivity but are commonly used for research purposes and may not be clinically feasible.16

Management

Dermatologists should refer patients with depression and/or anxiety to psychiatry. Interventions include pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management. First-line therapy for depression and anxiety is a combination of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cognitive behavioral therapy.17 In addition, providers can direct patients to online resources such as the NPF website, where patients with psoriasis can access information about the signs and symptoms of mood disorders and contact the patient navigation center for further help.18

Social Functioning

Occupational Prevalence

The NPF found that 92% of patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis (PsA) surveyed between 2003 and 2011 cited their psoriasis as reason for unemployment.2 In a survey of 43 patients asked about social and occupational functioning using the social and occupational assessment scale, 62.5% of psoriatic patients reported distress at work and 51.1% reported decreased efficiency at work.19 A national online survey that was conducted in France and issued to patients with and without psoriasis assessed overall QOL and work productivity using the work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire for psoriasis (WPAI-PSO). Of 714 patients with psoriasis and PsA, the latter had a 57.6% decrease in work productivity over 7 days compared to 27.9% in controls (P<.05).20 Occupational impairment leads to lost wages and hinders advancement, further exacerbating the psychosocial burden of psoriasis.21

Occupational Assessment