User login

Review of Ethnoracial Representation in Clinical Trials (Phases 1 Through 4) of Atopic Dermatitis Therapies

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

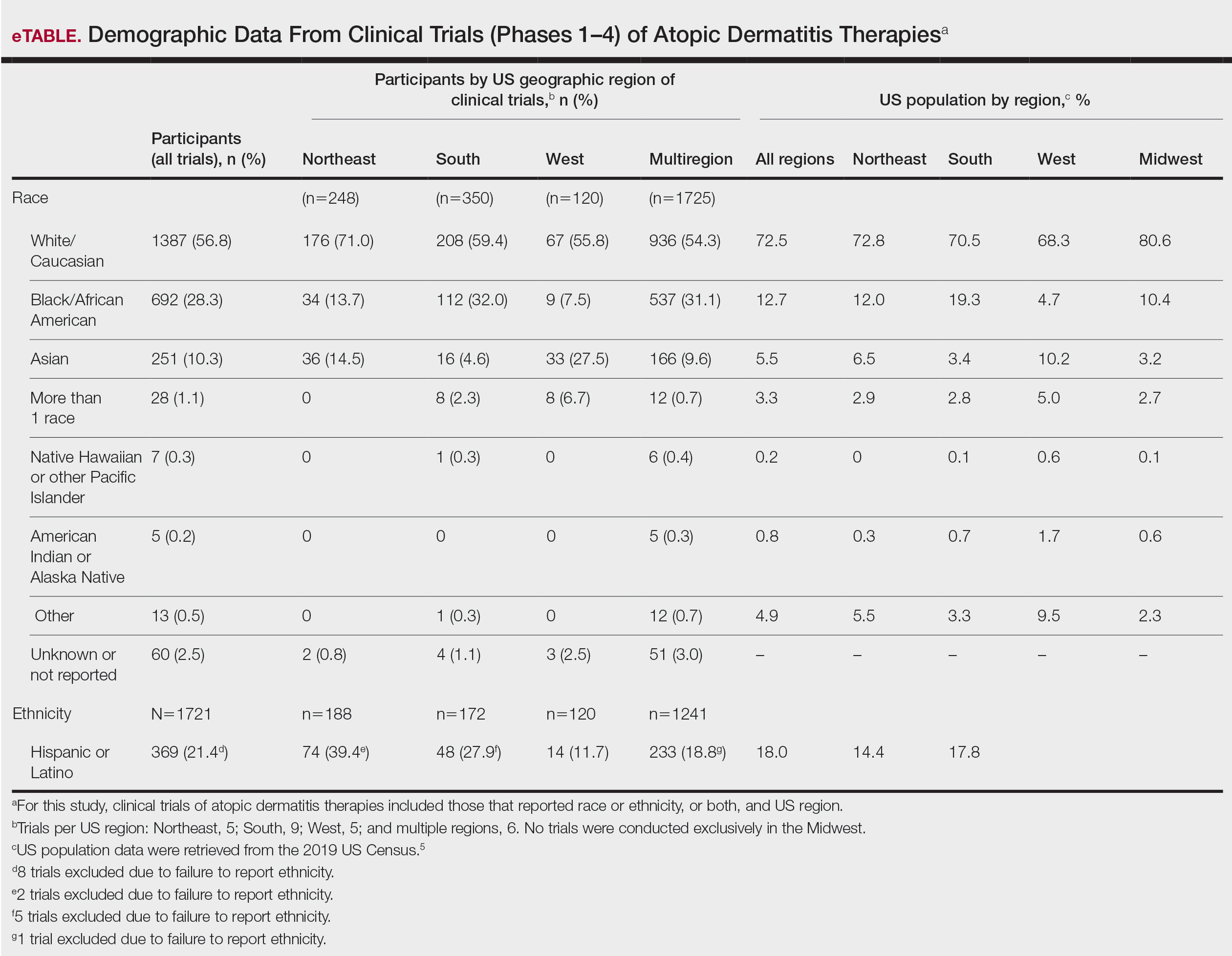

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects an estimated 7.2% of adults and 10.7% of children in the United States; however, AD might affect different races at a varying rate.1 Compared to their European American counterparts, Asian/Pacific Islanders and African Americans are 7 and 3 times more likely, respectively, to be given a diagnosis of AD.2

Despite being disproportionately affected by AD, minority groups might be underrepresented in clinical trials of AD treatments.3 One explanation for this imbalance might be that ethnoracial representation differs across regions in the United States, perhaps in regions where clinical trials are conducted. Price et al3 investigated racial representation in clinical trials of AD globally and found that patients of color are consistently underrepresented.

Research on racial representation in clinical trials within the United States—on national and regional scales—is lacking from the current AD literature. We conducted a study to compare racial and ethnic disparities in AD clinical trials across regions of the United States.

Using the ClinicalTrials.gov database (www.clinicaltrials.gov) of the National Library of Medicine, we identified clinical trials of AD treatments (encompassing phases 1 through 4) in the United States that were completed before March 14, 2021, with the earliest data from 2013. Search terms included atopic dermatitis, with an advanced search for interventional (clinical trials) and with results.

In total, 95 completed clinical trials were identified, of which 26 (27.4%) reported ethnoracial demographic data. One trial was excluded due to misrepresentation regarding the classification of individuals who identified as more than 1 racial category. Clinical trials for systemic treatments (7 [28%]) and topical treatments (18 [72%]) were identified.

All ethnoracial data were self-reported by trial participants based on US Food and Drug Administration guidelines for racial and ethnic categorization.4 Trial participants who identified ethnically as Hispanic or Latino might have been a part of any racial group. Only 7 of the 25 included clinical trials (28%) provided ethnic demographic data (Hispanic [Latino] or non-Hispanic); 72% of trials failed to report ethnicity. Ethnic data included in our analysis came from only the 7 clinical trials that included these data. International multicenter trials that included a US site were excluded.

Ultimately, the number of trials included in our analysis was 25, comprised of 2443 participants. Data were further organized by US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West, and multiregion trials [ie, conducted in ≥2 regions]). No AD clinical trials were conducted solely in the Midwest; it was only included within multiregion trials.

Compared to their representation in the 2019 US Census, most minority groups were overrepresented in clinical trials, while White individuals were underrepresented (eTable). The percentages of our findings on representation for race are as follows (US Census data are listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- White: 56.8% (72.5%)

- Black/African American: 28.3% (12.7%)

- Asian: 10.3% (5.5%)

- Multiracial: 1.1% (3.3%)

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander: 0.3% (0.2%)

- American Indian or Alaska Native: 0.2% (0.8%)

- Other: 0.5% (4.9%).

Our findings on representation for ethnicity are as follows (US Census data is listed in parentheses for comparison5):

- Hispanic or Latino: 21.4% (18.0%)

Although representation of Black/African American and Asian participants in clinical trials was higher than their representation in US Census data and representation of White participants was lower in clinical trials than their representation in census data, equal representation among all racial and ethnic groups is still lacking. A potential explanation for this finding might be that requirements for trial inclusion selected for more minority patients, given the propensity for greater severity of AD among those racial groups.2 Another explanation might be that efforts to include minority patients in clinical trials are improving.

There were great differences in ethnoracial representation in clinical trials when regions within the United States were compared. Based on census population data by region, the West had the highest percentage (29.9%) of Hispanic or Latino residents; however, this group represented only 11.7% of participants in AD clinical trials in that region.5

The South had the greatest number of participants in AD clinical trials of any region, which was consistent with research findings on an association between severity of AD and heat.6 With a warmer climate correlating with an increased incidence of AD, it is possible that more people are willing to participate in clinical trials in the South.

The Midwest was the only region in which region-specific clinical trials were not conducted. Recent studies have shown that individuals with AD who live in the Midwest have comparatively less access to health care associated with AD treatment and are more likely to visit an emergency department because of AD than individuals in any other US region.7 This discrepancy highlights the need for increased access to resources and clinical trials focused on the treatment of AD in the Midwest.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act established a federal legislative mandate to encourage inclusion of women and people of color in clinical trials.8 During the last 2 decades, there have been improvements in ethnoracial reporting. A 2020 global study found that 81.1% of randomized controlled trials (phases 2 and 3) of AD treatments reported ethnoracial data.3

Equal representation in clinical trials allows for further investigation of the connection between race, AD severity, and treatment efficacy. Clinical trials need to have equal representation of ethnoracial categories across all regions of the United States. If one group is notably overrepresented, ethnoracial associations related to the treatment of AD might go undetected.9 Similarly, if representation is unequal, relationships of treatment efficacy within ethnoracial groups also might go undetected. None of the clinical trials that we analyzed investigated treatment efficacy by race, suggesting that there is a need for future research in this area.

It also is important to note that broad classifications of race and ethnicity are limiting and therefore overlook differences within ethnoracial categories. Although representation of minority patients in clinical trials for AD treatments is improving, we conclude that there remains a need for greater and equal representation of minority groups in clinical trials of AD treatments in the United States.

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

- Avena-Woods C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(8 suppl):S115-S123.

- Kaufman BP, Guttman‐Yassky E, Alexis AF. Atopic dermatitis in diverse racial and ethnic groups—variations in epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:340-357. doi:10.1111/exd.13514

- Price KN, Krase JM, Loh TY, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in global atopic dermatitis clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:378-380. doi:10.1111/bjd.18938

- Collection of race and ethnicity data in clinical trials: guidance for industry and Food and Drug Administration staff. US Food and Drug Administration; October 26, 2016. Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/75453/download

- United States Census Bureau. 2019 Population estimates by age, sex, race and Hispanic origin. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/population-estimates-detailed.html

- Fleischer AB Jr. Atopic dermatitis: the relationship to temperature and seasonality in the United States. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:465-471. doi:10.1111/ijd.14289

- Wu KK, Nguyen KB, Sandhu JK, et al. Does location matter? geographic variations in healthcare resource use for atopic dermatitis in the United States. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:314-320. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1656796

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, 42 USC 201 (1993). Accessed February 20, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-107/pdf/STATUTE-107-Pg122.pdf

- Hirano SA, Murray SB, Harvey VM. Reporting, representation, and subgroup analysis of race and ethnicity in published clinical trials of atopic dermatitis in the United States between 2000 and 2009. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:749-755. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01797.x

Practice Points

- Although minority groups are disproportionally affected by atopic dermatitis (AD), they may be underrepresented in clinical trials for AD in the United States.

- Equal representation among ethnoracial groups in clinical trials is important to allow for a more thorough investigation of the efficacy of treatments for AD.