User login

Multiethnic Training in Residency: A Survey of Dermatology Residents

Dermatologic treatment of patients with skin of color offers specific challenges. Studies have reported structural, morphologic, and physiologic distinctions among different ethnic groups,1 which may account for distinct clinical presentations of skin disease seen in patients with skin of color. Patients with skin of color are at increased risk for specific dermatologic conditions, such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloid development, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.2,3 Furthermore, although skin cancer is less prevalent in patients with skin of color, it often presents at a more advanced stage and with a worse prognosis compared to white patients.4

Prior studies have demonstrated the need for increased exposure, education, and training in diseases pertaining to skin of color in US dermatology residency programs.6-8 The aim of this study was to assess if dermatologists in-training feel that their residency curriculum sufficiently educates them on the needs of patients with skin of color.

Methods

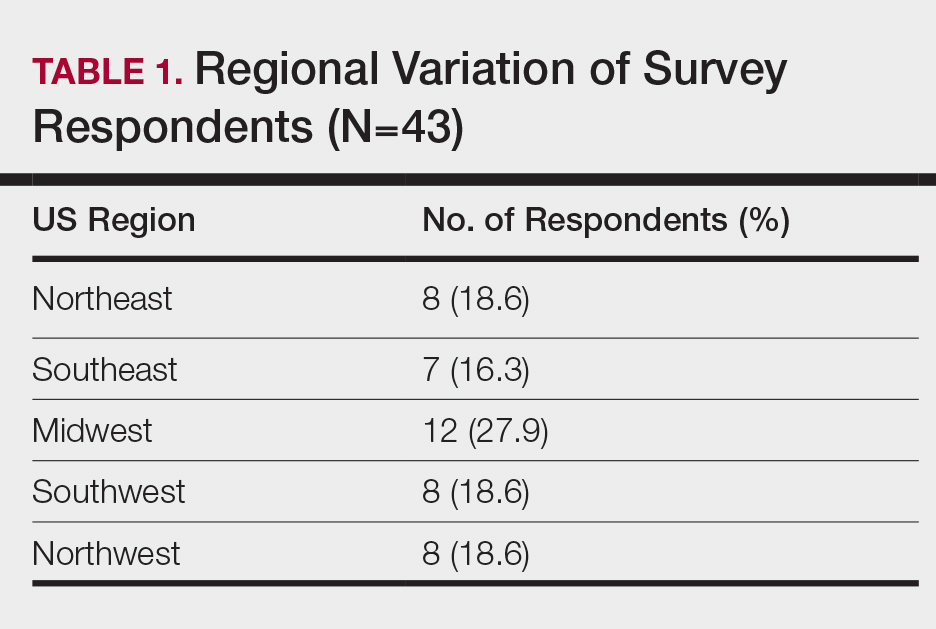

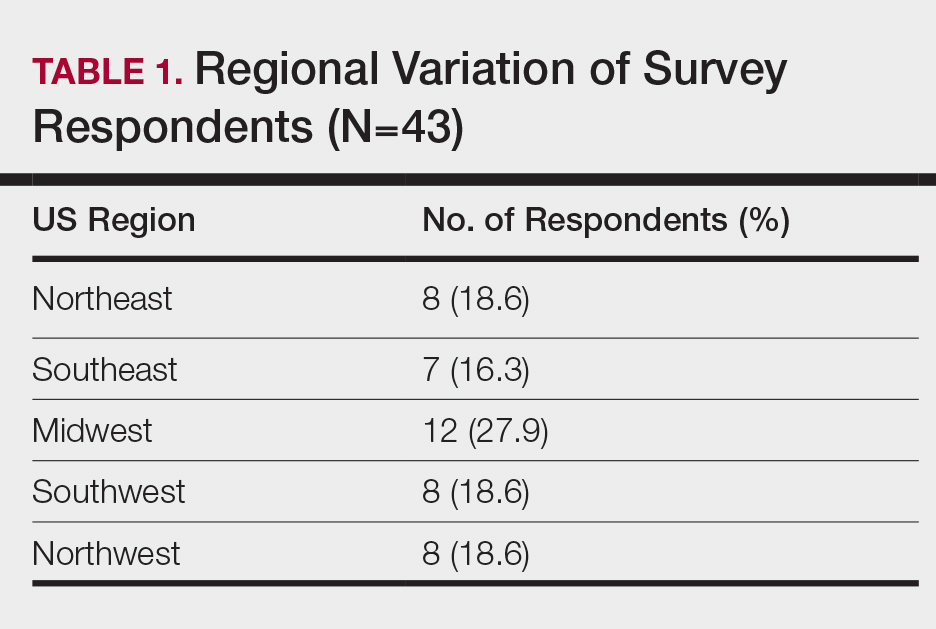

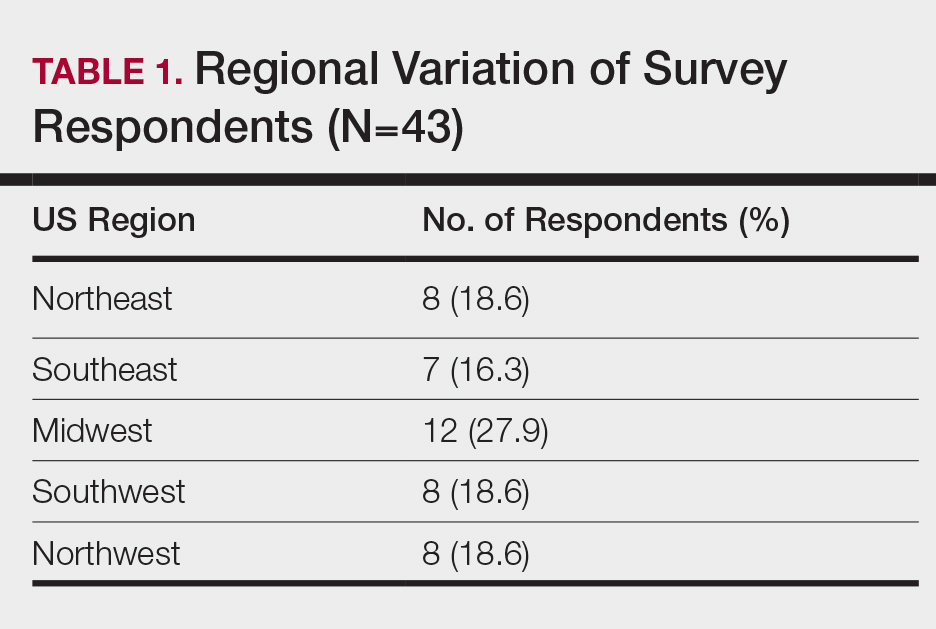

A 10-question anonymous survey was emailed to 109 dermatology residency programs to evaluate the attitudes of dermatology residents about their exposure to patients with skin of color and their skin-of-color curriculum. The study included individuals 18 years or older who were current residents in a dermatology program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Results

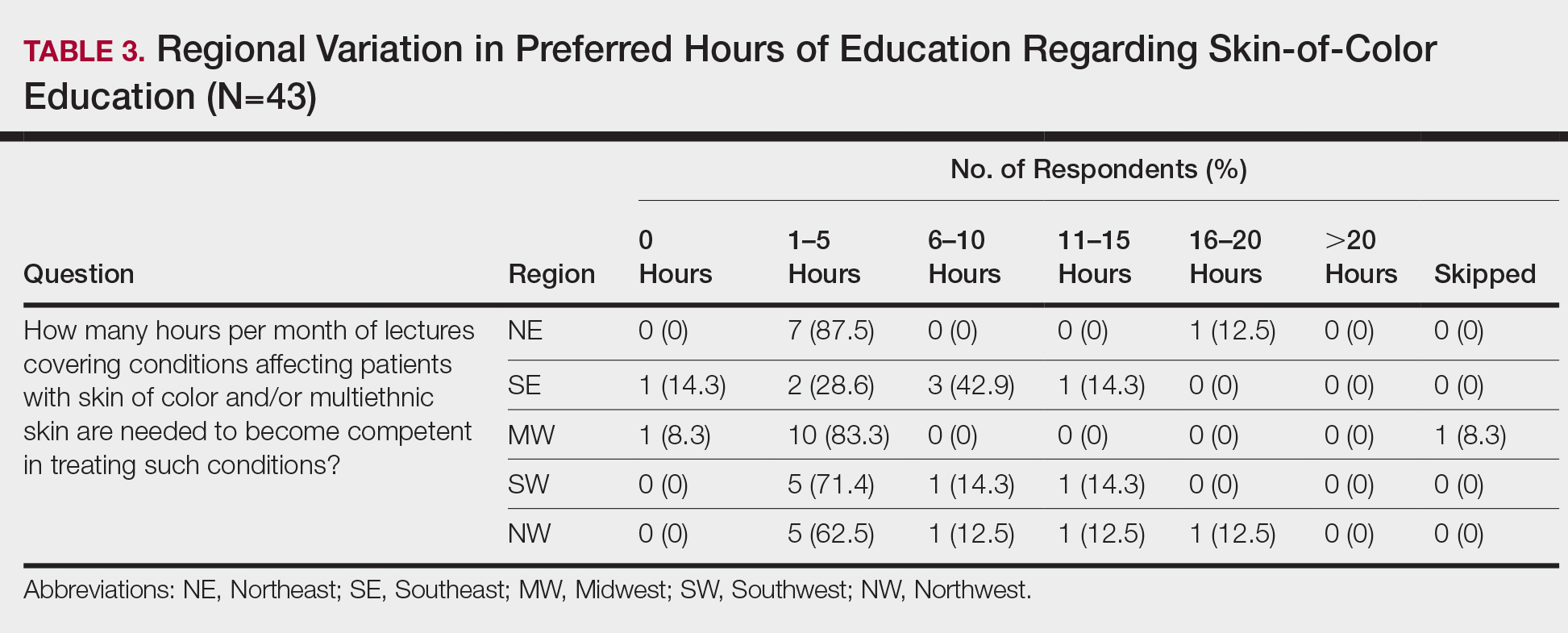

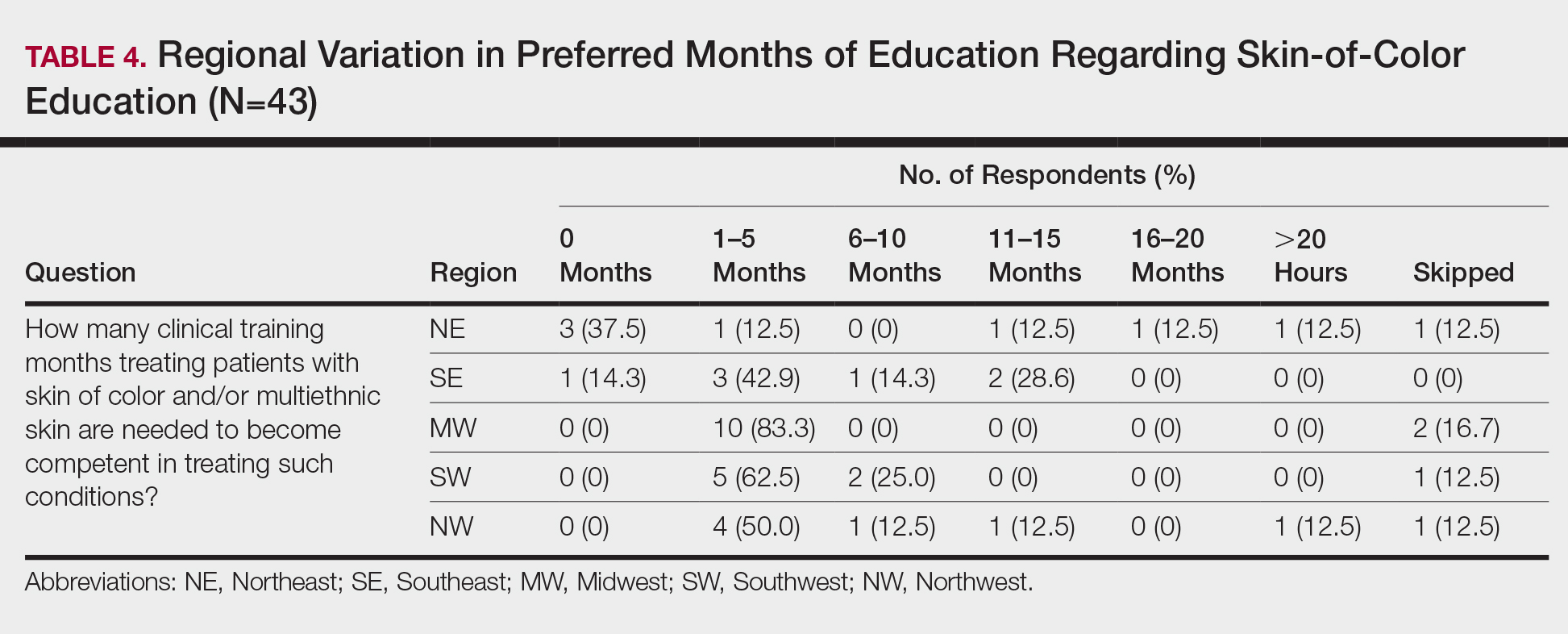

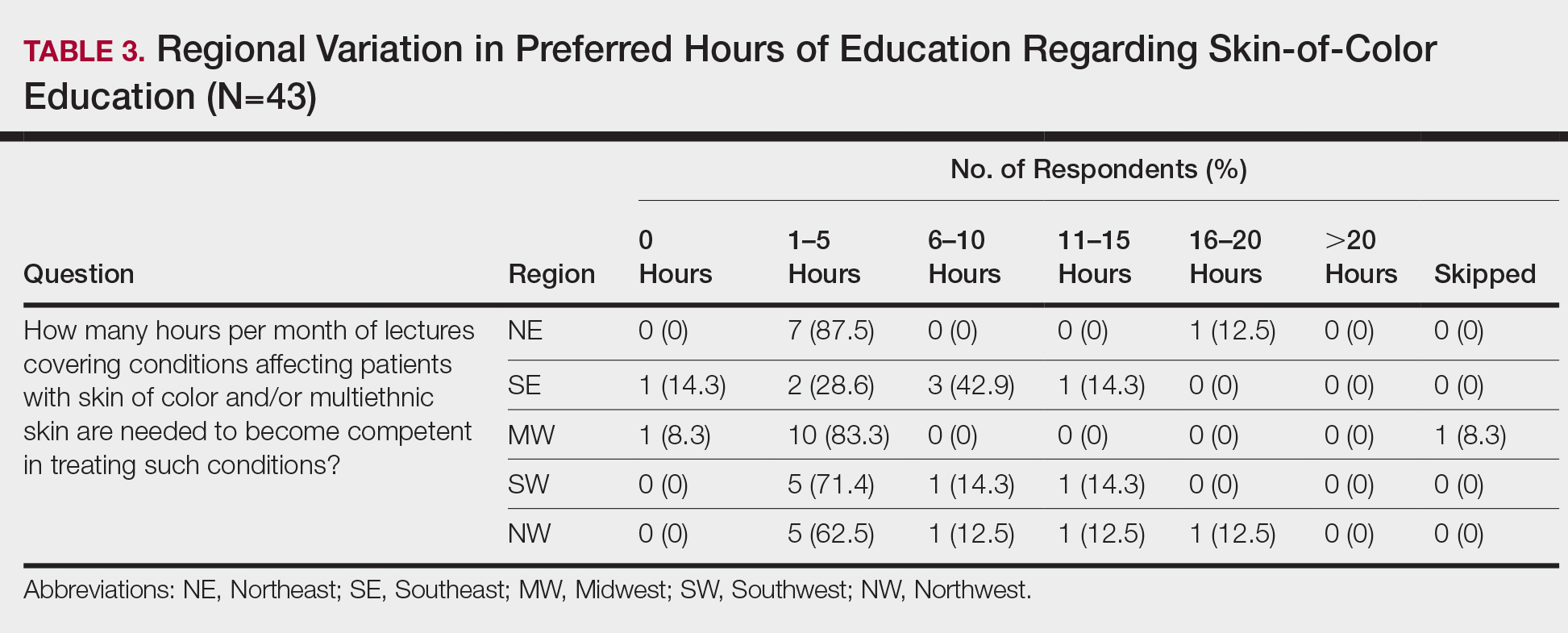

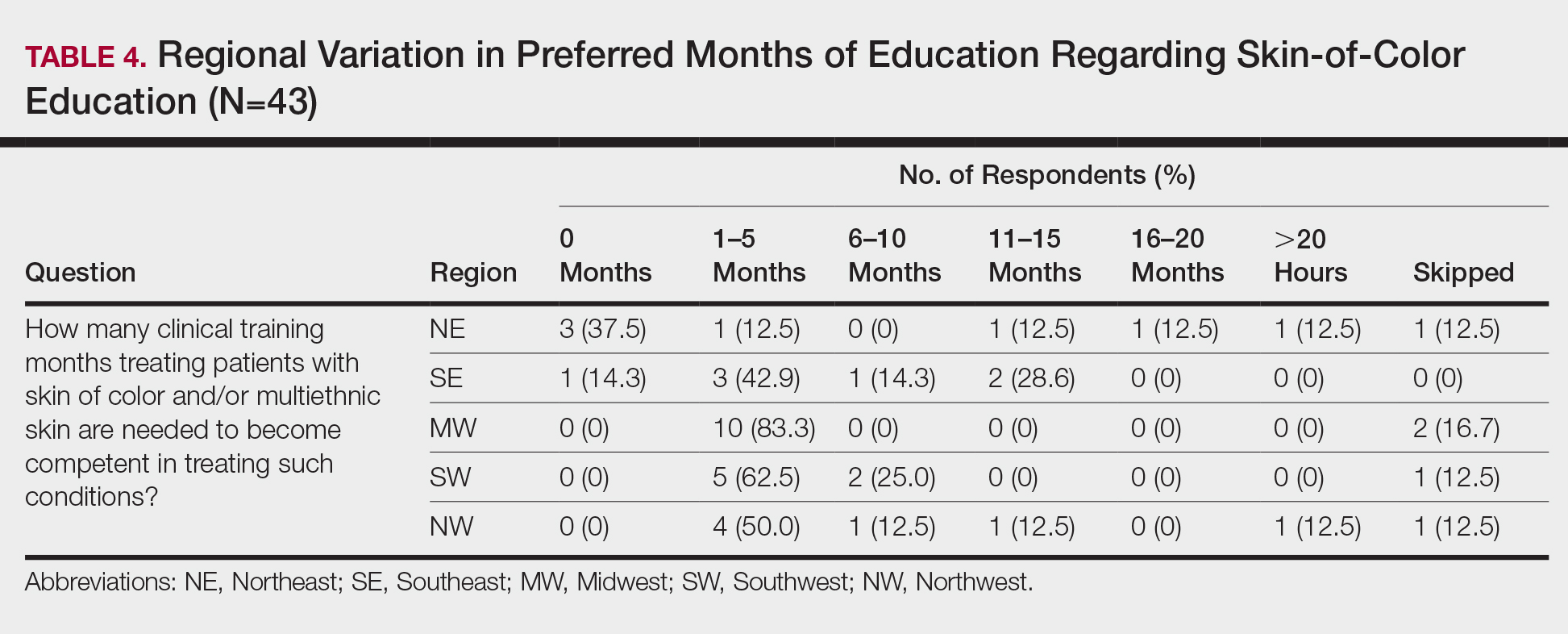

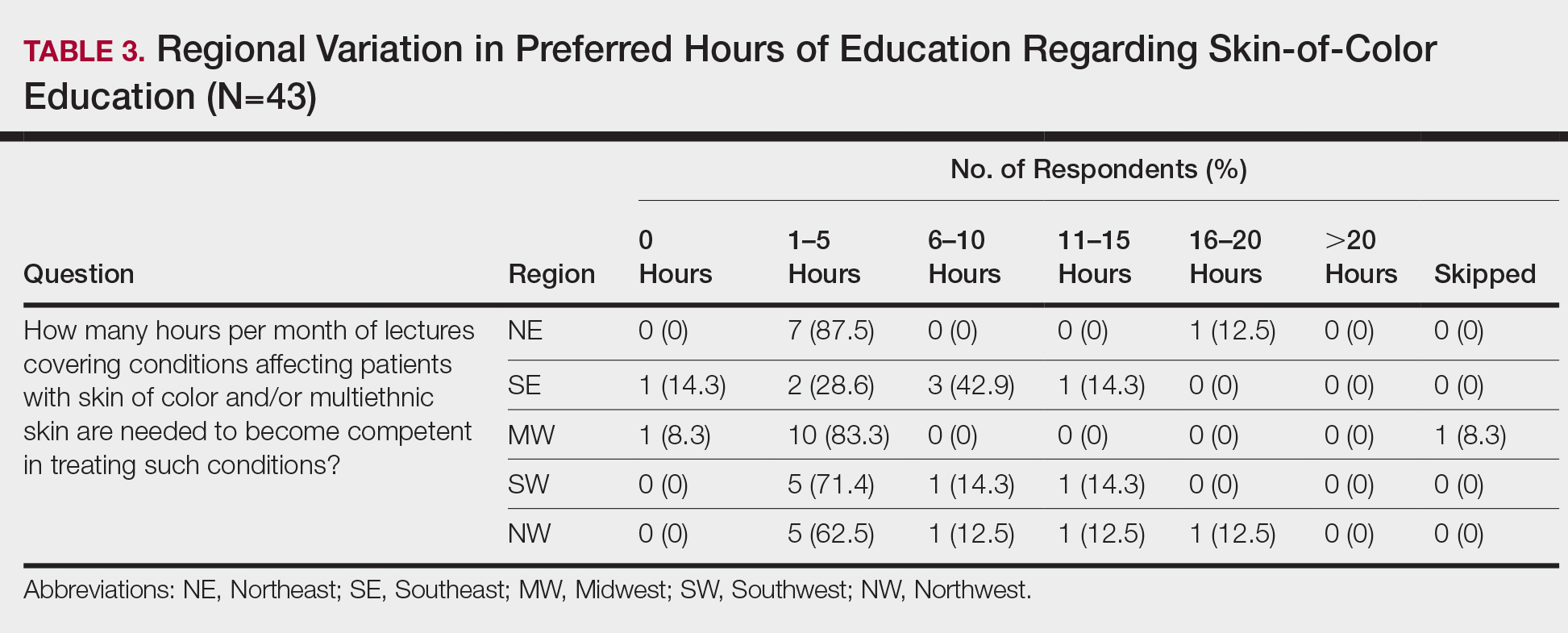

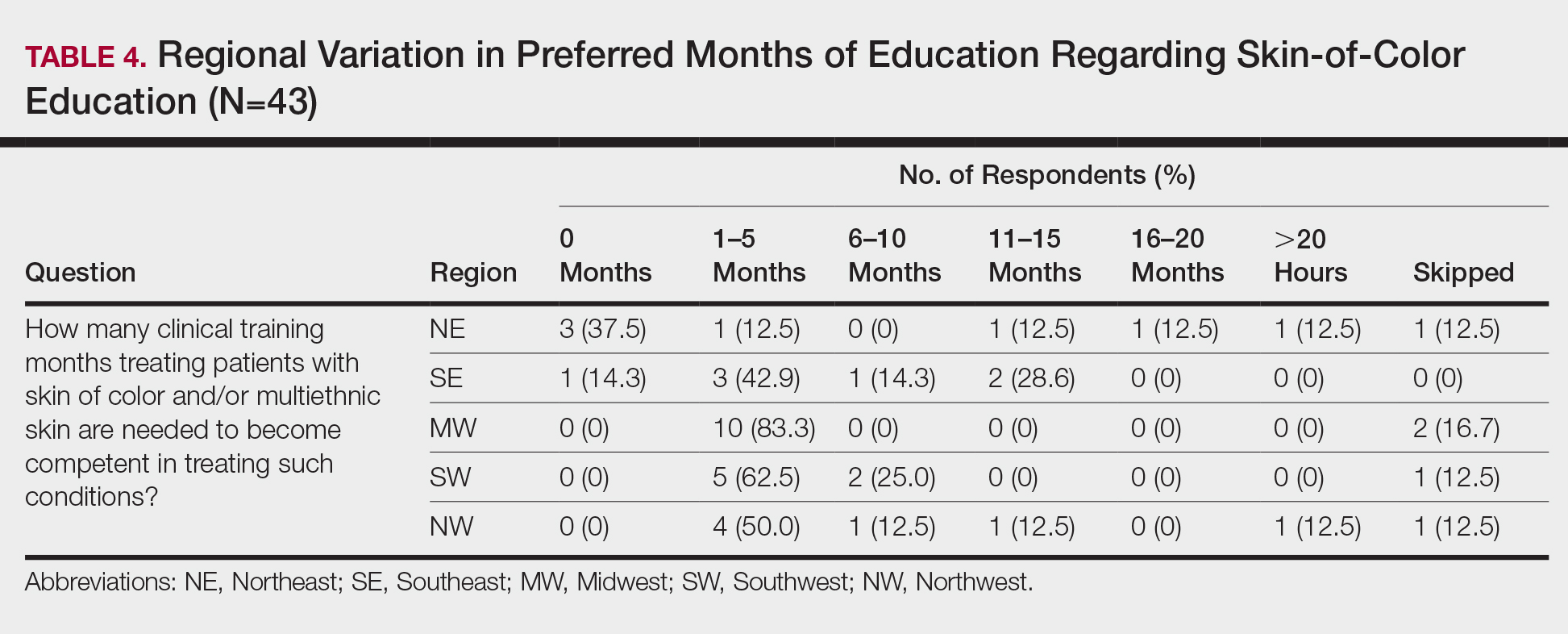

When asked the number of hours of lecture per month necessary to gain competence in conditions affecting patients with skin of color, 67% agreed that 1 to 5 hours was sufficient (Table 3). There were significant differences in the responses between the NE and SE (P=.024) and the SE and MW (P=.007). Of all respondents, 53% reported 1 to 5 months of clinical training are needed to gain competence in treating conditions affecting patients with skin of color, with significant differences in responses between the NE and MW (P<.001), the NE and SW (P=.019), and the SE and MW (P=.015)(Table 4).

Comment

Responses varied by practicing region

Although interactive lectures and textbook readings are important for obtaining a foundational understanding of dermatologic disease, they cannot substitute for clinical interactions and hands-on experience treating patients with skin of color.9 Not only do clinical interactions encourage independent reading and the study of encountered diagnoses, but intercommunication with patients may have a more profound and lasting impact on residents’ education.

Different regions of the United States have varying distributions of patients with skin of color, and dermatology residency program training reflects these disparities.6 In areas of less diversity, dermatology residents examine, diagnose, and treat substantially fewer patients with skin of color. The desire for more diverse training supports the prior findings of Nijhawan et al6 and is reflected in the responses we received in our study, whereby residents from the less ethnically diversified regions of the MW and NW were more likely to agree that clinics and rotations were necessary for training in preparation to sufficiently address the needs of patients with skin of color.

One way to compensate for the lack of ethnic diversity encountered in areas such as the MW and NW would be to develop educational programs featuring experts on skin of color.6 These specialists would not only train dermatology residents in areas of the country currently lacking ethnic diversity but also expand the expertise for treating patients with skin of color. Additionally, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and externships devoted solely to treating patients with skin of color could be encouraged for residency training.6 Finally, community outreach through volunteer clinics may provide residents exposure to patients with skin of color seeking dermatologic care.10

This study was limited by the small number of respondents, but we were able to extract important trends and data from the collected responses. It is possible that respondents felt strongly about topics involving patients with skin of color, and the results were skewed to reflect individual bias. Additional limitations included not asking respondents for program names and population density (eg, urban, suburban, rural). Future studies should be directed toward analyzing how the diversity of the local population influences training in patients with skin of color, comparing program directors’ perceptions with residents’ perceptions on training in skin of color, and assessing patient perception of residents’ training in skin of color.

Conclusion

In the last decade it has become increasingly apparent that the US population is diversifying and that patients with skin of color will comprise a substantial proportion of the future population,8,11 which emphasizes the need for dermatology residency programs to ensure that residents receive adequate training and exposure to patients with skin of color as well as the distinct skin diseases seen more commonly in these populations.12

- Luther N, Darvin ME, Sterry W, et al. Ethnic differences in skin physiology, hair follicle morphology and follicular penetration. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:182-191.

- Shokeen D. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2016;97:E9-E11.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2017;3:S21-S37.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM; US Census Bureau. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Ernst H, Colthorpe K. The efficacy of interactive lecturing for students with diverse science backgrounds. Adv Physiol Educ. 2007;31:41-44.

- Allday E. UCSF opens ‘skin of color’ dermatology clinic to address disparity in care. San Francisco Chronicle. March 20, 2019. https://www.sfchronicle.com/health/article/UCSF-opens-skin-of-color-dermatology-clinic-13704387.php. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Enos CW, Harvey VM. From bench to bedside: the Hampton University Skin of Color Research Institute 2015 Skin of Color Symposium. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S29-S30.

Dermatologic treatment of patients with skin of color offers specific challenges. Studies have reported structural, morphologic, and physiologic distinctions among different ethnic groups,1 which may account for distinct clinical presentations of skin disease seen in patients with skin of color. Patients with skin of color are at increased risk for specific dermatologic conditions, such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloid development, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.2,3 Furthermore, although skin cancer is less prevalent in patients with skin of color, it often presents at a more advanced stage and with a worse prognosis compared to white patients.4

Prior studies have demonstrated the need for increased exposure, education, and training in diseases pertaining to skin of color in US dermatology residency programs.6-8 The aim of this study was to assess if dermatologists in-training feel that their residency curriculum sufficiently educates them on the needs of patients with skin of color.

Methods

A 10-question anonymous survey was emailed to 109 dermatology residency programs to evaluate the attitudes of dermatology residents about their exposure to patients with skin of color and their skin-of-color curriculum. The study included individuals 18 years or older who were current residents in a dermatology program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Results

When asked the number of hours of lecture per month necessary to gain competence in conditions affecting patients with skin of color, 67% agreed that 1 to 5 hours was sufficient (Table 3). There were significant differences in the responses between the NE and SE (P=.024) and the SE and MW (P=.007). Of all respondents, 53% reported 1 to 5 months of clinical training are needed to gain competence in treating conditions affecting patients with skin of color, with significant differences in responses between the NE and MW (P<.001), the NE and SW (P=.019), and the SE and MW (P=.015)(Table 4).

Comment

Responses varied by practicing region

Although interactive lectures and textbook readings are important for obtaining a foundational understanding of dermatologic disease, they cannot substitute for clinical interactions and hands-on experience treating patients with skin of color.9 Not only do clinical interactions encourage independent reading and the study of encountered diagnoses, but intercommunication with patients may have a more profound and lasting impact on residents’ education.

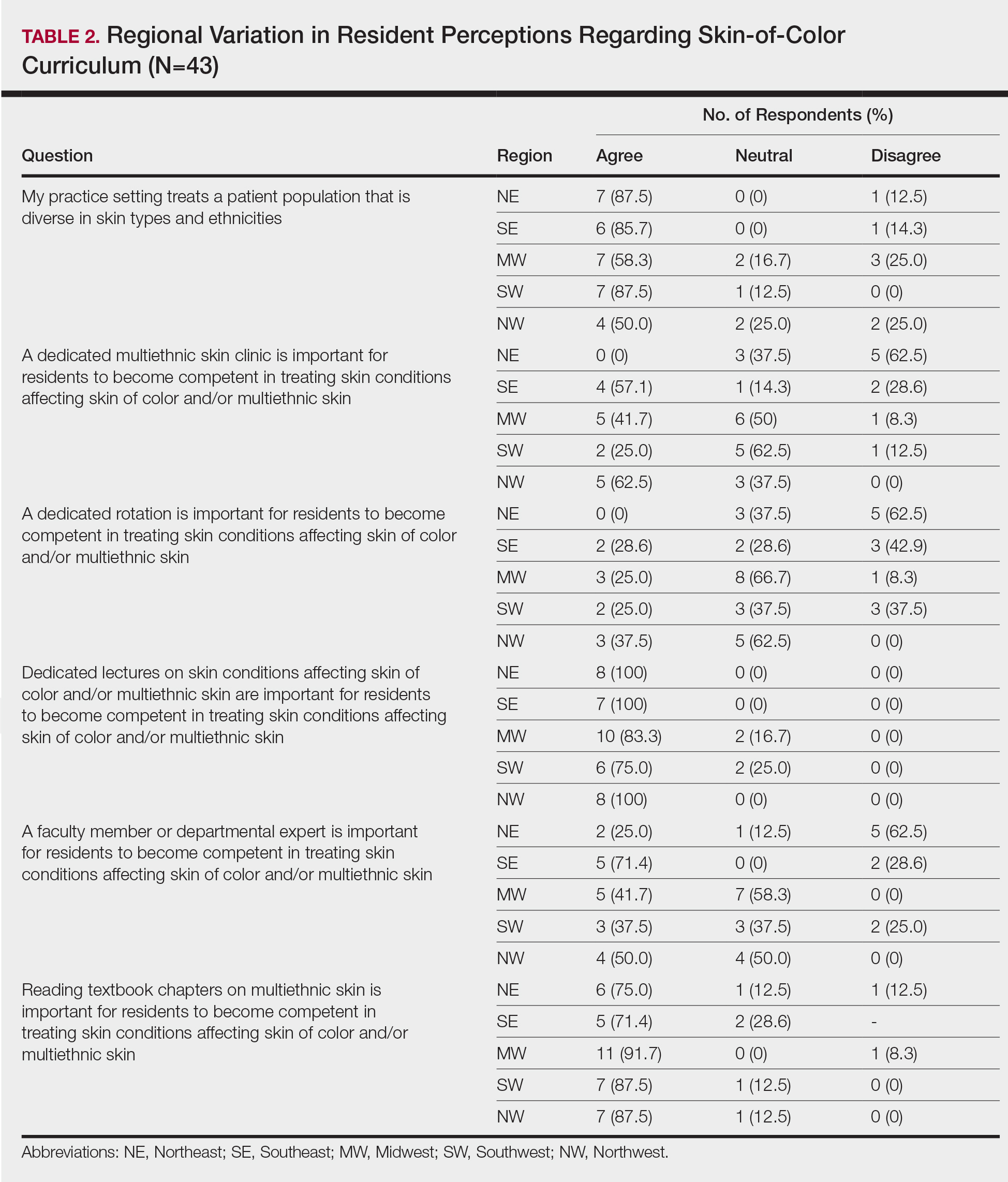

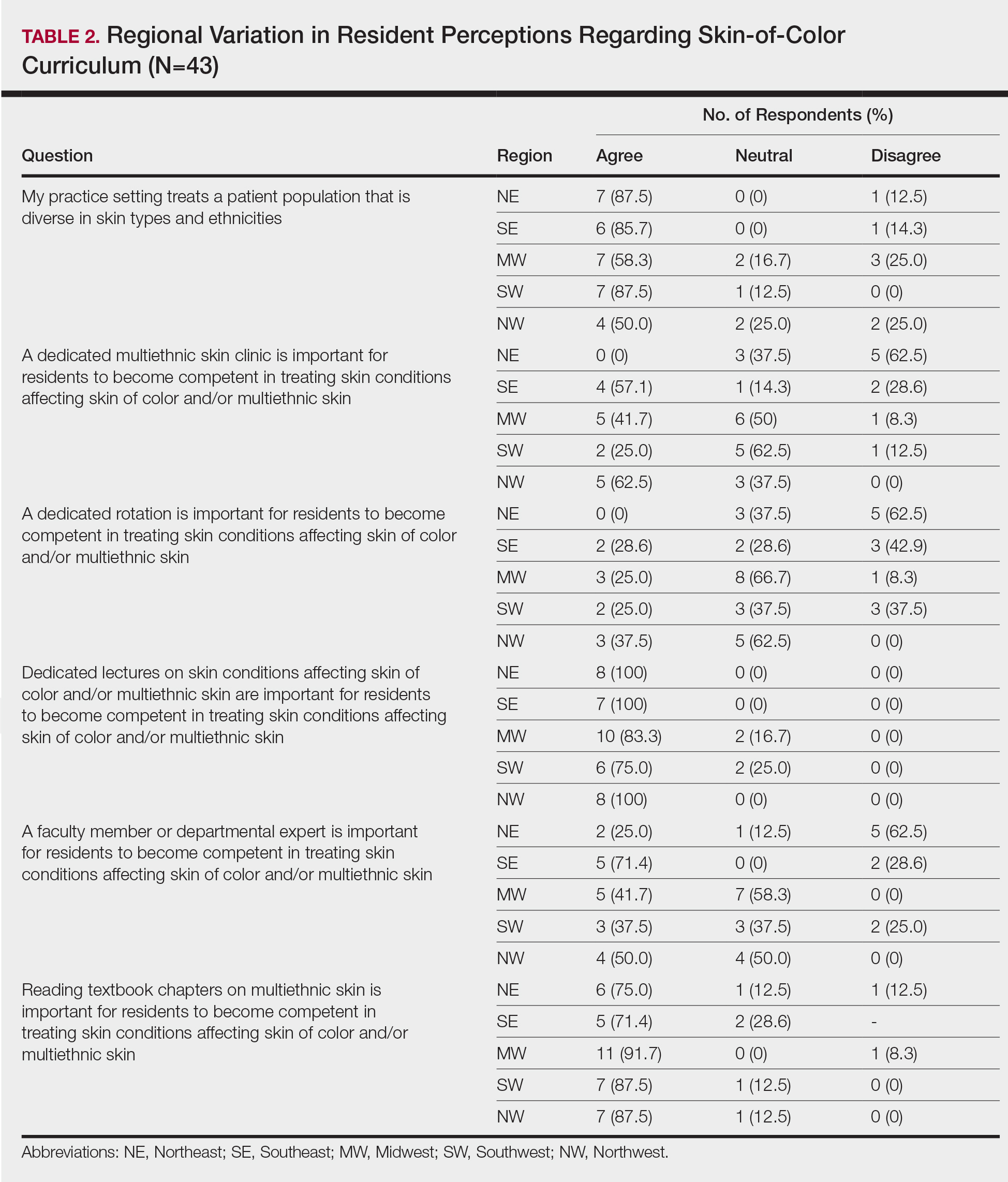

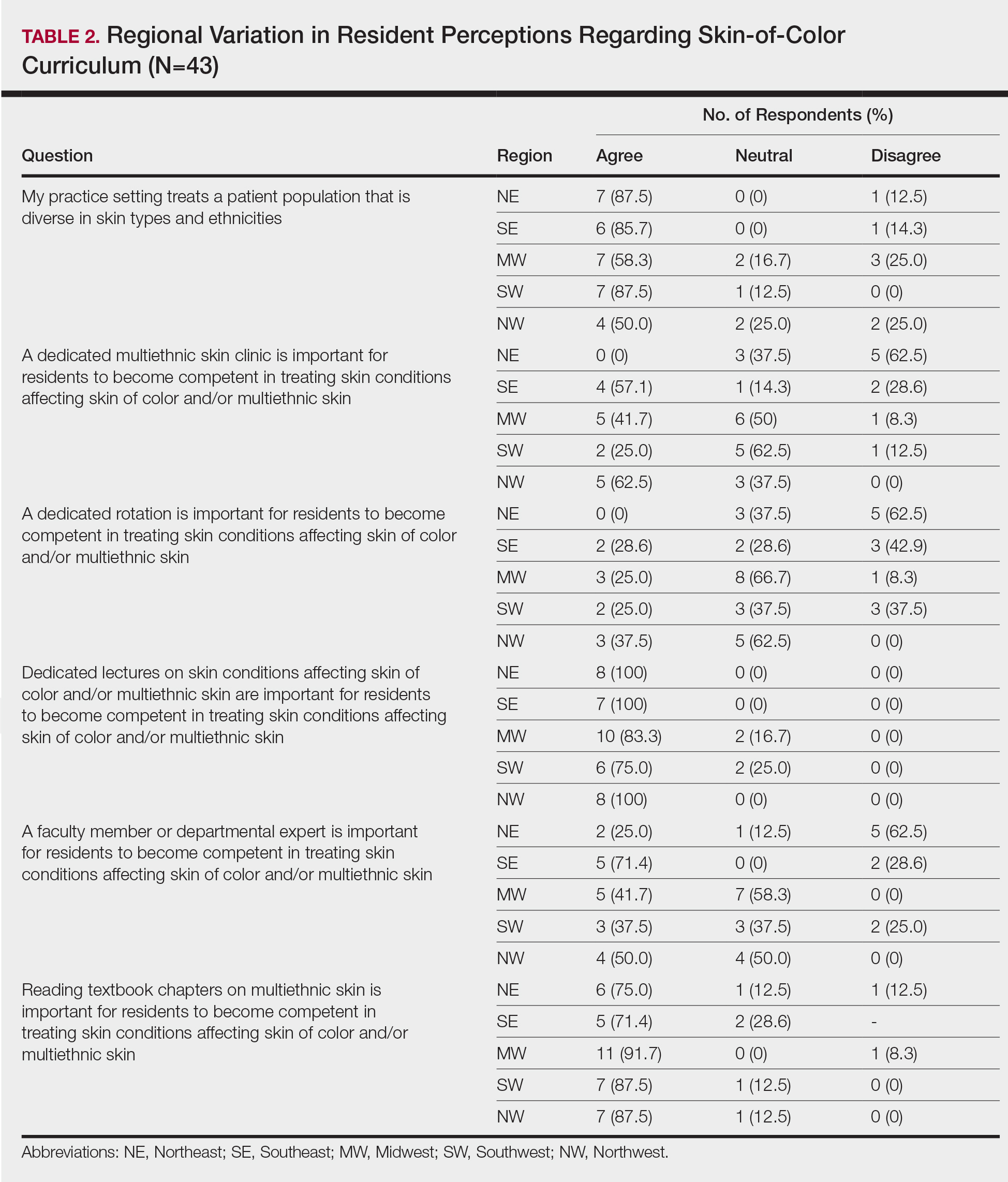

Different regions of the United States have varying distributions of patients with skin of color, and dermatology residency program training reflects these disparities.6 In areas of less diversity, dermatology residents examine, diagnose, and treat substantially fewer patients with skin of color. The desire for more diverse training supports the prior findings of Nijhawan et al6 and is reflected in the responses we received in our study, whereby residents from the less ethnically diversified regions of the MW and NW were more likely to agree that clinics and rotations were necessary for training in preparation to sufficiently address the needs of patients with skin of color.

One way to compensate for the lack of ethnic diversity encountered in areas such as the MW and NW would be to develop educational programs featuring experts on skin of color.6 These specialists would not only train dermatology residents in areas of the country currently lacking ethnic diversity but also expand the expertise for treating patients with skin of color. Additionally, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and externships devoted solely to treating patients with skin of color could be encouraged for residency training.6 Finally, community outreach through volunteer clinics may provide residents exposure to patients with skin of color seeking dermatologic care.10

This study was limited by the small number of respondents, but we were able to extract important trends and data from the collected responses. It is possible that respondents felt strongly about topics involving patients with skin of color, and the results were skewed to reflect individual bias. Additional limitations included not asking respondents for program names and population density (eg, urban, suburban, rural). Future studies should be directed toward analyzing how the diversity of the local population influences training in patients with skin of color, comparing program directors’ perceptions with residents’ perceptions on training in skin of color, and assessing patient perception of residents’ training in skin of color.

Conclusion

In the last decade it has become increasingly apparent that the US population is diversifying and that patients with skin of color will comprise a substantial proportion of the future population,8,11 which emphasizes the need for dermatology residency programs to ensure that residents receive adequate training and exposure to patients with skin of color as well as the distinct skin diseases seen more commonly in these populations.12

Dermatologic treatment of patients with skin of color offers specific challenges. Studies have reported structural, morphologic, and physiologic distinctions among different ethnic groups,1 which may account for distinct clinical presentations of skin disease seen in patients with skin of color. Patients with skin of color are at increased risk for specific dermatologic conditions, such as postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, keloid development, and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia.2,3 Furthermore, although skin cancer is less prevalent in patients with skin of color, it often presents at a more advanced stage and with a worse prognosis compared to white patients.4

Prior studies have demonstrated the need for increased exposure, education, and training in diseases pertaining to skin of color in US dermatology residency programs.6-8 The aim of this study was to assess if dermatologists in-training feel that their residency curriculum sufficiently educates them on the needs of patients with skin of color.

Methods

A 10-question anonymous survey was emailed to 109 dermatology residency programs to evaluate the attitudes of dermatology residents about their exposure to patients with skin of color and their skin-of-color curriculum. The study included individuals 18 years or older who were current residents in a dermatology program accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Results

When asked the number of hours of lecture per month necessary to gain competence in conditions affecting patients with skin of color, 67% agreed that 1 to 5 hours was sufficient (Table 3). There were significant differences in the responses between the NE and SE (P=.024) and the SE and MW (P=.007). Of all respondents, 53% reported 1 to 5 months of clinical training are needed to gain competence in treating conditions affecting patients with skin of color, with significant differences in responses between the NE and MW (P<.001), the NE and SW (P=.019), and the SE and MW (P=.015)(Table 4).

Comment

Responses varied by practicing region

Although interactive lectures and textbook readings are important for obtaining a foundational understanding of dermatologic disease, they cannot substitute for clinical interactions and hands-on experience treating patients with skin of color.9 Not only do clinical interactions encourage independent reading and the study of encountered diagnoses, but intercommunication with patients may have a more profound and lasting impact on residents’ education.

Different regions of the United States have varying distributions of patients with skin of color, and dermatology residency program training reflects these disparities.6 In areas of less diversity, dermatology residents examine, diagnose, and treat substantially fewer patients with skin of color. The desire for more diverse training supports the prior findings of Nijhawan et al6 and is reflected in the responses we received in our study, whereby residents from the less ethnically diversified regions of the MW and NW were more likely to agree that clinics and rotations were necessary for training in preparation to sufficiently address the needs of patients with skin of color.

One way to compensate for the lack of ethnic diversity encountered in areas such as the MW and NW would be to develop educational programs featuring experts on skin of color.6 These specialists would not only train dermatology residents in areas of the country currently lacking ethnic diversity but also expand the expertise for treating patients with skin of color. Additionally, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and externships devoted solely to treating patients with skin of color could be encouraged for residency training.6 Finally, community outreach through volunteer clinics may provide residents exposure to patients with skin of color seeking dermatologic care.10

This study was limited by the small number of respondents, but we were able to extract important trends and data from the collected responses. It is possible that respondents felt strongly about topics involving patients with skin of color, and the results were skewed to reflect individual bias. Additional limitations included not asking respondents for program names and population density (eg, urban, suburban, rural). Future studies should be directed toward analyzing how the diversity of the local population influences training in patients with skin of color, comparing program directors’ perceptions with residents’ perceptions on training in skin of color, and assessing patient perception of residents’ training in skin of color.

Conclusion

In the last decade it has become increasingly apparent that the US population is diversifying and that patients with skin of color will comprise a substantial proportion of the future population,8,11 which emphasizes the need for dermatology residency programs to ensure that residents receive adequate training and exposure to patients with skin of color as well as the distinct skin diseases seen more commonly in these populations.12

- Luther N, Darvin ME, Sterry W, et al. Ethnic differences in skin physiology, hair follicle morphology and follicular penetration. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:182-191.

- Shokeen D. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2016;97:E9-E11.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2017;3:S21-S37.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM; US Census Bureau. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Ernst H, Colthorpe K. The efficacy of interactive lecturing for students with diverse science backgrounds. Adv Physiol Educ. 2007;31:41-44.

- Allday E. UCSF opens ‘skin of color’ dermatology clinic to address disparity in care. San Francisco Chronicle. March 20, 2019. https://www.sfchronicle.com/health/article/UCSF-opens-skin-of-color-dermatology-clinic-13704387.php. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Enos CW, Harvey VM. From bench to bedside: the Hampton University Skin of Color Research Institute 2015 Skin of Color Symposium. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S29-S30.

- Luther N, Darvin ME, Sterry W, et al. Ethnic differences in skin physiology, hair follicle morphology and follicular penetration. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;25:182-191.

- Shokeen D. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2016;97:E9-E11.

- Lawson CN, Hollinger J, Sethi S, et al. Updates in the understanding and treatments of skin & hair disorders in women of color. Int J Women’s Dermatol. 2017;3:S21-S37.

- Hu S, Parmet Y, Allen G, et al. Disparity in melanoma: a trend analysis of melanoma incidence and stage at diagnosis among whites, Hispanics, and blacks in Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1369-1374.

- Colby SL, Ortman JM; US Census Bureau. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2014. Current Population Reports, P25-1143. https://census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf. Published March 2015. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, et al. Diversity in dermatology: roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:337-341.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Ernst H, Colthorpe K. The efficacy of interactive lecturing for students with diverse science backgrounds. Adv Physiol Educ. 2007;31:41-44.

- Allday E. UCSF opens ‘skin of color’ dermatology clinic to address disparity in care. San Francisco Chronicle. March 20, 2019. https://www.sfchronicle.com/health/article/UCSF-opens-skin-of-color-dermatology-clinic-13704387.php. Accessed May 13, 2020.

- Van Voorhees AS, Enos CW. Diversity in dermatology residency programs. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S46-S49.

- Enos CW, Harvey VM. From bench to bedside: the Hampton University Skin of Color Research Institute 2015 Skin of Color Symposium. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S29-S30.

Practice Points

- To treat the ever-changing demographics of patients in the United States, dermatologists must receive adequate exposure and education regarding dermatologic conditions in patients from various ethnic backgrounds.

- Dermatology residents from less diverse regions are more likely to agree that dedicated clinics and rotations are important to gain competence compared to those from more diverse regions.

- In areas with less diversity, dedicated multiethnic skin clinics and faculty may be more important for assuring an adequate residency experience.