User login

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is most often treated with mid-potency topical corticosteroids.1,2 Although this option is effective, not all patients respond to treatment, and those who do may lose efficacy over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis. The pathophysiology of tachyphylaxis to topical corticosteroids has been ascribed to loss of corticosteroid receptor function,3 but the evidence is weak.3,4 Patients with severe treatment-resistant AD improve when treated with mid-potency topical steroids in an inpatient setting; therefore, treatment resistance to topical corticosteroids may be largely due to poor adherence.5

Patients with treatment-resistant AD generally improve when treated with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote treatment adherence, but this improvement often is reported for study groups, not individual patients. Focusing on group data may not give a clear picture of what is happening at the individual level. In this study, we evaluated changes at an individual level to determine how frequently AD patients who were previously treated with topical corticosteroids unsuccessfully would respond to desoximetasone spray 0.25% under conditions designed to promote good adherence over a 7-day period.

Methods

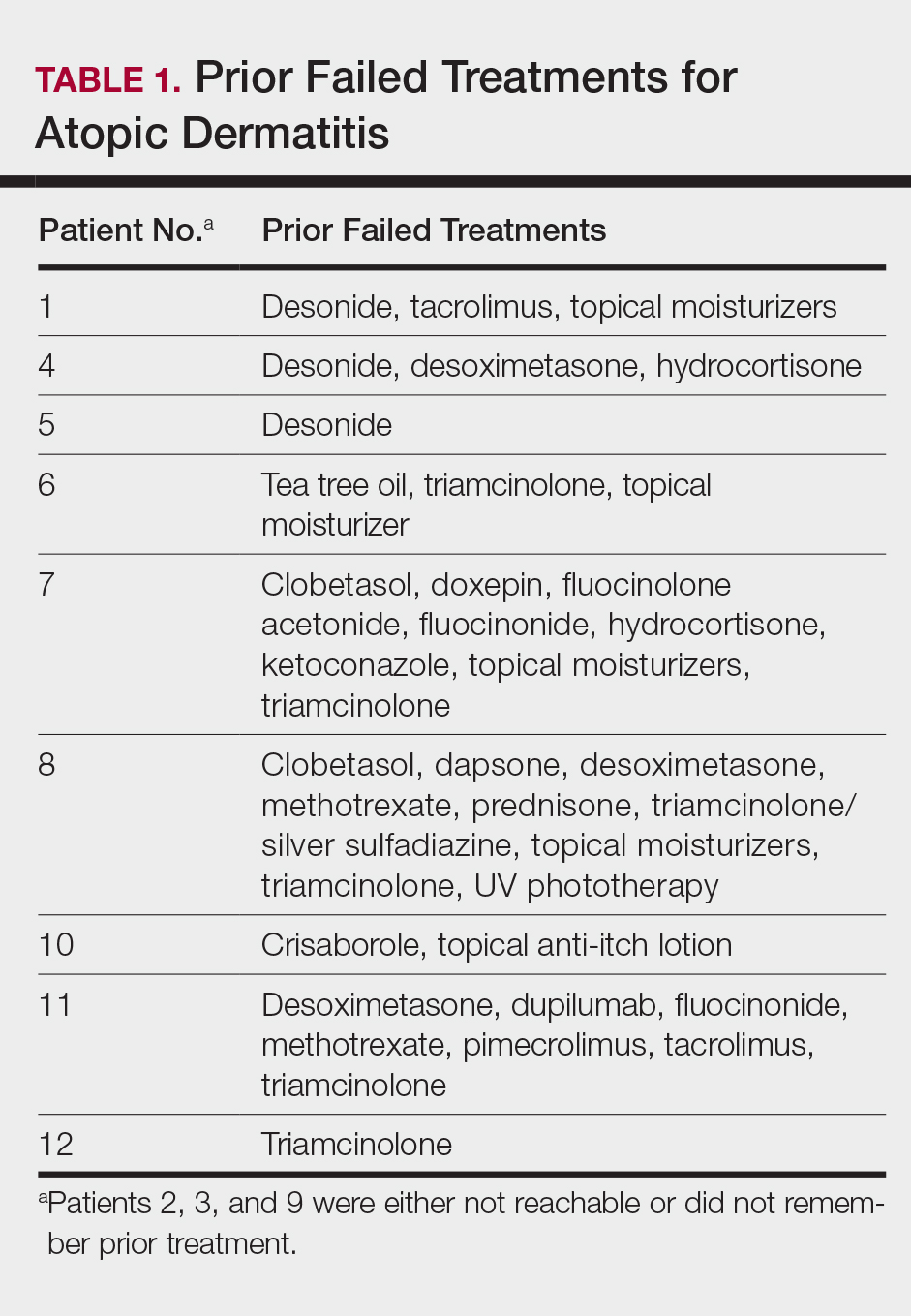

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study included 12 patients with AD who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids in the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(Table 1). The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

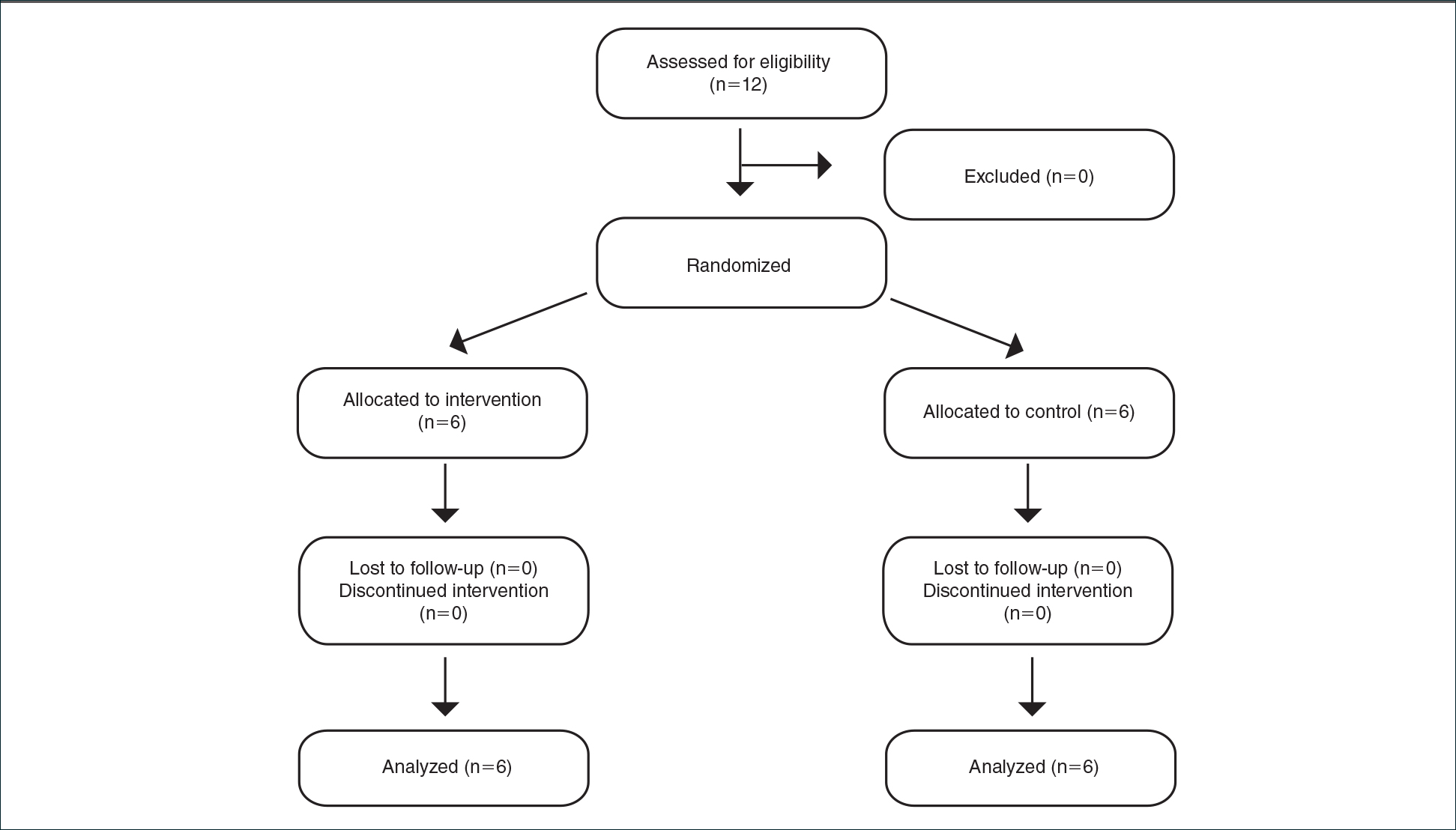

Inclusion criteria included men and women 18 years or older at baseline who had AD that was considered amenable to therapy with topical corticosteroids by the clinician and were able to comply with the study protocol (Figure). Written informed consent also was obtained from each patient. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to practice birth control during participation in the study were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included presence of a condition that in the opinion of the investigator would compromise the safety of the patient or quality of data as well as patients with no access to a telephone throughout the day. Patients diagnosed with conditions affecting adherence to treatment (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), those with a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and those with a history of drug hypersensitivity were excluded from the study.

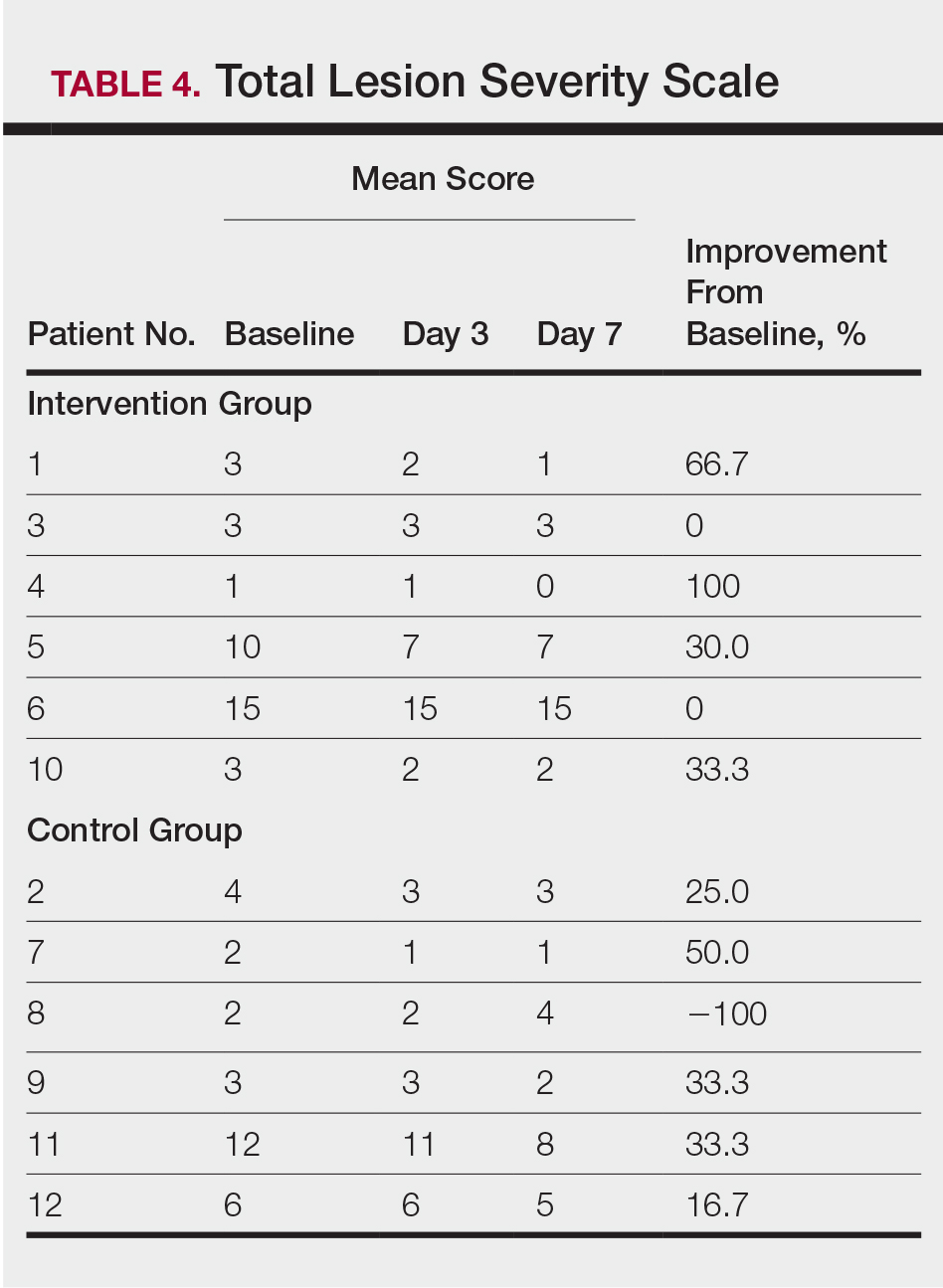

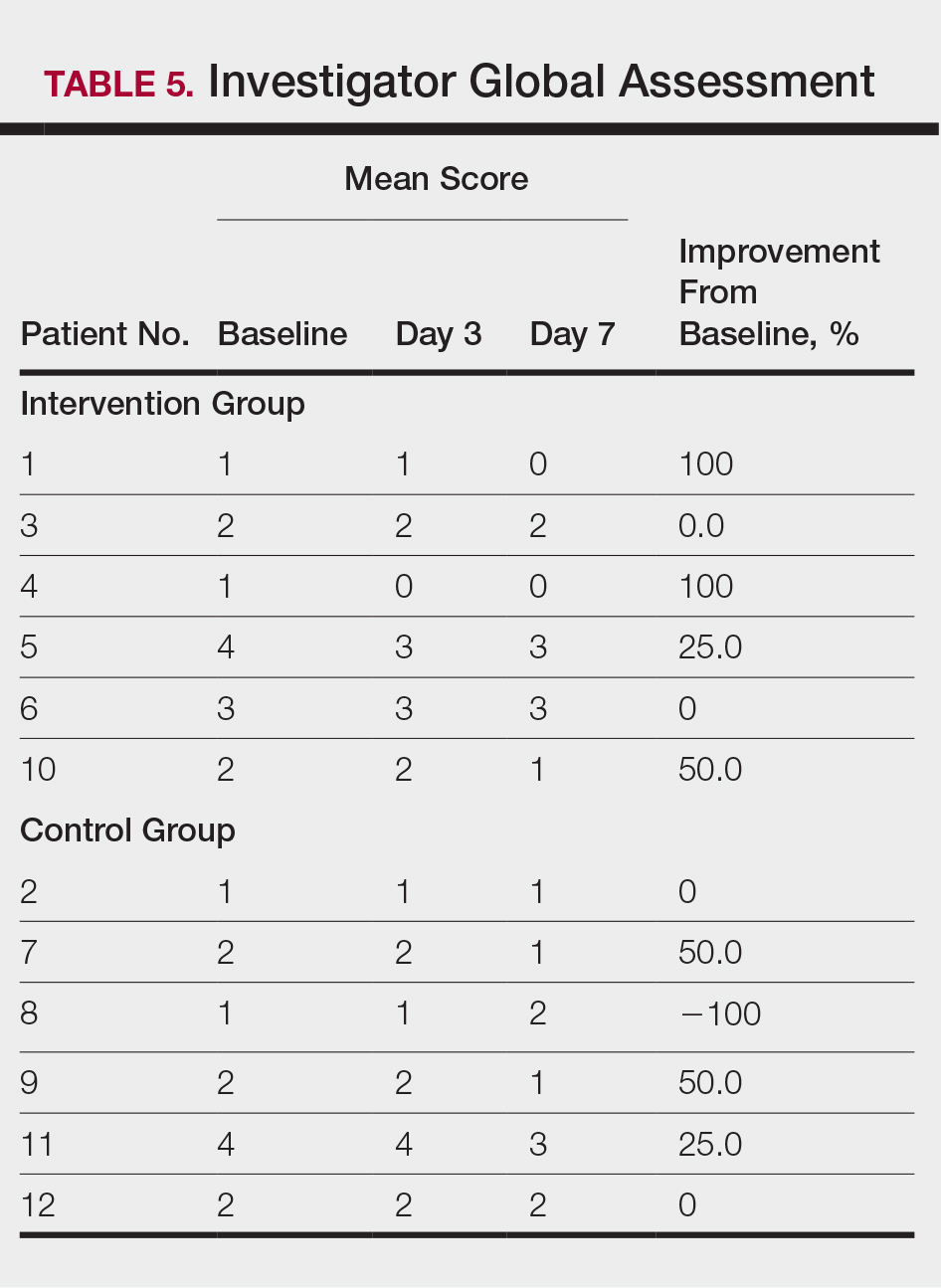

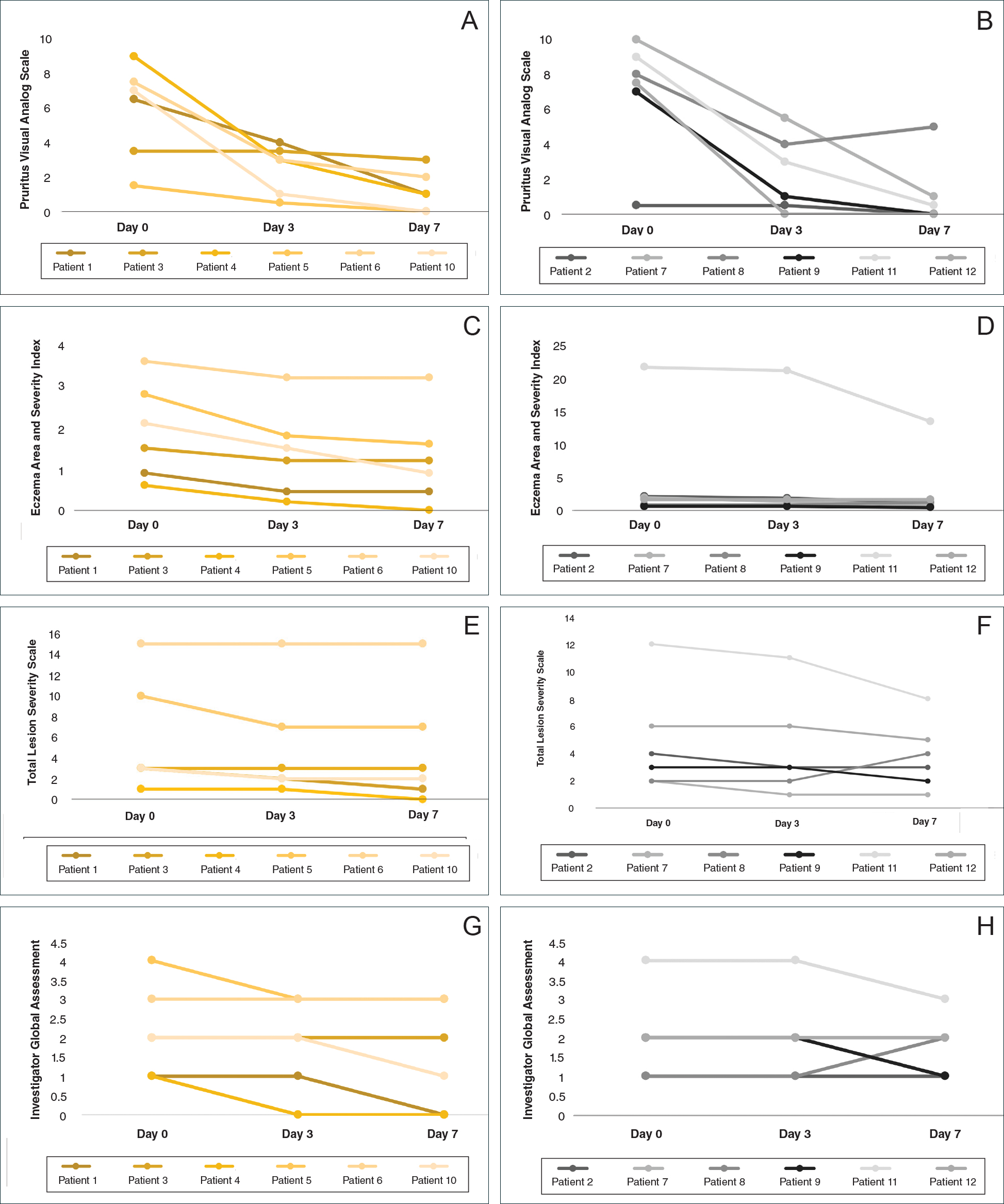

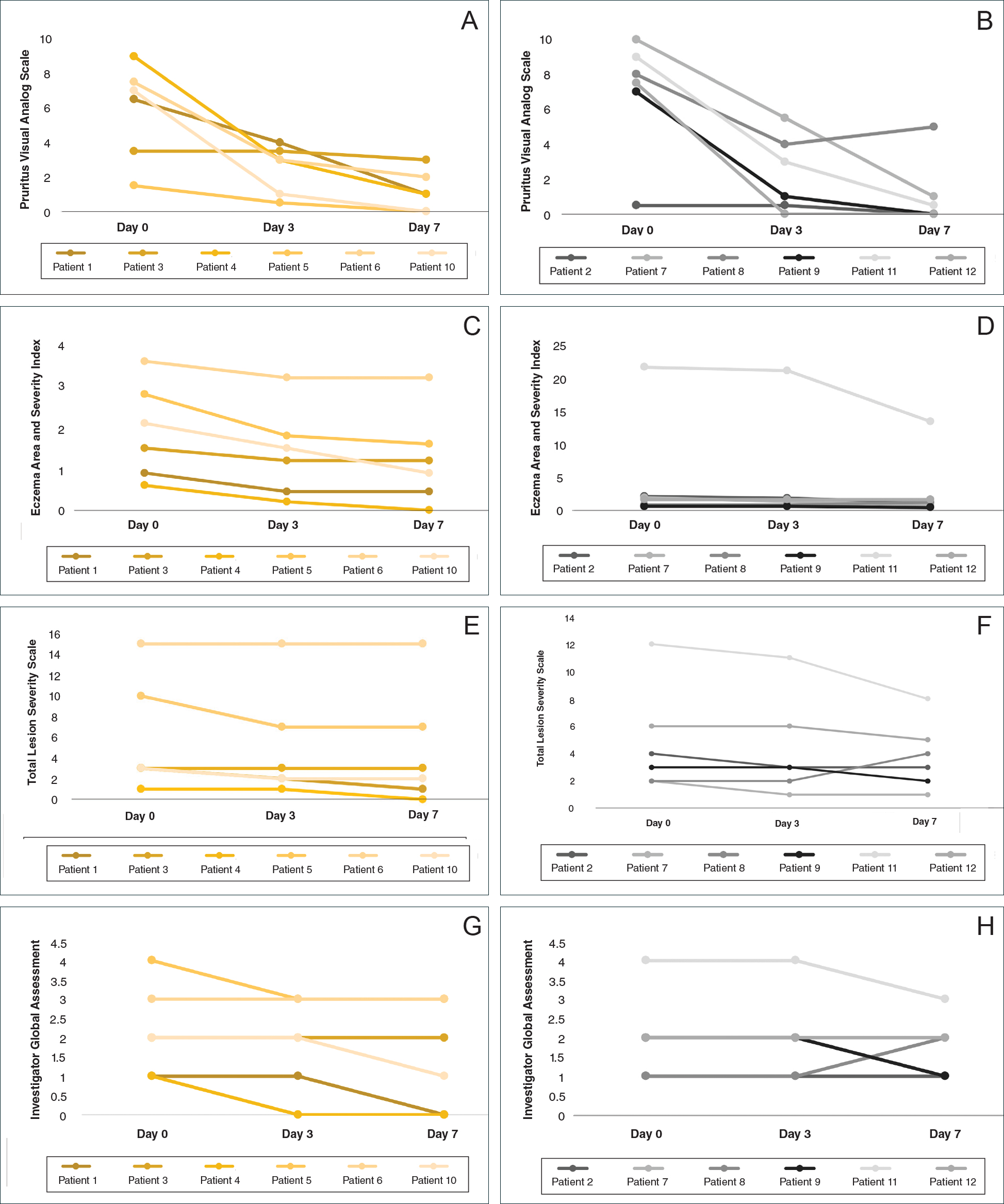

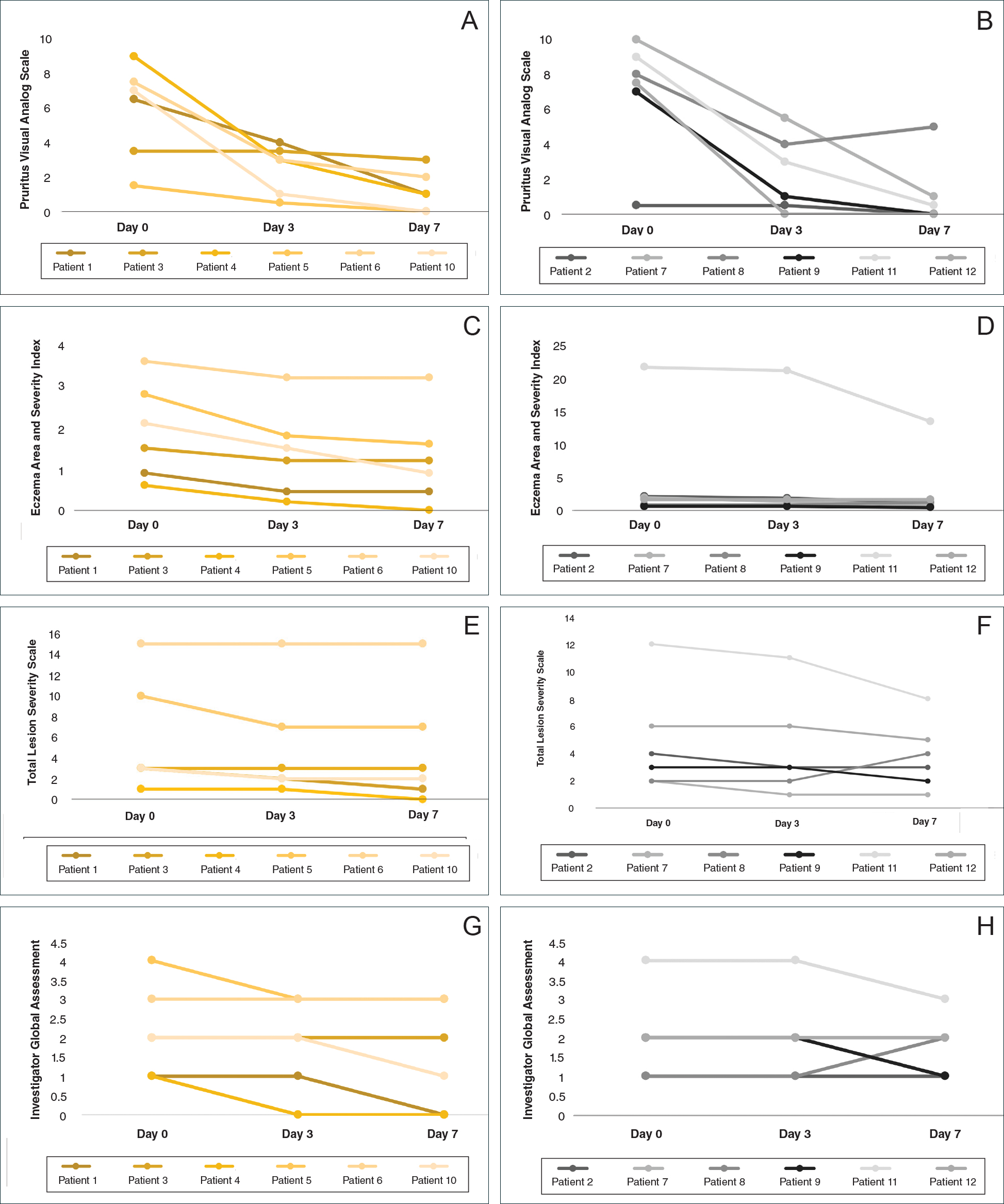

All 12 patients were treated with desoximetasone spray 0.25% for 7 days. Patients were instructed not to use other AD medications during the study period. At baseline, patients were randomized to receive either twice-daily telephone calls to discuss treatment adherence (intervention group) or no telephone calls (control) during the study period. Patients in both the intervention and control groups returned for evaluation on days 3 and 7. During these visits, disease severity was evaluated using the pruritus visual analog scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), total lesion severity scale (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

Results

Twelve AD patients who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids were recruited for the study. Six patients were randomized to the intervention group and 6 were randomized to the control group. Fifty percent of patients were black, 50% were women, and the average age was 50.4 years. All 12 patients completed the study.

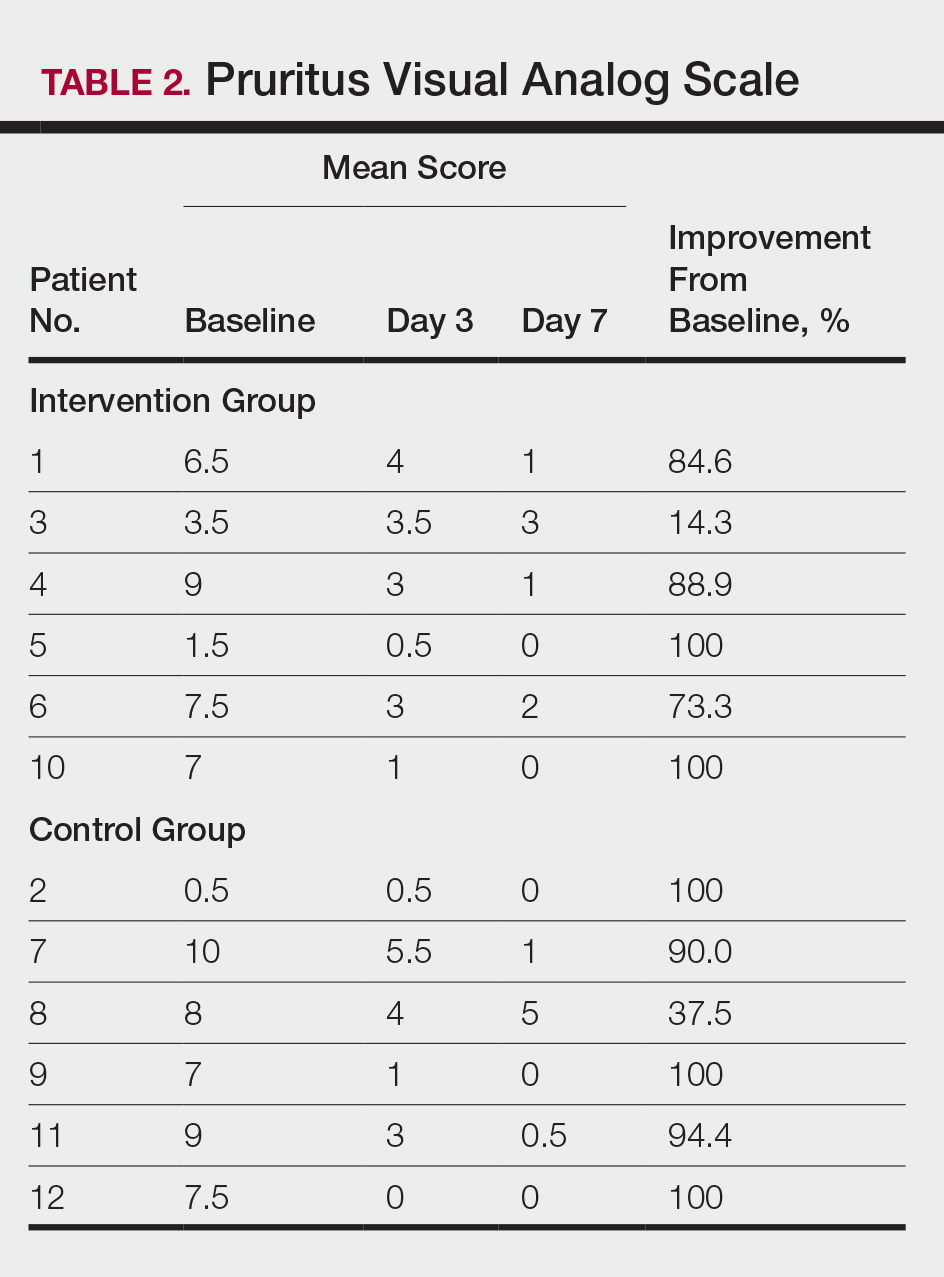

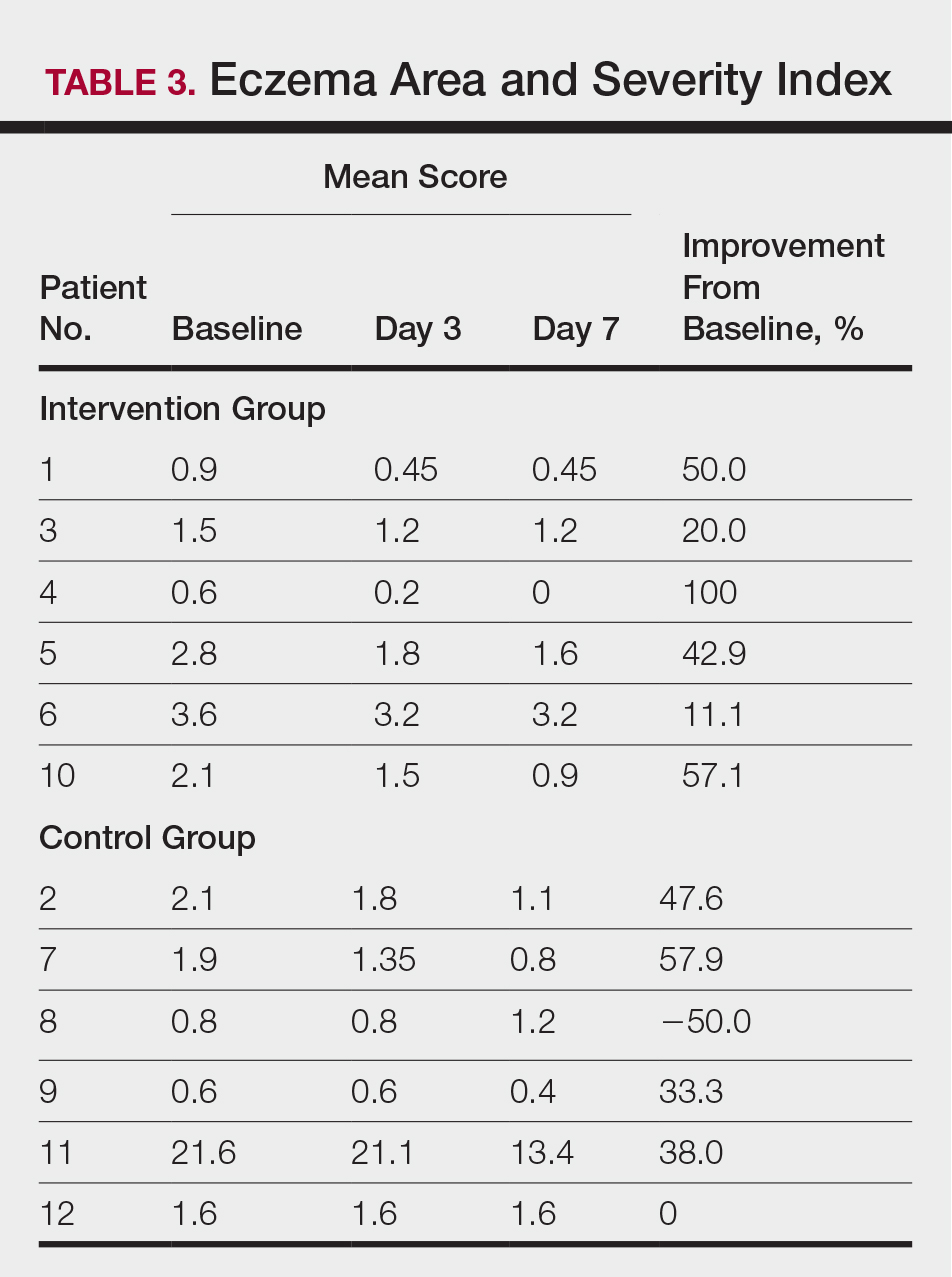

At the end of the study, most patients showed improvement in all evaluation parameters (eFigure). All 12 patients showed improvement in pruritus visual analog scores; 83.3% (10/12) showed improved EASI scores, 75.0% (9/12) showed improved TLSS scores, and 58.3% (7/12) showed improved IGA scores (Tables 2–5). Patients who received telephone calls in the intervention group showed greater improvement compared to those in the control group, except for pruritus; the mean reduction in pruritus was 76.9% in the intervention group versus 87.0% in the control group. The mean improvement in EASI score was 46.9% in the intervention group versus 21.1% in the control group. The mean improvement in TLSS score was 38.3% in the intervention group versus 9.7% in the control group. The mean improvement in IGA score was 45.8% in the intervention group versus 4.2% in the control group. Only one patient in the control group (patient 8) showed lower EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores at baseline.

Comment

Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of AD, many patients report treatment resistance after a period of a few doses or longer.6-9 There is strong evidence demonstrating rapid corticosteroid receptor downregulation in tissues after corticosteroid therapy, which is the accepted mechanism for tachyphylaxis, but the timing of this effect does not match up with clinical experiences. The physiologic significance of corticosteroid agonist-induced receptor downregulation is unknown and may not have any considerable effect on corticosteroid efficacy.3 A systematic review by Taheri et al3 on the development of resistance to topical corticosteroids proposed 2 theories for the underlying pathogenesis of tachyphylaxis: (1) long-term patient nonadherence, and (2) the initial maximal response during the first few weeks of therapy eventually plateaus. Because corticosteroids may plateau after a certain number of doses, natural disease flare-ups during this period may give the wrong impression of tachyphylaxis.10 The treatment “resistance” reported by the patients in our study may have been due to this plateau effect or to poor adherence.

Our finding that nearly all patients had rapid improvement of AD with the topical corticosteroid is not definitive proof but supports the notion that tachyphylaxis is largely mediated by poor adherence to treatment. Patients rapidly improved over the short study period. The short duration of treatment and multiple visits over the study period were designed to help ensure patient adherence. Rapid improvement in AD when topical corticosteroids are used should be expected, as AD patients have rapid improvement with application of topical corticosteroids in inpatient settings.11,12

Poor adherence to topical medication is common. In a Danish study, 99 of 322 patients (31%) did not redeem their AD prescriptions.13 In a single-center, 5-day, prospective study evaluating the use of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for treatment of children and adults with AD, the median percentage of prescribed doses taken was 40%, according to objective electronic monitors, even though patients reported 100% adherence in their medication diaries.Better adherence was seen on day 1 of treatment in which 66.6% (6/9) of patients adhered to their treatment strategy versus day 5 in which only 11.1% (1/9) of patients used their medication.1

Topical corticosteroids are safe and efficacious if used appropriately; however, patients commonly express fear and anxiety about using them. Topical corticosteroid phobia may stem from a misconception that these products carry the same adverse effects as their oral and systemic counterparts, which may be perpetuated by the media.1 Of 200 dermatology patients surveyed, 72.5% expressed concern about using topical corticosteroids on themselves or their children’s skin, and 24% of these patients stated they were noncompliant with their medication because of these worries. Almost 50% of patients requested prescriptions for corticosteroid-sparing medications such as tacrolimus.1 Patient education is important to help ensure treatment adherence. Other factors that can affect treatment adherence include forgetfulness; the chronic nature of AD; the need for ongoing application of topical treatments; prohibitive costs of some topical agents; and complexities in coordinating school, work, and family plans with the treatment regimen.2

We attempted to ensure good treatment adherence in our study by calling the patients in the intervention group twice daily. The mean improvement in EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores was higher in the intervention group versus the control group, which suggests that patient reminders have at least some benefit. Because AD treatment resistance appears more closely tied to nonadherence rather than loss of medication efficacy, it seems prudent to focus on interventions that would improve treatment adherence; however, such interventions generally are not well tested. Recommended interventions have included educating patients about the side effects of topical corticosteroids, avoiding use of medical jargon, and taking patient vehicle preference into account when prescribing treatments.8 Patients should be scheduled for a return visit within 1 to 2 weeks, as early return visits can augment treatment adherence.14 At the return visit, there can be a more detailed discussion of long-term management and side effects.8

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and brief treatment duration. Even though the patients had previously reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids, all demonstrated improvement in only 1 week with a potent topical corticosteroid. The treatment resistance that initially was reported likely was due to poor adherence, but it is possible for AD patients to be resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids due to allergic contact dermatitis. Patients could theoretically be allergic to components of the vehicle used in topical corticosteroids, which could aggravate their dermatitis; however, this effect seems unlikely in our patient population, as all the patients in our study showed improvement following treatment. Another study limitation was that adherence was not measured. The frequent follow-up visits were designed to encourage treatment adherence, but adherence was not specifically assessed. Although patients were encouraged to only use the desoximetasone spray during the study, it is not known whether patients used other products.

Conclusion

Some AD patients exhibit apparent decreased efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time, but this tachyphylaxis phenomenon is more likely due to poor treatment adherence than to loss of corticosteroid responsiveness. In our study, AD patients who reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids improved rapidly with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote good adherence to treatment. The majority of patients improved in all 4 parameters used for evaluating disease severity, with 100% of patients reporting improvement in pruritus. Intervention to improve treatment adherence may lead to better health outcomes. When AD appears resistant to topical corticosteroids, addressing adherence issues may be critical.

- Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:323-332.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Miller JJ, Roling D, Margolis D, et al. Failure to demonstrate therapeutic tachyphylaxis to topically applied steroids in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:546-549.

- Smith SD, Harris V, Lee A, et al. General practitioners knowledge about use of topical corticosteroids in paediatric atopic dermatitis in Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:335-340.

- Sathishkumar D, Moss C. Topical therapy in atopic dermatitis in children. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:656-661.

- Reitamo S, Remitz A. Topical agents for atopic dermatitis. In: Bieber T, ed. Advances in the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. London, United Kingdom: Future Medicine Ltd; 2013:62-72.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Fukaya M. Cortisol homeostasis in the epidermis is influenced by topical corticosteroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:440.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- van der Schaft J, Keijzer WW, Sanders KJ, et al. Is there an additional value of inpatient treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:797-801.

- Dabade TS, Davis DM, Wetter DA, et al. Wet dressing therapy in conjunction with topical corticosteroids is effective for rapid control of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: experience with 218 patients over 30 years at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;67:100-106.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is most often treated with mid-potency topical corticosteroids.1,2 Although this option is effective, not all patients respond to treatment, and those who do may lose efficacy over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis. The pathophysiology of tachyphylaxis to topical corticosteroids has been ascribed to loss of corticosteroid receptor function,3 but the evidence is weak.3,4 Patients with severe treatment-resistant AD improve when treated with mid-potency topical steroids in an inpatient setting; therefore, treatment resistance to topical corticosteroids may be largely due to poor adherence.5

Patients with treatment-resistant AD generally improve when treated with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote treatment adherence, but this improvement often is reported for study groups, not individual patients. Focusing on group data may not give a clear picture of what is happening at the individual level. In this study, we evaluated changes at an individual level to determine how frequently AD patients who were previously treated with topical corticosteroids unsuccessfully would respond to desoximetasone spray 0.25% under conditions designed to promote good adherence over a 7-day period.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study included 12 patients with AD who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids in the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(Table 1). The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Inclusion criteria included men and women 18 years or older at baseline who had AD that was considered amenable to therapy with topical corticosteroids by the clinician and were able to comply with the study protocol (Figure). Written informed consent also was obtained from each patient. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to practice birth control during participation in the study were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included presence of a condition that in the opinion of the investigator would compromise the safety of the patient or quality of data as well as patients with no access to a telephone throughout the day. Patients diagnosed with conditions affecting adherence to treatment (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), those with a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and those with a history of drug hypersensitivity were excluded from the study.

All 12 patients were treated with desoximetasone spray 0.25% for 7 days. Patients were instructed not to use other AD medications during the study period. At baseline, patients were randomized to receive either twice-daily telephone calls to discuss treatment adherence (intervention group) or no telephone calls (control) during the study period. Patients in both the intervention and control groups returned for evaluation on days 3 and 7. During these visits, disease severity was evaluated using the pruritus visual analog scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), total lesion severity scale (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

Results

Twelve AD patients who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids were recruited for the study. Six patients were randomized to the intervention group and 6 were randomized to the control group. Fifty percent of patients were black, 50% were women, and the average age was 50.4 years. All 12 patients completed the study.

At the end of the study, most patients showed improvement in all evaluation parameters (eFigure). All 12 patients showed improvement in pruritus visual analog scores; 83.3% (10/12) showed improved EASI scores, 75.0% (9/12) showed improved TLSS scores, and 58.3% (7/12) showed improved IGA scores (Tables 2–5). Patients who received telephone calls in the intervention group showed greater improvement compared to those in the control group, except for pruritus; the mean reduction in pruritus was 76.9% in the intervention group versus 87.0% in the control group. The mean improvement in EASI score was 46.9% in the intervention group versus 21.1% in the control group. The mean improvement in TLSS score was 38.3% in the intervention group versus 9.7% in the control group. The mean improvement in IGA score was 45.8% in the intervention group versus 4.2% in the control group. Only one patient in the control group (patient 8) showed lower EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores at baseline.

Comment

Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of AD, many patients report treatment resistance after a period of a few doses or longer.6-9 There is strong evidence demonstrating rapid corticosteroid receptor downregulation in tissues after corticosteroid therapy, which is the accepted mechanism for tachyphylaxis, but the timing of this effect does not match up with clinical experiences. The physiologic significance of corticosteroid agonist-induced receptor downregulation is unknown and may not have any considerable effect on corticosteroid efficacy.3 A systematic review by Taheri et al3 on the development of resistance to topical corticosteroids proposed 2 theories for the underlying pathogenesis of tachyphylaxis: (1) long-term patient nonadherence, and (2) the initial maximal response during the first few weeks of therapy eventually plateaus. Because corticosteroids may plateau after a certain number of doses, natural disease flare-ups during this period may give the wrong impression of tachyphylaxis.10 The treatment “resistance” reported by the patients in our study may have been due to this plateau effect or to poor adherence.

Our finding that nearly all patients had rapid improvement of AD with the topical corticosteroid is not definitive proof but supports the notion that tachyphylaxis is largely mediated by poor adherence to treatment. Patients rapidly improved over the short study period. The short duration of treatment and multiple visits over the study period were designed to help ensure patient adherence. Rapid improvement in AD when topical corticosteroids are used should be expected, as AD patients have rapid improvement with application of topical corticosteroids in inpatient settings.11,12

Poor adherence to topical medication is common. In a Danish study, 99 of 322 patients (31%) did not redeem their AD prescriptions.13 In a single-center, 5-day, prospective study evaluating the use of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for treatment of children and adults with AD, the median percentage of prescribed doses taken was 40%, according to objective electronic monitors, even though patients reported 100% adherence in their medication diaries.Better adherence was seen on day 1 of treatment in which 66.6% (6/9) of patients adhered to their treatment strategy versus day 5 in which only 11.1% (1/9) of patients used their medication.1

Topical corticosteroids are safe and efficacious if used appropriately; however, patients commonly express fear and anxiety about using them. Topical corticosteroid phobia may stem from a misconception that these products carry the same adverse effects as their oral and systemic counterparts, which may be perpetuated by the media.1 Of 200 dermatology patients surveyed, 72.5% expressed concern about using topical corticosteroids on themselves or their children’s skin, and 24% of these patients stated they were noncompliant with their medication because of these worries. Almost 50% of patients requested prescriptions for corticosteroid-sparing medications such as tacrolimus.1 Patient education is important to help ensure treatment adherence. Other factors that can affect treatment adherence include forgetfulness; the chronic nature of AD; the need for ongoing application of topical treatments; prohibitive costs of some topical agents; and complexities in coordinating school, work, and family plans with the treatment regimen.2

We attempted to ensure good treatment adherence in our study by calling the patients in the intervention group twice daily. The mean improvement in EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores was higher in the intervention group versus the control group, which suggests that patient reminders have at least some benefit. Because AD treatment resistance appears more closely tied to nonadherence rather than loss of medication efficacy, it seems prudent to focus on interventions that would improve treatment adherence; however, such interventions generally are not well tested. Recommended interventions have included educating patients about the side effects of topical corticosteroids, avoiding use of medical jargon, and taking patient vehicle preference into account when prescribing treatments.8 Patients should be scheduled for a return visit within 1 to 2 weeks, as early return visits can augment treatment adherence.14 At the return visit, there can be a more detailed discussion of long-term management and side effects.8

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and brief treatment duration. Even though the patients had previously reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids, all demonstrated improvement in only 1 week with a potent topical corticosteroid. The treatment resistance that initially was reported likely was due to poor adherence, but it is possible for AD patients to be resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids due to allergic contact dermatitis. Patients could theoretically be allergic to components of the vehicle used in topical corticosteroids, which could aggravate their dermatitis; however, this effect seems unlikely in our patient population, as all the patients in our study showed improvement following treatment. Another study limitation was that adherence was not measured. The frequent follow-up visits were designed to encourage treatment adherence, but adherence was not specifically assessed. Although patients were encouraged to only use the desoximetasone spray during the study, it is not known whether patients used other products.

Conclusion

Some AD patients exhibit apparent decreased efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time, but this tachyphylaxis phenomenon is more likely due to poor treatment adherence than to loss of corticosteroid responsiveness. In our study, AD patients who reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids improved rapidly with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote good adherence to treatment. The majority of patients improved in all 4 parameters used for evaluating disease severity, with 100% of patients reporting improvement in pruritus. Intervention to improve treatment adherence may lead to better health outcomes. When AD appears resistant to topical corticosteroids, addressing adherence issues may be critical.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is most often treated with mid-potency topical corticosteroids.1,2 Although this option is effective, not all patients respond to treatment, and those who do may lose efficacy over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis. The pathophysiology of tachyphylaxis to topical corticosteroids has been ascribed to loss of corticosteroid receptor function,3 but the evidence is weak.3,4 Patients with severe treatment-resistant AD improve when treated with mid-potency topical steroids in an inpatient setting; therefore, treatment resistance to topical corticosteroids may be largely due to poor adherence.5

Patients with treatment-resistant AD generally improve when treated with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote treatment adherence, but this improvement often is reported for study groups, not individual patients. Focusing on group data may not give a clear picture of what is happening at the individual level. In this study, we evaluated changes at an individual level to determine how frequently AD patients who were previously treated with topical corticosteroids unsuccessfully would respond to desoximetasone spray 0.25% under conditions designed to promote good adherence over a 7-day period.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study included 12 patients with AD who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids in the Department of Dermatology at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)(Table 1). The study was approved by the local institutional review board.

Inclusion criteria included men and women 18 years or older at baseline who had AD that was considered amenable to therapy with topical corticosteroids by the clinician and were able to comply with the study protocol (Figure). Written informed consent also was obtained from each patient. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to practice birth control during participation in the study were excluded. Other exclusion criteria included presence of a condition that in the opinion of the investigator would compromise the safety of the patient or quality of data as well as patients with no access to a telephone throughout the day. Patients diagnosed with conditions affecting adherence to treatment (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), those with a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and those with a history of drug hypersensitivity were excluded from the study.

All 12 patients were treated with desoximetasone spray 0.25% for 7 days. Patients were instructed not to use other AD medications during the study period. At baseline, patients were randomized to receive either twice-daily telephone calls to discuss treatment adherence (intervention group) or no telephone calls (control) during the study period. Patients in both the intervention and control groups returned for evaluation on days 3 and 7. During these visits, disease severity was evaluated using the pruritus visual analog scale, Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), total lesion severity scale (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

Results

Twelve AD patients who were previously unsuccessfully treated with topical corticosteroids were recruited for the study. Six patients were randomized to the intervention group and 6 were randomized to the control group. Fifty percent of patients were black, 50% were women, and the average age was 50.4 years. All 12 patients completed the study.

At the end of the study, most patients showed improvement in all evaluation parameters (eFigure). All 12 patients showed improvement in pruritus visual analog scores; 83.3% (10/12) showed improved EASI scores, 75.0% (9/12) showed improved TLSS scores, and 58.3% (7/12) showed improved IGA scores (Tables 2–5). Patients who received telephone calls in the intervention group showed greater improvement compared to those in the control group, except for pruritus; the mean reduction in pruritus was 76.9% in the intervention group versus 87.0% in the control group. The mean improvement in EASI score was 46.9% in the intervention group versus 21.1% in the control group. The mean improvement in TLSS score was 38.3% in the intervention group versus 9.7% in the control group. The mean improvement in IGA score was 45.8% in the intervention group versus 4.2% in the control group. Only one patient in the control group (patient 8) showed lower EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores at baseline.

Comment

Although topical corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of AD, many patients report treatment resistance after a period of a few doses or longer.6-9 There is strong evidence demonstrating rapid corticosteroid receptor downregulation in tissues after corticosteroid therapy, which is the accepted mechanism for tachyphylaxis, but the timing of this effect does not match up with clinical experiences. The physiologic significance of corticosteroid agonist-induced receptor downregulation is unknown and may not have any considerable effect on corticosteroid efficacy.3 A systematic review by Taheri et al3 on the development of resistance to topical corticosteroids proposed 2 theories for the underlying pathogenesis of tachyphylaxis: (1) long-term patient nonadherence, and (2) the initial maximal response during the first few weeks of therapy eventually plateaus. Because corticosteroids may plateau after a certain number of doses, natural disease flare-ups during this period may give the wrong impression of tachyphylaxis.10 The treatment “resistance” reported by the patients in our study may have been due to this plateau effect or to poor adherence.

Our finding that nearly all patients had rapid improvement of AD with the topical corticosteroid is not definitive proof but supports the notion that tachyphylaxis is largely mediated by poor adherence to treatment. Patients rapidly improved over the short study period. The short duration of treatment and multiple visits over the study period were designed to help ensure patient adherence. Rapid improvement in AD when topical corticosteroids are used should be expected, as AD patients have rapid improvement with application of topical corticosteroids in inpatient settings.11,12

Poor adherence to topical medication is common. In a Danish study, 99 of 322 patients (31%) did not redeem their AD prescriptions.13 In a single-center, 5-day, prospective study evaluating the use of fluocinonide cream 0.1% for treatment of children and adults with AD, the median percentage of prescribed doses taken was 40%, according to objective electronic monitors, even though patients reported 100% adherence in their medication diaries.Better adherence was seen on day 1 of treatment in which 66.6% (6/9) of patients adhered to their treatment strategy versus day 5 in which only 11.1% (1/9) of patients used their medication.1

Topical corticosteroids are safe and efficacious if used appropriately; however, patients commonly express fear and anxiety about using them. Topical corticosteroid phobia may stem from a misconception that these products carry the same adverse effects as their oral and systemic counterparts, which may be perpetuated by the media.1 Of 200 dermatology patients surveyed, 72.5% expressed concern about using topical corticosteroids on themselves or their children’s skin, and 24% of these patients stated they were noncompliant with their medication because of these worries. Almost 50% of patients requested prescriptions for corticosteroid-sparing medications such as tacrolimus.1 Patient education is important to help ensure treatment adherence. Other factors that can affect treatment adherence include forgetfulness; the chronic nature of AD; the need for ongoing application of topical treatments; prohibitive costs of some topical agents; and complexities in coordinating school, work, and family plans with the treatment regimen.2

We attempted to ensure good treatment adherence in our study by calling the patients in the intervention group twice daily. The mean improvement in EASI, TLSS, and IGA scores was higher in the intervention group versus the control group, which suggests that patient reminders have at least some benefit. Because AD treatment resistance appears more closely tied to nonadherence rather than loss of medication efficacy, it seems prudent to focus on interventions that would improve treatment adherence; however, such interventions generally are not well tested. Recommended interventions have included educating patients about the side effects of topical corticosteroids, avoiding use of medical jargon, and taking patient vehicle preference into account when prescribing treatments.8 Patients should be scheduled for a return visit within 1 to 2 weeks, as early return visits can augment treatment adherence.14 At the return visit, there can be a more detailed discussion of long-term management and side effects.8

Limitations of our study included a small sample size and brief treatment duration. Even though the patients had previously reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids, all demonstrated improvement in only 1 week with a potent topical corticosteroid. The treatment resistance that initially was reported likely was due to poor adherence, but it is possible for AD patients to be resistant to treatment with topical corticosteroids due to allergic contact dermatitis. Patients could theoretically be allergic to components of the vehicle used in topical corticosteroids, which could aggravate their dermatitis; however, this effect seems unlikely in our patient population, as all the patients in our study showed improvement following treatment. Another study limitation was that adherence was not measured. The frequent follow-up visits were designed to encourage treatment adherence, but adherence was not specifically assessed. Although patients were encouraged to only use the desoximetasone spray during the study, it is not known whether patients used other products.

Conclusion

Some AD patients exhibit apparent decreased efficacy of topical corticosteroids over time, but this tachyphylaxis phenomenon is more likely due to poor treatment adherence than to loss of corticosteroid responsiveness. In our study, AD patients who reported treatment failure with topical corticosteroids improved rapidly with topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote good adherence to treatment. The majority of patients improved in all 4 parameters used for evaluating disease severity, with 100% of patients reporting improvement in pruritus. Intervention to improve treatment adherence may lead to better health outcomes. When AD appears resistant to topical corticosteroids, addressing adherence issues may be critical.

- Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:323-332.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Miller JJ, Roling D, Margolis D, et al. Failure to demonstrate therapeutic tachyphylaxis to topically applied steroids in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:546-549.

- Smith SD, Harris V, Lee A, et al. General practitioners knowledge about use of topical corticosteroids in paediatric atopic dermatitis in Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:335-340.

- Sathishkumar D, Moss C. Topical therapy in atopic dermatitis in children. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:656-661.

- Reitamo S, Remitz A. Topical agents for atopic dermatitis. In: Bieber T, ed. Advances in the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. London, United Kingdom: Future Medicine Ltd; 2013:62-72.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Fukaya M. Cortisol homeostasis in the epidermis is influenced by topical corticosteroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:440.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- van der Schaft J, Keijzer WW, Sanders KJ, et al. Is there an additional value of inpatient treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:797-801.

- Dabade TS, Davis DM, Wetter DA, et al. Wet dressing therapy in conjunction with topical corticosteroids is effective for rapid control of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: experience with 218 patients over 30 years at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;67:100-106.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

- Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:323-332.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Taheri A, Cantrell J, Feldman SR. Tachyphylaxis to topical glucocorticoids; what is the evidence? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19:18954.

- Miller JJ, Roling D, Margolis D, et al. Failure to demonstrate therapeutic tachyphylaxis to topically applied steroids in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:546-549.

- Smith SD, Harris V, Lee A, et al. General practitioners knowledge about use of topical corticosteroids in paediatric atopic dermatitis in Australia. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:335-340.

- Sathishkumar D, Moss C. Topical therapy in atopic dermatitis in children. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:656-661.

- Reitamo S, Remitz A. Topical agents for atopic dermatitis. In: Bieber T, ed. Advances in the Management of Atopic Dermatitis. London, United Kingdom: Future Medicine Ltd; 2013:62-72.

- Krejci-Manwaring J, Tusa MG, Carroll C, et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:211-216.

- Fukaya M. Cortisol homeostasis in the epidermis is influenced by topical corticosteroids in patients with atopic dermatitis. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:440.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- van der Schaft J, Keijzer WW, Sanders KJ, et al. Is there an additional value of inpatient treatment for patients with atopic dermatitis? Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:797-801.

- Dabade TS, Davis DM, Wetter DA, et al. Wet dressing therapy in conjunction with topical corticosteroids is effective for rapid control of severe pediatric atopic dermatitis: experience with 218 patients over 30 years at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;67:100-106.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Sagransky MJ, Yentzer BA, Williams LL, et al. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1428-1430.

Practice Points

- Mid-potency corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD).

- Atopic dermatitis may fail to respond to topical corticosteroids initially or lose response over time, a phenomenon known as tachyphylaxis.

- Nonadherence to medication is the most likely cause of treatment resistance in patients with AD.