Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) is a common cause of leg pain during exertion in athletic and active-duty populations.1 It is caused by an increase in intramuscular pressure to a point that the tissues within the involved compartment become ischemic because of a decrease in arteriolar blood flow.2 This relative ischemia causes pain and may also be associated with neurologic symptoms. By definition, the pain associated with CECS resolves with rest. Patients typically describe a feeling of fullness or tightness, which eventually evolves into pain as they continue exercising. Pain onset is usually predictable and reproducible after a finite amount of time and/or intensity of exercise.

The differential diagnosis of leg pain during exercise includes CECS, medial tibial stress syndrome, popliteal entrapment syndrome, myopathy, peripheral nerve entrapment syndromes, stress fracture, and effort-induced rhabdomyolysis.3 CECS can be differentiated from other causes of leg pain with measurement of compartment pressures (the standard recommendation).4 Compartment pressure measurement, however, is invasive, time-consuming, and painful and may be associated with bleeding risk, infection, and nerve injury. Noninvasive means of testing for CECS (eg, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], near-infrared spectroscopy [NIRS], thallium stress testing) remain experimental and expensive and are not easily accessible at all institutions.5-8 While invasive compartment pressure (ICP) testing remains an important tool in the diagnosis of CECS, its criteria and execution vary considerably. Aweid and colleagues4 performed a meta-analysis of use of ICP testing in the diagnosis of CECS and concluded that, though elevated ICP measurements are accepted as the gold standard for diagnosing CECS, the criteria outlined for a positive test lack high-level supporting evidence. In addition, how the test is performed has been inconsistent across studies—further clouding the literature.4

The review by Aweid and colleagues4 highlights the deficiencies in diagnosing CECS by ICP testing. In clinical practice, ICP testing is challenging for both the patient and physician. As other validated, less-invasive tests are lacking, emphasis should remain on the history and the physical examination. Although all athletic populations are at risk for CECS, the active-duty military population is at particularly high risk because of the physical requirements and demands of military service.1,9

We surveyed military orthopedic surgeons to investigate the clinical practice of performing ICP testing in patients with suspected CECS. We hypothesized that the rate of ICP testing among military orthopedic surgeons would not be 100% for patients with the typical signs and symptoms of CECS.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board at Wright-Patterson Medical Center at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. A link to an online survey was distributed by email to members of the Society of Military Orthopaedic Surgeons. The anonymous survey polled the surgeons regarding basic demographic data and clinical practice as it pertains to the evaluation and treatment of CECS. No patient-protected health information was obtained. Survey results were compiled in a Microsoft Excel file for analysis.

Results

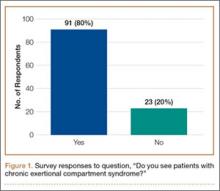

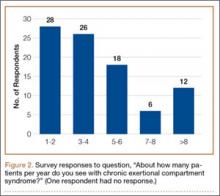

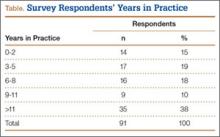

The survey was distributed to 606 email accounts; the response rate was 19% (114/606). Ninety-one surgeons (80%) indicated they have patients with CECS in their practice (Figure 1). Surgeons were asked how many CECS patients they see per year (responses are summarized in Figure 2) and how many years they have been in practice (Table).

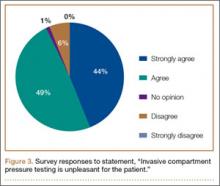

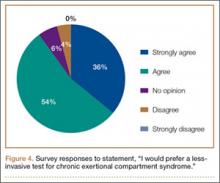

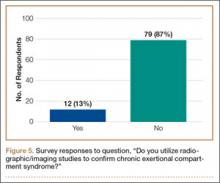

Ninety-three percent of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that ICP testing is unpleasant for the patient (Figure 3), and 90% would prefer a less-invasive test for confirmatory testing for CECS (Figure 4). Only 13% of respondents indicated they actually use noninvasive modalities (eg, MRI, NIRS) to confirm the diagnosis of CECS (Figure 5).

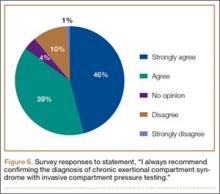

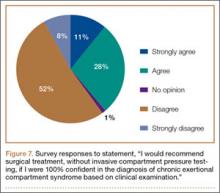

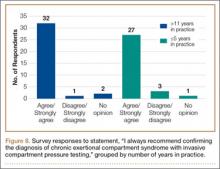

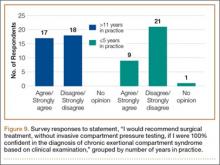

Respondents were asked about the practice of using ICP testing in the diagnosis of CECS (responses are summarized in Figures 6, 7). Although 85% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with always confirming the diagnosis of CECS with ICP testing, 39% stated they would recommend surgical treatment without ICP testing if they were confident about the diagnosis based on clinical examination findings.

To better understand the apparent discrepancy between the percentage of surgeons who agreed or strongly agreed with always recommending ICP testing (85%) and the percentage who would recommend treatment without testing (39%), responses were stratified by clinical experience. Surgeons in practice more than 11 years (n = 35) were compared with those in practice 5 years or less (n = 31) (Table). Although the vast majority (85%) of respondents from both groups agreed or strongly agreed with always recommending ICP testing, 49% of those in practice more than 11 years and 29% in practice 5 years or less indicated they would recommend surgical treatment for CECS based solely on clinical examination findings (Figures 8, 9).