Spondylolysis is a bone defect of the pars interarticularis. It is usually seen in adolescents who participate in sporting activities that involve repetitive axial loads to a hyperextended lower back, such as football offensive lineman, throwing athletes, and gymnasts. It occurs frequently in the L5 pars and can be unilateral or bilateral. The majority of reported multiple-level spondylolysis is at consecutive lumbar segments.1-6 Rarely, it affects noncontiguous levels. Most patients respond well to conservative treatment in the form of activity modification and orthosis.7 Surgical intervention is considered if 6 months of conservative management fails, spondylolisthesis develops, or intractable neurologic symptoms arise.

This case report presents an 18-year-old man with noncontiguous spondylolysis at L2 and L5 who was successfully treated with a 1-level pars repair at L2 after failed conservative management. This unique case highlights the importance of using single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan and diagnostic pars block when planning for surgical treatment in the rare cases of noncontiguous spondylolysis. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

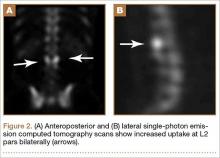

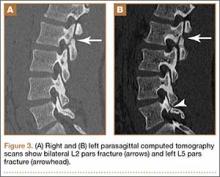

An 18-year-old man presented to the clinic with worsening lower back pain for the previous 4 weeks. He was playing high school baseball and stated the pain was worse when he swung his bat. He had no history of trauma or back pain. Rest was the only alleviating factor, and he was beginning to experience pain when he stood after sitting. He denied any radicular pain. On examination, he had midline tenderness along the upper lumbar spine and pain with lumbar spine extension. His neurologic examination showed normal sensation with 5/5 strength in all key muscle groups. Plain radiograph of the lumbar spine showed an L5 pars defect (Figures 1A, 1B). A SPECT scan showed increased uptake at L2 pars bilaterally; the L5 pars did not show increased uptake (Figures 2A, 2B). A computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed bilateral L2 pars fractures and a left L5 pars fracture (Figures 3A, 3B). Bony changes in the form of marginal sclerosis at the L5, but not the L2, pars suggested that the L2 fracture was acute while the L5 fracture was chronic (Figures 4A, 4B).

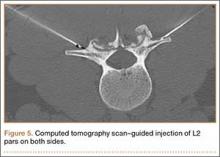

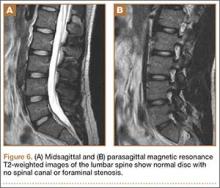

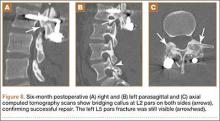

The patient had conservative management for 6 months in the form of lumbosacral orthosis (LSO), cessation of sports activities, and physical therapy. The patient was initially treated with an LSO brace for 3 months, after which he had physical therapy. At 6 month follow-up, he reported continuing, significant back pain. A repeat CT scan of the lumbar spine showed no interval healing of the bilateral L2 or the unilateral L5 pars fractures. As a result of the patient’s noncontiguous pars fractures, a diagnostic CT-guided block of L2 pars was performed to identify which level was his main pain generator (Figure 5). He reported a brief period of complete pain relief after the L2 pars block. With failure of 6 months’ conservative management and positive SPECT scan and diagnostic block, surgical treatment was recommended. Prior to surgical intervention, magnetic resonance imaging was obtained to rule out pathology (eg, disc degeneration, infection, or tumor) other than the pars defect that could require fusion instead of pars repair (Figures 6A, 6B). Because of the patient’s young age, bilateral L2 pars repair rather than fusion was indicated. After 8 months of persistent back pain, he underwent bilateral L2 pars repair with iliac crest autograft, pedicle screws, and sublaminar hook fixation (Figures 7A, 7B). The patient had an uneventful immediate postoperative course. A 6-month postoperative CT scan showed bridging callus at the L2 pars; however, the left L5 pars fracture was still visible (Figures 8A-8C). Over a 6-month postoperative period, the patient had continued improvement in his back pain, advanced his activity as tolerated without problem, and was allowed to resume his sports activities. At 2-year follow-up, he was playing baseball and basketball, and denied any back pain.

Discussion

Lumbar spondylolysis is commonly seen at the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae, and accounts for more than 95% of spondylolysis cases.8 Multiple-level spondylolysis is a relatively rare finding with an incidence varying between 1.2% and 5.6%. The majority of the reported multiple-level cases are adjacent.1-3,6 Adolescents often present with a history of insidious-onset low back pain without radicular symptoms that is exacerbated by activity. Occasionally, an acute injury may elicit the onset of pain. A thorough history with emphasis on pain in relation to activity and sports involvement is beneficial. The patient in the current study was a throwing athlete and presented with 4 weeks of back pain that worsened with activity; he had no history of trauma.