Sample Size Analysis

We calculated the minimum detectable effect size with 80% power at an alpha level of 0.05 for the nonparametric rank sum test in terms of the proportion of every possible pair of patients treated with the 2 treatments, where the patient treated with liposomal bupivacaine has a lower pain score than the patient treated with ISNB. For pain score at 18 to 24 hours, the sample sizes of 33 patients treated with liposomal bupivacaine and 20 treated with ISNB, the minimum detectable effect size is 73%.

Results

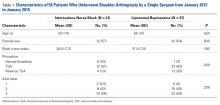

Fifty-eight patient charts (21 in the ISNB group and 37 in the liposomal bupivacaine group) were reviewed for the study. Patient sex distribution, mean age, mean body mass index, and mean baseline ASA scores were not statistically different (Table 1).

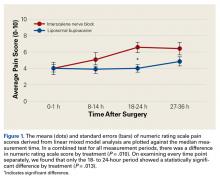

In the ISNB group, 5 patients had hemiarthroplasty, 12 had TSA, and 4 had reverse TSA. In the liposomal bupivacaine group, 1 patient had hemiarthroplasty, 23 had TSA, and 13 had reverse TSA. Frequency of procedure types was significantly different between groups (P = .039), with the liposomal bupivacaine group undergoing fewer hemiarthroplasties.The primary outcome measure, NRS pain score, showed no significant differences between groups at 0 to 1 hour after surgery (P = .99) or 8 to 14 hours after surgery (P = .208).

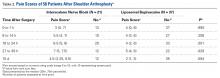

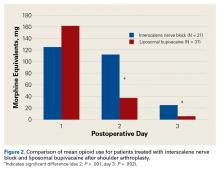

At 18 to 24 hours after surgery, the liposomal bupivacaine group had a lower mean NRS score than the ISNB group (P = .001). This was statistically significant when taking repeated measures of variance into account (Figure 1). Mean NRS score was also lower for the liposomal bupivacaine group at 27 to 36 hours after surgery (P = .029). This was a significant difference when repeated measures of variance was considered (Table 2).There was no difference in the amount of intravenous acetaminophen given during the hospital stay between groups. There was no significant difference in opioid consumption on postoperative day 1 in the hospital (P = .59) (Figure 2). However, there were significant differences between groups on postoperative days 2 and 3.

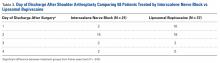

On postoperative day 2, the ISNB group required significantly more opioids (mean, 112 mg morphine equivalents) than the liposomal bupivacaine group (mean, 37 mg morphine equivalents) (P = .001). The ISNB group also required significantly more opioids (mean, 25 mg morphine equivalents) on postoperative day 3 than the liposomal bupivacaine group (mean, 5 mg) (P = .002).Sixteen of 37 patients in the liposomal bupivacaine group and 2 of 21 in the ISNB group were discharged on the day after surgery (P = .010) (Table 3).

The mean LOS was 46 ± 20 hours for the liposomal bupivacaine group and 57 ± 14 hours for the ISNB group (P = .012).There were no major cardiac or respiratory events in either group. No long-term paresthesias or neuropathies were noted. There were no readmissions for either group.

Discussion

Postoperative pain control after shoulder arthroplasty can be challenging, and several modalities have been tried in various combinations to minimize pain and decrease adverse effects of opioid medications. The most common method for pain relief after shoulder arthroplasty is the ISNB. Several studies of ISNBs have shown improved pain control after shoulder arthroplasty with associated decreased opioid consumption and related side effects.10 Patient rehabilitation and satisfaction have improved with the increasing use of peripheral nerve blocks.11

Despite the well-established benefits of ISNBs, several limitations exist. Although the superior portion of the shoulder is well covered by an ISNB, the inferior portion of the brachial plexus can remain uncovered or only partially covered.12 Complications of ISNBs include hemidiaphragmatic paresis, rebound pain 24 hours after surgery,13 chronic neurologic complications,14 and substantial respiratory and cardiovascular events.15 Nerve blocks also require additional time and resources in the perioperative period, including an anesthesiologist with specialized training, assistants, and ultrasonography or nerve stimulation equipment contraindicated in patients taking blood thinners.16

Periarticular injections of local anesthetics have also shown promise in reducing pain after arthroplasty.4 Benefits include an enhanced safety profile because local injection avoids the concurrent blockade of the phrenic nerve and recurrent laryngeal nerve and has not been associated with the risk of peripheral neuropathies. Further, local injection is a simple technique that can be performed during surgery without additional personnel or expertise. A limitation of this approach is the relatively short duration of effectiveness of the local anesthetic and uncertainty regarding the best agent and the ideal volume of injection.6 Liposomal bupivacaine is a new agent (approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 201117) with a sustained release over 72 to 96 hours.18 The most common adverse effects of liposomal bupivacaine are nausea, vomiting, constipation, pyrexia, dizziness, and headache.19 Chondrotoxicity and granulomatous inflammation are more serious, yet rare, complications of liposomal bupivacaine.20

We found that liposomal bupivacaine injections were associated with lower pain scores compared with ISNB at 18 to 24 hours after surgery. This correlated with less opioid consumption in the liposomal bupivacaine group than in the ISNB group on the second postoperative day. These differences in pain values are consistent with the known pharmacokinetics of liposomal bupivacaine.18 Peak plasma levels normally occur approximately 24 hours after injection, leaving the early postoperative period relatively uncovered by anesthetic agent. This finding of relatively poor pain control early after surgery has also been noted in patients undergoing knee arthroplasty.5 On the basis of the findings of this study, we have added standard bupivacaine injections to our separate liposomal bupivacaine injection to cover early postoperative pain. Opioid consumption was significantly lower in the liposomal bupivacaine group than in the ISNB group on postoperative days 2 and 3. We did not measure adverse events related to opioid consumption, so we cannot comment on whether the decreased opioid consumption was associated with the rate of adverse events. However, other studies21,22 have established this relationship.

We found the liposomal bupivacaine group to have earlier discharges to home. Sixteen of 37 patients in the liposomal bupivacaine group compared with 2 of 21 patients in the ISNB group were discharged on the day after surgery. A mean reduction in LOS of 18 hours for the liposomal bupivacaine group was statistically significant (P = .012). This reduction in LOS has important implications for hospitals and value analysis committees considering whether to keep a new, more expensive local anesthetic on formulary. Savings from reduced LOS and improvements in patient satisfaction may justify the expense (approximately $300 per 266-mg vial) of Exparel.

From a societal cost perspective, liposomal bupivacaine is more economical compared with ISNB, which adds approximately $1500 to the cost of anesthesia per patient.23 Eliminating the costs associated with ISNB administration in shoulder arthroplasties could result in substantial savings to our healthcare system. More research examining time savings and exact costs of each procedure is needed to determine the true cost effectiveness of each approach.

Limitations of our study include the retrospective design, relatively small numbers of patients in each group, missing data for some patients at various time points, variation in the types of procedures in each group, and lack of long-term outcome measures. It is important to note that we did not confirm the success of the nerve block after administration. However, this study reflects the effectiveness of each of the modalities in actual clinical conditions (as opposed to a controlled experimental setting). The actual effectiveness of a nerve block varies, even when performed by an experienced anesthesiologist with ultrasound guidance. Furthermore, immediate postoperative pain scores in the nerve block group are consistent with those of prior research reporting pain values ranging from 4 to 5 and a mean duration of effect ranging from 9 to 14 hours.23,24 Additionally, the patients, surgeon, and nursing team were not blinded to the treatment group. Although we did note a significant difference in the types of procedures between groups, this finding is related to the greater number of hemiarthroplasties performed in the ISNB group (N = 5) compared with the liposomal group (N = 1). Because of this variation and the decreased invasiveness of hemiarthroplasties, the bias is against the liposomal group. Finally, our primary outcome variable was pain, which is a subjective, self-reported measure. However, our opioid consumption data and LOS data corroborate the improved pain scores in the liposomal bupivacaine group.

Limiting the study to a single surgeon may limit external validity. Another limitation is the lack of data on adverse events related to opioid medication use. There was no additional experimental group to determine whether less expensive local anesthetics injected locally would perform similarly to liposomal bupivacaine. In total knee arthroplasty, periarticular injections of liposomal bupivacaine were not as effective as less expensive periarticular injections.25 It is unclear which agents (and in what doses or combinations) should be used for periarticular injections. Finally, we acknowledge that our retrospective study design cannot account for all potential factors affecting discharge time.

This is the first comparative study of liposomal bupivacaine and ISNB in TSA. The study design allowed us to control for variables such as surgical technique, postoperative protocols (including use and type of sling), and use of other pain modalities such as patient-controlled analgesia and intravenous acetaminophen that are likely to affect postoperative pain and LOS. This study provides preliminary data that confirm relative equipoise between liposomal bupivacaine and ISNB, which is needed for the ethical conduct of a randomized controlled trial. Such a trial would allow for a more robust comparison, and this retrospective study provides appropriate pilot data on which to base this design and the clinical information needed to counsel patients during enrollment.

Our results suggest that liposomal bupivacaine may provide superior or similar pain relief compared with ISNB after shoulder arthroplasty. Additionally, the use of liposomal bupivacaine was associated with decreased opioid consumption and earlier discharge to home compared with ISNB. These findings have important implications for pain control after TSA because pain represents a major concern for patients and providers after surgery. In addition to clinical improvements, use of liposomal bupivacaine may save time and eliminate costs associated with administering nerve blocks. Local injection may also be used in patients who are contraindicated for ISNB such as those with obesity, pulmonary disease, or peripheral neuropathy. Although we cannot definitively suggest that liposomal bupivacaine is superior to the current gold standard ISNB for pain control after shoulder arthroplasty, our results suggest a relative clinical equipoise between these modalities. Larger analytical studies, including randomized trials, should be performed to explore the potential benefits of liposomal bupivacaine injections for pain control after shoulder arthroplasty.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):424-430. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.