Take-Home Points

- Anchors placed posterior to the biceps during SLAP repair are at risk for glenoid vault penetration and/or suprascapular nerve (SSN) injury.

- Vault penetration and SSN injury are avoided by using a Port of Wilmington (PW) portal instead of an anterior portal.

- A percutaneous PW portal is safe and passes through the rotator cuff muscle only.

Since being classified by Snyder and colleagues,1 various arthroscopic techniques have been used to repair superior labrum anterior and posterior (SLAP) tears, particularly type II tears. Despite being commonly performed, repairs of SLAP lesions remain challenging. There is high variability in the rate of good/excellent functional outcomes and athletes’ return to previous level of play after SLAP repairs.2,3 Furthermore, the rate of complications after SLAP repair is as high as 5%.4

One of the most common complications of repair of a type II SLAP tear is nerve injury.4 In particular, suprascapular nerve (SSN) injury has occurred after arthroscopic repair of SLAP tears.5,6 Three cadaveric studies have demonstrated that glenoid vault penetration is common during placement of knotted anchors for SLAP repair and that the SSN is at risk during placement of these anchors.7-9 However, 2 of the 3 studies used only an anterior portal in their evaluation of anchor placement. Safety of anchor placement posterior to the biceps tendon may be improved with a percutaneous approach using a Port of Wilmington (PW) portal.10,11 No studies have evaluated the risk of glenoid vault penetration and SSN injury with shorter knotless anchors.

We conducted a study to compare a standard anterosuperolateral (ASL) portal with a percutaneous PW portal for knotless anchors placed posterior to the biceps tendon during repair of SLAP tears. We hypothesized that anchors placed through the PW portal would be less likely to penetrate the glenoid vault and would be farther from the SSN in the event of bone penetration.

Materials and Methods

Six matched pairs of fresh human cadaveric shoulders were used in this study. Each specimen included the scapula, the clavicle, and the humerus. All 6 specimens were male, and their mean age was 41.2 years (range, 23-59 years). Shoulder arthroscopy was performed for placement of SLAP anchors, and open dissection followed.

Anchor Placement

The scapula was clamped and the shoulder placed in the lateral decubitus position with 30° of abduction, 20° of forward flexion, and neutral rotation.10 A standard posterior glenohumeral viewing portal was established and a 30° arthroscope inserted. Both shoulders of each matched pair were randomly assigned to anchor placement through either an ASL portal or a PW portal. Two anchors were placed in the superior glenoid to simulate repair of a posterior SLAP tear.11 Each was a 2.9-mm short (12.5-mm) knotless anchor (BioComposite PushLock; Arthrex) that included a polyetheretherketone (PEEK) eyelet for threading sutures before anchor placement. A drill guide was inserted according to manufacturer guidelines, and a 2.9-mm drill was used to make a bone socket 18 mm deep. The anchor eyelet was loaded with suture tape (Labral Tape; Arthrex), and the anchor and suture were inserted into the socket. The sutures were left uncut to aid in anchor visualization during open dissection. On a right shoulder, the first anchor was placed just posterior to the biceps tendon, at 11 o’clock, and the second anchor about 1 cm posterior to the first, at 10 o’clock. All anchors were placed by an arthroscopy fellowship–trained shoulder surgeon. Before placement, anchor location was confirmed by another arthroscopy fellowship–trained shoulder surgeon.

The ASL portal was created, with an 18-gauge spinal needle and an outside-in technique, about 1 cm lateral to the anterolateral corner of the acromion.

The portal was established through the rotator interval just anterior to the leading edge of the supraspinatus tendon and posterior to the long head of the biceps tendon. In this portal, an 8.25-mm threaded cannula was inserted for anchor placement (Figure 1).In the opposite shoulder, the PW portal was created, with a percutaneous technique, about 1 cm anterior and 1 cm lateral to the posterolateral corner of the acromion. An 18-gauge spinal needle was inserted to allow a 45° angle of approach to the posterosuperior glenoid.11

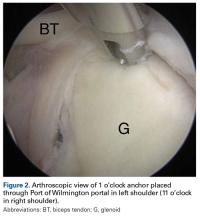

A guide wire was threaded through the needle, and the needle was removed. Then the portal was dilated, and a 4.5-mm metal cannula was inserted for anchor placement (Figure 2).Cadaveric Dissection

After anchor placement, another shoulder surgeon performed the dissection. Skin, subcutaneous tissue, deltoid, and clavicle were removed. In the percutaneous specimens, PW portal location relative to rotator cuff was recorded before cuff removal. After overlying soft tissues were removed from a specimen, the anchors were examined for glenoid vault penetration. In the setting of vault penetration, digital calipers were used to measure the shortest distance from anchor to SSN.