Radiographs

It is imperative to obtain good-quality radiographs, including axial radiographs of the patella in early flexion, to check for evidence of arthrosis and other joint pathology that may be producing pain. Dr. Post always obtains bilateral knee radiographs to help understand the degree of any arthrosis or malalignment in the contralateral asymptomatic knee. The information in bilateral radiographs is also instructive for patients. Knowing that the contralateral knee shows the same radiographic changes, or even more, helps them understand that the structural factors as imaged do not dictate symptoms. More advanced or extensive imaging is not needed unless appropriate and patient therapy reaches a stalemate.

Bone Scans

In recalcitrant patients with persistent pain, a bone scan provides sensitive imaging of osseous metabolic activity and thereby clarifies the etiology of the pain. A negative scan rules out the bone as a significant cause, freeing the clinician to concentrate solely on the soft tissues. In a way that MRI can miss, a positive bone scan identifies specific regions that have lost osseous homeostasis and are being overloaded. Microscopically, these regions’ changes are very similar to the abnormal bone remodeling that occurs in early-stage stress fractures. Whether focal or diffuse, a positive bone scan means symptoms likely will take longer to reverse than is the case with a negative scan. Often, the stark findings of a positive bone scan can grab the patient’s attention and improve understanding and compliance. Focal inferior pole uptake is the most difficult pattern to reverse, perhaps because it may represent the most extreme biomechanical environment of the patellofemoral joint. In Dr. Dye’s experience, patients with this pattern may often require drilling of the inferior pole to achieve restoration of tissue homeostasis.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

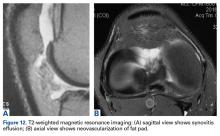

MRI can be useful, though scans are commonly read as normal. In some cases, MRI evidence of tendinopathy and other intra-articular pathology can direct both operative and nonoperative treatment of AKP. Carefully look for evidence of soft-tissue impingement—such as mild synovial swelling, low-grade effusion, and neovascularization of the fat pad—as in many cases it exists, and has been missed by the radiologist (Figures 12A, 12B).

View the images yourself and, if necessary, in consultation with a radiologist.When Surgery Is Needed: General Principles

Although the majority of patients with AKP do not need surgery, some do. Think of surgery as a tool used to create an environment in which homeostasis may be restored. Arthroscopy and meticulous débridement may be used to treat recalcitrant focal synovitis or fat-pad hypertrophy—or focal chondral pathology (eg, unstable flap of articular cartilage) that has produced mechanical symptoms with secondary inflammation. A well-localized area of patellar tendinosis may respond to either arthroscopic or open débridement. A true mechanical alignment abnormality may produce focal overload to such a degree that the most complete nonoperative programs cannot overcome the loss of homeostasis. In such a case, imaging studies that precisely document overloaded areas and associated malalignment must make sense given the clinical picture, and then must be used in developing a rational surgical plan for unloading bone and soft-tissue pathology to create a mechanical and biological environment for healing and return to homeostasis. At times, the articular damage may be so severe that patellofemoral arthroplasty is the best choice. The exact indications for these procedures are well described elsewhere.13

Surgery for Patients With PFP Caused by Recalcitrant Synovitis

As this type of surgery is not often covered in the literature, we offer some treatment pearls here. Arthroscopy for persistent focal synovitis should not be approached lightly; though the mechanics of removing abnormal inflamed synovial tissue may be straightforward, perioperative management and long-term postoperative management are not. The patient must be mentally prepared for the process; blood-thinning agents, fish oil, and turmeric must be discontinued; and hemostasis must be meticulous (Figures 13A-13C).

A substantial hemarthrosis, which can be very painful, represents a major setback in homeostasis restoration. To ensure there is no active bleeding immediately after surgery, Dr. Dye keeps a small drain in the patient’s knee for at least a couple of hours. In a patient with active bleeding, the drain can stay overnight; if there is no bleeding, the drain can be removed before the patient is discharged. The patient must be prepared to take it easy for a while after the procedure to allow cellular repopulation of the raw surface created when the inflamed synovium was removed. As complete restoration of joint homeostasis can take several months, the patient and surgeon must remain patient. Ice, NSAIDs if needed, and rehabilitation within the EOF ensue.