Take-Home Points

- ML lesions usually occur with high-energy injuries and have been reported in wrestlers, football players, and other athlete populations.

- Encapsulated fat necrosis lesions are usually attributable to trauma and disruption of the blood supply in the subcutaneous area, which occurs with ML lesions.

- Encapsulated fat necrosis lesions are rare; only 65 have been reported.

- Encapsulated fat necrosis lesions are characterized by massive fat necrosis encapsulated by fibrous tissue.

- Most are small and asymptomatic; however, in some cases, athletes can develop symptoms from frequent impacts to the region where the lesions are located.

What would become known as the Morel-Lavallée (ML) lesion was first reported in 1853 by French physician Maurice Morel-Lavallée. He described a proximal thigh soft-tissue injury that resulted in a hemolymphatic collection between superficial fascial planes. Deforming forces of pressure and shear result in an internal degloving injury in which subcutaneous tissue is stripped from the fascia and replaced with a hematoma or, less commonly, necrotic fat.1-4 The injury can take several weeks to heal. Up to one-third of such injuries are initially missed because of the initial ecchymosis covering the injured area.5

ML lesions usually occur with high-energy injuries and have been reported in wrestlers,6 football players,7-9 and other athlete populations. ML lesions usually occur about the knee, the site of the sheer mechanism in these athletes’ sports. Tejwani and colleagues9 reported on 24 National Football League (NFL) players (27 knees). These elite athletes typically were able to return to practice and game play long before complete resolution of their lesions.

Nodular cystic fat necrosis was first described by Przyjemski and Schuster10 in 1977. The terms encapsulated fat necrosis lesions and mobile encapsulated lipomas11 were introduced later. Clinically, these entities usually present as lesions on the lower limbs of young men and middle-aged women and can range in size from 1 mm to 35 mm. Most of these lesions are mobile.11 They are usually attributable to trauma and disruption of the blood supply in the subcutaneous area, which occurs with ML lesions. Trauma accounts for the usual occurrence in the lower extremities, though only 40% of patients recall a precipitating event.12 Histologically, these lesions are characterized by massive fat necrosis encapsulated by fibrous tissue.13In this article, we report the case of a professional ice hockey player who presented with an ML lesion of the hip and then developed a symptomatic encapsulated fat necrosis lesion that required surgical removal. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an encapsulated fat necrosis lesion caused by an ML lesion in an athlete. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 21-year-old professional hockey player presented with a history of pain from a mass on his right hip. He first noticed the lesion, just lateral to the greater trochanter, about 3 years earlier. The mass appeared after he sustained a shearing-type injury to the lateral aspect of the hip. At the time, there was significant swelling along the lateral aspect, with ecchymosis that resolved over 2 months. The mass, diagnosed as an ML lesion, resolved with nonoperative treatment. However, in the area where the swelling had occurred, a hard mobile mass remained. At times, this mass became painful when direct pressure was applied, as when he hit the boards while playing hockey, or when he lay on his right side or used a roller in the training room. He rated the pain as a 4 on a 1-to-10 scale and said the mass was mobile and had not changed in size or consistency.

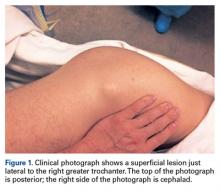

Physical examination revealed a palpable mass over the lateral aspect of the hip, over the greater trochanter. The mass, about 3 cm in diameter (Figure 1), was mobile in a subcutaneous pocket, consistent with an old ML lesion.

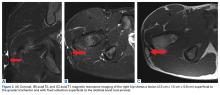

There was tenderness on direct palpation of the mass but no skin changes over it. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a discrete fatty mass 2.5 cm × 1.5 cm × 0.8 cm in size (Figures 2A-2C). The subcutaneous mass lay over the iliotibial band and was completely surrounded by a fluid collection.Options discussed with the patient included use of ice, activity modification, and use of protective padded equipment. As the patient had tried these treatments before and was still intermittently having pain with direct pressure, he asked for surgical removal of the mass.

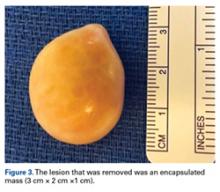

For the surgery, the patient was positioned in the lateral decubitus position with his right hip facing up. The right hip and thigh were prepared and draped in sterile fashion. An incision 4 cm in length was made directly over the mass, along the lateral aspect of the hip, over the greater trochanter. The incision was taken through skin and subcutaneous tissue down to the deep fascia. The fascia was incised longitudinally in line with the overlying skin incision. As soon as the incision was made through the fascia, the mass was easily seen. The 3-cm × 2-cm × 1-cm mass was free, not attached to any underlying soft tissue (Figure 3).

The mass was removed, and a specimen was sent to pathology, which reported an encapsulated mass of fat necrosis. This finding is consistent with the diagnosis of an encapsulated fat necrosis lesion.