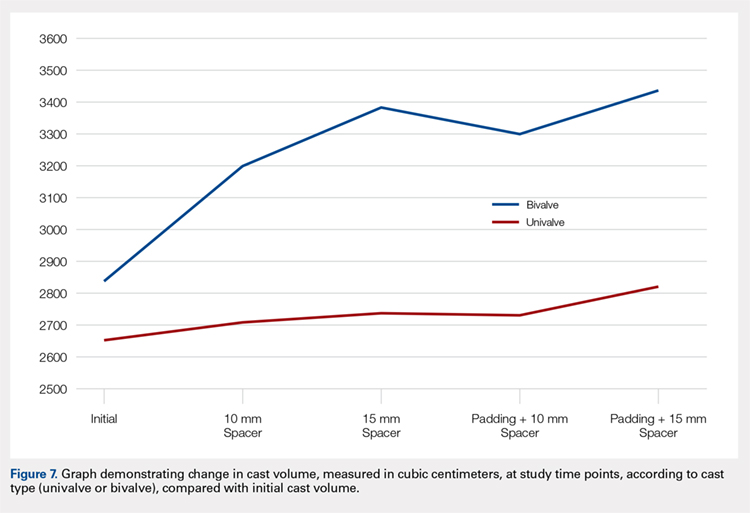

The summary of volumetric changes is listed in Table 2. The decrease in pressure correlated with an associated increase in cast volume, as demonstrated in Figure 7. The degree of increase in cast volume was more pronounced in the bivalve group (P < .001). The volume increased in the 15-mm group compared with the 10-mm group for both groups (P < .001) and increased for each spacer group with the release of the underlying padding (P < .05).

Table 2. Volumetric Data

Cast | Average Volumetric change (cm3) | Standard Deviation |

Univalve | ||

10-mm Spacer | 175.6 | 65.4 |

15-mm Spacer | 269.4 | 73.3 |

Padding and 10-mm Spacer | 202.3 | 62.5 |

Padding and 15-mm Spacer | 294.1 | 66.9 |

Bivalve | ||

10-mm Spacer | 363.7 | 67.2 |

15-mm Spacer | 540.9 | 85.7 |

Padding and 10-mm Spacer | 457.2 | 97.9 |

Padding and 15-mm Spacer | 599.3 | 84.2 |

Analysis of the planned comparisons demonstrated no significant difference between the bivalve with elastic wrap and univalve with 10-mm spacer subgroups (t [28] = 1.85, P = .075, d = .68). In comparing the bivalve with elastic wrap group with the univalve and 15-mm spacer subgroup, the univalve group showed significantly lower pressures [t [28] = 6.32, P < .001, d = .2.31).

DISCUSSION

Valving of circumferential casting is a well-established technique to minimize potential pressure-related complications. Previous studies have demonstrated that univalving techniques produce a 65% reduction in cast pressure, whereas bivalving produces an 80% decrease.6,7,9 Our results showed comparable pressure reductions of 75% with bivalving and 60% with univalving. The type of cast padding has been shown to have a significant effect on the cast pressure, favoring lower pressures with cotton padding over synthetic and waterproof padding, which, when released, can provide an additional 10% pressure reduction.6,7

Although bivalving techniques are superior in pressure reduction, the reduction comes at the cost of the cast’s structural integrity. Crickard and colleagues10 performed a biomechanical assessment of the structural integrity by 3-point bending of casts following univalve and bivalve compared with an intact cast. The authors found that valving resulted in a significant decrease in the casts’ bending stiffness and load to failure, with bivalved casts demonstrating a significantly lower load to failure than univalved casts. One technique that has been used to enhance the pressure reduction in univalved casting techniques is the application of a cast spacer. Rang and colleagues11 recommended this technique as part of a graded cast-splitting approach for the treatment of children’s fractures. This technique was applied to fractures with only modest anticipated swelling, which accounted for approximately 95% of casts applied in their children’s hospital. Our results support the use of cast spacers, demonstrating significant reduction in cast pressure in both univalve and bivalve techniques. Additionally, we found that a univalved cast with a 10-mm cast spacer provided pressure reduction similar to that of a bivalved cast.

The theory behind the application of cast spacers is that a split fiberglass cast will not remain open unless held in position.11 Holding the cast open is less of a restraint to pressure reduction in bivalving techniques, because the split cast no longer has the contralateral intact hinge point to resist cast opening, demonstrated in the compromise in structural integrity seen with this technique.10 By maintaining the split cast in an opened position, the effective volume of the cast is increased, which allows for the reduction in cast pressure. This is demonstrated in our results indicating an increase in estimated cast volume with an associated incremental reduction in cast pressure with the application of incrementally sized cast spacers. Although this technique does have the potential for skin irritation caused by cast expansion, as well as local swelling at the cast window location, it is a cost-effective treatment method compared with overwrapping a bivalved cast, $1.55 for 1 cast spacer vs an estimated $200 for a forearm cast application.

This study is not without its limitations. Our model does not account for the soft tissue injury associated with forearm fractures. However, by using human volunteers, we were able to include the viscoelastic properties that are omitted with nonliving models, and our results do align with those of previous investigations regarding pressure change following valving. We did not incorporate a 3-point molding technique commonly used with reduction and casting of acute forearm fractures, owing to the lack of a standardized method for applying the mold to healthy volunteers. Although molding is necessary for most fractures in which valving is considered, we believe our data still provide valuable information. Additionally, valving of circumferential casts has not been shown, prospectively, to result in a reduction of cast-related compartment syndrome, maintenance of reduction, or need for surgery.12,13 However, these results are reflective of reliable patients who completed the requisite follow-up care necessary for inclusion in a randomized controlled trial and may be applicable to unreliable patients or patient situations, a setting in which the compromise in cast structural integrity may be unacceptable.

CONCLUSION

We demonstrated that incorporating cast spacers into valved long-arm casts provides pressure reduction comparable to that achieved with the use of an elastic wrap. The addition of a 10-mm cast spacer to a univalved long-arm cast provides pressure reduction equivalent to that of a bivalved cast secured with an elastic wrap. A univalved cast secured with a cast spacer is a viable option for treatment of displaced pediatric forearm fractures, without compromising the cast’s structural integrity as required with bivalved techniques.

This paper will be judged for the Resident Writer’s Award.