Epidemiology

The several studies of lower extremity injuries sustained while skiing and snowboarding have differed markedly with respect to patient demographics. Kim and colleagues1 compared snowboarding and skiing injuries over 18 seasons at a Vermont ski resort and found that the injury rate, assessed as mean number of days between injuries, was 400 for snowboarders and 345 for skiers. However, most snowboarding injuries were wrist injuries and generally of the upper extremity, whereas skiing injuries were mainly lower extremity injuries. Overall, young and inexperienced snowboarders had the highest injury rate. In a study on skiing and snowboarding injuries through 4 Utah seasons, Wasden and colleagues2 found that mean age at injury was 41 years for skiers and 23 years for snowboarders. This corroborates the finding from several studies1-3 that snowboarders tend to be younger. Snowboarding is a newer sport with many beginners. However, Ishimaru and colleagues4 found that lower extremity injuries may be associated with experienced snowboarders, who may be prone to take more risks and tackle more challenging slopes. Experienced snowboarders are also likely to sustain lower extremity injuries from falling, because of their risk-taking behavior.5

Although upper extremity injuries account for most snowboarding injuries, lower extremity injuries are a significant issue.6 Modern equipment and more challenging slopes have allowed snowboarders to attain great speeds going down slopes—leading to a surge in lower extremity injuries.7 Lower extremity injuries sustained during snowboarding are more likely to be on the leading side4; the ankle is the most frequent fracture site. Unlike snowboard equipment, modern ski equipment, including new boots and binding systems, is designed to reduce ankle injuries and lower leg fractures.6 The decline in foot, ankle, and tibia fractures can be attributed to taller and stiffer boots, which offer the lower extremities more protection.8

Mechanism of Injury

Talus Fractures

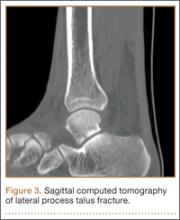

An increasingly common injury among snowboarders is a fracture of the lateral process of the talus; this injury accounts for 32% of snowboarders’ ankle fractures.6 The lateral process of the talus—wedge-shaped and covered in articular cartilage—is involved in the subtalar and ankle joints.9 A fracture here is often misdiagnosed as an ankle sprain (Figures 1–3).6,9,10 The exact mechanism of injury remains controversial, and several biomechanical factors seem to be involved. Funk and colleagues11 conducted a cadaveric study and concluded that eversion of an axially loaded, dorsiflexed ankle may be the primary injury mechanism for fracture. Furthermore, snowboarders have their feet in a position perpendicular to the board, and a fall parallel to the board could increase the eversion force on the ankle of the leading leg. Valderrabano and colleagues9 conducted a clinical study of 26 patients who sustained this injury from snowboarding. All the patients reported they had felt an axial impact from falling, jumping, or unexpectedly hitting a ground object, and 80% reported a rotational movement in the lower leg during the impact. The authors concluded that axial loading and dorsiflexion were not the only factors involved in lateral process talus fractures, and an external moment is necessary to cause this injury from a forward fall.9

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries

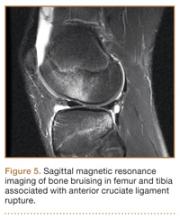

Although snowboarders’ lower extremity injuries are primarily ankle injuries, snowboarders are also at risk for serious knee issues when landing from jumps. In skiers, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries have 5 well-established mechanisms, all involving separation of the feet and a twisting force in the knee (Figures 4, 5): boot-induced anterior drawer mechanism, phantom-foot mechanism, valgus-external rotation, forceful quadriceps muscle contraction, and a combination of internal rotation and extension.8,12 A valgus–external rotation mechanism of knee injury occurs when external rotation of the tibia results from the skier catching the inside edge of the front of the ski. A valgus force acts on the knee as the lower leg is abducted during forward momentum. The torque created on the knee joint is amplified by the length of the knee and commonly results in an ACL injury or medial collateral ligament injury.6 Reports indicate that the phantom-foot mechanism is the most common mechanism of ACL injury among skiers.6,13,14 In this situation, internal rotation of the knee results when an off-balance skier falls backward, which causes the knee to hyperflex. The skier catches an inside edge on the snow, which creates a torque that rotates the tibia relative to the femur and results in injury to the ACL.6,14 A boot-induced anterior drawer mechanism occurs during a landing, when the tail of the ski lands first and in an off-balance position, resulting in a load transmitted through the skis to the skier; this load causes an anterior drawer of the ski boot and tibia relative to the femur, straining the ACL and causing ACL rupture.6,13,14 In the forceful quadriceps muscle contraction mechanism of ACL injury, a forceful quadriceps contraction occurs after a jump to prevent a backward fall. With the knee in flexion, this quadriceps contraction causes an anterior translation of the tibia, resulting in ACL rupture.13,14