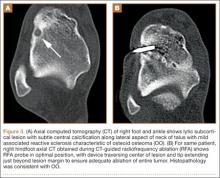

Before 1998, all foot and ankle OOs (n = 6) were treated with surgical excision. After RFA was introduced at our institution, 3 foot and ankle OOs (43%) were treated with RFA (Figures 3A, 3B), and 4 (57%) were treated with surgical curettage (Figure 4). The 4 surgical patients’ OOs were not amenable to RFA primarily because of anatomical considerations: In 2 patients, the OO was too near the articular surface; in another patient, the lesion was in intimate contact with a neurovascular bundle; in the fourth patient, the lesion was amenable to RFA, but the patient’s family selected surgical curettage instead.

Mean tumor nidus size was 7.5 mm (range, 3-12 mm). Bone graft was placed in 3 patients (30%), and surgical hardware was placed to repair a medial malleolar osteotomy in 1 (10%) of the patients treated surgically. The majority of the lesions (8) were in cancellous bone in a subcortical location. Three lesions were intracortical. Seven lesions were intra-articular, and 4 were extra-articular. Two patients did not have radiographic images available for review.

One patient had a recurrence of OO and underwent a repeat procedure 4 months after the initial one. At final follow-up, on average 1 year after the initial procedure (range, 2 weeks–3 years), there were no reported recurrences. One patient underwent a procedure to remove painful hardware that had been implanted, during the primary procedure, to repair the medial malleolar osteotomy used to access the lesion. Recurrence rates for RFA (n = 1) and surgical excision (n = 0) were similar.

Discussion

OOs are relatively common bone tumors that account for about 13% of all benign bone tumors.4,13 OOs typically occur in children or young adults—the majority of patients are younger than 25 years—and are 3 times more common in males than females.4,13 Our findings for all patients with a lower extremity OO are consistent with those previously reported: male predominance (75 males, 42 females) and mean age under 25 years (mean age, 18.7 years). In patients with foot or ankle OO, male predominance was substantially greater (12 males, 1 female), though mean age at presentation (20.1 years) was similar.

Local pain is the most common complaint in patients who present with OO.4,13 Pain is thought to be generated by a combination of multiple nerve endings in the tumor14 and prostaglandin production by the tumor nidus (prostaglandins E2 and I2)3 causing an inflammatory reaction.6 In accord with previous studies,4 localized foot or ankle pain was the most common complaint at time of presentation in our study; 100% of our patients had it. All but 1 patient (92%) in our study described pain that was worse at night and relieved by aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Pain reduction after NSAID use was observed in 92% (12/13) of our patients as well; the 1 patient who did not report pain relief had not used NSAIDs before being evaluated at our institution. Our patient population reported night pain and pain relief with NSAID use more frequently than patients in other studies did.15,16

The bone most commonly involved in our patients’ foot and ankle OOs was the talus (5/13, 38%). This is in accord with 1 study1 but contradicts another, in which the most common foot and ankle site was the calcaneus.17 The site of the lesion in the bone can be subclassified as cortical, cancellous, or subperiosteal.11,12 Cortical OOs were the most common in our study, but in previous reports the most common were subperiosteal and cancellous.1,11 As all our OOs were cortical, we classified them (on the basis of the relationship of the nidus to the cortex) as intracortical, periosteal, or subcortical (endosteal) instead of subperiosteal or cancellous. Three of our patients’ lesions were intracortical, 8 were subcortical, and 2 patients did not have radiographs available for review at the time of the study.

Although the classic clinical presentation of OO is often sufficient to raise suspicion for the diagnosis, imaging studies play a crucial role in accurate diagnosis. An accurate diagnosis of OO in the long bones can be made if the lesion presents with characteristic imaging features, as a small round lytic lesion with associated cortical thickening, medullary sclerosis, and chronic benign periosteal new bone formation.15 In some cases, however, the nidus may be obscured by the extensive associated reactive changes on the radiographs, and therefore the differential diagnosis may also include stress fracture, Brodie abscess, or even osteosarcoma. High-resolution CT is the imaging modality of choice for accurate diagnosis of OO, and it often plays an instrumental role in making the diagnosis and excluding other diagnostic possibilities.15-17