Fat embolism syndrome (FES) is a rare complication reported primarily after long bone fractures, with an incidence of 0.3% to 2.2%.1-3 It is most commonly caused by trauma and is thought to result from movement of bone fragments or to occur during intramedullary reaming.1 Both of these factors lead to a distortion of the bone marrow cavity, allowing marrow and fat to enter the circulatory system.1

Although the true pathophysiology remains poorly understood, it is possible that, once in systemic circulation, the fat particles become lodged in the vascular system, inciting an inflammatory response, leading to organ dysfunction via mechanical or biochemical processes.4 Typically, the diagnosis is made after clinical features are observed, including hypoxemia, petechial rash, and cerebral signs not related to a head injury or other conditions.5,6

Although FES is an uncommon complication after traumatic injuries, mortality after FES in a recent study was reported to be 10%.1 FES is most commonly seen after fractures of the femur and tibia, although cases have been described involving fractures of the radius, ulna, and humerus.1,3 We present an atypical case of cerebral FES after multiple fractures of the foot; to our knowledge, such a case has not been reported in the English-language literature. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man was hunting with his son when he was accidentally shot in the left foot with a .270-caliber rifle bullet at close range. The patient sought care at a local hospital and, in the ensuing 3 hours, his mentation appeared normal. He reported pain and numbness distal to the injury in the tibial nerve distribution, but he remained vascularly intact, alert, and oriented. He was given 7 mg of hydromorphone hydrochloride over 2 hours for pain control and was transferred to our hospital via ambulance approximately 6 hours after injury. Upon arrival, he was noted to be extremely sedated and obtunded, responding only to pain with spontaneous eye opening. He was unable to follow commands. He was given

1.2 mg of naloxone intravenously to reverse what was presumed to be acute opioid intoxication; however, his mental status did not improve.

On examination, the patient was noted to have a small entrance wound through the Achilles tendon (Figures 1A, 1B) and an exit wound on the plantar aspect of the foot near the heads of the first and second metatarsals (Figures 1C, 1D) with minimal bleeding and no gross contamination. There was significant edema on the medial and proximal aspects of the left foot, 3+ dorsalis pedis pulse, and a capillary refill of 4 seconds. Radiographs showed traumatic fracture deformities of the calcaneus, navicular, medial cuneiform, and first and second metatarsal bases, as well as an intra-articular fracture deformity of the left talus extending to the talar dome (Figures 2A-2C). Neurologic examination could not be reliably obtained because of the patient’s mental status. He was determined to be unstable for immediate surgery, and his left leg was splinted pending neurologic evaluation.

The patient’s oxygen saturation was 94%, and his temperature was 38.2°C (100.76°F). Although his heart rate was in the 90s upon arrival, he became tachycardic over the next 4 hours, with heart rate ranging from the 110s to 130s; he remained tachycardic for approximately 72 hours. Laboratory values upon arrival showed a hemoglobin value of 12.8 g/dL and platelets of 249,000/μL. He developed anemia and thrombocytopenia within 72 hours of the injury, with a low of 6.6 g/dL and 88,000/μL, respectively, by postinjury day 4. Computed tomography of the head, electroencephalography, urine drug screen, and lumbar puncture were unremarkable. The patient never became hypoxemic. Within 14 hours after injury, he was completely comatose with extensor posturing. In the intensive care unit (ICU), the patient was intubated for airway protection.

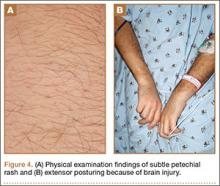

The next day, the patient underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, which showed innumerable tiny infarcts throughout cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, and brainstem in a characteristic “starfield” pattern on T2-weighted images (Figure 3). This was radiographically consistent with fat emboli related to the left lower extremity gunshot wound. An echocardiogram showed small right-to-left shunt and a possible intrapulmonary shunt, although this was never confirmed. The echocardiogram was technically challenging secondary to his persistent tachycardia. He also developed a subtle petechial rash (Figure 4A).

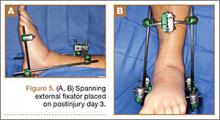

The patient underwent percutaneous gastrostomy-tube placement for nutrition on postinjury day 4 and remained intubated, unable to protect his airway, and nonresponsive with extensor posturing (Figure 4B). He was also taken to the operating room for spanning external fixator placement on postinjury day 3 to restore calcaneal height and length as well as foot stability (Figures 5A, 5B).