User login

Coming acne drugs might particularly benefit skin of color patients

NEW YORK – The most recently approved therapy for acne, sarecycline, as well as several agents in late stages of clinical testing, might represent a particular advance for treating black patients or others with darker skin tones due to a reduced risk of irritation, according to a review presented at the Skin of Color Update 2019.

a complication many consider worse than the acne itself, according to Andrew Alexis, MD, director of the Skin of Color Center and chair of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, New York.

“The importance of PIH is that it alters our endpoint in patients of color. Not only are we treating the pustules, comedones, and other classic features of acne, but we have to treat all the way through to the resolution of the PIH if we want a satisfied patient,” he said.

There are data to back this up. In one of the surveys cited by Dr. Alexis, 42% of nonwhite patients identified resolution of PIH as the most important goal in the treatment of their acne.

As in those with light skin, acute acne lesions in darker skin can resolve relatively rapidly after initiating an effective regimen that includes established therapies such as retinoids or antibiotics. However, PIH, once it develops, might take 6-12 months to resolve, according to Dr. Alexis, who is a professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“You have to keep in mind the subclinical inflammation, which can be a slow burning process beneath the surface of the skin,” he said. He cited a biopsy study that demonstrated inflammation even in nonlesional skin of black patients with acne.

Because of the slow reversal of PIH, it is imperative in skin of color patients to employ therapies with the least risk of exacerbating PIH. While this includes judicious use of currently available agents, Dr. Alexis believes that newer agents might have a larger therapeutic window, reducing the potential for inflammation at effective doses.

This advantage has yet to be confirmed in head-to-head studies, but Dr. Alexis is optimistic. In the case of sarecycline, which became the first antibiotic approved specifically for acne when it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018, about 20% of those included in the phase 3 registration trial were nonwhite, he said.

The results were “impressive” regardless of skin color in the phase 3 study, according to Dr. Alexis. He conceded that this is not the only antibiotic with anti-inflammatory activity, but he suggested that a high degree of efficacy might be relevant for early acne control and a reduced risk of PIH.

The same can be said for trifarotene, a novel topical retinoid that was associated with highly significant reductions in both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts in a recently published phase 3 trial (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jun;80[6]:1691-9). According to Dr. Alexis, the impact of this therapy on PIH has not been specifically tested, but he expects those data to be forthcoming.

A new 0.045% lotion formulation of tazarotene might also widen the therapeutic window relative to current tazarotene formulations based on clinical trials he cited. Despite a concentration that is about half that of the currently available tazarotene cream, the efficacy of this product appeared to be at least as good “without the baggage of a greater potential for irritation,” he said.

After “a few years of drought” regarding new options for treatment of acne, these are not the only promising agents in clinical trials, according to Dr. Alexis. If these agents prove to offer greater efficacy with less irritation, their increased clinical value might prove most meaningful to patients with darker skin.

“There is a delicate balance between maximizing efficacy without causing irritation that leads to PIH in patients with skin of color,” he cautioned. He is hopeful that the newer agents will make this balance easier to achieve.

Dr. Alexis has financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including many that market drugs for acne.

NEW YORK – The most recently approved therapy for acne, sarecycline, as well as several agents in late stages of clinical testing, might represent a particular advance for treating black patients or others with darker skin tones due to a reduced risk of irritation, according to a review presented at the Skin of Color Update 2019.

a complication many consider worse than the acne itself, according to Andrew Alexis, MD, director of the Skin of Color Center and chair of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, New York.

“The importance of PIH is that it alters our endpoint in patients of color. Not only are we treating the pustules, comedones, and other classic features of acne, but we have to treat all the way through to the resolution of the PIH if we want a satisfied patient,” he said.

There are data to back this up. In one of the surveys cited by Dr. Alexis, 42% of nonwhite patients identified resolution of PIH as the most important goal in the treatment of their acne.

As in those with light skin, acute acne lesions in darker skin can resolve relatively rapidly after initiating an effective regimen that includes established therapies such as retinoids or antibiotics. However, PIH, once it develops, might take 6-12 months to resolve, according to Dr. Alexis, who is a professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“You have to keep in mind the subclinical inflammation, which can be a slow burning process beneath the surface of the skin,” he said. He cited a biopsy study that demonstrated inflammation even in nonlesional skin of black patients with acne.

Because of the slow reversal of PIH, it is imperative in skin of color patients to employ therapies with the least risk of exacerbating PIH. While this includes judicious use of currently available agents, Dr. Alexis believes that newer agents might have a larger therapeutic window, reducing the potential for inflammation at effective doses.

This advantage has yet to be confirmed in head-to-head studies, but Dr. Alexis is optimistic. In the case of sarecycline, which became the first antibiotic approved specifically for acne when it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018, about 20% of those included in the phase 3 registration trial were nonwhite, he said.

The results were “impressive” regardless of skin color in the phase 3 study, according to Dr. Alexis. He conceded that this is not the only antibiotic with anti-inflammatory activity, but he suggested that a high degree of efficacy might be relevant for early acne control and a reduced risk of PIH.

The same can be said for trifarotene, a novel topical retinoid that was associated with highly significant reductions in both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts in a recently published phase 3 trial (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jun;80[6]:1691-9). According to Dr. Alexis, the impact of this therapy on PIH has not been specifically tested, but he expects those data to be forthcoming.

A new 0.045% lotion formulation of tazarotene might also widen the therapeutic window relative to current tazarotene formulations based on clinical trials he cited. Despite a concentration that is about half that of the currently available tazarotene cream, the efficacy of this product appeared to be at least as good “without the baggage of a greater potential for irritation,” he said.

After “a few years of drought” regarding new options for treatment of acne, these are not the only promising agents in clinical trials, according to Dr. Alexis. If these agents prove to offer greater efficacy with less irritation, their increased clinical value might prove most meaningful to patients with darker skin.

“There is a delicate balance between maximizing efficacy without causing irritation that leads to PIH in patients with skin of color,” he cautioned. He is hopeful that the newer agents will make this balance easier to achieve.

Dr. Alexis has financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including many that market drugs for acne.

NEW YORK – The most recently approved therapy for acne, sarecycline, as well as several agents in late stages of clinical testing, might represent a particular advance for treating black patients or others with darker skin tones due to a reduced risk of irritation, according to a review presented at the Skin of Color Update 2019.

a complication many consider worse than the acne itself, according to Andrew Alexis, MD, director of the Skin of Color Center and chair of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s, New York.

“The importance of PIH is that it alters our endpoint in patients of color. Not only are we treating the pustules, comedones, and other classic features of acne, but we have to treat all the way through to the resolution of the PIH if we want a satisfied patient,” he said.

There are data to back this up. In one of the surveys cited by Dr. Alexis, 42% of nonwhite patients identified resolution of PIH as the most important goal in the treatment of their acne.

As in those with light skin, acute acne lesions in darker skin can resolve relatively rapidly after initiating an effective regimen that includes established therapies such as retinoids or antibiotics. However, PIH, once it develops, might take 6-12 months to resolve, according to Dr. Alexis, who is a professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York.

“You have to keep in mind the subclinical inflammation, which can be a slow burning process beneath the surface of the skin,” he said. He cited a biopsy study that demonstrated inflammation even in nonlesional skin of black patients with acne.

Because of the slow reversal of PIH, it is imperative in skin of color patients to employ therapies with the least risk of exacerbating PIH. While this includes judicious use of currently available agents, Dr. Alexis believes that newer agents might have a larger therapeutic window, reducing the potential for inflammation at effective doses.

This advantage has yet to be confirmed in head-to-head studies, but Dr. Alexis is optimistic. In the case of sarecycline, which became the first antibiotic approved specifically for acne when it was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018, about 20% of those included in the phase 3 registration trial were nonwhite, he said.

The results were “impressive” regardless of skin color in the phase 3 study, according to Dr. Alexis. He conceded that this is not the only antibiotic with anti-inflammatory activity, but he suggested that a high degree of efficacy might be relevant for early acne control and a reduced risk of PIH.

The same can be said for trifarotene, a novel topical retinoid that was associated with highly significant reductions in both inflammatory and noninflammatory lesion counts in a recently published phase 3 trial (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jun;80[6]:1691-9). According to Dr. Alexis, the impact of this therapy on PIH has not been specifically tested, but he expects those data to be forthcoming.

A new 0.045% lotion formulation of tazarotene might also widen the therapeutic window relative to current tazarotene formulations based on clinical trials he cited. Despite a concentration that is about half that of the currently available tazarotene cream, the efficacy of this product appeared to be at least as good “without the baggage of a greater potential for irritation,” he said.

After “a few years of drought” regarding new options for treatment of acne, these are not the only promising agents in clinical trials, according to Dr. Alexis. If these agents prove to offer greater efficacy with less irritation, their increased clinical value might prove most meaningful to patients with darker skin.

“There is a delicate balance between maximizing efficacy without causing irritation that leads to PIH in patients with skin of color,” he cautioned. He is hopeful that the newer agents will make this balance easier to achieve.

Dr. Alexis has financial relationships with many pharmaceutical companies, including many that market drugs for acne.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SOC 2019

Monitoring Acne Patients on Oral Therapy: Survey of the Editorial Board

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis and Dermatology News Editorial Boards answered 5 questions on monitoring acne patients on oral therapy. Here’s what we found.

Do you check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne?

Half of dermatologists surveyed never check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne. For those who do check levels, 8% do it at baseline only, 8% at baseline and every 6 months, 23% at baseline and yearly, and 13% at baseline and for dosing changes.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Although some dermatologists are still checking for potassium levels in patients taking spironolactone for acne, there is a clear trend toward foregoing laboratory monitoring. This change was likely spurred by a retrospective study of healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne that found a hyperkalemia rate of 0.72%, which is practically equivalent to the 0.76% baseline rate of hyperkalemia in this age group. Furthermore, since repeat testing in 6 of 13 patients showed normal values, the original potassium measurements may have been erroneous. Based on this study, routine potassium monitoring is likely unnecessary for healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne (Plovanich et al). In another retrospective study of women aged 18 to 65 years taking spironolactone for acne, women aged 46 to 65 years had a significantly higher rate of hyperkalemia with spironolactone compared with women aged 18 to 45 years (2/12 women [16.7%] vs 1/112 women [<1%]; P=.0245). Based on this study, potassium monitoring may be indicated for women older than 45 years taking spironolactone for acne (Thiede et al).

Next page: Cholesterol levels

Do you monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

Almost two-thirds of dermatologists indicated that they monitor all cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, including low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, very low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides, but almost one-third monitor triglycerides only. Five percent do not monitor cholesterol levels.

Do you routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

More than 80% of dermatologists surveyed routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, with almost half (45%) at baseline and every 2 to 3 months. Eight percent check levels at baseline only, 28% at baseline and monthly, and 3% at baseline and end of therapy. Eighteen percent indicated they do not routinely monitor cholesterol levels.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

In this survey, dermatologists most often check cholesterol levels at baseline and then every 2 to 3 months, with most monitoring all cholesterol types. Elevations in cholesterol are by far the most common laboratory abnormality seen with isotretinoin therapy. In a retrospective study of 515 patients undergoing isotretinoin treatment of acne, mild to moderate triglyceride elevations were seen in 23.5% of patients (Hansen et al). At least in part, these elevations are likely due to the fact the levels were not drawn during fasting. Keep in mind that triglyceride-induced pancreatitis due to isotretinoin is remarkably rare, so monthly screening for triglycerides is likely not warranted. It is reasonable to monitor triglyceride levels during isotretinoin dose adjustments and for patients whose values are trending upward.

Next page: Monitoring CBC

Do you routinely monitor complete blood cell count (CBC) in patients taking isotretinoin?

More than half (55%) of dermatologists surveyed routinely monitor complete blood cell (CBC) counts in patients taking isotretinoin, while 45% do not. Of those who do monitor CBC, 13% do so at baseline only, 26% at baseline and monthly, 13% at baseline only and every 2 to 3 months, and only 3% at baseline and end of therapy.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Slightly more than half of dermatologists in this survey are obtaining CBC for their patients taking isotretinoin for acne and many of those are performing the test at baseline and monthly. Multiple studies as well as American Academy of Dermatology guidelines have substantiated that routine CBC monitoring is unwarranted in healthy patients, as abnormal values usually resolve or remain stable with therapy (American Academy of Dermatology, Isotretinoin: Recommendations). Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider foregoing CBC testing or obtaining just a baseline CBC in healthy patients being treated with isotretinoin.

Next page: Pregnancy testing

Which pregnancy test do you perform on female patients taking isotretinoin?

More than 40% of dermatologists surveyed use the urine β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) pregnancy test for female patients taking isotretinoin, while 30% use the serum B-hCG test; 28% indicated that they use both tests.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The iPLEDGE program was implemented in 2006 to avoid fetal exposure to isotretinoin and requires pregnancy testing (urine or serum) for females of childbearing potential taking isotretinoin. In a study of pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin reported to the US Food and Drug Administration, 6740 total pregnancies were reported from 1997 to 2017. The rate peaked with 768 pregnancies in 2006 and then decreased. Because several hundred pregnancies in women taking isotretinoin have been reported yearly in the last 10 years, there is a clear need to have better systems in place and patient education to prevent fetal exposure to isotretinoin.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

I see lab monitoring as an opportunity to engage patients and families in co-directing their care (ie, practice patient- and family-centered care). Some families and patients like frequent monitoring and some want as few blood draws as possible. I do my best to make sure the decision includes components of the patients’ preferences, medical evidence and my best clinical judgement.—Craig Burkhart, MD, MS, MPH (Chapel Hill, North Caroline)

Being familiar with and following the standard of care guidelines for the individual oral therapies used in the treatment of acne is very important. However, it is equally as important to assure the individual patient (medical history, physical examination, social history, etc) is taken into consideration to determine if additional monitoring is required.—Fran E. Cook-Bolden, MD (New York, New York)

The trend seems to be towards less routine monitoring other than pregnancy. Baseline tests may pick out the occasional patient with comorbidities that would preclude or delay treatment, but the majority of patients may not need the repetitive and costly testing that we have done in the past.—Richard Glogau, MD (San Francisco, California)

I have loosened my lab monitoring with isotretinoin over the past few years. If a patient has normal lipid values, comprehensive panel and complete blood cell count for the first 3 months of tests, I skip labs until the end of therapy.—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

Interestingly, we focus quite a bit of attention on the risk of pregnancy with isotretinoin, and often don't focus enough on the risk with spironolactone. In our practice, we are careful to warn the patients on spironolactone about pregnancy prevention.—Stephen Stone, MD (Springfield, Illinois)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis and Dermatology News Editorial Board Members within the United States from May 5, 2019, to June 23, 2019. A total of 40 usable responses were received.

American Academy of Dermatology. Isotretinoin: recommendations. https://www.aad.org/practicecenter/quality/clinical-guidelines/acne/isotretinoin. Accessed August 20, 2019.

Hansen TJ, Lucking S, Miller JJ, et al. Standardized laboratory monitoring with use of isotretinoin in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:323-328.

Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

Thiede RM, Rastogi S, Nardone B, et al. Hyperkalemia in women with acne exposed to oral spironolactone: a retrospective study from the RADAR (Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports) program. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:155-157.

Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin [published online July 17, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1388.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis and Dermatology News Editorial Boards answered 5 questions on monitoring acne patients on oral therapy. Here’s what we found.

Do you check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne?

Half of dermatologists surveyed never check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne. For those who do check levels, 8% do it at baseline only, 8% at baseline and every 6 months, 23% at baseline and yearly, and 13% at baseline and for dosing changes.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Although some dermatologists are still checking for potassium levels in patients taking spironolactone for acne, there is a clear trend toward foregoing laboratory monitoring. This change was likely spurred by a retrospective study of healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne that found a hyperkalemia rate of 0.72%, which is practically equivalent to the 0.76% baseline rate of hyperkalemia in this age group. Furthermore, since repeat testing in 6 of 13 patients showed normal values, the original potassium measurements may have been erroneous. Based on this study, routine potassium monitoring is likely unnecessary for healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne (Plovanich et al). In another retrospective study of women aged 18 to 65 years taking spironolactone for acne, women aged 46 to 65 years had a significantly higher rate of hyperkalemia with spironolactone compared with women aged 18 to 45 years (2/12 women [16.7%] vs 1/112 women [<1%]; P=.0245). Based on this study, potassium monitoring may be indicated for women older than 45 years taking spironolactone for acne (Thiede et al).

Next page: Cholesterol levels

Do you monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

Almost two-thirds of dermatologists indicated that they monitor all cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, including low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, very low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides, but almost one-third monitor triglycerides only. Five percent do not monitor cholesterol levels.

Do you routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

More than 80% of dermatologists surveyed routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, with almost half (45%) at baseline and every 2 to 3 months. Eight percent check levels at baseline only, 28% at baseline and monthly, and 3% at baseline and end of therapy. Eighteen percent indicated they do not routinely monitor cholesterol levels.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

In this survey, dermatologists most often check cholesterol levels at baseline and then every 2 to 3 months, with most monitoring all cholesterol types. Elevations in cholesterol are by far the most common laboratory abnormality seen with isotretinoin therapy. In a retrospective study of 515 patients undergoing isotretinoin treatment of acne, mild to moderate triglyceride elevations were seen in 23.5% of patients (Hansen et al). At least in part, these elevations are likely due to the fact the levels were not drawn during fasting. Keep in mind that triglyceride-induced pancreatitis due to isotretinoin is remarkably rare, so monthly screening for triglycerides is likely not warranted. It is reasonable to monitor triglyceride levels during isotretinoin dose adjustments and for patients whose values are trending upward.

Next page: Monitoring CBC

Do you routinely monitor complete blood cell count (CBC) in patients taking isotretinoin?

More than half (55%) of dermatologists surveyed routinely monitor complete blood cell (CBC) counts in patients taking isotretinoin, while 45% do not. Of those who do monitor CBC, 13% do so at baseline only, 26% at baseline and monthly, 13% at baseline only and every 2 to 3 months, and only 3% at baseline and end of therapy.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Slightly more than half of dermatologists in this survey are obtaining CBC for their patients taking isotretinoin for acne and many of those are performing the test at baseline and monthly. Multiple studies as well as American Academy of Dermatology guidelines have substantiated that routine CBC monitoring is unwarranted in healthy patients, as abnormal values usually resolve or remain stable with therapy (American Academy of Dermatology, Isotretinoin: Recommendations). Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider foregoing CBC testing or obtaining just a baseline CBC in healthy patients being treated with isotretinoin.

Next page: Pregnancy testing

Which pregnancy test do you perform on female patients taking isotretinoin?

More than 40% of dermatologists surveyed use the urine β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) pregnancy test for female patients taking isotretinoin, while 30% use the serum B-hCG test; 28% indicated that they use both tests.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The iPLEDGE program was implemented in 2006 to avoid fetal exposure to isotretinoin and requires pregnancy testing (urine or serum) for females of childbearing potential taking isotretinoin. In a study of pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin reported to the US Food and Drug Administration, 6740 total pregnancies were reported from 1997 to 2017. The rate peaked with 768 pregnancies in 2006 and then decreased. Because several hundred pregnancies in women taking isotretinoin have been reported yearly in the last 10 years, there is a clear need to have better systems in place and patient education to prevent fetal exposure to isotretinoin.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

I see lab monitoring as an opportunity to engage patients and families in co-directing their care (ie, practice patient- and family-centered care). Some families and patients like frequent monitoring and some want as few blood draws as possible. I do my best to make sure the decision includes components of the patients’ preferences, medical evidence and my best clinical judgement.—Craig Burkhart, MD, MS, MPH (Chapel Hill, North Caroline)

Being familiar with and following the standard of care guidelines for the individual oral therapies used in the treatment of acne is very important. However, it is equally as important to assure the individual patient (medical history, physical examination, social history, etc) is taken into consideration to determine if additional monitoring is required.—Fran E. Cook-Bolden, MD (New York, New York)

The trend seems to be towards less routine monitoring other than pregnancy. Baseline tests may pick out the occasional patient with comorbidities that would preclude or delay treatment, but the majority of patients may not need the repetitive and costly testing that we have done in the past.—Richard Glogau, MD (San Francisco, California)

I have loosened my lab monitoring with isotretinoin over the past few years. If a patient has normal lipid values, comprehensive panel and complete blood cell count for the first 3 months of tests, I skip labs until the end of therapy.—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

Interestingly, we focus quite a bit of attention on the risk of pregnancy with isotretinoin, and often don't focus enough on the risk with spironolactone. In our practice, we are careful to warn the patients on spironolactone about pregnancy prevention.—Stephen Stone, MD (Springfield, Illinois)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis and Dermatology News Editorial Board Members within the United States from May 5, 2019, to June 23, 2019. A total of 40 usable responses were received.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists from the Cutis and Dermatology News Editorial Boards answered 5 questions on monitoring acne patients on oral therapy. Here’s what we found.

Do you check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne?

Half of dermatologists surveyed never check potassium levels for patients taking spironolactone for acne. For those who do check levels, 8% do it at baseline only, 8% at baseline and every 6 months, 23% at baseline and yearly, and 13% at baseline and for dosing changes.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Although some dermatologists are still checking for potassium levels in patients taking spironolactone for acne, there is a clear trend toward foregoing laboratory monitoring. This change was likely spurred by a retrospective study of healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne that found a hyperkalemia rate of 0.72%, which is practically equivalent to the 0.76% baseline rate of hyperkalemia in this age group. Furthermore, since repeat testing in 6 of 13 patients showed normal values, the original potassium measurements may have been erroneous. Based on this study, routine potassium monitoring is likely unnecessary for healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne (Plovanich et al). In another retrospective study of women aged 18 to 65 years taking spironolactone for acne, women aged 46 to 65 years had a significantly higher rate of hyperkalemia with spironolactone compared with women aged 18 to 45 years (2/12 women [16.7%] vs 1/112 women [<1%]; P=.0245). Based on this study, potassium monitoring may be indicated for women older than 45 years taking spironolactone for acne (Thiede et al).

Next page: Cholesterol levels

Do you monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

Almost two-thirds of dermatologists indicated that they monitor all cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, including low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, very low-density lipoprotein, and triglycerides, but almost one-third monitor triglycerides only. Five percent do not monitor cholesterol levels.

Do you routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin?

More than 80% of dermatologists surveyed routinely monitor cholesterol levels in patients taking isotretinoin, with almost half (45%) at baseline and every 2 to 3 months. Eight percent check levels at baseline only, 28% at baseline and monthly, and 3% at baseline and end of therapy. Eighteen percent indicated they do not routinely monitor cholesterol levels.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

In this survey, dermatologists most often check cholesterol levels at baseline and then every 2 to 3 months, with most monitoring all cholesterol types. Elevations in cholesterol are by far the most common laboratory abnormality seen with isotretinoin therapy. In a retrospective study of 515 patients undergoing isotretinoin treatment of acne, mild to moderate triglyceride elevations were seen in 23.5% of patients (Hansen et al). At least in part, these elevations are likely due to the fact the levels were not drawn during fasting. Keep in mind that triglyceride-induced pancreatitis due to isotretinoin is remarkably rare, so monthly screening for triglycerides is likely not warranted. It is reasonable to monitor triglyceride levels during isotretinoin dose adjustments and for patients whose values are trending upward.

Next page: Monitoring CBC

Do you routinely monitor complete blood cell count (CBC) in patients taking isotretinoin?

More than half (55%) of dermatologists surveyed routinely monitor complete blood cell (CBC) counts in patients taking isotretinoin, while 45% do not. Of those who do monitor CBC, 13% do so at baseline only, 26% at baseline and monthly, 13% at baseline only and every 2 to 3 months, and only 3% at baseline and end of therapy.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

Slightly more than half of dermatologists in this survey are obtaining CBC for their patients taking isotretinoin for acne and many of those are performing the test at baseline and monthly. Multiple studies as well as American Academy of Dermatology guidelines have substantiated that routine CBC monitoring is unwarranted in healthy patients, as abnormal values usually resolve or remain stable with therapy (American Academy of Dermatology, Isotretinoin: Recommendations). Therefore, it is worthwhile to consider foregoing CBC testing or obtaining just a baseline CBC in healthy patients being treated with isotretinoin.

Next page: Pregnancy testing

Which pregnancy test do you perform on female patients taking isotretinoin?

More than 40% of dermatologists surveyed use the urine β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) pregnancy test for female patients taking isotretinoin, while 30% use the serum B-hCG test; 28% indicated that they use both tests.

Expert Commentary

Provided by Shari R. Lipner, MD, PhD (New York, New York)

The iPLEDGE program was implemented in 2006 to avoid fetal exposure to isotretinoin and requires pregnancy testing (urine or serum) for females of childbearing potential taking isotretinoin. In a study of pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin reported to the US Food and Drug Administration, 6740 total pregnancies were reported from 1997 to 2017. The rate peaked with 768 pregnancies in 2006 and then decreased. Because several hundred pregnancies in women taking isotretinoin have been reported yearly in the last 10 years, there is a clear need to have better systems in place and patient education to prevent fetal exposure to isotretinoin.

Next page: More tips from derms

More Tips From Dermatologists

The dermatologists we polled had the following advice for their peers:

I see lab monitoring as an opportunity to engage patients and families in co-directing their care (ie, practice patient- and family-centered care). Some families and patients like frequent monitoring and some want as few blood draws as possible. I do my best to make sure the decision includes components of the patients’ preferences, medical evidence and my best clinical judgement.—Craig Burkhart, MD, MS, MPH (Chapel Hill, North Caroline)

Being familiar with and following the standard of care guidelines for the individual oral therapies used in the treatment of acne is very important. However, it is equally as important to assure the individual patient (medical history, physical examination, social history, etc) is taken into consideration to determine if additional monitoring is required.—Fran E. Cook-Bolden, MD (New York, New York)

The trend seems to be towards less routine monitoring other than pregnancy. Baseline tests may pick out the occasional patient with comorbidities that would preclude or delay treatment, but the majority of patients may not need the repetitive and costly testing that we have done in the past.—Richard Glogau, MD (San Francisco, California)

I have loosened my lab monitoring with isotretinoin over the past few years. If a patient has normal lipid values, comprehensive panel and complete blood cell count for the first 3 months of tests, I skip labs until the end of therapy.—Lawrence J. Green, MD (Washington, DC)

Interestingly, we focus quite a bit of attention on the risk of pregnancy with isotretinoin, and often don't focus enough on the risk with spironolactone. In our practice, we are careful to warn the patients on spironolactone about pregnancy prevention.—Stephen Stone, MD (Springfield, Illinois)

About This Survey

The survey was fielded electronically to Cutis and Dermatology News Editorial Board Members within the United States from May 5, 2019, to June 23, 2019. A total of 40 usable responses were received.

American Academy of Dermatology. Isotretinoin: recommendations. https://www.aad.org/practicecenter/quality/clinical-guidelines/acne/isotretinoin. Accessed August 20, 2019.

Hansen TJ, Lucking S, Miller JJ, et al. Standardized laboratory monitoring with use of isotretinoin in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:323-328.

Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

Thiede RM, Rastogi S, Nardone B, et al. Hyperkalemia in women with acne exposed to oral spironolactone: a retrospective study from the RADAR (Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports) program. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:155-157.

Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin [published online July 17, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1388.

American Academy of Dermatology. Isotretinoin: recommendations. https://www.aad.org/practicecenter/quality/clinical-guidelines/acne/isotretinoin. Accessed August 20, 2019.

Hansen TJ, Lucking S, Miller JJ, et al. Standardized laboratory monitoring with use of isotretinoin in acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:323-328.

Plovanich M, Weng QY, Mostaghimi A. Low usefulness of potassium monitoring among healthy young women taking spironolactone for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:941-944.

Thiede RM, Rastogi S, Nardone B, et al. Hyperkalemia in women with acne exposed to oral spironolactone: a retrospective study from the RADAR (Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports) program. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:155-157.

Tkachenko E, Singer S, Sharma P, et al. US Food and Drug Administration reports of pregnancy and pregnancy-related adverse events associated with isotretinoin [published online July 17, 2019]. JAMA Dermatol. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1388.

Consider adding chemical peels for your acne patients

MILAN – according to Dee Anna Glaser, MD.

Speaking at the World Congress of Dermatology, Dr. Glaser, director of clinical research and interim chair of the department of dermatology at Saint Louis University, said that in her practice, acne and actinic keratosis are the most common medical indications for chemical peels and that “acne is just a winner all the way around.”

For acne, she added: “Chemical peels can help both the comedonal and the inflammatory component. It should probably be combined with other therapies, and it does produce both an exfoliative and an anti-inflammatory benefit,.”

A variety of chemical peel formulations can be considered for acne, Dr. Glaser noted. “Typically, you’re going to use a light chemical peel,” such as glycolic or salicylic acid. Other options include Jessner’s solution or a light trichloroacetic acid formulation, she said, adding that tretinoin alone can also be considered.

In choosing between glycolic and salicylic acid, Dr. Glaser said, “salicylic acid should theoretically be the best agent because it is lipophilic and the glycolic acid is hydrophilic.” The reality of how these agents perform clinically, though, may sort out differently.

Dr. Glaser pointed to a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of the two agents in 20 women with facial acne. The severity of participants’ inflammatory acne was mild to moderate, with an average of 27 inflammatory lesions, and they had been on a stable prescription or over-the-counter acne regimen for at least 2 months (Dermatol Surg. 2008 Jan;34[1]:45-50).

Patients received six peels – one every 2 weeks – with 30% glycolic acid (an alpha-hydroxy acid) and 30% salicylic acid (a beta-hydroxy acid) in the split-face study.

All participants started at 4 minutes of exposure and increased up to 5 minutes as tolerated, although timing is only really important for glycolic acid, the same duration of exposure was maintained for each agent for the sake of consistency between arms, said Dr. Glaser, one of the investigators.

Sharing photographs of study participants, she observed that after six peels, “there really isn’t a significant difference.” Therefore, she added, “even though salicylic acid should be better, you can see that glycolic acid really held its own in this study.”

Dr. Glaser pointed out that a trend was seen for slightly better results with salicylic acid and results with this agent were more durable than those seen with glycolic acid. Patients reported fewer side effects on the beta-hydroxy–treated side as well.

She referred to another study, conducted in Japan, that used a double-blind, split-face design to compare 40% glycolic acid with a placebo that had a similarly low pH of 2.0. The 26 patients with moderate acne received five peels on a biweekly schedule, with glycolic acid significantly outperforming placebo. Among acne subtypes, noninflammatory acne improved more than inflammatory acne with glycolic acid (Dermatol Surg. 2014 Mar;40[3]:314-22).

Dr. Glaser said that in her own practice, she still tries to use salicylic acid for her acne patients,” though some patients prefer the experience of a glycolic acid peel, with which there’s likely to be less pain. “So if you have a preference, or your patient has a preference, you will probably be able to use the acid that works best for you,” she said.

Whatever peel is chosen, it should be considered an adjuvant to other topical and systemic acne therapies, Dr. Glaser stressed. “To maintain the results, you really do need to maintain the patient on some sort of standard acne therapy that you would normally do.”

Peels can also be an effective part of a multipronged approach that includes laser therapy and intralesional steroids, she said. However, peels can be considered for monotherapy in patients who don’t tolerate other acne therapies, and they can be used safely in pregnancy, she said.

As with all such treatments, dermatologists should remember to consider and counsel about herpes simplex virus prophylaxis and sun protection.

Dr. Glaser reported financial relationships with Galderma, Ulthera, Ortho, Allergan, Cellgene, and other pharmaceutical companies.

MILAN – according to Dee Anna Glaser, MD.

Speaking at the World Congress of Dermatology, Dr. Glaser, director of clinical research and interim chair of the department of dermatology at Saint Louis University, said that in her practice, acne and actinic keratosis are the most common medical indications for chemical peels and that “acne is just a winner all the way around.”

For acne, she added: “Chemical peels can help both the comedonal and the inflammatory component. It should probably be combined with other therapies, and it does produce both an exfoliative and an anti-inflammatory benefit,.”

A variety of chemical peel formulations can be considered for acne, Dr. Glaser noted. “Typically, you’re going to use a light chemical peel,” such as glycolic or salicylic acid. Other options include Jessner’s solution or a light trichloroacetic acid formulation, she said, adding that tretinoin alone can also be considered.

In choosing between glycolic and salicylic acid, Dr. Glaser said, “salicylic acid should theoretically be the best agent because it is lipophilic and the glycolic acid is hydrophilic.” The reality of how these agents perform clinically, though, may sort out differently.

Dr. Glaser pointed to a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of the two agents in 20 women with facial acne. The severity of participants’ inflammatory acne was mild to moderate, with an average of 27 inflammatory lesions, and they had been on a stable prescription or over-the-counter acne regimen for at least 2 months (Dermatol Surg. 2008 Jan;34[1]:45-50).

Patients received six peels – one every 2 weeks – with 30% glycolic acid (an alpha-hydroxy acid) and 30% salicylic acid (a beta-hydroxy acid) in the split-face study.

All participants started at 4 minutes of exposure and increased up to 5 minutes as tolerated, although timing is only really important for glycolic acid, the same duration of exposure was maintained for each agent for the sake of consistency between arms, said Dr. Glaser, one of the investigators.

Sharing photographs of study participants, she observed that after six peels, “there really isn’t a significant difference.” Therefore, she added, “even though salicylic acid should be better, you can see that glycolic acid really held its own in this study.”

Dr. Glaser pointed out that a trend was seen for slightly better results with salicylic acid and results with this agent were more durable than those seen with glycolic acid. Patients reported fewer side effects on the beta-hydroxy–treated side as well.

She referred to another study, conducted in Japan, that used a double-blind, split-face design to compare 40% glycolic acid with a placebo that had a similarly low pH of 2.0. The 26 patients with moderate acne received five peels on a biweekly schedule, with glycolic acid significantly outperforming placebo. Among acne subtypes, noninflammatory acne improved more than inflammatory acne with glycolic acid (Dermatol Surg. 2014 Mar;40[3]:314-22).

Dr. Glaser said that in her own practice, she still tries to use salicylic acid for her acne patients,” though some patients prefer the experience of a glycolic acid peel, with which there’s likely to be less pain. “So if you have a preference, or your patient has a preference, you will probably be able to use the acid that works best for you,” she said.

Whatever peel is chosen, it should be considered an adjuvant to other topical and systemic acne therapies, Dr. Glaser stressed. “To maintain the results, you really do need to maintain the patient on some sort of standard acne therapy that you would normally do.”

Peels can also be an effective part of a multipronged approach that includes laser therapy and intralesional steroids, she said. However, peels can be considered for monotherapy in patients who don’t tolerate other acne therapies, and they can be used safely in pregnancy, she said.

As with all such treatments, dermatologists should remember to consider and counsel about herpes simplex virus prophylaxis and sun protection.

Dr. Glaser reported financial relationships with Galderma, Ulthera, Ortho, Allergan, Cellgene, and other pharmaceutical companies.

MILAN – according to Dee Anna Glaser, MD.

Speaking at the World Congress of Dermatology, Dr. Glaser, director of clinical research and interim chair of the department of dermatology at Saint Louis University, said that in her practice, acne and actinic keratosis are the most common medical indications for chemical peels and that “acne is just a winner all the way around.”

For acne, she added: “Chemical peels can help both the comedonal and the inflammatory component. It should probably be combined with other therapies, and it does produce both an exfoliative and an anti-inflammatory benefit,.”

A variety of chemical peel formulations can be considered for acne, Dr. Glaser noted. “Typically, you’re going to use a light chemical peel,” such as glycolic or salicylic acid. Other options include Jessner’s solution or a light trichloroacetic acid formulation, she said, adding that tretinoin alone can also be considered.

In choosing between glycolic and salicylic acid, Dr. Glaser said, “salicylic acid should theoretically be the best agent because it is lipophilic and the glycolic acid is hydrophilic.” The reality of how these agents perform clinically, though, may sort out differently.

Dr. Glaser pointed to a double-blind, randomized controlled trial of the two agents in 20 women with facial acne. The severity of participants’ inflammatory acne was mild to moderate, with an average of 27 inflammatory lesions, and they had been on a stable prescription or over-the-counter acne regimen for at least 2 months (Dermatol Surg. 2008 Jan;34[1]:45-50).

Patients received six peels – one every 2 weeks – with 30% glycolic acid (an alpha-hydroxy acid) and 30% salicylic acid (a beta-hydroxy acid) in the split-face study.

All participants started at 4 minutes of exposure and increased up to 5 minutes as tolerated, although timing is only really important for glycolic acid, the same duration of exposure was maintained for each agent for the sake of consistency between arms, said Dr. Glaser, one of the investigators.

Sharing photographs of study participants, she observed that after six peels, “there really isn’t a significant difference.” Therefore, she added, “even though salicylic acid should be better, you can see that glycolic acid really held its own in this study.”

Dr. Glaser pointed out that a trend was seen for slightly better results with salicylic acid and results with this agent were more durable than those seen with glycolic acid. Patients reported fewer side effects on the beta-hydroxy–treated side as well.

She referred to another study, conducted in Japan, that used a double-blind, split-face design to compare 40% glycolic acid with a placebo that had a similarly low pH of 2.0. The 26 patients with moderate acne received five peels on a biweekly schedule, with glycolic acid significantly outperforming placebo. Among acne subtypes, noninflammatory acne improved more than inflammatory acne with glycolic acid (Dermatol Surg. 2014 Mar;40[3]:314-22).

Dr. Glaser said that in her own practice, she still tries to use salicylic acid for her acne patients,” though some patients prefer the experience of a glycolic acid peel, with which there’s likely to be less pain. “So if you have a preference, or your patient has a preference, you will probably be able to use the acid that works best for you,” she said.

Whatever peel is chosen, it should be considered an adjuvant to other topical and systemic acne therapies, Dr. Glaser stressed. “To maintain the results, you really do need to maintain the patient on some sort of standard acne therapy that you would normally do.”

Peels can also be an effective part of a multipronged approach that includes laser therapy and intralesional steroids, she said. However, peels can be considered for monotherapy in patients who don’t tolerate other acne therapies, and they can be used safely in pregnancy, she said.

As with all such treatments, dermatologists should remember to consider and counsel about herpes simplex virus prophylaxis and sun protection.

Dr. Glaser reported financial relationships with Galderma, Ulthera, Ortho, Allergan, Cellgene, and other pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM WCD2019

The ABCs of COCs: A Guide for Dermatology Residents on Combined Oral Contraceptives

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

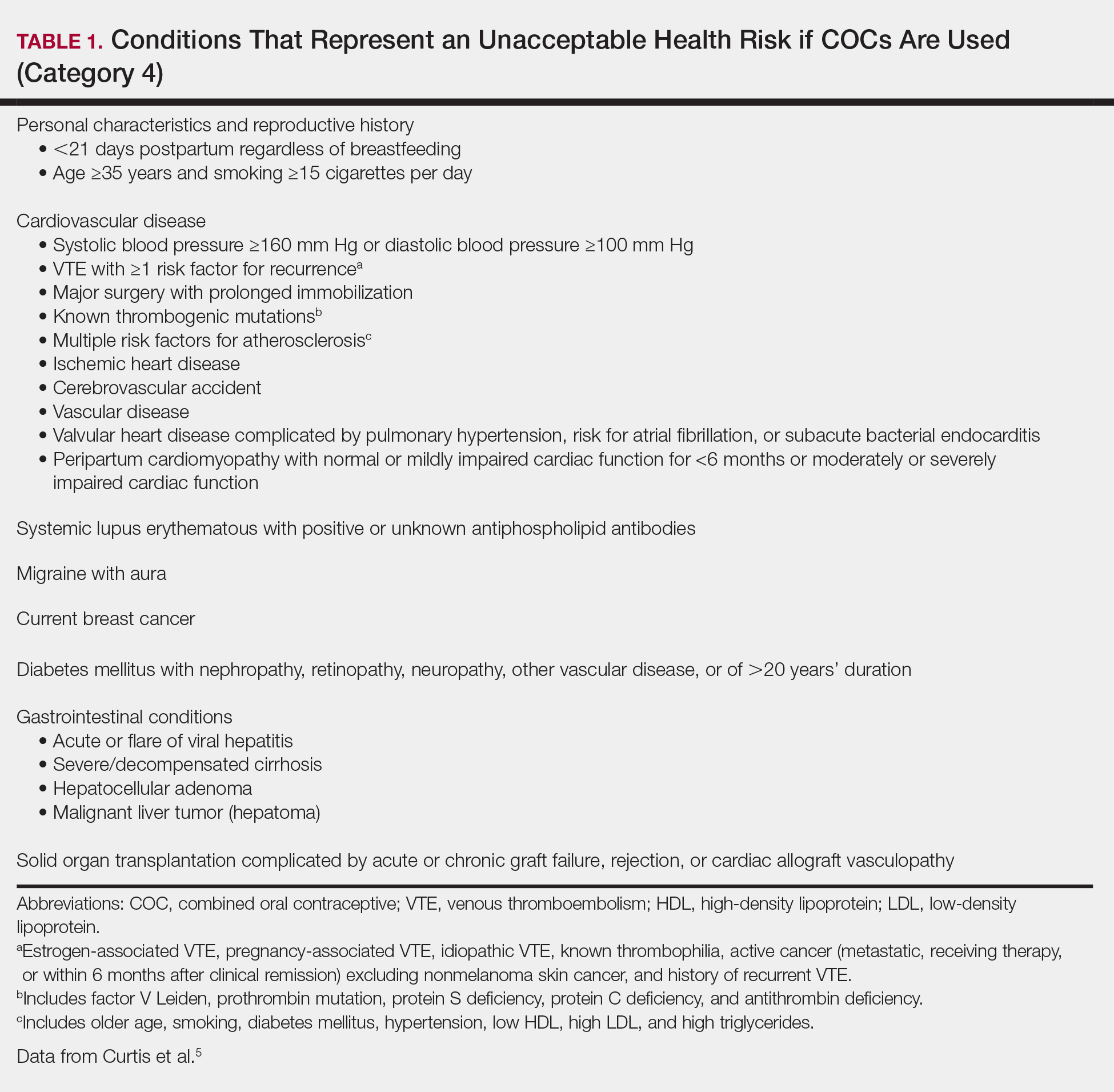

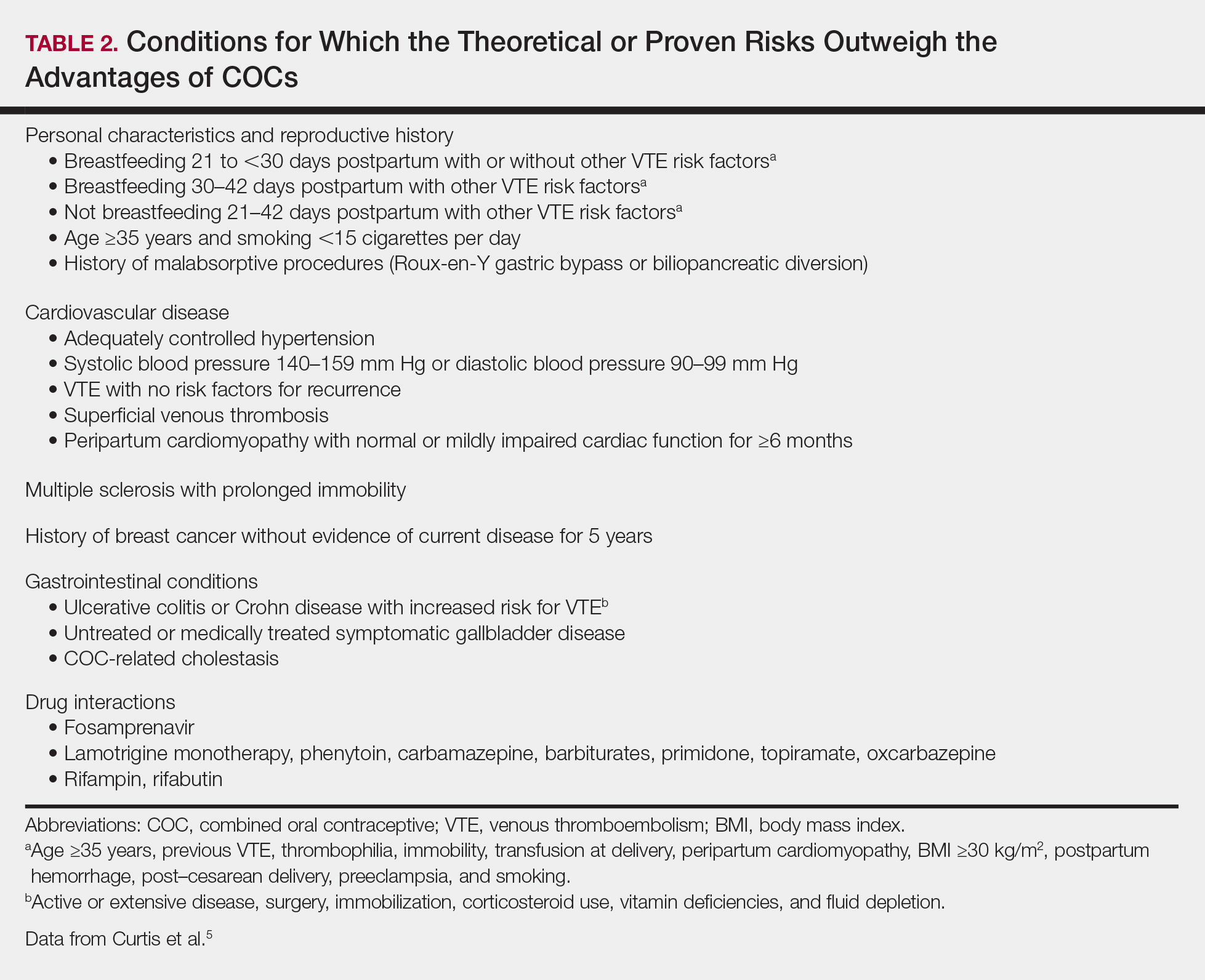

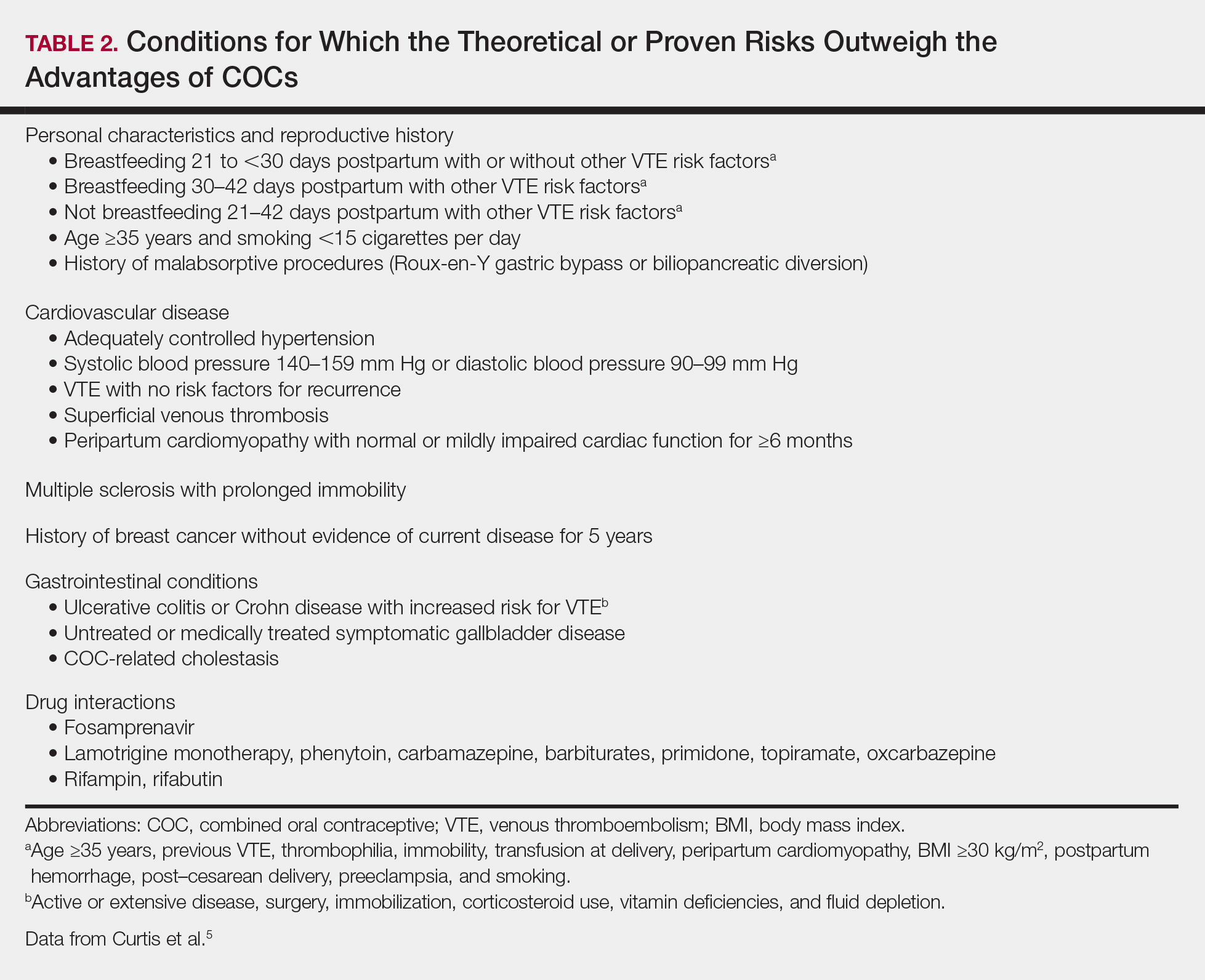

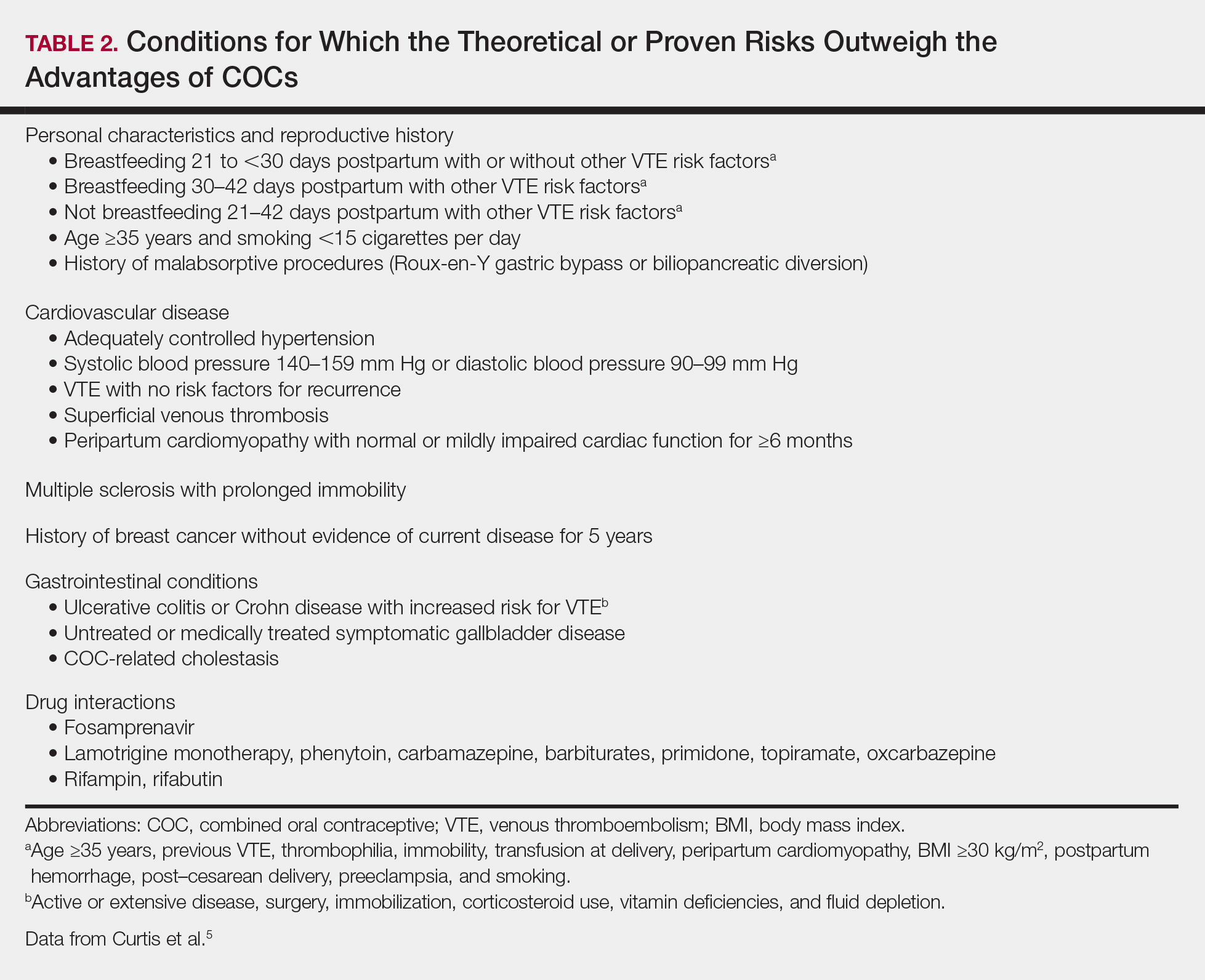

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease

A 2015 Cochrane review found that the risk for myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke is increased 1.6‐fold in COC users.16 Despite this increased relative risk, the increased absolute annual risk of myocardial infarction in nonsmoking women remains low: increased from 0.83 to 3.53 per 10,000,000 women younger than 35 years and from 9.45 to 40.4 per 10,000,000 women 35 years and older.17

Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

Data are mixed on the effect of COCs on the risk for breast cancer and cervical cancer.1 According to the CDC, COC use for 5 or more years might increase the risk of cervical carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in women with persistent human papillomavirus infection.5 Regardless of COC use, women should undergo age-appropriate screening for breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Melasma

Melasma is an estrogen-mediated side effect of COCs.8 A study from 1967 found that 29% of COC users (N=212) developed melasma; however, they were taking COCs with much higher ethinyl estradiol doses (50–100 μg) than typically used today.18 Nevertheless, as part of an overall skin care regimen, photoprotection should be encouraged with a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen that has a sun protection factor of at least 30. In addition, sunscreens with iron oxides have been shown to better prevent melasma relapse by protecting against the shorter wavelengths of visible light.19

- Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.e933.

- Landis ET, Levender MM, Davis SA, et al. Isotretinoin and oral contraceptive use in female acne patients varies by physician specialty: analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Dermatolog Treat. 2012;23:272-277.

- Fitzpatrick L, Mauer E, Chen CL. Oral contraceptives for acne treatment: US dermatologists’ knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices. Cutis. 2017;99:195-201.

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

- Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Van Vliet HA, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, et al. Triphasic versus monophasic oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003553.

- Stewart M, Black K. Choosing a combined oral contraceptive pill. Aust Prescr. 2015;38:6-11.

- McKinney K. Understanding the options: a guide to oral contraceptives. https://www.cecentral.com/assets/2097/022%20Oral%20Contraceptives%2010-26-09.pdf. Published November 5, 2009. Accessed June 20, 2019.

- Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA, et al. 20 microg versus >20 microg estrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003989.

- Terki F, Malhotra U. Medical and Service Delivery Guidelines for Sexual and Reproductive Health Services. London, United Kingdom: International Planned Parenthood Federation; 2004.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:CD004425.

- Pastor Z, Holla K, Chmel R. The influence of combined oral contraceptives on female sexual desire: a systematic review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2013;18:27-43.

- Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, et al. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD003987.

- Birth control pills for acne: tips from Julie Harper at the Summer AAD. Cutis. https://www.mdedge.com/dermatology/article/144550/acne/birth-control-pills-acne-tips-julie-harper-summer-aad. Published August 14, 2017. Accessed June 24, 2019.

- Watson HG, Baglin TP. Guidelines on travel-related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:31-34.

- Roach RE, Helmerhorst FM, Lijfering WM, et al. Combined oral contraceptives: the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD011054.

- Acute myocardial infarction and combined oral contraceptives: results of an international multicentre case-control study. WHO Collaborative Study of Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception. Lancet. 1997;349:1202-1209.

- Resnik S. Melasma induced by oral contraceptive drugs. JAMA. 1967;199:601-605.

- Boukari F, Jourdan E, Fontas E, et al. Prevention of melasma relapses with sunscreen combining protection against UV and short wavelengths of visible light: a prospective randomized comparative trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:189-190.e181.

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic

All the hormonally active pills in a monophasic formulation contain the same dose of estrogen and progestin; however, these doses change per pill in a multiphasic formulation, which requires that patients take the pills in a specific order. Given this greater complexity and the fact that multiphasic formulations often are more expensive and lack evidence of superiority, a 2011 Cochrane review recommended monophasic formulations as first line.6 In addition, monophasic formulations are preferred for autoimmune progesterone dermatitis because of the stable progestin dose.

Hormone-Free Interval

Some COCs include placebo pills during which hormone withdrawal symptoms such as bleeding, pelvic pain, mood changes, and headache may occur. If a patient is concerned about these symptoms, choose a COC with no or fewer placebo pills, or have the patient skip the hormone-free interval altogether and start the next pack early7; in this case, the prescription should be written with instructions to allow the patient to get earlier refills from the pharmacy.

Estrogen Dose

To minimize estrogen-related side effects, the lowest possible dose of ethinyl estradiol that is effective and tolerable should be prescribed7,8; 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol generally is the lowest dose available, but it may be associated with more frequent breakthrough bleeding.9 The International Planned Parenthood Federation recommends starting with COCs that contain 30 to 35 μg of estrogen.10 Synthesizing this information, one option is to start with 20 μg of ethinyl estradiol and increase the dose if breakthrough bleeding persists after 3 cycles.

Progestin Type

First-generation progestins (eg, norethindrone), second-generation progestins (eg, norgestrel, levonorgestrel), and third-generation progestins (eg, norgestimate, desogestrel) are derived from testosterone and therefore are variably androgenic; second-generation progestins are the most androgenic, and third-generation progestins are the least. On the other hand, drospirenone, the fourth-generation progestin available in the United States, is derived from 17α-spironolactone and thus is mildly antiandrogenic (3 mg of drospirenone is considered equivalent to 25 mg of spironolactone).

Although COCs with less androgenic progestins should theoretically treat acne better, a 2012 Cochrane review of COCs and acne concluded that “differences in the comparative effectiveness of COCs containing varying progestin types and dosages were less clear, and data were limited for any particular comparison.”11 As a result, regardless of the progestin, all COCs are believed to have a net antiandrogenic effect due to their estrogen component.1

Counsel on Use

Combined oral contraceptives can be started on any day of the menstrual cycle, including the day the prescription is given. If a patient begins a COC within 5 days of the first day of her most recent period, backup contraception is not needed.4 If she begins the COC more than 5 days after the first day of her most recent period, she needs to use backup contraception or abstain from sexual intercourse for the next 7 days.4 In general, at least 3 months of therapy are required to evaluate the effectiveness of COCs for acne.1

Manage Risks and Side Effects

Breakthrough Bleeding

The most common side effect of breakthrough bleeding can be minimized by taking COCs at approximately the same time every day and avoiding missed pills. If breakthrough bleeding does not stop after 3 cycles, consider increasing the estrogen dose to 30 to 35 μg and/or referring to an obstetrician/gynecologist to rule out other etiologies of bleeding.7,8

Nausea, Headache, Bloating, and Breast Tenderness

These symptoms typically resolve after the first 3 months. To minimize nausea, patients should take COCs in the early evening and eat breakfast the next morning.7,8 For headaches that occur during the hormone-free interval, consider skipping the placebo pills and starting the next pack early. Switching the progestin to drospirenone, which has a mild diuretic effect, can help with bloating as well as breast tenderness.7 For persistent symptoms, consider a lower estrogen dose.7,8

Changes in Libido

In a systemic review including 8422 COC users, 64% reported no change in libido, 22% reported an increase, and 15% reported a decrease.12

Weight Gain

Although patients may be concerned that COCs cause weight gain, a 2014 Cochrane review concluded that “available evidence is insufficient to determine the effect of combination contraceptives on weight, but no large effect is evident.”13 If weight gain does occur, anecdotal evidence suggests it tends to be not more than 5 pounds. If weight gain is an issue, consider a less androgenic progestin.8

Venous Thromboembolism

Use the 3-6-9-12 model to contextualize venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk: a woman’s annual VTE risk is 3 per 10,000 women at baseline, 6 per 10,000 women with nondrospirenone COCs, 9 per 10,000 women with drospirenone-containing COCs, and 12 per 10,000 women when pregnant.14 Patients should be counseled on the signs and symptoms of VTE such as unilateral or bilateral leg or arm swelling, pain, warmth, redness, and/or shortness of breath. The British Society for Haematology recommends maintaining mobility as a reasonable precaution when traveling for more than 3 hours.15

Cardiovascular Disease

A 2015 Cochrane review found that the risk for myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke is increased 1.6‐fold in COC users.16 Despite this increased relative risk, the increased absolute annual risk of myocardial infarction in nonsmoking women remains low: increased from 0.83 to 3.53 per 10,000,000 women younger than 35 years and from 9.45 to 40.4 per 10,000,000 women 35 years and older.17

Breast Cancer and Cervical Cancer

Data are mixed on the effect of COCs on the risk for breast cancer and cervical cancer.1 According to the CDC, COC use for 5 or more years might increase the risk of cervical carcinoma in situ and invasive cervical carcinoma in women with persistent human papillomavirus infection.5 Regardless of COC use, women should undergo age-appropriate screening for breast cancer and cervical cancer.

Melasma

Melasma is an estrogen-mediated side effect of COCs.8 A study from 1967 found that 29% of COC users (N=212) developed melasma; however, they were taking COCs with much higher ethinyl estradiol doses (50–100 μg) than typically used today.18 Nevertheless, as part of an overall skin care regimen, photoprotection should be encouraged with a broad-spectrum, water-resistant sunscreen that has a sun protection factor of at least 30. In addition, sunscreens with iron oxides have been shown to better prevent melasma relapse by protecting against the shorter wavelengths of visible light.19

The American Academy of Dermatology confers combined oral contraceptives (COCs) a strength A recommendation for the treatment of acne based on level I evidence, and 4 COCs are approved for the treatment of acne by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Furthermore, when dermatologists prescribe isotretinoin and thalidomide to women of reproductive potential, the iPLEDGE and THALOMID Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) programs require 2 concurrent methods of contraception, one of which may be a COC. In addition, COCs have several potential off-label indications in dermatology including idiopathic hirsutism, female pattern hair loss, hidradenitis suppurativa, and autoimmune progesterone dermatitis.

Despite this evidence and opportunity, research suggests that dermatologists underprescribe COCs. The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey found that between 1993 and 2008, dermatologists in the United States prescribed COCs to only 2.03% of women presenting for acne treatment, which was less often than obstetricians/gynecologists (36.03%) and internists (10.76%).2 More recently, in a survey of 130 US dermatologists conducted from 2014 to 2015, only 55.4% reported prescribing COCs. This survey also found that only 45.8% of dermatologists who prescribed COCs felt very comfortable counseling on how to begin taking them, only 48.6% felt very comfortable counseling patients on side effects, and only 22.2% felt very comfortable managing side effects.3

In light of these data, this article reviews the basics of COCs for dermatology residents, from assessing patient eligibility and selecting a COC to counseling on use and managing risks and side effects. Because there are different approaches to prescribing COCs, readers are encouraged to integrate the information in this article with what they have learned from other sources.

Assess Patient Eligibility

In general, patients should be at least 14 years of age and have waited 2 years after menarche to start COCs. They can be taken until menopause.1,4 Contraindications can be screened for by taking a medical history and measuring a baseline blood pressure (Tables 1 and 2).5 In addition, pregnancy should be excluded with a urine or serum pregnancy test or criteria provided in Box 2 of the 2016 US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 Although important for women’s overall health, a pelvic examination is not required to start COCs according to the CDC and the American Academy of Dermatology.1,4

Select the COC

Combined oral contraceptives combine estrogen, usually in the form of ethinyl estradiol, with a progestin. Data suggest that all COCs effectively treat acne, but 4 are specifically FDA approved for acne: ethinyl estradiol–norethindrone acetate–ferrous fumarate, ethinyl estradiol–norgestimate, ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone, and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone–levomefolate.1 Ethinyl estradiol–desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol–drospirenone are 2 go-to COCs for some of the attending physicians at my residency program. All COCs are FDA approved for contraception. When selecting a COC, one approach is to start with the patient’s drug formulary, then consider the following characteristics.

Monophasic vs Multiphasic