User login

CMS to cover Alzheimer’s drugs after traditional FDA okay

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has announced that

The one caveat is that CMS will require physicians to participate in registries that collect evidence about how these drugs work in the real world.

Physicians will be able to submit this evidence through a nationwide, CMS-facilitated portal that will be available when any product gains traditional approval and will collect information via an easy-to-use format.

“If the FDA grants traditional approval, then Medicare will cover it in appropriate settings that also support the collection of real-world information to study the usefulness of these drugs for people with Medicare,” the CMS says in a news release.

“CMS has always been committed to helping people obtain timely access to innovative treatments that meaningfully improve care and outcomes for this disease,” added CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

“If the FDA grants traditional approval, CMS is prepared to ensure anyone with Medicare Part B who meets the criteria is covered,” Ms. Brooks-LaSure explained.

The CMS says broader Medicare coverage for an Alzheimer’s drug would begin on the same day the FDA grants traditional approval. Under CMS’ current coverage policy, if the FDA grants traditional approval to other drugs in this class, they would also be eligible for broader coverage.

Currently two drugs in this class – aducanumab (Aduhelm) and lecanemab (Leqembi) – have received accelerated approval from the FDA, but no product has received traditional approval.

Lecanemab might be the first to cross the line.

On June 9, the FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee will discuss results of a confirmatory trial of lecanemab, with a potential decision on traditional approval expected shortly thereafter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has announced that

The one caveat is that CMS will require physicians to participate in registries that collect evidence about how these drugs work in the real world.

Physicians will be able to submit this evidence through a nationwide, CMS-facilitated portal that will be available when any product gains traditional approval and will collect information via an easy-to-use format.

“If the FDA grants traditional approval, then Medicare will cover it in appropriate settings that also support the collection of real-world information to study the usefulness of these drugs for people with Medicare,” the CMS says in a news release.

“CMS has always been committed to helping people obtain timely access to innovative treatments that meaningfully improve care and outcomes for this disease,” added CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

“If the FDA grants traditional approval, CMS is prepared to ensure anyone with Medicare Part B who meets the criteria is covered,” Ms. Brooks-LaSure explained.

The CMS says broader Medicare coverage for an Alzheimer’s drug would begin on the same day the FDA grants traditional approval. Under CMS’ current coverage policy, if the FDA grants traditional approval to other drugs in this class, they would also be eligible for broader coverage.

Currently two drugs in this class – aducanumab (Aduhelm) and lecanemab (Leqembi) – have received accelerated approval from the FDA, but no product has received traditional approval.

Lecanemab might be the first to cross the line.

On June 9, the FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee will discuss results of a confirmatory trial of lecanemab, with a potential decision on traditional approval expected shortly thereafter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has announced that

The one caveat is that CMS will require physicians to participate in registries that collect evidence about how these drugs work in the real world.

Physicians will be able to submit this evidence through a nationwide, CMS-facilitated portal that will be available when any product gains traditional approval and will collect information via an easy-to-use format.

“If the FDA grants traditional approval, then Medicare will cover it in appropriate settings that also support the collection of real-world information to study the usefulness of these drugs for people with Medicare,” the CMS says in a news release.

“CMS has always been committed to helping people obtain timely access to innovative treatments that meaningfully improve care and outcomes for this disease,” added CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

“If the FDA grants traditional approval, CMS is prepared to ensure anyone with Medicare Part B who meets the criteria is covered,” Ms. Brooks-LaSure explained.

The CMS says broader Medicare coverage for an Alzheimer’s drug would begin on the same day the FDA grants traditional approval. Under CMS’ current coverage policy, if the FDA grants traditional approval to other drugs in this class, they would also be eligible for broader coverage.

Currently two drugs in this class – aducanumab (Aduhelm) and lecanemab (Leqembi) – have received accelerated approval from the FDA, but no product has received traditional approval.

Lecanemab might be the first to cross the line.

On June 9, the FDA Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee will discuss results of a confirmatory trial of lecanemab, with a potential decision on traditional approval expected shortly thereafter.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Younger age of type 2 diabetes onset linked to dementia risk

, new findings suggest.

Moreover, the new data from the prospective Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort also suggest that the previously identified increased risk for dementia among people with prediabetes appears to be entirely explained by the subset who go on to develop type 2 diabetes.

“Our findings suggest that preventing prediabetes progression, especially in younger individuals, may be an important way to reduce the dementia burden,” wrote PhD student Jiaqi Hu of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. Their article was published online in Diabetologia.

The result builds on previous findings linking dysglycemia and cognitive decline, the study’s lead author, Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, of the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins, said in an interview.

“Our prior work in the ARIC study suggests that improving glucose control could help prevent dementia in later life,” she said.

Other studies have also linked higher A1c levels and diabetes in midlife to increased rates of cognitive decline. In addition, Dr. Selvin noted, “There is growing evidence that focusing on vascular health, especially focusing on diabetes and blood pressure, in midlife can stave off dementia in later life.”

This new study is the first to examine the effect of diabetes in the relationship between prediabetes and dementia, as well as the age of diabetes onset on subsequent dementia.

Prediabetes linked to dementia via diabetes development

Of the 11,656 ARIC participants without diabetes at baseline during 1990-1992 (age 46-70 years), 20.0% had prediabetes (defined as A1c 5.7%-6.4% or 39-46 mmol/mol). During a median follow-up of 15.9 years, 3,143 participants developed diabetes. The proportions of patients who developed diabetes were 44.6% among those with prediabetes at baseline versus 22.5% of those without.

Dementia developed in 2,247 participants over a median follow-up of 24.7 years. The cumulative incidence of dementia was 23.9% among those who developed diabetes versus 20.5% among those who did not.

After adjustment for demographics and for the Alzheimer’s disease–linked apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, prediabetes was significantly associated with incident dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 1.19). However, significance disappeared after adjustment for incident diabetes (HR, 1.09), the researchers reported.

Younger age at diabetes diagnosis raises dementia risk

Age at diabetes diagnosis made a difference in dementia risk. With adjustments for lifestyle, demographic, and clinical factors, those diagnosed with diabetes before age 60 years had a nearly threefold increased risk for dementia compared with those who never developed diabetes (HR, 2.92; P < .001).

The dementia risk was also significantly increased, although to a lesser degree, among those aged 60-69 years at diabetes diagnosis (HR, 1.73; P < .001) and age 70-79 years at diabetes diagnosis (HR, 1.23; P < .001). The relationship was not significant for those aged 80 years and older (HR, 1.13).

“Prevention efforts in people with diabetes diagnosed younger than 65 years should be a high priority,” the authors urged.

Taken together, the data suggest that prolonged exposure to hyperglycemia plays a major role in dementia development.

“Putative mechanisms include acute and chronic hyperglycemia, glucose toxicity, insulin resistance, and microvascular dysfunction of the central nervous system. ... Glucose toxicity and microvascular dysfunction are associated with increased inflammatory and oxidative stress, leading to increased blood–brain permeability,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Selvin said that her group is pursuing further work in this area using continuous glucose monitoring. “We plan to look at ... how glycemic control and different patterns of glucose in older adults may be linked to cognitive decline and other neurocognitive outcomes.”

The researchers reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Selvin has reported being on the advisory board for Diabetologia; she had no role in peer review of the manuscript.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new findings suggest.

Moreover, the new data from the prospective Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort also suggest that the previously identified increased risk for dementia among people with prediabetes appears to be entirely explained by the subset who go on to develop type 2 diabetes.

“Our findings suggest that preventing prediabetes progression, especially in younger individuals, may be an important way to reduce the dementia burden,” wrote PhD student Jiaqi Hu of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. Their article was published online in Diabetologia.

The result builds on previous findings linking dysglycemia and cognitive decline, the study’s lead author, Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, of the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins, said in an interview.

“Our prior work in the ARIC study suggests that improving glucose control could help prevent dementia in later life,” she said.

Other studies have also linked higher A1c levels and diabetes in midlife to increased rates of cognitive decline. In addition, Dr. Selvin noted, “There is growing evidence that focusing on vascular health, especially focusing on diabetes and blood pressure, in midlife can stave off dementia in later life.”

This new study is the first to examine the effect of diabetes in the relationship between prediabetes and dementia, as well as the age of diabetes onset on subsequent dementia.

Prediabetes linked to dementia via diabetes development

Of the 11,656 ARIC participants without diabetes at baseline during 1990-1992 (age 46-70 years), 20.0% had prediabetes (defined as A1c 5.7%-6.4% or 39-46 mmol/mol). During a median follow-up of 15.9 years, 3,143 participants developed diabetes. The proportions of patients who developed diabetes were 44.6% among those with prediabetes at baseline versus 22.5% of those without.

Dementia developed in 2,247 participants over a median follow-up of 24.7 years. The cumulative incidence of dementia was 23.9% among those who developed diabetes versus 20.5% among those who did not.

After adjustment for demographics and for the Alzheimer’s disease–linked apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, prediabetes was significantly associated with incident dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 1.19). However, significance disappeared after adjustment for incident diabetes (HR, 1.09), the researchers reported.

Younger age at diabetes diagnosis raises dementia risk

Age at diabetes diagnosis made a difference in dementia risk. With adjustments for lifestyle, demographic, and clinical factors, those diagnosed with diabetes before age 60 years had a nearly threefold increased risk for dementia compared with those who never developed diabetes (HR, 2.92; P < .001).

The dementia risk was also significantly increased, although to a lesser degree, among those aged 60-69 years at diabetes diagnosis (HR, 1.73; P < .001) and age 70-79 years at diabetes diagnosis (HR, 1.23; P < .001). The relationship was not significant for those aged 80 years and older (HR, 1.13).

“Prevention efforts in people with diabetes diagnosed younger than 65 years should be a high priority,” the authors urged.

Taken together, the data suggest that prolonged exposure to hyperglycemia plays a major role in dementia development.

“Putative mechanisms include acute and chronic hyperglycemia, glucose toxicity, insulin resistance, and microvascular dysfunction of the central nervous system. ... Glucose toxicity and microvascular dysfunction are associated with increased inflammatory and oxidative stress, leading to increased blood–brain permeability,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Selvin said that her group is pursuing further work in this area using continuous glucose monitoring. “We plan to look at ... how glycemic control and different patterns of glucose in older adults may be linked to cognitive decline and other neurocognitive outcomes.”

The researchers reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Selvin has reported being on the advisory board for Diabetologia; she had no role in peer review of the manuscript.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new findings suggest.

Moreover, the new data from the prospective Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort also suggest that the previously identified increased risk for dementia among people with prediabetes appears to be entirely explained by the subset who go on to develop type 2 diabetes.

“Our findings suggest that preventing prediabetes progression, especially in younger individuals, may be an important way to reduce the dementia burden,” wrote PhD student Jiaqi Hu of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues. Their article was published online in Diabetologia.

The result builds on previous findings linking dysglycemia and cognitive decline, the study’s lead author, Elizabeth Selvin, PhD, of the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins, said in an interview.

“Our prior work in the ARIC study suggests that improving glucose control could help prevent dementia in later life,” she said.

Other studies have also linked higher A1c levels and diabetes in midlife to increased rates of cognitive decline. In addition, Dr. Selvin noted, “There is growing evidence that focusing on vascular health, especially focusing on diabetes and blood pressure, in midlife can stave off dementia in later life.”

This new study is the first to examine the effect of diabetes in the relationship between prediabetes and dementia, as well as the age of diabetes onset on subsequent dementia.

Prediabetes linked to dementia via diabetes development

Of the 11,656 ARIC participants without diabetes at baseline during 1990-1992 (age 46-70 years), 20.0% had prediabetes (defined as A1c 5.7%-6.4% or 39-46 mmol/mol). During a median follow-up of 15.9 years, 3,143 participants developed diabetes. The proportions of patients who developed diabetes were 44.6% among those with prediabetes at baseline versus 22.5% of those without.

Dementia developed in 2,247 participants over a median follow-up of 24.7 years. The cumulative incidence of dementia was 23.9% among those who developed diabetes versus 20.5% among those who did not.

After adjustment for demographics and for the Alzheimer’s disease–linked apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, prediabetes was significantly associated with incident dementia (hazard ratio [HR], 1.19). However, significance disappeared after adjustment for incident diabetes (HR, 1.09), the researchers reported.

Younger age at diabetes diagnosis raises dementia risk

Age at diabetes diagnosis made a difference in dementia risk. With adjustments for lifestyle, demographic, and clinical factors, those diagnosed with diabetes before age 60 years had a nearly threefold increased risk for dementia compared with those who never developed diabetes (HR, 2.92; P < .001).

The dementia risk was also significantly increased, although to a lesser degree, among those aged 60-69 years at diabetes diagnosis (HR, 1.73; P < .001) and age 70-79 years at diabetes diagnosis (HR, 1.23; P < .001). The relationship was not significant for those aged 80 years and older (HR, 1.13).

“Prevention efforts in people with diabetes diagnosed younger than 65 years should be a high priority,” the authors urged.

Taken together, the data suggest that prolonged exposure to hyperglycemia plays a major role in dementia development.

“Putative mechanisms include acute and chronic hyperglycemia, glucose toxicity, insulin resistance, and microvascular dysfunction of the central nervous system. ... Glucose toxicity and microvascular dysfunction are associated with increased inflammatory and oxidative stress, leading to increased blood–brain permeability,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Selvin said that her group is pursuing further work in this area using continuous glucose monitoring. “We plan to look at ... how glycemic control and different patterns of glucose in older adults may be linked to cognitive decline and other neurocognitive outcomes.”

The researchers reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Selvin has reported being on the advisory board for Diabetologia; she had no role in peer review of the manuscript.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIABETOLOGIA

Alzheimer’s Disease Etiology

Which interventions could lessen the burden of dementia?

Using a microsimulation algorithm that accounts for the effect on mortality, a team from Marseille, France, has shown that interventions targeting the three main vascular risk factors for dementia – hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity – could significantly reduce the burden of dementia by 2040.

Although these modeling results could appear too optimistic, since total disappearance of the risk factors was assumed, the authors say the results do show that targeted interventions for these factors could be effective in reducing the future burden of dementia.

Increasing prevalence

According to the World Alzheimer Report 2018, 50 million people around the world were living with dementia; a population roughly around the size of South Korea or Spain. That community is likely to rise to about 152 million people by 2050, which is similar to the size of Russia or Bangladesh, the result of an aging population.

Among modifiable risk factors, many studies support a deleterious effect of hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity on the risk of dementia. However, since the distribution of these risk factors could have a direct impact on mortality, reducing it should increase life expectancy and the number of cases of dementia.

The team, headed by Hélène Jacqmin-Gadda, PhD, research director at the University of Bordeaux (France), has developed a microsimulation model capable of predicting the burden of dementia while accounting for the impact on mortality. The team used this approach to assess the impact of interventions targeting these three main risk factors on the burden of dementia in France by 2040.

Removing risk factors

The researchers estimated the incidence of dementia for men and women using data from the 2020 PAQUID cohort, and these data were combined with the projections forecast by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies to account for mortality with and without dementia.

Without intervention, the prevalence rate of dementia in 2040 would be 9.6% among men and 14% among women older than 65 years.

These figures would decrease to 6.4% (−33%) and 10.4% (−26%), respectively, under the intervention scenario whereby the three modifiable vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity) would be removed simultaneously beginning in 2020. The prevalence rates are significantly reduced for men and women from age 75 years. In this scenario, life expectancy without dementia would increase by 3.4 years in men and 2.6 years in women, the result of men being more exposed to these three risk factors.

Other scenarios have estimated dementia prevalence with the disappearance of just one of these risk factors. For example, the disappearance of hypertension alone from 2020 could decrease dementia prevalence by 21% in men and 16% in women (because this risk factor is less common in women than in men) by 2040. This reduction would be associated with a decrease in the lifelong probability of dementia among men and women and a gain in life expectancy without dementia of 2 years in men and 1.4 years in women.

Among the three factors, hypertension has the largest impact on dementia burden in the French population, since this is, by far, the most prevalent (69% in men and 49% in women), while intervention targeting only diabetes or physical inactivity would lead to a reduction in dementia prevalence of only 4%-7%.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Using a microsimulation algorithm that accounts for the effect on mortality, a team from Marseille, France, has shown that interventions targeting the three main vascular risk factors for dementia – hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity – could significantly reduce the burden of dementia by 2040.

Although these modeling results could appear too optimistic, since total disappearance of the risk factors was assumed, the authors say the results do show that targeted interventions for these factors could be effective in reducing the future burden of dementia.

Increasing prevalence

According to the World Alzheimer Report 2018, 50 million people around the world were living with dementia; a population roughly around the size of South Korea or Spain. That community is likely to rise to about 152 million people by 2050, which is similar to the size of Russia or Bangladesh, the result of an aging population.

Among modifiable risk factors, many studies support a deleterious effect of hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity on the risk of dementia. However, since the distribution of these risk factors could have a direct impact on mortality, reducing it should increase life expectancy and the number of cases of dementia.

The team, headed by Hélène Jacqmin-Gadda, PhD, research director at the University of Bordeaux (France), has developed a microsimulation model capable of predicting the burden of dementia while accounting for the impact on mortality. The team used this approach to assess the impact of interventions targeting these three main risk factors on the burden of dementia in France by 2040.

Removing risk factors

The researchers estimated the incidence of dementia for men and women using data from the 2020 PAQUID cohort, and these data were combined with the projections forecast by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies to account for mortality with and without dementia.

Without intervention, the prevalence rate of dementia in 2040 would be 9.6% among men and 14% among women older than 65 years.

These figures would decrease to 6.4% (−33%) and 10.4% (−26%), respectively, under the intervention scenario whereby the three modifiable vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity) would be removed simultaneously beginning in 2020. The prevalence rates are significantly reduced for men and women from age 75 years. In this scenario, life expectancy without dementia would increase by 3.4 years in men and 2.6 years in women, the result of men being more exposed to these three risk factors.

Other scenarios have estimated dementia prevalence with the disappearance of just one of these risk factors. For example, the disappearance of hypertension alone from 2020 could decrease dementia prevalence by 21% in men and 16% in women (because this risk factor is less common in women than in men) by 2040. This reduction would be associated with a decrease in the lifelong probability of dementia among men and women and a gain in life expectancy without dementia of 2 years in men and 1.4 years in women.

Among the three factors, hypertension has the largest impact on dementia burden in the French population, since this is, by far, the most prevalent (69% in men and 49% in women), while intervention targeting only diabetes or physical inactivity would lead to a reduction in dementia prevalence of only 4%-7%.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

Using a microsimulation algorithm that accounts for the effect on mortality, a team from Marseille, France, has shown that interventions targeting the three main vascular risk factors for dementia – hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity – could significantly reduce the burden of dementia by 2040.

Although these modeling results could appear too optimistic, since total disappearance of the risk factors was assumed, the authors say the results do show that targeted interventions for these factors could be effective in reducing the future burden of dementia.

Increasing prevalence

According to the World Alzheimer Report 2018, 50 million people around the world were living with dementia; a population roughly around the size of South Korea or Spain. That community is likely to rise to about 152 million people by 2050, which is similar to the size of Russia or Bangladesh, the result of an aging population.

Among modifiable risk factors, many studies support a deleterious effect of hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity on the risk of dementia. However, since the distribution of these risk factors could have a direct impact on mortality, reducing it should increase life expectancy and the number of cases of dementia.

The team, headed by Hélène Jacqmin-Gadda, PhD, research director at the University of Bordeaux (France), has developed a microsimulation model capable of predicting the burden of dementia while accounting for the impact on mortality. The team used this approach to assess the impact of interventions targeting these three main risk factors on the burden of dementia in France by 2040.

Removing risk factors

The researchers estimated the incidence of dementia for men and women using data from the 2020 PAQUID cohort, and these data were combined with the projections forecast by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies to account for mortality with and without dementia.

Without intervention, the prevalence rate of dementia in 2040 would be 9.6% among men and 14% among women older than 65 years.

These figures would decrease to 6.4% (−33%) and 10.4% (−26%), respectively, under the intervention scenario whereby the three modifiable vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, and physical inactivity) would be removed simultaneously beginning in 2020. The prevalence rates are significantly reduced for men and women from age 75 years. In this scenario, life expectancy without dementia would increase by 3.4 years in men and 2.6 years in women, the result of men being more exposed to these three risk factors.

Other scenarios have estimated dementia prevalence with the disappearance of just one of these risk factors. For example, the disappearance of hypertension alone from 2020 could decrease dementia prevalence by 21% in men and 16% in women (because this risk factor is less common in women than in men) by 2040. This reduction would be associated with a decrease in the lifelong probability of dementia among men and women and a gain in life expectancy without dementia of 2 years in men and 1.4 years in women.

Among the three factors, hypertension has the largest impact on dementia burden in the French population, since this is, by far, the most prevalent (69% in men and 49% in women), while intervention targeting only diabetes or physical inactivity would lead to a reduction in dementia prevalence of only 4%-7%.

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

This article was translated from Univadis France. A version appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF EPIDEMIOLOGY

Internet use a modifiable dementia risk factor in older adults?

Investigators followed more than 18,000 older individuals and found that regular Internet use was associated with about a 50% reduction in dementia risk, compared with their counterparts who did not use the Internet regularly.

They also found that longer duration of regular Internet use was associated with a reduced risk of dementia, although excessive daily Internet usage appeared to adversely affect dementia risk.

“Online engagement can develop and maintain cognitive reserve – resiliency against physiological damage to the brain – and increased cognitive reserve can, in turn, compensate for brain aging and reduce the risk of dementia,” study investigator Gawon Cho, a doctoral candidate at New York University School of Global Public Health, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Unexamined benefits

Prior research has shown that older adult Internet users have “better overall cognitive performance, verbal reasoning, and memory,” compared with nonusers, the authors note.

However, because this body of research consists of cross-sectional analyses and longitudinal studies with brief follow-up periods, the long-term cognitive benefits of Internet usage remain “unexamined.”

In addition, despite “extensive evidence of a disproportionately high burden of dementia in people of color, individuals without higher education, and adults who experienced other socioeconomic hardships, little is known about whether the Internet has exacerbated population-level disparities in cognitive health,” the investigators add.

Another question concerns whether excessive Internet usage may actually be detrimental to neurocognitive outcomes. However, “existing evidence on the adverse effects of Internet usage is concentrated in younger populations whose brains are still undergoing maturation.”

Ms. Cho said the motivation for the study was the lack of longitudinal studies on this topic, especially those with sufficient follow-up periods. In addition, she said, there is insufficient evidence about how changes in Internet usage in older age are associated with prospective dementia risk.

For the study, investigators turned to participants in the Health and Retirement Study, an ongoing longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S.-based older adults (aged ≥ 50 years).

All participants (n = 18,154; 47.36% male; median age, 55.17 years) were dementia-free, community-dwelling older adults who completed a 2002 baseline cognitive assessment and were asked about Internet usage every 2 years thereafter.

Participants were followed from 2002 to 2018 for a maximum of 17.1 years (median, 7.9 years), which is the longest follow-up period to date. Of the total sample, 64.76% were regular Internet users.

The study’s primary outcome was incident dementia, based on performance on the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M), which was administered every 2 years.

The exposure examined in the study was cumulative Internet usage in late adulthood, defined as “the number of biennial waves where participants used the Internet regularly during the first three waves.”

In addition, participants were asked how many hours they spent using the Internet during the past week for activities other than viewing television shows or movies.

The researchers also investigated whether the link between Internet usage and dementia risk varied by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generational cohort.

Covariates included baseline TICS-M score, health, age, household income, marital status, and region of residence.

U-shaped curve

More than half of the sample (52.96%) showed no changes in Internet use from baseline during the study period, while one-fifth (20.54%) did show changes in use.

Investigators found a robust link between Internet usage and lower dementia risk (cause-specific hazard ratio, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46-0.71]) – a finding that remained even after adjusting for self-selection into baseline usage (csHR, 0.54 [0.41-0.72]) and signs of cognitive decline at baseline (csHR, 0.62 [0.46-0.85]).

Each additional wave of regular Internet usage was associated with a 21% decrease in the risk of dementia (95% CI, 13%-29%), wherein additional regular periods were associated with reduced dementia risk (csHR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]).

“The difference in risk between regular and nonregular users did not vary by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generation,” the investigators note.

A U-shaped association was found between daily hours of online engagement, wherein the lowest risk was observed in those with 0.1-2 hours of usage (compared with 0 hours of usage). The risk increased in a “monotonic fashion” after 2 hours, with 6.1-8 hours of usage showing the highest risk.

This finding was not considered statistically significant, but the “consistent U-shaped trend offers a preliminary suggestion that excessive online engagement may have adverse cognitive effects on older adults,” the investigators note.

“Among older adults, regular Internet users may experience a lower risk of dementia compared to nonregular users, and longer periods of regular Internet usage in late adulthood may help reduce the risks of subsequent dementia incidence,” said Ms. Cho. “Nonetheless, using the Internet excessively daily may negatively affect the risk of dementia in older adults.”

Bidirectional relationship?

Commenting for this article, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that some risk factors for Alzheimer’s or other dementias can’t be changed, while others are modifiable, “either at a personal or a population level.”

She called the current research “important” because it “identifies a potentially modifiable factor that may influence dementia risk.”

However, cautioned Dr. Sexton, who was not involved with the study, the findings cannot establish cause and effect. In fact, the relationship may be bidirectional.

“It may be that regular Internet usage is associated with increased cognitive stimulation, and in turn reduced risk of dementia; or it may be that individuals with lower risk of dementia are more likely to engage in regular Internet usage,” she said. Thus, “interventional studies are able to shed more light on causation.”

The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and is conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Ms. Cho, her coauthors, and Dr. Sexton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators followed more than 18,000 older individuals and found that regular Internet use was associated with about a 50% reduction in dementia risk, compared with their counterparts who did not use the Internet regularly.

They also found that longer duration of regular Internet use was associated with a reduced risk of dementia, although excessive daily Internet usage appeared to adversely affect dementia risk.

“Online engagement can develop and maintain cognitive reserve – resiliency against physiological damage to the brain – and increased cognitive reserve can, in turn, compensate for brain aging and reduce the risk of dementia,” study investigator Gawon Cho, a doctoral candidate at New York University School of Global Public Health, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Unexamined benefits

Prior research has shown that older adult Internet users have “better overall cognitive performance, verbal reasoning, and memory,” compared with nonusers, the authors note.

However, because this body of research consists of cross-sectional analyses and longitudinal studies with brief follow-up periods, the long-term cognitive benefits of Internet usage remain “unexamined.”

In addition, despite “extensive evidence of a disproportionately high burden of dementia in people of color, individuals without higher education, and adults who experienced other socioeconomic hardships, little is known about whether the Internet has exacerbated population-level disparities in cognitive health,” the investigators add.

Another question concerns whether excessive Internet usage may actually be detrimental to neurocognitive outcomes. However, “existing evidence on the adverse effects of Internet usage is concentrated in younger populations whose brains are still undergoing maturation.”

Ms. Cho said the motivation for the study was the lack of longitudinal studies on this topic, especially those with sufficient follow-up periods. In addition, she said, there is insufficient evidence about how changes in Internet usage in older age are associated with prospective dementia risk.

For the study, investigators turned to participants in the Health and Retirement Study, an ongoing longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S.-based older adults (aged ≥ 50 years).

All participants (n = 18,154; 47.36% male; median age, 55.17 years) were dementia-free, community-dwelling older adults who completed a 2002 baseline cognitive assessment and were asked about Internet usage every 2 years thereafter.

Participants were followed from 2002 to 2018 for a maximum of 17.1 years (median, 7.9 years), which is the longest follow-up period to date. Of the total sample, 64.76% were regular Internet users.

The study’s primary outcome was incident dementia, based on performance on the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M), which was administered every 2 years.

The exposure examined in the study was cumulative Internet usage in late adulthood, defined as “the number of biennial waves where participants used the Internet regularly during the first three waves.”

In addition, participants were asked how many hours they spent using the Internet during the past week for activities other than viewing television shows or movies.

The researchers also investigated whether the link between Internet usage and dementia risk varied by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generational cohort.

Covariates included baseline TICS-M score, health, age, household income, marital status, and region of residence.

U-shaped curve

More than half of the sample (52.96%) showed no changes in Internet use from baseline during the study period, while one-fifth (20.54%) did show changes in use.

Investigators found a robust link between Internet usage and lower dementia risk (cause-specific hazard ratio, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46-0.71]) – a finding that remained even after adjusting for self-selection into baseline usage (csHR, 0.54 [0.41-0.72]) and signs of cognitive decline at baseline (csHR, 0.62 [0.46-0.85]).

Each additional wave of regular Internet usage was associated with a 21% decrease in the risk of dementia (95% CI, 13%-29%), wherein additional regular periods were associated with reduced dementia risk (csHR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]).

“The difference in risk between regular and nonregular users did not vary by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generation,” the investigators note.

A U-shaped association was found between daily hours of online engagement, wherein the lowest risk was observed in those with 0.1-2 hours of usage (compared with 0 hours of usage). The risk increased in a “monotonic fashion” after 2 hours, with 6.1-8 hours of usage showing the highest risk.

This finding was not considered statistically significant, but the “consistent U-shaped trend offers a preliminary suggestion that excessive online engagement may have adverse cognitive effects on older adults,” the investigators note.

“Among older adults, regular Internet users may experience a lower risk of dementia compared to nonregular users, and longer periods of regular Internet usage in late adulthood may help reduce the risks of subsequent dementia incidence,” said Ms. Cho. “Nonetheless, using the Internet excessively daily may negatively affect the risk of dementia in older adults.”

Bidirectional relationship?

Commenting for this article, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that some risk factors for Alzheimer’s or other dementias can’t be changed, while others are modifiable, “either at a personal or a population level.”

She called the current research “important” because it “identifies a potentially modifiable factor that may influence dementia risk.”

However, cautioned Dr. Sexton, who was not involved with the study, the findings cannot establish cause and effect. In fact, the relationship may be bidirectional.

“It may be that regular Internet usage is associated with increased cognitive stimulation, and in turn reduced risk of dementia; or it may be that individuals with lower risk of dementia are more likely to engage in regular Internet usage,” she said. Thus, “interventional studies are able to shed more light on causation.”

The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and is conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Ms. Cho, her coauthors, and Dr. Sexton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators followed more than 18,000 older individuals and found that regular Internet use was associated with about a 50% reduction in dementia risk, compared with their counterparts who did not use the Internet regularly.

They also found that longer duration of regular Internet use was associated with a reduced risk of dementia, although excessive daily Internet usage appeared to adversely affect dementia risk.

“Online engagement can develop and maintain cognitive reserve – resiliency against physiological damage to the brain – and increased cognitive reserve can, in turn, compensate for brain aging and reduce the risk of dementia,” study investigator Gawon Cho, a doctoral candidate at New York University School of Global Public Health, said in an interview.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

Unexamined benefits

Prior research has shown that older adult Internet users have “better overall cognitive performance, verbal reasoning, and memory,” compared with nonusers, the authors note.

However, because this body of research consists of cross-sectional analyses and longitudinal studies with brief follow-up periods, the long-term cognitive benefits of Internet usage remain “unexamined.”

In addition, despite “extensive evidence of a disproportionately high burden of dementia in people of color, individuals without higher education, and adults who experienced other socioeconomic hardships, little is known about whether the Internet has exacerbated population-level disparities in cognitive health,” the investigators add.

Another question concerns whether excessive Internet usage may actually be detrimental to neurocognitive outcomes. However, “existing evidence on the adverse effects of Internet usage is concentrated in younger populations whose brains are still undergoing maturation.”

Ms. Cho said the motivation for the study was the lack of longitudinal studies on this topic, especially those with sufficient follow-up periods. In addition, she said, there is insufficient evidence about how changes in Internet usage in older age are associated with prospective dementia risk.

For the study, investigators turned to participants in the Health and Retirement Study, an ongoing longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of U.S.-based older adults (aged ≥ 50 years).

All participants (n = 18,154; 47.36% male; median age, 55.17 years) were dementia-free, community-dwelling older adults who completed a 2002 baseline cognitive assessment and were asked about Internet usage every 2 years thereafter.

Participants were followed from 2002 to 2018 for a maximum of 17.1 years (median, 7.9 years), which is the longest follow-up period to date. Of the total sample, 64.76% were regular Internet users.

The study’s primary outcome was incident dementia, based on performance on the Modified Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS-M), which was administered every 2 years.

The exposure examined in the study was cumulative Internet usage in late adulthood, defined as “the number of biennial waves where participants used the Internet regularly during the first three waves.”

In addition, participants were asked how many hours they spent using the Internet during the past week for activities other than viewing television shows or movies.

The researchers also investigated whether the link between Internet usage and dementia risk varied by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generational cohort.

Covariates included baseline TICS-M score, health, age, household income, marital status, and region of residence.

U-shaped curve

More than half of the sample (52.96%) showed no changes in Internet use from baseline during the study period, while one-fifth (20.54%) did show changes in use.

Investigators found a robust link between Internet usage and lower dementia risk (cause-specific hazard ratio, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.46-0.71]) – a finding that remained even after adjusting for self-selection into baseline usage (csHR, 0.54 [0.41-0.72]) and signs of cognitive decline at baseline (csHR, 0.62 [0.46-0.85]).

Each additional wave of regular Internet usage was associated with a 21% decrease in the risk of dementia (95% CI, 13%-29%), wherein additional regular periods were associated with reduced dementia risk (csHR, 0.80 [95% CI, 0.68-0.95]).

“The difference in risk between regular and nonregular users did not vary by educational attainment, race-ethnicity, sex, and generation,” the investigators note.

A U-shaped association was found between daily hours of online engagement, wherein the lowest risk was observed in those with 0.1-2 hours of usage (compared with 0 hours of usage). The risk increased in a “monotonic fashion” after 2 hours, with 6.1-8 hours of usage showing the highest risk.

This finding was not considered statistically significant, but the “consistent U-shaped trend offers a preliminary suggestion that excessive online engagement may have adverse cognitive effects on older adults,” the investigators note.

“Among older adults, regular Internet users may experience a lower risk of dementia compared to nonregular users, and longer periods of regular Internet usage in late adulthood may help reduce the risks of subsequent dementia incidence,” said Ms. Cho. “Nonetheless, using the Internet excessively daily may negatively affect the risk of dementia in older adults.”

Bidirectional relationship?

Commenting for this article, Claire Sexton, DPhil, Alzheimer’s Association senior director of scientific programs and outreach, noted that some risk factors for Alzheimer’s or other dementias can’t be changed, while others are modifiable, “either at a personal or a population level.”

She called the current research “important” because it “identifies a potentially modifiable factor that may influence dementia risk.”

However, cautioned Dr. Sexton, who was not involved with the study, the findings cannot establish cause and effect. In fact, the relationship may be bidirectional.

“It may be that regular Internet usage is associated with increased cognitive stimulation, and in turn reduced risk of dementia; or it may be that individuals with lower risk of dementia are more likely to engage in regular Internet usage,” she said. Thus, “interventional studies are able to shed more light on causation.”

The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and is conducted by the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Ms. Cho, her coauthors, and Dr. Sexton have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN GERIATRICS SOCIETY

Worsening cognitive impairments

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

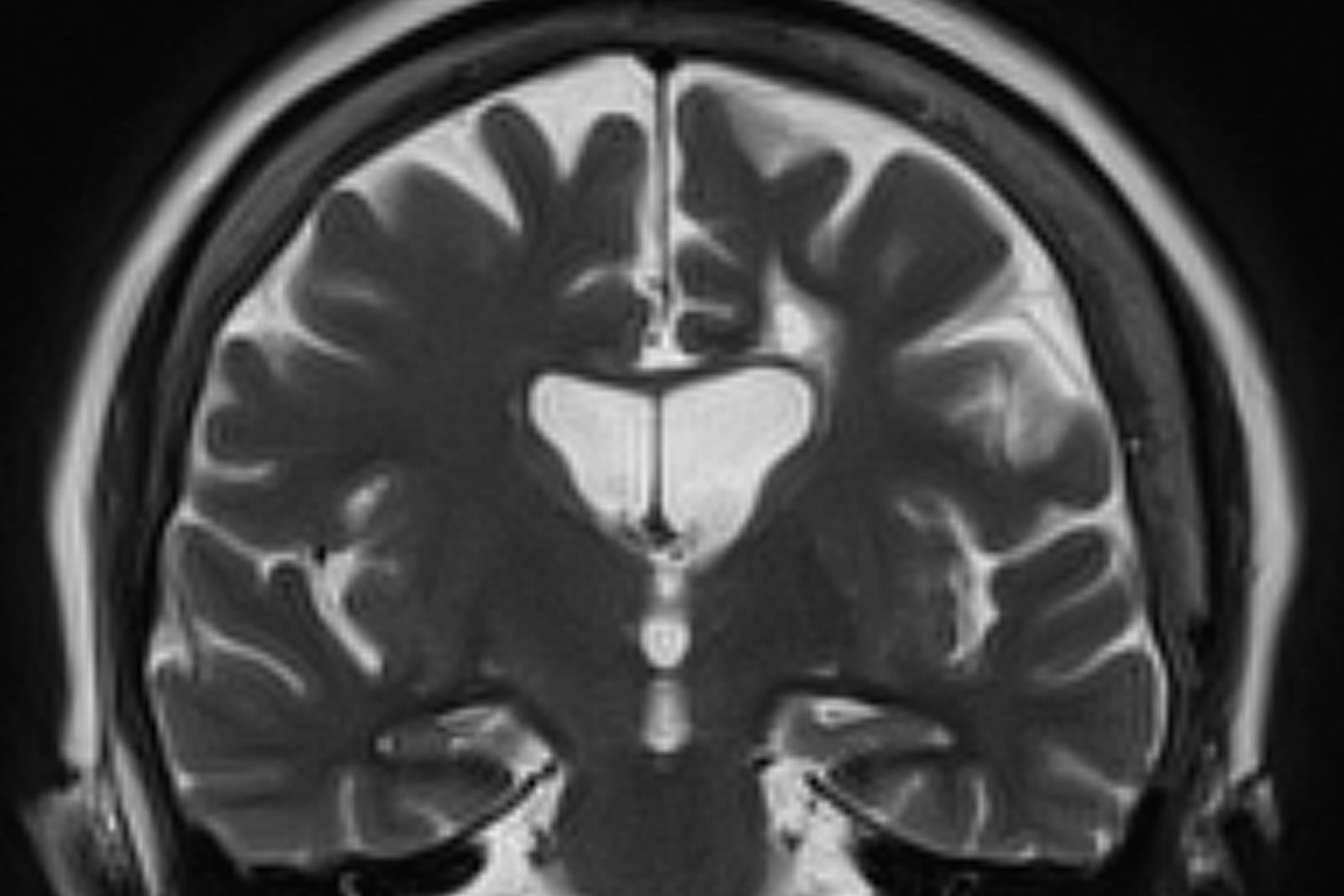

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

AD is the most common type of dementia. It is characterized by cognitive and behavioral impairment that significantly impairs a patient's social and occupational functioning. The predominant AD pathogenesis hypothesis suggests that AD is largely caused by the accumulation of insoluble amyloid beta deposits and neurofibrillary tangles induced by highly phosphorylated tau proteins in the neocortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, as well as significant loss of neurons and synapses, which leads to brain atrophy. Estimates suggest that approximately 6.2 million people ≥ 65 years of age have AD and that by 2060, the number of Americans with AD may increase to 13.8 million, the result of an aging population and the lack of effective prevention and treatment strategies. AD is a chronic disease that confers tremendous emotional and economic burdens to individuals, families, and society.

Insidiously progressive memory loss is commonly seen in patients presenting with AD. As the disease progresses over the course of several years, other areas of cognition are impaired. Patients may develop language disorders (eg, anomic aphasia or anomia) and impairment in visuospatial skills and executive functions. Slowly progressive behavioral changes are also observed in many individuals with AD.

Criteria for the clinical diagnosis of AD (eg, insidious onset of cognitive impairment, clear history of worsening symptoms) have been developed and are frequently employed. Among individuals who meet the core clinical criteria for probable AD dementia, biomarker evidence may help to increase the certainty that AD is the basis of the clinical dementia syndrome. Several cerebrospinal fluid and blood biomarkers have shown excellent diagnostic ability by identifying tau pathology and cerebral amyloid beta for AD. Neuroimaging is becoming increasingly important for identifying the underlying causes of cognitive impairment. Currently, MRI is considered the preferred neuroimaging modality for AD as it enables accurate measurement of the three-dimensional volume of brain structures, particularly the size of the hippocampus and related regions. CT may be used when MRI is not possible, such as in a patient with a pacemaker.

PET is increasingly being used as a noninvasive method for depicting tau pathology deposition and distribution in patients with cognitive impairment. In 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the first tau PET tracer, 18F-flortaucipir, a significant achievement in improving AD diagnosis.

Currently, the only therapies available for AD are symptomatic therapies. Cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist are the standard medical treatment for AD. Recently approved antiamyloid therapies are also available for patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. These include aducanumab, a first-in-class amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2021; and lecanemab, another amyloid beta–directed antibody that was approved in 2023. Both aducanumab and lecanemab are recommended for the treatment of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia stage of disease, the population in which the safety and efficacy of these newer agents were demonstrated in clinical trials.

Psychotropic agents are often used to treat the secondary symptoms of AD, such as depression, agitation, aggression, hallucinations, delusions, and/or sleep disorders, which can be problematic. Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Behavioral interventions, including patient-centered approaches and caregiver training, may also be beneficial for managing the cognitive and behavioral manifestations of AD. These modalities are often used in combination with pharmacologic interventions, such as anxiolytics for anxiety and agitation, neuroleptics for delusions or hallucinations, and antidepressants or mood stabilizers for mood disorders and specific manifestations (eg, episodes of anger or rage). Regular physical activity and exercise is also emerging as a potential strategy for delaying AD progression and possibly conferring a protective effect on brain health.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, Professor of Neurology, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood; Director, Clinical Neurophysiology Lab, Department of Neurology, Hines VA Hospital, Hines, IL.

Jasvinder Chawla, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 73-year-old male restaurant manager presents with concerns of progressively worsening cognitive impairment. The patient's symptoms began approximately 2 years ago. At that time, he attributed them to normal aging. Recently, however, he has begun to have increasing difficulties at work. On several occasions, he has forgotten to place important supply orders and has made errors with staff scheduling. His wife reports that he frequently misplaces items at home, such as his cell phone and car keys, and has been experiencing noticeable deficits with his short-term memory. In addition, he has been "unlike himself" for quite some time, with uncharacteristic episodes of depression, anxiety, and emotional lability. The patient's past medical history is significant for mild obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. There is no history of neurotoxic exposure, head injuries, strokes, or seizures. His family history is negative for dementia. Current medications include rosuvastatin 40 mg/d and metoprolol 100 mg/d. His current height and weight are 5 ft 11 in and 223 lb (BMI 31.1).

No abnormalities are noted on physical exam; the patient's blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and heart rate are within normal ranges. Laboratory tests are within normal ranges, except for elevated levels of fasting blood glucose level (119 mg/dL) and A1c (6.3%). The patient scores 19 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test. His clinician orders MRI scanning, which reveals generalized atrophy of brain tissue and an accentuated loss of tissue involving the temporal lobes.

Deep sleep may mitigate the impact of Alzheimer’s pathology

Investigators found that deep sleep, also known as non-REM (NREM) slow-wave sleep, can protect memory function in cognitively normal adults with a high beta-amyloid burden.

“Think of deep sleep almost like a life raft that keeps memory afloat, rather than memory getting dragged down by the weight of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” senior investigator Matthew Walker, PhD, professor of neuroscience and psychology, University of California, Berkeley, said in a news release.

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

Resilience factor

Studying resilience to existing brain pathology is “an exciting new research direction,” lead author Zsófia Zavecz, PhD, with the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview.

“That is, what factors explain the individual differences in cognitive function despite the same level of brain pathology, and how do some people with significant pathology have largely preserved memory?” she added.

The study included 62 cognitively normal older adults from the Berkeley Aging Cohort Study.

Sleep EEG recordings were obtained over 2 nights in a sleep lab and PET scans were used to quantify beta-amyloid. Half of the participants had high beta-amyloid burden and half were beta-amyloid negative.

After the sleep studies, all participants completed a memory task involving matching names to faces.

The results suggest that deep NREM slow-wave sleep significantly moderates the effect of beta-amyloid status on memory function.

Specifically, NREM slow-wave activity selectively supported superior memory function in adults with high beta-amyloid burden, who are most in need of cognitive reserve (B = 2.694, P = .019), the researchers report.

In contrast, adults without significant beta-amyloid pathological burden – and thus without the same need for cognitive reserve – did not similarly benefit from NREM slow-wave activity (B = –0.115, P = .876).

The findings remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, gray matter atrophy, and previously identified cognitive reserve factors, such as education and physical activity.

Dr. Zavecz said there are several potential reasons why deep sleep may support cognitive reserve.

One is that during deep sleep specifically, memories are replayed in the brain, and this results in a “neural reorganization” that helps stabilize the memory and make it more permanent.

“Other explanations include deep sleep’s role in maintaining homeostasis in the brain’s capacity to form new neural connections and providing an optimal brain state for the clearance of toxins interfering with healthy brain functioning,” she noted.

“The extent to which sleep could offer a protective buffer against severe cognitive impairment remains to be tested. However, this study is the first step in hopefully a series of new research that will investigate sleep as a cognitive reserve factor,” said Dr. Zavecz.

Encouraging data

Reached for comment, Percy Griffin, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, said although the study sample is small, the results are “encouraging because sleep is a modifiable factor and can therefore be targeted.”

“More work is needed in a larger population before we can fully leverage this stage of sleep to reduce the risk of developing cognitive decline,” Dr. Griffin said.

Also weighing in on this research, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher in Boston, said the study is “exciting on two fronts – we may have an additional marker for the development of Alzheimer’s disease to predict risk and track disease, but also targets for early intervention with sleep architecture–enhancing therapies, be they drug, device, or digital.”

“For the sake of our brain health, we all must get very familiar with the concept of cognitive or brain reserve,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved in the study.

“Brain reserve refers to our ability to buttress against the threat of dementia and classically it’s been associated with ongoing brain stimulation (i.e., higher education, cognitively demanding job),” he noted.

“This line of research now opens the door that optimal sleep health – especially deep NREM slow wave sleep – correlates with greater brain reserve against Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Walker serves as an advisor to and has equity interest in Bryte, Shuni, Oura, and StimScience. Dr. Zavecz and Dr. Lakhan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that deep sleep, also known as non-REM (NREM) slow-wave sleep, can protect memory function in cognitively normal adults with a high beta-amyloid burden.

“Think of deep sleep almost like a life raft that keeps memory afloat, rather than memory getting dragged down by the weight of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” senior investigator Matthew Walker, PhD, professor of neuroscience and psychology, University of California, Berkeley, said in a news release.

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

Resilience factor

Studying resilience to existing brain pathology is “an exciting new research direction,” lead author Zsófia Zavecz, PhD, with the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview.

“That is, what factors explain the individual differences in cognitive function despite the same level of brain pathology, and how do some people with significant pathology have largely preserved memory?” she added.

The study included 62 cognitively normal older adults from the Berkeley Aging Cohort Study.

Sleep EEG recordings were obtained over 2 nights in a sleep lab and PET scans were used to quantify beta-amyloid. Half of the participants had high beta-amyloid burden and half were beta-amyloid negative.

After the sleep studies, all participants completed a memory task involving matching names to faces.

The results suggest that deep NREM slow-wave sleep significantly moderates the effect of beta-amyloid status on memory function.

Specifically, NREM slow-wave activity selectively supported superior memory function in adults with high beta-amyloid burden, who are most in need of cognitive reserve (B = 2.694, P = .019), the researchers report.

In contrast, adults without significant beta-amyloid pathological burden – and thus without the same need for cognitive reserve – did not similarly benefit from NREM slow-wave activity (B = –0.115, P = .876).

The findings remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, gray matter atrophy, and previously identified cognitive reserve factors, such as education and physical activity.

Dr. Zavecz said there are several potential reasons why deep sleep may support cognitive reserve.

One is that during deep sleep specifically, memories are replayed in the brain, and this results in a “neural reorganization” that helps stabilize the memory and make it more permanent.

“Other explanations include deep sleep’s role in maintaining homeostasis in the brain’s capacity to form new neural connections and providing an optimal brain state for the clearance of toxins interfering with healthy brain functioning,” she noted.

“The extent to which sleep could offer a protective buffer against severe cognitive impairment remains to be tested. However, this study is the first step in hopefully a series of new research that will investigate sleep as a cognitive reserve factor,” said Dr. Zavecz.

Encouraging data

Reached for comment, Percy Griffin, PhD, Alzheimer’s Association director of scientific engagement, said although the study sample is small, the results are “encouraging because sleep is a modifiable factor and can therefore be targeted.”

“More work is needed in a larger population before we can fully leverage this stage of sleep to reduce the risk of developing cognitive decline,” Dr. Griffin said.

Also weighing in on this research, Shaheen Lakhan, MD, PhD, a neurologist and researcher in Boston, said the study is “exciting on two fronts – we may have an additional marker for the development of Alzheimer’s disease to predict risk and track disease, but also targets for early intervention with sleep architecture–enhancing therapies, be they drug, device, or digital.”

“For the sake of our brain health, we all must get very familiar with the concept of cognitive or brain reserve,” said Dr. Lakhan, who was not involved in the study.

“Brain reserve refers to our ability to buttress against the threat of dementia and classically it’s been associated with ongoing brain stimulation (i.e., higher education, cognitively demanding job),” he noted.

“This line of research now opens the door that optimal sleep health – especially deep NREM slow wave sleep – correlates with greater brain reserve against Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Lakhan said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Walker serves as an advisor to and has equity interest in Bryte, Shuni, Oura, and StimScience. Dr. Zavecz and Dr. Lakhan report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that deep sleep, also known as non-REM (NREM) slow-wave sleep, can protect memory function in cognitively normal adults with a high beta-amyloid burden.

“Think of deep sleep almost like a life raft that keeps memory afloat, rather than memory getting dragged down by the weight of Alzheimer’s disease pathology,” senior investigator Matthew Walker, PhD, professor of neuroscience and psychology, University of California, Berkeley, said in a news release.

The study was published online in BMC Medicine.

Resilience factor

Studying resilience to existing brain pathology is “an exciting new research direction,” lead author Zsófia Zavecz, PhD, with the Center for Human Sleep Science at the University of California, Berkeley, said in an interview.

“That is, what factors explain the individual differences in cognitive function despite the same level of brain pathology, and how do some people with significant pathology have largely preserved memory?” she added.

The study included 62 cognitively normal older adults from the Berkeley Aging Cohort Study.

Sleep EEG recordings were obtained over 2 nights in a sleep lab and PET scans were used to quantify beta-amyloid. Half of the participants had high beta-amyloid burden and half were beta-amyloid negative.

After the sleep studies, all participants completed a memory task involving matching names to faces.

The results suggest that deep NREM slow-wave sleep significantly moderates the effect of beta-amyloid status on memory function.

Specifically, NREM slow-wave activity selectively supported superior memory function in adults with high beta-amyloid burden, who are most in need of cognitive reserve (B = 2.694, P = .019), the researchers report.

In contrast, adults without significant beta-amyloid pathological burden – and thus without the same need for cognitive reserve – did not similarly benefit from NREM slow-wave activity (B = –0.115, P = .876).

The findings remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, gray matter atrophy, and previously identified cognitive reserve factors, such as education and physical activity.

Dr. Zavecz said there are several potential reasons why deep sleep may support cognitive reserve.

One is that during deep sleep specifically, memories are replayed in the brain, and this results in a “neural reorganization” that helps stabilize the memory and make it more permanent.

“Other explanations include deep sleep’s role in maintaining homeostasis in the brain’s capacity to form new neural connections and providing an optimal brain state for the clearance of toxins interfering with healthy brain functioning,” she noted.