User login

Can intraputamenal infusions of GDNF treat Parkinson’s disease?

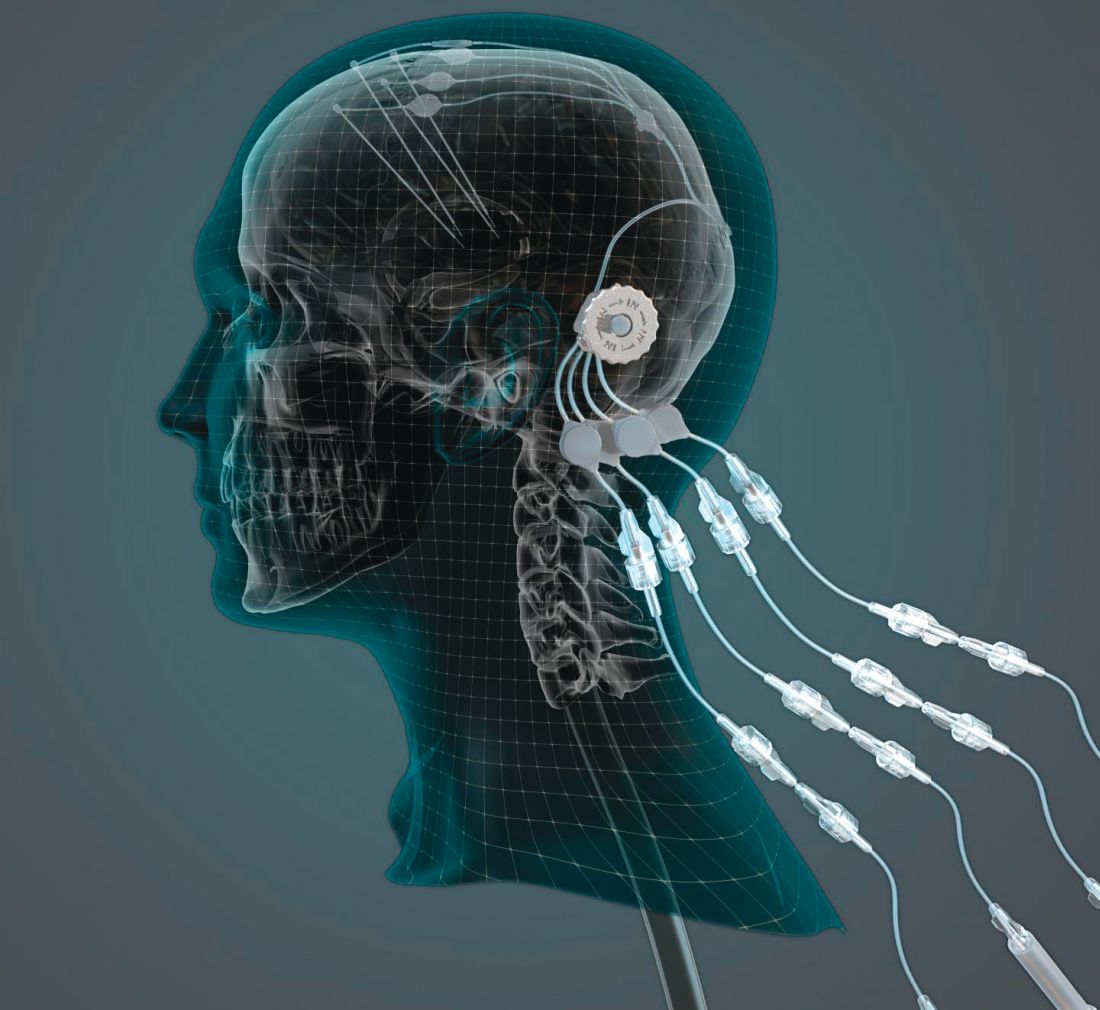

researchers reported. The investigational therapy, delivered through a skull-mounted port, was well tolerated in a 40-week, randomized, controlled trial and a 40-week, open-label extension.

Neither study met its primary endpoint, but post hoc analyses suggest possible clinical benefits. In addition, PET imaging after the 40-week, randomized trial found significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake in patients who received GDNF. The randomized trial was published in the March 2019 issue of Brain; data from the open-label extension were published online ahead of print Feb. 26, 2019, in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease.

“The spatial and relative magnitude of the improvement in the brain scans is beyond anything seen previously in trials of surgically delivered growth-factor treatments for Parkinson’s [disease],” said principal investigator Alan L. Whone, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol (England) and North Bristol National Health Service Trust. “This represents some of the most compelling evidence yet that we may have a means to possibly reawaken and restore the dopamine brain cells that are gradually destroyed in Parkinson’s [disease].”

Nevertheless, the trial did not confirm clinical benefits. The hypothesis that growth factors can benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease may be incorrect, the researchers acknowledged. It also is possible that the hypothesis is valid and that a trial with a higher GDNF dose, longer treatment duration, patients with an earlier disease stage, or different outcome measures would yield positive results. GDNF warrants further study, they wrote.

The findings could have implications for other neurologic disorders as well.

“This trial has shown that we can safely and repeatedly infuse drugs directly into patients’ brains over months or years. This is a significant breakthrough in our ability to treat neurologic conditions ... because most drugs that might work cannot cross from the bloodstream into the brain,” said Steven Gill, MB, MS. Mr. Gill, of the North Bristol NHS Trust and the U.K.-based engineering firm Renishaw, designed the convection-enhanced delivery system used in the studies.

A neurotrophic protein

GDNF has neurorestorative and neuroprotective effects in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. In open-label studies, continuous, low-rate intraputamenal administration of GDNF has shown signs of potential efficacy, but a placebo-controlled trial did not replicate clinical benefits. In the present studies, the researchers assessed intermittent GDNF administration using convection-enhanced delivery, which can achieve wider and more even distribution of GDNF, compared with the previous approach.

The researchers conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study this novel administration approach. Patients were aged 35-75 years, had motor symptoms for at least 5 years, and had moderate disease severity in the off state (that is, Hoehn and Yahr stage 2-3 and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor score–part III [UPDRS-III] of 25-45).

In a pilot stage of the trial, six patients were randomized 2:1 to receive GDNF (120 mcg per putamen) or placebo. In the primary stage, another 35 patients were randomized 1:1 to GDNF or placebo. The primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline to week 40 in the off-state UPDRS-III among patients from the primary stage of the trial. Further analyses included all 41 patients from the pilot and primary stages.

Patients in the primary analysis had a mean age of 56.4 years and mean disease duration of 10.9 years. About half were female.

Results on primary and secondary clinical endpoints did not significantly differ between the groups. Average off state UPDRS motor score decreased by 17.3 in the active treatment group, compared with 11.8 in the placebo group.

A post hoc analysis, however, found that nine patients (43%) in the active-treatment group had a large, clinically important motor improvement of 10 or more points in the off state, whereas no placebo patients did. These “10-point responders in the GDNF group are a potential focus of interest; however, as this is a post hoc finding we would not wish to overinterpret its meaning,” Dr. Whone and his colleagues wrote. Among patients who received GDNF, PET imaging demonstrated significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake throughout the putamen, ranging from a 25% increase in the left anterior putamen to a 100% increase in both posterior putamena, whereas patients who received placebo did not have significantly increased uptake.

No drug-related serious adverse events were reported. “The majority of device-related adverse events were port site associated, most commonly local hypertrophic scarring or infections, amenable to antibiotics,” the investigators wrote. “The frequency of these declined during the trial as surgical and device handling experience improved.”

Open-label extension

By week 80, when all participants had received GDNF, both groups showed moderate to large improvement in symptoms, compared with baseline. From baseline to week 80, percentage change in UPDRS motor score in the off state did not significantly differ between patients who received GDNF for 80 weeks and patients who received placebo followed by GDNF (26.7% vs. 27.6%). Secondary endpoints also did not differ between the groups. Treatment compliance was 97.8%; no patients discontinued the study.

The trials were funded by Parkinson’s UK with support from the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and in association with the North Bristol NHS Trust. GDNF and additional resources and funding were provided by MedGenesis Therapeutix, which owns the license for GDNF and received funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Renishaw manufactured the convection-enhanced delivery device on behalf of North Bristol NHS Trust. The Gatsby Foundation provided a 3T MRI scanner. Some study authors are employed by and have shares or share options with MedGenesis Therapeutix. Other authors are employees of Renishaw. Dr. Gill is Renishaw’s medical director and may have a future royalty share from the drug delivery system that he invented.

SOURCES: Whone AL et al. Brain. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz023; Whone AL et al. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191576.

researchers reported. The investigational therapy, delivered through a skull-mounted port, was well tolerated in a 40-week, randomized, controlled trial and a 40-week, open-label extension.

Neither study met its primary endpoint, but post hoc analyses suggest possible clinical benefits. In addition, PET imaging after the 40-week, randomized trial found significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake in patients who received GDNF. The randomized trial was published in the March 2019 issue of Brain; data from the open-label extension were published online ahead of print Feb. 26, 2019, in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease.

“The spatial and relative magnitude of the improvement in the brain scans is beyond anything seen previously in trials of surgically delivered growth-factor treatments for Parkinson’s [disease],” said principal investigator Alan L. Whone, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol (England) and North Bristol National Health Service Trust. “This represents some of the most compelling evidence yet that we may have a means to possibly reawaken and restore the dopamine brain cells that are gradually destroyed in Parkinson’s [disease].”

Nevertheless, the trial did not confirm clinical benefits. The hypothesis that growth factors can benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease may be incorrect, the researchers acknowledged. It also is possible that the hypothesis is valid and that a trial with a higher GDNF dose, longer treatment duration, patients with an earlier disease stage, or different outcome measures would yield positive results. GDNF warrants further study, they wrote.

The findings could have implications for other neurologic disorders as well.

“This trial has shown that we can safely and repeatedly infuse drugs directly into patients’ brains over months or years. This is a significant breakthrough in our ability to treat neurologic conditions ... because most drugs that might work cannot cross from the bloodstream into the brain,” said Steven Gill, MB, MS. Mr. Gill, of the North Bristol NHS Trust and the U.K.-based engineering firm Renishaw, designed the convection-enhanced delivery system used in the studies.

A neurotrophic protein

GDNF has neurorestorative and neuroprotective effects in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. In open-label studies, continuous, low-rate intraputamenal administration of GDNF has shown signs of potential efficacy, but a placebo-controlled trial did not replicate clinical benefits. In the present studies, the researchers assessed intermittent GDNF administration using convection-enhanced delivery, which can achieve wider and more even distribution of GDNF, compared with the previous approach.

The researchers conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study this novel administration approach. Patients were aged 35-75 years, had motor symptoms for at least 5 years, and had moderate disease severity in the off state (that is, Hoehn and Yahr stage 2-3 and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor score–part III [UPDRS-III] of 25-45).

In a pilot stage of the trial, six patients were randomized 2:1 to receive GDNF (120 mcg per putamen) or placebo. In the primary stage, another 35 patients were randomized 1:1 to GDNF or placebo. The primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline to week 40 in the off-state UPDRS-III among patients from the primary stage of the trial. Further analyses included all 41 patients from the pilot and primary stages.

Patients in the primary analysis had a mean age of 56.4 years and mean disease duration of 10.9 years. About half were female.

Results on primary and secondary clinical endpoints did not significantly differ between the groups. Average off state UPDRS motor score decreased by 17.3 in the active treatment group, compared with 11.8 in the placebo group.

A post hoc analysis, however, found that nine patients (43%) in the active-treatment group had a large, clinically important motor improvement of 10 or more points in the off state, whereas no placebo patients did. These “10-point responders in the GDNF group are a potential focus of interest; however, as this is a post hoc finding we would not wish to overinterpret its meaning,” Dr. Whone and his colleagues wrote. Among patients who received GDNF, PET imaging demonstrated significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake throughout the putamen, ranging from a 25% increase in the left anterior putamen to a 100% increase in both posterior putamena, whereas patients who received placebo did not have significantly increased uptake.

No drug-related serious adverse events were reported. “The majority of device-related adverse events were port site associated, most commonly local hypertrophic scarring or infections, amenable to antibiotics,” the investigators wrote. “The frequency of these declined during the trial as surgical and device handling experience improved.”

Open-label extension

By week 80, when all participants had received GDNF, both groups showed moderate to large improvement in symptoms, compared with baseline. From baseline to week 80, percentage change in UPDRS motor score in the off state did not significantly differ between patients who received GDNF for 80 weeks and patients who received placebo followed by GDNF (26.7% vs. 27.6%). Secondary endpoints also did not differ between the groups. Treatment compliance was 97.8%; no patients discontinued the study.

The trials were funded by Parkinson’s UK with support from the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and in association with the North Bristol NHS Trust. GDNF and additional resources and funding were provided by MedGenesis Therapeutix, which owns the license for GDNF and received funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Renishaw manufactured the convection-enhanced delivery device on behalf of North Bristol NHS Trust. The Gatsby Foundation provided a 3T MRI scanner. Some study authors are employed by and have shares or share options with MedGenesis Therapeutix. Other authors are employees of Renishaw. Dr. Gill is Renishaw’s medical director and may have a future royalty share from the drug delivery system that he invented.

SOURCES: Whone AL et al. Brain. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz023; Whone AL et al. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191576.

researchers reported. The investigational therapy, delivered through a skull-mounted port, was well tolerated in a 40-week, randomized, controlled trial and a 40-week, open-label extension.

Neither study met its primary endpoint, but post hoc analyses suggest possible clinical benefits. In addition, PET imaging after the 40-week, randomized trial found significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake in patients who received GDNF. The randomized trial was published in the March 2019 issue of Brain; data from the open-label extension were published online ahead of print Feb. 26, 2019, in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease.

“The spatial and relative magnitude of the improvement in the brain scans is beyond anything seen previously in trials of surgically delivered growth-factor treatments for Parkinson’s [disease],” said principal investigator Alan L. Whone, MBChB, PhD, of the University of Bristol (England) and North Bristol National Health Service Trust. “This represents some of the most compelling evidence yet that we may have a means to possibly reawaken and restore the dopamine brain cells that are gradually destroyed in Parkinson’s [disease].”

Nevertheless, the trial did not confirm clinical benefits. The hypothesis that growth factors can benefit patients with Parkinson’s disease may be incorrect, the researchers acknowledged. It also is possible that the hypothesis is valid and that a trial with a higher GDNF dose, longer treatment duration, patients with an earlier disease stage, or different outcome measures would yield positive results. GDNF warrants further study, they wrote.

The findings could have implications for other neurologic disorders as well.

“This trial has shown that we can safely and repeatedly infuse drugs directly into patients’ brains over months or years. This is a significant breakthrough in our ability to treat neurologic conditions ... because most drugs that might work cannot cross from the bloodstream into the brain,” said Steven Gill, MB, MS. Mr. Gill, of the North Bristol NHS Trust and the U.K.-based engineering firm Renishaw, designed the convection-enhanced delivery system used in the studies.

A neurotrophic protein

GDNF has neurorestorative and neuroprotective effects in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. In open-label studies, continuous, low-rate intraputamenal administration of GDNF has shown signs of potential efficacy, but a placebo-controlled trial did not replicate clinical benefits. In the present studies, the researchers assessed intermittent GDNF administration using convection-enhanced delivery, which can achieve wider and more even distribution of GDNF, compared with the previous approach.

The researchers conducted a single-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study this novel administration approach. Patients were aged 35-75 years, had motor symptoms for at least 5 years, and had moderate disease severity in the off state (that is, Hoehn and Yahr stage 2-3 and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor score–part III [UPDRS-III] of 25-45).

In a pilot stage of the trial, six patients were randomized 2:1 to receive GDNF (120 mcg per putamen) or placebo. In the primary stage, another 35 patients were randomized 1:1 to GDNF or placebo. The primary outcome was the percentage change from baseline to week 40 in the off-state UPDRS-III among patients from the primary stage of the trial. Further analyses included all 41 patients from the pilot and primary stages.

Patients in the primary analysis had a mean age of 56.4 years and mean disease duration of 10.9 years. About half were female.

Results on primary and secondary clinical endpoints did not significantly differ between the groups. Average off state UPDRS motor score decreased by 17.3 in the active treatment group, compared with 11.8 in the placebo group.

A post hoc analysis, however, found that nine patients (43%) in the active-treatment group had a large, clinically important motor improvement of 10 or more points in the off state, whereas no placebo patients did. These “10-point responders in the GDNF group are a potential focus of interest; however, as this is a post hoc finding we would not wish to overinterpret its meaning,” Dr. Whone and his colleagues wrote. Among patients who received GDNF, PET imaging demonstrated significantly increased 18F-DOPA uptake throughout the putamen, ranging from a 25% increase in the left anterior putamen to a 100% increase in both posterior putamena, whereas patients who received placebo did not have significantly increased uptake.

No drug-related serious adverse events were reported. “The majority of device-related adverse events were port site associated, most commonly local hypertrophic scarring or infections, amenable to antibiotics,” the investigators wrote. “The frequency of these declined during the trial as surgical and device handling experience improved.”

Open-label extension

By week 80, when all participants had received GDNF, both groups showed moderate to large improvement in symptoms, compared with baseline. From baseline to week 80, percentage change in UPDRS motor score in the off state did not significantly differ between patients who received GDNF for 80 weeks and patients who received placebo followed by GDNF (26.7% vs. 27.6%). Secondary endpoints also did not differ between the groups. Treatment compliance was 97.8%; no patients discontinued the study.

The trials were funded by Parkinson’s UK with support from the Cure Parkinson’s Trust and in association with the North Bristol NHS Trust. GDNF and additional resources and funding were provided by MedGenesis Therapeutix, which owns the license for GDNF and received funding from the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research. Renishaw manufactured the convection-enhanced delivery device on behalf of North Bristol NHS Trust. The Gatsby Foundation provided a 3T MRI scanner. Some study authors are employed by and have shares or share options with MedGenesis Therapeutix. Other authors are employees of Renishaw. Dr. Gill is Renishaw’s medical director and may have a future royalty share from the drug delivery system that he invented.

SOURCES: Whone AL et al. Brain. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz023; Whone AL et al. J Parkinsons Dis. 2019 Feb 26. doi: 10.3233/JPD-191576.

Does adherence to a Mediterranean diet reduce the risk of Parkinson’s disease?

Among older adults, adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, according to research published in Movement Disorders.

“Recommending the Mediterranean diet pattern, either to reduce the risk or lessen the effects ... of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, needs to be considered and further explored,” said lead author Maria I. Maraki, PhD, of the department of nutrition and dietetics at Harokopio University in Athens, Greece, and her research colleagues.

Evidence regarding the effect of a Mediterranean diet on Parkinson’s disease risk remains limited, however, and physicians should be cautious in interpreting the data, researchers noted in accompanying editorials.

“There is a puzzling constellation of information and data that cannot be reconciled with a simple model accounting for the role of diet, vascular risk factors, and the neurodegenerative process and mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease,” Connie Marras, MD, PhD, and Jose A. Obeso, MD, PhD, said in an editorial. Given Maraki et al.’s findings, “most of us would be glad to accept that such a causal inverse association exists and can therefore be strongly recommended to our patients,” but “further work is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached,” Dr. Marras and Dr. Obeso wrote. Dr. Marras is affiliated with the University Health Network and the University of Toronto. Dr. Obeso is affiliated with University Hospital HM Puerta del Sur, CEU San Pablo University, Móstoles, Spain.

The role of diet

Prior research has suggested that adherence to the Mediterranean diet – characterized by consumption of nonrefined cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, potatoes, fish, and olive oil – may be associated with reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, studies have found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet may be protective in other diseases, including dementia and cardiovascular disease. Dr. Maraki and her colleagues sought to assess whether adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the likelihood of prodromal Parkinson’s disease or its manifestations. To calculate the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the investigators used a tool created by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) that takes into account baseline risk factors as well as prodromal markers such as constipation and motor slowing.

They analyzed data from 1,731 participants in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece. Participants, 41% of whom were male, were aged 65 years or older and did not have Parkinson’s disease. They completed a detailed food frequency questionnaire, and the researchers calculated how closely each participant’s diet adhered to the Mediterranean diet. Diet adherence scores ranged from 0 to 55, with higher scores indicating greater adherence.

The median probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease was 1.9% (range, 0.2%-96.7%), and the probability was lower among those with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet. This difference was “driven mostly by nonmotor markers of prodromal Parkinson’s disease,” including depression, constipation, urinary dysfunction, and daytime somnolence, the researchers said. “Each unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.” Compared with participants in the lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence, those in the highest quartile had an approximately 21% lower probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Potential confounding

“This study pushes the prodromal criteria into performing a job they were never designed to do,” which presents potential pitfalls, Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of the department of neurology at Montreal General Hospital in Quebec, said in an accompanying editorial.

While the MDS criteria were designed to assess the likelihood that any person over age 50 years is in a state of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the present study aimed to evaluate whether a single putative risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is associated with the likelihood of its prodromal state.

In addition, the analysis did not include some of the prodromal markers that are part of the MDS criteria, including olfaction, polysomnographic-proven REM sleep behavior disorder, and dopaminergic functional neuroimaging.

“As pointed out by the researchers, many of the risk factors in the prodromal criteria are potentially confounded by factors other than Parkinson’s disease; for example, one could imagine that older people, men, or farmers (with their higher pesticide exposure) are less likely to follow the Mediterranean diet simply because of different cultural lifestyle patterns,” Dr. Postuma said.

It is also possible that the Mediterranean diet affects prodromal markers such as constipation, sleep, or depression without affecting underlying neurodegenerative disease. In any case, the effect sizes observed in the study were small, and there was no evidence that participants who adhered most closely to a Mediterranean diet had less parkinsonism, Dr. Postuma said.

These limitations do not preclude physicians from recommending the diet for other reasons. “Numerous studies, reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials consistently rank the Mediterranean diet as among the healthiest diets available,” Dr. Postuma said. “So, one can clearly recommend diets such as these, even if not necessarily for Parkinson’s disease prevention.”

Adding insights

The researchers used a Mediterranean diet score that was developed in a population of adults from metropolitan Athens, “an area not unlike the one in which the score is being applied in the HELIAD study,” Christy C. Tangney, PhD, professor of clinical nutrition and preventive medicine and associate dean for research at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said in a separate editorial. As expected, the average Mediterranean diet adherence score in this study was higher than that in the Chicago Health and Aging Project (33.2 vs. 28.2).

“If we can identify differences in diet or lifestyle patterns and risk of this latent phase of Parkinson’s disease neurodegeneration, we may be one step closer to identifying preventive measures,” she said. Follow-up reports from HELIAD and other cohorts may allow researchers to assess how changes in dietary patterns relate to changes in Parkinson’s disease markers, the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, and incident Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Tangney said.

The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation. Dr. Tangney and Dr. Postuma had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1002/mds.27489.

Among older adults, adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, according to research published in Movement Disorders.

“Recommending the Mediterranean diet pattern, either to reduce the risk or lessen the effects ... of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, needs to be considered and further explored,” said lead author Maria I. Maraki, PhD, of the department of nutrition and dietetics at Harokopio University in Athens, Greece, and her research colleagues.

Evidence regarding the effect of a Mediterranean diet on Parkinson’s disease risk remains limited, however, and physicians should be cautious in interpreting the data, researchers noted in accompanying editorials.

“There is a puzzling constellation of information and data that cannot be reconciled with a simple model accounting for the role of diet, vascular risk factors, and the neurodegenerative process and mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease,” Connie Marras, MD, PhD, and Jose A. Obeso, MD, PhD, said in an editorial. Given Maraki et al.’s findings, “most of us would be glad to accept that such a causal inverse association exists and can therefore be strongly recommended to our patients,” but “further work is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached,” Dr. Marras and Dr. Obeso wrote. Dr. Marras is affiliated with the University Health Network and the University of Toronto. Dr. Obeso is affiliated with University Hospital HM Puerta del Sur, CEU San Pablo University, Móstoles, Spain.

The role of diet

Prior research has suggested that adherence to the Mediterranean diet – characterized by consumption of nonrefined cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, potatoes, fish, and olive oil – may be associated with reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, studies have found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet may be protective in other diseases, including dementia and cardiovascular disease. Dr. Maraki and her colleagues sought to assess whether adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the likelihood of prodromal Parkinson’s disease or its manifestations. To calculate the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the investigators used a tool created by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) that takes into account baseline risk factors as well as prodromal markers such as constipation and motor slowing.

They analyzed data from 1,731 participants in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece. Participants, 41% of whom were male, were aged 65 years or older and did not have Parkinson’s disease. They completed a detailed food frequency questionnaire, and the researchers calculated how closely each participant’s diet adhered to the Mediterranean diet. Diet adherence scores ranged from 0 to 55, with higher scores indicating greater adherence.

The median probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease was 1.9% (range, 0.2%-96.7%), and the probability was lower among those with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet. This difference was “driven mostly by nonmotor markers of prodromal Parkinson’s disease,” including depression, constipation, urinary dysfunction, and daytime somnolence, the researchers said. “Each unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.” Compared with participants in the lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence, those in the highest quartile had an approximately 21% lower probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Potential confounding

“This study pushes the prodromal criteria into performing a job they were never designed to do,” which presents potential pitfalls, Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of the department of neurology at Montreal General Hospital in Quebec, said in an accompanying editorial.

While the MDS criteria were designed to assess the likelihood that any person over age 50 years is in a state of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the present study aimed to evaluate whether a single putative risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is associated with the likelihood of its prodromal state.

In addition, the analysis did not include some of the prodromal markers that are part of the MDS criteria, including olfaction, polysomnographic-proven REM sleep behavior disorder, and dopaminergic functional neuroimaging.

“As pointed out by the researchers, many of the risk factors in the prodromal criteria are potentially confounded by factors other than Parkinson’s disease; for example, one could imagine that older people, men, or farmers (with their higher pesticide exposure) are less likely to follow the Mediterranean diet simply because of different cultural lifestyle patterns,” Dr. Postuma said.

It is also possible that the Mediterranean diet affects prodromal markers such as constipation, sleep, or depression without affecting underlying neurodegenerative disease. In any case, the effect sizes observed in the study were small, and there was no evidence that participants who adhered most closely to a Mediterranean diet had less parkinsonism, Dr. Postuma said.

These limitations do not preclude physicians from recommending the diet for other reasons. “Numerous studies, reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials consistently rank the Mediterranean diet as among the healthiest diets available,” Dr. Postuma said. “So, one can clearly recommend diets such as these, even if not necessarily for Parkinson’s disease prevention.”

Adding insights

The researchers used a Mediterranean diet score that was developed in a population of adults from metropolitan Athens, “an area not unlike the one in which the score is being applied in the HELIAD study,” Christy C. Tangney, PhD, professor of clinical nutrition and preventive medicine and associate dean for research at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said in a separate editorial. As expected, the average Mediterranean diet adherence score in this study was higher than that in the Chicago Health and Aging Project (33.2 vs. 28.2).

“If we can identify differences in diet or lifestyle patterns and risk of this latent phase of Parkinson’s disease neurodegeneration, we may be one step closer to identifying preventive measures,” she said. Follow-up reports from HELIAD and other cohorts may allow researchers to assess how changes in dietary patterns relate to changes in Parkinson’s disease markers, the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, and incident Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Tangney said.

The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation. Dr. Tangney and Dr. Postuma had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1002/mds.27489.

Among older adults, adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, according to research published in Movement Disorders.

“Recommending the Mediterranean diet pattern, either to reduce the risk or lessen the effects ... of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, needs to be considered and further explored,” said lead author Maria I. Maraki, PhD, of the department of nutrition and dietetics at Harokopio University in Athens, Greece, and her research colleagues.

Evidence regarding the effect of a Mediterranean diet on Parkinson’s disease risk remains limited, however, and physicians should be cautious in interpreting the data, researchers noted in accompanying editorials.

“There is a puzzling constellation of information and data that cannot be reconciled with a simple model accounting for the role of diet, vascular risk factors, and the neurodegenerative process and mechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease,” Connie Marras, MD, PhD, and Jose A. Obeso, MD, PhD, said in an editorial. Given Maraki et al.’s findings, “most of us would be glad to accept that such a causal inverse association exists and can therefore be strongly recommended to our patients,” but “further work is needed before definitive conclusions can be reached,” Dr. Marras and Dr. Obeso wrote. Dr. Marras is affiliated with the University Health Network and the University of Toronto. Dr. Obeso is affiliated with University Hospital HM Puerta del Sur, CEU San Pablo University, Móstoles, Spain.

The role of diet

Prior research has suggested that adherence to the Mediterranean diet – characterized by consumption of nonrefined cereals, fruits, vegetables, legumes, potatoes, fish, and olive oil – may be associated with reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease. In addition, studies have found that adherence to the Mediterranean diet may be protective in other diseases, including dementia and cardiovascular disease. Dr. Maraki and her colleagues sought to assess whether adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with the likelihood of prodromal Parkinson’s disease or its manifestations. To calculate the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the investigators used a tool created by the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) that takes into account baseline risk factors as well as prodromal markers such as constipation and motor slowing.

They analyzed data from 1,731 participants in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece. Participants, 41% of whom were male, were aged 65 years or older and did not have Parkinson’s disease. They completed a detailed food frequency questionnaire, and the researchers calculated how closely each participant’s diet adhered to the Mediterranean diet. Diet adherence scores ranged from 0 to 55, with higher scores indicating greater adherence.

The median probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease was 1.9% (range, 0.2%-96.7%), and the probability was lower among those with greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet. This difference was “driven mostly by nonmotor markers of prodromal Parkinson’s disease,” including depression, constipation, urinary dysfunction, and daytime somnolence, the researchers said. “Each unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.” Compared with participants in the lowest quartile of Mediterranean diet adherence, those in the highest quartile had an approximately 21% lower probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Potential confounding

“This study pushes the prodromal criteria into performing a job they were never designed to do,” which presents potential pitfalls, Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of the department of neurology at Montreal General Hospital in Quebec, said in an accompanying editorial.

While the MDS criteria were designed to assess the likelihood that any person over age 50 years is in a state of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, the present study aimed to evaluate whether a single putative risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is associated with the likelihood of its prodromal state.

In addition, the analysis did not include some of the prodromal markers that are part of the MDS criteria, including olfaction, polysomnographic-proven REM sleep behavior disorder, and dopaminergic functional neuroimaging.

“As pointed out by the researchers, many of the risk factors in the prodromal criteria are potentially confounded by factors other than Parkinson’s disease; for example, one could imagine that older people, men, or farmers (with their higher pesticide exposure) are less likely to follow the Mediterranean diet simply because of different cultural lifestyle patterns,” Dr. Postuma said.

It is also possible that the Mediterranean diet affects prodromal markers such as constipation, sleep, or depression without affecting underlying neurodegenerative disease. In any case, the effect sizes observed in the study were small, and there was no evidence that participants who adhered most closely to a Mediterranean diet had less parkinsonism, Dr. Postuma said.

These limitations do not preclude physicians from recommending the diet for other reasons. “Numerous studies, reviews, meta-analyses, and randomized controlled trials consistently rank the Mediterranean diet as among the healthiest diets available,” Dr. Postuma said. “So, one can clearly recommend diets such as these, even if not necessarily for Parkinson’s disease prevention.”

Adding insights

The researchers used a Mediterranean diet score that was developed in a population of adults from metropolitan Athens, “an area not unlike the one in which the score is being applied in the HELIAD study,” Christy C. Tangney, PhD, professor of clinical nutrition and preventive medicine and associate dean for research at Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, said in a separate editorial. As expected, the average Mediterranean diet adherence score in this study was higher than that in the Chicago Health and Aging Project (33.2 vs. 28.2).

“If we can identify differences in diet or lifestyle patterns and risk of this latent phase of Parkinson’s disease neurodegeneration, we may be one step closer to identifying preventive measures,” she said. Follow-up reports from HELIAD and other cohorts may allow researchers to assess how changes in dietary patterns relate to changes in Parkinson’s disease markers, the probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease, and incident Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Tangney said.

The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation. Dr. Tangney and Dr. Postuma had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi: 10.1002/mds.27489.

FROM MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Key clinical point: Adherence to a Mediterranean diet is associated with lower probability of prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Major finding: Each 1-unit increase in Mediterranean diet score was associated with a 2% decreased probability for prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

Study details: A study of 1,731 older adults in the population-based Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) cohort in Greece.

Disclosures: The study authors had no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. The study was supported by a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, an ESPA‐EU grant cofunded by the European Social Fund and Greek National resources, and a grant from the Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity (Greece). Dr. Maraki and a coauthor have received financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation.

Source: Maraki MI et al. Mov Disord. 2018 Oct 10. doi:10.1002/mds.27489.

Researchers compare focused ultrasound and DBS for essential tremor

LAS VEGAS – according to two presentations delivered at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. The techniques’ surgical procedures, associated risks, and adverse event profiles may influence neurologists and patients in their choice of treatment.

FUS allows neurosurgeons to apply thermal ablation to create a lesion on the thalamus. MRI guidance enables precise control of the lesion location (within approximately 1 mm) and of the treatment intensity. The surgery can be performed with high-resolution stereotactic framing.

DBS entails the surgical implantation of a neurostimulator and attached leads and electrodes. The neurosurgeon drills a hole of approximately 14 mm in diameter into the skull so that the electrode can be inserted stereotactically while the patient is awake or asleep. The neurostimulator is installed separately.

Both treatments provide functional benefits

In 2016, W. Jeff Elias, MD, director of stereotactic and functional neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, and his colleagues published the results of a randomized controlled trial that compared FUS with sham treatment in 76 patients with essential tremor. At three months, hand tremor had improved by approximately 50% among treated patients, but controls had no significant benefit(N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375[8]:730-9). The improvement among treated patients was maintained for 12 months. Disability and quality of life also improved after FUS.

A study by Schuurman et al. published in 2000 (N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 17;342[7]:461-8) showed that DBS and FUS had similar efficacy at 1 year, said Kathryn L. Holloway, MD, professor of neurosurgery at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. It included 45 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 13 with essential tremor, and 10 with multiple sclerosis who were randomized 1:1 to FUS or DBS. The primary outcome was activities of daily living, and blinded physicians assessed patient videos. Most of the patients who improved had received DBS, and most of the ones who worsened had received FUS, said Dr. Holloway. Among patients with essential tremor, tremor improved by between 94% and 100% with either treatment.

To find more recent data about these treatments, Dr. Holloway searched the literature for studies of FUS or DBS for essential tremor. She analyzed only studies that included unselected populations, blinded evaluations within 1 or 2 years of surgery, and tremor scores for the treated side. She found two studies of FUS, including Dr. Elias’s 2016 trial and a 2018 follow-up (Ann Neurol. 2018 Jan;83[1]:107-14). Dr. Holloway also identified three trials of DBS.

In these studies, reduction of hand tremor was 55% with FUS and between 63% and 69% with DBS. Reduction of postural tremor was approximately 72% with FUS and approximately 67% with DBS. Reduction of action tremor was about 52% with FUS and between 65% and 71% with DBS. Overall, DBS appears to be more effective, said Dr. Holloway.

A 2015 study (Mov Disord. 2015 Dec;30[14]:1937-43) that compared bilateral DBS, unilateral DBS, and unilateral FUS for essential tremor indicated that the treatments provide similar benefits on hand tremor, disability, and quality of life, said Dr. Elias. FUS is inferior to DBS, however, for total tremor and axial tremor.

Furthermore, the efficacy of FUS wanes over time, said Dr. Elias. He and his colleagues conducted a pilot study of 15 patients with essential tremor who received FUS (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 15;369[7]:640-8). At 6 years, 6 of 13 patients whose data were available still had a 50% improvement in tremor. “Some went on to [receive] DBS,” said Dr. Elias. “Functional improvements persisted more than the tremor improvement.”

Adverse events

In their 2016 trial of FUS, Dr. Elias and his colleagues observed 210 adverse events, which is approximately “what you would expect with a modern day, FDA-monitored clinical trial.” Sensory effects and gait disturbance accounted for most of the thalamotomy-related adverse events. Sensory problems such as numbness or parestheisa persisted at 1 year in 14% of treated patients, and gait disturbance persisted at 1 year in 9%. The investigators did not observe any hemorrhages, infections, or cavitation-related effects from FUS.

In a 2018 analysis of five clinical trials of FUS for essential tremor, Fishman et al. found that 79% of adverse events were mild and 1% were severe (Mov Disord. 2018 May;33[5]:843-7). The risk of a severe adverse event therefore can be considered low, and it may decrease as neurosurgeons gain experience with the procedure, said Dr. Elias.

In the 2000 Schuurman et al. study, the researchers observed significantly fewer adverse events overall among patients with Parkinson’s disease or essential tremor who received DBS, compared with patients who received FUS. Cognitive deterioration, severe dysarthria, and severe ataxia were more common in the FUS group than in the DBS group. Dr. Holloway’s analysis of adverse events in the five more recent trials that she identified yielded similar results.

Although MRI-guided FUS is a precise way to make lesions, functional areas in the thalamus overlap, which makes it more difficult to target only the intended region, said Dr. Holloway. The functional overlap thus increases the risk of adverse events (e.g., sensory impairments, dysarthria, or ataxia). The adverse events that result from FUS may last as long as a year. “Patients will put up anything for about a month after surgery, and then they start to get annoyed,” said Dr. Holloway.

In addition, Schuurman et al. found that FUS entailed a greater risk of permanent side effects, compared with DBS. “That’s the key point here,” said Dr. Holloway. Most of the adverse effects in the DBS group were resolved by adjusting or turning off the stimulator. Hardware issues resulting from DBS are frustrating, but reversible, but a patient with an adverse event after FUS often is “stuck with it,” said Dr. Holloway. The Schuurman et al. data indicated that, in terms of adverse events, “thalamotomy was inferior to DBS,” she added.

Implantation of DBS entails the risks inherent to surgeries that open the skull (such as seizures, air embolism, and hemorrhage). DBS entails a 2% risk of hemorrhage or infection, said Dr. Elias. Furthermore, as much as 15% of patients who undergo DBS implantation require additional surgery.

“FUS is not going to cause a life-threatening hemorrhage, but DBS certainly can,” said Dr. Holloway.

Managing disease progression

Essential tremor is a progressive disease, and older patients are more likely to have exponential progression than linear progression. Data, such as those published by Zhang et al. (J Neurosurg. 2010 Jun;112[6]:1271-6), indicate that DBS can “keep up with the progression of the disease,” said Dr. Holloway. The authors found that tremor scores did not change significantly over approximately 5 years when patients with essential tremor who had received DBS implantation had periodic assessments and increases in stimulation parameters when appropriate.

If a patient with essential tremor undergoes FUS thalamotomy and has subsequent disease progression, DBS may be considered for reducing tremor, said Dr. Holloway. Most adverse events resulting from DBS implantation are reversible with adjustment of the stimulation parameters. A second thalamotomy, however, could cause severe dysarthria and other irreversible adverse events. “Only DBS can safely address tremor progression,” said Dr. Holloway.

LAS VEGAS – according to two presentations delivered at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. The techniques’ surgical procedures, associated risks, and adverse event profiles may influence neurologists and patients in their choice of treatment.

FUS allows neurosurgeons to apply thermal ablation to create a lesion on the thalamus. MRI guidance enables precise control of the lesion location (within approximately 1 mm) and of the treatment intensity. The surgery can be performed with high-resolution stereotactic framing.

DBS entails the surgical implantation of a neurostimulator and attached leads and electrodes. The neurosurgeon drills a hole of approximately 14 mm in diameter into the skull so that the electrode can be inserted stereotactically while the patient is awake or asleep. The neurostimulator is installed separately.

Both treatments provide functional benefits

In 2016, W. Jeff Elias, MD, director of stereotactic and functional neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, and his colleagues published the results of a randomized controlled trial that compared FUS with sham treatment in 76 patients with essential tremor. At three months, hand tremor had improved by approximately 50% among treated patients, but controls had no significant benefit(N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375[8]:730-9). The improvement among treated patients was maintained for 12 months. Disability and quality of life also improved after FUS.

A study by Schuurman et al. published in 2000 (N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 17;342[7]:461-8) showed that DBS and FUS had similar efficacy at 1 year, said Kathryn L. Holloway, MD, professor of neurosurgery at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. It included 45 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 13 with essential tremor, and 10 with multiple sclerosis who were randomized 1:1 to FUS or DBS. The primary outcome was activities of daily living, and blinded physicians assessed patient videos. Most of the patients who improved had received DBS, and most of the ones who worsened had received FUS, said Dr. Holloway. Among patients with essential tremor, tremor improved by between 94% and 100% with either treatment.

To find more recent data about these treatments, Dr. Holloway searched the literature for studies of FUS or DBS for essential tremor. She analyzed only studies that included unselected populations, blinded evaluations within 1 or 2 years of surgery, and tremor scores for the treated side. She found two studies of FUS, including Dr. Elias’s 2016 trial and a 2018 follow-up (Ann Neurol. 2018 Jan;83[1]:107-14). Dr. Holloway also identified three trials of DBS.

In these studies, reduction of hand tremor was 55% with FUS and between 63% and 69% with DBS. Reduction of postural tremor was approximately 72% with FUS and approximately 67% with DBS. Reduction of action tremor was about 52% with FUS and between 65% and 71% with DBS. Overall, DBS appears to be more effective, said Dr. Holloway.

A 2015 study (Mov Disord. 2015 Dec;30[14]:1937-43) that compared bilateral DBS, unilateral DBS, and unilateral FUS for essential tremor indicated that the treatments provide similar benefits on hand tremor, disability, and quality of life, said Dr. Elias. FUS is inferior to DBS, however, for total tremor and axial tremor.

Furthermore, the efficacy of FUS wanes over time, said Dr. Elias. He and his colleagues conducted a pilot study of 15 patients with essential tremor who received FUS (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 15;369[7]:640-8). At 6 years, 6 of 13 patients whose data were available still had a 50% improvement in tremor. “Some went on to [receive] DBS,” said Dr. Elias. “Functional improvements persisted more than the tremor improvement.”

Adverse events

In their 2016 trial of FUS, Dr. Elias and his colleagues observed 210 adverse events, which is approximately “what you would expect with a modern day, FDA-monitored clinical trial.” Sensory effects and gait disturbance accounted for most of the thalamotomy-related adverse events. Sensory problems such as numbness or parestheisa persisted at 1 year in 14% of treated patients, and gait disturbance persisted at 1 year in 9%. The investigators did not observe any hemorrhages, infections, or cavitation-related effects from FUS.

In a 2018 analysis of five clinical trials of FUS for essential tremor, Fishman et al. found that 79% of adverse events were mild and 1% were severe (Mov Disord. 2018 May;33[5]:843-7). The risk of a severe adverse event therefore can be considered low, and it may decrease as neurosurgeons gain experience with the procedure, said Dr. Elias.

In the 2000 Schuurman et al. study, the researchers observed significantly fewer adverse events overall among patients with Parkinson’s disease or essential tremor who received DBS, compared with patients who received FUS. Cognitive deterioration, severe dysarthria, and severe ataxia were more common in the FUS group than in the DBS group. Dr. Holloway’s analysis of adverse events in the five more recent trials that she identified yielded similar results.

Although MRI-guided FUS is a precise way to make lesions, functional areas in the thalamus overlap, which makes it more difficult to target only the intended region, said Dr. Holloway. The functional overlap thus increases the risk of adverse events (e.g., sensory impairments, dysarthria, or ataxia). The adverse events that result from FUS may last as long as a year. “Patients will put up anything for about a month after surgery, and then they start to get annoyed,” said Dr. Holloway.

In addition, Schuurman et al. found that FUS entailed a greater risk of permanent side effects, compared with DBS. “That’s the key point here,” said Dr. Holloway. Most of the adverse effects in the DBS group were resolved by adjusting or turning off the stimulator. Hardware issues resulting from DBS are frustrating, but reversible, but a patient with an adverse event after FUS often is “stuck with it,” said Dr. Holloway. The Schuurman et al. data indicated that, in terms of adverse events, “thalamotomy was inferior to DBS,” she added.

Implantation of DBS entails the risks inherent to surgeries that open the skull (such as seizures, air embolism, and hemorrhage). DBS entails a 2% risk of hemorrhage or infection, said Dr. Elias. Furthermore, as much as 15% of patients who undergo DBS implantation require additional surgery.

“FUS is not going to cause a life-threatening hemorrhage, but DBS certainly can,” said Dr. Holloway.

Managing disease progression

Essential tremor is a progressive disease, and older patients are more likely to have exponential progression than linear progression. Data, such as those published by Zhang et al. (J Neurosurg. 2010 Jun;112[6]:1271-6), indicate that DBS can “keep up with the progression of the disease,” said Dr. Holloway. The authors found that tremor scores did not change significantly over approximately 5 years when patients with essential tremor who had received DBS implantation had periodic assessments and increases in stimulation parameters when appropriate.

If a patient with essential tremor undergoes FUS thalamotomy and has subsequent disease progression, DBS may be considered for reducing tremor, said Dr. Holloway. Most adverse events resulting from DBS implantation are reversible with adjustment of the stimulation parameters. A second thalamotomy, however, could cause severe dysarthria and other irreversible adverse events. “Only DBS can safely address tremor progression,” said Dr. Holloway.

LAS VEGAS – according to two presentations delivered at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. The techniques’ surgical procedures, associated risks, and adverse event profiles may influence neurologists and patients in their choice of treatment.

FUS allows neurosurgeons to apply thermal ablation to create a lesion on the thalamus. MRI guidance enables precise control of the lesion location (within approximately 1 mm) and of the treatment intensity. The surgery can be performed with high-resolution stereotactic framing.

DBS entails the surgical implantation of a neurostimulator and attached leads and electrodes. The neurosurgeon drills a hole of approximately 14 mm in diameter into the skull so that the electrode can be inserted stereotactically while the patient is awake or asleep. The neurostimulator is installed separately.

Both treatments provide functional benefits

In 2016, W. Jeff Elias, MD, director of stereotactic and functional neurosurgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, and his colleagues published the results of a randomized controlled trial that compared FUS with sham treatment in 76 patients with essential tremor. At three months, hand tremor had improved by approximately 50% among treated patients, but controls had no significant benefit(N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375[8]:730-9). The improvement among treated patients was maintained for 12 months. Disability and quality of life also improved after FUS.

A study by Schuurman et al. published in 2000 (N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 17;342[7]:461-8) showed that DBS and FUS had similar efficacy at 1 year, said Kathryn L. Holloway, MD, professor of neurosurgery at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. It included 45 patients with Parkinson’s disease, 13 with essential tremor, and 10 with multiple sclerosis who were randomized 1:1 to FUS or DBS. The primary outcome was activities of daily living, and blinded physicians assessed patient videos. Most of the patients who improved had received DBS, and most of the ones who worsened had received FUS, said Dr. Holloway. Among patients with essential tremor, tremor improved by between 94% and 100% with either treatment.

To find more recent data about these treatments, Dr. Holloway searched the literature for studies of FUS or DBS for essential tremor. She analyzed only studies that included unselected populations, blinded evaluations within 1 or 2 years of surgery, and tremor scores for the treated side. She found two studies of FUS, including Dr. Elias’s 2016 trial and a 2018 follow-up (Ann Neurol. 2018 Jan;83[1]:107-14). Dr. Holloway also identified three trials of DBS.

In these studies, reduction of hand tremor was 55% with FUS and between 63% and 69% with DBS. Reduction of postural tremor was approximately 72% with FUS and approximately 67% with DBS. Reduction of action tremor was about 52% with FUS and between 65% and 71% with DBS. Overall, DBS appears to be more effective, said Dr. Holloway.

A 2015 study (Mov Disord. 2015 Dec;30[14]:1937-43) that compared bilateral DBS, unilateral DBS, and unilateral FUS for essential tremor indicated that the treatments provide similar benefits on hand tremor, disability, and quality of life, said Dr. Elias. FUS is inferior to DBS, however, for total tremor and axial tremor.

Furthermore, the efficacy of FUS wanes over time, said Dr. Elias. He and his colleagues conducted a pilot study of 15 patients with essential tremor who received FUS (N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 15;369[7]:640-8). At 6 years, 6 of 13 patients whose data were available still had a 50% improvement in tremor. “Some went on to [receive] DBS,” said Dr. Elias. “Functional improvements persisted more than the tremor improvement.”

Adverse events

In their 2016 trial of FUS, Dr. Elias and his colleagues observed 210 adverse events, which is approximately “what you would expect with a modern day, FDA-monitored clinical trial.” Sensory effects and gait disturbance accounted for most of the thalamotomy-related adverse events. Sensory problems such as numbness or parestheisa persisted at 1 year in 14% of treated patients, and gait disturbance persisted at 1 year in 9%. The investigators did not observe any hemorrhages, infections, or cavitation-related effects from FUS.

In a 2018 analysis of five clinical trials of FUS for essential tremor, Fishman et al. found that 79% of adverse events were mild and 1% were severe (Mov Disord. 2018 May;33[5]:843-7). The risk of a severe adverse event therefore can be considered low, and it may decrease as neurosurgeons gain experience with the procedure, said Dr. Elias.

In the 2000 Schuurman et al. study, the researchers observed significantly fewer adverse events overall among patients with Parkinson’s disease or essential tremor who received DBS, compared with patients who received FUS. Cognitive deterioration, severe dysarthria, and severe ataxia were more common in the FUS group than in the DBS group. Dr. Holloway’s analysis of adverse events in the five more recent trials that she identified yielded similar results.

Although MRI-guided FUS is a precise way to make lesions, functional areas in the thalamus overlap, which makes it more difficult to target only the intended region, said Dr. Holloway. The functional overlap thus increases the risk of adverse events (e.g., sensory impairments, dysarthria, or ataxia). The adverse events that result from FUS may last as long as a year. “Patients will put up anything for about a month after surgery, and then they start to get annoyed,” said Dr. Holloway.

In addition, Schuurman et al. found that FUS entailed a greater risk of permanent side effects, compared with DBS. “That’s the key point here,” said Dr. Holloway. Most of the adverse effects in the DBS group were resolved by adjusting or turning off the stimulator. Hardware issues resulting from DBS are frustrating, but reversible, but a patient with an adverse event after FUS often is “stuck with it,” said Dr. Holloway. The Schuurman et al. data indicated that, in terms of adverse events, “thalamotomy was inferior to DBS,” she added.

Implantation of DBS entails the risks inherent to surgeries that open the skull (such as seizures, air embolism, and hemorrhage). DBS entails a 2% risk of hemorrhage or infection, said Dr. Elias. Furthermore, as much as 15% of patients who undergo DBS implantation require additional surgery.

“FUS is not going to cause a life-threatening hemorrhage, but DBS certainly can,” said Dr. Holloway.

Managing disease progression

Essential tremor is a progressive disease, and older patients are more likely to have exponential progression than linear progression. Data, such as those published by Zhang et al. (J Neurosurg. 2010 Jun;112[6]:1271-6), indicate that DBS can “keep up with the progression of the disease,” said Dr. Holloway. The authors found that tremor scores did not change significantly over approximately 5 years when patients with essential tremor who had received DBS implantation had periodic assessments and increases in stimulation parameters when appropriate.

If a patient with essential tremor undergoes FUS thalamotomy and has subsequent disease progression, DBS may be considered for reducing tremor, said Dr. Holloway. Most adverse events resulting from DBS implantation are reversible with adjustment of the stimulation parameters. A second thalamotomy, however, could cause severe dysarthria and other irreversible adverse events. “Only DBS can safely address tremor progression,” said Dr. Holloway.

REPORTING FROM NANS 2019

DBS may improve nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease

LAS VEGAS – , according to a small study presented at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN), however, does not significantly improve these symptoms.

“Further work will be needed to confirm whether DBS needs to be bilateral ... and whether demographic differences are significant,” said Michael Gillogly, RN, clinical research nurse in the department of neurosurgery at Albany (New York) Medical Center. “The pilot data suggest that, if all else is equal, and the patient has significant urinary dysfunction as a major complaint, GPI DBS may be preferentially considered.”

The benefits of DBS on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease are well documented in the literature, but the technique’s effects on nonmotor symptoms are less clear. Nonmotor symptoms – such as cognitive deficits, gastrointestinal dysfunction, genitourinary dysfunction, and sleep disturbance – are common in all stages of Parkinson’s disease and significantly impair quality of life. Data indicate that speech and neuropsychological symptoms worsen with DBS of the STN, but research into the effect of DBS of the GPI on nonmotor symptoms is limited.

Mr. Gillogly and his colleagues considered all surgical candidates at their facility for enrollment into a study evaluating nonmotor outcomes in Parkinson’s disease at baseline, before implantation, and at 6 months after DBS. Study outcomes were patient perception of urinary, swallowing, and gastrointestinal function at 6 months after DBS of the GPI, compared with DBS of the STN.

The researchers chose two tools each to measure sialorrhea, dysphagia, and genitourinary dysfunction. These tools included the Drooling Severity and Frequency Scale (DSFS), the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire, and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). The investigators also collected demographic information, including sex, age at the time of surgery, duration of illness, neuropsychological profile, and medication inventory.

In all, 34 patients (12 women) were enrolled in the study and completed each outcome measure preoperatively and at 6 months postoperatively. The mean age of our subjects at the time of surgery was 64 years. Eight received DBS of the GPI, and 26 received DBS of the STN. Mr. Gillogly and his colleagues observed a significant 31% improvement in DSFS score and a significant 24% improvement on the IPSS among GPI-targeted patients. They found no significant improvements among patients who had STN targeting. When the investigators compared patients with unilateral lead placement and those with bilateral lead placement, they observed that all of the significant improvement among patients with GPI targeting occurred when treatment was bilateral.

The small sample size is a notable limitation of the study, and subset analyses were limited, said Mr. Gillogly. In addition, it was difficult to determine whether the symptoms studied were directly related to Parkinson’s disease, because they often arise as part of the natural aging process. “Other limitations of the study include lack of objective measurements, as these are all patient perception, and the innate limitations of self-reported questionnaires,” said Mr. Gillogly.

Two of the researchers reported having consulted for Medtronic, which markets a DBS system. One author received grant funding and consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Abbott, all of which make DBS devices.

LAS VEGAS – , according to a small study presented at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN), however, does not significantly improve these symptoms.

“Further work will be needed to confirm whether DBS needs to be bilateral ... and whether demographic differences are significant,” said Michael Gillogly, RN, clinical research nurse in the department of neurosurgery at Albany (New York) Medical Center. “The pilot data suggest that, if all else is equal, and the patient has significant urinary dysfunction as a major complaint, GPI DBS may be preferentially considered.”

The benefits of DBS on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease are well documented in the literature, but the technique’s effects on nonmotor symptoms are less clear. Nonmotor symptoms – such as cognitive deficits, gastrointestinal dysfunction, genitourinary dysfunction, and sleep disturbance – are common in all stages of Parkinson’s disease and significantly impair quality of life. Data indicate that speech and neuropsychological symptoms worsen with DBS of the STN, but research into the effect of DBS of the GPI on nonmotor symptoms is limited.

Mr. Gillogly and his colleagues considered all surgical candidates at their facility for enrollment into a study evaluating nonmotor outcomes in Parkinson’s disease at baseline, before implantation, and at 6 months after DBS. Study outcomes were patient perception of urinary, swallowing, and gastrointestinal function at 6 months after DBS of the GPI, compared with DBS of the STN.

The researchers chose two tools each to measure sialorrhea, dysphagia, and genitourinary dysfunction. These tools included the Drooling Severity and Frequency Scale (DSFS), the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire, and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). The investigators also collected demographic information, including sex, age at the time of surgery, duration of illness, neuropsychological profile, and medication inventory.

In all, 34 patients (12 women) were enrolled in the study and completed each outcome measure preoperatively and at 6 months postoperatively. The mean age of our subjects at the time of surgery was 64 years. Eight received DBS of the GPI, and 26 received DBS of the STN. Mr. Gillogly and his colleagues observed a significant 31% improvement in DSFS score and a significant 24% improvement on the IPSS among GPI-targeted patients. They found no significant improvements among patients who had STN targeting. When the investigators compared patients with unilateral lead placement and those with bilateral lead placement, they observed that all of the significant improvement among patients with GPI targeting occurred when treatment was bilateral.

The small sample size is a notable limitation of the study, and subset analyses were limited, said Mr. Gillogly. In addition, it was difficult to determine whether the symptoms studied were directly related to Parkinson’s disease, because they often arise as part of the natural aging process. “Other limitations of the study include lack of objective measurements, as these are all patient perception, and the innate limitations of self-reported questionnaires,” said Mr. Gillogly.

Two of the researchers reported having consulted for Medtronic, which markets a DBS system. One author received grant funding and consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Abbott, all of which make DBS devices.

LAS VEGAS – , according to a small study presented at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus (STN), however, does not significantly improve these symptoms.

“Further work will be needed to confirm whether DBS needs to be bilateral ... and whether demographic differences are significant,” said Michael Gillogly, RN, clinical research nurse in the department of neurosurgery at Albany (New York) Medical Center. “The pilot data suggest that, if all else is equal, and the patient has significant urinary dysfunction as a major complaint, GPI DBS may be preferentially considered.”

The benefits of DBS on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease are well documented in the literature, but the technique’s effects on nonmotor symptoms are less clear. Nonmotor symptoms – such as cognitive deficits, gastrointestinal dysfunction, genitourinary dysfunction, and sleep disturbance – are common in all stages of Parkinson’s disease and significantly impair quality of life. Data indicate that speech and neuropsychological symptoms worsen with DBS of the STN, but research into the effect of DBS of the GPI on nonmotor symptoms is limited.

Mr. Gillogly and his colleagues considered all surgical candidates at their facility for enrollment into a study evaluating nonmotor outcomes in Parkinson’s disease at baseline, before implantation, and at 6 months after DBS. Study outcomes were patient perception of urinary, swallowing, and gastrointestinal function at 6 months after DBS of the GPI, compared with DBS of the STN.

The researchers chose two tools each to measure sialorrhea, dysphagia, and genitourinary dysfunction. These tools included the Drooling Severity and Frequency Scale (DSFS), the Swallowing Disturbance Questionnaire, and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). The investigators also collected demographic information, including sex, age at the time of surgery, duration of illness, neuropsychological profile, and medication inventory.

In all, 34 patients (12 women) were enrolled in the study and completed each outcome measure preoperatively and at 6 months postoperatively. The mean age of our subjects at the time of surgery was 64 years. Eight received DBS of the GPI, and 26 received DBS of the STN. Mr. Gillogly and his colleagues observed a significant 31% improvement in DSFS score and a significant 24% improvement on the IPSS among GPI-targeted patients. They found no significant improvements among patients who had STN targeting. When the investigators compared patients with unilateral lead placement and those with bilateral lead placement, they observed that all of the significant improvement among patients with GPI targeting occurred when treatment was bilateral.

The small sample size is a notable limitation of the study, and subset analyses were limited, said Mr. Gillogly. In addition, it was difficult to determine whether the symptoms studied were directly related to Parkinson’s disease, because they often arise as part of the natural aging process. “Other limitations of the study include lack of objective measurements, as these are all patient perception, and the innate limitations of self-reported questionnaires,” said Mr. Gillogly.

Two of the researchers reported having consulted for Medtronic, which markets a DBS system. One author received grant funding and consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Abbott, all of which make DBS devices.

REPORTING FROM NANS 2019

Key clinical point: Bilateral stimulation of the globus pallidus internus reduces sialorrhea and improves genitourinary symptoms.

Major finding: Patients reported 31% improvement in sialorrhea and 24% improvement in urinary function.

Study details: A prospective study of 34 patients receiving DBS of the STN or GPI.

Disclosures: No funding was reported.

Peripheral nerve stimulation reduces hand tremor

LAS VEGAS – In addition, sensors worn on the wrist can provide objective measures of tremor in the home environment, said the investigators, who presented their research at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society.

The current hypothesis is that tremulous activity within a central tremor network causes essential tremor, but the specific mechanisms are unknown. Research suggests that invasive neuromodulation of deep brain structures within this tremor network provides clinical benefit. The question of whether noninvasive neuromodulation of the peripheral nerve inputs connected to this network is beneficial has received comparatively little attention, however.

Rajesh Pahwa, MD, movement disorders division chief at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, and his colleagues examined the safety and efficacy of noninvasive neuromodulation for hand tremor in patients with essential tremor. To provide treatment, they used a wristband with three electrodes that targeted the median and radial nerves. The stimulation pattern was adjusted to interrupt each patient’s tremulous signal in the clinical setting and at home. Participants were asked to hold a certain posture for 20 seconds while the device recorded tremor frequency. After determining the peak tremor frequency, the device was able to adapt stimulation parameters to each patient.

Dr. Pahwa and his colleagues conducted an acute in-office study and an at-home study. In the in-office study, 77 participants were randomized to peripheral nerve treatment or sham stimulation of the tremor-dominant hand. The researchers evaluated tremor before and after one stimulation session using the Essential Tremor Rating Assessment Scale (TETRAS) Upper Limb Tremor Scale and the TETRAS Archimedes Spiral Rating Scale. In the at-home study, 61 participants were randomized to stimulation, sham, or standard of care for 2 weeks. After that point, all participants underwent two to five 40-minute stimulation sessions daily for 2 weeks. Patients in the treatment and sham groups had at least two sessions per day.

In the in-office study, the researchers randomized 40 patients to stimulation and 37 patients to sham. Dr. Pahwa and his colleagues determined that participants had been blinded successfully. The investigators observed a mean improvement in forward posture of approximately 0.75 points among treated patients, compared with a mean improvement of 0.3 points in the sham group. The difference between groups was statistically significant. Treated patients had significant improvements in upper limb tremor score and total performance score, compared with the sham group. The investigators also observed greater mean improvements in spiral drawing, lateral posture, and movement among treated patients, compared with the sham group, but the differences were not statistically significant.

Participants in the in-office study rated their improvement on activities of daily living. Average improvement across tasks was significantly greater for the treated group, compared to the sham group. Improvement on each individual task also was greater for the treated group than the sham group. The differences in improvement were significant for holding a cup of tea, dialing a telephone, picking up change, and unlocking a door with a key.