User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Spot Lumbar Spinal Stenosis From Across the Room

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis display a distinctive gait and posture that are of great assistance in diagnosing this common low back/leg pain syndrome.

"I find that in the supermarket I can identify persons with symptomatic lumbar stenosis because they lean forward on the cart and have a characteristic wide-based gait. The gait reflects poor balance. In essence the feet are not communicating effectively with the brain because of compression of proprioceptive fibers," Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz explained at the meeting.

The clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) requires both the appropriate clinical picture and the radiographic finding of lumbar spinal canal narrowing on cross-sectional imaging. The radiographic narrowing typically is caused by three pathoanatomic abnormalities occurring together: thickening of the normally paper-thin ligamentum flavum, facet joint osteoarthritis, and disc protrusion.

Radiographic evidence of lumbar spinal canal narrowing is necessary but not sufficient to diagnose the clinical syndrome of LSS. That’s because many individuals with anatomic stenosis don’t have the signs and symptoms of LSS, much as MRI studies have shown that a herniated lumbar disc is present in close to one-third of asymptomatic individuals, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine, orthopedic surgery, and epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

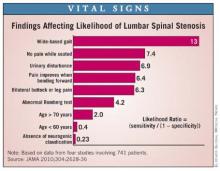

The clinical history and physical examination are invaluable in helping establish the diagnosis of LSS. Dr. Katz and coworkers analyzed data from four published studies involving 741 patients with radiographic evidence of anatomic stenosis to generate a list of predictors of increased likelihood of the syndrome of LSS in an individual patient (JAMA 2010;304:2628-36).

This analysis showed that among the most useful findings for ruling in the diagnosis are a wide-based gait, which confers a likelihood ratio of 13; lack of pain when seated, with an associated likelihood ratio of 7.4; and improvement of symptoms when bending forward, with a likelihood ratio of 6.4.

Patients with LSS typically have pain or discomfort with walking or prolonged standing. The pain radiates into the buttocks, often bilaterally, while extending below the knee far less often. Their polyradiculopathy is often at multiple levels, as distinguished from the monoradicular, well-demarcated pain affecting one of several key dermatomes that’s typical in patients with a herniated disc. Also characteristic of many patients with LSS is a pseudocerebellar syndrome marked by the wide-based gait, unsteadiness, and a positive Romberg test resulting from involvement of the posterior spinal column, he continued.

The differential diagnosis for LSS is lengthy. It includes hip osteoarthritis, trochanteric bursitis, iliopsoas bursitis, stenosis of the cervical spinal canal, pelvic or sacral insufficiency fracture, muscle strain or tears, vascular claudication, myofascial referred pain, and facet arthropathy without stenosis.

"The problem is not that any of the diagnoses on the differential list is particularly difficult to identify, but rather that they can often coexist. In the office, I do a lot of local injections into the trochanteric bursa to try to understand what’s really causing a patient’s symptoms," Dr. Katz said.

Accurate identification of patients who have LSS is paramount because the disorder’s natural history is distinctly different from other common causes of low back pain, including lumbago and a herniated lumbar disc. As a result of these divergent natural history trajectories, the preferred treatment of LSS differs from that for the other conditions. Indeed, LSS is the No.1 indication for spinal surgery beyond age 65 years (JAMA 2010; 303:1259-65).

Dr. Katz reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis display a distinctive gait and posture that are of great assistance in diagnosing this common low back/leg pain syndrome.

"I find that in the supermarket I can identify persons with symptomatic lumbar stenosis because they lean forward on the cart and have a characteristic wide-based gait. The gait reflects poor balance. In essence the feet are not communicating effectively with the brain because of compression of proprioceptive fibers," Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz explained at the meeting.

The clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) requires both the appropriate clinical picture and the radiographic finding of lumbar spinal canal narrowing on cross-sectional imaging. The radiographic narrowing typically is caused by three pathoanatomic abnormalities occurring together: thickening of the normally paper-thin ligamentum flavum, facet joint osteoarthritis, and disc protrusion.

Radiographic evidence of lumbar spinal canal narrowing is necessary but not sufficient to diagnose the clinical syndrome of LSS. That’s because many individuals with anatomic stenosis don’t have the signs and symptoms of LSS, much as MRI studies have shown that a herniated lumbar disc is present in close to one-third of asymptomatic individuals, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine, orthopedic surgery, and epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The clinical history and physical examination are invaluable in helping establish the diagnosis of LSS. Dr. Katz and coworkers analyzed data from four published studies involving 741 patients with radiographic evidence of anatomic stenosis to generate a list of predictors of increased likelihood of the syndrome of LSS in an individual patient (JAMA 2010;304:2628-36).

This analysis showed that among the most useful findings for ruling in the diagnosis are a wide-based gait, which confers a likelihood ratio of 13; lack of pain when seated, with an associated likelihood ratio of 7.4; and improvement of symptoms when bending forward, with a likelihood ratio of 6.4.

Patients with LSS typically have pain or discomfort with walking or prolonged standing. The pain radiates into the buttocks, often bilaterally, while extending below the knee far less often. Their polyradiculopathy is often at multiple levels, as distinguished from the monoradicular, well-demarcated pain affecting one of several key dermatomes that’s typical in patients with a herniated disc. Also characteristic of many patients with LSS is a pseudocerebellar syndrome marked by the wide-based gait, unsteadiness, and a positive Romberg test resulting from involvement of the posterior spinal column, he continued.

The differential diagnosis for LSS is lengthy. It includes hip osteoarthritis, trochanteric bursitis, iliopsoas bursitis, stenosis of the cervical spinal canal, pelvic or sacral insufficiency fracture, muscle strain or tears, vascular claudication, myofascial referred pain, and facet arthropathy without stenosis.

"The problem is not that any of the diagnoses on the differential list is particularly difficult to identify, but rather that they can often coexist. In the office, I do a lot of local injections into the trochanteric bursa to try to understand what’s really causing a patient’s symptoms," Dr. Katz said.

Accurate identification of patients who have LSS is paramount because the disorder’s natural history is distinctly different from other common causes of low back pain, including lumbago and a herniated lumbar disc. As a result of these divergent natural history trajectories, the preferred treatment of LSS differs from that for the other conditions. Indeed, LSS is the No.1 indication for spinal surgery beyond age 65 years (JAMA 2010; 303:1259-65).

Dr. Katz reported having no financial conflicts.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis display a distinctive gait and posture that are of great assistance in diagnosing this common low back/leg pain syndrome.

"I find that in the supermarket I can identify persons with symptomatic lumbar stenosis because they lean forward on the cart and have a characteristic wide-based gait. The gait reflects poor balance. In essence the feet are not communicating effectively with the brain because of compression of proprioceptive fibers," Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz explained at the meeting.

The clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) requires both the appropriate clinical picture and the radiographic finding of lumbar spinal canal narrowing on cross-sectional imaging. The radiographic narrowing typically is caused by three pathoanatomic abnormalities occurring together: thickening of the normally paper-thin ligamentum flavum, facet joint osteoarthritis, and disc protrusion.

Radiographic evidence of lumbar spinal canal narrowing is necessary but not sufficient to diagnose the clinical syndrome of LSS. That’s because many individuals with anatomic stenosis don’t have the signs and symptoms of LSS, much as MRI studies have shown that a herniated lumbar disc is present in close to one-third of asymptomatic individuals, according to Dr. Katz, professor of medicine, orthopedic surgery, and epidemiology at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

The clinical history and physical examination are invaluable in helping establish the diagnosis of LSS. Dr. Katz and coworkers analyzed data from four published studies involving 741 patients with radiographic evidence of anatomic stenosis to generate a list of predictors of increased likelihood of the syndrome of LSS in an individual patient (JAMA 2010;304:2628-36).

This analysis showed that among the most useful findings for ruling in the diagnosis are a wide-based gait, which confers a likelihood ratio of 13; lack of pain when seated, with an associated likelihood ratio of 7.4; and improvement of symptoms when bending forward, with a likelihood ratio of 6.4.

Patients with LSS typically have pain or discomfort with walking or prolonged standing. The pain radiates into the buttocks, often bilaterally, while extending below the knee far less often. Their polyradiculopathy is often at multiple levels, as distinguished from the monoradicular, well-demarcated pain affecting one of several key dermatomes that’s typical in patients with a herniated disc. Also characteristic of many patients with LSS is a pseudocerebellar syndrome marked by the wide-based gait, unsteadiness, and a positive Romberg test resulting from involvement of the posterior spinal column, he continued.

The differential diagnosis for LSS is lengthy. It includes hip osteoarthritis, trochanteric bursitis, iliopsoas bursitis, stenosis of the cervical spinal canal, pelvic or sacral insufficiency fracture, muscle strain or tears, vascular claudication, myofascial referred pain, and facet arthropathy without stenosis.

"The problem is not that any of the diagnoses on the differential list is particularly difficult to identify, but rather that they can often coexist. In the office, I do a lot of local injections into the trochanteric bursa to try to understand what’s really causing a patient’s symptoms," Dr. Katz said.

Accurate identification of patients who have LSS is paramount because the disorder’s natural history is distinctly different from other common causes of low back pain, including lumbago and a herniated lumbar disc. As a result of these divergent natural history trajectories, the preferred treatment of LSS differs from that for the other conditions. Indeed, LSS is the No.1 indication for spinal surgery beyond age 65 years (JAMA 2010; 303:1259-65).

Dr. Katz reported having no financial conflicts.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM A SYMPOSIUM SPONSORED BY THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Beware Skyrocketing Knee Arthroplasty Rates in Younger Patients

The incidence of total knee arthroplasties increased from 0.5 operations per 100,000 inhabitants to 65 operations per 100,000 inhabitants aged 30-59 years during 1980-2006 in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis, according to a Finnish study.

Patients born shortly after World War II showed the most dramatic increases.

Incidences of unicondylar or partial knee arthroplasties (UKAs) were also found to grow from 0.2 operations per 100,000 inhabitants to 10 operations per 100,000 inhabitants over the same period in the same Finnish patient age group.

"This phenomenon has been especially strong during the 21st century. There is no single explanatory factor for this growth. Some of the increase in incidence can be explained by hospital volume," wrote Dr. Jarkko Leskinen, Consultant Orthopedic Surgeon, Peijas Hospital, Helsinki University Central Hospital, who was lead author of the study published in the January issue of Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:423-8).

"The demand for primary TKA [total knee arthroplasty] has been estimated to grow by 673 percent to 3.48 million procedures in the United States by the year 2030," reported Dr. Leskinen. Previous studies reported increases in the incidence of TKA in younger patients in Australia and the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. This study aimed to analyze the changes in age group as well as the sex-standardized incidence of UKAs and TKAs in Finland between the years 1980 and 2006.

Patient data were drawn from the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry, and population data were obtained from Statistics Finland. A total of 8,961 knee arthroplasties were performed for primary osteoarthritis in patients under age 60 during 1980-2006. In addition to evaluating the effects of age and gender on the incidences of knee arthroplasties, Dr. Leskinen and his colleagues evaluated the effects of hospital volume.

Overall, the incidence rate ratio (IRR) for the annual increase in general incidence of UKAs was lower than that of TKAs, with an IRR of 1.26 for UKAs (95% confidence interval, 1.24-1.28; P less than .001) and 6.92 for TKAs (95% CI, 6.50-7.36; P less than .001).

In particular, the study found that the TKA incidence rose sharply from 18 per 100,000 in 2001 to 65 per 100,000 in 2006. TKAs were performed more often in women than men, with a 1.6- to 2.4-fold higher incidence in women than men during the past 10 years. Since 2000, a greater number of UKAs also were performed in women than men. Most of the increased incidence in TKAs and UKAs was in women aged 50-59 years.

Regarding the incidence of TKAs by age group, patients aged 50-59 years showed the largest increase, from 1.5 TKAs per 100,000 in 1980 to 160 per 100,000 in 2006. Incidences of UKAs by age group showed a similar pattern to TKAs, with the most marked growth in patients aged 50-59 years, increasing from 0.5 to 24 operations per 100,000. Growth was most rapid after the year 2000.

"Possible explanations for this phenomenon include the high functional and quality of life demands of younger patients aged less than 60 years," the authors wrote. "Another reason could be that the baby boomers may opt for elective operations at an earlier stage with milder symptoms, than the situation that was faced by earlier generations."

Hospitals were divided into low-, intermediate-, and high-volume centers, according to the number of TKAs performed in all the hospitals in Finland in 2006. The incidence of TKAs grew more rapidly in low- and intermediate-volume hospitals, while the incidence of UKAs grew in low-volume hospitals. The IRR for TKAs was 1.23 in both comparisons of low- to high-volume centers (95% CI, 1.13-1.34; P less than .001), and intermediate- to high-volume centers (95%CI, 1.16-1.31; P less than .001).

The authors warned against the widespread use of TKAs in younger patients. "Long-term results in young patients may differ from those reported in older patients, and risk for revision may be higher," they concluded.

Dr. Leskinen and his colleagues reported having no financial disclosures.

Intensive study of the outcomes of total knee arthroscopy in patients younger than 60 years is merited, given the expansion of indications involving TKA, according to Elena Losina, Ph.D., and Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz.

"Since younger patients are likely to be more physically active, to have more strenuous physical demands, and to make treatment choices that support an active lifestyle, the longevity or ‘survival’ of knee implants in this group may be lower than in older patients."

"The greater risk of implant failure in younger patients, coupled with longer remaining life expectancy in this age group, will combine to produce even higher rates of revision TKA in this population of TKA recipients," they added.

Most of the excellent outcomes in TKA have been seen in patients in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, wrote Dr. Losina and Dr. Katz. Few studies have investigated outcomes of TKAs and UKAs in those under age 60 and in those with less severe conditions. "While TKA has been shown to dramatically improve functional status and reduce pain in persons with severe pain and functional limitation, would similar dramatic improvements be observed in those who decide to undergo surgery with less severe functional impairment?" they wrote.

Dr. Losina is codirector of the Orthopedic and Arthritis Center for Outcomes Research (OrACORe) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Katz is director of OrACORe and professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, as well as professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. These comments were adapted from an editorial that accompanied the report (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:339-41). The National Institutes of Health provided grant support for this research.

Intensive study of the outcomes of total knee arthroscopy in patients younger than 60 years is merited, given the expansion of indications involving TKA, according to Elena Losina, Ph.D., and Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz.

"Since younger patients are likely to be more physically active, to have more strenuous physical demands, and to make treatment choices that support an active lifestyle, the longevity or ‘survival’ of knee implants in this group may be lower than in older patients."

"The greater risk of implant failure in younger patients, coupled with longer remaining life expectancy in this age group, will combine to produce even higher rates of revision TKA in this population of TKA recipients," they added.

Most of the excellent outcomes in TKA have been seen in patients in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, wrote Dr. Losina and Dr. Katz. Few studies have investigated outcomes of TKAs and UKAs in those under age 60 and in those with less severe conditions. "While TKA has been shown to dramatically improve functional status and reduce pain in persons with severe pain and functional limitation, would similar dramatic improvements be observed in those who decide to undergo surgery with less severe functional impairment?" they wrote.

Dr. Losina is codirector of the Orthopedic and Arthritis Center for Outcomes Research (OrACORe) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Katz is director of OrACORe and professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, as well as professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. These comments were adapted from an editorial that accompanied the report (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:339-41). The National Institutes of Health provided grant support for this research.

Intensive study of the outcomes of total knee arthroscopy in patients younger than 60 years is merited, given the expansion of indications involving TKA, according to Elena Losina, Ph.D., and Dr. Jeffrey N. Katz.

"Since younger patients are likely to be more physically active, to have more strenuous physical demands, and to make treatment choices that support an active lifestyle, the longevity or ‘survival’ of knee implants in this group may be lower than in older patients."

"The greater risk of implant failure in younger patients, coupled with longer remaining life expectancy in this age group, will combine to produce even higher rates of revision TKA in this population of TKA recipients," they added.

Most of the excellent outcomes in TKA have been seen in patients in their 60s, 70s, and 80s, wrote Dr. Losina and Dr. Katz. Few studies have investigated outcomes of TKAs and UKAs in those under age 60 and in those with less severe conditions. "While TKA has been shown to dramatically improve functional status and reduce pain in persons with severe pain and functional limitation, would similar dramatic improvements be observed in those who decide to undergo surgery with less severe functional impairment?" they wrote.

Dr. Losina is codirector of the Orthopedic and Arthritis Center for Outcomes Research (OrACORe) at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Katz is director of OrACORe and professor of medicine and orthopedic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, as well as professor of epidemiology and environmental health at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston. These comments were adapted from an editorial that accompanied the report (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:339-41). The National Institutes of Health provided grant support for this research.

The incidence of total knee arthroplasties increased from 0.5 operations per 100,000 inhabitants to 65 operations per 100,000 inhabitants aged 30-59 years during 1980-2006 in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis, according to a Finnish study.

Patients born shortly after World War II showed the most dramatic increases.

Incidences of unicondylar or partial knee arthroplasties (UKAs) were also found to grow from 0.2 operations per 100,000 inhabitants to 10 operations per 100,000 inhabitants over the same period in the same Finnish patient age group.

"This phenomenon has been especially strong during the 21st century. There is no single explanatory factor for this growth. Some of the increase in incidence can be explained by hospital volume," wrote Dr. Jarkko Leskinen, Consultant Orthopedic Surgeon, Peijas Hospital, Helsinki University Central Hospital, who was lead author of the study published in the January issue of Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:423-8).

"The demand for primary TKA [total knee arthroplasty] has been estimated to grow by 673 percent to 3.48 million procedures in the United States by the year 2030," reported Dr. Leskinen. Previous studies reported increases in the incidence of TKA in younger patients in Australia and the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. This study aimed to analyze the changes in age group as well as the sex-standardized incidence of UKAs and TKAs in Finland between the years 1980 and 2006.

Patient data were drawn from the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry, and population data were obtained from Statistics Finland. A total of 8,961 knee arthroplasties were performed for primary osteoarthritis in patients under age 60 during 1980-2006. In addition to evaluating the effects of age and gender on the incidences of knee arthroplasties, Dr. Leskinen and his colleagues evaluated the effects of hospital volume.

Overall, the incidence rate ratio (IRR) for the annual increase in general incidence of UKAs was lower than that of TKAs, with an IRR of 1.26 for UKAs (95% confidence interval, 1.24-1.28; P less than .001) and 6.92 for TKAs (95% CI, 6.50-7.36; P less than .001).

In particular, the study found that the TKA incidence rose sharply from 18 per 100,000 in 2001 to 65 per 100,000 in 2006. TKAs were performed more often in women than men, with a 1.6- to 2.4-fold higher incidence in women than men during the past 10 years. Since 2000, a greater number of UKAs also were performed in women than men. Most of the increased incidence in TKAs and UKAs was in women aged 50-59 years.

Regarding the incidence of TKAs by age group, patients aged 50-59 years showed the largest increase, from 1.5 TKAs per 100,000 in 1980 to 160 per 100,000 in 2006. Incidences of UKAs by age group showed a similar pattern to TKAs, with the most marked growth in patients aged 50-59 years, increasing from 0.5 to 24 operations per 100,000. Growth was most rapid after the year 2000.

"Possible explanations for this phenomenon include the high functional and quality of life demands of younger patients aged less than 60 years," the authors wrote. "Another reason could be that the baby boomers may opt for elective operations at an earlier stage with milder symptoms, than the situation that was faced by earlier generations."

Hospitals were divided into low-, intermediate-, and high-volume centers, according to the number of TKAs performed in all the hospitals in Finland in 2006. The incidence of TKAs grew more rapidly in low- and intermediate-volume hospitals, while the incidence of UKAs grew in low-volume hospitals. The IRR for TKAs was 1.23 in both comparisons of low- to high-volume centers (95% CI, 1.13-1.34; P less than .001), and intermediate- to high-volume centers (95%CI, 1.16-1.31; P less than .001).

The authors warned against the widespread use of TKAs in younger patients. "Long-term results in young patients may differ from those reported in older patients, and risk for revision may be higher," they concluded.

Dr. Leskinen and his colleagues reported having no financial disclosures.

The incidence of total knee arthroplasties increased from 0.5 operations per 100,000 inhabitants to 65 operations per 100,000 inhabitants aged 30-59 years during 1980-2006 in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis, according to a Finnish study.

Patients born shortly after World War II showed the most dramatic increases.

Incidences of unicondylar or partial knee arthroplasties (UKAs) were also found to grow from 0.2 operations per 100,000 inhabitants to 10 operations per 100,000 inhabitants over the same period in the same Finnish patient age group.

"This phenomenon has been especially strong during the 21st century. There is no single explanatory factor for this growth. Some of the increase in incidence can be explained by hospital volume," wrote Dr. Jarkko Leskinen, Consultant Orthopedic Surgeon, Peijas Hospital, Helsinki University Central Hospital, who was lead author of the study published in the January issue of Arthritis & Rheumatism (Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:423-8).

"The demand for primary TKA [total knee arthroplasty] has been estimated to grow by 673 percent to 3.48 million procedures in the United States by the year 2030," reported Dr. Leskinen. Previous studies reported increases in the incidence of TKA in younger patients in Australia and the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. This study aimed to analyze the changes in age group as well as the sex-standardized incidence of UKAs and TKAs in Finland between the years 1980 and 2006.

Patient data were drawn from the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry, and population data were obtained from Statistics Finland. A total of 8,961 knee arthroplasties were performed for primary osteoarthritis in patients under age 60 during 1980-2006. In addition to evaluating the effects of age and gender on the incidences of knee arthroplasties, Dr. Leskinen and his colleagues evaluated the effects of hospital volume.

Overall, the incidence rate ratio (IRR) for the annual increase in general incidence of UKAs was lower than that of TKAs, with an IRR of 1.26 for UKAs (95% confidence interval, 1.24-1.28; P less than .001) and 6.92 for TKAs (95% CI, 6.50-7.36; P less than .001).

In particular, the study found that the TKA incidence rose sharply from 18 per 100,000 in 2001 to 65 per 100,000 in 2006. TKAs were performed more often in women than men, with a 1.6- to 2.4-fold higher incidence in women than men during the past 10 years. Since 2000, a greater number of UKAs also were performed in women than men. Most of the increased incidence in TKAs and UKAs was in women aged 50-59 years.

Regarding the incidence of TKAs by age group, patients aged 50-59 years showed the largest increase, from 1.5 TKAs per 100,000 in 1980 to 160 per 100,000 in 2006. Incidences of UKAs by age group showed a similar pattern to TKAs, with the most marked growth in patients aged 50-59 years, increasing from 0.5 to 24 operations per 100,000. Growth was most rapid after the year 2000.

"Possible explanations for this phenomenon include the high functional and quality of life demands of younger patients aged less than 60 years," the authors wrote. "Another reason could be that the baby boomers may opt for elective operations at an earlier stage with milder symptoms, than the situation that was faced by earlier generations."

Hospitals were divided into low-, intermediate-, and high-volume centers, according to the number of TKAs performed in all the hospitals in Finland in 2006. The incidence of TKAs grew more rapidly in low- and intermediate-volume hospitals, while the incidence of UKAs grew in low-volume hospitals. The IRR for TKAs was 1.23 in both comparisons of low- to high-volume centers (95% CI, 1.13-1.34; P less than .001), and intermediate- to high-volume centers (95%CI, 1.16-1.31; P less than .001).

The authors warned against the widespread use of TKAs in younger patients. "Long-term results in young patients may differ from those reported in older patients, and risk for revision may be higher," they concluded.

Dr. Leskinen and his colleagues reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATISM

Major Finding: TKAs increased from 0.5 to 65 operations per 100,000 inhabitants aged 30-59 years during 1980-2006 in Finland.

Data Source: A population-based study investigating the incidence of TKA and UKA in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis. Data were drawn from a total of 8,961 knee arthroplasties.

Disclosures: Dr. Leskinen and his colleagues reported having no financial disclosures.

Herbs Are Not Viable Osteoarthritis Treatment

Patients with osteoarthritis who routinely turn to devil’s claw, Indian frankincense, ginger, and other herbal medicines for symptom relief may want to think twice about this practice.

According to a review of these products that appears in the January 2012 issue of Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, a publication of the London-based BMJ Group, there is little conclusive evidence to justify their widespread use by patients with the disease (Drug Ther. Bull. 2012:50:8-12). A press release about the review points out that few robust studies on the use of herbal medicines for osteoarthritis (OA) have been carried out. "And those that have frequently contain design flaws and limitations, such as variations in the chemical make-up of the same herb, all of which comprise the validity of the findings."

Herbal medicines that are commonly used to treat OA include vegetable extracts of avocado or soybean unsaponifiables (ASUs), cat’s claw, devil’s claw, Indian frankincense, ginger, rosehip, turmeric, and willow bark. According to the review, the best available clinical evidence suggests that ASUs, Indian frankincense, and rosehips may work, "but more robust data are needed." ASUs are available in Europe but not the United States.

"If we did a better job, then patients probably wouldn’t be reaching for herbal medicines."

In an interview, Dr. Roy Altman, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, characterized the DTB review as more opinion than an adequate review of the literature. "The reviews of each product were pretty limited; there are longer and more extensive reviews of this topic," said Dr. Altman. Of all the herbals that have been studied as possible agents for OA management, ASUs are supported by the most and best data. "Studies about [ASUs] have been published in several respected journals. The second-best data are with ginger. I don’t think the data with the frankincense and the rosehips are that good, but the rosehips are presently undergoing additional study."

Some herbal medicines may cause adverse reactions in patients taking other medicines and prescription drugs. For example, the chronic use of nettle can interfere with drugs that are used to treat diabetes, lower blood pressure, and depress the central nervous system, whereas willow bark can cause digestive symptoms and renal problems. The review described the use of herbal medicines for OA as "generally under-researched, and information on potentially significant herb-drug interactions is limited."

Although the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency has approved Traditional Herbal Registrations for several herbal medicinal products containing devil’s claw for rheumatic symptoms, "gthe trial results for this herb are equivocal,"h the review states. "gThere is little conclusive evidence of benefit from other herbs commonly used for symptoms of osteoarthritis, such as cat’s claw, ginger, nettle, turmeric, and willow bark. [Health care] professionals should routinely ask patients with osteoarthritis if they are taking any herbal products."h

Dr. Altman said that he does not currently advocate the use of herbal medicines for OA patients. "We tend to see a lot of patients who ask about frankincense and turmeric," he said. "The major concern we have in this field is not only the approval of these products by some clinical trial basis and the safety of these products, but the verification that the marketed product is consistent from one batch to another. For example, there are about 1,000 different subspecies of ginger. Which of these species are you using, and what time of the year are you harvesting the ginger? The purification process has to be standardized or you’re not going to have the same product from one batch to another. The same problem exists for all of the herbs."

He noted that the review "raises the point that we are not as good at treating OA pain and other problems as we should be. If we did a better job, then patients probably wouldn’t be reaching for herbal medicines."

The review did not include data on glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, as they are not of herbal origin. Dr. Altman has published research on ginger and has served as a paid consultant in the past with the French company Pharmascience, which manufactures ASUs.

Patients with osteoarthritis who routinely turn to devil’s claw, Indian frankincense, ginger, and other herbal medicines for symptom relief may want to think twice about this practice.

According to a review of these products that appears in the January 2012 issue of Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, a publication of the London-based BMJ Group, there is little conclusive evidence to justify their widespread use by patients with the disease (Drug Ther. Bull. 2012:50:8-12). A press release about the review points out that few robust studies on the use of herbal medicines for osteoarthritis (OA) have been carried out. "And those that have frequently contain design flaws and limitations, such as variations in the chemical make-up of the same herb, all of which comprise the validity of the findings."

Herbal medicines that are commonly used to treat OA include vegetable extracts of avocado or soybean unsaponifiables (ASUs), cat’s claw, devil’s claw, Indian frankincense, ginger, rosehip, turmeric, and willow bark. According to the review, the best available clinical evidence suggests that ASUs, Indian frankincense, and rosehips may work, "but more robust data are needed." ASUs are available in Europe but not the United States.

"If we did a better job, then patients probably wouldn’t be reaching for herbal medicines."

In an interview, Dr. Roy Altman, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, characterized the DTB review as more opinion than an adequate review of the literature. "The reviews of each product were pretty limited; there are longer and more extensive reviews of this topic," said Dr. Altman. Of all the herbals that have been studied as possible agents for OA management, ASUs are supported by the most and best data. "Studies about [ASUs] have been published in several respected journals. The second-best data are with ginger. I don’t think the data with the frankincense and the rosehips are that good, but the rosehips are presently undergoing additional study."

Some herbal medicines may cause adverse reactions in patients taking other medicines and prescription drugs. For example, the chronic use of nettle can interfere with drugs that are used to treat diabetes, lower blood pressure, and depress the central nervous system, whereas willow bark can cause digestive symptoms and renal problems. The review described the use of herbal medicines for OA as "generally under-researched, and information on potentially significant herb-drug interactions is limited."

Although the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency has approved Traditional Herbal Registrations for several herbal medicinal products containing devil’s claw for rheumatic symptoms, "gthe trial results for this herb are equivocal,"h the review states. "gThere is little conclusive evidence of benefit from other herbs commonly used for symptoms of osteoarthritis, such as cat’s claw, ginger, nettle, turmeric, and willow bark. [Health care] professionals should routinely ask patients with osteoarthritis if they are taking any herbal products."h

Dr. Altman said that he does not currently advocate the use of herbal medicines for OA patients. "We tend to see a lot of patients who ask about frankincense and turmeric," he said. "The major concern we have in this field is not only the approval of these products by some clinical trial basis and the safety of these products, but the verification that the marketed product is consistent from one batch to another. For example, there are about 1,000 different subspecies of ginger. Which of these species are you using, and what time of the year are you harvesting the ginger? The purification process has to be standardized or you’re not going to have the same product from one batch to another. The same problem exists for all of the herbs."

He noted that the review "raises the point that we are not as good at treating OA pain and other problems as we should be. If we did a better job, then patients probably wouldn’t be reaching for herbal medicines."

The review did not include data on glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, as they are not of herbal origin. Dr. Altman has published research on ginger and has served as a paid consultant in the past with the French company Pharmascience, which manufactures ASUs.

Patients with osteoarthritis who routinely turn to devil’s claw, Indian frankincense, ginger, and other herbal medicines for symptom relief may want to think twice about this practice.

According to a review of these products that appears in the January 2012 issue of Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, a publication of the London-based BMJ Group, there is little conclusive evidence to justify their widespread use by patients with the disease (Drug Ther. Bull. 2012:50:8-12). A press release about the review points out that few robust studies on the use of herbal medicines for osteoarthritis (OA) have been carried out. "And those that have frequently contain design flaws and limitations, such as variations in the chemical make-up of the same herb, all of which comprise the validity of the findings."

Herbal medicines that are commonly used to treat OA include vegetable extracts of avocado or soybean unsaponifiables (ASUs), cat’s claw, devil’s claw, Indian frankincense, ginger, rosehip, turmeric, and willow bark. According to the review, the best available clinical evidence suggests that ASUs, Indian frankincense, and rosehips may work, "but more robust data are needed." ASUs are available in Europe but not the United States.

"If we did a better job, then patients probably wouldn’t be reaching for herbal medicines."

In an interview, Dr. Roy Altman, professor of medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, characterized the DTB review as more opinion than an adequate review of the literature. "The reviews of each product were pretty limited; there are longer and more extensive reviews of this topic," said Dr. Altman. Of all the herbals that have been studied as possible agents for OA management, ASUs are supported by the most and best data. "Studies about [ASUs] have been published in several respected journals. The second-best data are with ginger. I don’t think the data with the frankincense and the rosehips are that good, but the rosehips are presently undergoing additional study."

Some herbal medicines may cause adverse reactions in patients taking other medicines and prescription drugs. For example, the chronic use of nettle can interfere with drugs that are used to treat diabetes, lower blood pressure, and depress the central nervous system, whereas willow bark can cause digestive symptoms and renal problems. The review described the use of herbal medicines for OA as "generally under-researched, and information on potentially significant herb-drug interactions is limited."

Although the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency has approved Traditional Herbal Registrations for several herbal medicinal products containing devil’s claw for rheumatic symptoms, "gthe trial results for this herb are equivocal,"h the review states. "gThere is little conclusive evidence of benefit from other herbs commonly used for symptoms of osteoarthritis, such as cat’s claw, ginger, nettle, turmeric, and willow bark. [Health care] professionals should routinely ask patients with osteoarthritis if they are taking any herbal products."h

Dr. Altman said that he does not currently advocate the use of herbal medicines for OA patients. "We tend to see a lot of patients who ask about frankincense and turmeric," he said. "The major concern we have in this field is not only the approval of these products by some clinical trial basis and the safety of these products, but the verification that the marketed product is consistent from one batch to another. For example, there are about 1,000 different subspecies of ginger. Which of these species are you using, and what time of the year are you harvesting the ginger? The purification process has to be standardized or you’re not going to have the same product from one batch to another. The same problem exists for all of the herbs."

He noted that the review "raises the point that we are not as good at treating OA pain and other problems as we should be. If we did a better job, then patients probably wouldn’t be reaching for herbal medicines."

The review did not include data on glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, as they are not of herbal origin. Dr. Altman has published research on ginger and has served as a paid consultant in the past with the French company Pharmascience, which manufactures ASUs.

Most Recreational Sports Do Not Elevate Osteoarthritis Risk

Information about the relative risks of knee OA as a result of sports participation is essential to help develop prevention strategies and shape public health messages, said Jeffrey Driban, Ph.D., who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Driban and his colleagues at Tufts Medical Center in Boston analyzed 16 studies that identified OA rates in elite and recreational athletes participating in a range of sports including running, soccer, and wrestling. In general, the prevalence of knee OA was 8.4% among the 3,192 athletes of any level, compared with 9.1% among the 3,485 nonathletes, Dr. Driban said.

However, the risk of knee OA is sport-specific, Dr. Driban said. Compared with nonathletes, soccer players at elite and nonelite levels were at increased risk of knee OA (relative risk, 4.4), as were elite athletes competing in distance running (3.2), weight lifting (6.4), and wrestling (3.7). Elite athletes were defined as those competing at the national, Olympic, or professional level; nonelite athletes were those competing at the recreational or scholastic level.

The results were limited by the lack of adequate data on women and injury histories for the study participants. However, the data are encouraging and suggest that knee OA risk generally is not elevated for most recreational athletes, said Dr. Driban.

"For individuals who are interested in pursuing the health benefits of physical activity, sports participation can be a healthy way of getting those benefits," Dr. Driban emphasized.

However, anyone who is especially concerned about reducing their risk for OA should opt for low-impact, noncontact sports, he said. Elite athletes in high-risk sports can take steps to reduce their risk, such as treating injuries promptly and maintaining a healthy weight and lifestyle when they retire from competition, he added.

Dr. Driban reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Information about the relative risks of knee OA as a result of sports participation is essential to help develop prevention strategies and shape public health messages, said Jeffrey Driban, Ph.D., who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Driban and his colleagues at Tufts Medical Center in Boston analyzed 16 studies that identified OA rates in elite and recreational athletes participating in a range of sports including running, soccer, and wrestling. In general, the prevalence of knee OA was 8.4% among the 3,192 athletes of any level, compared with 9.1% among the 3,485 nonathletes, Dr. Driban said.

However, the risk of knee OA is sport-specific, Dr. Driban said. Compared with nonathletes, soccer players at elite and nonelite levels were at increased risk of knee OA (relative risk, 4.4), as were elite athletes competing in distance running (3.2), weight lifting (6.4), and wrestling (3.7). Elite athletes were defined as those competing at the national, Olympic, or professional level; nonelite athletes were those competing at the recreational or scholastic level.

The results were limited by the lack of adequate data on women and injury histories for the study participants. However, the data are encouraging and suggest that knee OA risk generally is not elevated for most recreational athletes, said Dr. Driban.

"For individuals who are interested in pursuing the health benefits of physical activity, sports participation can be a healthy way of getting those benefits," Dr. Driban emphasized.

However, anyone who is especially concerned about reducing their risk for OA should opt for low-impact, noncontact sports, he said. Elite athletes in high-risk sports can take steps to reduce their risk, such as treating injuries promptly and maintaining a healthy weight and lifestyle when they retire from competition, he added.

Dr. Driban reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Information about the relative risks of knee OA as a result of sports participation is essential to help develop prevention strategies and shape public health messages, said Jeffrey Driban, Ph.D., who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Dr. Driban and his colleagues at Tufts Medical Center in Boston analyzed 16 studies that identified OA rates in elite and recreational athletes participating in a range of sports including running, soccer, and wrestling. In general, the prevalence of knee OA was 8.4% among the 3,192 athletes of any level, compared with 9.1% among the 3,485 nonathletes, Dr. Driban said.

However, the risk of knee OA is sport-specific, Dr. Driban said. Compared with nonathletes, soccer players at elite and nonelite levels were at increased risk of knee OA (relative risk, 4.4), as were elite athletes competing in distance running (3.2), weight lifting (6.4), and wrestling (3.7). Elite athletes were defined as those competing at the national, Olympic, or professional level; nonelite athletes were those competing at the recreational or scholastic level.

The results were limited by the lack of adequate data on women and injury histories for the study participants. However, the data are encouraging and suggest that knee OA risk generally is not elevated for most recreational athletes, said Dr. Driban.

"For individuals who are interested in pursuing the health benefits of physical activity, sports participation can be a healthy way of getting those benefits," Dr. Driban emphasized.

However, anyone who is especially concerned about reducing their risk for OA should opt for low-impact, noncontact sports, he said. Elite athletes in high-risk sports can take steps to reduce their risk, such as treating injuries promptly and maintaining a healthy weight and lifestyle when they retire from competition, he added.

Dr. Driban reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Major Finding: The overall prevalence of knee osteoarthritis was 8.4% among athletes, compared with 9.1% among nonathletes.

Data Source: A meta-analysis of 16 studies including more than 6,000 adults.

Disclosures: Dr. Driban reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Target Adults With Arthritis for Physical Activity Initiatives

In 2009, the prevalence of no physical activity was 53% higher in adults with arthritis than those without, based on the latest data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The findings were published online in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Dec. 8.

From 2002 to 2008, the percentage of all adults in the United States who reported no physical activity stagnated at 25%, regardless of their arthritis status. The growing subset of adults with arthritis who tend to be sedentary because of their barriers to activity may have contributed to that stagnation, according to the CDC researchers.

"Further reduction in the prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) among all adults might be hindered by population subgroups that have exceptionally high rates of no LTPA, such as adults with arthritis," the researchers noted.

The researchers reviewed data from 432,607 adults aged 18 years and older who responded to telephone surveys. The study population included respondents from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and all U.S. territories (MMWR 2011;60:1641-45).

Adults with arthritis accounted for at least 20% of all adults reporting no LTPA in each state, ranging from 21% in Minnesota to 43% in Tennessee.

Survey respondents were defined as "no LTPA" if they answered no to the question, "During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?"

Survey respondents were defined as having arthritis if they answered yes to the question, "Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?"

The findings are not surprising, given the disease-specific barriers to physical activity experienced by people with arthritis, the researchers wrote.

"However, these barriers can be addressed through targeted health communication messages; increased access to arthritis-appropriate, individually adapted behavior change programs; and relevant policy and environmental changes," they added.

The study results were limited by several factors, included the use of self-reports and the lack of including household, occupational, or transportation-related activities as LTPA.

The findings, however, support data from previous studies showing increased rates of physical inactivity in adults with arthritis, and they highlight the need to target these individuals with physical activity promotion initiatives that are arthritis specific, the researchers noted.

"Health care providers and public health physical activity practitioners should counsel arthritis patients regarding the benefits of physical activity and refer them to physical or occupational therapy if indicated or to locally available arthritis-appropriate physical activity programs," they said.

The study was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2009, the prevalence of no physical activity was 53% higher in adults with arthritis than those without, based on the latest data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The findings were published online in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Dec. 8.

From 2002 to 2008, the percentage of all adults in the United States who reported no physical activity stagnated at 25%, regardless of their arthritis status. The growing subset of adults with arthritis who tend to be sedentary because of their barriers to activity may have contributed to that stagnation, according to the CDC researchers.

"Further reduction in the prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) among all adults might be hindered by population subgroups that have exceptionally high rates of no LTPA, such as adults with arthritis," the researchers noted.

The researchers reviewed data from 432,607 adults aged 18 years and older who responded to telephone surveys. The study population included respondents from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and all U.S. territories (MMWR 2011;60:1641-45).

Adults with arthritis accounted for at least 20% of all adults reporting no LTPA in each state, ranging from 21% in Minnesota to 43% in Tennessee.

Survey respondents were defined as "no LTPA" if they answered no to the question, "During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?"

Survey respondents were defined as having arthritis if they answered yes to the question, "Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?"

The findings are not surprising, given the disease-specific barriers to physical activity experienced by people with arthritis, the researchers wrote.

"However, these barriers can be addressed through targeted health communication messages; increased access to arthritis-appropriate, individually adapted behavior change programs; and relevant policy and environmental changes," they added.

The study results were limited by several factors, included the use of self-reports and the lack of including household, occupational, or transportation-related activities as LTPA.

The findings, however, support data from previous studies showing increased rates of physical inactivity in adults with arthritis, and they highlight the need to target these individuals with physical activity promotion initiatives that are arthritis specific, the researchers noted.

"Health care providers and public health physical activity practitioners should counsel arthritis patients regarding the benefits of physical activity and refer them to physical or occupational therapy if indicated or to locally available arthritis-appropriate physical activity programs," they said.

The study was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2009, the prevalence of no physical activity was 53% higher in adults with arthritis than those without, based on the latest data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. The findings were published online in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report on Dec. 8.

From 2002 to 2008, the percentage of all adults in the United States who reported no physical activity stagnated at 25%, regardless of their arthritis status. The growing subset of adults with arthritis who tend to be sedentary because of their barriers to activity may have contributed to that stagnation, according to the CDC researchers.

"Further reduction in the prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) among all adults might be hindered by population subgroups that have exceptionally high rates of no LTPA, such as adults with arthritis," the researchers noted.

The researchers reviewed data from 432,607 adults aged 18 years and older who responded to telephone surveys. The study population included respondents from all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and all U.S. territories (MMWR 2011;60:1641-45).

Adults with arthritis accounted for at least 20% of all adults reporting no LTPA in each state, ranging from 21% in Minnesota to 43% in Tennessee.

Survey respondents were defined as "no LTPA" if they answered no to the question, "During the past month, other than your regular job, did you participate in any physical activities or exercises such as running, calisthenics, golf, gardening, or walking for exercise?"

Survey respondents were defined as having arthritis if they answered yes to the question, "Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have some form of arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, lupus, or fibromyalgia?"

The findings are not surprising, given the disease-specific barriers to physical activity experienced by people with arthritis, the researchers wrote.

"However, these barriers can be addressed through targeted health communication messages; increased access to arthritis-appropriate, individually adapted behavior change programs; and relevant policy and environmental changes," they added.

The study results were limited by several factors, included the use of self-reports and the lack of including household, occupational, or transportation-related activities as LTPA.

The findings, however, support data from previous studies showing increased rates of physical inactivity in adults with arthritis, and they highlight the need to target these individuals with physical activity promotion initiatives that are arthritis specific, the researchers noted.

"Health care providers and public health physical activity practitioners should counsel arthritis patients regarding the benefits of physical activity and refer them to physical or occupational therapy if indicated or to locally available arthritis-appropriate physical activity programs," they said.

The study was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

FROM MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Major Finding: U.S. adults with arthritis have a 53% greater prevalence of no physical activity, compared with adults without arthritis.

Data Source: Data from 432,607 adults aged 18 years and older who responded to telephone surveys as part of the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Disclosures: The study was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Osteoarthritis May Drive Up Risk of Falling, Fracture

CHICAGO – Despite their bigger bones, postmenopausal women with osteoarthritis appear to be at a greater risk of falls and subsequent fractures, compared to their counterparts without the joint disease, according to an analysis of data from a longitudinal study of more than 50,000 women.

Among the 51,386 women in GLOW (Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women), 40% had osteoarthritis (OA). Women with OA experienced almost 30% more falls and had a 20% greater risk of fracture than those without OA, lead author Dr. Daniel Prieto-Alhambra said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

"We know that patients with osteoarthritis have bigger bones, and some have actually suggested that these bones are more resistant." However, recent papers have suggested that patients with osteoarthritis experience more falls than the general population, said Dr. Prieto-Alhambra, who is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Hospital del Mar and Municipal Institute of Medical Research in Barcelona.

Coauthor Dr. Nigel Arden noted that "we’ve seen this in other cohorts before. What was new here was that the falls would actually explain the increased risk of fracture, whereas in other cohorts, it hasn’t explained it."

Part of the disconnect between bigger bones and fractures in OA is that bone mineral density (BMD) measurements do not provide an accurate picture of BMD. "The bone density measurement is a two-dimensional measurement of a three-dimensional bone," said Dr. Arden in an interview. Individuals with OA have up to an 8% greater BMD when viewed two dimensionally. However, "when you look at volumetric density, as we’ve done in another cohort, their density is the same [as those without OA] – they just have bigger bones."

All of this can lead to a potential overestimate of BMD. "In osteoporosis, we use bone density as a predictor of fracture. People with osteoarthritis have an increased bone density and therefore should have a low risk of fracture but they have an increased risk of fracture. Therefore, we were concerned that people were being falsely reassured by their increased bone density measurements," Dr. Arden added.

In addition, "when they get osteoarthritis, they have increased rates of bone loss, which again is an independent risk factor for fracture," said Dr. Arden, who is a professor of rheumatology at the University of Oxford (England).

The study included 60,393 women aged 55 years or older. For 3 years, participants from several countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Spain, and others, were surveyed annually. Women who were at least 55 years old and who visited a practice within the previous 2 years were eligible. The women were mailed a self-administered questionnaire at baseline; follow-up questionnaires were sent at 12-month intervals for 3 years. Participants were asked if a doctor or other health care provider had told them that they had osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease. Information on incident falls and fractures and potential confounders were self-reported. For this analysis, women with missing baseline OA or fracture information, as well as those with celiac disease or rheumatoid arthritis, were excluded.

The unadjusted hazard ratio for fracture among OA patients was 1.40 and this remained significant after multivariable adjustment (HR, 1.21). Falls were also more likely in women with OA (adjusted HR, 1.27). The association between OA and fracture remained significant even after adjusting for baseline falls (HR, 1.16).

"If falls explain the increased risk of fracture, we need to work out why these people are falling and have public health interventions to reduce those risks of falls – through physiotherapy, nutrition, and help around the home," said Dr. Arden. "We also need to worry that when we do an osteoporosis estimation that we [consider] osteoarthritis as an extra risk factor."

"We need to pay more attention to pain relief, exercise, and support around the home ... and when we assess their osteoporosis risk we need to think that their bone density may be falsely reassuring," Dr. Arden said.

Dr. Prieto-Alhambra and Dr. Arden reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Despite their bigger bones, postmenopausal women with osteoarthritis appear to be at a greater risk of falls and subsequent fractures, compared to their counterparts without the joint disease, according to an analysis of data from a longitudinal study of more than 50,000 women.

Among the 51,386 women in GLOW (Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women), 40% had osteoarthritis (OA). Women with OA experienced almost 30% more falls and had a 20% greater risk of fracture than those without OA, lead author Dr. Daniel Prieto-Alhambra said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

"We know that patients with osteoarthritis have bigger bones, and some have actually suggested that these bones are more resistant." However, recent papers have suggested that patients with osteoarthritis experience more falls than the general population, said Dr. Prieto-Alhambra, who is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Hospital del Mar and Municipal Institute of Medical Research in Barcelona.

Coauthor Dr. Nigel Arden noted that "we’ve seen this in other cohorts before. What was new here was that the falls would actually explain the increased risk of fracture, whereas in other cohorts, it hasn’t explained it."

Part of the disconnect between bigger bones and fractures in OA is that bone mineral density (BMD) measurements do not provide an accurate picture of BMD. "The bone density measurement is a two-dimensional measurement of a three-dimensional bone," said Dr. Arden in an interview. Individuals with OA have up to an 8% greater BMD when viewed two dimensionally. However, "when you look at volumetric density, as we’ve done in another cohort, their density is the same [as those without OA] – they just have bigger bones."

All of this can lead to a potential overestimate of BMD. "In osteoporosis, we use bone density as a predictor of fracture. People with osteoarthritis have an increased bone density and therefore should have a low risk of fracture but they have an increased risk of fracture. Therefore, we were concerned that people were being falsely reassured by their increased bone density measurements," Dr. Arden added.

In addition, "when they get osteoarthritis, they have increased rates of bone loss, which again is an independent risk factor for fracture," said Dr. Arden, who is a professor of rheumatology at the University of Oxford (England).

The study included 60,393 women aged 55 years or older. For 3 years, participants from several countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Spain, and others, were surveyed annually. Women who were at least 55 years old and who visited a practice within the previous 2 years were eligible. The women were mailed a self-administered questionnaire at baseline; follow-up questionnaires were sent at 12-month intervals for 3 years. Participants were asked if a doctor or other health care provider had told them that they had osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease. Information on incident falls and fractures and potential confounders were self-reported. For this analysis, women with missing baseline OA or fracture information, as well as those with celiac disease or rheumatoid arthritis, were excluded.

The unadjusted hazard ratio for fracture among OA patients was 1.40 and this remained significant after multivariable adjustment (HR, 1.21). Falls were also more likely in women with OA (adjusted HR, 1.27). The association between OA and fracture remained significant even after adjusting for baseline falls (HR, 1.16).

"If falls explain the increased risk of fracture, we need to work out why these people are falling and have public health interventions to reduce those risks of falls – through physiotherapy, nutrition, and help around the home," said Dr. Arden. "We also need to worry that when we do an osteoporosis estimation that we [consider] osteoarthritis as an extra risk factor."

"We need to pay more attention to pain relief, exercise, and support around the home ... and when we assess their osteoporosis risk we need to think that their bone density may be falsely reassuring," Dr. Arden said.

Dr. Prieto-Alhambra and Dr. Arden reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

CHICAGO – Despite their bigger bones, postmenopausal women with osteoarthritis appear to be at a greater risk of falls and subsequent fractures, compared to their counterparts without the joint disease, according to an analysis of data from a longitudinal study of more than 50,000 women.

Among the 51,386 women in GLOW (Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women), 40% had osteoarthritis (OA). Women with OA experienced almost 30% more falls and had a 20% greater risk of fracture than those without OA, lead author Dr. Daniel Prieto-Alhambra said at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

"We know that patients with osteoarthritis have bigger bones, and some have actually suggested that these bones are more resistant." However, recent papers have suggested that patients with osteoarthritis experience more falls than the general population, said Dr. Prieto-Alhambra, who is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Hospital del Mar and Municipal Institute of Medical Research in Barcelona.

Coauthor Dr. Nigel Arden noted that "we’ve seen this in other cohorts before. What was new here was that the falls would actually explain the increased risk of fracture, whereas in other cohorts, it hasn’t explained it."

Part of the disconnect between bigger bones and fractures in OA is that bone mineral density (BMD) measurements do not provide an accurate picture of BMD. "The bone density measurement is a two-dimensional measurement of a three-dimensional bone," said Dr. Arden in an interview. Individuals with OA have up to an 8% greater BMD when viewed two dimensionally. However, "when you look at volumetric density, as we’ve done in another cohort, their density is the same [as those without OA] – they just have bigger bones."

All of this can lead to a potential overestimate of BMD. "In osteoporosis, we use bone density as a predictor of fracture. People with osteoarthritis have an increased bone density and therefore should have a low risk of fracture but they have an increased risk of fracture. Therefore, we were concerned that people were being falsely reassured by their increased bone density measurements," Dr. Arden added.

In addition, "when they get osteoarthritis, they have increased rates of bone loss, which again is an independent risk factor for fracture," said Dr. Arden, who is a professor of rheumatology at the University of Oxford (England).

The study included 60,393 women aged 55 years or older. For 3 years, participants from several countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Spain, and others, were surveyed annually. Women who were at least 55 years old and who visited a practice within the previous 2 years were eligible. The women were mailed a self-administered questionnaire at baseline; follow-up questionnaires were sent at 12-month intervals for 3 years. Participants were asked if a doctor or other health care provider had told them that they had osteoarthritis or degenerative joint disease. Information on incident falls and fractures and potential confounders were self-reported. For this analysis, women with missing baseline OA or fracture information, as well as those with celiac disease or rheumatoid arthritis, were excluded.

The unadjusted hazard ratio for fracture among OA patients was 1.40 and this remained significant after multivariable adjustment (HR, 1.21). Falls were also more likely in women with OA (adjusted HR, 1.27). The association between OA and fracture remained significant even after adjusting for baseline falls (HR, 1.16).

"If falls explain the increased risk of fracture, we need to work out why these people are falling and have public health interventions to reduce those risks of falls – through physiotherapy, nutrition, and help around the home," said Dr. Arden. "We also need to worry that when we do an osteoporosis estimation that we [consider] osteoarthritis as an extra risk factor."

"We need to pay more attention to pain relief, exercise, and support around the home ... and when we assess their osteoporosis risk we need to think that their bone density may be falsely reassuring," Dr. Arden said.

Dr. Prieto-Alhambra and Dr. Arden reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Major Finding: Women with osteoarthritis experienced almost 30% more falls and had a 20% greater risk of fracture than those without OA.

Data Source: An analysis of 51,386 women participating in GLOW (Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women).

Disclosures: Dr. Prieto-Alhambra and Dr. Arden reported that they have no relevant disclosures.

Severity of ACL Rupture Predicts OA Risk

SAN DIEGO – The more severe an anterior cruciate ligament injury, the more likely patients are to develop arthritis in the injured knee; structural changes might even be seen within 4 years of the trauma, a small study has shown.

In results presented at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis, patients who had had anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction were four times more likely to have abnormal joint space narrowing by then if they also had a defect that extended more than halfway through their femoral cartilage (International Cartilage Repair Society grade III injury), a menisectomy, or both (odds ratio 4.11; 95% confidence interval 1.01-39.55, P = .05).

"These people were highly functioning; they were all athletic people. They had no symptoms of osteoarthritis," said lead investigator Timothy Tourville of the University of Vermont Center for Clinical and Translational Science in Burlington.

"Historically, most studies haven’t been able to demonstrate differences in [less than] 10 or 15 years. I think being able to pick them up at 4 years and identifying those who are at high risk for structural change is very important," rheumatologist David Hunter said in an interview.

"If, at the time of the injury, there is more substantive damage to either [the patient’s] cartilage or their meniscus, you are going to be more cautious about encouraging them to return to high physical activity and potentially redamaging their" knee, said Dr. Hunter, professor of medicine at the University of Sydney (Australia).

The 38 ACL patients in the study, about half women, were under 51 years of age and not obese. Their ACLs were reconstructed within a half-year of their injury, and none had gotten intra-articular injections. Other than their injury, they were in good health with no other joint problems. Baseline radiographs were compared with films at 3-4 years.

More than 60% (8/13) of those with grade III cartilage injuries had abnormal joint space narrowing at that point, compared with 28% (7/25) of those with no more than grade II injuries – defects extending less than halfway through their femoral cartilage – and intact menisci in both compartments.

"Abnormal" meant that the joint space difference between patients’ injured and uninjured knees fell outside the 95% confidence interval of bilateral differences measured in 32 matched controls.

The conference was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Mr. Tourville and Dr. Hunter said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases supported the work.

SAN DIEGO – The more severe an anterior cruciate ligament injury, the more likely patients are to develop arthritis in the injured knee; structural changes might even be seen within 4 years of the trauma, a small study has shown.

In results presented at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis, patients who had had anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction were four times more likely to have abnormal joint space narrowing by then if they also had a defect that extended more than halfway through their femoral cartilage (International Cartilage Repair Society grade III injury), a menisectomy, or both (odds ratio 4.11; 95% confidence interval 1.01-39.55, P = .05).

"These people were highly functioning; they were all athletic people. They had no symptoms of osteoarthritis," said lead investigator Timothy Tourville of the University of Vermont Center for Clinical and Translational Science in Burlington.

"Historically, most studies haven’t been able to demonstrate differences in [less than] 10 or 15 years. I think being able to pick them up at 4 years and identifying those who are at high risk for structural change is very important," rheumatologist David Hunter said in an interview.

"If, at the time of the injury, there is more substantive damage to either [the patient’s] cartilage or their meniscus, you are going to be more cautious about encouraging them to return to high physical activity and potentially redamaging their" knee, said Dr. Hunter, professor of medicine at the University of Sydney (Australia).

The 38 ACL patients in the study, about half women, were under 51 years of age and not obese. Their ACLs were reconstructed within a half-year of their injury, and none had gotten intra-articular injections. Other than their injury, they were in good health with no other joint problems. Baseline radiographs were compared with films at 3-4 years.

More than 60% (8/13) of those with grade III cartilage injuries had abnormal joint space narrowing at that point, compared with 28% (7/25) of those with no more than grade II injuries – defects extending less than halfway through their femoral cartilage – and intact menisci in both compartments.

"Abnormal" meant that the joint space difference between patients’ injured and uninjured knees fell outside the 95% confidence interval of bilateral differences measured in 32 matched controls.

The conference was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. Mr. Tourville and Dr. Hunter said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases supported the work.

SAN DIEGO – The more severe an anterior cruciate ligament injury, the more likely patients are to develop arthritis in the injured knee; structural changes might even be seen within 4 years of the trauma, a small study has shown.

In results presented at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis, patients who had had anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction were four times more likely to have abnormal joint space narrowing by then if they also had a defect that extended more than halfway through their femoral cartilage (International Cartilage Repair Society grade III injury), a menisectomy, or both (odds ratio 4.11; 95% confidence interval 1.01-39.55, P = .05).

"These people were highly functioning; they were all athletic people. They had no symptoms of osteoarthritis," said lead investigator Timothy Tourville of the University of Vermont Center for Clinical and Translational Science in Burlington.

"Historically, most studies haven’t been able to demonstrate differences in [less than] 10 or 15 years. I think being able to pick them up at 4 years and identifying those who are at high risk for structural change is very important," rheumatologist David Hunter said in an interview.