User login

Spinal cord stimulator restores Parkinson patient’s gait

The neuroprosthesis involves targeted epidural electrical stimulation of areas of the lumbosacral spinal cord that produce walking.

This new therapeutic tool offers hope to patients with PD and, combined with existing approaches, may alleviate a motor sign in PD for which there is currently “no real solution,” study investigator Eduardo Martin Moraud, PhD, who leads PD research at the Defitech Center for Interventional Neurotherapies (NeuroRestore), Lausanne, Switzerland, said in an interview.

“This is exciting for the many patients that develop gait deficits and experience frequent falls, who can only rely on physical therapy to try and minimize the consequences,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Medicine.

Personalized stimulation

About 90% of people with advanced PD experience gait and balance problems or freezing-of-gait episodes. These locomotor deficits typically don’t respond well to dopamine replacement therapy or deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus, possibly because the neural origins of these motor problems involve brain circuits not related to dopamine, said Dr. Moraud.

Continuous electrical stimulation over the cervical or thoracic segments of the spinal cord reduces locomotor deficits in some people with PD, but the broader application of this strategy has led to variable and unsatisfying outcomes.

The new approach focuses on correcting abnormal activation of circuits in the lumbar spinal cord, a region that hosts all the neurons that control activation of the leg muscles used for walking.

The stimulating device is placed on the lumbar region of the spinal cord, which sends messages to leg muscles. It is wired to a small impulse generator implanted under the skin of the abdomen. Sensors placed in shoes align the stimulation to the patient’s movement.

The system can detect the beginning of a movement, immediately activate the appropriate electrode, and so facilitate the necessary movement, be that leg flexion, extension, or propulsion, said Dr. Moraud. “This allows for increased walking symmetry, reinforced balance, and increased length of steps.”

The concept of this neuroprosthesis is similar to that used to allow patients with a spinal cord injury (SCI) to walk. But unlike patients with SCI, those with PD can move their legs, indicating that there is a descending command from the brain that needs to interact with the stimulation of the spinal cord, and patients with PD can feel the stimulation.

“Both these elements imply that amplitudes of stimulation need to be much lower in PD than SCI, and that stimulation needs to be fully personalized in PD to synergistically interact with the descending commands from the brain.”

After fine-tuning this new neuroprosthesis in animal models, researchers implanted the device in a 62-year-old man with a 30-year history of PD who presented with severe gait impairments, including marked gait asymmetry, reduced stride length, and balance problems.

Gait restored to near normal

The patient had frequent freezing-of-gait episodes when turning and passing through narrow paths, which led to multiple falls a day. This was despite being treated with DBS and dopaminergic replacement therapies.

But after getting used to the neuroprosthesis, the patient now walks with a gait akin to that of people without PD.

“Our experience in the preclinical animal models and this first patient is that gait can be restored to an almost healthy level, but this, of course, may vary across patients, depending on the severity of their disease progression, and their other motor deficits,” said Dr. Moraud.

When the neuroprosthesis is turned on, freezing of gait nearly vanishes, both with and without DBS.

In addition, the neuroprosthesis augmented the impact of the patient’s rehabilitation program, which involved a variety of regular exercises, including walking on basic and complex terrains, navigating outdoors in community settings, balance training, and basic physical therapy.

Frequent use of the neuroprosthesis during gait rehabilitation also translated into “highly improved” quality of life as reported by the patient (and his wife), said Dr. Moraud.

The patient has now been using the neuroprosthesis about 8 hours a day for nearly 2 years, only switching it off when sitting for long periods of time or while sleeping.

“He regained the capacity to walk in complex or crowded environments such as shops, airports, or his own home, without falling,” said Dr. Moraud. “He went from falling five to six times per day to one or two [falls] every couple of weeks. He’s also much more confident. He can walk for many miles, run, and go on holidays, without the constant fear of falling and having related injuries.”

Dr. Moraud stressed that the device does not replace DBS, which is a “key therapy” that addresses other deficits in PD, such as rigidity or slowness of movement. “What we propose here is a fully complementary approach for the gait problems that are not well addressed by DBS.”

One of the next steps will be to evaluate the efficacy of this approach across a wider spectrum of patient profiles to fully define the best responders, said Dr. Moraud.

A ‘tour de force’

In a comment, Michael S. Okun, MD, director of the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, and medical director of the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the researchers used “a smarter device” than past approaches that failed to adequately address progressive walking challenges of patients with PD.

Although it’s “tempting to get excited” about the findings, it’s important to consider that the study included only one human subject and did not target circuits for both walking and balance, said Dr. Okun. “It’s possible that even if future studies revealed a benefit for walking, the device may or may not address falling.”

In an accompanying editorial, Aviv Mizrahi-Kliger, MD, PhD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, and Karunesh Ganguly, MD, PhD, Neurology and Rehabilitation Service, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, called the study an “impressive tour de force,” with data from the nonhuman primate model and the individual with PD “jointly” indicating that epidural electrical stimulation (EES) “is a very promising treatment for several aspects of gait, posture and balance impairments in PD.”

But although the effect in the single patient “is quite impressive,” the “next crucial step” is to test this approach in a larger cohort of patients, they said.

They noted the nonhuman model does not exhibit freezing of gait, “which precluded the ability to corroborate or further study the role of EES in alleviating this symptom of PD in an animal model.”

In addition, stimulation parameters in the patient with PD “had to rely on estimated normal activity patterns, owing to the inability to measure pre-disease patterns at the individual level,” they wrote.

The study received funding from the Defitech Foundation, ONWARD Medical, CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Parkinson Schweiz Foundation, European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (NeuWalk), European Research Council, Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, Bertarelli Foundation, and Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Moraud and other study authors hold various patents or applications in relation to the present work. Dr. Mizrahi-Kliger has no relevant conflicts of interest; Dr. Ganguly has a patent for modulation of sensory inputs to improve motor recovery from stroke and has been a consultant to Cala Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuroprosthesis involves targeted epidural electrical stimulation of areas of the lumbosacral spinal cord that produce walking.

This new therapeutic tool offers hope to patients with PD and, combined with existing approaches, may alleviate a motor sign in PD for which there is currently “no real solution,” study investigator Eduardo Martin Moraud, PhD, who leads PD research at the Defitech Center for Interventional Neurotherapies (NeuroRestore), Lausanne, Switzerland, said in an interview.

“This is exciting for the many patients that develop gait deficits and experience frequent falls, who can only rely on physical therapy to try and minimize the consequences,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Medicine.

Personalized stimulation

About 90% of people with advanced PD experience gait and balance problems or freezing-of-gait episodes. These locomotor deficits typically don’t respond well to dopamine replacement therapy or deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus, possibly because the neural origins of these motor problems involve brain circuits not related to dopamine, said Dr. Moraud.

Continuous electrical stimulation over the cervical or thoracic segments of the spinal cord reduces locomotor deficits in some people with PD, but the broader application of this strategy has led to variable and unsatisfying outcomes.

The new approach focuses on correcting abnormal activation of circuits in the lumbar spinal cord, a region that hosts all the neurons that control activation of the leg muscles used for walking.

The stimulating device is placed on the lumbar region of the spinal cord, which sends messages to leg muscles. It is wired to a small impulse generator implanted under the skin of the abdomen. Sensors placed in shoes align the stimulation to the patient’s movement.

The system can detect the beginning of a movement, immediately activate the appropriate electrode, and so facilitate the necessary movement, be that leg flexion, extension, or propulsion, said Dr. Moraud. “This allows for increased walking symmetry, reinforced balance, and increased length of steps.”

The concept of this neuroprosthesis is similar to that used to allow patients with a spinal cord injury (SCI) to walk. But unlike patients with SCI, those with PD can move their legs, indicating that there is a descending command from the brain that needs to interact with the stimulation of the spinal cord, and patients with PD can feel the stimulation.

“Both these elements imply that amplitudes of stimulation need to be much lower in PD than SCI, and that stimulation needs to be fully personalized in PD to synergistically interact with the descending commands from the brain.”

After fine-tuning this new neuroprosthesis in animal models, researchers implanted the device in a 62-year-old man with a 30-year history of PD who presented with severe gait impairments, including marked gait asymmetry, reduced stride length, and balance problems.

Gait restored to near normal

The patient had frequent freezing-of-gait episodes when turning and passing through narrow paths, which led to multiple falls a day. This was despite being treated with DBS and dopaminergic replacement therapies.

But after getting used to the neuroprosthesis, the patient now walks with a gait akin to that of people without PD.

“Our experience in the preclinical animal models and this first patient is that gait can be restored to an almost healthy level, but this, of course, may vary across patients, depending on the severity of their disease progression, and their other motor deficits,” said Dr. Moraud.

When the neuroprosthesis is turned on, freezing of gait nearly vanishes, both with and without DBS.

In addition, the neuroprosthesis augmented the impact of the patient’s rehabilitation program, which involved a variety of regular exercises, including walking on basic and complex terrains, navigating outdoors in community settings, balance training, and basic physical therapy.

Frequent use of the neuroprosthesis during gait rehabilitation also translated into “highly improved” quality of life as reported by the patient (and his wife), said Dr. Moraud.

The patient has now been using the neuroprosthesis about 8 hours a day for nearly 2 years, only switching it off when sitting for long periods of time or while sleeping.

“He regained the capacity to walk in complex or crowded environments such as shops, airports, or his own home, without falling,” said Dr. Moraud. “He went from falling five to six times per day to one or two [falls] every couple of weeks. He’s also much more confident. He can walk for many miles, run, and go on holidays, without the constant fear of falling and having related injuries.”

Dr. Moraud stressed that the device does not replace DBS, which is a “key therapy” that addresses other deficits in PD, such as rigidity or slowness of movement. “What we propose here is a fully complementary approach for the gait problems that are not well addressed by DBS.”

One of the next steps will be to evaluate the efficacy of this approach across a wider spectrum of patient profiles to fully define the best responders, said Dr. Moraud.

A ‘tour de force’

In a comment, Michael S. Okun, MD, director of the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, and medical director of the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the researchers used “a smarter device” than past approaches that failed to adequately address progressive walking challenges of patients with PD.

Although it’s “tempting to get excited” about the findings, it’s important to consider that the study included only one human subject and did not target circuits for both walking and balance, said Dr. Okun. “It’s possible that even if future studies revealed a benefit for walking, the device may or may not address falling.”

In an accompanying editorial, Aviv Mizrahi-Kliger, MD, PhD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, and Karunesh Ganguly, MD, PhD, Neurology and Rehabilitation Service, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, called the study an “impressive tour de force,” with data from the nonhuman primate model and the individual with PD “jointly” indicating that epidural electrical stimulation (EES) “is a very promising treatment for several aspects of gait, posture and balance impairments in PD.”

But although the effect in the single patient “is quite impressive,” the “next crucial step” is to test this approach in a larger cohort of patients, they said.

They noted the nonhuman model does not exhibit freezing of gait, “which precluded the ability to corroborate or further study the role of EES in alleviating this symptom of PD in an animal model.”

In addition, stimulation parameters in the patient with PD “had to rely on estimated normal activity patterns, owing to the inability to measure pre-disease patterns at the individual level,” they wrote.

The study received funding from the Defitech Foundation, ONWARD Medical, CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Parkinson Schweiz Foundation, European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (NeuWalk), European Research Council, Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, Bertarelli Foundation, and Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Moraud and other study authors hold various patents or applications in relation to the present work. Dr. Mizrahi-Kliger has no relevant conflicts of interest; Dr. Ganguly has a patent for modulation of sensory inputs to improve motor recovery from stroke and has been a consultant to Cala Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The neuroprosthesis involves targeted epidural electrical stimulation of areas of the lumbosacral spinal cord that produce walking.

This new therapeutic tool offers hope to patients with PD and, combined with existing approaches, may alleviate a motor sign in PD for which there is currently “no real solution,” study investigator Eduardo Martin Moraud, PhD, who leads PD research at the Defitech Center for Interventional Neurotherapies (NeuroRestore), Lausanne, Switzerland, said in an interview.

“This is exciting for the many patients that develop gait deficits and experience frequent falls, who can only rely on physical therapy to try and minimize the consequences,” he added.

The findings were published online in Nature Medicine.

Personalized stimulation

About 90% of people with advanced PD experience gait and balance problems or freezing-of-gait episodes. These locomotor deficits typically don’t respond well to dopamine replacement therapy or deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the subthalamic nucleus, possibly because the neural origins of these motor problems involve brain circuits not related to dopamine, said Dr. Moraud.

Continuous electrical stimulation over the cervical or thoracic segments of the spinal cord reduces locomotor deficits in some people with PD, but the broader application of this strategy has led to variable and unsatisfying outcomes.

The new approach focuses on correcting abnormal activation of circuits in the lumbar spinal cord, a region that hosts all the neurons that control activation of the leg muscles used for walking.

The stimulating device is placed on the lumbar region of the spinal cord, which sends messages to leg muscles. It is wired to a small impulse generator implanted under the skin of the abdomen. Sensors placed in shoes align the stimulation to the patient’s movement.

The system can detect the beginning of a movement, immediately activate the appropriate electrode, and so facilitate the necessary movement, be that leg flexion, extension, or propulsion, said Dr. Moraud. “This allows for increased walking symmetry, reinforced balance, and increased length of steps.”

The concept of this neuroprosthesis is similar to that used to allow patients with a spinal cord injury (SCI) to walk. But unlike patients with SCI, those with PD can move their legs, indicating that there is a descending command from the brain that needs to interact with the stimulation of the spinal cord, and patients with PD can feel the stimulation.

“Both these elements imply that amplitudes of stimulation need to be much lower in PD than SCI, and that stimulation needs to be fully personalized in PD to synergistically interact with the descending commands from the brain.”

After fine-tuning this new neuroprosthesis in animal models, researchers implanted the device in a 62-year-old man with a 30-year history of PD who presented with severe gait impairments, including marked gait asymmetry, reduced stride length, and balance problems.

Gait restored to near normal

The patient had frequent freezing-of-gait episodes when turning and passing through narrow paths, which led to multiple falls a day. This was despite being treated with DBS and dopaminergic replacement therapies.

But after getting used to the neuroprosthesis, the patient now walks with a gait akin to that of people without PD.

“Our experience in the preclinical animal models and this first patient is that gait can be restored to an almost healthy level, but this, of course, may vary across patients, depending on the severity of their disease progression, and their other motor deficits,” said Dr. Moraud.

When the neuroprosthesis is turned on, freezing of gait nearly vanishes, both with and without DBS.

In addition, the neuroprosthesis augmented the impact of the patient’s rehabilitation program, which involved a variety of regular exercises, including walking on basic and complex terrains, navigating outdoors in community settings, balance training, and basic physical therapy.

Frequent use of the neuroprosthesis during gait rehabilitation also translated into “highly improved” quality of life as reported by the patient (and his wife), said Dr. Moraud.

The patient has now been using the neuroprosthesis about 8 hours a day for nearly 2 years, only switching it off when sitting for long periods of time or while sleeping.

“He regained the capacity to walk in complex or crowded environments such as shops, airports, or his own home, without falling,” said Dr. Moraud. “He went from falling five to six times per day to one or two [falls] every couple of weeks. He’s also much more confident. He can walk for many miles, run, and go on holidays, without the constant fear of falling and having related injuries.”

Dr. Moraud stressed that the device does not replace DBS, which is a “key therapy” that addresses other deficits in PD, such as rigidity or slowness of movement. “What we propose here is a fully complementary approach for the gait problems that are not well addressed by DBS.”

One of the next steps will be to evaluate the efficacy of this approach across a wider spectrum of patient profiles to fully define the best responders, said Dr. Moraud.

A ‘tour de force’

In a comment, Michael S. Okun, MD, director of the Norman Fixel Institute for Neurological Diseases, University of Florida, Gainesville, and medical director of the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the researchers used “a smarter device” than past approaches that failed to adequately address progressive walking challenges of patients with PD.

Although it’s “tempting to get excited” about the findings, it’s important to consider that the study included only one human subject and did not target circuits for both walking and balance, said Dr. Okun. “It’s possible that even if future studies revealed a benefit for walking, the device may or may not address falling.”

In an accompanying editorial, Aviv Mizrahi-Kliger, MD, PhD, department of neurology, University of California, San Francisco, and Karunesh Ganguly, MD, PhD, Neurology and Rehabilitation Service, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Health Care System, called the study an “impressive tour de force,” with data from the nonhuman primate model and the individual with PD “jointly” indicating that epidural electrical stimulation (EES) “is a very promising treatment for several aspects of gait, posture and balance impairments in PD.”

But although the effect in the single patient “is quite impressive,” the “next crucial step” is to test this approach in a larger cohort of patients, they said.

They noted the nonhuman model does not exhibit freezing of gait, “which precluded the ability to corroborate or further study the role of EES in alleviating this symptom of PD in an animal model.”

In addition, stimulation parameters in the patient with PD “had to rely on estimated normal activity patterns, owing to the inability to measure pre-disease patterns at the individual level,” they wrote.

The study received funding from the Defitech Foundation, ONWARD Medical, CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences, National Natural Science Foundation of China, Parkinson Schweiz Foundation, European Community’s Seventh Framework Program (NeuWalk), European Research Council, Wyss Center for Bio and Neuroengineering, Bertarelli Foundation, and Swiss National Science Foundation. Dr. Moraud and other study authors hold various patents or applications in relation to the present work. Dr. Mizrahi-Kliger has no relevant conflicts of interest; Dr. Ganguly has a patent for modulation of sensory inputs to improve motor recovery from stroke and has been a consultant to Cala Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NATURE MEDICINE

Artificial intelligence presents opportunities, challenges in neurologic practice

PHOENIX – and it presents opportunities for increased production and automation of some tasks. However, it is prone to error and ‘hallucinations’ despite an authoritative tone, so its conclusions must be verified.

Those were some of the messages from a talk by John Morren, MD, an associate professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, who spoke about AI at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Association for Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM).

He encouraged attendees to get involved in the conversation of AI, because it is here to stay and will have a big impact on health care. “If we’re not around the table making decisions, decisions will be made for us in our absence and won’t be in our favor,” said Dr. Morren.

He started out his talk by asking if anyone in the room had used AI. After about half raised their hands, he countered that nearly everyone likely had. Voice assistants like SIRI and Alexa, social media with curated feeds, online shopping tools that provide product suggestions, and content recommendations from streaming services like Netflix all rely on AI technology.

Within medicine, AI is already playing a role in various fields, including medical imaging, disease diagnosis, drug discovery and development, predictive analytics, personalized medicine, telemedicine, and health care management.

It also has potential to be used on the job. For example, ChatGPT can generate and refine conversations towards a specific length, format, style, and level of detail. Alternatives include Bing AI from Microsoft, Bard AI from Google, Writesonic, Copy.ai, SpinBot, HIX.AI, and Chatsonic.

Specific to medicine, Consensus is a search engine that uses AI to search for, summarize, and synthesize studies from peer-reviewed literature.

Trust, but verify

Dr. Morren presented some specific use cases, including patient education and responses to patient inquiries, as well as generating letters to insurance companies appealing denial of coverage claims. He also showed an example where he asked Bing AI to explain to a patient, at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level, the red-flag symptoms of myasthenic crisis.

AI can generate summaries of clinical evidence of previous studies. Asked by this reporter how to trust the accuracies of the summaries if the user hasn’t thoroughly read the papers, he acknowledged the imperfection of AI. “I would say that if you’re going to make a decision that you would not have made normally based on the summary that it’s giving, if you can find the fact that you’re anchoring the decision on, go into the article yourself and make sure that it’s well vetted. The AI is just good to tap you on your shoulder and say, ‘hey, just consider this.’ That’s all it is. You should always trust, but verify. If the AI is forcing you to say something new that you would not say, maybe don’t do it – or at least research it to know that it’s the truth and then you elevate yourself and get yourself to the next level.”

Limitations

The need to verify can create its own burden, according to one attendee. “I often find I end up spending more time verifying [what ChatGPT has provided]. This seems to take more time than a traditional way of going to PubMed or UpToDate or any of the other human generated consensus way,” he said.

Dr. Morren replied that he wouldn’t recommend using ChatGPT to query medical literature. Instead he recommended Consensus, which only searches the peer-reviewed medical literature.

Another key limitation is that most AI programs are date limited: For example, ChatGPT doesn’t include information after September 2021, though this may change with paid subscriptions. He also starkly warned the audience to never enter sensitive information, including patient identifiers.

There are legal and ethical considerations to AI. Dr. Morren warned against overreliance on AI, as this could undermine compassion and lead to erosion of trust, which makes it important to disclose any use of AI-generated content.

Another attendee raised concerns that AI may be generating research content, including slides for presentations, abstracts, titles, or article text. Dr. Morren said that some organizations, such as the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, have incorporated AI in their recommendations, stating that authors should disclose any contributions of AI to their publications. However, there is little that can be done to identify AI-generated content, leaving it up to the honor code.

Asked to make predictions about how AI will evolve in the clinic over the next 2-3 years, Dr. Morren suggested that it will likely be embedded in electronic medical records. He anticipated that it will save physicians time so that they can spend more time interacting directly with patients. He quoted Eric Topol, MD, professor of medicine at Scripps Research Translational Institute, La Jolla, Calif., as saying that AI could save 20% of a physician’s time, which could be spent with patients. Dr. Morren saw it differently. “I know where that 20% of time liberated is going to go. I’m going to see 20% more patients. I’m a realist,” he said, to audience laughter.

He also predicted that AI will be found in wearables and devices, allowing health care to expand into the patient’s home in real time. “A lot of what we’re wearing is going to be an extension of the doctor’s office,” he said.

For those hoping for more guidance, Dr. Morren noted that he is the chairman of the professional practice committee of AANEM, and the group will be putting out a position statement within the next couple of months. “It will be a little bit of a blueprint for the path going forward. There are specific things that need to be done. In research, for example, you have to ensure that datasets are diverse enough. To do that we need to have inter-institutional collaboration. We have to ensure patient privacy. Consent for this needs to be a little more explicit because this is a novel area. Those are things that need to be stipulated and ratified through a task force.”

Dr. Morren has no relevant financial disclosures.

PHOENIX – and it presents opportunities for increased production and automation of some tasks. However, it is prone to error and ‘hallucinations’ despite an authoritative tone, so its conclusions must be verified.

Those were some of the messages from a talk by John Morren, MD, an associate professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, who spoke about AI at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Association for Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM).

He encouraged attendees to get involved in the conversation of AI, because it is here to stay and will have a big impact on health care. “If we’re not around the table making decisions, decisions will be made for us in our absence and won’t be in our favor,” said Dr. Morren.

He started out his talk by asking if anyone in the room had used AI. After about half raised their hands, he countered that nearly everyone likely had. Voice assistants like SIRI and Alexa, social media with curated feeds, online shopping tools that provide product suggestions, and content recommendations from streaming services like Netflix all rely on AI technology.

Within medicine, AI is already playing a role in various fields, including medical imaging, disease diagnosis, drug discovery and development, predictive analytics, personalized medicine, telemedicine, and health care management.

It also has potential to be used on the job. For example, ChatGPT can generate and refine conversations towards a specific length, format, style, and level of detail. Alternatives include Bing AI from Microsoft, Bard AI from Google, Writesonic, Copy.ai, SpinBot, HIX.AI, and Chatsonic.

Specific to medicine, Consensus is a search engine that uses AI to search for, summarize, and synthesize studies from peer-reviewed literature.

Trust, but verify

Dr. Morren presented some specific use cases, including patient education and responses to patient inquiries, as well as generating letters to insurance companies appealing denial of coverage claims. He also showed an example where he asked Bing AI to explain to a patient, at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level, the red-flag symptoms of myasthenic crisis.

AI can generate summaries of clinical evidence of previous studies. Asked by this reporter how to trust the accuracies of the summaries if the user hasn’t thoroughly read the papers, he acknowledged the imperfection of AI. “I would say that if you’re going to make a decision that you would not have made normally based on the summary that it’s giving, if you can find the fact that you’re anchoring the decision on, go into the article yourself and make sure that it’s well vetted. The AI is just good to tap you on your shoulder and say, ‘hey, just consider this.’ That’s all it is. You should always trust, but verify. If the AI is forcing you to say something new that you would not say, maybe don’t do it – or at least research it to know that it’s the truth and then you elevate yourself and get yourself to the next level.”

Limitations

The need to verify can create its own burden, according to one attendee. “I often find I end up spending more time verifying [what ChatGPT has provided]. This seems to take more time than a traditional way of going to PubMed or UpToDate or any of the other human generated consensus way,” he said.

Dr. Morren replied that he wouldn’t recommend using ChatGPT to query medical literature. Instead he recommended Consensus, which only searches the peer-reviewed medical literature.

Another key limitation is that most AI programs are date limited: For example, ChatGPT doesn’t include information after September 2021, though this may change with paid subscriptions. He also starkly warned the audience to never enter sensitive information, including patient identifiers.

There are legal and ethical considerations to AI. Dr. Morren warned against overreliance on AI, as this could undermine compassion and lead to erosion of trust, which makes it important to disclose any use of AI-generated content.

Another attendee raised concerns that AI may be generating research content, including slides for presentations, abstracts, titles, or article text. Dr. Morren said that some organizations, such as the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, have incorporated AI in their recommendations, stating that authors should disclose any contributions of AI to their publications. However, there is little that can be done to identify AI-generated content, leaving it up to the honor code.

Asked to make predictions about how AI will evolve in the clinic over the next 2-3 years, Dr. Morren suggested that it will likely be embedded in electronic medical records. He anticipated that it will save physicians time so that they can spend more time interacting directly with patients. He quoted Eric Topol, MD, professor of medicine at Scripps Research Translational Institute, La Jolla, Calif., as saying that AI could save 20% of a physician’s time, which could be spent with patients. Dr. Morren saw it differently. “I know where that 20% of time liberated is going to go. I’m going to see 20% more patients. I’m a realist,” he said, to audience laughter.

He also predicted that AI will be found in wearables and devices, allowing health care to expand into the patient’s home in real time. “A lot of what we’re wearing is going to be an extension of the doctor’s office,” he said.

For those hoping for more guidance, Dr. Morren noted that he is the chairman of the professional practice committee of AANEM, and the group will be putting out a position statement within the next couple of months. “It will be a little bit of a blueprint for the path going forward. There are specific things that need to be done. In research, for example, you have to ensure that datasets are diverse enough. To do that we need to have inter-institutional collaboration. We have to ensure patient privacy. Consent for this needs to be a little more explicit because this is a novel area. Those are things that need to be stipulated and ratified through a task force.”

Dr. Morren has no relevant financial disclosures.

PHOENIX – and it presents opportunities for increased production and automation of some tasks. However, it is prone to error and ‘hallucinations’ despite an authoritative tone, so its conclusions must be verified.

Those were some of the messages from a talk by John Morren, MD, an associate professor of neurology at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, who spoke about AI at the 2023 annual meeting of the American Association for Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM).

He encouraged attendees to get involved in the conversation of AI, because it is here to stay and will have a big impact on health care. “If we’re not around the table making decisions, decisions will be made for us in our absence and won’t be in our favor,” said Dr. Morren.

He started out his talk by asking if anyone in the room had used AI. After about half raised their hands, he countered that nearly everyone likely had. Voice assistants like SIRI and Alexa, social media with curated feeds, online shopping tools that provide product suggestions, and content recommendations from streaming services like Netflix all rely on AI technology.

Within medicine, AI is already playing a role in various fields, including medical imaging, disease diagnosis, drug discovery and development, predictive analytics, personalized medicine, telemedicine, and health care management.

It also has potential to be used on the job. For example, ChatGPT can generate and refine conversations towards a specific length, format, style, and level of detail. Alternatives include Bing AI from Microsoft, Bard AI from Google, Writesonic, Copy.ai, SpinBot, HIX.AI, and Chatsonic.

Specific to medicine, Consensus is a search engine that uses AI to search for, summarize, and synthesize studies from peer-reviewed literature.

Trust, but verify

Dr. Morren presented some specific use cases, including patient education and responses to patient inquiries, as well as generating letters to insurance companies appealing denial of coverage claims. He also showed an example where he asked Bing AI to explain to a patient, at a sixth- to seventh-grade reading level, the red-flag symptoms of myasthenic crisis.

AI can generate summaries of clinical evidence of previous studies. Asked by this reporter how to trust the accuracies of the summaries if the user hasn’t thoroughly read the papers, he acknowledged the imperfection of AI. “I would say that if you’re going to make a decision that you would not have made normally based on the summary that it’s giving, if you can find the fact that you’re anchoring the decision on, go into the article yourself and make sure that it’s well vetted. The AI is just good to tap you on your shoulder and say, ‘hey, just consider this.’ That’s all it is. You should always trust, but verify. If the AI is forcing you to say something new that you would not say, maybe don’t do it – or at least research it to know that it’s the truth and then you elevate yourself and get yourself to the next level.”

Limitations

The need to verify can create its own burden, according to one attendee. “I often find I end up spending more time verifying [what ChatGPT has provided]. This seems to take more time than a traditional way of going to PubMed or UpToDate or any of the other human generated consensus way,” he said.

Dr. Morren replied that he wouldn’t recommend using ChatGPT to query medical literature. Instead he recommended Consensus, which only searches the peer-reviewed medical literature.

Another key limitation is that most AI programs are date limited: For example, ChatGPT doesn’t include information after September 2021, though this may change with paid subscriptions. He also starkly warned the audience to never enter sensitive information, including patient identifiers.

There are legal and ethical considerations to AI. Dr. Morren warned against overreliance on AI, as this could undermine compassion and lead to erosion of trust, which makes it important to disclose any use of AI-generated content.

Another attendee raised concerns that AI may be generating research content, including slides for presentations, abstracts, titles, or article text. Dr. Morren said that some organizations, such as the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, have incorporated AI in their recommendations, stating that authors should disclose any contributions of AI to their publications. However, there is little that can be done to identify AI-generated content, leaving it up to the honor code.

Asked to make predictions about how AI will evolve in the clinic over the next 2-3 years, Dr. Morren suggested that it will likely be embedded in electronic medical records. He anticipated that it will save physicians time so that they can spend more time interacting directly with patients. He quoted Eric Topol, MD, professor of medicine at Scripps Research Translational Institute, La Jolla, Calif., as saying that AI could save 20% of a physician’s time, which could be spent with patients. Dr. Morren saw it differently. “I know where that 20% of time liberated is going to go. I’m going to see 20% more patients. I’m a realist,” he said, to audience laughter.

He also predicted that AI will be found in wearables and devices, allowing health care to expand into the patient’s home in real time. “A lot of what we’re wearing is going to be an extension of the doctor’s office,” he said.

For those hoping for more guidance, Dr. Morren noted that he is the chairman of the professional practice committee of AANEM, and the group will be putting out a position statement within the next couple of months. “It will be a little bit of a blueprint for the path going forward. There are specific things that need to be done. In research, for example, you have to ensure that datasets are diverse enough. To do that we need to have inter-institutional collaboration. We have to ensure patient privacy. Consent for this needs to be a little more explicit because this is a novel area. Those are things that need to be stipulated and ratified through a task force.”

Dr. Morren has no relevant financial disclosures.

AT AANEM 2023

When digestive symptoms signal Parkinson’s disease

The enteric nervous system (ENS), which is regarded as our second brain, is the part of the autonomic nervous system that controls the digestive tract. Housed along the entire length of the digestive tract, it is made up of more than 100 million neurons. It plays a central role in controlling the regulation of gastrointestinal motility, absorption of nutrients, and control of the intestinal barrier that protects the body from external pathogens.

Braak’s hypothesis suggests that the digestive tract could be the starting point for Parkinson’s disease. The fact that nearly all patients with Parkinson’s disease experience digestive problems and have neuropathological lesions in intrinsic and extrinsic innervation of the gastrointestinal tract suggests that Parkinson’s disease also has a gastrointestinal component.

Besides the ascending pathway formulated by Braak, a descending etiology in which gastrointestinal symptoms are present in early stages when neurological signposts have not yet been noticed is supported by evidence from trials. These gastrointestinal symptoms then represent a risk factor. Links have also been described between a history of gastrointestinal symptoms and Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular diseases (CVD), thus justifying studies on a larger scale.

Large combined study

The authors have conducted a combined case-control and cohort study using TriNetX, a national network of medical records based in the United States. They identified 24,624 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease in the case-control analysis and compared them with control subjects without neurological disease. They also identified subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and CVD, to study previous gastrointestinal signs. Secondly, 18 cohorts with each exposure (various gastrointestinal symptoms, appendectomy, vagotomy) were compared with their negative controls (NC) for the development of Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or CVD in 5 years.

Gastroparesis, dysphagia, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) without diarrhea or constipation were shown to have specific associations with Parkinson’s disease (vs. NC, Alzheimer’s disease, and CVD) in both case-controls (odds ratios all P < .0001) and cohort analyses (relative risks all P < .05). While functional dyspepsia, IBS with diarrhea, diarrhea, and fecal incontinence were not specific to Parkinson’s disease, IBS with constipation and intestinal pseudo-obstruction showed specificity to Parkinson’s disease in the case-control (OR, 4.11) and cohort (RR, 1.84) analyses. Appendectomy reduced the risk of Parkinson’s disease in the cohort study (RR, 0.48). Neither inflammatory bowel disease nor vagotomy was associated with Parkinson’s disease.

A ‘second brain’

This broad study attempted to explore the gut-brain axis by looking for associations between neurological diagnoses and prior gastrointestinal symptoms and later development of Parkinson’s disease. After adjustment to account for multiple comparisons and acknowledgment of the initial risk in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and CVD, only dysphagia, gastroparesis, IBS without diarrhea, and isolated constipation were significantly and specifically associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Numerous literature reviews mention that ENS lesions are responsible for gastrointestinal disorders observed in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Tests on gastrointestinal autopsy and biopsy specimens have established that alpha synuclein clusters, which are morphologically similar to Lewy bodies in the CNS, are seen in the vagus nerve and in the ENS in most subjects with Parkinson’s disease. However, these studies have not shown any loss of neurons in the ENS in Parkinson’s disease, and the presence of alpha synuclein deposits in the ENS is not sufficient in itself to explain these gastrointestinal disorders.

It therefore remains to be determined whether vagal nerve damage alone can explain gastrointestinal disorders or whether dysfunction of enteric neurons without neuronal loss is occurring. So, damage to the ENS from alpha synuclein deposits would be early and would precede damage to the CNS, thus affording evidence in support of Braak’s hypothesis, which relies on autopsy data that does not allow for longitudinal monitoring in a single individual.

Appendectomy appeared to be protective, leading to additional speculation about its role in the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Additional mechanistic studies are therefore needed to establish causality and confirm the gut-brain axis or the role of dysbiosis and of intestinal permeability problems.

In conclusion, this large, first-of-its-kind multicenter study conducted on a national scale shows that Subject to future longitudinal mechanistic studies, early detection of these gastrointestinal disorders could aid in identifying patients at risk of Parkinson’s, and it could then be assumed that disease-modifying treatments could, at this early stage, halt progression of the disease linked to toxic clusters of alpha synuclein.

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape professional network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The enteric nervous system (ENS), which is regarded as our second brain, is the part of the autonomic nervous system that controls the digestive tract. Housed along the entire length of the digestive tract, it is made up of more than 100 million neurons. It plays a central role in controlling the regulation of gastrointestinal motility, absorption of nutrients, and control of the intestinal barrier that protects the body from external pathogens.

Braak’s hypothesis suggests that the digestive tract could be the starting point for Parkinson’s disease. The fact that nearly all patients with Parkinson’s disease experience digestive problems and have neuropathological lesions in intrinsic and extrinsic innervation of the gastrointestinal tract suggests that Parkinson’s disease also has a gastrointestinal component.

Besides the ascending pathway formulated by Braak, a descending etiology in which gastrointestinal symptoms are present in early stages when neurological signposts have not yet been noticed is supported by evidence from trials. These gastrointestinal symptoms then represent a risk factor. Links have also been described between a history of gastrointestinal symptoms and Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular diseases (CVD), thus justifying studies on a larger scale.

Large combined study

The authors have conducted a combined case-control and cohort study using TriNetX, a national network of medical records based in the United States. They identified 24,624 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease in the case-control analysis and compared them with control subjects without neurological disease. They also identified subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and CVD, to study previous gastrointestinal signs. Secondly, 18 cohorts with each exposure (various gastrointestinal symptoms, appendectomy, vagotomy) were compared with their negative controls (NC) for the development of Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or CVD in 5 years.

Gastroparesis, dysphagia, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) without diarrhea or constipation were shown to have specific associations with Parkinson’s disease (vs. NC, Alzheimer’s disease, and CVD) in both case-controls (odds ratios all P < .0001) and cohort analyses (relative risks all P < .05). While functional dyspepsia, IBS with diarrhea, diarrhea, and fecal incontinence were not specific to Parkinson’s disease, IBS with constipation and intestinal pseudo-obstruction showed specificity to Parkinson’s disease in the case-control (OR, 4.11) and cohort (RR, 1.84) analyses. Appendectomy reduced the risk of Parkinson’s disease in the cohort study (RR, 0.48). Neither inflammatory bowel disease nor vagotomy was associated with Parkinson’s disease.

A ‘second brain’

This broad study attempted to explore the gut-brain axis by looking for associations between neurological diagnoses and prior gastrointestinal symptoms and later development of Parkinson’s disease. After adjustment to account for multiple comparisons and acknowledgment of the initial risk in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and CVD, only dysphagia, gastroparesis, IBS without diarrhea, and isolated constipation were significantly and specifically associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Numerous literature reviews mention that ENS lesions are responsible for gastrointestinal disorders observed in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Tests on gastrointestinal autopsy and biopsy specimens have established that alpha synuclein clusters, which are morphologically similar to Lewy bodies in the CNS, are seen in the vagus nerve and in the ENS in most subjects with Parkinson’s disease. However, these studies have not shown any loss of neurons in the ENS in Parkinson’s disease, and the presence of alpha synuclein deposits in the ENS is not sufficient in itself to explain these gastrointestinal disorders.

It therefore remains to be determined whether vagal nerve damage alone can explain gastrointestinal disorders or whether dysfunction of enteric neurons without neuronal loss is occurring. So, damage to the ENS from alpha synuclein deposits would be early and would precede damage to the CNS, thus affording evidence in support of Braak’s hypothesis, which relies on autopsy data that does not allow for longitudinal monitoring in a single individual.

Appendectomy appeared to be protective, leading to additional speculation about its role in the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Additional mechanistic studies are therefore needed to establish causality and confirm the gut-brain axis or the role of dysbiosis and of intestinal permeability problems.

In conclusion, this large, first-of-its-kind multicenter study conducted on a national scale shows that Subject to future longitudinal mechanistic studies, early detection of these gastrointestinal disorders could aid in identifying patients at risk of Parkinson’s, and it could then be assumed that disease-modifying treatments could, at this early stage, halt progression of the disease linked to toxic clusters of alpha synuclein.

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape professional network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The enteric nervous system (ENS), which is regarded as our second brain, is the part of the autonomic nervous system that controls the digestive tract. Housed along the entire length of the digestive tract, it is made up of more than 100 million neurons. It plays a central role in controlling the regulation of gastrointestinal motility, absorption of nutrients, and control of the intestinal barrier that protects the body from external pathogens.

Braak’s hypothesis suggests that the digestive tract could be the starting point for Parkinson’s disease. The fact that nearly all patients with Parkinson’s disease experience digestive problems and have neuropathological lesions in intrinsic and extrinsic innervation of the gastrointestinal tract suggests that Parkinson’s disease also has a gastrointestinal component.

Besides the ascending pathway formulated by Braak, a descending etiology in which gastrointestinal symptoms are present in early stages when neurological signposts have not yet been noticed is supported by evidence from trials. These gastrointestinal symptoms then represent a risk factor. Links have also been described between a history of gastrointestinal symptoms and Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular diseases (CVD), thus justifying studies on a larger scale.

Large combined study

The authors have conducted a combined case-control and cohort study using TriNetX, a national network of medical records based in the United States. They identified 24,624 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease in the case-control analysis and compared them with control subjects without neurological disease. They also identified subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and CVD, to study previous gastrointestinal signs. Secondly, 18 cohorts with each exposure (various gastrointestinal symptoms, appendectomy, vagotomy) were compared with their negative controls (NC) for the development of Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, or CVD in 5 years.

Gastroparesis, dysphagia, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) without diarrhea or constipation were shown to have specific associations with Parkinson’s disease (vs. NC, Alzheimer’s disease, and CVD) in both case-controls (odds ratios all P < .0001) and cohort analyses (relative risks all P < .05). While functional dyspepsia, IBS with diarrhea, diarrhea, and fecal incontinence were not specific to Parkinson’s disease, IBS with constipation and intestinal pseudo-obstruction showed specificity to Parkinson’s disease in the case-control (OR, 4.11) and cohort (RR, 1.84) analyses. Appendectomy reduced the risk of Parkinson’s disease in the cohort study (RR, 0.48). Neither inflammatory bowel disease nor vagotomy was associated with Parkinson’s disease.

A ‘second brain’

This broad study attempted to explore the gut-brain axis by looking for associations between neurological diagnoses and prior gastrointestinal symptoms and later development of Parkinson’s disease. After adjustment to account for multiple comparisons and acknowledgment of the initial risk in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and CVD, only dysphagia, gastroparesis, IBS without diarrhea, and isolated constipation were significantly and specifically associated with Parkinson’s disease.

Numerous literature reviews mention that ENS lesions are responsible for gastrointestinal disorders observed in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Tests on gastrointestinal autopsy and biopsy specimens have established that alpha synuclein clusters, which are morphologically similar to Lewy bodies in the CNS, are seen in the vagus nerve and in the ENS in most subjects with Parkinson’s disease. However, these studies have not shown any loss of neurons in the ENS in Parkinson’s disease, and the presence of alpha synuclein deposits in the ENS is not sufficient in itself to explain these gastrointestinal disorders.

It therefore remains to be determined whether vagal nerve damage alone can explain gastrointestinal disorders or whether dysfunction of enteric neurons without neuronal loss is occurring. So, damage to the ENS from alpha synuclein deposits would be early and would precede damage to the CNS, thus affording evidence in support of Braak’s hypothesis, which relies on autopsy data that does not allow for longitudinal monitoring in a single individual.

Appendectomy appeared to be protective, leading to additional speculation about its role in the pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Additional mechanistic studies are therefore needed to establish causality and confirm the gut-brain axis or the role of dysbiosis and of intestinal permeability problems.

In conclusion, this large, first-of-its-kind multicenter study conducted on a national scale shows that Subject to future longitudinal mechanistic studies, early detection of these gastrointestinal disorders could aid in identifying patients at risk of Parkinson’s, and it could then be assumed that disease-modifying treatments could, at this early stage, halt progression of the disease linked to toxic clusters of alpha synuclein.

This article was translated from JIM, which is part of the Medscape professional network.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new clue into the cause, spread of Parkinson’s disease?

.

While defects in mitochondrial functions and in mitochondrial DNA have been implicated in PD in the past, the current study demonstrates “for the first time how damaged mitochondrial DNA can underlie the mechanisms of PD initiation and spread in brain,” lead investigator Shohreh Issazadeh-Navikas, PhD, with the University of Copenhagen, told this news organization.

“This has direct implication for clinical diagnosis” – if damaged mtDNA can be detected in blood, it could serve as an early biomarker for disease, she explained.

The study was published online in Molecular Psychiatry.

“Infectious-like” spread of PD pathology

In earlier work, the researchers identified dysregulated interferon-beta (IFN-beta) signaling as a “top candidate pathway” associated with sporadic PD and its progression to PD with dementia (PDD).

In mice PD models that were deficient in IFN-beta signaling, the investigators showed that neuronal IFN-beta is required to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and metabolism.

Lack of neuronal IFN-beta or disruption of its downstream signaling causes the accumulation of damaged mitochondria with excessive oxidative stress and insufficient adenosine triphosphate production.

In the current study, using postmortem brain tissue samples from patients with sporadic PD, they confirmed that there were deletions of mtDNA in the medial frontal gyrus, a region implicated in cognitive impairments in PD, suggesting a potential role of damaged mtDNA in disease pathophysiology.

They also identified mtDNA deletions in a “hotspot” in complex I respiratory chain subunits that were associated with dysregulation of oxidative stress and DNA damage response pathways in cohorts with sporadic PD and PDD.

They confirmed the contribution of mtDNA damage to PD pathology in the PD mouse models. They showed that lack of neuronal IFN-beta signaling leads to oxidative damage and mutations in mtDNA in neurons, which are subsequently released outside the neurons.

Injecting damaged mtDNA into mouse brain induced PDD-like behavioral symptoms, including neuropsychiatric, motor, and cognitive impairments. It also caused neurodegeneration in brain regions distant from the injection site, suggesting that damaged mtDNA triggers spread of PDD characteristics in an “infectious-like” manner, the researchers report.

Further study revealed that the mechanism through which damaged mtDNA causes pathology in healthy neurons involves dual activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 and 4 pathways, leading to increased oxidative stress and neuronal cell death, respectively.

“Our proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles containing damaged mtDNA identified the TLR4 activator, ribosomal protein S3, as a key protein involved in recognizing and extruding damaged mtDNA,” the investigators write.

In the future they plan to investigate how mtDNA damage can serve as a predictive marker for different disease stages and progression and to explore potential therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring normal mitochondrial function to rectify the mitochondrial dysfunctions implicated in PD.

Making a comeback?

Commenting on the research for this news organization, James Beck, PhD, chief scientific officer at the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the role of mitochondria in PD is “like a starlet that burst onto the scene in the 80s, faded into obscurity, and through diligence and continued research has moved beyond being a solid character actor and is reemerging as a force to reckon with.

“This paper only adds to the allure that mitochondria may have in contributing to PD by providing evidence of a novel process by which mitochondria may be not only contributing to PD and loss of dopamine neurons but may play a larger role in the subsequent effects that many people with PD experience – dementia,” Dr. Beck said.

He noted that the authors identified several proteins as facilitating the neurodegeneration that is wrought by damaged mitochondrial DNA.

“These could be potential targets for future drug development. In addition, this work implicates alterations in immune signaling and drugs in development to target inflammatory responses may also bring ancillary benefit,” Dr. Beck said.

However, he said, “while very interesting findings, this is really the first effort that demonstrates how damaged mitochondrial DNA may contribute to neurodegeneration in the context of PD and PD dementia. Further work needs to validate these findings as well as to elucidate mechanisms underlying the propagation of the mitochondrial DNA from cell to cell.”

Funding for this research was provided by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Lundbeck Foundation, and the Danish Council for Independent Research–Medicine. Dr. Issazadeh-Navikas and Dr. Beck have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

While defects in mitochondrial functions and in mitochondrial DNA have been implicated in PD in the past, the current study demonstrates “for the first time how damaged mitochondrial DNA can underlie the mechanisms of PD initiation and spread in brain,” lead investigator Shohreh Issazadeh-Navikas, PhD, with the University of Copenhagen, told this news organization.

“This has direct implication for clinical diagnosis” – if damaged mtDNA can be detected in blood, it could serve as an early biomarker for disease, she explained.

The study was published online in Molecular Psychiatry.

“Infectious-like” spread of PD pathology

In earlier work, the researchers identified dysregulated interferon-beta (IFN-beta) signaling as a “top candidate pathway” associated with sporadic PD and its progression to PD with dementia (PDD).

In mice PD models that were deficient in IFN-beta signaling, the investigators showed that neuronal IFN-beta is required to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and metabolism.

Lack of neuronal IFN-beta or disruption of its downstream signaling causes the accumulation of damaged mitochondria with excessive oxidative stress and insufficient adenosine triphosphate production.

In the current study, using postmortem brain tissue samples from patients with sporadic PD, they confirmed that there were deletions of mtDNA in the medial frontal gyrus, a region implicated in cognitive impairments in PD, suggesting a potential role of damaged mtDNA in disease pathophysiology.

They also identified mtDNA deletions in a “hotspot” in complex I respiratory chain subunits that were associated with dysregulation of oxidative stress and DNA damage response pathways in cohorts with sporadic PD and PDD.

They confirmed the contribution of mtDNA damage to PD pathology in the PD mouse models. They showed that lack of neuronal IFN-beta signaling leads to oxidative damage and mutations in mtDNA in neurons, which are subsequently released outside the neurons.

Injecting damaged mtDNA into mouse brain induced PDD-like behavioral symptoms, including neuropsychiatric, motor, and cognitive impairments. It also caused neurodegeneration in brain regions distant from the injection site, suggesting that damaged mtDNA triggers spread of PDD characteristics in an “infectious-like” manner, the researchers report.

Further study revealed that the mechanism through which damaged mtDNA causes pathology in healthy neurons involves dual activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 and 4 pathways, leading to increased oxidative stress and neuronal cell death, respectively.

“Our proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles containing damaged mtDNA identified the TLR4 activator, ribosomal protein S3, as a key protein involved in recognizing and extruding damaged mtDNA,” the investigators write.

In the future they plan to investigate how mtDNA damage can serve as a predictive marker for different disease stages and progression and to explore potential therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring normal mitochondrial function to rectify the mitochondrial dysfunctions implicated in PD.

Making a comeback?

Commenting on the research for this news organization, James Beck, PhD, chief scientific officer at the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the role of mitochondria in PD is “like a starlet that burst onto the scene in the 80s, faded into obscurity, and through diligence and continued research has moved beyond being a solid character actor and is reemerging as a force to reckon with.

“This paper only adds to the allure that mitochondria may have in contributing to PD by providing evidence of a novel process by which mitochondria may be not only contributing to PD and loss of dopamine neurons but may play a larger role in the subsequent effects that many people with PD experience – dementia,” Dr. Beck said.

He noted that the authors identified several proteins as facilitating the neurodegeneration that is wrought by damaged mitochondrial DNA.

“These could be potential targets for future drug development. In addition, this work implicates alterations in immune signaling and drugs in development to target inflammatory responses may also bring ancillary benefit,” Dr. Beck said.

However, he said, “while very interesting findings, this is really the first effort that demonstrates how damaged mitochondrial DNA may contribute to neurodegeneration in the context of PD and PD dementia. Further work needs to validate these findings as well as to elucidate mechanisms underlying the propagation of the mitochondrial DNA from cell to cell.”

Funding for this research was provided by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Lundbeck Foundation, and the Danish Council for Independent Research–Medicine. Dr. Issazadeh-Navikas and Dr. Beck have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

.

While defects in mitochondrial functions and in mitochondrial DNA have been implicated in PD in the past, the current study demonstrates “for the first time how damaged mitochondrial DNA can underlie the mechanisms of PD initiation and spread in brain,” lead investigator Shohreh Issazadeh-Navikas, PhD, with the University of Copenhagen, told this news organization.

“This has direct implication for clinical diagnosis” – if damaged mtDNA can be detected in blood, it could serve as an early biomarker for disease, she explained.

The study was published online in Molecular Psychiatry.

“Infectious-like” spread of PD pathology

In earlier work, the researchers identified dysregulated interferon-beta (IFN-beta) signaling as a “top candidate pathway” associated with sporadic PD and its progression to PD with dementia (PDD).

In mice PD models that were deficient in IFN-beta signaling, the investigators showed that neuronal IFN-beta is required to maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and metabolism.

Lack of neuronal IFN-beta or disruption of its downstream signaling causes the accumulation of damaged mitochondria with excessive oxidative stress and insufficient adenosine triphosphate production.

In the current study, using postmortem brain tissue samples from patients with sporadic PD, they confirmed that there were deletions of mtDNA in the medial frontal gyrus, a region implicated in cognitive impairments in PD, suggesting a potential role of damaged mtDNA in disease pathophysiology.

They also identified mtDNA deletions in a “hotspot” in complex I respiratory chain subunits that were associated with dysregulation of oxidative stress and DNA damage response pathways in cohorts with sporadic PD and PDD.

They confirmed the contribution of mtDNA damage to PD pathology in the PD mouse models. They showed that lack of neuronal IFN-beta signaling leads to oxidative damage and mutations in mtDNA in neurons, which are subsequently released outside the neurons.

Injecting damaged mtDNA into mouse brain induced PDD-like behavioral symptoms, including neuropsychiatric, motor, and cognitive impairments. It also caused neurodegeneration in brain regions distant from the injection site, suggesting that damaged mtDNA triggers spread of PDD characteristics in an “infectious-like” manner, the researchers report.

Further study revealed that the mechanism through which damaged mtDNA causes pathology in healthy neurons involves dual activation of Toll-like receptor (TLR) 9 and 4 pathways, leading to increased oxidative stress and neuronal cell death, respectively.

“Our proteomic analysis of extracellular vesicles containing damaged mtDNA identified the TLR4 activator, ribosomal protein S3, as a key protein involved in recognizing and extruding damaged mtDNA,” the investigators write.

In the future they plan to investigate how mtDNA damage can serve as a predictive marker for different disease stages and progression and to explore potential therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring normal mitochondrial function to rectify the mitochondrial dysfunctions implicated in PD.

Making a comeback?

Commenting on the research for this news organization, James Beck, PhD, chief scientific officer at the Parkinson’s Foundation, noted that the role of mitochondria in PD is “like a starlet that burst onto the scene in the 80s, faded into obscurity, and through diligence and continued research has moved beyond being a solid character actor and is reemerging as a force to reckon with.

“This paper only adds to the allure that mitochondria may have in contributing to PD by providing evidence of a novel process by which mitochondria may be not only contributing to PD and loss of dopamine neurons but may play a larger role in the subsequent effects that many people with PD experience – dementia,” Dr. Beck said.

He noted that the authors identified several proteins as facilitating the neurodegeneration that is wrought by damaged mitochondrial DNA.

“These could be potential targets for future drug development. In addition, this work implicates alterations in immune signaling and drugs in development to target inflammatory responses may also bring ancillary benefit,” Dr. Beck said.

However, he said, “while very interesting findings, this is really the first effort that demonstrates how damaged mitochondrial DNA may contribute to neurodegeneration in the context of PD and PD dementia. Further work needs to validate these findings as well as to elucidate mechanisms underlying the propagation of the mitochondrial DNA from cell to cell.”

Funding for this research was provided by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, the Lundbeck Foundation, and the Danish Council for Independent Research–Medicine. Dr. Issazadeh-Navikas and Dr. Beck have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM MOLECULAR PSYCHIATRY

Loneliness tied to increased risk for Parkinson’s disease

TOPLINE:

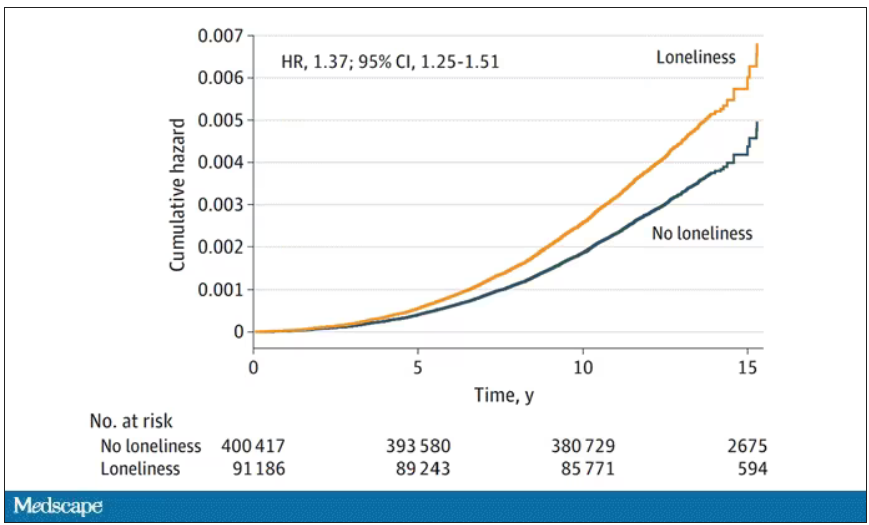

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Antonio Terracciano, PhD, of Florida State University College of Medicine, Tallahassee, was published online in JAMA Neurology.

LIMITATIONS:

This observational study could not determine causality or whether reverse causality could explain the association. Loneliness was assessed by a single yes/no question. PD diagnosis relied on hospital admission and death records and may have missed early PD diagnoses.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institutes of Health and National Institute on Aging. The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Loneliness is associated with a higher risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) across demographic groups and independent of other risk factors, data from nearly 500,000 U.K. adults suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- Loneliness is associated with illness and death, including higher risk of neurodegenerative diseases, but no study has examined whether the association between loneliness and detrimental outcomes extends to PD.

- The current analysis included 491,603 U.K. Biobank participants (mean age, 56; 54% women) without a diagnosis of PD at baseline.

- Loneliness was assessed by a single question at baseline and incident PD was ascertained via health records over 15 years.

- Researchers assessed whether the association between loneliness and PD was moderated by age, sex, or genetic risk and whether the association was accounted for by sociodemographic factors; behavioral, mental, physical, or social factors; or genetic risk.

TAKEAWAY:

- Roughly 19% of the cohort reported being lonely. Compared with those who were not lonely, those who did report being lonely were slightly younger and were more likely to be women. They also had fewer resources, more health risk behaviors (current smoker and physically inactive), and worse physical and mental health.

- Over 15+ years of follow-up, 2,822 participants developed PD (incidence rate: 47 per 100,000 person-years). Compared with those who did not develop PD, those who did were older and more likely to be male, former smokers, have higher BMI and PD polygenetic risk score, and to have diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction or stroke, anxiety, or depression.

- In the primary analysis, individuals who reported being lonely had a higher risk for PD (hazard ratio, 1.37) – an association that remained after accounting for demographic and socioeconomic status, social isolation, PD polygenetic risk score, smoking, physical activity, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, myocardial infarction, depression, and having ever seen a psychiatrist (fully adjusted HR, 1.25).

- The association between loneliness and incident PD was not moderated by sex, age, or polygenetic risk score.

- Contrary to expectations for a prodromal syndrome, loneliness was not associated with incident PD in the first 5 years after baseline but was associated with PD risk in the subsequent 10 years of follow-up (HR, 1.32).

IN PRACTICE:

“Our findings complement other evidence that loneliness is a psychosocial determinant of health associated with increased risk of morbidity and mortality [and] supports recent calls for the protective and healing effects of personally meaningful social connection,” the authors write.

SOURCE: