User login

ART Linked With Congenital Heart Defects in Newborns

The rate of congenital heart defects is higher in newborns conceived using assisted reproductive technologies (ART) than in newborns conceived without assistance. This finding comes from a population-based cohort study led by Dr. Nona Sargisian, a gynecologist at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and colleagues, which was published in the European Heart Journal.

The researchers analyzed more than 7 million results of all live-born children in Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Norway between 1984 and 2015. They found that congenital heart defects occurred more frequently in the ART newborn group (1.85%) than in naturally conceived newborns (1.15%).

The study also revealed that the risk for congenital heart defects in multiple births is higher than in single births, with and without the use of ART. However, the result that congenital heart defects occur more often in ART newborns remained significant when comparing single births from both groups (1.62% vs 1.11%).

Relatively Low Prevalence

Barbara Sonntag, MD, PhD, a gynecologist at Amedes Fertility Center in Hamburg, Germany, referred to a “clinically relevant risk increase” with a relatively low prevalence of the condition.

“When 1000 children are born, an abnormality occurs in 18 children after ART, compared with 11 children born after natural conception,” she told the Science Media Center.

Dr. Sonntag emphasized that the risk is particularly increased by a multiple pregnancy. A statement about causality is not possible based on the study, but multiple pregnancies are generally associated with increased risks during pregnancy and for the children.

The large and robust dataset confirms long-known findings, said Georg Griesinger, MD, PhD, medical director of the fertility centers of the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Lübeck and Manhagen, Germany.

The key figures can be found in single births, he explained. “Among single births conceived by ART, the rate of severe congenital heart defects was 1.62% compared with 1.11% in spontaneously conceived single births, an increase in risk by 1.19 times. For severe heart defects, the rate was 0.31% in ART single births, compared with 0.25% in spontaneously conceived single births.”

The increased risks are consistent with existing literature. Therefore, the current study does not reveal any new risk signals, said Dr. Griesinger.

Single Embryo Transfer

The “risks are small but present,” according to Michael von Wolff, MD, head of gynecological endocrinology and reproductive medicine at Bern University Hospital in Switzerland. “Therefore, ART therapy should only be carried out after exhausting conservative treatments,” he recommended. For example, ovarian stimulation with low-dose hormone preparations could be an option.

Dr. Griesinger pointed out that, in absolute numbers, all maternal and fetal or neonatal risks are significantly increased in twins and higher-order multiples, compared with the estimated risk association within the actual ART treatment.

“For this reason, reproductive medicine specialists have been advocating for single-embryo transfer for years to promote the occurrence of single pregnancies through ART,” said Dr. Griesinger.

The study “emphasizes the importance of single embryo transfer to avoid the higher risks associated with multiple pregnancies,” according to Rocío Núñez Calonge, PhD, scientific director of the International Reproduction Unit in Alicante, Spain.

Dr. Sonntag also sees a “strong additional call to avoid multiple pregnancies through a predominant strategy of single-embryo transfer in the data. The increased rate of childhood birth defects is already part of the information provided before assisted reproduction.”

This story was translated from the Medscape German edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The rate of congenital heart defects is higher in newborns conceived using assisted reproductive technologies (ART) than in newborns conceived without assistance. This finding comes from a population-based cohort study led by Dr. Nona Sargisian, a gynecologist at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and colleagues, which was published in the European Heart Journal.

The researchers analyzed more than 7 million results of all live-born children in Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Norway between 1984 and 2015. They found that congenital heart defects occurred more frequently in the ART newborn group (1.85%) than in naturally conceived newborns (1.15%).

The study also revealed that the risk for congenital heart defects in multiple births is higher than in single births, with and without the use of ART. However, the result that congenital heart defects occur more often in ART newborns remained significant when comparing single births from both groups (1.62% vs 1.11%).

Relatively Low Prevalence

Barbara Sonntag, MD, PhD, a gynecologist at Amedes Fertility Center in Hamburg, Germany, referred to a “clinically relevant risk increase” with a relatively low prevalence of the condition.

“When 1000 children are born, an abnormality occurs in 18 children after ART, compared with 11 children born after natural conception,” she told the Science Media Center.

Dr. Sonntag emphasized that the risk is particularly increased by a multiple pregnancy. A statement about causality is not possible based on the study, but multiple pregnancies are generally associated with increased risks during pregnancy and for the children.

The large and robust dataset confirms long-known findings, said Georg Griesinger, MD, PhD, medical director of the fertility centers of the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Lübeck and Manhagen, Germany.

The key figures can be found in single births, he explained. “Among single births conceived by ART, the rate of severe congenital heart defects was 1.62% compared with 1.11% in spontaneously conceived single births, an increase in risk by 1.19 times. For severe heart defects, the rate was 0.31% in ART single births, compared with 0.25% in spontaneously conceived single births.”

The increased risks are consistent with existing literature. Therefore, the current study does not reveal any new risk signals, said Dr. Griesinger.

Single Embryo Transfer

The “risks are small but present,” according to Michael von Wolff, MD, head of gynecological endocrinology and reproductive medicine at Bern University Hospital in Switzerland. “Therefore, ART therapy should only be carried out after exhausting conservative treatments,” he recommended. For example, ovarian stimulation with low-dose hormone preparations could be an option.

Dr. Griesinger pointed out that, in absolute numbers, all maternal and fetal or neonatal risks are significantly increased in twins and higher-order multiples, compared with the estimated risk association within the actual ART treatment.

“For this reason, reproductive medicine specialists have been advocating for single-embryo transfer for years to promote the occurrence of single pregnancies through ART,” said Dr. Griesinger.

The study “emphasizes the importance of single embryo transfer to avoid the higher risks associated with multiple pregnancies,” according to Rocío Núñez Calonge, PhD, scientific director of the International Reproduction Unit in Alicante, Spain.

Dr. Sonntag also sees a “strong additional call to avoid multiple pregnancies through a predominant strategy of single-embryo transfer in the data. The increased rate of childhood birth defects is already part of the information provided before assisted reproduction.”

This story was translated from the Medscape German edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The rate of congenital heart defects is higher in newborns conceived using assisted reproductive technologies (ART) than in newborns conceived without assistance. This finding comes from a population-based cohort study led by Dr. Nona Sargisian, a gynecologist at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, and colleagues, which was published in the European Heart Journal.

The researchers analyzed more than 7 million results of all live-born children in Denmark, Finland, Sweden, and Norway between 1984 and 2015. They found that congenital heart defects occurred more frequently in the ART newborn group (1.85%) than in naturally conceived newborns (1.15%).

The study also revealed that the risk for congenital heart defects in multiple births is higher than in single births, with and without the use of ART. However, the result that congenital heart defects occur more often in ART newborns remained significant when comparing single births from both groups (1.62% vs 1.11%).

Relatively Low Prevalence

Barbara Sonntag, MD, PhD, a gynecologist at Amedes Fertility Center in Hamburg, Germany, referred to a “clinically relevant risk increase” with a relatively low prevalence of the condition.

“When 1000 children are born, an abnormality occurs in 18 children after ART, compared with 11 children born after natural conception,” she told the Science Media Center.

Dr. Sonntag emphasized that the risk is particularly increased by a multiple pregnancy. A statement about causality is not possible based on the study, but multiple pregnancies are generally associated with increased risks during pregnancy and for the children.

The large and robust dataset confirms long-known findings, said Georg Griesinger, MD, PhD, medical director of the fertility centers of the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Lübeck and Manhagen, Germany.

The key figures can be found in single births, he explained. “Among single births conceived by ART, the rate of severe congenital heart defects was 1.62% compared with 1.11% in spontaneously conceived single births, an increase in risk by 1.19 times. For severe heart defects, the rate was 0.31% in ART single births, compared with 0.25% in spontaneously conceived single births.”

The increased risks are consistent with existing literature. Therefore, the current study does not reveal any new risk signals, said Dr. Griesinger.

Single Embryo Transfer

The “risks are small but present,” according to Michael von Wolff, MD, head of gynecological endocrinology and reproductive medicine at Bern University Hospital in Switzerland. “Therefore, ART therapy should only be carried out after exhausting conservative treatments,” he recommended. For example, ovarian stimulation with low-dose hormone preparations could be an option.

Dr. Griesinger pointed out that, in absolute numbers, all maternal and fetal or neonatal risks are significantly increased in twins and higher-order multiples, compared with the estimated risk association within the actual ART treatment.

“For this reason, reproductive medicine specialists have been advocating for single-embryo transfer for years to promote the occurrence of single pregnancies through ART,” said Dr. Griesinger.

The study “emphasizes the importance of single embryo transfer to avoid the higher risks associated with multiple pregnancies,” according to Rocío Núñez Calonge, PhD, scientific director of the International Reproduction Unit in Alicante, Spain.

Dr. Sonntag also sees a “strong additional call to avoid multiple pregnancies through a predominant strategy of single-embryo transfer in the data. The increased rate of childhood birth defects is already part of the information provided before assisted reproduction.”

This story was translated from the Medscape German edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL

CBD Use in Pregnant People Double That of Nonpregnant Counterparts

Pregnant women in a large North American sample reported nearly double the rate of cannabidiol (CBD) use compared with nonpregnant women, new data published in a research letter in Obstetrics & Gynecology indicates.

Healthcare providers should be aware of the high rate of CBD use in pregnancy, especially as legal use of cannabis is increasing faster than evidence on outcomes for exposed offspring, note the researchers, led by Devika Bhatia, MD, from the Department of Psychiatry, Colorado School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

In an accompanying editorial, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, deputy editor for obstetrics for Obstetrics & Gynecology, writes that the study “is critically important.” She points out that pregnant individuals may perceive that CBD is a safe drug to use in pregnancy, despite there being essentially no data examining whether or not this is the case.

Large Dataset From United States and Canada

Researchers used data from the International Cannabis Policy Study (2019-2021), a repeated cross-sectional survey of people aged 16-65 years in the United States and Canada. There were 66,457 women in the sample, including 1096 pregnant women.

Particularly concerning, the authors write, is the prenatal use of CBD-only products. Those products are advertised to contain only CBD, rather than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They point out CBD-only products are often legal in North America and often marketed as supplements.

The prevalence of CBD-only use in pregnant women in the study was 20.4% compared with 11.3% among nonpregnant women, P < .001. The top reason for use by pregnant women was anxiety (58.4%). Other top reasons included depression (40.3%), posttraumatic stress disorder (32.1%), pain (52.3%), headache (35.6%), and nausea or vomiting (31.9%).

“Nonpregnant women were significantly more likely to report using CBD for pain, sleep, general well-being, and ‘other’ physical or mental health reasons, or to not use CBD for mental health,” the authors write, adding that the reasons for CBD use highlight drivers that may be important to address in treating pregnant patients.

Provider Endorsement in Some Cases

Dr. Metz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology with the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, says in some cases women may be getting endorsement of CBD use from their provider or at least implied support when CBD is prescribed. In the study, pregnant women had 2.33 times greater adjusted odds of having a CBD prescription than nonpregnant women (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.88).

She points to another cross-sectional study of more than 10,000 participants using PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) data that found that “from 2017 to 2019, 63% of pregnant women reported that they were not told to avoid cannabis use in pregnancy, and 8% noted that they were advised to use cannabis by their prenatal care practitioner.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against prescribing cannabis products for pregnant or lactating women.

Studies that have explored THC and its metabolites have shown “a consistent association between cannabis use and decreased fetal growth,” Dr. Metz noted. “There also remain persistent concerns about the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of maternal cannabis use on the fetus and, subsequently, the newborn.”

Limitations of the study include the self-reported responses and participants’ ability to accurately distinguish between CBD-only and THC-containing products.

Because self-reports of CBD use in pregnancy may be drastically underestimated and nonreliable, Dr. Metz writes, development of blood and urine screens to help detect CBD product use “will be helpful in moving the field forward.”

Study senior author David Hammond, PhD, has been a paid expert witness on behalf of public health authorities in response to legal challenges from the cannabis, tobacco, vaping, and food industries. Other authors did not report any potential conflicts. Dr. Metz reports personal fees from Pfizer, and grants from Pfizer for her role as a site principal investigator for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and for her role as a site PI for RSV vaccination in pregnancy study.

Pregnant women in a large North American sample reported nearly double the rate of cannabidiol (CBD) use compared with nonpregnant women, new data published in a research letter in Obstetrics & Gynecology indicates.

Healthcare providers should be aware of the high rate of CBD use in pregnancy, especially as legal use of cannabis is increasing faster than evidence on outcomes for exposed offspring, note the researchers, led by Devika Bhatia, MD, from the Department of Psychiatry, Colorado School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

In an accompanying editorial, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, deputy editor for obstetrics for Obstetrics & Gynecology, writes that the study “is critically important.” She points out that pregnant individuals may perceive that CBD is a safe drug to use in pregnancy, despite there being essentially no data examining whether or not this is the case.

Large Dataset From United States and Canada

Researchers used data from the International Cannabis Policy Study (2019-2021), a repeated cross-sectional survey of people aged 16-65 years in the United States and Canada. There were 66,457 women in the sample, including 1096 pregnant women.

Particularly concerning, the authors write, is the prenatal use of CBD-only products. Those products are advertised to contain only CBD, rather than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They point out CBD-only products are often legal in North America and often marketed as supplements.

The prevalence of CBD-only use in pregnant women in the study was 20.4% compared with 11.3% among nonpregnant women, P < .001. The top reason for use by pregnant women was anxiety (58.4%). Other top reasons included depression (40.3%), posttraumatic stress disorder (32.1%), pain (52.3%), headache (35.6%), and nausea or vomiting (31.9%).

“Nonpregnant women were significantly more likely to report using CBD for pain, sleep, general well-being, and ‘other’ physical or mental health reasons, or to not use CBD for mental health,” the authors write, adding that the reasons for CBD use highlight drivers that may be important to address in treating pregnant patients.

Provider Endorsement in Some Cases

Dr. Metz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology with the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, says in some cases women may be getting endorsement of CBD use from their provider or at least implied support when CBD is prescribed. In the study, pregnant women had 2.33 times greater adjusted odds of having a CBD prescription than nonpregnant women (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.88).

She points to another cross-sectional study of more than 10,000 participants using PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) data that found that “from 2017 to 2019, 63% of pregnant women reported that they were not told to avoid cannabis use in pregnancy, and 8% noted that they were advised to use cannabis by their prenatal care practitioner.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against prescribing cannabis products for pregnant or lactating women.

Studies that have explored THC and its metabolites have shown “a consistent association between cannabis use and decreased fetal growth,” Dr. Metz noted. “There also remain persistent concerns about the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of maternal cannabis use on the fetus and, subsequently, the newborn.”

Limitations of the study include the self-reported responses and participants’ ability to accurately distinguish between CBD-only and THC-containing products.

Because self-reports of CBD use in pregnancy may be drastically underestimated and nonreliable, Dr. Metz writes, development of blood and urine screens to help detect CBD product use “will be helpful in moving the field forward.”

Study senior author David Hammond, PhD, has been a paid expert witness on behalf of public health authorities in response to legal challenges from the cannabis, tobacco, vaping, and food industries. Other authors did not report any potential conflicts. Dr. Metz reports personal fees from Pfizer, and grants from Pfizer for her role as a site principal investigator for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and for her role as a site PI for RSV vaccination in pregnancy study.

Pregnant women in a large North American sample reported nearly double the rate of cannabidiol (CBD) use compared with nonpregnant women, new data published in a research letter in Obstetrics & Gynecology indicates.

Healthcare providers should be aware of the high rate of CBD use in pregnancy, especially as legal use of cannabis is increasing faster than evidence on outcomes for exposed offspring, note the researchers, led by Devika Bhatia, MD, from the Department of Psychiatry, Colorado School of Medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

In an accompanying editorial, Torri D. Metz, MD, MS, deputy editor for obstetrics for Obstetrics & Gynecology, writes that the study “is critically important.” She points out that pregnant individuals may perceive that CBD is a safe drug to use in pregnancy, despite there being essentially no data examining whether or not this is the case.

Large Dataset From United States and Canada

Researchers used data from the International Cannabis Policy Study (2019-2021), a repeated cross-sectional survey of people aged 16-65 years in the United States and Canada. There were 66,457 women in the sample, including 1096 pregnant women.

Particularly concerning, the authors write, is the prenatal use of CBD-only products. Those products are advertised to contain only CBD, rather than tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). They point out CBD-only products are often legal in North America and often marketed as supplements.

The prevalence of CBD-only use in pregnant women in the study was 20.4% compared with 11.3% among nonpregnant women, P < .001. The top reason for use by pregnant women was anxiety (58.4%). Other top reasons included depression (40.3%), posttraumatic stress disorder (32.1%), pain (52.3%), headache (35.6%), and nausea or vomiting (31.9%).

“Nonpregnant women were significantly more likely to report using CBD for pain, sleep, general well-being, and ‘other’ physical or mental health reasons, or to not use CBD for mental health,” the authors write, adding that the reasons for CBD use highlight drivers that may be important to address in treating pregnant patients.

Provider Endorsement in Some Cases

Dr. Metz, associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology with the University of Utah Health in Salt Lake City, says in some cases women may be getting endorsement of CBD use from their provider or at least implied support when CBD is prescribed. In the study, pregnant women had 2.33 times greater adjusted odds of having a CBD prescription than nonpregnant women (95% confidence interval, 1.27-2.88).

She points to another cross-sectional study of more than 10,000 participants using PRAMS (Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System) data that found that “from 2017 to 2019, 63% of pregnant women reported that they were not told to avoid cannabis use in pregnancy, and 8% noted that they were advised to use cannabis by their prenatal care practitioner.”

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends against prescribing cannabis products for pregnant or lactating women.

Studies that have explored THC and its metabolites have shown “a consistent association between cannabis use and decreased fetal growth,” Dr. Metz noted. “There also remain persistent concerns about the long-term neurodevelopmental effects of maternal cannabis use on the fetus and, subsequently, the newborn.”

Limitations of the study include the self-reported responses and participants’ ability to accurately distinguish between CBD-only and THC-containing products.

Because self-reports of CBD use in pregnancy may be drastically underestimated and nonreliable, Dr. Metz writes, development of blood and urine screens to help detect CBD product use “will be helpful in moving the field forward.”

Study senior author David Hammond, PhD, has been a paid expert witness on behalf of public health authorities in response to legal challenges from the cannabis, tobacco, vaping, and food industries. Other authors did not report any potential conflicts. Dr. Metz reports personal fees from Pfizer, and grants from Pfizer for her role as a site principal investigator for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and for her role as a site PI for RSV vaccination in pregnancy study.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Syphilis Treatment Falls Short for Pregnant Patients

Approximately one third of pregnant individuals with syphilis were inadequately treated or not treated for syphilis despite receiving timely prenatal care, based on data from nearly 1500 patients.

Although congenital syphilis is preventable with treatment before or early in pregnancy, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show a doubling of syphilis rates in the United States between 2018 and 2021 wrote Ayzsa Tannis, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and colleagues.

To better understand factors contributing to inadequate syphilis treatment during pregnancy, the researchers examined data from 1476 individuals with syphilis during pregnancy. The study population came from six jurisdictions that participated in the Surveillance for Emerging Threats to Pregnant People and Infants Network, and sources included case investigations, medical records, and links between laboratory data and vital records.

The researchers characterized the status of syphilis during pregnancy as adequate, inadequate, or not treated based on the CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Prenatal care was defined as timely (at least 30 days prior to pregnancy outcome), nontimely (less than 30 days before pregnancy outcome), and no prenatal care. The findings were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Of the 1476 individuals studied, 855 (57.9%) were adequately treated for syphilis and 621 (42.1%) were inadequately or not treated.

Overall, 82% of the study population received timely prenatal care. However, 32.1% of those who received timely prenatal care were inadequately treated, including 14.8% who received no syphilis treatment. Individuals with nontimely or no prenatal care were significantly more likely to receive inadequate or no treatment for syphilis than those who received timely care (risk ratio, 2.50 and 2.73, respectively).

The findings were consistent with previous studies of missed opportunities for prevention and treatment, the researchers noted. Factors behind nontimely treatment (less than 30 days before pregnancy outcome) may include intermittent shortages of benzathine penicillin G, the standard treatment for syphilis, as well as the lack of time and administrative support for clinicians to communicate with patients and health departments, and to expedite treatment, the researchers wrote.

The results were limited by several factors including the use of data from six US jurisdictions that may not generalize to other areas, the variations in reporting years for the different jurisdictions, and variation in mandates for syphilis screening during pregnancy, the researchers noted.

More research is needed to improve syphilis testing itself, and to develop more treatment options, the researchers concluded. Partnerships among public health, patient advocacy groups, prenatal care clinicians, and other clinicians outside the prenatal care setting also are needed for effective intervention in pregnant individuals with syphilis, they said.

The study was carried out as part of the regular work of the CDC, supported by the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement and through contractual mechanisms including the Local Health Department Initiative to Chickasaw Health Consulting. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Approximately one third of pregnant individuals with syphilis were inadequately treated or not treated for syphilis despite receiving timely prenatal care, based on data from nearly 1500 patients.

Although congenital syphilis is preventable with treatment before or early in pregnancy, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show a doubling of syphilis rates in the United States between 2018 and 2021 wrote Ayzsa Tannis, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and colleagues.

To better understand factors contributing to inadequate syphilis treatment during pregnancy, the researchers examined data from 1476 individuals with syphilis during pregnancy. The study population came from six jurisdictions that participated in the Surveillance for Emerging Threats to Pregnant People and Infants Network, and sources included case investigations, medical records, and links between laboratory data and vital records.

The researchers characterized the status of syphilis during pregnancy as adequate, inadequate, or not treated based on the CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Prenatal care was defined as timely (at least 30 days prior to pregnancy outcome), nontimely (less than 30 days before pregnancy outcome), and no prenatal care. The findings were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Of the 1476 individuals studied, 855 (57.9%) were adequately treated for syphilis and 621 (42.1%) were inadequately or not treated.

Overall, 82% of the study population received timely prenatal care. However, 32.1% of those who received timely prenatal care were inadequately treated, including 14.8% who received no syphilis treatment. Individuals with nontimely or no prenatal care were significantly more likely to receive inadequate or no treatment for syphilis than those who received timely care (risk ratio, 2.50 and 2.73, respectively).

The findings were consistent with previous studies of missed opportunities for prevention and treatment, the researchers noted. Factors behind nontimely treatment (less than 30 days before pregnancy outcome) may include intermittent shortages of benzathine penicillin G, the standard treatment for syphilis, as well as the lack of time and administrative support for clinicians to communicate with patients and health departments, and to expedite treatment, the researchers wrote.

The results were limited by several factors including the use of data from six US jurisdictions that may not generalize to other areas, the variations in reporting years for the different jurisdictions, and variation in mandates for syphilis screening during pregnancy, the researchers noted.

More research is needed to improve syphilis testing itself, and to develop more treatment options, the researchers concluded. Partnerships among public health, patient advocacy groups, prenatal care clinicians, and other clinicians outside the prenatal care setting also are needed for effective intervention in pregnant individuals with syphilis, they said.

The study was carried out as part of the regular work of the CDC, supported by the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement and through contractual mechanisms including the Local Health Department Initiative to Chickasaw Health Consulting. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Approximately one third of pregnant individuals with syphilis were inadequately treated or not treated for syphilis despite receiving timely prenatal care, based on data from nearly 1500 patients.

Although congenital syphilis is preventable with treatment before or early in pregnancy, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show a doubling of syphilis rates in the United States between 2018 and 2021 wrote Ayzsa Tannis, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and colleagues.

To better understand factors contributing to inadequate syphilis treatment during pregnancy, the researchers examined data from 1476 individuals with syphilis during pregnancy. The study population came from six jurisdictions that participated in the Surveillance for Emerging Threats to Pregnant People and Infants Network, and sources included case investigations, medical records, and links between laboratory data and vital records.

The researchers characterized the status of syphilis during pregnancy as adequate, inadequate, or not treated based on the CDC’s Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. Prenatal care was defined as timely (at least 30 days prior to pregnancy outcome), nontimely (less than 30 days before pregnancy outcome), and no prenatal care. The findings were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Of the 1476 individuals studied, 855 (57.9%) were adequately treated for syphilis and 621 (42.1%) were inadequately or not treated.

Overall, 82% of the study population received timely prenatal care. However, 32.1% of those who received timely prenatal care were inadequately treated, including 14.8% who received no syphilis treatment. Individuals with nontimely or no prenatal care were significantly more likely to receive inadequate or no treatment for syphilis than those who received timely care (risk ratio, 2.50 and 2.73, respectively).

The findings were consistent with previous studies of missed opportunities for prevention and treatment, the researchers noted. Factors behind nontimely treatment (less than 30 days before pregnancy outcome) may include intermittent shortages of benzathine penicillin G, the standard treatment for syphilis, as well as the lack of time and administrative support for clinicians to communicate with patients and health departments, and to expedite treatment, the researchers wrote.

The results were limited by several factors including the use of data from six US jurisdictions that may not generalize to other areas, the variations in reporting years for the different jurisdictions, and variation in mandates for syphilis screening during pregnancy, the researchers noted.

More research is needed to improve syphilis testing itself, and to develop more treatment options, the researchers concluded. Partnerships among public health, patient advocacy groups, prenatal care clinicians, and other clinicians outside the prenatal care setting also are needed for effective intervention in pregnant individuals with syphilis, they said.

The study was carried out as part of the regular work of the CDC, supported by the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement and through contractual mechanisms including the Local Health Department Initiative to Chickasaw Health Consulting. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

New Research Dissects Transgenerational Obesity and Diabetes

FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA — Nearly 30 years ago, in a 1995 paper, the British physician-epidemiologist David Barker, MD, PhD, wrote about his fetal origins hypothesis — the idea that programs to address fetal undernutrition and low birth weight produced later coronary heart disease (BMJ 1995;311:171-4).

His hypothesis and subsequent research led to the concept of adult diseases of fetal origins, which today extends beyond low birth weight and implicates the in utero environment as a significant determinant of risk for adverse childhood and adult metabolic outcomes and for major chronic diseases, including diabetes and obesity. Studies have shown that the offspring of pregnant mothers with diabetes have a higher risk of developing obesity and diabetes themselves.

“It’s a whole discipline [of research],” E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM), said in an interview. “But what we’ve never quite understood is the ‘how’ and ‘why’? What are the mechanisms driving the fetal origins of such adverse outcomes in offspring?

At the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG), investigators described studies underway that are digging deeper into the associations between the intrauterine milieu and longer-term offspring health — and that are searching for biological and molecular processes that may be involved.

The studies are like “branches of the Barker hypothesis,” said Dr. Reece, former dean of UMSOM and current director of the UMSOM Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation, who co-organized the DPSG meeting. “They’re taking the hypothesis and dissecting it by asking, for instance, it is possible that transgenerational obesity may align with the Barker hypothesis? Is it possible that it involves epigenetics regulation? Could we find biomarkers?”

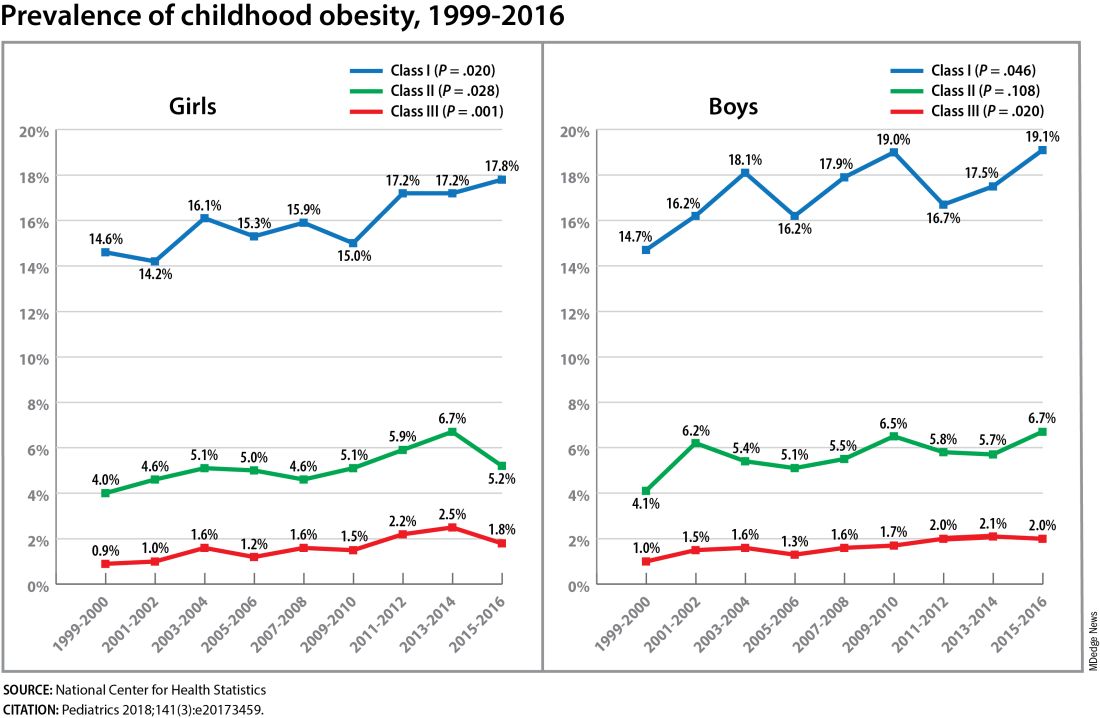

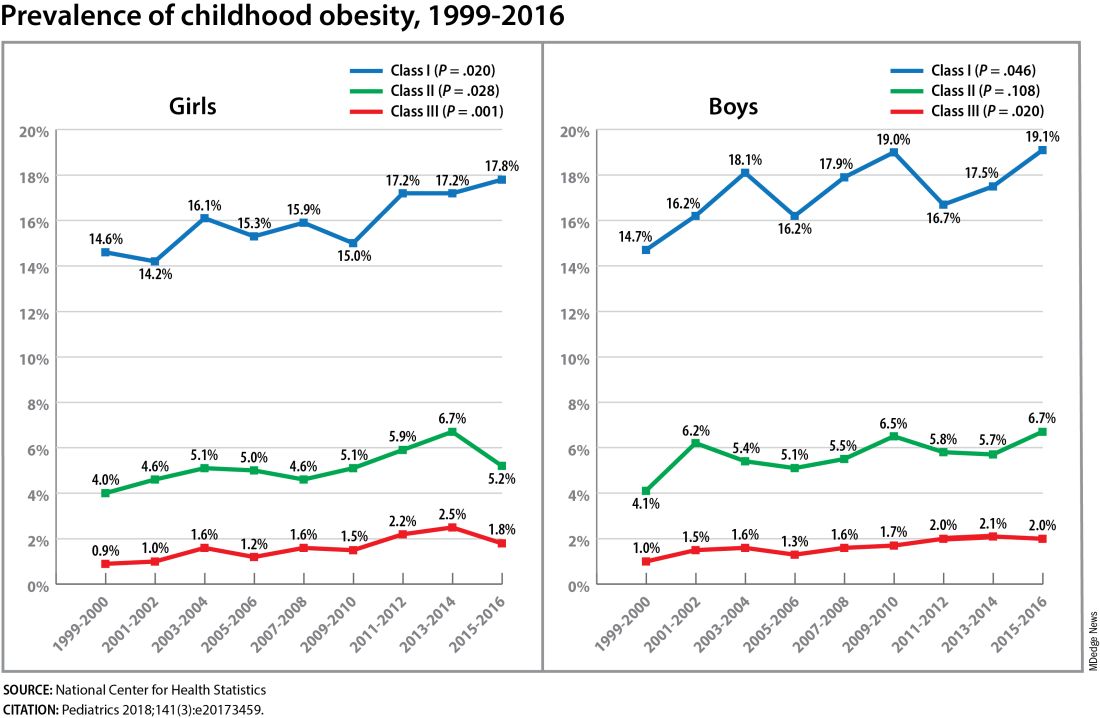

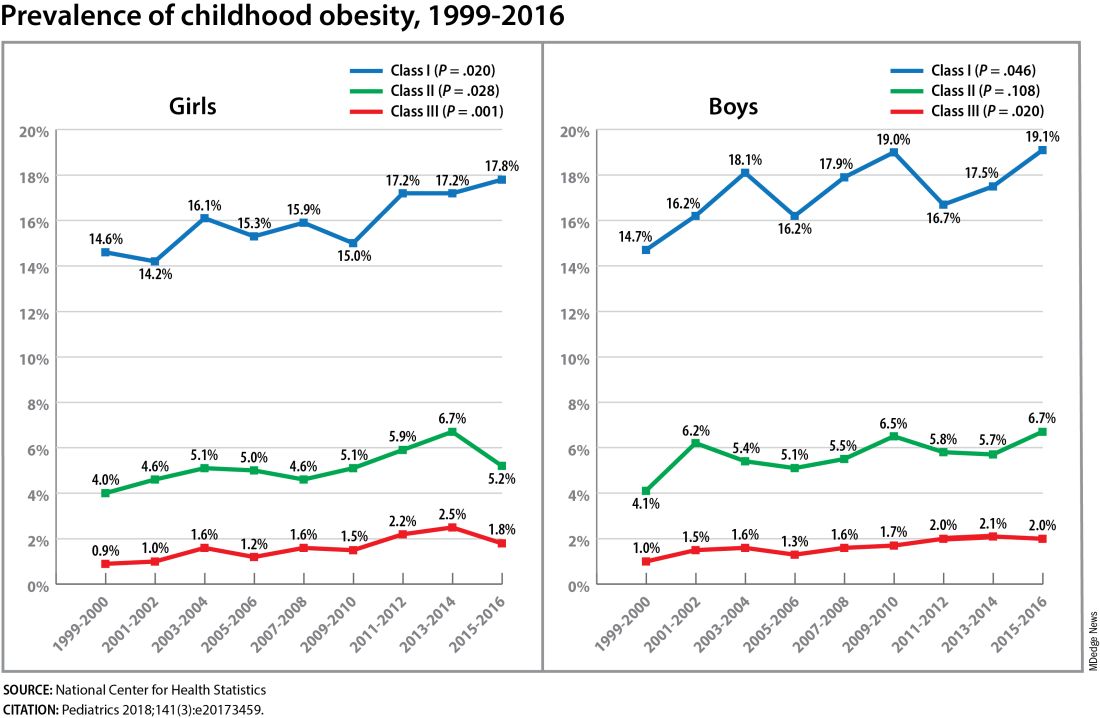

The need for a better understanding of the fetal origins framework — and its subsequent transgenerational impact — is urgent. From 2000 to 2018, the prevalence of childhood obesity increased from 14.7% to 19.2% (a 31% increase) and the prevalence of severe childhood obesity rose from 3.9% to 6.1% (a 56% increase), according to data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Obes Facts. 2022;15[4]:560-9).

Children aged 2-5 years have had an especially sharp increase in obesity (Pediatrics 2018;141[3]:e20173459), Christine Wey Hockett, PhD, of the University of South Dakota School of Medicine, said at the DPSG meeting (Figure 1).

Also notable, she said, is that one-quarter of today’s pediatric diabetes cases are type 2 diabetes, which “is significant as there is a higher prevalence of early complications and comorbidities in youth with type 2 diabetes compared to type 1 diabetes.”

Moreover, recent projections estimate that 57% of today’s children will be obese at 35 years of age (N Engl J Med. 2017;377[22]:2145-53) and that 45% will have diabetes or prediabetes by 2030 (Popul Health Manag. 2017;20[1]:6-12), said Dr. Hockett, assistant professor in the university’s department of pediatrics. An investigator of the Exploring Perinatal Outcomes Among Children (EPOCH) study, which looked at gestational diabetes (GDM) and offspring cardiometabolic risks, she said more chronic disease “at increasingly younger ages [points toward] prebirth influences.”

She noted that there are critical periods postnatally — such as infancy and puberty — that can “impact or further shift the trajectory of chronic disease.” The developmental origins theory posits that life events and biological and environmental processes during the lifespan can modify the effects of intrauterine exposures.

The transgenerational implications “are clear,” she said. “As the number of reproductive-aged individuals with chronic diseases rises, the number of exposed offspring also rises ... It leads to a vicious cycle.”

Deeper Dives Into Associations, Potential Mechanisms

The EPOCH prospective cohort study with which Dr. Hockett was involved gave her a front-seat view of the transgenerational adverse effects of in utero exposure to hyperglycemia. The study recruited ethnically diverse maternal/child dyads from the Kaiser Permanente of Colorado perinatal database from 1992 to 2002 and assessed 418 offspring at two points — a mean age of 10.5 years and 16.5 years — for fasting blood glucose, adiposity, and diet and physical activity. The second visit also involved an oral glucose tolerance test.

The 77 offspring who had been exposed in utero to GDM had a homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) that was 18% higher, a 19% lower Matsuda index, and a 9% greater HOMA of β-cell function (HOMA-β) than the 341 offspring whose mothers did not have diabetes. Each 5-kg/m2 increase in prepregnancy body mass index predicted increased insulin resistance, but there was no combined effect of both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero.

Exposed offspring had a higher BMI and increased adiposity, but when BMI was controlled for in the analysis of metabolic outcomes, maternal diabetes was still associated with 12% higher HOMA-IR and a 17% lower Matsuda index. “So [the metabolic outcomes] are a direct effect of maternal diabetes,” Dr. Hockett said at the DPSG meeting, noting the fetal overnutrition hypothesis in which maternal glucose, but not maternal insulin, freely passes through the placenta, promoting growth and adiposity in the fetus.

[The EPOCH results on metabolic outcomes and offspring adiposity were published in 2017 and 2019, respectively (Diabet Med. 2017;34:1392-9; Diabetologia. 2019;62:2017-24). In 2020, EPOCH researchers reported sex-specific effects on cardiovascular outcomes, with GDM exposure associated with higher total and LDL cholesterol in girls and higher systolic blood pressure in boys (Pediatr Obes. 2020;15[5]:e12611).]

Now, a new longitudinal cohort study underway in Phoenix, is taking a deeper dive, trying to pinpoint what exactly influences childhood obesity and metabolic risk by following Hispanic and American Indian maternal/child dyads from pregnancy until 18 years postpartum. Researchers are looking not only at associations between maternal risk factors (pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and diabetes in pregnancy) and offspring BMI, adiposity, and growth patterns, but also how various factors during pregnancy — clinical, genetic, lifestyle, biochemical — ”may mediate the associations,” said lead investigator Madhumita Sinha, MD.

“We need a better understanding at the molecular level of the biological processes that lead to obesity in children and that cause metabolic dysfunction,” said Dr. Sinha, who heads the Diabetes Epidemiology and Clinical Research Section of the of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) branch in Phoenix.

The populations being enrolled in the ETCHED study (for Early Tracking of Childhood Health Determinants) are at especially high risk of childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Research conducted decades ago by the NIDDK in Phoenix showed that approximately 50% of Pima Indian children from diabetic pregnancies develop type 2 diabetes by age 25 (N Engl J Med. 1983;308:242-5). Years later, to tease out possible genetic factors, researchers compared siblings born before and after their mother was found to have type 2 diabetes, and found significantly higher rates of diabetes in those born after the mother’s diagnosis, affirming the role of in utero toxicity (Diabetes 2000;49:2208-11).

In the new study, the researchers will look at adipokines and inflammatory biomarkers in the mothers and offspring in addition to traditional anthropometric and glycemic measures. They’ll analyze placental tissue, breast milk, and the gut microbiome longitudinally, and they’ll lean heavily on genomics/epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. “There’s potential,” Dr. Sinha said, “to develop a more accurate predictive and prognostic model of childhood obesity.”

The researchers also will study the role of family, socioeconomics, and environmental factors in influencing child growth patterns and they’ll look at neurodevelopment in infancy and childhood. As of October 2023, almost 80 pregnant women, most with obesity and almost one-third with type 2 diabetes, had enrolled in the study. Over the next several years, the study aims to enroll 750 dyads.

The Timing of In Utero Exposure

Shelley Ehrlich, MD, ScD, MPH, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, is aiming, meanwhile, to learn how the timing of in utero exposure to hyperglycemia predicts specific metabolic and cardiovascular morbidities in the adult offspring of diabetic mothers.

“While we know that exposure to maternal diabetes, regardless of type, increases the risk of obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, renal compromise, and cardiovascular disease in the offspring, there is little known about the level and timing of hyperglycemic exposure during fetal development that triggers these adverse outcomes,” said Dr. Ehrlich. A goal, she said, is to identify gestational profiles that predict phenotypes of offspring at risk for morbidity in later life.

She and other investigators with the TEAM (Transgenerational Effect on Adult Morbidity) study have recruited over 170 offspring of mothers who participated in the Diabetes in Pregnancy Program Project Grant (PPG) at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center from 1978 to 1995 — a landmark study that demonstrated the effect of strict glucose control in reducing major congenital malformations.

The women in the PPG study had frequent glucose monitoring (up to 6-8 times a day) throughout their pregnancies, and now, their recruited offspring, who are up to 43 years of age, are being assessed for obesity, diabetes/metabolic health, cardiovascular disease/cardiac and peripheral vascular structure and function, and other outcomes including those that may be amenable to secondary prevention (J Diabetes Res. Nov 1;2021:6590431).

Preliminary findings from over 170 offspring recruited between 2017 and 2022 suggest that in utero exposure to dysglycemia (as measured by standard deviations of glycohemoglobin) in the third trimester appears to increase the risk of morbid obesity in adulthood, while exposure to dysglycemia in the first trimester increases the risk of impaired glucose tolerance. The risk of B-cell dysfunction, meanwhile, appears to be linked to dysglycemia in the first and third trimesters — particularly the first — Dr. Ehrlich reported.

Cognitive outcomes in offspring have also been assessed and here it appears that dysglycemia in the third trimester is linked to worse scores on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI-II), said Katherine Bowers, PhD, MPH, a TEAM study coinvestigator, also of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“We’ve already observed [an association between] diabetes in pregnancy and cognition in early childhood and through adolescence, but [the question has been] does this association persist into adulthood?” she said.

Preliminary analyses of 104 offspring show no statistically significant associations between maternal dysglycemia in the first or second trimesters and offspring cognition, but “consistent inverse associations between maternal glycohemoglobin in the third trimester across two [WASI-II] subscales and composite measures of cognition,” Dr. Bowers said.

Their analysis adjusted for a variety of factors, including maternal age, prepregnancy and first trimester BMI, race, family history of diabetes, and diabetes severity/macrovascular complications.

Back In The Laboratory

At the other end of the research spectrum, basic research scientists are also investigating the mechanisms and sequelae of in utero hyperglycemia and other injuries, including congenital malformations, placental adaptive responses and fetal programming. Researchers are asking, for instance, what does placental metabolic reprogramming entail? What role do placental extracellular vesicles play in GDM? Can we alter the in utero environment and thus improve the short and long-term fetal/infant outcomes?

Animal research done at the UMSOM Center for Birth Defects Research, led by Dr. Reece and Peixin Yang, PhD, suggests that “a good portion of in utero injury is due to epigenetics,” Dr. Reece said in the interview. “We’ve shown that under conditions of hyperglycemia, for example, genetic regulation and genetic function can be altered.”

Through in vivo research, they have also shown that antioxidants or membrane stabilizers such as arachidonic acid or myo-inositol, or experimental inhibitors to certain pro-apoptotic intermediates, can individually or collectively result in reduced malformations. “It is highly likely that understanding the biological impact of various altered in utero environments, and then modifying or reversing those environments, will result in short and long-term outcome improvements similar to those shown with congenital malformations,” Dr. Reece said.

FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA — Nearly 30 years ago, in a 1995 paper, the British physician-epidemiologist David Barker, MD, PhD, wrote about his fetal origins hypothesis — the idea that programs to address fetal undernutrition and low birth weight produced later coronary heart disease (BMJ 1995;311:171-4).

His hypothesis and subsequent research led to the concept of adult diseases of fetal origins, which today extends beyond low birth weight and implicates the in utero environment as a significant determinant of risk for adverse childhood and adult metabolic outcomes and for major chronic diseases, including diabetes and obesity. Studies have shown that the offspring of pregnant mothers with diabetes have a higher risk of developing obesity and diabetes themselves.

“It’s a whole discipline [of research],” E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM), said in an interview. “But what we’ve never quite understood is the ‘how’ and ‘why’? What are the mechanisms driving the fetal origins of such adverse outcomes in offspring?

At the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG), investigators described studies underway that are digging deeper into the associations between the intrauterine milieu and longer-term offspring health — and that are searching for biological and molecular processes that may be involved.

The studies are like “branches of the Barker hypothesis,” said Dr. Reece, former dean of UMSOM and current director of the UMSOM Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation, who co-organized the DPSG meeting. “They’re taking the hypothesis and dissecting it by asking, for instance, it is possible that transgenerational obesity may align with the Barker hypothesis? Is it possible that it involves epigenetics regulation? Could we find biomarkers?”

The need for a better understanding of the fetal origins framework — and its subsequent transgenerational impact — is urgent. From 2000 to 2018, the prevalence of childhood obesity increased from 14.7% to 19.2% (a 31% increase) and the prevalence of severe childhood obesity rose from 3.9% to 6.1% (a 56% increase), according to data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Obes Facts. 2022;15[4]:560-9).

Children aged 2-5 years have had an especially sharp increase in obesity (Pediatrics 2018;141[3]:e20173459), Christine Wey Hockett, PhD, of the University of South Dakota School of Medicine, said at the DPSG meeting (Figure 1).

Also notable, she said, is that one-quarter of today’s pediatric diabetes cases are type 2 diabetes, which “is significant as there is a higher prevalence of early complications and comorbidities in youth with type 2 diabetes compared to type 1 diabetes.”

Moreover, recent projections estimate that 57% of today’s children will be obese at 35 years of age (N Engl J Med. 2017;377[22]:2145-53) and that 45% will have diabetes or prediabetes by 2030 (Popul Health Manag. 2017;20[1]:6-12), said Dr. Hockett, assistant professor in the university’s department of pediatrics. An investigator of the Exploring Perinatal Outcomes Among Children (EPOCH) study, which looked at gestational diabetes (GDM) and offspring cardiometabolic risks, she said more chronic disease “at increasingly younger ages [points toward] prebirth influences.”

She noted that there are critical periods postnatally — such as infancy and puberty — that can “impact or further shift the trajectory of chronic disease.” The developmental origins theory posits that life events and biological and environmental processes during the lifespan can modify the effects of intrauterine exposures.

The transgenerational implications “are clear,” she said. “As the number of reproductive-aged individuals with chronic diseases rises, the number of exposed offspring also rises ... It leads to a vicious cycle.”

Deeper Dives Into Associations, Potential Mechanisms

The EPOCH prospective cohort study with which Dr. Hockett was involved gave her a front-seat view of the transgenerational adverse effects of in utero exposure to hyperglycemia. The study recruited ethnically diverse maternal/child dyads from the Kaiser Permanente of Colorado perinatal database from 1992 to 2002 and assessed 418 offspring at two points — a mean age of 10.5 years and 16.5 years — for fasting blood glucose, adiposity, and diet and physical activity. The second visit also involved an oral glucose tolerance test.

The 77 offspring who had been exposed in utero to GDM had a homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) that was 18% higher, a 19% lower Matsuda index, and a 9% greater HOMA of β-cell function (HOMA-β) than the 341 offspring whose mothers did not have diabetes. Each 5-kg/m2 increase in prepregnancy body mass index predicted increased insulin resistance, but there was no combined effect of both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero.

Exposed offspring had a higher BMI and increased adiposity, but when BMI was controlled for in the analysis of metabolic outcomes, maternal diabetes was still associated with 12% higher HOMA-IR and a 17% lower Matsuda index. “So [the metabolic outcomes] are a direct effect of maternal diabetes,” Dr. Hockett said at the DPSG meeting, noting the fetal overnutrition hypothesis in which maternal glucose, but not maternal insulin, freely passes through the placenta, promoting growth and adiposity in the fetus.

[The EPOCH results on metabolic outcomes and offspring adiposity were published in 2017 and 2019, respectively (Diabet Med. 2017;34:1392-9; Diabetologia. 2019;62:2017-24). In 2020, EPOCH researchers reported sex-specific effects on cardiovascular outcomes, with GDM exposure associated with higher total and LDL cholesterol in girls and higher systolic blood pressure in boys (Pediatr Obes. 2020;15[5]:e12611).]

Now, a new longitudinal cohort study underway in Phoenix, is taking a deeper dive, trying to pinpoint what exactly influences childhood obesity and metabolic risk by following Hispanic and American Indian maternal/child dyads from pregnancy until 18 years postpartum. Researchers are looking not only at associations between maternal risk factors (pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and diabetes in pregnancy) and offspring BMI, adiposity, and growth patterns, but also how various factors during pregnancy — clinical, genetic, lifestyle, biochemical — ”may mediate the associations,” said lead investigator Madhumita Sinha, MD.

“We need a better understanding at the molecular level of the biological processes that lead to obesity in children and that cause metabolic dysfunction,” said Dr. Sinha, who heads the Diabetes Epidemiology and Clinical Research Section of the of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) branch in Phoenix.

The populations being enrolled in the ETCHED study (for Early Tracking of Childhood Health Determinants) are at especially high risk of childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Research conducted decades ago by the NIDDK in Phoenix showed that approximately 50% of Pima Indian children from diabetic pregnancies develop type 2 diabetes by age 25 (N Engl J Med. 1983;308:242-5). Years later, to tease out possible genetic factors, researchers compared siblings born before and after their mother was found to have type 2 diabetes, and found significantly higher rates of diabetes in those born after the mother’s diagnosis, affirming the role of in utero toxicity (Diabetes 2000;49:2208-11).

In the new study, the researchers will look at adipokines and inflammatory biomarkers in the mothers and offspring in addition to traditional anthropometric and glycemic measures. They’ll analyze placental tissue, breast milk, and the gut microbiome longitudinally, and they’ll lean heavily on genomics/epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. “There’s potential,” Dr. Sinha said, “to develop a more accurate predictive and prognostic model of childhood obesity.”

The researchers also will study the role of family, socioeconomics, and environmental factors in influencing child growth patterns and they’ll look at neurodevelopment in infancy and childhood. As of October 2023, almost 80 pregnant women, most with obesity and almost one-third with type 2 diabetes, had enrolled in the study. Over the next several years, the study aims to enroll 750 dyads.

The Timing of In Utero Exposure

Shelley Ehrlich, MD, ScD, MPH, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, is aiming, meanwhile, to learn how the timing of in utero exposure to hyperglycemia predicts specific metabolic and cardiovascular morbidities in the adult offspring of diabetic mothers.

“While we know that exposure to maternal diabetes, regardless of type, increases the risk of obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, renal compromise, and cardiovascular disease in the offspring, there is little known about the level and timing of hyperglycemic exposure during fetal development that triggers these adverse outcomes,” said Dr. Ehrlich. A goal, she said, is to identify gestational profiles that predict phenotypes of offspring at risk for morbidity in later life.

She and other investigators with the TEAM (Transgenerational Effect on Adult Morbidity) study have recruited over 170 offspring of mothers who participated in the Diabetes in Pregnancy Program Project Grant (PPG) at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center from 1978 to 1995 — a landmark study that demonstrated the effect of strict glucose control in reducing major congenital malformations.

The women in the PPG study had frequent glucose monitoring (up to 6-8 times a day) throughout their pregnancies, and now, their recruited offspring, who are up to 43 years of age, are being assessed for obesity, diabetes/metabolic health, cardiovascular disease/cardiac and peripheral vascular structure and function, and other outcomes including those that may be amenable to secondary prevention (J Diabetes Res. Nov 1;2021:6590431).

Preliminary findings from over 170 offspring recruited between 2017 and 2022 suggest that in utero exposure to dysglycemia (as measured by standard deviations of glycohemoglobin) in the third trimester appears to increase the risk of morbid obesity in adulthood, while exposure to dysglycemia in the first trimester increases the risk of impaired glucose tolerance. The risk of B-cell dysfunction, meanwhile, appears to be linked to dysglycemia in the first and third trimesters — particularly the first — Dr. Ehrlich reported.

Cognitive outcomes in offspring have also been assessed and here it appears that dysglycemia in the third trimester is linked to worse scores on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI-II), said Katherine Bowers, PhD, MPH, a TEAM study coinvestigator, also of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“We’ve already observed [an association between] diabetes in pregnancy and cognition in early childhood and through adolescence, but [the question has been] does this association persist into adulthood?” she said.

Preliminary analyses of 104 offspring show no statistically significant associations between maternal dysglycemia in the first or second trimesters and offspring cognition, but “consistent inverse associations between maternal glycohemoglobin in the third trimester across two [WASI-II] subscales and composite measures of cognition,” Dr. Bowers said.

Their analysis adjusted for a variety of factors, including maternal age, prepregnancy and first trimester BMI, race, family history of diabetes, and diabetes severity/macrovascular complications.

Back In The Laboratory

At the other end of the research spectrum, basic research scientists are also investigating the mechanisms and sequelae of in utero hyperglycemia and other injuries, including congenital malformations, placental adaptive responses and fetal programming. Researchers are asking, for instance, what does placental metabolic reprogramming entail? What role do placental extracellular vesicles play in GDM? Can we alter the in utero environment and thus improve the short and long-term fetal/infant outcomes?

Animal research done at the UMSOM Center for Birth Defects Research, led by Dr. Reece and Peixin Yang, PhD, suggests that “a good portion of in utero injury is due to epigenetics,” Dr. Reece said in the interview. “We’ve shown that under conditions of hyperglycemia, for example, genetic regulation and genetic function can be altered.”

Through in vivo research, they have also shown that antioxidants or membrane stabilizers such as arachidonic acid or myo-inositol, or experimental inhibitors to certain pro-apoptotic intermediates, can individually or collectively result in reduced malformations. “It is highly likely that understanding the biological impact of various altered in utero environments, and then modifying or reversing those environments, will result in short and long-term outcome improvements similar to those shown with congenital malformations,” Dr. Reece said.

FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA — Nearly 30 years ago, in a 1995 paper, the British physician-epidemiologist David Barker, MD, PhD, wrote about his fetal origins hypothesis — the idea that programs to address fetal undernutrition and low birth weight produced later coronary heart disease (BMJ 1995;311:171-4).

His hypothesis and subsequent research led to the concept of adult diseases of fetal origins, which today extends beyond low birth weight and implicates the in utero environment as a significant determinant of risk for adverse childhood and adult metabolic outcomes and for major chronic diseases, including diabetes and obesity. Studies have shown that the offspring of pregnant mothers with diabetes have a higher risk of developing obesity and diabetes themselves.

“It’s a whole discipline [of research],” E. Albert Reece, MD, PhD, MBA, of the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM), said in an interview. “But what we’ve never quite understood is the ‘how’ and ‘why’? What are the mechanisms driving the fetal origins of such adverse outcomes in offspring?

At the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America (DPSG), investigators described studies underway that are digging deeper into the associations between the intrauterine milieu and longer-term offspring health — and that are searching for biological and molecular processes that may be involved.

The studies are like “branches of the Barker hypothesis,” said Dr. Reece, former dean of UMSOM and current director of the UMSOM Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation, who co-organized the DPSG meeting. “They’re taking the hypothesis and dissecting it by asking, for instance, it is possible that transgenerational obesity may align with the Barker hypothesis? Is it possible that it involves epigenetics regulation? Could we find biomarkers?”

The need for a better understanding of the fetal origins framework — and its subsequent transgenerational impact — is urgent. From 2000 to 2018, the prevalence of childhood obesity increased from 14.7% to 19.2% (a 31% increase) and the prevalence of severe childhood obesity rose from 3.9% to 6.1% (a 56% increase), according to data from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Obes Facts. 2022;15[4]:560-9).

Children aged 2-5 years have had an especially sharp increase in obesity (Pediatrics 2018;141[3]:e20173459), Christine Wey Hockett, PhD, of the University of South Dakota School of Medicine, said at the DPSG meeting (Figure 1).

Also notable, she said, is that one-quarter of today’s pediatric diabetes cases are type 2 diabetes, which “is significant as there is a higher prevalence of early complications and comorbidities in youth with type 2 diabetes compared to type 1 diabetes.”

Moreover, recent projections estimate that 57% of today’s children will be obese at 35 years of age (N Engl J Med. 2017;377[22]:2145-53) and that 45% will have diabetes or prediabetes by 2030 (Popul Health Manag. 2017;20[1]:6-12), said Dr. Hockett, assistant professor in the university’s department of pediatrics. An investigator of the Exploring Perinatal Outcomes Among Children (EPOCH) study, which looked at gestational diabetes (GDM) and offspring cardiometabolic risks, she said more chronic disease “at increasingly younger ages [points toward] prebirth influences.”

She noted that there are critical periods postnatally — such as infancy and puberty — that can “impact or further shift the trajectory of chronic disease.” The developmental origins theory posits that life events and biological and environmental processes during the lifespan can modify the effects of intrauterine exposures.

The transgenerational implications “are clear,” she said. “As the number of reproductive-aged individuals with chronic diseases rises, the number of exposed offspring also rises ... It leads to a vicious cycle.”

Deeper Dives Into Associations, Potential Mechanisms

The EPOCH prospective cohort study with which Dr. Hockett was involved gave her a front-seat view of the transgenerational adverse effects of in utero exposure to hyperglycemia. The study recruited ethnically diverse maternal/child dyads from the Kaiser Permanente of Colorado perinatal database from 1992 to 2002 and assessed 418 offspring at two points — a mean age of 10.5 years and 16.5 years — for fasting blood glucose, adiposity, and diet and physical activity. The second visit also involved an oral glucose tolerance test.

The 77 offspring who had been exposed in utero to GDM had a homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) that was 18% higher, a 19% lower Matsuda index, and a 9% greater HOMA of β-cell function (HOMA-β) than the 341 offspring whose mothers did not have diabetes. Each 5-kg/m2 increase in prepregnancy body mass index predicted increased insulin resistance, but there was no combined effect of both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero.

Exposed offspring had a higher BMI and increased adiposity, but when BMI was controlled for in the analysis of metabolic outcomes, maternal diabetes was still associated with 12% higher HOMA-IR and a 17% lower Matsuda index. “So [the metabolic outcomes] are a direct effect of maternal diabetes,” Dr. Hockett said at the DPSG meeting, noting the fetal overnutrition hypothesis in which maternal glucose, but not maternal insulin, freely passes through the placenta, promoting growth and adiposity in the fetus.

[The EPOCH results on metabolic outcomes and offspring adiposity were published in 2017 and 2019, respectively (Diabet Med. 2017;34:1392-9; Diabetologia. 2019;62:2017-24). In 2020, EPOCH researchers reported sex-specific effects on cardiovascular outcomes, with GDM exposure associated with higher total and LDL cholesterol in girls and higher systolic blood pressure in boys (Pediatr Obes. 2020;15[5]:e12611).]

Now, a new longitudinal cohort study underway in Phoenix, is taking a deeper dive, trying to pinpoint what exactly influences childhood obesity and metabolic risk by following Hispanic and American Indian maternal/child dyads from pregnancy until 18 years postpartum. Researchers are looking not only at associations between maternal risk factors (pregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, and diabetes in pregnancy) and offspring BMI, adiposity, and growth patterns, but also how various factors during pregnancy — clinical, genetic, lifestyle, biochemical — ”may mediate the associations,” said lead investigator Madhumita Sinha, MD.

“We need a better understanding at the molecular level of the biological processes that lead to obesity in children and that cause metabolic dysfunction,” said Dr. Sinha, who heads the Diabetes Epidemiology and Clinical Research Section of the of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) branch in Phoenix.

The populations being enrolled in the ETCHED study (for Early Tracking of Childhood Health Determinants) are at especially high risk of childhood obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Research conducted decades ago by the NIDDK in Phoenix showed that approximately 50% of Pima Indian children from diabetic pregnancies develop type 2 diabetes by age 25 (N Engl J Med. 1983;308:242-5). Years later, to tease out possible genetic factors, researchers compared siblings born before and after their mother was found to have type 2 diabetes, and found significantly higher rates of diabetes in those born after the mother’s diagnosis, affirming the role of in utero toxicity (Diabetes 2000;49:2208-11).

In the new study, the researchers will look at adipokines and inflammatory biomarkers in the mothers and offspring in addition to traditional anthropometric and glycemic measures. They’ll analyze placental tissue, breast milk, and the gut microbiome longitudinally, and they’ll lean heavily on genomics/epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. “There’s potential,” Dr. Sinha said, “to develop a more accurate predictive and prognostic model of childhood obesity.”

The researchers also will study the role of family, socioeconomics, and environmental factors in influencing child growth patterns and they’ll look at neurodevelopment in infancy and childhood. As of October 2023, almost 80 pregnant women, most with obesity and almost one-third with type 2 diabetes, had enrolled in the study. Over the next several years, the study aims to enroll 750 dyads.

The Timing of In Utero Exposure

Shelley Ehrlich, MD, ScD, MPH, of the University of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, is aiming, meanwhile, to learn how the timing of in utero exposure to hyperglycemia predicts specific metabolic and cardiovascular morbidities in the adult offspring of diabetic mothers.

“While we know that exposure to maternal diabetes, regardless of type, increases the risk of obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, renal compromise, and cardiovascular disease in the offspring, there is little known about the level and timing of hyperglycemic exposure during fetal development that triggers these adverse outcomes,” said Dr. Ehrlich. A goal, she said, is to identify gestational profiles that predict phenotypes of offspring at risk for morbidity in later life.

She and other investigators with the TEAM (Transgenerational Effect on Adult Morbidity) study have recruited over 170 offspring of mothers who participated in the Diabetes in Pregnancy Program Project Grant (PPG) at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center from 1978 to 1995 — a landmark study that demonstrated the effect of strict glucose control in reducing major congenital malformations.

The women in the PPG study had frequent glucose monitoring (up to 6-8 times a day) throughout their pregnancies, and now, their recruited offspring, who are up to 43 years of age, are being assessed for obesity, diabetes/metabolic health, cardiovascular disease/cardiac and peripheral vascular structure and function, and other outcomes including those that may be amenable to secondary prevention (J Diabetes Res. Nov 1;2021:6590431).

Preliminary findings from over 170 offspring recruited between 2017 and 2022 suggest that in utero exposure to dysglycemia (as measured by standard deviations of glycohemoglobin) in the third trimester appears to increase the risk of morbid obesity in adulthood, while exposure to dysglycemia in the first trimester increases the risk of impaired glucose tolerance. The risk of B-cell dysfunction, meanwhile, appears to be linked to dysglycemia in the first and third trimesters — particularly the first — Dr. Ehrlich reported.

Cognitive outcomes in offspring have also been assessed and here it appears that dysglycemia in the third trimester is linked to worse scores on the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI-II), said Katherine Bowers, PhD, MPH, a TEAM study coinvestigator, also of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

“We’ve already observed [an association between] diabetes in pregnancy and cognition in early childhood and through adolescence, but [the question has been] does this association persist into adulthood?” she said.

Preliminary analyses of 104 offspring show no statistically significant associations between maternal dysglycemia in the first or second trimesters and offspring cognition, but “consistent inverse associations between maternal glycohemoglobin in the third trimester across two [WASI-II] subscales and composite measures of cognition,” Dr. Bowers said.

Their analysis adjusted for a variety of factors, including maternal age, prepregnancy and first trimester BMI, race, family history of diabetes, and diabetes severity/macrovascular complications.

Back In The Laboratory

At the other end of the research spectrum, basic research scientists are also investigating the mechanisms and sequelae of in utero hyperglycemia and other injuries, including congenital malformations, placental adaptive responses and fetal programming. Researchers are asking, for instance, what does placental metabolic reprogramming entail? What role do placental extracellular vesicles play in GDM? Can we alter the in utero environment and thus improve the short and long-term fetal/infant outcomes?

Animal research done at the UMSOM Center for Birth Defects Research, led by Dr. Reece and Peixin Yang, PhD, suggests that “a good portion of in utero injury is due to epigenetics,” Dr. Reece said in the interview. “We’ve shown that under conditions of hyperglycemia, for example, genetic regulation and genetic function can be altered.”

Through in vivo research, they have also shown that antioxidants or membrane stabilizers such as arachidonic acid or myo-inositol, or experimental inhibitors to certain pro-apoptotic intermediates, can individually or collectively result in reduced malformations. “It is highly likely that understanding the biological impact of various altered in utero environments, and then modifying or reversing those environments, will result in short and long-term outcome improvements similar to those shown with congenital malformations,” Dr. Reece said.

FROM DPSG-NA 2023

Targeting Fetus-derived Gdf15 May Curb Nausea and Vomiting of Pregnancy

, and targeting the hormone prophylactically may reduce this common gestational condition.

This protein acts on the brainstem to cause emesis, and, significantly, a mother’s prior exposure to it determines the degree of NVP severity she will experience, according to international researchers including Marlena Fejzo, PhD, a clinical assistant professor of population and public Health at Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“GDF15 is at the mechanistic heart of NVP and HG [hyperemesis gravidarum],” Dr. Fejzo and colleagues wrote in Nature, pointing to the need for preventive and therapeutic strategies.

“My previous research showed an association between variation in the GDF15 gene and nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and HG, and this study takes it one step further by elucidating the mechanism. It confirms that the nausea and vomiting (N/V) hormone GDF15 is a major cause of NVP and HG,” Dr. Fejzo said.

The etiology of NVP remains poorly understood although it affects up to 80% of pregnancies. In the US, its severe form, HG, is the leading cause of hospitalization in early pregnancy and the second-leading reason for pregnancy hospitalization overall.

The immunoassay-based study showed that the majority of GDF15 in maternal blood during pregnancy comes from the fetal part of the placenta, and confirms previous studies reporting higher levels in pregnancies with more severe NVP, said Dr. Fejzo, who is who is a board member of the Hyperemesis Education and Research Foundation.

“However, what was really fascinating and surprising is that prior to pregnancy the women who have more severe NVP symptoms actually have lower levels of the hormone.”

Although the gene variant linked to HG was previously associated with higher circulating levels in maternal blood, counterintuitively, this new research showed that women with abnormally high levels prior to pregnancy have either no or very little NVP, said Dr. Fejzo. “That suggests that in humans higher levels may lead to a desensitization to the high levels of the hormone in pregnancy. Then we also proved that desensitization can occur in a mouse model.”

According to Erin Higgins, MD, a clinical assistant professor of obgyn and reproductive biology at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio, who was not involved in the study, “This is an exciting finding that may help us to better target treatment of N/V in pregnancy. Factors for NVP have been identified, but to my knowledge there has not been a clear etiology.”

Dr. Higgins cautioned, however, that the GDF15 gene seems important in normal placentation, “so it’s not as simple as blocking the gene or its receptor.” But since preconception exposure to GDF15 might decrease nausea and vomiting once a woman is pregnant, prophylactic treatment may be possible, and metformin has been suggested as a possibility, she said.

The study findings emerged from immunoassays on maternal blood samples collected at about 15 weeks (first trimester and early second trimester), from women with NVP (n = 168) or seen at a hospital for HG (n = 57). Results were compared with those from controls having similar characteristics but no significant symptoms.

Interestingly, GDF15 is also associated with cachexia, a condition similar to HG and characterized by loss of appetite and weight loss, Dr. Fejzo noted. “The hormone can be produced by malignant tumors at levels similar to those seen in pregnancy, and symptoms can be reduced by blocking GDF15 or its receptor, GFRAL. Clinical trials are already underway in cancer patients to test this.”

She is seeking funding to test the impact of increasing GDF15 levels prior to pregnancy in patients who previously experienced HG. “I am confident that desensitizing patients by increasing GDF15 prior to pregnancy and by lowering GDF15 levels during pregnancy will work. But we need to make sure we do safety studies and get the dosing and duration right, and that will take some time.”