User login

Metastatic Adamantinoma Presenting as a Cutaneous Papule

To the Editor:

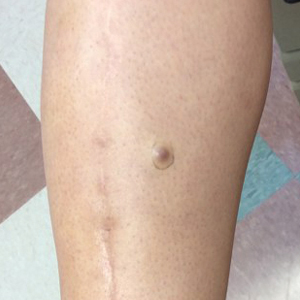

A 34-year-old woman with a history of adamantinoma of the right tibia that had been surgically resected with tibial reconstruction 5 years prior presented with a mildly tender, enlarging lesion on the right distal shin of 6 months’ duration that had started to change color. Review of systems was otherwise negative. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, slightly tender, rubbery, pink papule adjacent to the surgical scar over the right tibia (Figure 1). Given the rapid growth of the lesion and its proximity to the surgical site, a punch biopsy was performed.

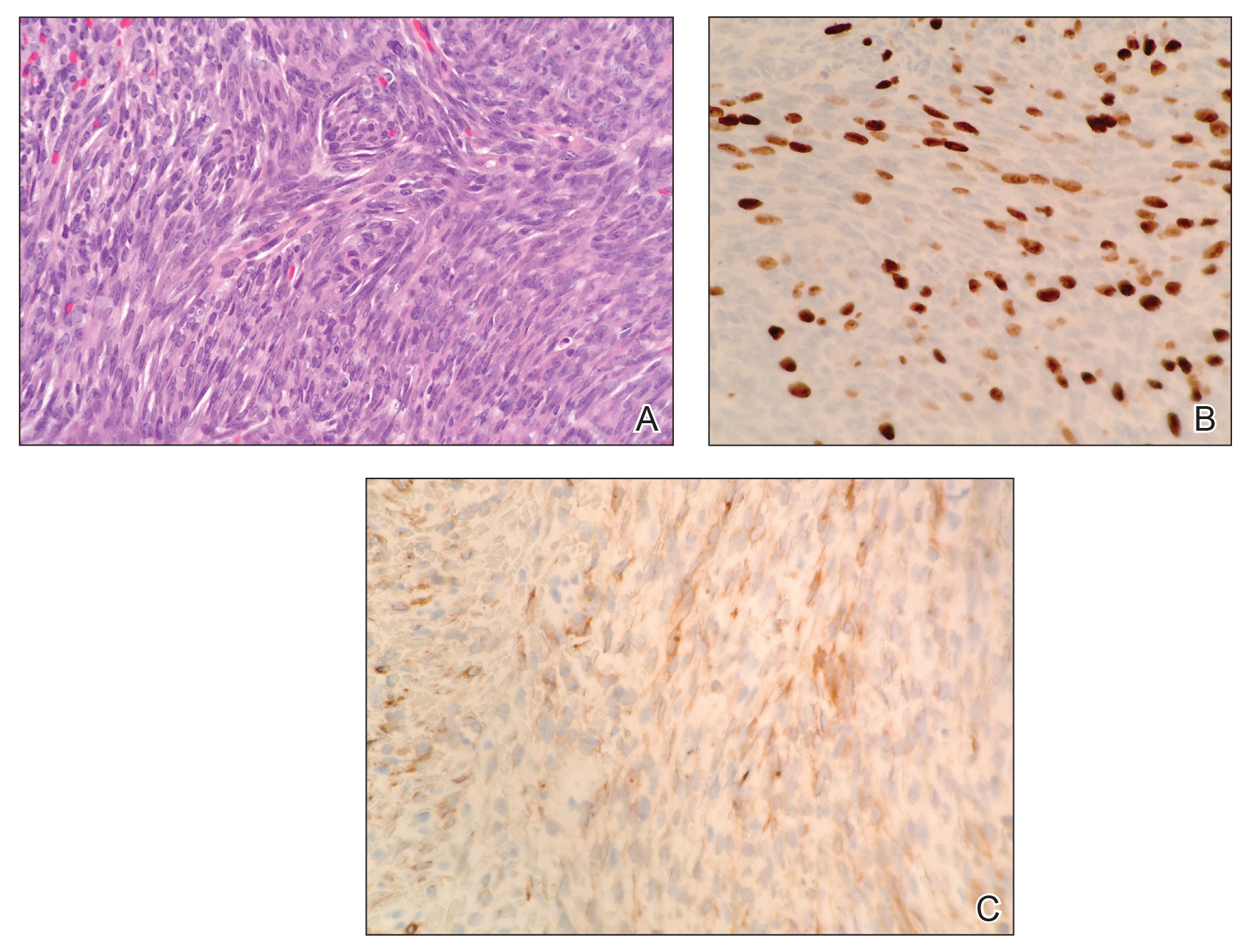

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a densely cellular dermal tumor composed of spindle cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei, numerous mitotic figures, and minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical studies revealed that approximately 40% of the tumor nuclei were immunoreactive to Ki-67 (Figure 2B), and total cytokeratin was focally positive (Figure 2C). A diagnosis of metastatic adamantinoma was made. Positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed new lytic lesions involving the T10 and L2 vertebrae (without frank spinal cord compression) and the right superior sacrum. Additionally, a small pulmonary nodule on the left upper lobe was noted on positron emission tomography, but it was below the size threshold for reliable detection. A computed tomography–guided biopsy of the T10 lesion demonstrated metastatic adamantinoma. The patient underwent a spinal stabilization procedure and discussed options regarding further oncologic and palliative management.

Adamantinoma is an extremely rare primary malignant bone tumor that typically involves the anterior portion of the tibial metaphysis or diaphysis in approximately 90% of cases. Young adults most commonly are affected in the third or fourth decades of life.1 Although the histogenesis is not clearly understood, experts have theorized that fetal implantation during embryogenesis or traumatic implantation of epithelial cells may be causes of this tumor and may explain the close pathologic similarity to basal cell carcinoma.2

Adamantinomas are slow growing, and as a result, patients often present with gradual onset of pain and swelling that persists for years.3,4 Metastasis occurs in 10% to 30% of patients, typically located in regional lymph nodes, the lungs, and distant bone.1,4 Our case represents a rare instance of adamantinoma metastasis to the skin. Although primary adamantinomas consist of both epithelial and stromal components, the typical metastatic lesions of adamantinomas are solely epithelial (often in a spindle-cell pattern),1 as was seen in our patient.

Operative removal via amputation or en bloc resection with limb salvage is the current treatment of choice. Adamantinomas are highly radioresistant, and chemotherapy has shown minimal efficacy.3,5

In conclusion, the presence of cutaneous metastasis from an adamantinoma is rare. Our case emphasizes this tumor’s potential for late metastasis as well as late recurrence.3,6 Most importantly, dermatologists should be made aware of this rare bone tumor and its unusual presentation, as early detection can aid in prognosis.

- Schowinsky JT, Ormond DR, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Tibial adamantinoma: late metastasis to the brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:95-97.

- Jain D, Jain VK, Vasishta RK, et al. Adamantinoma: a clinicopathological review and update. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:8.

- Qureshi AA, Shott S, Mallin BA, et al. Current trends in the management of adamantinoma of long bones. an international study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A:1122-1131.

- Desai SS, Jambhekar N, Agarwal M, et al. Adamantinoma of tibia: a study of 12 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:429-433.

- Weiss SW, Dorfman HD. Adamantinoma of long bone. an analysis of nine new cases with emphasis on metastasizing lesions and fibrous dysplasia-like changes. Hum Pathol. 1977;8:141-153.

- Szendroi M, Antal I, Arató G. Adamantinoma of long bones: a long-term follow-up study of 11 cases. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:209-216.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman with a history of adamantinoma of the right tibia that had been surgically resected with tibial reconstruction 5 years prior presented with a mildly tender, enlarging lesion on the right distal shin of 6 months’ duration that had started to change color. Review of systems was otherwise negative. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, slightly tender, rubbery, pink papule adjacent to the surgical scar over the right tibia (Figure 1). Given the rapid growth of the lesion and its proximity to the surgical site, a punch biopsy was performed.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a densely cellular dermal tumor composed of spindle cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei, numerous mitotic figures, and minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical studies revealed that approximately 40% of the tumor nuclei were immunoreactive to Ki-67 (Figure 2B), and total cytokeratin was focally positive (Figure 2C). A diagnosis of metastatic adamantinoma was made. Positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed new lytic lesions involving the T10 and L2 vertebrae (without frank spinal cord compression) and the right superior sacrum. Additionally, a small pulmonary nodule on the left upper lobe was noted on positron emission tomography, but it was below the size threshold for reliable detection. A computed tomography–guided biopsy of the T10 lesion demonstrated metastatic adamantinoma. The patient underwent a spinal stabilization procedure and discussed options regarding further oncologic and palliative management.

Adamantinoma is an extremely rare primary malignant bone tumor that typically involves the anterior portion of the tibial metaphysis or diaphysis in approximately 90% of cases. Young adults most commonly are affected in the third or fourth decades of life.1 Although the histogenesis is not clearly understood, experts have theorized that fetal implantation during embryogenesis or traumatic implantation of epithelial cells may be causes of this tumor and may explain the close pathologic similarity to basal cell carcinoma.2

Adamantinomas are slow growing, and as a result, patients often present with gradual onset of pain and swelling that persists for years.3,4 Metastasis occurs in 10% to 30% of patients, typically located in regional lymph nodes, the lungs, and distant bone.1,4 Our case represents a rare instance of adamantinoma metastasis to the skin. Although primary adamantinomas consist of both epithelial and stromal components, the typical metastatic lesions of adamantinomas are solely epithelial (often in a spindle-cell pattern),1 as was seen in our patient.

Operative removal via amputation or en bloc resection with limb salvage is the current treatment of choice. Adamantinomas are highly radioresistant, and chemotherapy has shown minimal efficacy.3,5

In conclusion, the presence of cutaneous metastasis from an adamantinoma is rare. Our case emphasizes this tumor’s potential for late metastasis as well as late recurrence.3,6 Most importantly, dermatologists should be made aware of this rare bone tumor and its unusual presentation, as early detection can aid in prognosis.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman with a history of adamantinoma of the right tibia that had been surgically resected with tibial reconstruction 5 years prior presented with a mildly tender, enlarging lesion on the right distal shin of 6 months’ duration that had started to change color. Review of systems was otherwise negative. Physical examination revealed an 8-mm, slightly tender, rubbery, pink papule adjacent to the surgical scar over the right tibia (Figure 1). Given the rapid growth of the lesion and its proximity to the surgical site, a punch biopsy was performed.

Histopathologic examination demonstrated a densely cellular dermal tumor composed of spindle cells with large hyperchromatic nuclei, numerous mitotic figures, and minimal eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical studies revealed that approximately 40% of the tumor nuclei were immunoreactive to Ki-67 (Figure 2B), and total cytokeratin was focally positive (Figure 2C). A diagnosis of metastatic adamantinoma was made. Positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed new lytic lesions involving the T10 and L2 vertebrae (without frank spinal cord compression) and the right superior sacrum. Additionally, a small pulmonary nodule on the left upper lobe was noted on positron emission tomography, but it was below the size threshold for reliable detection. A computed tomography–guided biopsy of the T10 lesion demonstrated metastatic adamantinoma. The patient underwent a spinal stabilization procedure and discussed options regarding further oncologic and palliative management.

Adamantinoma is an extremely rare primary malignant bone tumor that typically involves the anterior portion of the tibial metaphysis or diaphysis in approximately 90% of cases. Young adults most commonly are affected in the third or fourth decades of life.1 Although the histogenesis is not clearly understood, experts have theorized that fetal implantation during embryogenesis or traumatic implantation of epithelial cells may be causes of this tumor and may explain the close pathologic similarity to basal cell carcinoma.2

Adamantinomas are slow growing, and as a result, patients often present with gradual onset of pain and swelling that persists for years.3,4 Metastasis occurs in 10% to 30% of patients, typically located in regional lymph nodes, the lungs, and distant bone.1,4 Our case represents a rare instance of adamantinoma metastasis to the skin. Although primary adamantinomas consist of both epithelial and stromal components, the typical metastatic lesions of adamantinomas are solely epithelial (often in a spindle-cell pattern),1 as was seen in our patient.

Operative removal via amputation or en bloc resection with limb salvage is the current treatment of choice. Adamantinomas are highly radioresistant, and chemotherapy has shown minimal efficacy.3,5

In conclusion, the presence of cutaneous metastasis from an adamantinoma is rare. Our case emphasizes this tumor’s potential for late metastasis as well as late recurrence.3,6 Most importantly, dermatologists should be made aware of this rare bone tumor and its unusual presentation, as early detection can aid in prognosis.

- Schowinsky JT, Ormond DR, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Tibial adamantinoma: late metastasis to the brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:95-97.

- Jain D, Jain VK, Vasishta RK, et al. Adamantinoma: a clinicopathological review and update. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:8.

- Qureshi AA, Shott S, Mallin BA, et al. Current trends in the management of adamantinoma of long bones. an international study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A:1122-1131.

- Desai SS, Jambhekar N, Agarwal M, et al. Adamantinoma of tibia: a study of 12 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:429-433.

- Weiss SW, Dorfman HD. Adamantinoma of long bone. an analysis of nine new cases with emphasis on metastasizing lesions and fibrous dysplasia-like changes. Hum Pathol. 1977;8:141-153.

- Szendroi M, Antal I, Arató G. Adamantinoma of long bones: a long-term follow-up study of 11 cases. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:209-216.

- Schowinsky JT, Ormond DR, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Tibial adamantinoma: late metastasis to the brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2015;74:95-97.

- Jain D, Jain VK, Vasishta RK, et al. Adamantinoma: a clinicopathological review and update. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:8.

- Qureshi AA, Shott S, Mallin BA, et al. Current trends in the management of adamantinoma of long bones. an international study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A:1122-1131.

- Desai SS, Jambhekar N, Agarwal M, et al. Adamantinoma of tibia: a study of 12 cases. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:429-433.

- Weiss SW, Dorfman HD. Adamantinoma of long bone. an analysis of nine new cases with emphasis on metastasizing lesions and fibrous dysplasia-like changes. Hum Pathol. 1977;8:141-153.

- Szendroi M, Antal I, Arató G. Adamantinoma of long bones: a long-term follow-up study of 11 cases. Pathol Oncol Res. 2009;15:209-216.

Practice Points

- Metastatic adamantinoma of the skin is a rare clinical scenario.

- Dermatologists should be made aware of this rare bone tumor and its unusual presentation, as early detection can aid in prognosis.

Characterization of Knuckle (Garrod) Pads Using Optical Coherence Tomography In Vivo

To the Editor:

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that uses a low-power infrared laser light for cutaneous architecture visualization up to 2 mm in depth. Both malignant and nonmalignant lesions on OCT imaging have been correlated with histopathologic analysis.1 We describe the diagnostic features of knuckle pads on OCT.

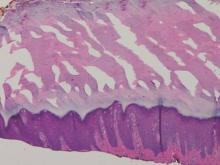

A 43-year-old-man presented with warts on the right thumb and bilateral feet of several months’ duration with noncontributory medical and social history. Physical examination revealed nontender, well-demarcated, flesh-colored, verrucous papules on the dorsal interphalangeal joints of the right thumb and several toes (Figure 1). Pinpoint vessels were absent on dermoscopy (Figure 2). Histopathologic analysis of a shave biopsy of the lesion on the left second toe revealed dense orthokeratosis with compact keratin, suggestive of reactive hyperkeratosis or a knuckle pad (Figure 3). In situ hybridization failed to demonstrate staining for human papillomavirus types 6, 11, and 16.

|  | |

| Figure 1. Verrucous papules on the left foot.

| Figure 2. Corresponding dermoscopy of the left second toe revealed an absence of pinpoint vessels. |

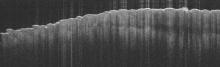

Optical coherence tomography demonstrated discrete thickening of the stratum corneum with distinctive granular and coarse textural appearance of the hyperkeratotic stratum corneum compared to normal adjacent skin. This textural difference was attributed to the alteration in collagen deposition of the knuckle pads, consistent with fibrous proliferation. Finally, OCT imaging provided further characterization of the lesion demonstrating the absence of any hair follicles and acrosyringium in areas resembling glabrous skin (Figure 4).

Knuckle pads, also known as Garrod pads, were first described by Garrod2 in 1893. They are benign, asymptomatic, fibrotic thickenings of the skin. Lesions are smooth, firm, flesh colored, and located on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet along the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints. Knuckle pads are common, can develop at any age, and are observed more frequently in men than in women.3

Primary knuckle pads can be sporadic or associated with other conditions such as palmoplantar keratoderma, acrokeratoelastoidosis costa, fibrosing disorders, or Bart-Pumphrey syndrome.4 Secondary knuckle pads, which are more common, occur in sites of repetitive trauma or pressure. Certain occupations (eg, mechanics) or hobbies (eg, boxing) increase the risk for developing knuckle pads.3,4

The diagnosis of knuckle pads is usually made clinically, though several other conditions mimic knuckle pads, including scars, keloids, calluses, verruca vulgaris, fibromas, and rheumatoid nodules.3,5 We report a description of knuckle pads that was diagnosed with OCT imaging. Further characterization of both malignant and nonmalignant lesions on OCT imaging will contribute new insights to the role of OCT in the noninvasive diagnosis of skin diseases, pending future studies.

1. Forsea AM, Carstea EM, Ghervase L, et al. Clinical application of optical coherence tomography for the imaging of non-melanocytic cutaneous tumors: a pilot multi-modal study. J Med Life. 2010;3:381-389.

2. Garrod AE. On an unusual form of nodule upon joints of the fingers. St Bartholomew’s Hosp Rep. 1893;29:157-161.

3. Kodama BF, Gentry RH, Fitzpatrick JE. Papules and plaques over the joint spaces. knuckle pads (heloderma). Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1044-1045, 1047.

4. Nenoff P, Woitek G. Images in clinical medicine. knuckle pads. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2451.

5. Sehgal VN, Singh M, Saxena HM, et al. Primary knuckle pads. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:337-339.

To the Editor:

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that uses a low-power infrared laser light for cutaneous architecture visualization up to 2 mm in depth. Both malignant and nonmalignant lesions on OCT imaging have been correlated with histopathologic analysis.1 We describe the diagnostic features of knuckle pads on OCT.

A 43-year-old-man presented with warts on the right thumb and bilateral feet of several months’ duration with noncontributory medical and social history. Physical examination revealed nontender, well-demarcated, flesh-colored, verrucous papules on the dorsal interphalangeal joints of the right thumb and several toes (Figure 1). Pinpoint vessels were absent on dermoscopy (Figure 2). Histopathologic analysis of a shave biopsy of the lesion on the left second toe revealed dense orthokeratosis with compact keratin, suggestive of reactive hyperkeratosis or a knuckle pad (Figure 3). In situ hybridization failed to demonstrate staining for human papillomavirus types 6, 11, and 16.

|  | |

| Figure 1. Verrucous papules on the left foot.

| Figure 2. Corresponding dermoscopy of the left second toe revealed an absence of pinpoint vessels. |

Optical coherence tomography demonstrated discrete thickening of the stratum corneum with distinctive granular and coarse textural appearance of the hyperkeratotic stratum corneum compared to normal adjacent skin. This textural difference was attributed to the alteration in collagen deposition of the knuckle pads, consistent with fibrous proliferation. Finally, OCT imaging provided further characterization of the lesion demonstrating the absence of any hair follicles and acrosyringium in areas resembling glabrous skin (Figure 4).

Knuckle pads, also known as Garrod pads, were first described by Garrod2 in 1893. They are benign, asymptomatic, fibrotic thickenings of the skin. Lesions are smooth, firm, flesh colored, and located on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet along the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints. Knuckle pads are common, can develop at any age, and are observed more frequently in men than in women.3

Primary knuckle pads can be sporadic or associated with other conditions such as palmoplantar keratoderma, acrokeratoelastoidosis costa, fibrosing disorders, or Bart-Pumphrey syndrome.4 Secondary knuckle pads, which are more common, occur in sites of repetitive trauma or pressure. Certain occupations (eg, mechanics) or hobbies (eg, boxing) increase the risk for developing knuckle pads.3,4

The diagnosis of knuckle pads is usually made clinically, though several other conditions mimic knuckle pads, including scars, keloids, calluses, verruca vulgaris, fibromas, and rheumatoid nodules.3,5 We report a description of knuckle pads that was diagnosed with OCT imaging. Further characterization of both malignant and nonmalignant lesions on OCT imaging will contribute new insights to the role of OCT in the noninvasive diagnosis of skin diseases, pending future studies.

To the Editor:

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a noninvasive imaging technique that uses a low-power infrared laser light for cutaneous architecture visualization up to 2 mm in depth. Both malignant and nonmalignant lesions on OCT imaging have been correlated with histopathologic analysis.1 We describe the diagnostic features of knuckle pads on OCT.

A 43-year-old-man presented with warts on the right thumb and bilateral feet of several months’ duration with noncontributory medical and social history. Physical examination revealed nontender, well-demarcated, flesh-colored, verrucous papules on the dorsal interphalangeal joints of the right thumb and several toes (Figure 1). Pinpoint vessels were absent on dermoscopy (Figure 2). Histopathologic analysis of a shave biopsy of the lesion on the left second toe revealed dense orthokeratosis with compact keratin, suggestive of reactive hyperkeratosis or a knuckle pad (Figure 3). In situ hybridization failed to demonstrate staining for human papillomavirus types 6, 11, and 16.

|  | |

| Figure 1. Verrucous papules on the left foot.

| Figure 2. Corresponding dermoscopy of the left second toe revealed an absence of pinpoint vessels. |

Optical coherence tomography demonstrated discrete thickening of the stratum corneum with distinctive granular and coarse textural appearance of the hyperkeratotic stratum corneum compared to normal adjacent skin. This textural difference was attributed to the alteration in collagen deposition of the knuckle pads, consistent with fibrous proliferation. Finally, OCT imaging provided further characterization of the lesion demonstrating the absence of any hair follicles and acrosyringium in areas resembling glabrous skin (Figure 4).

Knuckle pads, also known as Garrod pads, were first described by Garrod2 in 1893. They are benign, asymptomatic, fibrotic thickenings of the skin. Lesions are smooth, firm, flesh colored, and located on the dorsal aspect of the hands and feet along the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints. Knuckle pads are common, can develop at any age, and are observed more frequently in men than in women.3

Primary knuckle pads can be sporadic or associated with other conditions such as palmoplantar keratoderma, acrokeratoelastoidosis costa, fibrosing disorders, or Bart-Pumphrey syndrome.4 Secondary knuckle pads, which are more common, occur in sites of repetitive trauma or pressure. Certain occupations (eg, mechanics) or hobbies (eg, boxing) increase the risk for developing knuckle pads.3,4

The diagnosis of knuckle pads is usually made clinically, though several other conditions mimic knuckle pads, including scars, keloids, calluses, verruca vulgaris, fibromas, and rheumatoid nodules.3,5 We report a description of knuckle pads that was diagnosed with OCT imaging. Further characterization of both malignant and nonmalignant lesions on OCT imaging will contribute new insights to the role of OCT in the noninvasive diagnosis of skin diseases, pending future studies.

1. Forsea AM, Carstea EM, Ghervase L, et al. Clinical application of optical coherence tomography for the imaging of non-melanocytic cutaneous tumors: a pilot multi-modal study. J Med Life. 2010;3:381-389.

2. Garrod AE. On an unusual form of nodule upon joints of the fingers. St Bartholomew’s Hosp Rep. 1893;29:157-161.

3. Kodama BF, Gentry RH, Fitzpatrick JE. Papules and plaques over the joint spaces. knuckle pads (heloderma). Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1044-1045, 1047.

4. Nenoff P, Woitek G. Images in clinical medicine. knuckle pads. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2451.

5. Sehgal VN, Singh M, Saxena HM, et al. Primary knuckle pads. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:337-339.

1. Forsea AM, Carstea EM, Ghervase L, et al. Clinical application of optical coherence tomography for the imaging of non-melanocytic cutaneous tumors: a pilot multi-modal study. J Med Life. 2010;3:381-389.

2. Garrod AE. On an unusual form of nodule upon joints of the fingers. St Bartholomew’s Hosp Rep. 1893;29:157-161.

3. Kodama BF, Gentry RH, Fitzpatrick JE. Papules and plaques over the joint spaces. knuckle pads (heloderma). Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:1044-1045, 1047.

4. Nenoff P, Woitek G. Images in clinical medicine. knuckle pads. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2451.

5. Sehgal VN, Singh M, Saxena HM, et al. Primary knuckle pads. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:337-339.