User login

The PASTA Bridge – A Repair Technique for Partial Articular-Sided Rotator Cuff Tears: A Biomechanical Evaluation of Construct Strength

ABSTRACT

Partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon avulsion (PASTA) tears are a common clinical problem that can require surgical intervention to reduce patient symptoms. Currently, no consensus has been reached regarding the optimal repair technique. The PASTA Bridge technique was developed by the senior author to address these types of lesions. A controlled laboratory study was performed comparing the PASTA Bridge with a standard transtendon rotator cuff repair to confirm its biomechanical efficacy. A 50% articular-sided partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon was created on 6 matched pairs of fresh-frozen cadaveric shoulders. For each matched pair, 1 humerus received a PASTA Bridge repair, whereas the contralateral side received a repair using a single suture anchor with a horizontal mattress suture. The ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness were determined from the load-displacement results for each sample. Video tracking software was used to determine the cyclic displacement of each sample at the articular margin and the repair site. Strain at the margin and repair site was then calculated using this collected data. There were no significant differences between the 2 repairs in ultimate load (P = .577), strain at the repair site (P = .355), or strain at the margin (P = .801). No instance of failure was due to the PASTA Bridge construct itself. The results of this study have established that the PASTA Bridge is biomechanically equivalent to the transtendon repair technique. The PASTA Bridge is technically easy, percutaneous, reproducible, and is associated with fewer risks.

Continue to: Rotator cuff tests...

Rotator cuff tears can be classified as full-thickness or partial-thickness; the latter being further divided into the bursal surface, articular-sided, or intratendinous tears. A study analyzing the anatomical distribution of partial tears found that approximately 50% of those at the rotator cuff footprint were articular-sided and predominantly involved the supraspinatus tendon.1 These partial-thickness articular-sided supraspinatus tendon avulsion tears have been coined “PASTA lesions.” Current treatment recommendations suggest that a debridement, a transtendon technique, or a “takedown” method of completing a partial tear and performing a full-thickness repair be utilized for partial-thickness rotator cuff repairs.

The primary goal of a partial cuff repair is to reestablish the tendon footprint at the humeral head. It has been argued that the “takedown” method alters the normal footprint and presents tension complications that can result in poor outcomes.2-5 Also, if the full-thickness repair fails, the patient is left with a full-thickness tear that could be more disabling. The trans-tendon technique has proven to be superior in this sense, demonstrating an improvement in both footprint contact and healing potential.3-5 This article aims to evaluate the biomechanical effectiveness of a new PASTA lesion repair technique, the PASTA Bridge,6 when compared with a traditional transtendon suture anchor repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

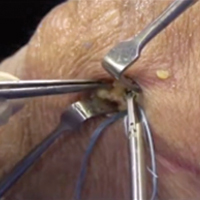

BIOMECHANICAL OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE: PASTA BRIDGE REPAIR

A 17-gauge spinal needle was used to create a puncture in the supraspinatus tendon approximately 7.5 mm anterior to the centerline of the footprint and just medial to the simulated tear line. A 1.1-mm blunt Nitinol wire (Arthrex) was placed over the top of the spinal needle, and the spinal needle was removed. A 2.4-mm portal dilation instrument (Arthrex) was placed over the top of the 1.1 blunt wire (Arthrex) followed by the drill spear for the 2.4-mm BioComposite SutureTak (Arthrex). A pilot hole was created just medial to the simulated tear using the spear and a 1.8-mm drill followed by insertion of a 2.4-mm BioComposite SutureTak (Arthrex). This process was repeated approximately 5 mm posterior to the centerline of the footprint. A strand of suture from each anchor was tied in a manner similar to the “double pulley” method described by Lo and Burkhart.3 The opposing 2 limbs were tensioned to pull the knot taut over the repair site and fixed laterally with a 4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock (Arthrex) placed approximately 1 cm lateral to the greater tuberosity.

BIOMECHANICAL OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE: CONTROL (4.5-MM CORKSCREW FT GROUP)

A No. 11 scalpel was used to create a puncture in the tendon for a transtendon approach. A 4.5-mm titanium Corkscrew FT (Arthrex) was placed just medial to the beginning of the simulated tear. The No. 2 FiberWire (Arthrex) was passed anterior and posterior to the hole made for the transtendon approach. A horizontal mattress stitch was tied using a standard 2-handed knot technique.

BIOMECHANICAL ANALYSIS

The proximal humeri with intact supraspinatus tendons were removed from 6 matched pairs of fresh-frozen cadaver shoulders (3 males, 3 females; average age, 49 ± 12 years). The shaft of the humerus was potted in fiberglass resin. For each sample, a partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon was replicated by using a sharp blade to transect 50% of the medial side of the supraspinatus from the tuberosity.2,5 From each matched pair, 1 humerus was selected to receive a PASTA Bridge repair,6 and the contralateral repair was performed using one 4.5-mm titanium Corkscrew FT. Half of the samples of each repair were performed on the right humerus to avoid a mechanical bias. Each repair was performed by the same orthopedic surgeon.

Continue to: Biomechanical testing was...

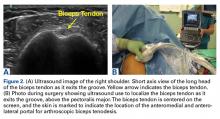

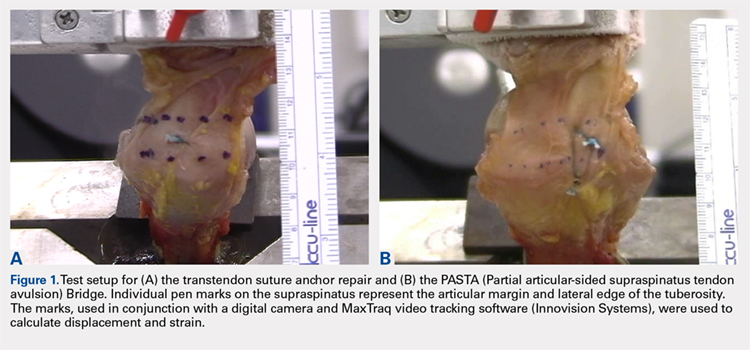

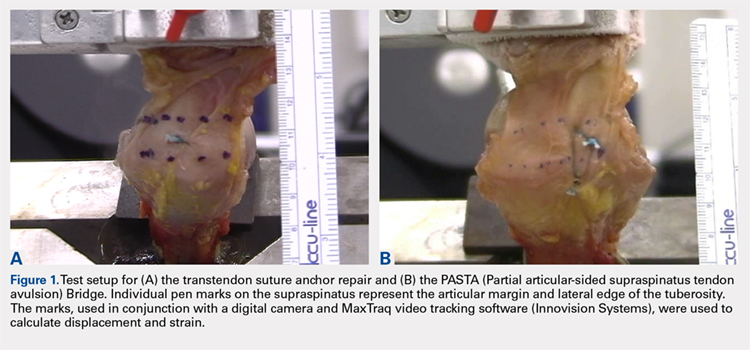

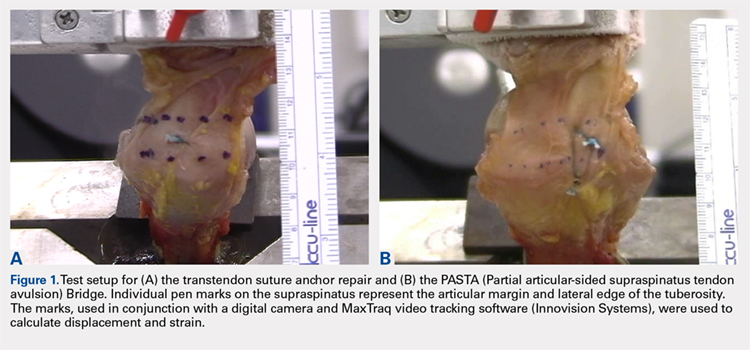

Biomechanical testing was conducted using an INSTRON 8871 Axial Table Top Servo-hydraulic Testing System (INSTRON), with a 5 kN load cell attached to the crosshead. The system was calibrated using FastTrack software (AEC Software), and both the load and position controls were run through WaveMaker software (WaveMaker). Each sample was positioned on a fixed angle fixture and secured to the testing surface so that the direction of pull would be performed 45° to the humeral shaft. A custom fixture with inter-digitated brass clamps was attached to the crosshead, and dry ice was used to freeze the tendon to the clamp. The test setup can be seen in Figures 1A, 1B.

Each sample was pre-loaded to 10 N to remove slack from the system. Pre-loading was followed by cyclic loading between 10 N and 100 N,7-11 at 1 Hz, for 100 cycles. One-hundred cycles were chosen based on literature stating that the majority of the cyclic displacement occurs in the first 100 cycles.7-10 Post cycling, the samples were loaded to failure at a rate of 33 mm/sec.7-12 Load and position data were recorded at 500 Hz, and the mode of failure was noted for each sample.

Before loading, a soft-tissue marker was used to create individual marks on the supraspinatus in-line with the articular margin and lateral edge of the tuberosity (Figures 1A, 1B). The individual marks, a digital camera, and MaxTraq video tracking software (Innovision Systems) were used to calculate displacement and strain.

For each sample, the ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness were determined from the load-displacement results. Video tracking software was used to determine the cyclic displacement of each sample at both the articular margin (medial dots) and at the repair site. The strain at these 2 locations was calculated by dividing the cyclic displacement of the respective site by the distance between the site of interest and the lateral edge of the tuberosity (lateral marks) (ΔL/L). Paired t tests (α = 0.05) were used to determine if differences in ultimate load or strain between the 2 repairs were significant.

RESULTS

BIOMECHANICAL ANALYSIS

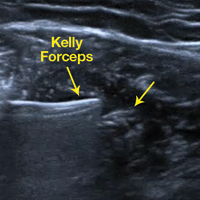

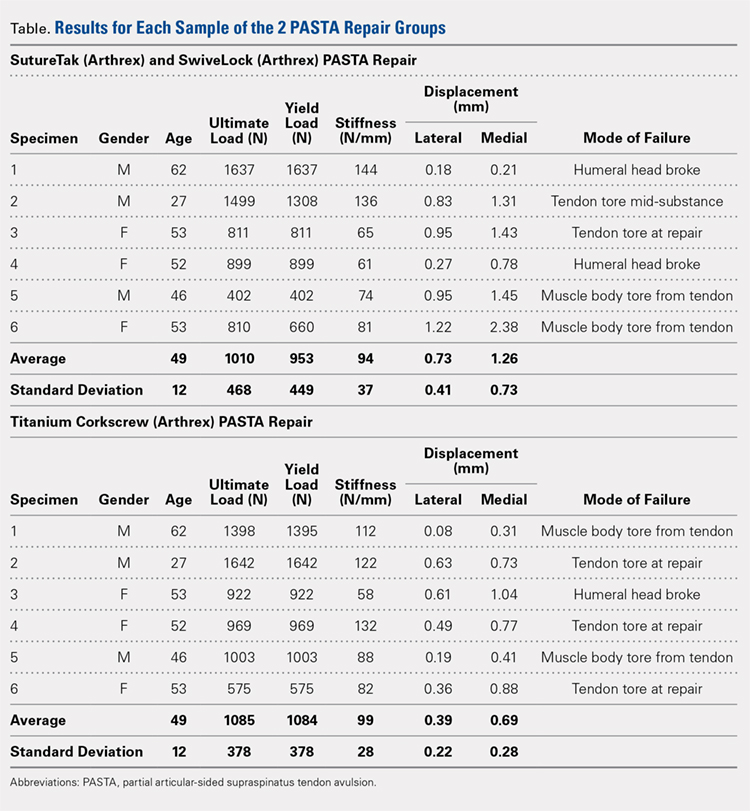

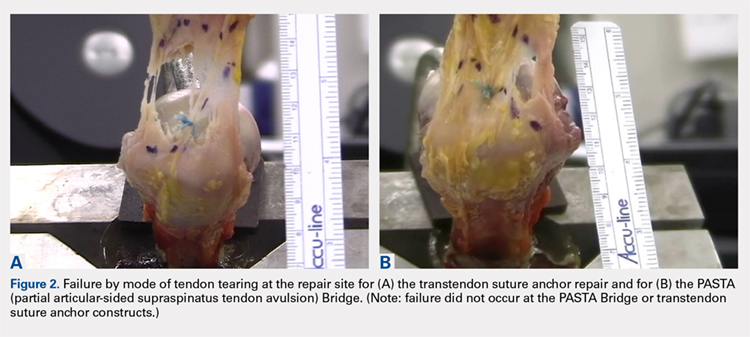

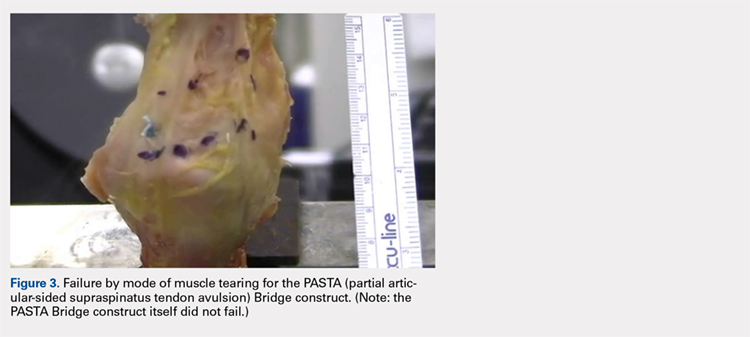

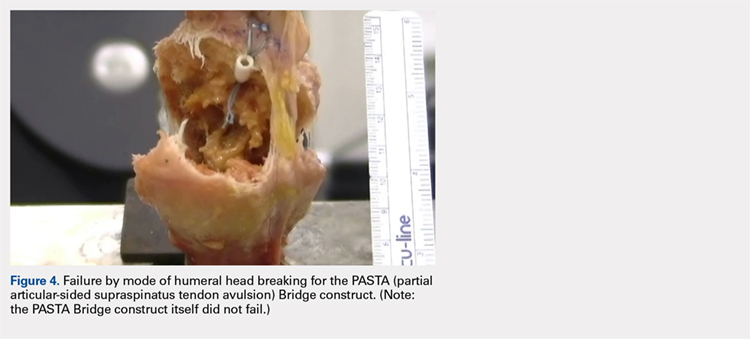

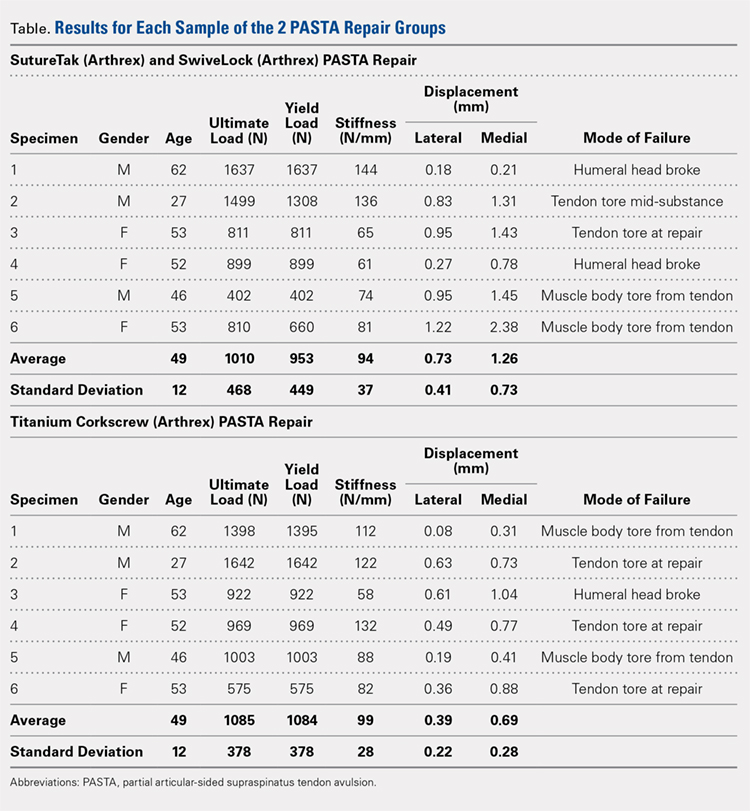

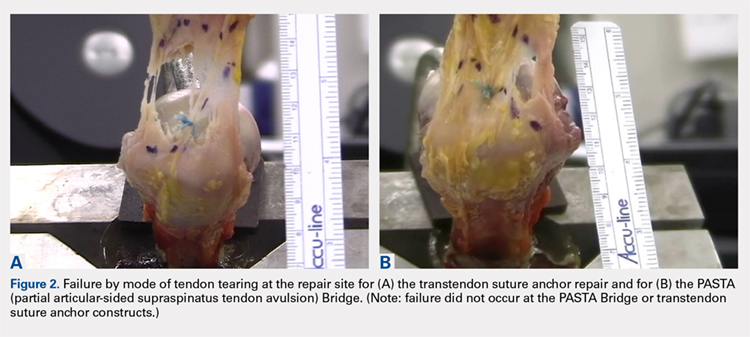

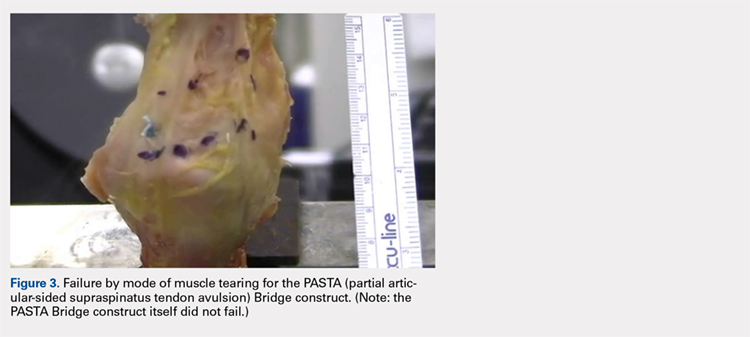

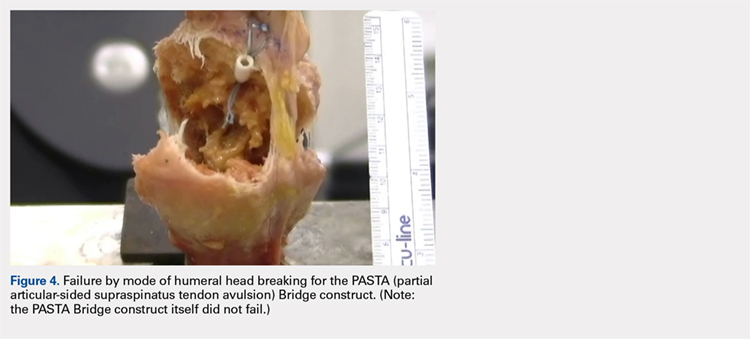

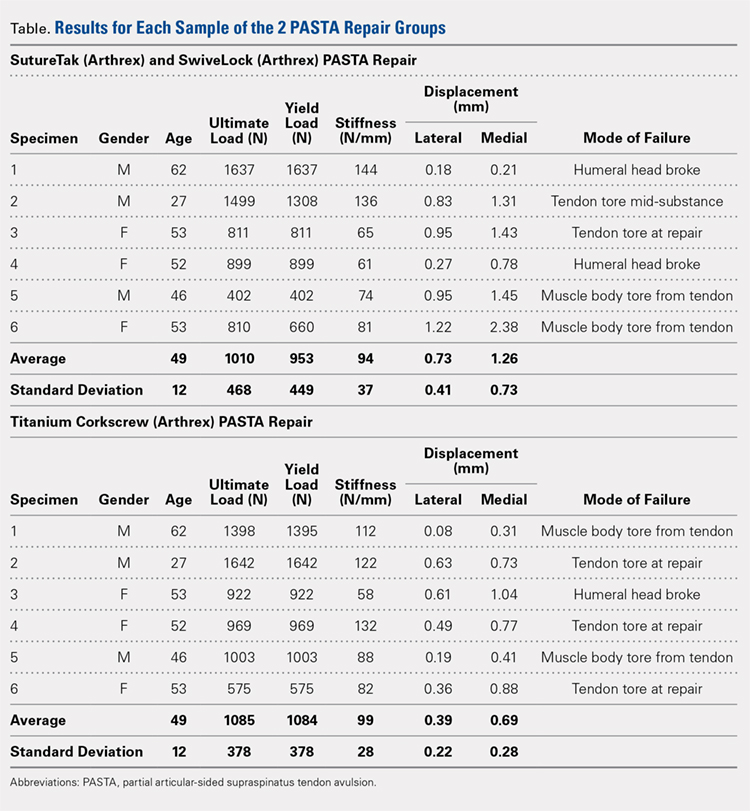

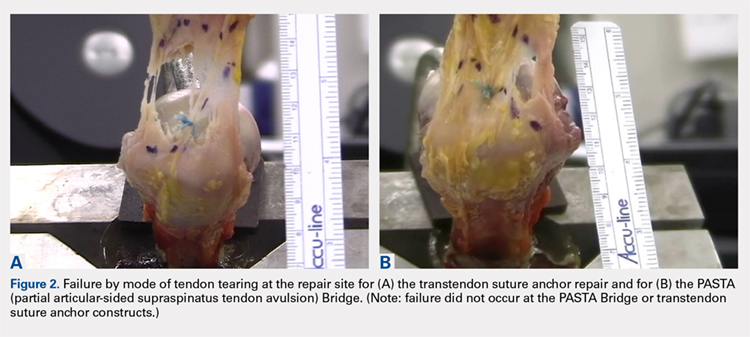

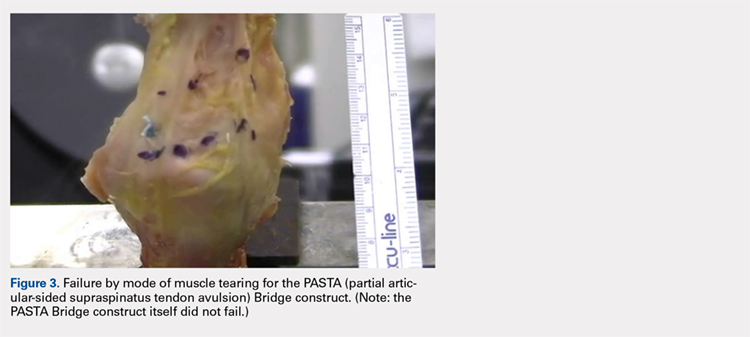

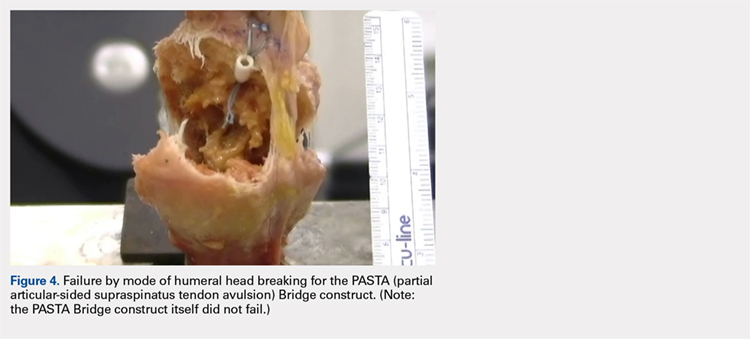

The results of the biomechanical testing are provided in the Table. There were no significant differences between the 2 repairs in ultimate load (P = .577), strain at the repair site (P = .355), or strain at the margin (P = .801). A post-hoc power analysis revealed that a sample size of at least 20 matched pairs would be needed to establish a significant difference for strain at the repair site. The modes of failure were mid-substance tendon tearing, the humeral head breaking, tearing at the musculotendinous junction, or the tendon tearing at the repair site. All 4 modes of failure occurred in at least 1 sample from both repair groups (Figures 2-4). Visual inspection of the samples post-testing revealed no damage to the anchors or sutures. A representative picture of the tendon tearing at the repair site can be seen in Figures 2A, 2B.

Continue to: The purpose of...

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the biomechanical strength of a new technique for PASTA repairs—the PASTA Bridge.6 After creation of a partial-thickness tear on a cadaveric model, we compared the PASTA Bridge technique6 with a standard transtendon suture anchor repair. We hypothesized that the PASTA Bridge would yield equivalent or better biomechanical properties including the ultimate load to failure and the degree of strain at different locations in the repair. Our results supported this hypothesis. The PASTA Bridge was biomechanically equivalent to transtendon repair.

For repairs of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, 2 traditional techniques are transtendon repairs and the “takedown” method of completing a partial tear into a full tear with a subsequent repair.13 While clinical outcomes of the 2 methods suggest no superiority over the other,13 studies have demonstrated a biomechanical advantage with transtendon repairs. Repairs of PASTA lesions exhibit both lower strain and displacement of the repaired tendon compared with a full-thickness repair.2-5 Failure of the “takedown” method results in a full-thickness rotator cuff tear as opposed to a partial tear. This outcome can prove to be more debilitating for the patient. Furthermore, Mazzocca and colleagues5 illustrated that for partial tears >25% thickness, the cuff strain returned to the intact state once repaired.

Our data suggest that biomechanically the transtendon and the PASTA Bridge6 techniques were equivalent. While the ultimate load and strain at repair sites are comparable, the PASTA Bridge is percutaneous and presents significantly less risk of complications. The PASTA Bridge6 uses a medial row horizontal mattress with a lateral row fixation to recreate the rotator cuff footprint. It has been postulated that reestablishing a higher percentage of the footprint can aide in tendon-bone healing, having valuable implications for both biological and clinical outcomes of the patient.3,4,14 Greater contact at the tendon-bone interface may allow more fibers to participate in the healing process.14 In their analysis of rotator cuff repair, Apreleva and colleagues14 asserted that more laterally placed suture anchors may increase the repair-site area. The lateral anchors of the PASTA Bridge help not only to increase the footprint and thereby the healing potential of the repair but also assist in taking pressure off the medial row anchors.

In their report on double-row rotator cuff repair, Lo and Burkhart3 suggest that double-row fixation is superior to single-row repairs for a variety of reasons. Primarily, double-row techniques increase the number of points of fixation, which will secondarily reduce both the stress and load at each suture point.3 This effect improves the overall strength of the repair construct. Use of the lateral anchor of the PASTA Bridge6 allows the medial anchors to act as pivot points. Placing the stress laterally, the configuration allows for movement and strain distribution without sacrificing the integrity of the repair. In our analysis, failure occurred by the tendon tearing mid-substance, humeral head breaking, tendon tearing at the repair site, and tearing at the musculotendinous junction (Figures 2-4). There was no instance of failure due to the construct itself indicating that the 2.4-mm medial anchors are more than adequate for the PASTA Bridge.6 When visually inspecting the samples after failure, there was no damage to the anchors or sutures. This observation indicates that the PASTA Bridge construct is remarkably strong and capable of withstanding excessive forces.

There were some potential limitations of this study. The small sample size modified the potential for identifying significant differences between the groups. A post-hoc power analysis revealed that a sample size of at least 20 matched pairs would be required to determine a significant difference between the 2 repair groups in strain at the repair site. We did not test this many pairs because the data was so similar after 6 matched pairs that it did not warrant continuing further. Additional research should be done with larger sample populations to evaluate the biomechanical efficacy of this technique further.

CONCLUSION

The PASTA Bridge6 creates a strong construct for repair of articular-sided partial-thickness tears of the supraspinatus. The data suggest the PASTA Bridge6 is biomechanically equivalent to the gold standard transtendon suture anchor repair. The PASTA Bridge6 is technically sound, percutaneous, and presents less risk of complications. It does not require arthroscopic knot tying and carries only minimal risk of damage to residual tissues. In our analysis, there were no failures of the actual construct, asserting that the PASTA Bridge6 is a strong, durable repair. The PASTA Bridge6 should be strongly considered by surgeons treating PASTA lesions.

1. Schaeffeler C, Mueller D, Kirchhoff C, Wolf P, Rummeny EJ, Woertler K. Tears at the rotator cuff footprint: prevalence and imaging characteristics in 305 MR arthrograms of the shoulder. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1477-1484. doi:10.1007/s00330-011-2066-x.

2. Gonzalez-Lomas G, Kippe MA, Brown GD, et al. In situ transtendon repair outperforms tear completion and repair for partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):722-728.

3. Lo IKY, Burkhart SS. Transtendon arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness, articular surface tears of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2004; 20(2):214-220. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.042.

4. Mazzocca AD, Millett PJ, Guanche CA, Santangelo SA, Arciero RA. Arthroscopic single-row versus double-row suture anchor rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(12):1861-1868.

5. Mazzocca AD, Rincon LM, O’Connor RW, et al. Intra-articular partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: analysis of injured and repaired strain behavior. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):110-116. doi:10.1177/0363546507307502.

6. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. The PASTA bridge: a technique for the arthroscopic repair of PASTA lesions. Arthrosc Tech. In Press. Epub 2017 Sept 18.

7. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing and ultimate failure strength of biodegradable glenoid anchors. Arthroscopy. 2008; 24(2):224-228. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.011.

8. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing of biodegradable suture anchors containing 2 high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2007; 23(4):355-360. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2006.12.009.

9. Barber FA, Feder SM, Burkhart SS, Ahrens J. The relationship of suture anchor failure and bone density to proximal humerus location: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(3):340-345. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.12.007.

10. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Richards DP. Sutures and suture anchors: update 2003. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):985-990.

11. Burkhart SS, Johnson TC, Wirth MA, Athanasiou KA. Cyclic loading of transosseous rotator cuff repairs: tension overload as a possible cause of failure. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(2):172-176. doi:10.1016/S0749-8063(97)90151-1.

12. Hecker AT, Shea M, Hayhurst JO, Myers ER, Meeks LW, Hayes WC. Pull-out strength of suture anchors for rotator cuff and bankart lesion repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1993; 21(6):874-879.

13. Strauss EJ, Salata MJ, Kercher J, et al. The arthroscopic management of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):568-580. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.09.019.

14. Apreleva M, Özbaydar M, Fitzgibbons PG, Warner JJP. Rotator cuff tears: the effect of the reconstruction method on three-dimensional repair-site area. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):519-526. doi:10.1053/jars.2002.32930.

ABSTRACT

Partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon avulsion (PASTA) tears are a common clinical problem that can require surgical intervention to reduce patient symptoms. Currently, no consensus has been reached regarding the optimal repair technique. The PASTA Bridge technique was developed by the senior author to address these types of lesions. A controlled laboratory study was performed comparing the PASTA Bridge with a standard transtendon rotator cuff repair to confirm its biomechanical efficacy. A 50% articular-sided partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon was created on 6 matched pairs of fresh-frozen cadaveric shoulders. For each matched pair, 1 humerus received a PASTA Bridge repair, whereas the contralateral side received a repair using a single suture anchor with a horizontal mattress suture. The ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness were determined from the load-displacement results for each sample. Video tracking software was used to determine the cyclic displacement of each sample at the articular margin and the repair site. Strain at the margin and repair site was then calculated using this collected data. There were no significant differences between the 2 repairs in ultimate load (P = .577), strain at the repair site (P = .355), or strain at the margin (P = .801). No instance of failure was due to the PASTA Bridge construct itself. The results of this study have established that the PASTA Bridge is biomechanically equivalent to the transtendon repair technique. The PASTA Bridge is technically easy, percutaneous, reproducible, and is associated with fewer risks.

Continue to: Rotator cuff tests...

Rotator cuff tears can be classified as full-thickness or partial-thickness; the latter being further divided into the bursal surface, articular-sided, or intratendinous tears. A study analyzing the anatomical distribution of partial tears found that approximately 50% of those at the rotator cuff footprint were articular-sided and predominantly involved the supraspinatus tendon.1 These partial-thickness articular-sided supraspinatus tendon avulsion tears have been coined “PASTA lesions.” Current treatment recommendations suggest that a debridement, a transtendon technique, or a “takedown” method of completing a partial tear and performing a full-thickness repair be utilized for partial-thickness rotator cuff repairs.

The primary goal of a partial cuff repair is to reestablish the tendon footprint at the humeral head. It has been argued that the “takedown” method alters the normal footprint and presents tension complications that can result in poor outcomes.2-5 Also, if the full-thickness repair fails, the patient is left with a full-thickness tear that could be more disabling. The trans-tendon technique has proven to be superior in this sense, demonstrating an improvement in both footprint contact and healing potential.3-5 This article aims to evaluate the biomechanical effectiveness of a new PASTA lesion repair technique, the PASTA Bridge,6 when compared with a traditional transtendon suture anchor repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BIOMECHANICAL OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE: PASTA BRIDGE REPAIR

A 17-gauge spinal needle was used to create a puncture in the supraspinatus tendon approximately 7.5 mm anterior to the centerline of the footprint and just medial to the simulated tear line. A 1.1-mm blunt Nitinol wire (Arthrex) was placed over the top of the spinal needle, and the spinal needle was removed. A 2.4-mm portal dilation instrument (Arthrex) was placed over the top of the 1.1 blunt wire (Arthrex) followed by the drill spear for the 2.4-mm BioComposite SutureTak (Arthrex). A pilot hole was created just medial to the simulated tear using the spear and a 1.8-mm drill followed by insertion of a 2.4-mm BioComposite SutureTak (Arthrex). This process was repeated approximately 5 mm posterior to the centerline of the footprint. A strand of suture from each anchor was tied in a manner similar to the “double pulley” method described by Lo and Burkhart.3 The opposing 2 limbs were tensioned to pull the knot taut over the repair site and fixed laterally with a 4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock (Arthrex) placed approximately 1 cm lateral to the greater tuberosity.

BIOMECHANICAL OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE: CONTROL (4.5-MM CORKSCREW FT GROUP)

A No. 11 scalpel was used to create a puncture in the tendon for a transtendon approach. A 4.5-mm titanium Corkscrew FT (Arthrex) was placed just medial to the beginning of the simulated tear. The No. 2 FiberWire (Arthrex) was passed anterior and posterior to the hole made for the transtendon approach. A horizontal mattress stitch was tied using a standard 2-handed knot technique.

BIOMECHANICAL ANALYSIS

The proximal humeri with intact supraspinatus tendons were removed from 6 matched pairs of fresh-frozen cadaver shoulders (3 males, 3 females; average age, 49 ± 12 years). The shaft of the humerus was potted in fiberglass resin. For each sample, a partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon was replicated by using a sharp blade to transect 50% of the medial side of the supraspinatus from the tuberosity.2,5 From each matched pair, 1 humerus was selected to receive a PASTA Bridge repair,6 and the contralateral repair was performed using one 4.5-mm titanium Corkscrew FT. Half of the samples of each repair were performed on the right humerus to avoid a mechanical bias. Each repair was performed by the same orthopedic surgeon.

Continue to: Biomechanical testing was...

Biomechanical testing was conducted using an INSTRON 8871 Axial Table Top Servo-hydraulic Testing System (INSTRON), with a 5 kN load cell attached to the crosshead. The system was calibrated using FastTrack software (AEC Software), and both the load and position controls were run through WaveMaker software (WaveMaker). Each sample was positioned on a fixed angle fixture and secured to the testing surface so that the direction of pull would be performed 45° to the humeral shaft. A custom fixture with inter-digitated brass clamps was attached to the crosshead, and dry ice was used to freeze the tendon to the clamp. The test setup can be seen in Figures 1A, 1B.

Each sample was pre-loaded to 10 N to remove slack from the system. Pre-loading was followed by cyclic loading between 10 N and 100 N,7-11 at 1 Hz, for 100 cycles. One-hundred cycles were chosen based on literature stating that the majority of the cyclic displacement occurs in the first 100 cycles.7-10 Post cycling, the samples were loaded to failure at a rate of 33 mm/sec.7-12 Load and position data were recorded at 500 Hz, and the mode of failure was noted for each sample.

Before loading, a soft-tissue marker was used to create individual marks on the supraspinatus in-line with the articular margin and lateral edge of the tuberosity (Figures 1A, 1B). The individual marks, a digital camera, and MaxTraq video tracking software (Innovision Systems) were used to calculate displacement and strain.

For each sample, the ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness were determined from the load-displacement results. Video tracking software was used to determine the cyclic displacement of each sample at both the articular margin (medial dots) and at the repair site. The strain at these 2 locations was calculated by dividing the cyclic displacement of the respective site by the distance between the site of interest and the lateral edge of the tuberosity (lateral marks) (ΔL/L). Paired t tests (α = 0.05) were used to determine if differences in ultimate load or strain between the 2 repairs were significant.

RESULTS

BIOMECHANICAL ANALYSIS

The results of the biomechanical testing are provided in the Table. There were no significant differences between the 2 repairs in ultimate load (P = .577), strain at the repair site (P = .355), or strain at the margin (P = .801). A post-hoc power analysis revealed that a sample size of at least 20 matched pairs would be needed to establish a significant difference for strain at the repair site. The modes of failure were mid-substance tendon tearing, the humeral head breaking, tearing at the musculotendinous junction, or the tendon tearing at the repair site. All 4 modes of failure occurred in at least 1 sample from both repair groups (Figures 2-4). Visual inspection of the samples post-testing revealed no damage to the anchors or sutures. A representative picture of the tendon tearing at the repair site can be seen in Figures 2A, 2B.

Continue to: The purpose of...

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the biomechanical strength of a new technique for PASTA repairs—the PASTA Bridge.6 After creation of a partial-thickness tear on a cadaveric model, we compared the PASTA Bridge technique6 with a standard transtendon suture anchor repair. We hypothesized that the PASTA Bridge would yield equivalent or better biomechanical properties including the ultimate load to failure and the degree of strain at different locations in the repair. Our results supported this hypothesis. The PASTA Bridge was biomechanically equivalent to transtendon repair.

For repairs of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, 2 traditional techniques are transtendon repairs and the “takedown” method of completing a partial tear into a full tear with a subsequent repair.13 While clinical outcomes of the 2 methods suggest no superiority over the other,13 studies have demonstrated a biomechanical advantage with transtendon repairs. Repairs of PASTA lesions exhibit both lower strain and displacement of the repaired tendon compared with a full-thickness repair.2-5 Failure of the “takedown” method results in a full-thickness rotator cuff tear as opposed to a partial tear. This outcome can prove to be more debilitating for the patient. Furthermore, Mazzocca and colleagues5 illustrated that for partial tears >25% thickness, the cuff strain returned to the intact state once repaired.

Our data suggest that biomechanically the transtendon and the PASTA Bridge6 techniques were equivalent. While the ultimate load and strain at repair sites are comparable, the PASTA Bridge is percutaneous and presents significantly less risk of complications. The PASTA Bridge6 uses a medial row horizontal mattress with a lateral row fixation to recreate the rotator cuff footprint. It has been postulated that reestablishing a higher percentage of the footprint can aide in tendon-bone healing, having valuable implications for both biological and clinical outcomes of the patient.3,4,14 Greater contact at the tendon-bone interface may allow more fibers to participate in the healing process.14 In their analysis of rotator cuff repair, Apreleva and colleagues14 asserted that more laterally placed suture anchors may increase the repair-site area. The lateral anchors of the PASTA Bridge help not only to increase the footprint and thereby the healing potential of the repair but also assist in taking pressure off the medial row anchors.

In their report on double-row rotator cuff repair, Lo and Burkhart3 suggest that double-row fixation is superior to single-row repairs for a variety of reasons. Primarily, double-row techniques increase the number of points of fixation, which will secondarily reduce both the stress and load at each suture point.3 This effect improves the overall strength of the repair construct. Use of the lateral anchor of the PASTA Bridge6 allows the medial anchors to act as pivot points. Placing the stress laterally, the configuration allows for movement and strain distribution without sacrificing the integrity of the repair. In our analysis, failure occurred by the tendon tearing mid-substance, humeral head breaking, tendon tearing at the repair site, and tearing at the musculotendinous junction (Figures 2-4). There was no instance of failure due to the construct itself indicating that the 2.4-mm medial anchors are more than adequate for the PASTA Bridge.6 When visually inspecting the samples after failure, there was no damage to the anchors or sutures. This observation indicates that the PASTA Bridge construct is remarkably strong and capable of withstanding excessive forces.

There were some potential limitations of this study. The small sample size modified the potential for identifying significant differences between the groups. A post-hoc power analysis revealed that a sample size of at least 20 matched pairs would be required to determine a significant difference between the 2 repair groups in strain at the repair site. We did not test this many pairs because the data was so similar after 6 matched pairs that it did not warrant continuing further. Additional research should be done with larger sample populations to evaluate the biomechanical efficacy of this technique further.

CONCLUSION

The PASTA Bridge6 creates a strong construct for repair of articular-sided partial-thickness tears of the supraspinatus. The data suggest the PASTA Bridge6 is biomechanically equivalent to the gold standard transtendon suture anchor repair. The PASTA Bridge6 is technically sound, percutaneous, and presents less risk of complications. It does not require arthroscopic knot tying and carries only minimal risk of damage to residual tissues. In our analysis, there were no failures of the actual construct, asserting that the PASTA Bridge6 is a strong, durable repair. The PASTA Bridge6 should be strongly considered by surgeons treating PASTA lesions.

ABSTRACT

Partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon avulsion (PASTA) tears are a common clinical problem that can require surgical intervention to reduce patient symptoms. Currently, no consensus has been reached regarding the optimal repair technique. The PASTA Bridge technique was developed by the senior author to address these types of lesions. A controlled laboratory study was performed comparing the PASTA Bridge with a standard transtendon rotator cuff repair to confirm its biomechanical efficacy. A 50% articular-sided partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon was created on 6 matched pairs of fresh-frozen cadaveric shoulders. For each matched pair, 1 humerus received a PASTA Bridge repair, whereas the contralateral side received a repair using a single suture anchor with a horizontal mattress suture. The ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness were determined from the load-displacement results for each sample. Video tracking software was used to determine the cyclic displacement of each sample at the articular margin and the repair site. Strain at the margin and repair site was then calculated using this collected data. There were no significant differences between the 2 repairs in ultimate load (P = .577), strain at the repair site (P = .355), or strain at the margin (P = .801). No instance of failure was due to the PASTA Bridge construct itself. The results of this study have established that the PASTA Bridge is biomechanically equivalent to the transtendon repair technique. The PASTA Bridge is technically easy, percutaneous, reproducible, and is associated with fewer risks.

Continue to: Rotator cuff tests...

Rotator cuff tears can be classified as full-thickness or partial-thickness; the latter being further divided into the bursal surface, articular-sided, or intratendinous tears. A study analyzing the anatomical distribution of partial tears found that approximately 50% of those at the rotator cuff footprint were articular-sided and predominantly involved the supraspinatus tendon.1 These partial-thickness articular-sided supraspinatus tendon avulsion tears have been coined “PASTA lesions.” Current treatment recommendations suggest that a debridement, a transtendon technique, or a “takedown” method of completing a partial tear and performing a full-thickness repair be utilized for partial-thickness rotator cuff repairs.

The primary goal of a partial cuff repair is to reestablish the tendon footprint at the humeral head. It has been argued that the “takedown” method alters the normal footprint and presents tension complications that can result in poor outcomes.2-5 Also, if the full-thickness repair fails, the patient is left with a full-thickness tear that could be more disabling. The trans-tendon technique has proven to be superior in this sense, demonstrating an improvement in both footprint contact and healing potential.3-5 This article aims to evaluate the biomechanical effectiveness of a new PASTA lesion repair technique, the PASTA Bridge,6 when compared with a traditional transtendon suture anchor repair.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BIOMECHANICAL OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE: PASTA BRIDGE REPAIR

A 17-gauge spinal needle was used to create a puncture in the supraspinatus tendon approximately 7.5 mm anterior to the centerline of the footprint and just medial to the simulated tear line. A 1.1-mm blunt Nitinol wire (Arthrex) was placed over the top of the spinal needle, and the spinal needle was removed. A 2.4-mm portal dilation instrument (Arthrex) was placed over the top of the 1.1 blunt wire (Arthrex) followed by the drill spear for the 2.4-mm BioComposite SutureTak (Arthrex). A pilot hole was created just medial to the simulated tear using the spear and a 1.8-mm drill followed by insertion of a 2.4-mm BioComposite SutureTak (Arthrex). This process was repeated approximately 5 mm posterior to the centerline of the footprint. A strand of suture from each anchor was tied in a manner similar to the “double pulley” method described by Lo and Burkhart.3 The opposing 2 limbs were tensioned to pull the knot taut over the repair site and fixed laterally with a 4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock (Arthrex) placed approximately 1 cm lateral to the greater tuberosity.

BIOMECHANICAL OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE: CONTROL (4.5-MM CORKSCREW FT GROUP)

A No. 11 scalpel was used to create a puncture in the tendon for a transtendon approach. A 4.5-mm titanium Corkscrew FT (Arthrex) was placed just medial to the beginning of the simulated tear. The No. 2 FiberWire (Arthrex) was passed anterior and posterior to the hole made for the transtendon approach. A horizontal mattress stitch was tied using a standard 2-handed knot technique.

BIOMECHANICAL ANALYSIS

The proximal humeri with intact supraspinatus tendons were removed from 6 matched pairs of fresh-frozen cadaver shoulders (3 males, 3 females; average age, 49 ± 12 years). The shaft of the humerus was potted in fiberglass resin. For each sample, a partial tear of the supraspinatus tendon was replicated by using a sharp blade to transect 50% of the medial side of the supraspinatus from the tuberosity.2,5 From each matched pair, 1 humerus was selected to receive a PASTA Bridge repair,6 and the contralateral repair was performed using one 4.5-mm titanium Corkscrew FT. Half of the samples of each repair were performed on the right humerus to avoid a mechanical bias. Each repair was performed by the same orthopedic surgeon.

Continue to: Biomechanical testing was...

Biomechanical testing was conducted using an INSTRON 8871 Axial Table Top Servo-hydraulic Testing System (INSTRON), with a 5 kN load cell attached to the crosshead. The system was calibrated using FastTrack software (AEC Software), and both the load and position controls were run through WaveMaker software (WaveMaker). Each sample was positioned on a fixed angle fixture and secured to the testing surface so that the direction of pull would be performed 45° to the humeral shaft. A custom fixture with inter-digitated brass clamps was attached to the crosshead, and dry ice was used to freeze the tendon to the clamp. The test setup can be seen in Figures 1A, 1B.

Each sample was pre-loaded to 10 N to remove slack from the system. Pre-loading was followed by cyclic loading between 10 N and 100 N,7-11 at 1 Hz, for 100 cycles. One-hundred cycles were chosen based on literature stating that the majority of the cyclic displacement occurs in the first 100 cycles.7-10 Post cycling, the samples were loaded to failure at a rate of 33 mm/sec.7-12 Load and position data were recorded at 500 Hz, and the mode of failure was noted for each sample.

Before loading, a soft-tissue marker was used to create individual marks on the supraspinatus in-line with the articular margin and lateral edge of the tuberosity (Figures 1A, 1B). The individual marks, a digital camera, and MaxTraq video tracking software (Innovision Systems) were used to calculate displacement and strain.

For each sample, the ultimate load, yield load, and stiffness were determined from the load-displacement results. Video tracking software was used to determine the cyclic displacement of each sample at both the articular margin (medial dots) and at the repair site. The strain at these 2 locations was calculated by dividing the cyclic displacement of the respective site by the distance between the site of interest and the lateral edge of the tuberosity (lateral marks) (ΔL/L). Paired t tests (α = 0.05) were used to determine if differences in ultimate load or strain between the 2 repairs were significant.

RESULTS

BIOMECHANICAL ANALYSIS

The results of the biomechanical testing are provided in the Table. There were no significant differences between the 2 repairs in ultimate load (P = .577), strain at the repair site (P = .355), or strain at the margin (P = .801). A post-hoc power analysis revealed that a sample size of at least 20 matched pairs would be needed to establish a significant difference for strain at the repair site. The modes of failure were mid-substance tendon tearing, the humeral head breaking, tearing at the musculotendinous junction, or the tendon tearing at the repair site. All 4 modes of failure occurred in at least 1 sample from both repair groups (Figures 2-4). Visual inspection of the samples post-testing revealed no damage to the anchors or sutures. A representative picture of the tendon tearing at the repair site can be seen in Figures 2A, 2B.

Continue to: The purpose of...

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the biomechanical strength of a new technique for PASTA repairs—the PASTA Bridge.6 After creation of a partial-thickness tear on a cadaveric model, we compared the PASTA Bridge technique6 with a standard transtendon suture anchor repair. We hypothesized that the PASTA Bridge would yield equivalent or better biomechanical properties including the ultimate load to failure and the degree of strain at different locations in the repair. Our results supported this hypothesis. The PASTA Bridge was biomechanically equivalent to transtendon repair.

For repairs of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears, 2 traditional techniques are transtendon repairs and the “takedown” method of completing a partial tear into a full tear with a subsequent repair.13 While clinical outcomes of the 2 methods suggest no superiority over the other,13 studies have demonstrated a biomechanical advantage with transtendon repairs. Repairs of PASTA lesions exhibit both lower strain and displacement of the repaired tendon compared with a full-thickness repair.2-5 Failure of the “takedown” method results in a full-thickness rotator cuff tear as opposed to a partial tear. This outcome can prove to be more debilitating for the patient. Furthermore, Mazzocca and colleagues5 illustrated that for partial tears >25% thickness, the cuff strain returned to the intact state once repaired.

Our data suggest that biomechanically the transtendon and the PASTA Bridge6 techniques were equivalent. While the ultimate load and strain at repair sites are comparable, the PASTA Bridge is percutaneous and presents significantly less risk of complications. The PASTA Bridge6 uses a medial row horizontal mattress with a lateral row fixation to recreate the rotator cuff footprint. It has been postulated that reestablishing a higher percentage of the footprint can aide in tendon-bone healing, having valuable implications for both biological and clinical outcomes of the patient.3,4,14 Greater contact at the tendon-bone interface may allow more fibers to participate in the healing process.14 In their analysis of rotator cuff repair, Apreleva and colleagues14 asserted that more laterally placed suture anchors may increase the repair-site area. The lateral anchors of the PASTA Bridge help not only to increase the footprint and thereby the healing potential of the repair but also assist in taking pressure off the medial row anchors.

In their report on double-row rotator cuff repair, Lo and Burkhart3 suggest that double-row fixation is superior to single-row repairs for a variety of reasons. Primarily, double-row techniques increase the number of points of fixation, which will secondarily reduce both the stress and load at each suture point.3 This effect improves the overall strength of the repair construct. Use of the lateral anchor of the PASTA Bridge6 allows the medial anchors to act as pivot points. Placing the stress laterally, the configuration allows for movement and strain distribution without sacrificing the integrity of the repair. In our analysis, failure occurred by the tendon tearing mid-substance, humeral head breaking, tendon tearing at the repair site, and tearing at the musculotendinous junction (Figures 2-4). There was no instance of failure due to the construct itself indicating that the 2.4-mm medial anchors are more than adequate for the PASTA Bridge.6 When visually inspecting the samples after failure, there was no damage to the anchors or sutures. This observation indicates that the PASTA Bridge construct is remarkably strong and capable of withstanding excessive forces.

There were some potential limitations of this study. The small sample size modified the potential for identifying significant differences between the groups. A post-hoc power analysis revealed that a sample size of at least 20 matched pairs would be required to determine a significant difference between the 2 repair groups in strain at the repair site. We did not test this many pairs because the data was so similar after 6 matched pairs that it did not warrant continuing further. Additional research should be done with larger sample populations to evaluate the biomechanical efficacy of this technique further.

CONCLUSION

The PASTA Bridge6 creates a strong construct for repair of articular-sided partial-thickness tears of the supraspinatus. The data suggest the PASTA Bridge6 is biomechanically equivalent to the gold standard transtendon suture anchor repair. The PASTA Bridge6 is technically sound, percutaneous, and presents less risk of complications. It does not require arthroscopic knot tying and carries only minimal risk of damage to residual tissues. In our analysis, there were no failures of the actual construct, asserting that the PASTA Bridge6 is a strong, durable repair. The PASTA Bridge6 should be strongly considered by surgeons treating PASTA lesions.

1. Schaeffeler C, Mueller D, Kirchhoff C, Wolf P, Rummeny EJ, Woertler K. Tears at the rotator cuff footprint: prevalence and imaging characteristics in 305 MR arthrograms of the shoulder. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1477-1484. doi:10.1007/s00330-011-2066-x.

2. Gonzalez-Lomas G, Kippe MA, Brown GD, et al. In situ transtendon repair outperforms tear completion and repair for partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):722-728.

3. Lo IKY, Burkhart SS. Transtendon arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness, articular surface tears of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2004; 20(2):214-220. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.042.

4. Mazzocca AD, Millett PJ, Guanche CA, Santangelo SA, Arciero RA. Arthroscopic single-row versus double-row suture anchor rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(12):1861-1868.

5. Mazzocca AD, Rincon LM, O’Connor RW, et al. Intra-articular partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: analysis of injured and repaired strain behavior. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):110-116. doi:10.1177/0363546507307502.

6. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. The PASTA bridge: a technique for the arthroscopic repair of PASTA lesions. Arthrosc Tech. In Press. Epub 2017 Sept 18.

7. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing and ultimate failure strength of biodegradable glenoid anchors. Arthroscopy. 2008; 24(2):224-228. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.011.

8. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing of biodegradable suture anchors containing 2 high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2007; 23(4):355-360. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2006.12.009.

9. Barber FA, Feder SM, Burkhart SS, Ahrens J. The relationship of suture anchor failure and bone density to proximal humerus location: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(3):340-345. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.12.007.

10. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Richards DP. Sutures and suture anchors: update 2003. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):985-990.

11. Burkhart SS, Johnson TC, Wirth MA, Athanasiou KA. Cyclic loading of transosseous rotator cuff repairs: tension overload as a possible cause of failure. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(2):172-176. doi:10.1016/S0749-8063(97)90151-1.

12. Hecker AT, Shea M, Hayhurst JO, Myers ER, Meeks LW, Hayes WC. Pull-out strength of suture anchors for rotator cuff and bankart lesion repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1993; 21(6):874-879.

13. Strauss EJ, Salata MJ, Kercher J, et al. The arthroscopic management of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):568-580. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.09.019.

14. Apreleva M, Özbaydar M, Fitzgibbons PG, Warner JJP. Rotator cuff tears: the effect of the reconstruction method on three-dimensional repair-site area. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):519-526. doi:10.1053/jars.2002.32930.

1. Schaeffeler C, Mueller D, Kirchhoff C, Wolf P, Rummeny EJ, Woertler K. Tears at the rotator cuff footprint: prevalence and imaging characteristics in 305 MR arthrograms of the shoulder. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1477-1484. doi:10.1007/s00330-011-2066-x.

2. Gonzalez-Lomas G, Kippe MA, Brown GD, et al. In situ transtendon repair outperforms tear completion and repair for partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(5):722-728.

3. Lo IKY, Burkhart SS. Transtendon arthroscopic repair of partial-thickness, articular surface tears of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2004; 20(2):214-220. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2003.11.042.

4. Mazzocca AD, Millett PJ, Guanche CA, Santangelo SA, Arciero RA. Arthroscopic single-row versus double-row suture anchor rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(12):1861-1868.

5. Mazzocca AD, Rincon LM, O’Connor RW, et al. Intra-articular partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: analysis of injured and repaired strain behavior. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):110-116. doi:10.1177/0363546507307502.

6. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. The PASTA bridge: a technique for the arthroscopic repair of PASTA lesions. Arthrosc Tech. In Press. Epub 2017 Sept 18.

7. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing and ultimate failure strength of biodegradable glenoid anchors. Arthroscopy. 2008; 24(2):224-228. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2007.08.011.

8. Barber FA, Coons DA, Ruiz-Suarez M. Cyclic load testing of biodegradable suture anchors containing 2 high-strength sutures. Arthroscopy. 2007; 23(4):355-360. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2006.12.009.

9. Barber FA, Feder SM, Burkhart SS, Ahrens J. The relationship of suture anchor failure and bone density to proximal humerus location: a cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(3):340-345. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.12.007.

10. Barber FA, Herbert MA, Richards DP. Sutures and suture anchors: update 2003. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):985-990.

11. Burkhart SS, Johnson TC, Wirth MA, Athanasiou KA. Cyclic loading of transosseous rotator cuff repairs: tension overload as a possible cause of failure. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(2):172-176. doi:10.1016/S0749-8063(97)90151-1.

12. Hecker AT, Shea M, Hayhurst JO, Myers ER, Meeks LW, Hayes WC. Pull-out strength of suture anchors for rotator cuff and bankart lesion repairs. Am J Sports Med. 1993; 21(6):874-879.

13. Strauss EJ, Salata MJ, Kercher J, et al. The arthroscopic management of partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):568-580. doi:10.1016/j.arthro.2010.09.019.

14. Apreleva M, Özbaydar M, Fitzgibbons PG, Warner JJP. Rotator cuff tears: the effect of the reconstruction method on three-dimensional repair-site area. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):519-526. doi:10.1053/jars.2002.32930.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- The PASTA Bridge is biomechanically equivalent to the gold-standard transtendon repair technique.

- The configuration is a double-row repair, increasing the number of fixation points.

- The lateral anchor of the PASTA Bridge assumes the stress of the repair, allowing the medial anchors to act as pivot points.

- The PASTA Bridge is strong and capable of withstanding excessive forces.

- The PASTA Bridge poses less risk of complication.

Superior Capsular Reconstruction: Clinical Outcomes After Minimum 2-Year Follow-Up

Take-Home Points

- The SCR is a viable treatment option for massive, irreparable RCTs.

- Arm position and exact measurement between anchors will help ensure proper graft tensioning.

- Anterior and posterior tension and margin convergence are critical to stabilizing the graft.

- Acromial-humeral distance, ASES, and VAS scores are improved and maintained over long-term follow-up.

- The dermal allograft should be 3.0 mm or thicker.

Conventional treatments for irreparable massive rotator cuff tears (RCTs) have ranged from nonoperative care to débridement and biceps tenotomy,1,2 partial cuff repair,3,4 bridging patch grafts,5 tendon transfers,6,7 and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA).8,9 Superior capsular reconstruction (SCR), originally described by Mihata and colleagues,10 has been developed as an alternative to these interventions. Dr. Hirahara modified the technique to use dermal allograft instead of fascia lata autograft.10,11

Biomechanical analysis has confirmed the integral role of the superior capsule in shoulder function.10,12-14 In the presence of a massive RCT, the humeral head migrates superiorly, causing significant pain and functional deficits, such as pseudoparalysis. It is theorized that reestablishing this important stabilizer—centering the humeral head in the glenoid and allowing the larger muscles to move the arm about a proper fulcrum—improves function and decreases pain.

Using ultrasonography (US), radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), clinical outcome scores, and a visual analog scale (VAS) for pain, we prospectively evaluated minimum 2-year clinical outcomes of performing SCR with dermal allograft for irreparable RCTs.

Methods

Except where noted otherwise, all products mentioned in this section were made by Arthrex.

Surgical Technique

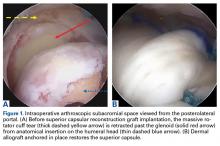

The surgical technique used here was described by Hirahara and Adams.11 ArthroFlex dermal allograft was attached to the greater tuberosity and the glenoid, creating a superior restraint that replaced the anatomical superior capsule (Figures 1A, 1B). Some cases included biceps tenotomy, subscapularis repair, or infraspinatus repair.

Medial fixation was obtained with a PASTA (partial articular supraspinatus tendon avulsion) bridge-type construct15 that consisted of two 3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak anchors (placed medially on the glenoid rim, medial to the labrum) and a 3.5-mm BioComposite Vented SwiveLock. In some cases, a significant amount of tissue was present medially, and the third anchor was not used; instead, a double surgeon knot was used to fixate the double pulley medially.

Posterior margin convergence (PMC) was performed in all cases. Anterior margin convergence (AMC) was performed in only 3 cases.

Clinical Evaluation

All patients who underwent SCR were followed prospectively, and all signed an informed consent form. Between 2014 and the time of this study, 9 patients had surgery with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Before surgery, all patients received a diagnosis of full-thickness RCT with decreased acromial-humeral distance (AHD). One patient had RTSA 18 months after surgery, did not reach the 2-year follow-up, and was excluded from the data analysis. Patients were clinically evaluated on the 100-point American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) shoulder index and on a 10-point VAS for pain—before surgery, monthly for the first 6 months after surgery, then every 6 months until 2 years after surgery, and yearly thereafter. These patients were compared with Dr. Hirahara’s historical control patients, who had undergone repair of massive RCTs. Mean graft size was calculated and reported. Cases were separated and analyzed on the basis of whether AMC was performed. Student t tests were used to determine statistical differences between study patients’ preoperative and postoperative scores, between study and historical control patients, and between patients who had AMC performed and those who did not (P < .05).

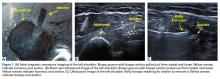

Imaging

For all SCR patients, preoperative and postoperative radiographs were obtained in 2 planes: anterior-posterior with arm in neutral rotation, and scapular Y. On anteroposterior radiographs, AHD was measured from the most proximal aspect of the humeral head in a vertical line to the most inferior portion of the acromion (Figures 2A, 2B).

Results

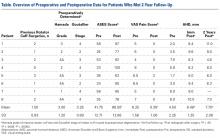

The Table provides an overview of the study results. Eight patients (6 men, 2 women) met the final inclusion criteria for postoperative ASES and VAS data analysis.

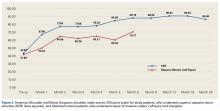

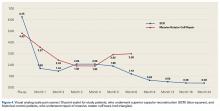

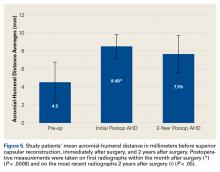

AHD was measured on a standard anteroposterior radiograph in neutral rotation. The Hamada grading scale16 was used to classify the massive RCTs before and after surgery. Before surgery, 4 were grade 4A, 1 grade 3, 2 grade 2, and 1 grade 1; immediately after surgery, all were grade 1 (AHD, ≥6 mm). Two years after surgery, 1 patient had an AHD of 4.6 mm after a failure caused by a fall. Mean (SD) preoperative AHD was 4.50 (2.25) mm (range, 1.7-7.9 mm). Radiographs obtained immediately (mean, 1.22 months; range, 1 day-2.73 months) after surgery showed AHD was significantly (P < .0008) increased (mean, 8.48 mm; SD, 1.25 mm; range, 6.0-10.0 mm) (Figure 5).

Mean graft size was 2.9 mm medial × 3.6 mm lateral × 5.4 mm anterior × 5.4 mm posterior. Three patients had AMC performed. There was a significant (P < .05) difference in ASES scores between patients who had AMC performed (93) and those who did not (77).

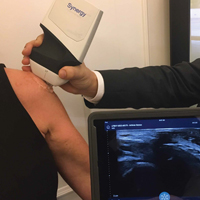

Ultrasonography

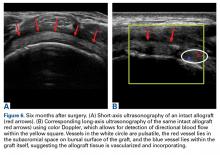

Two weeks to 2 months after surgery, all patients had an intact capsular graft and no pulsatile vessels on US. Between 4 months and 10 months, US showed the construct intact laterally in all cases, a pulsatile vessel in the graft at the tuberosity (evidence of blood flow) in 4 of 5 cases, and a pulsatile vessel hypertrophied in 2 cases (Figures 6A, 6B).

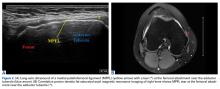

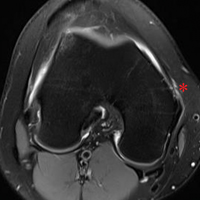

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Before surgery, 4 patients had Goutallier17 stage 4 rotator cuff muscle degeneration, 2 had stage 3 degeneration, and 2 had stage 2 degeneration. Throughout the follow-up period, US was as effective as MRI in determining graft integrity, graft thickness, and greater tuberosity fixation. Therefore, the SCRs were assessed primarily with US. MRI was ordered only if a failure was suspected or if the patient had some form of trauma. A total of 7 MRIs were ordered for 5 of the 8 patients in the study. The graft was intact in 4 of the 5 (Figures 7A-7C) and ruptured in the fifth.

Discussion

Mihata and colleagues10 published 2-year data for their reconstructive procedure with fascia lata autograft. In a modification of their procedure, Dr. Hirahara used dermal allograft to recreate the superior capsule.11 The results of the present 2-year study mirror the clinical outcomes reported by Mihata and colleagues10 and confirm that SCR improves functional outcomes and increases AHD regardless of graft type used.

The outcomes of the SCR patients in our study were significantly better than the outcomes of the historical control patients, who underwent repair of massive RCTs. Although there was no significant difference in the 2 groups’ ASES scores, the control patients had significantly higher postoperative VAS pain scores. We think that, as more patients undergo SCR and the population sample increases, we will see a significant difference in ASES scores as well (our SCR patients already showed a trend toward improved ASES scores).

Compared with RTSA, SCR has fewer risks and fewer complications and does not limit further surgical options.8,9,18 The 9 patients who had surgery with a minimum 2-year follow-up in our study had 4 complications. Six months after surgery, 1 patient fell and tore the infraspinatus and subscapularis muscles. Outcomes continued to improve, and no issues were reported, despite a decrease in AHD, from 8 mm immediately after surgery to 4.6 mm 2 years after surgery.

Two patients were in motor vehicle accidents. In 1 case, the accident occurred about 2 months after surgery. This patient also sustained a possible injury in a fall after receiving general anesthesia for a dental procedure. After having done very well the preceding months, the patient now reported increasing pain and dysfunction. MRI showed loss of glenoid fixation. Improved ASES and VAS pain scores were maintained throughout the follow-up period. AHD was increased at 13 months and mildly decreased at 2 years. Glenoid fixation was obtained with 2 anchors and a double surgeon knot. When possible, however, it is best to add an anchor and double-row fixation, as 3 anchors and a double-row construct are biomechanically stronger.19-24

The other motor vehicle accident occurred about 23 months after surgery. Two months later, a graft rupture was found on US and MRI, but the patient was maintaining full range of motion, AHD, and improved strength. The 1.5-mm graft in this patient was thinner than the 3.5-mm grafts in the rest of the study group. This was the only patient who developed a graft rupture rather than loss of fixation.

If only patients with graft thickness >3.0 mm are included in the data analysis, mean ASES score rises to 89.76, and mean VAS pain score drops to 0. Therefore, we argue against using a graft thinner than 3.5 mm. Our excellent study results indicate that larger grafts are unnecessary. Mihata and colleagues10 used fascia lata grafts of 6 mm to 8 mm. Ultimate load to failure is significantly higher for dermal allograft than for fascia lata graft.25 In SCR, the stronger dermal allograft withstands applied forces and repeated deformations and has excellent clinical outcomes.

Only 1 patient had a failure that required RTSA. VAS pain scores were lower and ASES scores were improved the first year after surgery, but then function deteriorated. The patient said there was no specific precipitating incident. Computed tomography arthrogram, ordered to assess the construct, showed anterior and superior subluxation of the humeral head, even with an intact subscapularis tendon—an indication of underlying instability, which most likely caused the failure. Eighteen months after surgery, the patient was able to undergo RTSA. On further evaluation of this patient’s procedure, it was determined that the graft needed better fixation anteriorly.

Mihata and colleagues10,12,14 indicated that AMC was unnecessary, and our procedure did not require it. However, data in our prospective evaluation began showing improved outcomes with AMC. As dermal allograft is more elastic than fascia lata autograft,25 we concluded that graft tensioning is key to the success of this procedure. Graft tension depends on many factors, including exact measurement of the distances between the anchors to punch holes in the graft, arm position to set the relationship between the anchor distances, and AMC and PMC. We recommend placing the arm in neutral rotation, neutral flexion, and abduction with the patient at rest, based on the size of the patient’s latissimus dorsi. Too much abduction causes overtensioning, and excess rotation or flexion-extension changes the distance between the glenoid and the greater tuberosity asymmetrically, from anterior to posterior. With the arm in neutral position, distances between anchors are accurately measured, and these measurements are used to determine graft size.

Graft tension is also needed to control the amount of elasticity allowed by the graft and thereby maintain stability, as shown by the Poisson ratio, the ratio of transverse contraction to longitudinal extension on a material in the presence of a stretching force. As applied to SCR, it is the ratio of mediolateral elasticity to anteroposterior deformation or constraint. If the graft is appropriately secured in the anteroposterior direction by way of ACM and PMC, elongation in the medial-lateral direction will be limited—reducing the elasticity of the graft, improving overall stability, and ultimately producing better clinical outcomes. This issue was discussed by Burkhart and colleagues26 with respect to the “rotator cable complex,” which now might be best described as the “rotator-capsule cable complex.” In our study, this phenomenon was evident in the finding that patients who had AMC performed did significantly better than patients who did not have AMC performed. The ability of dermal allograft to deform in these dimensions without failure while allowing excellent range of motion makes dermal allograft an exceptional choice for grafting during SCR. Mihata25 also found dermal allograft had a clear advantage in providing better range of motion, whereas fascia lata autograft resulted in a stiffer construct.

Dermal allograft can also incorporate into the body and transform into host tissue. The literature has described musculoskeletal US as an effective diagnostic and interventional tool.27-31 We used it to evaluate graft size, patency, and viability. As can be seen on US, the native rotator cuff does not have any pulsatile vessels and is fed by capillary flow. Dermal allograft has native vasculature built into the tissue. After 4 months to 8 months, presence of pulsatile vessels within the graft at the greater tuberosity indicates clear revascularization and incorporation of the tissue (Figure 6B). Disappearance of pulsatile vessels on US after 1 year indicates transformation to a stabilizing structure analogous to capsule or ligament with capillary flow. US also showed graft hypertrophy after 2 years, supporting a finding of integration and growth.

Conclusion

In the past, patients with irreparable massive RCTs had few good surgical management options, RTSA being the most definitive. SCR is technically challenging and requires use of specific implantation methods but can provide patients with outstanding relief. Our clinical data showed that technically well executed SCR effectively restores the superior restraints in the glenohumeral joint and thereby increases function and decreases pain in patients with irreparable massive RCTs, even after 2 years.

1 Lee BG, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Results of arthroscopic decompression and tuberoplasty for irreparable massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(10):1341-1350.

2. Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, Poetzl W, Steinbeck J, Marquardt B. Arthroscopic debridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(7):743-748.

3. Kim SJ, Lee IS, Kim SH, Lee WY, Chun YM. Arthroscopic partial repair of irreparable large to massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):761-768.

4. Wellmann M, Lichtenberg S, da Silva G, Magosch P, Habermeyer P. Results of arthroscopic partial repair of large retracted rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(8):1275-1282.

5. Mori D, Funakoshi N, Yamashita F. Arthroscopic surgery of irreparable large or massive rotator cuff tears with low-grade fatty degeneration of the infraspinatus: patch autograft procedure versus partial repair procedure. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(12):1911-1921.

6. Gavriilidis I, Kircher J, Mogasch P, Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P. Pectoralis major transfer for the treatment of irreparable anterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Int Orthop. 2010;34(5):689-694.

7. Grimberg J, Kany J, Valenti P, Amaravathi R, Ramalingam AT. Arthroscopic-assisted latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(4):599-607.

8. Bedi A, Dines J, Warren RF, Dines DM. Massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(9):1894-1908.

9. Ek ET, Neukom L, Catanzaro S, Gerber C. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears in patients younger than 65 years old: results after five to fifteen years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(9):1199-1208.

10. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(3):459-470.

11. Hirahara AM, Adams CR. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction for treatment of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4(6):e637-e641.

12. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Kahn T, Goldberg I, Neo M, Lee TQ. Biomechanical role of capsular continuity in superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable tears of the supraspinatus tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1423-1430.

13. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Ishihara Y, et al. Biomechanical analysis of articular-sided partial-thickness rotator cuff tear and repair. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(2):439-446.

14. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2248-2255.

15. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. The PASTA bridge: a technique for the arthroscopic repair of PASTA lesions [published online ahead of print September 18, 2017]. Arthrosc Tech. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eats.2017.06.022.

16. Hamada K, Yamanaka K, Uchiyama Y, Mikasa T, Mikasa M. A radiographic classification of massive rotator cuff tear arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2452-2460.

17. Oh JH, Kim SH, Choi JA, Kim Y, Oh CH. Reliability of the grading system for fatty degeneration of rotator cuff muscles. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(6):1558-1564.

18. Boileau P, Sinnerton RJ, Chuinard C, Walch G. Arthroplasty of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(5):562-575.

19. Apreleva M, Özbaydar M, Fitzgibbons PG, Warner JJ. Rotator cuff tears: the effect of the reconstruction method on three-dimensional repair site area. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(5):519-526.

20. Baums MH, Spahn G, Steckel H, Fischer A, Schultz W, Klinger HM. Comparative evaluation of the tendon–bone interface contact pressure in different single- versus double-row suture anchor repair techniques. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(12):1466-1472.

21. Lo IK, Burkhart SS. Double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: re-establishing the footprint of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(9):1035-1042.

22. Mazzocca AD, Millett PJ, Guanche CA, Santangelo SA, Arciero RA. Arthroscopic single-row versus double-row suture anchor rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(12):1861-1868.

23. Pauly S, Fiebig D, Kieser B, Albrecht B, Schill A, Scheibel M. Biomechanical comparison of four double-row speed-bridging rotator cuff repair techniques with or without medial or lateral row enhancement. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(12):2090-2097.

24. Pauly S, Kieser B, Schill A, Gerhardt C, Scheibel M. Biomechanical comparison of 4 double-row suture-bridging rotator cuff repair techniques using different medial-row configurations. Arthroscopy. 2010;26(10):1281-1288.

25. Mihata T. Superior capsule reconstruction using human dermal allograft: a biomechanical cadaveric study. Presentation at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; March 1-5, 2016; Orlando, FL.

26. Burkhart SS, Esch JC, Jolson RS. The rotator crescent and rotator cable: an anatomic description of the shoulder’s “suspension bridge.” Arthroscopy. 1993;9(6):611-616.

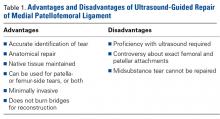

27. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous reconstruction of the anterolateral ligament: surgical technique and case report. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):418-422, 460.

28. Hirahara AM, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous repair of medial patellofemoral ligament: surgical technique and outcomes. Am J Orthop. 2017;46(3):152-157.

29. Hirahara AM, Mackay G, Andersen WJ. Ultrasound-guided InternalBrace of the medial collateral ligament. Arthrosc Tech. Accepted for publication.

30. Hirahara AM, Panero AJ. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 3: interventional and procedural uses. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):440-445.

31. Panero AJ, Hirahara AM. A guide to ultrasound of the shoulder, part 2: the diagnostic evaluation. Am J Orthop. 2016;45(4):233-238.

Take-Home Points

- The SCR is a viable treatment option for massive, irreparable RCTs.

- Arm position and exact measurement between anchors will help ensure proper graft tensioning.

- Anterior and posterior tension and margin convergence are critical to stabilizing the graft.

- Acromial-humeral distance, ASES, and VAS scores are improved and maintained over long-term follow-up.

- The dermal allograft should be 3.0 mm or thicker.

Conventional treatments for irreparable massive rotator cuff tears (RCTs) have ranged from nonoperative care to débridement and biceps tenotomy,1,2 partial cuff repair,3,4 bridging patch grafts,5 tendon transfers,6,7 and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA).8,9 Superior capsular reconstruction (SCR), originally described by Mihata and colleagues,10 has been developed as an alternative to these interventions. Dr. Hirahara modified the technique to use dermal allograft instead of fascia lata autograft.10,11

Biomechanical analysis has confirmed the integral role of the superior capsule in shoulder function.10,12-14 In the presence of a massive RCT, the humeral head migrates superiorly, causing significant pain and functional deficits, such as pseudoparalysis. It is theorized that reestablishing this important stabilizer—centering the humeral head in the glenoid and allowing the larger muscles to move the arm about a proper fulcrum—improves function and decreases pain.

Using ultrasonography (US), radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), clinical outcome scores, and a visual analog scale (VAS) for pain, we prospectively evaluated minimum 2-year clinical outcomes of performing SCR with dermal allograft for irreparable RCTs.

Methods

Except where noted otherwise, all products mentioned in this section were made by Arthrex.

Surgical Technique

The surgical technique used here was described by Hirahara and Adams.11 ArthroFlex dermal allograft was attached to the greater tuberosity and the glenoid, creating a superior restraint that replaced the anatomical superior capsule (Figures 1A, 1B). Some cases included biceps tenotomy, subscapularis repair, or infraspinatus repair.

Medial fixation was obtained with a PASTA (partial articular supraspinatus tendon avulsion) bridge-type construct15 that consisted of two 3.0-mm BioComposite SutureTak anchors (placed medially on the glenoid rim, medial to the labrum) and a 3.5-mm BioComposite Vented SwiveLock. In some cases, a significant amount of tissue was present medially, and the third anchor was not used; instead, a double surgeon knot was used to fixate the double pulley medially.

Posterior margin convergence (PMC) was performed in all cases. Anterior margin convergence (AMC) was performed in only 3 cases.

Clinical Evaluation

All patients who underwent SCR were followed prospectively, and all signed an informed consent form. Between 2014 and the time of this study, 9 patients had surgery with a minimum 2-year follow-up. Before surgery, all patients received a diagnosis of full-thickness RCT with decreased acromial-humeral distance (AHD). One patient had RTSA 18 months after surgery, did not reach the 2-year follow-up, and was excluded from the data analysis. Patients were clinically evaluated on the 100-point American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) shoulder index and on a 10-point VAS for pain—before surgery, monthly for the first 6 months after surgery, then every 6 months until 2 years after surgery, and yearly thereafter. These patients were compared with Dr. Hirahara’s historical control patients, who had undergone repair of massive RCTs. Mean graft size was calculated and reported. Cases were separated and analyzed on the basis of whether AMC was performed. Student t tests were used to determine statistical differences between study patients’ preoperative and postoperative scores, between study and historical control patients, and between patients who had AMC performed and those who did not (P < .05).

Imaging

For all SCR patients, preoperative and postoperative radiographs were obtained in 2 planes: anterior-posterior with arm in neutral rotation, and scapular Y. On anteroposterior radiographs, AHD was measured from the most proximal aspect of the humeral head in a vertical line to the most inferior portion of the acromion (Figures 2A, 2B).

Results

The Table provides an overview of the study results. Eight patients (6 men, 2 women) met the final inclusion criteria for postoperative ASES and VAS data analysis.

AHD was measured on a standard anteroposterior radiograph in neutral rotation. The Hamada grading scale16 was used to classify the massive RCTs before and after surgery. Before surgery, 4 were grade 4A, 1 grade 3, 2 grade 2, and 1 grade 1; immediately after surgery, all were grade 1 (AHD, ≥6 mm). Two years after surgery, 1 patient had an AHD of 4.6 mm after a failure caused by a fall. Mean (SD) preoperative AHD was 4.50 (2.25) mm (range, 1.7-7.9 mm). Radiographs obtained immediately (mean, 1.22 months; range, 1 day-2.73 months) after surgery showed AHD was significantly (P < .0008) increased (mean, 8.48 mm; SD, 1.25 mm; range, 6.0-10.0 mm) (Figure 5).

Mean graft size was 2.9 mm medial × 3.6 mm lateral × 5.4 mm anterior × 5.4 mm posterior. Three patients had AMC performed. There was a significant (P < .05) difference in ASES scores between patients who had AMC performed (93) and those who did not (77).

Ultrasonography

Two weeks to 2 months after surgery, all patients had an intact capsular graft and no pulsatile vessels on US. Between 4 months and 10 months, US showed the construct intact laterally in all cases, a pulsatile vessel in the graft at the tuberosity (evidence of blood flow) in 4 of 5 cases, and a pulsatile vessel hypertrophied in 2 cases (Figures 6A, 6B).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Before surgery, 4 patients had Goutallier17 stage 4 rotator cuff muscle degeneration, 2 had stage 3 degeneration, and 2 had stage 2 degeneration. Throughout the follow-up period, US was as effective as MRI in determining graft integrity, graft thickness, and greater tuberosity fixation. Therefore, the SCRs were assessed primarily with US. MRI was ordered only if a failure was suspected or if the patient had some form of trauma. A total of 7 MRIs were ordered for 5 of the 8 patients in the study. The graft was intact in 4 of the 5 (Figures 7A-7C) and ruptured in the fifth.

Discussion

Mihata and colleagues10 published 2-year data for their reconstructive procedure with fascia lata autograft. In a modification of their procedure, Dr. Hirahara used dermal allograft to recreate the superior capsule.11 The results of the present 2-year study mirror the clinical outcomes reported by Mihata and colleagues10 and confirm that SCR improves functional outcomes and increases AHD regardless of graft type used.

The outcomes of the SCR patients in our study were significantly better than the outcomes of the historical control patients, who underwent repair of massive RCTs. Although there was no significant difference in the 2 groups’ ASES scores, the control patients had significantly higher postoperative VAS pain scores. We think that, as more patients undergo SCR and the population sample increases, we will see a significant difference in ASES scores as well (our SCR patients already showed a trend toward improved ASES scores).

Compared with RTSA, SCR has fewer risks and fewer complications and does not limit further surgical options.8,9,18 The 9 patients who had surgery with a minimum 2-year follow-up in our study had 4 complications. Six months after surgery, 1 patient fell and tore the infraspinatus and subscapularis muscles. Outcomes continued to improve, and no issues were reported, despite a decrease in AHD, from 8 mm immediately after surgery to 4.6 mm 2 years after surgery.

Two patients were in motor vehicle accidents. In 1 case, the accident occurred about 2 months after surgery. This patient also sustained a possible injury in a fall after receiving general anesthesia for a dental procedure. After having done very well the preceding months, the patient now reported increasing pain and dysfunction. MRI showed loss of glenoid fixation. Improved ASES and VAS pain scores were maintained throughout the follow-up period. AHD was increased at 13 months and mildly decreased at 2 years. Glenoid fixation was obtained with 2 anchors and a double surgeon knot. When possible, however, it is best to add an anchor and double-row fixation, as 3 anchors and a double-row construct are biomechanically stronger.19-24

The other motor vehicle accident occurred about 23 months after surgery. Two months later, a graft rupture was found on US and MRI, but the patient was maintaining full range of motion, AHD, and improved strength. The 1.5-mm graft in this patient was thinner than the 3.5-mm grafts in the rest of the study group. This was the only patient who developed a graft rupture rather than loss of fixation.

If only patients with graft thickness >3.0 mm are included in the data analysis, mean ASES score rises to 89.76, and mean VAS pain score drops to 0. Therefore, we argue against using a graft thinner than 3.5 mm. Our excellent study results indicate that larger grafts are unnecessary. Mihata and colleagues10 used fascia lata grafts of 6 mm to 8 mm. Ultimate load to failure is significantly higher for dermal allograft than for fascia lata graft.25 In SCR, the stronger dermal allograft withstands applied forces and repeated deformations and has excellent clinical outcomes.