User login

Vulvar syringoma

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

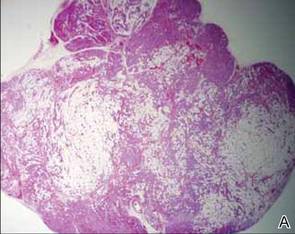

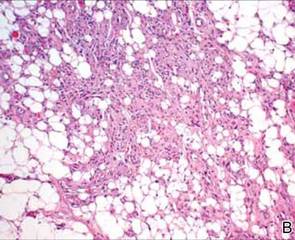

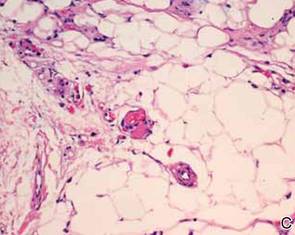

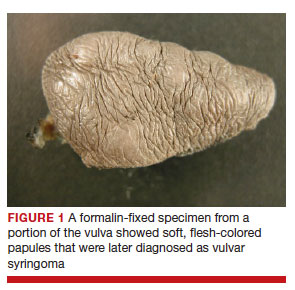

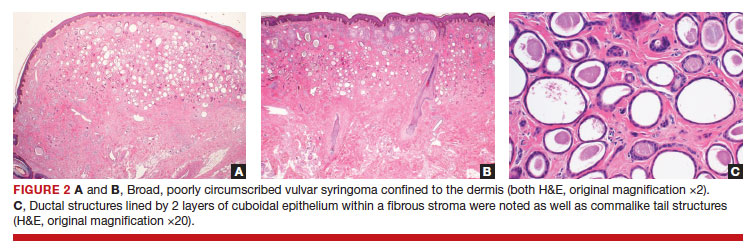

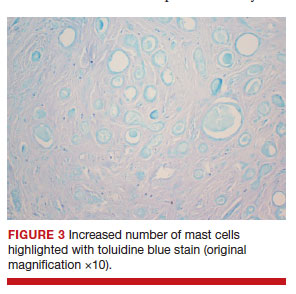

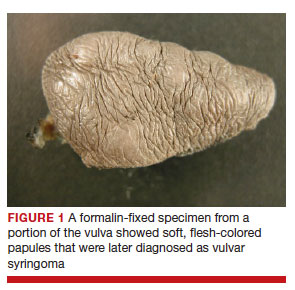

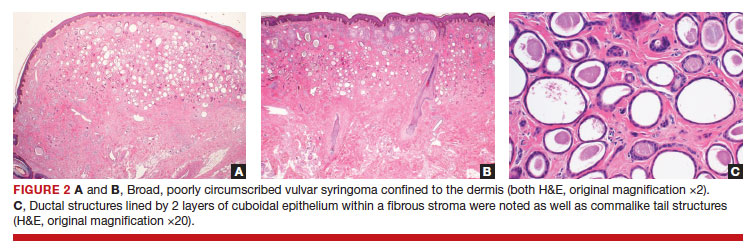

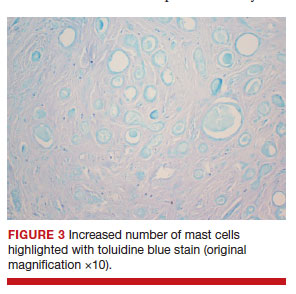

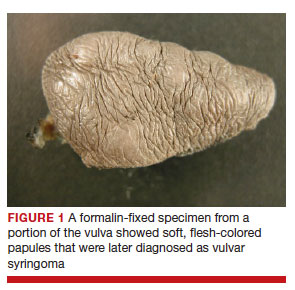

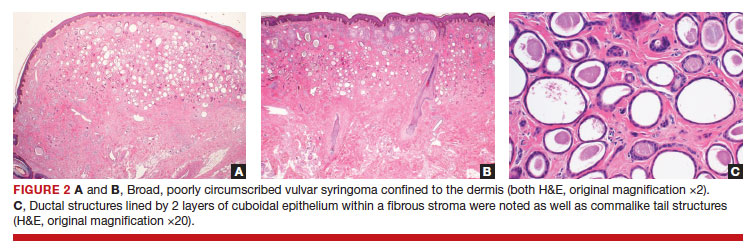

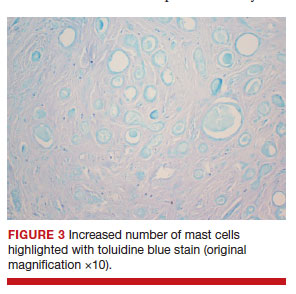

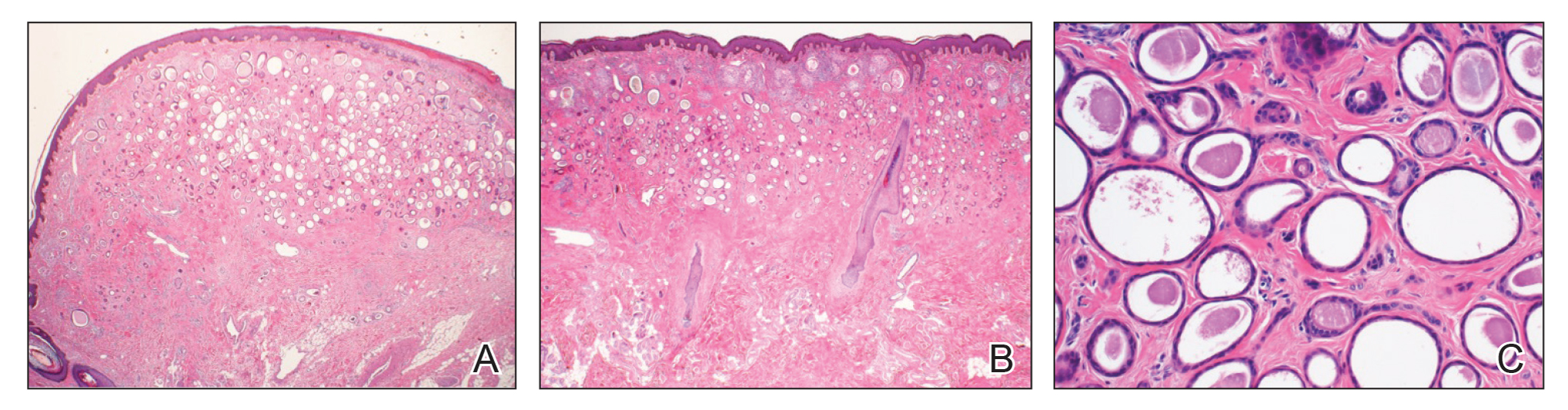

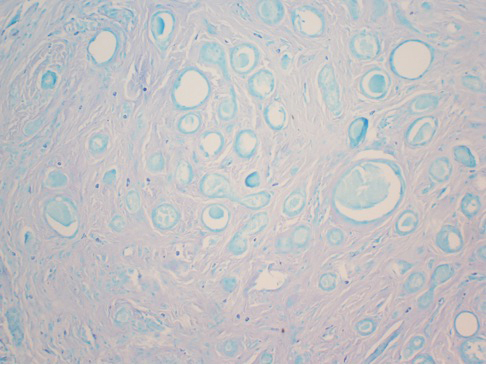

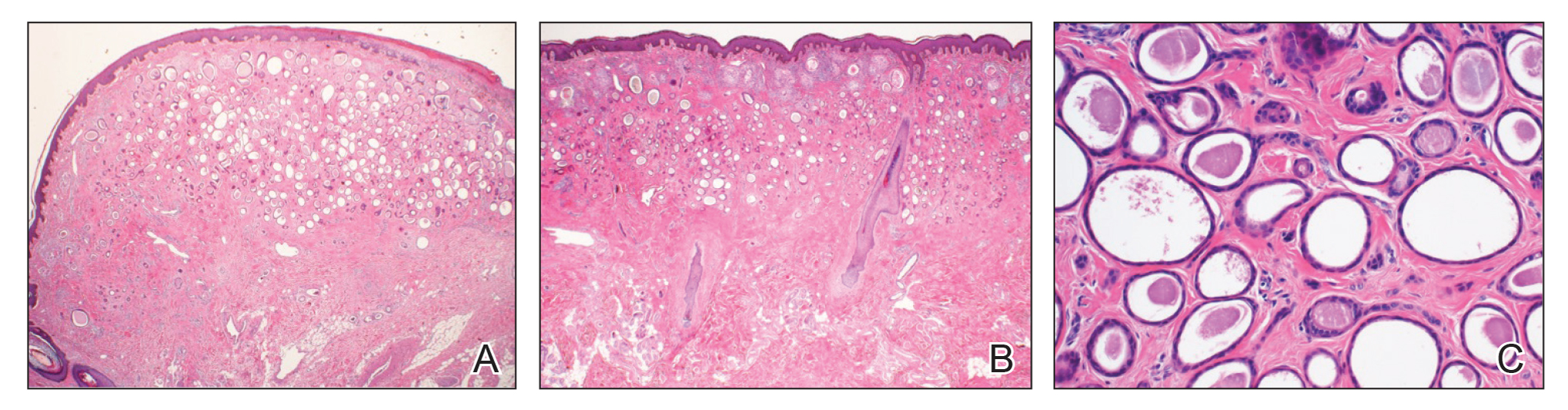

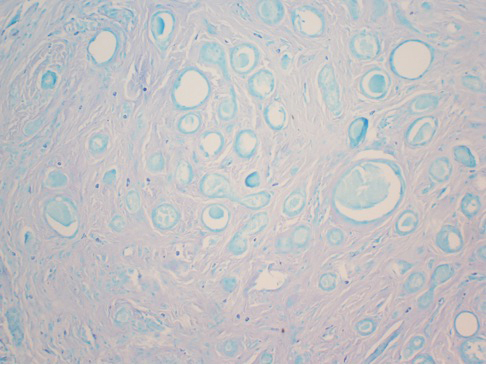

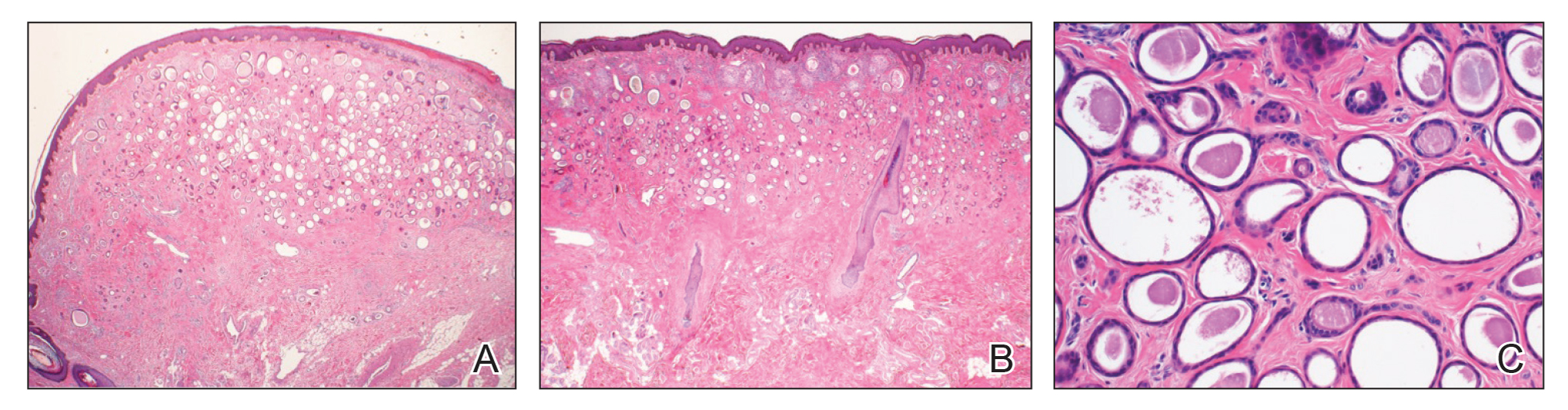

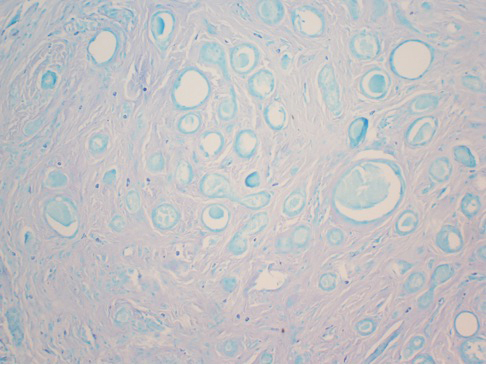

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (FIGURE 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (FIGURE 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulvar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (FIGURES 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3).Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems. ●

- Ensure adequate depth of biopsy to assist in the histologic diagnosis of syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma.

- Vulvar syringomas also may contribute to notable pruritus and ultimately be the underlying etiology for secondary skin changes leading to a lichen simplex chronicus–like phenotype

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas DermoSifiliográficas. 2008; 99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995; 22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinomaaggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369372.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (FIGURE 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (FIGURE 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulvar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (FIGURES 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3).Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems. ●

- Ensure adequate depth of biopsy to assist in the histologic diagnosis of syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma.

- Vulvar syringomas also may contribute to notable pruritus and ultimately be the underlying etiology for secondary skin changes leading to a lichen simplex chronicus–like phenotype

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (FIGURE 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (FIGURE 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulvar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (FIGURES 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (FIGURE 3).Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems. ●

- Ensure adequate depth of biopsy to assist in the histologic diagnosis of syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma.

- Vulvar syringomas also may contribute to notable pruritus and ultimately be the underlying etiology for secondary skin changes leading to a lichen simplex chronicus–like phenotype

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas DermoSifiliográficas. 2008; 99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995; 22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinomaaggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369372.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas DermoSifiliográficas. 2008; 99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995; 22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinomaaggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369372.

Vulvar Syringoma

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (Figure 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (Figure 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulgar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (Figures 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (Figure 3). Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems.

- Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP. Dermatology. 2nd ed. Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2008.

- Weedon D. Skin Pathology. 3rd ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010.

- Carneiro SJ, Gardner HL, Knox JM. Syringoma of the vulva. Arch Dermatol. 1971;103:494-496.

- Trager JD, Silvers J, Reed JA, et al. Neck and vulvar papules in an 8-year-old girl. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:203, 206.

- Pérez-Bustillo A, Ruiz-González I, Delgado S, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a rare cause of vulvar pruritus. Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. 2008;99:580-581.

- Huang YH, Chuang YH, Kuo TT, et al. Vulvar syringoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistologic study of 18 patients and results of treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:735-739.

- Dereli T, Turk BG, Kazandi AC. Syringomas of the vulva. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;99:65-66.

- Blasdale C, McLelland J. Solitary giant vulval syringoma. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:374-375.

- Kavala M, Can B, Zindanci I, et al. Vulvar pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:831-832.

- Gerdsen R, Wenzel J, Uerlich M, et al. Periodic genital pruritus caused by syringoma of the vulva. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:369-370.

- Bal N, Aslan E, Kayaselcuk F, et al. Vulvar syringoma aggravated by pregnancy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;9:196-197.

- Turan C, Ugur M, Kutluay L, et al. Vulvar syringoma exacerbated during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1996;64:141-142.

- Wallace ML, Smoller BR. Progesterone receptor positivity supports hormonal control of syringomas. J Cutan Pathol. 1995;22:442-445.

- Yorganci A, Kale A, Dunder I, et al. Vulvar syringoma showing progesterone receptor positivity. BJOG. 2000;107:292-294.

- Draznin M. Hereditary syringomas: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:19.

- Goldstein DJ, Barr RJ, Santa Cruz DJ. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. Cancer. 1982;50:566-572.

- Hamsch C, Hartschuh W. Microcystic adnexal carcinoma - aggressive infiltrative tumor often with innocent clinical appearance. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2010;8:275-278.

- Henner MS, Shapiro PE, Ritter JH, et al. Solitary syringoma. report of five cases and clinicopathologic comparison with microcystic adnexal carcinoma of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:465-470.

- Suwattee P, McClelland MC, Huiras EE, et al. Plaque-type syringoma: two cases misdiagnosed as microcystic adnexal carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:570-574.

- Iwao F, Onozuka T, Kawashima T. Vulval syringoma successfully treated with tranilast. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1228-1230.

- Garman M, Metry D. Vulvar syringomas in a 9-year-old child with review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:369-372.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (Figure 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (Figure 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually are asymptomatic and noticed during routine gynecologic examination. Therefore, it is believed that they likely are underdiagnosed.5 When symptomatic, they commonly present with constant9 or intermittent5 pruritus, which may intensify during menstruation, pregnancy, and summertime.6,10-12 Gerdsen et al10 documented a 27-year-old woman who presented with a 2-year history of pruritic vulvar skin lesions that became exacerbated during menstruation, which raised the possibility of cyclical hormonal changes being responsible for periodic exacerbation of vulvar pruritus during menstruation. In addition, patients may experience an increase in size and number of the lesions during pregnancy. Bal et al11 reported a 24-year-old primigravida with vulvar papular lesions that intensified during pregnancy. She had experienced intermittent vulvar pruritus for 12 years but had no change in symptoms during menstruation.11 Few studies have attempted to evaluate the presence of ER and PR in the syringomas. A study of 9 nonvulvar syringomas by Wallace and Smoller13 showed ER positivity in 1 case and PR positivity in 8 cases, lending support to the hormonal theory; however, in another case series of 15 vulvar syringomas, Huang et al6 failed to show ER and PR expression by immunohistochemical staining. A case report published 3 years earlier documented the first case of PR positivity on a vulvar syringoma.14 Our patient also was negative for ER and PR, which suggested that hormonal status is important in some but not all syringomas.

Patients with vulgar syringomas also might have coexisting extragenital syringomas in the neck,4 eyelids,6,7,10 and periorbital area,6 and thorough examination of the body is essential. If an extragenital syringoma is diagnosed, a vulvar syringoma should be considered, especially when the patient presents with unexplained genital symptoms. Although no proven hereditary transmission pattern has been established, family history of syringomas has been established in several cases.15 In a case series reported by Huang et al,6 4 of 18 patients reported a family history of periorbital syringomas. In our case, the patient did not report a family history of syringomas.

The differential diagnosis of vulvar lesions with pruritus is broad and includes Fox-Fordyce disease, lichen planus, LSC, epidermal cysts, senile angiomas, dystrophic calcinosis, xanthomas, steatocytomas, soft fibromas, condyloma acuminatum, and candidiasis. Vulvar syringomas might have a nonspecific appearance, and histologic examination is essential to confirm the diagnosis and rule out any malignant process such as MAC, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia, extramammary Paget disease, or other glandular neoplasms of the vulva.

Microcystic adnexal carcinoma was first reported in 1982 by Goldstein et al16 as a locally aggressive neoplasm that can be confused with benign adnexal neoplasms, particularly desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, trichoadenoma, and syringoma. Microcystic adnexal carcinomas present as slow-growing, flesh-colored papules that may resemble syringomas and appear in similar body sites. Histologic examination is essential to differentiate between these two entities. Syringomas are tumors confined to the dermis and are composed of multiple small ducts lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a dense fibrous stroma. Unlike syringomas, MACs usually infiltrate diffusely into the dermis and subcutis and may extend into the underlying muscle. Although bland cytologic features predominate, perineural invasion frequently is present in MACs. A potential pitfall of misdiagnosis can be caused by a superficial biopsy that may reveal benign histologic appearance, particularly in the upper level of the tumor where it may be confused with a syringoma or a benign follicular neoplasm.17

The initial biopsy performed on our patient was possibly not deep enough to render an unequivocal diagnosis and therefore bilateral partial radical vulvectomy was considered. After surgery, histologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a poorly circumscribed tumor confined to the dermis. The tumor was broad and the lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis and perineural invasion favored a syringoma (Figures 2A and 2B). These findings were consistent with case reports that documented syringomas as being more wide than deep on microscopic examination, whereas the opposite pertained to MAC.18 Cases of plaque-type syringomas that initially were misdiagnosed as MACs also have been reported.19 Because misdiagnosis may affect the treatment plan and potentially result in unnecessary surgery, caution should be taken when differentiating between these two entities. When a definitive diagnosis cannot be rendered on a superficial biopsy, a recommendation should be made for a deeper biopsy sampling the subcutis.

For the majority of the patients with vulvar syringomas, treatment is seldom required due to their asymptomatic nature; however, patients who present with symptoms usually report pruritus of variable intensities and patterns. A standardized treatment does not exist for vulvar syringomas, and oral or topical treatment might be used as an initial approach. Commonly prescribed medications with variable results include topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and topical retinoids. In a case reported by Iwao et al,20 vulvar syringomas were successfully treated with tranilast, which has anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects. This medication could have a possible dual action—inhibiting the release of chemical mediators from the mast cells and inhibiting the release of IL-1β from the eccrine duct, which could suppress the proliferation of stromal connective tissue. Our case was stained with toluidine blue and showed an increased number of mast cells in the tissue (Figure 3). Patients who are unresponsive to tranilast or have extensive disease resulting in cosmetic disfigurement might benefit from more invasive treatment methods including a variety of lasers, cryotherapy, electrosurgery, and excision. Excisions should include the entire tumor to avoid recurrence. In a case reported by Garman and Metry,21 the lesions were surgically excised using small 2- to 3-mm punches; however, several weeks later the lesions recurred. Our patient presented with a 1-month evolution of dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities that were probably not treated with oral or topical medications before being referred for surgery.

We report a case of a vulvar syringoma that presented diagnostic challenges in the initial biopsy, which prevented the exclusion of an MAC. After partial radical vulvectomy, histologic examination was more definitive, showing lack of deep infiltration into the subcutis or perineural invasion that are commonly seen in MAC. This case is an example of a notable pitfall in the diagnosis of vulvar syringoma on a limited biopsy leading to overtreatment. Raising awareness of this entity is the only modality to prevent misdiagnosis. We encourage reporting of further cases of syringomas, particularly those with atypical locations or patterns that may cause diagnostic problems.

To the Editor:

Syringomas are common benign tumors of the eccrine sweat glands that usually manifest clinically as multiple flesh-colored papules. They are most commonly seen on the face, neck, and chest of adolescent girls. Syringomas may appear at any site of the body but are rare in the vulva. We present a case of a 51-year-old woman who was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of a tumor carrying a differential diagnosis of vulvar syringoma vs microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC).

A 51-year-old woman presented to dermatology (G.G.) and was referred to the Division of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for further management of possible vulvar syringoma vs MAC. The patient previously had been evaluated at an outside community practice due to dyspareunia, vulvar discomfort, and vulvar irregularities of 1 month’s duration. At that time, a small biopsy was performed, and the histologic differential diagnosis included syringoma vs an adnexal carcinoma. Consequently, she was referred to gynecologic oncology for further management.

Pelvic examination revealed multilobular nodular areas overlying the clitoral hood that extended down to the labia majora. The nodular processes did not involve the clitoris, labia minora, or perineum. A mobile isolated lymph node measuring 2.0×1.0 cm in the right inguinal area also was noted. The patient’s clinical history was notable for right breast carcinoma treated with a right mastectomy with axillary lymph node dissection that showed metastatic disease. She also underwent adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel and doxorubicin for breast carcinoma.

After discussing the diagnostic differential and treatment options, the patient elected to undergo a bilateral partial radical vulvectomy with reconstruction and resection of the right inguinal lymph node. Gross examination of the vulvectomy specimen showed multiple flesh-colored papules (Figure 1). Histologic examination revealed a neoplasm with sweat gland differentiation that was broad and poorly circumscribed but confined to the dermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The neoplasm was composed of epithelial cells that formed ductlike structures, lined by 2 layers of cuboidal epithelium within a fibrous stroma (Figure 2C). A toluidine blue special stain was performed and demonstrated an increased amount of mast cells in the tissue (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical stains for gross cystic disease fluid protein, estrogen receptor (ER), and progesterone receptor (PR) were negative in the tumor cells. The lack of cytologic atypia, perineural invasion, and deep infiltration into the subcutis favored a syringoma. One month later, the case was presented at the Tumor Board Conference at the University of Alabama at Birmingham where a final diagnosis of vulvar syringoma was agreed upon and discussed with the patient. At that time, no recurrence was evident and follow-up was recommended.

Syringomas are benign tumors of the sweat glands that are fairly common and appear to have a predilection for women. Although most of the literature classifies them as eccrine neoplasms, the term syringoma can be used to describe neoplasms of either apocrine or eccrine lineage.1 To rule out an apocrine lineage of the tumor in our patient, we performed immunohistochemistry for gross cystic disease fluid protein, a marker of apocrine differentiation. This stain highlighted normal apocrine glands that were not involved in the tumor proliferation.

Syringomas may occur at any site on the body but are prone to occur on the periorbital area, especially the eyelids.1 Some of the atypical locations for a syringoma include the anterior neck, chest, abdomen, genitals, axillae, groin, and buttocks.2 Vulvar syringomas were first reported by Carneiro3 in 1971 as usually affecting adolescent girls and middle-aged women. There have been approximately 40 reported cases affecting women aged 8 to 78 years.4,5 Vulvar syringomas classically appear as firm or soft, flesh-colored to transparent, papular lesions. The 2 other clinical variants are miliumlike, whitish, cystic papules as well as lichenoid papules.6 Pérez-Bustillo et al5 reported a case of the lichenoid papule variant on the labia majora of a 78-year-old woman who presented with intermittent vulvar pruritus of 4 years’ duration. Due to this patient’s 9-year history of urinary incontinence, the lesions had been misdiagnosed as irritant dermatitis and associated lichen simplex chronicus (LSC). This case is a reminder to consider vulvar syringoma in patients with LSC who respond poorly to oral antihistamines and topical steroids.5 Rarely, multiple clinical variants may coexist. In a case reported by Dereli et al,7 a 19-year-old woman presented with concurrent classical and miliumlike forms of vulvar syringoma.

Vulvar syringomas usually present as multiple lesions involving both sides of the labia majora; however, Blasdale and McLelland8 reported a single isolated syringoma of the vulva on the anterior right labia minora that measured 1.0×0.5 cm, leading the lesion to be described as a giant syringoma.