User login

Liver Abscess and Metastatic Endophthalmitis

Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess is known to be associated with metastatic endophthalmitis,1 although most cases have been clustered in Taiwan, with few reports in the United States.2 The first reported case of Klebsiella liver abscess with endophthalmitis in the United States was in a 38‐year‐old man with a new diagnosis of diabetes, a known risk factor for hematogenous spread of Klebsiella to metastatic sites.3

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 43‐year old Haitian man presented after experiencing 5 days of right eye pain with associated fever and swelling. The patient denied preceding trauma, manipulation of the eye, contact lens use, or illicit drug use and had no significant medical history. He had moved to the United States from Haiti more than 15 years ago and had not traveled out of the state of Florida since that time.

Physical exam showed tachycardia (rate = 110/min), tachypnea (rate = 20/min), and a temperature of 101.5F. The right eye had injected conjunctiva, a swollen lid, and decreased palpebral fissure, and visual acuity on the left was 20/60, whereas visual acuity on the right was recorded as the ability to count fingers at 3 feet. The remainder of his physical exam was within normal limits including the abdominal exam.

Laboratory data on admission included a white blood cell count of 37,500/L significant for 12% bands, total bilirubin of 2.8 mg/dL, AST of 141 U/L, ALT of 130 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase of 196 U/L. HIV testing was negative, and urine toxicology did not detect the presence of any illicit drugs. Vitreous cultures grew Klebsiella pneumoniae.

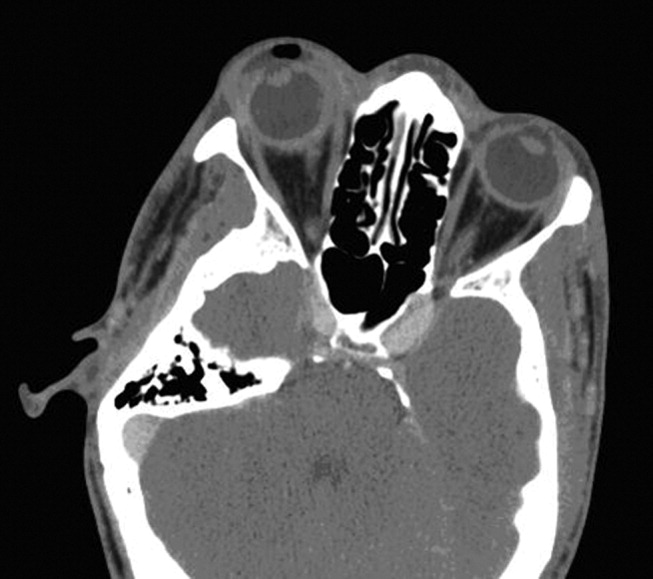

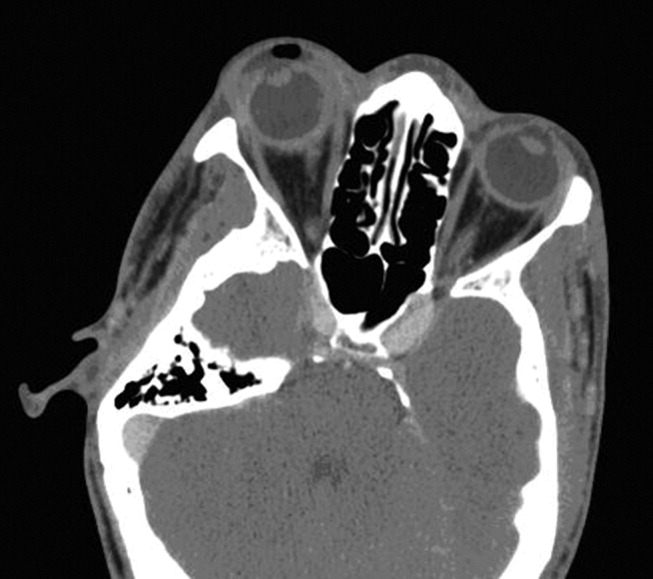

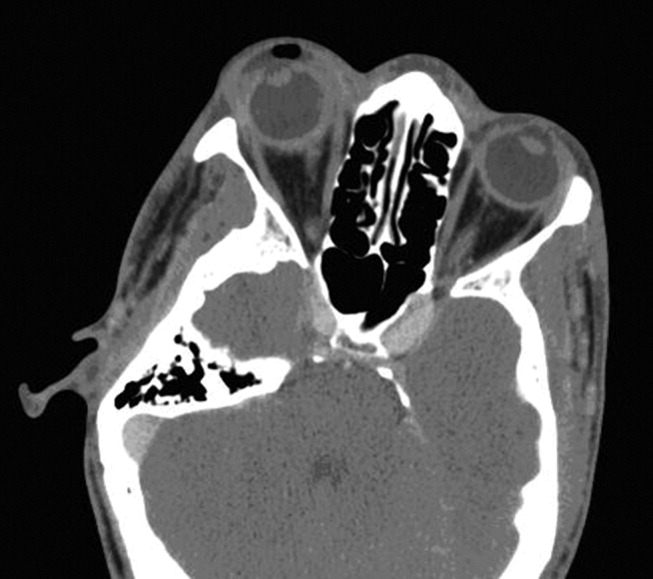

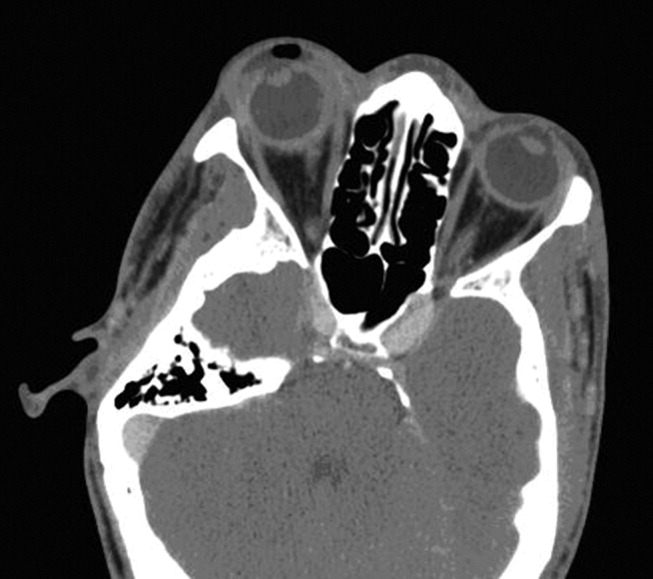

The initial CT scan of the orbit (Fig. 1) showed periorbital swelling and a preseptal collection anterior to the right globe consistent with an abscess. Because of the abnormal results of the liver panel in the presence of the ophthalmologic infection, an abdominal CT was obtained that showed an 11.5 by 8.0 cm lesion involving all segments of the right lobe of the liver with a 0.9‐mm cylindrical extension toward the right hepatic vein.

Percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess was performed, yielding positive cultures for K. pneumoniae. The patient was treated with oral gatifloxacin and intravenous ceftriaxone. Gatifloxacin therapy was chosen for its excellent penetrance into the vitreous.4 Despite antibiotic therapy, a repeat CT scan of the orbit showed further extension of the collection, and the decision was made to drain the abscess and perform right eye enucleation. The patient was discharged home on oral gatifloxacin. A follow‐up abdominal ultrasound 2 weeks after discharge showed complete resolution of the liver abscess.

DISCUSSION

Bacterial endophthalmitis is a rare infection involving the vitreous humor and other deep intraocular structures. It is most commonly exogenous in origin, caused by intraocular surgery, penetrating injury, a corneal ulcer, or periocular infection. Endogenous endophthalmitis occurs when organisms reach the eye hematogenously and accounts for fewer than 6% of all cases of endophthalmitis.5

Klebsiella liver abscesses have been increasing in incidence worldwide and since the mid‐1990s have become a common cause of liver abscess in the United States, along with Escherichia coli. The association with endophthalmitis was first reported in a series of 7 cases from Taiwan in 1986,1 and subsequent East Asian cases have been reported, usually in diabetic patients.6, 7 The association of Klebsiella liver abscesses with endogenous endophthalmitis has been rarely reported in the United States, with review of the literature from 1966 to 2003 revealing only 3 reported cases.2 One of these patients had diabetes, whereas another had beta‐thalassemia with previous splenectomy. Another study looking at only pyogenic liver abscess found biliary disease, hypertension, intraabdominal infection, and diabetes to be the most common underlying or concurrent conditions.8 Our patient did not appear to have any of these risk factors.

Our patient had no known risk factors to promote metastatic spread of the causative organisms. The patient was HIV negative, had no personal or family history of diabetes, and was not found to have elevated glucose levels at any point during admission. Although the ultimate etiology may never be determined, the possibility of undetected malignancy or cardiovascular or inflammatory disease cannot be excluded.

Physicians need to be aware of the global emergence of a hypervirulent strain of K. pneumonia causing liver abscesses and metastatic complications, especially endophthalmitis.9 Mucoviscosity associated gene A (magA) has been found in some liver isolates of K. pneumoniae.10 It has been suggested that as many as one‐third of patients infected with hyperviscous strains of K. pneumoniae will develop an invasive infection.11 Although it is unclear why metastatic endophthalmitis from Klebsiella liver abscess would be more common in East Asia, the magA gene may account for the observed difference. It was not possible to determine if the infectious organism that had infected our patient had the magA gene, although the clinical use of this information may not have changed management because the patient presented with metastatic infection. If this patient's particular organism had tested positive for the magA gene, it might explain why an apparently immunocompetent patient developed metastatic endophthalmitis not simply a liver abscess.

Patients with evidence of endogenous endophthalmitis without clear risk factors should be covered for K. pneumoniae, and extraocular sources should be sought, particularly the liver, even in the absence of diabetes. Early recognition and prompt initiation of antimicrobial therapy is essential if the patient's vision is to be preserved.

- ,,.Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess associated with septic endophthalmitis.Arch Intern Med.1986;146:1913–1916.

- ,.Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics.Am J Gastroenterol.2005;100:322–331.

- .Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess, endophthalmitis, and meningitis in a man with newly recognized diabetes mellitus.Clin Infect Dis.1999;29:1570–1571.

- ,,.Vitreous and aqueous penetration of orally administered gatifloxacin in humans.Arch Ophthalmol.2003;121:345–350.

- ,,,.Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17‐year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases.Surv Ophthalmol.2003;48:403–423.

- ,,, et al.Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan.Clin Infect Dis.1998;26:1434–1438.

- ,,,,.Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess. Their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients.Arch Intern Med.1991;151:1557–1559.

- ,,,.Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality.Clin Infect Dis.2004;39:1654–1659.

- ,,, et al.A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis?Gut.2002;50:420–424.

- ,,.Liver abscess caused by magA+ Klebsiella pneumoniae in North America.J Clin Microbiol.2005;43:991–992.

- ,,, et al.Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: association with invasive syndrome in patients with community‐acquired bacteraemia.J Intern Med.2006;259:606–614.

Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess is known to be associated with metastatic endophthalmitis,1 although most cases have been clustered in Taiwan, with few reports in the United States.2 The first reported case of Klebsiella liver abscess with endophthalmitis in the United States was in a 38‐year‐old man with a new diagnosis of diabetes, a known risk factor for hematogenous spread of Klebsiella to metastatic sites.3

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 43‐year old Haitian man presented after experiencing 5 days of right eye pain with associated fever and swelling. The patient denied preceding trauma, manipulation of the eye, contact lens use, or illicit drug use and had no significant medical history. He had moved to the United States from Haiti more than 15 years ago and had not traveled out of the state of Florida since that time.

Physical exam showed tachycardia (rate = 110/min), tachypnea (rate = 20/min), and a temperature of 101.5F. The right eye had injected conjunctiva, a swollen lid, and decreased palpebral fissure, and visual acuity on the left was 20/60, whereas visual acuity on the right was recorded as the ability to count fingers at 3 feet. The remainder of his physical exam was within normal limits including the abdominal exam.

Laboratory data on admission included a white blood cell count of 37,500/L significant for 12% bands, total bilirubin of 2.8 mg/dL, AST of 141 U/L, ALT of 130 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase of 196 U/L. HIV testing was negative, and urine toxicology did not detect the presence of any illicit drugs. Vitreous cultures grew Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The initial CT scan of the orbit (Fig. 1) showed periorbital swelling and a preseptal collection anterior to the right globe consistent with an abscess. Because of the abnormal results of the liver panel in the presence of the ophthalmologic infection, an abdominal CT was obtained that showed an 11.5 by 8.0 cm lesion involving all segments of the right lobe of the liver with a 0.9‐mm cylindrical extension toward the right hepatic vein.

Percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess was performed, yielding positive cultures for K. pneumoniae. The patient was treated with oral gatifloxacin and intravenous ceftriaxone. Gatifloxacin therapy was chosen for its excellent penetrance into the vitreous.4 Despite antibiotic therapy, a repeat CT scan of the orbit showed further extension of the collection, and the decision was made to drain the abscess and perform right eye enucleation. The patient was discharged home on oral gatifloxacin. A follow‐up abdominal ultrasound 2 weeks after discharge showed complete resolution of the liver abscess.

DISCUSSION

Bacterial endophthalmitis is a rare infection involving the vitreous humor and other deep intraocular structures. It is most commonly exogenous in origin, caused by intraocular surgery, penetrating injury, a corneal ulcer, or periocular infection. Endogenous endophthalmitis occurs when organisms reach the eye hematogenously and accounts for fewer than 6% of all cases of endophthalmitis.5

Klebsiella liver abscesses have been increasing in incidence worldwide and since the mid‐1990s have become a common cause of liver abscess in the United States, along with Escherichia coli. The association with endophthalmitis was first reported in a series of 7 cases from Taiwan in 1986,1 and subsequent East Asian cases have been reported, usually in diabetic patients.6, 7 The association of Klebsiella liver abscesses with endogenous endophthalmitis has been rarely reported in the United States, with review of the literature from 1966 to 2003 revealing only 3 reported cases.2 One of these patients had diabetes, whereas another had beta‐thalassemia with previous splenectomy. Another study looking at only pyogenic liver abscess found biliary disease, hypertension, intraabdominal infection, and diabetes to be the most common underlying or concurrent conditions.8 Our patient did not appear to have any of these risk factors.

Our patient had no known risk factors to promote metastatic spread of the causative organisms. The patient was HIV negative, had no personal or family history of diabetes, and was not found to have elevated glucose levels at any point during admission. Although the ultimate etiology may never be determined, the possibility of undetected malignancy or cardiovascular or inflammatory disease cannot be excluded.

Physicians need to be aware of the global emergence of a hypervirulent strain of K. pneumonia causing liver abscesses and metastatic complications, especially endophthalmitis.9 Mucoviscosity associated gene A (magA) has been found in some liver isolates of K. pneumoniae.10 It has been suggested that as many as one‐third of patients infected with hyperviscous strains of K. pneumoniae will develop an invasive infection.11 Although it is unclear why metastatic endophthalmitis from Klebsiella liver abscess would be more common in East Asia, the magA gene may account for the observed difference. It was not possible to determine if the infectious organism that had infected our patient had the magA gene, although the clinical use of this information may not have changed management because the patient presented with metastatic infection. If this patient's particular organism had tested positive for the magA gene, it might explain why an apparently immunocompetent patient developed metastatic endophthalmitis not simply a liver abscess.

Patients with evidence of endogenous endophthalmitis without clear risk factors should be covered for K. pneumoniae, and extraocular sources should be sought, particularly the liver, even in the absence of diabetes. Early recognition and prompt initiation of antimicrobial therapy is essential if the patient's vision is to be preserved.

Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess is known to be associated with metastatic endophthalmitis,1 although most cases have been clustered in Taiwan, with few reports in the United States.2 The first reported case of Klebsiella liver abscess with endophthalmitis in the United States was in a 38‐year‐old man with a new diagnosis of diabetes, a known risk factor for hematogenous spread of Klebsiella to metastatic sites.3

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 43‐year old Haitian man presented after experiencing 5 days of right eye pain with associated fever and swelling. The patient denied preceding trauma, manipulation of the eye, contact lens use, or illicit drug use and had no significant medical history. He had moved to the United States from Haiti more than 15 years ago and had not traveled out of the state of Florida since that time.

Physical exam showed tachycardia (rate = 110/min), tachypnea (rate = 20/min), and a temperature of 101.5F. The right eye had injected conjunctiva, a swollen lid, and decreased palpebral fissure, and visual acuity on the left was 20/60, whereas visual acuity on the right was recorded as the ability to count fingers at 3 feet. The remainder of his physical exam was within normal limits including the abdominal exam.

Laboratory data on admission included a white blood cell count of 37,500/L significant for 12% bands, total bilirubin of 2.8 mg/dL, AST of 141 U/L, ALT of 130 U/L, and alkaline phosphatase of 196 U/L. HIV testing was negative, and urine toxicology did not detect the presence of any illicit drugs. Vitreous cultures grew Klebsiella pneumoniae.

The initial CT scan of the orbit (Fig. 1) showed periorbital swelling and a preseptal collection anterior to the right globe consistent with an abscess. Because of the abnormal results of the liver panel in the presence of the ophthalmologic infection, an abdominal CT was obtained that showed an 11.5 by 8.0 cm lesion involving all segments of the right lobe of the liver with a 0.9‐mm cylindrical extension toward the right hepatic vein.

Percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess was performed, yielding positive cultures for K. pneumoniae. The patient was treated with oral gatifloxacin and intravenous ceftriaxone. Gatifloxacin therapy was chosen for its excellent penetrance into the vitreous.4 Despite antibiotic therapy, a repeat CT scan of the orbit showed further extension of the collection, and the decision was made to drain the abscess and perform right eye enucleation. The patient was discharged home on oral gatifloxacin. A follow‐up abdominal ultrasound 2 weeks after discharge showed complete resolution of the liver abscess.

DISCUSSION

Bacterial endophthalmitis is a rare infection involving the vitreous humor and other deep intraocular structures. It is most commonly exogenous in origin, caused by intraocular surgery, penetrating injury, a corneal ulcer, or periocular infection. Endogenous endophthalmitis occurs when organisms reach the eye hematogenously and accounts for fewer than 6% of all cases of endophthalmitis.5

Klebsiella liver abscesses have been increasing in incidence worldwide and since the mid‐1990s have become a common cause of liver abscess in the United States, along with Escherichia coli. The association with endophthalmitis was first reported in a series of 7 cases from Taiwan in 1986,1 and subsequent East Asian cases have been reported, usually in diabetic patients.6, 7 The association of Klebsiella liver abscesses with endogenous endophthalmitis has been rarely reported in the United States, with review of the literature from 1966 to 2003 revealing only 3 reported cases.2 One of these patients had diabetes, whereas another had beta‐thalassemia with previous splenectomy. Another study looking at only pyogenic liver abscess found biliary disease, hypertension, intraabdominal infection, and diabetes to be the most common underlying or concurrent conditions.8 Our patient did not appear to have any of these risk factors.

Our patient had no known risk factors to promote metastatic spread of the causative organisms. The patient was HIV negative, had no personal or family history of diabetes, and was not found to have elevated glucose levels at any point during admission. Although the ultimate etiology may never be determined, the possibility of undetected malignancy or cardiovascular or inflammatory disease cannot be excluded.

Physicians need to be aware of the global emergence of a hypervirulent strain of K. pneumonia causing liver abscesses and metastatic complications, especially endophthalmitis.9 Mucoviscosity associated gene A (magA) has been found in some liver isolates of K. pneumoniae.10 It has been suggested that as many as one‐third of patients infected with hyperviscous strains of K. pneumoniae will develop an invasive infection.11 Although it is unclear why metastatic endophthalmitis from Klebsiella liver abscess would be more common in East Asia, the magA gene may account for the observed difference. It was not possible to determine if the infectious organism that had infected our patient had the magA gene, although the clinical use of this information may not have changed management because the patient presented with metastatic infection. If this patient's particular organism had tested positive for the magA gene, it might explain why an apparently immunocompetent patient developed metastatic endophthalmitis not simply a liver abscess.

Patients with evidence of endogenous endophthalmitis without clear risk factors should be covered for K. pneumoniae, and extraocular sources should be sought, particularly the liver, even in the absence of diabetes. Early recognition and prompt initiation of antimicrobial therapy is essential if the patient's vision is to be preserved.

- ,,.Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess associated with septic endophthalmitis.Arch Intern Med.1986;146:1913–1916.

- ,.Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics.Am J Gastroenterol.2005;100:322–331.

- .Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess, endophthalmitis, and meningitis in a man with newly recognized diabetes mellitus.Clin Infect Dis.1999;29:1570–1571.

- ,,.Vitreous and aqueous penetration of orally administered gatifloxacin in humans.Arch Ophthalmol.2003;121:345–350.

- ,,,.Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17‐year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases.Surv Ophthalmol.2003;48:403–423.

- ,,, et al.Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan.Clin Infect Dis.1998;26:1434–1438.

- ,,,,.Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess. Their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients.Arch Intern Med.1991;151:1557–1559.

- ,,,.Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality.Clin Infect Dis.2004;39:1654–1659.

- ,,, et al.A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis?Gut.2002;50:420–424.

- ,,.Liver abscess caused by magA+ Klebsiella pneumoniae in North America.J Clin Microbiol.2005;43:991–992.

- ,,, et al.Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: association with invasive syndrome in patients with community‐acquired bacteraemia.J Intern Med.2006;259:606–614.

- ,,.Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess associated with septic endophthalmitis.Arch Intern Med.1986;146:1913–1916.

- ,.Pyogenic liver abscess with a focus on Klebsiella pneumoniae as a primary pathogen: an emerging disease with unique clinical characteristics.Am J Gastroenterol.2005;100:322–331.

- .Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess, endophthalmitis, and meningitis in a man with newly recognized diabetes mellitus.Clin Infect Dis.1999;29:1570–1571.

- ,,.Vitreous and aqueous penetration of orally administered gatifloxacin in humans.Arch Ophthalmol.2003;121:345–350.

- ,,,.Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis: a 17‐year prospective series and review of 267 reported cases.Surv Ophthalmol.2003;48:403–423.

- ,,, et al.Primary liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan.Clin Infect Dis.1998;26:1434–1438.

- ,,,,.Septic metastatic lesions of pyogenic liver abscess. Their association with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in diabetic patients.Arch Intern Med.1991;151:1557–1559.

- ,,,.Pyogenic liver abscess: recent trends in etiology and mortality.Clin Infect Dis.2004;39:1654–1659.

- ,,, et al.A global emerging disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: is serotype K1 an important factor for complicated endophthalmitis?Gut.2002;50:420–424.

- ,,.Liver abscess caused by magA+ Klebsiella pneumoniae in North America.J Clin Microbiol.2005;43:991–992.

- ,,, et al.Clinical implications of hypermucoviscosity phenotype in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates: association with invasive syndrome in patients with community‐acquired bacteraemia.J Intern Med.2006;259:606–614.

Life as a Nocturnist

Jackson Memorial Hospital is an accredited, nonprofit, tertiary care hospital and the major teaching facility for the University of Miami School of Medicine. Jackson Memorial Hospital is one of the busiest centers in the country, with approximately 1500 licensed beds, 225,000 emergency and urgent care visits, and nearly 60,000 admissions to the hospital each year. Furthermore, JMH is the only full-service provider for the uninsured and medically indigent in Miami-Dade County, Florida.

Jackson Memorial Hospital has a broad range of tertiary services and clinical programs designed to serve the entire community. Its medical staff is recognized nationally for the quality of its patient care, teaching, and research. The hospital has over 11,000 full-time employees, approximately 1000 house staff, and nearly 700 clinical attending physicians from the University of Miami School of Medicine alone.

Our medicine department is composed of the following inpatient services: eight general medical teaching teams, three HIV/AIDS teams, one cardiology team, an acute care for the elderly (ACE) unit, one oncology team, and a hospitalist run (non-teaching) service.

Over the last several years a combination of the pressures from outside regulatory agencies and an increasing number of patient admissions brought the admitting process to a breaking point. Teaching services were being held to the admission cap guidelines by the Residency Review Committee (RRC). Furthermore, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) began to enforce strict work-hour rules for all training programs. With these restrictions a fixed number of admissions were admitted to a fixed number of services within a shorter period of the day. In fact, many patients were being held in the emergency department (ED) for as long as 15 hours before an internal medicine service saw the patient or wrote admission orders. We had concerns about safety and the provision of high quality of care for these patients. One of the concerns was that ED physicians were caring for patients who were essentially inpatients while continuing to treat new ED cases.

In an attempt to provide excellent care to our patients, we developed the Emergency Medical Hospitalist Service (EMHS), a nocturnist service. The goals of this service are to: (1) provide attendinglevel care to patients requiring admission, (2) allow the hospital to operate within the admission cap guideline set forth by the RRC, (3) function during the time in which the ACGME work hour limits were affecting the hospital, and (4) operate in a manner that would be at least cost neutral for the institution. We hired two internists (myself and Dr. Roshan K. Rao) to admit patients overnight and begin their inpatient work-up. During this shift, we admit and initiate the inpatient care of all medical admissions for the inpatient services, including the housestaff covered teams. During a typical 12-hour shift, we will admit an average of 10–12 new patients from the ED. In addition to this, there is one resident on each night (termed “night relief”), who provides cross-coverage of existing medical inpatients. We also work in close concert with the newly developed “Patient Placement Coordinator,” who facilitates prompt bed assignments and movement of these patients to in-house beds.

Currently there are two of us, so we make our own schedule depending on each others’ needs. We currently work one week on/one week off, from 8 p.m. To 8 a.m. Towards the end of the shift, we sign out the newly admitted patients to the appropriate services. Typically, the resident will come into the ED and take their sign-out from one of us. The geriatrics fellows and non-teaching hospitalists usually take sign-out over the phone. The entire sign-out process occurs anytime from 6:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. We also reserve this part of the shift to follow up laboratory studies and other diagnostic procedures. Occasionally, we are able to discharge some patients by the end of the shift as well.

On occasion, we will call in the other nocturnist to help out when admissions are too numerous for one physician to handle. This typically occurs towards the end of the work week. We usually require “double coverage” approximately 6–8 nights per month.

Since we instituted the nocturnist program 2 years ago, we have seen great improvements in ED throughput, inpatient bed utilization, patient satisfaction, average length of stay (both in the ED and inpatient), and quality of care. As soon as the emergency physician makes their decision to admit the patient, one of us is already interviewing, examining, and writing admission orders on the patient. This speeds up the process of the patient’s evaluation and allows the patient to be immediately transferred to a quiet room. Furthermore, this allows us to develop a rapport with the patient in the middle of the night, instead of feeling rushed in the morning to round on as many as 20 new patients. This also ensures a good night’s rest for the patient and improves the bed utilization. Moving patients to the floor in a timely fashion also allows for the ED to treat more patients.

Having a nocturnist in the hospital throughout the night allows for a more precise and accurate physical exam, formulation of an impression, and execution of a treatment plan. Physicians who are on-call at home often do not get the complete or correct story from the ED, which can lead to incomplete admission orders and delayed treatment plans. This can lead to unnecessary increases in length of stay. For example, I often admit “chest pain” patients, who by morning have already “ruled out” for an acute coronary event, had a stress test, and are ready for discharge before the “daytime” physician has seen the patient. Another example is diabetic ketoacidosis. I am able to be very aggressive with the treatment plan throughout the night, again decreasing length of stay and hospital costs.

Nocturnism is not only advantageous to the hospital and patients, but also to the nocturnist himself/herself. Dedicated nocturnists have less fatigue and stress. I work only nights, so I do not become excessively tired. My sleep schedule is completely reversed from the norm. This also has many advantages to my personal life. One of these is that I never miss a package delivered to my home!

Indeed, developing this program was a challenge. Initially we sold the idea through a combination of patient safety and revenue. The hospital cannot bill for holding patients in the ED. If we admit patients and move them to an inpatient bed, the hospital can generate this otherwise lost revenue. As with any new idea, we did meet resistance and opposition along the way. However, we were able to overcome these obstacles and build upon them. Once the administration saw the improvements and our productivity, they were immensely pleased. In fact, the administration is already looking at expanding our staffing and our services. Our billing and collections have shown we pay for our cost and generate additional funds for the hospital, despite a poor payer mix. I am excited to see what the future holds for nocturnists, not only in our institution, but across the country. Groups that employ nocturnists probably wonder how they ever survived without them in the past.

Dr. Sabharwal can be contacted at ASabharwal@med.miami.edu.

Jackson Memorial Hospital is an accredited, nonprofit, tertiary care hospital and the major teaching facility for the University of Miami School of Medicine. Jackson Memorial Hospital is one of the busiest centers in the country, with approximately 1500 licensed beds, 225,000 emergency and urgent care visits, and nearly 60,000 admissions to the hospital each year. Furthermore, JMH is the only full-service provider for the uninsured and medically indigent in Miami-Dade County, Florida.

Jackson Memorial Hospital has a broad range of tertiary services and clinical programs designed to serve the entire community. Its medical staff is recognized nationally for the quality of its patient care, teaching, and research. The hospital has over 11,000 full-time employees, approximately 1000 house staff, and nearly 700 clinical attending physicians from the University of Miami School of Medicine alone.

Our medicine department is composed of the following inpatient services: eight general medical teaching teams, three HIV/AIDS teams, one cardiology team, an acute care for the elderly (ACE) unit, one oncology team, and a hospitalist run (non-teaching) service.

Over the last several years a combination of the pressures from outside regulatory agencies and an increasing number of patient admissions brought the admitting process to a breaking point. Teaching services were being held to the admission cap guidelines by the Residency Review Committee (RRC). Furthermore, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) began to enforce strict work-hour rules for all training programs. With these restrictions a fixed number of admissions were admitted to a fixed number of services within a shorter period of the day. In fact, many patients were being held in the emergency department (ED) for as long as 15 hours before an internal medicine service saw the patient or wrote admission orders. We had concerns about safety and the provision of high quality of care for these patients. One of the concerns was that ED physicians were caring for patients who were essentially inpatients while continuing to treat new ED cases.

In an attempt to provide excellent care to our patients, we developed the Emergency Medical Hospitalist Service (EMHS), a nocturnist service. The goals of this service are to: (1) provide attendinglevel care to patients requiring admission, (2) allow the hospital to operate within the admission cap guideline set forth by the RRC, (3) function during the time in which the ACGME work hour limits were affecting the hospital, and (4) operate in a manner that would be at least cost neutral for the institution. We hired two internists (myself and Dr. Roshan K. Rao) to admit patients overnight and begin their inpatient work-up. During this shift, we admit and initiate the inpatient care of all medical admissions for the inpatient services, including the housestaff covered teams. During a typical 12-hour shift, we will admit an average of 10–12 new patients from the ED. In addition to this, there is one resident on each night (termed “night relief”), who provides cross-coverage of existing medical inpatients. We also work in close concert with the newly developed “Patient Placement Coordinator,” who facilitates prompt bed assignments and movement of these patients to in-house beds.

Currently there are two of us, so we make our own schedule depending on each others’ needs. We currently work one week on/one week off, from 8 p.m. To 8 a.m. Towards the end of the shift, we sign out the newly admitted patients to the appropriate services. Typically, the resident will come into the ED and take their sign-out from one of us. The geriatrics fellows and non-teaching hospitalists usually take sign-out over the phone. The entire sign-out process occurs anytime from 6:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. We also reserve this part of the shift to follow up laboratory studies and other diagnostic procedures. Occasionally, we are able to discharge some patients by the end of the shift as well.

On occasion, we will call in the other nocturnist to help out when admissions are too numerous for one physician to handle. This typically occurs towards the end of the work week. We usually require “double coverage” approximately 6–8 nights per month.

Since we instituted the nocturnist program 2 years ago, we have seen great improvements in ED throughput, inpatient bed utilization, patient satisfaction, average length of stay (both in the ED and inpatient), and quality of care. As soon as the emergency physician makes their decision to admit the patient, one of us is already interviewing, examining, and writing admission orders on the patient. This speeds up the process of the patient’s evaluation and allows the patient to be immediately transferred to a quiet room. Furthermore, this allows us to develop a rapport with the patient in the middle of the night, instead of feeling rushed in the morning to round on as many as 20 new patients. This also ensures a good night’s rest for the patient and improves the bed utilization. Moving patients to the floor in a timely fashion also allows for the ED to treat more patients.

Having a nocturnist in the hospital throughout the night allows for a more precise and accurate physical exam, formulation of an impression, and execution of a treatment plan. Physicians who are on-call at home often do not get the complete or correct story from the ED, which can lead to incomplete admission orders and delayed treatment plans. This can lead to unnecessary increases in length of stay. For example, I often admit “chest pain” patients, who by morning have already “ruled out” for an acute coronary event, had a stress test, and are ready for discharge before the “daytime” physician has seen the patient. Another example is diabetic ketoacidosis. I am able to be very aggressive with the treatment plan throughout the night, again decreasing length of stay and hospital costs.

Nocturnism is not only advantageous to the hospital and patients, but also to the nocturnist himself/herself. Dedicated nocturnists have less fatigue and stress. I work only nights, so I do not become excessively tired. My sleep schedule is completely reversed from the norm. This also has many advantages to my personal life. One of these is that I never miss a package delivered to my home!

Indeed, developing this program was a challenge. Initially we sold the idea through a combination of patient safety and revenue. The hospital cannot bill for holding patients in the ED. If we admit patients and move them to an inpatient bed, the hospital can generate this otherwise lost revenue. As with any new idea, we did meet resistance and opposition along the way. However, we were able to overcome these obstacles and build upon them. Once the administration saw the improvements and our productivity, they were immensely pleased. In fact, the administration is already looking at expanding our staffing and our services. Our billing and collections have shown we pay for our cost and generate additional funds for the hospital, despite a poor payer mix. I am excited to see what the future holds for nocturnists, not only in our institution, but across the country. Groups that employ nocturnists probably wonder how they ever survived without them in the past.

Dr. Sabharwal can be contacted at ASabharwal@med.miami.edu.

Jackson Memorial Hospital is an accredited, nonprofit, tertiary care hospital and the major teaching facility for the University of Miami School of Medicine. Jackson Memorial Hospital is one of the busiest centers in the country, with approximately 1500 licensed beds, 225,000 emergency and urgent care visits, and nearly 60,000 admissions to the hospital each year. Furthermore, JMH is the only full-service provider for the uninsured and medically indigent in Miami-Dade County, Florida.

Jackson Memorial Hospital has a broad range of tertiary services and clinical programs designed to serve the entire community. Its medical staff is recognized nationally for the quality of its patient care, teaching, and research. The hospital has over 11,000 full-time employees, approximately 1000 house staff, and nearly 700 clinical attending physicians from the University of Miami School of Medicine alone.

Our medicine department is composed of the following inpatient services: eight general medical teaching teams, three HIV/AIDS teams, one cardiology team, an acute care for the elderly (ACE) unit, one oncology team, and a hospitalist run (non-teaching) service.

Over the last several years a combination of the pressures from outside regulatory agencies and an increasing number of patient admissions brought the admitting process to a breaking point. Teaching services were being held to the admission cap guidelines by the Residency Review Committee (RRC). Furthermore, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) began to enforce strict work-hour rules for all training programs. With these restrictions a fixed number of admissions were admitted to a fixed number of services within a shorter period of the day. In fact, many patients were being held in the emergency department (ED) for as long as 15 hours before an internal medicine service saw the patient or wrote admission orders. We had concerns about safety and the provision of high quality of care for these patients. One of the concerns was that ED physicians were caring for patients who were essentially inpatients while continuing to treat new ED cases.

In an attempt to provide excellent care to our patients, we developed the Emergency Medical Hospitalist Service (EMHS), a nocturnist service. The goals of this service are to: (1) provide attendinglevel care to patients requiring admission, (2) allow the hospital to operate within the admission cap guideline set forth by the RRC, (3) function during the time in which the ACGME work hour limits were affecting the hospital, and (4) operate in a manner that would be at least cost neutral for the institution. We hired two internists (myself and Dr. Roshan K. Rao) to admit patients overnight and begin their inpatient work-up. During this shift, we admit and initiate the inpatient care of all medical admissions for the inpatient services, including the housestaff covered teams. During a typical 12-hour shift, we will admit an average of 10–12 new patients from the ED. In addition to this, there is one resident on each night (termed “night relief”), who provides cross-coverage of existing medical inpatients. We also work in close concert with the newly developed “Patient Placement Coordinator,” who facilitates prompt bed assignments and movement of these patients to in-house beds.

Currently there are two of us, so we make our own schedule depending on each others’ needs. We currently work one week on/one week off, from 8 p.m. To 8 a.m. Towards the end of the shift, we sign out the newly admitted patients to the appropriate services. Typically, the resident will come into the ED and take their sign-out from one of us. The geriatrics fellows and non-teaching hospitalists usually take sign-out over the phone. The entire sign-out process occurs anytime from 6:00 a.m. to 8:00 a.m. We also reserve this part of the shift to follow up laboratory studies and other diagnostic procedures. Occasionally, we are able to discharge some patients by the end of the shift as well.

On occasion, we will call in the other nocturnist to help out when admissions are too numerous for one physician to handle. This typically occurs towards the end of the work week. We usually require “double coverage” approximately 6–8 nights per month.

Since we instituted the nocturnist program 2 years ago, we have seen great improvements in ED throughput, inpatient bed utilization, patient satisfaction, average length of stay (both in the ED and inpatient), and quality of care. As soon as the emergency physician makes their decision to admit the patient, one of us is already interviewing, examining, and writing admission orders on the patient. This speeds up the process of the patient’s evaluation and allows the patient to be immediately transferred to a quiet room. Furthermore, this allows us to develop a rapport with the patient in the middle of the night, instead of feeling rushed in the morning to round on as many as 20 new patients. This also ensures a good night’s rest for the patient and improves the bed utilization. Moving patients to the floor in a timely fashion also allows for the ED to treat more patients.

Having a nocturnist in the hospital throughout the night allows for a more precise and accurate physical exam, formulation of an impression, and execution of a treatment plan. Physicians who are on-call at home often do not get the complete or correct story from the ED, which can lead to incomplete admission orders and delayed treatment plans. This can lead to unnecessary increases in length of stay. For example, I often admit “chest pain” patients, who by morning have already “ruled out” for an acute coronary event, had a stress test, and are ready for discharge before the “daytime” physician has seen the patient. Another example is diabetic ketoacidosis. I am able to be very aggressive with the treatment plan throughout the night, again decreasing length of stay and hospital costs.

Nocturnism is not only advantageous to the hospital and patients, but also to the nocturnist himself/herself. Dedicated nocturnists have less fatigue and stress. I work only nights, so I do not become excessively tired. My sleep schedule is completely reversed from the norm. This also has many advantages to my personal life. One of these is that I never miss a package delivered to my home!

Indeed, developing this program was a challenge. Initially we sold the idea through a combination of patient safety and revenue. The hospital cannot bill for holding patients in the ED. If we admit patients and move them to an inpatient bed, the hospital can generate this otherwise lost revenue. As with any new idea, we did meet resistance and opposition along the way. However, we were able to overcome these obstacles and build upon them. Once the administration saw the improvements and our productivity, they were immensely pleased. In fact, the administration is already looking at expanding our staffing and our services. Our billing and collections have shown we pay for our cost and generate additional funds for the hospital, despite a poor payer mix. I am excited to see what the future holds for nocturnists, not only in our institution, but across the country. Groups that employ nocturnists probably wonder how they ever survived without them in the past.

Dr. Sabharwal can be contacted at ASabharwal@med.miami.edu.