User login

Childbirth-related PTSD: How it differs and who’s at risk

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

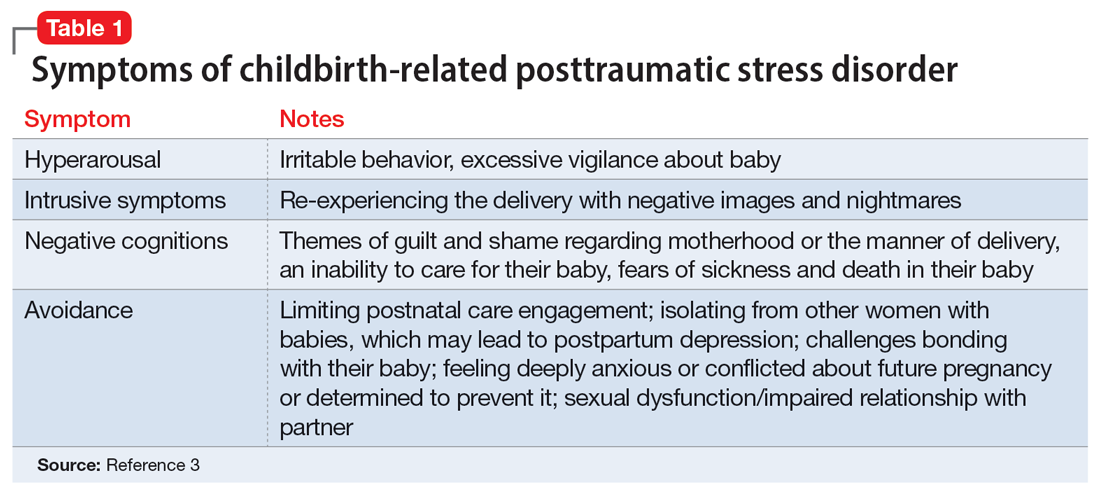

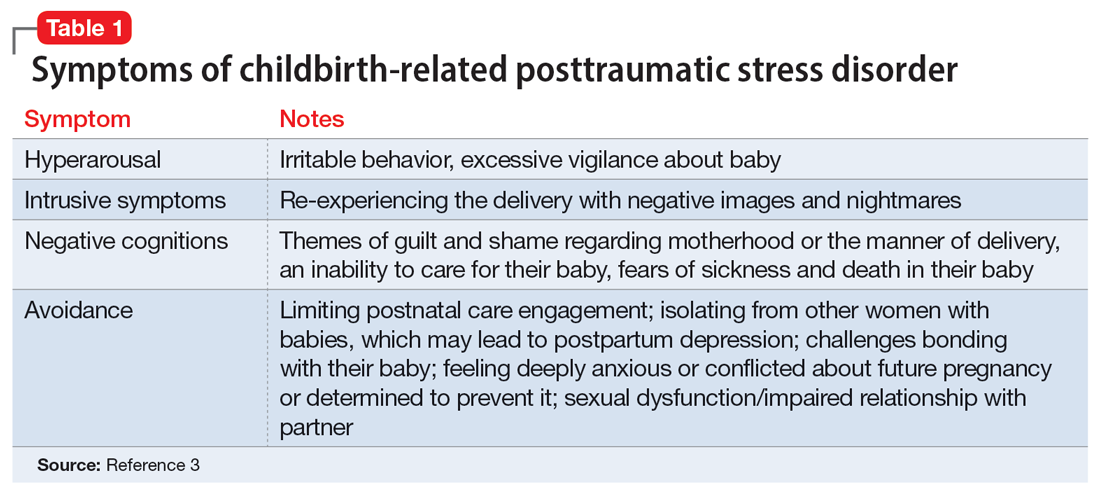

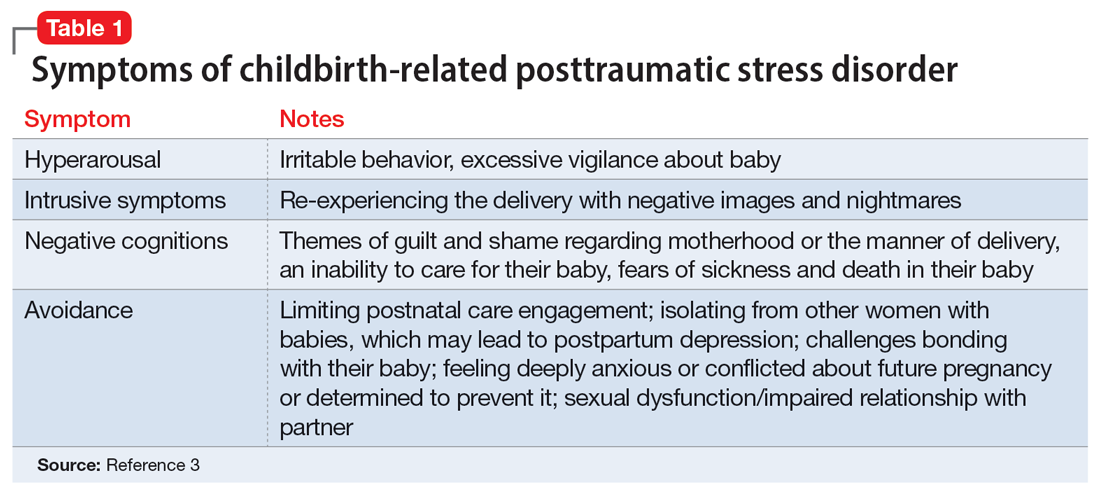

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

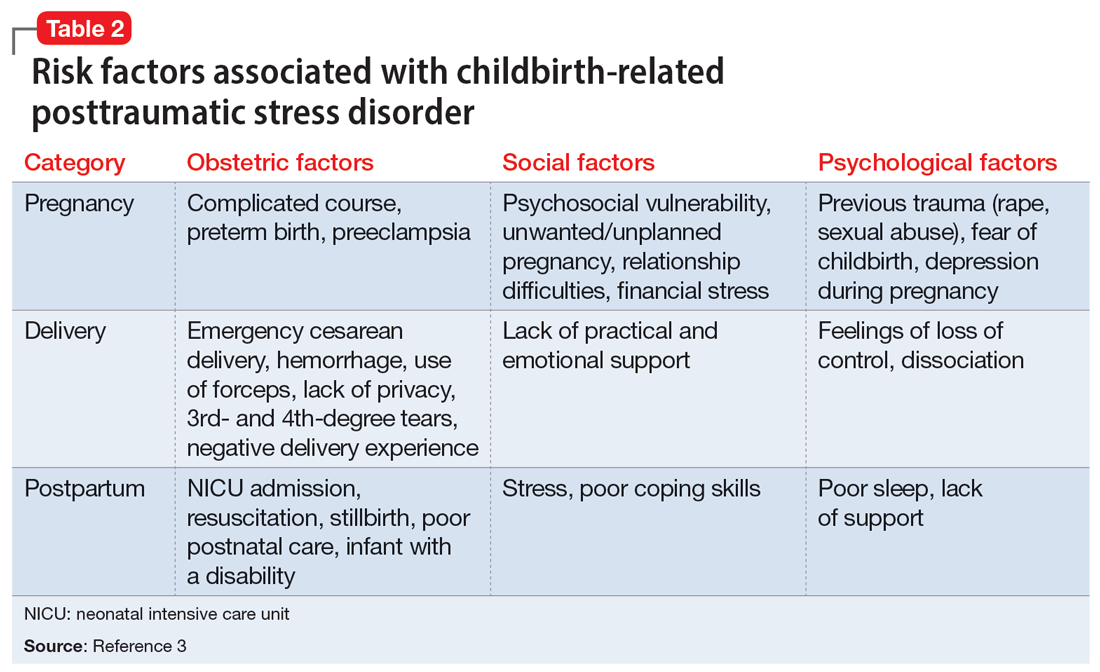

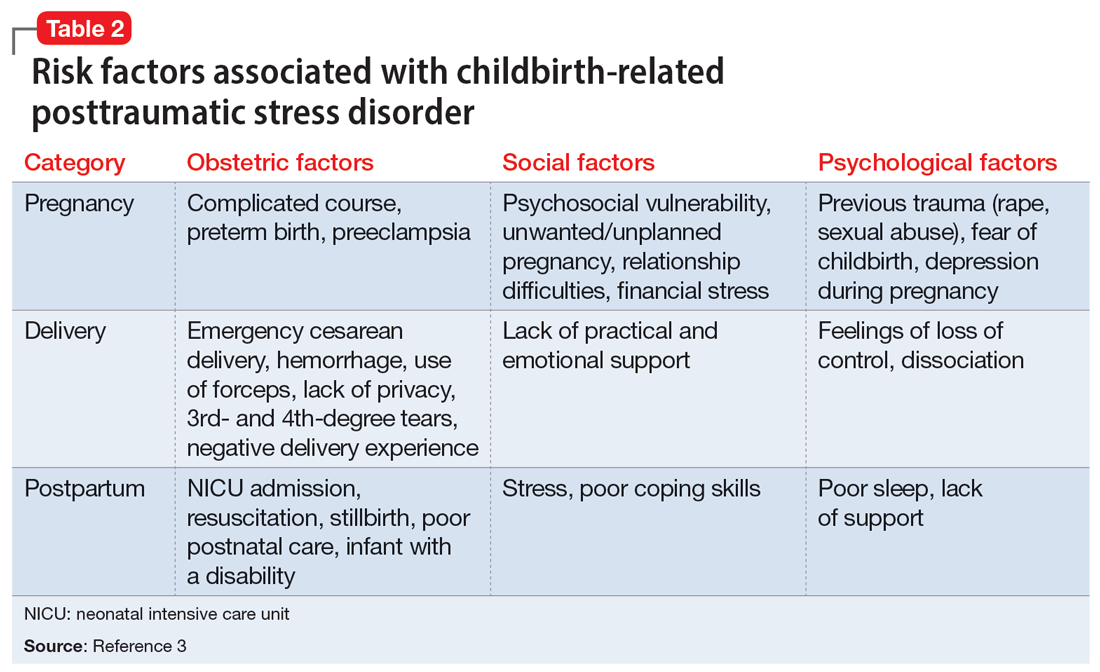

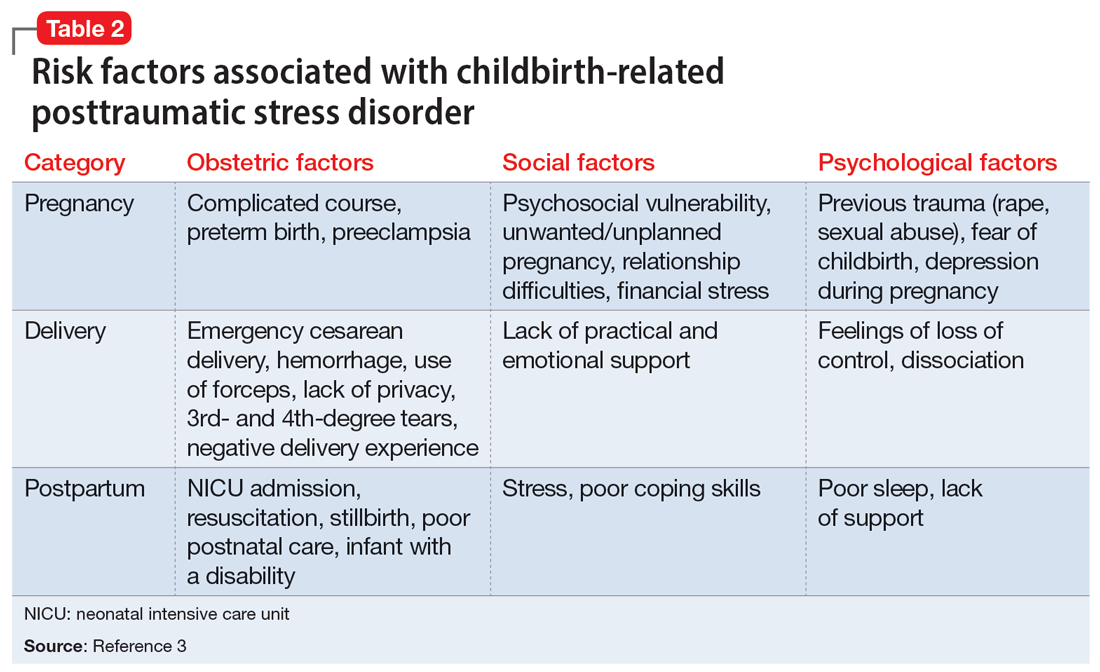

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

Differentiating pediatric schizotypal disorder from schizophrenia and autism

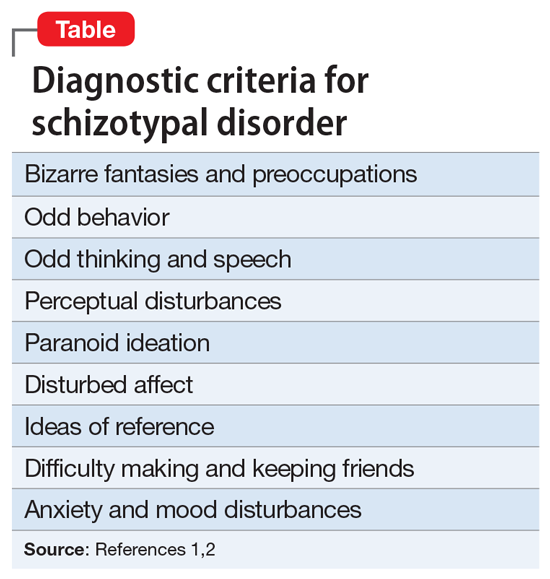

Schizotypal disorder is a complex condition that is characterized by cognitive-perceptual impairments, oddness, disorganization, and interpersonal difficulties. It often is unrecognized or underdiagnosed. In DSM-5, schizotypal disorder is categorized a personality disorder, but it is also considered part of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 The diagnostic criteria for schizotypal disorder are outlined in the Table.1,2

Although schizotypal disorder has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 4% in the general population of the United States,2 it can present during childhood or adolescence and may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms in pediatric patients.3 Schizotypal disorder of childhood (SDC) can present with significant overlap with several pediatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), all of which may include psychotic symptoms and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. This overlap, combined with the lack of awareness of schizotypal disorder, can pose a diagnostic challenge. Better recognition of SDC could result in earlier and more effective treatment. In this article, we provide tips for differentiating SDC from childhood-onset schizophrenia and from ASD.

Differentiating SDC from schizophrenia

SDC may be mistaken for childhood-onset schizophrenia due to its perceptual disturbances (which may be interpreted as visual or auditory hallucinations), bizarre fantasies (which may be mistaken for overt delusions), paranoia, and odd behavior. Two ways to distinguish SDC from childhood schizophrenia are by clinical course and by severity of negative psychotic symptoms.

SDC tends to have an overall stable clinical course,4 with patients experiencing periods of time when they exhibit a more normal mental status complemented by fluctuations in symptom severity, which are exacerbated by stressors and followed by a return to baseline.3 SDC psychotic symptoms are predominantly positive, and patients typically do not demonstrate negative features beyond social difficulties. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is typically progressive and disabling, with worsening severity over time, and is much more likely to incorporate prominent negative symptoms.3

Differentiating SDC from ASD

SDC also demonstrates considerable diagnostic overlap with ASD, especially with regards to inappropriate affect; odd thinking, behavior, and speech; and social difficulties. Further complicating the diagnosis, ASD and SDC are comorbid in approximately 40% of ASD cases.3,5 The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids demonstrates validity in diagnosing schizotypal disorder in patients with comorbid ASD.5,6 For clinicians without easy access to advanced testing, 2 ways to distinguish SDC from ASD are the content of the odd behavior and thoughts, and the patient’s reaction to social deficits.

In SDC, odd behavior and thoughts most often revolve around daydreaming and a focus on “elaborate inner fantasies.”3,6 Unlike in ASD, in patients with SDC, behaviors don’t typically involve stereotyped mannerisms, the patient is unlikely to have rigid interests (apart from their fantasies), and there is not a particular focus on detail in the external world.3,6 Notably, imaginary companions are common in SDC; children with ASD are less likely to have an imaginary companion compared with children with SDC or those with no psychiatric diagnosis.6 Patients with SDC have social difficulties (often due to social anxiety stemming from their paranoia) but usually seek out interaction and are bothered by alienation, while patients with ASD may have less interest in social engagement.6

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(2):53-67. doi:10.4088/pcc.08m00679

3. Tonge BJ, Testa R, Díaz-Arteche C, et al. Schizotypal disorder in children—a neglected diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. 2020;1(1):sgaa048. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa048

4. Asarnow JR. Childhood-onset schizotypal disorder: a follow-up study and comparison with childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(3):395-402.

5. Jones HP, Testa RR, Ross N, et al. The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids: a useful measure of childhood schizotypal personality disorder. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:635732. doi:10.1155/2015/635732

6. Poletti M, Raballo A. Childhood schizotypal features vs. high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: developmental overlaps and phenomenological differences. Schizophr Res. 2020;223:53-58. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.027

Schizotypal disorder is a complex condition that is characterized by cognitive-perceptual impairments, oddness, disorganization, and interpersonal difficulties. It often is unrecognized or underdiagnosed. In DSM-5, schizotypal disorder is categorized a personality disorder, but it is also considered part of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 The diagnostic criteria for schizotypal disorder are outlined in the Table.1,2

Although schizotypal disorder has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 4% in the general population of the United States,2 it can present during childhood or adolescence and may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms in pediatric patients.3 Schizotypal disorder of childhood (SDC) can present with significant overlap with several pediatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), all of which may include psychotic symptoms and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. This overlap, combined with the lack of awareness of schizotypal disorder, can pose a diagnostic challenge. Better recognition of SDC could result in earlier and more effective treatment. In this article, we provide tips for differentiating SDC from childhood-onset schizophrenia and from ASD.

Differentiating SDC from schizophrenia

SDC may be mistaken for childhood-onset schizophrenia due to its perceptual disturbances (which may be interpreted as visual or auditory hallucinations), bizarre fantasies (which may be mistaken for overt delusions), paranoia, and odd behavior. Two ways to distinguish SDC from childhood schizophrenia are by clinical course and by severity of negative psychotic symptoms.

SDC tends to have an overall stable clinical course,4 with patients experiencing periods of time when they exhibit a more normal mental status complemented by fluctuations in symptom severity, which are exacerbated by stressors and followed by a return to baseline.3 SDC psychotic symptoms are predominantly positive, and patients typically do not demonstrate negative features beyond social difficulties. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is typically progressive and disabling, with worsening severity over time, and is much more likely to incorporate prominent negative symptoms.3

Differentiating SDC from ASD

SDC also demonstrates considerable diagnostic overlap with ASD, especially with regards to inappropriate affect; odd thinking, behavior, and speech; and social difficulties. Further complicating the diagnosis, ASD and SDC are comorbid in approximately 40% of ASD cases.3,5 The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids demonstrates validity in diagnosing schizotypal disorder in patients with comorbid ASD.5,6 For clinicians without easy access to advanced testing, 2 ways to distinguish SDC from ASD are the content of the odd behavior and thoughts, and the patient’s reaction to social deficits.

In SDC, odd behavior and thoughts most often revolve around daydreaming and a focus on “elaborate inner fantasies.”3,6 Unlike in ASD, in patients with SDC, behaviors don’t typically involve stereotyped mannerisms, the patient is unlikely to have rigid interests (apart from their fantasies), and there is not a particular focus on detail in the external world.3,6 Notably, imaginary companions are common in SDC; children with ASD are less likely to have an imaginary companion compared with children with SDC or those with no psychiatric diagnosis.6 Patients with SDC have social difficulties (often due to social anxiety stemming from their paranoia) but usually seek out interaction and are bothered by alienation, while patients with ASD may have less interest in social engagement.6

Schizotypal disorder is a complex condition that is characterized by cognitive-perceptual impairments, oddness, disorganization, and interpersonal difficulties. It often is unrecognized or underdiagnosed. In DSM-5, schizotypal disorder is categorized a personality disorder, but it is also considered part of the schizophrenia spectrum disorders.1 The diagnostic criteria for schizotypal disorder are outlined in the Table.1,2

Although schizotypal disorder has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 4% in the general population of the United States,2 it can present during childhood or adolescence and may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis for psychotic symptoms in pediatric patients.3 Schizotypal disorder of childhood (SDC) can present with significant overlap with several pediatric diagnoses, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), all of which may include psychotic symptoms and difficulties in interpersonal relationships. This overlap, combined with the lack of awareness of schizotypal disorder, can pose a diagnostic challenge. Better recognition of SDC could result in earlier and more effective treatment. In this article, we provide tips for differentiating SDC from childhood-onset schizophrenia and from ASD.

Differentiating SDC from schizophrenia

SDC may be mistaken for childhood-onset schizophrenia due to its perceptual disturbances (which may be interpreted as visual or auditory hallucinations), bizarre fantasies (which may be mistaken for overt delusions), paranoia, and odd behavior. Two ways to distinguish SDC from childhood schizophrenia are by clinical course and by severity of negative psychotic symptoms.

SDC tends to have an overall stable clinical course,4 with patients experiencing periods of time when they exhibit a more normal mental status complemented by fluctuations in symptom severity, which are exacerbated by stressors and followed by a return to baseline.3 SDC psychotic symptoms are predominantly positive, and patients typically do not demonstrate negative features beyond social difficulties. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is typically progressive and disabling, with worsening severity over time, and is much more likely to incorporate prominent negative symptoms.3

Differentiating SDC from ASD

SDC also demonstrates considerable diagnostic overlap with ASD, especially with regards to inappropriate affect; odd thinking, behavior, and speech; and social difficulties. Further complicating the diagnosis, ASD and SDC are comorbid in approximately 40% of ASD cases.3,5 The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids demonstrates validity in diagnosing schizotypal disorder in patients with comorbid ASD.5,6 For clinicians without easy access to advanced testing, 2 ways to distinguish SDC from ASD are the content of the odd behavior and thoughts, and the patient’s reaction to social deficits.

In SDC, odd behavior and thoughts most often revolve around daydreaming and a focus on “elaborate inner fantasies.”3,6 Unlike in ASD, in patients with SDC, behaviors don’t typically involve stereotyped mannerisms, the patient is unlikely to have rigid interests (apart from their fantasies), and there is not a particular focus on detail in the external world.3,6 Notably, imaginary companions are common in SDC; children with ASD are less likely to have an imaginary companion compared with children with SDC or those with no psychiatric diagnosis.6 Patients with SDC have social difficulties (often due to social anxiety stemming from their paranoia) but usually seek out interaction and are bothered by alienation, while patients with ASD may have less interest in social engagement.6

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(2):53-67. doi:10.4088/pcc.08m00679

3. Tonge BJ, Testa R, Díaz-Arteche C, et al. Schizotypal disorder in children—a neglected diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. 2020;1(1):sgaa048. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa048

4. Asarnow JR. Childhood-onset schizotypal disorder: a follow-up study and comparison with childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(3):395-402.

5. Jones HP, Testa RR, Ross N, et al. The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids: a useful measure of childhood schizotypal personality disorder. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:635732. doi:10.1155/2015/635732

6. Poletti M, Raballo A. Childhood schizotypal features vs. high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: developmental overlaps and phenomenological differences. Schizophr Res. 2020;223:53-58. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.027

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Pulay AJ, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV schizotypal personality disorder: results from the wave 2 national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;11(2):53-67. doi:10.4088/pcc.08m00679

3. Tonge BJ, Testa R, Díaz-Arteche C, et al. Schizotypal disorder in children—a neglected diagnosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin Open. 2020;1(1):sgaa048. doi:10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa048

4. Asarnow JR. Childhood-onset schizotypal disorder: a follow-up study and comparison with childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(3):395-402.

5. Jones HP, Testa RR, Ross N, et al. The Melbourne Assessment of Schizotypy in Kids: a useful measure of childhood schizotypal personality disorder. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:635732. doi:10.1155/2015/635732

6. Poletti M, Raballo A. Childhood schizotypal features vs. high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: developmental overlaps and phenomenological differences. Schizophr Res. 2020;223:53-58. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2020.09.027