User login

Childbirth-related PTSD: How it differs and who’s at risk

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

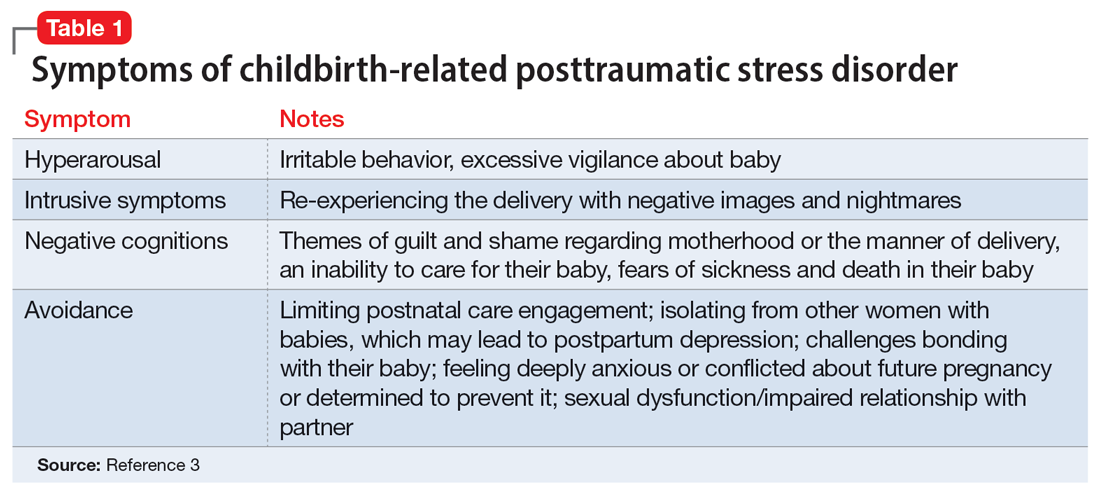

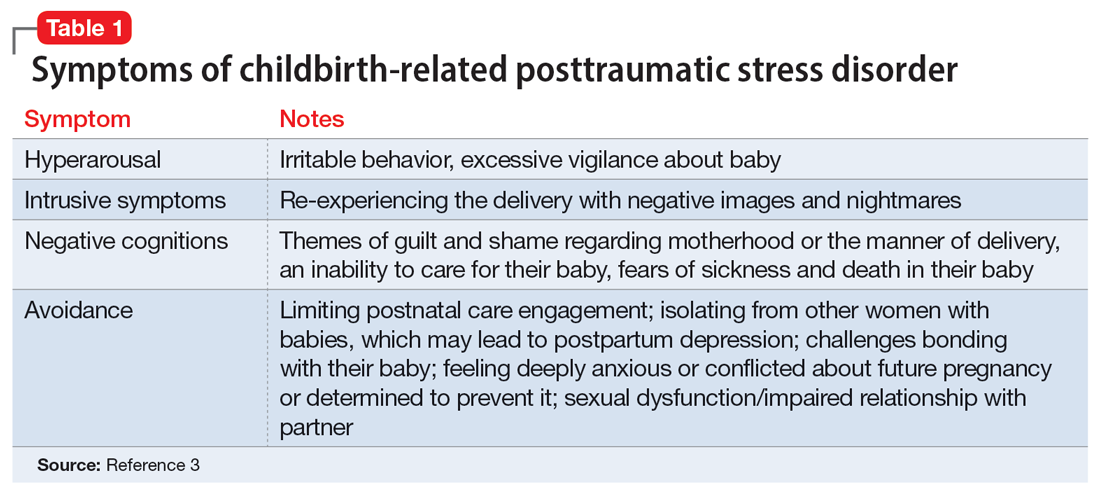

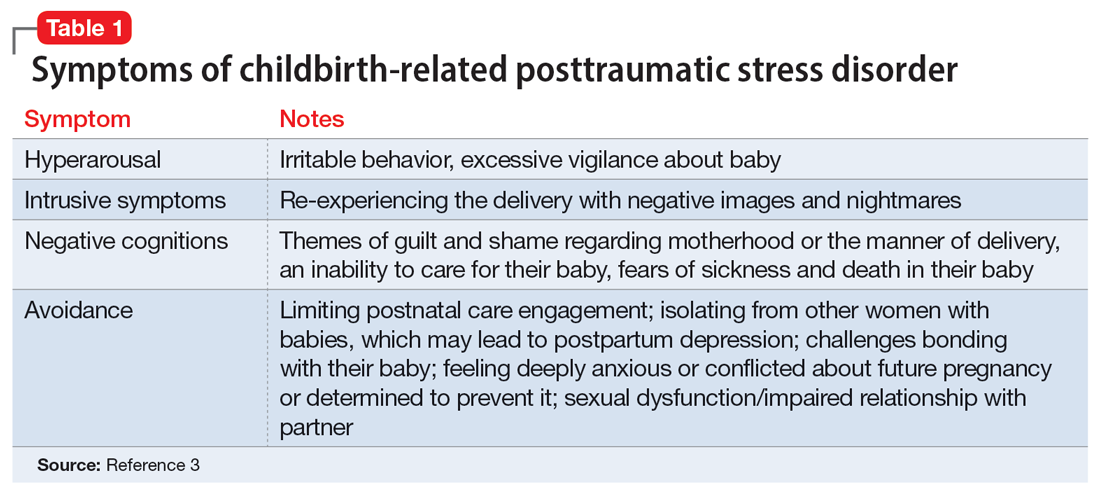

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

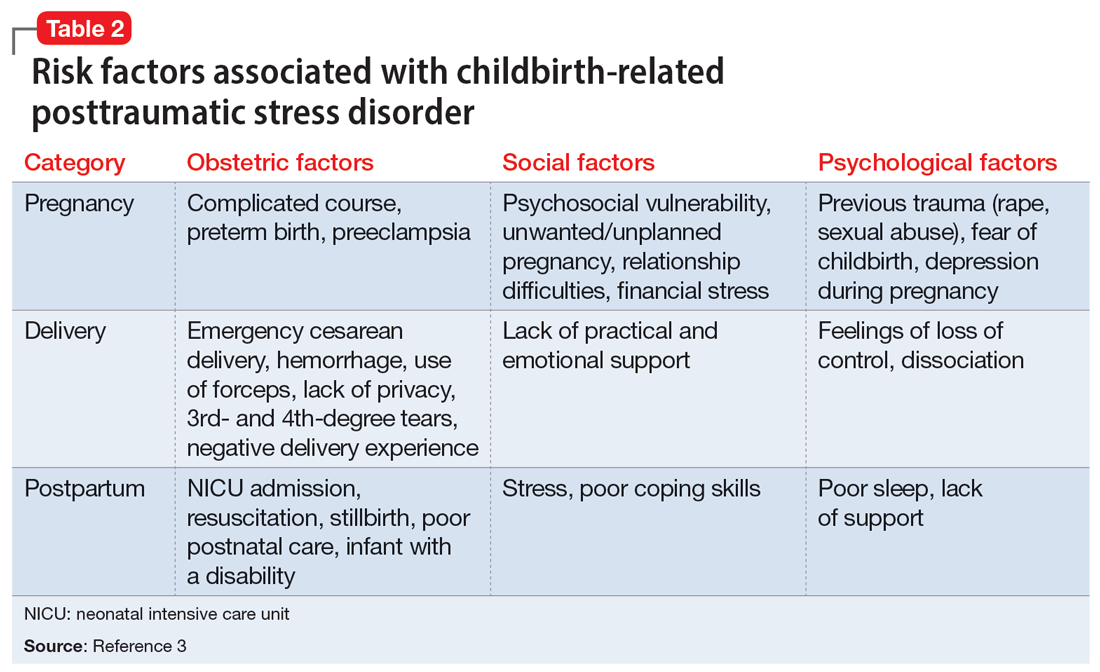

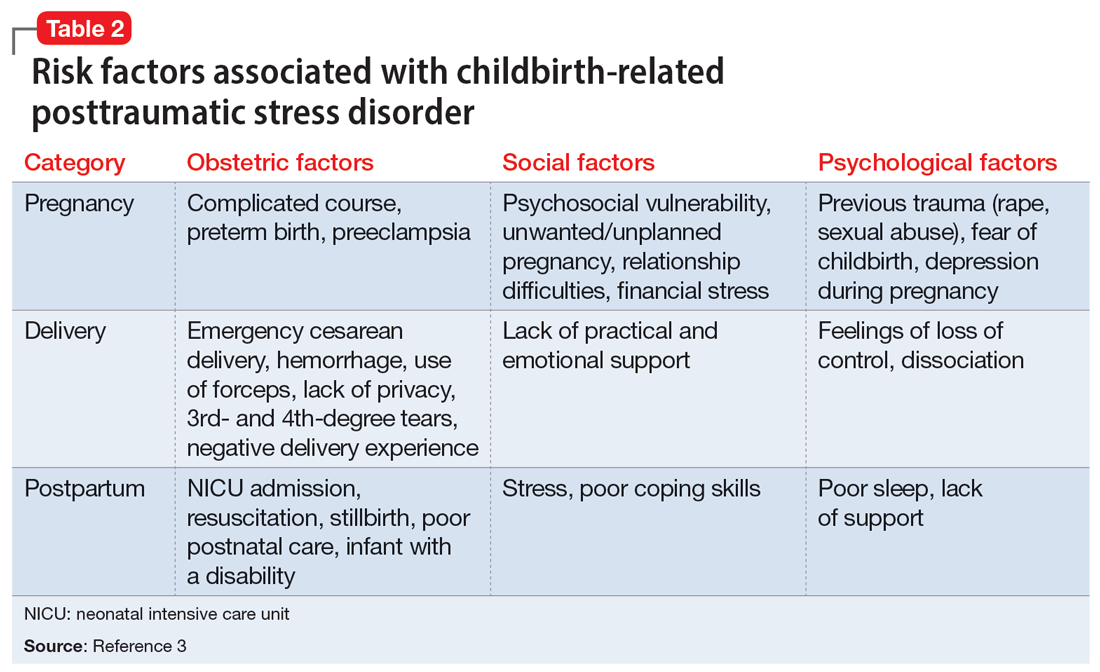

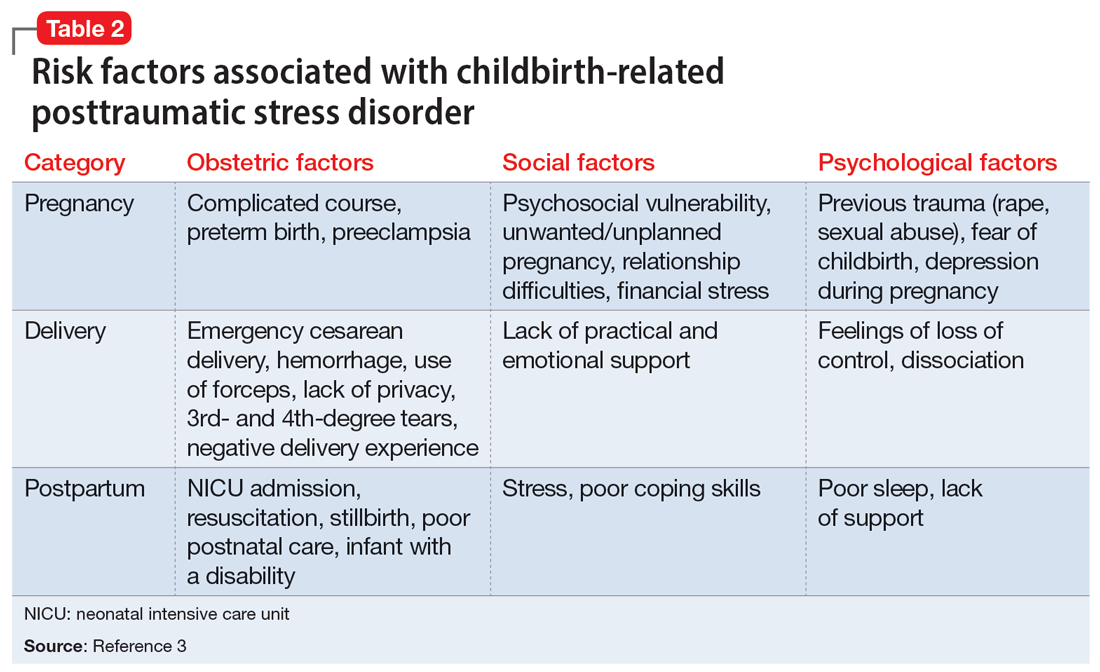

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

Childbirth-related posttraumatic stress disorder (CB-PTSD) is a form of PTSD that can develop related to trauma surrounding the events of giving birth. It affects approximately 5% of women after any birth, which is similar to the rate of PTSD after experiencing a natural disaster.1 Up to 17% of women may have posttraumatic symptoms in the postpartum period.1 Despite the high prevalence of CB-PTSD, many psychiatric clinicians have not incorporated screening for and management of CB-PTSD into their practice.

This is partly because childbirth has been conceptualized as a “stressful but positive life event.”2 Historically, childbirth was not recognized as a traumatic event; for example, in DSM-III-R, the criteria for trauma in PTSD required an event outside the range of usual human experience, and childbirth was implicitly excluded as being too common to be traumatic. In the past decade, this clinical phenomenon has been more formally recognized and studied.2

CB-PTSD presents with symptoms similar to those of other forms of PTSD, with some nuances, as outlined in Table 1.3 Avoidance can be the predominant symptom; this can affect mothers’ engagement in postnatal care and is a major risk factor for postpartum depression.3

Many risk factors in the peripartum period can impact the development of CB-PTSD (Table 23). The most significant risk factor is whether the patient views the delivery of their baby as a subjectively negative experience, regardless of the presence or lack of peripartum complications.1 However, parents of infants who require treatment in a neonatal intensive care unit and women who require emergency medical treatment following delivery are at higher risk.

Screening and treatment

Ideally, every woman should be screened for CB-PTSD by their psychiatrist or obstetrician during a postpartum visit at least 1 month after delivery. In particular, high-risk populations and women with subjectively negative birth experiences should be screened, as well as women with postpartum depression that may have been precipitated or perpetuated by a traumatic experience. The City Birth Trauma Scale is a free 31-item self-report scale that can be used for such screening. It addresses both general and birth-related symptoms and is validated in multiple languages.4

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and prazosin may be helpful for symptomatic treatment of CB-PTSD. Ongoing research studying the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for CB-PTSD has yielded promising results but is limited in its generalizability.

Many women who develop CB-PTSD choose to get pregnant again. Psychiatrists can apply the principles of trauma-informed care and collaborate with obstetric and pediatric physicians to reduce the risk of retraumatization. It is critical to identify at-risk women and educate and prepare them for their next delivery experience. By focusing on communication, informed consent, and emotional support, we can do our best to prevent the recurrence of CB-PTSD.

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

1. Dekel S, Stuebe C, Dishy G. Childbirth induced posttraumatic stress syndrome: a systematic review of prevalence and risk factors. Front Psych. 2017;8:560. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00560

2. Horesh D, Garthus-Niegel S, Horsch A. Childbirth-related PTSD: is it a unique post-traumatic disorder? J Reprod Infant Psych. 2021;39(3):221-224. doi:10.1080/02646838.2021.1930739

3. Kranenburg L, Lambregtse-van den Berg M, Stramrood C. Traumatic childbirth experience and childbirth-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a contemporary overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):2775. doi:10.3390/ijerph20042775

4. Ayers S, Wright DB, Thornton A. Development of a measure of postpartum PTSD: The City Birth Trauma Scale. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:409. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00409

A pivot in training: My path to reproductive psychiatry

In March 2020, as I was wheeling my patient into the operating room to perform a Caesarean section, covered head-to-toe in COVID personal protective equipment, my phone rang. It was Jody Schindelheim, MD, Director of the Psychiatry Residency Program at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, calling to offer me a PGY-2 spot in their program.

As COVID upended the world, I was struggling with my own major change. My path had been planned since before medical school: I would grind through a 4-year OB/GYN residency, complete a fellowship, and establish myself as a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist. My personal statement emphasized my dream that no woman should be made to feel useless based on infertility. OB/GYN, genetics, and ultrasound were my favorite rotations at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

However, 6 months into my OB/GYN intern year, I grew curious about the possibility of a future in reproductive psychiatry and women’s mental health. This decision was not easy. As someone who loved the adrenaline rush of delivering babies and performing surgery, I had paid little attention to psychiatry in medical school. However, my experience in gynecologic oncology in January 2020 made me realize my love of stories and trauma-informed care. I recall a woman, cachectic with only days left to live due to ovarian cancer, talking to me about her trauma and the power of her lifelong partner. Another woman, experiencing complications from chemotherapy to treat fallopian tube cancer, shared about her coping skill of chair yoga.

Fulfilling an unmet need

As I spent time with these 2 women and heard their stories, I felt compelled to help them with these psychological challenges. As a gynecologist, I addressed their physical needs, but not their personal needs. I spoke to many psychiatrists, including reproductive psychiatrists, in New York, who shared their stories and taught me about the prevalence of postpartum depression and psychosis. After caring for hundreds of pregnant and postpartum women in the Bronx, I thought about the unmet need for women’s mental health and how this career change could still fulfill my purpose of helping women feel empowered regardless of their fertility status.

In the inpatient and outpatient settings at Tufts, I have loved hearing my patients’ stories and providing continuity of care with medical management and therapy. My mentors in reproductive psychiatry inspired me to create the Reproductive Psychiatry Trainee Interest Group (https://www.repropsychtrainees.com), a national group for the burgeoning field that now has more than 650 members. With monthly lectures, journal clubs, and book clubs, I have surrounded myself with like-minded individuals who love learning about the perinatal, postpartum, and perimenopausal experiences.

As I prepare to begin a full-time faculty position in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, I know I have found my joy and my calling. I once feared the life of a psychiatrist would be too sedentary for someone accustomed to the pace of OB/GYN. Now I know that my patients’ stories are all the motivation I need.

In March 2020, as I was wheeling my patient into the operating room to perform a Caesarean section, covered head-to-toe in COVID personal protective equipment, my phone rang. It was Jody Schindelheim, MD, Director of the Psychiatry Residency Program at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, calling to offer me a PGY-2 spot in their program.

As COVID upended the world, I was struggling with my own major change. My path had been planned since before medical school: I would grind through a 4-year OB/GYN residency, complete a fellowship, and establish myself as a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist. My personal statement emphasized my dream that no woman should be made to feel useless based on infertility. OB/GYN, genetics, and ultrasound were my favorite rotations at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

However, 6 months into my OB/GYN intern year, I grew curious about the possibility of a future in reproductive psychiatry and women’s mental health. This decision was not easy. As someone who loved the adrenaline rush of delivering babies and performing surgery, I had paid little attention to psychiatry in medical school. However, my experience in gynecologic oncology in January 2020 made me realize my love of stories and trauma-informed care. I recall a woman, cachectic with only days left to live due to ovarian cancer, talking to me about her trauma and the power of her lifelong partner. Another woman, experiencing complications from chemotherapy to treat fallopian tube cancer, shared about her coping skill of chair yoga.

Fulfilling an unmet need

As I spent time with these 2 women and heard their stories, I felt compelled to help them with these psychological challenges. As a gynecologist, I addressed their physical needs, but not their personal needs. I spoke to many psychiatrists, including reproductive psychiatrists, in New York, who shared their stories and taught me about the prevalence of postpartum depression and psychosis. After caring for hundreds of pregnant and postpartum women in the Bronx, I thought about the unmet need for women’s mental health and how this career change could still fulfill my purpose of helping women feel empowered regardless of their fertility status.

In the inpatient and outpatient settings at Tufts, I have loved hearing my patients’ stories and providing continuity of care with medical management and therapy. My mentors in reproductive psychiatry inspired me to create the Reproductive Psychiatry Trainee Interest Group (https://www.repropsychtrainees.com), a national group for the burgeoning field that now has more than 650 members. With monthly lectures, journal clubs, and book clubs, I have surrounded myself with like-minded individuals who love learning about the perinatal, postpartum, and perimenopausal experiences.

As I prepare to begin a full-time faculty position in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, I know I have found my joy and my calling. I once feared the life of a psychiatrist would be too sedentary for someone accustomed to the pace of OB/GYN. Now I know that my patients’ stories are all the motivation I need.

In March 2020, as I was wheeling my patient into the operating room to perform a Caesarean section, covered head-to-toe in COVID personal protective equipment, my phone rang. It was Jody Schindelheim, MD, Director of the Psychiatry Residency Program at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, calling to offer me a PGY-2 spot in their program.

As COVID upended the world, I was struggling with my own major change. My path had been planned since before medical school: I would grind through a 4-year OB/GYN residency, complete a fellowship, and establish myself as a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist. My personal statement emphasized my dream that no woman should be made to feel useless based on infertility. OB/GYN, genetics, and ultrasound were my favorite rotations at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx.

However, 6 months into my OB/GYN intern year, I grew curious about the possibility of a future in reproductive psychiatry and women’s mental health. This decision was not easy. As someone who loved the adrenaline rush of delivering babies and performing surgery, I had paid little attention to psychiatry in medical school. However, my experience in gynecologic oncology in January 2020 made me realize my love of stories and trauma-informed care. I recall a woman, cachectic with only days left to live due to ovarian cancer, talking to me about her trauma and the power of her lifelong partner. Another woman, experiencing complications from chemotherapy to treat fallopian tube cancer, shared about her coping skill of chair yoga.

Fulfilling an unmet need

As I spent time with these 2 women and heard their stories, I felt compelled to help them with these psychological challenges. As a gynecologist, I addressed their physical needs, but not their personal needs. I spoke to many psychiatrists, including reproductive psychiatrists, in New York, who shared their stories and taught me about the prevalence of postpartum depression and psychosis. After caring for hundreds of pregnant and postpartum women in the Bronx, I thought about the unmet need for women’s mental health and how this career change could still fulfill my purpose of helping women feel empowered regardless of their fertility status.

In the inpatient and outpatient settings at Tufts, I have loved hearing my patients’ stories and providing continuity of care with medical management and therapy. My mentors in reproductive psychiatry inspired me to create the Reproductive Psychiatry Trainee Interest Group (https://www.repropsychtrainees.com), a national group for the burgeoning field that now has more than 650 members. With monthly lectures, journal clubs, and book clubs, I have surrounded myself with like-minded individuals who love learning about the perinatal, postpartum, and perimenopausal experiences.

As I prepare to begin a full-time faculty position in psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, I know I have found my joy and my calling. I once feared the life of a psychiatrist would be too sedentary for someone accustomed to the pace of OB/GYN. Now I know that my patients’ stories are all the motivation I need.