User login

Should we stop aspirin before noncardiac surgery?

In patients with cardiac stents, do not stop aspirin. If the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefit (eg, with intracranial procedures), an informed discussion involving the surgeon, cardiologist, and patient is critical to ascertain risks vs benefits.

In patients using aspirin for secondary prevention, the decision depends on the patient’s cardiac status and an assessment of risk vs benefit. Aspirin has no role in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who are at low risk of a major adverse cardiac event.1,2

Aspirin used for secondary prevention reduces rates of death from vascular causes,3 but data on the magnitude of benefit in the perioperative setting are still evolving. In patients with coronary stents, continuing aspirin is beneficial,4,5 whereas stopping it is associated with an increased risk of acute stent thrombosis, which causes significant morbidity and mortality.6

SURGERY AND THROMBOTIC RISK: WHY CONSIDER ASPIRIN?

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study7 prospectively screened 15,133 patients for myocardial injury with troponin T levels daily for the first 3 consecutive postoperative days; 1,263 (8%) of the patients had a troponin elevation of 0.03 ng/mL or higher. The 30-day mortality rate in this group was 9.8%, compared with 1.1% in patients with a troponin T level of less than 0.03 ng/mL (odds ratio 10.07; 95% confidence interval [CI] 7.84–12.94; P < .001).8 The higher the peak troponin T concentration, the higher the risk of death within 30 days:

- 0.01 ng/mL or less, risk 1.0%

- 0.02 ng/mL, risk 4.0%

- 0.03 to 0.29 ng/mL, risk 9.3%

- 0.30 ng/mL or greater, risk 16.9%.7

Myocardial injury is a common postoperative vascular complication.7 Myocardial infarction (MI) or injury perioperatively increases the risk of death: 1 in 10 patients dies within 30 days after surgery.8

Surgery creates substantial physiologic stress through factors such as fasting, anesthesia, intubation, surgical trauma, extubation, and pain. It promotes coagulation9 and inflammation with activation of platelets,10 potentially leading to thrombosis.11 Coronary thrombosis secondary to plaque rupture11,12 can result in perioperative MI. Perioperative hemodynamic variability, anemia, and hypoxia can lead to demand-supply mismatch and also cause cardiac ischemia.

Aspirin is an antiplatelet agent that irreversibly inhibits platelet aggregation by blocking the formation of cyclooxygenase. It has been used for several decades as an antithrombotic agent in primary and secondary prevention. However, its benefit in primary prevention is uncertain, and the magnitude of antithrombotic benefit must be balanced against the risk of bleeding.

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration13 performed a systematic review of 6 primary prevention trials involving 95,000 patients and found that aspirin therapy was associated with a 12% reduction in serious vascular events, which occurred in 0.51% of patients taking aspirin per year vs 0.57% of controls (P = .0001). However, aspirin also increased the risk of major bleeding, at a rate of 0.10% vs 0.07% per year (P < .0001), with 2 bleeding events for every avoided vascular event.13

WILL ASPIRIN PROTECT PATIENTS AT CARDIAC RISK?

The second Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation trial (POISE 2),1 in patients with atherosclerotic disease or at risk for it, found that giving aspirin in the perioperative period did not reduce the rate of death or nonfatal MI, but increased the risk of a major bleeding event.

The trial included 10,010 patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who were randomly assigned to receive aspirin or placebo. The aspirin arm included 2 groups: patients who were not on aspirin (initiation arm), and patients on aspirin at the time of randomization (continuation arm).

Death or nonfatal MI (the primary outcome) occurred in 7.0% of patients on aspirin vs 7.1% of patients receiving placebo (hazard ratio [HR] 0.99, 95% CI 0.86–1.15, P = .92). The risk of major bleeding was 4.6% in the aspirin group vs 3.8% in the placebo group (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01–1.49, P = .04).1

George et al,14 in a prospective observational study in a single tertiary care center, found that fewer patients with myocardial injury in noncardiac surgery died if they took aspirin or clopidogrel postoperatively. Conversely, lack of antithrombotic therapy was an independent predictor of death (P < .001). The mortality rate in patients with myocardial injury who were on antithrombotic therapy postoperatively was 6.7%, compared with 12.1% in those without postoperative antithrombotic therapy (estimated number needed to treat, 19).14

PATIENTS WITH CORONARY STENTS UNDERGOING NONCARDIAC SURGERY

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) accounts for 3.6% of all operating-room procedures in the United States,15 and 20% to 35% of patients who undergo PCI undergo noncardiac surgery within 2 years of stent implantation.16,17

Antiplatelet therapy is discontinued in about 20% of patients with previous PCI who undergo noncardiac surgery.18

Observational data have shown that stopping antiplatelet therapy in patients with previous PCI with stent placement who undergo noncardiac surgery is the single most important predictor of stent thrombosis and death.19–21 The risk increases if the interval between stent implantation and surgery is shorter, especially within 180 days.16,17 Patients who have stent thrombosis are at significantly higher risk of death.

Graham et al4 conducted a subgroup analysis of the POISE 2 trial comparing aspirin and placebo in 470 patients who had undergone PCI (427 had stent placement, and the rest had angioplasty or an unspecified type of PCI); 234 patients received aspirin and 236 placebo. The median time from stent implantation to surgery was 5.3 years.

Of the patients in the aspirin arm, 14 (6%) had the primary outcome of death or nonfatal MI compared with 27 patients (11.5%) in the placebo arm (absolute risk reduction 5.5%, 95% CI 0.4%–10.5%). The result, which differed from that in the primary trial,1 was due to reduction in MI in the PCI subgroup on aspirin. PCI patients who were on aspirin did not have increased bleeding risk. This subgroup analysis, albeit small and limited, suggests that continuing low-dose aspirin in patients with previous PCI, irrespective of the type of stent or the time from stent implantations, minimizes the risk of perioperative MI.

GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Routine perioperative use of aspirin increases the risk of bleeding without a reduction in ischemic events.1 Patients with prior PCI are at increased risk of acute stent thrombosis when antiplatelet medications are discontinued.20,21 Available data, although limited, support continuing low-dose aspirin without interruption in the perioperative period in PCI patients,4 as do the guidelines from the American College of Cardiology.5

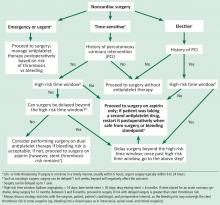

We propose a management algorithm for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery on antiplatelet therapy that takes into consideration whether the surgery is urgent, elective, or time-sensitive (Figure 1). It is imperative to involve the cardiologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and the patient in the decision-making process.

In the perioperative setting for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery:

- Discontinue aspirin in patients without coronary heart disease, as bleeding risk outweighs benefit.

- Consider aspirin in patients at high risk for a major adverse cardiac event if benefits outweigh risk.

- Continue low-dose aspirin without interruption in patients with a coronary stent, irrespective of the type of stent.

- If a patient has had PCI with stent placement but is not currently on aspirin, talk with the patient and the treating cardiologist to find out why, and initiate aspirin if no contraindications exist.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al; POISE-2 Investigators. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(16):1494–1503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401105

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64(22):e77–e137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944

- Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy—I: prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. BMJ 1994; 308(6921):81–106. pmid:8298418

- Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244. doi:10.7326/M17-2341

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68(10):1082–1115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.513

- Albaladejo P, Marret E, Samama CM, et al. Non-cardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents: the RECO study. Heart 2011; 97(19):1566–1572. doi:10.1136/hrt.2011.224519

- Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators; Devereaux PJ, Chan MT, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2012; 307(21):2295–2304. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5502

- Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology 2014; 120(3):564–578. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113

- Gorka J, Polok K, Iwaniec T, et al. Altered preoperative coagulation and fibrinolysis are associated with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2017; 118(5):713–719. doi:10.1093/bja/aex081

- Rajagopalan S, Ford I, Bachoo P, et al. Platelet activation, myocardial ischemic events and postoperative non-response to aspirin in patients undergoing major vascular surgery. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5(10):2028–2035. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02694.x

- Priebe HJ. Triggers of perioperative myocardial ischaemia and infarction. Br J Anaesth 2004; 93(1):9–20. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh147

- Devereaux PJ, Goldman L, Cook DJ, Gilbert K, Leslie K, Guyatt GH. Perioperative cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a review of the magnitude of the problem, the pathophysiology of the events and methods to estimate and communicate risk. CMAJ 2005; 173(6):627–634. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050011

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009; 373(9678):1849–1860. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1

- George R, Menon VP, Edathadathil F, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery—incidence and predictors from a prospective observational cohort study at an Indian tertiary care centre. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97(19):e0402. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010402

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM; Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Characteristics of operating room procedures in US hospitals, 2011: statistical brief #170. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb170-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States-2011.jsp. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Hawn MT, Graham LA, Richman JS, Itani KM, Henderson WG, Maddox TM. Risk of major adverse cardiac events following noncardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents. JAMA 2013; 310(14):1462–1472. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278787

- Wijeysundera DN, Wijeysundera HC, Yun L, et al. Risk of elective major noncardiac surgery after coronary stent insertion: a population-based study. Circulation 2012; 126(11):1355–1362. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.102715

- Rossini R, Capodanno D, Lettieri C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and long-term prognosis of premature discontinuation of oral antiplatelet therapy after drug eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107(2):186–194. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.067

- Eisenberg MJ, Richard PR, Libersan D, Filion KB. Safety of short-term discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with drug-eluting stents. Circulation 2009; 119(12):1634–1642. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813667

- Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2005; 293(17):2126–2130. doi:10.1001/jama.293.17.2126

- Park DW, Park SW, Park KH, et al. Frequency of and risk factors for stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation during long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiol 2006; 98(3):352–356. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.039

In patients with cardiac stents, do not stop aspirin. If the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefit (eg, with intracranial procedures), an informed discussion involving the surgeon, cardiologist, and patient is critical to ascertain risks vs benefits.

In patients using aspirin for secondary prevention, the decision depends on the patient’s cardiac status and an assessment of risk vs benefit. Aspirin has no role in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who are at low risk of a major adverse cardiac event.1,2

Aspirin used for secondary prevention reduces rates of death from vascular causes,3 but data on the magnitude of benefit in the perioperative setting are still evolving. In patients with coronary stents, continuing aspirin is beneficial,4,5 whereas stopping it is associated with an increased risk of acute stent thrombosis, which causes significant morbidity and mortality.6

SURGERY AND THROMBOTIC RISK: WHY CONSIDER ASPIRIN?

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study7 prospectively screened 15,133 patients for myocardial injury with troponin T levels daily for the first 3 consecutive postoperative days; 1,263 (8%) of the patients had a troponin elevation of 0.03 ng/mL or higher. The 30-day mortality rate in this group was 9.8%, compared with 1.1% in patients with a troponin T level of less than 0.03 ng/mL (odds ratio 10.07; 95% confidence interval [CI] 7.84–12.94; P < .001).8 The higher the peak troponin T concentration, the higher the risk of death within 30 days:

- 0.01 ng/mL or less, risk 1.0%

- 0.02 ng/mL, risk 4.0%

- 0.03 to 0.29 ng/mL, risk 9.3%

- 0.30 ng/mL or greater, risk 16.9%.7

Myocardial injury is a common postoperative vascular complication.7 Myocardial infarction (MI) or injury perioperatively increases the risk of death: 1 in 10 patients dies within 30 days after surgery.8

Surgery creates substantial physiologic stress through factors such as fasting, anesthesia, intubation, surgical trauma, extubation, and pain. It promotes coagulation9 and inflammation with activation of platelets,10 potentially leading to thrombosis.11 Coronary thrombosis secondary to plaque rupture11,12 can result in perioperative MI. Perioperative hemodynamic variability, anemia, and hypoxia can lead to demand-supply mismatch and also cause cardiac ischemia.

Aspirin is an antiplatelet agent that irreversibly inhibits platelet aggregation by blocking the formation of cyclooxygenase. It has been used for several decades as an antithrombotic agent in primary and secondary prevention. However, its benefit in primary prevention is uncertain, and the magnitude of antithrombotic benefit must be balanced against the risk of bleeding.

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration13 performed a systematic review of 6 primary prevention trials involving 95,000 patients and found that aspirin therapy was associated with a 12% reduction in serious vascular events, which occurred in 0.51% of patients taking aspirin per year vs 0.57% of controls (P = .0001). However, aspirin also increased the risk of major bleeding, at a rate of 0.10% vs 0.07% per year (P < .0001), with 2 bleeding events for every avoided vascular event.13

WILL ASPIRIN PROTECT PATIENTS AT CARDIAC RISK?

The second Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation trial (POISE 2),1 in patients with atherosclerotic disease or at risk for it, found that giving aspirin in the perioperative period did not reduce the rate of death or nonfatal MI, but increased the risk of a major bleeding event.

The trial included 10,010 patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who were randomly assigned to receive aspirin or placebo. The aspirin arm included 2 groups: patients who were not on aspirin (initiation arm), and patients on aspirin at the time of randomization (continuation arm).

Death or nonfatal MI (the primary outcome) occurred in 7.0% of patients on aspirin vs 7.1% of patients receiving placebo (hazard ratio [HR] 0.99, 95% CI 0.86–1.15, P = .92). The risk of major bleeding was 4.6% in the aspirin group vs 3.8% in the placebo group (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01–1.49, P = .04).1

George et al,14 in a prospective observational study in a single tertiary care center, found that fewer patients with myocardial injury in noncardiac surgery died if they took aspirin or clopidogrel postoperatively. Conversely, lack of antithrombotic therapy was an independent predictor of death (P < .001). The mortality rate in patients with myocardial injury who were on antithrombotic therapy postoperatively was 6.7%, compared with 12.1% in those without postoperative antithrombotic therapy (estimated number needed to treat, 19).14

PATIENTS WITH CORONARY STENTS UNDERGOING NONCARDIAC SURGERY

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) accounts for 3.6% of all operating-room procedures in the United States,15 and 20% to 35% of patients who undergo PCI undergo noncardiac surgery within 2 years of stent implantation.16,17

Antiplatelet therapy is discontinued in about 20% of patients with previous PCI who undergo noncardiac surgery.18

Observational data have shown that stopping antiplatelet therapy in patients with previous PCI with stent placement who undergo noncardiac surgery is the single most important predictor of stent thrombosis and death.19–21 The risk increases if the interval between stent implantation and surgery is shorter, especially within 180 days.16,17 Patients who have stent thrombosis are at significantly higher risk of death.

Graham et al4 conducted a subgroup analysis of the POISE 2 trial comparing aspirin and placebo in 470 patients who had undergone PCI (427 had stent placement, and the rest had angioplasty or an unspecified type of PCI); 234 patients received aspirin and 236 placebo. The median time from stent implantation to surgery was 5.3 years.

Of the patients in the aspirin arm, 14 (6%) had the primary outcome of death or nonfatal MI compared with 27 patients (11.5%) in the placebo arm (absolute risk reduction 5.5%, 95% CI 0.4%–10.5%). The result, which differed from that in the primary trial,1 was due to reduction in MI in the PCI subgroup on aspirin. PCI patients who were on aspirin did not have increased bleeding risk. This subgroup analysis, albeit small and limited, suggests that continuing low-dose aspirin in patients with previous PCI, irrespective of the type of stent or the time from stent implantations, minimizes the risk of perioperative MI.

GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Routine perioperative use of aspirin increases the risk of bleeding without a reduction in ischemic events.1 Patients with prior PCI are at increased risk of acute stent thrombosis when antiplatelet medications are discontinued.20,21 Available data, although limited, support continuing low-dose aspirin without interruption in the perioperative period in PCI patients,4 as do the guidelines from the American College of Cardiology.5

We propose a management algorithm for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery on antiplatelet therapy that takes into consideration whether the surgery is urgent, elective, or time-sensitive (Figure 1). It is imperative to involve the cardiologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and the patient in the decision-making process.

In the perioperative setting for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery:

- Discontinue aspirin in patients without coronary heart disease, as bleeding risk outweighs benefit.

- Consider aspirin in patients at high risk for a major adverse cardiac event if benefits outweigh risk.

- Continue low-dose aspirin without interruption in patients with a coronary stent, irrespective of the type of stent.

- If a patient has had PCI with stent placement but is not currently on aspirin, talk with the patient and the treating cardiologist to find out why, and initiate aspirin if no contraindications exist.

In patients with cardiac stents, do not stop aspirin. If the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefit (eg, with intracranial procedures), an informed discussion involving the surgeon, cardiologist, and patient is critical to ascertain risks vs benefits.

In patients using aspirin for secondary prevention, the decision depends on the patient’s cardiac status and an assessment of risk vs benefit. Aspirin has no role in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who are at low risk of a major adverse cardiac event.1,2

Aspirin used for secondary prevention reduces rates of death from vascular causes,3 but data on the magnitude of benefit in the perioperative setting are still evolving. In patients with coronary stents, continuing aspirin is beneficial,4,5 whereas stopping it is associated with an increased risk of acute stent thrombosis, which causes significant morbidity and mortality.6

SURGERY AND THROMBOTIC RISK: WHY CONSIDER ASPIRIN?

The Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) study7 prospectively screened 15,133 patients for myocardial injury with troponin T levels daily for the first 3 consecutive postoperative days; 1,263 (8%) of the patients had a troponin elevation of 0.03 ng/mL or higher. The 30-day mortality rate in this group was 9.8%, compared with 1.1% in patients with a troponin T level of less than 0.03 ng/mL (odds ratio 10.07; 95% confidence interval [CI] 7.84–12.94; P < .001).8 The higher the peak troponin T concentration, the higher the risk of death within 30 days:

- 0.01 ng/mL or less, risk 1.0%

- 0.02 ng/mL, risk 4.0%

- 0.03 to 0.29 ng/mL, risk 9.3%

- 0.30 ng/mL or greater, risk 16.9%.7

Myocardial injury is a common postoperative vascular complication.7 Myocardial infarction (MI) or injury perioperatively increases the risk of death: 1 in 10 patients dies within 30 days after surgery.8

Surgery creates substantial physiologic stress through factors such as fasting, anesthesia, intubation, surgical trauma, extubation, and pain. It promotes coagulation9 and inflammation with activation of platelets,10 potentially leading to thrombosis.11 Coronary thrombosis secondary to plaque rupture11,12 can result in perioperative MI. Perioperative hemodynamic variability, anemia, and hypoxia can lead to demand-supply mismatch and also cause cardiac ischemia.

Aspirin is an antiplatelet agent that irreversibly inhibits platelet aggregation by blocking the formation of cyclooxygenase. It has been used for several decades as an antithrombotic agent in primary and secondary prevention. However, its benefit in primary prevention is uncertain, and the magnitude of antithrombotic benefit must be balanced against the risk of bleeding.

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration13 performed a systematic review of 6 primary prevention trials involving 95,000 patients and found that aspirin therapy was associated with a 12% reduction in serious vascular events, which occurred in 0.51% of patients taking aspirin per year vs 0.57% of controls (P = .0001). However, aspirin also increased the risk of major bleeding, at a rate of 0.10% vs 0.07% per year (P < .0001), with 2 bleeding events for every avoided vascular event.13

WILL ASPIRIN PROTECT PATIENTS AT CARDIAC RISK?

The second Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation trial (POISE 2),1 in patients with atherosclerotic disease or at risk for it, found that giving aspirin in the perioperative period did not reduce the rate of death or nonfatal MI, but increased the risk of a major bleeding event.

The trial included 10,010 patients undergoing noncardiac surgery who were randomly assigned to receive aspirin or placebo. The aspirin arm included 2 groups: patients who were not on aspirin (initiation arm), and patients on aspirin at the time of randomization (continuation arm).

Death or nonfatal MI (the primary outcome) occurred in 7.0% of patients on aspirin vs 7.1% of patients receiving placebo (hazard ratio [HR] 0.99, 95% CI 0.86–1.15, P = .92). The risk of major bleeding was 4.6% in the aspirin group vs 3.8% in the placebo group (HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.01–1.49, P = .04).1

George et al,14 in a prospective observational study in a single tertiary care center, found that fewer patients with myocardial injury in noncardiac surgery died if they took aspirin or clopidogrel postoperatively. Conversely, lack of antithrombotic therapy was an independent predictor of death (P < .001). The mortality rate in patients with myocardial injury who were on antithrombotic therapy postoperatively was 6.7%, compared with 12.1% in those without postoperative antithrombotic therapy (estimated number needed to treat, 19).14

PATIENTS WITH CORONARY STENTS UNDERGOING NONCARDIAC SURGERY

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) accounts for 3.6% of all operating-room procedures in the United States,15 and 20% to 35% of patients who undergo PCI undergo noncardiac surgery within 2 years of stent implantation.16,17

Antiplatelet therapy is discontinued in about 20% of patients with previous PCI who undergo noncardiac surgery.18

Observational data have shown that stopping antiplatelet therapy in patients with previous PCI with stent placement who undergo noncardiac surgery is the single most important predictor of stent thrombosis and death.19–21 The risk increases if the interval between stent implantation and surgery is shorter, especially within 180 days.16,17 Patients who have stent thrombosis are at significantly higher risk of death.

Graham et al4 conducted a subgroup analysis of the POISE 2 trial comparing aspirin and placebo in 470 patients who had undergone PCI (427 had stent placement, and the rest had angioplasty or an unspecified type of PCI); 234 patients received aspirin and 236 placebo. The median time from stent implantation to surgery was 5.3 years.

Of the patients in the aspirin arm, 14 (6%) had the primary outcome of death or nonfatal MI compared with 27 patients (11.5%) in the placebo arm (absolute risk reduction 5.5%, 95% CI 0.4%–10.5%). The result, which differed from that in the primary trial,1 was due to reduction in MI in the PCI subgroup on aspirin. PCI patients who were on aspirin did not have increased bleeding risk. This subgroup analysis, albeit small and limited, suggests that continuing low-dose aspirin in patients with previous PCI, irrespective of the type of stent or the time from stent implantations, minimizes the risk of perioperative MI.

GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Routine perioperative use of aspirin increases the risk of bleeding without a reduction in ischemic events.1 Patients with prior PCI are at increased risk of acute stent thrombosis when antiplatelet medications are discontinued.20,21 Available data, although limited, support continuing low-dose aspirin without interruption in the perioperative period in PCI patients,4 as do the guidelines from the American College of Cardiology.5

We propose a management algorithm for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery on antiplatelet therapy that takes into consideration whether the surgery is urgent, elective, or time-sensitive (Figure 1). It is imperative to involve the cardiologist, surgeon, anesthesiologist, and the patient in the decision-making process.

In the perioperative setting for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery:

- Discontinue aspirin in patients without coronary heart disease, as bleeding risk outweighs benefit.

- Consider aspirin in patients at high risk for a major adverse cardiac event if benefits outweigh risk.

- Continue low-dose aspirin without interruption in patients with a coronary stent, irrespective of the type of stent.

- If a patient has had PCI with stent placement but is not currently on aspirin, talk with the patient and the treating cardiologist to find out why, and initiate aspirin if no contraindications exist.

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al; POISE-2 Investigators. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(16):1494–1503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401105

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64(22):e77–e137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944

- Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy—I: prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. BMJ 1994; 308(6921):81–106. pmid:8298418

- Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244. doi:10.7326/M17-2341

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68(10):1082–1115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.513

- Albaladejo P, Marret E, Samama CM, et al. Non-cardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents: the RECO study. Heart 2011; 97(19):1566–1572. doi:10.1136/hrt.2011.224519

- Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators; Devereaux PJ, Chan MT, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2012; 307(21):2295–2304. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5502

- Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology 2014; 120(3):564–578. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113

- Gorka J, Polok K, Iwaniec T, et al. Altered preoperative coagulation and fibrinolysis are associated with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2017; 118(5):713–719. doi:10.1093/bja/aex081

- Rajagopalan S, Ford I, Bachoo P, et al. Platelet activation, myocardial ischemic events and postoperative non-response to aspirin in patients undergoing major vascular surgery. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5(10):2028–2035. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02694.x

- Priebe HJ. Triggers of perioperative myocardial ischaemia and infarction. Br J Anaesth 2004; 93(1):9–20. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh147

- Devereaux PJ, Goldman L, Cook DJ, Gilbert K, Leslie K, Guyatt GH. Perioperative cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a review of the magnitude of the problem, the pathophysiology of the events and methods to estimate and communicate risk. CMAJ 2005; 173(6):627–634. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050011

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009; 373(9678):1849–1860. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1

- George R, Menon VP, Edathadathil F, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery—incidence and predictors from a prospective observational cohort study at an Indian tertiary care centre. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97(19):e0402. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010402

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM; Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Characteristics of operating room procedures in US hospitals, 2011: statistical brief #170. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb170-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States-2011.jsp. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Hawn MT, Graham LA, Richman JS, Itani KM, Henderson WG, Maddox TM. Risk of major adverse cardiac events following noncardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents. JAMA 2013; 310(14):1462–1472. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278787

- Wijeysundera DN, Wijeysundera HC, Yun L, et al. Risk of elective major noncardiac surgery after coronary stent insertion: a population-based study. Circulation 2012; 126(11):1355–1362. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.102715

- Rossini R, Capodanno D, Lettieri C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and long-term prognosis of premature discontinuation of oral antiplatelet therapy after drug eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107(2):186–194. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.067

- Eisenberg MJ, Richard PR, Libersan D, Filion KB. Safety of short-term discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with drug-eluting stents. Circulation 2009; 119(12):1634–1642. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813667

- Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2005; 293(17):2126–2130. doi:10.1001/jama.293.17.2126

- Park DW, Park SW, Park KH, et al. Frequency of and risk factors for stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation during long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiol 2006; 98(3):352–356. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.039

- Devereaux PJ, Mrkobrada M, Sessler DI, et al; POISE-2 Investigators. Aspirin in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(16):1494–1503. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1401105

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64(22):e77–e137. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944

- Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy—I: prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. BMJ 1994; 308(6921):81–106. pmid:8298418

- Graham MM, Sessler DI, Parlow JL, et al. Aspirin in patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention undergoing noncardiac surgery. Ann Intern Med 2018; 168(4):237–244. doi:10.7326/M17-2341

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. 2016 ACC/AHA guideline focused update on duration of dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016; 68(10):1082–1115. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.513

- Albaladejo P, Marret E, Samama CM, et al. Non-cardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents: the RECO study. Heart 2011; 97(19):1566–1572. doi:10.1136/hrt.2011.224519

- Vascular Events in Noncardiac Surgery Patients Cohort Evaluation (VISION) Study Investigators; Devereaux PJ, Chan MT, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. JAMA 2012; 307(21):2295–2304. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.5502

- Botto F, Alonso-Coello P, Chan MT, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a large, international, prospective cohort study establishing diagnostic criteria, characteristics, predictors, and 30-day outcomes. Anesthesiology 2014; 120(3):564–578. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000113

- Gorka J, Polok K, Iwaniec T, et al. Altered preoperative coagulation and fibrinolysis are associated with myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth 2017; 118(5):713–719. doi:10.1093/bja/aex081

- Rajagopalan S, Ford I, Bachoo P, et al. Platelet activation, myocardial ischemic events and postoperative non-response to aspirin in patients undergoing major vascular surgery. J Thromb Haemost 2007; 5(10):2028–2035. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02694.x

- Priebe HJ. Triggers of perioperative myocardial ischaemia and infarction. Br J Anaesth 2004; 93(1):9–20. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh147

- Devereaux PJ, Goldman L, Cook DJ, Gilbert K, Leslie K, Guyatt GH. Perioperative cardiac events in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a review of the magnitude of the problem, the pathophysiology of the events and methods to estimate and communicate risk. CMAJ 2005; 173(6):627–634. doi:10.1503/cmaj.050011

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009; 373(9678):1849–1860. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1

- George R, Menon VP, Edathadathil F, et al. Myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery—incidence and predictors from a prospective observational cohort study at an Indian tertiary care centre. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97(19):e0402. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010402

- Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM; Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Characteristics of operating room procedures in US hospitals, 2011: statistical brief #170. https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb170-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States-2011.jsp. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Hawn MT, Graham LA, Richman JS, Itani KM, Henderson WG, Maddox TM. Risk of major adverse cardiac events following noncardiac surgery in patients with coronary stents. JAMA 2013; 310(14):1462–1472. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278787

- Wijeysundera DN, Wijeysundera HC, Yun L, et al. Risk of elective major noncardiac surgery after coronary stent insertion: a population-based study. Circulation 2012; 126(11):1355–1362. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.102715

- Rossini R, Capodanno D, Lettieri C, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and long-term prognosis of premature discontinuation of oral antiplatelet therapy after drug eluting stent implantation. Am J Cardiol 2011; 107(2):186–194. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.067

- Eisenberg MJ, Richard PR, Libersan D, Filion KB. Safety of short-term discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy in patients with drug-eluting stents. Circulation 2009; 119(12):1634–1642. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.813667

- Iakovou I, Schmidt T, Bonizzoni E, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcome of thrombosis after successful implantation of drug-eluting stents. JAMA 2005; 293(17):2126–2130. doi:10.1001/jama.293.17.2126

- Park DW, Park SW, Park KH, et al. Frequency of and risk factors for stent thrombosis after drug-eluting stent implantation during long-term follow-up. Am J Cardiol 2006; 98(3):352–356. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.039

Should all patients have a resting 12-lead ECG before elective noncardiac surgery?

A 55-year-old lawyer with hypertension well controlled on lisinopril and amlodipine is scheduled for elective hernia repair under general anesthesia. His surgeon has referred him for a preoperative evaluation. He has never smoked, runs 4 miles on days off from work, and enjoys long hiking trips. On examination, his body mass index is 26 kg/m2 and his blood pressure is 130/78 mm Hg; his cardiac examination and the rest of the clinical examination are unremarkable. He asks if he should have an electrocardiogram (ECG) as a part of his workup.

A preoperative ECG is not routinely recommended in all asymptomatic patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Consider obtaining an ECG in patients planning to undergo a high-risk surgical procedure, especially if they have one or more clinical risk factors for coronary artery disease, and in patients undergoing elevated-cardiac-risk surgery who are known to have coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, or cerebrovascular disease. However, a preoperative ECG is not routinely recommended for patients perceived to be at low cardiac risk who are planning to undergo low-risk surgery. In those patients it could delay surgery unnecessarily, cause further unnecessary testing, drive up costs, and increase patient anxiety.

Here we discuss the perioperative cardiac risk based on type of surgery and patient characteristics and summarize the current guidelines and recommendations on obtaining a preoperative 12-lead ECG in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

RISK DEPENDS ON TYPE OF SURGERY AND PATIENT FACTORS

Physicians, including primary care physicians, hospitalists, cardiologists, and anesthesiologists, are routinely asked to evaluate patients before surgical procedures. The purpose of the preoperative evaluation is to optimize existing medical conditions, to identify undiagnosed conditions that can increase risk of perioperative morbidity and death, and to suggest strategies to mitigate risk.1,2

Cardiac risk is multifactorial, and risk factors for postoperative adverse cardiac events include the type of surgery and patient factors.1,3

Cardiac risk based on type of surgery

Low-risk procedures are those in which the risk of a perioperative major adverse cardiac event is less than 1%.1,4 Examples:

- Ambulatory surgery

- Breast or plastic surgery

- Cataract surgery

- Endoscopic procedures.

Elevated-risk procedures are those in which the risk is 1% or higher. Examples:

- Intraperitoneal surgery

- Intrathoracic surgery

- Carotid endarterectomy

- Head and neck surgery

- Orthopedic surgery

- Prostate surgery

- Aortic surgery

- Major vascular surgery

- Peripheral arterial surgery.

Cardiac risk based on patient factors

The 2014 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) perioperative guidelines list a number of clinical risk factors for perioperative cardiac morbidity and death.1 These include coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, clinically suspected moderate or greater degrees of valvular heart disease, arrhythmias, conduction disorders, pulmonary vascular disease, and adult congenital heart disease.

Patients with these conditions and patients with unstable coronary syndromes warrant preoperative ECGs and sometimes even urgent interventions before any nonemergency surgery, provided such interventions would affect decision-making and perioperative care.1

The risk of perioperative cardiac morbidity and death can be calculated using either the Revised Cardiac Risk Index scoring system or the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program calculator.157 The former is fairly simple, validated, and accepted, while the latter requires use of online calculators (eg, www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/miorcardiacarrest, www.riskcalculator.facs.org).

The Revised Cardiac Risk Index has six clinical predictors of major perioperative cardiac events:

- History of cerebrovascular disease

- Prior or current compensated congestive heart failure

- History of coronary artery disease

- Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

- Renal insufficiency, defined as a serum creatinine level of 2 mg/dL or higher

- Patient undergoing suprainguinal vascular, intraperitoneal, or intrathoracic surgery.

A patient who has 0 or 1 of these predictors would have a low risk of a major adverse cardiac event, whereas a patient with 2 or more would have elevated risk. These risk factors must be taken into consideration to determine the need, if any, for a preoperative ECG.

What an ECG can tell us

Abnormalities such as left ventricular hypertrophy, ST-segment depression, and pathologic Q waves on a preoperative ECG in a patient undergoing an elevated-risk surgical procedure may predict adverse perioperative cardiac events.3,6

In a retrospective study of 23,036 patients, Noordzij et al7 found that in patients undergoing elevated-risk surgery, those with an abnormal preoperative ECG had a higher incidence of cardiovascular death than those with a normal ECG. However, a preoperative ECG was obtained only in patients with established coronary artery disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Hence, although an abnormal ECG in such patients undergoing elevated-risk surgery was predictive of adverse postoperative cardiac outcomes, we cannot say that the same would apply to patients without these characteristics undergoing elevated-risk surgery.

In a prospective observational study of patients with known coronary artery disease undergoing major noncardiac surgery, a preoperative ECG was found to contain prognostic information and was predictive of long-term outcome independent of clinical findings and perioperative ischemia.8

CURRENT GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Several guidelines address whether to order a preoperative ECG but are mostly based on low-level evidence and expert opinion.1,2,6,9

Current guidelines recommend obtaining a preoperative ECG in patients with known coronary, peripheral arterial, or cerebrovascular disease.1,6,9

Obesity and associated comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, systemic hypertension, and sleep apnea can predispose to increased perioperative complications. A preoperative 12-lead ECG is reasonable in morbidly obese patients (body mass index ≥ 40 kg/m2) and in obese patients (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) with at least one risk factor for coronary artery disease or poor exercise tolerance, or both.10

Liu et al11 looked at the predictive value of a preoperative 12-lead ECG in 513 elderly patients (age ≥ 70) undergoing noncardiac surgery and found that electrocardiographic abnormalities were not predictive of adverse cardiac outcomes. In this study, although electrocardiographic abnormalities were common (noted in 75% of the patients), they were nonspecific and less useful in predicting postoperative cardiac complications than was the presence of comorbidities.11 Age alone as a cutoff for obtaining a preoperative ECG is not predictive of postoperative outcomes and a preoperative ECG is not warranted in all elderly patients. This is also reflected in current ACC/AHA guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation1 and is a change from prior ACC/AHA guidelines when age was used as a criterion for preoperative ECGs.12

Current guidelines do not recommend getting a preoperative ECG in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-cardiac-risk surgery.1,4,9

Although the ideal time for ordering an ECG before a planned surgery is unknown, obtaining one within 90 days before the surgery is considered adequate in stable patients in whom an ECG is indicated.1

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

On the basis of current evidence, our patient does not need a preoperative ECG, as it is unlikely to alter his perioperative management and instead may delay his surgery unnecessarily if any nonspecific changes prompt further cardiac workup.

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

Although frequently ordered in clinical practice, preoperative electrocardiography has a limited role in predicting postoperative outcome and should be ordered only in the appropriate clinical setting.1 Moreover, there is little evidence that outcomes are better if we obtain an ECG before surgery. The clinician should consider patient factors and the type of surgery before ordering diagnostic tests, including electrocardiography.

In asymptomatic patients undergoing nonemergent surgery:

- It is reasonable to obtain a preoperative ECG in patients with known coronary artery disease, significant arrhythmia, peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic heart failure, or other significant structural heart disease undergoing elevated-cardiac-risk surgery.

- Do not order a preoperative ECG in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-risk surgery.

- Obtaining a preoperative ECG is reasonable in morbidly obese patients and in obese patients with one or more risk factors for coronary artery disease, or poor exercise tolerance, undergoing high-risk surgery.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; Jul 29. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. [Epub ahead of print]

- Feely MA, Collins CS, Daniels PR, Kebede EB, Jatoi A, Mauck KF. Preoperative testing before noncardiac surgery: guidelines and recommendations. Am Fam Physician 2013; 87:414–418.

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100:1043–1049.

- Task Force for Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative Cardiac Management in Non-cardiac Surgery; European Society of Cardiology (ESC); Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Boersma E, et al. Guidelines for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2769–2812.

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, Zhou L, Kmiecik TE, Ko CY, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217:833–842.

- Landesberg G, Einav S, Christopherson R, et al. Perioperative ischemia and cardiac complications in major vascular surgery: importance of the preoperative twelve-lead electrocardiogram. J Vasc Surg 1997; 26:570–578.

- Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. Prognostic value of routine preoperative electrocardiography in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:1103–1106.

- Jeger RV, Probst C, Arsenic R, et al. Long-term prognostic value of the preoperative 12-lead electrocardiogram before major noncardiac surgery in coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2006; 151:508–513.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, Pasternak LR, Arens JF, Caplan RA, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Poirier P, Alpert MA, Fleisher LA, et al. Cardiovascular evaluation and management of severely obese patients undergoing surgery: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009; 120:86–95.

- Liu LL, Dzankic S, Leung JM. Preoperative electrocardiogram abnormalities do not predict postoperative cardiac complications in geriatric surgical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:1186–1191.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:542–553.

A 55-year-old lawyer with hypertension well controlled on lisinopril and amlodipine is scheduled for elective hernia repair under general anesthesia. His surgeon has referred him for a preoperative evaluation. He has never smoked, runs 4 miles on days off from work, and enjoys long hiking trips. On examination, his body mass index is 26 kg/m2 and his blood pressure is 130/78 mm Hg; his cardiac examination and the rest of the clinical examination are unremarkable. He asks if he should have an electrocardiogram (ECG) as a part of his workup.

A preoperative ECG is not routinely recommended in all asymptomatic patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Consider obtaining an ECG in patients planning to undergo a high-risk surgical procedure, especially if they have one or more clinical risk factors for coronary artery disease, and in patients undergoing elevated-cardiac-risk surgery who are known to have coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, or cerebrovascular disease. However, a preoperative ECG is not routinely recommended for patients perceived to be at low cardiac risk who are planning to undergo low-risk surgery. In those patients it could delay surgery unnecessarily, cause further unnecessary testing, drive up costs, and increase patient anxiety.

Here we discuss the perioperative cardiac risk based on type of surgery and patient characteristics and summarize the current guidelines and recommendations on obtaining a preoperative 12-lead ECG in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

RISK DEPENDS ON TYPE OF SURGERY AND PATIENT FACTORS

Physicians, including primary care physicians, hospitalists, cardiologists, and anesthesiologists, are routinely asked to evaluate patients before surgical procedures. The purpose of the preoperative evaluation is to optimize existing medical conditions, to identify undiagnosed conditions that can increase risk of perioperative morbidity and death, and to suggest strategies to mitigate risk.1,2

Cardiac risk is multifactorial, and risk factors for postoperative adverse cardiac events include the type of surgery and patient factors.1,3

Cardiac risk based on type of surgery

Low-risk procedures are those in which the risk of a perioperative major adverse cardiac event is less than 1%.1,4 Examples:

- Ambulatory surgery

- Breast or plastic surgery

- Cataract surgery

- Endoscopic procedures.

Elevated-risk procedures are those in which the risk is 1% or higher. Examples:

- Intraperitoneal surgery

- Intrathoracic surgery

- Carotid endarterectomy

- Head and neck surgery

- Orthopedic surgery

- Prostate surgery

- Aortic surgery

- Major vascular surgery

- Peripheral arterial surgery.

Cardiac risk based on patient factors

The 2014 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) perioperative guidelines list a number of clinical risk factors for perioperative cardiac morbidity and death.1 These include coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, clinically suspected moderate or greater degrees of valvular heart disease, arrhythmias, conduction disorders, pulmonary vascular disease, and adult congenital heart disease.

Patients with these conditions and patients with unstable coronary syndromes warrant preoperative ECGs and sometimes even urgent interventions before any nonemergency surgery, provided such interventions would affect decision-making and perioperative care.1

The risk of perioperative cardiac morbidity and death can be calculated using either the Revised Cardiac Risk Index scoring system or the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program calculator.157 The former is fairly simple, validated, and accepted, while the latter requires use of online calculators (eg, www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/miorcardiacarrest, www.riskcalculator.facs.org).

The Revised Cardiac Risk Index has six clinical predictors of major perioperative cardiac events:

- History of cerebrovascular disease

- Prior or current compensated congestive heart failure

- History of coronary artery disease

- Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

- Renal insufficiency, defined as a serum creatinine level of 2 mg/dL or higher

- Patient undergoing suprainguinal vascular, intraperitoneal, or intrathoracic surgery.

A patient who has 0 or 1 of these predictors would have a low risk of a major adverse cardiac event, whereas a patient with 2 or more would have elevated risk. These risk factors must be taken into consideration to determine the need, if any, for a preoperative ECG.

What an ECG can tell us

Abnormalities such as left ventricular hypertrophy, ST-segment depression, and pathologic Q waves on a preoperative ECG in a patient undergoing an elevated-risk surgical procedure may predict adverse perioperative cardiac events.3,6

In a retrospective study of 23,036 patients, Noordzij et al7 found that in patients undergoing elevated-risk surgery, those with an abnormal preoperative ECG had a higher incidence of cardiovascular death than those with a normal ECG. However, a preoperative ECG was obtained only in patients with established coronary artery disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Hence, although an abnormal ECG in such patients undergoing elevated-risk surgery was predictive of adverse postoperative cardiac outcomes, we cannot say that the same would apply to patients without these characteristics undergoing elevated-risk surgery.

In a prospective observational study of patients with known coronary artery disease undergoing major noncardiac surgery, a preoperative ECG was found to contain prognostic information and was predictive of long-term outcome independent of clinical findings and perioperative ischemia.8

CURRENT GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Several guidelines address whether to order a preoperative ECG but are mostly based on low-level evidence and expert opinion.1,2,6,9

Current guidelines recommend obtaining a preoperative ECG in patients with known coronary, peripheral arterial, or cerebrovascular disease.1,6,9

Obesity and associated comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, systemic hypertension, and sleep apnea can predispose to increased perioperative complications. A preoperative 12-lead ECG is reasonable in morbidly obese patients (body mass index ≥ 40 kg/m2) and in obese patients (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) with at least one risk factor for coronary artery disease or poor exercise tolerance, or both.10

Liu et al11 looked at the predictive value of a preoperative 12-lead ECG in 513 elderly patients (age ≥ 70) undergoing noncardiac surgery and found that electrocardiographic abnormalities were not predictive of adverse cardiac outcomes. In this study, although electrocardiographic abnormalities were common (noted in 75% of the patients), they were nonspecific and less useful in predicting postoperative cardiac complications than was the presence of comorbidities.11 Age alone as a cutoff for obtaining a preoperative ECG is not predictive of postoperative outcomes and a preoperative ECG is not warranted in all elderly patients. This is also reflected in current ACC/AHA guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation1 and is a change from prior ACC/AHA guidelines when age was used as a criterion for preoperative ECGs.12

Current guidelines do not recommend getting a preoperative ECG in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-cardiac-risk surgery.1,4,9

Although the ideal time for ordering an ECG before a planned surgery is unknown, obtaining one within 90 days before the surgery is considered adequate in stable patients in whom an ECG is indicated.1

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

On the basis of current evidence, our patient does not need a preoperative ECG, as it is unlikely to alter his perioperative management and instead may delay his surgery unnecessarily if any nonspecific changes prompt further cardiac workup.

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

Although frequently ordered in clinical practice, preoperative electrocardiography has a limited role in predicting postoperative outcome and should be ordered only in the appropriate clinical setting.1 Moreover, there is little evidence that outcomes are better if we obtain an ECG before surgery. The clinician should consider patient factors and the type of surgery before ordering diagnostic tests, including electrocardiography.

In asymptomatic patients undergoing nonemergent surgery:

- It is reasonable to obtain a preoperative ECG in patients with known coronary artery disease, significant arrhythmia, peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic heart failure, or other significant structural heart disease undergoing elevated-cardiac-risk surgery.

- Do not order a preoperative ECG in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-risk surgery.

- Obtaining a preoperative ECG is reasonable in morbidly obese patients and in obese patients with one or more risk factors for coronary artery disease, or poor exercise tolerance, undergoing high-risk surgery.

A 55-year-old lawyer with hypertension well controlled on lisinopril and amlodipine is scheduled for elective hernia repair under general anesthesia. His surgeon has referred him for a preoperative evaluation. He has never smoked, runs 4 miles on days off from work, and enjoys long hiking trips. On examination, his body mass index is 26 kg/m2 and his blood pressure is 130/78 mm Hg; his cardiac examination and the rest of the clinical examination are unremarkable. He asks if he should have an electrocardiogram (ECG) as a part of his workup.

A preoperative ECG is not routinely recommended in all asymptomatic patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

Consider obtaining an ECG in patients planning to undergo a high-risk surgical procedure, especially if they have one or more clinical risk factors for coronary artery disease, and in patients undergoing elevated-cardiac-risk surgery who are known to have coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, or cerebrovascular disease. However, a preoperative ECG is not routinely recommended for patients perceived to be at low cardiac risk who are planning to undergo low-risk surgery. In those patients it could delay surgery unnecessarily, cause further unnecessary testing, drive up costs, and increase patient anxiety.

Here we discuss the perioperative cardiac risk based on type of surgery and patient characteristics and summarize the current guidelines and recommendations on obtaining a preoperative 12-lead ECG in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery.

RISK DEPENDS ON TYPE OF SURGERY AND PATIENT FACTORS

Physicians, including primary care physicians, hospitalists, cardiologists, and anesthesiologists, are routinely asked to evaluate patients before surgical procedures. The purpose of the preoperative evaluation is to optimize existing medical conditions, to identify undiagnosed conditions that can increase risk of perioperative morbidity and death, and to suggest strategies to mitigate risk.1,2

Cardiac risk is multifactorial, and risk factors for postoperative adverse cardiac events include the type of surgery and patient factors.1,3

Cardiac risk based on type of surgery

Low-risk procedures are those in which the risk of a perioperative major adverse cardiac event is less than 1%.1,4 Examples:

- Ambulatory surgery

- Breast or plastic surgery

- Cataract surgery

- Endoscopic procedures.

Elevated-risk procedures are those in which the risk is 1% or higher. Examples:

- Intraperitoneal surgery

- Intrathoracic surgery

- Carotid endarterectomy

- Head and neck surgery

- Orthopedic surgery

- Prostate surgery

- Aortic surgery

- Major vascular surgery

- Peripheral arterial surgery.

Cardiac risk based on patient factors

The 2014 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) perioperative guidelines list a number of clinical risk factors for perioperative cardiac morbidity and death.1 These include coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure, clinically suspected moderate or greater degrees of valvular heart disease, arrhythmias, conduction disorders, pulmonary vascular disease, and adult congenital heart disease.

Patients with these conditions and patients with unstable coronary syndromes warrant preoperative ECGs and sometimes even urgent interventions before any nonemergency surgery, provided such interventions would affect decision-making and perioperative care.1

The risk of perioperative cardiac morbidity and death can be calculated using either the Revised Cardiac Risk Index scoring system or the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program calculator.157 The former is fairly simple, validated, and accepted, while the latter requires use of online calculators (eg, www.surgicalriskcalculator.com/miorcardiacarrest, www.riskcalculator.facs.org).

The Revised Cardiac Risk Index has six clinical predictors of major perioperative cardiac events:

- History of cerebrovascular disease

- Prior or current compensated congestive heart failure

- History of coronary artery disease

- Insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus

- Renal insufficiency, defined as a serum creatinine level of 2 mg/dL or higher

- Patient undergoing suprainguinal vascular, intraperitoneal, or intrathoracic surgery.

A patient who has 0 or 1 of these predictors would have a low risk of a major adverse cardiac event, whereas a patient with 2 or more would have elevated risk. These risk factors must be taken into consideration to determine the need, if any, for a preoperative ECG.

What an ECG can tell us

Abnormalities such as left ventricular hypertrophy, ST-segment depression, and pathologic Q waves on a preoperative ECG in a patient undergoing an elevated-risk surgical procedure may predict adverse perioperative cardiac events.3,6

In a retrospective study of 23,036 patients, Noordzij et al7 found that in patients undergoing elevated-risk surgery, those with an abnormal preoperative ECG had a higher incidence of cardiovascular death than those with a normal ECG. However, a preoperative ECG was obtained only in patients with established coronary artery disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Hence, although an abnormal ECG in such patients undergoing elevated-risk surgery was predictive of adverse postoperative cardiac outcomes, we cannot say that the same would apply to patients without these characteristics undergoing elevated-risk surgery.

In a prospective observational study of patients with known coronary artery disease undergoing major noncardiac surgery, a preoperative ECG was found to contain prognostic information and was predictive of long-term outcome independent of clinical findings and perioperative ischemia.8

CURRENT GUIDELINES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Several guidelines address whether to order a preoperative ECG but are mostly based on low-level evidence and expert opinion.1,2,6,9

Current guidelines recommend obtaining a preoperative ECG in patients with known coronary, peripheral arterial, or cerebrovascular disease.1,6,9

Obesity and associated comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, systemic hypertension, and sleep apnea can predispose to increased perioperative complications. A preoperative 12-lead ECG is reasonable in morbidly obese patients (body mass index ≥ 40 kg/m2) and in obese patients (body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2) with at least one risk factor for coronary artery disease or poor exercise tolerance, or both.10

Liu et al11 looked at the predictive value of a preoperative 12-lead ECG in 513 elderly patients (age ≥ 70) undergoing noncardiac surgery and found that electrocardiographic abnormalities were not predictive of adverse cardiac outcomes. In this study, although electrocardiographic abnormalities were common (noted in 75% of the patients), they were nonspecific and less useful in predicting postoperative cardiac complications than was the presence of comorbidities.11 Age alone as a cutoff for obtaining a preoperative ECG is not predictive of postoperative outcomes and a preoperative ECG is not warranted in all elderly patients. This is also reflected in current ACC/AHA guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation1 and is a change from prior ACC/AHA guidelines when age was used as a criterion for preoperative ECGs.12

Current guidelines do not recommend getting a preoperative ECG in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-cardiac-risk surgery.1,4,9

Although the ideal time for ordering an ECG before a planned surgery is unknown, obtaining one within 90 days before the surgery is considered adequate in stable patients in whom an ECG is indicated.1

BACK TO OUR PATIENT

On the basis of current evidence, our patient does not need a preoperative ECG, as it is unlikely to alter his perioperative management and instead may delay his surgery unnecessarily if any nonspecific changes prompt further cardiac workup.

CLINICAL BOTTOM LINE

Although frequently ordered in clinical practice, preoperative electrocardiography has a limited role in predicting postoperative outcome and should be ordered only in the appropriate clinical setting.1 Moreover, there is little evidence that outcomes are better if we obtain an ECG before surgery. The clinician should consider patient factors and the type of surgery before ordering diagnostic tests, including electrocardiography.

In asymptomatic patients undergoing nonemergent surgery:

- It is reasonable to obtain a preoperative ECG in patients with known coronary artery disease, significant arrhythmia, peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic heart failure, or other significant structural heart disease undergoing elevated-cardiac-risk surgery.

- Do not order a preoperative ECG in asymptomatic patients undergoing low-risk surgery.

- Obtaining a preoperative ECG is reasonable in morbidly obese patients and in obese patients with one or more risk factors for coronary artery disease, or poor exercise tolerance, undergoing high-risk surgery.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; Jul 29. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. [Epub ahead of print]

- Feely MA, Collins CS, Daniels PR, Kebede EB, Jatoi A, Mauck KF. Preoperative testing before noncardiac surgery: guidelines and recommendations. Am Fam Physician 2013; 87:414–418.

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100:1043–1049.

- Task Force for Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative Cardiac Management in Non-cardiac Surgery; European Society of Cardiology (ESC); Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Boersma E, et al. Guidelines for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2769–2812.

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, Zhou L, Kmiecik TE, Ko CY, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217:833–842.

- Landesberg G, Einav S, Christopherson R, et al. Perioperative ischemia and cardiac complications in major vascular surgery: importance of the preoperative twelve-lead electrocardiogram. J Vasc Surg 1997; 26:570–578.

- Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. Prognostic value of routine preoperative electrocardiography in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:1103–1106.

- Jeger RV, Probst C, Arsenic R, et al. Long-term prognostic value of the preoperative 12-lead electrocardiogram before major noncardiac surgery in coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2006; 151:508–513.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, Pasternak LR, Arens JF, Caplan RA, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Poirier P, Alpert MA, Fleisher LA, et al. Cardiovascular evaluation and management of severely obese patients undergoing surgery: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009; 120:86–95.

- Liu LL, Dzankic S, Leung JM. Preoperative electrocardiogram abnormalities do not predict postoperative cardiac complications in geriatric surgical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:1186–1191.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:542–553.

- Fleisher LA, Fleischmann KE, Auerbach AD, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; Jul 29. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.944. [Epub ahead of print]

- Feely MA, Collins CS, Daniels PR, Kebede EB, Jatoi A, Mauck KF. Preoperative testing before noncardiac surgery: guidelines and recommendations. Am Fam Physician 2013; 87:414–418.

- Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation 1999; 100:1043–1049.

- Task Force for Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative Cardiac Management in Non-cardiac Surgery; European Society of Cardiology (ESC); Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Boersma E, et al. Guidelines for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2769–2812.

- Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, Zhou L, Kmiecik TE, Ko CY, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2013; 217:833–842.

- Landesberg G, Einav S, Christopherson R, et al. Perioperative ischemia and cardiac complications in major vascular surgery: importance of the preoperative twelve-lead electrocardiogram. J Vasc Surg 1997; 26:570–578.

- Noordzij PG, Boersma E, Bax JJ, et al. Prognostic value of routine preoperative electrocardiography in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:1103–1106.

- Jeger RV, Probst C, Arsenic R, et al. Long-term prognostic value of the preoperative 12-lead electrocardiogram before major noncardiac surgery in coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2006; 151:508–513.

- Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters; Apfelbaum JL, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, Pasternak LR, Arens JF, Caplan RA, et al. Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation. Anesthesiology 2012; 116:522–538.

- Poirier P, Alpert MA, Fleisher LA, et al. Cardiovascular evaluation and management of severely obese patients undergoing surgery: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2009; 120:86–95.

- Liu LL, Dzankic S, Leung JM. Preoperative electrocardiogram abnormalities do not predict postoperative cardiac complications in geriatric surgical patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50:1186–1191.

- Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery—executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:542–553.