User login

Should I evaluate my patient with atrial fibrillation for sleep apnea?

Yes. The prevalence of sleep apnea is exceedingly high in patients with atrial fibrillation—50% to 80% compared with 30% to 60% in respective control groups.1–3 Conversely, atrial fibrillation is more prevalent in those with sleep-disordered breathing than in those without (4.8% vs 0.9%).4

Sleep-disordered breathing comprises obstructive sleep apnea and central sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by repetitive upper-airway obstruction during sleep, is accompanied by intermittent hypoxia, rises in carbon dioxide, autonomic nervous system fluctuations, and intrathoracic pressure alterations.5 Central sleep apnea may be neurally mediated and, in the setting of cardiac disease, is characterized by alterations in chemosensitivity and chemoresponsiveness, leading to a state of high loop gain—ie, a hypersensitive ventilatory control system leading to ventilatory drive oscillations.6

Both obstructive and central sleep apnea have been associated with atrial fibrillation. Experimental data implicate obstructive sleep apnea as a trigger of atrial arrhythmogenesis,7,8 and epidemiologic studies support an association between central sleep apnea, Cheyne-Stokes respiration, and incident atrial fibrillation.9

HOW SLEEP APNEA COULD LEAD TO ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

In experiments in animals, intermittent upper-airway obstruction led to forced inspiration, substantial negative intrathoracic pressure, subsequent left atrial distention, and increased susceptibility to atrial fibrillation.10 The autonomic nervous system may be a mediator of apnea-induced atrial fibrillation, as apnea-induced atrial fibrillation is suppressed with autonomic blockade.10

Emerging data also support the hypothesis that intermittent hypoxia7 and resolution of hypercapnia,8 as observed in obstructive sleep apnea, exert atrial electrophysiologic changes that increase vulnerability to atrial arrhythmogenesis.

In a case-crossover study,11 the odds of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation occurring after a respiratory disturbance were 17.9 times higher than after normal breathing (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2–144.2), though the absolute rate of overall arrhythmia events (including both atrial fibrillation and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia) associated with respiratory disturbances was low (1 excess arrhythmia event per 40,000 respiratory disturbances).

EFFECT OF SLEEP APNEA ON ATRIAL FIBRILLATION MANAGEMENT

Sleep apnea also seems to affect the efficacy of a rhythm-control strategy for atrial fibrillation. For example, patients with obstructive sleep apnea have a higher risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation after cardioversion (82% vs 42% in controls)12 and up to a 25% greater risk of recurrence after catheter ablation compared with those without obstructive sleep apnea (risk ratio 1.25, 95% CI 1.08–1.45).13

Several observational studies showed a higher rate of atrial fibrillation after pulmonary vein isolation in obstructive sleep apnea patients who do not use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) than in those who do.14–17 CPAP therapy appears to exert beneficial effects on cardiac structural remodeling; cardiac magnetic resonance imaging shows that patients with sleep apnea who received less than 4 hours of CPAP per night had larger left atrial dimensions and increased left ventricular mass compared with those who received more than 4 hours of CPAP at night.17 However, a need remains for high-quality, large randomized controlled trials to eliminate potential unmeasured biases due to differences that may exist between CPAP users and non-users, such as general adherence to medical therapy and healthcare interventions.

An additional consideration is that the overall utility and value of obtaining a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea strictly as it pertains to atrial fibrillation management is affected by whether a rhythm- or rate-control strategy is pursued. In other words, if a patient is deemed to be in permanent atrial fibrillation and a rhythm-control strategy is therefore not pursued, the potential effect of untreated obstructive sleep apnea on atrial fibrillation recurrence could be less important. In this case, however, the other beneficial cardiovascular and systemic effects of diagnosing and treating underlying obstructive sleep apnea would remain.

POPULATION STUDIES

Epidemiologic and clinic-based studies have supported an association between sleep apnea (mostly central, but also obstructive) and atrial fibrillation.4,18

Community-based studies such as the Sleep Heart Health Study4 and the Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men Study (MrOS Sleep),18 involving thousands of participants, have found the strongest cross-sectional associations of both obstructive and central sleep apnea with nocturnal atrial fibrillation. The findings included a 2 to 5 times higher odds of nocturnal atrial fibrillation, particularly in those with a moderate to severe degree of sleep-disordered breathing—even after adjusting for confounding influences (eg, obesity) and self-reported cardiac disease such as heart failure.

In MrOS Sleep, in an older male cohort, both obstructive and central sleep apnea were associated with nocturnal atrial fibrillation, though central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respirations had a stronger magnitude of association.18

Further insights can be drawn specifically from patients with heart failure. Sin et al,19 in a 1999 study, found that in 450 patients with systolic heart failure (85% men), the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing was 25% to 33% (depending on the apnea-hypopnea index cutoff used) for central sleep apnea, and similarly 27% to 38% for obstructive sleep apnea. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in this group was 10% in women and 15% in men. Atrial fibrillation was reported as a significant risk factor for central sleep apnea, but not for obstructive sleep apnea (for which only male sex and increasing body mass index were significant risk factors). Directionality was not clearly reported in this retrospective study in terms of timing of sleep studies and other assessments: ie, the report did not clearly state which came first, the atrial fibrillation or the sleep apnea. Therefore, the possibility that central sleep apnea is a predictor of atrial fibrillation cannot be excluded.

Yumino et al,20 in a study published in 2009, evaluated 218 patients with heart failure (with a left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤ 45%) and reported a prevalence of moderate to severe sleep apnea of 21% for central sleep apnea and 26% for obstructive sleep apnea. In multivariate analysis, atrial fibrillation was independently associated with central sleep apnea but not obstructive sleep apnea.

In recent cohort studies, central sleep apnea was associated with 2 to 3 times higher odds of developing atrial fibrillation, while obstructive sleep apnea was not a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation.9,21

Although most available studies associate sleep apnea with atrial fibrillation, findings of a case-control study22 did not support a difference in the prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome (defined as apnea index ≥ 5 and apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 15, and the presence of sleep symptoms) in patients with lone atrial fibrillation (no evident cardiovascular disease) compared with controls matched for age, sex, and cardiovascular morbidity.

But observational studies are limited by the potential for residual unmeasured confounding factors and lack of objective cardiac structural data, such as left ventricular ejection fraction and atrial enlargement. Moreover, there can be significant differences in sleep apnea definitions among studies, thus limiting the ability to reach a definitive conclusion about the relationship between sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation.

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS

The 2014 joint guidelines of the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society for the management of atrial fibrillation state that a sleep study may be useful if sleep apnea is suspected.23 The 2019 focused update of the 2014 guidelines24 state that for overweight and obese patients with atrial fibrillation, weight loss combined with risk-factor modification is recommended (class I recommendation, level of evidence B-R, ie, data derived from 1 or more randomized trials or meta-analysis of such studies). Risk-factor modification in this case includes assessment and treatment of underlying sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, glucose intolerance, and alcohol and tobacco use.

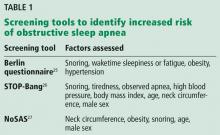

Laboratory polysomnography has long been considered the gold standard for sleep apnea diagnosis. In one study,13 obstructive sleep apnea was a greater predictor of atrial fibrillation when diagnosed by polysomnography (risk ratio 1.40, 95% CI 1.16–1.68) compared with identification by screening using the Berlin questionnaire (risk ratio 1.07, 95% CI 0.91–1.27). However, a laboratory sleep study is associated with increased patient burden and limited availability.

Home sleep apnea testing is being increasingly used in the diagnostic evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea and may be a less costly, more available alternative. However, since a home sleep apnea test is less sensitive than polysomnography in detecting obstructive sleep apnea, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines28 state that if a single home sleep apnea test is negative or inconclusive, polysomnography should be done if there is clinical suspicion of sleep apnea. Moreover, current guidelines from this group recommend that patients with significant cardiorespiratory disease should be tested with polysomnography rather than home sleep apnea testing.22

Further study is needed to determine the optimal screening method for sleep apnea in patients with atrial fibrillation and to clarify the role of home sleep apnea testing. While keeping in mind the limitations of a screening questionnaire in this population, as a general approach it is reasonable to use a screening questionnaire for sleep apnea. And if the screen is positive, further evaluation with a sleep study is merited, whether by laboratory polysomnography, a home sleep apnea test, or referral to a sleep specialist.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE MAY BE IDEAL

Overall, given the high prevalence of sleep apnea in patients with atrial fibrillation, the deleterious effects of sleep apnea in general, the influence of sleep apnea on atrial fibrillation, and the cardiovascular and other beneficial effects of adequate treatment of sleep apnea, patients with atrial fibrillation should be assessed for sleep apnea.

While the optimal strategy in evaluating for sleep apnea in these patients needs to be further defined, a multidisciplinary approach to care involving a primary care provider, cardiologist, and sleep specialist may be ideal.

- Braga B, Poyares D, Cintra F, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and chronic atrial fibrillation. Sleep Med 2009; 10(2):212–216. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.12.007

- Gami AS, Pressman G, Caples SM, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 2004; 110(4):364–367. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000136587.68725.8E

- Stevenson IH, Teichtahl H, Cunnington D, Ciavarella S, Gordon I, Kalman JM. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation patients with normal left ventricular function. Eur Heart J 2008; 29(13):1662–1669. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn214

- Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, et al. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173(8):910–916. doi:10.1164/rccm.200509-1442OC

- Cooper VL, Bowker CM, Pearson SB, Elliott MW, Hainsworth R. Effects of simulated obstructive sleep apnoea on the human carotid baroreceptor-vascular resistance reflex. J Physiol 2004; 557(pt 3):1055–1065. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062513

- Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Merchia P, Malhotra A. Central sleep apnea: pathophysiology and treatment. Chest 2007; 131(2):595–607. doi:10.1378/chest.06.2287

- Lévy P, Pépin JL, Arnaud C, et al. Intermittent hypoxia and sleep-disordered breathing: current concepts and perspectives. Eur Respir J 2008; 32(4):1082–1095. doi:10.1183/09031936.00013308

- Stevenson IH, Roberts-Thomson KC, Kistler PM, et al. Atrial electrophysiology is altered by acute hypercapnia but not hypoxemia: implications for promotion of atrial fibrillation in pulmonary disease and sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7(9):1263–1270. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.03.020

- Tung P, Levitzky YS, Wang R, et al. Obstructive and central sleep apnea and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in a community cohort of men and women. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6(7). doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004500

- Iwasaki YK, Shi Y, Benito B, et al. Determinants of atrial fibrillation in an animal model of obesity and acute obstructive sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9(9):1409–1416.e1. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.024

- Monahan K, Storfer-Isser A, Mehra R, et al. Triggering of nocturnal arrhythmias by sleep-disordered breathing events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54(19):1797–1804. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.038

- Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2003; 107(20):2589–2594. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000068337.25994.21

- Ng CY, Liu T, Shehata M, Stevens S, Chugh SS, Wang X. Meta-analysis of obstructive sleep apnea as predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108(1):47–51. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.343

- Naruse Y, Tada H, Satoh M, et al. Concomitant obstructive sleep apnea increases the recurrence of atrial fibrillation following radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: clinical impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Heart Rhythm 2013; 10(3):331–337. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.11.015

- Fein AS, Shvilkin A, Shah D, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62(4):300–305. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.052

- Patel D, Mohanty P, Di Biase L, et al. Safety and efficacy of pulmonary vein antral isolation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: the impact of continuous positive airway pressure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3(5):445–451. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.109.858381

- Neilan TG, Farhad H, Dodson JA, et al. Effect of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac structure and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2(6):e000421. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000421

- Mehra R, Stone KL, Varosy PD, et al. Nocturnal arrhythmias across a spectrum of obstructive and central sleep-disordered breathing in older men: outcomes of sleep disorders in older men (MrOS sleep) study. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(12):1147–1155. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.138

- Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160(4):1101–1106. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9903020

- Yumino D, Wang H, Floras JS, et al. Prevalence and physiological predictors of sleep apnea in patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail 2009; 15(4):279–285. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.11.015

- May AM, Blackwell T, Stone PH, et al; MrOS Sleep (Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men) Study Group. Central sleep-disordered breathing predicts incident atrial fibrillation in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193(7):783–791. doi:10.1164/rccm.201508-1523OC

- Porthan KM, Melin JH, Kupila JT, Venho KK, Partinen MM. Prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome in lone atrial fibrillation: a case-control study. Chest 2004; 125(3):879–885. doi:10.1378/chest.125.3.879

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014; 130(23):e199–e267. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041

- Writing Group Members; January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16(8):e66–e93. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.01.024

- Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131(7):485–491. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002

- Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-bang questionnaire a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2016; 149(3):631–638. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0903

- Marti-Soler H, Hirotsu C, Marques-Vidal P, et al. The NoSAS score for screening of sleep-disordered breathing: a derivation and validation study. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4(9):742–748. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30075-3

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13(3):479–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

Yes. The prevalence of sleep apnea is exceedingly high in patients with atrial fibrillation—50% to 80% compared with 30% to 60% in respective control groups.1–3 Conversely, atrial fibrillation is more prevalent in those with sleep-disordered breathing than in those without (4.8% vs 0.9%).4

Sleep-disordered breathing comprises obstructive sleep apnea and central sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by repetitive upper-airway obstruction during sleep, is accompanied by intermittent hypoxia, rises in carbon dioxide, autonomic nervous system fluctuations, and intrathoracic pressure alterations.5 Central sleep apnea may be neurally mediated and, in the setting of cardiac disease, is characterized by alterations in chemosensitivity and chemoresponsiveness, leading to a state of high loop gain—ie, a hypersensitive ventilatory control system leading to ventilatory drive oscillations.6

Both obstructive and central sleep apnea have been associated with atrial fibrillation. Experimental data implicate obstructive sleep apnea as a trigger of atrial arrhythmogenesis,7,8 and epidemiologic studies support an association between central sleep apnea, Cheyne-Stokes respiration, and incident atrial fibrillation.9

HOW SLEEP APNEA COULD LEAD TO ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

In experiments in animals, intermittent upper-airway obstruction led to forced inspiration, substantial negative intrathoracic pressure, subsequent left atrial distention, and increased susceptibility to atrial fibrillation.10 The autonomic nervous system may be a mediator of apnea-induced atrial fibrillation, as apnea-induced atrial fibrillation is suppressed with autonomic blockade.10

Emerging data also support the hypothesis that intermittent hypoxia7 and resolution of hypercapnia,8 as observed in obstructive sleep apnea, exert atrial electrophysiologic changes that increase vulnerability to atrial arrhythmogenesis.

In a case-crossover study,11 the odds of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation occurring after a respiratory disturbance were 17.9 times higher than after normal breathing (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2–144.2), though the absolute rate of overall arrhythmia events (including both atrial fibrillation and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia) associated with respiratory disturbances was low (1 excess arrhythmia event per 40,000 respiratory disturbances).

EFFECT OF SLEEP APNEA ON ATRIAL FIBRILLATION MANAGEMENT

Sleep apnea also seems to affect the efficacy of a rhythm-control strategy for atrial fibrillation. For example, patients with obstructive sleep apnea have a higher risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation after cardioversion (82% vs 42% in controls)12 and up to a 25% greater risk of recurrence after catheter ablation compared with those without obstructive sleep apnea (risk ratio 1.25, 95% CI 1.08–1.45).13

Several observational studies showed a higher rate of atrial fibrillation after pulmonary vein isolation in obstructive sleep apnea patients who do not use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) than in those who do.14–17 CPAP therapy appears to exert beneficial effects on cardiac structural remodeling; cardiac magnetic resonance imaging shows that patients with sleep apnea who received less than 4 hours of CPAP per night had larger left atrial dimensions and increased left ventricular mass compared with those who received more than 4 hours of CPAP at night.17 However, a need remains for high-quality, large randomized controlled trials to eliminate potential unmeasured biases due to differences that may exist between CPAP users and non-users, such as general adherence to medical therapy and healthcare interventions.

An additional consideration is that the overall utility and value of obtaining a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea strictly as it pertains to atrial fibrillation management is affected by whether a rhythm- or rate-control strategy is pursued. In other words, if a patient is deemed to be in permanent atrial fibrillation and a rhythm-control strategy is therefore not pursued, the potential effect of untreated obstructive sleep apnea on atrial fibrillation recurrence could be less important. In this case, however, the other beneficial cardiovascular and systemic effects of diagnosing and treating underlying obstructive sleep apnea would remain.

POPULATION STUDIES

Epidemiologic and clinic-based studies have supported an association between sleep apnea (mostly central, but also obstructive) and atrial fibrillation.4,18

Community-based studies such as the Sleep Heart Health Study4 and the Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men Study (MrOS Sleep),18 involving thousands of participants, have found the strongest cross-sectional associations of both obstructive and central sleep apnea with nocturnal atrial fibrillation. The findings included a 2 to 5 times higher odds of nocturnal atrial fibrillation, particularly in those with a moderate to severe degree of sleep-disordered breathing—even after adjusting for confounding influences (eg, obesity) and self-reported cardiac disease such as heart failure.

In MrOS Sleep, in an older male cohort, both obstructive and central sleep apnea were associated with nocturnal atrial fibrillation, though central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respirations had a stronger magnitude of association.18

Further insights can be drawn specifically from patients with heart failure. Sin et al,19 in a 1999 study, found that in 450 patients with systolic heart failure (85% men), the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing was 25% to 33% (depending on the apnea-hypopnea index cutoff used) for central sleep apnea, and similarly 27% to 38% for obstructive sleep apnea. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in this group was 10% in women and 15% in men. Atrial fibrillation was reported as a significant risk factor for central sleep apnea, but not for obstructive sleep apnea (for which only male sex and increasing body mass index were significant risk factors). Directionality was not clearly reported in this retrospective study in terms of timing of sleep studies and other assessments: ie, the report did not clearly state which came first, the atrial fibrillation or the sleep apnea. Therefore, the possibility that central sleep apnea is a predictor of atrial fibrillation cannot be excluded.

Yumino et al,20 in a study published in 2009, evaluated 218 patients with heart failure (with a left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤ 45%) and reported a prevalence of moderate to severe sleep apnea of 21% for central sleep apnea and 26% for obstructive sleep apnea. In multivariate analysis, atrial fibrillation was independently associated with central sleep apnea but not obstructive sleep apnea.

In recent cohort studies, central sleep apnea was associated with 2 to 3 times higher odds of developing atrial fibrillation, while obstructive sleep apnea was not a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation.9,21

Although most available studies associate sleep apnea with atrial fibrillation, findings of a case-control study22 did not support a difference in the prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome (defined as apnea index ≥ 5 and apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 15, and the presence of sleep symptoms) in patients with lone atrial fibrillation (no evident cardiovascular disease) compared with controls matched for age, sex, and cardiovascular morbidity.

But observational studies are limited by the potential for residual unmeasured confounding factors and lack of objective cardiac structural data, such as left ventricular ejection fraction and atrial enlargement. Moreover, there can be significant differences in sleep apnea definitions among studies, thus limiting the ability to reach a definitive conclusion about the relationship between sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation.

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS

The 2014 joint guidelines of the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society for the management of atrial fibrillation state that a sleep study may be useful if sleep apnea is suspected.23 The 2019 focused update of the 2014 guidelines24 state that for overweight and obese patients with atrial fibrillation, weight loss combined with risk-factor modification is recommended (class I recommendation, level of evidence B-R, ie, data derived from 1 or more randomized trials or meta-analysis of such studies). Risk-factor modification in this case includes assessment and treatment of underlying sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, glucose intolerance, and alcohol and tobacco use.

Laboratory polysomnography has long been considered the gold standard for sleep apnea diagnosis. In one study,13 obstructive sleep apnea was a greater predictor of atrial fibrillation when diagnosed by polysomnography (risk ratio 1.40, 95% CI 1.16–1.68) compared with identification by screening using the Berlin questionnaire (risk ratio 1.07, 95% CI 0.91–1.27). However, a laboratory sleep study is associated with increased patient burden and limited availability.

Home sleep apnea testing is being increasingly used in the diagnostic evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea and may be a less costly, more available alternative. However, since a home sleep apnea test is less sensitive than polysomnography in detecting obstructive sleep apnea, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines28 state that if a single home sleep apnea test is negative or inconclusive, polysomnography should be done if there is clinical suspicion of sleep apnea. Moreover, current guidelines from this group recommend that patients with significant cardiorespiratory disease should be tested with polysomnography rather than home sleep apnea testing.22

Further study is needed to determine the optimal screening method for sleep apnea in patients with atrial fibrillation and to clarify the role of home sleep apnea testing. While keeping in mind the limitations of a screening questionnaire in this population, as a general approach it is reasonable to use a screening questionnaire for sleep apnea. And if the screen is positive, further evaluation with a sleep study is merited, whether by laboratory polysomnography, a home sleep apnea test, or referral to a sleep specialist.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE MAY BE IDEAL

Overall, given the high prevalence of sleep apnea in patients with atrial fibrillation, the deleterious effects of sleep apnea in general, the influence of sleep apnea on atrial fibrillation, and the cardiovascular and other beneficial effects of adequate treatment of sleep apnea, patients with atrial fibrillation should be assessed for sleep apnea.

While the optimal strategy in evaluating for sleep apnea in these patients needs to be further defined, a multidisciplinary approach to care involving a primary care provider, cardiologist, and sleep specialist may be ideal.

Yes. The prevalence of sleep apnea is exceedingly high in patients with atrial fibrillation—50% to 80% compared with 30% to 60% in respective control groups.1–3 Conversely, atrial fibrillation is more prevalent in those with sleep-disordered breathing than in those without (4.8% vs 0.9%).4

Sleep-disordered breathing comprises obstructive sleep apnea and central sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea, characterized by repetitive upper-airway obstruction during sleep, is accompanied by intermittent hypoxia, rises in carbon dioxide, autonomic nervous system fluctuations, and intrathoracic pressure alterations.5 Central sleep apnea may be neurally mediated and, in the setting of cardiac disease, is characterized by alterations in chemosensitivity and chemoresponsiveness, leading to a state of high loop gain—ie, a hypersensitive ventilatory control system leading to ventilatory drive oscillations.6

Both obstructive and central sleep apnea have been associated with atrial fibrillation. Experimental data implicate obstructive sleep apnea as a trigger of atrial arrhythmogenesis,7,8 and epidemiologic studies support an association between central sleep apnea, Cheyne-Stokes respiration, and incident atrial fibrillation.9

HOW SLEEP APNEA COULD LEAD TO ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

In experiments in animals, intermittent upper-airway obstruction led to forced inspiration, substantial negative intrathoracic pressure, subsequent left atrial distention, and increased susceptibility to atrial fibrillation.10 The autonomic nervous system may be a mediator of apnea-induced atrial fibrillation, as apnea-induced atrial fibrillation is suppressed with autonomic blockade.10

Emerging data also support the hypothesis that intermittent hypoxia7 and resolution of hypercapnia,8 as observed in obstructive sleep apnea, exert atrial electrophysiologic changes that increase vulnerability to atrial arrhythmogenesis.

In a case-crossover study,11 the odds of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation occurring after a respiratory disturbance were 17.9 times higher than after normal breathing (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2–144.2), though the absolute rate of overall arrhythmia events (including both atrial fibrillation and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia) associated with respiratory disturbances was low (1 excess arrhythmia event per 40,000 respiratory disturbances).

EFFECT OF SLEEP APNEA ON ATRIAL FIBRILLATION MANAGEMENT

Sleep apnea also seems to affect the efficacy of a rhythm-control strategy for atrial fibrillation. For example, patients with obstructive sleep apnea have a higher risk of recurrent atrial fibrillation after cardioversion (82% vs 42% in controls)12 and up to a 25% greater risk of recurrence after catheter ablation compared with those without obstructive sleep apnea (risk ratio 1.25, 95% CI 1.08–1.45).13

Several observational studies showed a higher rate of atrial fibrillation after pulmonary vein isolation in obstructive sleep apnea patients who do not use continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) than in those who do.14–17 CPAP therapy appears to exert beneficial effects on cardiac structural remodeling; cardiac magnetic resonance imaging shows that patients with sleep apnea who received less than 4 hours of CPAP per night had larger left atrial dimensions and increased left ventricular mass compared with those who received more than 4 hours of CPAP at night.17 However, a need remains for high-quality, large randomized controlled trials to eliminate potential unmeasured biases due to differences that may exist between CPAP users and non-users, such as general adherence to medical therapy and healthcare interventions.

An additional consideration is that the overall utility and value of obtaining a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea strictly as it pertains to atrial fibrillation management is affected by whether a rhythm- or rate-control strategy is pursued. In other words, if a patient is deemed to be in permanent atrial fibrillation and a rhythm-control strategy is therefore not pursued, the potential effect of untreated obstructive sleep apnea on atrial fibrillation recurrence could be less important. In this case, however, the other beneficial cardiovascular and systemic effects of diagnosing and treating underlying obstructive sleep apnea would remain.

POPULATION STUDIES

Epidemiologic and clinic-based studies have supported an association between sleep apnea (mostly central, but also obstructive) and atrial fibrillation.4,18

Community-based studies such as the Sleep Heart Health Study4 and the Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men Study (MrOS Sleep),18 involving thousands of participants, have found the strongest cross-sectional associations of both obstructive and central sleep apnea with nocturnal atrial fibrillation. The findings included a 2 to 5 times higher odds of nocturnal atrial fibrillation, particularly in those with a moderate to severe degree of sleep-disordered breathing—even after adjusting for confounding influences (eg, obesity) and self-reported cardiac disease such as heart failure.

In MrOS Sleep, in an older male cohort, both obstructive and central sleep apnea were associated with nocturnal atrial fibrillation, though central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respirations had a stronger magnitude of association.18

Further insights can be drawn specifically from patients with heart failure. Sin et al,19 in a 1999 study, found that in 450 patients with systolic heart failure (85% men), the prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing was 25% to 33% (depending on the apnea-hypopnea index cutoff used) for central sleep apnea, and similarly 27% to 38% for obstructive sleep apnea. The prevalence of atrial fibrillation in this group was 10% in women and 15% in men. Atrial fibrillation was reported as a significant risk factor for central sleep apnea, but not for obstructive sleep apnea (for which only male sex and increasing body mass index were significant risk factors). Directionality was not clearly reported in this retrospective study in terms of timing of sleep studies and other assessments: ie, the report did not clearly state which came first, the atrial fibrillation or the sleep apnea. Therefore, the possibility that central sleep apnea is a predictor of atrial fibrillation cannot be excluded.

Yumino et al,20 in a study published in 2009, evaluated 218 patients with heart failure (with a left ventricular ejection fraction of ≤ 45%) and reported a prevalence of moderate to severe sleep apnea of 21% for central sleep apnea and 26% for obstructive sleep apnea. In multivariate analysis, atrial fibrillation was independently associated with central sleep apnea but not obstructive sleep apnea.

In recent cohort studies, central sleep apnea was associated with 2 to 3 times higher odds of developing atrial fibrillation, while obstructive sleep apnea was not a predictor of incident atrial fibrillation.9,21

Although most available studies associate sleep apnea with atrial fibrillation, findings of a case-control study22 did not support a difference in the prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome (defined as apnea index ≥ 5 and apnea-hypopnea index ≥ 15, and the presence of sleep symptoms) in patients with lone atrial fibrillation (no evident cardiovascular disease) compared with controls matched for age, sex, and cardiovascular morbidity.

But observational studies are limited by the potential for residual unmeasured confounding factors and lack of objective cardiac structural data, such as left ventricular ejection fraction and atrial enlargement. Moreover, there can be significant differences in sleep apnea definitions among studies, thus limiting the ability to reach a definitive conclusion about the relationship between sleep apnea and atrial fibrillation.

SCREENING AND DIAGNOSIS

The 2014 joint guidelines of the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society for the management of atrial fibrillation state that a sleep study may be useful if sleep apnea is suspected.23 The 2019 focused update of the 2014 guidelines24 state that for overweight and obese patients with atrial fibrillation, weight loss combined with risk-factor modification is recommended (class I recommendation, level of evidence B-R, ie, data derived from 1 or more randomized trials or meta-analysis of such studies). Risk-factor modification in this case includes assessment and treatment of underlying sleep apnea, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, glucose intolerance, and alcohol and tobacco use.

Laboratory polysomnography has long been considered the gold standard for sleep apnea diagnosis. In one study,13 obstructive sleep apnea was a greater predictor of atrial fibrillation when diagnosed by polysomnography (risk ratio 1.40, 95% CI 1.16–1.68) compared with identification by screening using the Berlin questionnaire (risk ratio 1.07, 95% CI 0.91–1.27). However, a laboratory sleep study is associated with increased patient burden and limited availability.

Home sleep apnea testing is being increasingly used in the diagnostic evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea and may be a less costly, more available alternative. However, since a home sleep apnea test is less sensitive than polysomnography in detecting obstructive sleep apnea, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine guidelines28 state that if a single home sleep apnea test is negative or inconclusive, polysomnography should be done if there is clinical suspicion of sleep apnea. Moreover, current guidelines from this group recommend that patients with significant cardiorespiratory disease should be tested with polysomnography rather than home sleep apnea testing.22

Further study is needed to determine the optimal screening method for sleep apnea in patients with atrial fibrillation and to clarify the role of home sleep apnea testing. While keeping in mind the limitations of a screening questionnaire in this population, as a general approach it is reasonable to use a screening questionnaire for sleep apnea. And if the screen is positive, further evaluation with a sleep study is merited, whether by laboratory polysomnography, a home sleep apnea test, or referral to a sleep specialist.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE MAY BE IDEAL

Overall, given the high prevalence of sleep apnea in patients with atrial fibrillation, the deleterious effects of sleep apnea in general, the influence of sleep apnea on atrial fibrillation, and the cardiovascular and other beneficial effects of adequate treatment of sleep apnea, patients with atrial fibrillation should be assessed for sleep apnea.

While the optimal strategy in evaluating for sleep apnea in these patients needs to be further defined, a multidisciplinary approach to care involving a primary care provider, cardiologist, and sleep specialist may be ideal.

- Braga B, Poyares D, Cintra F, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and chronic atrial fibrillation. Sleep Med 2009; 10(2):212–216. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.12.007

- Gami AS, Pressman G, Caples SM, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 2004; 110(4):364–367. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000136587.68725.8E

- Stevenson IH, Teichtahl H, Cunnington D, Ciavarella S, Gordon I, Kalman JM. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation patients with normal left ventricular function. Eur Heart J 2008; 29(13):1662–1669. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn214

- Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, et al. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173(8):910–916. doi:10.1164/rccm.200509-1442OC

- Cooper VL, Bowker CM, Pearson SB, Elliott MW, Hainsworth R. Effects of simulated obstructive sleep apnoea on the human carotid baroreceptor-vascular resistance reflex. J Physiol 2004; 557(pt 3):1055–1065. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062513

- Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Merchia P, Malhotra A. Central sleep apnea: pathophysiology and treatment. Chest 2007; 131(2):595–607. doi:10.1378/chest.06.2287

- Lévy P, Pépin JL, Arnaud C, et al. Intermittent hypoxia and sleep-disordered breathing: current concepts and perspectives. Eur Respir J 2008; 32(4):1082–1095. doi:10.1183/09031936.00013308

- Stevenson IH, Roberts-Thomson KC, Kistler PM, et al. Atrial electrophysiology is altered by acute hypercapnia but not hypoxemia: implications for promotion of atrial fibrillation in pulmonary disease and sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7(9):1263–1270. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.03.020

- Tung P, Levitzky YS, Wang R, et al. Obstructive and central sleep apnea and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in a community cohort of men and women. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6(7). doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004500

- Iwasaki YK, Shi Y, Benito B, et al. Determinants of atrial fibrillation in an animal model of obesity and acute obstructive sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9(9):1409–1416.e1. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.024

- Monahan K, Storfer-Isser A, Mehra R, et al. Triggering of nocturnal arrhythmias by sleep-disordered breathing events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54(19):1797–1804. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.038

- Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2003; 107(20):2589–2594. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000068337.25994.21

- Ng CY, Liu T, Shehata M, Stevens S, Chugh SS, Wang X. Meta-analysis of obstructive sleep apnea as predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108(1):47–51. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.343

- Naruse Y, Tada H, Satoh M, et al. Concomitant obstructive sleep apnea increases the recurrence of atrial fibrillation following radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: clinical impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Heart Rhythm 2013; 10(3):331–337. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.11.015

- Fein AS, Shvilkin A, Shah D, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62(4):300–305. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.052

- Patel D, Mohanty P, Di Biase L, et al. Safety and efficacy of pulmonary vein antral isolation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: the impact of continuous positive airway pressure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3(5):445–451. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.109.858381

- Neilan TG, Farhad H, Dodson JA, et al. Effect of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac structure and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2(6):e000421. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000421

- Mehra R, Stone KL, Varosy PD, et al. Nocturnal arrhythmias across a spectrum of obstructive and central sleep-disordered breathing in older men: outcomes of sleep disorders in older men (MrOS sleep) study. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(12):1147–1155. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.138

- Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160(4):1101–1106. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9903020

- Yumino D, Wang H, Floras JS, et al. Prevalence and physiological predictors of sleep apnea in patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail 2009; 15(4):279–285. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.11.015

- May AM, Blackwell T, Stone PH, et al; MrOS Sleep (Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men) Study Group. Central sleep-disordered breathing predicts incident atrial fibrillation in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193(7):783–791. doi:10.1164/rccm.201508-1523OC

- Porthan KM, Melin JH, Kupila JT, Venho KK, Partinen MM. Prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome in lone atrial fibrillation: a case-control study. Chest 2004; 125(3):879–885. doi:10.1378/chest.125.3.879

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014; 130(23):e199–e267. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041

- Writing Group Members; January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16(8):e66–e93. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.01.024

- Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131(7):485–491. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002

- Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-bang questionnaire a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2016; 149(3):631–638. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0903

- Marti-Soler H, Hirotsu C, Marques-Vidal P, et al. The NoSAS score for screening of sleep-disordered breathing: a derivation and validation study. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4(9):742–748. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30075-3

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13(3):479–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

- Braga B, Poyares D, Cintra F, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and chronic atrial fibrillation. Sleep Med 2009; 10(2):212–216. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2007.12.007

- Gami AS, Pressman G, Caples SM, et al. Association of atrial fibrillation and obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 2004; 110(4):364–367. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000136587.68725.8E

- Stevenson IH, Teichtahl H, Cunnington D, Ciavarella S, Gordon I, Kalman JM. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation patients with normal left ventricular function. Eur Heart J 2008; 29(13):1662–1669. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehn214

- Mehra R, Benjamin EJ, Shahar E, et al. Association of nocturnal arrhythmias with sleep-disordered breathing: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173(8):910–916. doi:10.1164/rccm.200509-1442OC

- Cooper VL, Bowker CM, Pearson SB, Elliott MW, Hainsworth R. Effects of simulated obstructive sleep apnoea on the human carotid baroreceptor-vascular resistance reflex. J Physiol 2004; 557(pt 3):1055–1065. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062513

- Eckert DJ, Jordan AS, Merchia P, Malhotra A. Central sleep apnea: pathophysiology and treatment. Chest 2007; 131(2):595–607. doi:10.1378/chest.06.2287

- Lévy P, Pépin JL, Arnaud C, et al. Intermittent hypoxia and sleep-disordered breathing: current concepts and perspectives. Eur Respir J 2008; 32(4):1082–1095. doi:10.1183/09031936.00013308

- Stevenson IH, Roberts-Thomson KC, Kistler PM, et al. Atrial electrophysiology is altered by acute hypercapnia but not hypoxemia: implications for promotion of atrial fibrillation in pulmonary disease and sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7(9):1263–1270. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.03.020

- Tung P, Levitzky YS, Wang R, et al. Obstructive and central sleep apnea and the risk of incident atrial fibrillation in a community cohort of men and women. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6(7). doi:10.1161/JAHA.116.004500

- Iwasaki YK, Shi Y, Benito B, et al. Determinants of atrial fibrillation in an animal model of obesity and acute obstructive sleep apnea. Heart Rhythm 2012; 9(9):1409–1416.e1. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.024

- Monahan K, Storfer-Isser A, Mehra R, et al. Triggering of nocturnal arrhythmias by sleep-disordered breathing events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54(19):1797–1804. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.038

- Kanagala R, Murali NS, Friedman PA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2003; 107(20):2589–2594. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000068337.25994.21

- Ng CY, Liu T, Shehata M, Stevens S, Chugh SS, Wang X. Meta-analysis of obstructive sleep apnea as predictor of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108(1):47–51. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.343

- Naruse Y, Tada H, Satoh M, et al. Concomitant obstructive sleep apnea increases the recurrence of atrial fibrillation following radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: clinical impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Heart Rhythm 2013; 10(3):331–337. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.11.015

- Fein AS, Shvilkin A, Shah D, et al. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea reduces the risk of atrial fibrillation recurrence after catheter ablation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62(4):300–305. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.052

- Patel D, Mohanty P, Di Biase L, et al. Safety and efficacy of pulmonary vein antral isolation in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: the impact of continuous positive airway pressure. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3(5):445–451. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.109.858381

- Neilan TG, Farhad H, Dodson JA, et al. Effect of sleep apnea and continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac structure and recurrence of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc 2013; 2(6):e000421. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000421

- Mehra R, Stone KL, Varosy PD, et al. Nocturnal arrhythmias across a spectrum of obstructive and central sleep-disordered breathing in older men: outcomes of sleep disorders in older men (MrOS sleep) study. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169(12):1147–1155. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.138

- Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD, Newton G, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999; 160(4):1101–1106. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9903020

- Yumino D, Wang H, Floras JS, et al. Prevalence and physiological predictors of sleep apnea in patients with heart failure and systolic dysfunction. J Card Fail 2009; 15(4):279–285. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.11.015

- May AM, Blackwell T, Stone PH, et al; MrOS Sleep (Outcomes of Sleep Disorders in Older Men) Study Group. Central sleep-disordered breathing predicts incident atrial fibrillation in older men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016; 193(7):783–791. doi:10.1164/rccm.201508-1523OC

- Porthan KM, Melin JH, Kupila JT, Venho KK, Partinen MM. Prevalence of sleep apnea syndrome in lone atrial fibrillation: a case-control study. Chest 2004; 125(3):879–885. doi:10.1378/chest.125.3.879

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; ACC/AHA Task Force Members. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2014; 130(23):e199–e267. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000041

- Writing Group Members; January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2019; 16(8):e66–e93. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.01.024

- Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131(7):485–491. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-131-7-199910050-00002

- Chung F, Abdullah HR, Liao P. STOP-bang questionnaire a practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 2016; 149(3):631–638. doi:10.1378/chest.15-0903

- Marti-Soler H, Hirotsu C, Marques-Vidal P, et al. The NoSAS score for screening of sleep-disordered breathing: a derivation and validation study. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4(9):742–748. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30075-3

- Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med 2017; 13(3):479–504. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6506

What are the risks to inpatients during hospital construction or renovation?

Hospital-acquired infections related to construction and renovation activities account for more than 5,000 deaths per year across the United States.1

Hospital construction, renovation, and demolition projects ultimately serve the interests of patients, but they also can put inpatients at risk of mold infection, Legionnaires disease, sleep deprivation, exacerbation of lung disease, and in rare cases, physical injury.

Hospitals are in a continuous state of transformation to meet the needs of medical and technologic advances and an increasing patient population,1 and in the last 10 years, more than $200 billion has been spent on construction projects at US healthcare facilities. Therefore, constant attention is needed to reduce the risks to the health of hospitalized patients during these projects.

HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED INFECTIONS

Mold infections

Construction can cause substantial dust contamination and scatter large amounts of fungal spores. An analysis conducted during a period of excavation at a hospital campus showed a significant association between excavation activities and hospital-acquired mold infections (hazard ratio [HR] 2.8, P = .01) but not yeast infections (HR 0.75, P = .78).2

Aspergillus species have been the organisms most commonly involved in hospital-acquired mold infection. In a review of 53 studies including 458 patients,3A fumigatus was identified in 154 patients, and A flavus was identified in 101 patients. A niger, A terreus, A nidulans, Zygomycetes, and other fungi were also identified, but to a much lesser extent. Hematologic malignancies were the predominant underlying morbidity in 299 patients. Half of the sources of healthcare-associated Aspergillus outbreaks were estimated to result from construction and renovation activities within or surrounding the hospital.3

Heavy demolition and transportation of wreckage have been found to cause the greatest concentrations of Aspergillus species,1 but even small concentrations may be sufficient to cause infection in high-risk hospitalized patients.3 Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is the mold infection most commonly associated with these activities, particularly in immunocompromised and critically ill patients. It is characterized by invasion of lung tissue by Aspergillus hyphae. Hematogenous dissemination occurs in about 25% of patients, and the death rate often exceeds 50%.4

A review of cases of fungal infection during hospital construction, renovation, and demolition projects from 1976 to 2014 identified 372 infected patients, of whom 180 died.5 The majority of infections were due to Aspergillus. Other fungi included Rhizopus, Candida, and Fusarium. Infections occurred mainly in patients with hematologic malignancies and patients who had undergone stem cell transplant (76%), followed by patients with other malignancies or transplant (19%). Rarely affected were patients in the intensive care unit or patients with rheumatologic diseases or on hemodialysis.5

Legionnaires disease

Legionnaires disease is a form of atypical pneumonia caused by the bacterium Legionella, often associated with differing degrees of gastrointestinal symptoms. Legionella species are the bacteria most often associated with construction in hospitals, as construction and demolition often result in collections of stagnant water.

The primary mode of transmission is inhalation of contaminated mist or aerosols. Legionella species can also colonize newly constructed hospital buildings within weeks of installation of water fixtures.

In a large university-affiliated hospital, 2 cases of nosocomial legionellosis were identified during a period of major construction.6 An epidemiologic investigation traced the source to a widespread contamination of potable water within the hospital. One patient’s isolate was similar to that of a water sample from the faucet in his room, and an association between Legionnaires disease and construction was postulated.

Another institution’s newly constructed hematology-oncology unit identified 10 cases of Legionnaires disease over a 12-week period in patients and visitors with exposure to the unit during and within the incubation period.7 A clinical and environmental assessment found 3 clinical isolates of Legionella identical to environmental isolates found from the unit, strongly implicating the potable water system as the likely source.7

In Ohio, 11 cases of hospital-acquired Legionnaires disease were identified in patients moved to a newly constructed 12-story addition to a hospital, and 1 of those died.8

Legionella infections appear to be less common than mold infections when reviewing the available literature on patients exposed to hospital construction, renovation, or demolition activities. Yet unlike mold infections, which occur mostly in immunocompromised patients, Legionella also affects people with normal immunity.1

NONCOMMUNICABLE ILLNESSES

Sleep deprivation

Noise in hospitals has been linked to sleep disturbances in inpatients. A study using noise dosimeters in a university hospital found a mean continuous noise level of 63.5 dBA (A-weighting of decibels indicates risk of hearing loss) over a 24-hour period, a level more than 2 times higher than the recommended 30 dBA.9 The same study also found a significant correlation between sleep disturbance in inpatients and increasing noise levels, in a dose-response manner.

Common sources of noise during construction may include power generators, welding and cutting equipment, and transport of materials. While construction activities themselves have yet to be directly linked to sleep deprivation in patients, construction is inevitably accompanied by noise.

Noise is the most common factor interfering with sleep reported by hospitalized patients. Other effects of noise on patients include a rise in heart rate and blood pressure, increased cholesterol and triglyceride levels, increased use of sedatives, and longer length of stay.9,10 Although construction is rarely done at night, patients generally take naps during the day, so the noise is disruptive.

Physical injuries

Hospitalized patients rarely suffer injuries related to hospital construction. However, these incidents may be underreported. Few cases of physical injury in patients exposed to construction or renovation in healthcare facilities can be found through a Web search.11,12

Exacerbation of lung disease

Inhalation of indoor air pollutants exposed during renovation can directly trigger an inflammatory response and cause exacerbation in patients with chronic lung diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. No study has specifically examined the effect of hospital construction or renovation on exacerbation of chronic lung diseases in hospitalized patients. Nevertheless, dust and indoor air pollutants from building renovation have often been reported as agents associated with work-related asthma.13

THE MESSAGE

Although the risks to inpatients during hospital construction projects appear minimal, their effect can at times be detrimental, especially to the immunocompromised. Hospitals should adhere to infection control risk assessment protocols during construction events. The small number of outbreaks of construction-related infections can make the diagnosis of nosocomial origin of these infections challenging; a high index of suspicion is needed.

Currently in the United States, there is no standard regarding acceptable levels of airborne mold concentrations, and data to support routine hospital air sampling or validation of available air samplers are inadequate. This remains an area for future research.14,15

Certain measures have been shown to significantly decrease the risk of mold infections and other nosocomial infections during construction projects, including16:

- Effective dust control through containment units and barriers

- Consistent use of high-efficiency particulate air filters in hospital units that care for immunocompromised and critically ill patients

- Routine surveillance.

Noise and vibration can be reduced by temporary walls and careful tool selection and scheduling. Similarly, temporary walls and other barriers help protect healthcare employees and patients from the risk of direct physical injury.

Preconstruction risk assessments that address infection control, safety, noise, and air quality are crucial, and the Joint Commission generally requires such assessments. Further, education of hospital staff and members of the construction team about the potential detrimental effects of hospital construction and renovation is essential to secure a safe environment.

- Clair JD, Colatrella S. Opening Pandora’s (tool) box: health care construction and associated risk for nosocomial infection. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2013; 13(3):177–183. pmid:23961740

- Pokala HR, Leonard D, Cox J, et al. Association of hospital construction with the development of healthcare associated environmental mold infections (HAEMI) in pediatric patients with leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014; 61(2):276–280. doi:10.1002/pbc.24685

- Vonberg RP, Gastmeier P. Nosocomial aspergillosis in outbreak settings. J Hosp Infect 2006; 63(3):246–254. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2006.02.014

- Kanj A, Abdallah N, Soubani AO. The spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Respir Med 2018; 141:121–131. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.029

- Kanamori H, Rutala WA, Sickbert-Bennett EE, Weber DJ. Review of fungal outbreaks and infection prevention in healthcare settings during construction and renovation. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(3):433–444. doi:10.1093/cid/civ297

- Perola O, Kauppinen J, Kusnetsov J, Heikkinen J, Jokinen C, Katila ML. Nosocomial Legionella pneumophila serogroup 5 outbreak associated with persistent colonization of a hospital water system. APMIS 2002; 110(12):863–868. pmid:12645664

- Francois Watkins LK, Toews KE, Harris AM, et al. Lessons from an outbreak of Legionnaires disease on a hematology-oncology unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2017; 38(3):306–313. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.281

- Lin YE, Stout JE, Yu VL. Prevention of hospital-acquired legionellosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2011; 24(4):350–356. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283486c6e

- Park MJ, Yoo JH, Cho BW, Kim KT, Jeong WC, Ha M. Noise in hospital rooms and sleep disturbance in hospitalized medical patients. Environ Health Toxicol 2014; 29:e2014006. doi:10.5620/eht.2014.29.e2014006

- Buxton OM, Ellenbogen JM, Wang W, et al. Sleep disruption due to hospital noises: a prospective evaluation. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(3):170–179. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00472

- Heldt D; The Gazette. Accident will delay University of Iowa Hospitals construction work for several days. www.thegazette.com/2013/03/08/university-of-iowa-hospitals-patient-injured-by-falling-construction-debris. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Darrah N; Fox News. Texas hospital explosion kills 1, leaves 12 injured. www.foxnews.com/us/texas-hospital-explosion-kills-1-leaves-12-injured. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Work-related asthma: most frequently reported agents associated with work-related asthma cases by state, 2009–2012. wwwn.cdc.gov/eworld/Data/926. Accessed July 22, 2019.

- Patterson TF, Thompson GR 3rd, Denning DW, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Aspergillosis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63(4):e1–e60. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw326

- Chang CC, Athan E, Morrissey CO, Slavin MA. Preventing invasive fungal infection during hospital building works. Intern Med J 2008; 38(6b):538–541. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2008.01727.x

- Oren I, Haddad N, Finkelstein R, Rowe JM. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in neutropenic patients during hospital construction: before and after chemoprophylaxis and institution of HEPA filters. Am J Hematol 2001; 66(4):257–262. doi:10.1002/ajh.1054

Hospital-acquired infections related to construction and renovation activities account for more than 5,000 deaths per year across the United States.1

Hospital construction, renovation, and demolition projects ultimately serve the interests of patients, but they also can put inpatients at risk of mold infection, Legionnaires disease, sleep deprivation, exacerbation of lung disease, and in rare cases, physical injury.

Hospitals are in a continuous state of transformation to meet the needs of medical and technologic advances and an increasing patient population,1 and in the last 10 years, more than $200 billion has been spent on construction projects at US healthcare facilities. Therefore, constant attention is needed to reduce the risks to the health of hospitalized patients during these projects.

HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED INFECTIONS

Mold infections

Construction can cause substantial dust contamination and scatter large amounts of fungal spores. An analysis conducted during a period of excavation at a hospital campus showed a significant association between excavation activities and hospital-acquired mold infections (hazard ratio [HR] 2.8, P = .01) but not yeast infections (HR 0.75, P = .78).2

Aspergillus species have been the organisms most commonly involved in hospital-acquired mold infection. In a review of 53 studies including 458 patients,3A fumigatus was identified in 154 patients, and A flavus was identified in 101 patients. A niger, A terreus, A nidulans, Zygomycetes, and other fungi were also identified, but to a much lesser extent. Hematologic malignancies were the predominant underlying morbidity in 299 patients. Half of the sources of healthcare-associated Aspergillus outbreaks were estimated to result from construction and renovation activities within or surrounding the hospital.3

Heavy demolition and transportation of wreckage have been found to cause the greatest concentrations of Aspergillus species,1 but even small concentrations may be sufficient to cause infection in high-risk hospitalized patients.3 Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is the mold infection most commonly associated with these activities, particularly in immunocompromised and critically ill patients. It is characterized by invasion of lung tissue by Aspergillus hyphae. Hematogenous dissemination occurs in about 25% of patients, and the death rate often exceeds 50%.4

A review of cases of fungal infection during hospital construction, renovation, and demolition projects from 1976 to 2014 identified 372 infected patients, of whom 180 died.5 The majority of infections were due to Aspergillus. Other fungi included Rhizopus, Candida, and Fusarium. Infections occurred mainly in patients with hematologic malignancies and patients who had undergone stem cell transplant (76%), followed by patients with other malignancies or transplant (19%). Rarely affected were patients in the intensive care unit or patients with rheumatologic diseases or on hemodialysis.5

Legionnaires disease

Legionnaires disease is a form of atypical pneumonia caused by the bacterium Legionella, often associated with differing degrees of gastrointestinal symptoms. Legionella species are the bacteria most often associated with construction in hospitals, as construction and demolition often result in collections of stagnant water.

The primary mode of transmission is inhalation of contaminated mist or aerosols. Legionella species can also colonize newly constructed hospital buildings within weeks of installation of water fixtures.

In a large university-affiliated hospital, 2 cases of nosocomial legionellosis were identified during a period of major construction.6 An epidemiologic investigation traced the source to a widespread contamination of potable water within the hospital. One patient’s isolate was similar to that of a water sample from the faucet in his room, and an association between Legionnaires disease and construction was postulated.

Another institution’s newly constructed hematology-oncology unit identified 10 cases of Legionnaires disease over a 12-week period in patients and visitors with exposure to the unit during and within the incubation period.7 A clinical and environmental assessment found 3 clinical isolates of Legionella identical to environmental isolates found from the unit, strongly implicating the potable water system as the likely source.7

In Ohio, 11 cases of hospital-acquired Legionnaires disease were identified in patients moved to a newly constructed 12-story addition to a hospital, and 1 of those died.8

Legionella infections appear to be less common than mold infections when reviewing the available literature on patients exposed to hospital construction, renovation, or demolition activities. Yet unlike mold infections, which occur mostly in immunocompromised patients, Legionella also affects people with normal immunity.1

NONCOMMUNICABLE ILLNESSES

Sleep deprivation

Noise in hospitals has been linked to sleep disturbances in inpatients. A study using noise dosimeters in a university hospital found a mean continuous noise level of 63.5 dBA (A-weighting of decibels indicates risk of hearing loss) over a 24-hour period, a level more than 2 times higher than the recommended 30 dBA.9 The same study also found a significant correlation between sleep disturbance in inpatients and increasing noise levels, in a dose-response manner.

Common sources of noise during construction may include power generators, welding and cutting equipment, and transport of materials. While construction activities themselves have yet to be directly linked to sleep deprivation in patients, construction is inevitably accompanied by noise.

Noise is the most common factor interfering with sleep reported by hospitalized patients. Other effects of noise on patients include a rise in heart rate and blood pressure, increased cholesterol and triglyceride levels, increased use of sedatives, and longer length of stay.9,10 Although construction is rarely done at night, patients generally take naps during the day, so the noise is disruptive.

Physical injuries

Hospitalized patients rarely suffer injuries related to hospital construction. However, these incidents may be underreported. Few cases of physical injury in patients exposed to construction or renovation in healthcare facilities can be found through a Web search.11,12

Exacerbation of lung disease

Inhalation of indoor air pollutants exposed during renovation can directly trigger an inflammatory response and cause exacerbation in patients with chronic lung diseases such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. No study has specifically examined the effect of hospital construction or renovation on exacerbation of chronic lung diseases in hospitalized patients. Nevertheless, dust and indoor air pollutants from building renovation have often been reported as agents associated with work-related asthma.13

THE MESSAGE

Although the risks to inpatients during hospital construction projects appear minimal, their effect can at times be detrimental, especially to the immunocompromised. Hospitals should adhere to infection control risk assessment protocols during construction events. The small number of outbreaks of construction-related infections can make the diagnosis of nosocomial origin of these infections challenging; a high index of suspicion is needed.

Currently in the United States, there is no standard regarding acceptable levels of airborne mold concentrations, and data to support routine hospital air sampling or validation of available air samplers are inadequate. This remains an area for future research.14,15

Certain measures have been shown to significantly decrease the risk of mold infections and other nosocomial infections during construction projects, including16:

- Effective dust control through containment units and barriers

- Consistent use of high-efficiency particulate air filters in hospital units that care for immunocompromised and critically ill patients

- Routine surveillance.

Noise and vibration can be reduced by temporary walls and careful tool selection and scheduling. Similarly, temporary walls and other barriers help protect healthcare employees and patients from the risk of direct physical injury.

Preconstruction risk assessments that address infection control, safety, noise, and air quality are crucial, and the Joint Commission generally requires such assessments. Further, education of hospital staff and members of the construction team about the potential detrimental effects of hospital construction and renovation is essential to secure a safe environment.

Hospital-acquired infections related to construction and renovation activities account for more than 5,000 deaths per year across the United States.1

Hospital construction, renovation, and demolition projects ultimately serve the interests of patients, but they also can put inpatients at risk of mold infection, Legionnaires disease, sleep deprivation, exacerbation of lung disease, and in rare cases, physical injury.

Hospitals are in a continuous state of transformation to meet the needs of medical and technologic advances and an increasing patient population,1 and in the last 10 years, more than $200 billion has been spent on construction projects at US healthcare facilities. Therefore, constant attention is needed to reduce the risks to the health of hospitalized patients during these projects.

HOSPITAL-ACQUIRED INFECTIONS

Mold infections

Construction can cause substantial dust contamination and scatter large amounts of fungal spores. An analysis conducted during a period of excavation at a hospital campus showed a significant association between excavation activities and hospital-acquired mold infections (hazard ratio [HR] 2.8, P = .01) but not yeast infections (HR 0.75, P = .78).2

Aspergillus species have been the organisms most commonly involved in hospital-acquired mold infection. In a review of 53 studies including 458 patients,3A fumigatus was identified in 154 patients, and A flavus was identified in 101 patients. A niger, A terreus, A nidulans, Zygomycetes, and other fungi were also identified, but to a much lesser extent. Hematologic malignancies were the predominant underlying morbidity in 299 patients. Half of the sources of healthcare-associated Aspergillus outbreaks were estimated to result from construction and renovation activities within or surrounding the hospital.3

Heavy demolition and transportation of wreckage have been found to cause the greatest concentrations of Aspergillus species,1 but even small concentrations may be sufficient to cause infection in high-risk hospitalized patients.3 Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is the mold infection most commonly associated with these activities, particularly in immunocompromised and critically ill patients. It is characterized by invasion of lung tissue by Aspergillus hyphae. Hematogenous dissemination occurs in about 25% of patients, and the death rate often exceeds 50%.4

A review of cases of fungal infection during hospital construction, renovation, and demolition projects from 1976 to 2014 identified 372 infected patients, of whom 180 died.5 The majority of infections were due to Aspergillus. Other fungi included Rhizopus, Candida, and Fusarium. Infections occurred mainly in patients with hematologic malignancies and patients who had undergone stem cell transplant (76%), followed by patients with other malignancies or transplant (19%). Rarely affected were patients in the intensive care unit or patients with rheumatologic diseases or on hemodialysis.5

Legionnaires disease

Legionnaires disease is a form of atypical pneumonia caused by the bacterium Legionella, often associated with differing degrees of gastrointestinal symptoms. Legionella species are the bacteria most often associated with construction in hospitals, as construction and demolition often result in collections of stagnant water.

The primary mode of transmission is inhalation of contaminated mist or aerosols. Legionella species can also colonize newly constructed hospital buildings within weeks of installation of water fixtures.

In a large university-affiliated hospital, 2 cases of nosocomial legionellosis were identified during a period of major construction.6 An epidemiologic investigation traced the source to a widespread contamination of potable water within the hospital. One patient’s isolate was similar to that of a water sample from the faucet in his room, and an association between Legionnaires disease and construction was postulated.

Another institution’s newly constructed hematology-oncology unit identified 10 cases of Legionnaires disease over a 12-week period in patients and visitors with exposure to the unit during and within the incubation period.7 A clinical and environmental assessment found 3 clinical isolates of Legionella identical to environmental isolates found from the unit, strongly implicating the potable water system as the likely source.7

In Ohio, 11 cases of hospital-acquired Legionnaires disease were identified in patients moved to a newly constructed 12-story addition to a hospital, and 1 of those died.8

Legionella infections appear to be less common than mold infections when reviewing the available literature on patients exposed to hospital construction, renovation, or demolition activities. Yet unlike mold infections, which occur mostly in immunocompromised patients, Legionella also affects people with normal immunity.1

NONCOMMUNICABLE ILLNESSES

Sleep deprivation

Noise in hospitals has been linked to sleep disturbances in inpatients. A study using noise dosimeters in a university hospital found a mean continuous noise level of 63.5 dBA (A-weighting of decibels indicates risk of hearing loss) over a 24-hour period, a level more than 2 times higher than the recommended 30 dBA.9 The same study also found a significant correlation between sleep disturbance in inpatients and increasing noise levels, in a dose-response manner.