User login

Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Hospitalists: A Position Statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Many hospitalists incorporate point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) into their daily practice because it adds value to their bedside evaluation of patients. However, standards for training and assessing hospitalists in POCUS have not yet been established. Other acute care specialties, including emergency medicine and critical care medicine, have already incorporated POCUS into their graduate medical education training programs, but most internal medicine residency programs are only beginning to provide POCUS training.1

Several features distinguish POCUS from comprehensive ultrasound examinations. First, POCUS is designed to answer focused questions, whereas comprehensive ultrasound examinations evaluate all organs in an anatomical region; for example, an abdominal POCUS exam may evaluate only for presence or absence of intraperitoneal free fluid, whereas a comprehensive examination of the right upper quadrant will evaluate the liver, gallbladder, and biliary ducts. Second, POCUS examinations are generally performed by the same clinician who generates the relevant clinical question to answer with POCUS and ultimately integrates the findings into the patient’s care.2 By contrast, comprehensive ultrasound examinations involve multiple providers and steps: a clinician generates a relevant clinical question and requests an ultrasound examination that is acquired by a sonographer, interpreted by a radiologist, and reported back to the requesting clinician. Third, POCUS is often used to evaluate multiple body systems. For example, to evaluate a patient with undifferentiated hypotension, a multisystem POCUS examination of the heart, inferior vena cava, lungs, abdomen, and lower extremity veins is typically performed. Finally, POCUS examinations can be performed serially to investigate changes in clinical status or evaluate response to therapy, such as monitoring the heart, lungs, and inferior vena cava during fluid resuscitation.

The purpose of this position statement is to inform a broad audience about how hospitalists are using diagnostic and procedural applications of POCUS. This position statement does not mandate that hospitalists use POCUS. Rather, it is intended to provide guidance on the safe and effective use of POCUS by the hospitalists who use it and the administrators who oversee its use. We discuss POCUS (1) applications, (2) training, (3) assessments, and (4) program management. This position statement was reviewed and approved by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Executive Committee in March 2018.

APPLICATIONS

As outlined in our earlier position statements,3,4 ultrasound guidance lowers complication rates and increases success rates of invasive bedside procedures. Diagnostic POCUS can guide clinical decision making prior to bedside procedures. For instance, hospitalists may use POCUS to assess the size and character of a pleural effusion to help determine the most appropriate management strategy: observation, medical treatment, thoracentesis, chest tube placement, or surgical therapy. Furthermore, diagnostic POCUS can be used to rapidly assess for immediate postprocedural complications, such as pneumothorax, or if the patient develops new symptoms.

TRAINING

Basic Knowledge

Basic knowledge includes fundamentals of ultrasound physics; safety;4 anatomy; physiology; and device operation, including maintenance and cleaning. Basic knowledge can be taught by multiple methods, including live or recorded lectures, online modules, or directed readings.

Image Acquisition

Training should occur across multiple types of patients (eg, obese, cachectic, postsurgical) and clinical settings (eg, intensive care unit, general medicine wards, emergency department) when available. Training is largely hands-on because the relevant skills involve integration of 3D anatomy with spatial manipulation, hand-eye coordination, and fine motor movements. Virtual reality ultrasound simulators may accelerate mastery, particularly for cardiac image acquisition, and expose learners to standardized sets of pathologic findings. Real-time bedside feedback on image acquisition is ideal because understanding how ultrasound probe manipulation affects the images acquired is essential to learning.

Image Interpretation

Training in image interpretation relies on visual pattern recognition of normal and abnormal findings. Therefore, the normal to abnormal spectrum should be broad, and learners should maintain a log of what abnormalities have been identified. Giving real-time feedback at the bedside is ideal because of the connection between image acquisition and interpretation. Image interpretation can be taught through didactic sessions, image review sessions, or review of teaching files with annotated images.

Clinical Integration

Learners must interpret and integrate image findings with other clinical data considering the image quality, patient characteristics, and changing physiology. Clinical integration should be taught by instructors that share similar clinical knowledge as learners. Although sonographers are well suited to teach image acquisition, they should not be the sole instructors to teach hospitalists how to integrate ultrasound findings in clinical decision making. Likewise, emphasis should be placed on the appropriate use of POCUS within a provider’s skill set. Learners must appreciate the clinical significance of POCUS findings, including recognition of incidental findings that may require further workup. Supplemental training in clinical integration can occur through didactics that include complex patient scenarios.

Pathways

Clinical competency can be achieved with training adherent to five criteria. First, the training environment should be similar to where the trainee will practice. Second, training and feedback should occur in real time. Third, specific applications should be taught rather than broad training in “hospitalist POCUS.” Each application requires unique skills and knowledge, including image acquisition pitfalls and artifacts. Fourth, clinical competence must be achieved and demonstrated; it is not necessarily gained through experience. Fifth, once competency is achieved, continued education and feedback are necessary to ensure it is maintained.

Residency-based POCUS training pathways can best fulfill these criteria. They may eventually become commonplace, but until then alternative pathways must exist for hospitalist providers who are already in practice. There are three important attributes of such pathways. First, administrators’ expectations about learners’ clinical productivity must be realistically, but only temporarily, relaxed; otherwise, competing demands on time will likely overwhelm learners and subvert training. Second, training should begin through a local or national hands-on training program. The SHM POCUS certificate program consolidates training for common diagnostic POCUS applications for hospitalists.6 Other medical societies offer training for their respective clinical specialties.7 Third, once basic POCUS training has begun, longitudinal training should continue ideally with a local hospitalist POCUS expert.

In some settings, a subgroup of hospitalists may not desire, or be able to achieve, competency in the manual skills of POCUS image acquisition. Nevertheless, hospitalists may still find value in understanding POCUS nomenclature, image pattern recognition, and the evidence and pitfalls behind clinical integration of specific POCUS findings. This subset of POCUS skills allows hospitalists to communicate effectively with and understand the clinical decisions made by their colleagues who are competent in POCUS use.

The minimal skills a hospitalist should possess to serve as a POCUS trainer include proficiency of basic knowledge, image acquisition, image interpretation, and clinical integration of the POCUS applications being taught; effectiveness as a hands-on instructor to teach image acquisition skills; and an in-depth understanding of common POCUS pitfalls and limitations.

ASSESSMENTS

Assessment methods for POCUS can include the following: knowledge-based questions, image acquisition using task-specific checklists on human or simulation models, image interpretation using a series of videos or still images with normal and abnormal findings, clinical integration using “next best step” in a multiple choice format with POCUS images, and simulation-based clinical scenarios. Assessment methods should be aligned with local availability of resources and trainers.

Basic Knowledge

Basic knowledge can be assessed via multiple choice questions assessing knowledge of ultrasound physics, image optimization, relevant anatomy, and limitations of POCUS imaging. Basic knowledge lies primarily in the cognitive domain and does not assess manual skills.

Image Acquisition

Image acquisition can be assessed by observation and rating of image quality. Where resources allow, assessment of image acquisition is likely best done through a combination of developing an image portfolio with a minimum number of high quality images, plus direct observation of image acquisition by an expert. Various programs have utilized minimum numbers of images acquired to help define competence with image acquisition skills.6–8 Although minimums may be a necessary step to gain competence, using them as a sole means to determine competence does not account for variable learning curves.9 As with other manual skills in hospital medicine, such as ultrasound-guided bedside procedures, minimum numbers are best used as a starting point for assessments.3,10 In this regard, portfolio development with meticulous attention to the gain, depth, and proper tomographic plane of images can monitor a hospitalist’s progress toward competence by providing objective assessments and feedback. Simulation may also be used as it allows assessment of image acquisition skills and an opportunity to provide real-time feedback, similar to direct observation but without actual patients.

Image Interpretation

Image interpretation is best assessed by an expert observing the learner at bedside; however, when bedside assessment is not possible, image interpretation skills may be assessed using multiple choice or free text interpretation of archived ultrasound images with normal and abnormal findings. This is often incorporated into the portfolio development portion of a training program, as learners can submit their image interpretation along with the video clip. Both normal and abnormal images can be used to assess anatomic recognition and interpretation. Emphasis should be placed on determining when an image is suboptimal for diagnosis (eg, incomplete exam or poor-quality images). Quality assurance programs should incorporate structured feedback sessions.

Clinical Integration

Assessment of clinical integration can be completed through case scenarios that assess knowledge, interpretation of images, and integration of findings into clinical decision making, which is often delivered via a computer-based assessment. Assessments should combine specific POCUS applications to evaluate common clinical problems in hospital medicine, such as undifferentiated hypotension and dyspnea. High-fidelity simulators can be used to blend clinical case scenarios with image acquisition, image interpretation, and clinical integration. When feasible, comprehensive feedback on how providers acquire, interpret, and apply ultrasound at the bedside is likely the best mechanism to assess clinical integration. This process can be done with a hospitalist’s own patients.

General Assessment

A general assessment that includes a summative knowledge and hands-on skills assessment using task-specific checklists can be performed upon completion of training. A high-fidelity simulator with dynamic or virtual anatomy can provide reproducible standardized assessments with variation in the type and difficulty of cases. When available, we encourage the use of dynamic assessments on actual patients that have both normal and abnormal ultrasound findings because simulated patient scenarios have limitations, even with the use of high-fidelity simulators. Programs are recommended to use formative and summative assessments for evaluation. Quantitative scoring systems using checklists are likely the best framework.11,12

CERTIFICATES AND CERTIFICATION

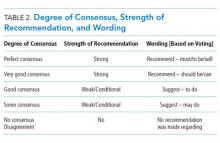

A certificate of completion is proof of a provider’s participation in an educational activity; it does not equate with competency, though it may be a step toward it. Most POCUS training workshops and short courses provide certificates of completion. Certification of competency is an attestation of a hospitalist’s basic competence within a defined scope of practice (Table 2).13 However, without longitudinal supervision and feedback, skills can decay; therefore, we recommend a longitudinal training program that provides mentored feedback and incorporates periodic competency assessments. At present, no national board certification in POCUS is available to grant external certification of competency for hospitalists.

External Certificate

Certificates of completion can be external through a national organization. An external certificate of completion designed for hospitalists includes the POCUS Certificate of Completion offered by SHM in collaboration with CHEST.6 This certificate program provides regional training options and longitudinal portfolio development. Other external certificates are also available to hospitalists.7,14,15

Most hospitalists are boarded by the American Board of Internal Medicine or the American Board of Family Medicine. These boards do not yet include certification of competency in POCUS. Other specialty boards, such as emergency medicine, include competency in POCUS. For emergency medicine, completion of an accredited residency training program and certification by the national board includes POCUS competency.

Internal Certificate

There are a few examples of successful local institutional programs that have provided internal certificates of competency.12,14 Competency assessments require significant resources including investment by both faculty and learners. Ongoing evaluation of competency should be based on quality assurance processes.

Credentialing and Privileging

The American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates in 1999 passed a resolution (AMA HR. 802) recommending hospitals follow specialty-specific guidelines for privileging decisions related to POCUS use.17 The resolution included a statement that, “ultrasound imaging is within the scope of practice of appropriately trained physicians.”

Some institutions have begun to rely on a combination of internal and external certificate programs to grant privileges to hospitalists.10 Although specific privileges for POCUS may not be required in some hospitals, some institutions may require certification of training and assessments prior to granting permission to use POCUS.

Hospitalist programs are encouraged to evaluate ongoing POCUS use by their providers after granting initial permission. If privileging is instituted by a hospital, hospitalists must play a significant role in determining the requirements for privileging and ongoing maintenance of skills.

Maintenance of Skills

All medical skills can decay with disuse, including those associated with POCUS.12,18 Thus, POCUS users should continue using POCUS regularly in clinical practice and participate in POCUS continuing medical education activities, ideally with ongoing assessments. Maintenance of skills may be confirmed through routine participation in a quality assurance program.

PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Use of POCUS in hospital medicine has unique considerations, and hospitalists should be integrally involved in decision making surrounding institutional POCUS program management. Appointing a dedicated POCUS director can help a program succeed.8

Equipment and Image Archiving

Several factors are important to consider when selecting an ultrasound machine: portability, screen size, and ease of use; integration with the electronic medical record and options for image archiving; manufacturer’s service plan, including technical and clinical support; and compliance with local infection control policies. The ability to easily archive and retrieve images is essential for quality assurance, continuing education, institutional quality improvement, documentation, and reimbursement. In certain scenarios, image archiving may not be possible (such as with personal handheld devices or in emergency situations) or necessary (such as with frequent serial examinations during fluid resuscitation). An image archive is ideally linked to reports, orders, and billing software.10,19 If such linkages are not feasible, parallel external storage that complies with regulatory standards (ie, HIPAA compliance) may be suitable.20

Documentation and Billing

Components of documentation include the indication and type of ultrasound examination performed, date and time of the examination, patient identifying information, name of provider(s) acquiring and interpreting the images, specific scanning protocols used, patient position, probe used, and findings. Documentation can occur through a standalone note or as part of another note, such as a progress note. Whenever possible, documentation should be timely to facilitate communication with other providers.

Billing is supported through the AMA Current Procedural Terminology codes for “focused” or “limited” ultrasound examinations (Appendix 9). The following three criteria must be satisfied for billing. First, images must be permanently stored. Specific requirements vary by insurance policy, though current practice suggests a minimum of one image demonstrating relevant anatomy and pathology for the ultrasound examination coded. For ultrasound-guided procedures that require needle insertion, images should be captured at the point of interest, and a procedure note should reflect that the needle was guided and visualized under ultrasound.21 Second, proper documentation must be entered in the medical record. Third, local institutional privileges for POCUS must be considered. Although privileges are not required to bill, some hospitals or payers may require them.

Quality Assurance

Published guidelines on quality assurance in POCUS are available from different specialty organizations, including emergency medicine, pediatric emergency medicine, critical care, anesthesiology, obstetrics, and cardiology.8,22–28 Quality assurance is aimed at ensuring that physicians maintain basic competency in using POCUS to influence bedside decisions.

Quality assurance should be carried out by an individual or committee with expertise in POCUS. Multidisciplinary QA programs in which hospital medicine providers are working collaboratively with other POCUS providers have been demonstrated to be highly effective.10 Oversight includes ensuring that providers using POCUS are appropriately trained,10,22,28 using the equipment correctly,8,26,28 and documenting properly. Some programs have implemented mechanisms to review and provide feedback on image acquisition, interpretation, and clinical integration.8,10 Other programs have compared POCUS findings with referral studies, such as comprehensive ultrasound examinations.

CONCLUSIONS

Practicing hospitalists must continue to collaborate with their institutions to build POCUS capabilities. In particular, they must work with their local privileging body to determine what credentials are required. The distinction between certificates of completion and certificates of competency, including whether those certificates are internal or external, is important in the credentialing process.

External certificates of competency are currently unavailable for most practicing hospitalists because ABIM certification does not include POCUS-related competencies. As internal medicine residency training programs begin to adopt POCUS training and certification into their educational curricula, we foresee a need to update the ABIM Policies and Procedures for Certification. Until then, we recommend that certificates of competency be defined and granted internally by local hospitalist groups.

Given the many advantages of POCUS over traditional tools, we anticipate its increasing implementation among hospitalists in the future. As with all medical technology, its role in clinical care should be continuously reexamined and redefined through health services research. Such information will be useful in developing practice guidelines, educational curricula, and training standards.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members that participated in the discussion and finalization of this position statement during the Point-of-care Ultrasound Faculty Retreat at the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference: Saaid Abdel-Ghani, Brandon Boesch, Joel Cho, Ria Dancel, Renee Dversdal, Ricardo Franco-Sadud, Benjamin Galen, Trevor P. Jensen, Mohit Jindal, Gordon Johnson, Linda M. Kurian, Gigi Liu, Charles M. LoPresti, Brian P. Lucas, Venkat Kalidindi, Benji Matthews, Anna Maw, Gregory Mints, Kreegan Reierson, Gerard Salame, Richard Schildhouse, Daniel Schnobrich, Nilam Soni, Kirk Spencer, Hiromizu Takahashi, David M. Tierney, Tanping Wong, and Toru Yamada.

1. Schnobrich DJ, Mathews BK, Trappey BE, Muthyala BK, Olson APJ. Entrusting internal medicine residents to use point of care ultrasound: Towards improved assessment and supervision. Med Teach. 2018:1-6. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457210.

2. Soni NJ, Lucas BP. Diagnostic point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):120-124. doi:10.1002/jhm.2285.

3. Lucas BP, Tierney DM, Jensen TP, et al. Credentialing of hospitalists in ultrasound-guided bedside procedures: a position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):117-125. doi:10.12788/jhm.2917.

4. Dancel R, Schnobrich D, Puri N, et al. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for adult thoracentesis: a position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):126-135. doi:10.12788/jhm.2940.

5. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, The Council. Implementation of the Principle of as Low as Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) for Medical and Dental Personnel.; 1990.

6. Society of Hospital Medicine. Point of Care Ultrasound course: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/clinical-topics/ultrasonography-cert/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

7. Critical Care Ultrasonography Certificate of Completion Program. CHEST. American College of Chest Physicians. http://www.chestnet.org/Education/Advanced-Clinical-Training/Certificate-of-Completion-Program/Critical-Care-Ultrasonography. Accessed February 6, 2018.

8. American College of Emergency Physicians Policy Statement: Emergency Ultrasound Guidelines. 2016. https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/ACEP-Ultrasound-Guidelines/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

9. Blehar DJ, Barton B, Gaspari RJ. Learning curves in emergency ultrasound education. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(5):574-582. doi:10.1111/acem.12653.

10. Mathews BK, Zwank M. Hospital medicine point of care ultrasound credentialing: an example protocol. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):767-772. doi:10.12788/jhm.2809.

11. Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Balachandran JS, Wayne DB. Use of simulation-based mastery learning to improve the quality of central venous catheter placement in a medical intensive care unit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):397-403. doi:10.1002/jhm.468.

12. Mathews BK, Reierson K, Vuong K, et al. The design and evaluation of the Comprehensive Hospitalist Assessment and Mentorship with Portfolios (CHAMP) ultrasound program. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):544-550. doi:10.12788/jhm.2938.

13. Soni NJ, Tierney DM, Jensen TP, Lucas BP. Certification of point-of-care ultrasound competency. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):775-776. doi:10.12788/jhm.2812.

14. Ultrasound Certification for Physicians. Alliance for Physician Certification and Advancement. APCA. https://apca.org/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

15. National Board of Echocardiography, Inc. https://www.echoboards.org/EchoBoards/News/2019_Adult_Critical_Care_Echocardiography_Exam.aspx. Accessed June 18, 2018.

16. Tierney DM. Internal Medicine Bedside Ultrasound Program (IMBUS). Abbott Northwestern. http://imbus.anwresidency.com/index.html. Accessed February 6, 2018.

17. American Medical Association House of Delegates Resolution H-230.960: Privileging for Ultrasound Imaging. Resolution 802. Policy Finder Website. http://search0.ama-assn.org/search/pfonline. Published 1999. Accessed February 18, 2018.

18. Kelm D, Ratelle J, Azeem N, et al. Longitudinal ultrasound curriculum improves long-term retention among internal medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):454-457. doi:10.4300/JGME-14-00284.1.

19. Flannigan MJ, Adhikari S. Point-of-care ultrasound work flow innovation: impact on documentation and billing. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(12):2467-2474. doi:10.1002/jum.14284.

20. Emergency Ultrasound: Workflow White Paper. https://www.acep.org/uploadedFiles/ACEP/memberCenter/SectionsofMembership/ultra/Workflow%20White%20Paper.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed February 18, 2018.

21. Ultrasound Coding and Reimbursement Document 2009. Emergency Ultrasound Section. American College of Emergency Physicians. http://emergencyultrasoundteaching.com/assets/2009_coding_update.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed February 18, 2018.

22. Mayo PH, Beaulieu Y, Doelken P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians/La Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest. 2009;135(4):1050-1060. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2305.

23. Frankel HL, Kirkpatrick AW, Elbarbary M, et al. Guidelines for the appropriate use of bedside general and cardiac ultrasonography in the evaluation of critically ill patients-part I: general ultrasonography. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(11):2479-2502. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000001216.

24. Levitov A, Frankel HL, Blaivas M, et al. Guidelines for the appropriate use of bedside general and cardiac ultrasonography in the evaluation of critically ill patients-part ii: cardiac ultrasonography. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(6):1206-1227. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000001847.

25. ACR–ACOG–AIUM–SRU Practice Parameter for the Performance of Obstetrical Ultrasound. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/us-ob.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed February 18, 2018.

26. AIUM practice guideline for documentation of an ultrasound examination. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33(6):1098-1102. doi:10.7863/ultra.33.6.1098.

27. Marin JR, Lewiss RE. Point-of-care ultrasonography by pediatric emergency medicine physicians. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1113-e1122. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0343.

28. Spencer KT, Kimura BJ, Korcarz CE, Pellikka PA, Rahko PS, Siegel RJ. Focused cardiac ultrasound: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(6):567-581. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2013.04.001.

Many hospitalists incorporate point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) into their daily practice because it adds value to their bedside evaluation of patients. However, standards for training and assessing hospitalists in POCUS have not yet been established. Other acute care specialties, including emergency medicine and critical care medicine, have already incorporated POCUS into their graduate medical education training programs, but most internal medicine residency programs are only beginning to provide POCUS training.1

Several features distinguish POCUS from comprehensive ultrasound examinations. First, POCUS is designed to answer focused questions, whereas comprehensive ultrasound examinations evaluate all organs in an anatomical region; for example, an abdominal POCUS exam may evaluate only for presence or absence of intraperitoneal free fluid, whereas a comprehensive examination of the right upper quadrant will evaluate the liver, gallbladder, and biliary ducts. Second, POCUS examinations are generally performed by the same clinician who generates the relevant clinical question to answer with POCUS and ultimately integrates the findings into the patient’s care.2 By contrast, comprehensive ultrasound examinations involve multiple providers and steps: a clinician generates a relevant clinical question and requests an ultrasound examination that is acquired by a sonographer, interpreted by a radiologist, and reported back to the requesting clinician. Third, POCUS is often used to evaluate multiple body systems. For example, to evaluate a patient with undifferentiated hypotension, a multisystem POCUS examination of the heart, inferior vena cava, lungs, abdomen, and lower extremity veins is typically performed. Finally, POCUS examinations can be performed serially to investigate changes in clinical status or evaluate response to therapy, such as monitoring the heart, lungs, and inferior vena cava during fluid resuscitation.

The purpose of this position statement is to inform a broad audience about how hospitalists are using diagnostic and procedural applications of POCUS. This position statement does not mandate that hospitalists use POCUS. Rather, it is intended to provide guidance on the safe and effective use of POCUS by the hospitalists who use it and the administrators who oversee its use. We discuss POCUS (1) applications, (2) training, (3) assessments, and (4) program management. This position statement was reviewed and approved by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Executive Committee in March 2018.

APPLICATIONS

As outlined in our earlier position statements,3,4 ultrasound guidance lowers complication rates and increases success rates of invasive bedside procedures. Diagnostic POCUS can guide clinical decision making prior to bedside procedures. For instance, hospitalists may use POCUS to assess the size and character of a pleural effusion to help determine the most appropriate management strategy: observation, medical treatment, thoracentesis, chest tube placement, or surgical therapy. Furthermore, diagnostic POCUS can be used to rapidly assess for immediate postprocedural complications, such as pneumothorax, or if the patient develops new symptoms.

TRAINING

Basic Knowledge

Basic knowledge includes fundamentals of ultrasound physics; safety;4 anatomy; physiology; and device operation, including maintenance and cleaning. Basic knowledge can be taught by multiple methods, including live or recorded lectures, online modules, or directed readings.

Image Acquisition

Training should occur across multiple types of patients (eg, obese, cachectic, postsurgical) and clinical settings (eg, intensive care unit, general medicine wards, emergency department) when available. Training is largely hands-on because the relevant skills involve integration of 3D anatomy with spatial manipulation, hand-eye coordination, and fine motor movements. Virtual reality ultrasound simulators may accelerate mastery, particularly for cardiac image acquisition, and expose learners to standardized sets of pathologic findings. Real-time bedside feedback on image acquisition is ideal because understanding how ultrasound probe manipulation affects the images acquired is essential to learning.

Image Interpretation

Training in image interpretation relies on visual pattern recognition of normal and abnormal findings. Therefore, the normal to abnormal spectrum should be broad, and learners should maintain a log of what abnormalities have been identified. Giving real-time feedback at the bedside is ideal because of the connection between image acquisition and interpretation. Image interpretation can be taught through didactic sessions, image review sessions, or review of teaching files with annotated images.

Clinical Integration

Learners must interpret and integrate image findings with other clinical data considering the image quality, patient characteristics, and changing physiology. Clinical integration should be taught by instructors that share similar clinical knowledge as learners. Although sonographers are well suited to teach image acquisition, they should not be the sole instructors to teach hospitalists how to integrate ultrasound findings in clinical decision making. Likewise, emphasis should be placed on the appropriate use of POCUS within a provider’s skill set. Learners must appreciate the clinical significance of POCUS findings, including recognition of incidental findings that may require further workup. Supplemental training in clinical integration can occur through didactics that include complex patient scenarios.

Pathways

Clinical competency can be achieved with training adherent to five criteria. First, the training environment should be similar to where the trainee will practice. Second, training and feedback should occur in real time. Third, specific applications should be taught rather than broad training in “hospitalist POCUS.” Each application requires unique skills and knowledge, including image acquisition pitfalls and artifacts. Fourth, clinical competence must be achieved and demonstrated; it is not necessarily gained through experience. Fifth, once competency is achieved, continued education and feedback are necessary to ensure it is maintained.

Residency-based POCUS training pathways can best fulfill these criteria. They may eventually become commonplace, but until then alternative pathways must exist for hospitalist providers who are already in practice. There are three important attributes of such pathways. First, administrators’ expectations about learners’ clinical productivity must be realistically, but only temporarily, relaxed; otherwise, competing demands on time will likely overwhelm learners and subvert training. Second, training should begin through a local or national hands-on training program. The SHM POCUS certificate program consolidates training for common diagnostic POCUS applications for hospitalists.6 Other medical societies offer training for their respective clinical specialties.7 Third, once basic POCUS training has begun, longitudinal training should continue ideally with a local hospitalist POCUS expert.

In some settings, a subgroup of hospitalists may not desire, or be able to achieve, competency in the manual skills of POCUS image acquisition. Nevertheless, hospitalists may still find value in understanding POCUS nomenclature, image pattern recognition, and the evidence and pitfalls behind clinical integration of specific POCUS findings. This subset of POCUS skills allows hospitalists to communicate effectively with and understand the clinical decisions made by their colleagues who are competent in POCUS use.

The minimal skills a hospitalist should possess to serve as a POCUS trainer include proficiency of basic knowledge, image acquisition, image interpretation, and clinical integration of the POCUS applications being taught; effectiveness as a hands-on instructor to teach image acquisition skills; and an in-depth understanding of common POCUS pitfalls and limitations.

ASSESSMENTS

Assessment methods for POCUS can include the following: knowledge-based questions, image acquisition using task-specific checklists on human or simulation models, image interpretation using a series of videos or still images with normal and abnormal findings, clinical integration using “next best step” in a multiple choice format with POCUS images, and simulation-based clinical scenarios. Assessment methods should be aligned with local availability of resources and trainers.

Basic Knowledge

Basic knowledge can be assessed via multiple choice questions assessing knowledge of ultrasound physics, image optimization, relevant anatomy, and limitations of POCUS imaging. Basic knowledge lies primarily in the cognitive domain and does not assess manual skills.

Image Acquisition

Image acquisition can be assessed by observation and rating of image quality. Where resources allow, assessment of image acquisition is likely best done through a combination of developing an image portfolio with a minimum number of high quality images, plus direct observation of image acquisition by an expert. Various programs have utilized minimum numbers of images acquired to help define competence with image acquisition skills.6–8 Although minimums may be a necessary step to gain competence, using them as a sole means to determine competence does not account for variable learning curves.9 As with other manual skills in hospital medicine, such as ultrasound-guided bedside procedures, minimum numbers are best used as a starting point for assessments.3,10 In this regard, portfolio development with meticulous attention to the gain, depth, and proper tomographic plane of images can monitor a hospitalist’s progress toward competence by providing objective assessments and feedback. Simulation may also be used as it allows assessment of image acquisition skills and an opportunity to provide real-time feedback, similar to direct observation but without actual patients.

Image Interpretation

Image interpretation is best assessed by an expert observing the learner at bedside; however, when bedside assessment is not possible, image interpretation skills may be assessed using multiple choice or free text interpretation of archived ultrasound images with normal and abnormal findings. This is often incorporated into the portfolio development portion of a training program, as learners can submit their image interpretation along with the video clip. Both normal and abnormal images can be used to assess anatomic recognition and interpretation. Emphasis should be placed on determining when an image is suboptimal for diagnosis (eg, incomplete exam or poor-quality images). Quality assurance programs should incorporate structured feedback sessions.

Clinical Integration

Assessment of clinical integration can be completed through case scenarios that assess knowledge, interpretation of images, and integration of findings into clinical decision making, which is often delivered via a computer-based assessment. Assessments should combine specific POCUS applications to evaluate common clinical problems in hospital medicine, such as undifferentiated hypotension and dyspnea. High-fidelity simulators can be used to blend clinical case scenarios with image acquisition, image interpretation, and clinical integration. When feasible, comprehensive feedback on how providers acquire, interpret, and apply ultrasound at the bedside is likely the best mechanism to assess clinical integration. This process can be done with a hospitalist’s own patients.

General Assessment

A general assessment that includes a summative knowledge and hands-on skills assessment using task-specific checklists can be performed upon completion of training. A high-fidelity simulator with dynamic or virtual anatomy can provide reproducible standardized assessments with variation in the type and difficulty of cases. When available, we encourage the use of dynamic assessments on actual patients that have both normal and abnormal ultrasound findings because simulated patient scenarios have limitations, even with the use of high-fidelity simulators. Programs are recommended to use formative and summative assessments for evaluation. Quantitative scoring systems using checklists are likely the best framework.11,12

CERTIFICATES AND CERTIFICATION

A certificate of completion is proof of a provider’s participation in an educational activity; it does not equate with competency, though it may be a step toward it. Most POCUS training workshops and short courses provide certificates of completion. Certification of competency is an attestation of a hospitalist’s basic competence within a defined scope of practice (Table 2).13 However, without longitudinal supervision and feedback, skills can decay; therefore, we recommend a longitudinal training program that provides mentored feedback and incorporates periodic competency assessments. At present, no national board certification in POCUS is available to grant external certification of competency for hospitalists.

External Certificate

Certificates of completion can be external through a national organization. An external certificate of completion designed for hospitalists includes the POCUS Certificate of Completion offered by SHM in collaboration with CHEST.6 This certificate program provides regional training options and longitudinal portfolio development. Other external certificates are also available to hospitalists.7,14,15

Most hospitalists are boarded by the American Board of Internal Medicine or the American Board of Family Medicine. These boards do not yet include certification of competency in POCUS. Other specialty boards, such as emergency medicine, include competency in POCUS. For emergency medicine, completion of an accredited residency training program and certification by the national board includes POCUS competency.

Internal Certificate

There are a few examples of successful local institutional programs that have provided internal certificates of competency.12,14 Competency assessments require significant resources including investment by both faculty and learners. Ongoing evaluation of competency should be based on quality assurance processes.

Credentialing and Privileging

The American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates in 1999 passed a resolution (AMA HR. 802) recommending hospitals follow specialty-specific guidelines for privileging decisions related to POCUS use.17 The resolution included a statement that, “ultrasound imaging is within the scope of practice of appropriately trained physicians.”

Some institutions have begun to rely on a combination of internal and external certificate programs to grant privileges to hospitalists.10 Although specific privileges for POCUS may not be required in some hospitals, some institutions may require certification of training and assessments prior to granting permission to use POCUS.

Hospitalist programs are encouraged to evaluate ongoing POCUS use by their providers after granting initial permission. If privileging is instituted by a hospital, hospitalists must play a significant role in determining the requirements for privileging and ongoing maintenance of skills.

Maintenance of Skills

All medical skills can decay with disuse, including those associated with POCUS.12,18 Thus, POCUS users should continue using POCUS regularly in clinical practice and participate in POCUS continuing medical education activities, ideally with ongoing assessments. Maintenance of skills may be confirmed through routine participation in a quality assurance program.

PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Use of POCUS in hospital medicine has unique considerations, and hospitalists should be integrally involved in decision making surrounding institutional POCUS program management. Appointing a dedicated POCUS director can help a program succeed.8

Equipment and Image Archiving

Several factors are important to consider when selecting an ultrasound machine: portability, screen size, and ease of use; integration with the electronic medical record and options for image archiving; manufacturer’s service plan, including technical and clinical support; and compliance with local infection control policies. The ability to easily archive and retrieve images is essential for quality assurance, continuing education, institutional quality improvement, documentation, and reimbursement. In certain scenarios, image archiving may not be possible (such as with personal handheld devices or in emergency situations) or necessary (such as with frequent serial examinations during fluid resuscitation). An image archive is ideally linked to reports, orders, and billing software.10,19 If such linkages are not feasible, parallel external storage that complies with regulatory standards (ie, HIPAA compliance) may be suitable.20

Documentation and Billing

Components of documentation include the indication and type of ultrasound examination performed, date and time of the examination, patient identifying information, name of provider(s) acquiring and interpreting the images, specific scanning protocols used, patient position, probe used, and findings. Documentation can occur through a standalone note or as part of another note, such as a progress note. Whenever possible, documentation should be timely to facilitate communication with other providers.

Billing is supported through the AMA Current Procedural Terminology codes for “focused” or “limited” ultrasound examinations (Appendix 9). The following three criteria must be satisfied for billing. First, images must be permanently stored. Specific requirements vary by insurance policy, though current practice suggests a minimum of one image demonstrating relevant anatomy and pathology for the ultrasound examination coded. For ultrasound-guided procedures that require needle insertion, images should be captured at the point of interest, and a procedure note should reflect that the needle was guided and visualized under ultrasound.21 Second, proper documentation must be entered in the medical record. Third, local institutional privileges for POCUS must be considered. Although privileges are not required to bill, some hospitals or payers may require them.

Quality Assurance

Published guidelines on quality assurance in POCUS are available from different specialty organizations, including emergency medicine, pediatric emergency medicine, critical care, anesthesiology, obstetrics, and cardiology.8,22–28 Quality assurance is aimed at ensuring that physicians maintain basic competency in using POCUS to influence bedside decisions.

Quality assurance should be carried out by an individual or committee with expertise in POCUS. Multidisciplinary QA programs in which hospital medicine providers are working collaboratively with other POCUS providers have been demonstrated to be highly effective.10 Oversight includes ensuring that providers using POCUS are appropriately trained,10,22,28 using the equipment correctly,8,26,28 and documenting properly. Some programs have implemented mechanisms to review and provide feedback on image acquisition, interpretation, and clinical integration.8,10 Other programs have compared POCUS findings with referral studies, such as comprehensive ultrasound examinations.

CONCLUSIONS

Practicing hospitalists must continue to collaborate with their institutions to build POCUS capabilities. In particular, they must work with their local privileging body to determine what credentials are required. The distinction between certificates of completion and certificates of competency, including whether those certificates are internal or external, is important in the credentialing process.

External certificates of competency are currently unavailable for most practicing hospitalists because ABIM certification does not include POCUS-related competencies. As internal medicine residency training programs begin to adopt POCUS training and certification into their educational curricula, we foresee a need to update the ABIM Policies and Procedures for Certification. Until then, we recommend that certificates of competency be defined and granted internally by local hospitalist groups.

Given the many advantages of POCUS over traditional tools, we anticipate its increasing implementation among hospitalists in the future. As with all medical technology, its role in clinical care should be continuously reexamined and redefined through health services research. Such information will be useful in developing practice guidelines, educational curricula, and training standards.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members that participated in the discussion and finalization of this position statement during the Point-of-care Ultrasound Faculty Retreat at the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference: Saaid Abdel-Ghani, Brandon Boesch, Joel Cho, Ria Dancel, Renee Dversdal, Ricardo Franco-Sadud, Benjamin Galen, Trevor P. Jensen, Mohit Jindal, Gordon Johnson, Linda M. Kurian, Gigi Liu, Charles M. LoPresti, Brian P. Lucas, Venkat Kalidindi, Benji Matthews, Anna Maw, Gregory Mints, Kreegan Reierson, Gerard Salame, Richard Schildhouse, Daniel Schnobrich, Nilam Soni, Kirk Spencer, Hiromizu Takahashi, David M. Tierney, Tanping Wong, and Toru Yamada.

Many hospitalists incorporate point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) into their daily practice because it adds value to their bedside evaluation of patients. However, standards for training and assessing hospitalists in POCUS have not yet been established. Other acute care specialties, including emergency medicine and critical care medicine, have already incorporated POCUS into their graduate medical education training programs, but most internal medicine residency programs are only beginning to provide POCUS training.1

Several features distinguish POCUS from comprehensive ultrasound examinations. First, POCUS is designed to answer focused questions, whereas comprehensive ultrasound examinations evaluate all organs in an anatomical region; for example, an abdominal POCUS exam may evaluate only for presence or absence of intraperitoneal free fluid, whereas a comprehensive examination of the right upper quadrant will evaluate the liver, gallbladder, and biliary ducts. Second, POCUS examinations are generally performed by the same clinician who generates the relevant clinical question to answer with POCUS and ultimately integrates the findings into the patient’s care.2 By contrast, comprehensive ultrasound examinations involve multiple providers and steps: a clinician generates a relevant clinical question and requests an ultrasound examination that is acquired by a sonographer, interpreted by a radiologist, and reported back to the requesting clinician. Third, POCUS is often used to evaluate multiple body systems. For example, to evaluate a patient with undifferentiated hypotension, a multisystem POCUS examination of the heart, inferior vena cava, lungs, abdomen, and lower extremity veins is typically performed. Finally, POCUS examinations can be performed serially to investigate changes in clinical status or evaluate response to therapy, such as monitoring the heart, lungs, and inferior vena cava during fluid resuscitation.

The purpose of this position statement is to inform a broad audience about how hospitalists are using diagnostic and procedural applications of POCUS. This position statement does not mandate that hospitalists use POCUS. Rather, it is intended to provide guidance on the safe and effective use of POCUS by the hospitalists who use it and the administrators who oversee its use. We discuss POCUS (1) applications, (2) training, (3) assessments, and (4) program management. This position statement was reviewed and approved by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) Executive Committee in March 2018.

APPLICATIONS

As outlined in our earlier position statements,3,4 ultrasound guidance lowers complication rates and increases success rates of invasive bedside procedures. Diagnostic POCUS can guide clinical decision making prior to bedside procedures. For instance, hospitalists may use POCUS to assess the size and character of a pleural effusion to help determine the most appropriate management strategy: observation, medical treatment, thoracentesis, chest tube placement, or surgical therapy. Furthermore, diagnostic POCUS can be used to rapidly assess for immediate postprocedural complications, such as pneumothorax, or if the patient develops new symptoms.

TRAINING

Basic Knowledge

Basic knowledge includes fundamentals of ultrasound physics; safety;4 anatomy; physiology; and device operation, including maintenance and cleaning. Basic knowledge can be taught by multiple methods, including live or recorded lectures, online modules, or directed readings.

Image Acquisition

Training should occur across multiple types of patients (eg, obese, cachectic, postsurgical) and clinical settings (eg, intensive care unit, general medicine wards, emergency department) when available. Training is largely hands-on because the relevant skills involve integration of 3D anatomy with spatial manipulation, hand-eye coordination, and fine motor movements. Virtual reality ultrasound simulators may accelerate mastery, particularly for cardiac image acquisition, and expose learners to standardized sets of pathologic findings. Real-time bedside feedback on image acquisition is ideal because understanding how ultrasound probe manipulation affects the images acquired is essential to learning.

Image Interpretation

Training in image interpretation relies on visual pattern recognition of normal and abnormal findings. Therefore, the normal to abnormal spectrum should be broad, and learners should maintain a log of what abnormalities have been identified. Giving real-time feedback at the bedside is ideal because of the connection between image acquisition and interpretation. Image interpretation can be taught through didactic sessions, image review sessions, or review of teaching files with annotated images.

Clinical Integration

Learners must interpret and integrate image findings with other clinical data considering the image quality, patient characteristics, and changing physiology. Clinical integration should be taught by instructors that share similar clinical knowledge as learners. Although sonographers are well suited to teach image acquisition, they should not be the sole instructors to teach hospitalists how to integrate ultrasound findings in clinical decision making. Likewise, emphasis should be placed on the appropriate use of POCUS within a provider’s skill set. Learners must appreciate the clinical significance of POCUS findings, including recognition of incidental findings that may require further workup. Supplemental training in clinical integration can occur through didactics that include complex patient scenarios.

Pathways

Clinical competency can be achieved with training adherent to five criteria. First, the training environment should be similar to where the trainee will practice. Second, training and feedback should occur in real time. Third, specific applications should be taught rather than broad training in “hospitalist POCUS.” Each application requires unique skills and knowledge, including image acquisition pitfalls and artifacts. Fourth, clinical competence must be achieved and demonstrated; it is not necessarily gained through experience. Fifth, once competency is achieved, continued education and feedback are necessary to ensure it is maintained.

Residency-based POCUS training pathways can best fulfill these criteria. They may eventually become commonplace, but until then alternative pathways must exist for hospitalist providers who are already in practice. There are three important attributes of such pathways. First, administrators’ expectations about learners’ clinical productivity must be realistically, but only temporarily, relaxed; otherwise, competing demands on time will likely overwhelm learners and subvert training. Second, training should begin through a local or national hands-on training program. The SHM POCUS certificate program consolidates training for common diagnostic POCUS applications for hospitalists.6 Other medical societies offer training for their respective clinical specialties.7 Third, once basic POCUS training has begun, longitudinal training should continue ideally with a local hospitalist POCUS expert.

In some settings, a subgroup of hospitalists may not desire, or be able to achieve, competency in the manual skills of POCUS image acquisition. Nevertheless, hospitalists may still find value in understanding POCUS nomenclature, image pattern recognition, and the evidence and pitfalls behind clinical integration of specific POCUS findings. This subset of POCUS skills allows hospitalists to communicate effectively with and understand the clinical decisions made by their colleagues who are competent in POCUS use.

The minimal skills a hospitalist should possess to serve as a POCUS trainer include proficiency of basic knowledge, image acquisition, image interpretation, and clinical integration of the POCUS applications being taught; effectiveness as a hands-on instructor to teach image acquisition skills; and an in-depth understanding of common POCUS pitfalls and limitations.

ASSESSMENTS

Assessment methods for POCUS can include the following: knowledge-based questions, image acquisition using task-specific checklists on human or simulation models, image interpretation using a series of videos or still images with normal and abnormal findings, clinical integration using “next best step” in a multiple choice format with POCUS images, and simulation-based clinical scenarios. Assessment methods should be aligned with local availability of resources and trainers.

Basic Knowledge

Basic knowledge can be assessed via multiple choice questions assessing knowledge of ultrasound physics, image optimization, relevant anatomy, and limitations of POCUS imaging. Basic knowledge lies primarily in the cognitive domain and does not assess manual skills.

Image Acquisition

Image acquisition can be assessed by observation and rating of image quality. Where resources allow, assessment of image acquisition is likely best done through a combination of developing an image portfolio with a minimum number of high quality images, plus direct observation of image acquisition by an expert. Various programs have utilized minimum numbers of images acquired to help define competence with image acquisition skills.6–8 Although minimums may be a necessary step to gain competence, using them as a sole means to determine competence does not account for variable learning curves.9 As with other manual skills in hospital medicine, such as ultrasound-guided bedside procedures, minimum numbers are best used as a starting point for assessments.3,10 In this regard, portfolio development with meticulous attention to the gain, depth, and proper tomographic plane of images can monitor a hospitalist’s progress toward competence by providing objective assessments and feedback. Simulation may also be used as it allows assessment of image acquisition skills and an opportunity to provide real-time feedback, similar to direct observation but without actual patients.

Image Interpretation

Image interpretation is best assessed by an expert observing the learner at bedside; however, when bedside assessment is not possible, image interpretation skills may be assessed using multiple choice or free text interpretation of archived ultrasound images with normal and abnormal findings. This is often incorporated into the portfolio development portion of a training program, as learners can submit their image interpretation along with the video clip. Both normal and abnormal images can be used to assess anatomic recognition and interpretation. Emphasis should be placed on determining when an image is suboptimal for diagnosis (eg, incomplete exam or poor-quality images). Quality assurance programs should incorporate structured feedback sessions.

Clinical Integration

Assessment of clinical integration can be completed through case scenarios that assess knowledge, interpretation of images, and integration of findings into clinical decision making, which is often delivered via a computer-based assessment. Assessments should combine specific POCUS applications to evaluate common clinical problems in hospital medicine, such as undifferentiated hypotension and dyspnea. High-fidelity simulators can be used to blend clinical case scenarios with image acquisition, image interpretation, and clinical integration. When feasible, comprehensive feedback on how providers acquire, interpret, and apply ultrasound at the bedside is likely the best mechanism to assess clinical integration. This process can be done with a hospitalist’s own patients.

General Assessment

A general assessment that includes a summative knowledge and hands-on skills assessment using task-specific checklists can be performed upon completion of training. A high-fidelity simulator with dynamic or virtual anatomy can provide reproducible standardized assessments with variation in the type and difficulty of cases. When available, we encourage the use of dynamic assessments on actual patients that have both normal and abnormal ultrasound findings because simulated patient scenarios have limitations, even with the use of high-fidelity simulators. Programs are recommended to use formative and summative assessments for evaluation. Quantitative scoring systems using checklists are likely the best framework.11,12

CERTIFICATES AND CERTIFICATION

A certificate of completion is proof of a provider’s participation in an educational activity; it does not equate with competency, though it may be a step toward it. Most POCUS training workshops and short courses provide certificates of completion. Certification of competency is an attestation of a hospitalist’s basic competence within a defined scope of practice (Table 2).13 However, without longitudinal supervision and feedback, skills can decay; therefore, we recommend a longitudinal training program that provides mentored feedback and incorporates periodic competency assessments. At present, no national board certification in POCUS is available to grant external certification of competency for hospitalists.

External Certificate

Certificates of completion can be external through a national organization. An external certificate of completion designed for hospitalists includes the POCUS Certificate of Completion offered by SHM in collaboration with CHEST.6 This certificate program provides regional training options and longitudinal portfolio development. Other external certificates are also available to hospitalists.7,14,15

Most hospitalists are boarded by the American Board of Internal Medicine or the American Board of Family Medicine. These boards do not yet include certification of competency in POCUS. Other specialty boards, such as emergency medicine, include competency in POCUS. For emergency medicine, completion of an accredited residency training program and certification by the national board includes POCUS competency.

Internal Certificate

There are a few examples of successful local institutional programs that have provided internal certificates of competency.12,14 Competency assessments require significant resources including investment by both faculty and learners. Ongoing evaluation of competency should be based on quality assurance processes.

Credentialing and Privileging

The American Medical Association (AMA) House of Delegates in 1999 passed a resolution (AMA HR. 802) recommending hospitals follow specialty-specific guidelines for privileging decisions related to POCUS use.17 The resolution included a statement that, “ultrasound imaging is within the scope of practice of appropriately trained physicians.”

Some institutions have begun to rely on a combination of internal and external certificate programs to grant privileges to hospitalists.10 Although specific privileges for POCUS may not be required in some hospitals, some institutions may require certification of training and assessments prior to granting permission to use POCUS.

Hospitalist programs are encouraged to evaluate ongoing POCUS use by their providers after granting initial permission. If privileging is instituted by a hospital, hospitalists must play a significant role in determining the requirements for privileging and ongoing maintenance of skills.

Maintenance of Skills

All medical skills can decay with disuse, including those associated with POCUS.12,18 Thus, POCUS users should continue using POCUS regularly in clinical practice and participate in POCUS continuing medical education activities, ideally with ongoing assessments. Maintenance of skills may be confirmed through routine participation in a quality assurance program.

PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

Use of POCUS in hospital medicine has unique considerations, and hospitalists should be integrally involved in decision making surrounding institutional POCUS program management. Appointing a dedicated POCUS director can help a program succeed.8

Equipment and Image Archiving

Several factors are important to consider when selecting an ultrasound machine: portability, screen size, and ease of use; integration with the electronic medical record and options for image archiving; manufacturer’s service plan, including technical and clinical support; and compliance with local infection control policies. The ability to easily archive and retrieve images is essential for quality assurance, continuing education, institutional quality improvement, documentation, and reimbursement. In certain scenarios, image archiving may not be possible (such as with personal handheld devices or in emergency situations) or necessary (such as with frequent serial examinations during fluid resuscitation). An image archive is ideally linked to reports, orders, and billing software.10,19 If such linkages are not feasible, parallel external storage that complies with regulatory standards (ie, HIPAA compliance) may be suitable.20

Documentation and Billing

Components of documentation include the indication and type of ultrasound examination performed, date and time of the examination, patient identifying information, name of provider(s) acquiring and interpreting the images, specific scanning protocols used, patient position, probe used, and findings. Documentation can occur through a standalone note or as part of another note, such as a progress note. Whenever possible, documentation should be timely to facilitate communication with other providers.

Billing is supported through the AMA Current Procedural Terminology codes for “focused” or “limited” ultrasound examinations (Appendix 9). The following three criteria must be satisfied for billing. First, images must be permanently stored. Specific requirements vary by insurance policy, though current practice suggests a minimum of one image demonstrating relevant anatomy and pathology for the ultrasound examination coded. For ultrasound-guided procedures that require needle insertion, images should be captured at the point of interest, and a procedure note should reflect that the needle was guided and visualized under ultrasound.21 Second, proper documentation must be entered in the medical record. Third, local institutional privileges for POCUS must be considered. Although privileges are not required to bill, some hospitals or payers may require them.

Quality Assurance

Published guidelines on quality assurance in POCUS are available from different specialty organizations, including emergency medicine, pediatric emergency medicine, critical care, anesthesiology, obstetrics, and cardiology.8,22–28 Quality assurance is aimed at ensuring that physicians maintain basic competency in using POCUS to influence bedside decisions.

Quality assurance should be carried out by an individual or committee with expertise in POCUS. Multidisciplinary QA programs in which hospital medicine providers are working collaboratively with other POCUS providers have been demonstrated to be highly effective.10 Oversight includes ensuring that providers using POCUS are appropriately trained,10,22,28 using the equipment correctly,8,26,28 and documenting properly. Some programs have implemented mechanisms to review and provide feedback on image acquisition, interpretation, and clinical integration.8,10 Other programs have compared POCUS findings with referral studies, such as comprehensive ultrasound examinations.

CONCLUSIONS

Practicing hospitalists must continue to collaborate with their institutions to build POCUS capabilities. In particular, they must work with their local privileging body to determine what credentials are required. The distinction between certificates of completion and certificates of competency, including whether those certificates are internal or external, is important in the credentialing process.

External certificates of competency are currently unavailable for most practicing hospitalists because ABIM certification does not include POCUS-related competencies. As internal medicine residency training programs begin to adopt POCUS training and certification into their educational curricula, we foresee a need to update the ABIM Policies and Procedures for Certification. Until then, we recommend that certificates of competency be defined and granted internally by local hospitalist groups.

Given the many advantages of POCUS over traditional tools, we anticipate its increasing implementation among hospitalists in the future. As with all medical technology, its role in clinical care should be continuously reexamined and redefined through health services research. Such information will be useful in developing practice guidelines, educational curricula, and training standards.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all members that participated in the discussion and finalization of this position statement during the Point-of-care Ultrasound Faculty Retreat at the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference: Saaid Abdel-Ghani, Brandon Boesch, Joel Cho, Ria Dancel, Renee Dversdal, Ricardo Franco-Sadud, Benjamin Galen, Trevor P. Jensen, Mohit Jindal, Gordon Johnson, Linda M. Kurian, Gigi Liu, Charles M. LoPresti, Brian P. Lucas, Venkat Kalidindi, Benji Matthews, Anna Maw, Gregory Mints, Kreegan Reierson, Gerard Salame, Richard Schildhouse, Daniel Schnobrich, Nilam Soni, Kirk Spencer, Hiromizu Takahashi, David M. Tierney, Tanping Wong, and Toru Yamada.

1. Schnobrich DJ, Mathews BK, Trappey BE, Muthyala BK, Olson APJ. Entrusting internal medicine residents to use point of care ultrasound: Towards improved assessment and supervision. Med Teach. 2018:1-6. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457210.

2. Soni NJ, Lucas BP. Diagnostic point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):120-124. doi:10.1002/jhm.2285.

3. Lucas BP, Tierney DM, Jensen TP, et al. Credentialing of hospitalists in ultrasound-guided bedside procedures: a position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):117-125. doi:10.12788/jhm.2917.

4. Dancel R, Schnobrich D, Puri N, et al. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for adult thoracentesis: a position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):126-135. doi:10.12788/jhm.2940.

5. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, The Council. Implementation of the Principle of as Low as Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) for Medical and Dental Personnel.; 1990.

6. Society of Hospital Medicine. Point of Care Ultrasound course: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/clinical-topics/ultrasonography-cert/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

7. Critical Care Ultrasonography Certificate of Completion Program. CHEST. American College of Chest Physicians. http://www.chestnet.org/Education/Advanced-Clinical-Training/Certificate-of-Completion-Program/Critical-Care-Ultrasonography. Accessed February 6, 2018.

8. American College of Emergency Physicians Policy Statement: Emergency Ultrasound Guidelines. 2016. https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/ACEP-Ultrasound-Guidelines/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

9. Blehar DJ, Barton B, Gaspari RJ. Learning curves in emergency ultrasound education. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(5):574-582. doi:10.1111/acem.12653.

10. Mathews BK, Zwank M. Hospital medicine point of care ultrasound credentialing: an example protocol. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):767-772. doi:10.12788/jhm.2809.

11. Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Balachandran JS, Wayne DB. Use of simulation-based mastery learning to improve the quality of central venous catheter placement in a medical intensive care unit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):397-403. doi:10.1002/jhm.468.

12. Mathews BK, Reierson K, Vuong K, et al. The design and evaluation of the Comprehensive Hospitalist Assessment and Mentorship with Portfolios (CHAMP) ultrasound program. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):544-550. doi:10.12788/jhm.2938.

13. Soni NJ, Tierney DM, Jensen TP, Lucas BP. Certification of point-of-care ultrasound competency. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):775-776. doi:10.12788/jhm.2812.

14. Ultrasound Certification for Physicians. Alliance for Physician Certification and Advancement. APCA. https://apca.org/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

15. National Board of Echocardiography, Inc. https://www.echoboards.org/EchoBoards/News/2019_Adult_Critical_Care_Echocardiography_Exam.aspx. Accessed June 18, 2018.

16. Tierney DM. Internal Medicine Bedside Ultrasound Program (IMBUS). Abbott Northwestern. http://imbus.anwresidency.com/index.html. Accessed February 6, 2018.

17. American Medical Association House of Delegates Resolution H-230.960: Privileging for Ultrasound Imaging. Resolution 802. Policy Finder Website. http://search0.ama-assn.org/search/pfonline. Published 1999. Accessed February 18, 2018.

18. Kelm D, Ratelle J, Azeem N, et al. Longitudinal ultrasound curriculum improves long-term retention among internal medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):454-457. doi:10.4300/JGME-14-00284.1.

19. Flannigan MJ, Adhikari S. Point-of-care ultrasound work flow innovation: impact on documentation and billing. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(12):2467-2474. doi:10.1002/jum.14284.

20. Emergency Ultrasound: Workflow White Paper. https://www.acep.org/uploadedFiles/ACEP/memberCenter/SectionsofMembership/ultra/Workflow%20White%20Paper.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed February 18, 2018.

21. Ultrasound Coding and Reimbursement Document 2009. Emergency Ultrasound Section. American College of Emergency Physicians. http://emergencyultrasoundteaching.com/assets/2009_coding_update.pdf. Published 2009. Accessed February 18, 2018.

22. Mayo PH, Beaulieu Y, Doelken P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians/La Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest. 2009;135(4):1050-1060. doi:10.1378/chest.08-2305.

23. Frankel HL, Kirkpatrick AW, Elbarbary M, et al. Guidelines for the appropriate use of bedside general and cardiac ultrasonography in the evaluation of critically ill patients-part I: general ultrasonography. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(11):2479-2502. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000001216.

24. Levitov A, Frankel HL, Blaivas M, et al. Guidelines for the appropriate use of bedside general and cardiac ultrasonography in the evaluation of critically ill patients-part ii: cardiac ultrasonography. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(6):1206-1227. doi:10.1097/ccm.0000000000001847.

25. ACR–ACOG–AIUM–SRU Practice Parameter for the Performance of Obstetrical Ultrasound. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/us-ob.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed February 18, 2018.

26. AIUM practice guideline for documentation of an ultrasound examination. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33(6):1098-1102. doi:10.7863/ultra.33.6.1098.

27. Marin JR, Lewiss RE. Point-of-care ultrasonography by pediatric emergency medicine physicians. Pediatrics. 2015;135(4):e1113-e1122. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0343.

28. Spencer KT, Kimura BJ, Korcarz CE, Pellikka PA, Rahko PS, Siegel RJ. Focused cardiac ultrasound: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(6):567-581. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2013.04.001.

1. Schnobrich DJ, Mathews BK, Trappey BE, Muthyala BK, Olson APJ. Entrusting internal medicine residents to use point of care ultrasound: Towards improved assessment and supervision. Med Teach. 2018:1-6. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1457210.

2. Soni NJ, Lucas BP. Diagnostic point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(2):120-124. doi:10.1002/jhm.2285.

3. Lucas BP, Tierney DM, Jensen TP, et al. Credentialing of hospitalists in ultrasound-guided bedside procedures: a position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):117-125. doi:10.12788/jhm.2917.

4. Dancel R, Schnobrich D, Puri N, et al. Recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for adult thoracentesis: a position statement of the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(2):126-135. doi:10.12788/jhm.2940.

5. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, The Council. Implementation of the Principle of as Low as Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) for Medical and Dental Personnel.; 1990.

6. Society of Hospital Medicine. Point of Care Ultrasound course: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/clinical-topics/ultrasonography-cert/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

7. Critical Care Ultrasonography Certificate of Completion Program. CHEST. American College of Chest Physicians. http://www.chestnet.org/Education/Advanced-Clinical-Training/Certificate-of-Completion-Program/Critical-Care-Ultrasonography. Accessed February 6, 2018.

8. American College of Emergency Physicians Policy Statement: Emergency Ultrasound Guidelines. 2016. https://www.acep.org/Clinical---Practice-Management/ACEP-Ultrasound-Guidelines/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

9. Blehar DJ, Barton B, Gaspari RJ. Learning curves in emergency ultrasound education. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(5):574-582. doi:10.1111/acem.12653.

10. Mathews BK, Zwank M. Hospital medicine point of care ultrasound credentialing: an example protocol. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):767-772. doi:10.12788/jhm.2809.

11. Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Balachandran JS, Wayne DB. Use of simulation-based mastery learning to improve the quality of central venous catheter placement in a medical intensive care unit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):397-403. doi:10.1002/jhm.468.

12. Mathews BK, Reierson K, Vuong K, et al. The design and evaluation of the Comprehensive Hospitalist Assessment and Mentorship with Portfolios (CHAMP) ultrasound program. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(8):544-550. doi:10.12788/jhm.2938.

13. Soni NJ, Tierney DM, Jensen TP, Lucas BP. Certification of point-of-care ultrasound competency. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(9):775-776. doi:10.12788/jhm.2812.

14. Ultrasound Certification for Physicians. Alliance for Physician Certification and Advancement. APCA. https://apca.org/. Accessed February 6, 2018.

15. National Board of Echocardiography, Inc. https://www.echoboards.org/EchoBoards/News/2019_Adult_Critical_Care_Echocardiography_Exam.aspx. Accessed June 18, 2018.

16. Tierney DM. Internal Medicine Bedside Ultrasound Program (IMBUS). Abbott Northwestern. http://imbus.anwresidency.com/index.html. Accessed February 6, 2018.