User login

Society of Hospital Medicine Position on the American Board of Pediatrics Response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition

The first Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowships in the United States were established in 2003;1 and since then, the field has expanded and matured dramatically. This growth, accompanied by greater definition of the role and recommended competencies of pediatric hospitalists,2 culminated in the submission of a petition to the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) in August 2014 to consider recognition of PHM as a new pediatric subspecialty.3 After an 18-month iterative process requiring extensive input from the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, ABP subcommittees, the Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs, the Association of Pediatric Program Directors, and other prominent pediatric professional societies, the ABP voted in December 2015 to recommend that the American Board of Medical Subspecialties (ABMS) recognize PHM as a new subspecialty.3

The ABP subsequently announced three pathways for board certification in PHM:

- Training pathway for those completing an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited two-year PHM fellowship program;

- Practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM for four years prior to exam dates (in 2019, 2021, and 2023), initially described as “direct patient care of hospitalized children ≥25% full-time equivalent (FTE) defined as ≥450-500 hours per year every year for the preceding four years”;4

- Combined pathway for those completing less than two years of fellowship, who would be required to complete two years of practice experience that satisfy the same criteria as each year of the practice pathway.5

While the training pathway met near-uniform acceptance, concerns were raised through the American Academy of Pediatrics Section of Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) Listserv regarding the practice pathway, and by extension, the combined pathway. Specifically, language describing the necessary characteristics of acceptable PHM practice was felt to be vague and not transparent. Listserv posts also raised concerns regarding the potential exclusion of “niche” practices such as subspecialty hospitalists and newborn hospitalists. As applicants in the practice pathway began to receive denials, opinions voiced in listserv posts were increasingly critical of the ABP’s lack of transparency regarding the specific criteria adjudicating applications.

ORIGIN OF THE PHM PETITION

A group of hospitalists, led by Dr. David Skey, a pediatric hospitalist at Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital in Orlando, Florida, created a petition which was submitted to the ABP on August 6, 2019, and raised the following issues:

- “A perception of unfairness/bias in the practice pathway criteria and the way these criteria have been applied.

- Denials based on gaps in employment without reasonable consideration of mitigating factors.

- Lack of transparency, accountability, and responsiveness from the ABP.”6

The petition, posted on the AAP SOHM listserv and signed by 1,479 individuals,7 raised concerns of anecdotal evidence that the practice pathway criteria disproportionately disadvantaged women, although intentional bias was not suspected by the signers of the letter. The petition’s signers submitted the following demands to the ABP:

- “Facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias is present or perform this analysis internally and release the findings publicly.

- Revise the practice pathway criteria to be more inclusive of applicants with interrupted practice and varied clinical experience, to include clear-cut parameters rather than considering these applications on a closed-door ‘case-by-case basis...at the discretion of the ABP’.

- Clarify the appeals process and improve responsiveness to appeals and inquiries regarding denials.

- Provide a formal response to this petition letter through the PHM ListServ and/or the ABP website within one week of receiving the signed petition.”6

THE ABP RESPONSE TO THE PHM PETITION

A formal response to the petition was released on the AAP SOHM Listserv on August 29, 2019, to address the concerns raised and is published in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.4 In response to the allegation of gender bias, the ABP maintained that the data did not support this, as the denial rate for females (4.0%) was not significantly different than that for males (3.7%). The response acknowledged that once clear-cut criteria were decided upon to augment the general practice pathway criteria published at the outset, these criteria should have been disseminated. The ABP maintained, however, that these criteria, once established, were used consistently in adjudicating all applications. To clarify and simplify the eligibility criteria, the percentage of the full-time equivalent and practice interruption criteria were removed, as the work-hours criteria (direct patient care of hospitalized children ≥450-500 hours per year every year for the preceding four years)8 were deemed sufficient to ensure adequate clinical participation.

SHM’S POSITION REGARDING THE PHM PETITION AND ABP RESPONSE

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), through pediatric hospitalists and pediatricians on its Board, committees, and the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group, has followed with great interest the public debate surrounding the PHM certification process and the subsequent PHM petition to the ABP. The ABP responded swiftly and with full transparency to the petition, and SHM supports these efforts by the ABP to provide a timely, honest, data-driven response to the concerns raised by the PHM petition. SHM recognizes that the mission of the ABP is to provide the public with confidence that physicians with ABP board certifications meet appropriate “standards of excellence”. While the revisions implemented by the ABP in its response still may not satisfy the concerns of all members of the PHM community, SHM recognizes that the revised requirements remain true to the mission of the ABP.

SHM applauds the authors and signatories of the PHM petition for bravely raising their concerns of gender bias and lack of transparency. The response of the ABP to this petition by further improving transparency serves as an example of continuous improvement in collaborative practice to all medical specialty boards.

While SHM supports the ABP response to the PHM petition, it is clear that excellent physicians caring for hospitalized children will be unable to achieve PHM board certification for a variety of reasons. For these physicians who are not PHM board certified as pediatric hospitalists by the ABP, SHM supports providing these physicians with recognition as hospitalists. These include “niche” hospitalists, such as newborn hospitalists, subacute hospitalists, and subspecialty hospitalists. SHM will also continue to support and recognize community-based hospitalists, family medicine-trained hospitalists, and Med-Peds hospitalists whose practice may not comply with criteria laid out by the ABP. For these physicians, receiving Fellow designation through SHM, a merit-based distinction requiring demonstration of clinical excellence and commitment to hospital medicine, is another route whereby physicians can achieve designation as a hospitalist.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR PEDIATRIC HOSPITALISTS

SHM supports future efforts by the ABP to be vigilant for bias of any sort in the certification process. Other future considerations for the PHM community include the possibility of a focused practice pathway in hospital medicine (FPHM) for pediatrics as is currently jointly offered by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM). This maintenance of certification program is a variation of internal medicine or family medicine recertification, not a subspecialty, but allows physicians practicing primarily in inpatient settings to focus continuing education efforts on skills and attitudes needed for inpatient practice.9 While this possibility was discounted by the ABP in the past based on initially low numbers of physicians choosing this pathway, this pathway has grown from initially attracting 150 internal medicine applicants yearly to 265 in 2015.10 The ABMS approved the ABIM/ABFM FPHM as its first approved designation in March 2017 after more than 2,500 physicians earned this designation.11 Of the >2,800 pediatric residency graduates (not including combined programs) each year, 10% report planning on becoming pediatric hospitalists,12 and currently only 72-74 fellows graduate from PHM fellowships yearly.13 FPHM for pediatric hospital medicine would provide focused maintenance of certification and hospitalist designation for those who cannot match to fellowship programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the input and support from the Executive Council of the Society of Hospital Medicine Pediatric Special Interest Group in writing this statement.

Disclosures

Dr. Chang served as an author of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition to the American Board of Pediatrics for Subspecialty Certification. Drs. Hopkins, Rehm, Gage, and Shen have nothing to disclose.

1. Freed GL, Dunham KM, Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of P. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):157-163. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.409.

2. Stucky ER, Maniscalco J, Ottolini MC, et al. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies Supplement: a Framework for Curriculum Development by the Society of Hospital Medicine with acknowledgement to pediatric hospitalists from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Academic Pediatric Association. J Hosp Med. 2010;5 Suppl 2:i-xv, 1-114. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.776.

3. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric Hospital Medicine: A Proposed New Subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

4. Nichols DG WS. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):586-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3322.

5. Pediatric hospital medicine certification. American Board of Pediatrics. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification#training. Accessed 3 September, 2019.

6. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC. https://www.phmpetition.com/. Accessed 3 September, 2019.

7. Skey D. Petition Update. In: AAP SOHM Listserv: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2019.

8. The American Board of Pediatrics Response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition. The American Board of Pediatrics. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

9. Focused practice in hospital medicine. American Board of Internal Medicine. https://www.abim.org/maintenance-of-certification/moc-requirements/focused-practice-hospital-medicine.aspx. Published 2019 Accessed September 4, 2019.

10. Butterfield S. Following the focused practice pathway. American College of Physicians. Your career Web site. https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2016/09/focused-practice-hospital-medicine.htm. Published 2016. Accessed September 4, 2019.

11. American Board of Medical Specialties Announces New, Focused Practice Designation [press release]. American Board of Medical Specialties, 14 Mar 2017.

12. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating Pediatric Residents Entering the Hospital Medicine Workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

13. PHM Fellowship Programs. PHMFellows.org. http://phmfellows.org/phm-programs/. Published 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

The first Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowships in the United States were established in 2003;1 and since then, the field has expanded and matured dramatically. This growth, accompanied by greater definition of the role and recommended competencies of pediatric hospitalists,2 culminated in the submission of a petition to the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) in August 2014 to consider recognition of PHM as a new pediatric subspecialty.3 After an 18-month iterative process requiring extensive input from the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, ABP subcommittees, the Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs, the Association of Pediatric Program Directors, and other prominent pediatric professional societies, the ABP voted in December 2015 to recommend that the American Board of Medical Subspecialties (ABMS) recognize PHM as a new subspecialty.3

The ABP subsequently announced three pathways for board certification in PHM:

- Training pathway for those completing an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited two-year PHM fellowship program;

- Practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM for four years prior to exam dates (in 2019, 2021, and 2023), initially described as “direct patient care of hospitalized children ≥25% full-time equivalent (FTE) defined as ≥450-500 hours per year every year for the preceding four years”;4

- Combined pathway for those completing less than two years of fellowship, who would be required to complete two years of practice experience that satisfy the same criteria as each year of the practice pathway.5

While the training pathway met near-uniform acceptance, concerns were raised through the American Academy of Pediatrics Section of Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) Listserv regarding the practice pathway, and by extension, the combined pathway. Specifically, language describing the necessary characteristics of acceptable PHM practice was felt to be vague and not transparent. Listserv posts also raised concerns regarding the potential exclusion of “niche” practices such as subspecialty hospitalists and newborn hospitalists. As applicants in the practice pathway began to receive denials, opinions voiced in listserv posts were increasingly critical of the ABP’s lack of transparency regarding the specific criteria adjudicating applications.

ORIGIN OF THE PHM PETITION

A group of hospitalists, led by Dr. David Skey, a pediatric hospitalist at Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital in Orlando, Florida, created a petition which was submitted to the ABP on August 6, 2019, and raised the following issues:

- “A perception of unfairness/bias in the practice pathway criteria and the way these criteria have been applied.

- Denials based on gaps in employment without reasonable consideration of mitigating factors.

- Lack of transparency, accountability, and responsiveness from the ABP.”6

The petition, posted on the AAP SOHM listserv and signed by 1,479 individuals,7 raised concerns of anecdotal evidence that the practice pathway criteria disproportionately disadvantaged women, although intentional bias was not suspected by the signers of the letter. The petition’s signers submitted the following demands to the ABP:

- “Facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias is present or perform this analysis internally and release the findings publicly.

- Revise the practice pathway criteria to be more inclusive of applicants with interrupted practice and varied clinical experience, to include clear-cut parameters rather than considering these applications on a closed-door ‘case-by-case basis...at the discretion of the ABP’.

- Clarify the appeals process and improve responsiveness to appeals and inquiries regarding denials.

- Provide a formal response to this petition letter through the PHM ListServ and/or the ABP website within one week of receiving the signed petition.”6

THE ABP RESPONSE TO THE PHM PETITION

A formal response to the petition was released on the AAP SOHM Listserv on August 29, 2019, to address the concerns raised and is published in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.4 In response to the allegation of gender bias, the ABP maintained that the data did not support this, as the denial rate for females (4.0%) was not significantly different than that for males (3.7%). The response acknowledged that once clear-cut criteria were decided upon to augment the general practice pathway criteria published at the outset, these criteria should have been disseminated. The ABP maintained, however, that these criteria, once established, were used consistently in adjudicating all applications. To clarify and simplify the eligibility criteria, the percentage of the full-time equivalent and practice interruption criteria were removed, as the work-hours criteria (direct patient care of hospitalized children ≥450-500 hours per year every year for the preceding four years)8 were deemed sufficient to ensure adequate clinical participation.

SHM’S POSITION REGARDING THE PHM PETITION AND ABP RESPONSE

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), through pediatric hospitalists and pediatricians on its Board, committees, and the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group, has followed with great interest the public debate surrounding the PHM certification process and the subsequent PHM petition to the ABP. The ABP responded swiftly and with full transparency to the petition, and SHM supports these efforts by the ABP to provide a timely, honest, data-driven response to the concerns raised by the PHM petition. SHM recognizes that the mission of the ABP is to provide the public with confidence that physicians with ABP board certifications meet appropriate “standards of excellence”. While the revisions implemented by the ABP in its response still may not satisfy the concerns of all members of the PHM community, SHM recognizes that the revised requirements remain true to the mission of the ABP.

SHM applauds the authors and signatories of the PHM petition for bravely raising their concerns of gender bias and lack of transparency. The response of the ABP to this petition by further improving transparency serves as an example of continuous improvement in collaborative practice to all medical specialty boards.

While SHM supports the ABP response to the PHM petition, it is clear that excellent physicians caring for hospitalized children will be unable to achieve PHM board certification for a variety of reasons. For these physicians who are not PHM board certified as pediatric hospitalists by the ABP, SHM supports providing these physicians with recognition as hospitalists. These include “niche” hospitalists, such as newborn hospitalists, subacute hospitalists, and subspecialty hospitalists. SHM will also continue to support and recognize community-based hospitalists, family medicine-trained hospitalists, and Med-Peds hospitalists whose practice may not comply with criteria laid out by the ABP. For these physicians, receiving Fellow designation through SHM, a merit-based distinction requiring demonstration of clinical excellence and commitment to hospital medicine, is another route whereby physicians can achieve designation as a hospitalist.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR PEDIATRIC HOSPITALISTS

SHM supports future efforts by the ABP to be vigilant for bias of any sort in the certification process. Other future considerations for the PHM community include the possibility of a focused practice pathway in hospital medicine (FPHM) for pediatrics as is currently jointly offered by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM). This maintenance of certification program is a variation of internal medicine or family medicine recertification, not a subspecialty, but allows physicians practicing primarily in inpatient settings to focus continuing education efforts on skills and attitudes needed for inpatient practice.9 While this possibility was discounted by the ABP in the past based on initially low numbers of physicians choosing this pathway, this pathway has grown from initially attracting 150 internal medicine applicants yearly to 265 in 2015.10 The ABMS approved the ABIM/ABFM FPHM as its first approved designation in March 2017 after more than 2,500 physicians earned this designation.11 Of the >2,800 pediatric residency graduates (not including combined programs) each year, 10% report planning on becoming pediatric hospitalists,12 and currently only 72-74 fellows graduate from PHM fellowships yearly.13 FPHM for pediatric hospital medicine would provide focused maintenance of certification and hospitalist designation for those who cannot match to fellowship programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the input and support from the Executive Council of the Society of Hospital Medicine Pediatric Special Interest Group in writing this statement.

Disclosures

Dr. Chang served as an author of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition to the American Board of Pediatrics for Subspecialty Certification. Drs. Hopkins, Rehm, Gage, and Shen have nothing to disclose.

The first Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) fellowships in the United States were established in 2003;1 and since then, the field has expanded and matured dramatically. This growth, accompanied by greater definition of the role and recommended competencies of pediatric hospitalists,2 culminated in the submission of a petition to the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) in August 2014 to consider recognition of PHM as a new pediatric subspecialty.3 After an 18-month iterative process requiring extensive input from the Joint Council of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, ABP subcommittees, the Association of Medical School Pediatric Department Chairs, the Association of Pediatric Program Directors, and other prominent pediatric professional societies, the ABP voted in December 2015 to recommend that the American Board of Medical Subspecialties (ABMS) recognize PHM as a new subspecialty.3

The ABP subsequently announced three pathways for board certification in PHM:

- Training pathway for those completing an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education–accredited two-year PHM fellowship program;

- Practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM for four years prior to exam dates (in 2019, 2021, and 2023), initially described as “direct patient care of hospitalized children ≥25% full-time equivalent (FTE) defined as ≥450-500 hours per year every year for the preceding four years”;4

- Combined pathway for those completing less than two years of fellowship, who would be required to complete two years of practice experience that satisfy the same criteria as each year of the practice pathway.5

While the training pathway met near-uniform acceptance, concerns were raised through the American Academy of Pediatrics Section of Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) Listserv regarding the practice pathway, and by extension, the combined pathway. Specifically, language describing the necessary characteristics of acceptable PHM practice was felt to be vague and not transparent. Listserv posts also raised concerns regarding the potential exclusion of “niche” practices such as subspecialty hospitalists and newborn hospitalists. As applicants in the practice pathway began to receive denials, opinions voiced in listserv posts were increasingly critical of the ABP’s lack of transparency regarding the specific criteria adjudicating applications.

ORIGIN OF THE PHM PETITION

A group of hospitalists, led by Dr. David Skey, a pediatric hospitalist at Arnold Palmer Children’s Hospital in Orlando, Florida, created a petition which was submitted to the ABP on August 6, 2019, and raised the following issues:

- “A perception of unfairness/bias in the practice pathway criteria and the way these criteria have been applied.

- Denials based on gaps in employment without reasonable consideration of mitigating factors.

- Lack of transparency, accountability, and responsiveness from the ABP.”6

The petition, posted on the AAP SOHM listserv and signed by 1,479 individuals,7 raised concerns of anecdotal evidence that the practice pathway criteria disproportionately disadvantaged women, although intentional bias was not suspected by the signers of the letter. The petition’s signers submitted the following demands to the ABP:

- “Facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias is present or perform this analysis internally and release the findings publicly.

- Revise the practice pathway criteria to be more inclusive of applicants with interrupted practice and varied clinical experience, to include clear-cut parameters rather than considering these applications on a closed-door ‘case-by-case basis...at the discretion of the ABP’.

- Clarify the appeals process and improve responsiveness to appeals and inquiries regarding denials.

- Provide a formal response to this petition letter through the PHM ListServ and/or the ABP website within one week of receiving the signed petition.”6

THE ABP RESPONSE TO THE PHM PETITION

A formal response to the petition was released on the AAP SOHM Listserv on August 29, 2019, to address the concerns raised and is published in this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine.4 In response to the allegation of gender bias, the ABP maintained that the data did not support this, as the denial rate for females (4.0%) was not significantly different than that for males (3.7%). The response acknowledged that once clear-cut criteria were decided upon to augment the general practice pathway criteria published at the outset, these criteria should have been disseminated. The ABP maintained, however, that these criteria, once established, were used consistently in adjudicating all applications. To clarify and simplify the eligibility criteria, the percentage of the full-time equivalent and practice interruption criteria were removed, as the work-hours criteria (direct patient care of hospitalized children ≥450-500 hours per year every year for the preceding four years)8 were deemed sufficient to ensure adequate clinical participation.

SHM’S POSITION REGARDING THE PHM PETITION AND ABP RESPONSE

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), through pediatric hospitalists and pediatricians on its Board, committees, and the Executive Council of the Pediatric Special Interest Group, has followed with great interest the public debate surrounding the PHM certification process and the subsequent PHM petition to the ABP. The ABP responded swiftly and with full transparency to the petition, and SHM supports these efforts by the ABP to provide a timely, honest, data-driven response to the concerns raised by the PHM petition. SHM recognizes that the mission of the ABP is to provide the public with confidence that physicians with ABP board certifications meet appropriate “standards of excellence”. While the revisions implemented by the ABP in its response still may not satisfy the concerns of all members of the PHM community, SHM recognizes that the revised requirements remain true to the mission of the ABP.

SHM applauds the authors and signatories of the PHM petition for bravely raising their concerns of gender bias and lack of transparency. The response of the ABP to this petition by further improving transparency serves as an example of continuous improvement in collaborative practice to all medical specialty boards.

While SHM supports the ABP response to the PHM petition, it is clear that excellent physicians caring for hospitalized children will be unable to achieve PHM board certification for a variety of reasons. For these physicians who are not PHM board certified as pediatric hospitalists by the ABP, SHM supports providing these physicians with recognition as hospitalists. These include “niche” hospitalists, such as newborn hospitalists, subacute hospitalists, and subspecialty hospitalists. SHM will also continue to support and recognize community-based hospitalists, family medicine-trained hospitalists, and Med-Peds hospitalists whose practice may not comply with criteria laid out by the ABP. For these physicians, receiving Fellow designation through SHM, a merit-based distinction requiring demonstration of clinical excellence and commitment to hospital medicine, is another route whereby physicians can achieve designation as a hospitalist.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR PEDIATRIC HOSPITALISTS

SHM supports future efforts by the ABP to be vigilant for bias of any sort in the certification process. Other future considerations for the PHM community include the possibility of a focused practice pathway in hospital medicine (FPHM) for pediatrics as is currently jointly offered by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM). This maintenance of certification program is a variation of internal medicine or family medicine recertification, not a subspecialty, but allows physicians practicing primarily in inpatient settings to focus continuing education efforts on skills and attitudes needed for inpatient practice.9 While this possibility was discounted by the ABP in the past based on initially low numbers of physicians choosing this pathway, this pathway has grown from initially attracting 150 internal medicine applicants yearly to 265 in 2015.10 The ABMS approved the ABIM/ABFM FPHM as its first approved designation in March 2017 after more than 2,500 physicians earned this designation.11 Of the >2,800 pediatric residency graduates (not including combined programs) each year, 10% report planning on becoming pediatric hospitalists,12 and currently only 72-74 fellows graduate from PHM fellowships yearly.13 FPHM for pediatric hospital medicine would provide focused maintenance of certification and hospitalist designation for those who cannot match to fellowship programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the input and support from the Executive Council of the Society of Hospital Medicine Pediatric Special Interest Group in writing this statement.

Disclosures

Dr. Chang served as an author of the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition to the American Board of Pediatrics for Subspecialty Certification. Drs. Hopkins, Rehm, Gage, and Shen have nothing to disclose.

1. Freed GL, Dunham KM, Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of P. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):157-163. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.409.

2. Stucky ER, Maniscalco J, Ottolini MC, et al. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies Supplement: a Framework for Curriculum Development by the Society of Hospital Medicine with acknowledgement to pediatric hospitalists from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Academic Pediatric Association. J Hosp Med. 2010;5 Suppl 2:i-xv, 1-114. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.776.

3. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric Hospital Medicine: A Proposed New Subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

4. Nichols DG WS. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):586-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3322.

5. Pediatric hospital medicine certification. American Board of Pediatrics. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification#training. Accessed 3 September, 2019.

6. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC. https://www.phmpetition.com/. Accessed 3 September, 2019.

7. Skey D. Petition Update. In: AAP SOHM Listserv: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2019.

8. The American Board of Pediatrics Response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition. The American Board of Pediatrics. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

9. Focused practice in hospital medicine. American Board of Internal Medicine. https://www.abim.org/maintenance-of-certification/moc-requirements/focused-practice-hospital-medicine.aspx. Published 2019 Accessed September 4, 2019.

10. Butterfield S. Following the focused practice pathway. American College of Physicians. Your career Web site. https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2016/09/focused-practice-hospital-medicine.htm. Published 2016. Accessed September 4, 2019.

11. American Board of Medical Specialties Announces New, Focused Practice Designation [press release]. American Board of Medical Specialties, 14 Mar 2017.

12. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating Pediatric Residents Entering the Hospital Medicine Workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

13. PHM Fellowship Programs. PHMFellows.org. http://phmfellows.org/phm-programs/. Published 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

1. Freed GL, Dunham KM, Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of P. Characteristics of pediatric hospital medicine fellowships and training programs. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(3):157-163. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.409.

2. Stucky ER, Maniscalco J, Ottolini MC, et al. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies Supplement: a Framework for Curriculum Development by the Society of Hospital Medicine with acknowledgement to pediatric hospitalists from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Academic Pediatric Association. J Hosp Med. 2010;5 Suppl 2:i-xv, 1-114. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.776.

3. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric Hospital Medicine: A Proposed New Subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

4. Nichols DG WS. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):586-588. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3322.

5. Pediatric hospital medicine certification. American Board of Pediatrics. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification#training. Accessed 3 September, 2019.

6. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC. https://www.phmpetition.com/. Accessed 3 September, 2019.

7. Skey D. Petition Update. In: AAP SOHM Listserv: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2019.

8. The American Board of Pediatrics Response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition. The American Board of Pediatrics. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

9. Focused practice in hospital medicine. American Board of Internal Medicine. https://www.abim.org/maintenance-of-certification/moc-requirements/focused-practice-hospital-medicine.aspx. Published 2019 Accessed September 4, 2019.

10. Butterfield S. Following the focused practice pathway. American College of Physicians. Your career Web site. https://acphospitalist.org/archives/2016/09/focused-practice-hospital-medicine.htm. Published 2016. Accessed September 4, 2019.

11. American Board of Medical Specialties Announces New, Focused Practice Designation [press release]. American Board of Medical Specialties, 14 Mar 2017.

12. Leyenaar JK, Frintner MP. Graduating Pediatric Residents Entering the Hospital Medicine Workforce, 2006-2015. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2):200-207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2017.05.001.

13. PHM Fellowship Programs. PHMFellows.org. http://phmfellows.org/phm-programs/. Published 2019. Accessed September 4, 2019.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Recommendations on the Use of Ultrasound Guidance for Central and Peripheral Vascular Access in Adults: A Position Statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Approximately five million central venous catheters (CVCs) are inserted in the United States annually, with over 15 million catheter days documented in intensive care units alone.1 Traditional CVC insertion techniques using landmarks are associated with a high risk of mechanical complications, particularly pneumothorax and arterial puncture, which occur in 5%-19% patients.2,3

Since the 1990s, several randomized controlled studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that the use of real-time ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion increases procedure success rates and decreases mechanical complications.4,5 Use of real-time ultrasound guidance was recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Institute of Medicine, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and several medical specialty societies in the early 2000s.6-14 Despite these recommendations, ultrasound guidance has not been universally adopted. Currently, an estimated 20%-55% of CVC insertions in the internal jugular vein are performed without ultrasound guidance.15-17

Following the emergence of literature supporting the use of ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion, observational and randomized controlled studies demonstrated improved procedural success rates with the use of ultrasound guidance for the insertion of peripheral intravenous lines (PIVs), arterial catheters, and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs).18-23

The purpose of this position statement is to present evidence-based recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for the insertion of central and peripheral vascular access catheters in adult patients. This document presents consensus-based recommendations with supporting evidence for clinical outcomes, techniques, and training for the use of ultrasound guidance for vascular access. We have subdivided the recommendations on techniques for central venous access, peripheral venous access, and arterial access individually, as some providers may not perform all types of vascular access procedures.

These recommendations are intended for hospitalists and other healthcare providers that routinely place central and peripheral vascular access catheters in acutely ill patients. However, this position statement does not mandate that all hospitalists should place central or peripheral vascular access catheters given the diverse array of hospitalist practice settings. For training and competency assessments, we recognize that some of these recommendations may not be feasible in resource-limited settings, such as rural hospitals, where equipment and staffing for assessments are not available. Recommendations and frameworks for initial and ongoing credentialing of hospitalists in ultrasound-guided bedside procedures have been previously published in an Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) position statement titled, “Credentialing of Hospitalists in Ultrasound-Guided Bedside Procedures.”24

METHODS

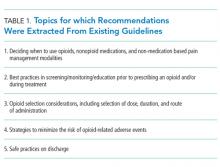

Detailed methods are described in Appendix 1. The SHM Point-of-care Ultrasound (POCUS) Task Force was assembled to carry out this guideline development project under the direction of the SHM Board of Directors, Director of Education, and Education Committee. All expert panel members were physicians or advanced practice providers with expertise in POCUS. Expert panel members were divided into working group members, external peer reviewers, and a methodologist. All Task Force members were required to disclose any potential conflicts of interest (Appendix 2). The literature search was conducted in two independent phases. The first phase included literature searches conducted by the vascular access working group members themselves. Key clinical questions and draft recommendations were then prepared. A systematic literature search was conducted by a medical librarian based on the findings of the initial literature search and draft recommendations. The Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Cochrane medical databases were searched from 1975 to December 2015 initially. Google Scholar was also searched without limiters. An updated search was conducted in November 2017. The literature search strings are included in Appendix 3. All article abstracts were initially screened for relevance by at least two members of the vascular access working group. Full-text versions of screened articles were reviewed, and articles on the use of ultrasound to guide vascular access were selected. The following article types were excluded: non-English language, nonhuman, age <18 years, meeting abstracts, meeting posters, narrative reviews, case reports, letters, and editorials. All relevant systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled studies, and observational studies of ultrasound-guided vascular access were screened and selected (Appendix 3, Figure 1). All full-text articles were shared electronically among the working group members, and final article selection was based on working group consensus. Selected articles were incorporated into the draft recommendations.

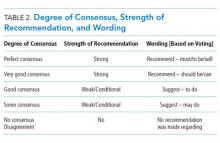

These recommendations were developed using the Research and Development (RAND) Appropriateness Method that required panel judgment and consensus.14 The 28 voting members of the SHM POCUS Task Force reviewed and voted on the draft recommendations considering five transforming factors: (1) Problem priority and importance, (2) Level of quality of evidence, (3) Benefit/harm balance, (4) Benefit/burden balance, and (5) Certainty/concerns about PEAF (Preferences/Equity/Acceptability/Feasibility). Using an internet-based electronic data collection tool (REDCap™), panel members participated in two rounds of electronic voting, one in August 2018 and the other in October 2018 (Appendix 4). Voting on appropriateness was conducted using a nine-point Likert scale. The three zones of the nine-point Likert scale were inappropriate (1-3 points), uncertain (4-6 points), and appropriate (7-9 points). The degree of consensus was assessed using the RAND algorithm (Appendix 1, Figure 1 and Table 1). Establishing a recommendation required at least 70% agreement that a recommendation was “appropriate.” Disagreement was defined as >30% of panelists voting outside of the zone of the median. A strong recommendation required at least 80% of the votes within one integer of the median per the RAND rules.

Recommendations were classified as strong or weak/conditional based on preset rules defining the panel’s level of consensus, which determined the wording for each recommendation (Table 2). The final version of the consensus-based recommendations underwent internal and external review by members of the SHM POCUS Task Force, the SHM Education Committee, and the SHM Executive Committee. The SHM Executive Committee reviewed and approved this position statement prior to its publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

RESULTS

Literature Search

A total of 5,563 references were pooled from an initial search performed by a certified medical librarian in December 2015 (4,668 citations) which was updated in November 2017 (791 citations), and from the personal bibliographies and searches (104 citations) performed by working group members. A total of 514 full-text articles were reviewed. The final selection included 192 articles that were abstracted into a data table and incorporated into the draft recommendations. See Appendix 3 for details of the literature search strategy.

Recommendations

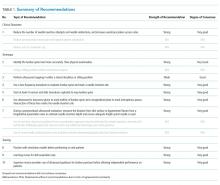

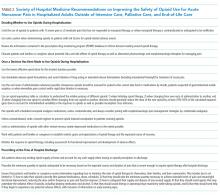

Four domains (technique, clinical outcomes, training, and knowledge gaps) with 31 draft recommendations were generated based on a review of the literature. Selected references were abstracted and assigned to each draft recommendation. Rationales for each recommendation cite supporting evidence. After two rounds of panel voting, 31 recommendations achieved agreement based on the RAND rules. During the peer review process, two of the recommendations were merged with other recommendations. Thus, a total of 29 recommendations received final approval. The degree of consensus based on the median score and the dispersion of voting around the median are shown in Appendix 5. Twenty-seven statements were approved as strong recommendations, and two were approved as weak/conditional recommendations. The strength of each recommendation and degree of consensus are summarized in Table 3.

Terminology

Central Venous Catheterization

Central venous catheterization refers to insertion of tunneled or nontunneled large bore vascular catheters that are most commonly inserted into the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral veins with the catheter tip located in a central vein. These vascular access catheters are synonymously referred to as central lines or central venous catheters (CVCs). Nontunneled catheters are designed for short-term use and should be removed promptly when no longer clinically indicated or after a maximum of 14 days.25

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC)

Peripherally inserted central catheters, or PICC lines, are inserted most commonly in the basilic or brachial veins in adult patients, and the catheter tip terminates in the distal superior vena cava or cavo-atrial junction. These catheters are designed to remain in place for a duration of several weeks, as long as it is clinically indicated.

Midline Catheterization

Midline catheters are a type of peripheral venous catheter that are an intermediary between a peripheral intravenous catheter and PICC line. Midline catheters are most commonly inserted in the brachial or basilic veins, but unlike PICC lines, the tips of these catheters terminate in the axillary or subclavian vein. Midline catheters are typically 8 cm to 20 cm in length and inserted for a duration <30 days.

Peripheral Intravenous Catheterization

Peripheral intravenous lines (PIV) refer to small bore venous catheters that are most commonly 14G to 24G and inserted into patients for short-term peripheral venous access. Common sites of ultrasound-guided PIV insertion include the superficial and deep veins of the hand, forearm, and arm.

Arterial Catheterization

Arterial catheters are commonly used for reliable blood pressure monitoring, frequent arterial blood

RECOMMENDATIONS

Preprocedure

1. We recommend that providers should be familiar with the operation of their specific ultrasound machine prior to initiation of a vascular access procedure.

Rationale: There is strong consensus that providers must be familiar with the knobs and functions of the specific make and model of ultrasound machine that will be utilized for a vascular access procedure. Minimizing adjustments to the ultrasound machine during the procedure may reduce the risk of contaminating the sterile field.

2. We recommend that providers should use a high-frequency linear transducer with a sterile sheath and sterile gel to perform vascular access procedures.

Rationale: High-frequency linear-array transducers are recommended for the vast majority of vascular access procedures due to their superior resolution compared to other transducer types. Both central and peripheral vascular access procedures, including PIV, PICC, and arterial line placement, should be performed using sterile technique. A sterile transducer cover and sterile gel must be utilized, and providers must be trained in sterile preparation of the ultrasound transducer.13,26,27

The depth of femoral vessels correlates with body mass index (BMI). When accessing these vessels in a morbidly obese patient with a thigh circumference >60 cm and vessel depth >8 cm, a curvilinear transducer may be preferred for its deeper penetration.28 For patients who are poor candidates for bedside insertion of vascular access catheters, such as uncooperative patients, patients with atypical vascular anatomy or poorly visualized target vessels, we recommend consultation with a vascular access specialist prior to attempting the procedure.

3. We recommend that providers should use two-dimensional ultrasound to evaluate for anatomical variations and absence of vascular thrombosis during preprocedural site selection.

Rationale: A thorough ultrasound examination of the target vessel is warranted prior to catheter placement. Anatomical variations that may affect procedural decision-making are easily detected with ultrasound. A focused vascular ultrasound examination is particularly important in patients who have had temporary or tunneled venous catheters, which can cause stenosis or thrombosis of the target vein.

For internal jugular vein (IJV) CVCs, ultrasound is useful for visualizing the relationship between the IJV and common carotid artery (CCA), particularly in terms of vessel overlap. Furthermore, ultrasound allows for immediate revisualization upon changes in head position.29-32 Troianos et al. found >75% overlap of the IJV and CCA in 54% of all patients and in 64% of older patients (age >60 years) whose heads were rotated to the contralateral side.30 In one study of IJV CVC insertion, inadvertent carotid artery punctures were reduced (3% vs 10%) with the use of ultrasound guidance vs landmarks alone.33 In a cohort of 64 high-risk neurosurgical patients, cannulation success was 100% with the use of ultrasound guidance, and there were no injuries to the carotid artery, even though the procedure was performed with a 30-degree head elevation and anomalous IJV anatomy in 39% of patients.34 In a prospective, randomized controlled study of 1,332 patients, ultrasound-guided cannulation in a neutral position was demonstrated to be as safe as the 45-degree rotated position.35

Ultrasound allows for the recognition of anatomical variations which may influence the selection of the vascular access site or technique. Benter et al. found that 36% of patients showed anatomical variations in the IJV and surrounding tissue.36 Similarly Caridi showed the anatomy of the right IJV to be atypical in 29% of patients,37 and Brusasco found that 37% of bariatric patients had anatomical variations of the IJV.38 In a study of 58 patients, there was significant variability in the IJV position and IJV diameter, ranging from 0.5 cm to >2 cm.39 In a study of hemodialysis patients, 75% of patients had sonographic venous abnormalities that led to a change in venous access approach.40

To detect acute or chronic upper extremity deep venous thrombosis or stenosis, two-dimensional visualization with compression should be part of the ultrasound examination prior to central venous catheterization. In a study of patients that had undergone CVC insertion 9-19 weeks earlier, 50% of patients had an IJV thrombosis or stenosis leading to selection of an alternative site. In this study, use of ultrasound for a preprocedural site evaluation reduced unnecessary attempts at catheterizing an occluded vein.41 At least two other studies demonstrated an appreciable likelihood of thrombosis. In a study of bariatric patients, 8% of patients had asymptomatic thrombosis38 and in another study, 9% of patients being evaluated for hemodialysis catheter placement had asymptomatic IJV thrombosis.37

4. We recommend that providers should evaluate the target blood vessel size and depth during a preprocedural ultrasound evaluation.

Rationale: The size, depth, and anatomic location of central veins can vary considerably. These features are easily discernable using ultrasound. Contrary to traditional teaching, the IJV is located 1 cm anterolateral to the CCA in only about two-thirds of patients.37,39,42,43 Furthermore, the diameter of the IJV can vary significantly, ranging from 0.5 cm to >2 cm.39 The laterality of blood vessels may vary considerably as well. A preprocedural ultrasound evaluation of contralateral subclavian and axillary veins showed a significant absolute difference in cross-sectional area of 26.7 mm2 (P < .001).42

Blood vessels can also shift considerably when a patient is in the Trendelenburg position. In one study, the IJV diameter changed from 11.2 (± 1.5) mm to 15.4 (± 1.5) mm in the supine versus the Trendelenburg position at 15 degrees.33 An observational study demonstrated a frog-legged position with reverse Trendelenburg increased the femoral vein size and reduced the common surface area with the common femoral artery compared to a neutral position. Thus, a frog-legged position with reverse Trendelenburg position may be preferred, since overall catheterization success rates are higher in this position.44

Techniques

General Techniques

5. We recommend that providers should avoid using static ultrasound alone to mark the needle insertion site for vascular access procedures.

Rationale: The use of static ultrasound guidance to mark a needle insertion site is not recommended because normal anatomical relationships of vessels vary, and site marking can be inaccurate with minimal changes in patient position, especially of the neck.43,45,46 Benefits of using ultrasound guidance for vascular access are attained when ultrasound is used to track the needle tip in real-time as it is advanced toward the target vessel.

Although continuous-wave Doppler ultrasound without two-dimensional visualization was used in the past, it is no longer recommended for IJV CVC insertion.47 In a study that randomized patients to IJV CVC insertion with continuous-wave Doppler alone vs two-dimensional ultrasound guidance, the use of two-dimensional ultrasound guidance showed significant improvement in first-pass success rates (97% vs 91%, P = .045), particularly in patients with BMI >30 (97% vs 77%, P = .011).48

A randomized study comparing real-time ultrasound-guided, landmark-based, and ultrasound-marked techniques found higher success rates in the real-time ultrasound-guided group than the other two groups (100% vs 74% vs 73%, respectively; P = .01). The total number of mechanical complications was higher in the landmark-based and ultrasound-marked groups than in the real-time ultrasound-guided group (24% and 36% versus 0%, respectively; P = .01).49 Another randomized controlled study found higher success rates with real-time ultrasound guidance (98%) versus an ultrasound-marked (82%) or landmark-based (64%) approach for central line placement.50

6. We recommend that providers should use real-time (dynamic), two-dimensional ultrasound guidance with a high-frequency linear transducer for CVC insertion, regardless of the provider’s level of experience.

7. We suggest using either a transverse (short-axis) or longitudinal (long-axis) approach when performing real-time ultrasound-guided vascular access procedures.

Rationale: In clinical practice, the phrases transverse, short-axis, or out-of-plane approach are synonymous, as are longitudinal, long-axis, and in-plane approach. The short-axis approach involves tracking the needle tip as it approximates the target vessel with the ultrasound beam oriented in a transverse plane perpendicular to the target vessel. The target vessel is seen as a circular structure on the ultrasound screen as the needle tip approaches the target vessel from above. This approach is also called the out-of-plane technique since the needle passes through the ultrasound plane. The advantages of the short-axis approach include better visualization of adjacent vessels or nerves and the relative ease of skill acquisition for novice operators.9 When using the short-axis approach, extra care must be taken to track the needle tip from the point of insertion on the skin to the target vessel. A disadvantage of the short-axis approach is unintended posterior wall puncture of the target vessel.55

In contrast to a short-axis approach, a long-axis approach is performed with the ultrasound beam aligned parallel to the vessel. The vessel appears as a long tubular structure and the entire needle is visualized as it traverses across the ultrasound screen to approach the target vessel. The long-axis approach is also called an in-plane technique because the needle is maintained within the plane of the ultrasound beam. The advantage of a long-axis approach is the ability to visualize the entire needle as it is inserted into the vessel.14 A randomized crossover study with simulation models compared a long-axis versus short-axis approach for both IJV and subclavian vein catheterization. This study showed decreased number of needle redirections (relative risk (RR) 0.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.3 to 0.7), and posterior wall penetrations (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.9) using a long-axis versus short-axis approach for subclavian vein catheterization.56

A randomized controlled study comparing a long-axis or short-axis approach with ultrasound versus a landmark-based approach for IJV CVC insertion showed higher success rates (100% vs 90%; P < .001), lower insertion time (53 vs 116 seconds; P < .001), and fewer attempts to obtain access (2.5 vs 1.2 attempts, P < .001) with either the long- or short-axis ultrasound approach. The average time to obtain access and number of attempts were comparable between the short-axis and long-axis approaches with ultrasound. The incidence of carotid puncture and hematoma was significantly higher with the landmark-based approach versus either the long- or short-axis ultrasound approach (carotid puncture 17% vs 3%, P = .024; hematoma 23% vs 3%, P = .003).57

High success rates have been reported using a short-axis approach for insertion of PIV lines.58 A prospective, randomized trial compared the short-axis and long-axis approach in patients who had had ≥2 failed PIV insertion attempts. Success rate was 95% (95% CI, 0.85 to 1.00) in the short-axis group compared with 85% (95% CI, 0.69 to 1.00) in the long-axis group. All three subjects with failed PIV placement in the long-axis group had successful rescue placement using a short-axis approach. Furthermore, the short-axis approach was faster than the long-axis approach.59

For radial artery cannulation, limited data exist comparing the short- and long-axis approaches. A randomized controlled study compared a long-axis vs short-axis ultrasound approach for radial artery cannulation. Although the overall procedure success rate was 100% in both groups, the long-axis approach had higher first-pass success rates (1.27 ± 0.4 vs 1.5 ± 0.5, P < .05), shorter cannulation times (24 ± 17 vs 47 ± 34 seconds, P < .05), fewer hematomas (4% vs 43%, P < .05) and fewer posterior wall penetrations (20% vs 56%, P < .05).60

Another technique that has been described for IJV CVC insertion is an oblique-axis approach, a hybrid between the long- and short-axis approaches. In this approach, the transducer is aligned obliquely over the IJV and the needle is inserted using a long-axis or in-plane approach. A prospective randomized trial compared the short-axis, long-axis, and oblique-axis approaches during IJV cannulation. First-pass success rates were 70%, 52%, and 74% with the short-axis, long-axis, and oblique-axis approaches, respectively, and a statistically significant difference was found between the long- and oblique-axis approaches (P = .002). A higher rate of posterior wall puncture was observed with a short-axis approach (15%) compared with the oblique-axis (7%) and long-axis (4%) approaches (P = .047).61

8. We recommend that providers should visualize the needle tip and guidewire in the target vein prior to vessel dilatation.

Rationale: When real-time ultrasound guidance is used, visualization of the needle tip within the vein is the first step to confirm cannulation of the vein and not the artery. After the guidewire is advanced, the provider can use transverse and longitudinal views to reconfirm cannulation of the vein. In a longitudinal view, the guidewire is readily seen positioned within the vein, entering the anterior wall and lying along the posterior wall of the vein. Unintentional perforation of the posterior wall of the vein with entry into the underlying artery can be detected by ultrasound, allowing prompt removal of the needle and guidewire before proceeding with dilation of the vessel. In a prospective observational study that reviewed ultrasound-guided IJV CVC insertions, physicians were able to more readily visualize the guidewire than the needle in the vein.62 A prospective observational study determined that novice operators can visualize intravascular guidewires in simulation models with an overall accuracy of 97%.63

In a retrospective review of CVC insertions where the guidewire position was routinely confirmed in the target vessel prior to dilation, there were no cases of arterial dilation, suggesting confirmation of guidewire position can potentially eliminate the morbidity and mortality associated with arterial dilation during CVC insertion.64

9. To increase the success rate of ultrasound-guided vascular access procedures, we recommend that providers should utilize echogenic needles, plastic needle guides, and/or ultrasound beam steering when available.

Rationale: Echogenic needles have ridged tips that appear brighter on the screen, allowing for better visualization of the needle tip. Plastic needle guides help stabilize the needle alongside the transducer when using either a transverse or longitudinal approach. Although evidence is limited, some studies have reported higher procedural success rates when using echogenic needles, plastic needle guides, and ultrasound beam steering software. In a prospective observational study, Augustides et al. showed significantly higher IJV cannulation rates with versus without use of a needle guide after first (81% vs 69%, P = .0054) and second (93% vs 80%. P = .0001) needle passes.65 A randomized study by Maecken et al. compared subclavian vein CVC insertion with or without use of a needle guide, and found higher procedure success rates within the first and second attempts, reduced time to obtain access (16 seconds vs 30 seconds; P = .0001) and increased needle visibility (86% vs 32%; P < .0001) with the use of a needle guide.66 Another study comparing a short-axis versus long-axis approach with a needle guide showed improved needle visualization using a long-axis approach with a needle guide.67 A randomized study comparing use of a novel, sled-mounted needle guide to a free-hand approach for venous cannulation in simulation models showed the novel, sled-mounted needle guide improved overall success rates and efficiency of cannulation.68

Central Venous Access Techniques

10. We recommend that providers should use a standardized procedure checklist that includes use of real-time ultrasound guidance to reduce the risk of central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) from CVC insertion.

Rationale: A standardized checklist or protocol should be developed to ensure compliance with all recommendations for insertion of CVCs. Evidence-based protocols address periprocedural issues, such as indications for CVC, and procedural techniques, such as use of maximal sterile barrier precautions to reduce the risk of infection. Protocols and checklists that follow established guidelines for CVC insertion have been shown to decrease CLABSI rates.69,70 Similarly, development of checklists and protocols for maintenance of central venous catheters have been effective in reducing CLABSIs.71 Although no externally-validated checklist has been universally accepted or endorsed by national safety organizations, a few internally-validated checklists are available through peer-reviewed publications.72,73 An observational educational cohort of internal medicine residents who received training using simulation of the entire CVC insertion process was able to demonstrate fewer CLABSIs after the simulator-trained residents rotated in the intensive care unit (ICU) (0.50 vs 3.2 infections per 1,000 catheter days, P = .001).74

11. We recommend that providers should use real-time ultrasound guidance, combined with aseptic technique and maximal sterile barrier precautions, to reduce the incidence of infectious complications from CVC insertion.

Rationale: The use of real-time ultrasound guidance for CVC placement has demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in CLABSIs compared to landmark-based techniques.75 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections recommend the use of ultrasound guidance to reduce the number of cannulation attempts and risk of mechanical complications.69 A prospective, three-arm study comparing ultrasound-guided long-axis, short-axis, and landmark-based approaches showed a CLABSI rate of 20% in the landmark-based group versus 10% in each of the ultrasound groups.57 Another randomized study comparing use of ultrasound guidance to a landmark-based technique for IJV CVC insertion demonstrated significantly lower CLABSI rates with the use of ultrasound (2% vs 10%; P < .05).72

Studies have shown that a systems-based intervention featuring a standardized catheter kit or catheter bundle significantly reduced CLABSI rates.76-78 A complete review of all preventive measures to reduce the risk of CLABSI is beyond the scope of this review, but a few key points will be mentioned. First, aseptic technique includes proper hand hygiene and skin sterilization, which are essential measures to reduce cutaneous colonization of the insertion site and reduce the risk of CLABSIs.79 In a systematic review and meta-analysis of eight studies including over 4,000 catheter insertions, skin antisepsis with chlorhexidine was associated with a 50% reduction in CLABSIs compared with povidone iodine.11 Therefore, a chlorhexidine-containing solution is recommended for skin preparation prior to CVC insertion per guidelines by Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee/CDC, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Infectious Diseases Society of America, and American Society of Anesthesiologists.11,69,80,81 Second, maximal sterile barrier precautions refer to the use of sterile gowns, sterile gloves, caps, masks covering both the mouth and nose, and sterile full-body patient drapes. Use of maximal sterile barrier precautions during CVC insertion has been shown to reduce the incidence of CLABSIs compared to standard precautions.26,79,82-84 Third, catheters containing antimicrobial agents may be considered for hospital units with higher CLABSI rates than institutional goals, despite a comprehensive preventive strategy, and may be considered in specific patient populations at high risk of severe complications from a CLABSI.11,69,80 Finally, providers should use a standardized procedure set-up when inserting CVCs to reduce the risk of CLABSIs. The operator should confirm availability and proper functioning of ultrasound equipment prior to commencing a vascular access procedure. Use of all-inclusive procedure carts or kits with sterile ultrasound probe covers, sterile gel, catheter kits, and other necessary supplies is recommended to minimize interruptions during the procedure, and can ultimately reduce the risk of CLABSIs by ensuring maintenance of a sterile field during the procedure.13

12. We recommend that providers should use real-time ultrasound guidance for internal jugular vein catheterization, which reduces the risk of mechanical and infectious complications, the number of needle passes, and time to cannulation and increases overall procedure success rates.

Rationale: The use of real-time ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion has repeatedly demonstrated better outcomes compared to a landmark-based approach in adults.13 Several randomized controlled studies have demonstrated that real-time ultrasound guidance for IJV cannulation reduces the risk of procedure-related mechanical and infectious complications, and improves first-pass and overall success rates in diverse care settings.27,29,45,50,53,65,75,85-90 Mechanical complications that are reduced with ultrasound guidance include pneumothorax and carotid artery puncture.4,5,45,46,53,62,75,86-93 Currently, several medical societies strongly recommend the use of ultrasound guidance during insertion of IJV CVCs.10-12,14,94-96

A meta-analysis by Hind et al. that included 18 randomized controlled studies demonstrated use of real-time ultrasound guidance reduced failure rates (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.33; P < .0001), increased first-attempt success rates (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.88; P = .009), reduced complication rates (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.87; P = .02) and reduced procedure time (P < .0001), compared to a traditional landmark-based approach when inserting IJV CVCs.5

A Cochrane systematic review compared ultrasound-guided versus landmark-based approaches for IJV CVC insertion and found use of real-time ultrasound guidance reduced total complication rates by 71% (RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.52; P < .0001), arterial puncture rates by 72% (RR 0.28, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.44; P < .00001), and rates of hematoma formation by 73% (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.55; P = .0004). Furthermore, the number of attempts for successful cannulation was reduced (mean difference -1.19 attempts, 95% CI -1.45 to -0.92; P < .00001), the chance of successful insertion on the first attempt was increased by 57% (RR 1.57, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.82; P < .00001), and overall procedure success rates were modestly increased in all groups by 12% (RR 1.12, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.17; P < .00001).46

An important consideration in performing ultrasound guidance is provider experience. A prospective observational study of patients undergoing elective CVC insertion demonstrated higher complication rates for operators that were inexperienced (25.2%) versus experienced (13.6%).54 A randomized controlled study comparing experts and novices with or without the use of ultrasound guidance for IJV CVC insertion demonstrated higher success rates among expert operators and with the use of ultrasound guidance. Among novice operators, the complication rates were lower with the use of ultrasound guidance.97 One study evaluated the procedural success and complication rates of a two-physician technique with one physician manipulating the transducer and another inserting the needle for IJV CVC insertion. This study concluded that procedural success rates and frequency of complications were directly affected by the experience of the physician manipulating the transducer and not by the experience of the physician inserting the needle.98

The impact of ultrasound guidance on improving procedural success rates and reducing complication rates is greatest in patients that are obese, short necked, hypovolemic, or uncooperative.93 Several studies have demonstrated fewer needle passes and decreased time to cannulation compared to the landmark technique in these populations.46,49,53,86-88,92,93

Ultrasound-guided placement of IJV catheters can safely be performed in patients with disorders of hemostasis and those with multiple previous catheter insertions in the same vein.9 Ultrasound-guided placement of CVCs in patients with disorders of hemostasis is safe with high success and low complication rates. In a case series of liver patients with coagulopathy (mean INR 2.17 ± 1.16, median platelet count 150K), the use of ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion was highly successful with no major bleeding complications.99

A study of renal failure patients found high success rates and low complication rates in the patients with a history of multiple previous catheterizations, poor compliance, skeletal deformities, previous failed cannulations, morbid obesity, and disorders of hemostasis.100 A prospective observational study of 200 ultrasound-guided CVC insertions for apheresis showed a 100% success rate with a 92% first-pass success rate.101

The use of real-time ultrasound guidance for IJV CVC insertion has been shown to be cost effective by reducing procedure-related mechanical complications and improving procedural success rates. A companion cost-effectiveness analysis estimated that for every 1,000 patients, 90 complications would be avoided, with a net cost savings of approximately $3,200 using 2002 prices.102

13. We recommend that providers who routinely insert subclavian vein CVCs should use real-time ultrasound guidance, which has been shown to reduce the risk of mechanical complications and number of needle passes and increase overall procedure success rates compared with landmark-based techniques.

Rationale: In clinical practice, the term ultrasound-guided subclavian vein CVC insertion is commonly used. However, the needle insertion site is often lateral to the first rib and providers are technically inserting the CVC in the axillary vein. The subclavian vein becomes the axillary vein at the lateral border of the first rib where the cephalic vein branches from the subclavian vein. To be consistent with common medical parlance, we use the phrase ultrasound-guided subclavian vein CVC insertion in this document.

Advantages of inserting CVCs in the subclavian vein include reliable surface anatomical landmarks for vein location, patient comfort, and lower risk of infection.103 Several observational studies have demonstrated the technique for ultrasound-guided subclavian vein CVC insertion is feasible and safe.104-107 In a large retrospective observational study of ultrasound-guided central venous access among a complex patient group, the majority of patients were cannulated successfully and safely. The subset of patients undergoing axillary vein CVC insertion (n = 1,923) demonstrated a low rate of complications (0.7%), proving it is a safe and effective alternative to the IJV CVC insertion.107

A Cochrane review of ultrasound-guided subclavian vein cannulation (nine studies, 2,030 participants, 2,049 procedures), demonstrated that real-time two-dimensional ultrasound guidance reduced the risk of inadvertent arterial punctures (three studies, 498 participants, RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.82; P = .02) and hematoma formation (three studies, 498 participants, RR 0.26, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.76; P = .01).46 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled studies comparing ultrasound-guided versus landmark-based subclavian vein CVC insertion demonstrated a reduction in the risk of arterial punctures, hematoma formation, pneumothorax, and failed catheterization with the use of ultrasound guidance.105

A randomized controlled study comparing ultrasound-guided vs landmark-based approaches to subclavian vein cannulation found that use of ultrasound guidance had a higher success rate (92% vs 44%, P = .0003), fewer minor complications (1 vs 11, P = .002), fewer attempts (1.4 vs 2.5, P = .007) and fewer catheter kits used (1.0 vs 1.4, P = .0003) per cannulation.108

Fragou et al. randomized patients undergoing subclavian vein CVC insertion to a long-axis approach versus a landmark-based approach and found a significantly higher success rate (100% vs 87.5%, P < .05) and lower rates of mechanical complications: artery puncture (0.5% vs 5.4%), hematoma (1.5% vs 5.4%), hemothorax (0% vs 4.4%), pneumothorax (0% vs 4.9%), brachial plexus injury (0% vs 2.9%), phrenic nerve injury (0% vs 1.5%), and cardiac tamponade (0% vs 0.5%).109 The average time to obtain access and the average number of insertion attempts (1.1 ± 0.3 vs 1.9 ± 0.7, P < .05) were significantly reduced in the ultrasound group compared to the landmark-based group.95

A retrospective review of subclavian vein CVC insertions using a supraclavicular approach found no reported complications with the use of ultrasound guidance vs 23 mechanical complications (8 pneumothorax, 15 arterial punctures) with a landmark-based approach.106 However, it is important to note that a supraclavicular approach is not commonly used in clinical practice.

14. We recommend that providers should use real-time ultrasound guidance for femoral venous access, which has been shown to reduce the risk of arterial punctures and total procedure time and increase overall procedure success rates.

Rationale: Anatomy of the femoral region varies, and close proximity or overlap of the femoral vein and artery is common.51 Early studies showed that ultrasound guidance for femoral vein CVC insertion reduced arterial punctures compared with a landmark-based approach (7% vs 16%), reduced total procedure time (55 ± 19 vs 79 ± 62 seconds), and increased procedure success rates (100% vs 90%).52 A Cochrane review that pooled data from four randomized studies comparing ultrasound-guided vs landmark-based femoral vein CVC insertion found higher first-attempt success rates with the use of ultrasound guidance (RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.34 to 2.22; P < .0001) and a small increase in the overall procedure success rates (RR 1.11, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.23; P = .06). There was no difference in inadvertent arterial punctures or other complications.110

Peripheral Venous Access Techniques

15. We recommend that providers should use real-time ultrasound guidance for the insertion of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs), which is associated with higher procedure success rates and may be more cost effective compared with landmark-based techniques.

Rationale: Several studies have demonstrated that providers who use ultrasound guidance vs landmarks for PICC insertion have higher procedural success rates, lower complication rates, and lower total placement costs. A prospective observational report of 350 PICC insertions using ultrasound guidance reported a 99% success rate with an average of 1.2 punctures per insertion and lower total costs.20 A retrospective observational study of 500 PICC insertions by designated specialty nurses revealed an overall success rate of 95%, no evidence of phlebitis, and only one CLABSI among the catheters removed.21 A retrospective observational study comparing several PICC variables found higher success rates (99% vs 77%) and lower thrombosis rates (2% vs 9%) using ultrasound guidance vs landmarks alone.22 A study by Robinson et al. demonstrated that having a dedicated PICC team equipped with ultrasound increased their institutional insertion success rates from 73% to 94%.111

A randomized controlled study comparing ultrasound-guided versus landmark-based PICC insertion found high success rates with both techniques (100% vs 96%). However, there was a reduction in the rate of unplanned catheter removals (4.0% vs 18.7%; P = .02), mechanical phlebitis (0% vs 22.9%; P < .001), and venous thrombosis (0% vs 8.3%; P = .037), but a higher rate of catheter migration (32% vs 2.1%; P < .001). Compared with the landmark-based group, the ultrasound-guided group had significantly lower incidence of severe contact dermatitis (P = .038), and improved comfort and costs up to 3 months after PICC placement (P < .05).112