User login

MISSION Possible, but Incomplete: Pairing Better Access with Better Transitions in Veteran Care

What childhood game better captures communication exchange than “telephone”: as whispers pass from ear to ear, the original message degrades or transforms entirely. In complex healthcare systems, a more perilous version of “telephone” emerges, distinct from the well-worn metaphor: the signal never arrives at all. The primary care provider never even knew the patient was in the hospital; the discharge summary was never received; the patient cannot remember important details; and key medications are missing. In this edition of the Journal, Roman Ayele et al.1 used qualitative methods to explore this transitional black box between community hospitals and Veterans’ Affairs (VA) primary care clinics, illuminating how signal fragmentation may render the increasing use of care services outside the VA system as inversely proportionate to quality.

To understand why, a small amount of historical context is necessary. The VA has increasingly focused on expanding healthcare options to its nine million veterans. On June 6, 2019, the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act was passed to consolidate existing programs and lower barriers for Veterans to seek care in non-VA urgent care and subspecialty settings.2 Though this act is not specifically focused on access to community hospitals, patients seeking urgent and subspecialty care are likely to be increasingly hospitalized outside of the VA due to geographic factors affecting point-of-care decisions. Concurrent with this expansion of options is the planned replacement of the VA’s legacy electronic health record, VistA.3 Both transformations indicate the need for the VA to be watchful and to intensify its focus on safe, effective exchanges of information.

Against this backdrop, Ayele et al.3 use stakeholder interviews with veterans and both non-VA and VA clinicians to identify the current lack of standardized practices for transitions of veteran care from community hospitals to VA primary care in Eastern Colorado. The themes most linked to care fragmentation included difficulty in identifying veterans and notifying VA primary care of hospital discharges, transferring medical records, making follow-up appointments, and coordinating prescribing with VA pharmacies. Participants identified incomplete or delayed information exchanges that were further complicated by the inability to confirm transmission across systems. A patchwork of postacute care solutions failed to prevent wasteful, low-value transitional care, including unscheduled primary care walk-ins and ED visits for medication refills. Participants arrived at a simple common solution: develop a clinically trained “VA liaison” to work at the interface between VA primary care and non-VA community hospitals so as to provide a single point of contact to coordinate these transitions. In short, to have someone to pick up the phone.

The strengths of this qualitative study lie in its insights into the current gaps in care transitions through the eyes of key stakeholders. By engaging patients and providers in imagining system changes that are actionable in the near- (clinical VA liaisons) and longer-term (pharmacy and EHR integration), Ayele et al. have provided a helpful starting place in studying and improving the interface between VA and non-VA care. Stakeholders emphasized the importance of a clear access point so that outside providers can easily notify VA clinics, arrange follow-ups, and streamline physician prescribing to avoid dangerous and costly delays in care.4 Though similar issues have been illuminated in prior work on care fragmentation,4 perspective in context is a fundamental strength of qualitative research, and further highlights the urgency of this period in veteran care.

There is the old adage: “if you have seen one VA, you have seen one VA”. This is arguably reflected in how each VA medical center is situated in a different regional and local healthcare delivery context, despite a common national infrastructure. The authors acknowledge limited generalizability but provide a framework for reproducing such work in regional VA systems. A national model for transitioning patients from regional community partners to VA primary care would require further testing, and to be a credible system-wide investment, would necessitate meaningful measurement across multiple sites. Given recent evidence of strong internal VA performance compared to the private sector,5 it is time for the VA to intensify focus on external care transitions. Given its history and continued commitment to funding innovation,6 the VA ought to be up to the task. Yet, as VA hospitalists, we know only too well that the system is increasingly under pressure to apply constrained resources inside and outside its own walls. Sending business elsewhere might not only fail at improving care but also weaken the fragile care delivery infrastructure.7

The idea that access and continuity may be in conflict raises an ethical question in modern practice and shared decision-making: how do we advise patients navigating complicated and imperfect health systems to understand the choices they are making and the risks they are taking when they spread care across systems? How are access and convenience weighed against the troubled movement of information across systems? How great is the risk if their care teams do not hear the same message? Knowing that increased fragmentation disproportionately affects the marginalized and vulnerable, especially those with complex chronic care needs,8 should we advise certain patients to stay in place within a single system?

As hospitalists, we are implied players in this dangerous version of the telephone game at a fascinating time in healthcare. Unlike when we advise patients on the risks and benefits of treatment, we have little evidence to guide our patients on when to stay put and when to leave to get care outside the system, inviting the risk of lost signals, garbled messages, and worst of all, frustrating, duplicative, unsafe care. As we strive for incremental improvements toward sweeping transformations in healthcare, we may for a few more years have to remind each other—and our students—of the incredible value of one more phone call: to make sure the intended message was

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

1. Ayele RA, Lawrence E, McCreight M, et al. Perspectives of clinicians, staff, and veterans in transitioning veterans from non-VA hospitals to primary care in a single VA healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):133-139. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3320.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018. https://missionact.va.gov/ at https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/s2372/BILLS-115s2372enr.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA EHR Modernization. ehrm.va.gov. Accessed October 31, 2019.

4. Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Schleiden L, et al. Association between dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D drug benefits and potentially unsafe prescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1584-1586. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2788.

5. Weeks WB, West AN. Veterans Health Administration hospitals outperform non–Veterans health administration hospitals in most health care markets. Ann Intern Med. 2018;170(6):426-428. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1540.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Innovation Center. https://www.innovation.va.gov/. Accessed October 31, 2019.

7. Shulkin, DL. Implications for veterans’ Health Care: the danger becomes clearer [published online ahead of print July 22, 2019. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2996.

8. Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, Kansagara D. The care transitions innovation (C-TraIn) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1460-1467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2903-0.

What childhood game better captures communication exchange than “telephone”: as whispers pass from ear to ear, the original message degrades or transforms entirely. In complex healthcare systems, a more perilous version of “telephone” emerges, distinct from the well-worn metaphor: the signal never arrives at all. The primary care provider never even knew the patient was in the hospital; the discharge summary was never received; the patient cannot remember important details; and key medications are missing. In this edition of the Journal, Roman Ayele et al.1 used qualitative methods to explore this transitional black box between community hospitals and Veterans’ Affairs (VA) primary care clinics, illuminating how signal fragmentation may render the increasing use of care services outside the VA system as inversely proportionate to quality.

To understand why, a small amount of historical context is necessary. The VA has increasingly focused on expanding healthcare options to its nine million veterans. On June 6, 2019, the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act was passed to consolidate existing programs and lower barriers for Veterans to seek care in non-VA urgent care and subspecialty settings.2 Though this act is not specifically focused on access to community hospitals, patients seeking urgent and subspecialty care are likely to be increasingly hospitalized outside of the VA due to geographic factors affecting point-of-care decisions. Concurrent with this expansion of options is the planned replacement of the VA’s legacy electronic health record, VistA.3 Both transformations indicate the need for the VA to be watchful and to intensify its focus on safe, effective exchanges of information.

Against this backdrop, Ayele et al.3 use stakeholder interviews with veterans and both non-VA and VA clinicians to identify the current lack of standardized practices for transitions of veteran care from community hospitals to VA primary care in Eastern Colorado. The themes most linked to care fragmentation included difficulty in identifying veterans and notifying VA primary care of hospital discharges, transferring medical records, making follow-up appointments, and coordinating prescribing with VA pharmacies. Participants identified incomplete or delayed information exchanges that were further complicated by the inability to confirm transmission across systems. A patchwork of postacute care solutions failed to prevent wasteful, low-value transitional care, including unscheduled primary care walk-ins and ED visits for medication refills. Participants arrived at a simple common solution: develop a clinically trained “VA liaison” to work at the interface between VA primary care and non-VA community hospitals so as to provide a single point of contact to coordinate these transitions. In short, to have someone to pick up the phone.

The strengths of this qualitative study lie in its insights into the current gaps in care transitions through the eyes of key stakeholders. By engaging patients and providers in imagining system changes that are actionable in the near- (clinical VA liaisons) and longer-term (pharmacy and EHR integration), Ayele et al. have provided a helpful starting place in studying and improving the interface between VA and non-VA care. Stakeholders emphasized the importance of a clear access point so that outside providers can easily notify VA clinics, arrange follow-ups, and streamline physician prescribing to avoid dangerous and costly delays in care.4 Though similar issues have been illuminated in prior work on care fragmentation,4 perspective in context is a fundamental strength of qualitative research, and further highlights the urgency of this period in veteran care.

There is the old adage: “if you have seen one VA, you have seen one VA”. This is arguably reflected in how each VA medical center is situated in a different regional and local healthcare delivery context, despite a common national infrastructure. The authors acknowledge limited generalizability but provide a framework for reproducing such work in regional VA systems. A national model for transitioning patients from regional community partners to VA primary care would require further testing, and to be a credible system-wide investment, would necessitate meaningful measurement across multiple sites. Given recent evidence of strong internal VA performance compared to the private sector,5 it is time for the VA to intensify focus on external care transitions. Given its history and continued commitment to funding innovation,6 the VA ought to be up to the task. Yet, as VA hospitalists, we know only too well that the system is increasingly under pressure to apply constrained resources inside and outside its own walls. Sending business elsewhere might not only fail at improving care but also weaken the fragile care delivery infrastructure.7

The idea that access and continuity may be in conflict raises an ethical question in modern practice and shared decision-making: how do we advise patients navigating complicated and imperfect health systems to understand the choices they are making and the risks they are taking when they spread care across systems? How are access and convenience weighed against the troubled movement of information across systems? How great is the risk if their care teams do not hear the same message? Knowing that increased fragmentation disproportionately affects the marginalized and vulnerable, especially those with complex chronic care needs,8 should we advise certain patients to stay in place within a single system?

As hospitalists, we are implied players in this dangerous version of the telephone game at a fascinating time in healthcare. Unlike when we advise patients on the risks and benefits of treatment, we have little evidence to guide our patients on when to stay put and when to leave to get care outside the system, inviting the risk of lost signals, garbled messages, and worst of all, frustrating, duplicative, unsafe care. As we strive for incremental improvements toward sweeping transformations in healthcare, we may for a few more years have to remind each other—and our students—of the incredible value of one more phone call: to make sure the intended message was

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

What childhood game better captures communication exchange than “telephone”: as whispers pass from ear to ear, the original message degrades or transforms entirely. In complex healthcare systems, a more perilous version of “telephone” emerges, distinct from the well-worn metaphor: the signal never arrives at all. The primary care provider never even knew the patient was in the hospital; the discharge summary was never received; the patient cannot remember important details; and key medications are missing. In this edition of the Journal, Roman Ayele et al.1 used qualitative methods to explore this transitional black box between community hospitals and Veterans’ Affairs (VA) primary care clinics, illuminating how signal fragmentation may render the increasing use of care services outside the VA system as inversely proportionate to quality.

To understand why, a small amount of historical context is necessary. The VA has increasingly focused on expanding healthcare options to its nine million veterans. On June 6, 2019, the VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act was passed to consolidate existing programs and lower barriers for Veterans to seek care in non-VA urgent care and subspecialty settings.2 Though this act is not specifically focused on access to community hospitals, patients seeking urgent and subspecialty care are likely to be increasingly hospitalized outside of the VA due to geographic factors affecting point-of-care decisions. Concurrent with this expansion of options is the planned replacement of the VA’s legacy electronic health record, VistA.3 Both transformations indicate the need for the VA to be watchful and to intensify its focus on safe, effective exchanges of information.

Against this backdrop, Ayele et al.3 use stakeholder interviews with veterans and both non-VA and VA clinicians to identify the current lack of standardized practices for transitions of veteran care from community hospitals to VA primary care in Eastern Colorado. The themes most linked to care fragmentation included difficulty in identifying veterans and notifying VA primary care of hospital discharges, transferring medical records, making follow-up appointments, and coordinating prescribing with VA pharmacies. Participants identified incomplete or delayed information exchanges that were further complicated by the inability to confirm transmission across systems. A patchwork of postacute care solutions failed to prevent wasteful, low-value transitional care, including unscheduled primary care walk-ins and ED visits for medication refills. Participants arrived at a simple common solution: develop a clinically trained “VA liaison” to work at the interface between VA primary care and non-VA community hospitals so as to provide a single point of contact to coordinate these transitions. In short, to have someone to pick up the phone.

The strengths of this qualitative study lie in its insights into the current gaps in care transitions through the eyes of key stakeholders. By engaging patients and providers in imagining system changes that are actionable in the near- (clinical VA liaisons) and longer-term (pharmacy and EHR integration), Ayele et al. have provided a helpful starting place in studying and improving the interface between VA and non-VA care. Stakeholders emphasized the importance of a clear access point so that outside providers can easily notify VA clinics, arrange follow-ups, and streamline physician prescribing to avoid dangerous and costly delays in care.4 Though similar issues have been illuminated in prior work on care fragmentation,4 perspective in context is a fundamental strength of qualitative research, and further highlights the urgency of this period in veteran care.

There is the old adage: “if you have seen one VA, you have seen one VA”. This is arguably reflected in how each VA medical center is situated in a different regional and local healthcare delivery context, despite a common national infrastructure. The authors acknowledge limited generalizability but provide a framework for reproducing such work in regional VA systems. A national model for transitioning patients from regional community partners to VA primary care would require further testing, and to be a credible system-wide investment, would necessitate meaningful measurement across multiple sites. Given recent evidence of strong internal VA performance compared to the private sector,5 it is time for the VA to intensify focus on external care transitions. Given its history and continued commitment to funding innovation,6 the VA ought to be up to the task. Yet, as VA hospitalists, we know only too well that the system is increasingly under pressure to apply constrained resources inside and outside its own walls. Sending business elsewhere might not only fail at improving care but also weaken the fragile care delivery infrastructure.7

The idea that access and continuity may be in conflict raises an ethical question in modern practice and shared decision-making: how do we advise patients navigating complicated and imperfect health systems to understand the choices they are making and the risks they are taking when they spread care across systems? How are access and convenience weighed against the troubled movement of information across systems? How great is the risk if their care teams do not hear the same message? Knowing that increased fragmentation disproportionately affects the marginalized and vulnerable, especially those with complex chronic care needs,8 should we advise certain patients to stay in place within a single system?

As hospitalists, we are implied players in this dangerous version of the telephone game at a fascinating time in healthcare. Unlike when we advise patients on the risks and benefits of treatment, we have little evidence to guide our patients on when to stay put and when to leave to get care outside the system, inviting the risk of lost signals, garbled messages, and worst of all, frustrating, duplicative, unsafe care. As we strive for incremental improvements toward sweeping transformations in healthcare, we may for a few more years have to remind each other—and our students—of the incredible value of one more phone call: to make sure the intended message was

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

1. Ayele RA, Lawrence E, McCreight M, et al. Perspectives of clinicians, staff, and veterans in transitioning veterans from non-VA hospitals to primary care in a single VA healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):133-139. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3320.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018. https://missionact.va.gov/ at https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/s2372/BILLS-115s2372enr.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA EHR Modernization. ehrm.va.gov. Accessed October 31, 2019.

4. Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Schleiden L, et al. Association between dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D drug benefits and potentially unsafe prescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1584-1586. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2788.

5. Weeks WB, West AN. Veterans Health Administration hospitals outperform non–Veterans health administration hospitals in most health care markets. Ann Intern Med. 2018;170(6):426-428. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1540.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Innovation Center. https://www.innovation.va.gov/. Accessed October 31, 2019.

7. Shulkin, DL. Implications for veterans’ Health Care: the danger becomes clearer [published online ahead of print July 22, 2019. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2996.

8. Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, Kansagara D. The care transitions innovation (C-TraIn) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1460-1467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2903-0.

1. Ayele RA, Lawrence E, McCreight M, et al. Perspectives of clinicians, staff, and veterans in transitioning veterans from non-VA hospitals to primary care in a single VA healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(3):133-139. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3320.

2. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018. https://missionact.va.gov/ at https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/s2372/BILLS-115s2372enr.pdf. Accessed October 31, 2019.

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA EHR Modernization. ehrm.va.gov. Accessed October 31, 2019.

4. Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Schleiden L, et al. Association between dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare Part D drug benefits and potentially unsafe prescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(11):1584-1586. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2788.

5. Weeks WB, West AN. Veterans Health Administration hospitals outperform non–Veterans health administration hospitals in most health care markets. Ann Intern Med. 2018;170(6):426-428. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-1540.

6. US Department of Veterans Affairs: VA Innovation Center. https://www.innovation.va.gov/. Accessed October 31, 2019.

7. Shulkin, DL. Implications for veterans’ Health Care: the danger becomes clearer [published online ahead of print July 22, 2019. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2996.

8. Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, Kansagara D. The care transitions innovation (C-TraIn) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(11):1460-1467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2903-0.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Worry Loves Company, but Unnecessary Consultations May Harm the Patients We Comanage

“Never worry alone” is a common mantra that most of us have heard throughout medical training. The premise is simple and well meaning. If a patient has an issue that concerns you, ask someone for help. As a student, this can be a resident; as a resident, this can be an attending. However, for hospitalists, the answer is often a subspecialty consultation. Asking for help never seems to be wrong, but what happens when our worry delays appropriate care with unnecessary consultations? In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, authors Bellas et al. have investigated this issue through the lens of subspecialty preoperative consultation for patients admitted to a hospitalist comanagement service with a fragility hip fracture requiring surgery.1

Morbidity and mortality for patients who experience hip fractures are high, and time to appropriate surgery is one of the few modifiable risk factors that may reduce morbidity and mortality.2,3 Bellas et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study to test the association between preoperative subspecialty consultation and multiple clinically relevant outcomes in patients admitted with an acute hip fracture.1 All patients were comanaged by a hospitalist and orthopedic surgery, and “consultation” was defined as any preoperative subspecialty consultation requested by the hospitalist. Outcome measures included time to surgery, length of stay, readmission rate, perioperative complications, and 30-day mortality. In total, 36% (177/491) of patients who underwent surgery received a subspecialty preoperative consultation. Unsurprisingly, these patients were older with higher rates of comorbidity. After controlling for age and Charlson Comorbidity Index, preoperative consultation was associated with dramatic delays and increased rates of time to surgery >24 hours (adjusted odds ratio, 4.2; 95% CI: 2.8-6.6). The authors classified 90% of consultations as appropriate, either because of an active condition (eg, acute coronary syndrome) or because admitting physicians documented a perception that patients were at increased risk. However, 73% of consultations had only minor recommendations, such as ordering an ECG or changing the dose of an existing medication, and only 37% of the time did consultations lead to an identifiable change in management as a result of the consultation.

Although striking, integrating these findings into clinical practice is complex. As a retrospective study, patients who received consultations were obviously different from those who did not. The authors attempted to adjust for this but used only age and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Other factors that are both associated with consultations and known to increase mortality—such as frailty and functional status—were not included in their adjustment. Such unmeasured confounders possibly explain at least some, if not all, of the findings that consultations were associated with a doubling of the likelihood of 30-day mortality. In addition, although the authors assessed the appropriateness of consultation and degree of recommendations, their methods for this deserve scrutiny. Two independent providers adjudicated the consultations with excellent agreement (kappa 0.96 for indication, 0.95 for degree of recommendation), but this reliability assessment was done on previously extracted chart data, probably inflating their agreement statistics. Finally, the adjudication of consultant recommendations into minor, moderate, and major categories may oversimplify the outcome of each consultation. For example, all medication recommendations, regardless of type, were considered as minor, and recommendations were considered as major only if they resulted in invasive testing or procedures. This approach may underrepresent the impact of consultations as in clinical practice not all high-impact recommendations result in invasive testing or procedures. Despite these important limitations, Bellas et al. present a compelling case for preoperative consultation being associated with delays in surgery.

How then should this study change practice? The authors’ findings tell two separate but intertwined stories. The first is that preoperative consultation leads to delays in surgery. As patients who received preoperative consultation were obviously sicker, and because delays caused by consultation may lead to increased morbidity and mortality, perhaps the solution is to simply fix the delays. However, this approach ignores the more compelling story the authors tell. More important than the delays was the surprising lack of impact of preoperative consultations. Bellas et al. found that the majority of consultations resulted in only minor recommendations, and more importantly, hospitalists rarely changed treatment as a result. Although patients who received consultations were more ill, consultation rarely changed their care or decreased the risk posed by surgery. Bellas et al. found that only patients with active medical conditions had consultations, which resulted in moderate or major recommendations. These findings highlight an opportunity to better identify patients for whom consultation might be helpful and to prevent delays by avoiding consultation for those unlikely to benefit. There have been several efforts in the orthopedic literature to use guidelines for preoperative cardiac testing to guide cardiology consultation.4,5,6 One study using this approach reported findings that were extremely similar to those reported by Bellas et al. in that 71% of preoperative cardiology consultations in their institution did not meet the guideline criteria for invasive cardiac testing.7 The primary difference between the findings of Bellas et al. and the studies in the orthopedic literature is the presence of the comanaging hospitalist. As more and more patients receive hospitalist comanagement prior to inpatient surgery, it is well within the scope of the hospitalist to differentiate chronic risk factors from active or decompensated medical disease requiring a subspecialist. This is in fact much of the value that a hospitalist adds. Avoiding consultation for patients with only elevated chronic risk factors is an important first step in avoiding unnecessary delays to surgery and an opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of the patients they comanage.

The goal of teaching trainees to “never worry alone” is to harness the feelings of uncertainty that all providers face to improve patient care. Knowing when to worry is a valuable lesson, but as with all skills, it should be applied thoughtfully and informed by evidence. Appreciating the risks that surgery poses is quintessential to safe perioperative care, but equally important is understanding that inappropriate consultations can create risks from needless delays and testing. Only in balancing these two concerns, and appreciating when it is appropriate to worry, can we provide the highest quality of care to our patients.

1. Bellas N, Stohler S, Staff I, et al. Impact of preoperative consults and hospitalist comanagement in hip fracture patients. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):16-21. https:doi.org/jhm.3264.

2. Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE, Yeates D. Mortality after admission to hospital with fractured neck of femur: database study. BMJ 2002;325(7369):868-869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7369.868.

3. Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55(3):146-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03016088.

4. Cluett J, Caplan J, Yu W. Preoperative cardiac evaluation of patients with acute hip fracture. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(1):32-36.

5. Smeets SJ, Poeze M, Verbruggen JP. Preoperative cardiac evaluation of geriatric patients with hip fracture. Injury. 2012;43(12):2146-2151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2012.08.007.

6. Siu CW, Sun NC, Lau TW, Yiu KH, Leung F, Tse HF. Preoperative cardiac risk assessment in geriatric patients with hip fractures: an orthopedic surgeons’ perspective. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S587-S591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1393-0.

7. Stitgen A, Poludnianyk K, Dulaney-Cripe E, Markert R, Prayson M. Adherence to preoperative cardiac clearance guidelines in hip fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29(11):500-503. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000381.

“Never worry alone” is a common mantra that most of us have heard throughout medical training. The premise is simple and well meaning. If a patient has an issue that concerns you, ask someone for help. As a student, this can be a resident; as a resident, this can be an attending. However, for hospitalists, the answer is often a subspecialty consultation. Asking for help never seems to be wrong, but what happens when our worry delays appropriate care with unnecessary consultations? In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, authors Bellas et al. have investigated this issue through the lens of subspecialty preoperative consultation for patients admitted to a hospitalist comanagement service with a fragility hip fracture requiring surgery.1

Morbidity and mortality for patients who experience hip fractures are high, and time to appropriate surgery is one of the few modifiable risk factors that may reduce morbidity and mortality.2,3 Bellas et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study to test the association between preoperative subspecialty consultation and multiple clinically relevant outcomes in patients admitted with an acute hip fracture.1 All patients were comanaged by a hospitalist and orthopedic surgery, and “consultation” was defined as any preoperative subspecialty consultation requested by the hospitalist. Outcome measures included time to surgery, length of stay, readmission rate, perioperative complications, and 30-day mortality. In total, 36% (177/491) of patients who underwent surgery received a subspecialty preoperative consultation. Unsurprisingly, these patients were older with higher rates of comorbidity. After controlling for age and Charlson Comorbidity Index, preoperative consultation was associated with dramatic delays and increased rates of time to surgery >24 hours (adjusted odds ratio, 4.2; 95% CI: 2.8-6.6). The authors classified 90% of consultations as appropriate, either because of an active condition (eg, acute coronary syndrome) or because admitting physicians documented a perception that patients were at increased risk. However, 73% of consultations had only minor recommendations, such as ordering an ECG or changing the dose of an existing medication, and only 37% of the time did consultations lead to an identifiable change in management as a result of the consultation.

Although striking, integrating these findings into clinical practice is complex. As a retrospective study, patients who received consultations were obviously different from those who did not. The authors attempted to adjust for this but used only age and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Other factors that are both associated with consultations and known to increase mortality—such as frailty and functional status—were not included in their adjustment. Such unmeasured confounders possibly explain at least some, if not all, of the findings that consultations were associated with a doubling of the likelihood of 30-day mortality. In addition, although the authors assessed the appropriateness of consultation and degree of recommendations, their methods for this deserve scrutiny. Two independent providers adjudicated the consultations with excellent agreement (kappa 0.96 for indication, 0.95 for degree of recommendation), but this reliability assessment was done on previously extracted chart data, probably inflating their agreement statistics. Finally, the adjudication of consultant recommendations into minor, moderate, and major categories may oversimplify the outcome of each consultation. For example, all medication recommendations, regardless of type, were considered as minor, and recommendations were considered as major only if they resulted in invasive testing or procedures. This approach may underrepresent the impact of consultations as in clinical practice not all high-impact recommendations result in invasive testing or procedures. Despite these important limitations, Bellas et al. present a compelling case for preoperative consultation being associated with delays in surgery.

How then should this study change practice? The authors’ findings tell two separate but intertwined stories. The first is that preoperative consultation leads to delays in surgery. As patients who received preoperative consultation were obviously sicker, and because delays caused by consultation may lead to increased morbidity and mortality, perhaps the solution is to simply fix the delays. However, this approach ignores the more compelling story the authors tell. More important than the delays was the surprising lack of impact of preoperative consultations. Bellas et al. found that the majority of consultations resulted in only minor recommendations, and more importantly, hospitalists rarely changed treatment as a result. Although patients who received consultations were more ill, consultation rarely changed their care or decreased the risk posed by surgery. Bellas et al. found that only patients with active medical conditions had consultations, which resulted in moderate or major recommendations. These findings highlight an opportunity to better identify patients for whom consultation might be helpful and to prevent delays by avoiding consultation for those unlikely to benefit. There have been several efforts in the orthopedic literature to use guidelines for preoperative cardiac testing to guide cardiology consultation.4,5,6 One study using this approach reported findings that were extremely similar to those reported by Bellas et al. in that 71% of preoperative cardiology consultations in their institution did not meet the guideline criteria for invasive cardiac testing.7 The primary difference between the findings of Bellas et al. and the studies in the orthopedic literature is the presence of the comanaging hospitalist. As more and more patients receive hospitalist comanagement prior to inpatient surgery, it is well within the scope of the hospitalist to differentiate chronic risk factors from active or decompensated medical disease requiring a subspecialist. This is in fact much of the value that a hospitalist adds. Avoiding consultation for patients with only elevated chronic risk factors is an important first step in avoiding unnecessary delays to surgery and an opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of the patients they comanage.

The goal of teaching trainees to “never worry alone” is to harness the feelings of uncertainty that all providers face to improve patient care. Knowing when to worry is a valuable lesson, but as with all skills, it should be applied thoughtfully and informed by evidence. Appreciating the risks that surgery poses is quintessential to safe perioperative care, but equally important is understanding that inappropriate consultations can create risks from needless delays and testing. Only in balancing these two concerns, and appreciating when it is appropriate to worry, can we provide the highest quality of care to our patients.

“Never worry alone” is a common mantra that most of us have heard throughout medical training. The premise is simple and well meaning. If a patient has an issue that concerns you, ask someone for help. As a student, this can be a resident; as a resident, this can be an attending. However, for hospitalists, the answer is often a subspecialty consultation. Asking for help never seems to be wrong, but what happens when our worry delays appropriate care with unnecessary consultations? In this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, authors Bellas et al. have investigated this issue through the lens of subspecialty preoperative consultation for patients admitted to a hospitalist comanagement service with a fragility hip fracture requiring surgery.1

Morbidity and mortality for patients who experience hip fractures are high, and time to appropriate surgery is one of the few modifiable risk factors that may reduce morbidity and mortality.2,3 Bellas et al. conducted a retrospective cohort study to test the association between preoperative subspecialty consultation and multiple clinically relevant outcomes in patients admitted with an acute hip fracture.1 All patients were comanaged by a hospitalist and orthopedic surgery, and “consultation” was defined as any preoperative subspecialty consultation requested by the hospitalist. Outcome measures included time to surgery, length of stay, readmission rate, perioperative complications, and 30-day mortality. In total, 36% (177/491) of patients who underwent surgery received a subspecialty preoperative consultation. Unsurprisingly, these patients were older with higher rates of comorbidity. After controlling for age and Charlson Comorbidity Index, preoperative consultation was associated with dramatic delays and increased rates of time to surgery >24 hours (adjusted odds ratio, 4.2; 95% CI: 2.8-6.6). The authors classified 90% of consultations as appropriate, either because of an active condition (eg, acute coronary syndrome) or because admitting physicians documented a perception that patients were at increased risk. However, 73% of consultations had only minor recommendations, such as ordering an ECG or changing the dose of an existing medication, and only 37% of the time did consultations lead to an identifiable change in management as a result of the consultation.

Although striking, integrating these findings into clinical practice is complex. As a retrospective study, patients who received consultations were obviously different from those who did not. The authors attempted to adjust for this but used only age and Charlson Comorbidity Index. Other factors that are both associated with consultations and known to increase mortality—such as frailty and functional status—were not included in their adjustment. Such unmeasured confounders possibly explain at least some, if not all, of the findings that consultations were associated with a doubling of the likelihood of 30-day mortality. In addition, although the authors assessed the appropriateness of consultation and degree of recommendations, their methods for this deserve scrutiny. Two independent providers adjudicated the consultations with excellent agreement (kappa 0.96 for indication, 0.95 for degree of recommendation), but this reliability assessment was done on previously extracted chart data, probably inflating their agreement statistics. Finally, the adjudication of consultant recommendations into minor, moderate, and major categories may oversimplify the outcome of each consultation. For example, all medication recommendations, regardless of type, were considered as minor, and recommendations were considered as major only if they resulted in invasive testing or procedures. This approach may underrepresent the impact of consultations as in clinical practice not all high-impact recommendations result in invasive testing or procedures. Despite these important limitations, Bellas et al. present a compelling case for preoperative consultation being associated with delays in surgery.

How then should this study change practice? The authors’ findings tell two separate but intertwined stories. The first is that preoperative consultation leads to delays in surgery. As patients who received preoperative consultation were obviously sicker, and because delays caused by consultation may lead to increased morbidity and mortality, perhaps the solution is to simply fix the delays. However, this approach ignores the more compelling story the authors tell. More important than the delays was the surprising lack of impact of preoperative consultations. Bellas et al. found that the majority of consultations resulted in only minor recommendations, and more importantly, hospitalists rarely changed treatment as a result. Although patients who received consultations were more ill, consultation rarely changed their care or decreased the risk posed by surgery. Bellas et al. found that only patients with active medical conditions had consultations, which resulted in moderate or major recommendations. These findings highlight an opportunity to better identify patients for whom consultation might be helpful and to prevent delays by avoiding consultation for those unlikely to benefit. There have been several efforts in the orthopedic literature to use guidelines for preoperative cardiac testing to guide cardiology consultation.4,5,6 One study using this approach reported findings that were extremely similar to those reported by Bellas et al. in that 71% of preoperative cardiology consultations in their institution did not meet the guideline criteria for invasive cardiac testing.7 The primary difference between the findings of Bellas et al. and the studies in the orthopedic literature is the presence of the comanaging hospitalist. As more and more patients receive hospitalist comanagement prior to inpatient surgery, it is well within the scope of the hospitalist to differentiate chronic risk factors from active or decompensated medical disease requiring a subspecialist. This is in fact much of the value that a hospitalist adds. Avoiding consultation for patients with only elevated chronic risk factors is an important first step in avoiding unnecessary delays to surgery and an opportunity for hospitalists to improve the care of the patients they comanage.

The goal of teaching trainees to “never worry alone” is to harness the feelings of uncertainty that all providers face to improve patient care. Knowing when to worry is a valuable lesson, but as with all skills, it should be applied thoughtfully and informed by evidence. Appreciating the risks that surgery poses is quintessential to safe perioperative care, but equally important is understanding that inappropriate consultations can create risks from needless delays and testing. Only in balancing these two concerns, and appreciating when it is appropriate to worry, can we provide the highest quality of care to our patients.

1. Bellas N, Stohler S, Staff I, et al. Impact of preoperative consults and hospitalist comanagement in hip fracture patients. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):16-21. https:doi.org/jhm.3264.

2. Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE, Yeates D. Mortality after admission to hospital with fractured neck of femur: database study. BMJ 2002;325(7369):868-869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7369.868.

3. Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55(3):146-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03016088.

4. Cluett J, Caplan J, Yu W. Preoperative cardiac evaluation of patients with acute hip fracture. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(1):32-36.

5. Smeets SJ, Poeze M, Verbruggen JP. Preoperative cardiac evaluation of geriatric patients with hip fracture. Injury. 2012;43(12):2146-2151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2012.08.007.

6. Siu CW, Sun NC, Lau TW, Yiu KH, Leung F, Tse HF. Preoperative cardiac risk assessment in geriatric patients with hip fractures: an orthopedic surgeons’ perspective. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S587-S591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1393-0.

7. Stitgen A, Poludnianyk K, Dulaney-Cripe E, Markert R, Prayson M. Adherence to preoperative cardiac clearance guidelines in hip fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29(11):500-503. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000381.

1. Bellas N, Stohler S, Staff I, et al. Impact of preoperative consults and hospitalist comanagement in hip fracture patients. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(1):16-21. https:doi.org/jhm.3264.

2. Goldacre MJ, Roberts SE, Yeates D. Mortality after admission to hospital with fractured neck of femur: database study. BMJ 2002;325(7369):868-869. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7369.868.

3. Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y. Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth. 2008;55(3):146-154. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03016088.

4. Cluett J, Caplan J, Yu W. Preoperative cardiac evaluation of patients with acute hip fracture. Am J Orthop. 2008;37(1):32-36.

5. Smeets SJ, Poeze M, Verbruggen JP. Preoperative cardiac evaluation of geriatric patients with hip fracture. Injury. 2012;43(12):2146-2151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2012.08.007.

6. Siu CW, Sun NC, Lau TW, Yiu KH, Leung F, Tse HF. Preoperative cardiac risk assessment in geriatric patients with hip fractures: an orthopedic surgeons’ perspective. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S587-S591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-010-1393-0.

7. Stitgen A, Poludnianyk K, Dulaney-Cripe E, Markert R, Prayson M. Adherence to preoperative cardiac clearance guidelines in hip fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29(11):500-503. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOT.0000000000000381.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Recommendations on the Use of Ultrasound Guidance for Central and Peripheral Vascular Access in Adults: A Position Statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Approximately five million central venous catheters (CVCs) are inserted in the United States annually, with over 15 million catheter days documented in intensive care units alone.1 Traditional CVC insertion techniques using landmarks are associated with a high risk of mechanical complications, particularly pneumothorax and arterial puncture, which occur in 5%-19% patients.2,3

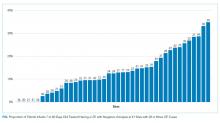

Since the 1990s, several randomized controlled studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that the use of real-time ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion increases procedure success rates and decreases mechanical complications.4,5 Use of real-time ultrasound guidance was recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Institute of Medicine, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and several medical specialty societies in the early 2000s.6-14 Despite these recommendations, ultrasound guidance has not been universally adopted. Currently, an estimated 20%-55% of CVC insertions in the internal jugular vein are performed without ultrasound guidance.15-17

Following the emergence of literature supporting the use of ultrasound guidance for CVC insertion, observational and randomized controlled studies demonstrated improved procedural success rates with the use of ultrasound guidance for the insertion of peripheral intravenous lines (PIVs), arterial catheters, and peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs).18-23

The purpose of this position statement is to present evidence-based recommendations on the use of ultrasound guidance for the insertion of central and peripheral vascular access catheters in adult patients. This document presents consensus-based recommendations with supporting evidence for clinical outcomes, techniques, and training for the use of ultrasound guidance for vascular access. We have subdivided the recommendations on techniques for central venous access, peripheral venous access, and arterial access individually, as some providers may not perform all types of vascular access procedures.

These recommendations are intended for hospitalists and other healthcare providers that routinely place central and peripheral vascular access catheters in acutely ill patients. However, this position statement does not mandate that all hospitalists should place central or peripheral vascular access catheters given the diverse array of hospitalist practice settings. For training and competency assessments, we recognize that some of these recommendations may not be feasible in resource-limited settings, such as rural hospitals, where equipment and staffing for assessments are not available. Recommendations and frameworks for initial and ongoing credentialing of hospitalists in ultrasound-guided bedside procedures have been previously published in an Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) position statement titled, “Credentialing of Hospitalists in Ultrasound-Guided Bedside Procedures.”24

METHODS

Detailed methods are described in Appendix 1. The SHM Point-of-care Ultrasound (POCUS) Task Force was assembled to carry out this guideline development project under the direction of the SHM Board of Directors, Director of Education, and Education Committee. All expert panel members were physicians or advanced practice providers with expertise in POCUS. Expert panel members were divided into working group members, external peer reviewers, and a methodologist. All Task Force members were required to disclose any potential conflicts of interest (Appendix 2). The literature search was conducted in two independent phases. The first phase included literature searches conducted by the vascular access working group members themselves. Key clinical questions and draft recommendations were then prepared. A systematic literature search was conducted by a medical librarian based on the findings of the initial literature search and draft recommendations. The Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and Cochrane medical databases were searched from 1975 to December 2015 initially. Google Scholar was also searched without limiters. An updated search was conducted in November 2017. The literature search strings are included in Appendix 3. All article abstracts were initially screened for relevance by at least two members of the vascular access working group. Full-text versions of screened articles were reviewed, and articles on the use of ultrasound to guide vascular access were selected. The following article types were excluded: non-English language, nonhuman, age <18 years, meeting abstracts, meeting posters, narrative reviews, case reports, letters, and editorials. All relevant systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled studies, and observational studies of ultrasound-guided vascular access were screened and selected (Appendix 3, Figure 1). All full-text articles were shared electronically among the working group members, and final article selection was based on working group consensus. Selected articles were incorporated into the draft recommendations.

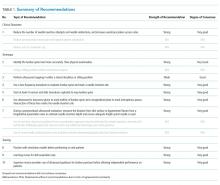

These recommendations were developed using the Research and Development (RAND) Appropriateness Method that required panel judgment and consensus.14 The 28 voting members of the SHM POCUS Task Force reviewed and voted on the draft recommendations considering five transforming factors: (1) Problem priority and importance, (2) Level of quality of evidence, (3) Benefit/harm balance, (4) Benefit/burden balance, and (5) Certainty/concerns about PEAF (Preferences/Equity/Acceptability/Feasibility). Using an internet-based electronic data collection tool (REDCap™), panel members participated in two rounds of electronic voting, one in August 2018 and the other in October 2018 (Appendix 4). Voting on appropriateness was conducted using a nine-point Likert scale. The three zones of the nine-point Likert scale were inappropriate (1-3 points), uncertain (4-6 points), and appropriate (7-9 points). The degree of consensus was assessed using the RAND algorithm (Appendix 1, Figure 1 and Table 1). Establishing a recommendation required at least 70% agreement that a recommendation was “appropriate.” Disagreement was defined as >30% of panelists voting outside of the zone of the median. A strong recommendation required at least 80% of the votes within one integer of the median per the RAND rules.

Recommendations were classified as strong or weak/conditional based on preset rules defining the panel’s level of consensus, which determined the wording for each recommendation (Table 2). The final version of the consensus-based recommendations underwent internal and external review by members of the SHM POCUS Task Force, the SHM Education Committee, and the SHM Executive Committee. The SHM Executive Committee reviewed and approved this position statement prior to its publication in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

RESULTS

Literature Search

A total of 5,563 references were pooled from an initial search performed by a certified medical librarian in December 2015 (4,668 citations) which was updated in November 2017 (791 citations), and from the personal bibliographies and searches (104 citations) performed by working group members. A total of 514 full-text articles were reviewed. The final selection included 192 articles that were abstracted into a data table and incorporated into the draft recommendations. See Appendix 3 for details of the literature search strategy.

Recommendations

Four domains (technique, clinical outcomes, training, and knowledge gaps) with 31 draft recommendations were generated based on a review of the literature. Selected references were abstracted and assigned to each draft recommendation. Rationales for each recommendation cite supporting evidence. After two rounds of panel voting, 31 recommendations achieved agreement based on the RAND rules. During the peer review process, two of the recommendations were merged with other recommendations. Thus, a total of 29 recommendations received final approval. The degree of consensus based on the median score and the dispersion of voting around the median are shown in Appendix 5. Twenty-seven statements were approved as strong recommendations, and two were approved as weak/conditional recommendations. The strength of each recommendation and degree of consensus are summarized in Table 3.

Terminology

Central Venous Catheterization

Central venous catheterization refers to insertion of tunneled or nontunneled large bore vascular catheters that are most commonly inserted into the internal jugular, subclavian, or femoral veins with the catheter tip located in a central vein. These vascular access catheters are synonymously referred to as central lines or central venous catheters (CVCs). Nontunneled catheters are designed for short-term use and should be removed promptly when no longer clinically indicated or after a maximum of 14 days.25

Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter (PICC)

Peripherally inserted central catheters, or PICC lines, are inserted most commonly in the basilic or brachial veins in adult patients, and the catheter tip terminates in the distal superior vena cava or cavo-atrial junction. These catheters are designed to remain in place for a duration of several weeks, as long as it is clinically indicated.

Midline Catheterization

Midline catheters are a type of peripheral venous catheter that are an intermediary between a peripheral intravenous catheter and PICC line. Midline catheters are most commonly inserted in the brachial or basilic veins, but unlike PICC lines, the tips of these catheters terminate in the axillary or subclavian vein. Midline catheters are typically 8 cm to 20 cm in length and inserted for a duration <30 days.

Peripheral Intravenous Catheterization

Peripheral intravenous lines (PIV) refer to small bore venous catheters that are most commonly 14G to 24G and inserted into patients for short-term peripheral venous access. Common sites of ultrasound-guided PIV insertion include the superficial and deep veins of the hand, forearm, and arm.

Arterial Catheterization

Arterial catheters are commonly used for reliable blood pressure monitoring, frequent arterial blood

RECOMMENDATIONS

Preprocedure

1. We recommend that providers should be familiar with the operation of their specific ultrasound machine prior to initiation of a vascular access procedure.

Rationale: There is strong consensus that providers must be familiar with the knobs and functions of the specific make and model of ultrasound machine that will be utilized for a vascular access procedure. Minimizing adjustments to the ultrasound machine during the procedure may reduce the risk of contaminating the sterile field.

2. We recommend that providers should use a high-frequency linear transducer with a sterile sheath and sterile gel to perform vascular access procedures.

Rationale: High-frequency linear-array transducers are recommended for the vast majority of vascular access procedures due to their superior resolution compared to other transducer types. Both central and peripheral vascular access procedures, including PIV, PICC, and arterial line placement, should be performed using sterile technique. A sterile transducer cover and sterile gel must be utilized, and providers must be trained in sterile preparation of the ultrasound transducer.13,26,27

The depth of femoral vessels correlates with body mass index (BMI). When accessing these vessels in a morbidly obese patient with a thigh circumference >60 cm and vessel depth >8 cm, a curvilinear transducer may be preferred for its deeper penetration.28 For patients who are poor candidates for bedside insertion of vascular access catheters, such as uncooperative patients, patients with atypical vascular anatomy or poorly visualized target vessels, we recommend consultation with a vascular access specialist prior to attempting the procedure.

3. We recommend that providers should use two-dimensional ultrasound to evaluate for anatomical variations and absence of vascular thrombosis during preprocedural site selection.

Rationale: A thorough ultrasound examination of the target vessel is warranted prior to catheter placement. Anatomical variations that may affect procedural decision-making are easily detected with ultrasound. A focused vascular ultrasound examination is particularly important in patients who have had temporary or tunneled venous catheters, which can cause stenosis or thrombosis of the target vein.

For internal jugular vein (IJV) CVCs, ultrasound is useful for visualizing the relationship between the IJV and common carotid artery (CCA), particularly in terms of vessel overlap. Furthermore, ultrasound allows for immediate revisualization upon changes in head position.29-32 Troianos et al. found >75% overlap of the IJV and CCA in 54% of all patients and in 64% of older patients (age >60 years) whose heads were rotated to the contralateral side.30 In one study of IJV CVC insertion, inadvertent carotid artery punctures were reduced (3% vs 10%) with the use of ultrasound guidance vs landmarks alone.33 In a cohort of 64 high-risk neurosurgical patients, cannulation success was 100% with the use of ultrasound guidance, and there were no injuries to the carotid artery, even though the procedure was performed with a 30-degree head elevation and anomalous IJV anatomy in 39% of patients.34 In a prospective, randomized controlled study of 1,332 patients, ultrasound-guided cannulation in a neutral position was demonstrated to be as safe as the 45-degree rotated position.35

Ultrasound allows for the recognition of anatomical variations which may influence the selection of the vascular access site or technique. Benter et al. found that 36% of patients showed anatomical variations in the IJV and surrounding tissue.36 Similarly Caridi showed the anatomy of the right IJV to be atypical in 29% of patients,37 and Brusasco found that 37% of bariatric patients had anatomical variations of the IJV.38 In a study of 58 patients, there was significant variability in the IJV position and IJV diameter, ranging from 0.5 cm to >2 cm.39 In a study of hemodialysis patients, 75% of patients had sonographic venous abnormalities that led to a change in venous access approach.40

To detect acute or chronic upper extremity deep venous thrombosis or stenosis, two-dimensional visualization with compression should be part of the ultrasound examination prior to central venous catheterization. In a study of patients that had undergone CVC insertion 9-19 weeks earlier, 50% of patients had an IJV thrombosis or stenosis leading to selection of an alternative site. In this study, use of ultrasound for a preprocedural site evaluation reduced unnecessary attempts at catheterizing an occluded vein.41 At least two other studies demonstrated an appreciable likelihood of thrombosis. In a study of bariatric patients, 8% of patients had asymptomatic thrombosis38 and in another study, 9% of patients being evaluated for hemodialysis catheter placement had asymptomatic IJV thrombosis.37

4. We recommend that providers should evaluate the target blood vessel size and depth during a preprocedural ultrasound evaluation.

Rationale: The size, depth, and anatomic location of central veins can vary considerably. These features are easily discernable using ultrasound. Contrary to traditional teaching, the IJV is located 1 cm anterolateral to the CCA in only about two-thirds of patients.37,39,42,43 Furthermore, the diameter of the IJV can vary significantly, ranging from 0.5 cm to >2 cm.39 The laterality of blood vessels may vary considerably as well. A preprocedural ultrasound evaluation of contralateral subclavian and axillary veins showed a significant absolute difference in cross-sectional area of 26.7 mm2 (P < .001).42

Blood vessels can also shift considerably when a patient is in the Trendelenburg position. In one study, the IJV diameter changed from 11.2 (± 1.5) mm to 15.4 (± 1.5) mm in the supine versus the Trendelenburg position at 15 degrees.33 An observational study demonstrated a frog-legged position with reverse Trendelenburg increased the femoral vein size and reduced the common surface area with the common femoral artery compared to a neutral position. Thus, a frog-legged position with reverse Trendelenburg position may be preferred, since overall catheterization success rates are higher in this position.44

Techniques

General Techniques

5. We recommend that providers should avoid using static ultrasound alone to mark the needle insertion site for vascular access procedures.

Rationale: The use of static ultrasound guidance to mark a needle insertion site is not recommended because normal anatomical relationships of vessels vary, and site marking can be inaccurate with minimal changes in patient position, especially of the neck.43,45,46 Benefits of using ultrasound guidance for vascular access are attained when ultrasound is used to track the needle tip in real-time as it is advanced toward the target vessel.

Although continuous-wave Doppler ultrasound without two-dimensional visualization was used in the past, it is no longer recommended for IJV CVC insertion.47 In a study that randomized patients to IJV CVC insertion with continuous-wave Doppler alone vs two-dimensional ultrasound guidance, the use of two-dimensional ultrasound guidance showed significant improvement in first-pass success rates (97% vs 91%, P = .045), particularly in patients with BMI >30 (97% vs 77%, P = .011).48

A randomized study comparing real-time ultrasound-guided, landmark-based, and ultrasound-marked techniques found higher success rates in the real-time ultrasound-guided group than the other two groups (100% vs 74% vs 73%, respectively; P = .01). The total number of mechanical complications was higher in the landmark-based and ultrasound-marked groups than in the real-time ultrasound-guided group (24% and 36% versus 0%, respectively; P = .01).49 Another randomized controlled study found higher success rates with real-time ultrasound guidance (98%) versus an ultrasound-marked (82%) or landmark-based (64%) approach for central line placement.50

6. We recommend that providers should use real-time (dynamic), two-dimensional ultrasound guidance with a high-frequency linear transducer for CVC insertion, regardless of the provider’s level of experience.

7. We suggest using either a transverse (short-axis) or longitudinal (long-axis) approach when performing real-time ultrasound-guided vascular access procedures.

Rationale: In clinical practice, the phrases transverse, short-axis, or out-of-plane approach are synonymous, as are longitudinal, long-axis, and in-plane approach. The short-axis approach involves tracking the needle tip as it approximates the target vessel with the ultrasound beam oriented in a transverse plane perpendicular to the target vessel. The target vessel is seen as a circular structure on the ultrasound screen as the needle tip approaches the target vessel from above. This approach is also called the out-of-plane technique since the needle passes through the ultrasound plane. The advantages of the short-axis approach include better visualization of adjacent vessels or nerves and the relative ease of skill acquisition for novice operators.9 When using the short-axis approach, extra care must be taken to track the needle tip from the point of insertion on the skin to the target vessel. A disadvantage of the short-axis approach is unintended posterior wall puncture of the target vessel.55

In contrast to a short-axis approach, a long-axis approach is performed with the ultrasound beam aligned parallel to the vessel. The vessel appears as a long tubular structure and the entire needle is visualized as it traverses across the ultrasound screen to approach the target vessel. The long-axis approach is also called an in-plane technique because the needle is maintained within the plane of the ultrasound beam. The advantage of a long-axis approach is the ability to visualize the entire needle as it is inserted into the vessel.14 A randomized crossover study with simulation models compared a long-axis versus short-axis approach for both IJV and subclavian vein catheterization. This study showed decreased number of needle redirections (relative risk (RR) 0.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.3 to 0.7), and posterior wall penetrations (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.9) using a long-axis versus short-axis approach for subclavian vein catheterization.56

A randomized controlled study comparing a long-axis or short-axis approach with ultrasound versus a landmark-based approach for IJV CVC insertion showed higher success rates (100% vs 90%; P < .001), lower insertion time (53 vs 116 seconds; P < .001), and fewer attempts to obtain access (2.5 vs 1.2 attempts, P < .001) with either the long- or short-axis ultrasound approach. The average time to obtain access and number of attempts were comparable between the short-axis and long-axis approaches with ultrasound. The incidence of carotid puncture and hematoma was significantly higher with the landmark-based approach versus either the long- or short-axis ultrasound approach (carotid puncture 17% vs 3%, P = .024; hematoma 23% vs 3%, P = .003).57

High success rates have been reported using a short-axis approach for insertion of PIV lines.58 A prospective, randomized trial compared the short-axis and long-axis approach in patients who had had ≥2 failed PIV insertion attempts. Success rate was 95% (95% CI, 0.85 to 1.00) in the short-axis group compared with 85% (95% CI, 0.69 to 1.00) in the long-axis group. All three subjects with failed PIV placement in the long-axis group had successful rescue placement using a short-axis approach. Furthermore, the short-axis approach was faster than the long-axis approach.59

For radial artery cannulation, limited data exist comparing the short- and long-axis approaches. A randomized controlled study compared a long-axis vs short-axis ultrasound approach for radial artery cannulation. Although the overall procedure success rate was 100% in both groups, the long-axis approach had higher first-pass success rates (1.27 ± 0.4 vs 1.5 ± 0.5, P < .05), shorter cannulation times (24 ± 17 vs 47 ± 34 seconds, P < .05), fewer hematomas (4% vs 43%, P < .05) and fewer posterior wall penetrations (20% vs 56%, P < .05).60

Another technique that has been described for IJV CVC insertion is an oblique-axis approach, a hybrid between the long- and short-axis approaches. In this approach, the transducer is aligned obliquely over the IJV and the needle is inserted using a long-axis or in-plane approach. A prospective randomized trial compared the short-axis, long-axis, and oblique-axis approaches during IJV cannulation. First-pass success rates were 70%, 52%, and 74% with the short-axis, long-axis, and oblique-axis approaches, respectively, and a statistically significant difference was found between the long- and oblique-axis approaches (P = .002). A higher rate of posterior wall puncture was observed with a short-axis approach (15%) compared with the oblique-axis (7%) and long-axis (4%) approaches (P = .047).61

8. We recommend that providers should visualize the needle tip and guidewire in the target vein prior to vessel dilatation.

Rationale: When real-time ultrasound guidance is used, visualization of the needle tip within the vein is the first step to confirm cannulation of the vein and not the artery. After the guidewire is advanced, the provider can use transverse and longitudinal views to reconfirm cannulation of the vein. In a longitudinal view, the guidewire is readily seen positioned within the vein, entering the anterior wall and lying along the posterior wall of the vein. Unintentional perforation of the posterior wall of the vein with entry into the underlying artery can be detected by ultrasound, allowing prompt removal of the needle and guidewire before proceeding with dilation of the vessel. In a prospective observational study that reviewed ultrasound-guided IJV CVC insertions, physicians were able to more readily visualize the guidewire than the needle in the vein.62 A prospective observational study determined that novice operators can visualize intravascular guidewires in simulation models with an overall accuracy of 97%.63

In a retrospective review of CVC insertions where the guidewire position was routinely confirmed in the target vessel prior to dilation, there were no cases of arterial dilation, suggesting confirmation of guidewire position can potentially eliminate the morbidity and mortality associated with arterial dilation during CVC insertion.64

9. To increase the success rate of ultrasound-guided vascular access procedures, we recommend that providers should utilize echogenic needles, plastic needle guides, and/or ultrasound beam steering when available.

Rationale: Echogenic needles have ridged tips that appear brighter on the screen, allowing for better visualization of the needle tip. Plastic needle guides help stabilize the needle alongside the transducer when using either a transverse or longitudinal approach. Although evidence is limited, some studies have reported higher procedural success rates when using echogenic needles, plastic needle guides, and ultrasound beam steering software. In a prospective observational study, Augustides et al. showed significantly higher IJV cannulation rates with versus without use of a needle guide after first (81% vs 69%, P = .0054) and second (93% vs 80%. P = .0001) needle passes.65 A randomized study by Maecken et al. compared subclavian vein CVC insertion with or without use of a needle guide, and found higher procedure success rates within the first and second attempts, reduced time to obtain access (16 seconds vs 30 seconds; P = .0001) and increased needle visibility (86% vs 32%; P < .0001) with the use of a needle guide.66 Another study comparing a short-axis versus long-axis approach with a needle guide showed improved needle visualization using a long-axis approach with a needle guide.67 A randomized study comparing use of a novel, sled-mounted needle guide to a free-hand approach for venous cannulation in simulation models showed the novel, sled-mounted needle guide improved overall success rates and efficiency of cannulation.68

Central Venous Access Techniques

10. We recommend that providers should use a standardized procedure checklist that includes use of real-time ultrasound guidance to reduce the risk of central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) from CVC insertion.

Rationale: A standardized checklist or protocol should be developed to ensure compliance with all recommendations for insertion of CVCs. Evidence-based protocols address periprocedural issues, such as indications for CVC, and procedural techniques, such as use of maximal sterile barrier precautions to reduce the risk of infection. Protocols and checklists that follow established guidelines for CVC insertion have been shown to decrease CLABSI rates.69,70 Similarly, development of checklists and protocols for maintenance of central venous catheters have been effective in reducing CLABSIs.71 Although no externally-validated checklist has been universally accepted or endorsed by national safety organizations, a few internally-validated checklists are available through peer-reviewed publications.72,73 An observational educational cohort of internal medicine residents who received training using simulation of the entire CVC insertion process was able to demonstrate fewer CLABSIs after the simulator-trained residents rotated in the intensive care unit (ICU) (0.50 vs 3.2 infections per 1,000 catheter days, P = .001).74

11. We recommend that providers should use real-time ultrasound guidance, combined with aseptic technique and maximal sterile barrier precautions, to reduce the incidence of infectious complications from CVC insertion.

Rationale: The use of real-time ultrasound guidance for CVC placement has demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in CLABSIs compared to landmark-based techniques.75 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections recommend the use of ultrasound guidance to reduce the number of cannulation attempts and risk of mechanical complications.69 A prospective, three-arm study comparing ultrasound-guided long-axis, short-axis, and landmark-based approaches showed a CLABSI rate of 20% in the landmark-based group versus 10% in each of the ultrasound groups.57 Another randomized study comparing use of ultrasound guidance to a landmark-based technique for IJV CVC insertion demonstrated significantly lower CLABSI rates with the use of ultrasound (2% vs 10%; P < .05).72