User login

Antibiotic Regimens and Associated Outcomes in Children Hospitalized With Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is an exfoliative toxin-mediated dermatitis that predominantly occurs in young children. Multiple recent reports indicate a rising incidence of this disease.1-4 Recommended treatment for SSSS includes antistaphylococcal antibiotics and supportive care measures.5,6 Elimination or reduction of the toxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus is thought to help limit disease progression and promote recovery. Experts advocate for the use of antibiotics even when there is no apparent focal source of infection, such as an abscess.6,7

Several factors may affect antibiotic selection, including the desire to inhibit toxin production and to target the causative pathogen in a bactericidal fashion. Because SSSS is toxin mediated, clindamycin is often recommended because of its inhibition of toxin synthesis.5,8 The clinical utility of adding other antibiotics to clindamycin for coverage of methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA) or methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) is uncertain. Several studies report MSSA to be the predominant pathogen identified by culture2,9; however, SSSS caused by MRSA has been reported.9-11 Additionally, bactericidal antibiotics (eg, nafcillin) have been considered to hold potential clinical advantage as compared with bacteriostatic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin), even though clinical studies have not clearly demonstrated this advantage in the general population.12,13 Some experts recommend additional MRSA or MSSA coverage (such as vancomycin or nafcillin) in patients with high illness severity or nonresponse to therapy, or in areas where there is high prevalence of staphylococcal resistance to clindamycin.5,7,9,14 Alternatively, for areas with low MRSA prevalence, monotherapy with an anti-MSSA antibiotic is another potential option. No recent studies have compared patient outcomes among antibiotic regimens in children with SSSS.

Knowledge of the outcomes associated with different antibiotic regimens for children hospitalized with SSSS is needed and could be used to improve patient outcomes and potentially promote antibiotic stewardship. In this study, our objectives were to (1) describe antibiotic regimens given to children hospitalized with SSSS, and (2) examine the association of three antibiotic regimens commonly used for SSSS (clindamycin monotherapy, clindamycin plus additional MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus additional MRSA coverage) with patient outcomes of length of stay (LOS), treatment failure, and cost in a large cohort of children at US children’s hospitals.

METHODS

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study utilizing data within the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database from July 1, 2011, to June 30, 2016. Thirty-five free-standing tertiary care US children’s hospitals within 24 states were included. The Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas) maintains the PHIS database, which contains de-identified patient information, including diagnoses (with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM]), demographics, procedures, and daily billing records. Data quality and reliability are confirmed by participating institutions and the Children’s Hospital Association.15 The local institutional review board (IRB) deemed the study exempt from formal IRB review, as patient information was de-identified.

Study Population

We included hospitalized children aged newborn to 18 years with a primary or secondary diagnosis of SSSS (ICD-9, 695.81; ICD-10, L00). Children whose primary presentation and admission were to a PHIS hospital were included; children transferred from another hospital were excluded. The following exclusion criteria were based on previously published methodology.16 Children with complex chronic medical conditions as classified by Feudtner et al17 were excluded, since these children may require a different treatment approach than the general pediatric population. In order to decrease diagnostic ambiguity, we excluded children if an alternative dermatologic diagnosis was recorded as a principal or secondary diagnosis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome or scarlet fever).16 Finally, hospitals with fewer than 10 children with SSSS during the study period were excluded.

Antibiotic Regimen Groups

We used PHIS daily billing codes to determine the antibiotics received by the study population. Children were classified into antibiotic regimen groups based on whether they received specific antibiotic combinations. Antibiotics received on any day during the hospitalization, including in the emergency department (ED), were used to assign patients to regimen groups. Antibiotics were classified into regimen groups based on consensus among study investigators, which included two board-certified pediatric infectious diseases specialists (A.C., R.M.). Antibiotic group definitions are listed in Table 1. Oral and intravenous (IV) therapies were grouped together for clindamycin, cephalexin/cefazolin, and linezolid because of good oral bioavailability in most situations.18 The three most common antistaphylococcal groups were chosen for further analysis: clindamycin alone, clindamycin plus MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage. The clindamycin group was defined as children with receipt of oral or IV clindamycin. Children who received clindamycin with additional MSSA coverage, such as cefazolin or nafcillin, were categorized as the clindamycin plus MSSA group. Children who received clindamycin with additional MRSA coverage, such as vancomycin or linezolid, were categorized as the clindamycin plus MRSA group. We chose not to include children who received the above regimens plus other antibiotics with partial antistaphylococcal activity, such as ampicillin, gentamicin, or ceftriaxone, in the clindamycin plus MSSA and clindamycin plus MRSA groups. We excluded these antibiotics to decrease the heterogeneity in the definition of regimen groups and allow a more direct comparison for effectiveness.

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, ethnicity and/or race, payer type, level of care, illness severity, and region. The variable definitions below are in keeping with a prior study of SSSS.16 Age was categorized as: birth to 59 days, 2 to 11 months, 1 to 4 years (preschool age), 5 to 10 years (school age), and 11 to 18 years (adolescent). We examined infants younger than 60 days separately from older infants because this population may warrant additional treatment considerations. Race and ethnicity were categorized as White (non-Hispanic), African American (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, or other. Payer types included government, private, or other. Level of care was assigned as either intensive care or acute care. Illness severity was assigned using the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG; 3M Corporation, St. Paul, Minnesota) severity levels.19 In line with a prior study,16 we defined “low illness severity” as the APR-DRG minor (1) classification. The moderate (2), major (3), and extreme (4) classifications were defined as “moderate to high illness severity,” since there were very few classifications of major or extreme (<5%) illness severity. We categorized hospitals into the following US regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was hospital LOS in days, and secondary outcomes were treatment failure and hospital costs. Hospital LOS was chosen as the primary outcome to represent the time needed for the child to show clinical improvement. Treatment failure was defined as a same-cause 14-day ED revisit or hospital readmission, and these were determined to be same-cause if a diagnosis for SSSS (ICD-9, 695.81; ICD-10, L00) was documented for the return encounter. The 14-day interval for readmission and ED revisit was chosen to measure any relapse of symptoms after completion of antibiotic therapy, similar to a prior study of treatment failure in skin and soft tissue infections.20 Total costs of the hospitalization were estimated from charges using hospital- and year-specific cost-to-charge ratios. Subcategories of cost, including clinical, pharmacy, imaging, laboratory, supply, and other, were also compared among the three groups.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of children were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. These were compared across antibiotic groups using chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis tests, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, outcomes were compared across antibiotic regimen groups using these same statistical tests. In order to account for patient clustering within hospitals, generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to model outcomes with a random intercept for each hospital. Models were adjusted for SSSS being listed as a principal or secondary diagnosis, race, illness severity, and level of care. We log-transformed LOS and cost data prior to modeling because of the nonnormal distributions for these data. Owing to the inability to measure the number of antibiotic doses, and to reduce the possibility of including children who received few regimen-defined combination antibiotics, a post hoc sensitivity analysis was performed. This analysis used an alternative definition for antibiotic regimen groups, for which children admitted for 2 or more calendar days must have received regimen-specified antibiotics on at least 2 days of the admission. Additionally, outcomes were stratified by low and moderate/high illness severity and compared across the three antibiotic regimen groups. All analyses were performed with SAS (SAS 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

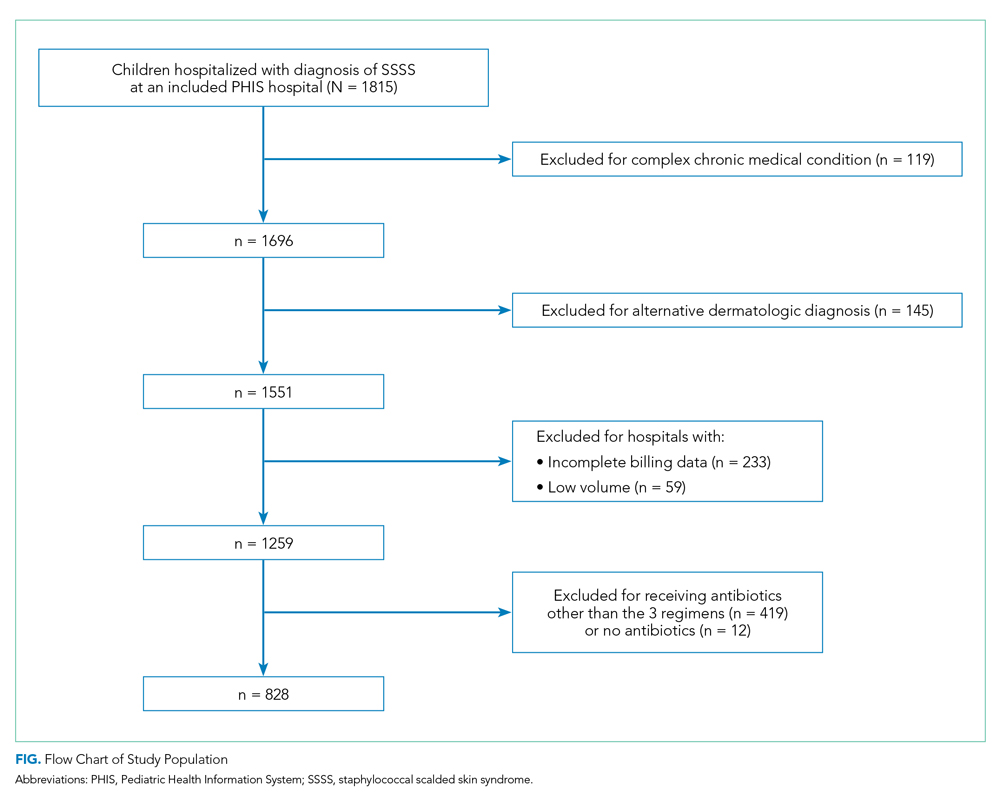

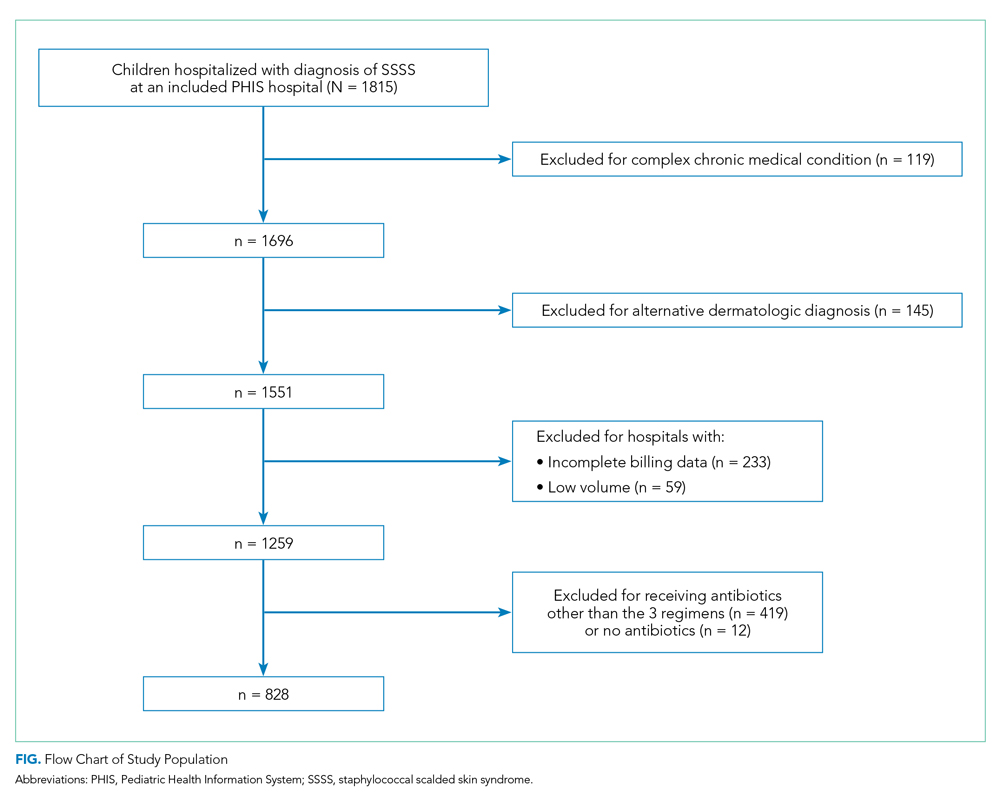

Overall, 1,815 hospitalized children with SSSS were identified in the PHIS database, and after application of the exclusion criteria, 1,259 children remained, with 1,247 (99%) receiving antibiotics (Figure). The antibiotic regimens received by these children are described in Table 1. Of these, 828 children (66%) received one of the three most common antistaphylococcal regimens (clindamycin, clindamycin + MSSA, and clindamycin + MRSA) and were included for further analysis.

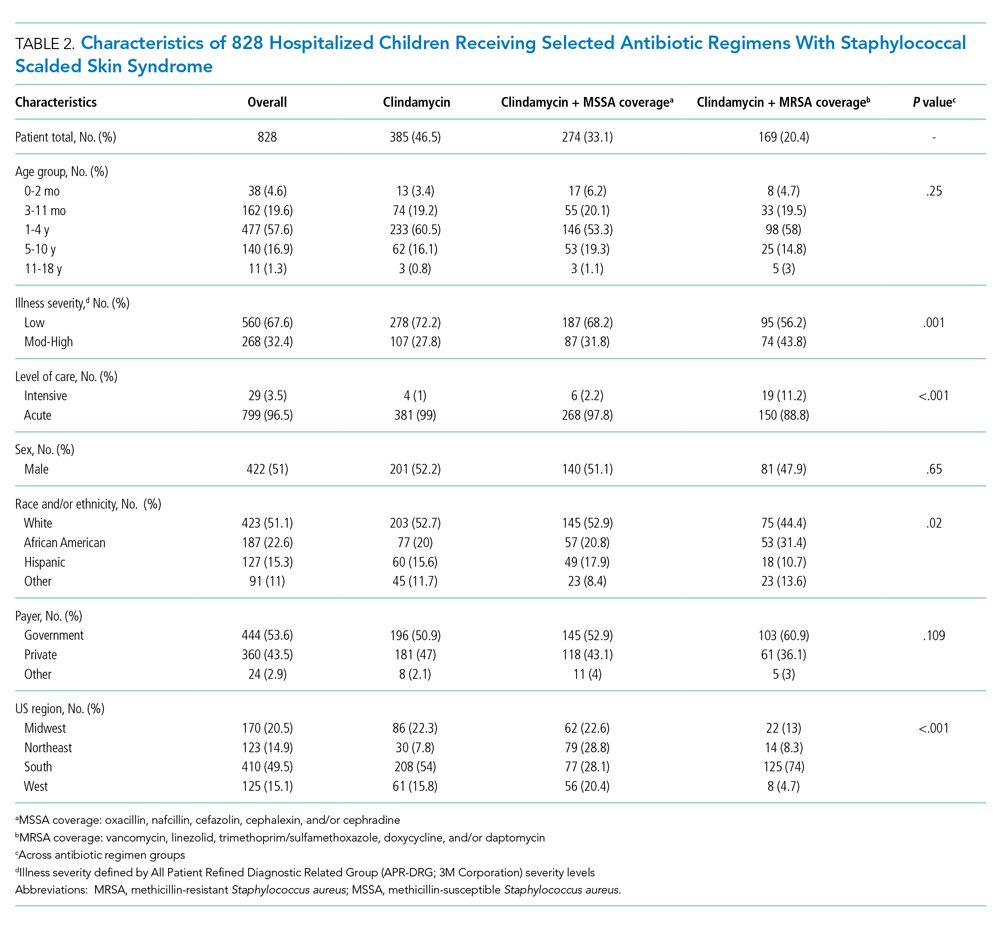

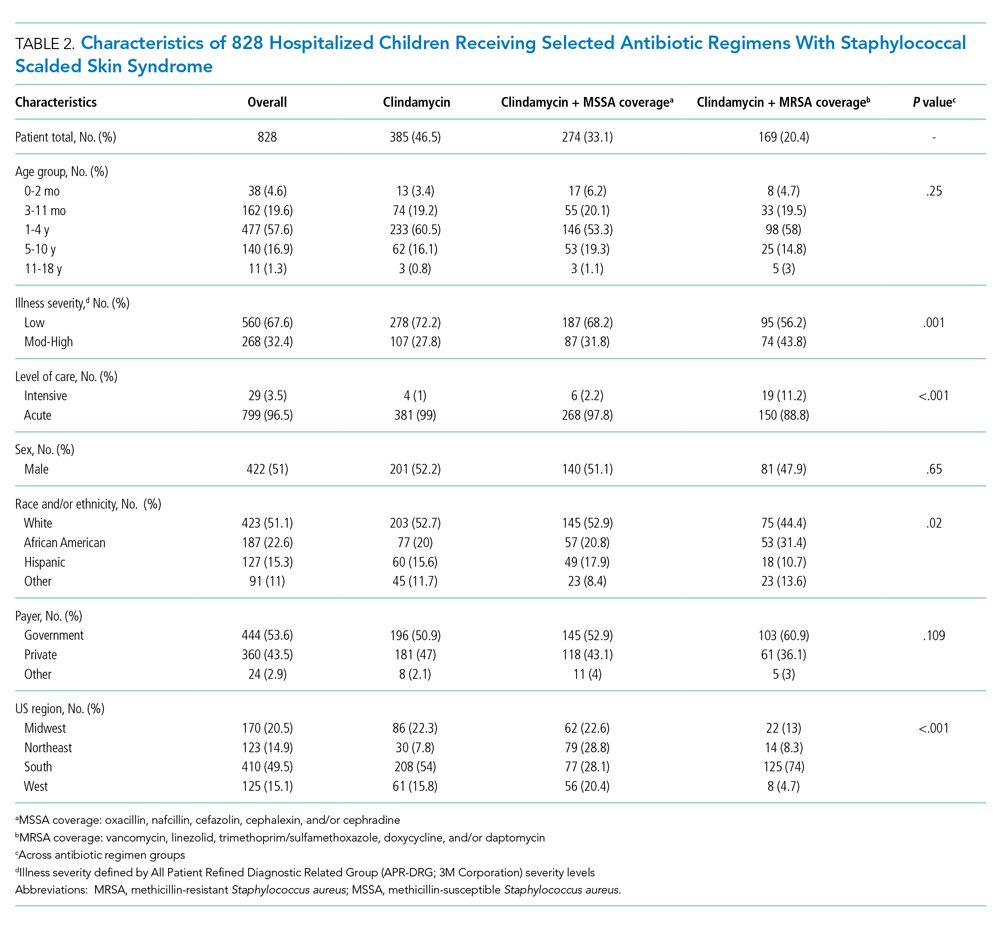

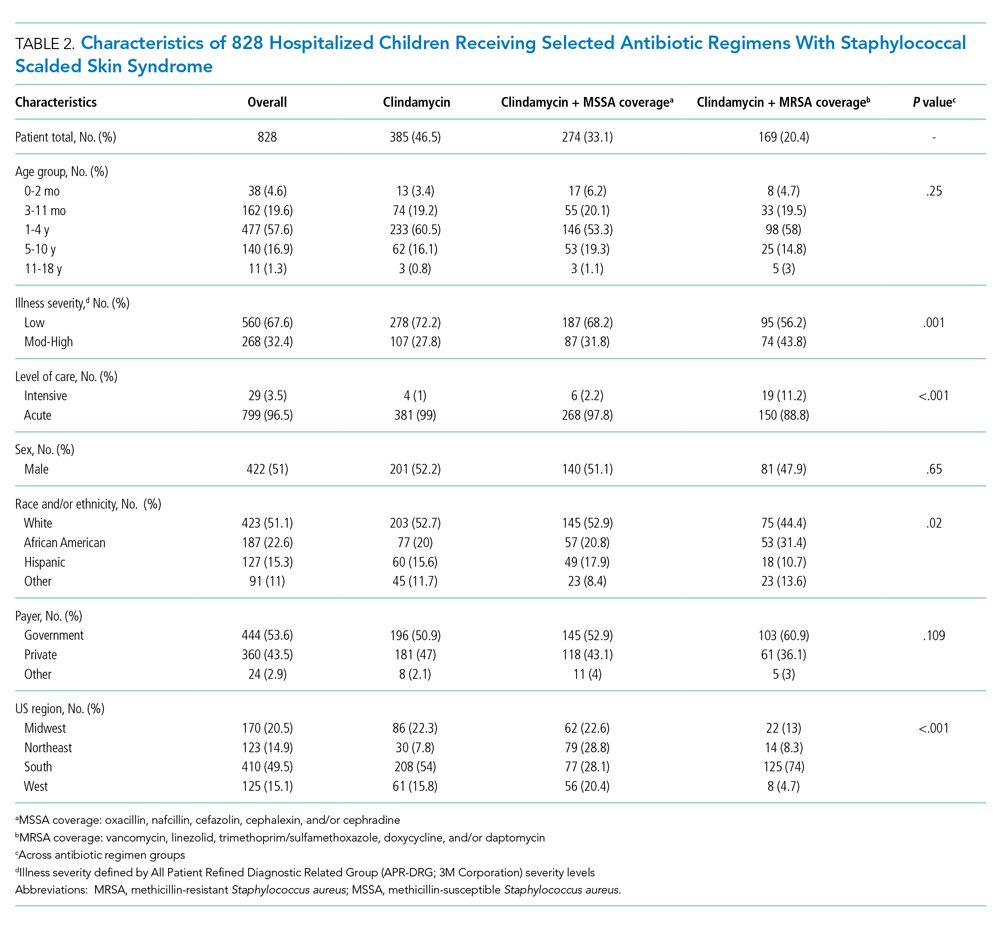

Characteristics of the 828 children are presented in Table 2. Most children (82%) were aged 4 years or younger, and distributions of age, sex, and insurance payer were similar among children receiving the three regimens. Thirty-two percent had moderate to high illness severity, and 3.5% required management in the intensive care setting. Of the three antibiotic regimens, clindamycin monotherapy was most common (47%), followed by clindamycin plus MSSA coverage (33%), and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage (20%). A higher proportion of children in the clindamycin plus MRSA group were African American and were hospitalized in the South. Children receiving clindamycin plus MRSA coverage had higher illness severity (44%) as compared with clindamycin monotherapy (28%) and clindamycin plus MSSA coverage (32%) (P = .001). Additionally, a larger proportion of children treated with clindamycin plus MRSA coverage were managed in the intensive care setting as compared with the clindamycin plus MSSA or clindamycin monotherapy groups.

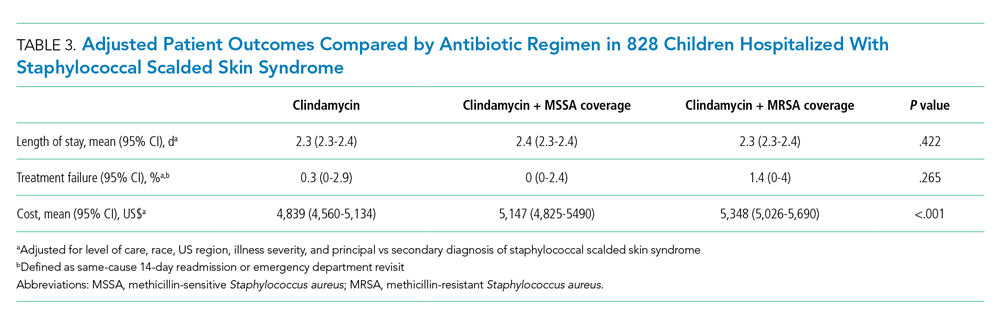

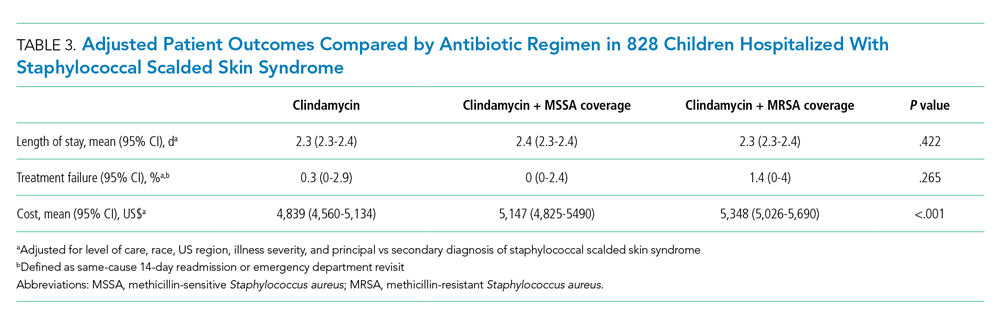

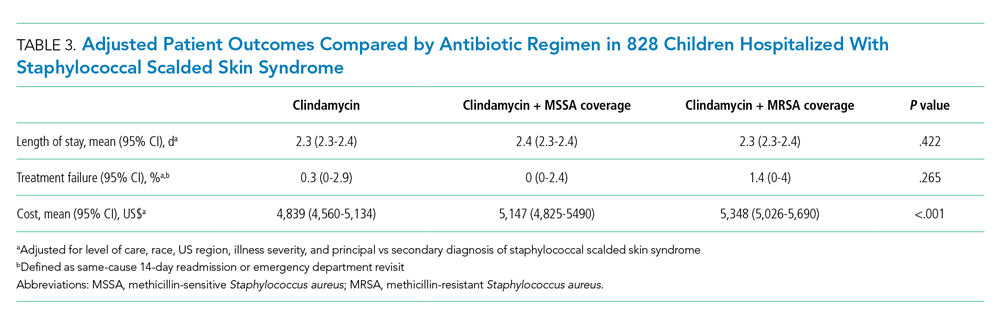

Among the 828 children with SSSS, the median LOS was 2 days (IQR, 2-3), and treatment failure was 1.1% (95% CI, 0.4-1.8). After adjustment for illness severity, race, payer, and region (Table 3), the three antibiotic regimens were not associated with significant differences in LOS or treatment failure. Costs were significantly different among the three antibiotic regimens. Clindamycin plus MRSA coverage was associated with the greatest costs, whereas clindamycin monotherapy was associated with the lowest costs (mean, $5,348 vs $4,839, respectively; P < .001) (Table 3). In a sensitivity analysis using an alternative antibiotic regimen definition, we found results in line with the primary analysis, with no statistically significant differences in LOS (P = .44) or treatment failure (P = .54), but significant differences in cost (P < .001). Additionally, the same findings were present for LOS, treatment failure, and cost when outcomes were stratified by illness severity (Appendix Table). However, significant contributors to the higher cost in the clindamycin plus MRSA group did vary by illness severity stratification. Laboratory, supply, and pharmacy cost categories differed significantly among antibiotic groups for the low illness severity strata, whereas pharmacy was the only significant cost category difference in moderate/high illness severity.

DISCUSSION

Clindamycin monotherapy, clindamycin plus MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage are the most commonly administered antistaphylococcal antibiotic regimens for children hospitalized with SSSS at US children’s hospitals. Our multicenter study found that, across these antistaphylococcal antibiotic regimens, there were no associated differences in hospital LOS or treatment failure. However, the antibiotic regimens were associated with significant differences in overall hospital costs. These findings suggest that the use of clindamycin with additional MSSA or MRSA antibiotic coverage for children with SSSS may not be associated with additional clinical benefit, as compared with clindamycin monotherapy, and could potentially be more costly.

Prior literature describing LOS in relation to antibiotic use for children with SSSS is limited. Authors of a recent case series of 21 children in Philadelphia reported approximately 50% of children received clindamycin monotherapy or combination therapy, but patient outcomes such as LOS were not described.9 Clindamycin use and outcomes have been described in smaller studies and case reports of SSSS, which reported positive outcomes such as patient recovery and lack of disease recurrence.2,9,21 A small retrospective, comparative effectiveness study of 30 neonates with SSSS examined beta-lactamase–resistant penicillin use with and without cephalosporins. They found no effect on LOS, but findings were limited by a small sample size.22 Our study cohort included relatively few neonates, and thus our findings may not be applicable to this population subgroup. We chose not to include regimens with third-generation cephalosporins or ampicillin, which may have limited the number of included neonates, because these antibiotics are frequently administered during evaluation for invasive bacterial infections.23 We found a very low occurrence of treatment failure in our study cohort across all three groups, which is consistent with other studies of SSSS that report an overall good prognosis and low recurrence and/or readmission rates.6,16,24 The low prevalence of treatment failure, however, precluded our ability to detect small differences among antibiotic regimen groups that may exist.

We observed that cost differed significantly across antibiotic regimen groups, with lowest cost associated with clindamycin monotherapy in adjusted analysis despite similar LOS. Even with our illness-severity adjustment, there may have been other unmeasured factors resulting in the higher cost associated with the combination groups. Hence, we also examined cost breakdown with a stratified analysis by illness severity. We found that pharmacy costs were significantly different among antibiotic groups in both illness severity strata, whereas those with low illness severity also differed by laboratory and supply costs. Thus, pharmacy cost differences may be the largest driver in the cost differential among groups. Lower cost in the clindamycin monotherapy group is likely due to administration of a single antibiotic. The reason for supply and laboratory cost differences is uncertain, but higher cost in the clindamycin plus MRSA group could possibly be from laboratory testing related to drug monitoring (eg, renal function testing or drug levels). While other studies have reported costs for hospitalized children with SSSS associated with different patient characteristics or diagnostic testing,1,16 to our knowledge, no other studies have reported cost related to antibiotic regimens for SSSS. As healthcare reimbursements shift to value-based models, identifying treatment regimens with equal efficacy but lower cost will become increasingly important. Future studies should also examine other covariates and outcomes, such as oral vs parenteral antibiotic use, use of monitoring laboratories related to antibiotic choice, and adverse drug effects.

Several strengths and additional limitations apply to our study. Our study is one of the few to describe outcomes associated with antibiotic regimens for children with SSSS. With the PHIS database, we were able to include a large number of children with SSSS from children’s hospitals across the United States. Although the PHIS database affords these strengths, there are limitations inherent to administrative data. Children with SSSS were identified by documented ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes, which might lead to misclassification. However, misclassification is less likely because only one ICD-9 and ICD-10 code exists for SSSS, and the characteristics of this condition are specific. Also, diagnostic codes for other dermatologic conditions (eg, scarlet fever) were excluded to further reduce the chance of misclassification. A limitation to our use of PHIS billing codes was the inability to confirm the dosage of antibiotics given, the number of doses, or whether antibiotics were prescribed upon discharge. Another limitation is that children whose antibiotic therapy was changed during hospitalization (eg, from clindamycin monotherapy to cefazolin monotherapy) were categorized into the combination groups. However, the sensitivity analysis performed based on a stricter antibiotic group definition (receipt of both antibiotics on at least 2 calendar days) did not alter the outcomes, which is reassuring. We were unable to assess the use of targeted antibiotic therapy because clinical data (eg, microbiology results) were not available. However, this may be less important because some literature suggests that cultures for S aureus are obtained infrequently2 and may be difficult to interpret when obtained,25 since culture growth can represent colonization rather than causative strains. An additional limitation is that administrative data do not include certain clinical outcomes, such as fever duration or degree of skin involvement, which could have differed among the groups. Last, the PHIS database only captures revisits or readmissions to PHIS hospitals, and so we are unable to exclude the possibility of a child being seen at or readmitted to another hospital.

Due to the observational design of this study and potential for incomplete measurement of illness severity, we recommend a future prospective trial with randomization to confirm these findings. One possible reason that LOS did not differ among groups is that the burden of clindamycin-resistant strains in our cohort could be low, and the addition of MSSA or MRSA coverage does not result in a clinically important increase in S aureus coverage. However, pooled pediatric hospital antibiogram data suggest the overall rate of clindamycin resistance is close to 20% in hospitals located in all US regions.26 Limited studies also suggest that MSSA may be the predominant pathogen associated with SSSS.2,9 To address this, future randomized trials could compare the effectiveness of clindamycin monotherapy to MSSA-specific agents like cefazolin or nafcillin. Unfortunately, anti-MSSA monotherapy was not evaluated in our study because very few children received this treatment. Using monotherapy as opposed to multiple antibiotics has the potential to promote antibiotic stewardship for antistaphylococcal antibiotics in the management of SSSS. Reducing unnecessary antibiotic use not only potentially affects antibiotic resistance, but could also benefit patients in reducing possible side effects, cost, and IV catheter complications.27 However, acknowledging our study limitations, our findings should be applied cautiously in clinical settings, in the context of local antibiogram data, individual culture results, and specific patient factors. The local clindamycin resistance rate for both MSSA and MRSA should be considered. Many antibiotics chosen to treat MRSA—such as vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole—will also have anti-MSSA activity and may have lower local resistance rates than clindamycin. Practitioners may also consider how each antibiotic kills bacteria; for example, beta-lactams rely on bacterial replication, but clindamycin does not. Each factor should influence how empiric treatment, whether monotherapy or combination, is chosen for children with SSSS.

CONCLUSION

In this large, multicenter cohort of hospitalized children with SSSS, we found that the addition of MSSA or MRSA coverage to clindamycin monotherapy was not associated with differences in outcomes of hospital LOS and treatment failure. Furthermore, clindamycin monotherapy was associated with lower overall cost. Prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these findings and assess whether clindamycin monotherapy, monotherapy with an anti-MSSA antibiotic, or alternative regimens are most effective for treatment of children with SSSS.

1. Staiman A, Hsu DY, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in United States children. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):704-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16097

2. Hulten KG, Kok M, King KE, Lamberth LB, Kaplan SL. Increasing numbers of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome cases caused by ST121 in Houston, TX. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(1):30-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002499

3. Arnold JD, Hoek SN, Kirkorian AY. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in the United States: A cross-sectional study, 2010-2014. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):404-406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.023

4. Hayward A, Knott F, Petersen I, et al. Increasing hospitalizations and general practice prescriptions for community-onset staphylococcal disease, England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(5):720-726. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.070153

5. Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. MRSA, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other cutaneous bacterial emergencies. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39(10):627-633. https://doi.org/10.3928/00904481-20100922-02

6. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, Evans RW, Poston SM. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(2):224-242.

7. Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(11):1418-1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12541

8. Hodille E, Rose W, Diep BA, Goutelle S, Lina G, Dumitrescu O. The role of antibiotics in modulating virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(4):887-917. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00120-16

9. Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, McGowan KL, Yan AC, Treat JR. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(3):305-308. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12195

10. Yamaguchi T, Yokota Y, Terajima J, et al. Clonal association of Staphylococcus aureus causing bullous impetigo and the emergence of new methicillin-resistant clonal groups in Kansai district in Japan. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(10):1511-1516. https://doi.org/10.1086/340212

11. Noguchi N, Nakaminami H, Nishijima S, Kurokawa I, So H, Sasatsu M. Antimicrobial agent of susceptibilities and antiseptic resistance gene distribution among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2119-2125. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02690-05

12. Pankey GA, Sabath LD. Clinical relevance of bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms of action in the treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(6):864-870. https://doi.org/10.1086/381972

13. Wald-Dickler N, Holtom P, Spellberg B. Busting the myth of “static vs cidal”: a systemic literature review. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(9):1470-1474. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix1127

14. Ladhani S, Joannou CL. Difficulties in diagnosis and management of the staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(9):819-821. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-200009000-00002

15. Mongelluzzo J, Mohamad Z, Ten Have TR, Shah SS. Corticosteroids and mortality in children with bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2048-2055. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.299.17.2048

16. Neubauer HC, Hall M, Wallace SS, et al. Variation in diagnostic test use and associated outcomes in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome at children’s hospitals. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(9):530-537. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0032

17. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199

18. Sauberan JS, Bradley JS. Antimicrobial agents. In: Long SS, ed. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Elsevier; 2018:1499-1531.

19. Sedman AB, Bahl V, Bunting E, et al. Clinical redesign using all patient refined diagnosis related groups. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):965-969. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0650

20. Williams DJ, Cooper WO, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antibiotic treatment strategies for pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e479-487. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3681

21. Haasnoot PJ, De Vries A. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in a 4-year-old child: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12(1):20. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13256-017-1533-7

22. Li MY, Hua Y, Wei GH, Qiu L. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: an 8-year retrospective study in a single institution. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(1):43-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12114

23. Markham JL, Hall M, Queen MA, et al. Variation in antibiotic selection and clinical outcomes in infants <60 days hospitalized with skin and soft tissue infections. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(1):30-38. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0237

24. Davidson J, Polly S, Hayes PJ, Fisher KR, Talati AJ, Patel T. Recurrent staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an extremely low-birth-weight neonate. AJP Rep. 2017;7(2):e134-e137. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1603971

25. Ladhani S, Robbie S, Chapple DS, Joannou CL, Evans RW. Isolating Staphylococcus aureus from children with suspected Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is not clinically useful. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(3):284-286.

26. Tamma PD, Robinson GL, Gerber JS, et al. Pediatric antimicrobial susceptibility trends across the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(12):1244-1251. https://doi.org/10.1086/673974

27. Unbeck M, Forberg U, Ygge BM, Ehrenberg A, Petzold M, Johansson E. Peripheral venous catheter related complications are common among paediatric and neonatal patients. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(6):566-574. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12963

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is an exfoliative toxin-mediated dermatitis that predominantly occurs in young children. Multiple recent reports indicate a rising incidence of this disease.1-4 Recommended treatment for SSSS includes antistaphylococcal antibiotics and supportive care measures.5,6 Elimination or reduction of the toxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus is thought to help limit disease progression and promote recovery. Experts advocate for the use of antibiotics even when there is no apparent focal source of infection, such as an abscess.6,7

Several factors may affect antibiotic selection, including the desire to inhibit toxin production and to target the causative pathogen in a bactericidal fashion. Because SSSS is toxin mediated, clindamycin is often recommended because of its inhibition of toxin synthesis.5,8 The clinical utility of adding other antibiotics to clindamycin for coverage of methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA) or methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) is uncertain. Several studies report MSSA to be the predominant pathogen identified by culture2,9; however, SSSS caused by MRSA has been reported.9-11 Additionally, bactericidal antibiotics (eg, nafcillin) have been considered to hold potential clinical advantage as compared with bacteriostatic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin), even though clinical studies have not clearly demonstrated this advantage in the general population.12,13 Some experts recommend additional MRSA or MSSA coverage (such as vancomycin or nafcillin) in patients with high illness severity or nonresponse to therapy, or in areas where there is high prevalence of staphylococcal resistance to clindamycin.5,7,9,14 Alternatively, for areas with low MRSA prevalence, monotherapy with an anti-MSSA antibiotic is another potential option. No recent studies have compared patient outcomes among antibiotic regimens in children with SSSS.

Knowledge of the outcomes associated with different antibiotic regimens for children hospitalized with SSSS is needed and could be used to improve patient outcomes and potentially promote antibiotic stewardship. In this study, our objectives were to (1) describe antibiotic regimens given to children hospitalized with SSSS, and (2) examine the association of three antibiotic regimens commonly used for SSSS (clindamycin monotherapy, clindamycin plus additional MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus additional MRSA coverage) with patient outcomes of length of stay (LOS), treatment failure, and cost in a large cohort of children at US children’s hospitals.

METHODS

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study utilizing data within the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database from July 1, 2011, to June 30, 2016. Thirty-five free-standing tertiary care US children’s hospitals within 24 states were included. The Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas) maintains the PHIS database, which contains de-identified patient information, including diagnoses (with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM]), demographics, procedures, and daily billing records. Data quality and reliability are confirmed by participating institutions and the Children’s Hospital Association.15 The local institutional review board (IRB) deemed the study exempt from formal IRB review, as patient information was de-identified.

Study Population

We included hospitalized children aged newborn to 18 years with a primary or secondary diagnosis of SSSS (ICD-9, 695.81; ICD-10, L00). Children whose primary presentation and admission were to a PHIS hospital were included; children transferred from another hospital were excluded. The following exclusion criteria were based on previously published methodology.16 Children with complex chronic medical conditions as classified by Feudtner et al17 were excluded, since these children may require a different treatment approach than the general pediatric population. In order to decrease diagnostic ambiguity, we excluded children if an alternative dermatologic diagnosis was recorded as a principal or secondary diagnosis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome or scarlet fever).16 Finally, hospitals with fewer than 10 children with SSSS during the study period were excluded.

Antibiotic Regimen Groups

We used PHIS daily billing codes to determine the antibiotics received by the study population. Children were classified into antibiotic regimen groups based on whether they received specific antibiotic combinations. Antibiotics received on any day during the hospitalization, including in the emergency department (ED), were used to assign patients to regimen groups. Antibiotics were classified into regimen groups based on consensus among study investigators, which included two board-certified pediatric infectious diseases specialists (A.C., R.M.). Antibiotic group definitions are listed in Table 1. Oral and intravenous (IV) therapies were grouped together for clindamycin, cephalexin/cefazolin, and linezolid because of good oral bioavailability in most situations.18 The three most common antistaphylococcal groups were chosen for further analysis: clindamycin alone, clindamycin plus MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage. The clindamycin group was defined as children with receipt of oral or IV clindamycin. Children who received clindamycin with additional MSSA coverage, such as cefazolin or nafcillin, were categorized as the clindamycin plus MSSA group. Children who received clindamycin with additional MRSA coverage, such as vancomycin or linezolid, were categorized as the clindamycin plus MRSA group. We chose not to include children who received the above regimens plus other antibiotics with partial antistaphylococcal activity, such as ampicillin, gentamicin, or ceftriaxone, in the clindamycin plus MSSA and clindamycin plus MRSA groups. We excluded these antibiotics to decrease the heterogeneity in the definition of regimen groups and allow a more direct comparison for effectiveness.

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, ethnicity and/or race, payer type, level of care, illness severity, and region. The variable definitions below are in keeping with a prior study of SSSS.16 Age was categorized as: birth to 59 days, 2 to 11 months, 1 to 4 years (preschool age), 5 to 10 years (school age), and 11 to 18 years (adolescent). We examined infants younger than 60 days separately from older infants because this population may warrant additional treatment considerations. Race and ethnicity were categorized as White (non-Hispanic), African American (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, or other. Payer types included government, private, or other. Level of care was assigned as either intensive care or acute care. Illness severity was assigned using the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG; 3M Corporation, St. Paul, Minnesota) severity levels.19 In line with a prior study,16 we defined “low illness severity” as the APR-DRG minor (1) classification. The moderate (2), major (3), and extreme (4) classifications were defined as “moderate to high illness severity,” since there were very few classifications of major or extreme (<5%) illness severity. We categorized hospitals into the following US regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was hospital LOS in days, and secondary outcomes were treatment failure and hospital costs. Hospital LOS was chosen as the primary outcome to represent the time needed for the child to show clinical improvement. Treatment failure was defined as a same-cause 14-day ED revisit or hospital readmission, and these were determined to be same-cause if a diagnosis for SSSS (ICD-9, 695.81; ICD-10, L00) was documented for the return encounter. The 14-day interval for readmission and ED revisit was chosen to measure any relapse of symptoms after completion of antibiotic therapy, similar to a prior study of treatment failure in skin and soft tissue infections.20 Total costs of the hospitalization were estimated from charges using hospital- and year-specific cost-to-charge ratios. Subcategories of cost, including clinical, pharmacy, imaging, laboratory, supply, and other, were also compared among the three groups.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of children were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. These were compared across antibiotic groups using chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis tests, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, outcomes were compared across antibiotic regimen groups using these same statistical tests. In order to account for patient clustering within hospitals, generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to model outcomes with a random intercept for each hospital. Models were adjusted for SSSS being listed as a principal or secondary diagnosis, race, illness severity, and level of care. We log-transformed LOS and cost data prior to modeling because of the nonnormal distributions for these data. Owing to the inability to measure the number of antibiotic doses, and to reduce the possibility of including children who received few regimen-defined combination antibiotics, a post hoc sensitivity analysis was performed. This analysis used an alternative definition for antibiotic regimen groups, for which children admitted for 2 or more calendar days must have received regimen-specified antibiotics on at least 2 days of the admission. Additionally, outcomes were stratified by low and moderate/high illness severity and compared across the three antibiotic regimen groups. All analyses were performed with SAS (SAS 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Overall, 1,815 hospitalized children with SSSS were identified in the PHIS database, and after application of the exclusion criteria, 1,259 children remained, with 1,247 (99%) receiving antibiotics (Figure). The antibiotic regimens received by these children are described in Table 1. Of these, 828 children (66%) received one of the three most common antistaphylococcal regimens (clindamycin, clindamycin + MSSA, and clindamycin + MRSA) and were included for further analysis.

Characteristics of the 828 children are presented in Table 2. Most children (82%) were aged 4 years or younger, and distributions of age, sex, and insurance payer were similar among children receiving the three regimens. Thirty-two percent had moderate to high illness severity, and 3.5% required management in the intensive care setting. Of the three antibiotic regimens, clindamycin monotherapy was most common (47%), followed by clindamycin plus MSSA coverage (33%), and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage (20%). A higher proportion of children in the clindamycin plus MRSA group were African American and were hospitalized in the South. Children receiving clindamycin plus MRSA coverage had higher illness severity (44%) as compared with clindamycin monotherapy (28%) and clindamycin plus MSSA coverage (32%) (P = .001). Additionally, a larger proportion of children treated with clindamycin plus MRSA coverage were managed in the intensive care setting as compared with the clindamycin plus MSSA or clindamycin monotherapy groups.

Among the 828 children with SSSS, the median LOS was 2 days (IQR, 2-3), and treatment failure was 1.1% (95% CI, 0.4-1.8). After adjustment for illness severity, race, payer, and region (Table 3), the three antibiotic regimens were not associated with significant differences in LOS or treatment failure. Costs were significantly different among the three antibiotic regimens. Clindamycin plus MRSA coverage was associated with the greatest costs, whereas clindamycin monotherapy was associated with the lowest costs (mean, $5,348 vs $4,839, respectively; P < .001) (Table 3). In a sensitivity analysis using an alternative antibiotic regimen definition, we found results in line with the primary analysis, with no statistically significant differences in LOS (P = .44) or treatment failure (P = .54), but significant differences in cost (P < .001). Additionally, the same findings were present for LOS, treatment failure, and cost when outcomes were stratified by illness severity (Appendix Table). However, significant contributors to the higher cost in the clindamycin plus MRSA group did vary by illness severity stratification. Laboratory, supply, and pharmacy cost categories differed significantly among antibiotic groups for the low illness severity strata, whereas pharmacy was the only significant cost category difference in moderate/high illness severity.

DISCUSSION

Clindamycin monotherapy, clindamycin plus MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage are the most commonly administered antistaphylococcal antibiotic regimens for children hospitalized with SSSS at US children’s hospitals. Our multicenter study found that, across these antistaphylococcal antibiotic regimens, there were no associated differences in hospital LOS or treatment failure. However, the antibiotic regimens were associated with significant differences in overall hospital costs. These findings suggest that the use of clindamycin with additional MSSA or MRSA antibiotic coverage for children with SSSS may not be associated with additional clinical benefit, as compared with clindamycin monotherapy, and could potentially be more costly.

Prior literature describing LOS in relation to antibiotic use for children with SSSS is limited. Authors of a recent case series of 21 children in Philadelphia reported approximately 50% of children received clindamycin monotherapy or combination therapy, but patient outcomes such as LOS were not described.9 Clindamycin use and outcomes have been described in smaller studies and case reports of SSSS, which reported positive outcomes such as patient recovery and lack of disease recurrence.2,9,21 A small retrospective, comparative effectiveness study of 30 neonates with SSSS examined beta-lactamase–resistant penicillin use with and without cephalosporins. They found no effect on LOS, but findings were limited by a small sample size.22 Our study cohort included relatively few neonates, and thus our findings may not be applicable to this population subgroup. We chose not to include regimens with third-generation cephalosporins or ampicillin, which may have limited the number of included neonates, because these antibiotics are frequently administered during evaluation for invasive bacterial infections.23 We found a very low occurrence of treatment failure in our study cohort across all three groups, which is consistent with other studies of SSSS that report an overall good prognosis and low recurrence and/or readmission rates.6,16,24 The low prevalence of treatment failure, however, precluded our ability to detect small differences among antibiotic regimen groups that may exist.

We observed that cost differed significantly across antibiotic regimen groups, with lowest cost associated with clindamycin monotherapy in adjusted analysis despite similar LOS. Even with our illness-severity adjustment, there may have been other unmeasured factors resulting in the higher cost associated with the combination groups. Hence, we also examined cost breakdown with a stratified analysis by illness severity. We found that pharmacy costs were significantly different among antibiotic groups in both illness severity strata, whereas those with low illness severity also differed by laboratory and supply costs. Thus, pharmacy cost differences may be the largest driver in the cost differential among groups. Lower cost in the clindamycin monotherapy group is likely due to administration of a single antibiotic. The reason for supply and laboratory cost differences is uncertain, but higher cost in the clindamycin plus MRSA group could possibly be from laboratory testing related to drug monitoring (eg, renal function testing or drug levels). While other studies have reported costs for hospitalized children with SSSS associated with different patient characteristics or diagnostic testing,1,16 to our knowledge, no other studies have reported cost related to antibiotic regimens for SSSS. As healthcare reimbursements shift to value-based models, identifying treatment regimens with equal efficacy but lower cost will become increasingly important. Future studies should also examine other covariates and outcomes, such as oral vs parenteral antibiotic use, use of monitoring laboratories related to antibiotic choice, and adverse drug effects.

Several strengths and additional limitations apply to our study. Our study is one of the few to describe outcomes associated with antibiotic regimens for children with SSSS. With the PHIS database, we were able to include a large number of children with SSSS from children’s hospitals across the United States. Although the PHIS database affords these strengths, there are limitations inherent to administrative data. Children with SSSS were identified by documented ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes, which might lead to misclassification. However, misclassification is less likely because only one ICD-9 and ICD-10 code exists for SSSS, and the characteristics of this condition are specific. Also, diagnostic codes for other dermatologic conditions (eg, scarlet fever) were excluded to further reduce the chance of misclassification. A limitation to our use of PHIS billing codes was the inability to confirm the dosage of antibiotics given, the number of doses, or whether antibiotics were prescribed upon discharge. Another limitation is that children whose antibiotic therapy was changed during hospitalization (eg, from clindamycin monotherapy to cefazolin monotherapy) were categorized into the combination groups. However, the sensitivity analysis performed based on a stricter antibiotic group definition (receipt of both antibiotics on at least 2 calendar days) did not alter the outcomes, which is reassuring. We were unable to assess the use of targeted antibiotic therapy because clinical data (eg, microbiology results) were not available. However, this may be less important because some literature suggests that cultures for S aureus are obtained infrequently2 and may be difficult to interpret when obtained,25 since culture growth can represent colonization rather than causative strains. An additional limitation is that administrative data do not include certain clinical outcomes, such as fever duration or degree of skin involvement, which could have differed among the groups. Last, the PHIS database only captures revisits or readmissions to PHIS hospitals, and so we are unable to exclude the possibility of a child being seen at or readmitted to another hospital.

Due to the observational design of this study and potential for incomplete measurement of illness severity, we recommend a future prospective trial with randomization to confirm these findings. One possible reason that LOS did not differ among groups is that the burden of clindamycin-resistant strains in our cohort could be low, and the addition of MSSA or MRSA coverage does not result in a clinically important increase in S aureus coverage. However, pooled pediatric hospital antibiogram data suggest the overall rate of clindamycin resistance is close to 20% in hospitals located in all US regions.26 Limited studies also suggest that MSSA may be the predominant pathogen associated with SSSS.2,9 To address this, future randomized trials could compare the effectiveness of clindamycin monotherapy to MSSA-specific agents like cefazolin or nafcillin. Unfortunately, anti-MSSA monotherapy was not evaluated in our study because very few children received this treatment. Using monotherapy as opposed to multiple antibiotics has the potential to promote antibiotic stewardship for antistaphylococcal antibiotics in the management of SSSS. Reducing unnecessary antibiotic use not only potentially affects antibiotic resistance, but could also benefit patients in reducing possible side effects, cost, and IV catheter complications.27 However, acknowledging our study limitations, our findings should be applied cautiously in clinical settings, in the context of local antibiogram data, individual culture results, and specific patient factors. The local clindamycin resistance rate for both MSSA and MRSA should be considered. Many antibiotics chosen to treat MRSA—such as vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole—will also have anti-MSSA activity and may have lower local resistance rates than clindamycin. Practitioners may also consider how each antibiotic kills bacteria; for example, beta-lactams rely on bacterial replication, but clindamycin does not. Each factor should influence how empiric treatment, whether monotherapy or combination, is chosen for children with SSSS.

CONCLUSION

In this large, multicenter cohort of hospitalized children with SSSS, we found that the addition of MSSA or MRSA coverage to clindamycin monotherapy was not associated with differences in outcomes of hospital LOS and treatment failure. Furthermore, clindamycin monotherapy was associated with lower overall cost. Prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these findings and assess whether clindamycin monotherapy, monotherapy with an anti-MSSA antibiotic, or alternative regimens are most effective for treatment of children with SSSS.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is an exfoliative toxin-mediated dermatitis that predominantly occurs in young children. Multiple recent reports indicate a rising incidence of this disease.1-4 Recommended treatment for SSSS includes antistaphylococcal antibiotics and supportive care measures.5,6 Elimination or reduction of the toxin-producing Staphylococcus aureus is thought to help limit disease progression and promote recovery. Experts advocate for the use of antibiotics even when there is no apparent focal source of infection, such as an abscess.6,7

Several factors may affect antibiotic selection, including the desire to inhibit toxin production and to target the causative pathogen in a bactericidal fashion. Because SSSS is toxin mediated, clindamycin is often recommended because of its inhibition of toxin synthesis.5,8 The clinical utility of adding other antibiotics to clindamycin for coverage of methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA) or methicillin-resistant S aureus (MRSA) is uncertain. Several studies report MSSA to be the predominant pathogen identified by culture2,9; however, SSSS caused by MRSA has been reported.9-11 Additionally, bactericidal antibiotics (eg, nafcillin) have been considered to hold potential clinical advantage as compared with bacteriostatic antibiotics (eg, clindamycin), even though clinical studies have not clearly demonstrated this advantage in the general population.12,13 Some experts recommend additional MRSA or MSSA coverage (such as vancomycin or nafcillin) in patients with high illness severity or nonresponse to therapy, or in areas where there is high prevalence of staphylococcal resistance to clindamycin.5,7,9,14 Alternatively, for areas with low MRSA prevalence, monotherapy with an anti-MSSA antibiotic is another potential option. No recent studies have compared patient outcomes among antibiotic regimens in children with SSSS.

Knowledge of the outcomes associated with different antibiotic regimens for children hospitalized with SSSS is needed and could be used to improve patient outcomes and potentially promote antibiotic stewardship. In this study, our objectives were to (1) describe antibiotic regimens given to children hospitalized with SSSS, and (2) examine the association of three antibiotic regimens commonly used for SSSS (clindamycin monotherapy, clindamycin plus additional MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus additional MRSA coverage) with patient outcomes of length of stay (LOS), treatment failure, and cost in a large cohort of children at US children’s hospitals.

METHODS

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective cohort study utilizing data within the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) database from July 1, 2011, to June 30, 2016. Thirty-five free-standing tertiary care US children’s hospitals within 24 states were included. The Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas) maintains the PHIS database, which contains de-identified patient information, including diagnoses (with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM, ICD-10-CM]), demographics, procedures, and daily billing records. Data quality and reliability are confirmed by participating institutions and the Children’s Hospital Association.15 The local institutional review board (IRB) deemed the study exempt from formal IRB review, as patient information was de-identified.

Study Population

We included hospitalized children aged newborn to 18 years with a primary or secondary diagnosis of SSSS (ICD-9, 695.81; ICD-10, L00). Children whose primary presentation and admission were to a PHIS hospital were included; children transferred from another hospital were excluded. The following exclusion criteria were based on previously published methodology.16 Children with complex chronic medical conditions as classified by Feudtner et al17 were excluded, since these children may require a different treatment approach than the general pediatric population. In order to decrease diagnostic ambiguity, we excluded children if an alternative dermatologic diagnosis was recorded as a principal or secondary diagnosis (eg, Stevens-Johnson syndrome or scarlet fever).16 Finally, hospitals with fewer than 10 children with SSSS during the study period were excluded.

Antibiotic Regimen Groups

We used PHIS daily billing codes to determine the antibiotics received by the study population. Children were classified into antibiotic regimen groups based on whether they received specific antibiotic combinations. Antibiotics received on any day during the hospitalization, including in the emergency department (ED), were used to assign patients to regimen groups. Antibiotics were classified into regimen groups based on consensus among study investigators, which included two board-certified pediatric infectious diseases specialists (A.C., R.M.). Antibiotic group definitions are listed in Table 1. Oral and intravenous (IV) therapies were grouped together for clindamycin, cephalexin/cefazolin, and linezolid because of good oral bioavailability in most situations.18 The three most common antistaphylococcal groups were chosen for further analysis: clindamycin alone, clindamycin plus MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage. The clindamycin group was defined as children with receipt of oral or IV clindamycin. Children who received clindamycin with additional MSSA coverage, such as cefazolin or nafcillin, were categorized as the clindamycin plus MSSA group. Children who received clindamycin with additional MRSA coverage, such as vancomycin or linezolid, were categorized as the clindamycin plus MRSA group. We chose not to include children who received the above regimens plus other antibiotics with partial antistaphylococcal activity, such as ampicillin, gentamicin, or ceftriaxone, in the clindamycin plus MSSA and clindamycin plus MRSA groups. We excluded these antibiotics to decrease the heterogeneity in the definition of regimen groups and allow a more direct comparison for effectiveness.

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, ethnicity and/or race, payer type, level of care, illness severity, and region. The variable definitions below are in keeping with a prior study of SSSS.16 Age was categorized as: birth to 59 days, 2 to 11 months, 1 to 4 years (preschool age), 5 to 10 years (school age), and 11 to 18 years (adolescent). We examined infants younger than 60 days separately from older infants because this population may warrant additional treatment considerations. Race and ethnicity were categorized as White (non-Hispanic), African American (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, or other. Payer types included government, private, or other. Level of care was assigned as either intensive care or acute care. Illness severity was assigned using the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG; 3M Corporation, St. Paul, Minnesota) severity levels.19 In line with a prior study,16 we defined “low illness severity” as the APR-DRG minor (1) classification. The moderate (2), major (3), and extreme (4) classifications were defined as “moderate to high illness severity,” since there were very few classifications of major or extreme (<5%) illness severity. We categorized hospitals into the following US regions: Northeast, Midwest, South, and West.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was hospital LOS in days, and secondary outcomes were treatment failure and hospital costs. Hospital LOS was chosen as the primary outcome to represent the time needed for the child to show clinical improvement. Treatment failure was defined as a same-cause 14-day ED revisit or hospital readmission, and these were determined to be same-cause if a diagnosis for SSSS (ICD-9, 695.81; ICD-10, L00) was documented for the return encounter. The 14-day interval for readmission and ED revisit was chosen to measure any relapse of symptoms after completion of antibiotic therapy, similar to a prior study of treatment failure in skin and soft tissue infections.20 Total costs of the hospitalization were estimated from charges using hospital- and year-specific cost-to-charge ratios. Subcategories of cost, including clinical, pharmacy, imaging, laboratory, supply, and other, were also compared among the three groups.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of children were summarized using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. These were compared across antibiotic groups using chi-square and Kruskal–Wallis tests, respectively. In unadjusted analyses, outcomes were compared across antibiotic regimen groups using these same statistical tests. In order to account for patient clustering within hospitals, generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to model outcomes with a random intercept for each hospital. Models were adjusted for SSSS being listed as a principal or secondary diagnosis, race, illness severity, and level of care. We log-transformed LOS and cost data prior to modeling because of the nonnormal distributions for these data. Owing to the inability to measure the number of antibiotic doses, and to reduce the possibility of including children who received few regimen-defined combination antibiotics, a post hoc sensitivity analysis was performed. This analysis used an alternative definition for antibiotic regimen groups, for which children admitted for 2 or more calendar days must have received regimen-specified antibiotics on at least 2 days of the admission. Additionally, outcomes were stratified by low and moderate/high illness severity and compared across the three antibiotic regimen groups. All analyses were performed with SAS (SAS 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Overall, 1,815 hospitalized children with SSSS were identified in the PHIS database, and after application of the exclusion criteria, 1,259 children remained, with 1,247 (99%) receiving antibiotics (Figure). The antibiotic regimens received by these children are described in Table 1. Of these, 828 children (66%) received one of the three most common antistaphylococcal regimens (clindamycin, clindamycin + MSSA, and clindamycin + MRSA) and were included for further analysis.

Characteristics of the 828 children are presented in Table 2. Most children (82%) were aged 4 years or younger, and distributions of age, sex, and insurance payer were similar among children receiving the three regimens. Thirty-two percent had moderate to high illness severity, and 3.5% required management in the intensive care setting. Of the three antibiotic regimens, clindamycin monotherapy was most common (47%), followed by clindamycin plus MSSA coverage (33%), and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage (20%). A higher proportion of children in the clindamycin plus MRSA group were African American and were hospitalized in the South. Children receiving clindamycin plus MRSA coverage had higher illness severity (44%) as compared with clindamycin monotherapy (28%) and clindamycin plus MSSA coverage (32%) (P = .001). Additionally, a larger proportion of children treated with clindamycin plus MRSA coverage were managed in the intensive care setting as compared with the clindamycin plus MSSA or clindamycin monotherapy groups.

Among the 828 children with SSSS, the median LOS was 2 days (IQR, 2-3), and treatment failure was 1.1% (95% CI, 0.4-1.8). After adjustment for illness severity, race, payer, and region (Table 3), the three antibiotic regimens were not associated with significant differences in LOS or treatment failure. Costs were significantly different among the three antibiotic regimens. Clindamycin plus MRSA coverage was associated with the greatest costs, whereas clindamycin monotherapy was associated with the lowest costs (mean, $5,348 vs $4,839, respectively; P < .001) (Table 3). In a sensitivity analysis using an alternative antibiotic regimen definition, we found results in line with the primary analysis, with no statistically significant differences in LOS (P = .44) or treatment failure (P = .54), but significant differences in cost (P < .001). Additionally, the same findings were present for LOS, treatment failure, and cost when outcomes were stratified by illness severity (Appendix Table). However, significant contributors to the higher cost in the clindamycin plus MRSA group did vary by illness severity stratification. Laboratory, supply, and pharmacy cost categories differed significantly among antibiotic groups for the low illness severity strata, whereas pharmacy was the only significant cost category difference in moderate/high illness severity.

DISCUSSION

Clindamycin monotherapy, clindamycin plus MSSA coverage, and clindamycin plus MRSA coverage are the most commonly administered antistaphylococcal antibiotic regimens for children hospitalized with SSSS at US children’s hospitals. Our multicenter study found that, across these antistaphylococcal antibiotic regimens, there were no associated differences in hospital LOS or treatment failure. However, the antibiotic regimens were associated with significant differences in overall hospital costs. These findings suggest that the use of clindamycin with additional MSSA or MRSA antibiotic coverage for children with SSSS may not be associated with additional clinical benefit, as compared with clindamycin monotherapy, and could potentially be more costly.

Prior literature describing LOS in relation to antibiotic use for children with SSSS is limited. Authors of a recent case series of 21 children in Philadelphia reported approximately 50% of children received clindamycin monotherapy or combination therapy, but patient outcomes such as LOS were not described.9 Clindamycin use and outcomes have been described in smaller studies and case reports of SSSS, which reported positive outcomes such as patient recovery and lack of disease recurrence.2,9,21 A small retrospective, comparative effectiveness study of 30 neonates with SSSS examined beta-lactamase–resistant penicillin use with and without cephalosporins. They found no effect on LOS, but findings were limited by a small sample size.22 Our study cohort included relatively few neonates, and thus our findings may not be applicable to this population subgroup. We chose not to include regimens with third-generation cephalosporins or ampicillin, which may have limited the number of included neonates, because these antibiotics are frequently administered during evaluation for invasive bacterial infections.23 We found a very low occurrence of treatment failure in our study cohort across all three groups, which is consistent with other studies of SSSS that report an overall good prognosis and low recurrence and/or readmission rates.6,16,24 The low prevalence of treatment failure, however, precluded our ability to detect small differences among antibiotic regimen groups that may exist.

We observed that cost differed significantly across antibiotic regimen groups, with lowest cost associated with clindamycin monotherapy in adjusted analysis despite similar LOS. Even with our illness-severity adjustment, there may have been other unmeasured factors resulting in the higher cost associated with the combination groups. Hence, we also examined cost breakdown with a stratified analysis by illness severity. We found that pharmacy costs were significantly different among antibiotic groups in both illness severity strata, whereas those with low illness severity also differed by laboratory and supply costs. Thus, pharmacy cost differences may be the largest driver in the cost differential among groups. Lower cost in the clindamycin monotherapy group is likely due to administration of a single antibiotic. The reason for supply and laboratory cost differences is uncertain, but higher cost in the clindamycin plus MRSA group could possibly be from laboratory testing related to drug monitoring (eg, renal function testing or drug levels). While other studies have reported costs for hospitalized children with SSSS associated with different patient characteristics or diagnostic testing,1,16 to our knowledge, no other studies have reported cost related to antibiotic regimens for SSSS. As healthcare reimbursements shift to value-based models, identifying treatment regimens with equal efficacy but lower cost will become increasingly important. Future studies should also examine other covariates and outcomes, such as oral vs parenteral antibiotic use, use of monitoring laboratories related to antibiotic choice, and adverse drug effects.

Several strengths and additional limitations apply to our study. Our study is one of the few to describe outcomes associated with antibiotic regimens for children with SSSS. With the PHIS database, we were able to include a large number of children with SSSS from children’s hospitals across the United States. Although the PHIS database affords these strengths, there are limitations inherent to administrative data. Children with SSSS were identified by documented ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes, which might lead to misclassification. However, misclassification is less likely because only one ICD-9 and ICD-10 code exists for SSSS, and the characteristics of this condition are specific. Also, diagnostic codes for other dermatologic conditions (eg, scarlet fever) were excluded to further reduce the chance of misclassification. A limitation to our use of PHIS billing codes was the inability to confirm the dosage of antibiotics given, the number of doses, or whether antibiotics were prescribed upon discharge. Another limitation is that children whose antibiotic therapy was changed during hospitalization (eg, from clindamycin monotherapy to cefazolin monotherapy) were categorized into the combination groups. However, the sensitivity analysis performed based on a stricter antibiotic group definition (receipt of both antibiotics on at least 2 calendar days) did not alter the outcomes, which is reassuring. We were unable to assess the use of targeted antibiotic therapy because clinical data (eg, microbiology results) were not available. However, this may be less important because some literature suggests that cultures for S aureus are obtained infrequently2 and may be difficult to interpret when obtained,25 since culture growth can represent colonization rather than causative strains. An additional limitation is that administrative data do not include certain clinical outcomes, such as fever duration or degree of skin involvement, which could have differed among the groups. Last, the PHIS database only captures revisits or readmissions to PHIS hospitals, and so we are unable to exclude the possibility of a child being seen at or readmitted to another hospital.

Due to the observational design of this study and potential for incomplete measurement of illness severity, we recommend a future prospective trial with randomization to confirm these findings. One possible reason that LOS did not differ among groups is that the burden of clindamycin-resistant strains in our cohort could be low, and the addition of MSSA or MRSA coverage does not result in a clinically important increase in S aureus coverage. However, pooled pediatric hospital antibiogram data suggest the overall rate of clindamycin resistance is close to 20% in hospitals located in all US regions.26 Limited studies also suggest that MSSA may be the predominant pathogen associated with SSSS.2,9 To address this, future randomized trials could compare the effectiveness of clindamycin monotherapy to MSSA-specific agents like cefazolin or nafcillin. Unfortunately, anti-MSSA monotherapy was not evaluated in our study because very few children received this treatment. Using monotherapy as opposed to multiple antibiotics has the potential to promote antibiotic stewardship for antistaphylococcal antibiotics in the management of SSSS. Reducing unnecessary antibiotic use not only potentially affects antibiotic resistance, but could also benefit patients in reducing possible side effects, cost, and IV catheter complications.27 However, acknowledging our study limitations, our findings should be applied cautiously in clinical settings, in the context of local antibiogram data, individual culture results, and specific patient factors. The local clindamycin resistance rate for both MSSA and MRSA should be considered. Many antibiotics chosen to treat MRSA—such as vancomycin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole—will also have anti-MSSA activity and may have lower local resistance rates than clindamycin. Practitioners may also consider how each antibiotic kills bacteria; for example, beta-lactams rely on bacterial replication, but clindamycin does not. Each factor should influence how empiric treatment, whether monotherapy or combination, is chosen for children with SSSS.

CONCLUSION

In this large, multicenter cohort of hospitalized children with SSSS, we found that the addition of MSSA or MRSA coverage to clindamycin monotherapy was not associated with differences in outcomes of hospital LOS and treatment failure. Furthermore, clindamycin monotherapy was associated with lower overall cost. Prospective randomized studies are needed to confirm these findings and assess whether clindamycin monotherapy, monotherapy with an anti-MSSA antibiotic, or alternative regimens are most effective for treatment of children with SSSS.

1. Staiman A, Hsu DY, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in United States children. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):704-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16097

2. Hulten KG, Kok M, King KE, Lamberth LB, Kaplan SL. Increasing numbers of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome cases caused by ST121 in Houston, TX. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(1):30-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002499

3. Arnold JD, Hoek SN, Kirkorian AY. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in the United States: A cross-sectional study, 2010-2014. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):404-406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.023

4. Hayward A, Knott F, Petersen I, et al. Increasing hospitalizations and general practice prescriptions for community-onset staphylococcal disease, England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(5):720-726. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.070153

5. Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. MRSA, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other cutaneous bacterial emergencies. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39(10):627-633. https://doi.org/10.3928/00904481-20100922-02

6. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, Evans RW, Poston SM. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(2):224-242.

7. Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(11):1418-1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12541

8. Hodille E, Rose W, Diep BA, Goutelle S, Lina G, Dumitrescu O. The role of antibiotics in modulating virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(4):887-917. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00120-16

9. Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, McGowan KL, Yan AC, Treat JR. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(3):305-308. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12195

10. Yamaguchi T, Yokota Y, Terajima J, et al. Clonal association of Staphylococcus aureus causing bullous impetigo and the emergence of new methicillin-resistant clonal groups in Kansai district in Japan. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(10):1511-1516. https://doi.org/10.1086/340212

11. Noguchi N, Nakaminami H, Nishijima S, Kurokawa I, So H, Sasatsu M. Antimicrobial agent of susceptibilities and antiseptic resistance gene distribution among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2119-2125. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02690-05

12. Pankey GA, Sabath LD. Clinical relevance of bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms of action in the treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(6):864-870. https://doi.org/10.1086/381972

13. Wald-Dickler N, Holtom P, Spellberg B. Busting the myth of “static vs cidal”: a systemic literature review. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(9):1470-1474. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix1127

14. Ladhani S, Joannou CL. Difficulties in diagnosis and management of the staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(9):819-821. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006454-200009000-00002

15. Mongelluzzo J, Mohamad Z, Ten Have TR, Shah SS. Corticosteroids and mortality in children with bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2048-2055. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.299.17.2048

16. Neubauer HC, Hall M, Wallace SS, et al. Variation in diagnostic test use and associated outcomes in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome at children’s hospitals. Hosp Pediatr. 2018;8(9):530-537. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2018-0032

17. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-199

18. Sauberan JS, Bradley JS. Antimicrobial agents. In: Long SS, ed. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Elsevier; 2018:1499-1531.

19. Sedman AB, Bahl V, Bunting E, et al. Clinical redesign using all patient refined diagnosis related groups. Pediatrics. 2004;114(4):965-969. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-0650

20. Williams DJ, Cooper WO, Kaltenbach LA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of antibiotic treatment strategies for pediatric skin and soft-tissue infections. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e479-487. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3681

21. Haasnoot PJ, De Vries A. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in a 4-year-old child: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12(1):20. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13256-017-1533-7

22. Li MY, Hua Y, Wei GH, Qiu L. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in neonates: an 8-year retrospective study in a single institution. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(1):43-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12114

23. Markham JL, Hall M, Queen MA, et al. Variation in antibiotic selection and clinical outcomes in infants <60 days hospitalized with skin and soft tissue infections. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(1):30-38. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0237

24. Davidson J, Polly S, Hayes PJ, Fisher KR, Talati AJ, Patel T. Recurrent staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in an extremely low-birth-weight neonate. AJP Rep. 2017;7(2):e134-e137. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1603971

25. Ladhani S, Robbie S, Chapple DS, Joannou CL, Evans RW. Isolating Staphylococcus aureus from children with suspected Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome is not clinically useful. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(3):284-286.

26. Tamma PD, Robinson GL, Gerber JS, et al. Pediatric antimicrobial susceptibility trends across the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(12):1244-1251. https://doi.org/10.1086/673974

27. Unbeck M, Forberg U, Ygge BM, Ehrenberg A, Petzold M, Johansson E. Peripheral venous catheter related complications are common among paediatric and neonatal patients. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(6):566-574. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12963

1. Staiman A, Hsu DY, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in United States children. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):704-708. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16097

2. Hulten KG, Kok M, King KE, Lamberth LB, Kaplan SL. Increasing numbers of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome cases caused by ST121 in Houston, TX. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(1):30-34. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002499

3. Arnold JD, Hoek SN, Kirkorian AY. Epidemiology of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome in the United States: A cross-sectional study, 2010-2014. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(2):404-406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.023

4. Hayward A, Knott F, Petersen I, et al. Increasing hospitalizations and general practice prescriptions for community-onset staphylococcal disease, England. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(5):720-726. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1405.070153

5. Berk DR, Bayliss SJ. MRSA, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and other cutaneous bacterial emergencies. Pediatr Ann. 2010;39(10):627-633. https://doi.org/10.3928/00904481-20100922-02

6. Ladhani S, Joannou CL, Lochrie DP, Evans RW, Poston SM. Clinical, microbial, and biochemical aspects of the exfoliative toxins causing staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12(2):224-242.

7. Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome: diagnosis and management in children and adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(11):1418-1423. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12541

8. Hodille E, Rose W, Diep BA, Goutelle S, Lina G, Dumitrescu O. The role of antibiotics in modulating virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(4):887-917. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00120-16

9. Braunstein I, Wanat KA, Abuabara K, McGowan KL, Yan AC, Treat JR. Antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns in pediatric staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31(3):305-308. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12195

10. Yamaguchi T, Yokota Y, Terajima J, et al. Clonal association of Staphylococcus aureus causing bullous impetigo and the emergence of new methicillin-resistant clonal groups in Kansai district in Japan. J Infect Dis. 2002;185(10):1511-1516. https://doi.org/10.1086/340212

11. Noguchi N, Nakaminami H, Nishijima S, Kurokawa I, So H, Sasatsu M. Antimicrobial agent of susceptibilities and antiseptic resistance gene distribution among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from patients with impetigo and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(6):2119-2125. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.02690-05