User login

Fillers in Dermatology: From Past to Present

Fillers are products that are injected into soft tissue and are classified as either resorbable or nonresorbable (permanent). Several dermal and subcutaneous fillers for soft tissue augmentation currently are available. This article provides a brief review of the history of filler agents currently available for soft tissue augmentation. Cadaveric-derived fillers and implants will not be discussed, as these materials are expensive, are not all approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and are more commonly used in burn victims than in cosmetic patients.

History of Fillers in Dermatology

The first known injectable agent was paraffin, but its use as a dermal filler was abandoned after complications including embolization, migration (ie, movement into surrounding tissue), and granuloma formation were reported.1 Silicone also was banned by the FDA for use as a soft tissue filler due to similar complications. Bovine collagen was the first agent to be approved by the FDA for cosmetic injection, and since then many filler agents have revolutionized a new era of cosmetic enhancement.1 Injectable soft tissue fillers now can be classified based on several characteristics, including site of placement (ie, dermal or subcutaneous), animal versus nonanimal derivation (eg, autologous, xenograft, semisynthetic, synthetic), and duration of effects (temporary [<6 months], long-lasting [6 months– 2 years], semipermanent [2–5 years], permanent [>5 years]).2

In the 19th century, early instances of soft tissue augmentation using dermal fillers included autologous fat harvested from the arms for correction of depressed facial defects and scars in a patient with tuberculous osteitis as well as injection of paraffin into the scrotum as a testicular prosthesis in a patient with advanced tuberculosis.1 Later, a technique using a syringe to transfer autologous fat from the extremities was used for facial soft tissue augmentation and contouring, and permanent facial soft tissue augmentation using liquid silicone also was performed. In 1981, purified bovine dermal collagen was first approved by the FDA as a xenogenic agent for dermal injection.3

In 2003, the FDA began to approve new fillers for temporary soft tissue augmentation.3 Approval of injectable purified human collagen derived from fibroblasts was followed by another class of new agents: hyaluronic acid fillers.1 A biodegradable non–animal based stabilized hyaluronic acid was followed by more agents derived from rooster combs. Further investigations and research have continued, and more long-lasting synthetic fillers have become available, including calcium hydroxylapatite and poly-L-lactic acid. A renewed interest in permanent agents and longer lasting products such as silicone oil and polymethyl methacrylate also has emerged.4

The Future of Fillers

While earlier filler materials were limited, those used today are composed of a wide range of substances including collagen, hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, poly-L-lactic acid, and synthetic or manmade polymers (Table). The FDA has approved approximately 21 filler products for dermatologic indications, each with unique properties, advantages, and disadvantages.3 For example, there are several fillers that not only provide soft tissue augmentation but also stimulate collagen production. However, complications can occur, often many years after the initial treatment. Side effects such as swelling, erythema, and nodules may occur and in rare instances foreign body granulomas may develop and may be difficult to eradicate.5 Except for autologous fat, all fillers are foreign bodies and therefore can cause foreign body granulomatous reactions ranging from common (eg, with paraffin) to rare (eg, with hyaluronic acid) in occurrence.6 The clinical presentation of these reactions is variable, ranging from single to multiple nodules at the injection site to diffuse, hard swelling of the face accompanied by reddening of the skin.

With the increasing desire for a youthful appearance among the aging population, the pharmaceutical industry has responded by increasing the number of available treatment options to meet the demands of cosmetic patients, one of the fastest growing subpopulations in the field of dermatology. Fillers also have provided new options for patients who are unable to afford plastic surgery or those who are poor surgical candidates. The ideal filler material is nonallergenic, noncarcinogenic, and nonteratogenic. It should be stable, affordable, malleable, reversible, and durable with results that can be reproduced and should cause minimal inflammation, migration, and detectable changes. The ideal filler also should have predictable and consistent results, feel natural, take little time to administer, require minimal preparation, cause no patient downtime, and have a low risk for complications. Ideal administration should be painless, user-friendly, and conducted in an outpatient setting with minimal recovery and easy storage. Although no single filler is ideal for all patients, indications, and situations, residents should be aware of the properties and characteristics that make each product unique in order to optimize treatment in all patients.

As demands for cosmetic procedures increase, it is important to incorporate knowledge of cosmetic procedures (eg, fillers for soft tissue augmentation) in resident education and training. Although cosmetic dermatology has been featured prominently in dermatology residency, surveys have shown that residents desire more training in this area.7 Although lectures on soft tissue augmentation are popular topics in dermatology, hands-on experience performing these procedures varies widely depending on different training programs. My institution offers several lectures on cosmetic dermatology, and residents are able to perform procedures for soft tissue augmentation as the first assistant or first surgeon during our cosmetic clinic sessions twice weekly.

Final Thoughts

There are a variety of fillers on the horizon to improve aging and volume loss and the science behind cosmetic injections is evolving. Regardless of the filler material chosen, optimal results are yielded by the combination of patient expectations, physician judgment based on clinical experience, and injection technique.

1. Kontis TC, Rivkin A. The history of injectable facial fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:67-72.

2. Ashinoff R. Overview: soft tissue augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27:479-487.

3. Soft tissue fillers approved by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/CosmeticDevices/WrinkleFillers/ucm227749.htm. Updated July 27, 2015. Accessed November 16, 2015.

4. Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A, Crosby MA. The role of hyaluronic acid fillers (restylane) in facial cosmetic surgery: review and technical considerations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(suppl 6):S41-S54.

5. Braun M, Braun S. Nodule formation following lip augmentation using porcine collagen-derived filler. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:579-581.

6. Lee JM, Kim YJ. Foreign body granulomas after the use of dermal fillers: pathophysiology, clinical appearance, histologic features, and treatment. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:232-239.

7. Kirby JS, Adgerson CN, Anderson BE. A survey of dermatology resident education in cosmetic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:e23-e28.

Fillers are products that are injected into soft tissue and are classified as either resorbable or nonresorbable (permanent). Several dermal and subcutaneous fillers for soft tissue augmentation currently are available. This article provides a brief review of the history of filler agents currently available for soft tissue augmentation. Cadaveric-derived fillers and implants will not be discussed, as these materials are expensive, are not all approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and are more commonly used in burn victims than in cosmetic patients.

History of Fillers in Dermatology

The first known injectable agent was paraffin, but its use as a dermal filler was abandoned after complications including embolization, migration (ie, movement into surrounding tissue), and granuloma formation were reported.1 Silicone also was banned by the FDA for use as a soft tissue filler due to similar complications. Bovine collagen was the first agent to be approved by the FDA for cosmetic injection, and since then many filler agents have revolutionized a new era of cosmetic enhancement.1 Injectable soft tissue fillers now can be classified based on several characteristics, including site of placement (ie, dermal or subcutaneous), animal versus nonanimal derivation (eg, autologous, xenograft, semisynthetic, synthetic), and duration of effects (temporary [<6 months], long-lasting [6 months– 2 years], semipermanent [2–5 years], permanent [>5 years]).2

In the 19th century, early instances of soft tissue augmentation using dermal fillers included autologous fat harvested from the arms for correction of depressed facial defects and scars in a patient with tuberculous osteitis as well as injection of paraffin into the scrotum as a testicular prosthesis in a patient with advanced tuberculosis.1 Later, a technique using a syringe to transfer autologous fat from the extremities was used for facial soft tissue augmentation and contouring, and permanent facial soft tissue augmentation using liquid silicone also was performed. In 1981, purified bovine dermal collagen was first approved by the FDA as a xenogenic agent for dermal injection.3

In 2003, the FDA began to approve new fillers for temporary soft tissue augmentation.3 Approval of injectable purified human collagen derived from fibroblasts was followed by another class of new agents: hyaluronic acid fillers.1 A biodegradable non–animal based stabilized hyaluronic acid was followed by more agents derived from rooster combs. Further investigations and research have continued, and more long-lasting synthetic fillers have become available, including calcium hydroxylapatite and poly-L-lactic acid. A renewed interest in permanent agents and longer lasting products such as silicone oil and polymethyl methacrylate also has emerged.4

The Future of Fillers

While earlier filler materials were limited, those used today are composed of a wide range of substances including collagen, hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, poly-L-lactic acid, and synthetic or manmade polymers (Table). The FDA has approved approximately 21 filler products for dermatologic indications, each with unique properties, advantages, and disadvantages.3 For example, there are several fillers that not only provide soft tissue augmentation but also stimulate collagen production. However, complications can occur, often many years after the initial treatment. Side effects such as swelling, erythema, and nodules may occur and in rare instances foreign body granulomas may develop and may be difficult to eradicate.5 Except for autologous fat, all fillers are foreign bodies and therefore can cause foreign body granulomatous reactions ranging from common (eg, with paraffin) to rare (eg, with hyaluronic acid) in occurrence.6 The clinical presentation of these reactions is variable, ranging from single to multiple nodules at the injection site to diffuse, hard swelling of the face accompanied by reddening of the skin.

With the increasing desire for a youthful appearance among the aging population, the pharmaceutical industry has responded by increasing the number of available treatment options to meet the demands of cosmetic patients, one of the fastest growing subpopulations in the field of dermatology. Fillers also have provided new options for patients who are unable to afford plastic surgery or those who are poor surgical candidates. The ideal filler material is nonallergenic, noncarcinogenic, and nonteratogenic. It should be stable, affordable, malleable, reversible, and durable with results that can be reproduced and should cause minimal inflammation, migration, and detectable changes. The ideal filler also should have predictable and consistent results, feel natural, take little time to administer, require minimal preparation, cause no patient downtime, and have a low risk for complications. Ideal administration should be painless, user-friendly, and conducted in an outpatient setting with minimal recovery and easy storage. Although no single filler is ideal for all patients, indications, and situations, residents should be aware of the properties and characteristics that make each product unique in order to optimize treatment in all patients.

As demands for cosmetic procedures increase, it is important to incorporate knowledge of cosmetic procedures (eg, fillers for soft tissue augmentation) in resident education and training. Although cosmetic dermatology has been featured prominently in dermatology residency, surveys have shown that residents desire more training in this area.7 Although lectures on soft tissue augmentation are popular topics in dermatology, hands-on experience performing these procedures varies widely depending on different training programs. My institution offers several lectures on cosmetic dermatology, and residents are able to perform procedures for soft tissue augmentation as the first assistant or first surgeon during our cosmetic clinic sessions twice weekly.

Final Thoughts

There are a variety of fillers on the horizon to improve aging and volume loss and the science behind cosmetic injections is evolving. Regardless of the filler material chosen, optimal results are yielded by the combination of patient expectations, physician judgment based on clinical experience, and injection technique.

Fillers are products that are injected into soft tissue and are classified as either resorbable or nonresorbable (permanent). Several dermal and subcutaneous fillers for soft tissue augmentation currently are available. This article provides a brief review of the history of filler agents currently available for soft tissue augmentation. Cadaveric-derived fillers and implants will not be discussed, as these materials are expensive, are not all approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and are more commonly used in burn victims than in cosmetic patients.

History of Fillers in Dermatology

The first known injectable agent was paraffin, but its use as a dermal filler was abandoned after complications including embolization, migration (ie, movement into surrounding tissue), and granuloma formation were reported.1 Silicone also was banned by the FDA for use as a soft tissue filler due to similar complications. Bovine collagen was the first agent to be approved by the FDA for cosmetic injection, and since then many filler agents have revolutionized a new era of cosmetic enhancement.1 Injectable soft tissue fillers now can be classified based on several characteristics, including site of placement (ie, dermal or subcutaneous), animal versus nonanimal derivation (eg, autologous, xenograft, semisynthetic, synthetic), and duration of effects (temporary [<6 months], long-lasting [6 months– 2 years], semipermanent [2–5 years], permanent [>5 years]).2

In the 19th century, early instances of soft tissue augmentation using dermal fillers included autologous fat harvested from the arms for correction of depressed facial defects and scars in a patient with tuberculous osteitis as well as injection of paraffin into the scrotum as a testicular prosthesis in a patient with advanced tuberculosis.1 Later, a technique using a syringe to transfer autologous fat from the extremities was used for facial soft tissue augmentation and contouring, and permanent facial soft tissue augmentation using liquid silicone also was performed. In 1981, purified bovine dermal collagen was first approved by the FDA as a xenogenic agent for dermal injection.3

In 2003, the FDA began to approve new fillers for temporary soft tissue augmentation.3 Approval of injectable purified human collagen derived from fibroblasts was followed by another class of new agents: hyaluronic acid fillers.1 A biodegradable non–animal based stabilized hyaluronic acid was followed by more agents derived from rooster combs. Further investigations and research have continued, and more long-lasting synthetic fillers have become available, including calcium hydroxylapatite and poly-L-lactic acid. A renewed interest in permanent agents and longer lasting products such as silicone oil and polymethyl methacrylate also has emerged.4

The Future of Fillers

While earlier filler materials were limited, those used today are composed of a wide range of substances including collagen, hyaluronic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, poly-L-lactic acid, and synthetic or manmade polymers (Table). The FDA has approved approximately 21 filler products for dermatologic indications, each with unique properties, advantages, and disadvantages.3 For example, there are several fillers that not only provide soft tissue augmentation but also stimulate collagen production. However, complications can occur, often many years after the initial treatment. Side effects such as swelling, erythema, and nodules may occur and in rare instances foreign body granulomas may develop and may be difficult to eradicate.5 Except for autologous fat, all fillers are foreign bodies and therefore can cause foreign body granulomatous reactions ranging from common (eg, with paraffin) to rare (eg, with hyaluronic acid) in occurrence.6 The clinical presentation of these reactions is variable, ranging from single to multiple nodules at the injection site to diffuse, hard swelling of the face accompanied by reddening of the skin.

With the increasing desire for a youthful appearance among the aging population, the pharmaceutical industry has responded by increasing the number of available treatment options to meet the demands of cosmetic patients, one of the fastest growing subpopulations in the field of dermatology. Fillers also have provided new options for patients who are unable to afford plastic surgery or those who are poor surgical candidates. The ideal filler material is nonallergenic, noncarcinogenic, and nonteratogenic. It should be stable, affordable, malleable, reversible, and durable with results that can be reproduced and should cause minimal inflammation, migration, and detectable changes. The ideal filler also should have predictable and consistent results, feel natural, take little time to administer, require minimal preparation, cause no patient downtime, and have a low risk for complications. Ideal administration should be painless, user-friendly, and conducted in an outpatient setting with minimal recovery and easy storage. Although no single filler is ideal for all patients, indications, and situations, residents should be aware of the properties and characteristics that make each product unique in order to optimize treatment in all patients.

As demands for cosmetic procedures increase, it is important to incorporate knowledge of cosmetic procedures (eg, fillers for soft tissue augmentation) in resident education and training. Although cosmetic dermatology has been featured prominently in dermatology residency, surveys have shown that residents desire more training in this area.7 Although lectures on soft tissue augmentation are popular topics in dermatology, hands-on experience performing these procedures varies widely depending on different training programs. My institution offers several lectures on cosmetic dermatology, and residents are able to perform procedures for soft tissue augmentation as the first assistant or first surgeon during our cosmetic clinic sessions twice weekly.

Final Thoughts

There are a variety of fillers on the horizon to improve aging and volume loss and the science behind cosmetic injections is evolving. Regardless of the filler material chosen, optimal results are yielded by the combination of patient expectations, physician judgment based on clinical experience, and injection technique.

1. Kontis TC, Rivkin A. The history of injectable facial fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:67-72.

2. Ashinoff R. Overview: soft tissue augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27:479-487.

3. Soft tissue fillers approved by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/CosmeticDevices/WrinkleFillers/ucm227749.htm. Updated July 27, 2015. Accessed November 16, 2015.

4. Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A, Crosby MA. The role of hyaluronic acid fillers (restylane) in facial cosmetic surgery: review and technical considerations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(suppl 6):S41-S54.

5. Braun M, Braun S. Nodule formation following lip augmentation using porcine collagen-derived filler. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:579-581.

6. Lee JM, Kim YJ. Foreign body granulomas after the use of dermal fillers: pathophysiology, clinical appearance, histologic features, and treatment. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:232-239.

7. Kirby JS, Adgerson CN, Anderson BE. A survey of dermatology resident education in cosmetic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:e23-e28.

1. Kontis TC, Rivkin A. The history of injectable facial fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:67-72.

2. Ashinoff R. Overview: soft tissue augmentation. Clin Plast Surg. 2000;27:479-487.

3. Soft tissue fillers approved by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/CosmeticDevices/WrinkleFillers/ucm227749.htm. Updated July 27, 2015. Accessed November 16, 2015.

4. Rohrich RJ, Ghavami A, Crosby MA. The role of hyaluronic acid fillers (restylane) in facial cosmetic surgery: review and technical considerations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(suppl 6):S41-S54.

5. Braun M, Braun S. Nodule formation following lip augmentation using porcine collagen-derived filler. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:579-581.

6. Lee JM, Kim YJ. Foreign body granulomas after the use of dermal fillers: pathophysiology, clinical appearance, histologic features, and treatment. Arch Plast Surg. 2015;42:232-239.

7. Kirby JS, Adgerson CN, Anderson BE. A survey of dermatology resident education in cosmetic procedures. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:e23-e28.

Don’t Forget About Syphilis

Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of “dark spots” on both hands for 2 months (Figure 1). He had been treated 1 month earlier with various topical agents, including mid-potency steroids and lightening agents, and had not seen a change. Interestingly, he reported recent-onset of similar lesions on the feet (Figure 2). Initially, our differential diagnosis indicated some form of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but the recent onset of the lesions on the feet 1 week prior, the distribution of the lesions, and the absence of an inciting factor did not fit the clinical picture. Among various laboratory tests, rapid plasma reagin was positive, and the patient was appropriately diagnosed and treated for secondary syphilis with 2.4 million U of benzathine penicillin.

|

|

The Great Masquerader

Syphilis has been called “the great masquerader” or “the great imitator” because it is protean in appearance, manifests in different stages, and can affect different parts of the body.1 In fact, another case of secondary syphilis I saw prior to this patient appeared different. Secondary syphilis has variable clinical presentations and thus is difficult to recognize. It is estimated that approximately half of community physicians will not clinically suspect secondary syphilis.2

Resurgence of Syphilis

It is not every day that you may diagnose syphilis in an outpatient clinic or consultation service, but it recently has been making resurgence, particularly in inner-city settings. Although syphilis is one of the oldest sexually transmitted diseases and has established and effective treatment options, it is now reemerging as a major public health problem in urban communities. A 2001 study by Williams and Ekundayo3 evaluated the distribution of and factors affecting the syphilis epidemic among inner-city minorities in Baltimore, Maryland, and found that it was the city with the highest number of syphilis cases in the nation, surpassing the national average of 2.6 cases per 100,000 population. The factors that particularly favored syphilis infectivity were poverty, poor communication with health care providers, exchanging sex for drugs, lower educational background, and inadequate health education.3 Although syphilis should not be forgotten as part of a differential diagnosis, preventative health education should be undertaken.

Diagnostic Approach

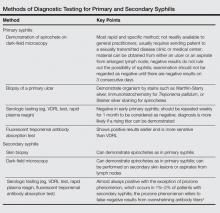

The best way to approach a possible case of syphilis is to have a high index of suspicion (Table). The skin findings of secondary syphilis may mimic other skin conditions (as described above), including pityriasis rosea, erythema multiforme, drug reactions, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. Although the disease usually begins approximately 6 weeks after the onset of a primary chancre, approximately 25% of patients with secondary syphilis will not recall a chancre, and in other cases, the primary chancre will still be present.5 The case reported above did not have any other associated symptoms, but commonly reported symptoms in other cases have included headaches, fevers, pruritus, loss of appetite, and malaise.6

Clinical Features of Secondary Syphilis

Usually, the lesions of syphiloderms consist of variably scaly macules and papules that can be annular, pustular, or psoriasiform. They typically are widespread and symmetric, though in some cases they can remain localized. The appearance also may vary depending on immunocompromised status, which may cause a more aggressive and quicker appearance of the rash.

The Connection to Human Immunodeficiency Virus and AIDS

It is known that patients with syphilis have an increased incidence of other sexually transmitted infections such as venereal warts, gonorrhea, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, thus patients should be tested for these conditions as part of their course of treatment. It has been shown that cutaneous sores/chancres facilitate transmission and acquisition of HIV infection. The risk for acquiring HIV increases 2- to 5-fold if exposure occurs when syphilis is present.7 Additionally, syphilis will increase viral loads in patients who are already infected with HIV. These data are concerning, particularly because many patients with syphilis also are infected with HIV.8

Final Thoughts

Although syphilis is known to present with highly variable clinical presentations, early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and patient education are crucial to avoid further complications.9 Social factors have contributed to a resurgence of syphilis; although easily treatable, it can lead to great suffering and morbidity. In summary, syphilis is a treatable infectious disease and physicians should test for it when investigating a patient, particularly one with risk factors as well as a symmetric hyperpigmented rash on the acral surfaces. There are uncommon presentations of syphilis, thus it is important to consider it early on and treat appropriately to prevent life-threatening complications.

1. Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C, et al. Brief history of syphilis. J Med Life. 2014;7:4-10.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2007. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008.

3. Williams PB, Ekundayo O. Study of distribution and factors affecting syphilis epidemic among inner-city minorities of Baltimore. Public Health. 2001;115:387-393.

4. Ruchi S, Mangala HC, Murugesh SB, et al. Prozone phenomenon in secondary syphilis. Indian J Sex Trans Dis. 2011;32:47-49.

5. Lee V, Kinghorn G. Syphilis: an update. Clin Med. 2008;8:330-333.

6. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

7. Bolan G. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous duo affecting gay and bisexual men. https://blog.aids.gov/2012/12/ syphilis-and-hiv-a-dangerous-duo-affecting-gay-and -bisexual-men.html. Published December 13, 2012. Accessed August 19, 2015.

8. Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Syphilis and HIV infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1222-1228.

9. Green CB, Fitzpatrick J. Syphilis. In: Fitzpatrick J, Morelli J, eds. Dermatology Secrets Plus. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:195-200.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of “dark spots” on both hands for 2 months (Figure 1). He had been treated 1 month earlier with various topical agents, including mid-potency steroids and lightening agents, and had not seen a change. Interestingly, he reported recent-onset of similar lesions on the feet (Figure 2). Initially, our differential diagnosis indicated some form of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but the recent onset of the lesions on the feet 1 week prior, the distribution of the lesions, and the absence of an inciting factor did not fit the clinical picture. Among various laboratory tests, rapid plasma reagin was positive, and the patient was appropriately diagnosed and treated for secondary syphilis with 2.4 million U of benzathine penicillin.

|

|

The Great Masquerader

Syphilis has been called “the great masquerader” or “the great imitator” because it is protean in appearance, manifests in different stages, and can affect different parts of the body.1 In fact, another case of secondary syphilis I saw prior to this patient appeared different. Secondary syphilis has variable clinical presentations and thus is difficult to recognize. It is estimated that approximately half of community physicians will not clinically suspect secondary syphilis.2

Resurgence of Syphilis

It is not every day that you may diagnose syphilis in an outpatient clinic or consultation service, but it recently has been making resurgence, particularly in inner-city settings. Although syphilis is one of the oldest sexually transmitted diseases and has established and effective treatment options, it is now reemerging as a major public health problem in urban communities. A 2001 study by Williams and Ekundayo3 evaluated the distribution of and factors affecting the syphilis epidemic among inner-city minorities in Baltimore, Maryland, and found that it was the city with the highest number of syphilis cases in the nation, surpassing the national average of 2.6 cases per 100,000 population. The factors that particularly favored syphilis infectivity were poverty, poor communication with health care providers, exchanging sex for drugs, lower educational background, and inadequate health education.3 Although syphilis should not be forgotten as part of a differential diagnosis, preventative health education should be undertaken.

Diagnostic Approach

The best way to approach a possible case of syphilis is to have a high index of suspicion (Table). The skin findings of secondary syphilis may mimic other skin conditions (as described above), including pityriasis rosea, erythema multiforme, drug reactions, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. Although the disease usually begins approximately 6 weeks after the onset of a primary chancre, approximately 25% of patients with secondary syphilis will not recall a chancre, and in other cases, the primary chancre will still be present.5 The case reported above did not have any other associated symptoms, but commonly reported symptoms in other cases have included headaches, fevers, pruritus, loss of appetite, and malaise.6

Clinical Features of Secondary Syphilis

Usually, the lesions of syphiloderms consist of variably scaly macules and papules that can be annular, pustular, or psoriasiform. They typically are widespread and symmetric, though in some cases they can remain localized. The appearance also may vary depending on immunocompromised status, which may cause a more aggressive and quicker appearance of the rash.

The Connection to Human Immunodeficiency Virus and AIDS

It is known that patients with syphilis have an increased incidence of other sexually transmitted infections such as venereal warts, gonorrhea, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, thus patients should be tested for these conditions as part of their course of treatment. It has been shown that cutaneous sores/chancres facilitate transmission and acquisition of HIV infection. The risk for acquiring HIV increases 2- to 5-fold if exposure occurs when syphilis is present.7 Additionally, syphilis will increase viral loads in patients who are already infected with HIV. These data are concerning, particularly because many patients with syphilis also are infected with HIV.8

Final Thoughts

Although syphilis is known to present with highly variable clinical presentations, early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and patient education are crucial to avoid further complications.9 Social factors have contributed to a resurgence of syphilis; although easily treatable, it can lead to great suffering and morbidity. In summary, syphilis is a treatable infectious disease and physicians should test for it when investigating a patient, particularly one with risk factors as well as a symmetric hyperpigmented rash on the acral surfaces. There are uncommon presentations of syphilis, thus it is important to consider it early on and treat appropriately to prevent life-threatening complications.

Case Report

A 42-year-old man presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of “dark spots” on both hands for 2 months (Figure 1). He had been treated 1 month earlier with various topical agents, including mid-potency steroids and lightening agents, and had not seen a change. Interestingly, he reported recent-onset of similar lesions on the feet (Figure 2). Initially, our differential diagnosis indicated some form of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, but the recent onset of the lesions on the feet 1 week prior, the distribution of the lesions, and the absence of an inciting factor did not fit the clinical picture. Among various laboratory tests, rapid plasma reagin was positive, and the patient was appropriately diagnosed and treated for secondary syphilis with 2.4 million U of benzathine penicillin.

|

|

The Great Masquerader

Syphilis has been called “the great masquerader” or “the great imitator” because it is protean in appearance, manifests in different stages, and can affect different parts of the body.1 In fact, another case of secondary syphilis I saw prior to this patient appeared different. Secondary syphilis has variable clinical presentations and thus is difficult to recognize. It is estimated that approximately half of community physicians will not clinically suspect secondary syphilis.2

Resurgence of Syphilis

It is not every day that you may diagnose syphilis in an outpatient clinic or consultation service, but it recently has been making resurgence, particularly in inner-city settings. Although syphilis is one of the oldest sexually transmitted diseases and has established and effective treatment options, it is now reemerging as a major public health problem in urban communities. A 2001 study by Williams and Ekundayo3 evaluated the distribution of and factors affecting the syphilis epidemic among inner-city minorities in Baltimore, Maryland, and found that it was the city with the highest number of syphilis cases in the nation, surpassing the national average of 2.6 cases per 100,000 population. The factors that particularly favored syphilis infectivity were poverty, poor communication with health care providers, exchanging sex for drugs, lower educational background, and inadequate health education.3 Although syphilis should not be forgotten as part of a differential diagnosis, preventative health education should be undertaken.

Diagnostic Approach

The best way to approach a possible case of syphilis is to have a high index of suspicion (Table). The skin findings of secondary syphilis may mimic other skin conditions (as described above), including pityriasis rosea, erythema multiforme, drug reactions, psoriasis, pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta, and dyshidrotic eczema, among others. Although the disease usually begins approximately 6 weeks after the onset of a primary chancre, approximately 25% of patients with secondary syphilis will not recall a chancre, and in other cases, the primary chancre will still be present.5 The case reported above did not have any other associated symptoms, but commonly reported symptoms in other cases have included headaches, fevers, pruritus, loss of appetite, and malaise.6

Clinical Features of Secondary Syphilis

Usually, the lesions of syphiloderms consist of variably scaly macules and papules that can be annular, pustular, or psoriasiform. They typically are widespread and symmetric, though in some cases they can remain localized. The appearance also may vary depending on immunocompromised status, which may cause a more aggressive and quicker appearance of the rash.

The Connection to Human Immunodeficiency Virus and AIDS

It is known that patients with syphilis have an increased incidence of other sexually transmitted infections such as venereal warts, gonorrhea, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, thus patients should be tested for these conditions as part of their course of treatment. It has been shown that cutaneous sores/chancres facilitate transmission and acquisition of HIV infection. The risk for acquiring HIV increases 2- to 5-fold if exposure occurs when syphilis is present.7 Additionally, syphilis will increase viral loads in patients who are already infected with HIV. These data are concerning, particularly because many patients with syphilis also are infected with HIV.8

Final Thoughts

Although syphilis is known to present with highly variable clinical presentations, early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and patient education are crucial to avoid further complications.9 Social factors have contributed to a resurgence of syphilis; although easily treatable, it can lead to great suffering and morbidity. In summary, syphilis is a treatable infectious disease and physicians should test for it when investigating a patient, particularly one with risk factors as well as a symmetric hyperpigmented rash on the acral surfaces. There are uncommon presentations of syphilis, thus it is important to consider it early on and treat appropriately to prevent life-threatening complications.

1. Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C, et al. Brief history of syphilis. J Med Life. 2014;7:4-10.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2007. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008.

3. Williams PB, Ekundayo O. Study of distribution and factors affecting syphilis epidemic among inner-city minorities of Baltimore. Public Health. 2001;115:387-393.

4. Ruchi S, Mangala HC, Murugesh SB, et al. Prozone phenomenon in secondary syphilis. Indian J Sex Trans Dis. 2011;32:47-49.

5. Lee V, Kinghorn G. Syphilis: an update. Clin Med. 2008;8:330-333.

6. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

7. Bolan G. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous duo affecting gay and bisexual men. https://blog.aids.gov/2012/12/ syphilis-and-hiv-a-dangerous-duo-affecting-gay-and -bisexual-men.html. Published December 13, 2012. Accessed August 19, 2015.

8. Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Syphilis and HIV infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1222-1228.

9. Green CB, Fitzpatrick J. Syphilis. In: Fitzpatrick J, Morelli J, eds. Dermatology Secrets Plus. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:195-200.

1. Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C, et al. Brief history of syphilis. J Med Life. 2014;7:4-10.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2007. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008.

3. Williams PB, Ekundayo O. Study of distribution and factors affecting syphilis epidemic among inner-city minorities of Baltimore. Public Health. 2001;115:387-393.

4. Ruchi S, Mangala HC, Murugesh SB, et al. Prozone phenomenon in secondary syphilis. Indian J Sex Trans Dis. 2011;32:47-49.

5. Lee V, Kinghorn G. Syphilis: an update. Clin Med. 2008;8:330-333.

6. Chapel TA. The signs and symptoms of secondary syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:161-164.

7. Bolan G. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous duo affecting gay and bisexual men. https://blog.aids.gov/2012/12/ syphilis-and-hiv-a-dangerous-duo-affecting-gay-and -bisexual-men.html. Published December 13, 2012. Accessed August 19, 2015.

8. Zetola NM, Klausner JD. Syphilis and HIV infection: an update. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:1222-1228.

9. Green CB, Fitzpatrick J. Syphilis. In: Fitzpatrick J, Morelli J, eds. Dermatology Secrets Plus. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2011:195-200.

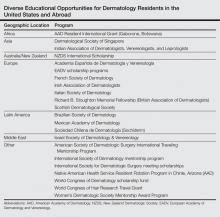

International Educational Opportunities for Dermatology Residents

Little has been written about the various types of international educational opportunities in dermatology, which include medical student electives, mentorship and scholarship programs for residents, international residency programs and conferences, and clinical or research-based fellowships (Table). After residency, there are many opportunities for teaching and volunteering in developing countries and ways to get involved in resident education. Although it may be difficult to participate in exchange programs during residency given the demanding schedules and limited vacation and elective time, international exchange programs in dermatology have become more accessible to residents and dermatologists worldwide. This exchange of ideas and information within our field promotes the advancement of scientific and clinical dermatologic insights that may not be commonplace elsewhere.

Resident Opportunities in Europe

During my internship, I received the Imrich Sarkany Non-European Memorial Scholarship from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, which facilitated my attendance at the organization’s 11th Spring Symposium in Belgrade, Serbia. I participated in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Belgrade, one of the oldest dermatologic programs in Europe, where I learned about Serbian culture, the country’s history as part of Yugoslavia, its health and medical education system, and its unique patient population that includes individuals from various ethnic groups. One of the highlights of my experience was learning about the Belgrade dermatovenereologic moulage collection (Figure), which was developed between 1925 and 1958 after the formation of University of Belgrade’s School of Medicine and the Institute of Dermatovenereology.1 In the early half of the 20th century when photographs were not yet established, the use of moulages as an artistic tool for medical education became very significant. The moulage collection in Belgrade is one of the most well known and is comprised of 350 pieces of which 280 are completely preserved while the rest are damaged.1 These moulages illustrate a wide variety of skin and venereal diseases that have been analyzed and contributed to the historical aspect of dermatologic education and medical conditions that are no longer prevalent thanks to modern medicine. Before World War I when these moulages were created, there was a high incidence of venereal diseases (eg, syphilis) and leprosy. Interestingly, most European dermatology residency programs incorporate the study of sexually transmitted infections and venereology as part of their training. In fact, many European dermatologists also use the term dermatovenereologist to describe their profession. Many of the moulages in the Belgrade collection were made by sculptors and painters, while others were made by physicians themselves, with great authenticity based on comparison of the original diagnosis to current diagnostic criteria.

I also had an opportunity to travel to Kuwait City, Kuwait, for the Kuwait Derma Update and Laser Conference when I was a research fellow at the University of Miami, Florida. In addition to learning opportunities in the form of seminars, workshops, and interactive sessions, each morning began with a visit to one of the government hospitals for a Grand Rounds discussion and presentation of difficult cases for management recommendations. The scientific program was led by Nawaf al-Mutairi, MD, the president of the conference, and involved diverse topics particularly on laser devices and modern therapies for psoriasis and vitiligo in ethnic skin, as well as how to address complications from these therapies. I first learned about platelet-rich plasma treatments and mesotherapy through a workshop at the conference, which became wildly popular in the Middle East and elsewhere during that time.

International Resident Opportunities Through the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is dedicated to international education opportunities. The Education and Volunteers Abroad Committee provides 4 grants per year to US dermatology residents who are in their second or third year of residency to participate in a rural health elective in Chinle, Arizona (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/native-american -health-service-resident-rotation-program). This 1- to 2-week elective takes place at the Native American Health Service where residents provide dermatologic care to the Navajo Nation population and work with primary health care providers to assist with diagnosis and management of dermatologic diseases.

The AAD also provides funding for 15 senior dermatology residents from the United States and Canada to participate in a 4- to 6-week elective in Gaborone, Botswana, which provides opportunities for residents to learn about the care of tropical and human immunodeficiency virus–related dermatologic conditions (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/resident-international-grant). These programs allow residents to develop image databases, perform teledermatology consultations, and practice in underserved areas with finite resources.

The AAD’s World Congress Fund Review Task Force also offers a limited number of scholarships to US and Canadian dermatology residents, fellows, or young dermatologists within 5 years of dermatology residency to attend the World Congress of Dermatology, the world’s oldest continuous international dermatology meeting, which takes place every 4 years (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/world-congress-of-dermatology). Grants also are offered for travel to dermatology meetings in Asia, Europe, and Latin America through mutual arrangements with several international dermatologic societies and the International Affairs Committee of the AAD (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/international-society-annual-meeting-travel-grant). These grants offer participants an opportunity to meet foreign colleagues and establish long-lasting professional relationships.

International Resident Opportunities Through the Women’s Dermatologic Society

The Women’s Dermatologic Society Mentorship Award Program helps to develop long-term mentoring relationships for residents and/or junior faculty that might not otherwise be possible due to distance or funding availability (http://www.womensderm.org/?page=MentorshipAward). As a recipient of this award in 2015, I was paired with Evangeline Handog, MD, current president of the International Society of Dermatology and the dermatology department chairperson at Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Muntinlupa City, Philippines. During my time in the Philippines, I was mostly at the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Manila. I also spent a day at the Asian Hospital and Medical Center, a state-of-the-art facility that is accredited by the Joint Commission International, and I attended a cosmetic dermatology workshop led by the Philippine Academy of Dermatologic Surgery Foundation, Inc. During this trip, I was surprised by the number of leprosy and human immunodeficiency virus cases that I encountered. Growing up in the United States for most of my life, I had never seen a case of leprosy. I also was very touched by the hospitality, generosity, and warmth of my mentor Dr. Handog, as well as the professors and dermatology residents that I encountered. The Women’s Dermatologic Society Mentorship Award Program exceeded my expectations, and I learned much more than I could by reading a textbook. I am very grateful for this experience and would do it again if I could.

Final Thoughts

Although it may be challenging to schedule international resident electives and opportunities while in residency training, international educational experiences allow for professional growth and development. An international medical experience can provide excellent opportunities for learning and service in remote or underserved areas in the world.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology scholarship committee; Nawaf al-Mutairi, MD, and the Kuwaiti Ministry of Health; the Women’s Dermatologic Society; and the AAD for giving me the chance to participate in these wonderful international opportunities throughout my career.

Reference

1. Medenica L, Lalevic-Vasic B, Skiljevic DS. The Belgrade dermatovenereologic moulage collection: past and present. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:937-942.

Little has been written about the various types of international educational opportunities in dermatology, which include medical student electives, mentorship and scholarship programs for residents, international residency programs and conferences, and clinical or research-based fellowships (Table). After residency, there are many opportunities for teaching and volunteering in developing countries and ways to get involved in resident education. Although it may be difficult to participate in exchange programs during residency given the demanding schedules and limited vacation and elective time, international exchange programs in dermatology have become more accessible to residents and dermatologists worldwide. This exchange of ideas and information within our field promotes the advancement of scientific and clinical dermatologic insights that may not be commonplace elsewhere.

Resident Opportunities in Europe

During my internship, I received the Imrich Sarkany Non-European Memorial Scholarship from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, which facilitated my attendance at the organization’s 11th Spring Symposium in Belgrade, Serbia. I participated in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Belgrade, one of the oldest dermatologic programs in Europe, where I learned about Serbian culture, the country’s history as part of Yugoslavia, its health and medical education system, and its unique patient population that includes individuals from various ethnic groups. One of the highlights of my experience was learning about the Belgrade dermatovenereologic moulage collection (Figure), which was developed between 1925 and 1958 after the formation of University of Belgrade’s School of Medicine and the Institute of Dermatovenereology.1 In the early half of the 20th century when photographs were not yet established, the use of moulages as an artistic tool for medical education became very significant. The moulage collection in Belgrade is one of the most well known and is comprised of 350 pieces of which 280 are completely preserved while the rest are damaged.1 These moulages illustrate a wide variety of skin and venereal diseases that have been analyzed and contributed to the historical aspect of dermatologic education and medical conditions that are no longer prevalent thanks to modern medicine. Before World War I when these moulages were created, there was a high incidence of venereal diseases (eg, syphilis) and leprosy. Interestingly, most European dermatology residency programs incorporate the study of sexually transmitted infections and venereology as part of their training. In fact, many European dermatologists also use the term dermatovenereologist to describe their profession. Many of the moulages in the Belgrade collection were made by sculptors and painters, while others were made by physicians themselves, with great authenticity based on comparison of the original diagnosis to current diagnostic criteria.

I also had an opportunity to travel to Kuwait City, Kuwait, for the Kuwait Derma Update and Laser Conference when I was a research fellow at the University of Miami, Florida. In addition to learning opportunities in the form of seminars, workshops, and interactive sessions, each morning began with a visit to one of the government hospitals for a Grand Rounds discussion and presentation of difficult cases for management recommendations. The scientific program was led by Nawaf al-Mutairi, MD, the president of the conference, and involved diverse topics particularly on laser devices and modern therapies for psoriasis and vitiligo in ethnic skin, as well as how to address complications from these therapies. I first learned about platelet-rich plasma treatments and mesotherapy through a workshop at the conference, which became wildly popular in the Middle East and elsewhere during that time.

International Resident Opportunities Through the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is dedicated to international education opportunities. The Education and Volunteers Abroad Committee provides 4 grants per year to US dermatology residents who are in their second or third year of residency to participate in a rural health elective in Chinle, Arizona (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/native-american -health-service-resident-rotation-program). This 1- to 2-week elective takes place at the Native American Health Service where residents provide dermatologic care to the Navajo Nation population and work with primary health care providers to assist with diagnosis and management of dermatologic diseases.

The AAD also provides funding for 15 senior dermatology residents from the United States and Canada to participate in a 4- to 6-week elective in Gaborone, Botswana, which provides opportunities for residents to learn about the care of tropical and human immunodeficiency virus–related dermatologic conditions (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/resident-international-grant). These programs allow residents to develop image databases, perform teledermatology consultations, and practice in underserved areas with finite resources.

The AAD’s World Congress Fund Review Task Force also offers a limited number of scholarships to US and Canadian dermatology residents, fellows, or young dermatologists within 5 years of dermatology residency to attend the World Congress of Dermatology, the world’s oldest continuous international dermatology meeting, which takes place every 4 years (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/world-congress-of-dermatology). Grants also are offered for travel to dermatology meetings in Asia, Europe, and Latin America through mutual arrangements with several international dermatologic societies and the International Affairs Committee of the AAD (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/international-society-annual-meeting-travel-grant). These grants offer participants an opportunity to meet foreign colleagues and establish long-lasting professional relationships.

International Resident Opportunities Through the Women’s Dermatologic Society

The Women’s Dermatologic Society Mentorship Award Program helps to develop long-term mentoring relationships for residents and/or junior faculty that might not otherwise be possible due to distance or funding availability (http://www.womensderm.org/?page=MentorshipAward). As a recipient of this award in 2015, I was paired with Evangeline Handog, MD, current president of the International Society of Dermatology and the dermatology department chairperson at Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Muntinlupa City, Philippines. During my time in the Philippines, I was mostly at the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Manila. I also spent a day at the Asian Hospital and Medical Center, a state-of-the-art facility that is accredited by the Joint Commission International, and I attended a cosmetic dermatology workshop led by the Philippine Academy of Dermatologic Surgery Foundation, Inc. During this trip, I was surprised by the number of leprosy and human immunodeficiency virus cases that I encountered. Growing up in the United States for most of my life, I had never seen a case of leprosy. I also was very touched by the hospitality, generosity, and warmth of my mentor Dr. Handog, as well as the professors and dermatology residents that I encountered. The Women’s Dermatologic Society Mentorship Award Program exceeded my expectations, and I learned much more than I could by reading a textbook. I am very grateful for this experience and would do it again if I could.

Final Thoughts

Although it may be challenging to schedule international resident electives and opportunities while in residency training, international educational experiences allow for professional growth and development. An international medical experience can provide excellent opportunities for learning and service in remote or underserved areas in the world.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology scholarship committee; Nawaf al-Mutairi, MD, and the Kuwaiti Ministry of Health; the Women’s Dermatologic Society; and the AAD for giving me the chance to participate in these wonderful international opportunities throughout my career.

Little has been written about the various types of international educational opportunities in dermatology, which include medical student electives, mentorship and scholarship programs for residents, international residency programs and conferences, and clinical or research-based fellowships (Table). After residency, there are many opportunities for teaching and volunteering in developing countries and ways to get involved in resident education. Although it may be difficult to participate in exchange programs during residency given the demanding schedules and limited vacation and elective time, international exchange programs in dermatology have become more accessible to residents and dermatologists worldwide. This exchange of ideas and information within our field promotes the advancement of scientific and clinical dermatologic insights that may not be commonplace elsewhere.

Resident Opportunities in Europe

During my internship, I received the Imrich Sarkany Non-European Memorial Scholarship from the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, which facilitated my attendance at the organization’s 11th Spring Symposium in Belgrade, Serbia. I participated in the Department of Dermatology at the University of Belgrade, one of the oldest dermatologic programs in Europe, where I learned about Serbian culture, the country’s history as part of Yugoslavia, its health and medical education system, and its unique patient population that includes individuals from various ethnic groups. One of the highlights of my experience was learning about the Belgrade dermatovenereologic moulage collection (Figure), which was developed between 1925 and 1958 after the formation of University of Belgrade’s School of Medicine and the Institute of Dermatovenereology.1 In the early half of the 20th century when photographs were not yet established, the use of moulages as an artistic tool for medical education became very significant. The moulage collection in Belgrade is one of the most well known and is comprised of 350 pieces of which 280 are completely preserved while the rest are damaged.1 These moulages illustrate a wide variety of skin and venereal diseases that have been analyzed and contributed to the historical aspect of dermatologic education and medical conditions that are no longer prevalent thanks to modern medicine. Before World War I when these moulages were created, there was a high incidence of venereal diseases (eg, syphilis) and leprosy. Interestingly, most European dermatology residency programs incorporate the study of sexually transmitted infections and venereology as part of their training. In fact, many European dermatologists also use the term dermatovenereologist to describe their profession. Many of the moulages in the Belgrade collection were made by sculptors and painters, while others were made by physicians themselves, with great authenticity based on comparison of the original diagnosis to current diagnostic criteria.

I also had an opportunity to travel to Kuwait City, Kuwait, for the Kuwait Derma Update and Laser Conference when I was a research fellow at the University of Miami, Florida. In addition to learning opportunities in the form of seminars, workshops, and interactive sessions, each morning began with a visit to one of the government hospitals for a Grand Rounds discussion and presentation of difficult cases for management recommendations. The scientific program was led by Nawaf al-Mutairi, MD, the president of the conference, and involved diverse topics particularly on laser devices and modern therapies for psoriasis and vitiligo in ethnic skin, as well as how to address complications from these therapies. I first learned about platelet-rich plasma treatments and mesotherapy through a workshop at the conference, which became wildly popular in the Middle East and elsewhere during that time.

International Resident Opportunities Through the American Academy of Dermatology

The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) is dedicated to international education opportunities. The Education and Volunteers Abroad Committee provides 4 grants per year to US dermatology residents who are in their second or third year of residency to participate in a rural health elective in Chinle, Arizona (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/native-american -health-service-resident-rotation-program). This 1- to 2-week elective takes place at the Native American Health Service where residents provide dermatologic care to the Navajo Nation population and work with primary health care providers to assist with diagnosis and management of dermatologic diseases.

The AAD also provides funding for 15 senior dermatology residents from the United States and Canada to participate in a 4- to 6-week elective in Gaborone, Botswana, which provides opportunities for residents to learn about the care of tropical and human immunodeficiency virus–related dermatologic conditions (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/resident-international-grant). These programs allow residents to develop image databases, perform teledermatology consultations, and practice in underserved areas with finite resources.

The AAD’s World Congress Fund Review Task Force also offers a limited number of scholarships to US and Canadian dermatology residents, fellows, or young dermatologists within 5 years of dermatology residency to attend the World Congress of Dermatology, the world’s oldest continuous international dermatology meeting, which takes place every 4 years (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/world-congress-of-dermatology). Grants also are offered for travel to dermatology meetings in Asia, Europe, and Latin America through mutual arrangements with several international dermatologic societies and the International Affairs Committee of the AAD (https://www.aad.org/education/awards-grants-and-scholarships/international-society-annual-meeting-travel-grant). These grants offer participants an opportunity to meet foreign colleagues and establish long-lasting professional relationships.

International Resident Opportunities Through the Women’s Dermatologic Society

The Women’s Dermatologic Society Mentorship Award Program helps to develop long-term mentoring relationships for residents and/or junior faculty that might not otherwise be possible due to distance or funding availability (http://www.womensderm.org/?page=MentorshipAward). As a recipient of this award in 2015, I was paired with Evangeline Handog, MD, current president of the International Society of Dermatology and the dermatology department chairperson at Asian Hospital and Medical Center, Muntinlupa City, Philippines. During my time in the Philippines, I was mostly at the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, Manila. I also spent a day at the Asian Hospital and Medical Center, a state-of-the-art facility that is accredited by the Joint Commission International, and I attended a cosmetic dermatology workshop led by the Philippine Academy of Dermatologic Surgery Foundation, Inc. During this trip, I was surprised by the number of leprosy and human immunodeficiency virus cases that I encountered. Growing up in the United States for most of my life, I had never seen a case of leprosy. I also was very touched by the hospitality, generosity, and warmth of my mentor Dr. Handog, as well as the professors and dermatology residents that I encountered. The Women’s Dermatologic Society Mentorship Award Program exceeded my expectations, and I learned much more than I could by reading a textbook. I am very grateful for this experience and would do it again if I could.

Final Thoughts

Although it may be challenging to schedule international resident electives and opportunities while in residency training, international educational experiences allow for professional growth and development. An international medical experience can provide excellent opportunities for learning and service in remote or underserved areas in the world.

Acknowledgment

I would like to thank the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology scholarship committee; Nawaf al-Mutairi, MD, and the Kuwaiti Ministry of Health; the Women’s Dermatologic Society; and the AAD for giving me the chance to participate in these wonderful international opportunities throughout my career.

Reference

1. Medenica L, Lalevic-Vasic B, Skiljevic DS. The Belgrade dermatovenereologic moulage collection: past and present. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:937-942.

Reference

1. Medenica L, Lalevic-Vasic B, Skiljevic DS. The Belgrade dermatovenereologic moulage collection: past and present. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:937-942.

Dermatologic Emergencies

Dermatologic emergency may sound like an oxymoron, but there are many emergencies that dermatology residents may encounter in their careers. In some instances the skin is the primary organ that is affected, while in others cutaneous symptoms and life-threatening signs are important diagnostic clues for what may lie beneath the skin.

As residents who are occasionally on call or on consultation services, it is important for us to recognize dermatologic emergencies quickly because some of these conditions can acutely evolve and become lethal if a diagnosis is not made early in the disease course with the appropriate treatment administered. Dermatologic emergencies can range from severe drug reactions, infections, autoimmune exacerbations, and inflammatory conditions (eg, erythroderma) to environmental insults such as burns (Figure 1) and child abuse.1

Critical Infections

Some dermatologic emergencies are infectious in origin, and although these infections are most commonly bacterial (eg, necrotizing fasciitis), they also can range from viral to fungal (eg, mucormycosis) in nature. Some areas with large populations of immunocompromised patients (eg, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, organ transplant recipients) may warrant a high index of suspicion for possible zebras (rare conditions) and opportunistic infections that may quickly escalate to life-threatening situations.

Although few cutaneous manifestations in emergent infections are pathognomonic, they sometimes can be categorized according to the appearance of the primary lesion: erythrodermic (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome), maculopapular (eg, Lyme disease), purpuric/petechial (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever), pustular (eg, disseminated candidiasis), or vesicular (eg, neonatal herpes simplex virus)(Table). On consultations, dermatology residents frequently get called to evaluate hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions in inpatients (Figure 2). Aside from infectious causes, the differential diagnosis may include coagulation abnormalities (eg, concurrent anticoagulant therapies), vasculitides, poisoning, vascular disease, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, which can occasionally present with hemorrhagic lesions.1,2

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Dermatology residents may frequently encounter necrotizing fasciitis, either in clinic or on the wards (Figure 3). Recognition of the skin signs in this condition is essential to patient survival. As an intern, I once had an attending teach me that patients with necrotizing fasciitis only have a couple of hours to live. The rapid unfolding of this flesh-eating disease and its high morbidity and mortality has led to recent attention in the press and media.

Although necrotizing fasciitis may be caused by several different bacterial organisms (eg, gram positive, gram negative, polymicrobial), it usually is rapidly progressive, destroying muscle and subcutaneous tissues in a matter of hours.3 Bacteria usually enter through a traumatic or present wound and quickly move along fascial planes, destroying blood vessels and whatever subcutaneous tissues happen to be in the way. Within the first few hours, the involved area that was initially erythematous becomes indurated, woody, extremely painful, and dusky, indicating a lack of circulation to the area. Extensive debridement is required until reaching noninfected tissue that is no longer purulent, necrotic, or woody to the touch. If necrotizing fasciitis is not diagnosed and treated early, patients may lose one or several limbs and death may occur.

Key findings of necrotizing fasciitis include systemic toxicity, localized painful induration, well-defined dusky blue discoloration, and a lack of bleeding or purulent discharge on incision and squeezing of the affected tissue. Crepitation or a crackling sensation can occasionally be felt when palpating the area secondary to gas formation in the tissue, though it is not always present. Patients with necrotizing fasciitis often initially present to dermatology clinics because the first manifestation happens to be in the skin. The role of dermatologists in treating this critical condition may prompt recognition and collaboration with other specialists to reach a viable outcome for the patient.3

Drug Reactions

Cutaneous drug eruptions usually are relatively benign, consisting of a morbilliform eruption often without any other accompanying symptoms. However, sometimes these reactions can present as exfoliative dermatitis or red man syndrome in which patients can develop total body erythema with diffuse scaling and pruritus.4 Aside from drug reactions, other causes of exfoliative dermatitis such as psoriasis, atopic and seborrheic dermatitis, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma should be ruled out. Other drug eruptions that can be classified as dermatologic emergencies include leukocytoclastic vasculitis, severe urticaria or angioedema, erythema multiforme, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Severe Acne

If not treated promptly, serious cases of acne can lead to severe scarring and psychologic problems. Acne fulminans is characterized by a rapid eruption of suppurative and large, highly inflamed nodules, plaques, and cysts that result in ragged ulcerations and cicatrization of the chest, back, and occasionally the face. Systemic symptoms of fever, arthralgia, leukocytosis, and myalgia suggest an upregulation of the immune system in affected patients.

Final Comment

In summary, dermatologic emergencies do exist and some may present with characteristic skin findings. In almost all cases, collaboration with other departments such as trauma, burn, internal medicine, rheumatology, and infectious diseases is extremely helpful in diagnosing and treating these medical emergencies. Collaboration can provide insight into how brainstorming through different approaches can lead to a better outcome whether it be solving the cause of a puzzling rash in a patient with multiple comorbidities or surgically removing a bullet from a trauma patient (Figure 4). Recognition of specific cutaneous manifestations and early diagnosis of dermatologic emergencies can be lifesaving.

1. McQueen A, Martin SA, Lio PA. Derm emergencies: detecting early signs of trouble. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:71-78.

2. Bennion S. Dermatologic emergencies. In: Fitzpatrick J, Morelli J, eds. Dermatology Secrets Plus. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2011:442-452.

3. Sarani B, Strong M, Pascual J, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: current concepts and review of the literature. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:279-288.

4. Wolf R, Orion E, Marcos B, et al. Life-threatening acute adverse cutaneous drug reactions. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:171-181.

Dermatologic emergency may sound like an oxymoron, but there are many emergencies that dermatology residents may encounter in their careers. In some instances the skin is the primary organ that is affected, while in others cutaneous symptoms and life-threatening signs are important diagnostic clues for what may lie beneath the skin.

As residents who are occasionally on call or on consultation services, it is important for us to recognize dermatologic emergencies quickly because some of these conditions can acutely evolve and become lethal if a diagnosis is not made early in the disease course with the appropriate treatment administered. Dermatologic emergencies can range from severe drug reactions, infections, autoimmune exacerbations, and inflammatory conditions (eg, erythroderma) to environmental insults such as burns (Figure 1) and child abuse.1

Critical Infections

Some dermatologic emergencies are infectious in origin, and although these infections are most commonly bacterial (eg, necrotizing fasciitis), they also can range from viral to fungal (eg, mucormycosis) in nature. Some areas with large populations of immunocompromised patients (eg, human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients, organ transplant recipients) may warrant a high index of suspicion for possible zebras (rare conditions) and opportunistic infections that may quickly escalate to life-threatening situations.

Although few cutaneous manifestations in emergent infections are pathognomonic, they sometimes can be categorized according to the appearance of the primary lesion: erythrodermic (eg, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome), maculopapular (eg, Lyme disease), purpuric/petechial (eg, Rocky Mountain spotted fever), pustular (eg, disseminated candidiasis), or vesicular (eg, neonatal herpes simplex virus)(Table). On consultations, dermatology residents frequently get called to evaluate hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions in inpatients (Figure 2). Aside from infectious causes, the differential diagnosis may include coagulation abnormalities (eg, concurrent anticoagulant therapies), vasculitides, poisoning, vascular disease, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis, which can occasionally present with hemorrhagic lesions.1,2

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Dermatology residents may frequently encounter necrotizing fasciitis, either in clinic or on the wards (Figure 3). Recognition of the skin signs in this condition is essential to patient survival. As an intern, I once had an attending teach me that patients with necrotizing fasciitis only have a couple of hours to live. The rapid unfolding of this flesh-eating disease and its high morbidity and mortality has led to recent attention in the press and media.

Although necrotizing fasciitis may be caused by several different bacterial organisms (eg, gram positive, gram negative, polymicrobial), it usually is rapidly progressive, destroying muscle and subcutaneous tissues in a matter of hours.3 Bacteria usually enter through a traumatic or present wound and quickly move along fascial planes, destroying blood vessels and whatever subcutaneous tissues happen to be in the way. Within the first few hours, the involved area that was initially erythematous becomes indurated, woody, extremely painful, and dusky, indicating a lack of circulation to the area. Extensive debridement is required until reaching noninfected tissue that is no longer purulent, necrotic, or woody to the touch. If necrotizing fasciitis is not diagnosed and treated early, patients may lose one or several limbs and death may occur.

Key findings of necrotizing fasciitis include systemic toxicity, localized painful induration, well-defined dusky blue discoloration, and a lack of bleeding or purulent discharge on incision and squeezing of the affected tissue. Crepitation or a crackling sensation can occasionally be felt when palpating the area secondary to gas formation in the tissue, though it is not always present. Patients with necrotizing fasciitis often initially present to dermatology clinics because the first manifestation happens to be in the skin. The role of dermatologists in treating this critical condition may prompt recognition and collaboration with other specialists to reach a viable outcome for the patient.3

Drug Reactions

Cutaneous drug eruptions usually are relatively benign, consisting of a morbilliform eruption often without any other accompanying symptoms. However, sometimes these reactions can present as exfoliative dermatitis or red man syndrome in which patients can develop total body erythema with diffuse scaling and pruritus.4 Aside from drug reactions, other causes of exfoliative dermatitis such as psoriasis, atopic and seborrheic dermatitis, mycosis fungoides, and lymphoma should be ruled out. Other drug eruptions that can be classified as dermatologic emergencies include leukocytoclastic vasculitis, severe urticaria or angioedema, erythema multiforme, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Severe Acne