User login

Focusing on Inattention: The Diagnostic Accuracy of Brief Measures of Inattention for Detecting Delirium

Delirium is an acute neurocognitive disorder1 that affects up to 25% of older emergency department (ED) and hospitalized patients.2-4 The relationship between delirium and adverse outcomes is well documented.5-7 Delirium is a strong predictor of increased length of mechanical ventilation, longer intensive care unit and hospital stays, increased risk of falls, long-term cognitive impairment, and mortality.8-13 Delirium is frequently missed by healthcare professionals2,14-16 and goes undetected in up to 3 out of 4 patients by bedside nurses and medical practitioners in many hospital settings.14,17-22 A significant barrier to recognizing delirium is the absence of brief delirium assessments.

In an effort to improve delirium recognition in the acute care setting, there has been a concerted effort to develop and validate brief delirium assessments. To address this unmet need, 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT), the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM), and the 3-minute diagnostic assessment for CAM-defined delirium (3D-CAM) are 1- to 3-minute delirium assessments that were validated in acutely ill older patients.23 However, 1 to 3 minutes may still be too long in busy clinical environments, and briefer (<30 seconds) delirium assessments may be needed.

One potential more-rapid method to screen for delirium is to specifically test for the presence of inattention, which is a cardinal feature of delirium.24,25 Inattention can be ascertained by having the patient recite the months backwards, recite the days of the week backwards, or spell a word backwards.26 Recent studies have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of reciting the months of the year backwards for delirium. O’Regan et al.27 evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the month of the year backwards from December to July (MOTYB-6) and observed that this task was 84% sensitive and 90% specific for delirium in older patients. However, they performed the reference standard delirium assessments in patients who had a positive MOTYB-6, which can overestimate sensitivity and underestimate specificity (verification bias).28 Fick et al.29 examined the diagnostic accuracy of 20 individual elements of the 3D-CAM and observed that reciting the months of the year backwards from December to January (MOTYB-12) was 83% sensitive and 69% specific for delirium. However, this was an exploratory study that was designed to identify an element of the 3D-CAM that had the best diagnostic accuracy.

To address these limitations, we sought to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 for delirium as diagnosed by a reference standard. We also explored other brief tests of inattention such as spelling a word (“LUNCH”) backwards, reciting the days of the week backwards, 10-letter vigilance “A” task, and 5 picture recognition task.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This was a preplanned secondary analysis of a prospective observational study that validated 3 delirium assessments.30,31 This study was conducted at a tertiary care, academic ED. The local institutional review board (IRB) reviewed and approved this study. Informed consent from the patient or an authorized surrogate was obtained whenever possible. Because this was an observational study and posed minimal risk to the patient, the IRB granted a waiver of consent for patients who were both unable to provide consent and were without an authorized surrogate available in the ED or by phone.

Selection of Participants

We enrolled a convenience sample of patients between June 2010 and February 2012 Monday through Friday from 8

Research assistants approached patients who met inclusion criteria and determined if any exclusion criteria were present. If none of the exclusion criteria were present, then the research assistant reviewed the informed consent document with the patient or authorized surrogate if the patient was not capable of providing consent. If a patient was not capable of providing consent and no authorized surrogate was available, then the patient was enrolled (under the waiver of consent) as long as the patient assented to be a part of the study. Once the patient was enrolled, the research assistant contacted the physician rater and reference standard psychiatrists to approach the patient.

Measures of Inattention

An emergency physician (JHH) who had no formal training in the mental status assessment of elders administered a cognitive battery to the patient, including tests of inattention. The following inattention tasks were administered:

- Spell the word “LUNCH” backwards.30 Patients were initially allowed to spell the word “LUNCH” forwards. Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 5 errors.

- Recite the months of the year backwards from December to July.23,26,27,30,32 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 6 errors.

- Recite the days of the week backwards.23,26,33 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 7 errors.

- Ten-letter vigilance “A” task.34 The patient was given a series of 10 letters (“S-A-V-E-A-H-A-A-R-T”) every 3 seconds and was asked to squeeze the rater’s hand every time the patient heard the letter “A.” Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 10 errors.

- Five picture recognition task.34 Patients were shown 5 objects on picture cards. Afterwards, patients were shown 10 pictures with the previously shown objects intermingled. The patient had to identify which objects were seen previously in the first 5 pictures. Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 10 errors.

- Recite the months of the year backwards from December to January.29 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 12 errors.

Reference Standard for Delirium

A comprehensive consultation-liaison psychiatrist assessment was the reference standard for delirium; the diagnosis of delirium was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria.35 Three psychiatrists who each had an average of 11 years of clinical experience and regularly diagnosed delirium as part of their daily clinical practice were available to perform these assessments. To arrive at the diagnosis of delirium, they interviewed those who best understood the patient’s mental status (eg, the patient’s family members or caregivers, physician, and nurses). They also reviewed the patient’s medical record and radiology and laboratory test results. They performed bedside cognitive testing that included, but was not limited to, the Mini-Mental State Examination, Clock Drawing Test, Luria hand sequencing task, and tests for verbal fluency. A focused neurological examination was also performed (ie, screening for paraphasic errors, tremors, tone, asterixis, frontal release signs, etc.), and they also evaluated the patient for affective lability, hallucinations, and level of alertness. If the presence of delirium was still questionable, then confrontational naming, proverb interpretation or similarities, and assessments for apraxias were performed at the discretion of the psychiatrist. The psychiatrists were blinded to the physician’s assessments, and the assessments were conducted within 3 hours of each other.

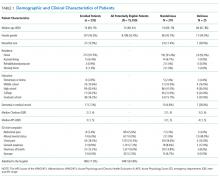

Additional Variables Collected

Using medical record review, comorbidity burden, severity of illness, and premorbid cognition were ascertained. The Charlson Comorbidity Index, a weighted index that takes into account the number and seriousness of 19 preexisting comorbid conditions, was used to quantify comorbidity burden; higher scores indicate higher comorbid burden.36,37 The Acute Physiology Score of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II was used to quantify severity of illness.38 This score is based upon the initial values of 12 routine physiologic measurements such as vital sign and laboratory abnormalities; higher scores represent higher severities of illness.38 The medical record was reviewed to ascertain the presence of premorbid cognitive impairment; any documentation of dementia in the patient’s clinical problem list or physician history and physical examination from the outpatient or inpatient settings was considered positive. The medical record review was performed by a research assistant and was double-checked for accuracy by one of the investigators (JHH).

Data Analyses

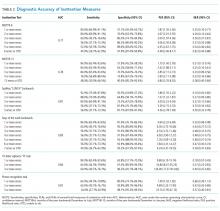

Measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were reported as proportions. Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed for each inattention task. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) was reported to provide a global measure of diagnostic accuracy. Sensitivities, specificities, positive likelihood ratios (PLRs), and negative likelihood ratios (NLRs) with their 95% CIs were calculated using the psychiatrist’s assessment as the reference standard.39 Cut-points with PLRs greater than 10 (strongly increased the likelihood of delirium) or NLRs less than 0.1 (strongly decreased the likelihood of delirium) were preferentially reported whenever possible.

All statistical analyses were performed with open source R statistical software version 3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org/), SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Delirium is frequently missed by healthcare providers because it is not routinely screened for in the acute care setting. To help address this deficiency of care, we evaluated several brief measures of inattention that take less than 30 seconds to complete. We observed that any errors made on the MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 tasks had very good sensitivities (80% and 84%) but were limited by their modest specificities (approximately 50%) for delirium. As a result, these assessments have limited clinical utility as standalone delirium screens. We also explored other commonly used brief measures of inattention and at a variety of error cutoffs. Reciting the days of the week backwards appeared to best balance sensitivity and specificity. None of the inattention measures could convincingly rule out delirium (NLR < 0.10), but the vigilance “A” and picture recognition tasks may have clinical utility in ruling in delirium (PLR > 10). Overall, all the inattention tasks, including MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12, had very good diagnostic performances based upon their AUC. However, achieving a high sensitivity often had to be sacrificed for specificity or, alternatively, achieving a high specificity had to be sacrificed for sensitivity.

Inattention has been shown to be the cardinal feature for delirium,40 and its assessment using cognitive testing has been recommended to help identify the presence of delirium according to an expert consensus panel.26 The diagnostic performance of the MOTYB-12 observed in our study is similar to a study by Fick et al., who reported that MOTYB-12 had very good sensitivity (83%) but had modest specificity (69%) with a cutoff of 1 or more errors. Hendry et al. observed that the MOTYB-12 was 91% sensitive and 50% specific using a cutoff of 4 or more errors. With regard to the MOTYB-6, our reported specificity was different from what was observed by O’Regan et al.27 Using 1 or more errors as a cutoff, they observed a much higher specificity for delirium than we did (90% vs 57%). Discordant observations regarding the diagnostic accuracy for other inattention tasks also exist. We observed that making any error on the days of the week backwards task was 84% sensitive and 82% specific for delirium, whereas Fick et al. observed a sensitivity and specificity of 50% and 94%, respectively. For the vigilance “A” task, we observed that making 2 or more errors over a series of 10 letters was 64.0% sensitive and 91.4% specific for delirium, whereas Pompei et al.41 observed that making 2 or more errors over a series of 60 letters was 51% sensitive and 77% specific for delirium.

The abovementioned discordant findings may be driven by spectrum bias, wherein the sensitivities and specificities for each inattention task may differ in different subgroups. As a result, differences in the age distribution, proportion of college graduates, history of dementia, and susceptibility to delirium can influence overall sensitivity and specificity. Objective measures of delirium, including the inattention screens studied, are particularly prone to spectrum bias.31,34 However, the strength of this approach is that the assessment of inattention becomes less reliant upon clinical judgment and allows it to be used by raters from a wide range of clinical backgrounds. On the other hand, a subjective interpretation of these inattention tasks may allow the rater to capture the subtleties of inattention (ie, decreased speed of performance in a highly intelligent and well-educated patient without dementia). The disadvantage of this approach, however, is that it is more dependent on clinical judgment and may have decreased diagnostic accuracy in those with less clinical experience or with limited training.14,42,43 These factors must be carefully considered when determining which delirium assessment to use.

Additional research is required to determine the clinical utility of these brief inattention assessments. These findings need to be further validated in larger studies, and the optimal cutoff of each task for different subgroup of patients (eg, demented vs nondemented) needs to be further clarified. It is not completely clear whether these inattention tests can serve as standalone assessments. Depending on the cutoff used, some of these assessments may have unacceptable false negative or false positive rates that may lead to increased adverse patient outcomes or increased resource utilization, respectively. Additional components or assessments may be needed to improve the diagnostic accuracy of these assessments. In addition to understanding these inattention assessments’ diagnostic accuracies, their ability to predict adverse outcomes also needs to be investigated. While a previous study observed that making any error on the MOTYB-12 task was associated with increased physical restraint use and prolonged hospital length of stay,44 these assessments’ ability to prognosticate long-term outcomes such as mortality or long-term cognition or function need to be studied. Lastly, studies should also evaluate how easily implementable these assessments are and whether improved delirium recognition leads to improved patient outcomes.

This study has several notable limitations. Though planned a priori, this was a secondary analysis of a larger investigation designed to validate 3 delirium assessments. Our sample size was also relatively small, causing our 95% CIs to overlap in most cases and limiting the statistical power to truly determine whether one measure is better than the other. We also asked the patient to recite the months backwards from December to July as well as recite the months backwards from December to January. It is possible that the patient may have performed better at going from December to January because of learning effect. Our reference standard for delirium was based upon DSM-IV-TR criteria. The new DSM-V criteria may be more restrictive and may slightly change the sensitivities and specificities of the inattention tasks. We enrolled a convenience sample and enrolled patients who were more likely to be male, have cardiovascular chief complaints, and be admitted to the hospital; as a result, selection bias may have been introduced. Lastly, this study was conducted in a single center and enrolled patients who were 65 years and older. Our findings may not be generalizable to other settings and in those who are less than 65 years of age.

CONCLUSIONS

The MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 tasks had very good sensitivities but modest specificities (approximately 50%) using any error made as a cutoff; increasing cutoff to 2 errors and 3 errors, respectively, improved their specificities (approximately 70%) with minimal impact to their sensitivities. Reciting the days of the week backwards, spelling the word “LUNCH” backwards, and the 10-letter vigilance “A” task appeared to perform the best in ruling out delirium but only moderately decreased the likelihood of delirium. The 10-letter Vigilance “A” and picture recognition task

Disclosure

This study was funded by the Emergency Medicine Foundation Career Development Award, National Institutes of Health K23AG032355, and National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01. The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

33. Hamrick I, Hafiz R, Cummings DM. Use of days of the week in a modified mini-mental state exam (M-MMSE) for detecting geriatric cognitive impairment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(4):429-435.

Delirium is an acute neurocognitive disorder1 that affects up to 25% of older emergency department (ED) and hospitalized patients.2-4 The relationship between delirium and adverse outcomes is well documented.5-7 Delirium is a strong predictor of increased length of mechanical ventilation, longer intensive care unit and hospital stays, increased risk of falls, long-term cognitive impairment, and mortality.8-13 Delirium is frequently missed by healthcare professionals2,14-16 and goes undetected in up to 3 out of 4 patients by bedside nurses and medical practitioners in many hospital settings.14,17-22 A significant barrier to recognizing delirium is the absence of brief delirium assessments.

In an effort to improve delirium recognition in the acute care setting, there has been a concerted effort to develop and validate brief delirium assessments. To address this unmet need, 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT), the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM), and the 3-minute diagnostic assessment for CAM-defined delirium (3D-CAM) are 1- to 3-minute delirium assessments that were validated in acutely ill older patients.23 However, 1 to 3 minutes may still be too long in busy clinical environments, and briefer (<30 seconds) delirium assessments may be needed.

One potential more-rapid method to screen for delirium is to specifically test for the presence of inattention, which is a cardinal feature of delirium.24,25 Inattention can be ascertained by having the patient recite the months backwards, recite the days of the week backwards, or spell a word backwards.26 Recent studies have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of reciting the months of the year backwards for delirium. O’Regan et al.27 evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the month of the year backwards from December to July (MOTYB-6) and observed that this task was 84% sensitive and 90% specific for delirium in older patients. However, they performed the reference standard delirium assessments in patients who had a positive MOTYB-6, which can overestimate sensitivity and underestimate specificity (verification bias).28 Fick et al.29 examined the diagnostic accuracy of 20 individual elements of the 3D-CAM and observed that reciting the months of the year backwards from December to January (MOTYB-12) was 83% sensitive and 69% specific for delirium. However, this was an exploratory study that was designed to identify an element of the 3D-CAM that had the best diagnostic accuracy.

To address these limitations, we sought to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 for delirium as diagnosed by a reference standard. We also explored other brief tests of inattention such as spelling a word (“LUNCH”) backwards, reciting the days of the week backwards, 10-letter vigilance “A” task, and 5 picture recognition task.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This was a preplanned secondary analysis of a prospective observational study that validated 3 delirium assessments.30,31 This study was conducted at a tertiary care, academic ED. The local institutional review board (IRB) reviewed and approved this study. Informed consent from the patient or an authorized surrogate was obtained whenever possible. Because this was an observational study and posed minimal risk to the patient, the IRB granted a waiver of consent for patients who were both unable to provide consent and were without an authorized surrogate available in the ED or by phone.

Selection of Participants

We enrolled a convenience sample of patients between June 2010 and February 2012 Monday through Friday from 8

Research assistants approached patients who met inclusion criteria and determined if any exclusion criteria were present. If none of the exclusion criteria were present, then the research assistant reviewed the informed consent document with the patient or authorized surrogate if the patient was not capable of providing consent. If a patient was not capable of providing consent and no authorized surrogate was available, then the patient was enrolled (under the waiver of consent) as long as the patient assented to be a part of the study. Once the patient was enrolled, the research assistant contacted the physician rater and reference standard psychiatrists to approach the patient.

Measures of Inattention

An emergency physician (JHH) who had no formal training in the mental status assessment of elders administered a cognitive battery to the patient, including tests of inattention. The following inattention tasks were administered:

- Spell the word “LUNCH” backwards.30 Patients were initially allowed to spell the word “LUNCH” forwards. Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 5 errors.

- Recite the months of the year backwards from December to July.23,26,27,30,32 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 6 errors.

- Recite the days of the week backwards.23,26,33 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 7 errors.

- Ten-letter vigilance “A” task.34 The patient was given a series of 10 letters (“S-A-V-E-A-H-A-A-R-T”) every 3 seconds and was asked to squeeze the rater’s hand every time the patient heard the letter “A.” Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 10 errors.

- Five picture recognition task.34 Patients were shown 5 objects on picture cards. Afterwards, patients were shown 10 pictures with the previously shown objects intermingled. The patient had to identify which objects were seen previously in the first 5 pictures. Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 10 errors.

- Recite the months of the year backwards from December to January.29 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 12 errors.

Reference Standard for Delirium

A comprehensive consultation-liaison psychiatrist assessment was the reference standard for delirium; the diagnosis of delirium was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria.35 Three psychiatrists who each had an average of 11 years of clinical experience and regularly diagnosed delirium as part of their daily clinical practice were available to perform these assessments. To arrive at the diagnosis of delirium, they interviewed those who best understood the patient’s mental status (eg, the patient’s family members or caregivers, physician, and nurses). They also reviewed the patient’s medical record and radiology and laboratory test results. They performed bedside cognitive testing that included, but was not limited to, the Mini-Mental State Examination, Clock Drawing Test, Luria hand sequencing task, and tests for verbal fluency. A focused neurological examination was also performed (ie, screening for paraphasic errors, tremors, tone, asterixis, frontal release signs, etc.), and they also evaluated the patient for affective lability, hallucinations, and level of alertness. If the presence of delirium was still questionable, then confrontational naming, proverb interpretation or similarities, and assessments for apraxias were performed at the discretion of the psychiatrist. The psychiatrists were blinded to the physician’s assessments, and the assessments were conducted within 3 hours of each other.

Additional Variables Collected

Using medical record review, comorbidity burden, severity of illness, and premorbid cognition were ascertained. The Charlson Comorbidity Index, a weighted index that takes into account the number and seriousness of 19 preexisting comorbid conditions, was used to quantify comorbidity burden; higher scores indicate higher comorbid burden.36,37 The Acute Physiology Score of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II was used to quantify severity of illness.38 This score is based upon the initial values of 12 routine physiologic measurements such as vital sign and laboratory abnormalities; higher scores represent higher severities of illness.38 The medical record was reviewed to ascertain the presence of premorbid cognitive impairment; any documentation of dementia in the patient’s clinical problem list or physician history and physical examination from the outpatient or inpatient settings was considered positive. The medical record review was performed by a research assistant and was double-checked for accuracy by one of the investigators (JHH).

Data Analyses

Measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were reported as proportions. Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed for each inattention task. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) was reported to provide a global measure of diagnostic accuracy. Sensitivities, specificities, positive likelihood ratios (PLRs), and negative likelihood ratios (NLRs) with their 95% CIs were calculated using the psychiatrist’s assessment as the reference standard.39 Cut-points with PLRs greater than 10 (strongly increased the likelihood of delirium) or NLRs less than 0.1 (strongly decreased the likelihood of delirium) were preferentially reported whenever possible.

All statistical analyses were performed with open source R statistical software version 3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org/), SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Delirium is frequently missed by healthcare providers because it is not routinely screened for in the acute care setting. To help address this deficiency of care, we evaluated several brief measures of inattention that take less than 30 seconds to complete. We observed that any errors made on the MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 tasks had very good sensitivities (80% and 84%) but were limited by their modest specificities (approximately 50%) for delirium. As a result, these assessments have limited clinical utility as standalone delirium screens. We also explored other commonly used brief measures of inattention and at a variety of error cutoffs. Reciting the days of the week backwards appeared to best balance sensitivity and specificity. None of the inattention measures could convincingly rule out delirium (NLR < 0.10), but the vigilance “A” and picture recognition tasks may have clinical utility in ruling in delirium (PLR > 10). Overall, all the inattention tasks, including MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12, had very good diagnostic performances based upon their AUC. However, achieving a high sensitivity often had to be sacrificed for specificity or, alternatively, achieving a high specificity had to be sacrificed for sensitivity.

Inattention has been shown to be the cardinal feature for delirium,40 and its assessment using cognitive testing has been recommended to help identify the presence of delirium according to an expert consensus panel.26 The diagnostic performance of the MOTYB-12 observed in our study is similar to a study by Fick et al., who reported that MOTYB-12 had very good sensitivity (83%) but had modest specificity (69%) with a cutoff of 1 or more errors. Hendry et al. observed that the MOTYB-12 was 91% sensitive and 50% specific using a cutoff of 4 or more errors. With regard to the MOTYB-6, our reported specificity was different from what was observed by O’Regan et al.27 Using 1 or more errors as a cutoff, they observed a much higher specificity for delirium than we did (90% vs 57%). Discordant observations regarding the diagnostic accuracy for other inattention tasks also exist. We observed that making any error on the days of the week backwards task was 84% sensitive and 82% specific for delirium, whereas Fick et al. observed a sensitivity and specificity of 50% and 94%, respectively. For the vigilance “A” task, we observed that making 2 or more errors over a series of 10 letters was 64.0% sensitive and 91.4% specific for delirium, whereas Pompei et al.41 observed that making 2 or more errors over a series of 60 letters was 51% sensitive and 77% specific for delirium.

The abovementioned discordant findings may be driven by spectrum bias, wherein the sensitivities and specificities for each inattention task may differ in different subgroups. As a result, differences in the age distribution, proportion of college graduates, history of dementia, and susceptibility to delirium can influence overall sensitivity and specificity. Objective measures of delirium, including the inattention screens studied, are particularly prone to spectrum bias.31,34 However, the strength of this approach is that the assessment of inattention becomes less reliant upon clinical judgment and allows it to be used by raters from a wide range of clinical backgrounds. On the other hand, a subjective interpretation of these inattention tasks may allow the rater to capture the subtleties of inattention (ie, decreased speed of performance in a highly intelligent and well-educated patient without dementia). The disadvantage of this approach, however, is that it is more dependent on clinical judgment and may have decreased diagnostic accuracy in those with less clinical experience or with limited training.14,42,43 These factors must be carefully considered when determining which delirium assessment to use.

Additional research is required to determine the clinical utility of these brief inattention assessments. These findings need to be further validated in larger studies, and the optimal cutoff of each task for different subgroup of patients (eg, demented vs nondemented) needs to be further clarified. It is not completely clear whether these inattention tests can serve as standalone assessments. Depending on the cutoff used, some of these assessments may have unacceptable false negative or false positive rates that may lead to increased adverse patient outcomes or increased resource utilization, respectively. Additional components or assessments may be needed to improve the diagnostic accuracy of these assessments. In addition to understanding these inattention assessments’ diagnostic accuracies, their ability to predict adverse outcomes also needs to be investigated. While a previous study observed that making any error on the MOTYB-12 task was associated with increased physical restraint use and prolonged hospital length of stay,44 these assessments’ ability to prognosticate long-term outcomes such as mortality or long-term cognition or function need to be studied. Lastly, studies should also evaluate how easily implementable these assessments are and whether improved delirium recognition leads to improved patient outcomes.

This study has several notable limitations. Though planned a priori, this was a secondary analysis of a larger investigation designed to validate 3 delirium assessments. Our sample size was also relatively small, causing our 95% CIs to overlap in most cases and limiting the statistical power to truly determine whether one measure is better than the other. We also asked the patient to recite the months backwards from December to July as well as recite the months backwards from December to January. It is possible that the patient may have performed better at going from December to January because of learning effect. Our reference standard for delirium was based upon DSM-IV-TR criteria. The new DSM-V criteria may be more restrictive and may slightly change the sensitivities and specificities of the inattention tasks. We enrolled a convenience sample and enrolled patients who were more likely to be male, have cardiovascular chief complaints, and be admitted to the hospital; as a result, selection bias may have been introduced. Lastly, this study was conducted in a single center and enrolled patients who were 65 years and older. Our findings may not be generalizable to other settings and in those who are less than 65 years of age.

CONCLUSIONS

The MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 tasks had very good sensitivities but modest specificities (approximately 50%) using any error made as a cutoff; increasing cutoff to 2 errors and 3 errors, respectively, improved their specificities (approximately 70%) with minimal impact to their sensitivities. Reciting the days of the week backwards, spelling the word “LUNCH” backwards, and the 10-letter vigilance “A” task appeared to perform the best in ruling out delirium but only moderately decreased the likelihood of delirium. The 10-letter Vigilance “A” and picture recognition task

Disclosure

This study was funded by the Emergency Medicine Foundation Career Development Award, National Institutes of Health K23AG032355, and National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01. The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Delirium is an acute neurocognitive disorder1 that affects up to 25% of older emergency department (ED) and hospitalized patients.2-4 The relationship between delirium and adverse outcomes is well documented.5-7 Delirium is a strong predictor of increased length of mechanical ventilation, longer intensive care unit and hospital stays, increased risk of falls, long-term cognitive impairment, and mortality.8-13 Delirium is frequently missed by healthcare professionals2,14-16 and goes undetected in up to 3 out of 4 patients by bedside nurses and medical practitioners in many hospital settings.14,17-22 A significant barrier to recognizing delirium is the absence of brief delirium assessments.

In an effort to improve delirium recognition in the acute care setting, there has been a concerted effort to develop and validate brief delirium assessments. To address this unmet need, 4 ‘A’s Test (4AT), the Brief Confusion Assessment Method (bCAM), and the 3-minute diagnostic assessment for CAM-defined delirium (3D-CAM) are 1- to 3-minute delirium assessments that were validated in acutely ill older patients.23 However, 1 to 3 minutes may still be too long in busy clinical environments, and briefer (<30 seconds) delirium assessments may be needed.

One potential more-rapid method to screen for delirium is to specifically test for the presence of inattention, which is a cardinal feature of delirium.24,25 Inattention can be ascertained by having the patient recite the months backwards, recite the days of the week backwards, or spell a word backwards.26 Recent studies have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of reciting the months of the year backwards for delirium. O’Regan et al.27 evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of the month of the year backwards from December to July (MOTYB-6) and observed that this task was 84% sensitive and 90% specific for delirium in older patients. However, they performed the reference standard delirium assessments in patients who had a positive MOTYB-6, which can overestimate sensitivity and underestimate specificity (verification bias).28 Fick et al.29 examined the diagnostic accuracy of 20 individual elements of the 3D-CAM and observed that reciting the months of the year backwards from December to January (MOTYB-12) was 83% sensitive and 69% specific for delirium. However, this was an exploratory study that was designed to identify an element of the 3D-CAM that had the best diagnostic accuracy.

To address these limitations, we sought to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 for delirium as diagnosed by a reference standard. We also explored other brief tests of inattention such as spelling a word (“LUNCH”) backwards, reciting the days of the week backwards, 10-letter vigilance “A” task, and 5 picture recognition task.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This was a preplanned secondary analysis of a prospective observational study that validated 3 delirium assessments.30,31 This study was conducted at a tertiary care, academic ED. The local institutional review board (IRB) reviewed and approved this study. Informed consent from the patient or an authorized surrogate was obtained whenever possible. Because this was an observational study and posed minimal risk to the patient, the IRB granted a waiver of consent for patients who were both unable to provide consent and were without an authorized surrogate available in the ED or by phone.

Selection of Participants

We enrolled a convenience sample of patients between June 2010 and February 2012 Monday through Friday from 8

Research assistants approached patients who met inclusion criteria and determined if any exclusion criteria were present. If none of the exclusion criteria were present, then the research assistant reviewed the informed consent document with the patient or authorized surrogate if the patient was not capable of providing consent. If a patient was not capable of providing consent and no authorized surrogate was available, then the patient was enrolled (under the waiver of consent) as long as the patient assented to be a part of the study. Once the patient was enrolled, the research assistant contacted the physician rater and reference standard psychiatrists to approach the patient.

Measures of Inattention

An emergency physician (JHH) who had no formal training in the mental status assessment of elders administered a cognitive battery to the patient, including tests of inattention. The following inattention tasks were administered:

- Spell the word “LUNCH” backwards.30 Patients were initially allowed to spell the word “LUNCH” forwards. Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 5 errors.

- Recite the months of the year backwards from December to July.23,26,27,30,32 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 6 errors.

- Recite the days of the week backwards.23,26,33 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 7 errors.

- Ten-letter vigilance “A” task.34 The patient was given a series of 10 letters (“S-A-V-E-A-H-A-A-R-T”) every 3 seconds and was asked to squeeze the rater’s hand every time the patient heard the letter “A.” Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 10 errors.

- Five picture recognition task.34 Patients were shown 5 objects on picture cards. Afterwards, patients were shown 10 pictures with the previously shown objects intermingled. The patient had to identify which objects were seen previously in the first 5 pictures. Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 10 errors.

- Recite the months of the year backwards from December to January.29 Patients who were unable to perform the task were assigned 12 errors.

Reference Standard for Delirium

A comprehensive consultation-liaison psychiatrist assessment was the reference standard for delirium; the diagnosis of delirium was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) criteria.35 Three psychiatrists who each had an average of 11 years of clinical experience and regularly diagnosed delirium as part of their daily clinical practice were available to perform these assessments. To arrive at the diagnosis of delirium, they interviewed those who best understood the patient’s mental status (eg, the patient’s family members or caregivers, physician, and nurses). They also reviewed the patient’s medical record and radiology and laboratory test results. They performed bedside cognitive testing that included, but was not limited to, the Mini-Mental State Examination, Clock Drawing Test, Luria hand sequencing task, and tests for verbal fluency. A focused neurological examination was also performed (ie, screening for paraphasic errors, tremors, tone, asterixis, frontal release signs, etc.), and they also evaluated the patient for affective lability, hallucinations, and level of alertness. If the presence of delirium was still questionable, then confrontational naming, proverb interpretation or similarities, and assessments for apraxias were performed at the discretion of the psychiatrist. The psychiatrists were blinded to the physician’s assessments, and the assessments were conducted within 3 hours of each other.

Additional Variables Collected

Using medical record review, comorbidity burden, severity of illness, and premorbid cognition were ascertained. The Charlson Comorbidity Index, a weighted index that takes into account the number and seriousness of 19 preexisting comorbid conditions, was used to quantify comorbidity burden; higher scores indicate higher comorbid burden.36,37 The Acute Physiology Score of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II was used to quantify severity of illness.38 This score is based upon the initial values of 12 routine physiologic measurements such as vital sign and laboratory abnormalities; higher scores represent higher severities of illness.38 The medical record was reviewed to ascertain the presence of premorbid cognitive impairment; any documentation of dementia in the patient’s clinical problem list or physician history and physical examination from the outpatient or inpatient settings was considered positive. The medical record review was performed by a research assistant and was double-checked for accuracy by one of the investigators (JHH).

Data Analyses

Measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables were reported as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were reported as proportions. Receiver operating characteristic curves were constructed for each inattention task. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) was reported to provide a global measure of diagnostic accuracy. Sensitivities, specificities, positive likelihood ratios (PLRs), and negative likelihood ratios (NLRs) with their 95% CIs were calculated using the psychiatrist’s assessment as the reference standard.39 Cut-points with PLRs greater than 10 (strongly increased the likelihood of delirium) or NLRs less than 0.1 (strongly decreased the likelihood of delirium) were preferentially reported whenever possible.

All statistical analyses were performed with open source R statistical software version 3.0.1 (http://www.r-project.org/), SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

Delirium is frequently missed by healthcare providers because it is not routinely screened for in the acute care setting. To help address this deficiency of care, we evaluated several brief measures of inattention that take less than 30 seconds to complete. We observed that any errors made on the MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 tasks had very good sensitivities (80% and 84%) but were limited by their modest specificities (approximately 50%) for delirium. As a result, these assessments have limited clinical utility as standalone delirium screens. We also explored other commonly used brief measures of inattention and at a variety of error cutoffs. Reciting the days of the week backwards appeared to best balance sensitivity and specificity. None of the inattention measures could convincingly rule out delirium (NLR < 0.10), but the vigilance “A” and picture recognition tasks may have clinical utility in ruling in delirium (PLR > 10). Overall, all the inattention tasks, including MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12, had very good diagnostic performances based upon their AUC. However, achieving a high sensitivity often had to be sacrificed for specificity or, alternatively, achieving a high specificity had to be sacrificed for sensitivity.

Inattention has been shown to be the cardinal feature for delirium,40 and its assessment using cognitive testing has been recommended to help identify the presence of delirium according to an expert consensus panel.26 The diagnostic performance of the MOTYB-12 observed in our study is similar to a study by Fick et al., who reported that MOTYB-12 had very good sensitivity (83%) but had modest specificity (69%) with a cutoff of 1 or more errors. Hendry et al. observed that the MOTYB-12 was 91% sensitive and 50% specific using a cutoff of 4 or more errors. With regard to the MOTYB-6, our reported specificity was different from what was observed by O’Regan et al.27 Using 1 or more errors as a cutoff, they observed a much higher specificity for delirium than we did (90% vs 57%). Discordant observations regarding the diagnostic accuracy for other inattention tasks also exist. We observed that making any error on the days of the week backwards task was 84% sensitive and 82% specific for delirium, whereas Fick et al. observed a sensitivity and specificity of 50% and 94%, respectively. For the vigilance “A” task, we observed that making 2 or more errors over a series of 10 letters was 64.0% sensitive and 91.4% specific for delirium, whereas Pompei et al.41 observed that making 2 or more errors over a series of 60 letters was 51% sensitive and 77% specific for delirium.

The abovementioned discordant findings may be driven by spectrum bias, wherein the sensitivities and specificities for each inattention task may differ in different subgroups. As a result, differences in the age distribution, proportion of college graduates, history of dementia, and susceptibility to delirium can influence overall sensitivity and specificity. Objective measures of delirium, including the inattention screens studied, are particularly prone to spectrum bias.31,34 However, the strength of this approach is that the assessment of inattention becomes less reliant upon clinical judgment and allows it to be used by raters from a wide range of clinical backgrounds. On the other hand, a subjective interpretation of these inattention tasks may allow the rater to capture the subtleties of inattention (ie, decreased speed of performance in a highly intelligent and well-educated patient without dementia). The disadvantage of this approach, however, is that it is more dependent on clinical judgment and may have decreased diagnostic accuracy in those with less clinical experience or with limited training.14,42,43 These factors must be carefully considered when determining which delirium assessment to use.

Additional research is required to determine the clinical utility of these brief inattention assessments. These findings need to be further validated in larger studies, and the optimal cutoff of each task for different subgroup of patients (eg, demented vs nondemented) needs to be further clarified. It is not completely clear whether these inattention tests can serve as standalone assessments. Depending on the cutoff used, some of these assessments may have unacceptable false negative or false positive rates that may lead to increased adverse patient outcomes or increased resource utilization, respectively. Additional components or assessments may be needed to improve the diagnostic accuracy of these assessments. In addition to understanding these inattention assessments’ diagnostic accuracies, their ability to predict adverse outcomes also needs to be investigated. While a previous study observed that making any error on the MOTYB-12 task was associated with increased physical restraint use and prolonged hospital length of stay,44 these assessments’ ability to prognosticate long-term outcomes such as mortality or long-term cognition or function need to be studied. Lastly, studies should also evaluate how easily implementable these assessments are and whether improved delirium recognition leads to improved patient outcomes.

This study has several notable limitations. Though planned a priori, this was a secondary analysis of a larger investigation designed to validate 3 delirium assessments. Our sample size was also relatively small, causing our 95% CIs to overlap in most cases and limiting the statistical power to truly determine whether one measure is better than the other. We also asked the patient to recite the months backwards from December to July as well as recite the months backwards from December to January. It is possible that the patient may have performed better at going from December to January because of learning effect. Our reference standard for delirium was based upon DSM-IV-TR criteria. The new DSM-V criteria may be more restrictive and may slightly change the sensitivities and specificities of the inattention tasks. We enrolled a convenience sample and enrolled patients who were more likely to be male, have cardiovascular chief complaints, and be admitted to the hospital; as a result, selection bias may have been introduced. Lastly, this study was conducted in a single center and enrolled patients who were 65 years and older. Our findings may not be generalizable to other settings and in those who are less than 65 years of age.

CONCLUSIONS

The MOTYB-6 and MOTYB-12 tasks had very good sensitivities but modest specificities (approximately 50%) using any error made as a cutoff; increasing cutoff to 2 errors and 3 errors, respectively, improved their specificities (approximately 70%) with minimal impact to their sensitivities. Reciting the days of the week backwards, spelling the word “LUNCH” backwards, and the 10-letter vigilance “A” task appeared to perform the best in ruling out delirium but only moderately decreased the likelihood of delirium. The 10-letter Vigilance “A” and picture recognition task

Disclosure

This study was funded by the Emergency Medicine Foundation Career Development Award, National Institutes of Health K23AG032355, and National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01. The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

33. Hamrick I, Hafiz R, Cummings DM. Use of days of the week in a modified mini-mental state exam (M-MMSE) for detecting geriatric cognitive impairment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(4):429-435.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

33. Hamrick I, Hafiz R, Cummings DM. Use of days of the week in a modified mini-mental state exam (M-MMSE) for detecting geriatric cognitive impairment. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26(4):429-435.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine