User login

Aspirin: Its risks, benefits, and optimal use in preventing cardiovascular events

A 57-year-old woman with no history of cardiovascular disease comes to the clinic for her annual evaluation. She does not have diabetes mellitus, but she does have hypertension and chronic osteoarthritis, currently treated with acetaminophen. Additionally, she admits to active tobacco use. Her systolic blood pressure is 130 mm Hg on therapy with hydrochlorothiazide. Her electrocardiogram demonstrates left ventricular hypertrophy. Her low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level is 140 mg/dL, and her high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level is 50 mg/dL. Should this patient be started on aspirin therapy?

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is an analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory agent, but its more prominent use today is as an antithrombotic agent to treat or prevent cardiovascular events. Its antithrombotic properties are due to its effects on the enzyme cyclooxygenase. However, cyclooxygenase is also involved in regulation of the gastric mucosa, and so aspirin increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Approximately 50 million people take aspirin on a daily basis to treat or prevent cardiovascular disease.1 Of these, at least half are taking more than 100 mg per day,2 reflecting the general belief that, for aspirin dosage, “more is better”—which is not true.

Additionally, recommendations about the use of aspirin were based on studies that included relatively few members of several important subgroups, such as people with diabetes without known cardiovascular disease, women, and the elderly, and thus may not reflect appropriate indications and dosages for these groups.

Here, we examine the literature, outline an individualized approach to aspirin therapy, and highlight areas for future study.

HISTORY OF ASPIRIN USE IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

- 1700s—Willow bark is used as an analgesic.

- 1897—Synthetic aspirin is developed as an antipyretic and anti-inflammatory agent.

- 1974—First landmark trial of aspirin for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction.3

- 1982—Nobel Prize awarded for discovery of aspirin mechanism.

- 1985—US Food and Drug Administration approves aspirin for the treatment and secondary prevention of acute myocardial infarction.

- 1998—The Second International Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-2) finds that giving aspirin to patients with myocardial infarction within 24 hours of presentation leads to a significant reduction in vascular deaths.4

Ongoing uncertainties

Aspirin now carries a class I indication for all patients with suspected myocardial infarction. Since there are an estimated 600,000 new coronary events and 325,000 recurrent ischemic events per year in the United States,5 the need for aspirin will continue to remain great. It is also approved to prevent and treat stroke and in patients with unstable angina.

However, questions continue to emerge about aspirin’s dosing and appropriate use in specific populations. The initial prevention trials used a wide range of doses and, as mentioned, included few women, few people with diabetes, and few elderly people. The uncertainties are especially pertinent for patients without known vascular disease, in whom the absolute risk reduction is much less, making the assessment of bleeding risk particularly important. Furthermore, the absolute risk-to-benefit assessment may be different in certain populations.

Guidelines on the use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease (Table 1)6–10 have evolved to take into account these possible disparities, and studies are taking place to further investigate aspirin use in these groups.

ASPIRIN AND GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Aspirin’s association with bleeding, particularly gastrointestinal bleeding, was recognized early as a use-limiting side effect. With or without aspirin, gastrointestinal bleeding is a common cause of morbidity and death, with an incidence of approximately 100 per 100,000 bleeding episodes in adults per year for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and 20 to 30 per 100,000 per year for lower gastrointestinal bleeding.11,12

The standard dosage (ie, 325 mg/day) is associated with a significantly higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (including fatal bleeds) than is 75 mg.13 However, even with lower doses, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding is estimated to be twice as high as with no aspirin.14

And here is the irony: studies have shown that higher doses of aspirin offer no advantage in preventing thrombotic events compared with lower doses.15 For example, the Clopidogrel Optimal Loading Dose Usage to Reduce Recurrent Events/Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Stroke Syndromes study reported a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding with standard-dose aspirin therapy than with low-dose aspirin, with no additional cardiovascular benefit with the higher dose.16

Furthermore, several other risk factors increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with aspirin use (Table 2). These risk factors are common in the general population but were not necessarily represented in participants in clinical trials. Thus, estimates of risk based on trial data most likely underestimate actual risk in the general population, and therefore, the individual patient’s risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, based on these and other factors, needs to be taken into consideration.

ASPIRIN IN PATIENTS WITH CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Randomized clinical trials have validated the benefits of aspirin in secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients who have had a myocardial infarction. Patients with coronary disease who withdraw from aspirin therapy or otherwise do not adhere to it have a risk of cardiovascular events three times higher than those who stay with it.17

Despite the strong data, however, several issues and questions remain about the use of aspirin for secondary prevention.

Bleeding risk must be considered, since gastrointestinal bleeding is associated with a higher risk of death and myocardial infarction in patients with cardiovascular disease.18 Many patients with coronary disease are on more than one antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy for concomitant conditions such as atrial fibrillation or because they underwent a percutaneous intervention, which further increases the risk of bleeding.

This bleeding risk is reflected in changes in the most recent recommendations for aspirin dosing after percutaneous coronary intervention. Earlier guidelines advocated use of either 162 or 325 mg after the procedure. However, the most recent update (in 2011) now supports 81 mg for maintenance dosing after intervention.7

Patients with coronary disease but without prior myocardial infarction or intervention. Current guidelines recommend 75 to 162 mg of aspirin in all patients with coronary artery disease.6 However, this group is diverse and includes patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, patients with chronic stable angina, and patients with asymptomatic coronary artery disease found on imaging studies. The magnitude of benefit is not clear for those who have no symptoms or who have stable angina.

Most of the evidence supporting aspirin use in chronic angina came from a single trial in Sweden, in which 2,000 patients with chronic stable angina were given either 75 mg daily or placebo. Those who received aspirin had a 34% lower rate of myocardial infarction and sudden death.19

A substudy of the Physicians’ Health Study, with fewer patients, also noted a significant reduction in the rate of first myocardial infarction. The dose of aspirin in this study was 325 mg every other day.20

In the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, 70% of women with stable cardiovascular disease taking aspirin were taking 325 mg daily.21 This study demonstrated a significant reduction in the cardiovascular mortality rate, which supports current guidelines, and found no difference in outcomes with doses of 81 mg compared with 325 mg.21 This again corroborates that low-dose aspirin is preferential to standard-dose aspirin in women with cardiovascular disease.

These findings have not been validated in larger prospective trials. Thus, current guidelines for aspirin use may reflect extrapolation of aspirin benefit from higher-risk patients to lower-risk patients.

Nevertheless, although the debate continues, it has generally been accepted that in patients who are at high risk of vascular disease or who have had a myocardial infarction, the benefits of aspirin—a 20% relative reduction in vascular events22—clearly outweigh the risks.

ASPIRIN FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION

Assessing risk vs benefit is more complex when considering populations without known cardiovascular disease.

Only a few studies have specifically evaluated the use of aspirin for primary prevention (Table 3).23–31 The initial trials were in male physicians in the United Kingdom and the United States in the late 1980s and had somewhat conflicting results. A British study did not find a significant reduction in myocardial infarction,23 but the US Physician’s Health Study study did: the relative risk was 0.56 (95% confidence interval 0.45–0.70, P < .00001).24 The US study had more than four times the number of participants, used different dosing (325 mg every other day compared with 500 or 300 mg daily in the British study), and had a higher rate of compliance.

Several studies over the next decade demonstrated variable but significant reductions in cardiovascular events as well.25–27

A meta-analysis of primary prevention trials of aspirin was published in 2009.22 Although the relative risk reduction was similar in primary and secondary prevention, the absolute risk reduction in primary prevention was not nearly as great as in secondary prevention.

These findings are somewhat difficult to interpret, as the component trials included a wide spectrum of patients, ranging from healthy people with no symptoms and no known risk factors to those with limited risk factors. The trials were also performed over several decades during which primary prevention strategies were evolving. Additionally, most of the participants were middle-aged, nondiabetic men, so the results may not necessarily apply to people with diabetes, to women, or to the elderly. Thus, the pooled data in favor of aspirin for primary prevention may not be as broadly applicable to the general population as was once thought.

Aspirin for primary prevention in women

Guidelines for aspirin use in primary prevention were initially thought to be equally applicable to both sexes. However, concerns about the relatively low number of women participating in the studies and the possible mechanistic differences in aspirin efficacy in men vs women prompted further study.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that aspirin was associated with a 12% relative reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events in women and 14% in men. On the other hand, for stroke, the relative risk reduction was 17% in women, while men had no benefit.32

Most of the women in this meta-analysis were participants in the Women’s Health Study, and they were at low baseline risk.28 Although only about 10% of patients in this study were over age 65, this older group accounted for most of the benefit: these older women had a 26% risk reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events and 30% reduction in stroke.

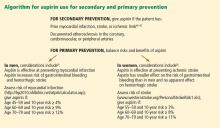

Thus, for women, aspirin seems to become effective for primary prevention at an older age than in men, and the guidelines have been changed accordingly (Figure 1).

More women should be taking aspirin than actually are. For example, Rivera et al33 found that only 41% of eligible women were receiving aspirin for primary prevention and 48% of eligible women were receiving it for secondary prevention.

People with diabetes

People with diabetes without overt cardiovascular disease are at higher risk of cardiovascular events than age- and sex-matched controls.34 On the other hand, people with diabetes may be more prone to aspirin resistance and may not derive as much cardiovascular benefit from aspirin.

Early primary prevention studies included few people with diabetes. Subsequent meta-analyses of trials that used a wide range of aspirin doses found a relative risk reduction of 9%, which was not statistically significant.9,35,36

But there is some evidence that people with diabetes, with37 and without22 coronary disease, may be at higher inherent risk of bleeding than people without diabetes. Although aspirin may not necessarily increase the risk of bleeding in diabetic patients, recent data suggest no benefit in terms of a reduction in vascular events.38

The balance of risk vs benefit for aspirin in this special population is not clear, although some argue that these patients should be treated somewhere on the spectrum of risk between primary and secondary prevention.

The US Preventive Services Task Force did not differentiate between people with or without diabetes in its 2009 guidelines for aspirin for primary prevention.8 However, the debate is reflected in a change in 2010 American College of Cardiology/American Diabetes Association guidelines regarding aspirin use in people with diabetes without known cardiovascular disease.39 As opposed to earlier recommendations from these organizations in favor of aspirin for all people with diabetes regardless of 10-year risk, current recommendations advise low-dose aspirin (81–162 mg) for diabetic patients without known vascular disease who have a greater than 10% risk of a cardiovascular event and are not at increased risk of bleeding.

These changes were based on the findings of two trials: the Prevention and Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes Trial (POPADAD) and the Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) study. These did not show a statistically significant benefit in prevention of cardiovascular events with aspirin.29,30

After the new guidelines came out, a meta-analysis further bolstered its recommendations. 40 In seven randomized clinical trials in 11,000 patients, the relative risk reduction was 9% with aspirin, which did not reach statistical significance.

Statins may dilute the benefit of aspirin

The use of statins has been increasing, and this trend may have played a role in the marginal benefit of aspirin therapy in these recent studies. In the Japanese trial, approximately 25% of the patients were known to be using a statin; the percentage of statin use was not reported specifically in POPADAD, but both of these studies were published in 2008, when the proportion of diabetic patients taking a statin would be expected to be higher than in earlier primary prevention trials, which were performed primarily in the 1990s. Thus, the beneficial effects of statins may have somewhat diluted the risk reduction attributable to aspirin.

Trials under way in patients with diabetes

The evolving and somewhat conflicting guidelines highlight the need for further study in patients with diabetes. To address this area, two trials are in progress: the Aspirin and Simvastatin Combination for Cardiovascular Events Prevention Trial in Diabetes (ACCEPT-D) and A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes (ASCEND).41,42

ACCEPT-D is testing low-dose aspirin (100 mg daily) in diabetic patients who are also on simvastatin. This study also includes prespecified subgroups stratified by sex, age, and baseline lipid levels.

The ASCEND trial will use the same aspirin dose as ACCEPT-D, with a target enrollment of 10,000 patients with diabetes without known vascular disease.

More frequent dosing for people with diabetes?

Although not supported by current guidelines, recent work has suggested that people with diabetes may need more-frequent dosing of aspirin.43 This topic warrants further investigation.

Aspirin as primary prevention in elderly patients

The incidence of cardiovascular events increases with age37—but so does the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.44 Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is especially worrisome in the elderly, in whom the estimated case-fatality rate is high.12 Assessment of risk and benefit is particularly important in patients over age 65 without known coronary disease.

Uncertainty about aspirin use in this population is reflected in the most recent US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, which do not advocate either for or against regular aspirin use for primary prevention in those over the age of 80.

Data on this topic from clinical trials are limited. The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration (2009) found that although age is associated with a risk of major coronary events similar to that of other traditional risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and tobacco use, older age is also associated with the highest risk of major extracranial bleeding.22

Because of the lack of data in this population, several studies are currently under way. The Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial is studying 100 mg daily in nondiabetic patients without known cardiovascular disease who are age 70 and older.45 An additional trial will study patients age 60 to 85 with concurrent diagnoses of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes and will test the same aspirin dose as in ASPREE.46 These trials should provide further insight into the safety and efficacy of aspirin for primary prevention in the elderly.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Aspirin remains a cornerstone of therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease and in secondary prevention of adverse cardiovascular events, but its role in primary prevention remains under scrutiny. Recommendations have evolved to reflect emerging data in special populations, and an algorithm based on Framingham risk assessment in men for myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke assessment in women for assessing appropriateness of aspirin therapy based on currently available guidelines is presented in Figure 1.6,8,47–49 Targeted studies have advanced our understanding of aspirin use in women, and future studies in people with diabetes and in the elderly should provide further insight into the role of aspirin for primary prevention in these specific groups as well.

Additionally, the range of doses used in clinical studies has propagated the general misperception that higher doses of aspirin are more efficacious. Future studies should continue to use lower doses of aspirin to minimize bleeding risk with an added focus on re-examining its net benefit in the modern era of increasing statin use, which may reduce the absolute risk reduction attributable to aspirin.

One particular area of debate is whether enteric coating can result in functional aspirin resistance. Grosser et al50 found that sustained aspirin resistance was rare, and “pseudoresistance” was related to the use of a single enteric-coated aspirin instead of immediate-release aspirin in people who had not been taking aspirin up to then. This complements an earlier study, which found that enteric-coated aspirin had an appropriate effect when given for 7 days.51 Therefore, for patients who have not been taking aspirin, the first dose should always be immediate-release, not enteric coated.

SHOULD OUR PATIENT RECEIVE ASPIRIN?

The patient we described at the beginning of this article has several risk factors—hypertension, dyslipidemia, left ventricular hypertrophy, and smoking—but no known cardiovascular disease as yet. Her risk of an adverse cardiovascular event appears moderate. However, her 10-year risk of stroke by the Framingham risk calculation is 10%, which would qualify her for aspirin for primary prevention. Of particular note is that the significance of left ventricular hypertrophy as a risk factor for stroke in women is higher than in men and in our case accounts for half of this patient’s risk.

We should explain to the patient that the anticipated benefits of aspirin for stroke prevention outweigh bleeding risks, and thus aspirin therapy would be recommended. However, with her elevated LDL-cholesterol, she may benefit from a statin, which could lessen the relative risk reduction from additional aspirin use.

- Chan FK, Graham DY. Review article: prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastrointestinal complications—review and recommendations based on risk assessment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19:1051–1061.

- Peters RJ, Mehta SR, Fox KA, et al; Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) Trial Investigators. Effects of aspirin dose when used alone or in combination with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: observations from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) study. Circulation 2003; 108:1682–1687.

- Elwood PC, Cochrane AL, Burr ML, et al. A randomized controlled trial of acetyl salicylic acid in the secondary prevention of mortality from myocardial infarction. Br Med J 1974; 1:436–440.

- Baigent C, Collins R, Appleby P, Parish S, Sleight P, Peto R. ISIS-2: 10 year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. The ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. BMJ 1998; 316:1337–1343.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123:e18–e209.

- Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:2432–2446.

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:e44–e122.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:396–404.

- Pignone M, Alberts MJ, Colwell JA, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, a scientific statement of the American Heart Association, and an expert consensus document of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2010; 121:2694–2701.

- Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123:1243–1262.

- Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005; 34:643–664.

- Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ 1995; 311:222–226.

- Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, Steinhubl SR. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2007; 297:2018–2024.

- Weil J, Colin-Jones D, Langman M, et al. Prophylactic aspirin and risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. BMJ 1995; 310:827–830.

- Reilly IA, FitzGerald GA. Inhibition of thromboxane formation in vivo and ex vivo: implications for therapy with platelet inhibitory drugs. Blood 1987; 69:180–186.

- CURRENT-OASIS 7 Investigators; Mehta SR, Bassand JP, Chrolavicius S, et al. Dose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:930–942.

- Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2006; 27:2667–2674.

- Berger PB, Bhatt DL, Fuster V, et al; CHARISMA Investigators. Bleeding complications with dual antiplatelet therapy among patients with stable vascular disease or risk factors for vascular disease: results from the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) trial. Circulation 2010; 121:2575–2583.

- Juul-Möller S, Edvardsson N, Jahnmatz B, Rosén A, Sørensen S, Omblus R. Double-blind trial of aspirin in primary prevention of myocardial infarction in patients with stable chronic angina pectoris. The Swedish Angina Pectoris Aspirin Trial (SAPAT) Group. Lancet 1992; 340:1421–1425.

- Ridker PM, Manson JE, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Low-dose aspirin therapy for chronic stable angina. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:835–839.

- Berger JS, Brown DL, Burke GL, et al. Aspirin use, dose, and clinical outcomes in postmenopausal women with stable cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2009; 2:78–87.

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009; 373:1849–1860.

- Peto R, Gray R, Collins R, et al. Randomised trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988; 296:313–316.

- Final report on the aspirin component of the ongoing Physicians’ Health Study. Steering Committee of the Physicians’ Health Study Research Group. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:129–135.

- Thrombosis prevention trial: randomised trial of low-intensity oral anticoagulation with warfarin and low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. The Medical Research Council’s General Practice Research Framework. Lancet 1998; 351:233–241.

- de Gaetano GCollaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project. Low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in people at cardiovascular risk: a randomised trial in general practice. Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project. Lancet 2001; 357:89–95.

- Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet 1998; 351:1755–1762.

- Ridker PM, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1293–1304.

- Belch J, MacCuish A, Campbell I, et al; Prevention of Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes Study Group; Diabetes Registry Group; Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh. The prevention of progression of arterial disease and diabetes (POPADAD) trial: factorial randomised placebo controlled trial of aspirin and antioxidants in patients with diabetes and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease. BMJ 2008; 337:a1840.

- Ogawa H, Nakayama M, Morimoto T, et al; Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) Trial Investigators. Low-dose aspirin for primary prevention of atherosclerotic events in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 300:2134–2141.

- Fowkes FG, Price JF, Stewart MC, et al; Aspirin for Asymptomatic Atherosclerosis Trialists. Aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular events in a general population screened for a low ankle brachial index: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010; 303:841–848.

- Berger JS, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, Pangrazzi I, Tognoni G, Brown DL. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: a sex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 2006; 295:306–313.

- Rivera CM, Song J, Copeland L, Buirge C, Ory M, McNeal CJ. Underuse of aspirin for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease events in women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012; 21:379–387.

- Wilson R, Gazzala J, House J. Aspirin in primary and secondary prevention in elderly adults revisited. South Med J 2012; 105:82–86.

- De Berardis G, Sacco M, Strippoli GF, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2009; 339:b4531.

- Zhang C, Sun A, Zhang P, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010; 87:211–218.

- Moukarbel GV, Signorovitch JE, Pfeffer MA, et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding in high risk survivors of myocardial infarction: the VALIANT Trial. Eur Heart J 2009; 30:2226–2232.

- De Berardis G, Lucisano G, D’Ettorre A, et al. Association of aspirin use with major bleeding in patients with and without diabetes. JAMA 2012; 307:2286–2294.

- Pignone M, Alberts MJ, Colwell JA, et al; American Diabetes Association; American Heart Association; American College of Cardiology Foundation. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55:2878–2886.

- Butalia S, Leung AA, Ghali WA, Rabi DM. Aspirin effect on the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2011; 10:25.

- De Berardis G, Sacco M, Evangelista V, et al; ACCEPT-D Study Group. Aspirin and Simvastatin Combination for Cardiovascular Events Prevention Trial in Diabetes (ACCEPT-D): design of a randomized study of the efficacy of low-dose aspirin in the prevention of cardiovascular events in subjects with diabetes mellitus treated with statins. Trials 2007; 8:21.

- British Heart Foundation. ASCEND: A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes. http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/ascend. Accessed April 1, 2013.

- Rocca B, Santilli F, Pitocco D, et al. The recovery of platelet cyclooxygenase activity explains interindividual variability in responsiveness to low-dose aspirin in patients with and without diabetes. J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10:1220–1230.

- Hernández-Díaz S, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Cardioprotective aspirin users and their excess risk for upper gastrointestinal complications. BMC Med 2006; 4:22.

- Nelson MR, Reid CM, Ames DA, et al. Feasibility of conducting a primary prevention trial of low-dose aspirin for major adverse cardiovascular events in older people in Australia: results from the ASPirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) pilot study. Med J Aust 2008; 189:105–109.

- Teramoto T, Shimada K, Uchiyama S, et al. Rationale, design, and baseline data of the Japanese Primary Prevention Project (JPPP)—a randomized, open-label, controlled trial of aspirin versus no aspirin in patients with multiple risk factors for vascular events. Am Heart J 2010; 159:361–369.e4.

- Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al; American College of Cardiology; American Heart Association; Canadian Cardiovascular Society. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction—executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to revise the 1999 guidelines for the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 44:671–719.

- Brott TG, Halperin JL, Abbara S, et al. 2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery Developed in Collaboration With the American Academy of Neurology and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:e16–e94.

- Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Family Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:e215–e367.

- Grosser T, Fries S, Lawson JA, Kapoor SC, Grant GR, Fitzgerald GA. Drug resistance and pseudoresistance: An unintended consequence of enteric coating aspirin. Circulation 2012; Epub ahead of print.

- Karha J, Rajagopal V, Kottke-Marchant K, Bhatt DL. Lack of effect of enteric coating on aspirin-induced inhibition of platelet aggregation in healthy volunteers. Am Heart J 2006; 151:976.e7–e11.

A 57-year-old woman with no history of cardiovascular disease comes to the clinic for her annual evaluation. She does not have diabetes mellitus, but she does have hypertension and chronic osteoarthritis, currently treated with acetaminophen. Additionally, she admits to active tobacco use. Her systolic blood pressure is 130 mm Hg on therapy with hydrochlorothiazide. Her electrocardiogram demonstrates left ventricular hypertrophy. Her low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level is 140 mg/dL, and her high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level is 50 mg/dL. Should this patient be started on aspirin therapy?

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is an analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory agent, but its more prominent use today is as an antithrombotic agent to treat or prevent cardiovascular events. Its antithrombotic properties are due to its effects on the enzyme cyclooxygenase. However, cyclooxygenase is also involved in regulation of the gastric mucosa, and so aspirin increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Approximately 50 million people take aspirin on a daily basis to treat or prevent cardiovascular disease.1 Of these, at least half are taking more than 100 mg per day,2 reflecting the general belief that, for aspirin dosage, “more is better”—which is not true.

Additionally, recommendations about the use of aspirin were based on studies that included relatively few members of several important subgroups, such as people with diabetes without known cardiovascular disease, women, and the elderly, and thus may not reflect appropriate indications and dosages for these groups.

Here, we examine the literature, outline an individualized approach to aspirin therapy, and highlight areas for future study.

HISTORY OF ASPIRIN USE IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

- 1700s—Willow bark is used as an analgesic.

- 1897—Synthetic aspirin is developed as an antipyretic and anti-inflammatory agent.

- 1974—First landmark trial of aspirin for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction.3

- 1982—Nobel Prize awarded for discovery of aspirin mechanism.

- 1985—US Food and Drug Administration approves aspirin for the treatment and secondary prevention of acute myocardial infarction.

- 1998—The Second International Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-2) finds that giving aspirin to patients with myocardial infarction within 24 hours of presentation leads to a significant reduction in vascular deaths.4

Ongoing uncertainties

Aspirin now carries a class I indication for all patients with suspected myocardial infarction. Since there are an estimated 600,000 new coronary events and 325,000 recurrent ischemic events per year in the United States,5 the need for aspirin will continue to remain great. It is also approved to prevent and treat stroke and in patients with unstable angina.

However, questions continue to emerge about aspirin’s dosing and appropriate use in specific populations. The initial prevention trials used a wide range of doses and, as mentioned, included few women, few people with diabetes, and few elderly people. The uncertainties are especially pertinent for patients without known vascular disease, in whom the absolute risk reduction is much less, making the assessment of bleeding risk particularly important. Furthermore, the absolute risk-to-benefit assessment may be different in certain populations.

Guidelines on the use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease (Table 1)6–10 have evolved to take into account these possible disparities, and studies are taking place to further investigate aspirin use in these groups.

ASPIRIN AND GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Aspirin’s association with bleeding, particularly gastrointestinal bleeding, was recognized early as a use-limiting side effect. With or without aspirin, gastrointestinal bleeding is a common cause of morbidity and death, with an incidence of approximately 100 per 100,000 bleeding episodes in adults per year for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and 20 to 30 per 100,000 per year for lower gastrointestinal bleeding.11,12

The standard dosage (ie, 325 mg/day) is associated with a significantly higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (including fatal bleeds) than is 75 mg.13 However, even with lower doses, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding is estimated to be twice as high as with no aspirin.14

And here is the irony: studies have shown that higher doses of aspirin offer no advantage in preventing thrombotic events compared with lower doses.15 For example, the Clopidogrel Optimal Loading Dose Usage to Reduce Recurrent Events/Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Stroke Syndromes study reported a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding with standard-dose aspirin therapy than with low-dose aspirin, with no additional cardiovascular benefit with the higher dose.16

Furthermore, several other risk factors increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with aspirin use (Table 2). These risk factors are common in the general population but were not necessarily represented in participants in clinical trials. Thus, estimates of risk based on trial data most likely underestimate actual risk in the general population, and therefore, the individual patient’s risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, based on these and other factors, needs to be taken into consideration.

ASPIRIN IN PATIENTS WITH CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Randomized clinical trials have validated the benefits of aspirin in secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients who have had a myocardial infarction. Patients with coronary disease who withdraw from aspirin therapy or otherwise do not adhere to it have a risk of cardiovascular events three times higher than those who stay with it.17

Despite the strong data, however, several issues and questions remain about the use of aspirin for secondary prevention.

Bleeding risk must be considered, since gastrointestinal bleeding is associated with a higher risk of death and myocardial infarction in patients with cardiovascular disease.18 Many patients with coronary disease are on more than one antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy for concomitant conditions such as atrial fibrillation or because they underwent a percutaneous intervention, which further increases the risk of bleeding.

This bleeding risk is reflected in changes in the most recent recommendations for aspirin dosing after percutaneous coronary intervention. Earlier guidelines advocated use of either 162 or 325 mg after the procedure. However, the most recent update (in 2011) now supports 81 mg for maintenance dosing after intervention.7

Patients with coronary disease but without prior myocardial infarction or intervention. Current guidelines recommend 75 to 162 mg of aspirin in all patients with coronary artery disease.6 However, this group is diverse and includes patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, patients with chronic stable angina, and patients with asymptomatic coronary artery disease found on imaging studies. The magnitude of benefit is not clear for those who have no symptoms or who have stable angina.

Most of the evidence supporting aspirin use in chronic angina came from a single trial in Sweden, in which 2,000 patients with chronic stable angina were given either 75 mg daily or placebo. Those who received aspirin had a 34% lower rate of myocardial infarction and sudden death.19

A substudy of the Physicians’ Health Study, with fewer patients, also noted a significant reduction in the rate of first myocardial infarction. The dose of aspirin in this study was 325 mg every other day.20

In the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, 70% of women with stable cardiovascular disease taking aspirin were taking 325 mg daily.21 This study demonstrated a significant reduction in the cardiovascular mortality rate, which supports current guidelines, and found no difference in outcomes with doses of 81 mg compared with 325 mg.21 This again corroborates that low-dose aspirin is preferential to standard-dose aspirin in women with cardiovascular disease.

These findings have not been validated in larger prospective trials. Thus, current guidelines for aspirin use may reflect extrapolation of aspirin benefit from higher-risk patients to lower-risk patients.

Nevertheless, although the debate continues, it has generally been accepted that in patients who are at high risk of vascular disease or who have had a myocardial infarction, the benefits of aspirin—a 20% relative reduction in vascular events22—clearly outweigh the risks.

ASPIRIN FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION

Assessing risk vs benefit is more complex when considering populations without known cardiovascular disease.

Only a few studies have specifically evaluated the use of aspirin for primary prevention (Table 3).23–31 The initial trials were in male physicians in the United Kingdom and the United States in the late 1980s and had somewhat conflicting results. A British study did not find a significant reduction in myocardial infarction,23 but the US Physician’s Health Study study did: the relative risk was 0.56 (95% confidence interval 0.45–0.70, P < .00001).24 The US study had more than four times the number of participants, used different dosing (325 mg every other day compared with 500 or 300 mg daily in the British study), and had a higher rate of compliance.

Several studies over the next decade demonstrated variable but significant reductions in cardiovascular events as well.25–27

A meta-analysis of primary prevention trials of aspirin was published in 2009.22 Although the relative risk reduction was similar in primary and secondary prevention, the absolute risk reduction in primary prevention was not nearly as great as in secondary prevention.

These findings are somewhat difficult to interpret, as the component trials included a wide spectrum of patients, ranging from healthy people with no symptoms and no known risk factors to those with limited risk factors. The trials were also performed over several decades during which primary prevention strategies were evolving. Additionally, most of the participants were middle-aged, nondiabetic men, so the results may not necessarily apply to people with diabetes, to women, or to the elderly. Thus, the pooled data in favor of aspirin for primary prevention may not be as broadly applicable to the general population as was once thought.

Aspirin for primary prevention in women

Guidelines for aspirin use in primary prevention were initially thought to be equally applicable to both sexes. However, concerns about the relatively low number of women participating in the studies and the possible mechanistic differences in aspirin efficacy in men vs women prompted further study.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that aspirin was associated with a 12% relative reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events in women and 14% in men. On the other hand, for stroke, the relative risk reduction was 17% in women, while men had no benefit.32

Most of the women in this meta-analysis were participants in the Women’s Health Study, and they were at low baseline risk.28 Although only about 10% of patients in this study were over age 65, this older group accounted for most of the benefit: these older women had a 26% risk reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events and 30% reduction in stroke.

Thus, for women, aspirin seems to become effective for primary prevention at an older age than in men, and the guidelines have been changed accordingly (Figure 1).

More women should be taking aspirin than actually are. For example, Rivera et al33 found that only 41% of eligible women were receiving aspirin for primary prevention and 48% of eligible women were receiving it for secondary prevention.

People with diabetes

People with diabetes without overt cardiovascular disease are at higher risk of cardiovascular events than age- and sex-matched controls.34 On the other hand, people with diabetes may be more prone to aspirin resistance and may not derive as much cardiovascular benefit from aspirin.

Early primary prevention studies included few people with diabetes. Subsequent meta-analyses of trials that used a wide range of aspirin doses found a relative risk reduction of 9%, which was not statistically significant.9,35,36

But there is some evidence that people with diabetes, with37 and without22 coronary disease, may be at higher inherent risk of bleeding than people without diabetes. Although aspirin may not necessarily increase the risk of bleeding in diabetic patients, recent data suggest no benefit in terms of a reduction in vascular events.38

The balance of risk vs benefit for aspirin in this special population is not clear, although some argue that these patients should be treated somewhere on the spectrum of risk between primary and secondary prevention.

The US Preventive Services Task Force did not differentiate between people with or without diabetes in its 2009 guidelines for aspirin for primary prevention.8 However, the debate is reflected in a change in 2010 American College of Cardiology/American Diabetes Association guidelines regarding aspirin use in people with diabetes without known cardiovascular disease.39 As opposed to earlier recommendations from these organizations in favor of aspirin for all people with diabetes regardless of 10-year risk, current recommendations advise low-dose aspirin (81–162 mg) for diabetic patients without known vascular disease who have a greater than 10% risk of a cardiovascular event and are not at increased risk of bleeding.

These changes were based on the findings of two trials: the Prevention and Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes Trial (POPADAD) and the Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) study. These did not show a statistically significant benefit in prevention of cardiovascular events with aspirin.29,30

After the new guidelines came out, a meta-analysis further bolstered its recommendations. 40 In seven randomized clinical trials in 11,000 patients, the relative risk reduction was 9% with aspirin, which did not reach statistical significance.

Statins may dilute the benefit of aspirin

The use of statins has been increasing, and this trend may have played a role in the marginal benefit of aspirin therapy in these recent studies. In the Japanese trial, approximately 25% of the patients were known to be using a statin; the percentage of statin use was not reported specifically in POPADAD, but both of these studies were published in 2008, when the proportion of diabetic patients taking a statin would be expected to be higher than in earlier primary prevention trials, which were performed primarily in the 1990s. Thus, the beneficial effects of statins may have somewhat diluted the risk reduction attributable to aspirin.

Trials under way in patients with diabetes

The evolving and somewhat conflicting guidelines highlight the need for further study in patients with diabetes. To address this area, two trials are in progress: the Aspirin and Simvastatin Combination for Cardiovascular Events Prevention Trial in Diabetes (ACCEPT-D) and A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes (ASCEND).41,42

ACCEPT-D is testing low-dose aspirin (100 mg daily) in diabetic patients who are also on simvastatin. This study also includes prespecified subgroups stratified by sex, age, and baseline lipid levels.

The ASCEND trial will use the same aspirin dose as ACCEPT-D, with a target enrollment of 10,000 patients with diabetes without known vascular disease.

More frequent dosing for people with diabetes?

Although not supported by current guidelines, recent work has suggested that people with diabetes may need more-frequent dosing of aspirin.43 This topic warrants further investigation.

Aspirin as primary prevention in elderly patients

The incidence of cardiovascular events increases with age37—but so does the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.44 Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is especially worrisome in the elderly, in whom the estimated case-fatality rate is high.12 Assessment of risk and benefit is particularly important in patients over age 65 without known coronary disease.

Uncertainty about aspirin use in this population is reflected in the most recent US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, which do not advocate either for or against regular aspirin use for primary prevention in those over the age of 80.

Data on this topic from clinical trials are limited. The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration (2009) found that although age is associated with a risk of major coronary events similar to that of other traditional risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and tobacco use, older age is also associated with the highest risk of major extracranial bleeding.22

Because of the lack of data in this population, several studies are currently under way. The Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial is studying 100 mg daily in nondiabetic patients without known cardiovascular disease who are age 70 and older.45 An additional trial will study patients age 60 to 85 with concurrent diagnoses of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes and will test the same aspirin dose as in ASPREE.46 These trials should provide further insight into the safety and efficacy of aspirin for primary prevention in the elderly.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Aspirin remains a cornerstone of therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease and in secondary prevention of adverse cardiovascular events, but its role in primary prevention remains under scrutiny. Recommendations have evolved to reflect emerging data in special populations, and an algorithm based on Framingham risk assessment in men for myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke assessment in women for assessing appropriateness of aspirin therapy based on currently available guidelines is presented in Figure 1.6,8,47–49 Targeted studies have advanced our understanding of aspirin use in women, and future studies in people with diabetes and in the elderly should provide further insight into the role of aspirin for primary prevention in these specific groups as well.

Additionally, the range of doses used in clinical studies has propagated the general misperception that higher doses of aspirin are more efficacious. Future studies should continue to use lower doses of aspirin to minimize bleeding risk with an added focus on re-examining its net benefit in the modern era of increasing statin use, which may reduce the absolute risk reduction attributable to aspirin.

One particular area of debate is whether enteric coating can result in functional aspirin resistance. Grosser et al50 found that sustained aspirin resistance was rare, and “pseudoresistance” was related to the use of a single enteric-coated aspirin instead of immediate-release aspirin in people who had not been taking aspirin up to then. This complements an earlier study, which found that enteric-coated aspirin had an appropriate effect when given for 7 days.51 Therefore, for patients who have not been taking aspirin, the first dose should always be immediate-release, not enteric coated.

SHOULD OUR PATIENT RECEIVE ASPIRIN?

The patient we described at the beginning of this article has several risk factors—hypertension, dyslipidemia, left ventricular hypertrophy, and smoking—but no known cardiovascular disease as yet. Her risk of an adverse cardiovascular event appears moderate. However, her 10-year risk of stroke by the Framingham risk calculation is 10%, which would qualify her for aspirin for primary prevention. Of particular note is that the significance of left ventricular hypertrophy as a risk factor for stroke in women is higher than in men and in our case accounts for half of this patient’s risk.

We should explain to the patient that the anticipated benefits of aspirin for stroke prevention outweigh bleeding risks, and thus aspirin therapy would be recommended. However, with her elevated LDL-cholesterol, she may benefit from a statin, which could lessen the relative risk reduction from additional aspirin use.

A 57-year-old woman with no history of cardiovascular disease comes to the clinic for her annual evaluation. She does not have diabetes mellitus, but she does have hypertension and chronic osteoarthritis, currently treated with acetaminophen. Additionally, she admits to active tobacco use. Her systolic blood pressure is 130 mm Hg on therapy with hydrochlorothiazide. Her electrocardiogram demonstrates left ventricular hypertrophy. Her low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level is 140 mg/dL, and her high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol level is 50 mg/dL. Should this patient be started on aspirin therapy?

Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is an analgesic, antipyretic, and anti-inflammatory agent, but its more prominent use today is as an antithrombotic agent to treat or prevent cardiovascular events. Its antithrombotic properties are due to its effects on the enzyme cyclooxygenase. However, cyclooxygenase is also involved in regulation of the gastric mucosa, and so aspirin increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding.

Approximately 50 million people take aspirin on a daily basis to treat or prevent cardiovascular disease.1 Of these, at least half are taking more than 100 mg per day,2 reflecting the general belief that, for aspirin dosage, “more is better”—which is not true.

Additionally, recommendations about the use of aspirin were based on studies that included relatively few members of several important subgroups, such as people with diabetes without known cardiovascular disease, women, and the elderly, and thus may not reflect appropriate indications and dosages for these groups.

Here, we examine the literature, outline an individualized approach to aspirin therapy, and highlight areas for future study.

HISTORY OF ASPIRIN USE IN CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE

- 1700s—Willow bark is used as an analgesic.

- 1897—Synthetic aspirin is developed as an antipyretic and anti-inflammatory agent.

- 1974—First landmark trial of aspirin for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction.3

- 1982—Nobel Prize awarded for discovery of aspirin mechanism.

- 1985—US Food and Drug Administration approves aspirin for the treatment and secondary prevention of acute myocardial infarction.

- 1998—The Second International Study of Infarct Survival (ISIS-2) finds that giving aspirin to patients with myocardial infarction within 24 hours of presentation leads to a significant reduction in vascular deaths.4

Ongoing uncertainties

Aspirin now carries a class I indication for all patients with suspected myocardial infarction. Since there are an estimated 600,000 new coronary events and 325,000 recurrent ischemic events per year in the United States,5 the need for aspirin will continue to remain great. It is also approved to prevent and treat stroke and in patients with unstable angina.

However, questions continue to emerge about aspirin’s dosing and appropriate use in specific populations. The initial prevention trials used a wide range of doses and, as mentioned, included few women, few people with diabetes, and few elderly people. The uncertainties are especially pertinent for patients without known vascular disease, in whom the absolute risk reduction is much less, making the assessment of bleeding risk particularly important. Furthermore, the absolute risk-to-benefit assessment may be different in certain populations.

Guidelines on the use of aspirin to prevent cardiovascular disease (Table 1)6–10 have evolved to take into account these possible disparities, and studies are taking place to further investigate aspirin use in these groups.

ASPIRIN AND GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Aspirin’s association with bleeding, particularly gastrointestinal bleeding, was recognized early as a use-limiting side effect. With or without aspirin, gastrointestinal bleeding is a common cause of morbidity and death, with an incidence of approximately 100 per 100,000 bleeding episodes in adults per year for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and 20 to 30 per 100,000 per year for lower gastrointestinal bleeding.11,12

The standard dosage (ie, 325 mg/day) is associated with a significantly higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (including fatal bleeds) than is 75 mg.13 However, even with lower doses, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding is estimated to be twice as high as with no aspirin.14

And here is the irony: studies have shown that higher doses of aspirin offer no advantage in preventing thrombotic events compared with lower doses.15 For example, the Clopidogrel Optimal Loading Dose Usage to Reduce Recurrent Events/Organization to Assess Strategies for Ischemic Stroke Syndromes study reported a higher rate of gastrointestinal bleeding with standard-dose aspirin therapy than with low-dose aspirin, with no additional cardiovascular benefit with the higher dose.16

Furthermore, several other risk factors increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with aspirin use (Table 2). These risk factors are common in the general population but were not necessarily represented in participants in clinical trials. Thus, estimates of risk based on trial data most likely underestimate actual risk in the general population, and therefore, the individual patient’s risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, based on these and other factors, needs to be taken into consideration.

ASPIRIN IN PATIENTS WITH CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Randomized clinical trials have validated the benefits of aspirin in secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients who have had a myocardial infarction. Patients with coronary disease who withdraw from aspirin therapy or otherwise do not adhere to it have a risk of cardiovascular events three times higher than those who stay with it.17

Despite the strong data, however, several issues and questions remain about the use of aspirin for secondary prevention.

Bleeding risk must be considered, since gastrointestinal bleeding is associated with a higher risk of death and myocardial infarction in patients with cardiovascular disease.18 Many patients with coronary disease are on more than one antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy for concomitant conditions such as atrial fibrillation or because they underwent a percutaneous intervention, which further increases the risk of bleeding.

This bleeding risk is reflected in changes in the most recent recommendations for aspirin dosing after percutaneous coronary intervention. Earlier guidelines advocated use of either 162 or 325 mg after the procedure. However, the most recent update (in 2011) now supports 81 mg for maintenance dosing after intervention.7

Patients with coronary disease but without prior myocardial infarction or intervention. Current guidelines recommend 75 to 162 mg of aspirin in all patients with coronary artery disease.6 However, this group is diverse and includes patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, patients with chronic stable angina, and patients with asymptomatic coronary artery disease found on imaging studies. The magnitude of benefit is not clear for those who have no symptoms or who have stable angina.

Most of the evidence supporting aspirin use in chronic angina came from a single trial in Sweden, in which 2,000 patients with chronic stable angina were given either 75 mg daily or placebo. Those who received aspirin had a 34% lower rate of myocardial infarction and sudden death.19

A substudy of the Physicians’ Health Study, with fewer patients, also noted a significant reduction in the rate of first myocardial infarction. The dose of aspirin in this study was 325 mg every other day.20

In the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study, 70% of women with stable cardiovascular disease taking aspirin were taking 325 mg daily.21 This study demonstrated a significant reduction in the cardiovascular mortality rate, which supports current guidelines, and found no difference in outcomes with doses of 81 mg compared with 325 mg.21 This again corroborates that low-dose aspirin is preferential to standard-dose aspirin in women with cardiovascular disease.

These findings have not been validated in larger prospective trials. Thus, current guidelines for aspirin use may reflect extrapolation of aspirin benefit from higher-risk patients to lower-risk patients.

Nevertheless, although the debate continues, it has generally been accepted that in patients who are at high risk of vascular disease or who have had a myocardial infarction, the benefits of aspirin—a 20% relative reduction in vascular events22—clearly outweigh the risks.

ASPIRIN FOR PRIMARY PREVENTION

Assessing risk vs benefit is more complex when considering populations without known cardiovascular disease.

Only a few studies have specifically evaluated the use of aspirin for primary prevention (Table 3).23–31 The initial trials were in male physicians in the United Kingdom and the United States in the late 1980s and had somewhat conflicting results. A British study did not find a significant reduction in myocardial infarction,23 but the US Physician’s Health Study study did: the relative risk was 0.56 (95% confidence interval 0.45–0.70, P < .00001).24 The US study had more than four times the number of participants, used different dosing (325 mg every other day compared with 500 or 300 mg daily in the British study), and had a higher rate of compliance.

Several studies over the next decade demonstrated variable but significant reductions in cardiovascular events as well.25–27

A meta-analysis of primary prevention trials of aspirin was published in 2009.22 Although the relative risk reduction was similar in primary and secondary prevention, the absolute risk reduction in primary prevention was not nearly as great as in secondary prevention.

These findings are somewhat difficult to interpret, as the component trials included a wide spectrum of patients, ranging from healthy people with no symptoms and no known risk factors to those with limited risk factors. The trials were also performed over several decades during which primary prevention strategies were evolving. Additionally, most of the participants were middle-aged, nondiabetic men, so the results may not necessarily apply to people with diabetes, to women, or to the elderly. Thus, the pooled data in favor of aspirin for primary prevention may not be as broadly applicable to the general population as was once thought.

Aspirin for primary prevention in women

Guidelines for aspirin use in primary prevention were initially thought to be equally applicable to both sexes. However, concerns about the relatively low number of women participating in the studies and the possible mechanistic differences in aspirin efficacy in men vs women prompted further study.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that aspirin was associated with a 12% relative reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events in women and 14% in men. On the other hand, for stroke, the relative risk reduction was 17% in women, while men had no benefit.32

Most of the women in this meta-analysis were participants in the Women’s Health Study, and they were at low baseline risk.28 Although only about 10% of patients in this study were over age 65, this older group accounted for most of the benefit: these older women had a 26% risk reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events and 30% reduction in stroke.

Thus, for women, aspirin seems to become effective for primary prevention at an older age than in men, and the guidelines have been changed accordingly (Figure 1).

More women should be taking aspirin than actually are. For example, Rivera et al33 found that only 41% of eligible women were receiving aspirin for primary prevention and 48% of eligible women were receiving it for secondary prevention.

People with diabetes

People with diabetes without overt cardiovascular disease are at higher risk of cardiovascular events than age- and sex-matched controls.34 On the other hand, people with diabetes may be more prone to aspirin resistance and may not derive as much cardiovascular benefit from aspirin.

Early primary prevention studies included few people with diabetes. Subsequent meta-analyses of trials that used a wide range of aspirin doses found a relative risk reduction of 9%, which was not statistically significant.9,35,36

But there is some evidence that people with diabetes, with37 and without22 coronary disease, may be at higher inherent risk of bleeding than people without diabetes. Although aspirin may not necessarily increase the risk of bleeding in diabetic patients, recent data suggest no benefit in terms of a reduction in vascular events.38

The balance of risk vs benefit for aspirin in this special population is not clear, although some argue that these patients should be treated somewhere on the spectrum of risk between primary and secondary prevention.

The US Preventive Services Task Force did not differentiate between people with or without diabetes in its 2009 guidelines for aspirin for primary prevention.8 However, the debate is reflected in a change in 2010 American College of Cardiology/American Diabetes Association guidelines regarding aspirin use in people with diabetes without known cardiovascular disease.39 As opposed to earlier recommendations from these organizations in favor of aspirin for all people with diabetes regardless of 10-year risk, current recommendations advise low-dose aspirin (81–162 mg) for diabetic patients without known vascular disease who have a greater than 10% risk of a cardiovascular event and are not at increased risk of bleeding.

These changes were based on the findings of two trials: the Prevention and Progression of Arterial Disease and Diabetes Trial (POPADAD) and the Japanese Primary Prevention of Atherosclerosis With Aspirin for Diabetes (JPAD) study. These did not show a statistically significant benefit in prevention of cardiovascular events with aspirin.29,30

After the new guidelines came out, a meta-analysis further bolstered its recommendations. 40 In seven randomized clinical trials in 11,000 patients, the relative risk reduction was 9% with aspirin, which did not reach statistical significance.

Statins may dilute the benefit of aspirin

The use of statins has been increasing, and this trend may have played a role in the marginal benefit of aspirin therapy in these recent studies. In the Japanese trial, approximately 25% of the patients were known to be using a statin; the percentage of statin use was not reported specifically in POPADAD, but both of these studies were published in 2008, when the proportion of diabetic patients taking a statin would be expected to be higher than in earlier primary prevention trials, which were performed primarily in the 1990s. Thus, the beneficial effects of statins may have somewhat diluted the risk reduction attributable to aspirin.

Trials under way in patients with diabetes

The evolving and somewhat conflicting guidelines highlight the need for further study in patients with diabetes. To address this area, two trials are in progress: the Aspirin and Simvastatin Combination for Cardiovascular Events Prevention Trial in Diabetes (ACCEPT-D) and A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes (ASCEND).41,42

ACCEPT-D is testing low-dose aspirin (100 mg daily) in diabetic patients who are also on simvastatin. This study also includes prespecified subgroups stratified by sex, age, and baseline lipid levels.

The ASCEND trial will use the same aspirin dose as ACCEPT-D, with a target enrollment of 10,000 patients with diabetes without known vascular disease.

More frequent dosing for people with diabetes?

Although not supported by current guidelines, recent work has suggested that people with diabetes may need more-frequent dosing of aspirin.43 This topic warrants further investigation.

Aspirin as primary prevention in elderly patients

The incidence of cardiovascular events increases with age37—but so does the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding.44 Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is especially worrisome in the elderly, in whom the estimated case-fatality rate is high.12 Assessment of risk and benefit is particularly important in patients over age 65 without known coronary disease.

Uncertainty about aspirin use in this population is reflected in the most recent US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines, which do not advocate either for or against regular aspirin use for primary prevention in those over the age of 80.

Data on this topic from clinical trials are limited. The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration (2009) found that although age is associated with a risk of major coronary events similar to that of other traditional risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and tobacco use, older age is also associated with the highest risk of major extracranial bleeding.22

Because of the lack of data in this population, several studies are currently under way. The Aspirin in Reducing Events in the Elderly (ASPREE) trial is studying 100 mg daily in nondiabetic patients without known cardiovascular disease who are age 70 and older.45 An additional trial will study patients age 60 to 85 with concurrent diagnoses of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes and will test the same aspirin dose as in ASPREE.46 These trials should provide further insight into the safety and efficacy of aspirin for primary prevention in the elderly.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Aspirin remains a cornerstone of therapy in patients with cardiovascular disease and in secondary prevention of adverse cardiovascular events, but its role in primary prevention remains under scrutiny. Recommendations have evolved to reflect emerging data in special populations, and an algorithm based on Framingham risk assessment in men for myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke assessment in women for assessing appropriateness of aspirin therapy based on currently available guidelines is presented in Figure 1.6,8,47–49 Targeted studies have advanced our understanding of aspirin use in women, and future studies in people with diabetes and in the elderly should provide further insight into the role of aspirin for primary prevention in these specific groups as well.

Additionally, the range of doses used in clinical studies has propagated the general misperception that higher doses of aspirin are more efficacious. Future studies should continue to use lower doses of aspirin to minimize bleeding risk with an added focus on re-examining its net benefit in the modern era of increasing statin use, which may reduce the absolute risk reduction attributable to aspirin.

One particular area of debate is whether enteric coating can result in functional aspirin resistance. Grosser et al50 found that sustained aspirin resistance was rare, and “pseudoresistance” was related to the use of a single enteric-coated aspirin instead of immediate-release aspirin in people who had not been taking aspirin up to then. This complements an earlier study, which found that enteric-coated aspirin had an appropriate effect when given for 7 days.51 Therefore, for patients who have not been taking aspirin, the first dose should always be immediate-release, not enteric coated.

SHOULD OUR PATIENT RECEIVE ASPIRIN?

The patient we described at the beginning of this article has several risk factors—hypertension, dyslipidemia, left ventricular hypertrophy, and smoking—but no known cardiovascular disease as yet. Her risk of an adverse cardiovascular event appears moderate. However, her 10-year risk of stroke by the Framingham risk calculation is 10%, which would qualify her for aspirin for primary prevention. Of particular note is that the significance of left ventricular hypertrophy as a risk factor for stroke in women is higher than in men and in our case accounts for half of this patient’s risk.

We should explain to the patient that the anticipated benefits of aspirin for stroke prevention outweigh bleeding risks, and thus aspirin therapy would be recommended. However, with her elevated LDL-cholesterol, she may benefit from a statin, which could lessen the relative risk reduction from additional aspirin use.

- Chan FK, Graham DY. Review article: prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug gastrointestinal complications—review and recommendations based on risk assessment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19:1051–1061.

- Peters RJ, Mehta SR, Fox KA, et al; Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) Trial Investigators. Effects of aspirin dose when used alone or in combination with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: observations from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) study. Circulation 2003; 108:1682–1687.

- Elwood PC, Cochrane AL, Burr ML, et al. A randomized controlled trial of acetyl salicylic acid in the secondary prevention of mortality from myocardial infarction. Br Med J 1974; 1:436–440.

- Baigent C, Collins R, Appleby P, Parish S, Sleight P, Peto R. ISIS-2: 10 year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. The ISIS-2 (Second International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. BMJ 1998; 316:1337–1343.

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123:e18–e209.

- Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation endorsed by the World Heart Federation and the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:2432–2446.

- Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:e44–e122.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150:396–404.

- Pignone M, Alberts MJ, Colwell JA, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association, a scientific statement of the American Heart Association, and an expert consensus document of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2010; 121:2694–2701.

- Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011; 123:1243–1262.

- Strate LL. Lower GI bleeding: epidemiology and diagnosis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2005; 34:643–664.

- Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ 1995; 311:222–226.

- Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, Steinhubl SR. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2007; 297:2018–2024.

- Weil J, Colin-Jones D, Langman M, et al. Prophylactic aspirin and risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. BMJ 1995; 310:827–830.

- Reilly IA, FitzGerald GA. Inhibition of thromboxane formation in vivo and ex vivo: implications for therapy with platelet inhibitory drugs. Blood 1987; 69:180–186.

- CURRENT-OASIS 7 Investigators; Mehta SR, Bassand JP, Chrolavicius S, et al. Dose comparisons of clopidogrel and aspirin in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:930–942.