User login

Pneumomediastinum and Pneumopericardium

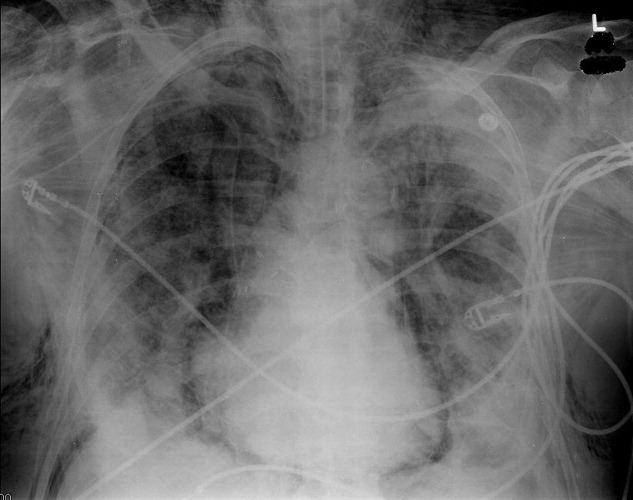

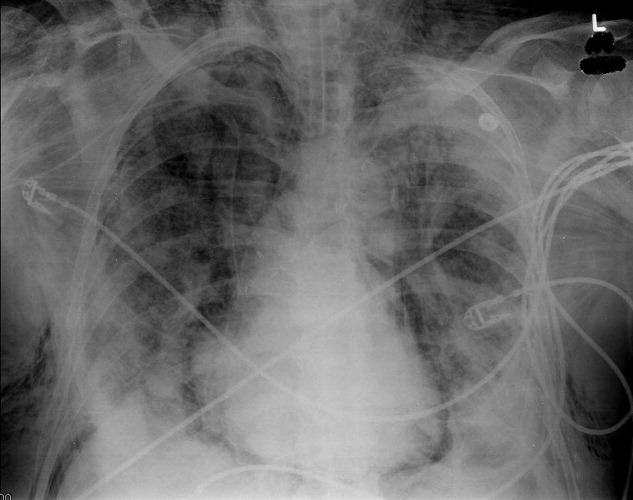

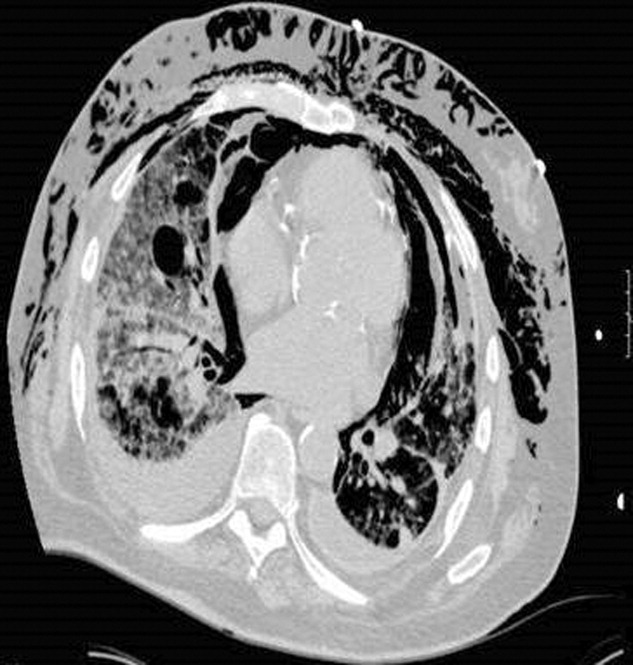

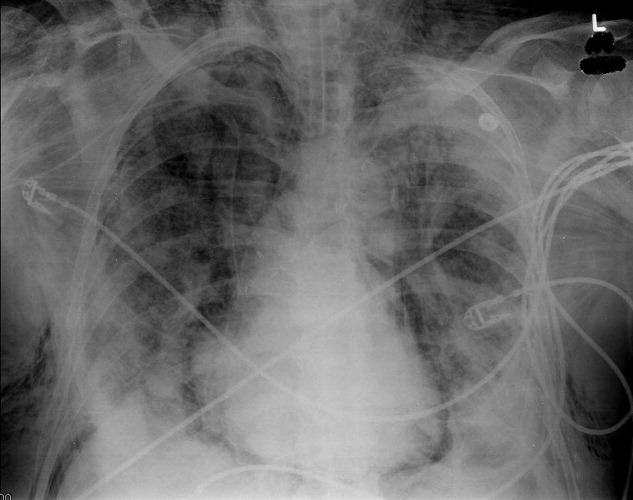

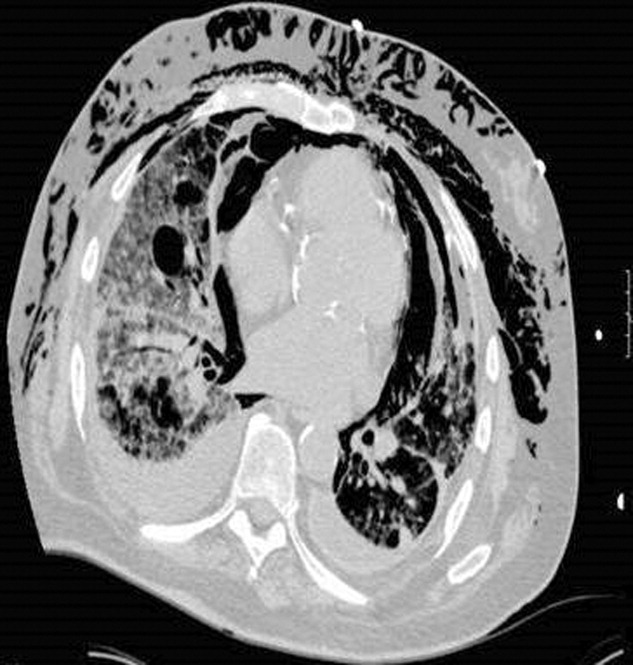

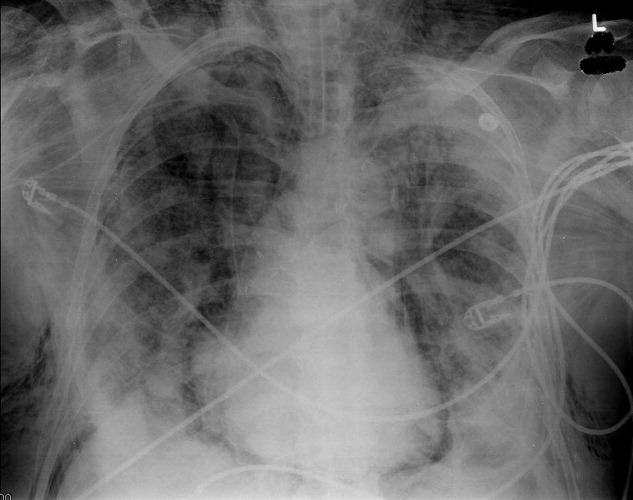

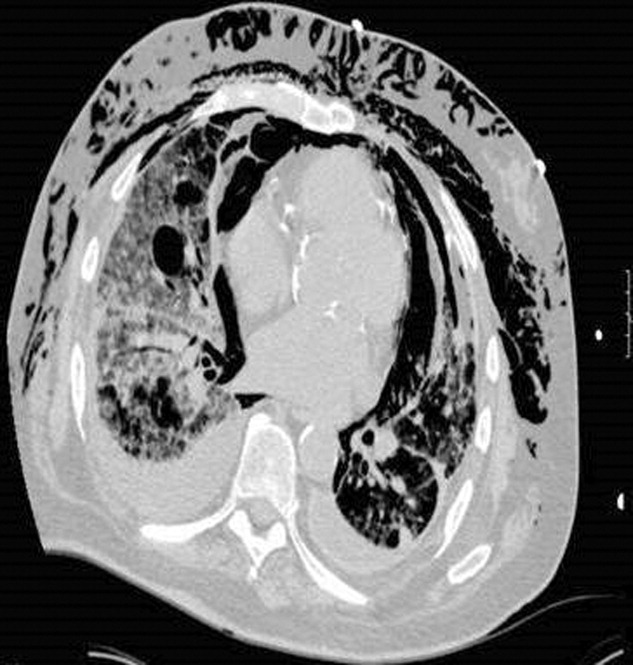

A 73‐year‐old male presented with acute congestive heart failure and non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction. His initial chest x‐ray and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated pulmonary vascular congestion and alveolar infiltrates, and he promptly underwent cardiac catheterization with placement of a coronary stent. Subsequently, his respiratory status deteriorated, and repeat films and chest CT demonstrated extensive pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium (Figures 13). The patient was intubated, and bronchoscopy and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy were performed, but demonstrated no evidence of perforation that could cause such an air leak. There was no evidence of tamponade, clinically or on echocardiogram. His condition worsened abruptly, and he expired following a cardiac arrest. Postmortem, the team considered that the extensive air leak could have been caused by catheterization, stent placement, central line placement, or mediastinitis or pericarditis causing microscopic fistulae. The patient's tracheal aspirate and biopsy grew Candida albicans but no evidence of invasive candidiasis was found on autopsy. No definitive etiology was found.

In contrast to pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium is a rare condition and its pathophysiology is not well understood. Most cases have been reported in newborns receiving mechanical ventilation. In adults, the condition occurs due to chest trauma, or can be iatrogenic secondary to laparoscopy, bronchoscopy, or endotracheal intubation. There have been case reports of pneumopericardium after cardiac catheterization and central line placement.1, 2 Other causes include lung transplant, esophageal perforation, severe asthma, positive pressure ventilation, and pericarditis (eg, histoplasmosis and tuberculosis).3, 4 Clinical findings include distant heart sounds, shifting precordial tympany, and a succussion splash with metallic tinkling (known as mill wheel murmur) in hydropneumopericardium.5 Chest CT can distinguish pneumopericardium from pneumomediastinum: with the former, the air changes position when the patient adopts a supine position.6 Cardiac tamponade can occur in up to 37% of cases, and pericardiocentesis or pericardial tube drainage in these cases can be lifesaving.7

- ,,,,.[Cardiac tamponade and central venous catheterization].Ann Fr Anesth Reanim.1992;11:201–204. [French]

- ,,,.Pneumopericardium as a complication of balloon atrial septostomy.Pediatr Cardiol.1987;8:135–137.

- ,,,,.Continuous left hemidiaphragm sign revisited: a case of spontaneous pneumopericardium and literature review.Heart.2002;88:e5.

- ,.Tension pneumopericardium: a case report and a review of the literature.Am Surg.2006;72:330–331.

- Symptoms and signs of syndromes associated with mill wheel murmurs.NC Med J.1988;49:569–572.

- ,.Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs.AJR Am J Roentgenol.1996;166:1041–1048.

- ,,,,.Cardiac tamponade without pericardial effusion after blunt chest trauma.Am Heart J.1996;131:198–200.

A 73‐year‐old male presented with acute congestive heart failure and non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction. His initial chest x‐ray and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated pulmonary vascular congestion and alveolar infiltrates, and he promptly underwent cardiac catheterization with placement of a coronary stent. Subsequently, his respiratory status deteriorated, and repeat films and chest CT demonstrated extensive pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium (Figures 13). The patient was intubated, and bronchoscopy and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy were performed, but demonstrated no evidence of perforation that could cause such an air leak. There was no evidence of tamponade, clinically or on echocardiogram. His condition worsened abruptly, and he expired following a cardiac arrest. Postmortem, the team considered that the extensive air leak could have been caused by catheterization, stent placement, central line placement, or mediastinitis or pericarditis causing microscopic fistulae. The patient's tracheal aspirate and biopsy grew Candida albicans but no evidence of invasive candidiasis was found on autopsy. No definitive etiology was found.

In contrast to pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium is a rare condition and its pathophysiology is not well understood. Most cases have been reported in newborns receiving mechanical ventilation. In adults, the condition occurs due to chest trauma, or can be iatrogenic secondary to laparoscopy, bronchoscopy, or endotracheal intubation. There have been case reports of pneumopericardium after cardiac catheterization and central line placement.1, 2 Other causes include lung transplant, esophageal perforation, severe asthma, positive pressure ventilation, and pericarditis (eg, histoplasmosis and tuberculosis).3, 4 Clinical findings include distant heart sounds, shifting precordial tympany, and a succussion splash with metallic tinkling (known as mill wheel murmur) in hydropneumopericardium.5 Chest CT can distinguish pneumopericardium from pneumomediastinum: with the former, the air changes position when the patient adopts a supine position.6 Cardiac tamponade can occur in up to 37% of cases, and pericardiocentesis or pericardial tube drainage in these cases can be lifesaving.7

A 73‐year‐old male presented with acute congestive heart failure and non‐ST elevation myocardial infarction. His initial chest x‐ray and computed tomography (CT) demonstrated pulmonary vascular congestion and alveolar infiltrates, and he promptly underwent cardiac catheterization with placement of a coronary stent. Subsequently, his respiratory status deteriorated, and repeat films and chest CT demonstrated extensive pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium (Figures 13). The patient was intubated, and bronchoscopy and upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy were performed, but demonstrated no evidence of perforation that could cause such an air leak. There was no evidence of tamponade, clinically or on echocardiogram. His condition worsened abruptly, and he expired following a cardiac arrest. Postmortem, the team considered that the extensive air leak could have been caused by catheterization, stent placement, central line placement, or mediastinitis or pericarditis causing microscopic fistulae. The patient's tracheal aspirate and biopsy grew Candida albicans but no evidence of invasive candidiasis was found on autopsy. No definitive etiology was found.

In contrast to pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium is a rare condition and its pathophysiology is not well understood. Most cases have been reported in newborns receiving mechanical ventilation. In adults, the condition occurs due to chest trauma, or can be iatrogenic secondary to laparoscopy, bronchoscopy, or endotracheal intubation. There have been case reports of pneumopericardium after cardiac catheterization and central line placement.1, 2 Other causes include lung transplant, esophageal perforation, severe asthma, positive pressure ventilation, and pericarditis (eg, histoplasmosis and tuberculosis).3, 4 Clinical findings include distant heart sounds, shifting precordial tympany, and a succussion splash with metallic tinkling (known as mill wheel murmur) in hydropneumopericardium.5 Chest CT can distinguish pneumopericardium from pneumomediastinum: with the former, the air changes position when the patient adopts a supine position.6 Cardiac tamponade can occur in up to 37% of cases, and pericardiocentesis or pericardial tube drainage in these cases can be lifesaving.7

- ,,,,.[Cardiac tamponade and central venous catheterization].Ann Fr Anesth Reanim.1992;11:201–204. [French]

- ,,,.Pneumopericardium as a complication of balloon atrial septostomy.Pediatr Cardiol.1987;8:135–137.

- ,,,,.Continuous left hemidiaphragm sign revisited: a case of spontaneous pneumopericardium and literature review.Heart.2002;88:e5.

- ,.Tension pneumopericardium: a case report and a review of the literature.Am Surg.2006;72:330–331.

- Symptoms and signs of syndromes associated with mill wheel murmurs.NC Med J.1988;49:569–572.

- ,.Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs.AJR Am J Roentgenol.1996;166:1041–1048.

- ,,,,.Cardiac tamponade without pericardial effusion after blunt chest trauma.Am Heart J.1996;131:198–200.

- ,,,,.[Cardiac tamponade and central venous catheterization].Ann Fr Anesth Reanim.1992;11:201–204. [French]

- ,,,.Pneumopericardium as a complication of balloon atrial septostomy.Pediatr Cardiol.1987;8:135–137.

- ,,,,.Continuous left hemidiaphragm sign revisited: a case of spontaneous pneumopericardium and literature review.Heart.2002;88:e5.

- ,.Tension pneumopericardium: a case report and a review of the literature.Am Surg.2006;72:330–331.

- Symptoms and signs of syndromes associated with mill wheel murmurs.NC Med J.1988;49:569–572.

- ,.Pneumomediastinum: old signs and new signs.AJR Am J Roentgenol.1996;166:1041–1048.

- ,,,,.Cardiac tamponade without pericardial effusion after blunt chest trauma.Am Heart J.1996;131:198–200.

In reply: Shingles vaccine

In Reply: We thank Dr. Shaheen for his interesting comment. He has made an important point. The data on the use of shingles vaccine in patients with a history of zoster are insufficient. The main study of shingles vaccine1 excluded patients who had already had shingles.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says: “Persons with a reported history of zoster can [emphasis added] be vaccinated. Repeated zoster has been confirmed in immunocompetent persons soon after a previous episode. Although the precise risk for and severity of zoster as a function of time following an earlier episode are unknown, some studies suggest it may be comparable to the risk in persons without a history of zoster. Furthermore, no laboratory evaluations exist to test for the previous occurrence of zoster, and any reported diagnosis or history might be erroneous.”2

Until more data are available for this patient population, current evidence and availability of shingles vaccine should be discussed with patients who report a history of shingles.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic nerualgia in older adults. N Engl Med 2005; 352:2271–2284.

- Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of herpes zoster. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recom Rep 2008 Jun 6; 57(RR-5):1–30.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Shaheen for his interesting comment. He has made an important point. The data on the use of shingles vaccine in patients with a history of zoster are insufficient. The main study of shingles vaccine1 excluded patients who had already had shingles.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says: “Persons with a reported history of zoster can [emphasis added] be vaccinated. Repeated zoster has been confirmed in immunocompetent persons soon after a previous episode. Although the precise risk for and severity of zoster as a function of time following an earlier episode are unknown, some studies suggest it may be comparable to the risk in persons without a history of zoster. Furthermore, no laboratory evaluations exist to test for the previous occurrence of zoster, and any reported diagnosis or history might be erroneous.”2

Until more data are available for this patient population, current evidence and availability of shingles vaccine should be discussed with patients who report a history of shingles.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Shaheen for his interesting comment. He has made an important point. The data on the use of shingles vaccine in patients with a history of zoster are insufficient. The main study of shingles vaccine1 excluded patients who had already had shingles.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says: “Persons with a reported history of zoster can [emphasis added] be vaccinated. Repeated zoster has been confirmed in immunocompetent persons soon after a previous episode. Although the precise risk for and severity of zoster as a function of time following an earlier episode are unknown, some studies suggest it may be comparable to the risk in persons without a history of zoster. Furthermore, no laboratory evaluations exist to test for the previous occurrence of zoster, and any reported diagnosis or history might be erroneous.”2

Until more data are available for this patient population, current evidence and availability of shingles vaccine should be discussed with patients who report a history of shingles.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic nerualgia in older adults. N Engl Med 2005; 352:2271–2284.

- Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of herpes zoster. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recom Rep 2008 Jun 6; 57(RR-5):1–30.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic nerualgia in older adults. N Engl Med 2005; 352:2271–2284.

- Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of herpes zoster. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recom Rep 2008 Jun 6; 57(RR-5):1–30.

In reply: Shingles vaccine

In Reply: We appreciate the interest and comments of Dr Hirsch. Due to space limitations of the Journal’s 1-Minute Consult format, we were unable to elaborate on the cost and reimbursement. Since shingles vaccine is not covered by Medicare part B, reimbursement and administration of this vaccine remains challenging, and resources like eDispense are helpful tools for the physician to simplify the process of reimbursement—with no charge to the physician.

In Reply: We appreciate the interest and comments of Dr Hirsch. Due to space limitations of the Journal’s 1-Minute Consult format, we were unable to elaborate on the cost and reimbursement. Since shingles vaccine is not covered by Medicare part B, reimbursement and administration of this vaccine remains challenging, and resources like eDispense are helpful tools for the physician to simplify the process of reimbursement—with no charge to the physician.

In Reply: We appreciate the interest and comments of Dr Hirsch. Due to space limitations of the Journal’s 1-Minute Consult format, we were unable to elaborate on the cost and reimbursement. Since shingles vaccine is not covered by Medicare part B, reimbursement and administration of this vaccine remains challenging, and resources like eDispense are helpful tools for the physician to simplify the process of reimbursement—with no charge to the physician.

Who should receive the shingles vaccine?

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routinely giving a single dose of live zoster vaccine to immunocompetent patients age 60 and older at their first clinical encounter. The vaccine effectively prevents shingles and postherpetic neuralgia and their associated burden of illness. Although not all insurance companies pay for it yet, it should be offered to all patients for whom it is indicated to increase their health-related quality of life.

IMMUNITY WANES WITH AGE

Shingles, also known as zoster or herpes zoster, is caused by retrograde transport of the varicella zoster virus (VZV) from the ganglia to the skin in a host who had a primary varicella infection (chickenpox) in the past.1 Although shingles is not one of the diseases that must be reported to public health authorities, more than 1 million cases are estimated to occur each year in the United States. From 10% to 30% of people develop shingles during their lifetime.2,3

The elderly are at particular risk of shingles, because immunity to VZV wanes as a part of normal aging. As many as 50% of people who live to age 85 will have shingles at some point in their life.

Moreover, about 20% of patients with shingles develop postherpetic neuralgia,3,4 the pain and discomfort of which can be disabling and can diminish quality of life.5

Antiviral therapy reduces the severity and duration of an episode of shingles but does not prevent postherpetic neuralgia.2,6 Steroids provide additional relief of acute zoster pain, but they do not clearly prevent postherpetic neuralgia either and should be used only in combination with antiviral drugs. Preventing zoster and postherpetic neuralgia by routine vaccination should be a goal in our efforts to promote healthy aging, especially with the increasing number of elderly in our country.7

THE VACCINE IS EFFECTIVE: THE SHINGLES PREVENTION STUDY

The Shingles Prevention Study was a prospective, double-blind trial in more than 38,000 adults, median age 69 years (range 59–99), who were followed for a mean of 3.13 years (range 1 day to 4.9 years) after receiving the zoster vaccine or placebo.8–10

The virus in the vaccine did not elicit shingles in any patient. After vaccination, if lesions did occur, they were from the patient’s native strain, not the vaccine strain.8

ZOSTAVAX

The US Food and Drug Administration approved the zoster vaccine in May 2006 for prevention of herpes zoster in people age 60 and older. Zostavax, licensed by Merck, is the only vaccine available for this purpose.11,12 Zoster vaccine is not indicated for treating episodes of shingles or postherpetic neuralgia or for preventing primary varicella infection (chickenpox).

Zostavax does not contain thimerosal, a mercury-based preservative used in other vaccines. Therefore, it must be kept frozen at an average temperature of –15°C (5°F) and should not be used if its temperature rises above –5°C (23°F).13,14 Just before it is given, the vaccine is reconstituted with the supplied diluents and then injected subcutaneously in the deltoid region.12

No booster dose is recommended at present. Also, many cases of herpes zoster occur in people under age 60, for whom there is no recommendation.11,15 Although the vaccine would probably be safe and effective in this younger group, data are insufficient to recommend vaccinating them.16

ZOSTER VACCINE (ZOSTAVAX) IS NOT CHICKENPOX VACCINE (VARIVAX)

Both Zostavax and the chickenpox vaccine (Varivax) are live, attenuated vaccines from the same Oka/Merck strain of the virus, but Zostavax is about 14 times more potent than Varivax (Zostavax contains 8,700–60,000 plaque-forming units of virus, whereas Varivax contains 1,350), and they should not be used interchangeably.14

GIVING ZOSTER VACCINE WITH OTHER VACCINES IN THE ELDERLY

Zostavax can be given either simultaneously with or at any time before or after any inactivated vaccine (such as tetanus toxoid, influenza, pneumococcus). However, each vaccine must be given in a separate syringe at a different anatomic site.17

VACCINATE EVEN IF THE PATIENT DOESN’T RECALL HAVING CHICKENPOX

Even in people who do not recall ever having chickenpox, the rate of VZV seropositivity is very high (> 95% in those over age 60 in the United States).18 The ACIP recommends vaccination whether or not the patient reports having had chickenpox. Serologic testing to determine varicella immunity is not needed before vaccination, nor was it required for entry in the Shingles Prevention Study.

Furthermore, in VZV-seronegative adults, giving the zoster vaccine is thought to provide at least partial protection against varicella, and no data indicate any excessive adverse effects in this population.

VACCINATE EVEN IF THE PATIENT HAS HAD SHINGLES

The ACIP says that people with a history of zoster can be vaccinated. Recurrent zoster has been confirmed in immunocompetent patients soon after a previous episode. There is no test to confirm prior zoster episodes, and if the patient is immunocompetent, no different safety concerns are anticipated with vaccination in this group.16

ADVERSE EFFECTS ARE MILD

No significant safety concerns have been noted with zoster vaccine. Mild local reactions (erythema, swelling, pain, pruritus) and headache are the most common adverse events. There have been no differences in the numbers and types of serious adverse events during the 42 days after receipt of vaccine or placebo.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Contraindications to zoster vaccine are:

- A history of anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions to gelatin, neomycin, or other components of the vaccine

- Acquired or primary immune deficiency states, including AIDS

- Cancer chemotherapy or radiotherapy

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

- Organ transplantation

- Active untreated tuberculosis

- Pregnancy or breast-feeding.

However, patients with leukemia in remission who have not received chemotherapy (eg, alkylating drugs or antimetabolites) or radiation for at least 3 months can receive zoster vaccine.

Although zoster vaccine is contraindicated in conditions of cellular immune deficiency, patients with humoral immunodeficiency (eg, hypogammaglobulinemia or dysgammaglobulinemia) can receive it.

Diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure, coronary artery disease, chronic lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and other medical conditions are not considered contraindications to the vaccine.

The ACIP does not recommend any upper age limit for the vaccine, and preventing zoster is particularly important in the oldest elderly because they have the highest incidence of zoster and postherpetic neuralgia.16

Do not vaccinate during immunosuppressive treatment

If immunosuppressive treatment is planned (eg, with corticosteroids or anti-tumor necrosis factor agents), the vaccine should be given at least 14 days (preferably 1 month) before immunosuppression begins.

The safety and efficacy of zoster vaccine is unknown in patients receiving recombinant human immune mediators and immune modulators, especially anti-tumor necrosis factor agents such as adalimumab (Humira), infliximab (Remicade), or etanercept (Enbrel). These patients should be vaccinated 1 month before starting the treatment or 1 month after stopping it.16

Patients on corticosteroids in doses equivalent to prednisone 20 mg/day or more for 2 or more weeks should not be vaccinated against zoster unless the steroids have been stopped for at least 1 month.11

Low doses of methotrexate (< 0.4 mg/kg/week), azathioprine (Azasan) (< 3.0 mg/kg/day), or 6-mercaptopurine (Purinethol, 6-MP) (< 1.5 mg/kg/day) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, polymyositis, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and other conditions are not contraindications to zoster vaccination.

Medications against herpes, such as acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), or valacyclovir (Valtrex) should be discontinued at least 24 hours before zoster vaccination and should not be started until 14 days afterward.

COSTLY AND EFFECTIVE? OR COST-EFFECTIVE?

The average cost associated with an acute episode of zoster ranges from $112 to $287 if treated on an outpatient basis and $3,221 to $7,206 if the patient is hospitalized (costs in 2006).19

Although pharmacists are licensed to administer influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, several states do not specifically allow them to administer zoster vaccine. Moreover, one usually cannot provide the vaccine out of the office stock and get reimbursed for it (except by some private insurance companies). Instead, the patient needs to take a prescription to a local pharmacy, where the vaccine is placed on ice and then brought back to the physician’s office for administration.

- Nagel MA, Gilden DH. The protean neurologic manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Cleve Clin J Med 2007; 74:489–504.

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:340–346.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, Sweeney EW, Dworkin RH. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:342–348.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965; 58:9–20.

- Lydick E, Epstein RS, Himmelberger D, White CJ. Herpes zoster and quality of life: a self-limited disease with severe impact. Neurology 1995; 45:S52–S53.

- Kost RG, Straus SE. Postherpetic neuralgia—pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:32–42.

- Johnson R, McElhaney J, Pedalino B, Levin M. Prevention of herpes zoster and its painful and debilitating complications. Int J Infect Dis 2007; 11( suppl 2):S43–S48.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2271–2284.

- Burke MS. Herpes zoster vaccine: clinical trial evidence and implications for medical practice. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2007; 107( suppl 1):S14–S18.

- Betts RF. Vaccination strategies for the prevention of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57( suppl):S143–S147.

- Kroger AT, Atkinson WL, Marcuse EK, Pickering LK. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–48.

- Merck. Zostavax zoster vaccine live suspension for subcutaneous injection. www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/z/zostavax_pi.pdf. Accessed 11/17/2008.

- Holodniy M. Prevention of shingles by varicella zoster virus vaccination. Expert Rev Vaccines 2006; 5:431–443.

- Herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2006; 48:73–74.

- Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1605–1609.

- Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2008; 57:1–30.

- Bader MS. Immunization for the elderly. Am J Med Sci 2007; 334:481–486.

- Kilgore PE, Kruszon-Moran D, Seward JF, et al. Varicella in Americans from NHANES III: implications for control through routine immunization. J Med Virol 2003; 70( suppl 1):S111–S118.

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, Baser O, Hawkins K. Healthcare costs of acute and chronic pain associated with a diagnosis of herpes zoster. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:1168–1175.

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, Hawkins K. Health care expenditure burden of persisting herpes zoster pain. Pain Med 2008; 9:348–353.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routinely giving a single dose of live zoster vaccine to immunocompetent patients age 60 and older at their first clinical encounter. The vaccine effectively prevents shingles and postherpetic neuralgia and their associated burden of illness. Although not all insurance companies pay for it yet, it should be offered to all patients for whom it is indicated to increase their health-related quality of life.

IMMUNITY WANES WITH AGE

Shingles, also known as zoster or herpes zoster, is caused by retrograde transport of the varicella zoster virus (VZV) from the ganglia to the skin in a host who had a primary varicella infection (chickenpox) in the past.1 Although shingles is not one of the diseases that must be reported to public health authorities, more than 1 million cases are estimated to occur each year in the United States. From 10% to 30% of people develop shingles during their lifetime.2,3

The elderly are at particular risk of shingles, because immunity to VZV wanes as a part of normal aging. As many as 50% of people who live to age 85 will have shingles at some point in their life.

Moreover, about 20% of patients with shingles develop postherpetic neuralgia,3,4 the pain and discomfort of which can be disabling and can diminish quality of life.5

Antiviral therapy reduces the severity and duration of an episode of shingles but does not prevent postherpetic neuralgia.2,6 Steroids provide additional relief of acute zoster pain, but they do not clearly prevent postherpetic neuralgia either and should be used only in combination with antiviral drugs. Preventing zoster and postherpetic neuralgia by routine vaccination should be a goal in our efforts to promote healthy aging, especially with the increasing number of elderly in our country.7

THE VACCINE IS EFFECTIVE: THE SHINGLES PREVENTION STUDY

The Shingles Prevention Study was a prospective, double-blind trial in more than 38,000 adults, median age 69 years (range 59–99), who were followed for a mean of 3.13 years (range 1 day to 4.9 years) after receiving the zoster vaccine or placebo.8–10

The virus in the vaccine did not elicit shingles in any patient. After vaccination, if lesions did occur, they were from the patient’s native strain, not the vaccine strain.8

ZOSTAVAX

The US Food and Drug Administration approved the zoster vaccine in May 2006 for prevention of herpes zoster in people age 60 and older. Zostavax, licensed by Merck, is the only vaccine available for this purpose.11,12 Zoster vaccine is not indicated for treating episodes of shingles or postherpetic neuralgia or for preventing primary varicella infection (chickenpox).

Zostavax does not contain thimerosal, a mercury-based preservative used in other vaccines. Therefore, it must be kept frozen at an average temperature of –15°C (5°F) and should not be used if its temperature rises above –5°C (23°F).13,14 Just before it is given, the vaccine is reconstituted with the supplied diluents and then injected subcutaneously in the deltoid region.12

No booster dose is recommended at present. Also, many cases of herpes zoster occur in people under age 60, for whom there is no recommendation.11,15 Although the vaccine would probably be safe and effective in this younger group, data are insufficient to recommend vaccinating them.16

ZOSTER VACCINE (ZOSTAVAX) IS NOT CHICKENPOX VACCINE (VARIVAX)

Both Zostavax and the chickenpox vaccine (Varivax) are live, attenuated vaccines from the same Oka/Merck strain of the virus, but Zostavax is about 14 times more potent than Varivax (Zostavax contains 8,700–60,000 plaque-forming units of virus, whereas Varivax contains 1,350), and they should not be used interchangeably.14

GIVING ZOSTER VACCINE WITH OTHER VACCINES IN THE ELDERLY

Zostavax can be given either simultaneously with or at any time before or after any inactivated vaccine (such as tetanus toxoid, influenza, pneumococcus). However, each vaccine must be given in a separate syringe at a different anatomic site.17

VACCINATE EVEN IF THE PATIENT DOESN’T RECALL HAVING CHICKENPOX

Even in people who do not recall ever having chickenpox, the rate of VZV seropositivity is very high (> 95% in those over age 60 in the United States).18 The ACIP recommends vaccination whether or not the patient reports having had chickenpox. Serologic testing to determine varicella immunity is not needed before vaccination, nor was it required for entry in the Shingles Prevention Study.

Furthermore, in VZV-seronegative adults, giving the zoster vaccine is thought to provide at least partial protection against varicella, and no data indicate any excessive adverse effects in this population.

VACCINATE EVEN IF THE PATIENT HAS HAD SHINGLES

The ACIP says that people with a history of zoster can be vaccinated. Recurrent zoster has been confirmed in immunocompetent patients soon after a previous episode. There is no test to confirm prior zoster episodes, and if the patient is immunocompetent, no different safety concerns are anticipated with vaccination in this group.16

ADVERSE EFFECTS ARE MILD

No significant safety concerns have been noted with zoster vaccine. Mild local reactions (erythema, swelling, pain, pruritus) and headache are the most common adverse events. There have been no differences in the numbers and types of serious adverse events during the 42 days after receipt of vaccine or placebo.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Contraindications to zoster vaccine are:

- A history of anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions to gelatin, neomycin, or other components of the vaccine

- Acquired or primary immune deficiency states, including AIDS

- Cancer chemotherapy or radiotherapy

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

- Organ transplantation

- Active untreated tuberculosis

- Pregnancy or breast-feeding.

However, patients with leukemia in remission who have not received chemotherapy (eg, alkylating drugs or antimetabolites) or radiation for at least 3 months can receive zoster vaccine.

Although zoster vaccine is contraindicated in conditions of cellular immune deficiency, patients with humoral immunodeficiency (eg, hypogammaglobulinemia or dysgammaglobulinemia) can receive it.

Diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure, coronary artery disease, chronic lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and other medical conditions are not considered contraindications to the vaccine.

The ACIP does not recommend any upper age limit for the vaccine, and preventing zoster is particularly important in the oldest elderly because they have the highest incidence of zoster and postherpetic neuralgia.16

Do not vaccinate during immunosuppressive treatment

If immunosuppressive treatment is planned (eg, with corticosteroids or anti-tumor necrosis factor agents), the vaccine should be given at least 14 days (preferably 1 month) before immunosuppression begins.

The safety and efficacy of zoster vaccine is unknown in patients receiving recombinant human immune mediators and immune modulators, especially anti-tumor necrosis factor agents such as adalimumab (Humira), infliximab (Remicade), or etanercept (Enbrel). These patients should be vaccinated 1 month before starting the treatment or 1 month after stopping it.16

Patients on corticosteroids in doses equivalent to prednisone 20 mg/day or more for 2 or more weeks should not be vaccinated against zoster unless the steroids have been stopped for at least 1 month.11

Low doses of methotrexate (< 0.4 mg/kg/week), azathioprine (Azasan) (< 3.0 mg/kg/day), or 6-mercaptopurine (Purinethol, 6-MP) (< 1.5 mg/kg/day) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, polymyositis, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and other conditions are not contraindications to zoster vaccination.

Medications against herpes, such as acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), or valacyclovir (Valtrex) should be discontinued at least 24 hours before zoster vaccination and should not be started until 14 days afterward.

COSTLY AND EFFECTIVE? OR COST-EFFECTIVE?

The average cost associated with an acute episode of zoster ranges from $112 to $287 if treated on an outpatient basis and $3,221 to $7,206 if the patient is hospitalized (costs in 2006).19

Although pharmacists are licensed to administer influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, several states do not specifically allow them to administer zoster vaccine. Moreover, one usually cannot provide the vaccine out of the office stock and get reimbursed for it (except by some private insurance companies). Instead, the patient needs to take a prescription to a local pharmacy, where the vaccine is placed on ice and then brought back to the physician’s office for administration.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends routinely giving a single dose of live zoster vaccine to immunocompetent patients age 60 and older at their first clinical encounter. The vaccine effectively prevents shingles and postherpetic neuralgia and their associated burden of illness. Although not all insurance companies pay for it yet, it should be offered to all patients for whom it is indicated to increase their health-related quality of life.

IMMUNITY WANES WITH AGE

Shingles, also known as zoster or herpes zoster, is caused by retrograde transport of the varicella zoster virus (VZV) from the ganglia to the skin in a host who had a primary varicella infection (chickenpox) in the past.1 Although shingles is not one of the diseases that must be reported to public health authorities, more than 1 million cases are estimated to occur each year in the United States. From 10% to 30% of people develop shingles during their lifetime.2,3

The elderly are at particular risk of shingles, because immunity to VZV wanes as a part of normal aging. As many as 50% of people who live to age 85 will have shingles at some point in their life.

Moreover, about 20% of patients with shingles develop postherpetic neuralgia,3,4 the pain and discomfort of which can be disabling and can diminish quality of life.5

Antiviral therapy reduces the severity and duration of an episode of shingles but does not prevent postherpetic neuralgia.2,6 Steroids provide additional relief of acute zoster pain, but they do not clearly prevent postherpetic neuralgia either and should be used only in combination with antiviral drugs. Preventing zoster and postherpetic neuralgia by routine vaccination should be a goal in our efforts to promote healthy aging, especially with the increasing number of elderly in our country.7

THE VACCINE IS EFFECTIVE: THE SHINGLES PREVENTION STUDY

The Shingles Prevention Study was a prospective, double-blind trial in more than 38,000 adults, median age 69 years (range 59–99), who were followed for a mean of 3.13 years (range 1 day to 4.9 years) after receiving the zoster vaccine or placebo.8–10

The virus in the vaccine did not elicit shingles in any patient. After vaccination, if lesions did occur, they were from the patient’s native strain, not the vaccine strain.8

ZOSTAVAX

The US Food and Drug Administration approved the zoster vaccine in May 2006 for prevention of herpes zoster in people age 60 and older. Zostavax, licensed by Merck, is the only vaccine available for this purpose.11,12 Zoster vaccine is not indicated for treating episodes of shingles or postherpetic neuralgia or for preventing primary varicella infection (chickenpox).

Zostavax does not contain thimerosal, a mercury-based preservative used in other vaccines. Therefore, it must be kept frozen at an average temperature of –15°C (5°F) and should not be used if its temperature rises above –5°C (23°F).13,14 Just before it is given, the vaccine is reconstituted with the supplied diluents and then injected subcutaneously in the deltoid region.12

No booster dose is recommended at present. Also, many cases of herpes zoster occur in people under age 60, for whom there is no recommendation.11,15 Although the vaccine would probably be safe and effective in this younger group, data are insufficient to recommend vaccinating them.16

ZOSTER VACCINE (ZOSTAVAX) IS NOT CHICKENPOX VACCINE (VARIVAX)

Both Zostavax and the chickenpox vaccine (Varivax) are live, attenuated vaccines from the same Oka/Merck strain of the virus, but Zostavax is about 14 times more potent than Varivax (Zostavax contains 8,700–60,000 plaque-forming units of virus, whereas Varivax contains 1,350), and they should not be used interchangeably.14

GIVING ZOSTER VACCINE WITH OTHER VACCINES IN THE ELDERLY

Zostavax can be given either simultaneously with or at any time before or after any inactivated vaccine (such as tetanus toxoid, influenza, pneumococcus). However, each vaccine must be given in a separate syringe at a different anatomic site.17

VACCINATE EVEN IF THE PATIENT DOESN’T RECALL HAVING CHICKENPOX

Even in people who do not recall ever having chickenpox, the rate of VZV seropositivity is very high (> 95% in those over age 60 in the United States).18 The ACIP recommends vaccination whether or not the patient reports having had chickenpox. Serologic testing to determine varicella immunity is not needed before vaccination, nor was it required for entry in the Shingles Prevention Study.

Furthermore, in VZV-seronegative adults, giving the zoster vaccine is thought to provide at least partial protection against varicella, and no data indicate any excessive adverse effects in this population.

VACCINATE EVEN IF THE PATIENT HAS HAD SHINGLES

The ACIP says that people with a history of zoster can be vaccinated. Recurrent zoster has been confirmed in immunocompetent patients soon after a previous episode. There is no test to confirm prior zoster episodes, and if the patient is immunocompetent, no different safety concerns are anticipated with vaccination in this group.16

ADVERSE EFFECTS ARE MILD

No significant safety concerns have been noted with zoster vaccine. Mild local reactions (erythema, swelling, pain, pruritus) and headache are the most common adverse events. There have been no differences in the numbers and types of serious adverse events during the 42 days after receipt of vaccine or placebo.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Contraindications to zoster vaccine are:

- A history of anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions to gelatin, neomycin, or other components of the vaccine

- Acquired or primary immune deficiency states, including AIDS

- Cancer chemotherapy or radiotherapy

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

- Organ transplantation

- Active untreated tuberculosis

- Pregnancy or breast-feeding.

However, patients with leukemia in remission who have not received chemotherapy (eg, alkylating drugs or antimetabolites) or radiation for at least 3 months can receive zoster vaccine.

Although zoster vaccine is contraindicated in conditions of cellular immune deficiency, patients with humoral immunodeficiency (eg, hypogammaglobulinemia or dysgammaglobulinemia) can receive it.

Diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure, coronary artery disease, chronic lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and other medical conditions are not considered contraindications to the vaccine.

The ACIP does not recommend any upper age limit for the vaccine, and preventing zoster is particularly important in the oldest elderly because they have the highest incidence of zoster and postherpetic neuralgia.16

Do not vaccinate during immunosuppressive treatment

If immunosuppressive treatment is planned (eg, with corticosteroids or anti-tumor necrosis factor agents), the vaccine should be given at least 14 days (preferably 1 month) before immunosuppression begins.

The safety and efficacy of zoster vaccine is unknown in patients receiving recombinant human immune mediators and immune modulators, especially anti-tumor necrosis factor agents such as adalimumab (Humira), infliximab (Remicade), or etanercept (Enbrel). These patients should be vaccinated 1 month before starting the treatment or 1 month after stopping it.16

Patients on corticosteroids in doses equivalent to prednisone 20 mg/day or more for 2 or more weeks should not be vaccinated against zoster unless the steroids have been stopped for at least 1 month.11

Low doses of methotrexate (< 0.4 mg/kg/week), azathioprine (Azasan) (< 3.0 mg/kg/day), or 6-mercaptopurine (Purinethol, 6-MP) (< 1.5 mg/kg/day) for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, polymyositis, sarcoidosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and other conditions are not contraindications to zoster vaccination.

Medications against herpes, such as acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), or valacyclovir (Valtrex) should be discontinued at least 24 hours before zoster vaccination and should not be started until 14 days afterward.

COSTLY AND EFFECTIVE? OR COST-EFFECTIVE?

The average cost associated with an acute episode of zoster ranges from $112 to $287 if treated on an outpatient basis and $3,221 to $7,206 if the patient is hospitalized (costs in 2006).19

Although pharmacists are licensed to administer influenza and pneumococcal vaccines, several states do not specifically allow them to administer zoster vaccine. Moreover, one usually cannot provide the vaccine out of the office stock and get reimbursed for it (except by some private insurance companies). Instead, the patient needs to take a prescription to a local pharmacy, where the vaccine is placed on ice and then brought back to the physician’s office for administration.

- Nagel MA, Gilden DH. The protean neurologic manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Cleve Clin J Med 2007; 74:489–504.

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:340–346.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, Sweeney EW, Dworkin RH. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:342–348.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965; 58:9–20.

- Lydick E, Epstein RS, Himmelberger D, White CJ. Herpes zoster and quality of life: a self-limited disease with severe impact. Neurology 1995; 45:S52–S53.

- Kost RG, Straus SE. Postherpetic neuralgia—pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:32–42.

- Johnson R, McElhaney J, Pedalino B, Levin M. Prevention of herpes zoster and its painful and debilitating complications. Int J Infect Dis 2007; 11( suppl 2):S43–S48.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2271–2284.

- Burke MS. Herpes zoster vaccine: clinical trial evidence and implications for medical practice. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2007; 107( suppl 1):S14–S18.

- Betts RF. Vaccination strategies for the prevention of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57( suppl):S143–S147.

- Kroger AT, Atkinson WL, Marcuse EK, Pickering LK. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–48.

- Merck. Zostavax zoster vaccine live suspension for subcutaneous injection. www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/z/zostavax_pi.pdf. Accessed 11/17/2008.

- Holodniy M. Prevention of shingles by varicella zoster virus vaccination. Expert Rev Vaccines 2006; 5:431–443.

- Herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2006; 48:73–74.

- Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1605–1609.

- Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2008; 57:1–30.

- Bader MS. Immunization for the elderly. Am J Med Sci 2007; 334:481–486.

- Kilgore PE, Kruszon-Moran D, Seward JF, et al. Varicella in Americans from NHANES III: implications for control through routine immunization. J Med Virol 2003; 70( suppl 1):S111–S118.

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, Baser O, Hawkins K. Healthcare costs of acute and chronic pain associated with a diagnosis of herpes zoster. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:1168–1175.

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, Hawkins K. Health care expenditure burden of persisting herpes zoster pain. Pain Med 2008; 9:348–353.

- Nagel MA, Gilden DH. The protean neurologic manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Cleve Clin J Med 2007; 74:489–504.

- Gnann JW, Whitley RJ. Clinical practice. Herpes zoster. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:340–346.

- Katz J, Cooper EM, Walther RR, Sweeney EW, Dworkin RH. Acute pain in herpes zoster and its impact on health-related quality of life. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:342–348.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med 1965; 58:9–20.

- Lydick E, Epstein RS, Himmelberger D, White CJ. Herpes zoster and quality of life: a self-limited disease with severe impact. Neurology 1995; 45:S52–S53.

- Kost RG, Straus SE. Postherpetic neuralgia—pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:32–42.

- Johnson R, McElhaney J, Pedalino B, Levin M. Prevention of herpes zoster and its painful and debilitating complications. Int J Infect Dis 2007; 11( suppl 2):S43–S48.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2271–2284.

- Burke MS. Herpes zoster vaccine: clinical trial evidence and implications for medical practice. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2007; 107( suppl 1):S14–S18.

- Betts RF. Vaccination strategies for the prevention of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57( suppl):S143–S147.

- Kroger AT, Atkinson WL, Marcuse EK, Pickering LK. General recommendations on immunization: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2006; 55:1–48.

- Merck. Zostavax zoster vaccine live suspension for subcutaneous injection. www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/z/zostavax_pi.pdf. Accessed 11/17/2008.

- Holodniy M. Prevention of shingles by varicella zoster virus vaccination. Expert Rev Vaccines 2006; 5:431–443.

- Herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax). Med Lett Drugs Ther 2006; 48:73–74.

- Donahue JG, Choo PW, Manson JE, Platt R. The incidence of herpes zoster. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1605–1609.

- Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep 2008; 57:1–30.

- Bader MS. Immunization for the elderly. Am J Med Sci 2007; 334:481–486.

- Kilgore PE, Kruszon-Moran D, Seward JF, et al. Varicella in Americans from NHANES III: implications for control through routine immunization. J Med Virol 2003; 70( suppl 1):S111–S118.

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, Baser O, Hawkins K. Healthcare costs of acute and chronic pain associated with a diagnosis of herpes zoster. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55:1168–1175.

- Dworkin RH, White R, O’Connor AB, Hawkins K. Health care expenditure burden of persisting herpes zoster pain. Pain Med 2008; 9:348–353.