User login

Roth Spots—More than Meets the Eye

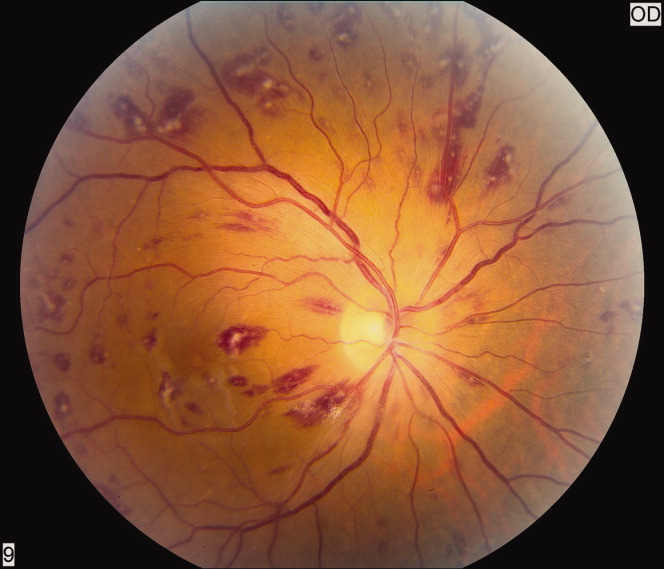

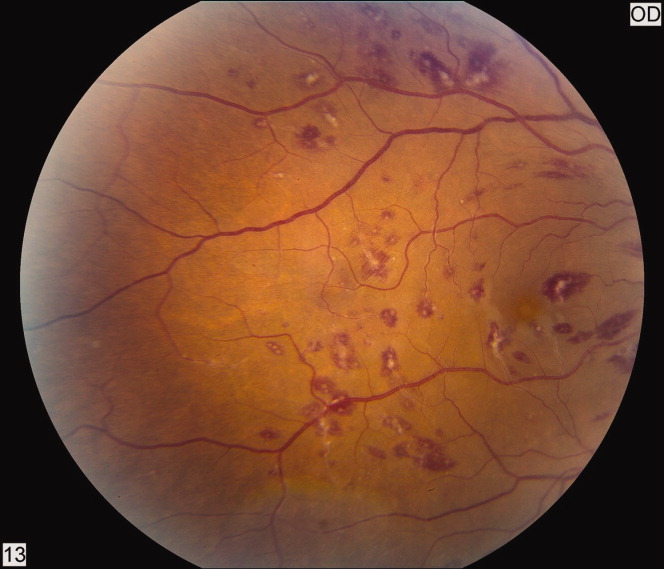

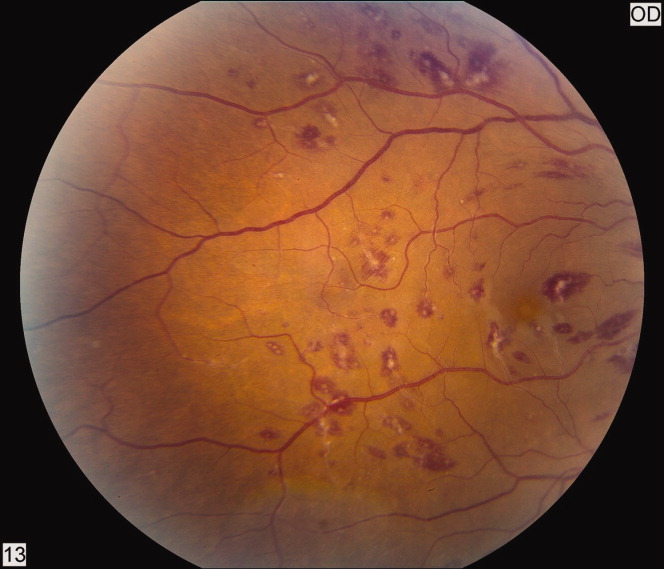

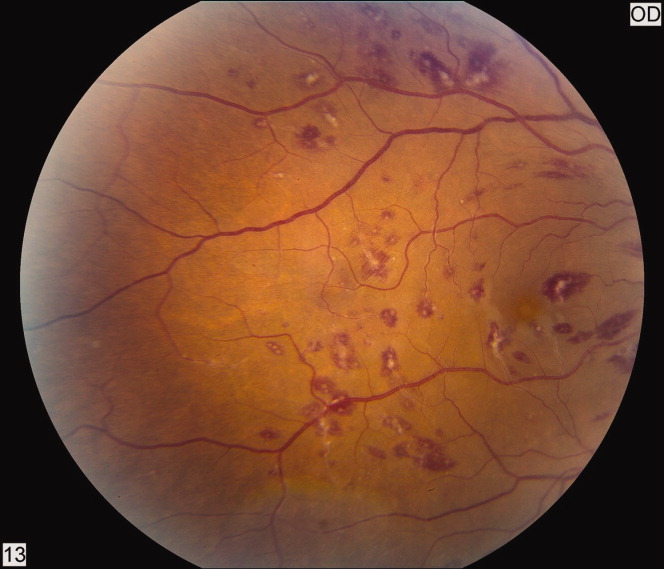

A 50‐year‐old female patient with a past medical history of Sjogren's syndrome and polymyositis presented with fever, rash, swelling, and pain in her extremities. Skin biopsy confirmed vasculitis. She was treated with steroids and azathioprine. However, she developed sudden‐onset central visual blurring in her right eye on the fifth day of hospitalization. Fundoscopic exam showed multiple central white‐centered retinal hemorrhages (Roth spots, Figures 1, 2) and vascular sheathing, consistent with retinal vasculitis. Blood cultures were negative. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms were normal. She was treated with high‐dose intravenous steroids and cyclophosphamide, with visual improvement and a marked reduction in the number of Roth spots.

Roth spots 1 are nonspecific intraretinal hemorrhagic lesions with a white center due to fibrin deposition. Although historically associated with infective endocarditis, they can also occur in other systemic diseases such as connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, leukemia, diabetes, hypertension, anemia, trauma, as well as disseminated bacterial and fungal infections.

- , , .White centered hemorrhages: their significance.Ophthalmology.1980;87:66–69.

A 50‐year‐old female patient with a past medical history of Sjogren's syndrome and polymyositis presented with fever, rash, swelling, and pain in her extremities. Skin biopsy confirmed vasculitis. She was treated with steroids and azathioprine. However, she developed sudden‐onset central visual blurring in her right eye on the fifth day of hospitalization. Fundoscopic exam showed multiple central white‐centered retinal hemorrhages (Roth spots, Figures 1, 2) and vascular sheathing, consistent with retinal vasculitis. Blood cultures were negative. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms were normal. She was treated with high‐dose intravenous steroids and cyclophosphamide, with visual improvement and a marked reduction in the number of Roth spots.

Roth spots 1 are nonspecific intraretinal hemorrhagic lesions with a white center due to fibrin deposition. Although historically associated with infective endocarditis, they can also occur in other systemic diseases such as connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, leukemia, diabetes, hypertension, anemia, trauma, as well as disseminated bacterial and fungal infections.

A 50‐year‐old female patient with a past medical history of Sjogren's syndrome and polymyositis presented with fever, rash, swelling, and pain in her extremities. Skin biopsy confirmed vasculitis. She was treated with steroids and azathioprine. However, she developed sudden‐onset central visual blurring in her right eye on the fifth day of hospitalization. Fundoscopic exam showed multiple central white‐centered retinal hemorrhages (Roth spots, Figures 1, 2) and vascular sheathing, consistent with retinal vasculitis. Blood cultures were negative. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms were normal. She was treated with high‐dose intravenous steroids and cyclophosphamide, with visual improvement and a marked reduction in the number of Roth spots.

Roth spots 1 are nonspecific intraretinal hemorrhagic lesions with a white center due to fibrin deposition. Although historically associated with infective endocarditis, they can also occur in other systemic diseases such as connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, leukemia, diabetes, hypertension, anemia, trauma, as well as disseminated bacterial and fungal infections.

- , , .White centered hemorrhages: their significance.Ophthalmology.1980;87:66–69.

- , , .White centered hemorrhages: their significance.Ophthalmology.1980;87:66–69.

Large gallstone ileus

A 92‐year old man presented with a 5‐day history of obstipation, nausea, and vomiting. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed a 4.1‐cm gallstone impacted in the sigmoid colon (Figure 1). The proximal colon was diffusely dilated in caliber consistent with obstruction (Figure 1B). The CT also showed a cholecystocolic fistula at the hepatic flexure of the colon (Figure 2) with an edematous gallbladder wall and a residual 3.8‐cm gallstone. Under colonoscopic guidance the stone was fragmented using intraluminal shock wave lithotripsy and other endoscopic techniques. The pieces were retrieved (Figure 3, shown reassembled). Cholecystectomy, common hepatic duct repair, and fistula takedown were electively performed to prevent recurrence.

Gallstone ileus is the mechanical impaction of gallstones within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. It requires the formation of either a biliary‐enteric fistula or less often a choledocho‐enteric fistula. Usually the stone must be 2 cm or greater to cause obstruction.1 The site of obstruction is typically the terminal ileum or ileocecal valve because of the smaller diameter lumen and less active peristalsis. Although mortality rates approach 15%,2 this patient did remarkably well with early recognition, use of complex endoscopic removal, and avoidance of urgent laparotomy.

- ,.Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases.Am Surg.1994;60:441–446.

- ,,,,,.[Gallstone Ileus: results of analysis of a series of 40 patients].Gastroenterol Hepatol.2001;24:489–494. In Spanish.

A 92‐year old man presented with a 5‐day history of obstipation, nausea, and vomiting. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed a 4.1‐cm gallstone impacted in the sigmoid colon (Figure 1). The proximal colon was diffusely dilated in caliber consistent with obstruction (Figure 1B). The CT also showed a cholecystocolic fistula at the hepatic flexure of the colon (Figure 2) with an edematous gallbladder wall and a residual 3.8‐cm gallstone. Under colonoscopic guidance the stone was fragmented using intraluminal shock wave lithotripsy and other endoscopic techniques. The pieces were retrieved (Figure 3, shown reassembled). Cholecystectomy, common hepatic duct repair, and fistula takedown were electively performed to prevent recurrence.

Gallstone ileus is the mechanical impaction of gallstones within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. It requires the formation of either a biliary‐enteric fistula or less often a choledocho‐enteric fistula. Usually the stone must be 2 cm or greater to cause obstruction.1 The site of obstruction is typically the terminal ileum or ileocecal valve because of the smaller diameter lumen and less active peristalsis. Although mortality rates approach 15%,2 this patient did remarkably well with early recognition, use of complex endoscopic removal, and avoidance of urgent laparotomy.

A 92‐year old man presented with a 5‐day history of obstipation, nausea, and vomiting. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen revealed a 4.1‐cm gallstone impacted in the sigmoid colon (Figure 1). The proximal colon was diffusely dilated in caliber consistent with obstruction (Figure 1B). The CT also showed a cholecystocolic fistula at the hepatic flexure of the colon (Figure 2) with an edematous gallbladder wall and a residual 3.8‐cm gallstone. Under colonoscopic guidance the stone was fragmented using intraluminal shock wave lithotripsy and other endoscopic techniques. The pieces were retrieved (Figure 3, shown reassembled). Cholecystectomy, common hepatic duct repair, and fistula takedown were electively performed to prevent recurrence.

Gallstone ileus is the mechanical impaction of gallstones within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. It requires the formation of either a biliary‐enteric fistula or less often a choledocho‐enteric fistula. Usually the stone must be 2 cm or greater to cause obstruction.1 The site of obstruction is typically the terminal ileum or ileocecal valve because of the smaller diameter lumen and less active peristalsis. Although mortality rates approach 15%,2 this patient did remarkably well with early recognition, use of complex endoscopic removal, and avoidance of urgent laparotomy.

- ,.Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases.Am Surg.1994;60:441–446.

- ,,,,,.[Gallstone Ileus: results of analysis of a series of 40 patients].Gastroenterol Hepatol.2001;24:489–494. In Spanish.

- ,.Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases.Am Surg.1994;60:441–446.

- ,,,,,.[Gallstone Ileus: results of analysis of a series of 40 patients].Gastroenterol Hepatol.2001;24:489–494. In Spanish.

It Starts With a Dog Scratch

A 63‐year‐old female with a history of essential thrombocythemia and hypertension presented with a 4‐week history of a worsening ulcer on her right second digit. Initially, the patient attributed the wound to a dog scratch but sought further treatment at an outside clinic when she did not see improvement. She was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and was treated with unknown oral antibiotics and silvadene cream. The ulcer continued to worsen and the patient presented to our hospital. On physical exam, an 8 cm 3 cm ulcer was observed on the right second digit. It had violaceous rolled up borders, granulation tissue, fibrinous exudates, and areas of necrotic tissue (Figure 1). The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Initial laboratory values included hemoglobin 12.5 gm/dL, white blood cell count 31.2 K/UL, and platelets 625 gm/dL. An x‐ray of the hand showed soft tissue swelling with no evidence of osteomyelitis. The ulcer was evaluated and treated as an infected wound. The patient was started on broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics and underwent excisional debridement with biopsy. Blood and wound cultures were negative for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, fungi, and acid‐fast bacilli. Pathology from the biopsy showed extensive necrosis and acute inflammation. The patient was discharged home with 10 days of oral antibiotics, and instructions for wound care. Upon follow‐up 1 week later, the patient complained of intense pain and worsening of the ulcer prompting readmission. Dermatology was consulted and diagnosed pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). The patient was started on prednisone, 60 mg daily and azathioprine, 50 mg daily. The ulcer slowly improved (Figure 2) and the steroid dosage was tapered. She was finally discharged home with a 6‐week taper of prednisone, azathioprine, and home health consultation for assistance with wound care.0, 0

PG is an ulcerative neutrophilic dermatosis. In up to 50% of cases, PG is associated with either inflammatory bowel disease, collagen vascular disease, or hematologic disorders.1 Although an immune‐modulated pathway may be involved, the etiology and pathophysiology of PG is still unknown.1 Furthermore, PG is a diagnosis of exclusion.1 However, PG does have clinical findings which favor the diagnosis. There are 4 main subtypes of PG; ulcerative or classic, pustular, bullous, and vegetative.1 Although myeloproliferative disorders are more specifically associated with the bullous form, our patient presented with the classic subtype.2, 3 In the classic subtype, patients will often describe an initial pustule which then necroses, forming an ulcer with a reddish/purple or gray undermined border and a red halo surrounding the ulcer. PG can occur anywhere on the body however it is more frequently seen on the legs. A clinically relevant feature of PG, emphasized in this case, is pathergy. Thus, PG can develop or worsen secondary to mild trauma. PG has been reported to form after mild trauma such as an insect bite or dog scratch and has been documented to worsen with debridement, skin grafting, and biopsies.1 Another feature and clinical clue of PG as manifested by our patient is intense pain. The skin biopsy, however, is usually nonspecific and can reveal findings which include edema, neutrophil infiltration, abscess formation, necrosis, and thrombosis of vessels.1 In patients with PG associated with myeloproliferative syndromes, no correlation has been shown between the time of diagnosis and the severity of the underlying myeloproliferative syndrome.2, 3 Treatment for PG depends on extent of involvement and association with underlying disease and can include local, oral, or intravenous corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, appropriate wound care, and treatment of associated disease.4

PG is a diagnosis of exclusion. Underlying infection, vasculitis, malignancy, and Sweet's syndrome should be considered in the differential. However, one must consider PG in the differential diagnosis of an ulcer in a patient with an underlying predisposing illness, when the ulcer has characteristics of pathergy and intense pain, and is not healing appropriately as illustrated in this case.

- ,,,,.Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2009;23(9):1008–1017.

- ,.Pyoderma gangrenosum and myeloproliferative disorders: report of a case and review of literature.Arch Intern Med.1979;139:932–934.

- ,.Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with essential thrombocythemia.J Cutan Med Surg.2000;2:107–109.

- ,,.Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review.J Cutan Pathol.2003;30:97–107.

A 63‐year‐old female with a history of essential thrombocythemia and hypertension presented with a 4‐week history of a worsening ulcer on her right second digit. Initially, the patient attributed the wound to a dog scratch but sought further treatment at an outside clinic when she did not see improvement. She was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and was treated with unknown oral antibiotics and silvadene cream. The ulcer continued to worsen and the patient presented to our hospital. On physical exam, an 8 cm 3 cm ulcer was observed on the right second digit. It had violaceous rolled up borders, granulation tissue, fibrinous exudates, and areas of necrotic tissue (Figure 1). The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Initial laboratory values included hemoglobin 12.5 gm/dL, white blood cell count 31.2 K/UL, and platelets 625 gm/dL. An x‐ray of the hand showed soft tissue swelling with no evidence of osteomyelitis. The ulcer was evaluated and treated as an infected wound. The patient was started on broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics and underwent excisional debridement with biopsy. Blood and wound cultures were negative for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, fungi, and acid‐fast bacilli. Pathology from the biopsy showed extensive necrosis and acute inflammation. The patient was discharged home with 10 days of oral antibiotics, and instructions for wound care. Upon follow‐up 1 week later, the patient complained of intense pain and worsening of the ulcer prompting readmission. Dermatology was consulted and diagnosed pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). The patient was started on prednisone, 60 mg daily and azathioprine, 50 mg daily. The ulcer slowly improved (Figure 2) and the steroid dosage was tapered. She was finally discharged home with a 6‐week taper of prednisone, azathioprine, and home health consultation for assistance with wound care.0, 0

PG is an ulcerative neutrophilic dermatosis. In up to 50% of cases, PG is associated with either inflammatory bowel disease, collagen vascular disease, or hematologic disorders.1 Although an immune‐modulated pathway may be involved, the etiology and pathophysiology of PG is still unknown.1 Furthermore, PG is a diagnosis of exclusion.1 However, PG does have clinical findings which favor the diagnosis. There are 4 main subtypes of PG; ulcerative or classic, pustular, bullous, and vegetative.1 Although myeloproliferative disorders are more specifically associated with the bullous form, our patient presented with the classic subtype.2, 3 In the classic subtype, patients will often describe an initial pustule which then necroses, forming an ulcer with a reddish/purple or gray undermined border and a red halo surrounding the ulcer. PG can occur anywhere on the body however it is more frequently seen on the legs. A clinically relevant feature of PG, emphasized in this case, is pathergy. Thus, PG can develop or worsen secondary to mild trauma. PG has been reported to form after mild trauma such as an insect bite or dog scratch and has been documented to worsen with debridement, skin grafting, and biopsies.1 Another feature and clinical clue of PG as manifested by our patient is intense pain. The skin biopsy, however, is usually nonspecific and can reveal findings which include edema, neutrophil infiltration, abscess formation, necrosis, and thrombosis of vessels.1 In patients with PG associated with myeloproliferative syndromes, no correlation has been shown between the time of diagnosis and the severity of the underlying myeloproliferative syndrome.2, 3 Treatment for PG depends on extent of involvement and association with underlying disease and can include local, oral, or intravenous corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, appropriate wound care, and treatment of associated disease.4

PG is a diagnosis of exclusion. Underlying infection, vasculitis, malignancy, and Sweet's syndrome should be considered in the differential. However, one must consider PG in the differential diagnosis of an ulcer in a patient with an underlying predisposing illness, when the ulcer has characteristics of pathergy and intense pain, and is not healing appropriately as illustrated in this case.

A 63‐year‐old female with a history of essential thrombocythemia and hypertension presented with a 4‐week history of a worsening ulcer on her right second digit. Initially, the patient attributed the wound to a dog scratch but sought further treatment at an outside clinic when she did not see improvement. She was given a diagnosis of cellulitis and was treated with unknown oral antibiotics and silvadene cream. The ulcer continued to worsen and the patient presented to our hospital. On physical exam, an 8 cm 3 cm ulcer was observed on the right second digit. It had violaceous rolled up borders, granulation tissue, fibrinous exudates, and areas of necrotic tissue (Figure 1). The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Initial laboratory values included hemoglobin 12.5 gm/dL, white blood cell count 31.2 K/UL, and platelets 625 gm/dL. An x‐ray of the hand showed soft tissue swelling with no evidence of osteomyelitis. The ulcer was evaluated and treated as an infected wound. The patient was started on broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics and underwent excisional debridement with biopsy. Blood and wound cultures were negative for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, fungi, and acid‐fast bacilli. Pathology from the biopsy showed extensive necrosis and acute inflammation. The patient was discharged home with 10 days of oral antibiotics, and instructions for wound care. Upon follow‐up 1 week later, the patient complained of intense pain and worsening of the ulcer prompting readmission. Dermatology was consulted and diagnosed pyoderma gangrenosum (PG). The patient was started on prednisone, 60 mg daily and azathioprine, 50 mg daily. The ulcer slowly improved (Figure 2) and the steroid dosage was tapered. She was finally discharged home with a 6‐week taper of prednisone, azathioprine, and home health consultation for assistance with wound care.0, 0

PG is an ulcerative neutrophilic dermatosis. In up to 50% of cases, PG is associated with either inflammatory bowel disease, collagen vascular disease, or hematologic disorders.1 Although an immune‐modulated pathway may be involved, the etiology and pathophysiology of PG is still unknown.1 Furthermore, PG is a diagnosis of exclusion.1 However, PG does have clinical findings which favor the diagnosis. There are 4 main subtypes of PG; ulcerative or classic, pustular, bullous, and vegetative.1 Although myeloproliferative disorders are more specifically associated with the bullous form, our patient presented with the classic subtype.2, 3 In the classic subtype, patients will often describe an initial pustule which then necroses, forming an ulcer with a reddish/purple or gray undermined border and a red halo surrounding the ulcer. PG can occur anywhere on the body however it is more frequently seen on the legs. A clinically relevant feature of PG, emphasized in this case, is pathergy. Thus, PG can develop or worsen secondary to mild trauma. PG has been reported to form after mild trauma such as an insect bite or dog scratch and has been documented to worsen with debridement, skin grafting, and biopsies.1 Another feature and clinical clue of PG as manifested by our patient is intense pain. The skin biopsy, however, is usually nonspecific and can reveal findings which include edema, neutrophil infiltration, abscess formation, necrosis, and thrombosis of vessels.1 In patients with PG associated with myeloproliferative syndromes, no correlation has been shown between the time of diagnosis and the severity of the underlying myeloproliferative syndrome.2, 3 Treatment for PG depends on extent of involvement and association with underlying disease and can include local, oral, or intravenous corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, appropriate wound care, and treatment of associated disease.4

PG is a diagnosis of exclusion. Underlying infection, vasculitis, malignancy, and Sweet's syndrome should be considered in the differential. However, one must consider PG in the differential diagnosis of an ulcer in a patient with an underlying predisposing illness, when the ulcer has characteristics of pathergy and intense pain, and is not healing appropriately as illustrated in this case.

- ,,,,.Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2009;23(9):1008–1017.

- ,.Pyoderma gangrenosum and myeloproliferative disorders: report of a case and review of literature.Arch Intern Med.1979;139:932–934.

- ,.Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with essential thrombocythemia.J Cutan Med Surg.2000;2:107–109.

- ,,.Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review.J Cutan Pathol.2003;30:97–107.

- ,,,,.Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2009;23(9):1008–1017.

- ,.Pyoderma gangrenosum and myeloproliferative disorders: report of a case and review of literature.Arch Intern Med.1979;139:932–934.

- ,.Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with essential thrombocythemia.J Cutan Med Surg.2000;2:107–109.

- ,,.Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review.J Cutan Pathol.2003;30:97–107.

Pott's Puffy Tumor

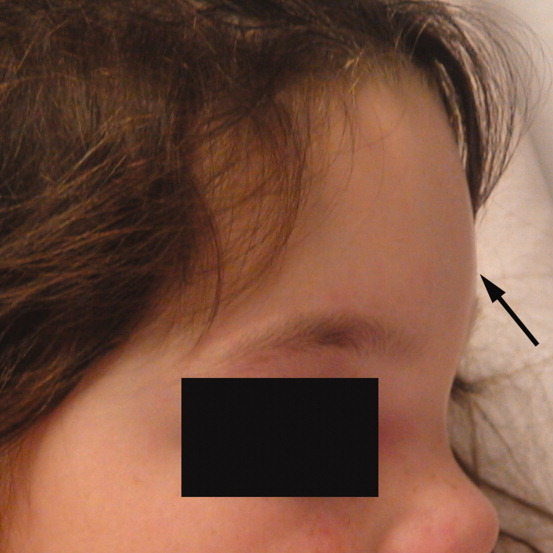

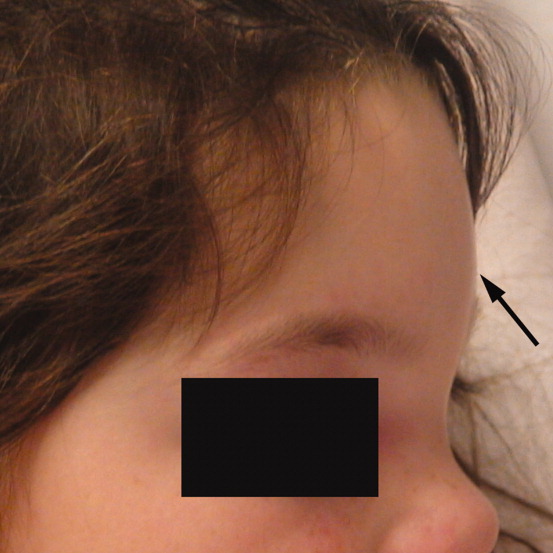

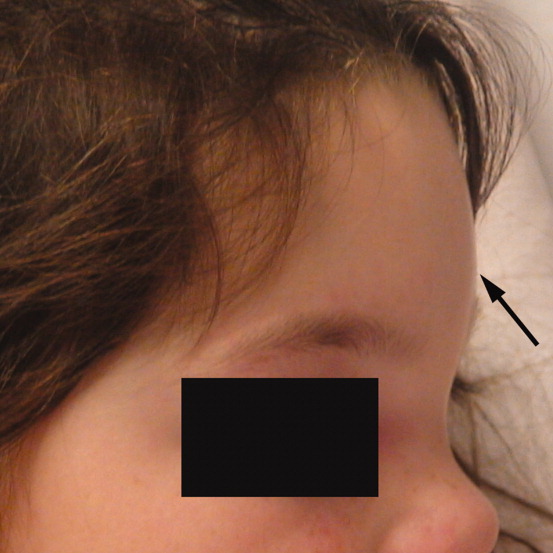

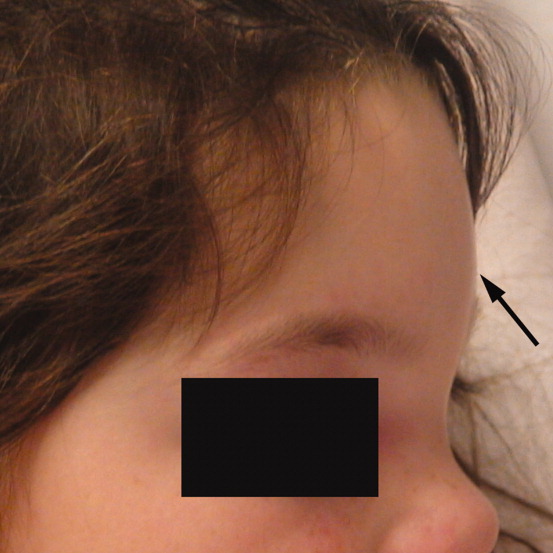

A 6‐year‐old girl with a history of bilateral myringotomies, tonsillectomy, and adenoidectomy 6 and 8 months prior, presented with forehead swelling. Eight days prior, she developed right ear pain, sore throat and fever followed by eye pain and headache for which she was evaluated and diagnosed with viral illness. On the day of presentation she awoke with forehead swelling, persistent headache, and recurrent fever.

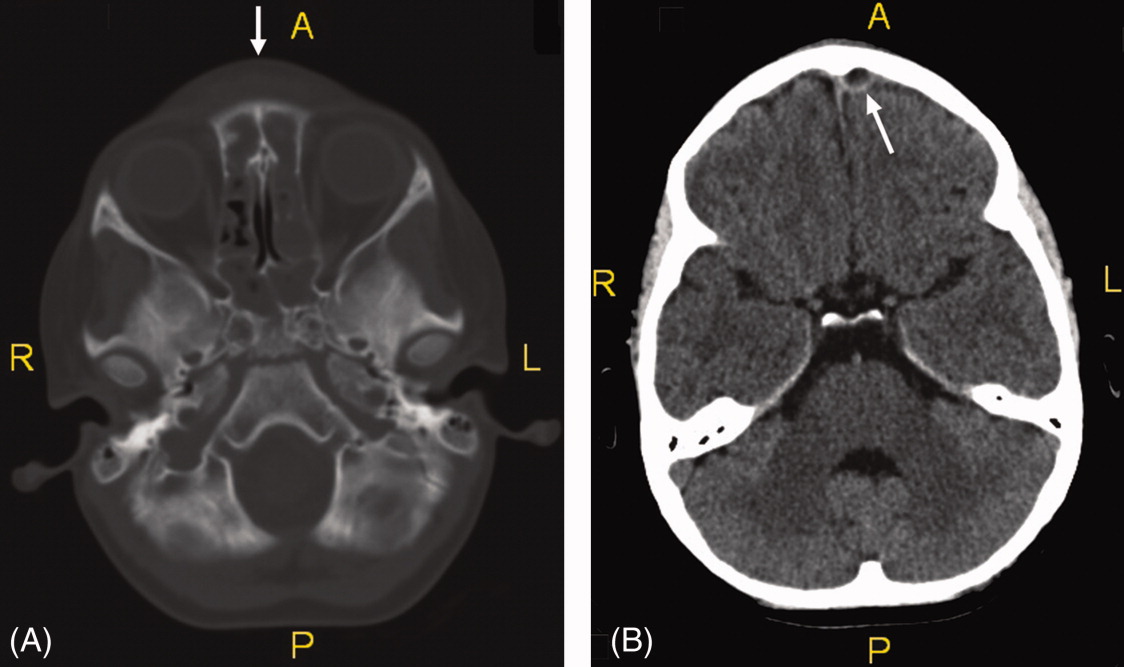

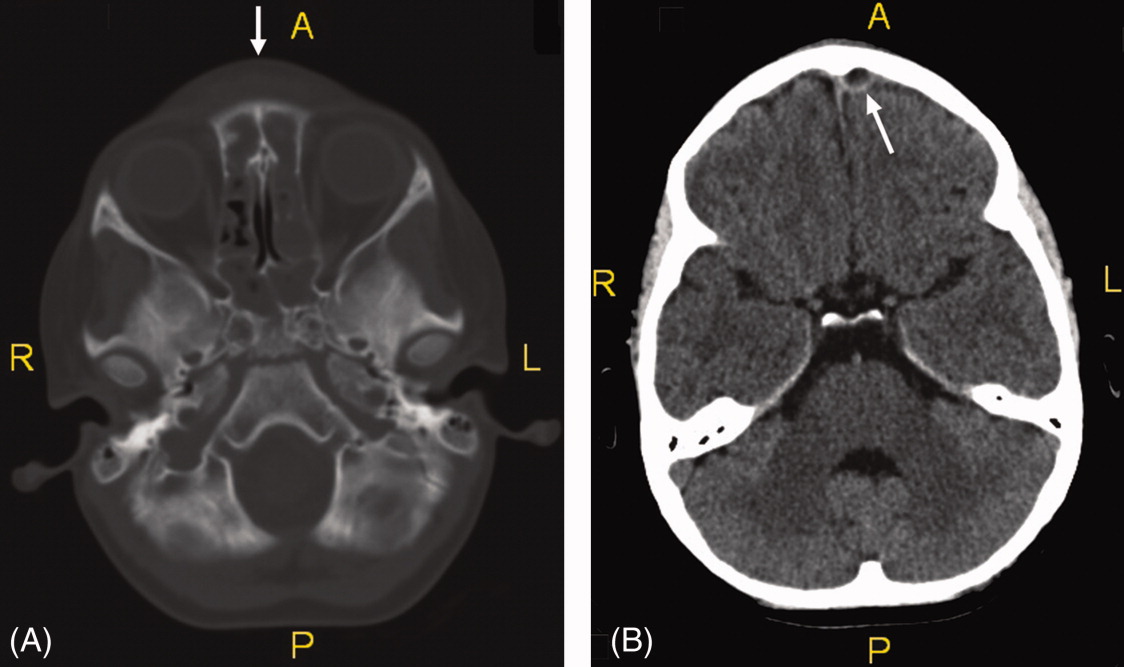

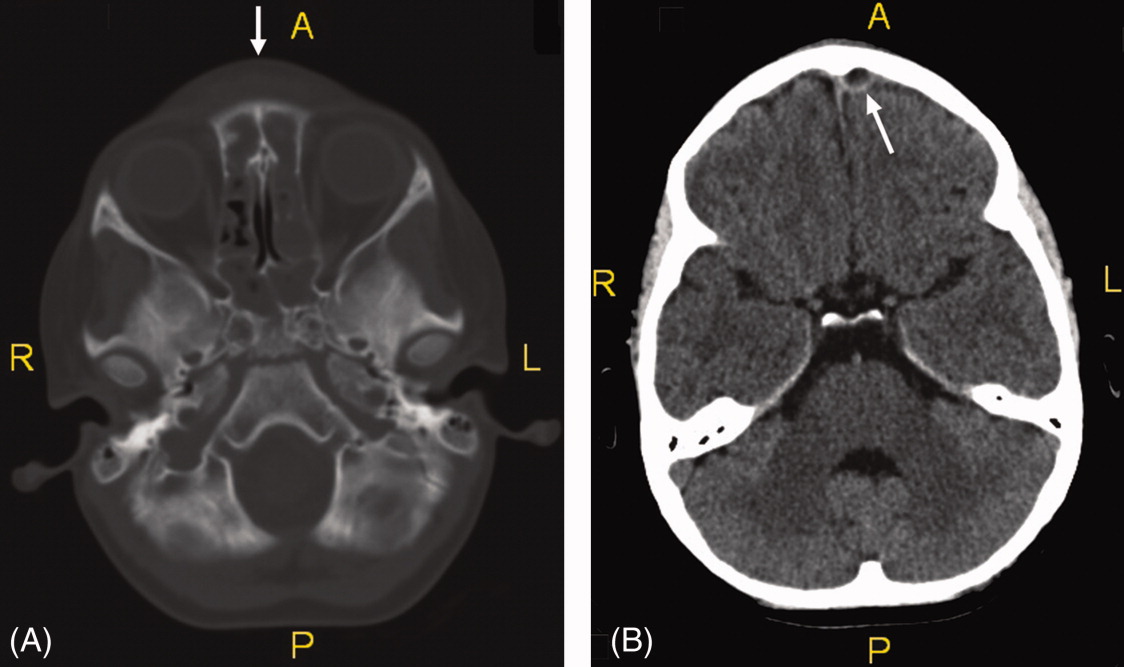

On exam she was afebrile. Central forehead swelling was noted without overlying erythema or fluctulence (Figure 1). Neurologic exam was normal. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed pan sinusitis with an extra‐axial fluid collection in the left frontal region (Figure 2).

Vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole were started empirically. She underwent bilateral maxillary antrostomy, total ethmoidectomy, and burr‐hole evacuation of the epidural abscess. Operative specimen cultures grew out Group A streptococci, after‐which antibiotic therapy was narrowed down to ampicillin/sulbactam alone.

Pott's puffy tumor, or osteomyelitis of the frontal bone with subperiosteal abscess formation, is rare in children less than 7 years of age and usually the result of a delay in diagnosis or inadequate treatment of rhinosinusitis.1 Risk factors include frontal sinusitis, head trauma, and less commonly, cocaine use, dental infection, or delayed neurosurgical or sinus surgery complications.2, 3 Fever, vomiting, forehead tenderness, and headache are the most common complaints, though seizure and focal neurologic findings have been described.2 CT scanning is the imaging modality of choice. Most commonly cultured organisms include Streptococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Bacteroides, and less commonly, Staphylococcus aureus.2, 4 Treatment includes empiric broad‐spectrum antibiotics that penetrate the blood‐brain barrier with early surgical drainage of the abscess and debridement of the osteomyelitic bone.4

- ,.Simultaneous intracranial and orbital complications of acute rhinosinusitis in children.Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.2004;68:619–625.

- ,,, et al.Pott's puffy tumor in children.Childs Nerv Syst.2010;26(1):53–60.

- ,,,,.A Pott's Puffy Tumour as a late complication of a frontal sinus reconstruction: case report and literature review.Rhinology.2009;47(4):470–475.

- ,,.An unusual cause of headache: Pott's puffy tumour.Eur J Emerg Med.2007;14(3):170–173.

A 6‐year‐old girl with a history of bilateral myringotomies, tonsillectomy, and adenoidectomy 6 and 8 months prior, presented with forehead swelling. Eight days prior, she developed right ear pain, sore throat and fever followed by eye pain and headache for which she was evaluated and diagnosed with viral illness. On the day of presentation she awoke with forehead swelling, persistent headache, and recurrent fever.

On exam she was afebrile. Central forehead swelling was noted without overlying erythema or fluctulence (Figure 1). Neurologic exam was normal. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed pan sinusitis with an extra‐axial fluid collection in the left frontal region (Figure 2).

Vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole were started empirically. She underwent bilateral maxillary antrostomy, total ethmoidectomy, and burr‐hole evacuation of the epidural abscess. Operative specimen cultures grew out Group A streptococci, after‐which antibiotic therapy was narrowed down to ampicillin/sulbactam alone.

Pott's puffy tumor, or osteomyelitis of the frontal bone with subperiosteal abscess formation, is rare in children less than 7 years of age and usually the result of a delay in diagnosis or inadequate treatment of rhinosinusitis.1 Risk factors include frontal sinusitis, head trauma, and less commonly, cocaine use, dental infection, or delayed neurosurgical or sinus surgery complications.2, 3 Fever, vomiting, forehead tenderness, and headache are the most common complaints, though seizure and focal neurologic findings have been described.2 CT scanning is the imaging modality of choice. Most commonly cultured organisms include Streptococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Bacteroides, and less commonly, Staphylococcus aureus.2, 4 Treatment includes empiric broad‐spectrum antibiotics that penetrate the blood‐brain barrier with early surgical drainage of the abscess and debridement of the osteomyelitic bone.4

A 6‐year‐old girl with a history of bilateral myringotomies, tonsillectomy, and adenoidectomy 6 and 8 months prior, presented with forehead swelling. Eight days prior, she developed right ear pain, sore throat and fever followed by eye pain and headache for which she was evaluated and diagnosed with viral illness. On the day of presentation she awoke with forehead swelling, persistent headache, and recurrent fever.

On exam she was afebrile. Central forehead swelling was noted without overlying erythema or fluctulence (Figure 1). Neurologic exam was normal. Noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the head showed pan sinusitis with an extra‐axial fluid collection in the left frontal region (Figure 2).

Vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole were started empirically. She underwent bilateral maxillary antrostomy, total ethmoidectomy, and burr‐hole evacuation of the epidural abscess. Operative specimen cultures grew out Group A streptococci, after‐which antibiotic therapy was narrowed down to ampicillin/sulbactam alone.

Pott's puffy tumor, or osteomyelitis of the frontal bone with subperiosteal abscess formation, is rare in children less than 7 years of age and usually the result of a delay in diagnosis or inadequate treatment of rhinosinusitis.1 Risk factors include frontal sinusitis, head trauma, and less commonly, cocaine use, dental infection, or delayed neurosurgical or sinus surgery complications.2, 3 Fever, vomiting, forehead tenderness, and headache are the most common complaints, though seizure and focal neurologic findings have been described.2 CT scanning is the imaging modality of choice. Most commonly cultured organisms include Streptococci, Haemophilus influenzae, Bacteroides, and less commonly, Staphylococcus aureus.2, 4 Treatment includes empiric broad‐spectrum antibiotics that penetrate the blood‐brain barrier with early surgical drainage of the abscess and debridement of the osteomyelitic bone.4

- ,.Simultaneous intracranial and orbital complications of acute rhinosinusitis in children.Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.2004;68:619–625.

- ,,, et al.Pott's puffy tumor in children.Childs Nerv Syst.2010;26(1):53–60.

- ,,,,.A Pott's Puffy Tumour as a late complication of a frontal sinus reconstruction: case report and literature review.Rhinology.2009;47(4):470–475.

- ,,.An unusual cause of headache: Pott's puffy tumour.Eur J Emerg Med.2007;14(3):170–173.

- ,.Simultaneous intracranial and orbital complications of acute rhinosinusitis in children.Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol.2004;68:619–625.

- ,,, et al.Pott's puffy tumor in children.Childs Nerv Syst.2010;26(1):53–60.

- ,,,,.A Pott's Puffy Tumour as a late complication of a frontal sinus reconstruction: case report and literature review.Rhinology.2009;47(4):470–475.

- ,,.An unusual cause of headache: Pott's puffy tumour.Eur J Emerg Med.2007;14(3):170–173.

Scrofula

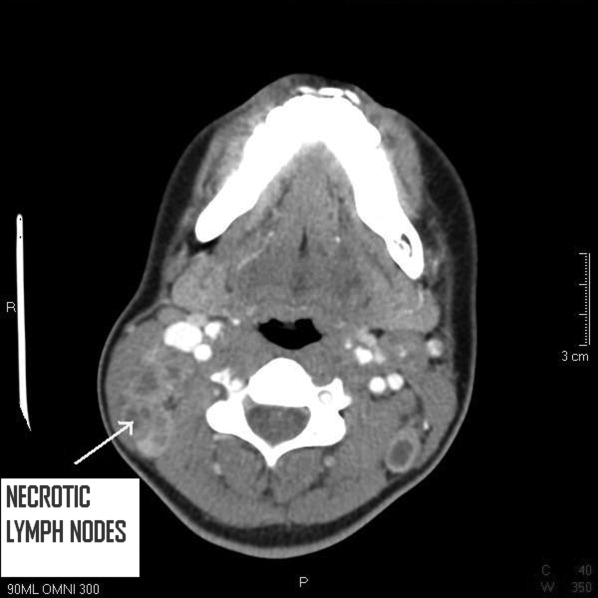

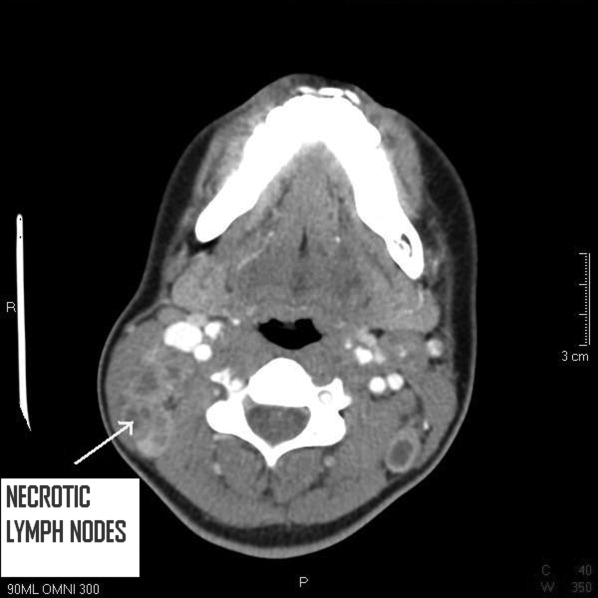

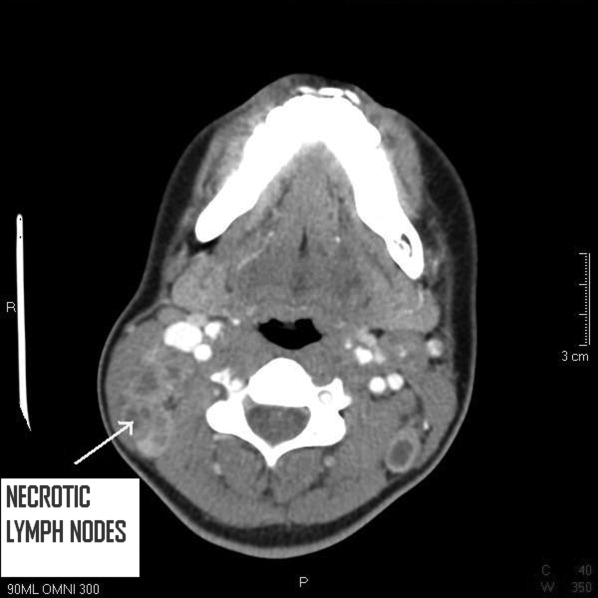

A 25 year‐old hitherto healthy female Asian immigrant presented with gradually worsening painful neck swelling for 5 weeks and a 40‐pound weight loss. Neck examination showed tender, firm, matted and fixed lymph nodes in left and right cervical chains. Contrast computed tomography of the neck confirmed extensive necrotic lymphadenopathy. Excisional lymph node biopsy revealed granulomatous lymphadenitis with microabscesses. Staining for acid‐fast bacilli was positive; tissue culture confirmed the diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. She was started on rifampin 600 mg, isoniazid 300 mg, pyrazinamide 1000 mg, and ethambutol 800 mg; ethambutol was discontinued when the mycobacteria proved susceptible to isoniazid. Pyrazinamide was discontinued after 2 months and isoniazid and rifampin continued to complete 6 months of therapy.0, 0

Tuberculous lymphadenitisscrofula when occurring in the cervical regionis a common cause of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, especially in developing countries. In developed countries, tuberculous lymphadenitis occurs mainly in immigrants but can also arise in travelers to endemic areas and immunodeficient persons.1 Painless lymphadenopathy of the superficial lymph nodes is typical. Fine needle aspiration with microscopy, culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be used as an initial diagnostic tool.2 However, if the results are negative despite high clinical suspicion, excisional biopsy of the lymph node may be necessary. Various nontuberculous mycobacteria also cause adenitis, so definitive speciation is needed to determine optimal therapy.3

Recommended initial treatment for M. tuberculosis includes isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol or streptomycin, based on local resistance patterns. The fourth drug is withdrawn when the isolate is found susceptible to the first 3 drugs; isoniazid and rifampin are used for a total of 6 months of treatment, while pyrazinamide is withdrawn after 2 months.4 Twice‐weekly directly observed therapy (DOT) can be as effective as daily therapy supervised weekly.5 DOT maximizes compliance and reduces treatment failure.

- ,,,,.Cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy: changing clinical pattern and concepts in management.Postgrad Med J.2001;77:185–187.

- ,,, et al.Comparison of inhouse polymerase chain reaction with conventional technique for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in granulomatous lymphadenopathy.J Clin Pathol.2000;53:355–361.

- ,.Extrapulmonary infections associated with nontuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons.Emerg Infect Dis.2009;15(9):1351–1358.

- ,,.Practice guidelines for treatment of tuberculosis.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31(3):633–639.

- ,,, et al.Treatment of lymph node tuberculosis—a randomised clinical trial of two 6‐month regimens.Trop Med Int Health.2005;10(11):1090–1098.

A 25 year‐old hitherto healthy female Asian immigrant presented with gradually worsening painful neck swelling for 5 weeks and a 40‐pound weight loss. Neck examination showed tender, firm, matted and fixed lymph nodes in left and right cervical chains. Contrast computed tomography of the neck confirmed extensive necrotic lymphadenopathy. Excisional lymph node biopsy revealed granulomatous lymphadenitis with microabscesses. Staining for acid‐fast bacilli was positive; tissue culture confirmed the diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. She was started on rifampin 600 mg, isoniazid 300 mg, pyrazinamide 1000 mg, and ethambutol 800 mg; ethambutol was discontinued when the mycobacteria proved susceptible to isoniazid. Pyrazinamide was discontinued after 2 months and isoniazid and rifampin continued to complete 6 months of therapy.0, 0

Tuberculous lymphadenitisscrofula when occurring in the cervical regionis a common cause of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, especially in developing countries. In developed countries, tuberculous lymphadenitis occurs mainly in immigrants but can also arise in travelers to endemic areas and immunodeficient persons.1 Painless lymphadenopathy of the superficial lymph nodes is typical. Fine needle aspiration with microscopy, culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be used as an initial diagnostic tool.2 However, if the results are negative despite high clinical suspicion, excisional biopsy of the lymph node may be necessary. Various nontuberculous mycobacteria also cause adenitis, so definitive speciation is needed to determine optimal therapy.3

Recommended initial treatment for M. tuberculosis includes isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol or streptomycin, based on local resistance patterns. The fourth drug is withdrawn when the isolate is found susceptible to the first 3 drugs; isoniazid and rifampin are used for a total of 6 months of treatment, while pyrazinamide is withdrawn after 2 months.4 Twice‐weekly directly observed therapy (DOT) can be as effective as daily therapy supervised weekly.5 DOT maximizes compliance and reduces treatment failure.

A 25 year‐old hitherto healthy female Asian immigrant presented with gradually worsening painful neck swelling for 5 weeks and a 40‐pound weight loss. Neck examination showed tender, firm, matted and fixed lymph nodes in left and right cervical chains. Contrast computed tomography of the neck confirmed extensive necrotic lymphadenopathy. Excisional lymph node biopsy revealed granulomatous lymphadenitis with microabscesses. Staining for acid‐fast bacilli was positive; tissue culture confirmed the diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. She was started on rifampin 600 mg, isoniazid 300 mg, pyrazinamide 1000 mg, and ethambutol 800 mg; ethambutol was discontinued when the mycobacteria proved susceptible to isoniazid. Pyrazinamide was discontinued after 2 months and isoniazid and rifampin continued to complete 6 months of therapy.0, 0

Tuberculous lymphadenitisscrofula when occurring in the cervical regionis a common cause of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, especially in developing countries. In developed countries, tuberculous lymphadenitis occurs mainly in immigrants but can also arise in travelers to endemic areas and immunodeficient persons.1 Painless lymphadenopathy of the superficial lymph nodes is typical. Fine needle aspiration with microscopy, culture and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be used as an initial diagnostic tool.2 However, if the results are negative despite high clinical suspicion, excisional biopsy of the lymph node may be necessary. Various nontuberculous mycobacteria also cause adenitis, so definitive speciation is needed to determine optimal therapy.3

Recommended initial treatment for M. tuberculosis includes isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol or streptomycin, based on local resistance patterns. The fourth drug is withdrawn when the isolate is found susceptible to the first 3 drugs; isoniazid and rifampin are used for a total of 6 months of treatment, while pyrazinamide is withdrawn after 2 months.4 Twice‐weekly directly observed therapy (DOT) can be as effective as daily therapy supervised weekly.5 DOT maximizes compliance and reduces treatment failure.

- ,,,,.Cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy: changing clinical pattern and concepts in management.Postgrad Med J.2001;77:185–187.

- ,,, et al.Comparison of inhouse polymerase chain reaction with conventional technique for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in granulomatous lymphadenopathy.J Clin Pathol.2000;53:355–361.

- ,.Extrapulmonary infections associated with nontuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons.Emerg Infect Dis.2009;15(9):1351–1358.

- ,,.Practice guidelines for treatment of tuberculosis.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31(3):633–639.

- ,,, et al.Treatment of lymph node tuberculosis—a randomised clinical trial of two 6‐month regimens.Trop Med Int Health.2005;10(11):1090–1098.

- ,,,,.Cervical tuberculous lymphadenopathy: changing clinical pattern and concepts in management.Postgrad Med J.2001;77:185–187.

- ,,, et al.Comparison of inhouse polymerase chain reaction with conventional technique for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA in granulomatous lymphadenopathy.J Clin Pathol.2000;53:355–361.

- ,.Extrapulmonary infections associated with nontuberculous mycobacteria in immunocompetent persons.Emerg Infect Dis.2009;15(9):1351–1358.

- ,,.Practice guidelines for treatment of tuberculosis.Clin Infect Dis.2000;31(3):633–639.

- ,,, et al.Treatment of lymph node tuberculosis—a randomised clinical trial of two 6‐month regimens.Trop Med Int Health.2005;10(11):1090–1098.

Pot Shots

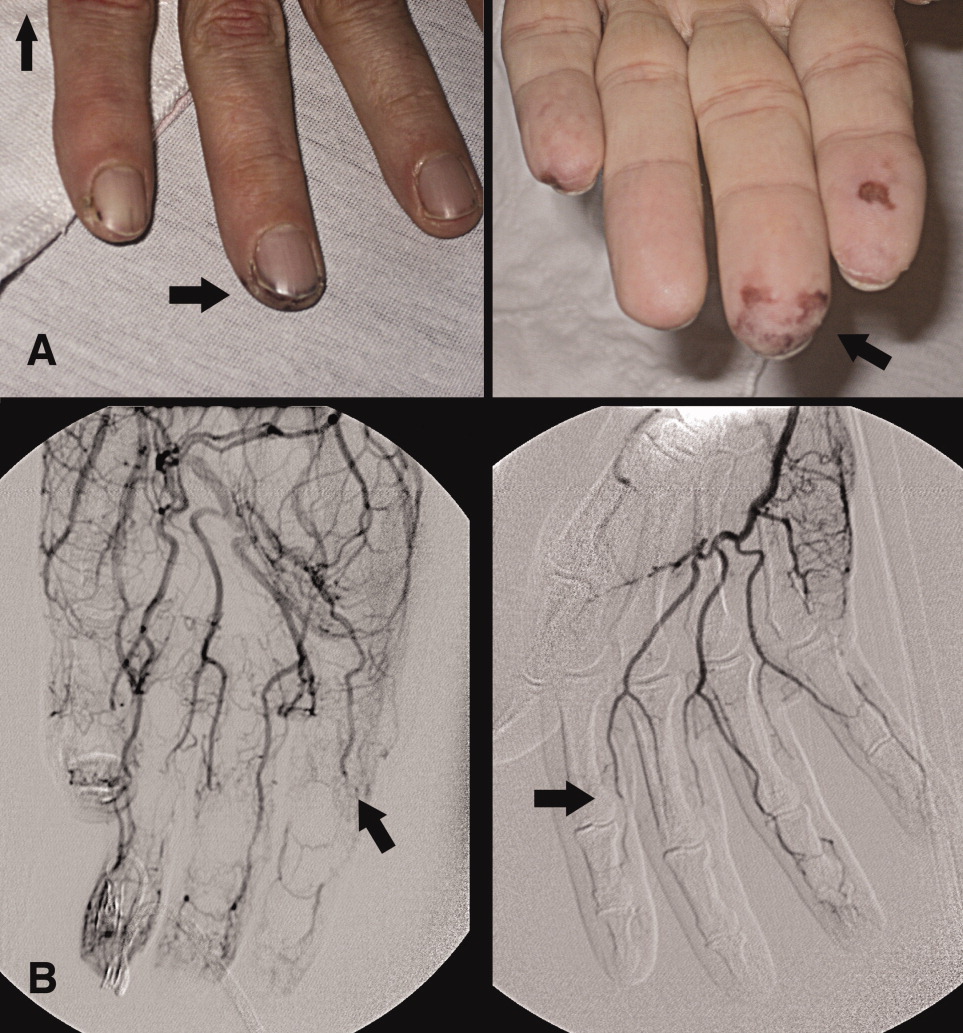

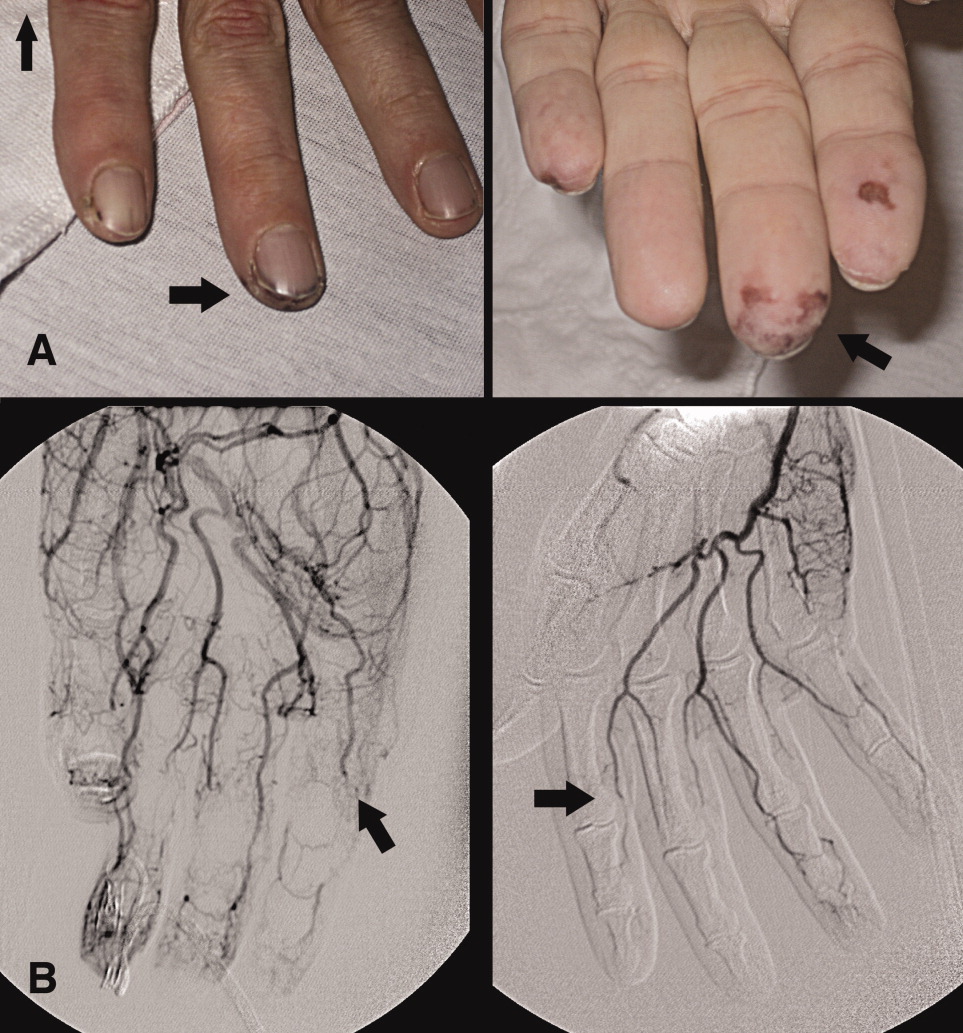

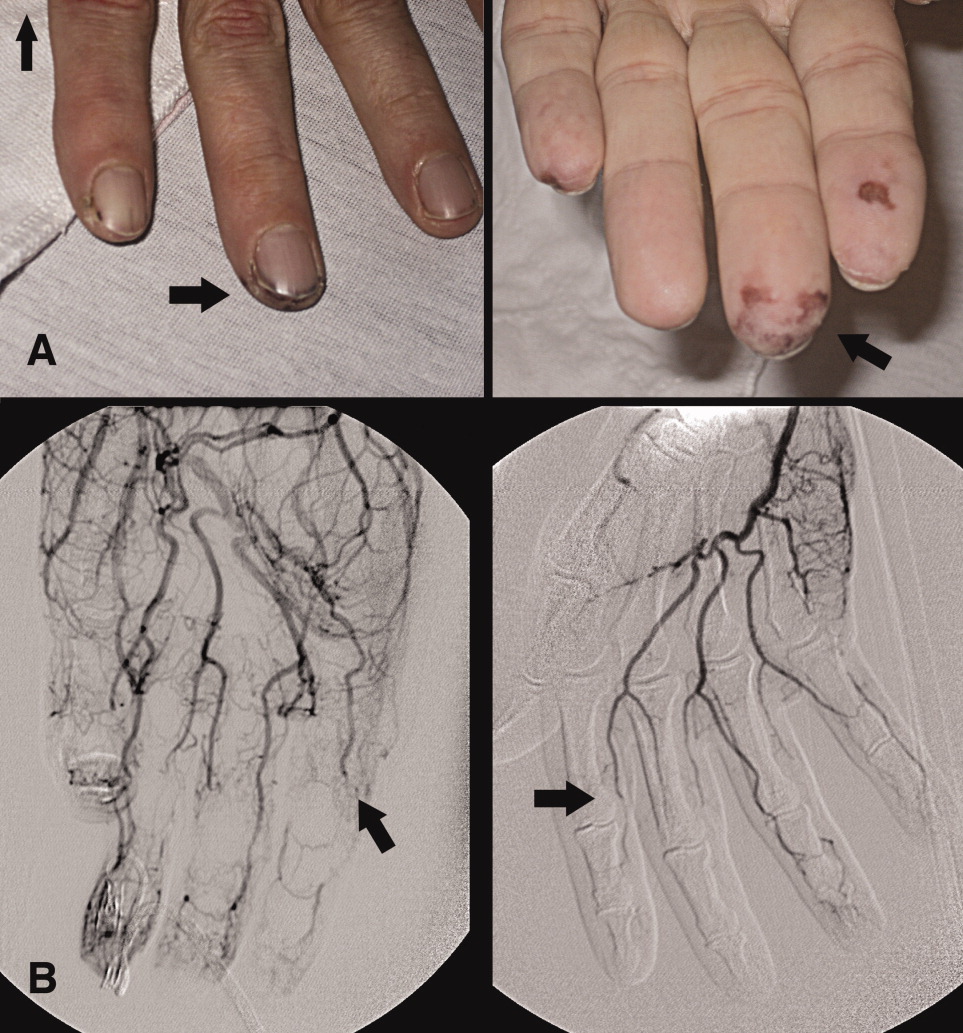

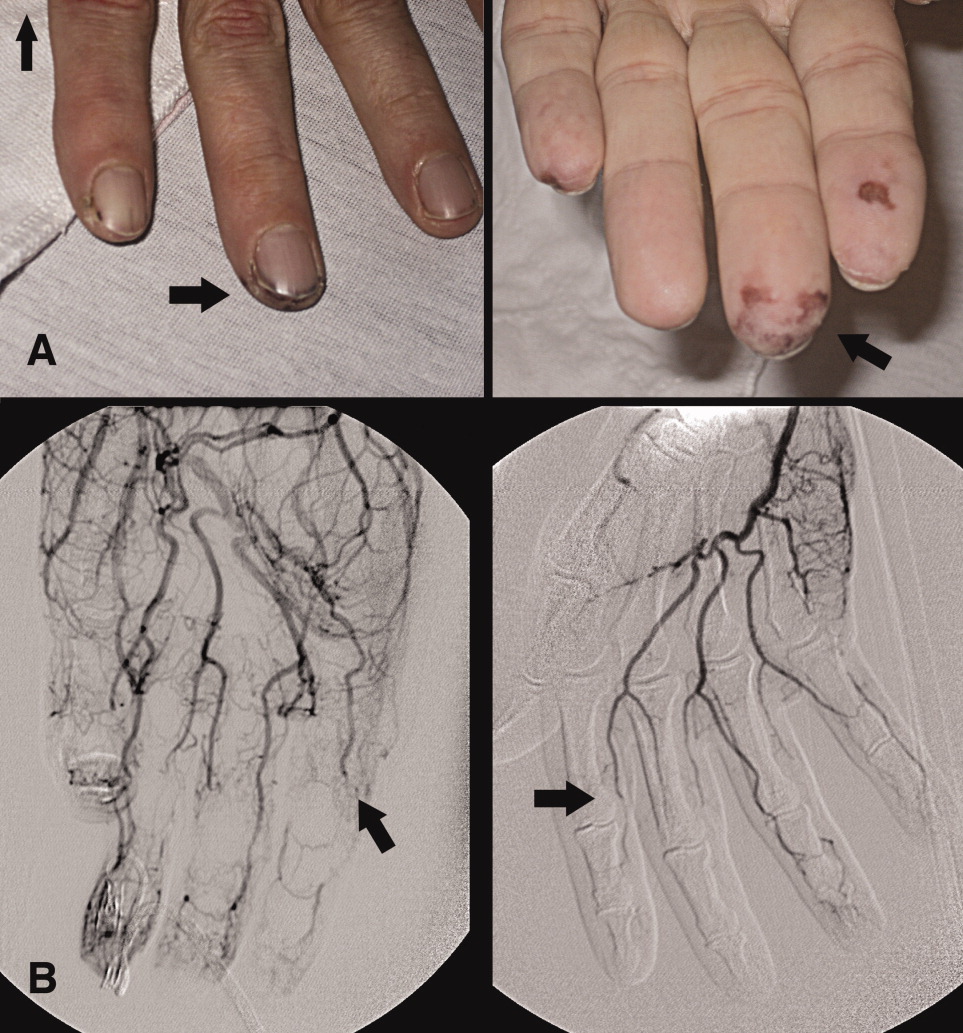

A 46‐year‐old man with a history of heavy marijuana use for 30 years presented to the emergency room with 1 month of progressively worsening distal extremity pain and numbness that had developed into necrosis at the tips of his fingers (Figure 1A, arrows). The patient did not have other systemic symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. An evaluation for hypercoagulable disorders, blood cultures, C‐ANCA, cryoglobulins, Hepatitis C serologies, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies were all negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within normal limits. An arteriogram of the hands showed distal subsegmental obliteration of digital arteries (Figure 1B, arrows), which was consistent with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's Disease). While the patient rarely consumed tobacco, he reported smoking up to 10 marijuana cigarettes daily and a diagnosis of cannabis arteritis was made. The patient was encouraged to discontinue smoking and at follow‐up he had marked improvement in symptoms with abstinence from marijuana.

- ,,.Cannabis arteritis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;58(5 Suppl 1):S65–S67.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis.Br J Dermatol.2005;152(1):166–169.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis: a new case report and a review of literature.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2007;21(3):388–391.

A 46‐year‐old man with a history of heavy marijuana use for 30 years presented to the emergency room with 1 month of progressively worsening distal extremity pain and numbness that had developed into necrosis at the tips of his fingers (Figure 1A, arrows). The patient did not have other systemic symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. An evaluation for hypercoagulable disorders, blood cultures, C‐ANCA, cryoglobulins, Hepatitis C serologies, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies were all negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within normal limits. An arteriogram of the hands showed distal subsegmental obliteration of digital arteries (Figure 1B, arrows), which was consistent with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's Disease). While the patient rarely consumed tobacco, he reported smoking up to 10 marijuana cigarettes daily and a diagnosis of cannabis arteritis was made. The patient was encouraged to discontinue smoking and at follow‐up he had marked improvement in symptoms with abstinence from marijuana.

A 46‐year‐old man with a history of heavy marijuana use for 30 years presented to the emergency room with 1 month of progressively worsening distal extremity pain and numbness that had developed into necrosis at the tips of his fingers (Figure 1A, arrows). The patient did not have other systemic symptoms. Transthoracic echocardiogram was normal. An evaluation for hypercoagulable disorders, blood cultures, C‐ANCA, cryoglobulins, Hepatitis C serologies, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serologies were all negative. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was within normal limits. An arteriogram of the hands showed distal subsegmental obliteration of digital arteries (Figure 1B, arrows), which was consistent with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger's Disease). While the patient rarely consumed tobacco, he reported smoking up to 10 marijuana cigarettes daily and a diagnosis of cannabis arteritis was made. The patient was encouraged to discontinue smoking and at follow‐up he had marked improvement in symptoms with abstinence from marijuana.

- ,,.Cannabis arteritis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;58(5 Suppl 1):S65–S67.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis.Br J Dermatol.2005;152(1):166–169.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis: a new case report and a review of literature.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2007;21(3):388–391.

- ,,.Cannabis arteritis.J Am Acad Dermatol.2008;58(5 Suppl 1):S65–S67.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis.Br J Dermatol.2005;152(1):166–169.

- ,,,,,.Cannabis arteritis: a new case report and a review of literature.J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.2007;21(3):388–391.

A fall to remember

A healthy 44‐year‐old man presented to the emergency room with buttock pain, 2 days after falling from a 4‐foot table onto a cement floor, striking his right buttock. On presentation he was in moderate distress, with heart rate = 130 beats per minute (bpm) and blood pressure = 80/40 mm Hg. There was a 2‐cm area of erythema on the right flank, and mild tenderness of the right buttock. There was no evidence of skin anesthesia or crepitance. Initial laboratory results were notable for creatinine = 1.5 mg/dl, creatine phosphokinase = 11,500 U/L, lactate = 6.1 mmo/L, and white blood cell count = 10 k/UL, with 93% neutrophils. Plain radiography of the hip and spine were negative for fractures and soft tissue gas. Despite receiving multiple doses of narcotic analgesia, the patient continued to complain of severe pain. Within 2 hours of presentation, the right flank erythema extended proximally up the back and distally to the right thigh (Figure 1). The patient was taken to the operating room for surgical exploration and was diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis extending from his posterior neck to the right popliteal fossa (Figures 2 and 3). Intraoperative cultures grew Group A streptococcus, confirming a diagnosis of Type II necrotizing fasciitis. The patient required multiple debridements and subsequent reconstructive procedures. After more than 3 months in the hospital and acute rehabilitation, he returned home.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rapidly progressive infection that spreads along fascial planes, causing necrosis of subcutaneous tissues. Type II necrotizing fasciitis is a monomicrobial infection and occurs in healthy patients, with blunt trauma being a known precipitant. The classic finding in necrotizing fasciitis is pain out of proportion to the physical examination. Additionally, patients will typically present with septic shock and end‐organ dysfunction. Diagnosis requires a strong index of suspicion and surgical exploration is necessary for diagnosis and treatment.

A healthy 44‐year‐old man presented to the emergency room with buttock pain, 2 days after falling from a 4‐foot table onto a cement floor, striking his right buttock. On presentation he was in moderate distress, with heart rate = 130 beats per minute (bpm) and blood pressure = 80/40 mm Hg. There was a 2‐cm area of erythema on the right flank, and mild tenderness of the right buttock. There was no evidence of skin anesthesia or crepitance. Initial laboratory results were notable for creatinine = 1.5 mg/dl, creatine phosphokinase = 11,500 U/L, lactate = 6.1 mmo/L, and white blood cell count = 10 k/UL, with 93% neutrophils. Plain radiography of the hip and spine were negative for fractures and soft tissue gas. Despite receiving multiple doses of narcotic analgesia, the patient continued to complain of severe pain. Within 2 hours of presentation, the right flank erythema extended proximally up the back and distally to the right thigh (Figure 1). The patient was taken to the operating room for surgical exploration and was diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis extending from his posterior neck to the right popliteal fossa (Figures 2 and 3). Intraoperative cultures grew Group A streptococcus, confirming a diagnosis of Type II necrotizing fasciitis. The patient required multiple debridements and subsequent reconstructive procedures. After more than 3 months in the hospital and acute rehabilitation, he returned home.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rapidly progressive infection that spreads along fascial planes, causing necrosis of subcutaneous tissues. Type II necrotizing fasciitis is a monomicrobial infection and occurs in healthy patients, with blunt trauma being a known precipitant. The classic finding in necrotizing fasciitis is pain out of proportion to the physical examination. Additionally, patients will typically present with septic shock and end‐organ dysfunction. Diagnosis requires a strong index of suspicion and surgical exploration is necessary for diagnosis and treatment.

A healthy 44‐year‐old man presented to the emergency room with buttock pain, 2 days after falling from a 4‐foot table onto a cement floor, striking his right buttock. On presentation he was in moderate distress, with heart rate = 130 beats per minute (bpm) and blood pressure = 80/40 mm Hg. There was a 2‐cm area of erythema on the right flank, and mild tenderness of the right buttock. There was no evidence of skin anesthesia or crepitance. Initial laboratory results were notable for creatinine = 1.5 mg/dl, creatine phosphokinase = 11,500 U/L, lactate = 6.1 mmo/L, and white blood cell count = 10 k/UL, with 93% neutrophils. Plain radiography of the hip and spine were negative for fractures and soft tissue gas. Despite receiving multiple doses of narcotic analgesia, the patient continued to complain of severe pain. Within 2 hours of presentation, the right flank erythema extended proximally up the back and distally to the right thigh (Figure 1). The patient was taken to the operating room for surgical exploration and was diagnosed with necrotizing fasciitis extending from his posterior neck to the right popliteal fossa (Figures 2 and 3). Intraoperative cultures grew Group A streptococcus, confirming a diagnosis of Type II necrotizing fasciitis. The patient required multiple debridements and subsequent reconstructive procedures. After more than 3 months in the hospital and acute rehabilitation, he returned home.

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rapidly progressive infection that spreads along fascial planes, causing necrosis of subcutaneous tissues. Type II necrotizing fasciitis is a monomicrobial infection and occurs in healthy patients, with blunt trauma being a known precipitant. The classic finding in necrotizing fasciitis is pain out of proportion to the physical examination. Additionally, patients will typically present with septic shock and end‐organ dysfunction. Diagnosis requires a strong index of suspicion and surgical exploration is necessary for diagnosis and treatment.

Cold case: Bedside diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumonia

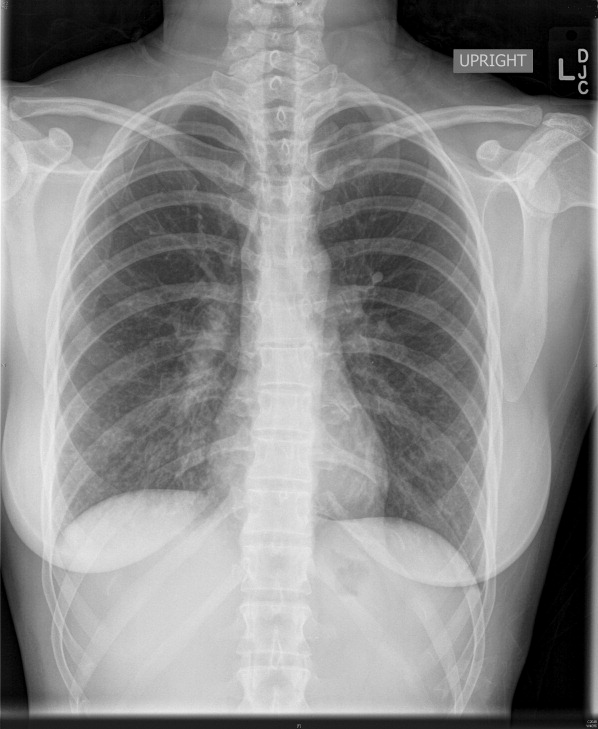

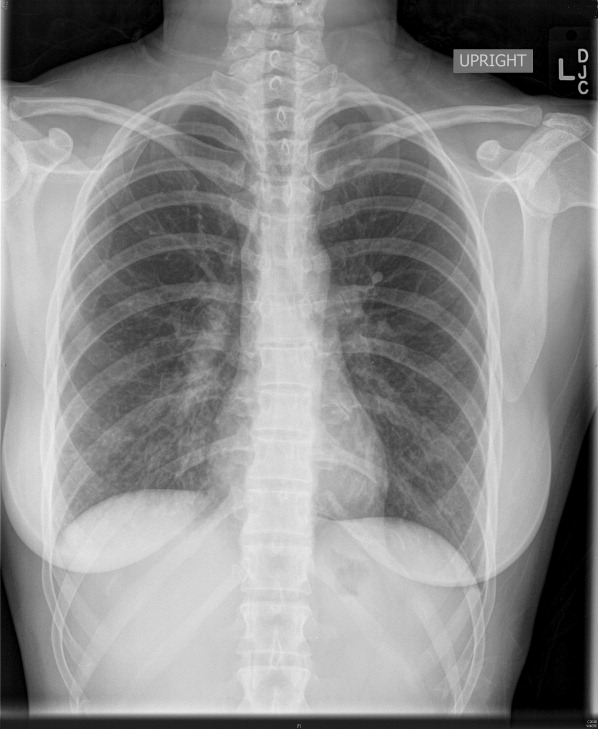

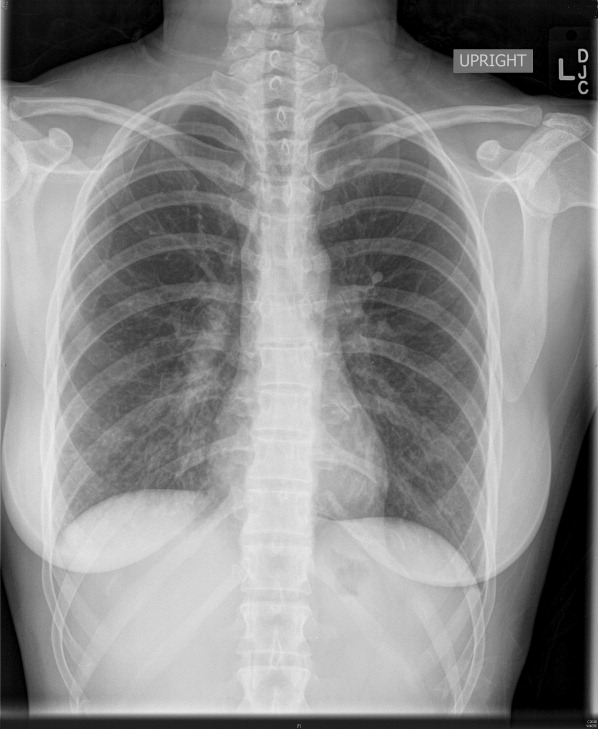

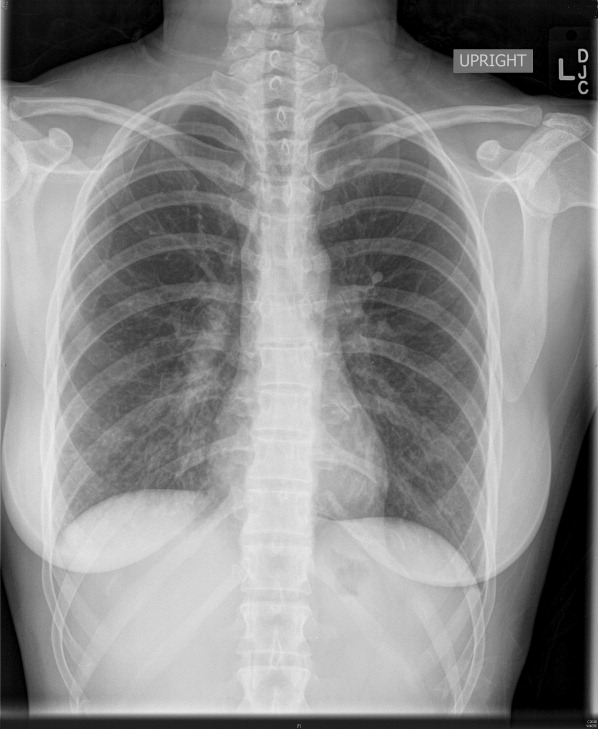

A 35‐year‐old woman with no past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with 3 weeks of worsening cough and shortness of breath. Two weeks prior to her presentation she was seen by her primary care physician for flu‐like symptoms, including myalgias, subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, and malaise. She was told that her symptoms were attributable to influenza, and she was treated supportively; however, her symptoms progressed, and she was referred to the ED for further care. Of note, she reported recent cross‐continental air travel as well as an upper respiratory illness in her young child.

On physical exam she was afebrile with normal vital signs and normal room air oxygen saturation. Her oropharynx was clear, and she had no sinus tenderness, rashes, joint swelling, or palpable lymphadenopathy. She was in moderate respiratory distress and had inspiratory crackles at both lung bases.

Complete blood count, electrolytes, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were within normal limits. A D‐dimer level was slightly elevated. Chest X‐ray showed a mild hazy opacity at the right lung base (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest showed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (Figure 2) but no pulmonary emboli.

A bedside cold agglutinin test, in which the patients blood is drawn into an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube and placed on ice for 30 seconds to 60 seconds, was positive for grains of sand, suggestive of high titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Figure 3). The patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and reported marked symptomatic relief within 2 days.

The utility of culture and serology for acute diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection is limited. Cold agglutinins are antibodiesmost commonly IgMthat cross‐react with red blood cell antigens. They develop in 50% to 75% of patients 1 week to 2 weeks following initial exposure to M. pneumoniae and their incidence decreases with age. Within the clinical context of community‐acquired pneumonia, a bedside cold agglutinin test is specific for M. pneumoniae and provides a rapid and inexpensive means for confirming a suspected diagnosis.

A 35‐year‐old woman with no past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with 3 weeks of worsening cough and shortness of breath. Two weeks prior to her presentation she was seen by her primary care physician for flu‐like symptoms, including myalgias, subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, and malaise. She was told that her symptoms were attributable to influenza, and she was treated supportively; however, her symptoms progressed, and she was referred to the ED for further care. Of note, she reported recent cross‐continental air travel as well as an upper respiratory illness in her young child.

On physical exam she was afebrile with normal vital signs and normal room air oxygen saturation. Her oropharynx was clear, and she had no sinus tenderness, rashes, joint swelling, or palpable lymphadenopathy. She was in moderate respiratory distress and had inspiratory crackles at both lung bases.

Complete blood count, electrolytes, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were within normal limits. A D‐dimer level was slightly elevated. Chest X‐ray showed a mild hazy opacity at the right lung base (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest showed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (Figure 2) but no pulmonary emboli.

A bedside cold agglutinin test, in which the patients blood is drawn into an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube and placed on ice for 30 seconds to 60 seconds, was positive for grains of sand, suggestive of high titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Figure 3). The patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and reported marked symptomatic relief within 2 days.

The utility of culture and serology for acute diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection is limited. Cold agglutinins are antibodiesmost commonly IgMthat cross‐react with red blood cell antigens. They develop in 50% to 75% of patients 1 week to 2 weeks following initial exposure to M. pneumoniae and their incidence decreases with age. Within the clinical context of community‐acquired pneumonia, a bedside cold agglutinin test is specific for M. pneumoniae and provides a rapid and inexpensive means for confirming a suspected diagnosis.

A 35‐year‐old woman with no past medical history presented to the Emergency Department (ED) with 3 weeks of worsening cough and shortness of breath. Two weeks prior to her presentation she was seen by her primary care physician for flu‐like symptoms, including myalgias, subjective fevers, nonproductive cough, and malaise. She was told that her symptoms were attributable to influenza, and she was treated supportively; however, her symptoms progressed, and she was referred to the ED for further care. Of note, she reported recent cross‐continental air travel as well as an upper respiratory illness in her young child.

On physical exam she was afebrile with normal vital signs and normal room air oxygen saturation. Her oropharynx was clear, and she had no sinus tenderness, rashes, joint swelling, or palpable lymphadenopathy. She was in moderate respiratory distress and had inspiratory crackles at both lung bases.

Complete blood count, electrolytes, and electrocardiogram (ECG) were within normal limits. A D‐dimer level was slightly elevated. Chest X‐ray showed a mild hazy opacity at the right lung base (Figure 1). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest showed bilateral lower lobe infiltrates (Figure 2) but no pulmonary emboli.

A bedside cold agglutinin test, in which the patients blood is drawn into an ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) tube and placed on ice for 30 seconds to 60 seconds, was positive for grains of sand, suggestive of high titers of Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin M (IgM) (Figure 3). The patient was discharged with oral antibiotics and reported marked symptomatic relief within 2 days.

The utility of culture and serology for acute diagnosis of M. pneumoniae infection is limited. Cold agglutinins are antibodiesmost commonly IgMthat cross‐react with red blood cell antigens. They develop in 50% to 75% of patients 1 week to 2 weeks following initial exposure to M. pneumoniae and their incidence decreases with age. Within the clinical context of community‐acquired pneumonia, a bedside cold agglutinin test is specific for M. pneumoniae and provides a rapid and inexpensive means for confirming a suspected diagnosis.

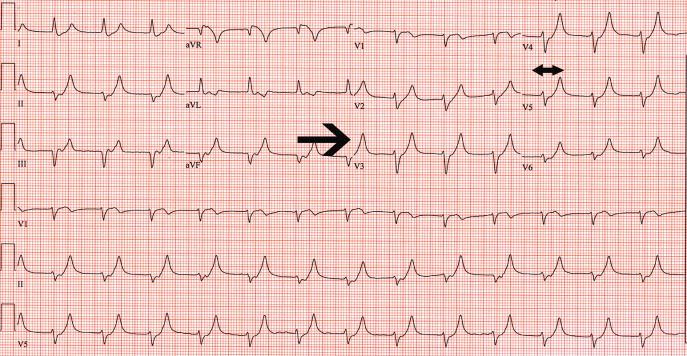

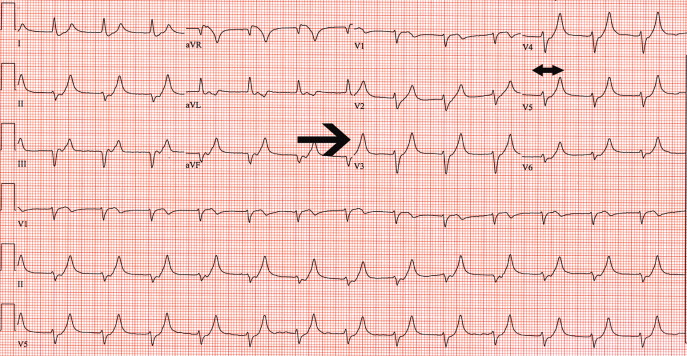

Electrocardiographic changes of severe hyperkalemia

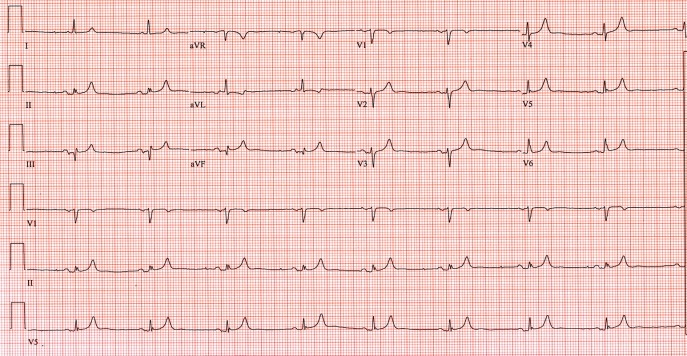

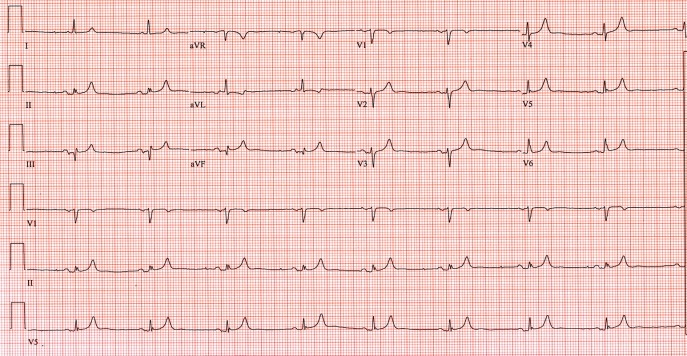

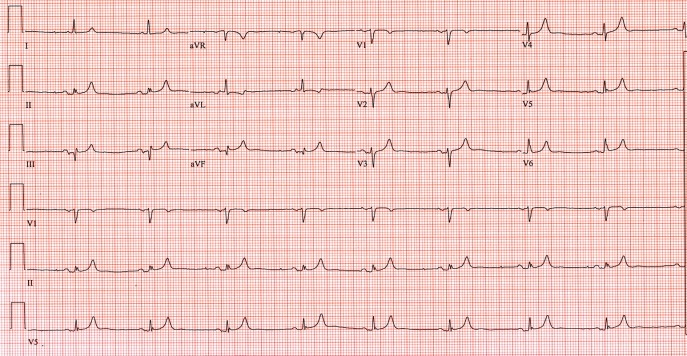

A 62‐year‐old woman with an extensive medical and surgical history presented with complaints of 2 days of weakness. Physical examination demonstrated a lethargic, but arousable woman in no distress. Her lower extremity motor strength was 4/5 bilaterally. The patient's electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated peaked T waves (Figure 1, arrow), absence of P waves, poor R wave progression and QRS interval widening (Figure 1, 2‐headed arrow.) Serum chemistries revealed a potassium level of 10.4 mmol/L and a creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL.

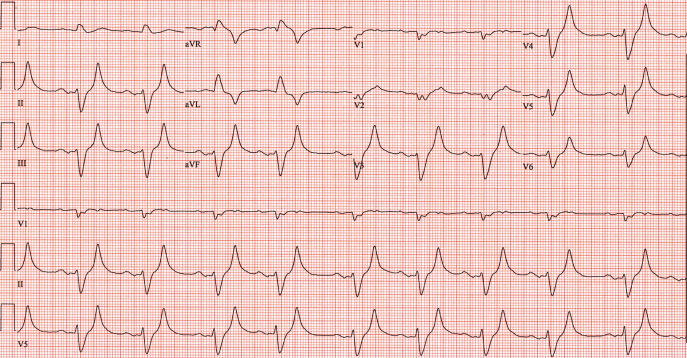

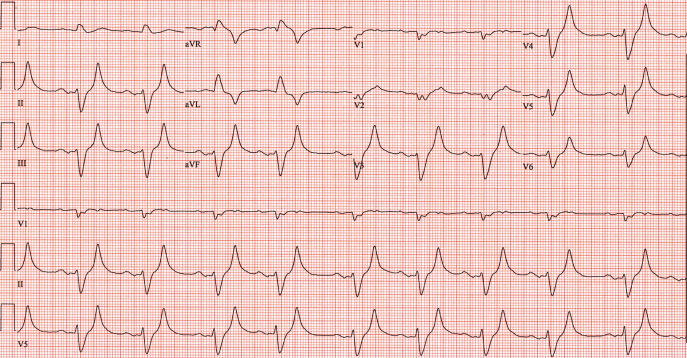

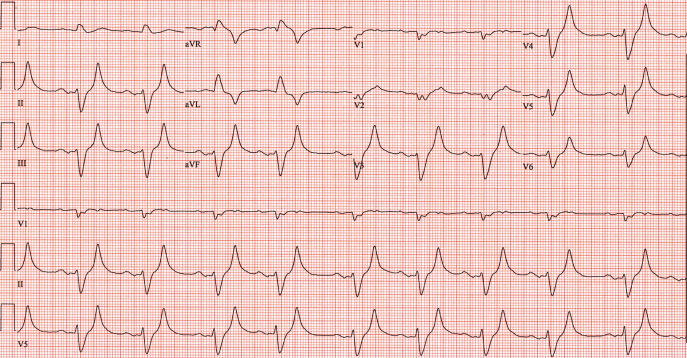

One ampule of D50, 10 units of insulin, 1 ampule of Calcium gluconate and 1 ampule of sodium bicarbonate were given intravenously along with oral Kayexalate. A repeat ECG showed a return of P waves, narrowing of the QRS interval, improved R wave progression and less peaking of the T waves (Figure 2). A repeat potassium level at that time was 9.2 mmol/L.

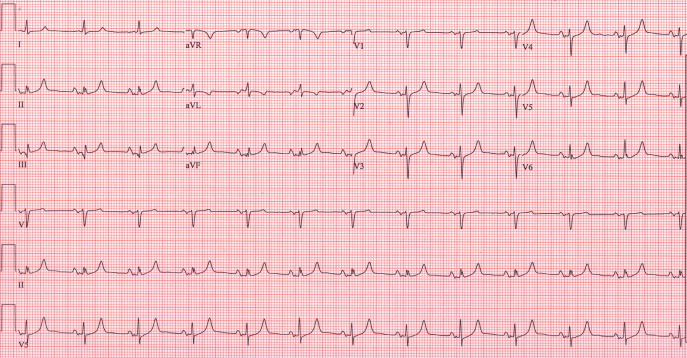

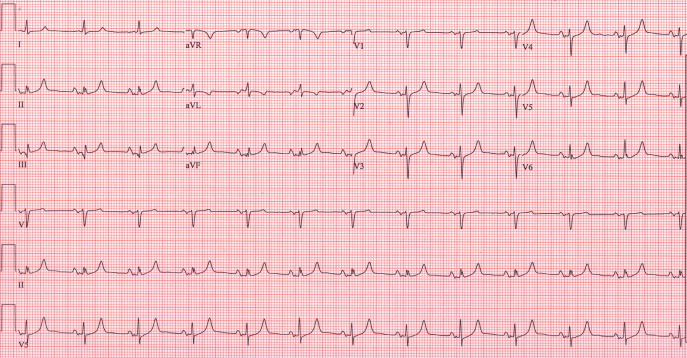

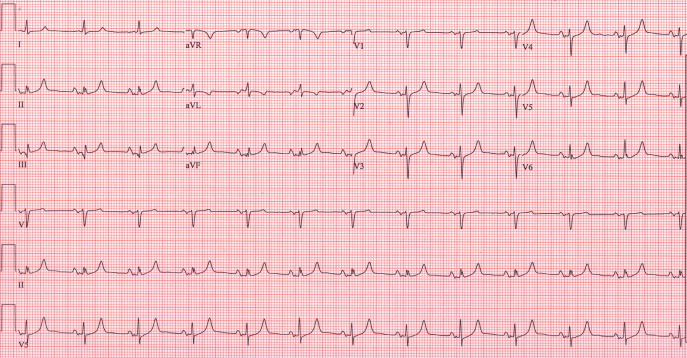

Despite continued therapy to lower the potassium, another ECG showed a return of peaked T waves, a prolonged PR interval and marked widening of the QRS interval to 205 msec; the potassium level was now 10.0 mmol/L (Figure 3).

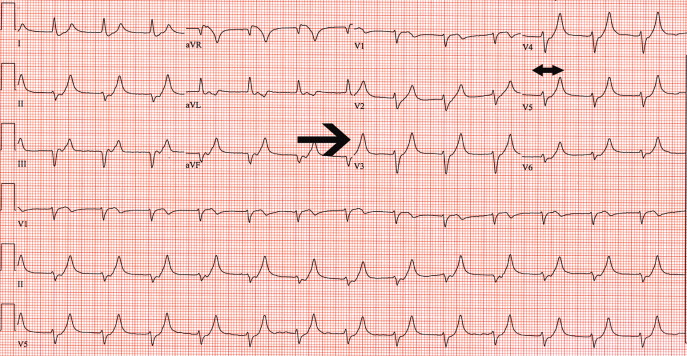

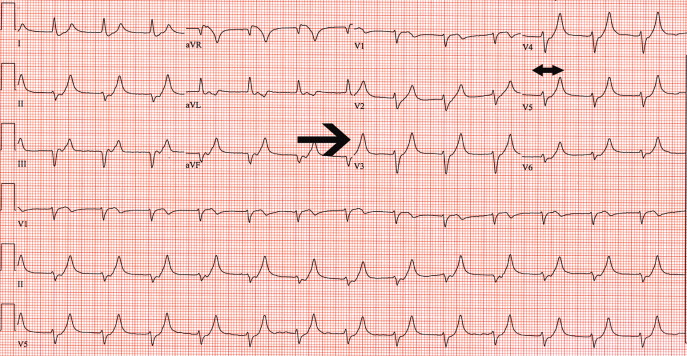

Despite the patient's renal function being normal, she was emergently dialyzed. After a single dialysis, the patient's potassium level remained normal for the remainder of the hospitalization and a follow‐up ECG returned to baseline (Figure 4). No physiologic explanation was found for her hyperkalemia and it was concluded, despite her denials, that she had taken large quantities of exogenous potassium she had available from previous prescriptions.

A 62‐year‐old woman with an extensive medical and surgical history presented with complaints of 2 days of weakness. Physical examination demonstrated a lethargic, but arousable woman in no distress. Her lower extremity motor strength was 4/5 bilaterally. The patient's electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated peaked T waves (Figure 1, arrow), absence of P waves, poor R wave progression and QRS interval widening (Figure 1, 2‐headed arrow.) Serum chemistries revealed a potassium level of 10.4 mmol/L and a creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL.

One ampule of D50, 10 units of insulin, 1 ampule of Calcium gluconate and 1 ampule of sodium bicarbonate were given intravenously along with oral Kayexalate. A repeat ECG showed a return of P waves, narrowing of the QRS interval, improved R wave progression and less peaking of the T waves (Figure 2). A repeat potassium level at that time was 9.2 mmol/L.

Despite continued therapy to lower the potassium, another ECG showed a return of peaked T waves, a prolonged PR interval and marked widening of the QRS interval to 205 msec; the potassium level was now 10.0 mmol/L (Figure 3).

Despite the patient's renal function being normal, she was emergently dialyzed. After a single dialysis, the patient's potassium level remained normal for the remainder of the hospitalization and a follow‐up ECG returned to baseline (Figure 4). No physiologic explanation was found for her hyperkalemia and it was concluded, despite her denials, that she had taken large quantities of exogenous potassium she had available from previous prescriptions.

A 62‐year‐old woman with an extensive medical and surgical history presented with complaints of 2 days of weakness. Physical examination demonstrated a lethargic, but arousable woman in no distress. Her lower extremity motor strength was 4/5 bilaterally. The patient's electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrated peaked T waves (Figure 1, arrow), absence of P waves, poor R wave progression and QRS interval widening (Figure 1, 2‐headed arrow.) Serum chemistries revealed a potassium level of 10.4 mmol/L and a creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL.

One ampule of D50, 10 units of insulin, 1 ampule of Calcium gluconate and 1 ampule of sodium bicarbonate were given intravenously along with oral Kayexalate. A repeat ECG showed a return of P waves, narrowing of the QRS interval, improved R wave progression and less peaking of the T waves (Figure 2). A repeat potassium level at that time was 9.2 mmol/L.

Despite continued therapy to lower the potassium, another ECG showed a return of peaked T waves, a prolonged PR interval and marked widening of the QRS interval to 205 msec; the potassium level was now 10.0 mmol/L (Figure 3).

Despite the patient's renal function being normal, she was emergently dialyzed. After a single dialysis, the patient's potassium level remained normal for the remainder of the hospitalization and a follow‐up ECG returned to baseline (Figure 4). No physiologic explanation was found for her hyperkalemia and it was concluded, despite her denials, that she had taken large quantities of exogenous potassium she had available from previous prescriptions.

Stevens‐Johnson and mycoplasma pneumoniae: A scary duo

A 15‐year‐old male was hospitalized with painful blisters on the lips and ulcers in the oral mucosa that were preceded by upper respiratory infection symptoms for 1 week. He had not been treated with antimicrobials. He subsequently developed conjunctival injection and painful blisters at the urethral meatus and symmetric scattered target lesions in the extremities. Examination demonstrated low‐grade fever, mild conjunctival injection (Figure 2), and oral vesicular lesions affecting the lips (Figure 1) and both the hard and soft palate; he had vesicular lesions affecting the glans penis, a ruptured vesicle at the urethral meatus and target lesions in the arms (Figure 3) and legs (Figure 4). His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. He was started on acyclovir and azithromycin, and symptomatic treatment with oral lidocaine and morphine. Serologies for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Coxsackievirus and cultures for herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM titers were significantly elevated (>4‐fold) and the diagnosis made of Stevens‐Johnson syndrome (SJS) secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. He was able to tolerate oral intake after a 1‐week hospital course.

M. pneumoniae infection can cause mucocutaneous involvement varying from mild mucositis to SJS with significant morbidity and mortality, 1, 2 mostly in the pediatric population. The differential diagnosis includes HSV, Kawasaki, and Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, as well as other viral infections (eg, Coxsackievirus).3 Pharmacologic causesespecially antibiotics, non steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) and anticonvulsantsshould also be considered in the etiology of SJS4 especially in the adult population.

- . Erythema multiforme due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):546–555.

- . Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by severe mucocutaneous lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:268.

- , , , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens‐Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1002–e1005.

- , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with Stevens Johnson syndrome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:414–417.

A 15‐year‐old male was hospitalized with painful blisters on the lips and ulcers in the oral mucosa that were preceded by upper respiratory infection symptoms for 1 week. He had not been treated with antimicrobials. He subsequently developed conjunctival injection and painful blisters at the urethral meatus and symmetric scattered target lesions in the extremities. Examination demonstrated low‐grade fever, mild conjunctival injection (Figure 2), and oral vesicular lesions affecting the lips (Figure 1) and both the hard and soft palate; he had vesicular lesions affecting the glans penis, a ruptured vesicle at the urethral meatus and target lesions in the arms (Figure 3) and legs (Figure 4). His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. He was started on acyclovir and azithromycin, and symptomatic treatment with oral lidocaine and morphine. Serologies for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Coxsackievirus and cultures for herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM titers were significantly elevated (>4‐fold) and the diagnosis made of Stevens‐Johnson syndrome (SJS) secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. He was able to tolerate oral intake after a 1‐week hospital course.

M. pneumoniae infection can cause mucocutaneous involvement varying from mild mucositis to SJS with significant morbidity and mortality, 1, 2 mostly in the pediatric population. The differential diagnosis includes HSV, Kawasaki, and Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, as well as other viral infections (eg, Coxsackievirus).3 Pharmacologic causesespecially antibiotics, non steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) and anticonvulsantsshould also be considered in the etiology of SJS4 especially in the adult population.

A 15‐year‐old male was hospitalized with painful blisters on the lips and ulcers in the oral mucosa that were preceded by upper respiratory infection symptoms for 1 week. He had not been treated with antimicrobials. He subsequently developed conjunctival injection and painful blisters at the urethral meatus and symmetric scattered target lesions in the extremities. Examination demonstrated low‐grade fever, mild conjunctival injection (Figure 2), and oral vesicular lesions affecting the lips (Figure 1) and both the hard and soft palate; he had vesicular lesions affecting the glans penis, a ruptured vesicle at the urethral meatus and target lesions in the arms (Figure 3) and legs (Figure 4). His cardiopulmonary exam was normal. He was started on acyclovir and azithromycin, and symptomatic treatment with oral lidocaine and morphine. Serologies for Epstein‐Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Coxsackievirus and cultures for herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgM titers were significantly elevated (>4‐fold) and the diagnosis made of Stevens‐Johnson syndrome (SJS) secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. He was able to tolerate oral intake after a 1‐week hospital course.

M. pneumoniae infection can cause mucocutaneous involvement varying from mild mucositis to SJS with significant morbidity and mortality, 1, 2 mostly in the pediatric population. The differential diagnosis includes HSV, Kawasaki, and Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, as well as other viral infections (eg, Coxsackievirus).3 Pharmacologic causesespecially antibiotics, non steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) and anticonvulsantsshould also be considered in the etiology of SJS4 especially in the adult population.

- . Erythema multiforme due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):546–555.

- . Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by severe mucocutaneous lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:268.

- , , , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens‐Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1002–e1005.

- , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with Stevens Johnson syndrome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:414–417.

- . Erythema multiforme due to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in two children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23(6):546–555.

- . Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection complicated by severe mucocutaneous lesions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:268.

- , , , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae and atypical Stevens‐Johnson syndrome: a case series. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1002–e1005.

- , , , . Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with Stevens Johnson syndrome. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35:414–417.