User login

Roth Spots—More than Meets the Eye

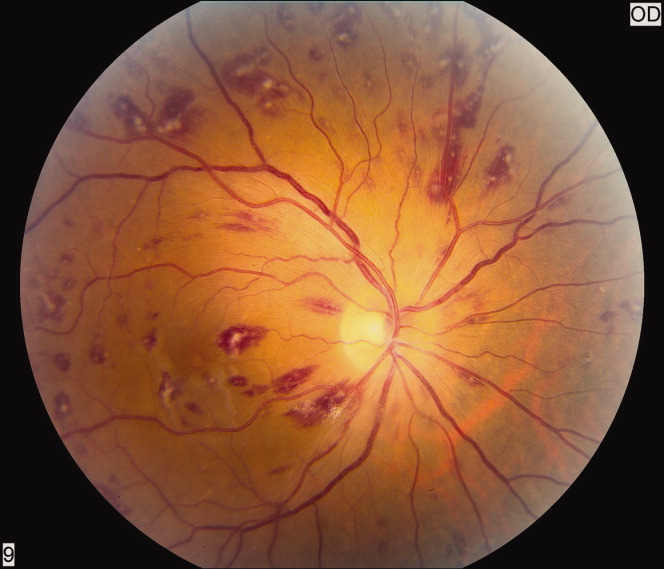

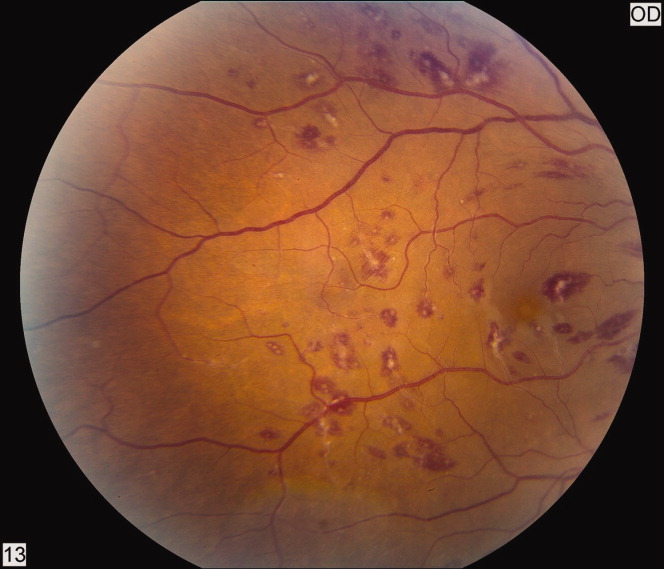

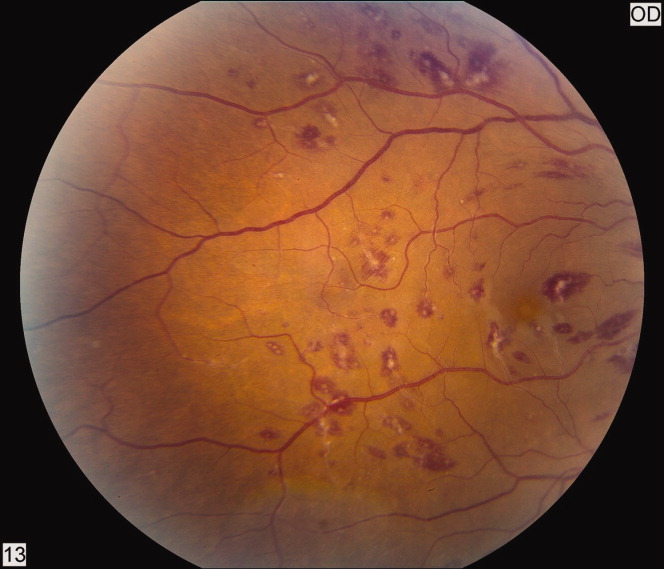

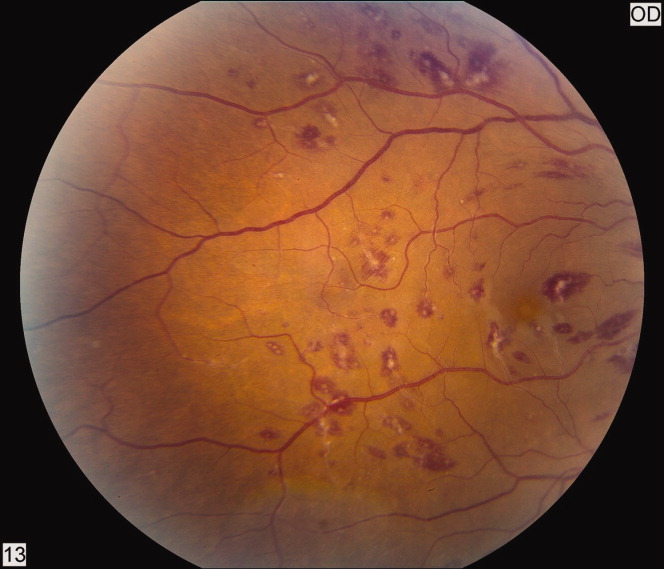

A 50‐year‐old female patient with a past medical history of Sjogren's syndrome and polymyositis presented with fever, rash, swelling, and pain in her extremities. Skin biopsy confirmed vasculitis. She was treated with steroids and azathioprine. However, she developed sudden‐onset central visual blurring in her right eye on the fifth day of hospitalization. Fundoscopic exam showed multiple central white‐centered retinal hemorrhages (Roth spots, Figures 1, 2) and vascular sheathing, consistent with retinal vasculitis. Blood cultures were negative. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms were normal. She was treated with high‐dose intravenous steroids and cyclophosphamide, with visual improvement and a marked reduction in the number of Roth spots.

Roth spots 1 are nonspecific intraretinal hemorrhagic lesions with a white center due to fibrin deposition. Although historically associated with infective endocarditis, they can also occur in other systemic diseases such as connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, leukemia, diabetes, hypertension, anemia, trauma, as well as disseminated bacterial and fungal infections.

- , , .White centered hemorrhages: their significance.Ophthalmology.1980;87:66–69.

A 50‐year‐old female patient with a past medical history of Sjogren's syndrome and polymyositis presented with fever, rash, swelling, and pain in her extremities. Skin biopsy confirmed vasculitis. She was treated with steroids and azathioprine. However, she developed sudden‐onset central visual blurring in her right eye on the fifth day of hospitalization. Fundoscopic exam showed multiple central white‐centered retinal hemorrhages (Roth spots, Figures 1, 2) and vascular sheathing, consistent with retinal vasculitis. Blood cultures were negative. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms were normal. She was treated with high‐dose intravenous steroids and cyclophosphamide, with visual improvement and a marked reduction in the number of Roth spots.

Roth spots 1 are nonspecific intraretinal hemorrhagic lesions with a white center due to fibrin deposition. Although historically associated with infective endocarditis, they can also occur in other systemic diseases such as connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, leukemia, diabetes, hypertension, anemia, trauma, as well as disseminated bacterial and fungal infections.

A 50‐year‐old female patient with a past medical history of Sjogren's syndrome and polymyositis presented with fever, rash, swelling, and pain in her extremities. Skin biopsy confirmed vasculitis. She was treated with steroids and azathioprine. However, she developed sudden‐onset central visual blurring in her right eye on the fifth day of hospitalization. Fundoscopic exam showed multiple central white‐centered retinal hemorrhages (Roth spots, Figures 1, 2) and vascular sheathing, consistent with retinal vasculitis. Blood cultures were negative. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms were normal. She was treated with high‐dose intravenous steroids and cyclophosphamide, with visual improvement and a marked reduction in the number of Roth spots.

Roth spots 1 are nonspecific intraretinal hemorrhagic lesions with a white center due to fibrin deposition. Although historically associated with infective endocarditis, they can also occur in other systemic diseases such as connective tissue disorders, vasculitis, leukemia, diabetes, hypertension, anemia, trauma, as well as disseminated bacterial and fungal infections.

- , , .White centered hemorrhages: their significance.Ophthalmology.1980;87:66–69.

- , , .White centered hemorrhages: their significance.Ophthalmology.1980;87:66–69.

“Better Late than Never”

A 59‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with the acute onset of right‐sided abdominal and flank pain. The pain had begun the previous night, was constant and progressively worsening, and radiated to his right groin. He denied fever, nausea, emesis, or change in his bowel habits, but he did notice mild right lower quadrant discomfort with micturition. Upon further questioning, he also complained of mild dyspnea on climbing stairs and an unspecified recent weight loss.

The most common cause of acute severe right‐sided flank and abdominal pain radiating to the groin and associated with dysuria in a middle‐aged man is ureteral colic. Other etiologies important to consider include retrocecal appendicitis, pyelonephritis, and, rarely, a dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. This patient's seemingly recent onset exertional dyspnea and weight loss do not neatly fit any of the above, however.

His past medical history was significant for diabetes mellitus and pemphigus vulgaris diagnosed 7 months previously. He had been treated with prednisone, and the dose decreased from 100 to 60 mg daily, 1 month previously, due to poor glycemic control as well as steroid‐induced neuropathy and myopathy. His other medications included naproxen sodium and ibuprofen for back pain, azathioprine, insulin, pioglitazone, and glimiperide. He had no past surgical history. He had lived in the United States since his emigration from Thailand in 1971. His last trip to Thailand was 5 years previously. He was a taxi cab driver. He had a ten‐pack year history of tobacco use, but had quit 20 years prior. He denied history of alcohol or intravenous drug use.

Pemphigus vulgaris is unlikely to be directly related to this patient's presentation, but in light of his poorly controlled diabetes, his azathioprine use, and particularly his high‐dose corticosteroids, he is certainly immunocompromised. Accordingly, a disseminated infection, either newly acquired or reactivated, merits consideration. His history of residence in, and subsequent travel to, Southeast Asia raises the possibility of several diseases, each of which may be protean in their manifestations; these include tuberculosis, melioidosis, and penicilliosis (infection with Penicillium marneffei). The first two may reactivate long after initial exposure, particularly with insults to the immune system. The same is probably true of penicilliosis, although I am not certain of this. On a slightly less exotic note, domestically acquired infection with histoplasmosis or other endemic fungi is possible.

On examination he was afebrile, had a pulse of 130 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 65/46 mmHg. His oxygen saturation was 92%. He appeared markedly cushingoid, and had mild pallor and generalized weakness. Cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. His abdominal exam was notable for distention and hypoactive bowel sounds, with tenderness and firmness to palpation on the right side. Peripheral pulses were normal. Examination of the skin demonstrated ecchymoses over the bilateral forearms, and several healed pemphigus lesions on the abdomen and upper extremities.

The patient's severely deranged hemodynamic parameters indicate either current or impending shock, and resuscitative measures should proceed in tandem with diagnostic efforts. The cause of his shock seems most likely to be either hypovolemic (abdominal wall or intra‐abdominal hemorrhage, or conceivably massive third spacing from an intra‐abdominal catastrophe), or distributive (sepsis, or acute adrenal insufficiency if he has missed recent steroid doses). His ecchymoses may simply reflect chronic glucocorticoid use, but also raise suspicion for a coagulopathy. Provided the patient can be stabilized to allow this, I would urgently obtain a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

Initial laboratory studies demonstrated a hemoglobin of 9.1 g/dL, white blood cell count 8000/L with 33% bands, 48% segmented neutrophils, 18% lymphocytes, and 0.7% eosinophils, platelet count 356,000/L, sodium 128 mmol/L, BUN 52 mg/dL, creatinine 2.3 mg/dL, and glucose of 232 mg/dL. Coagulation studies were normal, and lactic acid was 1.8 mmol/L (normal range, 0.7‐2.1). Fibrinogen was normal at 591 and LDH was mildly elevated at 654 (normal range, 313‐618 U/L). Total protein and albumin were 3.6 and 1.9 g/dL, respectively. Total bilirubin was 0.6 mg/dL. Random serum cortisol was 20.2 g/dL. Liver enzymes, amylase, lipase, iron stores, B12, folate, and stool for occult blood were normal. Initial cardiac biomarkers were negative, but subsequent troponin‐I was 3.81 ng/mL (elevated, >1.00). Urinalysis showed 0‐4 white blood cells per high powered field.

The laboratory studies provide a variety of useful, albeit nonspecific, information. The high percentage of band forms on white blood cell differential further raises concern for an infectious process, although severe noninfectious stress can also cause this. While we do not know whether the patient's renal failure is acute, I suspect that it is, and may result from a variety of insults including sepsis, hypotension, and volume depletion. His moderately elevated troponin‐I likely reflects supplydemand mismatch or sepsis. I would like to see an electrocardiogram, and I remain very interested in obtaining abdominal imaging.

Chest radiography showed pulmonary vascular congestion without evidence of pneumothorax. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed retroperitoneal fluid bilaterally (Figure 1). This was described as suspicious for ascites versus hemorrhage, but no obvious source of bleeding was identified. There was also a small amount of right perinephric fluid, but no evidence of a renal mass. The abdominal aorta was normal; there was no lymphadenopathy.

The CT image appears to speak against simple ascites, and seems most consistent with either blood or an infectious process. Consequently, the loculated right retroperitoneal collection should be aspirated, and fluid sent for fungal, acid‐fast, and modified acid‐fast (i.e., for Nocardia) stains and culture, in addition to Gram stain and routine aerobic and anaerobic cultures.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Stress‐dose steroids were administered, and he improved after resuscitation with fluid and blood. His renal function normalized. Urine and blood cultures returned negative. His hematocrit and multiple repeat CT scans of the abdomen remained stable. A retroperitoneal hemorrhage was diagnosed, and surgical intervention was deemed unnecessary. Both adenosine thallium stress test and echocardiogram were normal. He was continued on 60 mg prednisone daily and discharged home with outpatient follow‐up.

This degree of improvement with volume expansion (and steroids) suggests the patient was markedly volume depleted upon presentation. Although a formal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test was apparently not performed, the random cortisol level suggests adrenal insufficiency was unlikely to have been primarily responsible. While retroperitoneal hemorrhage is possible, the loculated appearance of the collection suggests infection is more likely.

Three weeks later, he was readmitted with recurrent right‐sided abdominal and flank pain. His temperature was 101.3F, and he was tachycardic and hypotensive. His examination was similar to that at the time of his previous presentation. Laboratory data revealed white blood cell count of 13,100/L with 43% bands, hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dL, glucose of 343 mg/dL, bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, normal anion gap and renal function, and lactic acid of 4.5 mmol/L. Liver function tests were normal except for an albumin of 3.0 g/dL. CT scan of the abdomen revealed loculated retroperitoneal fluid collections, increased in size since the prior scan.

The patient is once again evidencing at least early shock, manifested in his deranged hemodynamics and elevated lactate level. I remain puzzled by the fact that he appeared to respond to fluids alone at the time of his initial hospital stay, unless adrenal insufficiency played a greater role than I suspected. Of note, acute adrenal insufficiency could explain much of the current picture, including fever, and bland (uninfected) hematomas are an underappreciated cause of both fever and leukocytosis. Having said this, I remain concerned that his retroperitoneal fluid collections represent abscesses. The most accessible of these should be sampled.

Aspiration of the retroperitoneal fluid yielded purulent material which grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. The cultures were negative for mycobacteria and fungus. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Drains were placed, and he was followed as an outpatient. His fever and leukocytosis subsided, and he completed a 6‐week course of trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. CT imaging confirmed complete evacuation of the fluid.

Retroperitoneal abscesses frequently present in smoldering fashion, although patients may be quite ill by the time of presentation. Most of these are secondary, i.e., they arise from another abnormality in the retroperitoneum. Most commonly this is in the large bowel, kidney, pancreas, or spine. I would carefully scour his follow‐up imaging for additional clues and, if unrevealing, proceed to colonoscopy.

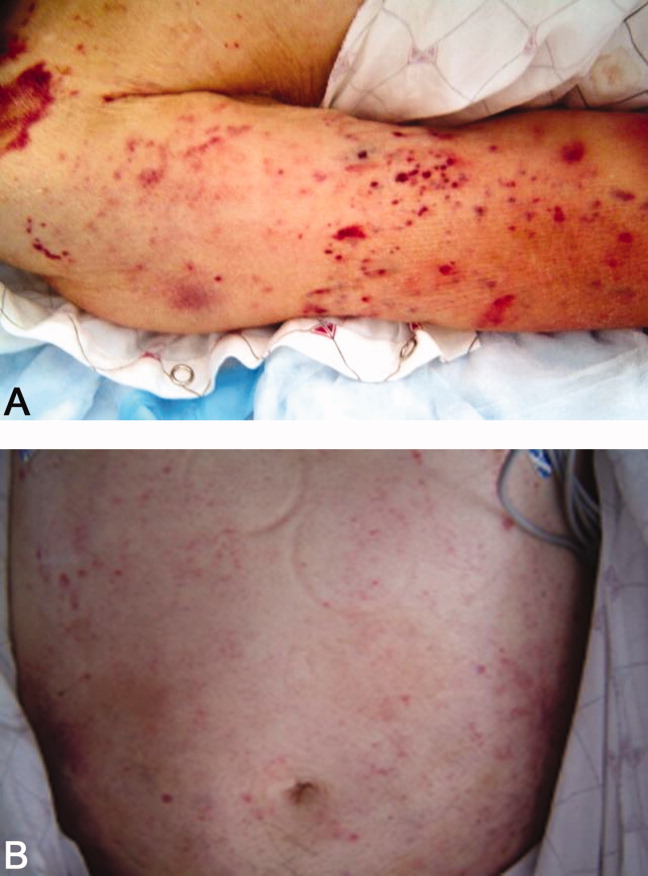

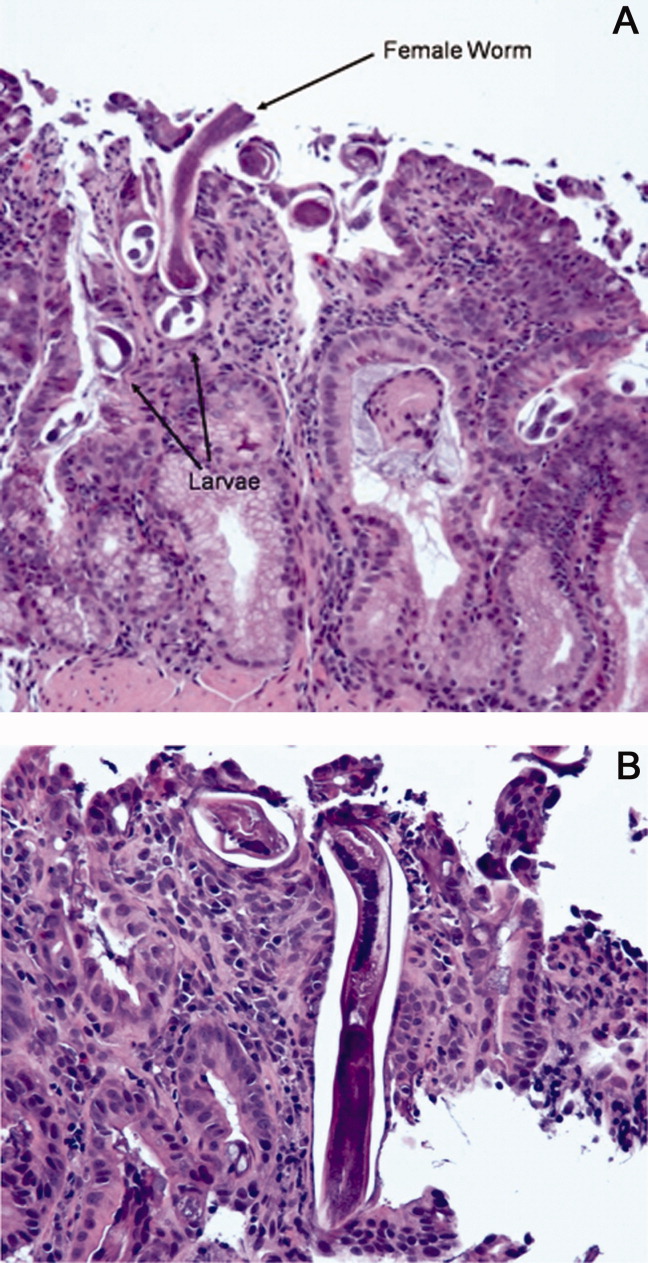

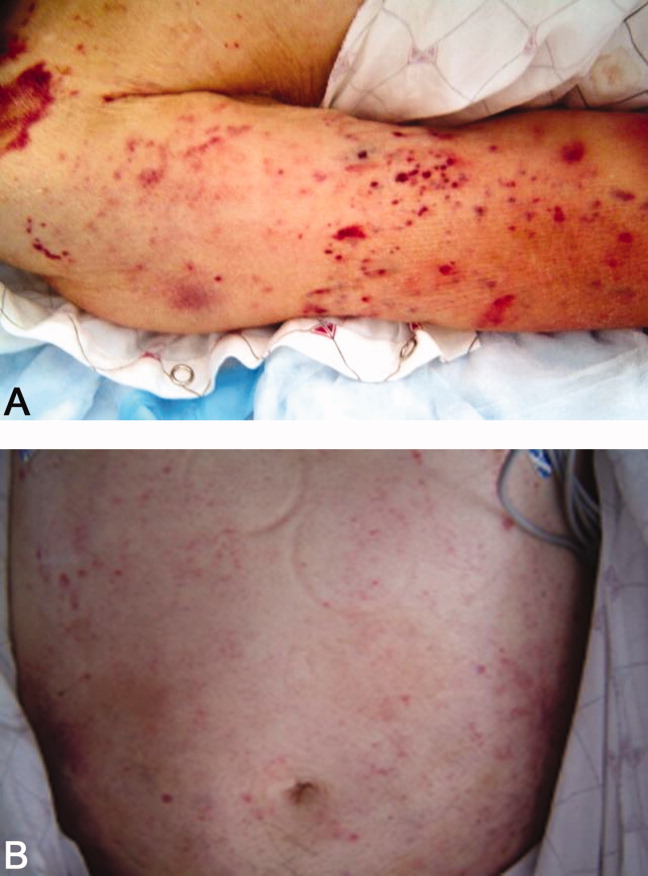

He returned 1 month after drain removal, with 2‐3 days of nausea and abdominal pain. His abdomen was moderately distended but nontender, and multiple persistent petechial and purpuric lesions were present on the upper back, chest, torso, and arms. Abdominal CT scan revealed small bowel obstruction and a collection of fluid in the left paracolic gutter extending into the left retrorenal space.

The patient does not appear to have obvious risk factors for developing a small bowel obstruction. No mention is made of the presence or absence of a transition point on the CT scan, and this should be ascertained. His left‐sided abdominal fluid collection is probably infectious in nature, and I continue to be suspicious of a large bowel (or distal small bowel) source, via either gut perforation or bacterial translocation. The collection needs to be percutaneously drained for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons, and broadly cultured. Finally, we need to account for the described dermatologic manifestations. The purpuric/petechial lesions sound vasculitic rather than thrombocytopenic in origin based on location; conversely, they may simply reflect a corticosteroid‐related adverse effect. I would like to know whether the purpura was palpable, and to repeat a complete blood count with peripheral smear.

Laboratory data showed hemoglobin of 9.3 g/dL, a platelet count of 444,000/L, and normal coagulation studies. The purpura was nonpalpable (Figure 2). The patient had a nasogastric tube placed for decompression, with bilious drainage. His left retroperitoneal fluid was drained, with cultures yielding Enterococcus faecalis and Enterobacter cloacae. The patient was treated with a course of broad‐spectrum antibiotics. His obstruction improved and the retroperitoneal collection resolved on follow‐up imaging. However, 2 days later, he had recurrent pain; abdominal CT showed a recurrence of small bowel obstruction with an unequivocal transition point in the distal jejunum. A small fluid collection was noted in the left retroperitoneum with a trace of gas in it. He improved with nasogastric suction, his prednisone was tapered to 30 mg daily, and he was discharged home.

The isolation of both Enterococcus and Enterobacter species from his fluid collection, along with the previous isolation of Klebsiella, strongly suggest a bowel source for his recurrent abscesses. Based on this CT report, the patient has clear evidence of at least partial small bowel obstruction. He lacks a history of prior abdominal surgery or other more typical reasons for obstruction caused by extrinsic compression, such as hernia, although it is possible his recurrent abdominal infections may have led to obstruction due to scarring and adhesions. An intraluminal cause of obstruction also needs to be considered, with causes including malignancy (lymphoma, carcinoid, and adenocarcinoma), Crohn's disease, and infections including tuberculosis as well as parasites such as Taenia and Strongyloides. While the purpura is concerning, given the nonpalpable character along with a normal platelet count and coagulation studies, it may be reasonable to provisionally attribute it to high‐dose corticosteroid use.

He was admitted a fourth time a week after being discharged, with nausea, generalized weakness, and weight loss. At presentation, he had a blood pressure of 95/65 mmHg. His white blood cell count was 5,900/L, with 79% neutrophils and 20% bands. An AM cortisol was 18.8 /dL. He was thought to have adrenal insufficiency from steroid withdrawal, was treated with intravenous fluids and steroids, and discharged on a higher dose of prednisone at 60 mg daily. One week later, he again returned to the hospital with watery diarrhea, emesis, and generalized weakness. His blood pressure was 82/50 mmHg, and his abdomen appeared benign. He also had an erythematous rash over his mid‐abdomen. Laboratory data was significant for a sodium of 127 mmol/L, potassium of 3.0 mmol/L, chloride of 98 mmol/L, bicarbonate of 26 mmol/L, glucose of 40 mg/dL, lactate of 14 mmol/L, and albumin of 1.0 g/dL. Stool assay for Clostridium difficile was negative. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed small bilateral pleural effusions and small bowel fluid consistent with gastroenteritis, but without signs of obstruction. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed bile backwash into the stomach, as well as inflammatory changes in the proximal and mid‐stomach, and inflammatory reaction and edema in the proximal duodenum. Colonoscopy showed normal appearing ileum and colon.

The patient's latest laboratory values appear to reflect his chronic illness and superimposed diarrhea. I am perplexed by his markedly elevated serum lactate value in association with a normal bicarbonate and low anion gap, and would repeat the lactate level to ensure this is not spurious. His hypoglycemia probably reflects a failure to adjust or discontinue his diabetic medications, although both hypoglycemia and type B lactic acidosis are occasionally manifestations of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The normal colonoscopy findings are helpful in exonerating the colon, provided the preparation was adequate. Presumably, the abnormal areas of the stomach and duodenum were biopsied; I remain suspicious that the answer may lie in the jejunum.

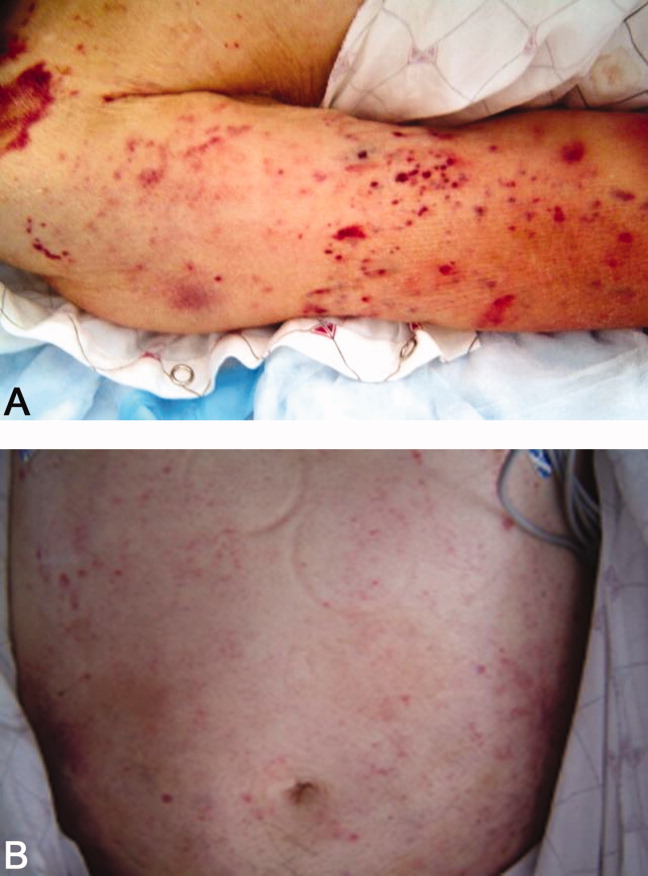

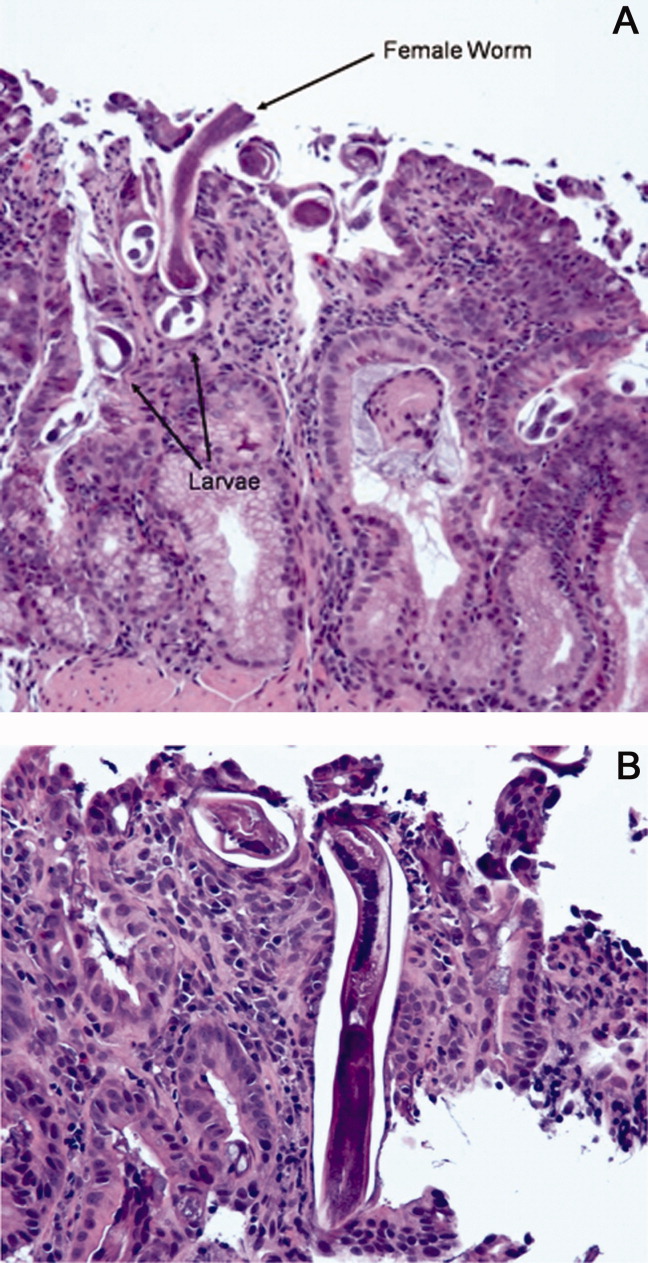

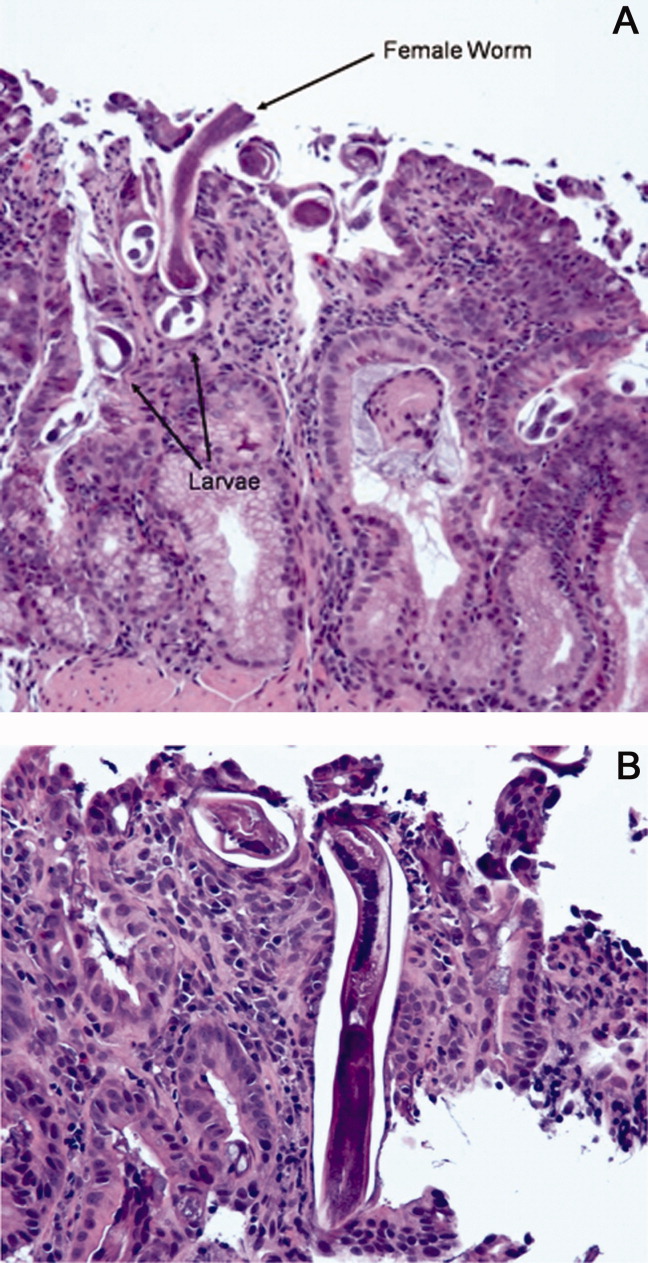

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids and stress‐dose steroids, and electrolyte abnormalities were corrected. Biopsies from the EGD and colonoscopy demonstrated numerous larvae within the mucosa of the body and antrum of the stomach, as well as duodenum. There were also rare detached larvae seen in the esophagus, and a few larvae within the ileal mucosa.

The patient appears to have Strongyloides hyperinfection, something he is at clear risk for, given his country of origin and his high‐dose corticosteroids. In retrospect, I was dissuaded from seriously considering a diagnosis of parasitic infection in large part because of the absence of peripheral eosinophilia, but this may not be seen in cases of hyperinfection. Additional clues, again in retrospect, were the repeated abscesses with bowel flora and the seemingly nonspecific abdominal rash. I would treat with a course of ivermectin, and carefully monitor his response.

The characteristics of the larvae were suggestive of Strongyloides species (Figure 3). A subsequent stool test for ova and parasites was positive for Strongyloides larvae. The patient was given a single dose of ivermectin. An endocrinology consultant felt that he did not have adrenal insufficiency, and it was recommended that his steroids be tapered off. He was discharged home once he clinically improved.

Although one or two doses of ivermectin typically suffices for uncomplicated strongyloidiasis, the risk of failure in hyperinfection mandates a longer treatment course. I don't believe this patient has been adequately treated, although the removal of his steroids will be helpful.

He was readmitted 3 days later with recrudescent symptoms, and his stool remained positive for Strongyloides. He received 2 weeks of ivermectin and albendazole, and was ultimately discharged to a rehabilitation facility after a complicated hospital stay. Nine months later, the patient was reported to be doing well.

COMMENTARY

This patient's immigration status from the developing world, high‐dose corticosteroid use, and complex clinical course all suggested the possibility of an underlying chronic infectious process. Although the discussant recognized this early on and later briefly mentioned strongyloidiasis as a potential cause of intestinal obstruction, the diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection was not suspected until incontrovertible evidence for it was obtained on EGD. Failure to make the diagnosis earlier by both the involved clinicians and the discussant probably stemmed largely from two factors: the absence of eosinophilia; and lack of recognition that purpura may be seen in cases of hyperinfection, presumably reflecting larval infiltration of the dermis.1 Although eosinophilia accompanies most cases of stronglyloidiasis and may be very pronounced, patients with hyperinfection syndrome frequently fail to mount an eosinophilic response due to underlying immunosuppression, with eosinophilia absent in 70% of such patients in a study from Taiwan.2

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode that causes strongyloidiasis. It affects as many as 100 million people globally,3 mainly in tropical and subtropical areas, but is also endemic in the Southeastern United States, Europe, and Japan. Risk factors include male sex, White race, alcoholism, working in contact with soil (farmers, coal mine workers, etc.), chronic care institutionalization, and low socioeconomic status. In nonendemic regions, it more commonly affects travelers, immigrants, or military personnel.4, 5

The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complex. Infective larvae penetrate the skin through contact with contaminated soil, enter the venous system via lymphatics, and travel to the lung.4, 6 Here, they ascend the tracheobronchial tree and migrate to the gut. In the intestine, larvae develop into adult female worms that burrow into the intestinal mucosa. These worms lay eggs that develop into noninfective rhabditiform larvae, which are then expelled in the stool. Some of the rhabditiform larvae, however, develop into infective filariform larvae, which may penetrate colonic mucosa or perianal skin, enter the bloodstream, and lead to the cycle of autoinfection and chronic strongyloidiasis (carrier state). Autoinfection typically involves a low parasite burden, and is controlled by both host immune factors as well as parasitic factors.7 The mechanism of autoinfection can lead to the persistence of strongyloidiasis for decades after the initial infection, as has been documented in former World War II prisoners of war.8

Factors leading to the impairment of cell‐mediated immunity predispose chronically infected individuals to hyperinfection, as occurred in this patient. The most important of these are corticosteroid administration and Human T‐lymphotropic virus Type‐1 (HTLV‐1) infection, both of which cause significant derangement in TH1/TH2 immune system balance.5, 9 In the hyperinfection syndrome, the burden of parasites increases dramatically, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations. Gastrointestinal phenomena frequently predominate, including watery diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, nausea/vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, and occasionally small bowel obstruction. Pulmonary manifestations are likewise common, and include cough, dyspnea, and wheezing. Cutaneous findings are not uncommon, classically pruritic linear lesions of the abdomen, buttocks, and lower extremities which may be rapidly migratory (larva currens), although purpura and petechiae as displayed by our patient appear to be under‐recognized findings in hyperinfection.2, 5 Gram‐negative bacillary meningitis has been well reported as a complication of migrating larvae, and a wide variety of other organs may rarely be involved.5, 10

The presence of chronic strongyloidiasis should be suspected in patients with ongoing gastrointestinal and/or pulmonary symptoms, or unexplained eosinophilia with a potential exposure history, such as immigrants from Southeast Asia. Diagnosis in these individuals is currently most often made serologically, although stool exam provides a somewhat higher specificity for active infection, at the expense of lower sensitivity.3, 11 In the setting of hyperinfection, stool studies are almost uniformly positive for S. stercoralis, and sputum may be diagnostic as well. Consequently, failure to reach the diagnosis usually reflects a lack of clinical suspicion.5

The therapy of choice for strongyloidiasis is currently ivermectin, with a single dose repeated once, 2 weeks later, highly efficacious in eradicating chronic infection. Treatment of hyperinfection is more challenging and less well studied, but clearly necessitates a more prolonged course of treatment. Many experts advocate treating until worms are no longer present in the stool; some have suggested the combination of ivermectin and albendazole as this patient received, although this has not been examined in controlled fashion.

The diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection is typically delayed or missed because of the failure to consider it, with reported mortality rates as high as 50% in hyperinfection and 87% in disseminated disease.3, 12, 13 This patient fortunately was diagnosed, albeit in delayed fashion, proving the maxim better late than never. His case highlights the need for increased clinical awareness of strongyloidiasis, and specifically the need to consider the possibility of chronic Strongyloides infection prior to administering immunosuppressive medications. In particular, serologic screening of individuals from highly endemic areas for strongyloidiasis, when initiating extended courses of corticosteroids, seems prudent.13

Teaching Points

-

Chronic strongyloidiasis is common in the developing world (particularly Southeast Asia), and places infected individuals at significant risk of life‐threatening hyperinfection if not recognized and treated prior to the initiation of immunosuppressive medication, especially corticosteroids.

-

Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome may be protean in its manifestations, but most commonly includes gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and cutaneous signs and symptoms.

- ,,, et al.Disseminated strongyloidiasis in immunocompromised patients—report of three cases.Int J Dermatol.2009;48(9):975–978.

- ,,, et al.Clinical manifestations of strongyloidiasis in southern Taiwan.J Microbiol Immunol Infect.2002;35(1):29–36.

- ,.Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection.Clin Infect Dis.2001;33(7):1040–1047.

- ,,.Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.Clin Mol Allergy.2006;4:8.

- ,.Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population.Clin Microbiol Rev.2004;17(1):208–217.

- ,,.Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management and determinants of outcome.J Clin Gastroenterol2005;39(3):203–211.

- .Dysregulation of strongyloidiasis: a new hypothesis.Clin Microbiol Rev.1992;5(4):345–355.

- ,,,.Consequences of captivity: health effects of Far East imprisonment in World War II.Q J Med.2009;102:87–96.

- ,,,.Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome: an emerging global infectious disease.Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.2008;102(4):314–318.

- ,,,,,.Strongyloides hyperinfection presenting as acute respiratory failure and Gram‐negative sepsis.Chest.2005;128(5):3681–3684.

- ,,, et al.Use of enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay and dipstick assay for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in humans.J Clin Microbiol.2007;45:438–442.

- ,,,,,.Complicated and fatal Strongyloides infection in Canadians: risk factors, diagnosis and management.Can Med Assoc J.2004;171:479–484.

- ,,, et al.Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case series and worldwide physicians‐in‐training survey.Am J Med.2007;120(6):545.e1–545.e8.

A 59‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with the acute onset of right‐sided abdominal and flank pain. The pain had begun the previous night, was constant and progressively worsening, and radiated to his right groin. He denied fever, nausea, emesis, or change in his bowel habits, but he did notice mild right lower quadrant discomfort with micturition. Upon further questioning, he also complained of mild dyspnea on climbing stairs and an unspecified recent weight loss.

The most common cause of acute severe right‐sided flank and abdominal pain radiating to the groin and associated with dysuria in a middle‐aged man is ureteral colic. Other etiologies important to consider include retrocecal appendicitis, pyelonephritis, and, rarely, a dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. This patient's seemingly recent onset exertional dyspnea and weight loss do not neatly fit any of the above, however.

His past medical history was significant for diabetes mellitus and pemphigus vulgaris diagnosed 7 months previously. He had been treated with prednisone, and the dose decreased from 100 to 60 mg daily, 1 month previously, due to poor glycemic control as well as steroid‐induced neuropathy and myopathy. His other medications included naproxen sodium and ibuprofen for back pain, azathioprine, insulin, pioglitazone, and glimiperide. He had no past surgical history. He had lived in the United States since his emigration from Thailand in 1971. His last trip to Thailand was 5 years previously. He was a taxi cab driver. He had a ten‐pack year history of tobacco use, but had quit 20 years prior. He denied history of alcohol or intravenous drug use.

Pemphigus vulgaris is unlikely to be directly related to this patient's presentation, but in light of his poorly controlled diabetes, his azathioprine use, and particularly his high‐dose corticosteroids, he is certainly immunocompromised. Accordingly, a disseminated infection, either newly acquired or reactivated, merits consideration. His history of residence in, and subsequent travel to, Southeast Asia raises the possibility of several diseases, each of which may be protean in their manifestations; these include tuberculosis, melioidosis, and penicilliosis (infection with Penicillium marneffei). The first two may reactivate long after initial exposure, particularly with insults to the immune system. The same is probably true of penicilliosis, although I am not certain of this. On a slightly less exotic note, domestically acquired infection with histoplasmosis or other endemic fungi is possible.

On examination he was afebrile, had a pulse of 130 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 65/46 mmHg. His oxygen saturation was 92%. He appeared markedly cushingoid, and had mild pallor and generalized weakness. Cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. His abdominal exam was notable for distention and hypoactive bowel sounds, with tenderness and firmness to palpation on the right side. Peripheral pulses were normal. Examination of the skin demonstrated ecchymoses over the bilateral forearms, and several healed pemphigus lesions on the abdomen and upper extremities.

The patient's severely deranged hemodynamic parameters indicate either current or impending shock, and resuscitative measures should proceed in tandem with diagnostic efforts. The cause of his shock seems most likely to be either hypovolemic (abdominal wall or intra‐abdominal hemorrhage, or conceivably massive third spacing from an intra‐abdominal catastrophe), or distributive (sepsis, or acute adrenal insufficiency if he has missed recent steroid doses). His ecchymoses may simply reflect chronic glucocorticoid use, but also raise suspicion for a coagulopathy. Provided the patient can be stabilized to allow this, I would urgently obtain a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

Initial laboratory studies demonstrated a hemoglobin of 9.1 g/dL, white blood cell count 8000/L with 33% bands, 48% segmented neutrophils, 18% lymphocytes, and 0.7% eosinophils, platelet count 356,000/L, sodium 128 mmol/L, BUN 52 mg/dL, creatinine 2.3 mg/dL, and glucose of 232 mg/dL. Coagulation studies were normal, and lactic acid was 1.8 mmol/L (normal range, 0.7‐2.1). Fibrinogen was normal at 591 and LDH was mildly elevated at 654 (normal range, 313‐618 U/L). Total protein and albumin were 3.6 and 1.9 g/dL, respectively. Total bilirubin was 0.6 mg/dL. Random serum cortisol was 20.2 g/dL. Liver enzymes, amylase, lipase, iron stores, B12, folate, and stool for occult blood were normal. Initial cardiac biomarkers were negative, but subsequent troponin‐I was 3.81 ng/mL (elevated, >1.00). Urinalysis showed 0‐4 white blood cells per high powered field.

The laboratory studies provide a variety of useful, albeit nonspecific, information. The high percentage of band forms on white blood cell differential further raises concern for an infectious process, although severe noninfectious stress can also cause this. While we do not know whether the patient's renal failure is acute, I suspect that it is, and may result from a variety of insults including sepsis, hypotension, and volume depletion. His moderately elevated troponin‐I likely reflects supplydemand mismatch or sepsis. I would like to see an electrocardiogram, and I remain very interested in obtaining abdominal imaging.

Chest radiography showed pulmonary vascular congestion without evidence of pneumothorax. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed retroperitoneal fluid bilaterally (Figure 1). This was described as suspicious for ascites versus hemorrhage, but no obvious source of bleeding was identified. There was also a small amount of right perinephric fluid, but no evidence of a renal mass. The abdominal aorta was normal; there was no lymphadenopathy.

The CT image appears to speak against simple ascites, and seems most consistent with either blood or an infectious process. Consequently, the loculated right retroperitoneal collection should be aspirated, and fluid sent for fungal, acid‐fast, and modified acid‐fast (i.e., for Nocardia) stains and culture, in addition to Gram stain and routine aerobic and anaerobic cultures.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Stress‐dose steroids were administered, and he improved after resuscitation with fluid and blood. His renal function normalized. Urine and blood cultures returned negative. His hematocrit and multiple repeat CT scans of the abdomen remained stable. A retroperitoneal hemorrhage was diagnosed, and surgical intervention was deemed unnecessary. Both adenosine thallium stress test and echocardiogram were normal. He was continued on 60 mg prednisone daily and discharged home with outpatient follow‐up.

This degree of improvement with volume expansion (and steroids) suggests the patient was markedly volume depleted upon presentation. Although a formal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test was apparently not performed, the random cortisol level suggests adrenal insufficiency was unlikely to have been primarily responsible. While retroperitoneal hemorrhage is possible, the loculated appearance of the collection suggests infection is more likely.

Three weeks later, he was readmitted with recurrent right‐sided abdominal and flank pain. His temperature was 101.3F, and he was tachycardic and hypotensive. His examination was similar to that at the time of his previous presentation. Laboratory data revealed white blood cell count of 13,100/L with 43% bands, hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dL, glucose of 343 mg/dL, bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, normal anion gap and renal function, and lactic acid of 4.5 mmol/L. Liver function tests were normal except for an albumin of 3.0 g/dL. CT scan of the abdomen revealed loculated retroperitoneal fluid collections, increased in size since the prior scan.

The patient is once again evidencing at least early shock, manifested in his deranged hemodynamics and elevated lactate level. I remain puzzled by the fact that he appeared to respond to fluids alone at the time of his initial hospital stay, unless adrenal insufficiency played a greater role than I suspected. Of note, acute adrenal insufficiency could explain much of the current picture, including fever, and bland (uninfected) hematomas are an underappreciated cause of both fever and leukocytosis. Having said this, I remain concerned that his retroperitoneal fluid collections represent abscesses. The most accessible of these should be sampled.

Aspiration of the retroperitoneal fluid yielded purulent material which grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. The cultures were negative for mycobacteria and fungus. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Drains were placed, and he was followed as an outpatient. His fever and leukocytosis subsided, and he completed a 6‐week course of trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. CT imaging confirmed complete evacuation of the fluid.

Retroperitoneal abscesses frequently present in smoldering fashion, although patients may be quite ill by the time of presentation. Most of these are secondary, i.e., they arise from another abnormality in the retroperitoneum. Most commonly this is in the large bowel, kidney, pancreas, or spine. I would carefully scour his follow‐up imaging for additional clues and, if unrevealing, proceed to colonoscopy.

He returned 1 month after drain removal, with 2‐3 days of nausea and abdominal pain. His abdomen was moderately distended but nontender, and multiple persistent petechial and purpuric lesions were present on the upper back, chest, torso, and arms. Abdominal CT scan revealed small bowel obstruction and a collection of fluid in the left paracolic gutter extending into the left retrorenal space.

The patient does not appear to have obvious risk factors for developing a small bowel obstruction. No mention is made of the presence or absence of a transition point on the CT scan, and this should be ascertained. His left‐sided abdominal fluid collection is probably infectious in nature, and I continue to be suspicious of a large bowel (or distal small bowel) source, via either gut perforation or bacterial translocation. The collection needs to be percutaneously drained for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons, and broadly cultured. Finally, we need to account for the described dermatologic manifestations. The purpuric/petechial lesions sound vasculitic rather than thrombocytopenic in origin based on location; conversely, they may simply reflect a corticosteroid‐related adverse effect. I would like to know whether the purpura was palpable, and to repeat a complete blood count with peripheral smear.

Laboratory data showed hemoglobin of 9.3 g/dL, a platelet count of 444,000/L, and normal coagulation studies. The purpura was nonpalpable (Figure 2). The patient had a nasogastric tube placed for decompression, with bilious drainage. His left retroperitoneal fluid was drained, with cultures yielding Enterococcus faecalis and Enterobacter cloacae. The patient was treated with a course of broad‐spectrum antibiotics. His obstruction improved and the retroperitoneal collection resolved on follow‐up imaging. However, 2 days later, he had recurrent pain; abdominal CT showed a recurrence of small bowel obstruction with an unequivocal transition point in the distal jejunum. A small fluid collection was noted in the left retroperitoneum with a trace of gas in it. He improved with nasogastric suction, his prednisone was tapered to 30 mg daily, and he was discharged home.

The isolation of both Enterococcus and Enterobacter species from his fluid collection, along with the previous isolation of Klebsiella, strongly suggest a bowel source for his recurrent abscesses. Based on this CT report, the patient has clear evidence of at least partial small bowel obstruction. He lacks a history of prior abdominal surgery or other more typical reasons for obstruction caused by extrinsic compression, such as hernia, although it is possible his recurrent abdominal infections may have led to obstruction due to scarring and adhesions. An intraluminal cause of obstruction also needs to be considered, with causes including malignancy (lymphoma, carcinoid, and adenocarcinoma), Crohn's disease, and infections including tuberculosis as well as parasites such as Taenia and Strongyloides. While the purpura is concerning, given the nonpalpable character along with a normal platelet count and coagulation studies, it may be reasonable to provisionally attribute it to high‐dose corticosteroid use.

He was admitted a fourth time a week after being discharged, with nausea, generalized weakness, and weight loss. At presentation, he had a blood pressure of 95/65 mmHg. His white blood cell count was 5,900/L, with 79% neutrophils and 20% bands. An AM cortisol was 18.8 /dL. He was thought to have adrenal insufficiency from steroid withdrawal, was treated with intravenous fluids and steroids, and discharged on a higher dose of prednisone at 60 mg daily. One week later, he again returned to the hospital with watery diarrhea, emesis, and generalized weakness. His blood pressure was 82/50 mmHg, and his abdomen appeared benign. He also had an erythematous rash over his mid‐abdomen. Laboratory data was significant for a sodium of 127 mmol/L, potassium of 3.0 mmol/L, chloride of 98 mmol/L, bicarbonate of 26 mmol/L, glucose of 40 mg/dL, lactate of 14 mmol/L, and albumin of 1.0 g/dL. Stool assay for Clostridium difficile was negative. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed small bilateral pleural effusions and small bowel fluid consistent with gastroenteritis, but without signs of obstruction. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed bile backwash into the stomach, as well as inflammatory changes in the proximal and mid‐stomach, and inflammatory reaction and edema in the proximal duodenum. Colonoscopy showed normal appearing ileum and colon.

The patient's latest laboratory values appear to reflect his chronic illness and superimposed diarrhea. I am perplexed by his markedly elevated serum lactate value in association with a normal bicarbonate and low anion gap, and would repeat the lactate level to ensure this is not spurious. His hypoglycemia probably reflects a failure to adjust or discontinue his diabetic medications, although both hypoglycemia and type B lactic acidosis are occasionally manifestations of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The normal colonoscopy findings are helpful in exonerating the colon, provided the preparation was adequate. Presumably, the abnormal areas of the stomach and duodenum were biopsied; I remain suspicious that the answer may lie in the jejunum.

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids and stress‐dose steroids, and electrolyte abnormalities were corrected. Biopsies from the EGD and colonoscopy demonstrated numerous larvae within the mucosa of the body and antrum of the stomach, as well as duodenum. There were also rare detached larvae seen in the esophagus, and a few larvae within the ileal mucosa.

The patient appears to have Strongyloides hyperinfection, something he is at clear risk for, given his country of origin and his high‐dose corticosteroids. In retrospect, I was dissuaded from seriously considering a diagnosis of parasitic infection in large part because of the absence of peripheral eosinophilia, but this may not be seen in cases of hyperinfection. Additional clues, again in retrospect, were the repeated abscesses with bowel flora and the seemingly nonspecific abdominal rash. I would treat with a course of ivermectin, and carefully monitor his response.

The characteristics of the larvae were suggestive of Strongyloides species (Figure 3). A subsequent stool test for ova and parasites was positive for Strongyloides larvae. The patient was given a single dose of ivermectin. An endocrinology consultant felt that he did not have adrenal insufficiency, and it was recommended that his steroids be tapered off. He was discharged home once he clinically improved.

Although one or two doses of ivermectin typically suffices for uncomplicated strongyloidiasis, the risk of failure in hyperinfection mandates a longer treatment course. I don't believe this patient has been adequately treated, although the removal of his steroids will be helpful.

He was readmitted 3 days later with recrudescent symptoms, and his stool remained positive for Strongyloides. He received 2 weeks of ivermectin and albendazole, and was ultimately discharged to a rehabilitation facility after a complicated hospital stay. Nine months later, the patient was reported to be doing well.

COMMENTARY

This patient's immigration status from the developing world, high‐dose corticosteroid use, and complex clinical course all suggested the possibility of an underlying chronic infectious process. Although the discussant recognized this early on and later briefly mentioned strongyloidiasis as a potential cause of intestinal obstruction, the diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection was not suspected until incontrovertible evidence for it was obtained on EGD. Failure to make the diagnosis earlier by both the involved clinicians and the discussant probably stemmed largely from two factors: the absence of eosinophilia; and lack of recognition that purpura may be seen in cases of hyperinfection, presumably reflecting larval infiltration of the dermis.1 Although eosinophilia accompanies most cases of stronglyloidiasis and may be very pronounced, patients with hyperinfection syndrome frequently fail to mount an eosinophilic response due to underlying immunosuppression, with eosinophilia absent in 70% of such patients in a study from Taiwan.2

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode that causes strongyloidiasis. It affects as many as 100 million people globally,3 mainly in tropical and subtropical areas, but is also endemic in the Southeastern United States, Europe, and Japan. Risk factors include male sex, White race, alcoholism, working in contact with soil (farmers, coal mine workers, etc.), chronic care institutionalization, and low socioeconomic status. In nonendemic regions, it more commonly affects travelers, immigrants, or military personnel.4, 5

The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complex. Infective larvae penetrate the skin through contact with contaminated soil, enter the venous system via lymphatics, and travel to the lung.4, 6 Here, they ascend the tracheobronchial tree and migrate to the gut. In the intestine, larvae develop into adult female worms that burrow into the intestinal mucosa. These worms lay eggs that develop into noninfective rhabditiform larvae, which are then expelled in the stool. Some of the rhabditiform larvae, however, develop into infective filariform larvae, which may penetrate colonic mucosa or perianal skin, enter the bloodstream, and lead to the cycle of autoinfection and chronic strongyloidiasis (carrier state). Autoinfection typically involves a low parasite burden, and is controlled by both host immune factors as well as parasitic factors.7 The mechanism of autoinfection can lead to the persistence of strongyloidiasis for decades after the initial infection, as has been documented in former World War II prisoners of war.8

Factors leading to the impairment of cell‐mediated immunity predispose chronically infected individuals to hyperinfection, as occurred in this patient. The most important of these are corticosteroid administration and Human T‐lymphotropic virus Type‐1 (HTLV‐1) infection, both of which cause significant derangement in TH1/TH2 immune system balance.5, 9 In the hyperinfection syndrome, the burden of parasites increases dramatically, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations. Gastrointestinal phenomena frequently predominate, including watery diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, nausea/vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, and occasionally small bowel obstruction. Pulmonary manifestations are likewise common, and include cough, dyspnea, and wheezing. Cutaneous findings are not uncommon, classically pruritic linear lesions of the abdomen, buttocks, and lower extremities which may be rapidly migratory (larva currens), although purpura and petechiae as displayed by our patient appear to be under‐recognized findings in hyperinfection.2, 5 Gram‐negative bacillary meningitis has been well reported as a complication of migrating larvae, and a wide variety of other organs may rarely be involved.5, 10

The presence of chronic strongyloidiasis should be suspected in patients with ongoing gastrointestinal and/or pulmonary symptoms, or unexplained eosinophilia with a potential exposure history, such as immigrants from Southeast Asia. Diagnosis in these individuals is currently most often made serologically, although stool exam provides a somewhat higher specificity for active infection, at the expense of lower sensitivity.3, 11 In the setting of hyperinfection, stool studies are almost uniformly positive for S. stercoralis, and sputum may be diagnostic as well. Consequently, failure to reach the diagnosis usually reflects a lack of clinical suspicion.5

The therapy of choice for strongyloidiasis is currently ivermectin, with a single dose repeated once, 2 weeks later, highly efficacious in eradicating chronic infection. Treatment of hyperinfection is more challenging and less well studied, but clearly necessitates a more prolonged course of treatment. Many experts advocate treating until worms are no longer present in the stool; some have suggested the combination of ivermectin and albendazole as this patient received, although this has not been examined in controlled fashion.

The diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection is typically delayed or missed because of the failure to consider it, with reported mortality rates as high as 50% in hyperinfection and 87% in disseminated disease.3, 12, 13 This patient fortunately was diagnosed, albeit in delayed fashion, proving the maxim better late than never. His case highlights the need for increased clinical awareness of strongyloidiasis, and specifically the need to consider the possibility of chronic Strongyloides infection prior to administering immunosuppressive medications. In particular, serologic screening of individuals from highly endemic areas for strongyloidiasis, when initiating extended courses of corticosteroids, seems prudent.13

Teaching Points

-

Chronic strongyloidiasis is common in the developing world (particularly Southeast Asia), and places infected individuals at significant risk of life‐threatening hyperinfection if not recognized and treated prior to the initiation of immunosuppressive medication, especially corticosteroids.

-

Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome may be protean in its manifestations, but most commonly includes gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and cutaneous signs and symptoms.

A 59‐year‐old man presented to the emergency department with the acute onset of right‐sided abdominal and flank pain. The pain had begun the previous night, was constant and progressively worsening, and radiated to his right groin. He denied fever, nausea, emesis, or change in his bowel habits, but he did notice mild right lower quadrant discomfort with micturition. Upon further questioning, he also complained of mild dyspnea on climbing stairs and an unspecified recent weight loss.

The most common cause of acute severe right‐sided flank and abdominal pain radiating to the groin and associated with dysuria in a middle‐aged man is ureteral colic. Other etiologies important to consider include retrocecal appendicitis, pyelonephritis, and, rarely, a dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. This patient's seemingly recent onset exertional dyspnea and weight loss do not neatly fit any of the above, however.

His past medical history was significant for diabetes mellitus and pemphigus vulgaris diagnosed 7 months previously. He had been treated with prednisone, and the dose decreased from 100 to 60 mg daily, 1 month previously, due to poor glycemic control as well as steroid‐induced neuropathy and myopathy. His other medications included naproxen sodium and ibuprofen for back pain, azathioprine, insulin, pioglitazone, and glimiperide. He had no past surgical history. He had lived in the United States since his emigration from Thailand in 1971. His last trip to Thailand was 5 years previously. He was a taxi cab driver. He had a ten‐pack year history of tobacco use, but had quit 20 years prior. He denied history of alcohol or intravenous drug use.

Pemphigus vulgaris is unlikely to be directly related to this patient's presentation, but in light of his poorly controlled diabetes, his azathioprine use, and particularly his high‐dose corticosteroids, he is certainly immunocompromised. Accordingly, a disseminated infection, either newly acquired or reactivated, merits consideration. His history of residence in, and subsequent travel to, Southeast Asia raises the possibility of several diseases, each of which may be protean in their manifestations; these include tuberculosis, melioidosis, and penicilliosis (infection with Penicillium marneffei). The first two may reactivate long after initial exposure, particularly with insults to the immune system. The same is probably true of penicilliosis, although I am not certain of this. On a slightly less exotic note, domestically acquired infection with histoplasmosis or other endemic fungi is possible.

On examination he was afebrile, had a pulse of 130 beats per minute and a blood pressure of 65/46 mmHg. His oxygen saturation was 92%. He appeared markedly cushingoid, and had mild pallor and generalized weakness. Cardiopulmonary examination was unremarkable. His abdominal exam was notable for distention and hypoactive bowel sounds, with tenderness and firmness to palpation on the right side. Peripheral pulses were normal. Examination of the skin demonstrated ecchymoses over the bilateral forearms, and several healed pemphigus lesions on the abdomen and upper extremities.

The patient's severely deranged hemodynamic parameters indicate either current or impending shock, and resuscitative measures should proceed in tandem with diagnostic efforts. The cause of his shock seems most likely to be either hypovolemic (abdominal wall or intra‐abdominal hemorrhage, or conceivably massive third spacing from an intra‐abdominal catastrophe), or distributive (sepsis, or acute adrenal insufficiency if he has missed recent steroid doses). His ecchymoses may simply reflect chronic glucocorticoid use, but also raise suspicion for a coagulopathy. Provided the patient can be stabilized to allow this, I would urgently obtain a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis.

Initial laboratory studies demonstrated a hemoglobin of 9.1 g/dL, white blood cell count 8000/L with 33% bands, 48% segmented neutrophils, 18% lymphocytes, and 0.7% eosinophils, platelet count 356,000/L, sodium 128 mmol/L, BUN 52 mg/dL, creatinine 2.3 mg/dL, and glucose of 232 mg/dL. Coagulation studies were normal, and lactic acid was 1.8 mmol/L (normal range, 0.7‐2.1). Fibrinogen was normal at 591 and LDH was mildly elevated at 654 (normal range, 313‐618 U/L). Total protein and albumin were 3.6 and 1.9 g/dL, respectively. Total bilirubin was 0.6 mg/dL. Random serum cortisol was 20.2 g/dL. Liver enzymes, amylase, lipase, iron stores, B12, folate, and stool for occult blood were normal. Initial cardiac biomarkers were negative, but subsequent troponin‐I was 3.81 ng/mL (elevated, >1.00). Urinalysis showed 0‐4 white blood cells per high powered field.

The laboratory studies provide a variety of useful, albeit nonspecific, information. The high percentage of band forms on white blood cell differential further raises concern for an infectious process, although severe noninfectious stress can also cause this. While we do not know whether the patient's renal failure is acute, I suspect that it is, and may result from a variety of insults including sepsis, hypotension, and volume depletion. His moderately elevated troponin‐I likely reflects supplydemand mismatch or sepsis. I would like to see an electrocardiogram, and I remain very interested in obtaining abdominal imaging.

Chest radiography showed pulmonary vascular congestion without evidence of pneumothorax. Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed retroperitoneal fluid bilaterally (Figure 1). This was described as suspicious for ascites versus hemorrhage, but no obvious source of bleeding was identified. There was also a small amount of right perinephric fluid, but no evidence of a renal mass. The abdominal aorta was normal; there was no lymphadenopathy.

The CT image appears to speak against simple ascites, and seems most consistent with either blood or an infectious process. Consequently, the loculated right retroperitoneal collection should be aspirated, and fluid sent for fungal, acid‐fast, and modified acid‐fast (i.e., for Nocardia) stains and culture, in addition to Gram stain and routine aerobic and anaerobic cultures.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit. Stress‐dose steroids were administered, and he improved after resuscitation with fluid and blood. His renal function normalized. Urine and blood cultures returned negative. His hematocrit and multiple repeat CT scans of the abdomen remained stable. A retroperitoneal hemorrhage was diagnosed, and surgical intervention was deemed unnecessary. Both adenosine thallium stress test and echocardiogram were normal. He was continued on 60 mg prednisone daily and discharged home with outpatient follow‐up.

This degree of improvement with volume expansion (and steroids) suggests the patient was markedly volume depleted upon presentation. Although a formal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test was apparently not performed, the random cortisol level suggests adrenal insufficiency was unlikely to have been primarily responsible. While retroperitoneal hemorrhage is possible, the loculated appearance of the collection suggests infection is more likely.

Three weeks later, he was readmitted with recurrent right‐sided abdominal and flank pain. His temperature was 101.3F, and he was tachycardic and hypotensive. His examination was similar to that at the time of his previous presentation. Laboratory data revealed white blood cell count of 13,100/L with 43% bands, hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dL, glucose of 343 mg/dL, bicarbonate 25 mmol/L, normal anion gap and renal function, and lactic acid of 4.5 mmol/L. Liver function tests were normal except for an albumin of 3.0 g/dL. CT scan of the abdomen revealed loculated retroperitoneal fluid collections, increased in size since the prior scan.

The patient is once again evidencing at least early shock, manifested in his deranged hemodynamics and elevated lactate level. I remain puzzled by the fact that he appeared to respond to fluids alone at the time of his initial hospital stay, unless adrenal insufficiency played a greater role than I suspected. Of note, acute adrenal insufficiency could explain much of the current picture, including fever, and bland (uninfected) hematomas are an underappreciated cause of both fever and leukocytosis. Having said this, I remain concerned that his retroperitoneal fluid collections represent abscesses. The most accessible of these should be sampled.

Aspiration of the retroperitoneal fluid yielded purulent material which grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. The cultures were negative for mycobacteria and fungus. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Drains were placed, and he was followed as an outpatient. His fever and leukocytosis subsided, and he completed a 6‐week course of trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. CT imaging confirmed complete evacuation of the fluid.

Retroperitoneal abscesses frequently present in smoldering fashion, although patients may be quite ill by the time of presentation. Most of these are secondary, i.e., they arise from another abnormality in the retroperitoneum. Most commonly this is in the large bowel, kidney, pancreas, or spine. I would carefully scour his follow‐up imaging for additional clues and, if unrevealing, proceed to colonoscopy.

He returned 1 month after drain removal, with 2‐3 days of nausea and abdominal pain. His abdomen was moderately distended but nontender, and multiple persistent petechial and purpuric lesions were present on the upper back, chest, torso, and arms. Abdominal CT scan revealed small bowel obstruction and a collection of fluid in the left paracolic gutter extending into the left retrorenal space.

The patient does not appear to have obvious risk factors for developing a small bowel obstruction. No mention is made of the presence or absence of a transition point on the CT scan, and this should be ascertained. His left‐sided abdominal fluid collection is probably infectious in nature, and I continue to be suspicious of a large bowel (or distal small bowel) source, via either gut perforation or bacterial translocation. The collection needs to be percutaneously drained for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons, and broadly cultured. Finally, we need to account for the described dermatologic manifestations. The purpuric/petechial lesions sound vasculitic rather than thrombocytopenic in origin based on location; conversely, they may simply reflect a corticosteroid‐related adverse effect. I would like to know whether the purpura was palpable, and to repeat a complete blood count with peripheral smear.

Laboratory data showed hemoglobin of 9.3 g/dL, a platelet count of 444,000/L, and normal coagulation studies. The purpura was nonpalpable (Figure 2). The patient had a nasogastric tube placed for decompression, with bilious drainage. His left retroperitoneal fluid was drained, with cultures yielding Enterococcus faecalis and Enterobacter cloacae. The patient was treated with a course of broad‐spectrum antibiotics. His obstruction improved and the retroperitoneal collection resolved on follow‐up imaging. However, 2 days later, he had recurrent pain; abdominal CT showed a recurrence of small bowel obstruction with an unequivocal transition point in the distal jejunum. A small fluid collection was noted in the left retroperitoneum with a trace of gas in it. He improved with nasogastric suction, his prednisone was tapered to 30 mg daily, and he was discharged home.

The isolation of both Enterococcus and Enterobacter species from his fluid collection, along with the previous isolation of Klebsiella, strongly suggest a bowel source for his recurrent abscesses. Based on this CT report, the patient has clear evidence of at least partial small bowel obstruction. He lacks a history of prior abdominal surgery or other more typical reasons for obstruction caused by extrinsic compression, such as hernia, although it is possible his recurrent abdominal infections may have led to obstruction due to scarring and adhesions. An intraluminal cause of obstruction also needs to be considered, with causes including malignancy (lymphoma, carcinoid, and adenocarcinoma), Crohn's disease, and infections including tuberculosis as well as parasites such as Taenia and Strongyloides. While the purpura is concerning, given the nonpalpable character along with a normal platelet count and coagulation studies, it may be reasonable to provisionally attribute it to high‐dose corticosteroid use.

He was admitted a fourth time a week after being discharged, with nausea, generalized weakness, and weight loss. At presentation, he had a blood pressure of 95/65 mmHg. His white blood cell count was 5,900/L, with 79% neutrophils and 20% bands. An AM cortisol was 18.8 /dL. He was thought to have adrenal insufficiency from steroid withdrawal, was treated with intravenous fluids and steroids, and discharged on a higher dose of prednisone at 60 mg daily. One week later, he again returned to the hospital with watery diarrhea, emesis, and generalized weakness. His blood pressure was 82/50 mmHg, and his abdomen appeared benign. He also had an erythematous rash over his mid‐abdomen. Laboratory data was significant for a sodium of 127 mmol/L, potassium of 3.0 mmol/L, chloride of 98 mmol/L, bicarbonate of 26 mmol/L, glucose of 40 mg/dL, lactate of 14 mmol/L, and albumin of 1.0 g/dL. Stool assay for Clostridium difficile was negative. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed small bilateral pleural effusions and small bowel fluid consistent with gastroenteritis, but without signs of obstruction. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed bile backwash into the stomach, as well as inflammatory changes in the proximal and mid‐stomach, and inflammatory reaction and edema in the proximal duodenum. Colonoscopy showed normal appearing ileum and colon.

The patient's latest laboratory values appear to reflect his chronic illness and superimposed diarrhea. I am perplexed by his markedly elevated serum lactate value in association with a normal bicarbonate and low anion gap, and would repeat the lactate level to ensure this is not spurious. His hypoglycemia probably reflects a failure to adjust or discontinue his diabetic medications, although both hypoglycemia and type B lactic acidosis are occasionally manifestations of a paraneoplastic syndrome. The normal colonoscopy findings are helpful in exonerating the colon, provided the preparation was adequate. Presumably, the abnormal areas of the stomach and duodenum were biopsied; I remain suspicious that the answer may lie in the jejunum.

The patient was treated with intravenous fluids and stress‐dose steroids, and electrolyte abnormalities were corrected. Biopsies from the EGD and colonoscopy demonstrated numerous larvae within the mucosa of the body and antrum of the stomach, as well as duodenum. There were also rare detached larvae seen in the esophagus, and a few larvae within the ileal mucosa.

The patient appears to have Strongyloides hyperinfection, something he is at clear risk for, given his country of origin and his high‐dose corticosteroids. In retrospect, I was dissuaded from seriously considering a diagnosis of parasitic infection in large part because of the absence of peripheral eosinophilia, but this may not be seen in cases of hyperinfection. Additional clues, again in retrospect, were the repeated abscesses with bowel flora and the seemingly nonspecific abdominal rash. I would treat with a course of ivermectin, and carefully monitor his response.

The characteristics of the larvae were suggestive of Strongyloides species (Figure 3). A subsequent stool test for ova and parasites was positive for Strongyloides larvae. The patient was given a single dose of ivermectin. An endocrinology consultant felt that he did not have adrenal insufficiency, and it was recommended that his steroids be tapered off. He was discharged home once he clinically improved.

Although one or two doses of ivermectin typically suffices for uncomplicated strongyloidiasis, the risk of failure in hyperinfection mandates a longer treatment course. I don't believe this patient has been adequately treated, although the removal of his steroids will be helpful.

He was readmitted 3 days later with recrudescent symptoms, and his stool remained positive for Strongyloides. He received 2 weeks of ivermectin and albendazole, and was ultimately discharged to a rehabilitation facility after a complicated hospital stay. Nine months later, the patient was reported to be doing well.

COMMENTARY

This patient's immigration status from the developing world, high‐dose corticosteroid use, and complex clinical course all suggested the possibility of an underlying chronic infectious process. Although the discussant recognized this early on and later briefly mentioned strongyloidiasis as a potential cause of intestinal obstruction, the diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection was not suspected until incontrovertible evidence for it was obtained on EGD. Failure to make the diagnosis earlier by both the involved clinicians and the discussant probably stemmed largely from two factors: the absence of eosinophilia; and lack of recognition that purpura may be seen in cases of hyperinfection, presumably reflecting larval infiltration of the dermis.1 Although eosinophilia accompanies most cases of stronglyloidiasis and may be very pronounced, patients with hyperinfection syndrome frequently fail to mount an eosinophilic response due to underlying immunosuppression, with eosinophilia absent in 70% of such patients in a study from Taiwan.2

Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode that causes strongyloidiasis. It affects as many as 100 million people globally,3 mainly in tropical and subtropical areas, but is also endemic in the Southeastern United States, Europe, and Japan. Risk factors include male sex, White race, alcoholism, working in contact with soil (farmers, coal mine workers, etc.), chronic care institutionalization, and low socioeconomic status. In nonendemic regions, it more commonly affects travelers, immigrants, or military personnel.4, 5

The life cycle of S. stercoralis is complex. Infective larvae penetrate the skin through contact with contaminated soil, enter the venous system via lymphatics, and travel to the lung.4, 6 Here, they ascend the tracheobronchial tree and migrate to the gut. In the intestine, larvae develop into adult female worms that burrow into the intestinal mucosa. These worms lay eggs that develop into noninfective rhabditiform larvae, which are then expelled in the stool. Some of the rhabditiform larvae, however, develop into infective filariform larvae, which may penetrate colonic mucosa or perianal skin, enter the bloodstream, and lead to the cycle of autoinfection and chronic strongyloidiasis (carrier state). Autoinfection typically involves a low parasite burden, and is controlled by both host immune factors as well as parasitic factors.7 The mechanism of autoinfection can lead to the persistence of strongyloidiasis for decades after the initial infection, as has been documented in former World War II prisoners of war.8

Factors leading to the impairment of cell‐mediated immunity predispose chronically infected individuals to hyperinfection, as occurred in this patient. The most important of these are corticosteroid administration and Human T‐lymphotropic virus Type‐1 (HTLV‐1) infection, both of which cause significant derangement in TH1/TH2 immune system balance.5, 9 In the hyperinfection syndrome, the burden of parasites increases dramatically, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations. Gastrointestinal phenomena frequently predominate, including watery diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, nausea/vomiting, gastrointestinal bleeding, and occasionally small bowel obstruction. Pulmonary manifestations are likewise common, and include cough, dyspnea, and wheezing. Cutaneous findings are not uncommon, classically pruritic linear lesions of the abdomen, buttocks, and lower extremities which may be rapidly migratory (larva currens), although purpura and petechiae as displayed by our patient appear to be under‐recognized findings in hyperinfection.2, 5 Gram‐negative bacillary meningitis has been well reported as a complication of migrating larvae, and a wide variety of other organs may rarely be involved.5, 10

The presence of chronic strongyloidiasis should be suspected in patients with ongoing gastrointestinal and/or pulmonary symptoms, or unexplained eosinophilia with a potential exposure history, such as immigrants from Southeast Asia. Diagnosis in these individuals is currently most often made serologically, although stool exam provides a somewhat higher specificity for active infection, at the expense of lower sensitivity.3, 11 In the setting of hyperinfection, stool studies are almost uniformly positive for S. stercoralis, and sputum may be diagnostic as well. Consequently, failure to reach the diagnosis usually reflects a lack of clinical suspicion.5

The therapy of choice for strongyloidiasis is currently ivermectin, with a single dose repeated once, 2 weeks later, highly efficacious in eradicating chronic infection. Treatment of hyperinfection is more challenging and less well studied, but clearly necessitates a more prolonged course of treatment. Many experts advocate treating until worms are no longer present in the stool; some have suggested the combination of ivermectin and albendazole as this patient received, although this has not been examined in controlled fashion.

The diagnosis of Strongyloides hyperinfection is typically delayed or missed because of the failure to consider it, with reported mortality rates as high as 50% in hyperinfection and 87% in disseminated disease.3, 12, 13 This patient fortunately was diagnosed, albeit in delayed fashion, proving the maxim better late than never. His case highlights the need for increased clinical awareness of strongyloidiasis, and specifically the need to consider the possibility of chronic Strongyloides infection prior to administering immunosuppressive medications. In particular, serologic screening of individuals from highly endemic areas for strongyloidiasis, when initiating extended courses of corticosteroids, seems prudent.13

Teaching Points

-

Chronic strongyloidiasis is common in the developing world (particularly Southeast Asia), and places infected individuals at significant risk of life‐threatening hyperinfection if not recognized and treated prior to the initiation of immunosuppressive medication, especially corticosteroids.

-

Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome may be protean in its manifestations, but most commonly includes gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and cutaneous signs and symptoms.

- ,,, et al.Disseminated strongyloidiasis in immunocompromised patients—report of three cases.Int J Dermatol.2009;48(9):975–978.

- ,,, et al.Clinical manifestations of strongyloidiasis in southern Taiwan.J Microbiol Immunol Infect.2002;35(1):29–36.

- ,.Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection.Clin Infect Dis.2001;33(7):1040–1047.

- ,,.Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.Clin Mol Allergy.2006;4:8.

- ,.Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population.Clin Microbiol Rev.2004;17(1):208–217.

- ,,.Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management and determinants of outcome.J Clin Gastroenterol2005;39(3):203–211.

- .Dysregulation of strongyloidiasis: a new hypothesis.Clin Microbiol Rev.1992;5(4):345–355.

- ,,,.Consequences of captivity: health effects of Far East imprisonment in World War II.Q J Med.2009;102:87–96.

- ,,,.Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome: an emerging global infectious disease.Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.2008;102(4):314–318.

- ,,,,,.Strongyloides hyperinfection presenting as acute respiratory failure and Gram‐negative sepsis.Chest.2005;128(5):3681–3684.

- ,,, et al.Use of enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay and dipstick assay for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in humans.J Clin Microbiol.2007;45:438–442.

- ,,,,,.Complicated and fatal Strongyloides infection in Canadians: risk factors, diagnosis and management.Can Med Assoc J.2004;171:479–484.

- ,,, et al.Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case series and worldwide physicians‐in‐training survey.Am J Med.2007;120(6):545.e1–545.e8.

- ,,, et al.Disseminated strongyloidiasis in immunocompromised patients—report of three cases.Int J Dermatol.2009;48(9):975–978.

- ,,, et al.Clinical manifestations of strongyloidiasis in southern Taiwan.J Microbiol Immunol Infect.2002;35(1):29–36.

- ,.Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection.Clin Infect Dis.2001;33(7):1040–1047.

- ,,.Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome.Clin Mol Allergy.2006;4:8.

- ,.Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population.Clin Microbiol Rev.2004;17(1):208–217.

- ,,.Intestinal strongyloidiasis: recognition, management and determinants of outcome.J Clin Gastroenterol2005;39(3):203–211.

- .Dysregulation of strongyloidiasis: a new hypothesis.Clin Microbiol Rev.1992;5(4):345–355.

- ,,,.Consequences of captivity: health effects of Far East imprisonment in World War II.Q J Med.2009;102:87–96.

- ,,,.Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome: an emerging global infectious disease.Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg.2008;102(4):314–318.

- ,,,,,.Strongyloides hyperinfection presenting as acute respiratory failure and Gram‐negative sepsis.Chest.2005;128(5):3681–3684.

- ,,, et al.Use of enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay and dipstick assay for detection of Strongyloides stercoralis infection in humans.J Clin Microbiol.2007;45:438–442.

- ,,,,,.Complicated and fatal Strongyloides infection in Canadians: risk factors, diagnosis and management.Can Med Assoc J.2004;171:479–484.

- ,,, et al.Maltreatment of Strongyloides infection: case series and worldwide physicians‐in‐training survey.Am J Med.2007;120(6):545.e1–545.e8.

In the Literature

In This Edition

Literature at a Glance

A guide to this month’s studies

- Effect of restrictive antibiotic policies on dosing timeliness

- Desired consultation format and content

- Risk of cancer associated with CT imaging

- Bleeding, mortality with aspirin after peptic ulcer bleed

- Diagnosis of lung cancer after pneumonia

- Outcomes associated with hyponatremia

- Patient awareness, interest in inpatient medication list

- Monoclonal antibodies in C. difficile

Restrictive Antimicrobial Policy Delays Administration

Clinical question: Does the approval process for restricted on-formulary antimicrobials cause a significant delay in their administration?

Background: Widespread and often unwarranted, antimicrobial use in the hospital lends itself to the development of microbial resistance and increases overall costs. To curb such practices, many hospitals require subspecialty approval prior to dispensing select broad-spectrum antimicrobials. Though shown to improve outcomes, the impact of the approval process on the timeliness of antimicrobial administration remains to be seen.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Tertiary-care university hospital.

Synopsis: The study included 3,251 inpatients with computerized orders for a “stat” first dose of any of 24 pre-selected, parenteral antimicrobials. Time lag (more than one hour, and more than two hours) to nursing documentation of drug administration was separately analyzed for restricted and unrestricted antimicrobials.