User login

A Learning Health System Approach to Long COVID Care

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA)—along with systems across the world—has spent the past 2 years continuously adapting to meet the emerging needs of persons infected with COVID-19. With the development of effective vaccines and global efforts to mitigate transmission, attention has now shifted to long COVID care as the need for further outpatient health care becomes increasingly apparent.1,2

Background

Multiple terms describe the lingering, multisystem sequelae of COVID-19 that last longer than 4 weeks: long COVID, postacute COVID-19 syndrome, post-COVID condition, postacute sequalae of COVID-19, and COVID long hauler.1,3 Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cough, sleep disorders, brain fog or cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, pain, and changes in taste or smell that impact a person’s functioning.4,5 The multisystem nature of the postacute course of COVID-19 necessitates an interdisciplinary approach to devise comprehensive and individualized care plans.6-9 Research is needed to better understand this postacute state (eg, prevalence, underlying effects, characteristics of those who experience long COVID) to establish and evaluate cost-effective treatment approaches.

Many patients who are experiencing symptoms beyond the acute course of COVID-19 have been referred to general outpatient clinics or home health, which may lack the capacity and knowledge of this novel disease to effectively manage complex long COVID cases.2,3 To address this growing need, clinicians and leadership across a variety of disciplines and settings in the VHA created a community of practice (CoP) to create a mechanism for cross-facility communication, identify gaps in long COVID care and research, and cocreate knowledge on best practices for care delivery.

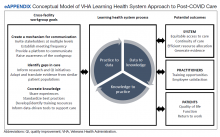

In this spirit, we are embracing a learning health system (LHS) approach that uses rapid-cycle methods to integrate data and real-world experience to iteratively evaluate and adapt models of long COVID care.10 Our clinically identified and data-driven objective is to provide high value health care to patients with long COVID sequalae by creating a framework to learn about this novel condition and develop innovative care models. This article provides an overview of our emerging LHS approach to the study of long COVID care that is fostering innovation and adaptability within the VHA. We describe 3 aspects of our engagement approach central to LHS: the ongoing development of a long COVID CoP dedicated to iteratively informing the bidirectional cycle of data from practice to research, results of a broad environmental scan of VHA long COVID care, and results of a survey administered to CoP members to inform ongoing needs of the community and identify early successful outcomes from participation.

Learning Health System Approach

The VHA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States serving more than 9 million veterans.11 Since 2017, the VHA has articulated a vision to become an LHS that informs and improves patient-centered care through practice-based and data-driven research (eAppendix).12 During the early COVID-19 pandemic, an LHS approach in the VHA was critical to rapidly establishing a data infrastructure for disease surveillance, coordinating data-driven solutions, leveraging use of technology, collaborating across the globe to identify best practices, and implementing systematic responses (eg, policies, workforce adjustments).

Our long COVID CoP was developed as clinical observations and ongoing conversations with stakeholders (eg, veterans, health care practitioners [HCPs], leadership) identified a need to effectively identify and treat the growing number of veterans with long COVID. This clinical issue is compounded by the limited but emerging evidence on the clinical presentation of prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, treatment, and subsequent care pathways. The VHA’s efforts and lessons learned within the lens of an LHS are applicable to other systems confronting the complex identification and management of patients with persistent and encumbering long COVID symptoms. The VHA is building upon the LHS approach to proactively prepare for and address future clinical or public health challenges that require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient/family centeredness.11

Community of Practice

As of January 25, 2022, our workgroup consisted of 128 VHA employees representing 29 VHA medical centers. Members of the multidisciplinary workgroup have diverse backgrounds with HCPs from primary care (eg, physicians, nurse practitioners), rehabilitation (eg, physical therapists), specialty care (eg, pulmonologists, physiatrists), mental health (eg, psychologists), and complementary and integrated health/Whole Health services (eg, practitoners of services such as yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, acupuncture). Members also include clinical, operations, and research leadership at local, regional, and national VHA levels. Our first objective as a large, diverse group was to establish shared goals, which included: (1) determining efficient communication pathways; (2) identifying gaps in care or research; and (3) cocreating knowledge to provide solutions to identified gaps.

Communication Mechanisms

Our first goal was to create an efficient mechanism for cross-facility communication. The initial CoP was formed in April 2021 and the first virtual meeting focused on reaching a consensus regarding the best way to communicate and proceed. We agreed to convene weekly at a consistent time, created a standard agenda template, and elected a lead facilitator of meeting proceedings. In addition, a member of the CoP recorded and took extensive meeting notes, which were later distributed to the entire CoP to accommodate varying schedules and ability to attend live meetings. Approximately 20 to 30 participants attend the meetings in real-time.

To consolidate working documents, information, and resources in one location, we created a platform to communicate via a Microsoft Teams channel. All CoP members are given access to the folders and allowed to add to the growing library of resources. Resources include clinical assessment and note templates for electronic documentation of care, site-specific process maps, relevant literature on screening and interventions identified by practice members, and meeting notes along with the recordings. A chat feature alerts CoP members to questions posed by other members. Any resources or information shared on the chat discussion are curated by CoP leaders to disseminate to all members. Importantly, this platform allowed us to communicate efficiently within the VHA organization by creating a centralized space for documents and the ability to correspond with all or select members of the CoP. Additional VHA employees can easily be referred and request access.

To increase awareness of the CoP, expand reach, and diversify perspectives, every participant was encouraged to invite colleagues and stakeholders with interest or experience in long COVID care to join. While patients are not included in this CoP, we are working closely with the VHA user experience workgroup (many members overlap) that is gathering patient and caregiver perspectives on their COVID-19 experience and long COVID care. Concurrently, CoP members and leadership facilitate communication and set up formal collaborations with other non-VHA health care systems to create an intersystem network of collaboration for long COVID care. This approach further enhances the speed at which we can work together to share lessons learned and stay up-to-date on emerging evidence surrounding long COVID care.

Identifying Gaps in Care and Research

Our second goal was to identify gaps in care or knowledge to inform future research and quality improvement initiatives, while also creating a foundation to cocreate knowledge about safe, effective care management of the novel long COVID sequelae. To translate knowledge, we must first identify and understand the gaps between the current, best available evidence and current care practices or policies impacting that delivery.13 As such, the structured meeting agenda and facilitated meeting discussions focused on understanding current clinical decision making and the evidence base. We shared VHA evidence synthesis reports and living rapid reviews on complications following COVID-19 illness (ie, major organ damage and posthospitalization health care use) that provided an objective evidence base on common long COVID complications.14,15

Since long COVID is a novel condition, we drew from literature in similar patient populations and translated that information in the context of our current knowledge of this unique syndrome. For example, we discussed the predominant and persistent symptom of fatigue post-COVID.5 In particular, the CoP discussed challenges in identifying and treating post-COVID fatigue, which is often a vague symptom with multiple or interacting etiologies that require a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach. As such, we reviewed, adapted, and translated identification and treatment strategies from the literature on chronic fatigue syndrome to patients with post-COVID syndrome.16,17 We continue to work collaboratively and engage the appropriate stakeholders to provide input on the gaps to prioritize targeting.

Cocreate Knowledge

Our third goal was to cocreate knowledge regarding the care of patients with long COVID. To accomplish this, our structured meetings and communication pathways invited members to share experiences on the who (delivers and receives care), what (type of care or HCPs), when (identification of post-COVID and access), and how (eg, telehealth) of care to patients post-COVID. As part of the workgroup, we identified and shared resources on standardized, facility-level practices to reduce variability across the VHA system. These resources included intake/assessment forms, care processes, and batteries of tests/measures used for screening and assessment. The knowledge obtained from outside the CoP and cocreated within is being used to inform data-driven tools to support and evaluate care for patients with long COVID. As such, members of the workgroup are in the formative stages of participating in quality improvement innovation pilots to test technologies and processes designed to improve and validate long COVID care pathways. These technologies include screening tools, clinical decision support tools, and population health management technologies. In addition, we are developing a formal collaboration with the VHA Office of Research and Development to create standardized intake forms across VHA long COVID clinics to facilitate both clinical monitoring and research.

Surveys

The US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office collaborated with our workgroup to draft an initial set of survey questions designed to understand how each VHA facility defines, identifies, and provides care to veterans experiencing post-COVID sequalae. The 41-question survey was distributed through regional directors and chief medical officers at 139 VHA facilities in August 2021. One hundred nineteen responses (86%) were received. Sixteen facilities indicated they had established programs and 26 facilities were considering a program. Our CoP had representation from the 16 facilities with established programs indicating the deep and well-connected nature of our grassroots efforts to bring together stakeholders to learn as part of a CoP.

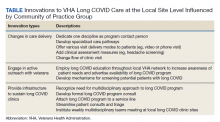

A separate, follow-up survey generated responses from 18 facilities and identified the need to capture evolving innovations and to develop smaller workstreams (eg, best practices, electronic documentation templates, pathway for referrals, veteran engagement, outcome measures). The survey not only exposed ongoing challenges to providing long COVID care, but importantly, outlined the ways in which CoP members were leveraging community knowledge and resources to inform innovations and processes of care changes at their specific sites. Fourteen of 18 facilities with long COVID programs in place explicitly identified the CoP as a resource they have found most beneficial when employing such innovations. Specific innovations reported included changes in care delivery, engagement in active outreach with veterans and local facility, and infrastructure development to sustain local long COVID clinics (Table).

Future Directions

Our CoP strives to contribute to an evidence base for long COVID care. At the system level, the CoP has the potential to impact access and continuity of care by identifying appropriate processes and ensuring that VHA patients receive outreach and an opportunity for post-COVID care. Comprehensive care requires input from HCP, clinical leadership, and operations levels. In this sense, our CoP provides an opportunity for diverse stakeholders to come together, discuss barriers to screening and delivering post-COVID care, and create an action plan to remove or lessen such barriers.18 Part of the process to remove barriers is to identify and support efficient resource allocation. Our CoP has worked to address issues in resource allocation (eg, space, personnel) for post-COVID care. For example, one facility is currently implementing interdisciplinary virtual post-COVID care. Another facility identified and restructured working assignments for psychologists who served in different capacities throughout the system to fill the need within the long COVID team.

At the HCP level, the CoP is currently developing workshops, media campaigns, written clinical resources, skills training, publications, and webinars/seminars with continuing medical education credits.19 The CoP may also provide learning and growth opportunities, such as clinical or VHA operational fellowships and research grants.

We are still in the formative stages of post-COVID care and future efforts will explore patient-centered outcomes. We are drawing on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidance for evaluating patients with long COVID symptoms and examining the feasibility within VHA, as well as patient perspectives on post-COVID sequalae, to ensure we are selecting assessments that measure patient-centered constructs.18

Conclusions

A VHA-wide LHS approach is identifying issues related to the identification, delivery, and evaluation of long COVID care. This long COVID CoP has developed an infrastructure for communication, identified gaps in care, and cocreated knowledge related to best current practices for post-COVID care. This work is contributing to systemwide LHS efforts dedicated to creating a culture of quality care and innovation and is a process that is transferrable to other areas of care in the VHA, as well as other health care systems. The LHS approach continues to be highly relevant as we persist through the COVID-19 pandemic and reimagine a postpandemic world.

Acknowledg

We thank all the members of the Veterans Health Administration long COVID Community of Practice who participate in the meetings and contribute to the sharing and spread of knowledge.

1. Sivan M, Halpin S, Hollingworth L, Snook N, Hickman K, Clifton I. Development of an integrated rehabilitation pathway for individuals recovering from COVID-19 in the community. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(8):jrm00089. doi:10.2340/16501977-2727

2. Understanding the long-term health effects of COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100586. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100586

3. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. Published online August 11, 2020:m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026

4. Iwua CJ, Iwu CD, Wiysonge CS. The occurrence of long COVID: a rapid review. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.65.27366

5. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

6. Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(8):1613-1620. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x

7. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

8. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259-264. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9

9. Ayoubkhani D, Bermingham C, Pouwels KB, et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. BMJ. 2022;377:e069676. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-069676

10. Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine, Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, eds. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. doi:10.17226/11903

11. Romanelli RJ, Azar KMJ, Sudat S, Hung D, Frosch DL, Pressman AR. Learning health system in crisis: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):171-176. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.10.004

12. Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

13. Kitson A, Straus SE. The knowledge-to-action cycle: identifying the gaps. CMAJ. 2010;182(2):E73-77. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081231

14. Greer N, Bart B, Billington C, et al. COVID-19 post-acute care major organ damage: a living rapid review. Updated September 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid-organ-damage.pdf

15. Sharpe JA, Burke C, Gordon AM, et al. COVID-19 post-hospitalization health care utilization: a living review. Updated February 2022. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid19-post-hosp.pdf

16. Bested AC, Marshall LM. Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30(4):223-249. doi:10.1515/reveh-2015-0026

17. Yancey JR, Thomas SM. Chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(8):741-746.

18. Kotter JP, Cohen DS. Change Leadership The Kotter Collection. Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

19. Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102-111. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA)—along with systems across the world—has spent the past 2 years continuously adapting to meet the emerging needs of persons infected with COVID-19. With the development of effective vaccines and global efforts to mitigate transmission, attention has now shifted to long COVID care as the need for further outpatient health care becomes increasingly apparent.1,2

Background

Multiple terms describe the lingering, multisystem sequelae of COVID-19 that last longer than 4 weeks: long COVID, postacute COVID-19 syndrome, post-COVID condition, postacute sequalae of COVID-19, and COVID long hauler.1,3 Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cough, sleep disorders, brain fog or cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, pain, and changes in taste or smell that impact a person’s functioning.4,5 The multisystem nature of the postacute course of COVID-19 necessitates an interdisciplinary approach to devise comprehensive and individualized care plans.6-9 Research is needed to better understand this postacute state (eg, prevalence, underlying effects, characteristics of those who experience long COVID) to establish and evaluate cost-effective treatment approaches.

Many patients who are experiencing symptoms beyond the acute course of COVID-19 have been referred to general outpatient clinics or home health, which may lack the capacity and knowledge of this novel disease to effectively manage complex long COVID cases.2,3 To address this growing need, clinicians and leadership across a variety of disciplines and settings in the VHA created a community of practice (CoP) to create a mechanism for cross-facility communication, identify gaps in long COVID care and research, and cocreate knowledge on best practices for care delivery.

In this spirit, we are embracing a learning health system (LHS) approach that uses rapid-cycle methods to integrate data and real-world experience to iteratively evaluate and adapt models of long COVID care.10 Our clinically identified and data-driven objective is to provide high value health care to patients with long COVID sequalae by creating a framework to learn about this novel condition and develop innovative care models. This article provides an overview of our emerging LHS approach to the study of long COVID care that is fostering innovation and adaptability within the VHA. We describe 3 aspects of our engagement approach central to LHS: the ongoing development of a long COVID CoP dedicated to iteratively informing the bidirectional cycle of data from practice to research, results of a broad environmental scan of VHA long COVID care, and results of a survey administered to CoP members to inform ongoing needs of the community and identify early successful outcomes from participation.

Learning Health System Approach

The VHA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States serving more than 9 million veterans.11 Since 2017, the VHA has articulated a vision to become an LHS that informs and improves patient-centered care through practice-based and data-driven research (eAppendix).12 During the early COVID-19 pandemic, an LHS approach in the VHA was critical to rapidly establishing a data infrastructure for disease surveillance, coordinating data-driven solutions, leveraging use of technology, collaborating across the globe to identify best practices, and implementing systematic responses (eg, policies, workforce adjustments).

Our long COVID CoP was developed as clinical observations and ongoing conversations with stakeholders (eg, veterans, health care practitioners [HCPs], leadership) identified a need to effectively identify and treat the growing number of veterans with long COVID. This clinical issue is compounded by the limited but emerging evidence on the clinical presentation of prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, treatment, and subsequent care pathways. The VHA’s efforts and lessons learned within the lens of an LHS are applicable to other systems confronting the complex identification and management of patients with persistent and encumbering long COVID symptoms. The VHA is building upon the LHS approach to proactively prepare for and address future clinical or public health challenges that require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient/family centeredness.11

Community of Practice

As of January 25, 2022, our workgroup consisted of 128 VHA employees representing 29 VHA medical centers. Members of the multidisciplinary workgroup have diverse backgrounds with HCPs from primary care (eg, physicians, nurse practitioners), rehabilitation (eg, physical therapists), specialty care (eg, pulmonologists, physiatrists), mental health (eg, psychologists), and complementary and integrated health/Whole Health services (eg, practitoners of services such as yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, acupuncture). Members also include clinical, operations, and research leadership at local, regional, and national VHA levels. Our first objective as a large, diverse group was to establish shared goals, which included: (1) determining efficient communication pathways; (2) identifying gaps in care or research; and (3) cocreating knowledge to provide solutions to identified gaps.

Communication Mechanisms

Our first goal was to create an efficient mechanism for cross-facility communication. The initial CoP was formed in April 2021 and the first virtual meeting focused on reaching a consensus regarding the best way to communicate and proceed. We agreed to convene weekly at a consistent time, created a standard agenda template, and elected a lead facilitator of meeting proceedings. In addition, a member of the CoP recorded and took extensive meeting notes, which were later distributed to the entire CoP to accommodate varying schedules and ability to attend live meetings. Approximately 20 to 30 participants attend the meetings in real-time.

To consolidate working documents, information, and resources in one location, we created a platform to communicate via a Microsoft Teams channel. All CoP members are given access to the folders and allowed to add to the growing library of resources. Resources include clinical assessment and note templates for electronic documentation of care, site-specific process maps, relevant literature on screening and interventions identified by practice members, and meeting notes along with the recordings. A chat feature alerts CoP members to questions posed by other members. Any resources or information shared on the chat discussion are curated by CoP leaders to disseminate to all members. Importantly, this platform allowed us to communicate efficiently within the VHA organization by creating a centralized space for documents and the ability to correspond with all or select members of the CoP. Additional VHA employees can easily be referred and request access.

To increase awareness of the CoP, expand reach, and diversify perspectives, every participant was encouraged to invite colleagues and stakeholders with interest or experience in long COVID care to join. While patients are not included in this CoP, we are working closely with the VHA user experience workgroup (many members overlap) that is gathering patient and caregiver perspectives on their COVID-19 experience and long COVID care. Concurrently, CoP members and leadership facilitate communication and set up formal collaborations with other non-VHA health care systems to create an intersystem network of collaboration for long COVID care. This approach further enhances the speed at which we can work together to share lessons learned and stay up-to-date on emerging evidence surrounding long COVID care.

Identifying Gaps in Care and Research

Our second goal was to identify gaps in care or knowledge to inform future research and quality improvement initiatives, while also creating a foundation to cocreate knowledge about safe, effective care management of the novel long COVID sequelae. To translate knowledge, we must first identify and understand the gaps between the current, best available evidence and current care practices or policies impacting that delivery.13 As such, the structured meeting agenda and facilitated meeting discussions focused on understanding current clinical decision making and the evidence base. We shared VHA evidence synthesis reports and living rapid reviews on complications following COVID-19 illness (ie, major organ damage and posthospitalization health care use) that provided an objective evidence base on common long COVID complications.14,15

Since long COVID is a novel condition, we drew from literature in similar patient populations and translated that information in the context of our current knowledge of this unique syndrome. For example, we discussed the predominant and persistent symptom of fatigue post-COVID.5 In particular, the CoP discussed challenges in identifying and treating post-COVID fatigue, which is often a vague symptom with multiple or interacting etiologies that require a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach. As such, we reviewed, adapted, and translated identification and treatment strategies from the literature on chronic fatigue syndrome to patients with post-COVID syndrome.16,17 We continue to work collaboratively and engage the appropriate stakeholders to provide input on the gaps to prioritize targeting.

Cocreate Knowledge

Our third goal was to cocreate knowledge regarding the care of patients with long COVID. To accomplish this, our structured meetings and communication pathways invited members to share experiences on the who (delivers and receives care), what (type of care or HCPs), when (identification of post-COVID and access), and how (eg, telehealth) of care to patients post-COVID. As part of the workgroup, we identified and shared resources on standardized, facility-level practices to reduce variability across the VHA system. These resources included intake/assessment forms, care processes, and batteries of tests/measures used for screening and assessment. The knowledge obtained from outside the CoP and cocreated within is being used to inform data-driven tools to support and evaluate care for patients with long COVID. As such, members of the workgroup are in the formative stages of participating in quality improvement innovation pilots to test technologies and processes designed to improve and validate long COVID care pathways. These technologies include screening tools, clinical decision support tools, and population health management technologies. In addition, we are developing a formal collaboration with the VHA Office of Research and Development to create standardized intake forms across VHA long COVID clinics to facilitate both clinical monitoring and research.

Surveys

The US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office collaborated with our workgroup to draft an initial set of survey questions designed to understand how each VHA facility defines, identifies, and provides care to veterans experiencing post-COVID sequalae. The 41-question survey was distributed through regional directors and chief medical officers at 139 VHA facilities in August 2021. One hundred nineteen responses (86%) were received. Sixteen facilities indicated they had established programs and 26 facilities were considering a program. Our CoP had representation from the 16 facilities with established programs indicating the deep and well-connected nature of our grassroots efforts to bring together stakeholders to learn as part of a CoP.

A separate, follow-up survey generated responses from 18 facilities and identified the need to capture evolving innovations and to develop smaller workstreams (eg, best practices, electronic documentation templates, pathway for referrals, veteran engagement, outcome measures). The survey not only exposed ongoing challenges to providing long COVID care, but importantly, outlined the ways in which CoP members were leveraging community knowledge and resources to inform innovations and processes of care changes at their specific sites. Fourteen of 18 facilities with long COVID programs in place explicitly identified the CoP as a resource they have found most beneficial when employing such innovations. Specific innovations reported included changes in care delivery, engagement in active outreach with veterans and local facility, and infrastructure development to sustain local long COVID clinics (Table).

Future Directions

Our CoP strives to contribute to an evidence base for long COVID care. At the system level, the CoP has the potential to impact access and continuity of care by identifying appropriate processes and ensuring that VHA patients receive outreach and an opportunity for post-COVID care. Comprehensive care requires input from HCP, clinical leadership, and operations levels. In this sense, our CoP provides an opportunity for diverse stakeholders to come together, discuss barriers to screening and delivering post-COVID care, and create an action plan to remove or lessen such barriers.18 Part of the process to remove barriers is to identify and support efficient resource allocation. Our CoP has worked to address issues in resource allocation (eg, space, personnel) for post-COVID care. For example, one facility is currently implementing interdisciplinary virtual post-COVID care. Another facility identified and restructured working assignments for psychologists who served in different capacities throughout the system to fill the need within the long COVID team.

At the HCP level, the CoP is currently developing workshops, media campaigns, written clinical resources, skills training, publications, and webinars/seminars with continuing medical education credits.19 The CoP may also provide learning and growth opportunities, such as clinical or VHA operational fellowships and research grants.

We are still in the formative stages of post-COVID care and future efforts will explore patient-centered outcomes. We are drawing on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidance for evaluating patients with long COVID symptoms and examining the feasibility within VHA, as well as patient perspectives on post-COVID sequalae, to ensure we are selecting assessments that measure patient-centered constructs.18

Conclusions

A VHA-wide LHS approach is identifying issues related to the identification, delivery, and evaluation of long COVID care. This long COVID CoP has developed an infrastructure for communication, identified gaps in care, and cocreated knowledge related to best current practices for post-COVID care. This work is contributing to systemwide LHS efforts dedicated to creating a culture of quality care and innovation and is a process that is transferrable to other areas of care in the VHA, as well as other health care systems. The LHS approach continues to be highly relevant as we persist through the COVID-19 pandemic and reimagine a postpandemic world.

Acknowledg

We thank all the members of the Veterans Health Administration long COVID Community of Practice who participate in the meetings and contribute to the sharing and spread of knowledge.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA)—along with systems across the world—has spent the past 2 years continuously adapting to meet the emerging needs of persons infected with COVID-19. With the development of effective vaccines and global efforts to mitigate transmission, attention has now shifted to long COVID care as the need for further outpatient health care becomes increasingly apparent.1,2

Background

Multiple terms describe the lingering, multisystem sequelae of COVID-19 that last longer than 4 weeks: long COVID, postacute COVID-19 syndrome, post-COVID condition, postacute sequalae of COVID-19, and COVID long hauler.1,3 Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, cough, sleep disorders, brain fog or cognitive dysfunction, depression, anxiety, pain, and changes in taste or smell that impact a person’s functioning.4,5 The multisystem nature of the postacute course of COVID-19 necessitates an interdisciplinary approach to devise comprehensive and individualized care plans.6-9 Research is needed to better understand this postacute state (eg, prevalence, underlying effects, characteristics of those who experience long COVID) to establish and evaluate cost-effective treatment approaches.

Many patients who are experiencing symptoms beyond the acute course of COVID-19 have been referred to general outpatient clinics or home health, which may lack the capacity and knowledge of this novel disease to effectively manage complex long COVID cases.2,3 To address this growing need, clinicians and leadership across a variety of disciplines and settings in the VHA created a community of practice (CoP) to create a mechanism for cross-facility communication, identify gaps in long COVID care and research, and cocreate knowledge on best practices for care delivery.

In this spirit, we are embracing a learning health system (LHS) approach that uses rapid-cycle methods to integrate data and real-world experience to iteratively evaluate and adapt models of long COVID care.10 Our clinically identified and data-driven objective is to provide high value health care to patients with long COVID sequalae by creating a framework to learn about this novel condition and develop innovative care models. This article provides an overview of our emerging LHS approach to the study of long COVID care that is fostering innovation and adaptability within the VHA. We describe 3 aspects of our engagement approach central to LHS: the ongoing development of a long COVID CoP dedicated to iteratively informing the bidirectional cycle of data from practice to research, results of a broad environmental scan of VHA long COVID care, and results of a survey administered to CoP members to inform ongoing needs of the community and identify early successful outcomes from participation.

Learning Health System Approach

The VHA is one of the largest integrated health care systems in the United States serving more than 9 million veterans.11 Since 2017, the VHA has articulated a vision to become an LHS that informs and improves patient-centered care through practice-based and data-driven research (eAppendix).12 During the early COVID-19 pandemic, an LHS approach in the VHA was critical to rapidly establishing a data infrastructure for disease surveillance, coordinating data-driven solutions, leveraging use of technology, collaborating across the globe to identify best practices, and implementing systematic responses (eg, policies, workforce adjustments).

Our long COVID CoP was developed as clinical observations and ongoing conversations with stakeholders (eg, veterans, health care practitioners [HCPs], leadership) identified a need to effectively identify and treat the growing number of veterans with long COVID. This clinical issue is compounded by the limited but emerging evidence on the clinical presentation of prolonged COVID-19 symptoms, treatment, and subsequent care pathways. The VHA’s efforts and lessons learned within the lens of an LHS are applicable to other systems confronting the complex identification and management of patients with persistent and encumbering long COVID symptoms. The VHA is building upon the LHS approach to proactively prepare for and address future clinical or public health challenges that require cross-system and sector collaborations, expediency, inclusivity, and patient/family centeredness.11

Community of Practice

As of January 25, 2022, our workgroup consisted of 128 VHA employees representing 29 VHA medical centers. Members of the multidisciplinary workgroup have diverse backgrounds with HCPs from primary care (eg, physicians, nurse practitioners), rehabilitation (eg, physical therapists), specialty care (eg, pulmonologists, physiatrists), mental health (eg, psychologists), and complementary and integrated health/Whole Health services (eg, practitoners of services such as yoga, tai chi, mindfulness, acupuncture). Members also include clinical, operations, and research leadership at local, regional, and national VHA levels. Our first objective as a large, diverse group was to establish shared goals, which included: (1) determining efficient communication pathways; (2) identifying gaps in care or research; and (3) cocreating knowledge to provide solutions to identified gaps.

Communication Mechanisms

Our first goal was to create an efficient mechanism for cross-facility communication. The initial CoP was formed in April 2021 and the first virtual meeting focused on reaching a consensus regarding the best way to communicate and proceed. We agreed to convene weekly at a consistent time, created a standard agenda template, and elected a lead facilitator of meeting proceedings. In addition, a member of the CoP recorded and took extensive meeting notes, which were later distributed to the entire CoP to accommodate varying schedules and ability to attend live meetings. Approximately 20 to 30 participants attend the meetings in real-time.

To consolidate working documents, information, and resources in one location, we created a platform to communicate via a Microsoft Teams channel. All CoP members are given access to the folders and allowed to add to the growing library of resources. Resources include clinical assessment and note templates for electronic documentation of care, site-specific process maps, relevant literature on screening and interventions identified by practice members, and meeting notes along with the recordings. A chat feature alerts CoP members to questions posed by other members. Any resources or information shared on the chat discussion are curated by CoP leaders to disseminate to all members. Importantly, this platform allowed us to communicate efficiently within the VHA organization by creating a centralized space for documents and the ability to correspond with all or select members of the CoP. Additional VHA employees can easily be referred and request access.

To increase awareness of the CoP, expand reach, and diversify perspectives, every participant was encouraged to invite colleagues and stakeholders with interest or experience in long COVID care to join. While patients are not included in this CoP, we are working closely with the VHA user experience workgroup (many members overlap) that is gathering patient and caregiver perspectives on their COVID-19 experience and long COVID care. Concurrently, CoP members and leadership facilitate communication and set up formal collaborations with other non-VHA health care systems to create an intersystem network of collaboration for long COVID care. This approach further enhances the speed at which we can work together to share lessons learned and stay up-to-date on emerging evidence surrounding long COVID care.

Identifying Gaps in Care and Research

Our second goal was to identify gaps in care or knowledge to inform future research and quality improvement initiatives, while also creating a foundation to cocreate knowledge about safe, effective care management of the novel long COVID sequelae. To translate knowledge, we must first identify and understand the gaps between the current, best available evidence and current care practices or policies impacting that delivery.13 As such, the structured meeting agenda and facilitated meeting discussions focused on understanding current clinical decision making and the evidence base. We shared VHA evidence synthesis reports and living rapid reviews on complications following COVID-19 illness (ie, major organ damage and posthospitalization health care use) that provided an objective evidence base on common long COVID complications.14,15

Since long COVID is a novel condition, we drew from literature in similar patient populations and translated that information in the context of our current knowledge of this unique syndrome. For example, we discussed the predominant and persistent symptom of fatigue post-COVID.5 In particular, the CoP discussed challenges in identifying and treating post-COVID fatigue, which is often a vague symptom with multiple or interacting etiologies that require a comprehensive, interdisciplinary approach. As such, we reviewed, adapted, and translated identification and treatment strategies from the literature on chronic fatigue syndrome to patients with post-COVID syndrome.16,17 We continue to work collaboratively and engage the appropriate stakeholders to provide input on the gaps to prioritize targeting.

Cocreate Knowledge

Our third goal was to cocreate knowledge regarding the care of patients with long COVID. To accomplish this, our structured meetings and communication pathways invited members to share experiences on the who (delivers and receives care), what (type of care or HCPs), when (identification of post-COVID and access), and how (eg, telehealth) of care to patients post-COVID. As part of the workgroup, we identified and shared resources on standardized, facility-level practices to reduce variability across the VHA system. These resources included intake/assessment forms, care processes, and batteries of tests/measures used for screening and assessment. The knowledge obtained from outside the CoP and cocreated within is being used to inform data-driven tools to support and evaluate care for patients with long COVID. As such, members of the workgroup are in the formative stages of participating in quality improvement innovation pilots to test technologies and processes designed to improve and validate long COVID care pathways. These technologies include screening tools, clinical decision support tools, and population health management technologies. In addition, we are developing a formal collaboration with the VHA Office of Research and Development to create standardized intake forms across VHA long COVID clinics to facilitate both clinical monitoring and research.

Surveys

The US Department of Veterans Affairs Central Office collaborated with our workgroup to draft an initial set of survey questions designed to understand how each VHA facility defines, identifies, and provides care to veterans experiencing post-COVID sequalae. The 41-question survey was distributed through regional directors and chief medical officers at 139 VHA facilities in August 2021. One hundred nineteen responses (86%) were received. Sixteen facilities indicated they had established programs and 26 facilities were considering a program. Our CoP had representation from the 16 facilities with established programs indicating the deep and well-connected nature of our grassroots efforts to bring together stakeholders to learn as part of a CoP.

A separate, follow-up survey generated responses from 18 facilities and identified the need to capture evolving innovations and to develop smaller workstreams (eg, best practices, electronic documentation templates, pathway for referrals, veteran engagement, outcome measures). The survey not only exposed ongoing challenges to providing long COVID care, but importantly, outlined the ways in which CoP members were leveraging community knowledge and resources to inform innovations and processes of care changes at their specific sites. Fourteen of 18 facilities with long COVID programs in place explicitly identified the CoP as a resource they have found most beneficial when employing such innovations. Specific innovations reported included changes in care delivery, engagement in active outreach with veterans and local facility, and infrastructure development to sustain local long COVID clinics (Table).

Future Directions

Our CoP strives to contribute to an evidence base for long COVID care. At the system level, the CoP has the potential to impact access and continuity of care by identifying appropriate processes and ensuring that VHA patients receive outreach and an opportunity for post-COVID care. Comprehensive care requires input from HCP, clinical leadership, and operations levels. In this sense, our CoP provides an opportunity for diverse stakeholders to come together, discuss barriers to screening and delivering post-COVID care, and create an action plan to remove or lessen such barriers.18 Part of the process to remove barriers is to identify and support efficient resource allocation. Our CoP has worked to address issues in resource allocation (eg, space, personnel) for post-COVID care. For example, one facility is currently implementing interdisciplinary virtual post-COVID care. Another facility identified and restructured working assignments for psychologists who served in different capacities throughout the system to fill the need within the long COVID team.

At the HCP level, the CoP is currently developing workshops, media campaigns, written clinical resources, skills training, publications, and webinars/seminars with continuing medical education credits.19 The CoP may also provide learning and growth opportunities, such as clinical or VHA operational fellowships and research grants.

We are still in the formative stages of post-COVID care and future efforts will explore patient-centered outcomes. We are drawing on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidance for evaluating patients with long COVID symptoms and examining the feasibility within VHA, as well as patient perspectives on post-COVID sequalae, to ensure we are selecting assessments that measure patient-centered constructs.18

Conclusions

A VHA-wide LHS approach is identifying issues related to the identification, delivery, and evaluation of long COVID care. This long COVID CoP has developed an infrastructure for communication, identified gaps in care, and cocreated knowledge related to best current practices for post-COVID care. This work is contributing to systemwide LHS efforts dedicated to creating a culture of quality care and innovation and is a process that is transferrable to other areas of care in the VHA, as well as other health care systems. The LHS approach continues to be highly relevant as we persist through the COVID-19 pandemic and reimagine a postpandemic world.

Acknowledg

We thank all the members of the Veterans Health Administration long COVID Community of Practice who participate in the meetings and contribute to the sharing and spread of knowledge.

1. Sivan M, Halpin S, Hollingworth L, Snook N, Hickman K, Clifton I. Development of an integrated rehabilitation pathway for individuals recovering from COVID-19 in the community. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(8):jrm00089. doi:10.2340/16501977-2727

2. Understanding the long-term health effects of COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100586. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100586

3. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. Published online August 11, 2020:m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026

4. Iwua CJ, Iwu CD, Wiysonge CS. The occurrence of long COVID: a rapid review. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.65.27366

5. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

6. Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(8):1613-1620. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x

7. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

8. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259-264. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9

9. Ayoubkhani D, Bermingham C, Pouwels KB, et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. BMJ. 2022;377:e069676. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-069676

10. Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine, Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, eds. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. doi:10.17226/11903

11. Romanelli RJ, Azar KMJ, Sudat S, Hung D, Frosch DL, Pressman AR. Learning health system in crisis: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):171-176. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.10.004

12. Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

13. Kitson A, Straus SE. The knowledge-to-action cycle: identifying the gaps. CMAJ. 2010;182(2):E73-77. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081231

14. Greer N, Bart B, Billington C, et al. COVID-19 post-acute care major organ damage: a living rapid review. Updated September 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid-organ-damage.pdf

15. Sharpe JA, Burke C, Gordon AM, et al. COVID-19 post-hospitalization health care utilization: a living review. Updated February 2022. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid19-post-hosp.pdf

16. Bested AC, Marshall LM. Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30(4):223-249. doi:10.1515/reveh-2015-0026

17. Yancey JR, Thomas SM. Chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(8):741-746.

18. Kotter JP, Cohen DS. Change Leadership The Kotter Collection. Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

19. Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102-111. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673

1. Sivan M, Halpin S, Hollingworth L, Snook N, Hickman K, Clifton I. Development of an integrated rehabilitation pathway for individuals recovering from COVID-19 in the community. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52(8):jrm00089. doi:10.2340/16501977-2727

2. Understanding the long-term health effects of COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26:100586. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100586

3. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, Buxton M, Husain L. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ. Published online August 11, 2020:m3026. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3026

4. Iwua CJ, Iwu CD, Wiysonge CS. The occurrence of long COVID: a rapid review. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38. doi:10.11604/pamj.2021.38.65.27366

5. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F; Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603-605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

6. Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post-COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32(8):1613-1620. doi:10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x

7. Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01689-3

8. Al-Aly Z, Xie Y, Bowe B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature. 2021;594:259-264. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03553-9

9. Ayoubkhani D, Bermingham C, Pouwels KB, et al. Trajectory of long covid symptoms after covid-19 vaccination: community based cohort study. BMJ. 2022;377:e069676. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-069676

10. Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine, Olsen L, Aisner D, McGinnis JM, eds. The Learning Healthcare System: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. doi:10.17226/11903

11. Romanelli RJ, Azar KMJ, Sudat S, Hung D, Frosch DL, Pressman AR. Learning health system in crisis: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2021;5(1):171-176. doi:10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.10.004

12. Atkins D, Kilbourne AM, Shulkin D. Moving from discovery to system-wide change: the role of research in a learning health care system: experience from three decades of health systems research in the Veterans Health Administration. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:467-487. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044255

13. Kitson A, Straus SE. The knowledge-to-action cycle: identifying the gaps. CMAJ. 2010;182(2):E73-77. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081231

14. Greer N, Bart B, Billington C, et al. COVID-19 post-acute care major organ damage: a living rapid review. Updated September 2021. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid-organ-damage.pdf

15. Sharpe JA, Burke C, Gordon AM, et al. COVID-19 post-hospitalization health care utilization: a living review. Updated February 2022. Accessed May 31, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/covid19-post-hosp.pdf

16. Bested AC, Marshall LM. Review of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: an evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management by clinicians. Rev Environ Health. 2015;30(4):223-249. doi:10.1515/reveh-2015-0026

17. Yancey JR, Thomas SM. Chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86(8):741-746.

18. Kotter JP, Cohen DS. Change Leadership The Kotter Collection. Harvard Business Review Press; 2014.

19. Brownson RC, Eyler AA, Harris JK, Moore JB, Tabak RG. Getting the word out: new approaches for disseminating public health science. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(2):102-111. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000673