User login

Atypical Presentation of Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris: Challenges in Diagnosis and Management

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

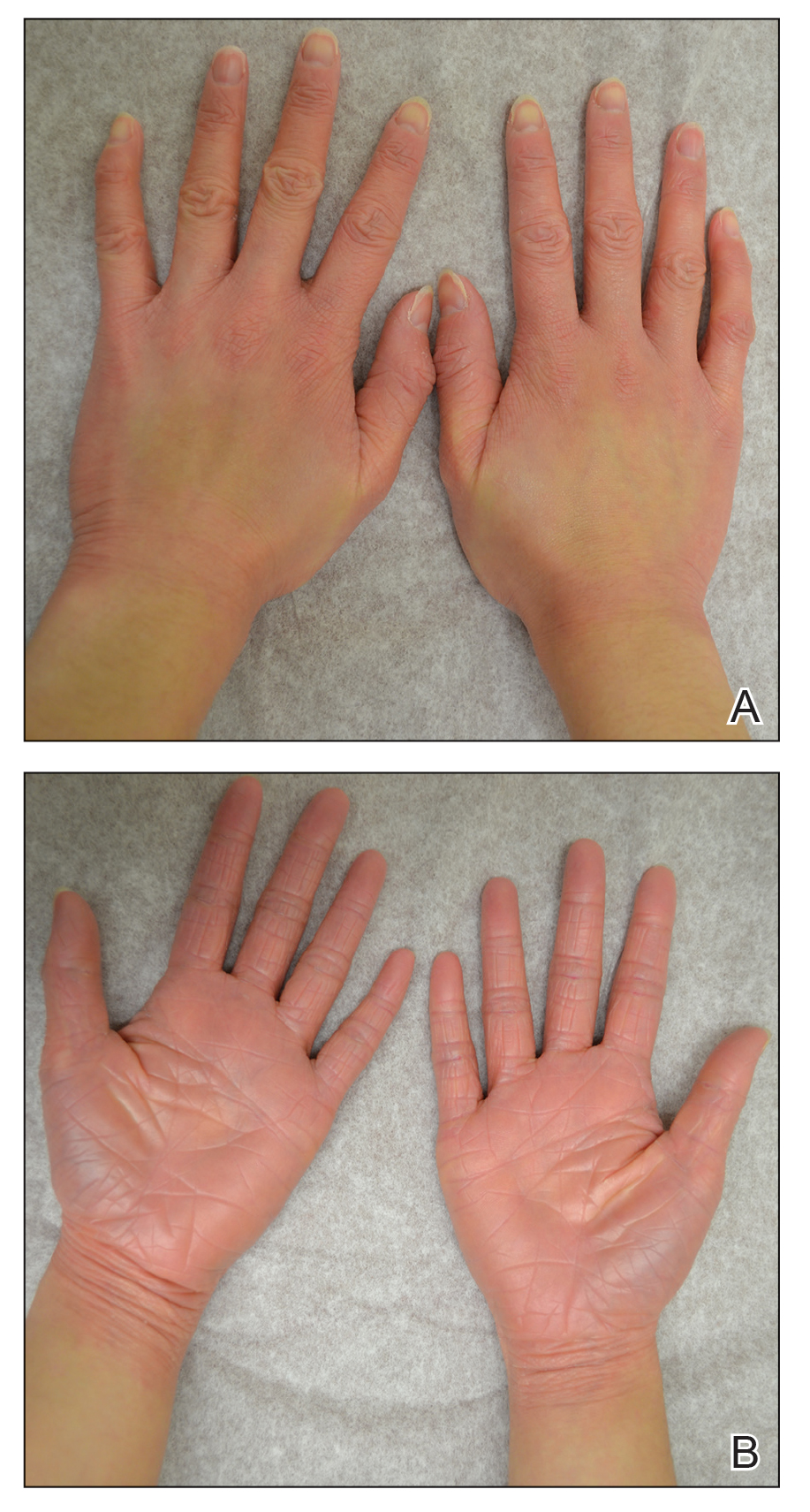

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

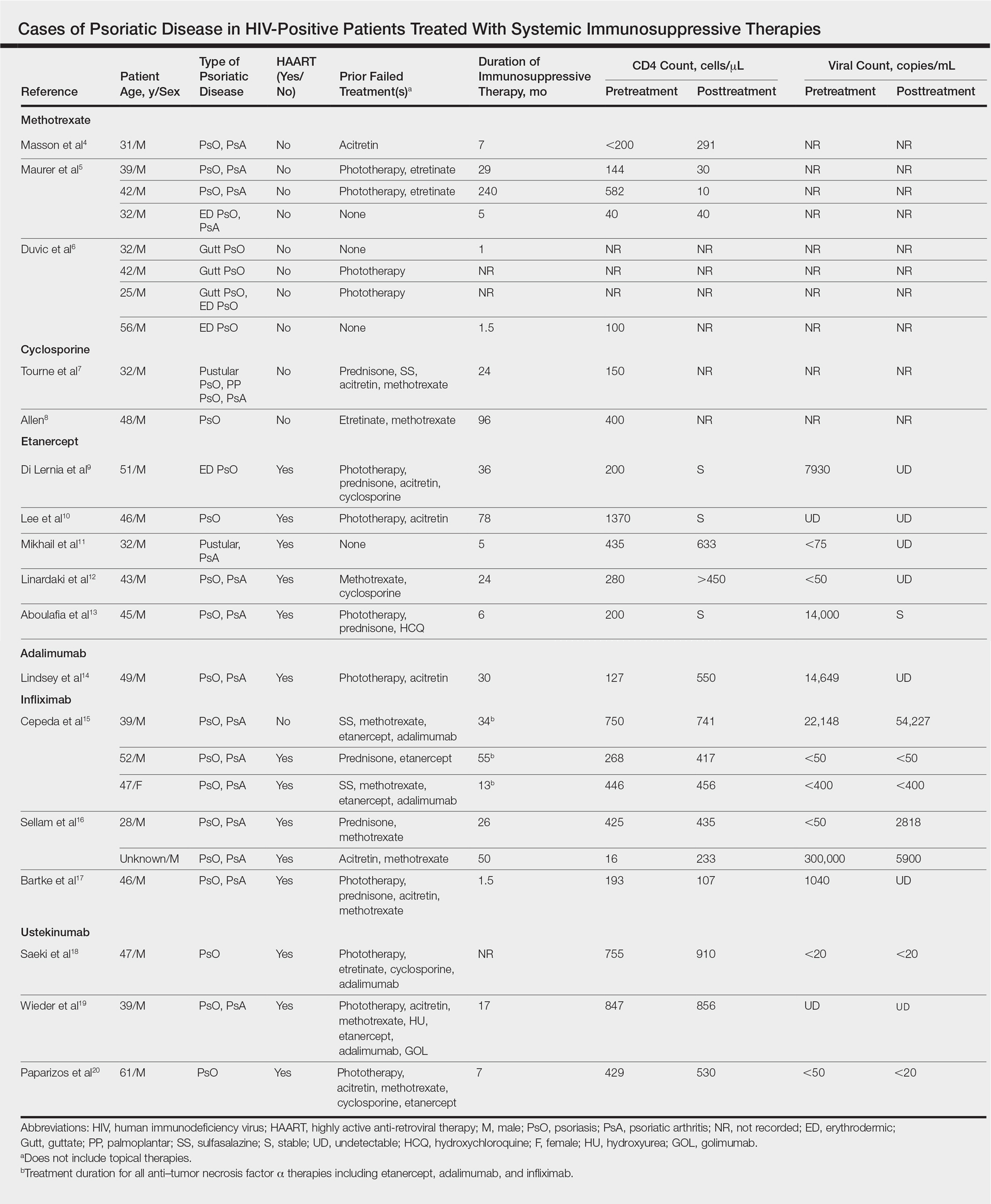

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

To the Editor:

Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.1 In the United States, an incidence of 1 in 3500to 5000 patients presenting to dermatology clinics has been reported.2 Pityriasis rubra pilaris has several subtypes and variability in presentation that can make accurate and timely diagnosis challenging.3-5 Herein, we present a case of PRP with complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

A 22-year-old woman presented with symmetrical, well-demarcated, hyperkeratotic, erythematous plaques with a carnauba wax–like appearance on the palms (Figure 1), soles, elbows, and trunk covering approximately 5% of the body surface area. Two weeks prior to presentation, she experienced an upper respiratory tract infection without any treatment and subsequently developed redness on the palms, which became very hard and scaly. The redness then spread to the elbows, soles, and trunk. She reported itching as well as pain in areas of fissuring. Hand mobility became restricted due to thick scale.

The patient’s medical history was notable for suspected psoriasis 9 years prior, but there were no records or biopsy reports that could be obtained to confirm the diagnosis. She also reported a similar skin condition in her father, which also was diagnosed as psoriasis, but this diagnosis could not be verified.

Although the morphology of the lesions was most consistent with localized PRP, atypical psoriasis, palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK), and erythroderma progressive symmetrica (EPS) also were considered given the personal and family history of suspected psoriasis. A biopsy could not be obtained due to an insurance issue. She was started on clobetasol cream 0.05% and ointment. At 2-week follow-up, her condition remained unchanged. Empiric systemic treatment was discussed, which would potentially work for diagnoses of both PRP and psoriasis. Due to the history of psoriasis and level of discomfort, cyclosporine 300 mg once daily was started to gain rapid control of the disease. Methotrexate also was considered due to its efficacy and economic considerations but was not selected due to patient concerns about the medication.

After 10 weeks of cyclosporine treatment, our patient showed some improvement of the skin with decreased scale and flattening of plaques but not complete resolution. At this point, a biopsy was able to be obtained with prior authorization. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the right flank demonstrated a psoriasiform and papillated epidermis with multifocally capped, compact parakeratosis and minimal lymphocytic infiltrate consistent with PRP. Although EPS also was on the histologic differential, clinical history was more consistent with a diagnosis of PRP. There was some minimal improvement with cyclosporine, but with the diagnosis of PRP confirmed, a systemic retinoid became the treatment of choice. Although acitretin is the preferred treatment for PRP, given that pregnancy would be contraindicated during and for 3 years following acitretin therapy, a trial of isotretinoin 40 mg once daily was started due to its shorter half-life compared to acitretin and was continued for 3 months (Figure 2).6,7

The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations. This case was an atypical presentation of PRP with several learning points, as our patient’s condition did not fit perfectly into any of the 6 types of PRP. The age of onset was atypical at 22 years old. Pityriasis rubra pilaris typically presents with a bimodal age distribution, appearing either in the first decade or the fifth to sixth decades of life.3,8 Her clinical presentation was atypical for adult-onset types I and II, which typically present with cephalocaudal progression or ichthyosiform dermatitis, respectively. Her presentation also was atypical for juvenile onset in types III, IV, and V, which tend to present in younger children and with different physical examination findings.3,8

The morphology of our patient’s lesions also was atypical for PRP, PPK, EPS, and psoriasis. The clinical presentation had features of these entities with erythema, fissuring, xerosis, carnauba wax–like appearance, symmetric scale, and well-demarcated plaques. Although these findings are not mutually exclusive, their combined presentation is atypical. Coupled with the ambiguous family history of similar skin disease in the patient’s father, the discussion of genodermatoses, particularly PPK, further confounded the diagnosis.4,9 When evaluating for PRP, especially with any family history of skin conditions, genodermatoses should be considered. Furthermore, our patient’s remote and unverifiable history of psoriasis serves as a cautionary reminder that prior diagnoses and medical history always should be reasonably scrutinized. Additionally, a drug-induced PRP eruption also should be considered. Although our patient received no medical treatment for the upper respiratory tract infection prior to the onset of PRP, there have been several reports of drug-induced PRP.10-12

The therapeutic challenge in this case is one that often is encountered in clinical practice. The health care system often may pose a barrier to diagnosis by inhibiting particular services required for adequate patient care. For our patient, diagnosis was delayed by several weeks due to difficulties obtaining a diagnostic skin biopsy. When faced with challenges from health care infrastructure, creativity with treatment options, such as finding an empiric treatment option (cyclosporine in this case), must be considered.

Systemic retinoids have been found to be efficacious treatment options for PRP, but when dealing with a woman of reproductive age, reproductive preferences must be discussed before identifying an appropriate treatment regimen.1,13-15 The half-life of acitretin compared to isotretinoin is 2 days vs 22 hours.6,16 With alcohol consumption, acitretin can be metabolized to etretinate, which has a half-life of 120 days.17 In our patient, isotretinoin was a more manageable option to allow for greater reproductive freedom upon treatment completion.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

- Klein A, Landthaler M, Karrer S. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2010;11:157-170.

- Shenefelt PD. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Medscape website. Updated September 11, 2020. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://reference.medscape.com/article/1107742-overview

- Griffiths WA. Pityriasis rubra pilaris. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1980;5:105-112.

- Itin PH, Lautenschlager S. Palmoplantar keratoderma and associated syndromes. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:152-161.

- Guidelines of care for psoriasis. Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:632-637.

- Larsen FG, Jakobsen P, Eriksen H, et al. The pharmacokinetics of acitretin and its 13-cis-metabolite in psoriatic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;31:477-483.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Sørensen KB, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a retrospective analysis of 43 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1999;79:405-406.

- Lucker GP, Van de Kerkhof PC, Steijlen PM. The hereditary palmoplantar keratoses: an updated review and classification. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:1-14.

- Cutaneous reactions to labetalol. Br Med J. 1978;1:987.

- Plana A, Carrascosa JM, Vilavella M. Pityriasis rubra pilaris‐like reaction induced by imatinib. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:520-522.

- Gajinov ZT, Matc´ MB, Duran VD, et al. Drug-related pityriasis rubra pilaris with acantholysis. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:871-873.

- Clayton BD, Jorizzo JL, Hitchcock MG, et al. Adult pityriasis rubra pilaris: a 10-year case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:959-964.

- Cohen PR, Prystowsky JH. Pityriasis rubra pilaris: a review of diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20:801-807.

- Dicken CH. Isotretinoin treatment of pityriasis rubra pilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(2 pt 1):297-301.

- Layton A. The use of isotretinoin in acne. Dermatoendocrinol. 2009;1:162-169.

- Grønhøj Larsen F, Steinkjer B, Jakobsen P, et al. Acitretin is converted to etretinate only during concomitant alcohol intake. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1164-1169.

Practice Points

- Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is a rare inflammatory dermatosis of unknown etiology characterized by erythematosquamous salmon-colored plaques with well-demarcated islands of unaffected skin and hyperkeratotic follicles.

- The diagnosis of PRP often can be challenging given the variety of clinical presentations.

Psoriasis Treatment in HIV-Positive Patients: A Systematic Review of Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapies

The prevalence of psoriasis among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patients in the United States is reported to be approximately 1% to 3%, which is similar to the rates reported for the general population.1 Recalcitrant cases of psoriasis in patients with no history of the condition can be the initial manifestation of HIV infection. In patients with preexisting psoriasis, a flare of their disease can be seen following infection, and progression of HIV correlates with worsening psoriasis.2 Psoriatic arthropathy also affects 23% to 50% of HIV-positive patients with psoriasis worldwide, which may be higher than the general population,1 with more severe joint disease.

The management of psoriatic disease in the HIV-positive population is challenging. The current first-line recommendations for treatment include topical therapies, phototherapy, and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), followed by oral retinoids as second-line agents.3 However, the clinical course of psoriasis in HIV-positive patients often is progressive and refractory2; therefore, these therapies often are inadequate to control both skin and joint manifestations. Most other currently available systemic therapies for psoriatic disease are immunosuppressive, which poses a distinct clinical challenge because HIV-positive patients are already immunocompromised.

There currently are many systemic immunosuppressive agents used for the treatment of psoriatic disease, including oral agents (eg, methotrexate, hydroxyurea, cyclosporine), as well as newer biologic medications, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol. Golimumab and certolizumab pegol currently are indicated for psoriatic arthritis only. Other newer biologic therapies include ustekinumab, which inhibits IL-12 and IL-23, and secukinumab, which inhibits IL-17A. The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the most current literature to explore the efficacy and safety data as they pertain to systemic immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of psoriatic disease in HIV-positive individuals.

Methods

To investigate the efficacy and safety of systemic immunosuppressive therapies for psoriatic disease in HIV-positive individuals, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE (1985-2015) was conducted using the terms psoriasis and HIV and psoriatic arthritis and HIV combined with each of the following systemic immunosuppressive agents: methotrexate, hydroxyurea, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab, and secukinumab. Pediatric cases and articles that were not available in the English language were excluded.

For each case, patient demographic information (ie, age, sex), prior failed psoriasis treatments, and history of HAART were documented. The dosing regimen of the systemic agent was noted when different from the US Food and Drug administration–approved dosage for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. The duration of immunosuppressive therapy as well as pretreatment and posttreatment CD4 and viral counts (when available) were collected. The response to treatment and adverse effects were summarized.

Results

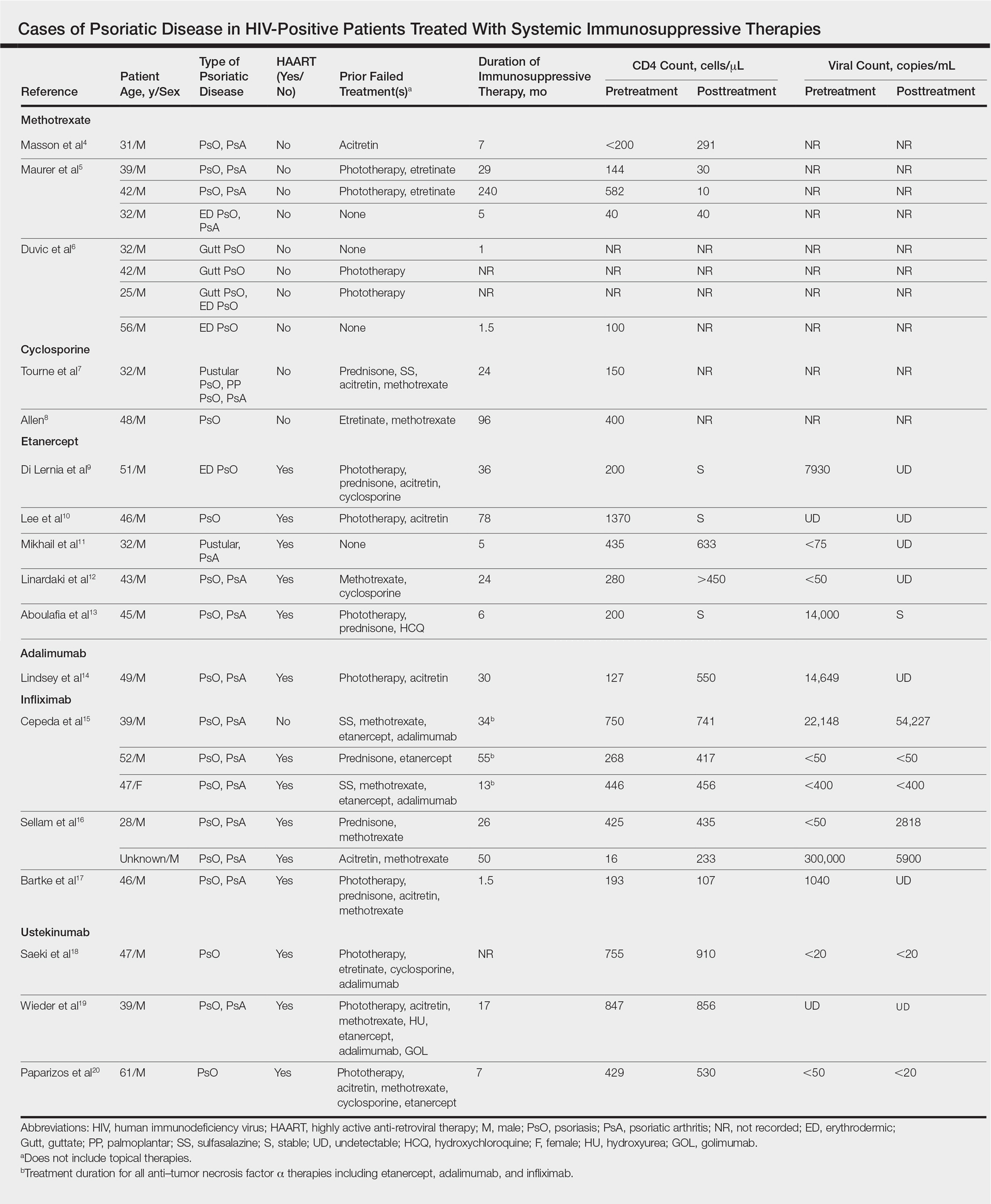

Our review of the literature yielded a total of 25 reported cases of systemic immunosuppressive therapies used to treat psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients, including methotrexate, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, in-fliximab, and ustekinumab (Table). There were no reports of the use of hydroxyurea, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, or secukinumab to treat psoriatic disease in this patient population.

Methotrexate

Eight individual cases of methotrexate used to treat psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients were reported.4-6 Duvic et al6 described 4 patients with psoriatic disease that was treated with methotrexate with varying efficacy. One patient developed toxic encephalopathy, which improved after discontinuation of methotrexate; however, he died 5 months later from pneumocystis pneumonia. In this early study, none of the 4 patients were on antiretroviral therapy for HIV.6

In the cases reported by Masson et al4 and Maurer et al,5 4 patients were treated with a single antiretroviral agent and received appropriate prophylaxis against opportunistic infections. In 1 case, methotrexate was given at a chemotherapeutic dose of 525 mg once weekly for Kaposi sarcoma.4 In 2 of 4 cases, the patients developed pneumocystis pneumonia.4,5

Cyclosporine

There were 2 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with cyclosporine in HIV-positive patients.7,8 Skin and joint manifestations improved rapidly without reports of infection for 27 and 8 years.8 Both patients were treated with one antiretroviral agent.7,8

Etanercept

There were 5 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with etanercept. In all 5 cases the patients were on HAART, and the CD4 count increased or remained stable and viral count became undetectable or remained stable following treatment.9-13 In 2 cases, the patient also had hepatitis C virus, which remained stable throughout the treatment period.9,12 The maximum duration of treatment was 6 years, with only 1 reported adverse event.13 In this case reported by Aboulafia et al,13 the patient experienced recurrent polymicrobial infections, including enterococcal cellulitis, cystitis, and bacteremia, as well as pseudomonas pneumonia and septic arthritis. Therapy was discontinued at 6 months. Four months after discontinuation of etanercept, the patient died from infectious causes.13

Adalimumab

There was 1 case of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with adalimumab in an HIV-positive patient. In this case, the patient was on HAART, and CD4 and viral counts improved substantially after 30 months of treatment.14

Infliximab

Six individual cases of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with infliximab were reported.15-17 In a report by Cepeda et al,15 HIV-positive patients with various rheumatologic diseases were chosen to receive etanercept followed by adalimumab and/or infliximab if clinical improvement was not observed on etanercept. In 3 patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, inadequate response was observed on etanercept. Two of these 3 patients received adalimumab with only partial response. All 3 were treated with infliximab in the end and showed excellent response. One of the patients experienced facial abscess responsive to antibiotics and was continued on infliximab therapy without further complications. In all 6 cases of infliximab therapy, the patients were on HAART, and CD4 and viral counts improved or remained stable.15

Ustekinumab

There were 3 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with ustekinumab in HIV-positive patients on HAART. CD4 and viral counts improved or remained stable.18-20

Comment

Currently, all of the systemic immunosuppressive therapies approved for psoriatic disease have a warning by the US Food and Drug Administration for increased risk of serious infection. Given such labels, these therapies are not routinely prescribed for HIV-positive patients who are already immunocompromised; however, many HIV-positive patients have severe psoriatic disease that cannot be adequately treated with first- and second-line therapies including topical agents, phototherapy, or oral retinoids.

Our comprehensive review yielded a total of 25 reported cases of systemic immunosuppressive therapies used to treat psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients including methotrexate, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, in-fliximab, and ustekinumab. Although data are limited to case reports and case series, some trends were observed.

Efficacy

In most of the cases reviewed, the patients had inadequate improvement of psoriatic disease with first- and second-line therapies, which included antiretrovirals alone, topical agents, phototherapy, and oral retinoids. Some cases reported poor response to methotrexate and cyclosporine.4-8 Biologic agents were effective in many such cases.

Safety

Overall, there were 11 cases in which the patient was not on adequate HAART while being treated with systemic immunosuppressive therapy for psoriatic disease.4-8,15 Of them, 3 were associated with serious infection while on methotrexate.5,6 There was only 1 report of serious infection13 of 14 cases in which the patient was on concomitant HAART. In this case, which reported polymicrobial infections and subsequent death of the patient, the infections continued after discontinuing etanercept; thus, the association is unclear. Interestingly, despite multiple infections, the CD4 and viral counts were stable throughout treatment with etanercept.13

From reviewing the 4 total cases5,6,13 of serious infection, HAART appears to be a valuable concomitant treatment during systemic immunosuppressive therapy for HIV-positive patients; however, it does not necessarily prevent serious infections from occurring, and thus the clinician’s diligence in monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection remains important.

CD4 and Viral Counts

Although reports of CD4 and viral counts were not available in earlier studies,4-8 there were 15 cases that reported consistent pretreatment and posttreatment CD4 and viral counts during treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.9-20 In all cases, the CD4 count was stable or increased. Similarly, the viral count was stable or decreased. All patients, except 1 by Cepeda et al,15 were on concomitant HAART.9-14,16-20

Although data are limited, treatment of psoriatic disease with biologic agents when used in combination with HAART may have beneficial effects on CD4 and viral counts. Tumor necrosis factor has a role in HIV expression through the action of nuclear factor κβ.21 An increase in TNF levels is shown to be associated with increased viral count, decreased CD4 count, and increased symptoms of HIV progression, such as fever, fatigue, cachexia, and dementia.22 Although more studies are necessary, TNF-α inhibitors may have a positive effect on HIV while simultaneously treating psoriatic disease. Other cytokines (eg, IL-12, IL-23, IL-17) involved in the mechanism of action of other biologic agents (ustekinumab and secukinumab) have not been shown to be directly associated with HIV activity; however, studies have shown that IL-10 has a role in inhibiting HIV-1 replication and inhibits secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and TNF-α.21 It may be speculated that the inhibition of IL-12 and TNF-α may create a positive feedback effect to increase IL-10, which in turn inhibits HIV replication.

Conclusion

Although there are limited data on the efficacy and safety of systemic immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients, a review of 25 individual cases suggest that these treatments are not only required but also are sufficient to treat some of the most resistant cases. It is possible that with adequate concomitant HAART and monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection, the likelihood of serious infection may be low. Furthermore, biologic agents may have a positive effect over other systemic immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, in improving CD4 and viral counts when used in combination with HAART. Although randomized controlled trials are necessary, current biologic therapies such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab may be safe viable options as third-line treatment of severe psoriasis in the HIV-positive population.

- Mallon

E, Bunker CB. HIV-associated psoriasis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:239-246. - Montaz

eri A, Kanitakis J, Bazex J. Psoriasis and HIV infection. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:475-479. - Menon

K, Van Vorhees AS, Bebo BF, et al; National Psoriasis Foundation. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299. - Masso

n C, Chennebault JM, Leclech C. Is HIV infection contraindication to the use of methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis? J Rheumatol. 1995;22:2191. - Maurer

TA, Zackheim HS, Tuffanelli L, et al. The use of methotrexate for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:372-375. - Duvic

M, Johnson TM, Rapini RP, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated psoriasis and Reiter’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1622-1632. - Tourne

L, Durez P, Van Vooren JP, et al. Alleviation of HIV-associated psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with cyclosporine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:501-502. - Allen

BR. Use of cyclosporine for psoriasis in HIV-positive patient. Lancet. 1992;339:686. - Di Ler

nia V, Zoboli G, Ficarelli E. Long-term management of HIV/hepatitis C virus associated psoriasis with etanercept. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:444. - Lee E

S, Heller MM, Kamangar F, et al. Long-term etanercept use for severe generalized psoriasis in an HIV-infected individual: a case study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:413-414. - Mikha

il M, Weinberg JM, Smith BL. Successful treatment with etanercept of von Zumbusch pustular psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:453-456. - Linar

daki G, Katsarou O, Ioannidou P, et al. Effective etanercept treatment for psoriatic arthritis complicating concomitant human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infection. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1353-1355. - Aboul

afia DM, Bundow D, Wilske K, et al. Etanercept for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated psoriatic arthritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1093-1098. - Linds

ey SF, Weiss J, Lee ES, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with adalimumab in an HIV-positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:869-871. - Ceped

a EJ, Williams FM, Ishimori ML, et al. The use of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in HIV-positive individuals with rheumatic disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:710-712. - Sella

m J, Bouvard B, Masson C, et al. Use of infliximab to treat psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:197-200. - Bartk

e U, Venten I, Kreuter A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:784-786. - Saeki

H, Ito T, Hayashi M, et al. Successful treatment of ustekinumab in a severe psoriasis patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1653-1655. - Wiede

r S, Routt E, Levitt J, et al. Treatment of refractory psoriasis with ustekinumab in an HIV-positive patient: a case presentation and review of the biologic literature. Psoriasis Forum. 2014;20:96-102. - Papar

izos V, Rallis E, Kirsten L, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of HIV psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:398-399. - Kedzierska K, Crowe SM, Turville S, et al. The influence of cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors on HIV-1 replication in monocytes and macrophages. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:39-56.

- Emer JJ. Is there a potential role for anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:29-35.

The prevalence of psoriasis among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patients in the United States is reported to be approximately 1% to 3%, which is similar to the rates reported for the general population.1 Recalcitrant cases of psoriasis in patients with no history of the condition can be the initial manifestation of HIV infection. In patients with preexisting psoriasis, a flare of their disease can be seen following infection, and progression of HIV correlates with worsening psoriasis.2 Psoriatic arthropathy also affects 23% to 50% of HIV-positive patients with psoriasis worldwide, which may be higher than the general population,1 with more severe joint disease.

The management of psoriatic disease in the HIV-positive population is challenging. The current first-line recommendations for treatment include topical therapies, phototherapy, and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), followed by oral retinoids as second-line agents.3 However, the clinical course of psoriasis in HIV-positive patients often is progressive and refractory2; therefore, these therapies often are inadequate to control both skin and joint manifestations. Most other currently available systemic therapies for psoriatic disease are immunosuppressive, which poses a distinct clinical challenge because HIV-positive patients are already immunocompromised.

There currently are many systemic immunosuppressive agents used for the treatment of psoriatic disease, including oral agents (eg, methotrexate, hydroxyurea, cyclosporine), as well as newer biologic medications, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol. Golimumab and certolizumab pegol currently are indicated for psoriatic arthritis only. Other newer biologic therapies include ustekinumab, which inhibits IL-12 and IL-23, and secukinumab, which inhibits IL-17A. The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the most current literature to explore the efficacy and safety data as they pertain to systemic immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of psoriatic disease in HIV-positive individuals.

Methods

To investigate the efficacy and safety of systemic immunosuppressive therapies for psoriatic disease in HIV-positive individuals, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE (1985-2015) was conducted using the terms psoriasis and HIV and psoriatic arthritis and HIV combined with each of the following systemic immunosuppressive agents: methotrexate, hydroxyurea, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab, and secukinumab. Pediatric cases and articles that were not available in the English language were excluded.

For each case, patient demographic information (ie, age, sex), prior failed psoriasis treatments, and history of HAART were documented. The dosing regimen of the systemic agent was noted when different from the US Food and Drug administration–approved dosage for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. The duration of immunosuppressive therapy as well as pretreatment and posttreatment CD4 and viral counts (when available) were collected. The response to treatment and adverse effects were summarized.

Results

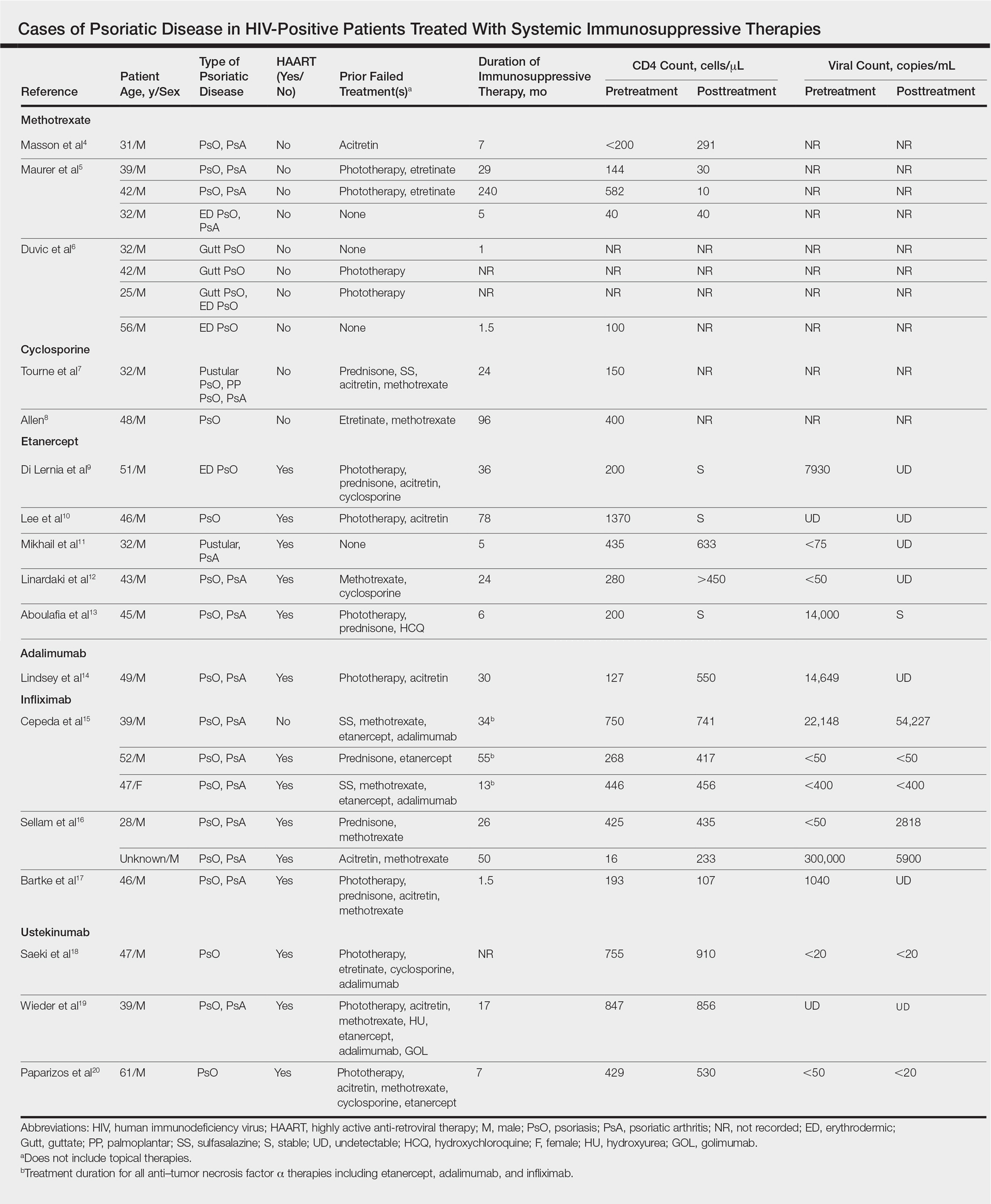

Our review of the literature yielded a total of 25 reported cases of systemic immunosuppressive therapies used to treat psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients, including methotrexate, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, in-fliximab, and ustekinumab (Table). There were no reports of the use of hydroxyurea, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, or secukinumab to treat psoriatic disease in this patient population.

Methotrexate

Eight individual cases of methotrexate used to treat psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients were reported.4-6 Duvic et al6 described 4 patients with psoriatic disease that was treated with methotrexate with varying efficacy. One patient developed toxic encephalopathy, which improved after discontinuation of methotrexate; however, he died 5 months later from pneumocystis pneumonia. In this early study, none of the 4 patients were on antiretroviral therapy for HIV.6

In the cases reported by Masson et al4 and Maurer et al,5 4 patients were treated with a single antiretroviral agent and received appropriate prophylaxis against opportunistic infections. In 1 case, methotrexate was given at a chemotherapeutic dose of 525 mg once weekly for Kaposi sarcoma.4 In 2 of 4 cases, the patients developed pneumocystis pneumonia.4,5

Cyclosporine

There were 2 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with cyclosporine in HIV-positive patients.7,8 Skin and joint manifestations improved rapidly without reports of infection for 27 and 8 years.8 Both patients were treated with one antiretroviral agent.7,8

Etanercept

There were 5 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with etanercept. In all 5 cases the patients were on HAART, and the CD4 count increased or remained stable and viral count became undetectable or remained stable following treatment.9-13 In 2 cases, the patient also had hepatitis C virus, which remained stable throughout the treatment period.9,12 The maximum duration of treatment was 6 years, with only 1 reported adverse event.13 In this case reported by Aboulafia et al,13 the patient experienced recurrent polymicrobial infections, including enterococcal cellulitis, cystitis, and bacteremia, as well as pseudomonas pneumonia and septic arthritis. Therapy was discontinued at 6 months. Four months after discontinuation of etanercept, the patient died from infectious causes.13

Adalimumab

There was 1 case of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with adalimumab in an HIV-positive patient. In this case, the patient was on HAART, and CD4 and viral counts improved substantially after 30 months of treatment.14

Infliximab

Six individual cases of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with infliximab were reported.15-17 In a report by Cepeda et al,15 HIV-positive patients with various rheumatologic diseases were chosen to receive etanercept followed by adalimumab and/or infliximab if clinical improvement was not observed on etanercept. In 3 patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, inadequate response was observed on etanercept. Two of these 3 patients received adalimumab with only partial response. All 3 were treated with infliximab in the end and showed excellent response. One of the patients experienced facial abscess responsive to antibiotics and was continued on infliximab therapy without further complications. In all 6 cases of infliximab therapy, the patients were on HAART, and CD4 and viral counts improved or remained stable.15

Ustekinumab

There were 3 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with ustekinumab in HIV-positive patients on HAART. CD4 and viral counts improved or remained stable.18-20

Comment

Currently, all of the systemic immunosuppressive therapies approved for psoriatic disease have a warning by the US Food and Drug Administration for increased risk of serious infection. Given such labels, these therapies are not routinely prescribed for HIV-positive patients who are already immunocompromised; however, many HIV-positive patients have severe psoriatic disease that cannot be adequately treated with first- and second-line therapies including topical agents, phototherapy, or oral retinoids.

Our comprehensive review yielded a total of 25 reported cases of systemic immunosuppressive therapies used to treat psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients including methotrexate, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, in-fliximab, and ustekinumab. Although data are limited to case reports and case series, some trends were observed.

Efficacy

In most of the cases reviewed, the patients had inadequate improvement of psoriatic disease with first- and second-line therapies, which included antiretrovirals alone, topical agents, phototherapy, and oral retinoids. Some cases reported poor response to methotrexate and cyclosporine.4-8 Biologic agents were effective in many such cases.

Safety

Overall, there were 11 cases in which the patient was not on adequate HAART while being treated with systemic immunosuppressive therapy for psoriatic disease.4-8,15 Of them, 3 were associated with serious infection while on methotrexate.5,6 There was only 1 report of serious infection13 of 14 cases in which the patient was on concomitant HAART. In this case, which reported polymicrobial infections and subsequent death of the patient, the infections continued after discontinuing etanercept; thus, the association is unclear. Interestingly, despite multiple infections, the CD4 and viral counts were stable throughout treatment with etanercept.13

From reviewing the 4 total cases5,6,13 of serious infection, HAART appears to be a valuable concomitant treatment during systemic immunosuppressive therapy for HIV-positive patients; however, it does not necessarily prevent serious infections from occurring, and thus the clinician’s diligence in monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection remains important.

CD4 and Viral Counts

Although reports of CD4 and viral counts were not available in earlier studies,4-8 there were 15 cases that reported consistent pretreatment and posttreatment CD4 and viral counts during treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.9-20 In all cases, the CD4 count was stable or increased. Similarly, the viral count was stable or decreased. All patients, except 1 by Cepeda et al,15 were on concomitant HAART.9-14,16-20

Although data are limited, treatment of psoriatic disease with biologic agents when used in combination with HAART may have beneficial effects on CD4 and viral counts. Tumor necrosis factor has a role in HIV expression through the action of nuclear factor κβ.21 An increase in TNF levels is shown to be associated with increased viral count, decreased CD4 count, and increased symptoms of HIV progression, such as fever, fatigue, cachexia, and dementia.22 Although more studies are necessary, TNF-α inhibitors may have a positive effect on HIV while simultaneously treating psoriatic disease. Other cytokines (eg, IL-12, IL-23, IL-17) involved in the mechanism of action of other biologic agents (ustekinumab and secukinumab) have not been shown to be directly associated with HIV activity; however, studies have shown that IL-10 has a role in inhibiting HIV-1 replication and inhibits secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and TNF-α.21 It may be speculated that the inhibition of IL-12 and TNF-α may create a positive feedback effect to increase IL-10, which in turn inhibits HIV replication.

Conclusion

Although there are limited data on the efficacy and safety of systemic immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients, a review of 25 individual cases suggest that these treatments are not only required but also are sufficient to treat some of the most resistant cases. It is possible that with adequate concomitant HAART and monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection, the likelihood of serious infection may be low. Furthermore, biologic agents may have a positive effect over other systemic immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, in improving CD4 and viral counts when used in combination with HAART. Although randomized controlled trials are necessary, current biologic therapies such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab may be safe viable options as third-line treatment of severe psoriasis in the HIV-positive population.

The prevalence of psoriasis among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive patients in the United States is reported to be approximately 1% to 3%, which is similar to the rates reported for the general population.1 Recalcitrant cases of psoriasis in patients with no history of the condition can be the initial manifestation of HIV infection. In patients with preexisting psoriasis, a flare of their disease can be seen following infection, and progression of HIV correlates with worsening psoriasis.2 Psoriatic arthropathy also affects 23% to 50% of HIV-positive patients with psoriasis worldwide, which may be higher than the general population,1 with more severe joint disease.

The management of psoriatic disease in the HIV-positive population is challenging. The current first-line recommendations for treatment include topical therapies, phototherapy, and highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), followed by oral retinoids as second-line agents.3 However, the clinical course of psoriasis in HIV-positive patients often is progressive and refractory2; therefore, these therapies often are inadequate to control both skin and joint manifestations. Most other currently available systemic therapies for psoriatic disease are immunosuppressive, which poses a distinct clinical challenge because HIV-positive patients are already immunocompromised.

There currently are many systemic immunosuppressive agents used for the treatment of psoriatic disease, including oral agents (eg, methotrexate, hydroxyurea, cyclosporine), as well as newer biologic medications, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol. Golimumab and certolizumab pegol currently are indicated for psoriatic arthritis only. Other newer biologic therapies include ustekinumab, which inhibits IL-12 and IL-23, and secukinumab, which inhibits IL-17A. The purpose of this systematic review is to evaluate the most current literature to explore the efficacy and safety data as they pertain to systemic immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of psoriatic disease in HIV-positive individuals.

Methods

To investigate the efficacy and safety of systemic immunosuppressive therapies for psoriatic disease in HIV-positive individuals, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE (1985-2015) was conducted using the terms psoriasis and HIV and psoriatic arthritis and HIV combined with each of the following systemic immunosuppressive agents: methotrexate, hydroxyurea, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, ustekinumab, and secukinumab. Pediatric cases and articles that were not available in the English language were excluded.

For each case, patient demographic information (ie, age, sex), prior failed psoriasis treatments, and history of HAART were documented. The dosing regimen of the systemic agent was noted when different from the US Food and Drug administration–approved dosage for psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. The duration of immunosuppressive therapy as well as pretreatment and posttreatment CD4 and viral counts (when available) were collected. The response to treatment and adverse effects were summarized.

Results

Our review of the literature yielded a total of 25 reported cases of systemic immunosuppressive therapies used to treat psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients, including methotrexate, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, in-fliximab, and ustekinumab (Table). There were no reports of the use of hydroxyurea, golimumab, certolizumab pegol, or secukinumab to treat psoriatic disease in this patient population.

Methotrexate

Eight individual cases of methotrexate used to treat psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients were reported.4-6 Duvic et al6 described 4 patients with psoriatic disease that was treated with methotrexate with varying efficacy. One patient developed toxic encephalopathy, which improved after discontinuation of methotrexate; however, he died 5 months later from pneumocystis pneumonia. In this early study, none of the 4 patients were on antiretroviral therapy for HIV.6

In the cases reported by Masson et al4 and Maurer et al,5 4 patients were treated with a single antiretroviral agent and received appropriate prophylaxis against opportunistic infections. In 1 case, methotrexate was given at a chemotherapeutic dose of 525 mg once weekly for Kaposi sarcoma.4 In 2 of 4 cases, the patients developed pneumocystis pneumonia.4,5

Cyclosporine

There were 2 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with cyclosporine in HIV-positive patients.7,8 Skin and joint manifestations improved rapidly without reports of infection for 27 and 8 years.8 Both patients were treated with one antiretroviral agent.7,8

Etanercept

There were 5 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with etanercept. In all 5 cases the patients were on HAART, and the CD4 count increased or remained stable and viral count became undetectable or remained stable following treatment.9-13 In 2 cases, the patient also had hepatitis C virus, which remained stable throughout the treatment period.9,12 The maximum duration of treatment was 6 years, with only 1 reported adverse event.13 In this case reported by Aboulafia et al,13 the patient experienced recurrent polymicrobial infections, including enterococcal cellulitis, cystitis, and bacteremia, as well as pseudomonas pneumonia and septic arthritis. Therapy was discontinued at 6 months. Four months after discontinuation of etanercept, the patient died from infectious causes.13

Adalimumab

There was 1 case of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with adalimumab in an HIV-positive patient. In this case, the patient was on HAART, and CD4 and viral counts improved substantially after 30 months of treatment.14

Infliximab

Six individual cases of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with infliximab were reported.15-17 In a report by Cepeda et al,15 HIV-positive patients with various rheumatologic diseases were chosen to receive etanercept followed by adalimumab and/or infliximab if clinical improvement was not observed on etanercept. In 3 patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, inadequate response was observed on etanercept. Two of these 3 patients received adalimumab with only partial response. All 3 were treated with infliximab in the end and showed excellent response. One of the patients experienced facial abscess responsive to antibiotics and was continued on infliximab therapy without further complications. In all 6 cases of infliximab therapy, the patients were on HAART, and CD4 and viral counts improved or remained stable.15

Ustekinumab

There were 3 case reports of successful treatment of psoriatic disease with ustekinumab in HIV-positive patients on HAART. CD4 and viral counts improved or remained stable.18-20

Comment

Currently, all of the systemic immunosuppressive therapies approved for psoriatic disease have a warning by the US Food and Drug Administration for increased risk of serious infection. Given such labels, these therapies are not routinely prescribed for HIV-positive patients who are already immunocompromised; however, many HIV-positive patients have severe psoriatic disease that cannot be adequately treated with first- and second-line therapies including topical agents, phototherapy, or oral retinoids.

Our comprehensive review yielded a total of 25 reported cases of systemic immunosuppressive therapies used to treat psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients including methotrexate, cyclosporine, etanercept, adalimumab, in-fliximab, and ustekinumab. Although data are limited to case reports and case series, some trends were observed.

Efficacy

In most of the cases reviewed, the patients had inadequate improvement of psoriatic disease with first- and second-line therapies, which included antiretrovirals alone, topical agents, phototherapy, and oral retinoids. Some cases reported poor response to methotrexate and cyclosporine.4-8 Biologic agents were effective in many such cases.

Safety

Overall, there were 11 cases in which the patient was not on adequate HAART while being treated with systemic immunosuppressive therapy for psoriatic disease.4-8,15 Of them, 3 were associated with serious infection while on methotrexate.5,6 There was only 1 report of serious infection13 of 14 cases in which the patient was on concomitant HAART. In this case, which reported polymicrobial infections and subsequent death of the patient, the infections continued after discontinuing etanercept; thus, the association is unclear. Interestingly, despite multiple infections, the CD4 and viral counts were stable throughout treatment with etanercept.13

From reviewing the 4 total cases5,6,13 of serious infection, HAART appears to be a valuable concomitant treatment during systemic immunosuppressive therapy for HIV-positive patients; however, it does not necessarily prevent serious infections from occurring, and thus the clinician’s diligence in monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection remains important.

CD4 and Viral Counts

Although reports of CD4 and viral counts were not available in earlier studies,4-8 there were 15 cases that reported consistent pretreatment and posttreatment CD4 and viral counts during treatment with etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab.9-20 In all cases, the CD4 count was stable or increased. Similarly, the viral count was stable or decreased. All patients, except 1 by Cepeda et al,15 were on concomitant HAART.9-14,16-20

Although data are limited, treatment of psoriatic disease with biologic agents when used in combination with HAART may have beneficial effects on CD4 and viral counts. Tumor necrosis factor has a role in HIV expression through the action of nuclear factor κβ.21 An increase in TNF levels is shown to be associated with increased viral count, decreased CD4 count, and increased symptoms of HIV progression, such as fever, fatigue, cachexia, and dementia.22 Although more studies are necessary, TNF-α inhibitors may have a positive effect on HIV while simultaneously treating psoriatic disease. Other cytokines (eg, IL-12, IL-23, IL-17) involved in the mechanism of action of other biologic agents (ustekinumab and secukinumab) have not been shown to be directly associated with HIV activity; however, studies have shown that IL-10 has a role in inhibiting HIV-1 replication and inhibits secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-12 and TNF-α.21 It may be speculated that the inhibition of IL-12 and TNF-α may create a positive feedback effect to increase IL-10, which in turn inhibits HIV replication.

Conclusion

Although there are limited data on the efficacy and safety of systemic immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of psoriatic disease in HIV-positive patients, a review of 25 individual cases suggest that these treatments are not only required but also are sufficient to treat some of the most resistant cases. It is possible that with adequate concomitant HAART and monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection, the likelihood of serious infection may be low. Furthermore, biologic agents may have a positive effect over other systemic immunosuppressive agents, such as methotrexate and cyclosporine, in improving CD4 and viral counts when used in combination with HAART. Although randomized controlled trials are necessary, current biologic therapies such as etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, and ustekinumab may be safe viable options as third-line treatment of severe psoriasis in the HIV-positive population.

- Mallon

E, Bunker CB. HIV-associated psoriasis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:239-246. - Montaz

eri A, Kanitakis J, Bazex J. Psoriasis and HIV infection. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:475-479. - Menon

K, Van Vorhees AS, Bebo BF, et al; National Psoriasis Foundation. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299. - Masso

n C, Chennebault JM, Leclech C. Is HIV infection contraindication to the use of methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis? J Rheumatol. 1995;22:2191. - Maurer

TA, Zackheim HS, Tuffanelli L, et al. The use of methotrexate for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:372-375. - Duvic

M, Johnson TM, Rapini RP, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated psoriasis and Reiter’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1622-1632. - Tourne

L, Durez P, Van Vooren JP, et al. Alleviation of HIV-associated psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with cyclosporine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:501-502. - Allen

BR. Use of cyclosporine for psoriasis in HIV-positive patient. Lancet. 1992;339:686. - Di Ler

nia V, Zoboli G, Ficarelli E. Long-term management of HIV/hepatitis C virus associated psoriasis with etanercept. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:444. - Lee E

S, Heller MM, Kamangar F, et al. Long-term etanercept use for severe generalized psoriasis in an HIV-infected individual: a case study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:413-414. - Mikha

il M, Weinberg JM, Smith BL. Successful treatment with etanercept of von Zumbusch pustular psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:453-456. - Linar

daki G, Katsarou O, Ioannidou P, et al. Effective etanercept treatment for psoriatic arthritis complicating concomitant human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infection. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1353-1355. - Aboul

afia DM, Bundow D, Wilske K, et al. Etanercept for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated psoriatic arthritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1093-1098. - Linds

ey SF, Weiss J, Lee ES, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with adalimumab in an HIV-positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:869-871. - Ceped

a EJ, Williams FM, Ishimori ML, et al. The use of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in HIV-positive individuals with rheumatic disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:710-712. - Sella

m J, Bouvard B, Masson C, et al. Use of infliximab to treat psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:197-200. - Bartk

e U, Venten I, Kreuter A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:784-786. - Saeki

H, Ito T, Hayashi M, et al. Successful treatment of ustekinumab in a severe psoriasis patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1653-1655. - Wiede

r S, Routt E, Levitt J, et al. Treatment of refractory psoriasis with ustekinumab in an HIV-positive patient: a case presentation and review of the biologic literature. Psoriasis Forum. 2014;20:96-102. - Papar

izos V, Rallis E, Kirsten L, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of HIV psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:398-399. - Kedzierska K, Crowe SM, Turville S, et al. The influence of cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors on HIV-1 replication in monocytes and macrophages. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:39-56.

- Emer JJ. Is there a potential role for anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:29-35.

- Mallon

E, Bunker CB. HIV-associated psoriasis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14:239-246. - Montaz

eri A, Kanitakis J, Bazex J. Psoriasis and HIV infection. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:475-479. - Menon

K, Van Vorhees AS, Bebo BF, et al; National Psoriasis Foundation. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the medical board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291-299. - Masso

n C, Chennebault JM, Leclech C. Is HIV infection contraindication to the use of methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis? J Rheumatol. 1995;22:2191. - Maurer

TA, Zackheim HS, Tuffanelli L, et al. The use of methotrexate for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:372-375. - Duvic

M, Johnson TM, Rapini RP, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated psoriasis and Reiter’s syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1622-1632. - Tourne

L, Durez P, Van Vooren JP, et al. Alleviation of HIV-associated psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with cyclosporine. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:501-502. - Allen

BR. Use of cyclosporine for psoriasis in HIV-positive patient. Lancet. 1992;339:686. - Di Ler

nia V, Zoboli G, Ficarelli E. Long-term management of HIV/hepatitis C virus associated psoriasis with etanercept. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:444. - Lee E

S, Heller MM, Kamangar F, et al. Long-term etanercept use for severe generalized psoriasis in an HIV-infected individual: a case study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:413-414. - Mikha

il M, Weinberg JM, Smith BL. Successful treatment with etanercept of von Zumbusch pustular psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:453-456. - Linar

daki G, Katsarou O, Ioannidou P, et al. Effective etanercept treatment for psoriatic arthritis complicating concomitant human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infection. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1353-1355. - Aboul

afia DM, Bundow D, Wilske K, et al. Etanercept for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-associated psoriatic arthritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75:1093-1098. - Linds

ey SF, Weiss J, Lee ES, et al. Treatment of severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with adalimumab in an HIV-positive patient. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:869-871. - Ceped

a EJ, Williams FM, Ishimori ML, et al. The use of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in HIV-positive individuals with rheumatic disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:710-712. - Sella

m J, Bouvard B, Masson C, et al. Use of infliximab to treat psoriatic arthritis in HIV-positive patients. Joint Bone Spine. 2007;74:197-200. - Bartk

e U, Venten I, Kreuter A, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with infliximab. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:784-786. - Saeki

H, Ito T, Hayashi M, et al. Successful treatment of ustekinumab in a severe psoriasis patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1653-1655. - Wiede

r S, Routt E, Levitt J, et al. Treatment of refractory psoriasis with ustekinumab in an HIV-positive patient: a case presentation and review of the biologic literature. Psoriasis Forum. 2014;20:96-102. - Papar

izos V, Rallis E, Kirsten L, et al. Ustekinumab for the treatment of HIV psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:398-399. - Kedzierska K, Crowe SM, Turville S, et al. The influence of cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors on HIV-1 replication in monocytes and macrophages. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:39-56.

- Emer JJ. Is there a potential role for anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:29-35.

Practice Points

- There are limited data on the use of systemic immunosuppressive therapies for the treatment of psoriatic disease in human immunodeficiency virus–positive patients.

- The limited data suggest that biologic therapies may be effective for cases of psoriasis recalcitrant to other systemic agents and may have a positive effect on CD4 and viral counts when used in combination with highly active antiretroviral therapy.

- Further research is needed.